Abstract

Neuregulin (NRG)1 - ErbB receptor signaling has been shown to play an important role in the biological function of peripheral microvascular endothelial cells. However, little is known about how NRG1/ErbB signaling impacts brain endothelial function and blood-brain barrier (BBB) properties. NRG1/ErbB pathways are affected by brain injury; when brain trauma was induced in mice in a controlled cortical impact model, endothelial ErbB3 gene expression was reduced to a greater extent than that of other NRG1 receptors. This finding suggests that ErbB3-mediated processes may be significantly compromised after injury, and that an understanding of ErbB3 function would be important in the of study of endothelial biology in the healthy and injured brain. Towards this goal, cultured brain microvascular endothelial cells were transfected with siRNA to ErbB3, resulting in alterations in F-actin organization and microtubule assembly, cell morphology, migration and angiogenic processes. Importantly, a significant increase in barrier permeability was observed when ErbB3 was downregulated, suggesting ErbB3 involvement in BBB regulation. Overall, these results indicate that neuregulin-1/ErbB3 signaling is intricately connected with the cytoskeletal processes of the brain endothelium and contributes to morphological and angiogenic changes as well as to BBB integrity.

Keywords: Angiogenesis, blood brain barrier, endothelium, vascular biology

Introduction

The neuregulins constitute a large family of epidermal growth factor (EGF)-like growth factors that signal through ErbB receptor tyrosine kinases. To date, six neuregulin (NRG) genes have been identified (NRG1, NRG2, NRG3, NRG4, NRG5, NRG6), each of which generates multiple splice isoforms.1–3 In describing NRG functions, we will use NRG1 as the prototypical example, as it was the first discovered and best characterized, with diverse actions in multiple organs, in particular in the heart and the nervous system.3–9 Signaling through its complement of ErbB receptor tyrosine kinases, NRG1 mediates critical events in neurodevelopment and neuronal function, including differentiation, migration, and synaptic formation, as well as the regulation of myelination by oligodendroglial cells and modulation of microglial and astrocytic responses to injury.10–13 NRG1 is also important in vascular endothelial function in multiple organ systems14,15; however, its effects on brain endothelial function in health and disease are less well defined. Previous research showed that NRG1/ErbB signaling is integral to the physiology of brain microvascular endothelial cells, being involved in endothelial permeability, survival after injury, and adhesion molecule expression.14 In a mouse model of traumatic brain injury, NRG1 administration was associated with improved cognitive function16 and a protective effect towards blood brain barrier (BBB) function.17 However, the molecular mechanisms by which NRG1 protects the BBB is not well understood.

The BBB is a critical part of the neurovascular unit, comprised of brain microvascular endothelial cells with pericytes, astrocytes, microglia and neuronal cells and regulates the passage of substances and immune cells from the peripheral circulation to the brain parenchyma, thus safe-guarding brain homeostasis.18–20 It is exquisitely sensitive to damage by different injuries, and an understanding of these processes will lead to more effective treatments for BBB damage as well as to improved delivery of these therapies into the CNS.24 To investigate how NRG1 affects brain microvascular endothelial cells and their indispensable function in BBB integrity, we examined the role of ErbB3, one of the three known NRG1 receptors. NRG1 effects are mediated by ErbB2, ErbB3, and ErbB4 receptors which form functional dimers after activation. These dimers include ErbB2/3, Erb2/4, ErbB3/4, and ErbB4/4,4 each generating diverse downstream effects.1,18 ErbB2/ErbB3 is the most active dimer in the epithelial family,21 of which the endothelial cell is a member. Within the ErbB2/ErbB3 pair, ErbB3 contains the NRG-binding domain and is the focus of this study, in which we examined the effect of ErbB3 down-regulation on endothelial cytoskeletal organization, angiogenesis, migration, and permeability.

Methods

Cell culture

1. A primary human brain microvascular endothelial cell line (CSC cells) was purchased from Cell Systems Corporation, Kirkland, WA, USA. Cells from passages 6 to 12 were grown in Endothelial Basal Medium (EBM, from Lonza or Millipore) and supplemented with Endothelial cell Growth supplements including 5% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS). Cell studies were performed in the same media. All experiments were performed according to Biosafety guidelines at the Massachusetts General Hospital (Boston, MA). All cell culture wells were seeded equally and wells were randomized to control vs. experimental conditions with duplicates or triplicates per condition.

2. Primary human BMECs were isolated during operative treatment of epilepsy from healthy temporal or hippocampal tissue outside of the epileptogenic foci (Surgical specimens provided by Dr. Marlys Witte and Michael Bernas, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, USA).22 Informed consents from the donors (n = 4) were obtained and the procedures were approved by the Temple University Institutional Review Board. BMECs were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium containing 10% FBS, endothelial cell growth supplement (BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA), heparin (1 mg/mL, Sigma), amphotericin B (2.5 mg/mL), penicillin (100 U/mL), and streptomycin (10 mg/mL). Triplicate measurements were made for each sample.

Induction of controlled cortical impact (CCI)

C57BL/6J wild type male mice (8-12 weeks old) purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) were given free access to food and water and were housed in laminar flow racks in a temperature-controlled room with 12-hour day/night cycles. Mice were randomized to sham and injury groups (n = 3 per group). The mouse CCI model was used as previously described.23 Mice were anesthetized with 4% isoflurane, 70% N2O and balance O2 and placed in a stereotactic frame. Anesthesia was maintained via a nose opening in the tubing leading from the anesthesia box and isoflurane was titrated to quiet respirations and lack of toe pinch response at a level that avoids hypotension. A 5-mm craniotomy was performed over the left parietotemporal cortex and the bone flap removed. Controlled cortical impact was produced using a pneumatic cylinder with a 3-mm flat-tip impounder, velocity 6.0 m/s, and depth of 1.2 mm. Sham-injured mice received craniotomy without CCI. Following sham injury or CCI, the bone flap was discarded and the scalp sutured closed. Mice were returned to their cages to recover from anesthesia.

Isolation of mouse brain microvascular endothelial cells

Isolation of microvascular endothelial cells was performed as previously reported.24 All experiments were reviewed and approved by the Massachusetts General Hospital Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee). All animal protocols are consistent with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. They were housed in standard barrier housing with 12 hour day/night cycles with free access to food pellets and water. Study design and data analysis follow all appropriate ARRIVE guidelines and requirements. The experiments have been REPORTED in compliance with the ARRIVE guidelines (Animal Research: Reporting in Vivo Experiments) for how to REPORT animal experiments. The cortices of three C57BL6 adult mice, 16–18 weeks old (Charles River Laboratories,) were micro-dissected in Phosphate buffered saline (PBS). The cortices from each mouse was used to isolate microvascular endothelial cells from that mouse and therefore 3 endothelial samples were obtained. Meninges were removed and tissue was minced, then digested with collagenase/dispase (2 mg/ml; Roche # 10269638001) for 30 min at 37 °C with rotation, triturated after adding 2% FBS and DNase (0.25 mg/ml), and filtered with 40 µm cell strainer then centrifuged through 22% Percoll to remove myelin. The samples were incubated on ice for 15 min with allophycoerythrin (APC)-conjugated rat-anti-mCD31 (BD Biosciences catalog #551262; RRID: AB_398497, 1:50) to label endothelial cells, with PE-conjugated rat anti-mCD45(BD Biosciences catalog #553081, RRID: AB_394611, 1:200) and PE-conjugated rat anti-mCD41 (BD Biosciences #558040; RRID: AB_397004, 1:200) to exclude blood cells, megakaryocytes, and platelets. After washing, samples were resuspended in PBS with DAPI to exclude dead cells. Cells were sorted using a Becton Dickinson FACS Aria. All FACS gates were set using unlabeled cells, single color cells and isotype controls. The expected outcome was the expression pattern of ErbB2,3,4 n the endothelial cells.

Transfection with siRNA

CSC cells were grown in endothelial basal medium 2 supplemented with EGM2 SingleQuots (EBM-2; Lonza, Basel, Switzerland). At approximately 70% confluence, cells were transfected with human ErbB3 siRNA (Origene, #SR320065) or non-targeting control siRNA (Origene, #SR30004) – using Lipofectamine 2000 according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Life Technologies). When we began the project, we transfected the cells in Opt-MEM media (Fisher Scientific) x 6 hr and change back to EBM-2 medium till confluent. Over time, our lab evolved to transfect cells x 18 hr in EBM-2 media, resulting in slight changes in transfection rate. The transfection rate is listed under each individual experiment.

Cell viability assays

Cell suvival was assessed by the WST reduction assay (Dojindo, #CK04-13) , which meausres the amount of formazan formed, reflects the amount of mitochondrial dehydrogenase activity, a measure of cell viability. The cells were incubated with 10% (vol/vol) WST solution for 1 hr at 37 °C. Then the absorbance of the culture medium was measured with a microplate reader at a test wavelength of 450 nm and a reference wavelength of 630 nm. Prior to performing this assay, the cells were transfected with siRNA, expected to result in a 60% decrease in ErbB3 mRNA in ErbB3-silenced cells.

Incubation with NRG1

After transfection, media was changed to fresh endothelial media with growth factor supplements for 24 hr. After that the media was changed to EBM with 10% FBS for 2 hr, then 12.5 nM or 100 ng/ml of the active domain of NRG1-β1(R&D Systems, 396-HB-050) was added. After incubation at 37 °C for 20 minutes, the cells were lysed and prepared for immunoblotting.

Tube formation assay

A standard Matrigel assay was used to assess the number of tubes formed by the cells in this assay of angiogenesis. The tubes are capillary-like structures composed of endothelial cells. CSC cells (4*104 cells/well) were seeded in 48-well plates coated with growth factor- reduced Matrigel (Corning, #354230, and transfected with non-targeting siRNA or ErbB3 siRNA for 6 hr as described above, then incubated for 24-48 hr. The number of tubes per field was counted in three random fields from each well, by a researcher who was blinded to the identity of the groups. Prior to performing this assay, the cells were transfected with siRNA, expected to result in a 60% decrease in ErbB3 mRNA in ErbB3-silenced cells.

Immunoblotting

Cells were lysed using lysis buffer (Cell Signaling, #9803S) with protease- and phosphatase-inhibitors (Thermo-Fisher, #78425; Sigma, #5872). Proteins were separated using sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes, blocked with 5% skim milk for 1 hr, and incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies to: VE-Cadherin (Enzo, #alx-210-232) , occludin (Abcam, #ab64482), Claudin-5 (Abcam, #ab15106), pAKT (cell signalling, #9271S), AKT (cell signalling, #9272S ), pS6 (cell signalling, #2211S), S6 (cell signalling, #2217S) and β-actin (Sigma, #A5441). After washing and incubation with the secondary antibody, proteins were visualized with enhanced chemiluminescence (GE healthcare Bio-Science, #GERPN22 32) in the G-box system (Syngene, Frederick, MD, USA). The outcome parameter – the relative densities of bands - were analyzed using NIH Image J. Prior to performing this assay, the cells were transfected with siRNA, expected to result in a 60% decrease in ErbB3 mRNA in ErbB3-silenced cells.

Endothelial permeability assay

This assay measured the permeability of the endothelial layer plated on the transwell inserts. CSC cells were seeded in the collagen-coated transwell inserts (0.4 µm pore size, polycarbonate filter, Corning, Corning, NY, USA) and placed in wells of a 12-well plate. When 70% confluent, the cells were transfected with non-targeting or ErbB3 siRNA. After 48 hr, permeability was measured by adding 0.2 mg/ml of fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled dextran-40kDa (Sigma) to the apical compartment. The amount of fluorescent dextran-40 which has extravasated through the monolayer of endothelial cells was measured in 100µl of media taken from the basal compartment of the transwell system, and the amount quantified using a plate-reader for the fluorescence signal. Prior to performing this assay, the cells were transfected with siRNA to ErbB3, which is expected to result in a 60% decrease in ErbB3 mRNA in ErbB3-silenced cells.

Evaluation of cell morphology

Cells were grown to confluence and images were acquired at 200× magnification with a flourescent microsocope. Immunocytochemistry was performed using fluorscent-labeled phalloidin (Invitrogen), and with an antibody to the extracellular domain of VE-cadherin (ENZO, #alx-210–232), which outlines the cell border. Cell shape was observed visually, and quantified by choosing 25 cells randomly from each well (n = 3 experiments, with 2–3 wells per condition in each experiment). A 200× image was taken at the center of each well. The cells were randomly chosen by using cells that fell along an imaginary diagonal line in each image. The short and long of the cells were measured to determine the Feret ratio. This procedure was performed by a researcher who was blinded to the identity of the groups. Prior to performing this assay, the cells were transfected with siRNA, which is expected to result in >95% decrease in ErbB3 mRNA in ErbB3-silenced cells.

Assessment of microtubule assembly

Microtubule arrangement was visualized using overnight incubation with an antibody to α-tubulin (Sigma, #T9026), following by incubation with a fluorescent secondary antibody, after which images were obtained by a researcher who was blinded to the identity of the groups, using confocal microsocpy at the Ragon Institute (Cambridge, MA). Microtubule dis-assembly and re-assembly was induced and evaluated using previously reported procedures as follows.24,25 To promote microtubule dis-assembly, cells were removed from the 37 °C incubator and placed on ice for 15 min. To promote re-assembly, cells were returned to a 37 °C incubator for 15 min. After each step, representative plates of cells were assayed to determine relative levels of de-polymerized and polymerized α-tubulin. To extract the de-polymerized α-tubulin monomers, the cells were rinsed with PBS, then permeabilized with the addition of 100 µl of PEM buffer (80 mM PIPES, pH 6.8, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM MgCl2) with 0.1% Triton X-100 and 25% glycerol. After 3 min the PEM extraction buffer was collected, and the cells were rinsed with an additional 50 µl of PEM buffer, which was also collected and pooled with the initial extraction solution. The pooled solution contains all of the released soluble monomeric α-tubulin. To prepare for SDS-PAGE, 150ul of 2X SDS-PAGE sample buffer was added to each tube. Next, to release the assembled microtubules (polymerized tubulin) which now remain in the residual cell structures, 300 µl of 1X SDS-PAGE sample buffer then was added and collected using a cell scraper. The samples were boiled and equal amounts were loaded onto polyacrylamide gels, transferred to PVDF membranes, then probed using an anti- α-tubulin antibody (Sigma, #T9026) followed by secondary antibody - the initial extraction contains the solubilized monomers; the final extraction, using stronger detergent conditions, contains polymerized α-tubulin. The blots were developed using chemiluminescence, then scanned, and the optical density of protein bands were quantified using image J. The ratio of the monomer to the polymer forms of α-tubulin is compared between groups. Prior to performing this assay, the cells were transfected with siRNA, which is expected to result in a > 95% decrease in ErbB3 mRNA in ErbB3-silenced cells.

Scratch migration assay

This assay was used to measure cell migration across a gap induced by a scratch injury to the monolayer of cells. Cells were plated on 6 well plates, then transfected with either non-targeting siRNA or ErbB3 siRNA when about 70% confluent. When a confluent monolayer has been formed, an area devoid of cells was made by making a linear scratch in the well using a 10 µl pipette tip. Progression of cell migration into the gap field was monitored each day by phase contrast microscopy. Two areas of a 4X field were randomly selected and imaged in each well. Cell migration was evaluated by calculating the percentage of previously empty areas which are now occupied by migrated cells. This step was performed by a researcher who was blinded to the identity of the groups. Prior to performing this assay, the cells were transfected with siRNA, which is expected to result in a 60% decrease in ErbB3 mRNA in ErbB3-silenced cells.

qRT-PCR

The relative expression of the genes of interest was determined by the single ΔCt method using HPRT1 as reference gene. Total RNA was extracted from cells using RNeasy Plus Mini Kit (Qiagen, # 74134), and a reverse transcription of RNA to cDNA was performed using SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis System Kit (Invitrogen) as described by the manufacturer. Gene expression was quantified in triplicates using TaqMan probes (Applied Biosystems, #444557). qPCR was performed in on Applied Biosystems 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR system.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA)

NRG1 levels secreted by cells into cell culture media were measured using a NRG1 ELISA (R&D, # DY377). Prior to performing this assay, the cells were transfected with siRNA, with an expected 60% decrease in ErbB3 mRNA in ErbB3-silenced cells.

Statistics

All sets of continuous data were tested for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test, and fewer than 5% of the tests concluded that the set was non-normal at the 0.05 significance level, confirming that the data sets met the assumption of a normal distribution. Data was analyzed with one-way ANOVA followed by inter-group Tukey Honest Significant Difference post hoc test or with two-way ANOVA followed by Sidak multiple comparisons when more than 1 variable is compared. Data is presented as mean ± SD. Statistical significance was set at *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. All experiments are performed at least 3 times with duplicates or triplicates. Effect size was estimated to be 10–30% and SD was estimated to be <25%.

Results

ErbB2, ErbB3, and ErbB4 mRNA are expressed in brain microvascular endothelial cells

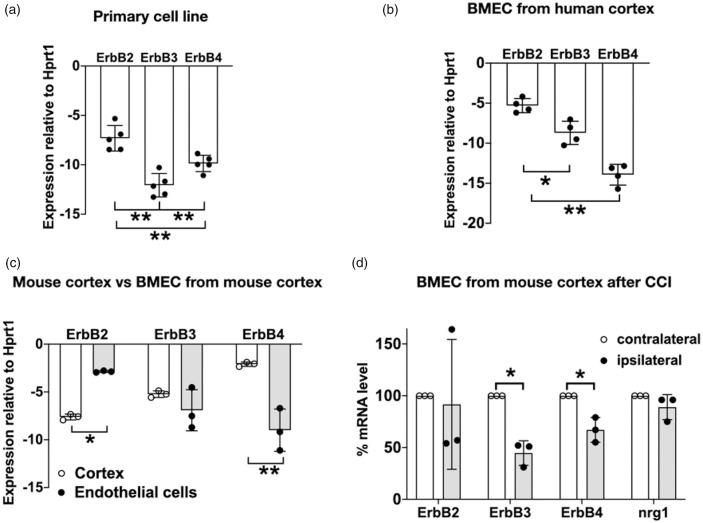

To determine whether the expression pattern of ErbB receptors is similar among different types of brain microvascular endothelial cells (BMECs), we surveyed cells from three sources - a commercially available primary human BMEC cell line (Figure 1(a)), human brain microvascular endothelial cells isolated from normal cerebral cortex (resected during surgery to remove a seizure focus from the hippocampus and propagated in culture for approximately 4 passages) (Figure 1(b)), and endothelial cells isolated from microvessels of mouse cerebral cortex24 (Figure 1(c)). In all these types of adult brain microvascular endothelial cells, mRNA of ErbB2, ErbB3, and ErbB4 was detected at low levels, with ErbB2 mRNA expression at a significantly higher level than ErbB3 and ErbB4. In the human BMEC cell line, ErbB3 was the least highly expressed of the ErbB receptors; however, in microvessels isolated from human cortex (Figure 1(b)) and mouse cortex (Figure 1(c)), ErbB3 was expressed at a higher level than ErbB4. Comparing mouse BMECs to whole cortex, endothelial cells expressed ErbB2 mRNA at a higher level (p<0.01), and ErbB4 at a lower level (p<0.01) than cortex, while the amount of ErbB3 mRNA was not statistically different between the endothelial isolate and cortex. This finding likely reflects the higher prevalence of ErbB4 receptors in neurons10,11 and glia,12,13 versus the higher prevalence of ErbB2 receptors in endothelial cells; whereas ErbB3 is expressed in both endothelial and glial cells.12,13 Of note, the endothelial specificity of the isolate was confirmed by cell-specific mRNA markers (Supplementary Figure 1). Within the isolated endothelial cells, ErbB2 mRNA was the most highly expressed, greater than that of ErbB3 (p < 0.05) and ErbB4 (p < 0.01). There was also a trend towards higher ErbB3 mRNA levels compared to ErbB4. This pattern is similar to that reported for other types of endothelial cells,26,27 with ErbB2/ErbB3 being the most active dimer pair.1,14,17,28 ErbB2 has strong kinase activity but lacks a ligand-binding domain, and transduces NRG1 signals only through dimerization with ErbB3 or ErbB4. Within the microvessels of human and mouse brain (Figure 1(b) and (c)), the prevalence of ErbB3 compared to ErbB4 suggests that it is the predominant NRG1-binding receptors of BMECs in vivo.

Figure 1.

ErbB2, ErbB3, and ErbB4 mRNA are expressed in brain microvascular endothelial cells. (a) A primary human brain microvascular endothelial cell line (commercially obtained from CSC Corporation) expresses ErbB2, ErbB3, and ErbB4; n=5; triplicates. (b) Primary human brain microvascular endothelial cells (BMEC) isolated from normal overlying cerebral cortex during surgery to remove a seizure focus from the hippocampus; n=4; triplicates. (c) Comparison of ErbB expression pattern in mouse cortex versus isolated BMEC from cortex: ErbB2 mRNA expression in BMEC was greater than that in cortex (*p < 0.05) and ErbB4 mRNA expression in BMEC is lower than that in cortex (**p < 0.01), n=3; triplicates. (d) ErbB2, ErbB3, ErbB4 and NRG1 gene expression in BMEC isolated from ipsilateral and contralateral hemisphere of injured mouse brain at 24hr after CCI. ErbB3 and ErbB4 gene expression is significantly decreased in ipsilateral vs contralateral hemisphere, (*p < 0.05), n=3, triplicates.

ErbB3 levels appear to be more significantly affected after brain injury. 24 hr after brain trauma was induced in mice using controlled cortical impact (CCI), mRNA level of ErbB3 and ErbB4 in the injured ipsilateral hemisphere were significantly decreased compared to the contralateral hemisphere (p < 0.05, Figure 1(d)). ErbB3 mRNA expression was decreased to a greater extent than ErbB4, suggesting that ErbB3-mediated processes may be more significantly compromised after injury, and that an understanding of ErbB3 function is important in the study of endothelial biology in the healthy and injured brain.

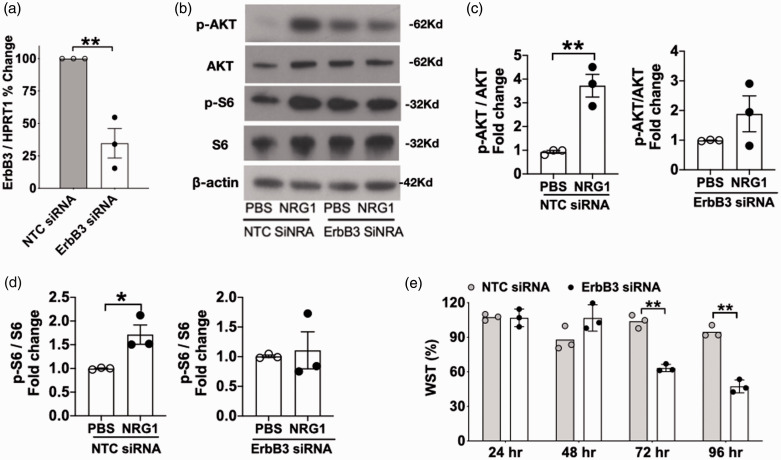

Endothelial ErbB3 gene silencing is associated with a decrease in NRG1-induced phosphorylation events, cell survival, and angiogenesis

Incubation with ErbB3 siRNA resulted in a 65% reduction in ErbB3 mRNA (p < 0.01, Figure 2(a)). At approximately 40 hr after transfection, cells were incubated for 20 min with the active domain of NRG1-β1 (12.5 nM) and cell lysates were collected for immunoblotting. NRG1-induced phosphorylation of Akt and of S6 kinase was decreased in ErbB3-siRNA transfected cells. After incubation with NRG1, control cells (cells transfected with non-targeting siRNA) exhibited a 5.9 fold increase in phosphorylation of Akt (p<0.05, Figure 2(b) and (c)) and a 1.7 fold increase in phosphorylation of S6 kinase (p<0.05, Figure 2(b) and (d)). In contrast, ErbB3-siRNA transfected cells did not exhibit a statistically significant increase in the phosphorylation of Akt or S6 kinase after incubation with NRG1. Since Akt and S6 are key regulators of growth, survival, and metabolism,29–32 we evaluated the effect of ErbB3 knock-down on cell viability at early and late time points. At 24 hr and 48 hr after transfection, cell survival was not affected by ErbB3 knockdown. At 72 hr and 96 hr, cell survival in ErbB3-silenced cells was decreased to 40% and 47%, respectively, when compared to the control siRNA group (Figure 2(e), p < 0.01). The phosphorylation levels of myosin light chain (MLC) was also examined. MLC is known to be involved in cytoskeletal pathways and is responsive to NRG1 signaling during conditions of cytokine-induced injury.14 Our results showed that baseline phosphorylation of MLC was decreased in ErbB3-siRNA transfected cells compared to controls (p < 0.05, Supplementary Figure 2), suggesting that cytoskeleton processes would be affected by changes in ErbB3 gene expression.

Figure 2.

Effect of ErbB3 siRNA on cell phosphorylation of Akt, S6 kinase, and cell viability. (a) ErbB3 mRNA expression was decreased by 60% after ErbB3 siRNA transfection (**p < 0.01). (b, c, d) After incubation with NRG1, control cells (transfected with non-targeting siRNA): 5.9 fold increase in pAkt (*p<.05;) and 1.7 fold increase in p S6 kinase (*p<.05). ErbB3-siRNA transfected cells: no increase. (e) ErbB3-siRNA transfected cells: decrease in viability at 72 h (***p < 0.001; n=3) and at 96h (***p < 0.001). n=3 expts, 1 well per condition.

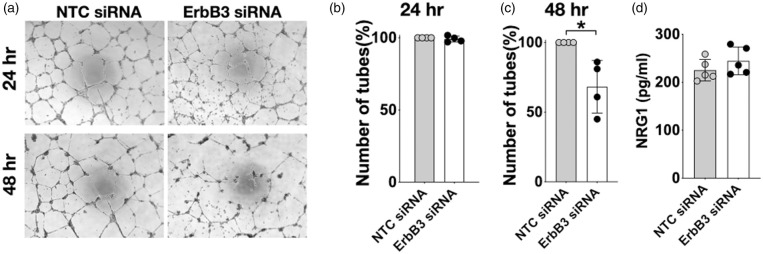

The effect of ErbB3 knock-down on the process of angiogenesis was another area of study. In a Matrigel angiogenesis assay, there was no difference in tube formation between control and ErbB3-silenced cells at 24 hr. However, the number of tubes in the ErbB3-siRNA treated group was significantly reduced at 48 hr compared to the control group (p < 0.05 Figure 3(a) to (c)). To further determine if the decrease in cell survival and in tube stability was related to changes in NRG1 levels in ErbB3-silenced cells, the amount of NRG1 that the cells secreted into the media was measured using ELISA. Of note, NRG1 was not one of the components included in the commercially available cell culture medium. No difference was seen in the amount of secreted NRG1 between ErbB3-silenced and control cells (Figure 3(d)), indicating that the compromise in cell viability and angiogenesis is attributable to a decrease in ErbB3 rather than a decrease in secreted NRG1, which provides autocrine signaling activity in these cells. These results indicate that ErbB3 is involved in cell survival and in the stability of tube structures formed in an angiogenesis assay.

Figure 3.

Effect of ErbB3 siRNA on tube formation in a Matrigel angiogenesis assay. (a) Representative images of Matrigel assay; (b, c) Comparing number of tubes at 24 hr and 48 hr after transfection in control vs. ErbB3-silenced cells: p = ns at 24 hr, *p < 0.05 at 48 hr, n=4, duplicates,(d) Secreted neuregulin-1(NRG1) level was not changed in control or ErbB3-silenced cells (p = ns, n=5; duplicates).

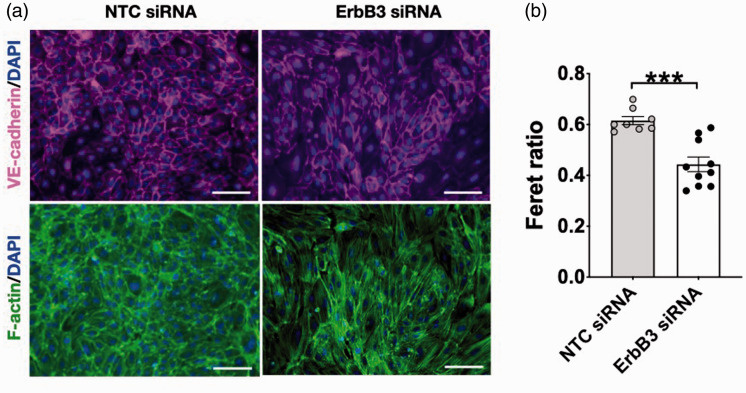

Reduction of ErbB3 gene expression results in changes in cell morphology, f-actin arrangement, and microtubule assembly

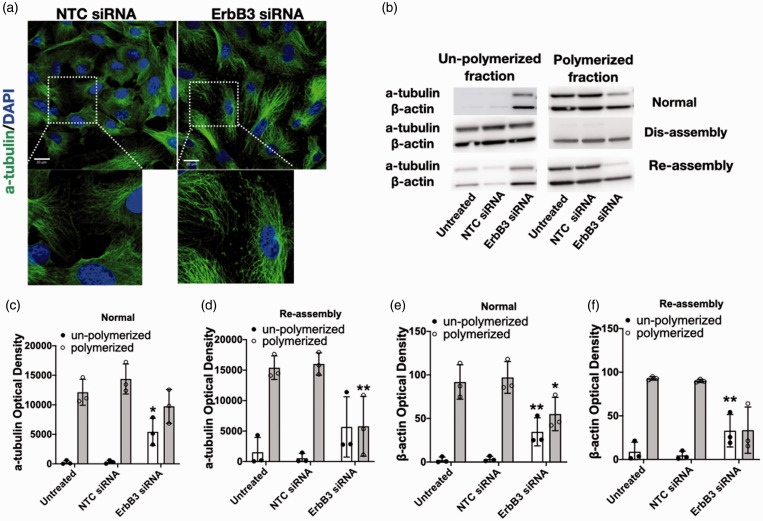

Equal numbers of cells were seeded for transfection by non-targeting or ErbB3 siRNA. By 40-48 hr after transfection, cells have formed a confluent monolayer which appeared visibly different when viewed through the light microscope. Control cells assumed a cuboidal or mildly elongated shape. In contrast, ErbB3-silenced cells assumed a much more elongated shape – reflected in a significant difference in the Feret ratio (p < 0.001; Figure 4(a) and (b)). The change in cell shape was accompanied by a trend towards larger cell size; however, the cell number at 24 hr was no different between the two groups when evaluated by counting the number of cell nuclei in each group (Supplementary Figure 3), which is consistent with the results of the WST assay (Figure 2(e)). The change in cell shape prompted an examination of the effects of ErbB3 silencing on the organization of f-actin and microtubules, which are important determinants of cell shape. Microtubule assembly was altered in ErbB3-silenced cells, as shown by immunocytochemistry using an antibody to α-tubulin. α-tubulin and β-tubulin polymerize into filaments which then form into microtubules. In control cells, microtubule fibers covered most of the cell surface. In ErbB3-silenced cells, microtubules appeared less uniform in length and do not cover the cell surface uniformly, leaving small areas of the cell with low microtubule density. Additionally, tubulin fragments were seen in the intercellular spaces between ErbB3-siRNA transfected cells, but not in control cells (Figure 5(a)). Immunoblotting also demonstrated differences in microtubule assembly. In control cells, the majority of α-tubulin was polymerized, with little remaining in the un-polymerized form. In ErbB3-silenced cells, the amount of polymerized α-tubulin was decreased, while the amount of un-polymerized tubulin was increased (p < 0.05; Figure 5(b) and (c)). To examine microtubule re-assembly, dis-assembly was first induced by placing the cells on ice for 15 min,25,33 after which depolymerization of α-tubulin was seen in all groups. After re-incubation at 37 °C for 15 min, the extent of microtubule re-polymerization differed among the groups. In un-treated cells and in control cells (cells transfected with non-targeting control siRNA), repolymerization was almost complete after 15 min at 37 °C; in ErbB3-silenced cells, re-polymerization was decreased by 56% (p < 0.01; Figure 5(b) and (d)).

Figure 4.

Effect of ErbB3 silencing on cell morphology. (a) Representative images of VE-cadherin and f-actin staining at 24 hr with control vs. ErbB3-silenced cells (scale bar = 100 µm). (b) Decreased Feret ratio with ErbB3 siRNA vs non-targeting siRNA (**p < 0.01); n=3 expts, duplicates or triplicates, total of 8–10 wells imaged per condition).

Figure 5.

Effect of ErbB3 silencing on microtubule assembly and f-actin arrangement. (a) Representative images of a-tubulin staining at 24 hr with control siRNA vs. ErbB3-siRNA (scale bar = 20µm). (b) Representative western blot of α-tubulin and β-actin polymerization states. (c) Quantification of α-tubulin polymerization in normal state. ErbB3-siRNA increased de-polymerization of α-tubulin compared to non-targeting control siRNA (*p < 0.05, n=3). (d) Quantification of α-tubulin polymerization after re-assembly in setting of cold exposure. α-tubulin re-polymerization is decreased in ErbB3-silenced cells compared to untreated and control cells (**p < 0.01, n=3). (e) Quantification of β-actin polymerization in normal state. ErbB3-silenced cells have increased de-polymerization (soluble form) of β-actin compared to control cells (**p < 0.01, n=3). (f) Quantification of β-actin polymerization after re-assembly in setting of cold exposure. Un-polymerized β-actin is significantly higher in ErbB3-silenced cells (**p < 0.01, n=3).

Differences in f-actin structure were also noted in ErbB3-silenced cells. In control cells, cortical actin, which confers stability to the cell structure, constituted a prominent feature of f-actin. In ErbB3-silenced cells, stress fibers appeared more prominent than cortical actin on immunocytochemistry (Figure 5(a)). Immunoblotting confirmed that actin assembly was also affected. At baseline, a lower percentage of actin was presented in the polymerized form in the cytoskeleton of ErbB3-silenced cells than in control cells (p < 0.01; Figure 5(b) and (e)). Cold exposure, which has previously been shown to also affect actin assembly,34 was again used to determine the effect of ErbB3 knock-down on actin assembly. After 15 min on ice, the amount of polymerized actin was decreased in all groups (Figure 5(b)). Upon re-incubation at 37 °C for 15 min, the amount of un-polymerized cytoskeletal actin was significantly higher in ErbB3-silenced cells (74% increase, p < 0.01; Figure 5(f)). Taken together, these results support a role of ErbB3 in the cytoskeletal organization.

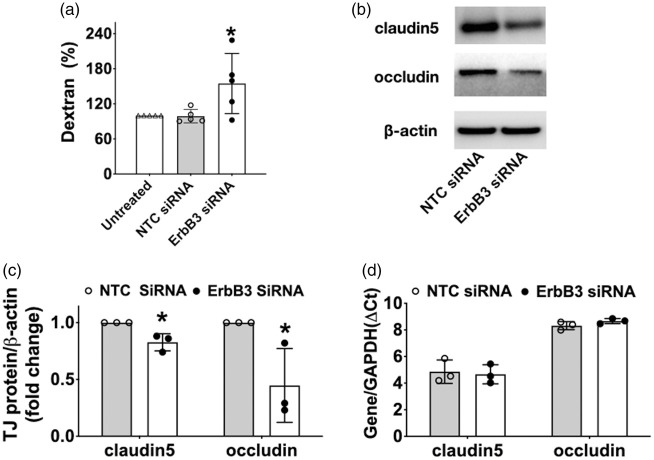

Reduction of ErbB3 gene expression affects endothelial permeability and tight junction levels

In order to evaluate whether expression status of ErbB3 affects barrier function, trans-well permeability assays were performed, showing a 54% increase (p < 0.05) in Dextran-40 kDa extravasation (Figure 6(a)) in ErbB3-silenced cells compared to cells treated with non-targeting siRNA (which are not different . This result prompted an inquiry into the expression of tight junction proteins, which is highly associated with barrier integrity. At 48 hr after transfection, protein expressions of claudin-5 and occludin were decreased in ErbB3 siRNA-transfected cells by 17% and 55%, respectively (p < 0.05 for both; Figure 6(b) and (c)). There was no difference in the mRNA level of claudin-5 and occludin in ErbB3-silenced cells. (Figure 6(d)). Collectively, these data suggest that ErbB3 plays a critical role in the regulation of endothelial permeability, associated with its effects on claudin-5 and occludin at a post-translational level.

Figure 6.

Effect of ErbB3 silencing on endothelial permeability and on tight junction proteins. (a) Dextran-40kD extravasation was increased in a transwell system with ErbB3-silenced cells, compared to untreated cells and to control cells (*p < 0.05, n=6, duplicates). (b) Representative image and (c) quantification of claudin-5 and occludin protein at 48 hr after transfection. Both claudin-5 and occludin levels were decreased in ErbB3-siRNA transfected cells compared to control cells (*p < 0.05, n=3). (d) mRNA level of claudin5 and occludin did not differ between ErbB3-siRNA vs control cells (p = ns, n=3, triplicates).

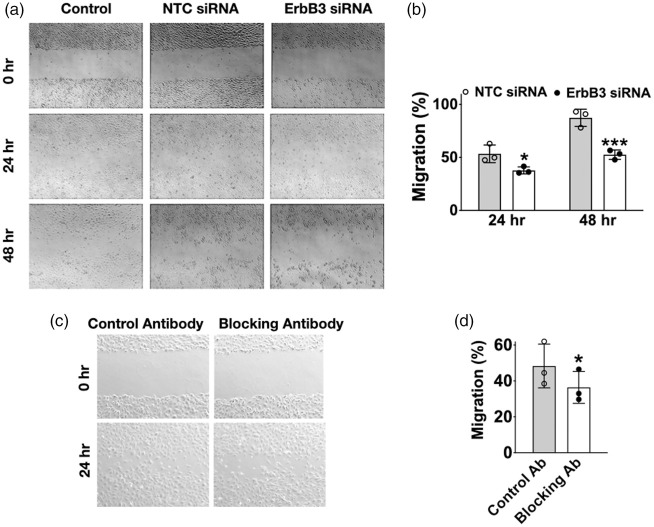

Reduction of ErbB3 gene expression is associated with decreased cell migration

Since microtubule assembly and re-assembly are essential steps in cell migration, we investigated whether ErbB3-silencing affects this process. In a scratch migration assay, cell migration was decreased by 16% (p < 0.05) at 24 hr and 35% (p < 0.01) at 48 hr in ErbB3 siRNA-treated cells compared to control cells (Figure 7(a) and (b)). The migration assay was repeated using normal cells without ErbB3-siRNA transfection, but with the addition of an ErbB3-blocking antibody to the cell culture media during the migration assay. Controls consisted of normal cells with the addition of a non-specific antibody (normal rabbit IgG) during the assay. Similar to the previous result, cell migration was decreased by 12% (p < 0.05) at 24 hr in the presence of an ErbB3-blocking antibody (Figure 7(c) and (d)). Since cell migration requires disassembly and re-assembly of parts of the cytoskeleton, these results serve as another example of ErbB3’s role in a cytoskeleton -associated endothelial functions.

Figure 7.

Effect of ErbB3 silencing on cell migration. (a) Representative images and (b) quantification of scratch migration assay after transfection. ErbB3 siRNA transfected cells showed increased gap area due to delayed endothelial migration at 24 hr and 48 hr after transfection (*p < 0.05 at 24 hr; **p <0.01 at 48 hr; n=3, triplicates) (c) Representative picture and (d) quantification of scratch migration assay with blocking antibodies. Non-tranafected cells that were incubated with an ErbB3 blocking antibody showed delayed migration compared to cells incubated with a control antibody (*p < 0.05; n=3, triplicates).

Discussion

The results presented here add to the growing evidence that NRG1 signaling is widely present in endothelial cells – in arteries, veins, and capillaries,27 in the fetal umbilical vein,14 as well as in the microvascular endothelial cells of the heart.35,36 In the brain, NRG1-β improves endothelial survival after oxygen-glucose deprivation, protects tight junction proteins and endothelial barrier function during heme-induced injury,1 and decreases IL-1β induced endothelial hyper-permeability.14 The current investigation is focused on the effects of ErbB3 down-regulation, to elucidate the role of ErbB3 function in BMECs.

The finding that erbB3-silenced cells exhibit a decrease in NRG1-stimulated phosphorylation of Akt and S6 kinase correspond to known NRG1 signaling pathways. In this study, cell survival in culture media and in angiogenic assay was not affected by erbB3 knock down at 24 hr, but was decreased at later time points. This finding is consistent with the roles that Akt and S6 kinase play in growth, metabolism, and survival. The lack of an effect 24 hr may reflect an involvement of NRG1/ErbB3 during later timepoints; alternatively, it is possible that the cell media, which is supplemented with a large number of growth factors, including EGF, renders the cells less dependent on NRG1/ErbB3 signaling pathways at early time points. Of note, Akt and S6 kinase also affect downstream events that are related to cytosketal processes. Certainly, the changes detected in baseline levels of MLC phosphorylation in ErbB3-silenced cells suggest that future investigations into the relationship between ErbB3 and cytoskeletal pathways will be useful.

ErbB3 gene silencing in BMECs is associated with alterations in the organization of microtubules and actin, two of the three main components of the cell cytoskeleton. Additional features observed include increased permeability, decreased cell migration, a shorter duration of cell viability and of stability of tube structures formed in an angiogenesis assay. These activities are all intricately connected to cytoskeletal pathways, and the involvement of ErbB3 in cytoskeletal mechanics suggests that its actions are extensive, as the cytoskeleton is a structure which is crucial in the spatial organization of the cell, the homeostasis between the external and internal environments, and the mechanics of cellular movement.

Structurally, the cytoskeleton is composed of a complex network of protein filaments which spans the entire cell. In eukaryotes, it is composed of microfilaments (also called actin filaments), intermediate filaments, and microtubules. Microfilaments combine into polymers and eventually form actin filaments, which intertwine to become f-actin, a structure which can generate contractile forces for cellular processes. Intermediate filaments provide mechanical support to the cytoskeleton.37 Microtubules are hollow tubes made of a large number of protofilaments, which are in turn composed of polypeptide subunits made of α-tubulin/β-tubulin heterodimers.38 Together, these cytoskeletal filaments enable the cell to perform many of its essential functions, including cell migration, endocytosis, phagocytosis, intracellular transport, and cell division.39,40 Cytoskeleton dysfunction is implicated in a number of neurological diseases, such as Parkinson's disease, Alzheimer's disease, Huntington's disease, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS).41 In Alzheimer's disease, dysfunction of tau proteins, which normally stabilize microtubules, leads to microtubule disassembly, and tau proteins accumulate as neurofibrillary tangles, the familiar hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease.42,43 From a broader perspective, NRG1’s involvement in endothelial cytoskeletal functions is reminiscent of its known actions involving actin and microtubule processes in diverse types of cells – synaptic plasticity of neurons,44 contractility of cardiomyocytes,45 as well as invasion of cancer cells.46,47

The involvement of ErbB3 in actin and microtubule assembly provides one mechanism for the decrease in cell migration seen in ErbB3-silenced cells, since cell movement and migration require the formation and retraction of lamellopdia and filopodia, activities made possible by the dis-assembly and re-assembly of cytoskeletal filaments.48 Likewise, angiogenesis, an event that enables increased blood flow after brain ischemia,49 is also dependent on cytoskeletal dynamics.50,51 In our study using a matrigel assay of angiogenesis, the number of tubes formed in ErbB3-silenced cells was not different from that in control cells at 24 hr, but was reduced at 48 hr. This finding suggest that the stability of formed structures is affected by decreased ErbB3 signaling, although it is not clear whether this is mediated by a general negative effect on cell function or a specific effect on angiogenesis. The increase in permeability seen in monolayers of ErbB3-silenced cells is likely associated with cytoskeletal perturbations as well, since aberrations in cytoskeletal activities are associated with loss of endothelial barrier integrity,52,53 with a direct impact on BBB function. Brain microvascular endothelial cells are the major functional constituents of the BBB and differ from peripheral endothelial cells by the lack of fenestration and presence of excessive lateral contacts (tight junctions) between adjacent cells.20,54,55 Tight junctions consist of3 tetraspan transmembrane proteins such as occludin and those belonging to the claudin family.19,56 Among the ubiquitous family of claudins, claudin 5 is highly enriched at the BBB, and along with occludin, contributes significantly to the maintenance of BBB function. Thus the BBB is essential for restricting paracellular transport of molecules from the bloodstream into the brain parenchyma.18 In this regard, our data shows that decreased ErbB3 expression was associated with a lower amount of claudin-5 and occludin, along with altered f-actin organization, in brain microvascular endothelial cells. This finding is consistent with previous findings that alterations in actin organization are seen in states of increased endothelial permeability.14 The decreased amounts of claudin-5 and occludin are likely part of this framework in which tight junction proteins are destabilized in the setting of endothelial barrier dysfunction. Indeed, BBB damage has been associated with a change in occludin localization and structure.57 On the other hand, an improvement in endothelial barrier function due to decreased turn-over of claudin-5 and occludin has been previously described.58

This study is limited by the fact that we were not able to detect the 185kD ErbB3 protein by immunoblotting or by immunocytochemistry, although a significant difference was detected in ErbB3 mRNA levels. In comparing our methods with published studies, it is noteworthy that many studies that have examined ErbB receptor activation by NRG1 have been performed in transformed cells, which typically express ErbB receptors at higher levels than primary cells.59 Our mRNA analysis shows that ErbB3 is expressed at low levels in the primary microvascular endothelial cells of adult origin. Despite low expression levels, changes in ErbB3 activation are associated with biologically significant functional outcomes. Another shortcoming is that we have only examined secreted levels of NRG1 and have not examined levels of the other neuregulins, which have been begun to be characterized only recently. Hopefully this data will be followed by similar explorations of ErbB receptors with other neuregulins. This study is also limited by the fact that other types of cells, such as astrocytes and pericytes, which normally interact with endothelial cells, are not included in our in-vitro experiment. Using endothelial cells alone does not permit the study of the physiological conditions that occur in the brain; further in-vivo studies would be needed to clarify the complex interactions between different types of cells as well as between the endothelial cells and the extracellular matrix.

In summary, the findings presented here suggest that NRG1/ErbB3 signaling is integral to the cytoskeleton function of brain microvascular endothelial cells, and cytoskeleton-associated processes, including cell morphology, angiogenesis, migration, and permeability. Additional investigations will be needed to further define NRG1/ErbB3 signaling at baseline and after injury, as well as the role of the other NRG1 receptors in mediating NRG1 effect in BMECs. These studies will provide helpful insights into NRG1’s role in the stable functioning of the brain microvasculature and the blood-brain barrier.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-jcb-10.1177_0271678X20984976 for ErbB3 is a critical regulator of cytoskeletal dynamics in brain microvascular endothelial cells: Implications for vascular remodeling and blood brain barrier modulation by Limin Wu, Mohammad R Islam, Janice Lee, Hajime Takase, Shuzhen Guo, Allison M Andrews, Tetyana P Buzhdygan, Justin Mathew, Wenlu Li, Ken Arai, Eng H Lo, Servio H Ramirez and Josephine Lok in Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the imaging expertise provided by Dr. Thomas Diefenbach at the Imaging Core at the Ragon Imaging Center, Ragon Institute (Cambridge, MA), the technical assistance of Ms. Estefania Reyes-Bricio, and helpful discussions with Dr. Liakhot Khan and Dr. Verena Gobel at the Mucosal Immunology and Biology Research Laboratory, Massachusetts General Hospital (Boston, MA).

Footnotes

Authors’ contributions: LW and J.Lok designed, analyzed and interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript. LW, MI, J.Lee, HT, SG, AA performed the experiments and analyzed data. WL provided cell culture expertise. JM assisted with microscopy. SHR, KA, EL, TBP assisted in revising the manuscript.

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The work is funded by the NIH/NINDS R01NS091573 (to JL), The Shriners Hospital for Children award# 85180-PHL-20 (SHR), NIH/NIDA T32DA007237 (to TPB), NIH/NIDA DA046308 (to AMA).

ORCID iD: Josephine Lok https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8320-0961

Supplementary material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Kao WT, Wang Y, Kleinman JE, et al. Common genetic variation in neuregulin 3 (NRG3) influences risk for schizophrenia and impacts NRG3 expression in human brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010; 107: 15619–15624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mei L, Xiong WC.Neuregulin 1 in neural development, synaptic plasticity and schizophrenia. Nat Rev Neurosci 2008; 9: 437–452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peles E, Yarden Y.Neu and its ligands: from an oncogene to neural factors. Bioessays 1993; 15: 815–824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Falls DL.Neuregulins: functions, forms, and signaling strategies. Exp Cell Res 2003; 284: 14–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holmes WE, Sliwkowski MX, Akita RW, et al. Identification of heregulin, a specific activator of p185erbB2. Science 1992; 256: 1205–1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jessell TM, Siegel RE, Fischbach GD.Induction of acetylcholine receptors on cultured skeletal muscle by a factor extracted from brain and spinal cord. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1979; 76: 5397–5401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Falls DL, Rosen KM, Corfas G, et al. ARIA, a protein that stimulates acetylcholine receptor synthesis, is a member of the neu ligand family. Cell 1993; 72: 801–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raff MC, Abney E, Brockes JP, et al. Schwann cell growth factors. Cell 1978; 15: 813–822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meyer D, Yamaai T, Garratt A, et al. Isoform-specific expression and function of neuregulin. Development 1997; 124: 3575–3586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Skirzewski M, Karavanova I, Shamir A, et al. ErbB4 signaling in dopaminergic axonal projections increases extracellular dopamine levels and regulates spatial/working memory behaviors. Mol Psychiatry 2018; 23: 2227–2237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fazzari P, Paternain AV, Valiente M, et al. Control of cortical GABA circuitry development by Nrg1 and ErbB4 signalling. Nature 2010; 464: 1376–1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pinkas-Kramarski R, Eilam R, Alroy I, et al. Differential expression of NDF/neuregulin receptors ErbB-3 and ErbB-4 and involvement in inhibition of neuronal differentiation. Oncogene 1997; 15: 2803–2815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gauthier MK, Kosciuczyk K, Tapley L, et al. Dysregulation of the neuregulin-1-ErbB network modulates endogenous oligodendrocyte differentiation and preservation after spinal cord injury. Eur J Neurosci 2013; 38: 2693–2715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu L, Ramirez SH, Andrews AM, et al. Neuregulin1-beta decreases interleukin-1beta-induced RhoA activation, myosin light chain phosphorylation, and endothelial hyperpermeability. J Neurochem 2016; 136: 250–257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iivanainen E, Paatero I, Heikkinen SM, et al. Intra- and extracellular signaling by endothelial neuregulin-1. Exp Cell Res 2007; 313: 2896–2909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lok J, Wang H, Murata Y, et al. Effect of neuregulin-1 on histopathological and functional outcome after controlled cortical impact in mice. J Neurotrauma 2007; 24: 1817–1822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lok J, Zhao S, Leung W, et al. Neuregulin-1 effects on endothelial and blood brain barrier permeability after experimental injury. Transl Stroke Res 2012; 3 Suppl 1: S119–S124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ballabh P, Braun A, Nedergaard M.The blood-brain barrier: an overview: structure, regulation, and clinical implications. Neurobiol Dis 2004; 16: 1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lochhead JJ, Ronaldson PT, Davis TP.Hypoxic stress and inflammatory pain disrupt blood-brain barrier tight junctions: implications for drug delivery to the Central nervous system. AAPS J 2017; 19: 910–920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abbott NJ, Friedman A.Overview and introduction: the blood-brain barrier in health and disease. Epilepsia 2012; 53: 1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tzahar E, Waterman H, Chen X, et al. A hierarchical network of interreceptor interactions determines signal transduction by neu differentiation factor/neuregulin and epidermal growth factor. Mol Cell Biol 1996; 16: 5276–5287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bernas MJ, Cardoso FL, Daley SK, et al. Establishment of primary cultures of human brain microvascular endothelial cells to provide an in vitro cellular model of the blood-brain barrier. Nat Protoc 2010; 5: 1265–1272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chung JY, Krapp N, Wu L, et al. Interleukin-1 receptor 1 deletion in focal and diffuse experimental traumatic brain injury in mice. J Neurotrauma 2019; 36: 370–379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Crouch EE, Liu C, Silva-Vargas V, et al. Regional and stage-specific effects of prospectively purified vascular cells on the adult V-SVZ neural stem cell lineage. J Neurosci 2015; 35: 4528–4539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stevens TC, Ochoa CD, Morrow KA, et al. The Pseudomonas aeruginosa exoenzyme Y impairs endothelial cell proliferation and vascular repair following lung injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2014; 306: L915–L924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hedhli N, Kalinowski A, K SR.Cardiovascular effects of neuregulin-1/ErbB signaling: role in vascular signaling and angiogenesis. Curr Pharm Des 2014; 20: 4899–4905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hedhli N, Dobrucki LW, Kalinowski A, et al. Endothelial-derived neuregulin is an important mediator of ischaemia-induced angiogenesis and arteriogenesis. Cardiovasc Res 2012; 93: 516–524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu L, Walas S, Leung W, et al. Neuregulin1-beta decreases IL-1beta-induced neutrophil adhesion to human brain microvascular endothelial cells. Transl Stroke Res 2015; 6: 116–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sithanandam G, Anderson LM.The ERBB3 receptor in cancer and cancer gene therapy. Cancer Gene Ther 2008; 15: 413–448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gaborit N, Lindzen M, Yarden Y.Emerging anti-cancer antibodies and combination therapies targeting HER3/ERBB3. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2016; 12: 576–592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kiavue N, Cabel L, Melaabi S, et al. ERBB3 mutations in cancer: biological aspects, prevalence and therapeutics. Oncogene 2020; 39: 487–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Anjum R, Blenis J.The RSK family of kinases: emerging roles in cellular signalling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2008; 9: 747–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ochoa CD, Stevens T, Balczon R.Cold exposure reveals two populations of microtubules in pulmonary endothelia. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2011; 300: L132–L138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Upadhya GA, Strasberg SM.Evidence that actin disassembly is a requirement for matrix metalloproteinase secretion by sinusoidal endothelial cells during cold preservation in the rat. Hepatology 1999; 30: 169–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kalinowski A, Plowes NJ, Huang Q, et al. Metalloproteinase-dependent cleavage of neuregulin and autocrine stimulation of vascular endothelial cells. FASEB J 2010; 24: 2567–2575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ky B, Kimmel SE, Safa RN, et al. Neuregulin-1 beta is associated with disease severity and adverse outcomes in chronic heart failure. Circulation 2009; 120: 310–317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Herrmann H, Strelkov SV, Burkhard P, et al. Intermediate filaments: primary determinants of cell architecture and plasticity. J Clin Invest 2009; 119: 1772–1783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Beese L, Stubbs G, Cohen C.Microtubule structure at 18 a resolution. J Mol Biol 1987; 194: 257–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fletcher DA, Mullins RD.Cell mechanics and the cytoskeleton. Nature 2010; 463: 485–492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Geli MI, Riezman H.Endocytic internalization in yeast and animal cells: similar and different. J Cell Sci 1998; 111: 1031–1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pelucchi S, Stringhi R, Marcello E.Dendritic spines in Alzheimer’s disease: how the actin cytoskeleton contributes to synaptic failure. Int J Mol Sci 2020; 21: 908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bamburg JR, Bloom GS.Cytoskeletal pathologies of Alzheimer disease. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton 2009; 66: 635–649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Medeiros R, Baglietto-Vargas D, LaFerla FM.The role of tau in Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders. CNS Neurosci Ther 2011; 17: 514–524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Grieco SF, Holmes TC, Xu X.Neuregulin directed molecular mechanisms of visual cortical plasticity. J Comp Neurol 2019; 527: 668–678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pentassuglia L, Sawyer DB.ErbB/integrin signaling interactions in regulation of myocardial cell-cell and cell-matrix interactions. Biochim Biophys Acta 2013; 1833: 909–916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Doppler H, Bastea LI, Eiseler T, et al. Neuregulin mediates F-actin-driven cell migration through inhibition of protein kinase D1 via Rac1 protein. J Biol Chem 2013; 288: 455–465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Meira M, Masson R, Stagljar I, et al. Memo is a cofilin-interacting protein that influences PLCgamma1 and cofilin activities, and is essential for maintaining directionality during ErbB2-induced tumor-cell migration. J Cell Sci 2009; 122: 787–797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mattila PK, Lappalainen P.Filopodia: molecular architecture and cellular functions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2008; 9: 446–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liu J, Wang Y, Akamatsu Y, et al. Vascular remodeling after ischemic stroke: mechanisms and therapeutic potentials. Prog Neurobiol 2014; 115: 138–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Joshi D, Inamdar MS.Rudhira/BCAS3 couples microtubules and intermediate filaments to promote cell migration for angiogenic remodeling. Mol Biol Cell 2019; 30: 1437–1450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bayless KJ, Johnson GA.Role of the cytoskeleton in formation and maintenance of angiogenic sprouts. J Vasc Res 2011; 48: 369–385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Goddard LM, Iruela-Arispe ML.Cellular and molecular regulation of vascular permeability. Thromb Haemost 2013; 109: 407–415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Garcia-Ponce A, Citalan-Madrid AF, Velazquez-Avila M, et al. The role of actin-binding proteins in the control of endothelial barrier integrity. Thromb Haemost 113: 20–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Banks WA.The blood-brain barrier in neuroimmunology: tales of separation and assimilation. Brain Behav Immun 2015; 44: 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zihni C, Mills C, Matter K, et al. Tight junctions: from simple barriers to multifunctional molecular gates. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2016; 17: 564–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Balda MS, Matter K.Transmembrane proteins of tight junctions. Semin Cell Dev Biol 2000; 11: 281–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lochhead JJ, McCaffrey G, Quigley CE, et al. Oxidative stress increases blood-brain barrier permeability and induces alterations in occludin during hypoxia-reoxygenation. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2010; 30: 1625–1636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ramirez SH, Fan S, Dykstra H, et al. Inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase 3beta promotes tight junction stability in brain endothelial cells by half-life extension of occludin and claudin-5. PLoS One 2013; 8: e55972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Black LE, Longo JF, Carroll SL.Mechanisms of receptor tyrosine-protein kinase ErbB-3 (ERBB3) action in human neoplasia. Am J Pathol 2019; 189: 1898–1912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-jcb-10.1177_0271678X20984976 for ErbB3 is a critical regulator of cytoskeletal dynamics in brain microvascular endothelial cells: Implications for vascular remodeling and blood brain barrier modulation by Limin Wu, Mohammad R Islam, Janice Lee, Hajime Takase, Shuzhen Guo, Allison M Andrews, Tetyana P Buzhdygan, Justin Mathew, Wenlu Li, Ken Arai, Eng H Lo, Servio H Ramirez and Josephine Lok in Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism