Abstract

The JNK pathway modulates AP-1 activity. While in some cells it may have proliferative and protective roles, in neuronal cells it is involved in apoptosis in response to stress or withdrawal of survival signals. To understand how JNK activation leads to apoptosis, we used PC12 cells and primary neuronal cultures. In PC12 cells, deliberate JNK activation is followed by induction of Fas ligand (FasL) expression and apoptosis. JNK activation detected by c-Jun phosphorylation and FasL induction are also observed after removal of either nerve growth factor from differentiated PC12 cells or KCl from primary cerebellar granule neurons (CGCs). Sequestation of FasL by incubation with a Fas-Fc decoy inhibits apoptosis in all three cases. CGCs derived from gld mice (defective in FasL) are less sensitive to apoptosis caused by KCl removal than wild-type neurons. In PC12 cells, protection is also conferred by a c-Jun mutant lacking JNK phosphoacceptor sites and a small molecule inhibitor of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase and JNK, which inhibits FasL induction. Hence, the JNK-to-c-Jun-to-FasL pathway is an important mediator of stress-induced neuronal apoptosis.

Mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) play an instrumental role in transmission of signals from cell surface receptors and environmental cues to the transcriptional machinery (13, 36, 41, 52). While in eukaryotes that are amenable to genetic analysis, such as yeast (34), nematodes (43), and fruit flies (88), the biological functions of MAPK cascades are becoming clear, their role in mammals are more nebulous. In addition to the difficulty of proper genetic analysis, much of the ambiguity regarding the role of MAPK cascades in mammals is due to cell-type-dependent variations in their function. For example, the ERK MAPK cascade was initially characterized by its involvement in oncogenic transformation and mitogenic signaling (13, 52). However, in the rat pheochromocytoma PC12 cell line, ERK activation is linked to induction of neuronal differentiation which converts these cells to postmitotic cells similar to sympathetic neurons (14, 81). This function is akin to the role of the ERK pathway in formation of the vulva in Caenorhabditis elegans (43) or the retina in Drosophila melanogaster (88).

Recently, two additional MAPK cascades leading to activation of JNK (17, 35, 45) and p38 (32, 47, 70) were identified in mammalian cells. Both pathways are evolutionarily conserved, and several of their elements were identified in yeasts (16, 51) and Drosophila (28, 67, 74). Unlike the ERKs, which are most potently activated in response to signals originating from receptor and cytoplasmic protein tyrosine kinases (28, 67, 74), JNK and p38 are most potently activated by environmental stresses such as UV radiation and osmotic shock, as well as by proinflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and interleukin-1 (IL-1) (15, 40). Therefore, JNK and p38 are collectively known as stress-activated protein kinases.

The JNKs were identified through their ability to phosphorylate the N-terminal stimulatory sites of c-Jun (35). As this phosphorylation is essential for cooperation between c-Jun and activated Ras in transformation of rat embryo fibroblasts (4, 75) and since the JNKs are the only kinases that phosphorylate these sites (40), it follows that JNK activation contributes to Ras-mediated transformation. In addition c-jun-null immortalized mouse embryo fibroblasts are refractory to transformation by Ha-Ras (39, 63, 73). c-Jun is also essential for proliferation of mouse embryo fibroblasts; in its absence, the cells undergo very rapid senescence (39, 72). JNK activation is also necessary for transformation of fibroblasts by the met and bcr-abl oncogenes (65, 68).

Recently, however, JNK and p38 were implicated in induction of apoptosis. It was shown that deliberate activation of JNK and p38 in PC12 cells via transient expression of MEKK1, a MAPK kinase kinase (MAPKKK) involved in their activation (57), or by nerve growth factor (NGF) withdrawal from postmitotic PC12 cells results in apoptosis (93). That study also suggested that ERK activation may protect PC12 cells against apoptosis. Activation of JNK was also suggested to be involved in apoptosis in response to cell detachment (anoikis) (7, 26). Moreover, JNK activation was suggested to play a critical role in apoptosis of epithelial and lymphoid cells in response to radiation, TNF, or Fas ligand (FasL) (9, 85). The inducible cytokines TNF and FasL bind to related cell surface receptors, TNF-R1 and Fas, respectively, whose occupancy activates the apoptotic protease (caspase) cascade (12, 24, 58). In contrast to results obtained by expression of catalytically inactive JNK kinase 1 (JNKK1 or SEK1), which was reported to protect cells against TNF-induced apoptosis (85), dissection of the signaling pathways activated by TNF-R1 indicated that JNK activation is not linked to TNF-mediated apoptosis (49, 60). In addition, JNK activation by Fas in some cell types was shown to be a delayed response dependent on caspase activation (48). In other cell types, however, Fas activation may result in more direct JNK activation through recruitment of the signaling protein DAXX (95). In that case, JNK activation may potentiate Fas-mediated apoptosis. However, lymphocytes deficient in JNKK1/SEK1 are more sensitive rather than resistant to Fas-mediated apoptosis (62). In addition, lymphocytes from traf2−/− mice, which are defective in JNK activation, are highly sensitive to TNF-induced apoptosis (96).

While some of these results question the involvement of JNK (or p38) in apoptosis in fibroblasts and lymphocytes, the participation of JNK and c-Jun in death signaling is more firmly established in neuronal cells. NGF withdrawal from sympathetic neurons results in c-jun induction (20, 31, 56). NGF withdrawal from differentiated PC12 cells results in JNK activation (93), a signal that leads to c-jun induction and potentiation of c-Jun transcriptional activity (40). In both sympathetic neurons and PC12 cells, expression of dominant negative c-Jun mutants or microinjection of neutralizing c-Jun antibodies inhibits apoptosis (20, 31, 93). Most conclusive are the results obtained with jnk3−/− mice (94). Massive stimulation of glutamate receptors which results in excitotoxicity followed by apoptosis of hippocampal neurons in normal mice does not cause neuronal cell death in mice that are deficient in the neuron-specific JNK3 isozyme (94). None of these studies, however, provided a mechanism by which JNK activation and/or c-Jun phosphorylation can trigger apoptosis. The lack of mechanistic insight is of concern because the assumption that JNK-mediated c-Jun phosphorylation plays a causative role in apoptosis rests on the use of dominant-negative c-Jun mutants. While these mutants act in the nucleus (2), the caspase cascade is activated in the cytoplasm and does not require new gene expression or protein phosphorylation (58, 61). Thus, it is of great importance to define the steps in pathways that lead to apoptosis at which JNK and c-Jun act. Better understanding of such pathways will facilitate the development of strategies for preventing or decreasing neuronal cell death caused by stress or trauma, as suggested by the phenotype of the jnk3−/− mice (94).

To explore these pathways, we initially used the PC12 cell system to investigate how activation of JNK (and p38) leads to apoptosis. In stably transfected PC12 cell clones in which expression of MEKK1 can be induced by dexamethasone (Dex), JNK and p38 activation are followed by extensive apoptosis in which JNK and c-Jun appear to play a critical role because expression of a dominant-negative c-Jun that lacks the JNK phosphorylation sites, c-Jun(A63/73), but not wild-type (wt) c-Jun, blocks cell death. In this system, apoptosis seems to require new gene expression and JNK (and p38) activation are linked to induction of FasL. Incubation of PC12 cells, in which JNK and p38 were activated, with a chimeric Fas-Fc decoy protein (6, 77, 80) attenuates the apoptotic response. We also find that NGF withdrawal from postmitotic PC12 cells results in increased JNK and p38 activities and induction of FasL along with apoptosis, which can be inhibited by Fas-Fc. In both cases, FasL induction and apoptosis are attenuated by a small molecule inhibitor of p38 and JNK. To more critically evaluate the role of FasL induction in neuronal apoptosis, we established a physiological system based on primary cultures of cerebellar granule neurons (CGCs) in which elevated K+ serves as a survival factor (15). Such cultures were established by using CGCs isolated from either wt or gld C3H/HeJ mice, whose FasL gene codes for a nonfunctional protein (80). While KCl withdrawal results in similar degrees of JNK activation and c-Jun N-terminal phosphorylation in wt and gld CGCs, the latter are considerably less sensitive to apoptosis caused by KCl removal. Incubation of wt CGCs with Fas-Fc attenuates the apoptotic response to KCl removal. These results strongly suggest that a JNK-to-c-Jun-to-FasL signaling pathway plays an important role in induction of neuronal cell death in response to various stresses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids.

MEKK1Δ is a truncated form of MEKK1 (46) consisting of its C-terminal catalytic domain. A cDNA fragment encoding the C-terminal portion (1.7 kb) of mouse MEKK1 was subcloned into the glucocorticoid-inducible pJ5Ω vector in which expression is controlled by the murine mammary tumor virus (MMTV) long terminal repeat (57). Hemagglutinin epitope (HA)-tagged wt c-Jun and c-Jun(A63/73) (75) contain the influenza virus HA fused to the NH2 terminus of c-Jun.

Cell culture and transfection.

PC12 cells (passages 6 to 20; originally obtained from L. Greene) were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated horse serum, 5% fetal bovine serum, 1 mM glutamine, and 1% penicillin-streptomycin in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37°C. PC12 cells were cultured on poly-l-lysine (Sigma)- or poly-l-lysine/laminin (Becton Dickinson)-coated plates. Stable MEKK1Δ PC12 cell lines were generated by transfection of pJ5Ω-MEKK1Δ, using Lipofectamine (GIBCO-BRL) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Stable transfectants were selected in medium containing 250 μg of G418 (Geneticin; GIBCO) per ml. After 2 to 3 weeks, single clones were isolated and induced with 10−8 M Dex for 24 h, and MEKK1Δ-expressing clones were identified by immunoblotting with anti-MEKK1 (C-22; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). CGCs were isolated from 7-day-old wt or gld C3H/HeJ mice (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, Maine) and housed under virus-free conditions as described elsewhere (5). CGCs were seeded onto poly-d-lysine (30 μg/ml)-coated dishes at a density of 0.25 × 106 cells/cm2 and cultured in Eagle’s basal medium supplemented with 10% heat inactivated fetal bovine serum, 25 mM KCl, and 0.5% (vol/vol) penicillin-streptomycin. To prevent growth of glial cells, cytosine arabinoside (5 μM) was added to the cultures 24 h after seeding. CGCs were shifted to 5 mM KCl medium after 7 days, when they were fully differentiated (22) and the neuronal cell type represented more than 95% of the total cell population (83). Fas-Fc (40 μM) treatment was done 12 h prior to and during MEKK1Δ induction or KCl and NGF withdrawal.

Immunoblot analysis.

Cell lysates (40 to 100 μg of protein) were resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) on 8 to 12% polyacrylamide gels and electroblotted onto Immobilon P membranes (Millipore). After blocking with 5% milk in PBS-T (phosphate-buffered saline [PBS] with 0.05% Tween) for 1 h, the membranes were probed with anti-MEKK1 (C-22; Santa Cruz), anti-ERK2 (C-14; Santa Cruz), anti-c-Jun (Santa Cruz), anti-phospho-c-Jun S*63 (KM-1; Santa Cruz), anti-JNK1 (333.8; PharMingen), anti-phospho-JNK T*183/Y*185 (New England Biolabs), anti-phospho-ERK T*202/Y*204 (New England Biolabs), and anti-phospho-p38 T*182 (New England Biolabs) (asterisks mark sites of phosphorylation). The antibody-antigen complexes were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham International).

Kinase assays.

Endogenous JNK1 and ERK2 were immunoprecipitated from cell lysates (57) with an anti-JNK1 monoclonal antibody (333.8; PharMingen) or with anti-ERK2 (C-14; Santa Cruz), and their activities were measured by using 2 μg of glutathione S-transferase (GST)–c-Jun(1-79) or 4 μg of myelin basic protein (MBP; Sigma) respectively, as the substrate (17, 57). Data for all experiments were quantitated with a phosphorimager, and results were normalized to JNK or ERK levels determined by immunoblotting.

Immunofluorescence staining and in situ hybridization.

PC12 cells were cultured on poly-l-lysine-coated Permanox chamber slides (Labtek II; Nunc) and treated as indicated below. The slides were washed once with PBS, fixed for 40 min with 4% paraformaldehyde, washed three times, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 10 min, and washed four times with 0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA)–PBS. Slides were blocked in 1% BSA or 0.5% goat serum for 1 h at room temperature and then incubated for 1 h with 0.1% BSA–PBS containing anti-HA (12CA5; Boehringer Mannheim) monoclonal antibody. Following four washes, fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated goat anti-mouse (1:200 dilution; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories Inc.) in 0.1% BSA–PBS was added; incubation for 1 h at room temperature was followed by three subsequent washes. Hoechst dye H33258 (Sigma), 2.5 μg/ml in PBS, was added along with the secondary antibody. Cells were examined and photographed with a Zeiss Axioskop microscope equipped for epifluorescence with the appropriate filters.

For in situ hybridization, FasL (5′-GAGGATCTGGTGCTAATGGA-3′) and c-Jun (5′-CGCGGATCCCTATGACTGCAAAGATG-3′) oligonucleotide probes were labeled with biotin-16-dUTP by random priming (Biotin-high Prime; GIBCO-BRL). CGCs cultured on poly-d-lysine-coated Labtek II chamber slides were fixed in 100% methanol for 15 min and washed in PBS. The slides were incubated with prehybridization solution (50% deionized formamide, 10% dextran sulfate, 2× SSC [1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate], 0.12 mM EDTA, 0.33 mg of sheared salmon sperm DNA per ml) for 4 h at 42°C. After decanting of the prehybridization solution, the hybridization solution (prehybridization solution with 1 ng of biotin-labeled probe per ml) prewarmed to 42°C was added, and the slides were left in a humid chamber overnight at 42°C. Slides were washed twice in 2× SSC for 10 min and twice in 0.1× SSC for 10 min at 42°C. Biotin-labeled cells were detected with a Dako kit (Dako Inc.), using alkaline phosphatase as a secondary detection system, and visualized with a Nikon light microscope with a blue filter. As a control for specificity, cells were hybridized to the probes in the presence of 10-fold-excess unlabeled competitor (91).

RT-PCR and DNA analysis.

Total RNA was isolated from CGCs or PC12 cells by using TRIazol reagent (GIBCO-BRL). First-strand cDNA was prepared by reverse transcription (RT) of 1 μg of RNA in a 20-μl reaction volume containing 10× PCR buffer, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 200 μM deoxynucleoside triphosphates, and 5 μM random primers (Superscript reverse transcriptase; Life Technologies). PCR amplifications were performed in a 50-μl reaction volume containing 1 μg of cDNA, with a master mix composed of 10× PCR buffer, 1 mM MgCl, 200 μM deoxynucleoside triphosphates, Taq polymerase, and 20 nM each primer. Primers used were as follows: mouse FasL sense (5′-CAGCAGTGCCACTTCATCTTGG-3′) and antisense (5′-TTCACTCCAGAGATCAGAGCGG-3′); β-actin sense (5′-TGGATTCCTGTCGCATCCATGAAAG-3′) and antisense (5′-TTAAACGCAGCTCAGTAACAGTCCG-3′); rat FasL sense (5′-CAGCCCCTGAATTACCCATGTC-3′) and antisense (5′-CACTCCAGAGATCAAAGCAGTTC-3′); rat Fas sense (5′-CAAGGGACTGATAGCATCTTTGAGG-3′) and antisense (5′-TCCAGATTCAGGGTCACAGGTTG-3′); rat glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) sense (5′-ACCACAGTCCATGCCATCAC-3′) and antisense (5′-TCCACCACCCTGTTGCTGTA-3′). The intactness of total RNA used for the RT reaction was tested by electrophoresis on a 1.1% agarose gel. The RT-PCR assays were first performed on identical amounts of RNA for each sample. Next, a dilution series (1:10, 1:100, and 1:1,000) of the cDNA was performed with GAPDH or actin primers. After normalizing and adjusting the cDNA to ensure that each sample yielded equal amount of GAPDH or actin signal, the actual PCR assays were performed with Fas and FasL primers. We also checked the linearity of the reactions to determine the optimal number of cycles for each PCR product. The PCR products, 507, 568, and 452 bases corresponding to nucleotides 80 to 586 of rat FasL cDNA, 1 to 568 of Fas cDNA, and 550 to 1001 of GAPDH cDNA, respectively (44, 78, 82), were separated by 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis and stained with ethidium bromide. To confirm their identities, the FasL and Fas PCR products were purified and sequenced. The nucleotide sequences were in full agreement with those expected for the corresponding fragments of the rat Fas and FasL cDNAs (data not shown). Standard procedures were used for Southern blot analysis (71).

Apoptosis assays.

For detection of apoptosis, PC12 cells were cultured on poly-L-lysine-coated Labtek II chamber slides. Apoptotic cells were detected with an in situ cell death detection kit incorporating FITC labeling and TUNEL) (in situ terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated dUTP nick-end labeling) as instructed by the manufacturer (Boehringer Mannheim). The fraction of apoptotic cells was also determined by the acridine orange-ethidium bromide dye uptake method (55). At least 200 cells were counted for each time point. Apoptotic cells were also detected by nuclear staining with Hoechst 33258 (2.5 μg/ml) in PBS after fixation in 4% paraformaldehyde. Cells were examined and photographed in a Zeiss Axioskop microscope as described above. CGCs cultured on poly-d-lysine coated Labtek II chamber slides (Nunc) treated as described, fixed in 100% methanol for 15 min, washed in PBS, and subsequently stained with hematoxylin (Sigma) for 10 min. Coverslips were mounted onto a glass slide in glycerol-PBS (1:1) and examined with a 100× objective of a Nikon light microscope. The number of apoptotic cells was expressed as a percentage of total neuronal cells visible in each field. These experiments were done five times in triplicate.

RESULTS

MEKK1Δ expression in PC12 cells results in JNK and p38 activation and apoptosis.

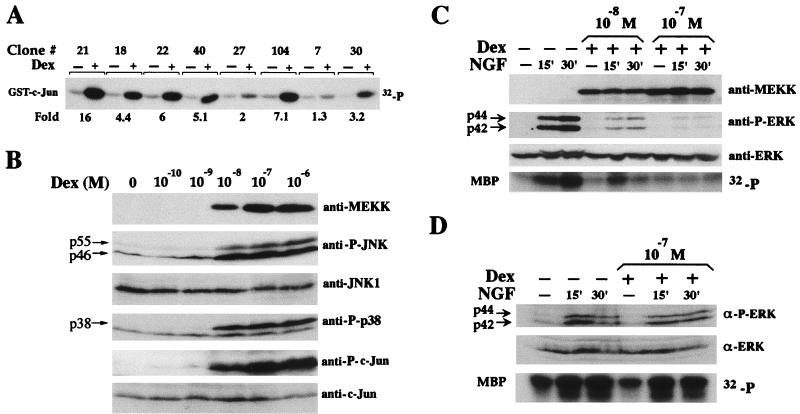

To examine the consequences of JNK (and p38) activation in the absence of ERK activity on PC12 cells, we took advantage of the finding that moderate MEKK1 overexpression results in JNK and p38 activation while having no stimulatory effect on ERK (57). We stably transfected PC12 cells with a pJ5Ω-MEKK1Δ construct, in which expression of the MEKK1 catalytic domain is controlled by the Dex-inducible MMTV promoter. Individual clones were screened by immunoblotting with anti-MEKK1 (data not shown) and by immunocomplex kinase assay for the ability of Dex to activate JNK (Fig. 1A). Much of the following work was done with clone 21 because of its high JNK activation ratio (16-fold). However, similar results were obtained with clones 18 and 22 (data not shown). Treatment of these cells with Dex results in dose-dependent MEKK1Δ induction, JNK and p38 activation, and c-Jun N-terminal phosphorylation (Fig. 1B). As previously found (57), MEKK1Δ expression in these cells did not activate ERK. Moreover, MEKK1Δ induction inhibited activation of ERK by either NGF (Fig. 1C), epidermal growth factor, or tetradecanoyl phorbol acetate (data not shown). No JNK or p38 activation or inhibition of ERK activity was observed in mock-transfected cells treated with Dex (Fig. 1D). Efficient MEKK1Δ induction and JNK activation required approximately 6 h of incubation with Dex and lasted for 3 to 5 days (data not shown). Inhibition of ERK activation required more than 6 h of incubation with Dex and therefore is not an immediate response to MEKK1Δ induction or JNK activation (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

JNK and p38 activation and ERK inhibition following MEKK1 expression in PC12 cells. (A) Individual clones of PC12 cells stably cotransfected with pJ5Ω-MEKK1Δ and RSV-Neo were examined for induction of JNK activity by Dex. After 24 h of incubation in the absence or presence of 10−8 M Dex, cell lysates were prepared and JNK activity was measured by immunocomplex kinase assay with GST–c-Jun(1-79) as a substrate. (B) Clone 21 cells were incubated with the indicated concentrations of Dex for 24 h, at which time they were lysed and the contents of MEKK1Δ, activated JNK, JNK1, activated p38, c-Jun phosphorylated at S63, and total c-Jun were determined by immunoblotting with specific antibodies. (C) Clone 21 cells were incubated in the absence or presence (10−8 and 10−7 M) of Dex for 24 h and then treated with or without NGF (50 ng/ml) for 15 and 30 min as indicated. Cell lysates were prepared, and the levels of MEKK1Δ, activated ERK, and total ERK2 were determined by immunoblotting. ERK enzymatic activity was determined by immunocomplex kinase assay with MBP as a substrate. (D) MMTV plasmid mock-transfected cells were incubated in the absence or presence of 10−7 M Dex for 24 h and then treated with or without NGF (50 ng/ml) for 15 and 30 min as indicated. Cell lysates were prepared, and the levels of MEKK1Δ, activated ERK and total ERK2 were determined by immunoblotting. ERK enzymatic activity was determined by immunocomplex kinase assay with MBP as a substrate.

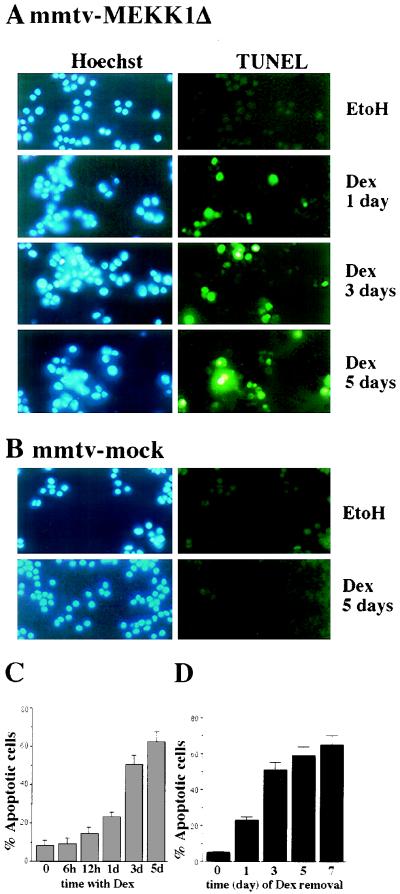

Microscopic examination of cells in which MEKK1Δ expression was induced revealed morphological changes characteristic of apoptosis, such as nuclear condensation and fragmentation and membrane blebbing. To detect DNA fragmentation, we used TUNEL; the karyophylic dye H33258 was used to visualize changes in nuclear morphology. MEKK1Δ expression resulted in induction of apoptosis, while no apoptotic cells were detected following Dex treatment of cells stably transfected with a mock expression vector (Fig. 2A and B). In addition, we determined the number of dead cells by acridine orange-ethidium bromide staining. Close to 50% of the cells underwent apoptosis after 3 days of Dex treatment, and approximately 60% of the cells were apoptotic after 5 days (Fig. 2C).

FIG. 2.

Induction of MEKK1Δ expression causes apoptotic cell death. (A) Clone 21 cells (2 × 104 per well) were cultured in the absence or presence of Dex (10−7 M) for the indicated times. DNA fragmentation was examined at the time indicated, using an in situ cell death detection assay (TUNEL). Nuclei were stained with Hoechst dye H33258. The cells were examined in a Zeiss Axioskop microscope with the appropriate filters. EtoH, ethanol. (B) PC12 cells stably transfected with empty pJ5Ω expression vector were incubated with ethanol or Dex (10−7 M) for 5 days and examined as described above. (C) Clone 21 cells were incubated with 10−7 M Dex for the indicated duration, at which point they were stained with a mixture of acridine orange and ethidium bromide and the percentage of apoptotic cells was determined. The results shown are averages of three experiments. (D) Clone 21 cells were cultured in the absence or presence of Dex (10−7 M). At the indicated times (in days) the induction medium was removed, and the cells were washed twice with PBS and then cultured in normal growth medium until day 7, at which time they were stained with acridine orange-ethidium bromide. A minimum of 200 cells were placed in a hemocytometer, and the relative numbers of apoptotic cells were determined. The results shown are averages of two experiments.

Efficient induction of apoptosis requires prolonged MEKK1Δ expression. When cells were incubated with Dex for only 1 day and then washed and placed in Dex-free medium for 6 more days, little cell death occurred (Fig. 2D). However, if cells were incubated with Dex for 3 days and then washed and placed in Dex-free medium for 4 more days, the extent of cell death was nearly as high as in cells that were subjected to continuous incubation with Dex for 5 to 7 days.

MEKK1Δ-induced cell death is dependent on c-Jun N-terminal phosphorylation and JNK activity.

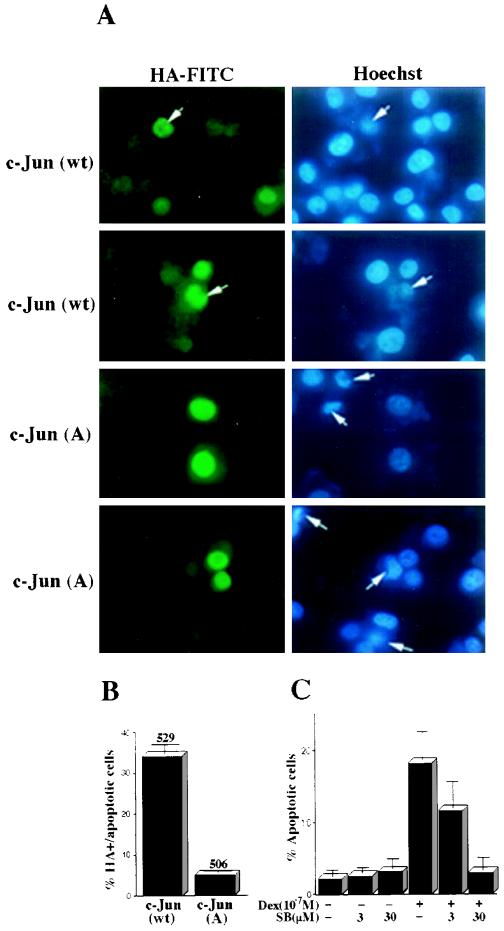

The delay between MEKK1Δ induction and JNK (or p38) activation and the onset of apoptosis, as well as the requirement for prolonged MEKK1Δ expression, suggested that new gene expression may be required to activate the apoptotic program. It was shown that inhibition of RNA or protein synthesis blocks apoptosis induced by NGF deprivation (54). However, as MEKK1Δ induction depends on RNA and protein synthesis, we were unable to use general inhibitors to examine the requirement for gene expression in this system. Because the c-Jun transcription factor is an important and specific target for JNK (40) and was suggested to be involved in apoptosis triggered by NGF withdrawal (20, 31), we examined whether a c-Jun mutant that is not phosphorylated by JNK could inhibit apoptosis of PC12 cells expressing MEKK1Δ. While transient expression of wt c-Jun in clone 21 cells did not affect the apoptotic response to MEKK1Δ, expression of c-Jun(A63/73) markedly decreased cell death (Fig. 3A and B). This protective effect was restricted to c-Jun(A63/73)-expressing cells; induction of cell death in surrounding cells not expressing this protein was not affected.

FIG. 3.

MEKK1Δ-induced cell death is blocked by phosphorylation-defective c-Jun mutant and SB202190. (A) Clone 21 cells (5 × 104) were cultured on chamber slides and transiently transfected with HA-tagged wt c-Jun or c-Jun(A63/73) expression vector. After 16 h, the cells were washed twice with PBS and incubated in the presence of 10−7 M Dex. After 3 more days, the cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100. Expression of FITC-labeled HA-c-Jun proteins was detected by indirect immunofluorescence using a monoclonal HA antibody. Nuclear morphology was determined by staining with Hoechst dye H33258. The arrows indicate cells with apoptotic morphology, which in the case of wt c-Jun are also positive for HA-c-Jun expression. However, in the case of c-Jun(A63/73), only 5% of the HA-positive cells have apoptotic morphology. (B) The results of the experiments shown above were quantitated by counting six independently transfected cultures, 80 to 90 cells each. The total numbers of transfected cells that were counted are indicated above each column. (C) Clone 21 cells were induced with or without 10−7 M Dex in the absence or presence of SB202190 (SB; 3 or 30 μM) for 6 h, followed by two washes to remove the drug. Dex-containing medium was added for an additional 18 h; then the cells were stained with acridine orange-ethidium bromide and the percentage of apoptotic cells was determined. The results are averages of three experiments.

Another way to examine the involvement of p38 or JNK in a biological process is to use specific inhibitors of these MAPKs. The pyridinyl imidazole compound (SB202190) was reported to be a specific p38 inhibitor (47). However, when applied to cells at 30 μM, SB202190 or related compounds also inhibit JNK activity (38, 89) and possibly other protein kinases. We incubated clone 21 cells with or without Dex and in the absence or presence of SB202190. While 3 μM SB202190 yielded a partial protective effect, incubation with 30 μM SB202190 resulted in complete protection against MEKK1Δ-induced apoptosis (Fig. 3C). At 3 μM, SB202190 did not inhibit JNK activity, detected by c-Jun phosphorylation at serine 63, while at 30 μM it fully inhibited JNK activity (Fig. 4B).

FIG. 4.

Expression of MEKK1Δ causes induction of FasL and thereby leads to apoptosis. (A) Clone 21 cells were incubated with 10−7 M Dex, and total cellular RNA was extracted at the indicated times. Expression of Fas, FasL, and GAPDH mRNAs was determined by quantitative RT-PCR using specific primers. To confirm the PCR product as a fragment of FasL cDNA, the reaction products were blotted and detected with a rat FasL cDNA probe (bottom panel). In addition, the nucleotide sequence of this fragment was determined and found to correspond to that of rat FasL cDNA (data not shown). d, days. (B) Clone 21 cells were incubated with or without 10−7 M Dex in the absence or presence of SB202190 (SB; 3 or 30 μM) for 6 h, followed by two washes to remove the drug. Dex-containing medium was added for an additional 18 h, at which time the cells were collected and lysed. After separation by SDS-PAGE, c-Jun phosphorylation was examined by immunoblotting with antibody against c-Jun phosphorylated at S63. Expression of FasL and GAPDH mRNAs was determined by RT-PCR (bottom two panels). (C) To determine the role of FasL in MEKK1Δ-induced apoptosis, clone 21 cells were cultured for the indicated times with Dex (10−7 M) in the presence of chimeric Fas-Fc protein (20 μg/ml) or purified IgG (20 μg/ml). At the indicated times, the cells were stained with acridine orange-ethidium bromide and the percentage of apoptotic cells was determined. The results shown are averages of two experiments done in duplicate.

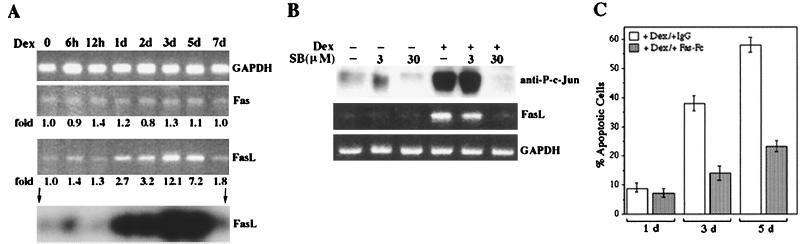

MEKK1Δ or NGF withdrawal lead to FasL induction.

A possible explanation for the protective effect of c-Jun(A63/73) is interference with the transcriptional activity of c-Jun or another transcription factor that requires JNK-mediated phosphorylation. One inducible protein that plays a critical role in induction of apoptosis during various pathological conditions is FasL (10, 27, 30, 80). We therefore examined whether induction of MEKK1Δ results in upregulation of FasL expression. Incubation of clone 21 cells with Dex resulted in induction of FasL mRNA (Fig. 4A), with kinetics that were similar to the kinetics of apoptotic cell death (Fig. 2C). By contrast, expression of Fas mRNA was constitutive. Incubation of Dex-treated clone 21 cells with 30 μM SB202190 interfered with induction of FasL mRNA (Fig. 4B). At 3 μM, SB202190 did not inhibit FasL induction.

To determine whether FasL induction played a causal role in the apoptotic response, we incubated the cells with a chimeric Fas-Fc protein. This protein protects cells against FasL-triggered apoptosis, most likely by sequestering it and thus preventing its binding to functional receptors (Fas) on the cell surface (6, 77). Incubation of clone 21 cells with chimeric Fas-Fc but not with control immunoglobulin (immunoglobulin G [IgG]) conferred considerable protection (approximately threefold decrease in cell death) against Dex-induced apoptosis (Fig. 4C).

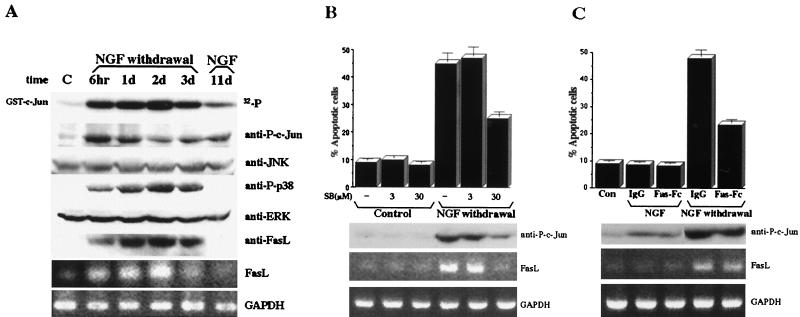

We tested whether a more physiological paradigm, such as NGF withdrawal, which causes apoptosis of PC12 cells and primary sympathetic neurons, leads to induction of FasL. PC12 cells were incubated in the presence of NGF for 11 days, at which point extensive neuronal differentiation occurred (data not shown). Removal of NGF and incubation with NGF neutralizing antibody resulted in increased JNK and p38 activities peaking after 1 to 2 days (Fig. 5A) and extensive apoptosis (data not shown). JNK activity and c-Jun phosphorylation after NGF withdrawal were severalfold higher than in cells kept in NGF for 11 days, and the latter had higher activity than nontreated PC12 cells. Stimulation of JNK activity in response to NGF withdrawal was followed by induction of FasL mRNA and protein (Fig. 5A). Despite prolonged JNK activation, no FasL expression or apoptosis was detected in cells that were continuously incubated with NGF (Fig. 5A, lane 11d).

FIG. 5.

JNK and p38 activation and FasL induction in response to NGF withdrawal. (A) PC12 cells cultured on poly-l-lysine/laminin-coated plates were incubated with or without (lane C) NGF (50 ng/ml) for 11 days, at which time the cells were carefully washed with NGF-free medium and incubated for 6 h (6hr), 1 day (1d), 2 days (2d), and 3 days (3d) with neutralizing NGF (2.5S) antibodies (1:4,000). As an additional control, PC12 cells were incubated with NGF for 11 days before harvesting (lane NGF, 11d). The cells were collected and lysed, and the level of JNK activity was determined by immunocomplex kinase assays with GST–c-Jun(1-79) as a substrate. The levels of activated p38, c-Jun phosphorylated at S63, JNK1, and ERK2 and of FasL expression were determined by immunoblotting with specific antibodies (top six panels). The levels of FasL and GAPDH mRNAs were determined by RT-PCR using extracts from cultures treated in parallel to those used for protein analysis (bottom two panels). (B) PC12 cells were subjected to the same treatment as for panel A. The lane labeled Control represents PC12 cells cultured without NGF. One hour prior to NGF withdrawal, the cells were incubated with or without SB202190 (SB; 3 or 30 μM) for 6 h. The cells were then washed to remove the drug, and NGF-free medium was added for an additional 18 h. After 1 day of NGF withdrawal, the cells were stained with acridine orange-ethidium bromide and the percentage of apoptotic cells was determined. The level of c-Jun phosphorylated at S63 was determined by immunoblotting, and FasL and GAPDH mRNA levels were determined by RT-PCR. The results in the top panel are averages of three experiments. (C) PC12 cells were treated as described for panel A. Purified IgG or chimeric Fas-Fc protein (20 μg/ml) was added 12 h prior to and during the time of NGF withdrawal or to cells that were continuously incubated with NGF. The lane labeled Con represents PC12 cells cultured without NGF. After 1 day, the cells were stained with acridine orange-ethidium bromide and the percentage of apoptotic cells was determined. The levels of c-Jun phosphorylated at S63, FasL, and GAPDH mRNAs were examined as described above. The results in the top panel are averages of three experiments.

To test whether JNK activation was linked to FasL induction in this system, we incubated postmitotic PC12 cells with SB202190 prior to NGF removal. When used at 30 μM, SB202190 inhibited FasL induction and c-Jun phosphorylation (Fig. 5B). In addition, incubation with 30 μM SB202190 partially protected PC12 cells against apoptosis induced by NGF withdrawal (Fig. 5B). Incubation of postmitotic PC12 cells following NGF removal with Fas-Fc (40 μM) also resulted in a considerable reduction in cell death (Fig. 5C). Due to a nonspecific cytotoxic effect (48a), the cells could not be incubated with SB202190 for longer than 6 to 8 h. Thus, we could not determine whether longer incubation with this compound would result in more extensive protection.

gld CGCs are less sensitive to induction of apoptosis after survival factor withdrawal.

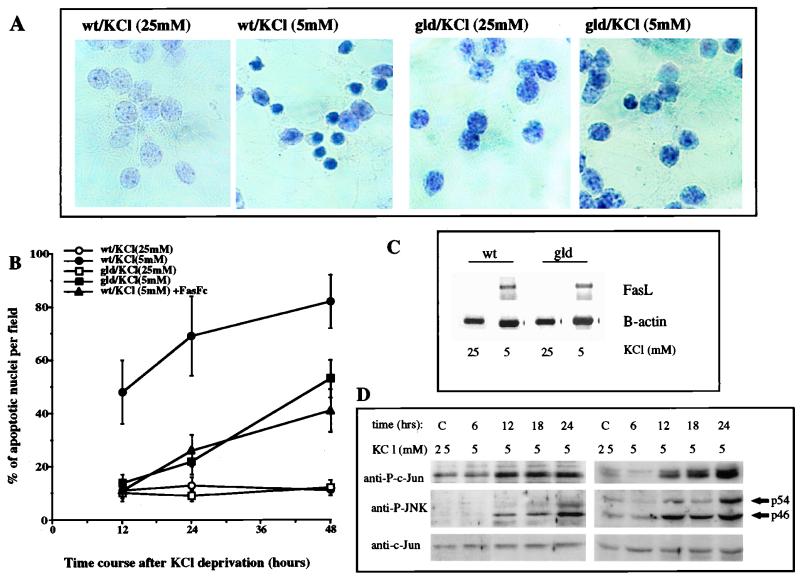

The results described above suggest that FasL is an important mediator of neuronal apoptosis caused by withdrawal of survival factors. To examine this point more critically, we used primary cultures of CGCs derived from wt or gld C3H/HeJ mice. The latter harbor a loss-of-function mutation in the FasL gene (gld) which renders its product nonfunctional because it can no longer bind to Fas (80). Survival of CGCs requires culturing in the presence of 25 mM KCl, which causes membrane depolarization and provides a survival signal (19). Once the K+ concentration is reduced to 5 mM, mature differentiated CGCs undergo apoptosis (19). CGCs isolated from wt and gld mice were cultured in the presence of 25 mM KCl. After 7 days, approximately 90% of the CGCs were alive and differentiated. These cells were either kept in 25 mM KCl or placed in medium containing 5 mM KCl. Incubation in the presence of 5 mM KCl caused wt CGCs to undergo extensive apoptosis such that within 24 h approximately 70% of the cells exhibited apoptotic morphology (Fig. 6A and B). By contrast, only 20% of the CGCs isolated from gld mice were apoptotic after 24 h in the presence of 5 mM KCl, whereas the basal level of apoptosis in either wt or gld CGCs maintained in 25 mM KCl was very similar, approximately 10% (Fig. 6B).

FIG. 6.

Neurons from gld mice are less sensitive to induction of apoptosis following KCl withdrawal. (A) Detection of apoptotic nuclei by hematoxylin staining 12 h after KCl withdrawal. CGCs of wt type and gld C3H/HeJ mice were cultured in 25 mM KCl for 7 days, at which time the KCl concentration was lowered to 5 mM. (B) Time course of appearance of apoptotic nuclei in wt and gld CGC cultures after KCl deprivation, with and without addition of Fas-Fc (40 μM). Apoptotic nuclei were detected by hematoxylin staining, and their frequency as a percentage of the total neuronal population was determined. Five fields were counted for each experiment; all experiments were repeated five times in triplicate. (C) RT-PCR analysis of FasL mRNA expression in wt and gld CGC cultures under control conditions (25 mM KCl) and 12 h after KCl deprivation (5 mM KCl). The number of PCR cycles was determined as described in Materials and Methods, and β-actin mRNA was used as a control. (D) Parallel samples of CGCs treated as described above were collected and lysed, and the levels of c-Jun phosphorylation at S63, activated JNK, and total c-Jun were determined by immunoblotting.

It is also important to note that gld CGCs were not entirely resistant to induction of apoptosis and that after 48 h in 5 mM KCl approximately 50% of the cells exhibited apoptotic morphology, whereas 80% of the wt CGCs were apoptotic at this time point. Incubation of wt CGCs with Fas-Fc produced similar results: a clear delay in the onset of apoptosis in response to KCl withdrawal and a decrease in its frequency, especially at the earlier time points (12 and 24 h). Only 25% of wt CGCs incubated in 5 mM KCl in the presence of Fas-Fc were apoptotic after 24 h, in comparison to 70% of the CGCs that were not treated with Fas-Fc. After 48 h, approximately 40% of the wt CGCs kept in 5 mM KCl and Fas-Fc were apoptotic, in comparison to 80% of the CGCs incubated without Fas-Fc (Fig. 6B).

As found in PC12 cells, incubation of CGCs in 5 mM KCl resulted in induction of FasL expression which was detected within 12 h (Fig. 6C). In this case no obvious differences were found between wt and gld CGCs, indicating that the signaling pathway leading to FasL induction is functional in these cells. In support of this conclusion, we find that culture of either wt or gld CGCs in 5 mM KCl results in similar levels of JNK activation and c-Jun N-terminal phosphorylation (Fig. 6D). The kinetics of JNK activation and c-Jun N-terminal phosphorylation correlate with the kinetics of apoptosis induction in wt CGCs (compare Fig. 6B and D). The CGCs also express Fas mRNA, but unlike FasL, these transcripts are expressed constitutively, as in PC12 cells (Fig. 4A and data not shown). These results indicate that FasL upregulation plays an important role in induction of apoptosis in wt CGC cultured in 5 mM KCl and that the pathway triggered by KCl withdrawal exhibits the same hallmarks as the pathway triggered by NGF withdrawal from differentiated postmitotic PC12 cells.

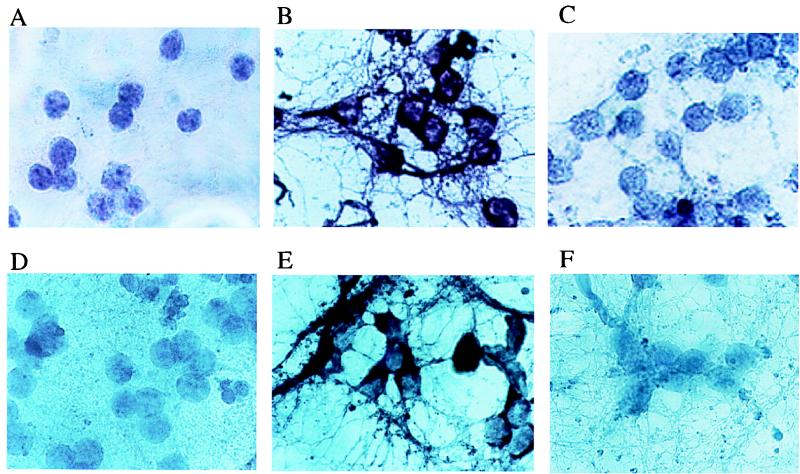

Microscopic examination of the primary cultures indicates that approximately 95% of the cells are typical CGCs, while the remainder appear to be glial cells (data not shown). In situ hybridization with FasL and c-jun probes confirmed that the major cell type in which these transcripts were induced after incubation in 5 mM KCl was neuronal (Fig. 7). Although the increase in c-jun mRNA is quite high (Fig. 7D and E), the increase in the total amount of c-Jun protein is not as high (Fig. 6D). Such discordance between induction of c-jun mRNA and c-Jun protein was described previously (1). It should be noted, however, that at early time points (6 to 8 h) after placement of the cultures in 5 mM KCl, the first cells to react positively with the FasL probe have glial rather than neuronal morphology (data not shown). While these cells may contribute to the initiation of the apoptotic response (see Discussion), our results, nevertheless, demonstrate that neuronal cells such as CGCs have the capacity to express FasL and respond to it.

FIG. 7.

FasL and c-Jun mRNA are upregulated upon KCl withdrawal. In situ hybridization using probes for FasL (A to C) and c-jun (D to F) mRNAs was performed on CGCs cultured in the presence of 25 mM KCl (A and D) or on CGCs incubated for 12 h in medium containing only 5 mM KCl (B, C, E, and F). As a specificity control, the cells in panels C and F were hybridized to the probes in the presence of a 10-fold excess of unlabeled competitor.

DISCUSSION

The results described above chart a signaling pathway that explains how activation of JNK following stress or elimination of survival factors can lead to neuronal apoptosis. Previous studies have indicated that induction of c-jun transcription and elevated c-Jun expression are associated with apoptosis in sympathetic neurons, differentiated PC12 cells (which closely resemble sympathetic neurons), and central neurons. In addition to a correlation between c-Jun induction and neuronal cell death, interference with c-Jun function either by expression of dominant-negative c-Jun mutants or microinjection of neutralizing c-Jun antibodies protect sympathetic neurons or postmitotic PC12 cells from apoptosis induced by NGF withdrawal or MEKK expression (20, 31, 93). The most conclusive evidence for the involvement of JNK in neuronal apoptosis is provided by the phenotype of mice that are deficient in the neuron-specific JNK3 isoform (94). While these mice are apparently normal in their gross and neurologic anatomies, they are resistant to induction of hippocampal neuron apoptosis by injection of kainic acid (94), a potent glutamate agonist (3).

These studies, however, did not explain how JNK activation (which can be elicited by kainic acid administration or removal of survival signals) can trigger apoptosis. The molecular mechanism responsible for execution of the apoptotic program appears to be universally conserved (58, 59). A key step is activation of the caspase cascade, which occurs in the cytoplasm (61). Thus, it was not clear how interference with c-Jun function in the nucleus can prevent caspase activation. One possible explanation for this quandary is that elevated c-Jun expression and transcriptional activity (through JNK-mediated phosphorylation) (40) serve to induce the transcription of a gene(s) whose product triggers the apoptotic process. Indeed, it was previously shown that inhibitors of RNA and protein synthesis protect sympathetic neurons from death caused by NGF withdrawal (54). The experiments described above demonstrate that an important mediator of cell death either in PC12 cells or CGCs undergoing apoptosis in response to either direct activation of the JNK cascade or withdrawal of survival signals (KCl or NGF) is FasL. Interference with binding of FasL to its receptor, Fas, through incubation with the chimeric Fas-Fc protein, which acts as a molecular decoy (6, 77), results in significant but incomplete protection of both cell types from apoptosis. Binding of FasL to Fas rapidly activates the apoptotic machinery through a series of protein-protein interactions (11, 58, 87). The time delay required for maximal FasL induction provides an attractive explanation for why stress-induced neuronal apoptosis is a rather slow process in comparison to apoptosis induced by direct Fas activation. The strongest evidence for the involvement of FasL in neuronal apoptosis comes from comparing the responses of CGCs derived from wt and gld mice after KCl withdrawal. The survival of such neurons depends on cultivation in the presence of 25 mM KCl (a depolarizing K+ level), and once placed in 5 mM KCl they undergo apoptosis within 12 to 24 h (19). Both the onset and the rate of apoptosis are significantly decreased in CGCs derived from gld mice, which express a nonfunctional FasL protein (80). Furthermore, apoptosis in wt CGC caused by KCl withdrawal is attenuated upon incubation in the presence of Fas-Fc (Fig. 6A and B).

Expression of FasL, like other members of the TNF family to which it belongs (76), is inducible (58, 59, 78). Recent results indicate that, similar to expression of TNF (66, 79), expression of FasL is transcriptionally regulated and that transcription factors NF-κB and AP-1 play an important role in this induction process (21, 42). These results also suggest that activation of the JNK pathway is required for induction of FasL promoter activity in response to various genotoxic stimuli (21, 42). We find that in both CGCs and PC12 cells, JNK activation in response to elimination of survival signals, as diverse as 25 mM KCl and NGF, occurs with kinetics that are consistent with a causal role in FasL induction. Treatment of PC12 cells with an inhibitor of p38 and JNK (and possibly other protein kinases), SB202190, at a dose that inhibits both JNK and p38 but not at a dose that inhibits only p38 results in inhibition of both JNK activity measured by c-Jun N-terminal phosphorylation and FasL induction in response to either MEKK1 expression (Fig. 4B) or NGF withdrawal (Fig. 5B). A likely mediator of FasL induction in this case is the N-terminally phosphorylated c-Jun protein, a component of transcription factor AP-1 (40). This possibility is supported by the strong correlation between c-Jun N-terminal phosphorylation in the three experimental systems that we examined, FasL induction, and the onset of apoptosis. In addition, we find that expression of a nonphosphorylatable c-Jun mutant, c-Jun(A63/73), protects PC12 cells from apoptosis caused by MEKK1 activation (Fig. 3A and B). These results suggest that an important downstream mediator leading from JNK activation to FasL induction is the N-terminally phosphorylated c-Jun transcription factor. A clear demonstration of the role of JNK in AP-1 activation is provided by the jnk3−/− mice, which exhibit a large decrease in induction of an AP-1-dependent reporter in response to kainic acid in comparison to their wt counterparts (94).

While the results described above strongly support a role for FasL as an important mediator of neuronal apoptosis caused by stress or elimination of survival factors, it is important to realize that the protection conferred by Fas-Fc or the gld mutation is incomplete. It is very likely that in addition to FasL, JNK activation may result in induction of several other death mediators that belong to the TNF family, including TNF itself (96), TRAIL (53, 90), or TRANCE (92). A role for AP-1 in TNF induction has been established (66, 79).

It is also important to note that both jnk3−/− (94) and gld (80) mice do not exhibit any obvious behavioral or neuroanatomical abnormalities. Therefore, it is unlikely that either JNK, FasL, or probably N-terminally phosphorylated c-Jun is involved in the apoptotic cell death that occurs during development of the central nervous system (CNS) (64). Most likely, the JNK-to-c-Jun-to-FasL pathway is used strictly to activate the apoptotic program in response to stress signals. One such form of stress is caused by the massive activation of glutamate receptors after kainic acid injection leading to death of hippocampal neurons (3). The jnk3−/− mice appear to be completely resistant to glutamate excitotoxicity (94). Massive activation of glutamate receptors may also be caused by cerebral ischemia-reperfusion (69). Indeed, it was recently found that cerebral ischemia-reperfusion results in JNK activation, c-Jun N-terminal phosphorylation, induction of FasL, and apoptosis, all within the same group of neurons affected by this lesion (33). Thus, it is quite possible that the JNK-to-c-Jun-to-FasL pathway plays an important role in triggering neuronal apoptosis in response to a variety of lesions and insults. Consistent with this hypothesis, gld mice were shown to be relatively resistant to development of experimental autoimmune encephalitis, not because they do not mount an immune response to the encephalitogenic peptide but because of reduced apoptosis in their CNS (86).

It has also been suggested that another cytokine, IL-1, is involved in neuronal cell death (25, 37, 50, 84). The major source of IL-1 and other proinflammatory cytokines in the CNS are microglial cells (37). Although glial cells are a minor contaminant in our primary CGC cultures, they appear to be the first cell type to express FasL mRNA after incubation in 5 mM KCl (data not shown). While they may be a minor contributor to the apoptotic response seen in this culture system, they are likely to be important players in the apoptotic response to CNS injuries due to their ability to produce IL-1. Although IL-1 does not bind and activate a death receptor, it is a potent JNK and NF-κB activator (18, 29) and known to be capable of inducing members of the TNF family (8). The exact source of FasL and other death mediators produced in response to various neuronal injuries remains to be determined. It is also not yet clear whether FasL and related factors act in an autocrine or a paracrine manner in the experimental systems that we have used. Nevertheless, our experiments show that neuronal cells can produce FasL and respond to it. The description of the JNK to c-Jun to FasL neuronal cell death pathway and its further exploration are likely to have important practical implications, as it appears that interference with at least two components of this pathway can prevent or decrease the extent of several cases of stress-induced neuronal apoptosis.

Finally, as a word of caution, it is important to realize that not every situation that leads to JNK activation or c-Jun N-terminal phosphorylation results in FasL induction and apoptosis. For instance, we find that treatment of PC12 cells with NGF also leads to JNK activation, but in this case no FasL induction or apoptosis ensues (Fig. 5A and data not shown). Most likely, NGF activates protective pathways such as the one mediated by the protein kinase AKT (23). Alternatively, NGF either fails to activate additional signals that could be required along with JNK activation for FasL induction or may generate signals that interfere with the ability of activated JNK to induce FasL. Like other MAPKs, the biological effects of JNK activation are cell type dependent. In other cell types, therefore, these protein kinases may be involved in cell proliferation or even protection from apoptosis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The first two authors contributed equally to the work.

We thank A. Minden for the pJ5Ω-MEKK1Δ construct and S. Nagata for the rat FasL cDNA and Fas-Fc construct.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants ES04151 and ES06376 (to M.K.) and CA69381 (to D.R.G.). H.L. was supported by the Lucille Markey Foundation and Molecular Endocrinology training grants. E.B. was supported by NIH grant GM52735 (to D.R.G.). Y.K. was supported by the Ministry of Education, Japanese Government, and F.-X.C. was supported by the French and Swiss Leagues against Cancer.

REFERENCES

- 1.Angel P, Hattori K, Smeal T, Karin M. The jun proto-oncogene is positively autoregulated by its product, Jun/AP-1. Cell. 1988;55:875–885. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90143-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Angel P, Karin M. The role of Jun, Fos and the AP-1 complex in cell proliferation and transformation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1991;1072:129–157. doi: 10.1016/0304-419x(91)90011-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ben-Ari Y. Limbic seizure and brain damage produced by kainic acid: mechanisms and relevance to human temporal lobe epilepsy. Neuroscience. 1985;14:375–403. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(85)90299-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Binétruy B, Smeal T, Karin M. Ha-Ras augments c-Jun activity and stimulates phosphorylation of its activation domain. Nature. 1991;351:122–127. doi: 10.1038/351122a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bonfoco E, Leist M, Zhivotovsky B, Orrenius S, Lipton S A, Nicotera P. Cytoskeletal breakdown and apoptosis elicited by NO donors in cerebellar granule cells require NMDA receptor activation. J Neurochem. 1996;67:2484–2493. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1996.67062484.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brunner T, Mogil R, LaFace D, Yoo N J, Machboubi A, Echeverri F, Martin S J, Force W R, Lynch D H, Ware C F, Green D R. Cell-autonomous Fas(CD95)/Fas-ligand interaction mediates activation induced apoptosis in T-cell hybridomas. Nature. 1995;373:441–444. doi: 10.1038/373441a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cardone M H, Salvesen G S, Widmann C, Johnson G, Frisch S M. The regulation of anoikis: MEKK-1 activation require cleavage by caspases. Cell. 1997;90:315–323. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80339-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chao C C, Hu S, Peterson P K. Glia, cytokines, and neurotoxicity. Crit Rev Neurobiol. 1995;9:189–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen Y-R, Wang X, Templeton D, Davis R J, Tan T-H. The role of c-Jun N-terminal Kinase (JNK) in apoptosis induced by ultraviolet C and γ radiation. J Biol Chem. 1996;50:31929–31936. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.50.31929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chervonsky A V, Wang Y, Wong F S, Visintin I, Flavell R A, Janeway C A, Matis L A. The role of Fas in autoimmune diabetes. Cell. 1997;89:17–24. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80178-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chinnaiyan A M, Dixit V M. The cell-death machine. Curr Biol. 1996;6:555–562. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00541-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cleveland J L, Ihle J N. Contenders in Fas/TNF death signaling. Cell. 1995;81:479–482. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90068-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cobb M, Goldsmith E J. How MAP kinases are regulated. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:14843–14846. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.25.14843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cowley S, Paterson H, Kemp P, Marshall J C. Activation of MAP kinase is necessary and sufficient for PC12 differentiation and for transformation of NIH 3T3 cells. Cell. 1994;77:841–852. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90133-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davis R J. MAPKs: new JNK expands the group. Trends Biochem Sci. 1994;19:470–473. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(94)90132-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Degols G, Russell P. Discrete roles of the Spc1 kinase and the Atf1 transcription factor in the UV response of Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:3356–3363. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.6.3356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dérijard B, Hibi M, Wu I-H, Barrett T, Su B, Deng T, Karin M, Davis R J. JNK1: a protein kinase stimulated by UV light and Ha-Ras that binds and phosphorylates the c-Jun activation domain. Cell. 1994;76:1025–1037. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90380-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.DiDonato J A, Mercurio F, Rosette C, Wu-Li J, Suyang H, Ghosh S, Karin M. Mapping of the inducible IκB phosphorylation sites that signal its ubiquitination and degradation. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:1295–1304. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.4.1295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.D’Mello S R, Galli C, Ciotti T, Calissano P. Induction of apoptosis in cerebellar granule neurons by low potassium: inhibition of death by insulin-like growth factor I and cAMP. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:10989–10993. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.23.10989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Estus S, Zaks W J, Freeman R S, Gruda M, Bravo R, Johnson E M. Altered gene expression in neurons during programmed cell death: identification of c-jun as necessary for neuronal apoptosis. J Cell Biol. 1994;127:1717–1727. doi: 10.1083/jcb.127.6.1717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Faris M, Kokot N, Latinis K, Kasibhatla S, Green D R, Koretzky G A. The c-Jun N-terminal kinase cascade plays a role in stress-induced apoptosis in Jurkat cells by up-regulating Fas ligand expression. J Immunol. 1998;160:134–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fradesen A, Schousboe A. Development of excitatory amino acid induced cytotoxicity in cultured neurons. Int J Dev Neurosci. 1990;8:209–216. doi: 10.1016/0736-5748(90)90013-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Franke T F, Kaplan D R, Cantley L C. PI3K: downstream AKTion blocks apoptosis. Cell. 1997;88:435–437. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81883-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fraser A, Evan G. A license to kill. Cell. 1996;85:781–784. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Friedlander R M, Gagliardini V, Hara H, Fink K B, Li W, MacDonald G, Fishman M C, Greenberg A H, Moskowitz M A, Yuan J. Expression of a dominant negative mutant of interleukin-1 beta converting enzyme in transgenic mice prevents neuronal cell death induced by trophic factor withdrawal and ischemic brain injury. J Exp Med. 1997;185:933–940. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.5.933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Frisch S M, Vuori K, Kelaita D, Sicks S. A role for Jun-N-terminal kinase in anoikis; suppression by bcl-2 and crmA. J Cell Biol. 1996;135:1377–1382. doi: 10.1083/jcb.135.5.1377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Giordano C, Stassi G, De Maria R, Todaro M, Richiusa P, Papoff G, Ruberti G, Bagnasco M, Testi R, Galluzzo A. Potential involvement of Fas and its ligand in the pathogenesis of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Science. 1997;275:960–963. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5302.960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Glise B, Bourbon H, Noselli S. Hemipterous encodes a novel Drosophila MAP kinase kinase, required for epithelial cell sheet movement. Cell. 1995;83:451–461. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90123-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gupta S, Campbell D, Dérijard B, Davis R J. Transcription factor ATF2 regulation by the JNK signal transduction pathway. Science. 1995;267:389–393. doi: 10.1126/science.7824938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hahne M, Rimoldi D, Schroter M, Romero P, Schreier M, L.E. F, Schneider P, Bornand T, Fontana A, Lienard D, Cerottini J-C, Tschopp J. Melanoma cell expression of Fas(Ap0-1/CD95) Ligand: Implications for tumor immune escape. Science. 1996;274:1363–1366. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5291.1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ham J, Babij C, Whitfield J, Pfarr C M, Lallemand D, Yaniv M, Rubin L L. A c-Jun dominant negative mutant protects sympathetic neurons against programmed cell death. Neuron. 1995;14:927–939. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90331-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Han J, Lee J-D, Bibbs L, Ulevitch R J. A MAP kinase targeted by endotoxin and hyperosmolarity in mammalian cells. Science. 1994;265:808–811. doi: 10.1126/science.7914033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Herdegen T, Claret F-X, Kallunki T, Martin-Villalba A, Hunter T, Karin M. Lasting N-terminal phosphorylation of c-Jun and activation of c-Jun N-terminal kinases after neuronal injury. J Neurosci. 1998;18:5124–5135. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-14-05124.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Herskowitz I. MAP kinase pathways in yeast: for mating and more. Cell. 1995;80:187–197. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90402-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hibi M, Lin A, Smeal T, Minden A, Karin M. Identification of an oncoprotein- and UV-responsive protein kinase that binds and potentiates the c-Jun activation domain. Genes Dev. 1993;7:2135–2148. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.11.2135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hill C S, Treisman R. Transcriptional regulation by extracellular signals: mechanisms and specificity. Cell. 1995;80:199–211. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90403-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hu S, Peterson P K, Chao C C. Cytokine-mediated neuronal apoptosis. Neurochem Int. 1997;30:427–431. doi: 10.1016/s0197-0186(96)00078-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jacinto E, Werlen G, Karin M. Cooperation between Syk and Rac1 leads to synergistic JNK activation in T-lymphocytes. Immunity. 1998;8:31–41. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80456-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Johnson R S, Spiegelman B M, Hanahan D, Wisdom R. Cellular transformation and malignancy induced by ras requires c-Jun. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:4504–4511. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.8.4504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Karin M. The regulation of AP-1 activity by mitogen-activated protein kinases. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:16483–16486. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.28.16483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Karin M, Hunter T. Transcriptional control by protein phosphorylation: signal transmission from cell surface to the nucleus. Curr Biol. 1995;5:747–757. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(95)00151-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kasibhatla S, Brunner T, Genestier L, Echeverri F, Mahboubi A, Green D R. DNA damaging agents induce expression of Fas-ligand and subsequent apoptosis in T lymphocytes via the activation of NF-κB and AP-1. Mol Cell. 1998;1:1–20. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80054-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kayne P S, Sternberg P W. Ras pathways in Caenorhabditis elegans. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1995;5:38–43. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(95)90051-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kimura K, Wakatsuki T, Yamamoto M. A variant RNA species encoding a truncated form of Fas antigen in the rat liver. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;198:666–674. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kyriakis J M, Banerjee P, Nikolakaki E, Dai T, Rubie E A, Ahmad M F, Avruch J, Woodgett J R. The stress-activated protein kinase subfamily of c-Jun kinases. Nature. 1994;369:156–160. doi: 10.1038/369156a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lange-Carter C A, Pleiman C M, Gardner A M, Blumer K J, Johnson G L. A divergence in the MAP kinase regulatory network defined by MEK kinase and Raf. Science. 1983;260:315–319. doi: 10.1126/science.8385802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lee J C, Laydon J T, McDonnell P C, Gallagher T F, Kumar S, Green D, McNulty D, Blumenthal M J, Heys J R, Landvatter S W, Strickler J E, McLaughlin M M, Siemens I R, Fisher S M, Livi G P, White J R, Adams J L, Young P R. A protein kinase involved in the regulation of inflammatory cytokine biosynthesis. Nature. 1994;372:739–745. doi: 10.1038/372739a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lenczowski J M, Dominguez L, Eder A M, King L B, Zacharchuk C M, Ashwell J D. Lack of a role for Jun kinase and AP-1 in Fas-induced apoptosis. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:170–181. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.1.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48a.Le-Niculescu, H. Unpublished results.

- 49.Liu Z-G, Hsu H, Goeddel D V, Karin M. Dissection of TNF receptor1 effector functions: JNK activation is not linked to apoptosis while NF-κB activation prevents cell death. Cell. 1996;87:565–576. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81375-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Loddick S A, MacKenzie A, Rothwell N J. An ICE inhibitor z-VAD-DCB attenuates ischaemic brain damage in the rat. Neuroreport. 1996;7:1465–1468. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199606170-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Maeda T, Takekawa M, Saito H. Activation of yeast PBS2 MAPKK by MAPKKKs or by binding of an SH3-containing osmosensor. Science. 1995;269:554–558. doi: 10.1126/science.7624781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Marshall C J. Specificity of receptor tyrosine kinase signaling: transient versus sustained extracellular signal-regulated kinase activation. Cell. 1995;80:179–185. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90401-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Marsters S A, Pitti R M, Donahue C J, Ruppert S, Bauer K D, Ashkenazi A. Activation of apoptosis by Apo-2 ligand is independent of FADD but blocked by CrmA. Curr Biol. 1996;6:750–752. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(09)00456-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Martin D P, Schmidt R E, DiStefano P S, Lowry O H, Carter J G, Johnson E M. Inhibitors of protein synthesis and RNA synthesis prevent neuronal death caused by nerve growth factor deprivation. J Cell Biol. 1988;106:829–844. doi: 10.1083/jcb.106.3.829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.McGahon A J, Martin S J, Bissonnette R P, Mahboubi A, Shi Y, Mogil R J, Nishioka W K, Green D R. Studying apoptosis in vitro. In: Schwartz L M, editor. The end of the (cell) line: methods for the study of apoptosis in vitro. San Diego, Calif: Academic Press; 1995. pp. 172–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mesner P W, Epting C L, Hegarty J L, Green S H. A timetable of events during programmed cell death induced by trophic factor withdrawal from neuronal PC12 cells. J Neurosci. 1995;15:7357–7366. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-11-07357.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Minden A, Lin A, McMahon M, Lange-Carter C, Dérijard B, Davis R J, Johnson G L, Karin M. Differential activation of ERK and JNK mitogen-activated protein kinases by Raf-1 and MEKK. Science. 1994;266:1719–1723. doi: 10.1126/science.7992057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nagata S. Apoptosis by death factor. Cell. 1997;88:355–365. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81874-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nagata S, Golstein P. The Fas death factor. Science. 1995;267:1449–1456. doi: 10.1126/science.7533326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Natoli G, Costanzo A, Ianni A, Templeton D J, Woodgett J R, Balsano C, Levrero M. Activation of SAPK/JNK by TNF receptor 1 through a noncytotoxic TRAF2-dependent pathway. Science. 1997;275:200–203. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5297.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nicholson D W, Ali A, Thornberry N A, Vaillancourt J P, Ding C K, Gallant M, Gareau Y, Griffith P R, Labelle M, Lazebnik Y A. Identification and inhibition of the ICE/CED-3 protease necessary for mammalian apoptosis. Nature. 1995;376:37–43. doi: 10.1038/376037a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nishina H, Fischer K D, Radvanyi L, Shahinian A, Kakem R, Rubie E A, Bernstein A, Mak T W, Woodgett J R, Penninger J M. Stress-signalling kinase Sek1 protects thymocytes from apoptosis mediated by CD95 and CD3. Nature. 1997;385:350–352. doi: 10.1038/385350a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Piu, F., E. Shaulian, and M. Karin. 1998. Unpublished data.

- 64.Raff M C, Barres B A, Burne J F, Coles H S, Ishizaki Y, Jacobson M D. Programmed cell death and the control of cell survival: lessons from the nervous system. Science. 1993;262:695–700. doi: 10.1126/science.8235590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Raitano A B, Halpern J R, Hambuch T M, Sawyers C L. The Bcr-Abl leukemia oncogene activates Jun kinase and requires Jun for transformation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:11746–11750. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.25.11746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rhoades K L, Golub S H, Economou J S. The regulation of the human tumor necrosis factor alpha promoter region in macrophage, T cell, and B cell lines. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:22102–22107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Riesgo-Escovar J R, Jenni M, Fritz A, Hafen E. The Drosophila Jun-N-terminal kinase is required for cell morphogenesis but not for DJun-dependent cell fate specification in the eye. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2759–2768. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.21.2759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rodrigues G A, Park M, Schlessinger J. Activation of the JNK pathway is essential for transformation by the Met oncogene. EMBO J. 1997;16:2634–2645. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.10.2634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rothman S M, Olney J W. Glutamate and the pathophysiology of hypoxic-ischemic brain damage. Ann Neurol. 1986;19:105–111. doi: 10.1002/ana.410190202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rouse J, Cohen P, Trigon S, Morange M, Alonso-Llamazares A, Zamanillo D, Hunt T, Nebrada A R. A novel kinase cascade triggered by stress and heat shock that stimulates MAPKAP kinase-2 and phosphorylation of the small heat shock proteins. Cell. 1994;78:1027–1037. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90277-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Schreiber, M., A. Kolbus, F. Piu, J. Tian, U. Mohle-Steinlein, M. Karin, P. Angel, and E. F. Wagner. Functional interaction between c-Jun and p53 in cell cycle regulation. Submitted for publication.

- 73.Schreiber, M., and E. F. Wagner. 1998. Unpublished data.

- 74.Sluss H K, Han Z, Barrett T, Davis R J, Ip Y T. A JNK signal transduction pathway that mediates morphogenesis and an immune response in Drosophila. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2745–2758. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.21.2745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Smeal T, Binetruy B, Mercola D A, Birrer M, Karin M. Oncogenic and transcriptional cooperation with Ha-Ras requires phosphorylation of c-Jun on serines 63 and 73. Nature. 1991;354:494–496. doi: 10.1038/354494a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Smith C A, Farrah T, Goodwin R G. The TNF receptor superfamily of cellular and viral proteins: activation, costimulation, and death. Cell. 1994;76:959–962. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90372-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Suda T, Nagata S. Purification and characterization of the Fas-ligand that induces apoptosis. J Exp Med. 1994;179:873–879. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.3.873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Suda T, Takahashi T, Golstein P, Nagata S. Molecular cloning and expression of the Fas ligand, a novel member of the tumor necrosis factor family. Cell. 1993;75:1169–1178. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90326-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sung S J, Walters J A, Hudson J, Gimble J M. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha mRNA accumulation in human myelomonocytic cell lines. Role of transcriptional regulation by DNA sequence motifs and mRNA stabilization. J Immunol. 1991;147:2047–2054. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Takahashi T, Tanaka M, Brannan G I, Jenkins N A, Copeland N G, Suda T, Nagata S. Generalized lymphoproliferative disease in mice, caused by a point mutation in the Fas ligand. Cell. 1994;76:969–976. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90375-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Traverse S, Gomez N, Paterson H, Marschall C, Cohen P. Sustained activation of the mitogen-activated (MAP) kinase cascade may be required for differentiation of PC12 cells: comparison of the effects of nerve growth factor and epidermal growth factor. Biochem J. 1992;288:351–355. doi: 10.1042/bj2880351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Tso J Y, Sun X-H, Kao T, Reece K S, Wu R. Isolation and characterization of rat and human glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase cDNAs: genomic complexity and molecular evolution of the gene. Nucleic Acids Res. 1985;13:2485–2502. doi: 10.1093/nar/13.7.2485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Vaccarino F M, Alho H, Santi M R, Guidotti A. Coexistence of GABA receptors and GABA modulin in primary cultures of rat cerebellar granule cells. J Neurosci. 1987;7:65–76. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.07-01-00065.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Vasilakos J, Shivers B. Watch for ICE in neurodegeneration. Mol Psychiatry. 1996;1:72–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Verheij M, Bose R, Lin X H, Yao B, Jarvis W D, Grant S, Birrer M J, Szabo E, Zon L I, Kyriakis J M, Haimovitz-Friedman A, Fuks Z, Kolesnick R N. Requirement for ceramide-initiated SAPK/JNK signalling in stress-induced apoptosis. Nature. 1996;380:75–79. doi: 10.1038/380075a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Waldner H, Sobel R A, Howard E, Kuchroo V K. Fas- and FasL-deficient mice are resistant to induction of autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol. 1997;159:3100–3103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wallach D. Cell death induction by TNF: a matter of self control. Trends Biochem Sci. 1997;22:107–109. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(97)01015-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wassarman D A, Therrien M, Rubin G M. The Ras signaling pathway in Drosophila. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1995;5:44–50. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(95)90052-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Whitmarsh A J, Yang S-H, Su M S-S, Sharrocks A D, Davis R. Role of p38 and JNK mitogen-activated protein kinases in the activation of ternary complex factors. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:2360–2371. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.5.2360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wiley S R, Schooley K, Smolak P J, Din W S, Huang C P, Nicholl J K, Sutherland G R, Smith T D, Rauch C, Smith C A. Identification and characterization of a new member of the TNF family that induces apoptosis. Immunity. 1995;3:673–682. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90057-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Wisden W, Morris B J, editors. In situ hybridization for the brain. London, England: Academic Press Limited; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Wong B R, Rho J, Arron J, Robinson E, Orlinick J, Chao M, Kalachikov S, Cayani E, Bartlett F S I, Frankel W N, Lee S Y, Choi Y. TRANCE is a novel ligand of the tumor necrosis factor receptor family that activates c-Jun N-terminal kinase in T cells. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:25190–25194. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.40.25190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Xia Z, Dickens M, Raingeaud J, Davis R J, Greenberg M E. Opposing effects of ERK and JNK-p38 MAP kinases on apoptosis. Science. 1995;270:1326–1331. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5240.1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Yang D, Kuan C-Y, Whitmarsh A J, Rincon M, Zheng T S, Davis R J, Rakic P, Flavell R A. Absence of excitotoxicity-induced apoptosis in the hippocampus of mice lacking the Jnk3 gene. Nature. 1997;389:865–870. doi: 10.1038/39899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Yang X, Khosravi-Far R, Chang H Y B, Baltimore D. Daxx, a novel Fas-binding protein that activates JNK and apoptosis. Cell. 1997;89:1067–1076. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80294-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Yeh W-C, Shahinian A, Speiser D, Kraunus J, Billia F, Wakeham A, Luis de la Pompa J, Ferrick D, Hum B, Iscove N, Ohashi P, Rothe M, Goeddel D, Mak T W. Early lethality, functional NF-κB activation, and increased sensitivity to TNF-induced cell death in TRAF2-deficient mice. Immunity. 1997;7:715–725. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80391-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]