Abstract

Characterizing the effect of limited oxygen availability on brain metabolism during brain activation is an essential step towards a better understanding of brain homeostasis and has obvious clinical implications. However, how the cerebral oxygen extraction fraction (OEF) depends on oxygen availability during brain activation remains unclear, which is mostly attributable to the scarcity and safety of measurement techniques. Recently, a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) method that enables noninvasive and dynamic measurement of the OEF has been developed and confirmed to be applicable to functional MRI studies. Using this novel method, the present study investigated the motor-evoked OEF response in both normoxia (21% O2) and hypoxia (12% O2). Our results showed that OEF activation decreased in the brain areas involved in motor task execution. Decreases in the motor-evoked OEF response were greater under hypoxia (−21.7% ± 5.5%) than under normoxia (−11.8% ± 3.7%) and showed a substantial decrease as a function of arterial oxygen saturation. These findings suggest a different relationship between oxygen delivery and consumption during hypoxia compared to normoxia. This methodology may provide a new perspective on the effects of mild hypoxia on brain function.

Keywords: Oxygen extraction fraction, hypoxia, motor function, venous blood volume fraction, functional magnetic resonance imaging

Introduction

The cerebral oxygen extraction fraction (OEF) reflects the balance between oxygen delivery and tissue oxygen consumption and represents the proportion of oxygen extracted by the tissue as blood passes through the capillaries.1 Importantly, precisely evaluating the OEF is indispensable for furthering the neurophysiological interpretation of blood oxygen level-dependent (BOLD) signals.

In concrete terms, the OEF can reflect underlying changes in cerebral oxygen metabolism. Taking the decrease in cerebral blood flow (CBF) caused by carotid or middle cerebral artery occlusion as an example, the OEF will correspondingly increase to maintain tissue oxygen metabolism or the cerebral metabolic rate of oxygen (CMRO2), and normal neuronal function cannot be preserved as the OEF reaches the maximum.2–5 Prior literature suggests that the OEF is decreased to preserve tissue oxygen partial pressure during neural activation, which helps clarify a physiological phenomenon in which the CBF increases considerably more than the CMRO2.6,7 Thus, the OEF represents a balance between the CMRO2 and CBF. A reduction in the OEF has been firmly established to result in locally decreased deoxyhemoglobin concentrations, which enables BOLD functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to reveal brain activity.8,9 Furthermore, the BOLD contrast mechanisms also depend on cerebral blood volume (CBV). The relative focal changes in the OEF during activation contribute to the BOLD effect, and changes in the baseline OEF will influence the size of the BOLD effect.10–12 Therefore, characterizing the OEF is essential for understanding the physiological mechanisms of brain activity and has important clinical implications.

Previous studies have reported that the relationship between oxygen delivery and oxygen metabolism is influenced by different oxygenation states. Here, this study set out to address this issue with a focus on characterizing the OEF in hypoxia, which remains largely unclear. The human brain is the most hypoxia-sensitive organ in the body because oxidative metabolism is the primary source of energy required for brain activity.13 The most prominent physiological response to hypoxia is a global increase in CBF,14–16 whereas stimulation-induced regional CBF responses are not affected by hypoxia during increased neuronal activity.14,17–20 The amplitude of stimulus-induced BOLD responses decreases significantly during mild hypoxia compared with normoxia,17,20–23 while vascular responses to brain activation do not change during hypoxia.17,19–21,24 Based on an extended calibrated BOLD method, recent research has demonstrated that hypoxia with 12% O2 significantly decreased the amplitude of CMRO2 responses,21 indicating that the oxygen metabolism response may change when the brain is exposed to transient hypoxia. Taken together, we hypothesize that OEF responses to neural stimulation will change in hypoxia relative to normoxia according to Fick’s principle.25

However, existing OEF techniques using blood-T2-based15,26 or susceptometry-based27 MRI cannot show potential regional heterogeneity during hypoxia, and only the global OEF can be obtained. This dilemma is largely due to the limited rapidity and availability of suitable techniques for OEF measurement. On the basis of the relationship between MR signals and tissue oxygenation in the presence of blood vessel networks,28 we have developed an MR-based method, the multiecho asymmetric spin echo (MASE), for dynamic measurement of the OEF29 during fMRI studies. The MASE boasts high spatiotemporal resolution for OEF measurements and has been demonstrated to be feasible in functional localization29 and brain network30 studies. Using this novel method, the present study endeavored to characterize OEF changes as participants performed motor tasks under both hypoxia (12% O2) and normoxia (21% O2). The results were compared between different gas conditions and correlated with blood oxygen saturation levels in the same subjects.

Materials and methods

Participants

Twenty-one subjects (13 males; average age (mean ± SD) = 24.33 ± 2.99 years) without a history of neurological and respiratory abnormalities were recruited. Accordant to the Helsinki Declaration of 1975 (and as revised in 1983), the study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Peking University. Written informed consent was obtained from each subject. Scanning was performed in the Center for MRI Research at Peking University on a GE Discovery MR750 3T MR whole body scanner with an eight-channel head coil receiver system (GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA).

Experimental design

All subjects were instructed to perform a motor task in two different oxygen states, namely hypoxia (12% oxygen balanced with nitrogen) and normoxia (21% oxygen balanced with nitrogen). Gases were supplied at a flow rate of 15 L/min through a non-rebreathing face mask, and arterial oxygen saturation (SaO2) was monitored from the left index finger with a digital pulse oximeter (Model 7500FO, Nonin, Plymouth, USA) during scanning. The scanning order of normoxia and hypoxia was constant (normoxia followed by hypoxia). Approximately 5∼7 minutes of adaptation to each gas was required before a stable SaO2 was achieved.20,21

The motor task was conducted using a block-design paradigm wherein a 12-second dummy scan preceded five blocks (each lasted 60 seconds) alternating between task and resting states, and the whole scan took 312 seconds in total. For the motor task, the subjects performed grasp-release right-hand movements at a picture-guided frequency of 1 Hz. During the resting state, the subjects were instructed to focus on a fixation point on a black screen.

MRI scanning protocol

Before fMRI data collection, high-order shimming (five 2nd-order shim terms: XY, ZX, ZY, Z2, and X2–Y2) provided by the scanner vendor was used to reduce magnetic field inhomogeneity. The motor cortex was covered by sixteen interleaved transverse 6-mm slices. The OEF-fMRI images were acquired with a MASE pulse sequence29 (field of view: 260 mm × 260 mm; matrix size: 64 × 64; repetition time (TR): 3 s; six different echo times (TEs): 65, 100, 135, 147.4, 159.8 and 172.2 ms; sensitivity-encoding factor: 2). Anatomical images were acquired using a 3D FSPGR sequence (TR/TE/θ = 6.6 ms/2.9 ms/12°, 192 sagittal slices, and voxel size = 1 × 1 × 1 mm3).

Data preprocessing and analysis

Data preprocessing was conducted with SPM12 software and further analyses based on the preprocessed data employed codes written in MATLAB (MathWorks, Inc., Natick, MA, USA). For each subject, the data acquired in the first 12 seconds (24 volumes) were discarded to ensure that the signal had reached a steady state. Motion correction parameters were estimated for each time point by aligning the first echo images to the corresponding first time point image. Then, the motion correction parameters were applied to the subsequent echoes. Motion-corrected OEF-fMRI images were coregistered to the anatomical image and normalized to the Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) standard brain space. The normalized images were smoothed using a Gaussian kernel with full-width at half-maximum of 8 mm.

For each time point, the six echo data were analyzed by following procedures: (1) one pair of gradient echo images acquired symmetrically about the spin echo were used to estimate the effect of R2 according to a mono-exponential decay model; (2) R2* and the signal intensity of the spin echo (S(TESE)) were computed using linear least-squares curve-fitting with the last four gradient echo images; (3) both R2* and R2 were used to calculate R2′ (R2′ = R2*–R2); (4) combined with the actual acquired spin echo signal (S0(TESE)) from the second echo train, the venous blood volume fraction (fCBV) was obtained by the difference between the logarithm of S(TESE) and S0(TESE); and (5) based on the Yablonskiy and Haacke model,28 the relationship between R2′ and the fraction of oxygenated blood is described as follows:

| (1) |

where the gyromagnetic ratio is 2.675108 s−1T−1; is the susceptibility difference between fully oxygenated and fully deoxygenated hemoglobin (= 0.264 ppm);31 Hct is the local hematocrit (= 0.35);32 and is the main magnetic field (= 3 T).

The is estimated using a weighted average of arterial, capillary and venous compartments. Given the lack of technology and methods for directly measuring the contribution of respective vascular components, Griffeth et al. simplified the model by assuming that the capillary volume fraction is 0.4 and capillary oxygenation fraction is determined by a weighted between arterial and venous oxygenation fraction:10

| (2) |

where , is the arterial volume fraction (= 0.2)10, and and are the arterial and venous oxygenation fractions, respectively. Studies have shown that changes during hypoxia,33 and still available data for the is very limited, especially in normal adults under hypoxia condition. Based on a newborn lamb study,33 Wong et al. found that the increased by 0.11 when the arterial partial pressure for oxygen decreased from 100 mmHg to 60 mmHg. The was derived as follows:34

| (3) |

The OEF can be obtained by substituting equations (2) and (3) into equation (1). The BOLD response to the motor task during normoxia and hypoxia was investigated using the first echo (T2*-weighted signal) of the MASE pulse sequence.

Statistical analysis

For each gas condition, the OEF data were modeled voxel-wise using a general linear model in SPM12. This model was generated by a convolution of the stimulus pattern with a standard canonical hemodynamic response function. Z-score maps were calculated using the fMRI time series for each voxel with a voxel-level threshold of P < 0.001 and cluster-level family-wise error (FWE) correction of P < 0.05.

The region of interest (ROI) in the primary motor cortex was defined as the overlapping and threshold voxels of the OEF under both normoxia and hypoxia conditions. For each gas condition, the relative changes in the OEF (δOEF), fCBV (δfCBV) and BOLD (δBOLD) were evaluated in the same manner. Here, δOEF is used as an example for calculation. First, the time course of the OEF in all voxels of the ROI was extracted and averaged. Second, we calculated the mean resting-state data as the baseline value of the OEF (OEFbase), and the first five time points of each resting-state period were excluded considering the transition time of hemodynamic responses.35–37 Specifically, δOEF was calculated as follows:

| (4) |

The activation value of the OEF (OEFactive) was calculated by averaging the task-state data in the same manner as the OEFbase. The mδOEF, the mean magnitude of the δOEF, was computed by averaging the values of δOEF during the task state.

Normality of distribution of the variables was confirmed using a Skewness-Kurtosis normality test. Spearman’s rank correlation analysis was applied to assess significant correlations between the SaO2 and fMRI results (including voxel counts, δOEF, δfCBV). The relationship between the change in SaO2 and the change in OEF values (including OEFbase and OEFactive) was evaluated by Pearson correlation analysis. Paired t-tests were performed for the group comparisons between the normoxia and hypoxia conditions. For all statistical analyses, a two-tailed alpha level of 0.05 was used as the cutoff for significance. Data sets are presented as the mean ± standard deviation.

Results

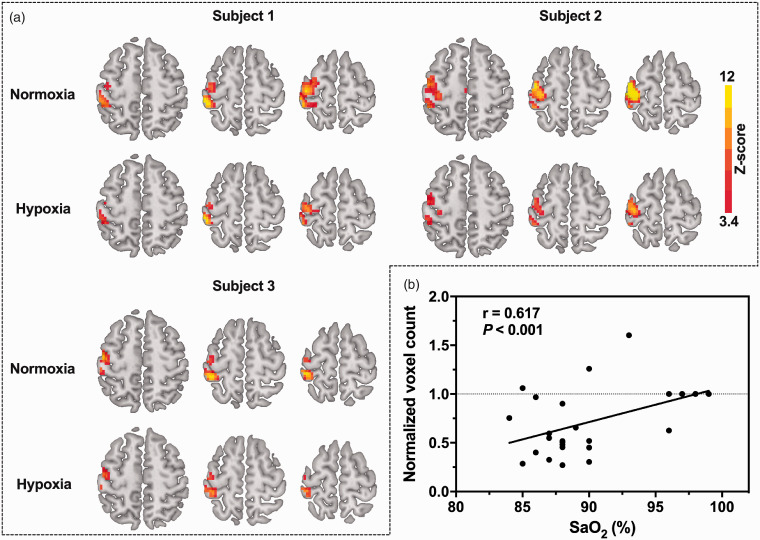

Oxygen saturation significantly decreased by 12% from 97.86% ± 0.85% to 87.24% ± 2.74% (). Typical OEF activation maps obtained from three representative subjects during mild hypoxia and normoxia are shown in Figure 1(a). As expected, brain activation was found in the left motor cortex, including the primary motor cortex, premotor cortex and primary somatosensory cortex. The activation region recruited by the 1-Hz right-hand grasp-release task was smaller during mild hypoxia than during normoxia for 18 of 21 subjects. After excluding three subjects whose voxel counts increased during hypoxia, a reduction of 53.1% ± 19.7% was noted in OEF-activated areas. All subject values were included in the statistical analyses. The results revealed that OEF voxel counts were significantly correlated with SaO2 () (Figure 1(b)). In addition, the OEF maps in the native space of the typical subject during both baseline and activation under normoxia and hypoxia are shown (see Supplementary Figure 1). We also calculated the active voxel counts in native space and compared the results for different gas conditions. We found that the active voxel counts of three subjects increased in native space under hypoxia, and two of them also increased in MNI space. After excluding the three subjects, the OEF-activated areas under hypoxia were 47.4% ± 20.3% smaller than those under normoxia in the native space, which is not significantly different from the result (53.1% ± 19.7%) obtained in the MNI space (P = 0.40).

Figure 1.

(a) OEF activation maps of three typical subjects during a 1-Hz right-hand grasp-release task for each gas condition. The activation region (in color) was generated using a voxel-level threshold of P < 0.001 and cluster-level FWE correction of P < 0.05 superimposed onto the standard template. (b) OEF-activated voxel counts as a function of SaO2. The normalized voxel count values in mild hypoxia are individually normalized to the voxel count in normoxia. Due to overlap, only four data points are presented for normoxia. All subjects (n = 21) were included in the statistical analyses, and a significant correlation (r = 0.617, P < 0.001) in OEF active voxel counts was detected with a changing level of SaO2.

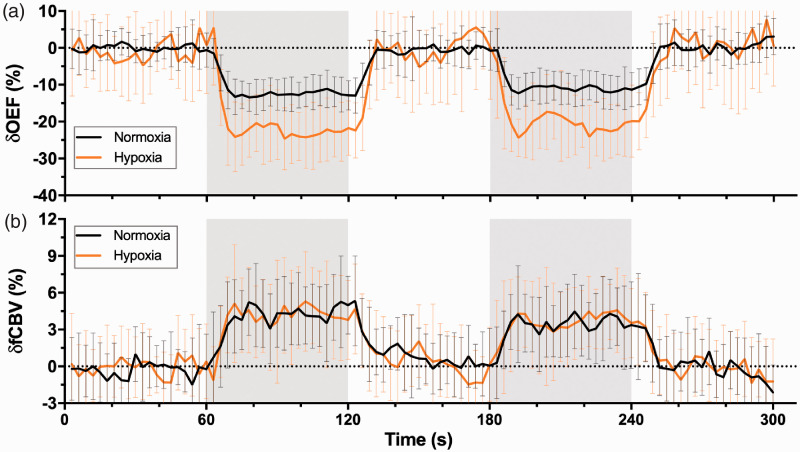

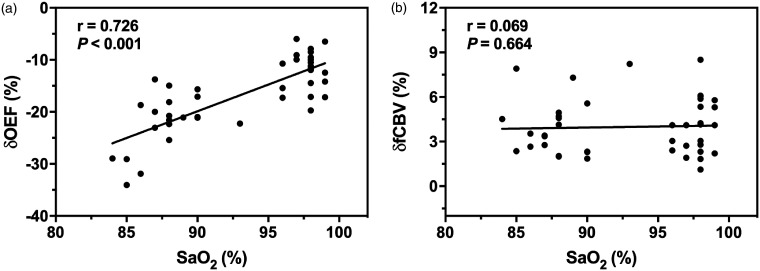

As shown in Figure 2(a), the motor-induced OEF signal amplitude change was larger under mild hypoxia (−21.7% ± 5.5%) than under normoxia (−11.8% ± 3.7%) (). The relationship was further illustrated by a positive correlation of the OEF response amplitude () with a reactivity graph (Figure 3(a)), which shows in detail that the decrease in SaO2 led to a substantial increase in the OEF response amplitude in the motor task, especially when the SaO2 was below 85%. However, the fCBV response (Figure 2(b)) was similar in amplitude between the normoxia (4.0% ± 1.9%) and mild hypoxia (4.0% ± 1.9%) conditions. No discernible trend in the fCBV response was observed at either oxygen saturation () (Figure 3(b)).

Figure 2.

Time courses of OEF (a) and fCBV (b) responses from the overlapping area on OEF between the two gas conditions averaged across all subjects (n = 21). Data are shown as the mean ± SD. The areas in gray represent periods of stimulation.

Figure 3.

OEF (a) and fCBV (b) response amplitudes during motor activation plotted as a function of SaO2.

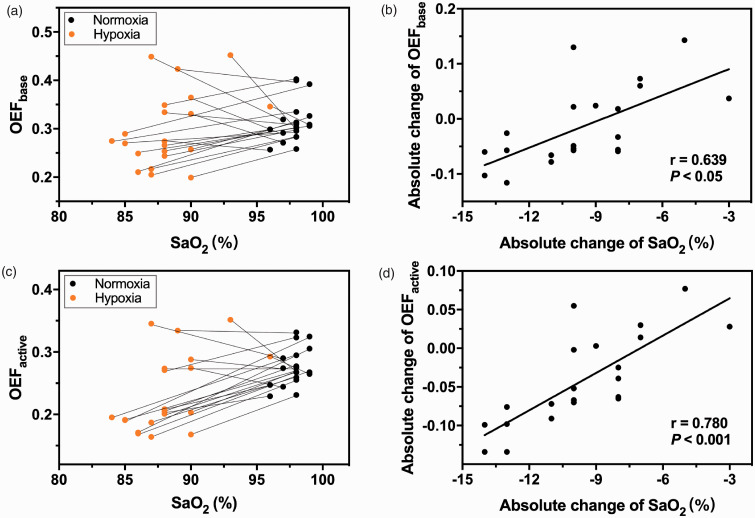

The individual OEF values during baseline (Figure 4(a)) and activation (Figure 4(c)) are shown with the corresponding SaO2. The averaged baseline OEF values were lower under mild hypoxia but displayed no significant difference between mild hypoxia (0.30 ± 0.08) and normoxia (0.31 ± 0.04) (). In contrast, the averaged OEF values during activation were significantly lower under mild hypoxia (0.23 ± 0.06) than under normoxia (0.27 ± 0.03) (). The changes in the OEF during baseline (Figure 4(b)) and activation (Figure 4(d)) were linearly correlated with the changes in SaO2.

Figure 4.

(a) A scatter plot of SaO2 and the OEF baseline values with two data points from individual subjects connected by a line. (b) A scatter plot of the absolute changes in SaO2 and the absolute changes in OEF baseline values. A significant correlation was observed (r = 0.639, P < 0.05). (c) A scatter plot of SaO2 and OEF activation values with two data points from individual subjects connected by a line. (d) A scatter plot of the absolute changes in SaO2 and the absolute changes in OEF activation values. A significant correlation was observed (r = 0.780, P < 0.001).

Discussion

The present study is the first to characterize OEF changes during increased neuronal activity under normoxia and mild hypoxia. Our results demonstrate that (1) the activated area of the OEF response during the motor task was smaller in mild hypoxia than in normoxia and had a significant correlation with SaO2; (2) the amplitude of the task-related OEF signal change obviously increased during hypoxia and was negatively correlated with SaO2; (3) both the baseline and activation OEF values decreased under hypoxia and displayed individual differences; and (4) the absolute changes in SaO2 were significantly correlated with the absolute changes in the baseline and activation OEF values.

The areas of the motor cortex showing task-related OEF responses in normoxia dramatically decreased in mild hypoxia () (Figure 1), and the signal-to-noise (SNR) values of the OEF images were not significantly different between normoxia and mild hypoxia. These results are consistent with those of previous studies investigating the effects of mild hypoxia on fMRI data based on other physiological parameters. Specifically, for BOLD-fMRI, the activation areas were 55% smaller in the visual cortex17 and 45% smaller in the motor cortex18 on average in mild hypoxia than in normoxia. For vascular space occupancy (VASO)-dependent fMRI, the number of significantly activated voxels was 65% smaller in the visual cortex on average under mild hypoxia.17 For arterial spin labeling (ASL) fMRI, the volumes of areas showing CBF increases decreased by approximately 76% in the motor cortex during mild hypoxia.18 Interestingly, with the exception of the significant correlation between (OEF and BOLD) voxel counts and SaO2, no significant correlations were identified between the voxel counts of other physiological parameters (VASO and CBF) and SaO217–19. Although the activation area was smaller under mild hypoxia, the neuronal workload, estimated by visual evoked potentials in the human visual cortex19 and EEG responses in the rat motor cortex, was not significantly different between normoxia and mild hypoxia.22 Moreover, 1H and 31P magnetic resonance spectroscopy studies19,38 have shown that lactate metabolism and energy metabolism during visual stimulation, respectively, were not significantly affected by mild hypoxia.

An increased OEF response amplitude during mild hypoxia was observed in the overlapping activation region between the normoxia and mild hypoxia conditions (Figure 2(a)), representing the first demonstration of the time course of the OEF response for motor tasks in both normoxia and mild hypoxia conditions. When the oxygen concentration dropped to 12%, the OEF response changed from −11.8% 3.7% to −21.7% 5.5% () (Table 1). Compared with a previous study on the grasp-release hand task in normoxia,29 our mδOEF amplitude across all subjects under normoxia was smaller than previously reported amplitudes (−22% ± 4%). This difference may be explained by the different activity types (i.e., bilateral/unilateral grasp-release hand) and different activation regions.39 In addition, the task performance of the subjects also affected the OEF response; thus, a pressure transducer should be added to monitor task performance in future studies. According to Fick’s principle, assuming that the arterial oxygen content is constant during brain activity,35 the OEF response to neural stimulation can be inferred by the values of the CBF and CMRO2 responses. The CMRO2 measurement technique, calibrated BOLD,11,40,41 is further challenged due to complex parameter variations in hypoxia compared to normoxia. Recently, Zhang et al.21 proposed an extended calibrated BOLD model that can measure CMRO2 in hypoxia by simultaneously acquiring VASO, CBF and BOLD signals during hypoxia. Based on the results from Zhang’s study,21 the response amplitudes of the OEF during 1-Hz visual stimulation were -18.3% in normoxia and -21.8% in hypoxia, indicating that the amplitude of the visual-induced OEF signal change was greater during hypoxia. Moreover, the response amplitude of the OEF increased with the decrease in SaO2, especially when the SaO2 dropped to 85% (Figure 3(a)). Many studies have reported that stimulus-evoked CBF responses did not change within the SaO2 range of 80% to 100%.14,17,19,42 Combined with these results, stimulus-evoked CMRO2 responses can be inferred to be related to SaO2. Notably, since this study used 12% O2 gas inhalation conditions, only a few data reflect low oxygen saturation (<85%). Thus, future studies are required to address the sharp increase in OEF response amplitude at low oxygen saturation.

Table 1.

Summary results (mean ± SD, n = 21) of statistical analyses (paired t-test).

| Normoxia | Hypoxia | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SaO2 | 0.98 ± 0.01 | 0.88 ± 0.03 | <0.001 |

| OEFbase | 0.31 ± 0.04 | 0.30 ± 0.08 | 0.359 |

| OEFactive | 0.27 ± 0.03 | 0.23 ± 0.06 | 0.004 |

| mδOEF (%) | –11.8 ± 3.7 | –21.7 ± 5.5 | <0.001 |

| mδfCBV (%) | 4.0 ± 1.9 | 4.0 ± 1.9 | 0.848 |

| mδBOLD (%) | 1.9 ± 0.6 | 1.4 ± 0.4 | <0.001 |

In accordance with studies showing similar characteristics of the CBV response determined by the VASO-fMRI technique,17,20,24 we found no significant difference in the fCBV response to motor tasks between the two oxygenation states (Figure 2(b)), implying that hypoxia had no effect on motor-induced vasoreactivity. Moreover, the fCBV response (Table 1) was not affected by the changes in SaO2 (Figure 3(b)). Notably, the VASO-fMRI technique measures changes in total CBV, while changes in venous CBV affect the BOLD response in normoxia.8,34,43–46 Previous studies have mostly assumed that CBV changes are uniformly distributed across vascular compartments.40 In fact, the changes in venous CBV are smaller than those in arteries and are influenced by the duration of stimulation.47–49 With a short duration of stimulation, fMRI studies showed that venous CBV changes were small or nonexistent due to their slow temporal evolution.46,47 During long stimulation periods, cat studies have shown that the venous CBV eventually reached the same magnitude as the change in arterial CBV. These studies together support that the contribution of venous CBV changes to BOLD signals is significant for long stimulation periods. The stimuli used in this study belong to the long stimulus category with a classical block design and better account for the effects of changes in arterial deoxyhemoglobin volume during mild hypoxia since the fCBV change was the change in the volume of deoxygenated blood rather than in the volume of the vein.46,50 In addition, the cat study showed a decrease in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) volume fraction during visual stimulation,51 suggesting that the contribution of CSF may lead to errors in fCBV evaluation.

In this study, the effects of hypoxia on the OEF both at baseline and during activation were observed. The results showed that both the baseline and activation OEF values were reduced under hypoxia. Specifically, as the SaO2 decreased from 98% to 88%, the baseline and activation OEF values decreased from 0.31 0.04 to 0.27 0.03 and from 0.30 0.08 to 0.23 0.06, respectively (Table 1). A possible explanation may account for the decrease in the baseline OEF during hypoxia. According to Fick’s law of diffusion, oxygen is transported from microvessels with high oxygen concentrations to brain tissue with low oxygen concentrations; then, a reduced SaO2 results in a decrease in the oxygen concentration gradient between capillaries and tissues,52 thereby affecting the diffusion of oxygen from capillaries to tissues.53 In addition, the current study found that the OEF during activation was significantly reduced under hypoxia (Figure 3(c)), which is consistent with the view of Tuunanen et al.19 who quantified the OEF during visual stimulation based on VASO activation volumes and found a reduced OEF as a function of SaO2. In addition, we also found that the change in the OEF was linearly correlated with the change in SaO2 (Figure 4(b) and (d)), which can be used to calculate the OEF under different levels of SaO2 because SaO2 is easy to obtain, especially in clinical studies.

An important factor that affects the absolute OEF estimate is the effective blood oxygenation fraction (Y). In normoxia, Y is mainly considered the contribution of venous vascular components (), provided that the content of deoxyhemoglobin in the arterial blood is negligible. However, since hypoxia results in an increased deoxyhemoglobin concentration in the arterial vasculature, the Y in this study is estimated using a weighted average of arterial, capillary and venous vasculature (). Both the arterioles and capillaries form an important part of cerebral blood volume and the method used in this study has similar sensitivity to the microvascular and venous compartments. We found that the average OEF (0.31 0.04) obtained in this study is higher than that obtained by the model. Although both are based on the model, the average OEF (0.20 0.03) obtained in this study is lower than those values reported in previous studies, including studies using an asymmetric spin echo pulse sequence (ASE-qBOLD)53 and MASE pulse sequence (MASE-qBOLD).29 The low OEF values in this study are primarily caused by differences in the constant terms (, Hct and Ya) in equation (1). With the continuous improvement of measurement technology, the values of these constant terms have been updated. In this study, we used the most updated constant terms ( ppm and Hct = 0.35; Ya is actually measured by a digital pulse oximeter)54 to estimate the group OEF value of 0.20. When we replaced the outdated constant terms ( ppm, Hct = 0.357 and Ya = 1) used in previous studies29,55 with these values, the previous OEF decreased from 0.35 to 0.22. Moreover, the OEF obtained in our present study falls within the range of the OEF (0.17 to 0.23) reported recently using the ASE-based qBOLD method.54,56 Another origin of the low OEF in this study is the overestimation of the fCBV. The fCBV was overestimated mainly because the simple qBOLD model used in this study did not consider the signal contribution of intravascular blood and the additional signal attenuation caused by diffusion.55–57 Recently, Stone et al.58 found that overestimation of the fCBV based on the ASE-qBOLD method was mainly affected by diffusion on extravascular signal decay and less affected by the contribution of intravascular blood signal, which may explain why the fCBV was still overestimated although this study used a long acquisition TE to reduce the contribution of the intravascular blood signal.59,60 Future work should primarily focus on the accurate assessment of the fCBV.

Studies have shown that may change during functional stimulation.47–49,61,62 It is worth noting that stimulus duration may be an important factor affecting change. Kim et al. found that the stimulus-induced total CBV changes were mainly caused by arterial rather than venous blood volume changes, and consequently, increased from 0.27 to 0.34 during a short (15 s) functional stimulation.47 Other studies, however, have found that venous CBV increases during long functional stimulation.48,49,61 The stimuli (60 s) used in this study belong to the long stimulus category, and the typical relative change in total CBV is 8% during the motor task63 and the arterial CBV change is 53% of the total CBV change.10,64 Thus, the motor-induced increased by 0.02 compared with the baseline value. After substituting those values into equation (1), the task-related OEF response changed from −11.8% 3.7% to −8.9% 3.8% in normoxia and from −21.7% 5.5% to −18.7% 5.7% in hypoxia. These results showed that the amplitude of the task-related OEF response decreased as the change in during functional stimulation was taken into consideration, but still the decreases in the task-related OEF response under hypoxia were greater than those under normoxia. Together, our findings suggest that the change in during functional stimulation should be fully considered especially in short stimulus studies.

According to Fick’s principle, the change in OEF is related to the change in CBF, CMRO2 and arterial oxygen content. Previous studies have reported that global CBF increased under hypoxia, but regional CBF showed no significant changes.14,18 Assuming that the regional CMRO2 remains relatively constant under hypoxia, the regional OEF should increase with the decrease in the arterial oxygen content. However, due to the lack of measurement technology, little is known about whether hypoxia alters regional CMRO2. Moreover, experimental evidence suggests that the redistribution of blood low could affect OEF to support the changes in CMRO2, even without a noticeable change in CBF.65–68 Based on the result showing a reduction in the OEF in motor-related areas under hypoxia in this study, we speculate that the CMRO2 in corresponding areas decreases under hypoxia. However, the effect of hypoxia on regional CMRO2 needs to be further investigated using independent quantitative measurement technology. In addition, future studies should pay attention to the influence of the degree of hypoxia on CBF. The reason is that when SaO2 is less than 60%,69–71 a higher baseline CBF may limit further vasodilation induced by task stimulation, and then the same CBF response as in normoxia cannot be evoked.72

Previous studies have found that the BOLD response significantly changes in different physiological states (i.e., hypoxia).17,23,73 In this study, the effect of hypoxia on the BOLD response to a motor task was estimated by the first echo of the MASE pulse sequence. The results showed that the BOLD response was smaller in mild hypoxia (1.4% ± 0.4%) than in normoxia (1.9% ± 0.6%) () (Table 1), which is consistent with previous studies indicating that stimulus-induced BOLD signal amplitudes were significantly reduced during mild hypoxia.17,18,20,22–24,74 The dynamics of the BOLD response are dependent on changes in OEF and CBV, and the amplitude of the response is dependent on baseline physiological states (the baseline OEF and baseline CBV).11,75 Moreover, Toyoda et al.76 found that the contribution of the OEF response to the BOLD response was four- to seven-times greater than the contribution of the CBV response, which is consistent with our results showing a significantly reduced response of the OEF (including baseline and relative changes), an unchanged fCBV response during hypoxia and their relationships with SaO2. Importantly, the BOLD response depending on the change in oxygen saturation, i.e., the change in the deoxyhemoglobin concentration, was also affected by the exponential parameter ,77 which may change under mild hypoxia because of the change in the average vessel size. In a rat study using a modified quantitative BOLD approach, a slightly decreased baseline fCBV was found in the whole brain of rats under mild hypoxia.78 The observed decrease in the baseline fCBV may be due to the effect of the CSF volume contained in voxels, which are reduced during mild hypoxia.79

Notably, all the results obtained in this study were based on the common threshold region of the OEF in both normoxia and hypoxia, enabling direct comparison of OEF signal changes in the same parenchymal structures. However, since the activated OEF region under hypoxia was smaller than that under normoxia, this ROI selection method will be biased towards the smaller region. When the time courses were extracted from all active voxels for each gas condition, the baseline and activation OEF values were significantly increased () under normoxia but were not significantly different under hypoxia compared to those obtained from the overlapping voxels. Nevertheless, the amplitude of the task-related OEF response was also larger under hypoxia (-20.8% ± 5.3%) than under normoxia (-12.3% ± 3.4%) () in the “all active voxels” analysis. Similar to the result for the “overlapping voxels” analysis, no change in the fCBV response to motor tasks was observed between the normoxia (3.7% ± 1.5%) and hypoxia (3.7% ± 1.4%) conditions. These results suggest that absolute OEF estimates should consider the influence of different ROI selection methods.

Measurement of the OEF in this study was mainly based on the relationship between MR signals and blood oxygen saturation established by Yablonskiy and Haacke.80 To meet the time resolution requirement of fMRI research, a simple qBOLD model considering only the contribution of tissues outside blood vessels was used for MASE data. This method has proven feasible in task-based OEF-fMRI29 and resting-state OEF-fMRI,30 and studies have shown that OEF activation areas are mostly located in gray matter, partly eliminating the effect of white matter and CSF signals, which might have overestimated R2′ and fCBV.56,57,81 Another factor resulting in R2′ and fCBV overestimation is the contribution of intravascular signals.54–56 However, studies have shown that the lack of consideration of intravascular signal contribution had little impact on the evaluation of the OEF with undersampling data.54 Moreover, the long TE acquisition setting in this study helped reduce the intravascular signal contribution.59,60 In addition, previous studies82–84 have shown that the inhomogeneity of the magnetic field and the diffusion effect of water in tissue will overestimate R2′; at the same time, because of a 180° refocusing pulse, the signal in the spin echo is not affected by magnetic field variation, which leads to overestimation of the fCBV. Although this experiment adopted the method of a high-order shimming field at the beginning to minimize the influence of magnetic field inhomogeneity, this method is not applicable to all brain areas, and an accurate calculation method is still needed.83,85 Despite these systematic offsets, the OEF assessment between different oxygen states is regulated by physiological changes, which have been demonstrated in pathological conditions using similar methods.86 However, because few studies have investigated the effect of mild hypoxia on the contribution of blood vessel composition, the fCBV results must be interpreted with caution. An alternative and promising method for quantifying changes in fCBV involves measuring CBF with sophisticated measurement techniques and the relationship between CBF and CBV in each vascular component.56,62 Future work is needed to describe whether this association is affected by mild hypoxia. The fixed Hct value of all subjects under different oxygen states may be a factor affecting OEF evaluation. Recently, Broisat et al.87 found that local decreases in Hct in stroke and glioma have spatial heterogeneity; therefore, accurate Hct assessments are necessary, especially for clinical application.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates the OEF response to motor tasks under both mild hypoxia and normoxia for the first time, which primarily benefited from a newly proposed technique, MASE, that can dynamically track the OEF in fMRI research. These findings provide a new perspective on the effects of mild hypoxia on brain function and a possible explanation for the change in BOLD signal during mild hypoxia, which is often difficult but important to determine in altered physiological states, especially in pathological states. The noninvasive and operable properties also reflect the potential for extensive application of these techniques to brain science in the future.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-jcb-10.1177_0271678X21992896 for Effects of mild hypoxia on oxygen extraction fraction responses to brain stimulation by Yayan Yin, Su Shu, Lang Qin, Yi Shan, Jia-Hong Gao and Jie Lu in Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the National Center for Protein Sciences at Peking University for assistance with the MRI data acquisition.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81671662, 81901722, 81790650, 89790651, 81727808 and 31421003); China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2019M650772).

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Authors’ contributions: YY: study design, protocol development, data acquisition, data analysis, interpretation of the results, drafting and revising the article.

SS and LQ: data acquisition, data analysis, interpretation of the results.

YS: data acquisition, interpretation of the results.

JG: study design, study guide, interpretation of the results, revising the article.

JL: study design, study guide, interpretation of the results, revising the article.

Supplementary material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Jiang D, Lin Z, Liu P, et al. Normal variations in brain oxygen extraction fraction are partly attributed to differences in end-tidal CO2. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2020; 40: 1492–1500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Powers WJ.Cerebral oxygen extraction fraction in carotid occlusive disease: measurement and clinical significance. In: Toga WA (Ed.), Brain mapping. Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2015, pp.823–828. [Google Scholar]

- 3.An H, Sen S, Chen Y, et al. Noninvasive measurements of cerebral blood flow, oxygen extraction fraction, and oxygen metabolic index in human with inhalation of air and carbogen using magnetic resonance imaging. Transl Stroke Res 2012; 3: 246–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.An H, Ford AL, Chen Y, et al. Defining the ischemic penumbra using magnetic resonance oxygen metabolic index. Stroke 2015; 46: 982–988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gupta A, Baradaran H, Schweitzer AD, et al. Oxygen extraction fraction and stroke risk in patients with carotid stenosis or occlusion: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ajnr Am J Neuroradiol 2014; 35: 250–255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fox PT, Raichle ME, Mintun MA, et al. Nonoxidative glucose consumption during focal physiologic neural activity. Science 1988; 241: 462–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fox PT, Raichle ME.Focal physiological uncoupling of cerebral blood flow and oxidative metabolism during somatosensory stimulation in human subjects. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1986; 83: 1140–1144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buxton RB.The physics of functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). Rep Prog Phys 2013; 76: 096601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buxton RB, Frank LR.A model for the coupling between cerebral blood flow and oxygen metabolism during neural stimulation. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 1997; 17: 64–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Griffeth VEM, Buxton RB.A theoretical framework for estimating cerebral oxygen metabolism changes using the calibrated-BOLD method: modeling the effects of blood volume distribution, hematocrit, oxygen extraction fraction, and tissue signal properties on the BOLD signal. NeuroImage 2011; 58: 198–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blockley NP, Griffeth VEM, Simon AB, et al. A review of calibrated blood oxygenation level-dependent (BOLD) methods for the measurement of task-induced changes in brain oxygen metabolism: a review of calibrated BOLD methods. NMR Biomed 2013; 26: 987–1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blockley NP, Griffeth VEM, Stone AJ, et al. Sources of systematic error in calibrated BOLD based mapping of baseline oxygen extraction fraction. NeuroImage 2015; 122: 105–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gjedde A.4.5 Coupling of brain function to metabolism: evaluation of energy requirements. In: Lajtha A, Gibson GE, Dienel GA. (eds) Handbook of neurochemistry and molecular neurobiology. Boston, MA: Springer US, 2007, pp.343–400. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mintun MA, Lundstrom BN, Snyder AZ, et al. Blood flow and oxygen delivery to human brain during functional activity: theoretical modeling and experimental data. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2001; 98: 6859–6864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu F, Liu P, Pascual JM, et al. Effect of hypoxia and hyperoxia on cerebral blood flow, blood oxygenation, and oxidative metabolism. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2012; 32: 1909–1918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ainslie PN, Shaw AD, Smith KJ, et al. Stability of cerebral metabolism and substrate availability in humans during hypoxia and hyperoxia. Clinical Science 2014; 126: 661–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ho Y-CL, Vidyasagar R, Shen Y, et al. The BOLD response and vascular reactivity during visual stimulation in the presence of hypoxic hypoxia. NeuroImage 2008; 41: 179–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tuunanen PI, Kauppinen RA.Effects of oxygen saturation on BOLD and arterial spin labelling perfusion fMRI signals studied in a motor activation task. NeuroImage 2006; 30: 102–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tuunanen PI, Murray IJ, Parry NR, et al. Heterogeneous oxygen extraction in the visual cortex during activation in mild hypoxic hypoxia revealed by quantitative functional magnetic resonance imaging. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2006; 26: 263–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barreto FR, Mangia S, Salmon CEG.Effects of reduced oxygen availability on the vascular response and oxygen consumption of the activated human visual cortex. J Magn Reson Imaging 2017; 46: 142–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang Y, Yin Y, Li H, et al. Measurement of CMRO 2 and its relationship with CBF in hypoxia with an extended calibrated BOLD method. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2020: 2066–2080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sumiyoshi A, Suzuki H, Shimokawa H, et al. Neurovascular uncoupling under mild hypoxic hypoxia: an EEG–fMRI study in rats. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2012; 32: 1853–1858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rostrup E, Larsson HBW, Born AP, et al. Changes in BOLD and ADC weighted imaging in acute hypoxia during sea-level and altitude adapted states. NeuroImage 2005; 28: 947–955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shen Y, Ho Y-CL, Vidyasagar R, et al. Gray matter nulled and vascular space occupancy dependent fMRI response to visual stimulation during hypoxic hypoxia. NeuroImage 2012; 59: 3450–3456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kety SS, Schmidt CF.The effects of altered arterial tensions of carbon dioxide and oxygen on cerebral blood flow and cerebral oxygen consumption of normal young men 1. J Clin Invest 1948; 27: 484–492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peng SL, Ravi H, Sheng M, et al. Searching for a truly ‘iso-metabolic’ gas challenge in physiological MRI. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2017; 37: 715–725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vestergaard MB, Lindberg U, Aachmann-Andersen NJ, et al. Acute hypoxia increases the cerebral metabolic rate – a magnetic resonance imaging study. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2016; 36: 1046–1058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yablonskiy DA, Haacke EM.Theory of NMR signal behavior in magnetically inhomogeneous tissues: the static dephasing regime. Magn Reson Med 1994; 32: 749–763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yin Y, Zhang Y, Gao J-H.Dynamic measurement of oxygen extraction fraction using a multiecho asymmetric spin echo (MASE) pulse sequence: dynamic measurement of oxygen extraction fraction. Magn Reson Med 2018; 80: 1118–1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang Y, Yin Y, Lu J, et al. Detecting resting-state brain activity using OEF-weighted imaging. NeuroImage 2019; 200: 101–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spees WM, Yablonskiy DA, Oswood MC, et al. Water proton MR properties of human blood at 1.5 tesla: Magnetic susceptibility, T1, T2, T*2, and non-Lorentzian signal behavior. Magn Reson Med 2001; 45: 533–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhao JM, Clingman CS, Närväinen MJ, et al. Oxygenation and hematocrit dependence of transverse relaxation rates of blood at 3T. Magn Reson Med 2007; 58: 592–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wong FY, Alexiou T, Samarasinghe TD, et al. Cerebral arterial and venous contributions to tissue oxygenation index measured using spatially resolved spectroscopy in newborn lambs. Anesthesiology 2010; 113: 1385–1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van Zijl PC, Eleff SM, Ulatowski JA, et al. Quantitative assessment of blood flow, blood volume and blood oxygenation effects in functional magnetic resonance imaging. Nat Med 1998; 4: 159–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lin A-L, Fox PT, Yang Y, et al. Evaluation of MRI models in the measurement of CMRO 2 and its relationship with CBF. Magn Reson Med 2008; 60: 380–389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lin A-L, Fox PT, Hardies J, et al. Nonlinear coupling between cerebral blood flow, oxygen consumption, and ATP production in human visual cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2010; 107: 8446–8451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lin A-L, Fox PT, Yang Y, et al. Time-dependent correlation of cerebral blood flow with oxygen metabolism in activated human visual cortex as measured by fMRI. NeuroImage 2009; 44: 16–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vidyasagar R, Kauppinen RA.31P magnetic resonance spectroscopy study of the human visual cortex during stimulation in mild hypoxic hypoxia. Exp Brain Res 2008; 187: 229–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ito H, Ibaraki M, Kanno I, et al. Changes in cerebral blood flow and cerebral oxygen metabolism during neural activation measured by positron emission tomography: comparison with blood oxygenation level-dependent contrast measured by functional magnetic resonance imaging. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2005; 25: 371–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Davis TL, Kwong KK, Weisskoff RM, et al. Calibrated functional MRI: Mapping the dynamics of oxidative metabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1998; 95: 1834–1839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rodgers ZB, Detre JA, Wehrli FW.MRI-based methods for quantification of the cerebral metabolic rate of oxygen. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2016; 36: 1165–1185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sicard KM, Duong TQ.Effects of hypoxia, hyperoxia, and hypercapnia on baseline and stimulus-evoked BOLD, CBF, and CMRO2 in spontaneously breathing animals. NeuroImage 2005; 25: 850–858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lu H, van Zijl PCM.A review of the development of vascular-space-occupancy (VASO) fMRI. NeuroImage 2012; 62: 736–742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kim S-G, Ogawa S.Biophysical and physiological origins of blood oxygenation level-dependent fMRI signals. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2012; 32: 1188–1206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ogawa S, Menon RS, Tank DW, et al. Functional brain mapping by blood oxygenation level-dependent contrast magnetic resonance imaging. A comparison of signal characteristics with a biophysical model. Biophys J 1993; 64: 803–812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Blockley NP, Driver ID, Fisher JA, et al. Measuring venous blood volume changes during activation using hyperoxia. NeuroImage 2012; 59: 3266–3274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kim T, Hendrich KS, Masamoto K, et al. Arterial versus total blood volume changes during neural activity-induced cerebral blood flow change: implication for BOLD fMRI. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2007; 27: 1235–1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kim T, Kim S-G.Temporal dynamics and spatial specificity of arterial and venous blood volume changes during visual stimulation: implication for BOLD quantification. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2011; 31: 1211–1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hua J, Liu P, Kim T, et al. MRI techniques to measure arterial and venous cerebral blood volume. NeuroImage 2019; 187: 17–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.He X, Yablonskiy DA.Quantitative BOLD: Mapping of human cerebral deoxygenated blood volume and oxygen extraction fraction: default state. Magn Reson Med 2007; 57: 115–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jin T, Kim S-G.Change of the cerebrospinal fluid volume during brain activation investigated by T1ρ-weighted fMRI. NeuroImage 2010; 51: 1378–1383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Meyer B, Schultheiß R, Schramm J.Capillary oxygen saturation and tissue oxygen pressure in the rat cortex at different stages of hypoxic hypoxia. Neurol Res 2000; 22: 721–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Leithner C, Royl G.The oxygen paradox of neurovascular coupling. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2014; 34: 19–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cherukara MT, Stone AJ, Chappell MA, et al. Model-based Bayesian inference of brain oxygenation using quantitative BOLD. NeuroImage 2019; 202: 116106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.An H, Lin W.Impact of intravascular signal on quantitative measures of cerebral oxygen extraction and blood volume under normo- and hypercapnic conditions using an asymmetric spin echo approach. Magn Reson Med 2003; 50: 708–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stone AJ, Blockley NP.A streamlined acquisition for mapping baseline brain oxygenation using quantitative BOLD. NeuroImage 2017; 147: 79–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dickson JD, Ash TWJ, Williams GB, et al. Quantitative BOLD: the effect of diffusion. J Magn Reson Imaging 2010; 32: 953–961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stone AJ, Holland NC, Berman AJL, et al. Simulations of the effect of diffusion on asymmetric spin echo based quantitative BOLD: an investigation of the origin of deoxygenated blood volume overestimation. NeuroImage 2019; 201: 116035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Havlicek M, Ivanov D, Poser BA, et al. Echo-time dependence of the BOLD response transients–a window into brain functional physiology. NeuroImage 2017; 159: 355–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cheng Y, van Zijl PCM, Hua J.Measurement of parenchymal extravascular R2* and tissue oxygen extraction fraction using multi-echo vascular space occupancy MRI at 7T: measurement of extravascular bold effects at 7T. NMR Biomed 2015; 28: 264–271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chen JJ, Pike GB.BOLD-specific cerebral blood volume and blood flow changes during neuronal activation in humans. NMR Biomed 2009; 22: 1054–1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wesolowski R, Blockley NP, Driver ID, et al. Coupling between cerebral blood flow and cerebral blood volume: contributions of different vascular compartments. NMR Biomed 2019; 32: e4061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Donahue MJ, Blicher JU, Østergaard L, et al. Cerebral blood flow, blood volume, and oxygen metabolism dynamics in human visual and motor cortex as measured by whole-brain multi-modal magnetic resonance imaging. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2009; 29: 1856–1866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chai Y, Li L, Huber L, et al. Integrated VASO and perfusion contrast: a new tool for laminar functional MRI. NeuroImage 2020; 207: 116358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Angleys H, Østergaard L, Jespersen SN.The effects of capillary transit time heterogeneity (CTH) on brain oxygenation. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2015; 35: 806–817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jespersen SN, Østergaard L.The roles of cerebral blood flow, capillary transit time heterogeneity, and oxygen tension in brain oxygenation and metabolism. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2012; 32: 264–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hudetz AG, Biswal BB, Fehér G, et al. Effects of hypoxia and hypercapnia on capillary flow velocity in the rat cerebral cortex. Microvasc Res 1997; 54: 35–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Stefanovic B, Hutchinson E, Yakovleva V, et al. Functional reactivity of cerebral capillaries. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2008; 28: 961–972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Siesjö BK.Brain energy metabolism. New York: Wiley, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ekström-Jodal B, Elfverson J, von Essen C.Cerebral blood flow, cerebrovascular resistance and cerebral metabolic rate of oxygen in severe arterial hypoxia in dogs. Acta Neurol Scand 1979; 60: 26–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Koehler RC, Traystman RJ, Zeger S, et al. Comparison of cerebrovascular response to hypoxic and carbon monoxide hypoxia in newborn and adult sheep. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 1984; 4: 115–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bhogal AA, Siero JCW, Fisher JA, et al. Investigating the non-linearity of the BOLD cerebrovascular reactivity response to targeted hypo/hypercapnia at 7T. NeuroImage 2014; 98: 296–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Arngrim N, Hougaard A, Schytz HW, et al. Effect of hypoxia on BOLD fMRI response and total cerebral blood flow in migraine with aura patients. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2019; 39: 680–689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tuunanen PI, Vidyasagar R, Kauppinen RA.Effects of mild hypoxic hypoxia on poststimulus undershoot of blood-oxygenation-level-dependent fMRI signal in the human visual cortex. Magn Reson Imaging 2006; 24: 993–999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Buxton RB, Griffeth VEM, Simon AB, et al. Variability of the coupling of blood flow and oxygen metabolism responses in the brain: a problem for interpreting BOLD studies but potentially a new window on the underlying neural activity. Front Neurosci 2014; 8: 139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Toyoda H, Kashikura K, Okada T, et al. Source of nonlinearity of the BOLD response revealed by simultaneous fMRI and NIRS. NeuroImage 2008; 39: 997–1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Shu CY, Sanganahalli BG, Coman D, et al. Quantitative β mapping for calibrated fMRI. NeuroImage 2016; 126: 219–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Valable S, Corroyer-Dulmont A, Chakhoyan A, et al. Imaging of brain oxygenation with magnetic resonance imaging: a validation with positron emission tomography in the healthy and tumoural brain. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2017; 37: 2584–2597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lawley JS, Levine BD, Williams MA, et al. Cerebral spinal fluid dynamics: effect of hypoxia and implications for high-altitude illness. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2016; 120: 251–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Yablonskiy DA.Quantitation of intrinsic magnetic susceptibility‐related effects in a tissue matrix. Phantom study. Magn Reson Med 1998; 39: 417–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Simon AB, Dubowitz DJ, Blockley NP, et al. A novel bayesian approach to accounting for uncertainty in fMRI-derived estimates of cerebral oxygen metabolism fluctuations. NeuroImage 2016; 129: 198–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ni W, Christen T, Zun Z, et al. Comparison of R2′ measurement methods in the normal brain at 3 tesla: comparison of R2′ measurement methods in brain at 3T. Magn Reson Med 2015; 73: 1228–1236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Blockley NP, Stone AJ.Improving the specificity of R2′ to the deoxyhaemoglobin content of brain tissue: prospective correction of macroscopic magnetic field gradients. NeuroImage 2016; 135: 253–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Power JD, Plitt M, Gotts SJ, et al. Ridding fMRI data of motion-related influences: removal of signals with distinct spatial and physical bases in multiecho data. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2018; 115: E2105–E2114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Yang Y, Frank JA, Hou L, et al. Multislice imaging of quantitative cerebral perfusion with pulsed arterial spin labeling. Magn Reson Med 1998; 39: 825–832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Stone AJ, Harston GWJ, Carone D, et al. Prospects for investigating brain oxygenation in acute stroke: experience with a non-contrast quantitative BOLD based approach. Hum Brain Mapp 2019; 40: 2853–2866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Broisat A, Lemasson B, Ahmadi M, et al. Mapping of brain tissue hematocrit in glioma and acute stroke using a dual autoradiography approach. Sci Rep 2018; 8: 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-jcb-10.1177_0271678X21992896 for Effects of mild hypoxia on oxygen extraction fraction responses to brain stimulation by Yayan Yin, Su Shu, Lang Qin, Yi Shan, Jia-Hong Gao and Jie Lu in Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism