Abstract

BACKGROUND

The ongoing coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has significantly disrupted both elective and acute medical care. Data from the early months suggest that acute care patient populations deferred presenting to the emergency department (ED), portending more severe disease at the time of presentation. Additionally, care for this patient population trended towards initial non-operative management.

AIM

To examine the presentation, management, and outcomes of patients who developed gallbladder disease or appendicitis during the pandemic.

METHODS

A retrospective chart review of patients diagnosed with acute cholecystitis, symptomatic cholelithiasis, or appendicitis in two EDs affiliated with a single tertiary academic medical center in Northern California between March and June, 2020 and in the same months of 2019. Patients were selected through a research repository using international classification of diseases (ICD)-9 and ICD-10 codes. Across both years, 313 patients were identified with either type of gallbladder disease, while 361 patients were identified with acute appendicitis. The primary outcome was overall incidence of disease. Secondary outcomes included presentation, management, complications, and 30-d re-presentation rates. Relationships between different variables were explored using Pearson’s r correlation coefficient. Variables were compared using the Welch’s t-Test, Chi-squared tests, and Fisher’s exact test as appropriate.

RESULTS

Patients with gallbladder disease and appendicitis both had more severe presentations in 2020. With respect to gallbladder disease, more patients in the COVID-19 cohort presented with acute cholecystitis compared to the control cohort [50% (80) vs 35% (53); P = 0.01]. Patients also presented with more severe cholecystitis in 2020 as indicated by higher mean Tokyo Criteria Scores [mean (SD) 1.39 (0.56) vs 1.16 (0.44); P = 0.02]. With respect to appendicitis, more patients were diagnosed with a perforated appendix at presentation in 2020 [20% (36) vs 16% (29); P = 0.02] and a greater percentage were classified as emergent cases using the emergency severity index [63% (112) vs 13% (23); P < 0.001]. While a greater percentage of patients were admitted to the hospital for gallbladder disease in 2020 [65% (104) vs 50% (76); P = 0.02], no significant differences were observed in hospital admissions for patients with appendicitis. No significant differences were observed in length of hospital stay or operative rate for either group. However, for patients with appendicitis, 30-d re-presentation rates were significantly higher in 2020 [13% (23) vs 4% (8); P = 0.01].

CONCLUSION

During the COVID-19 pandemic, patients presented with more severe gallbladder disease and appendicitis. These findings suggest that the pandemic has affected patients with acute surgical conditions.

Keywords: COVID-19, Cholecystitis, Biliary colic, Appendicitis, Acute care surgery

Core Tip: The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has impacted patients with a wide range of diseases due to stay-at-home orders and concerns surrounding the safety and feasibility of accessing care. This study demonstrates that the pandemic resulted in more severe presentations of gallbladder disease and appendicitis, which may be related to delays prior to presentation. Additionally, the pandemic influenced the management of patients with acute surgical conditions, and affected outcomes for patients with acute appendicitis. These findings can inform policy and public messaging surrounding stay-at-home orders and access to care during future COVID-19 surges.

INTRODUCTION

Early-on, the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic [coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)] necessitated widespread shifts throughout healthcare systems in an effort to preserve hospital resources, maintain capacity, and minimize infection risk[1,2]. Consequently, surgeons have faced unique changes in their clinical practice. Beginning in March of 2020, hospitals and surgical centers around the world began postponing elective interventions and minimizing operative management of emergency general surgery conditions[3-6]. At the same time, global reports suggest that public fear in conjunction with stay-at-home orders may have discouraged patients with acute conditions from presenting for care in a timely manner, resulting in increased morbidity[7-11]. As of June 2020, an estimated 41% of United States adults reported having delayed or avoided medical consultation, 12% of which was for urgent or emergent medical needs[12].

Gallbladder disease and appendicitis are common surgical conditions diagnosed among patients presenting to the emergency department (ED). Approximately 600000 cholecystectomies[13] and 280000 appendectomies[14] are performed in the United States annually. Cholecystectomy is the standard of care for both symptomatic cholelithiasis[15] and acute cholecystitis[16]; however, timing of surgery (e.g., elective vs urgent) is dependent on the patient’s symptoms[15]. With persistent symptoms, the cost of delayed surgical intervention is significant as individuals with untreated cholelithiasis and cholecystitis are at risk of developing recurrent symptoms, severe pain, biliary tract obstruction, and pancreatitis[16,17]. Similarly, appendectomy is the standard of care for uncomplicated appendicitis; however, antibiotic management can be a successful treatment modality[18,19]. Untreated appendicitis can lead to recurrent disease or progress to perforation and peritonitis; therefore, excessive delays in treatment should be avoided[18].

Much remains to be determined about how COVID-19 has impacted the presentation, management, and outcomes of patients with emergency general surgery conditions. We sought to assess the effect of the pandemic on cholecystitis, cholelithiasis, and appendicitis in Santa Clara County, California in the months following the region’s initial stay-at-home order.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient cohort and data collection

This retrospective study was designed to examine patients who presented to our tertiary academic medical center and an affiliate ED utilizing the Stanford Research Repository Database, an IRB-approved resource for aggregating clinical data. This study was conducted after approval by the Stanford University Institutional Review Board, No. 56347.

Patients presenting between March-June, 2019 (control cohort) and March-June, 2020 (COVID-19 cohort) with acute cholecystitis, symptomatic cholelithiasis, or appendicitis were included. Patients were identified using international classification of diseases (ICD)-9 and ICD-10 codes. Patients with incidental findings of cholelithiasis, chronic biliary colic unrelated to the chief complaint at time of presentation, biliary tract malignancy and acute biliary pancreatitis were excluded from the gallbladder cohort. Patients with appendectomy unrelated to appendicitis or malignancy were excluded from the appendicitis cohort.

Records were reviewed by medical students (O.F, G.G, A.F, C.P, A.K, C.W), a surgical trainee (A.T), and an attending surgeon (M.E.) who performed standardized abstraction on eligible patients. Demographic and clinical data were retrospectively reviewed and recorded. Additionally, hospital admission, treatment modalities (operative vs non-operative management), time to intervention, length of hospital stay, surgical findings, complication rates, and 30-d re-presentation rates were recorded. Emergency severity index (ESI), which stratifies patients in the ED into five groups ranging from 1 (most urgent) to 5 (least urgent), and the Tokyo Guidelines severity grade of cholecystitis were calculated for each patient[20,21].

Data analysis

Relationships between different variables were explored using Pearson’s r correlation coefficient. Data were presented as number (%), mean (SD), or median (IQR). Variables were compared using the Welch’s t-test, Chi-squared tests, and Fisher’s exact test as appropriate. Statistical analysis was performed using R version 1.3.1056 and STATA version 15. Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Study population characteristics

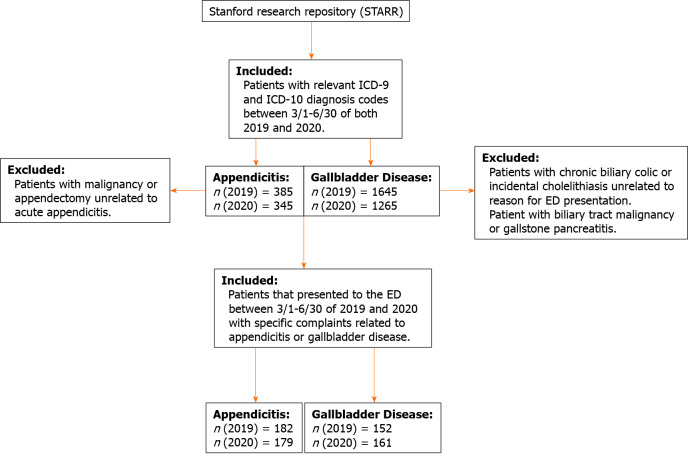

Seven hundred and nine patients were identified overall. Three-hundred and thirteen patients with gallbladder disease (Figure 1) were identified. Of those, 161 patients presented in 2020 [median age (IQR) 49 (35-61) years; 93 (58%) female; 58 (36%) white] while 152 patients presented in 2019 [median (IQR) 46 (33-65) years; 97 (65%) female; 58 (38%) white]. Three-hundred and sixty nine patients with acute appendicitis were identified (Figure 1), with 179 presenting in 2020 [median age (IQR) 32 (15-49); 82 (46) female; 79 (44%) white] and 182 in 2019 [median age (SD) 25 (14-47); 77 (42%) female; 96 (53%) white]. There were no significant differences between the COVID-19 and control cohorts in either disease group with respect to age, gender, race, body mass index, interpreter needs, or Charlson Comorbidity Index (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Cohort selection. ED: Emergency departments; ICD: International classification of diseases.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of patients, stratified by cohort and time period

|

Appendicitis

|

Gallbladder disease

|

|||||||||

|

March–June 2019

|

March–June 2020

|

P value |

March–June 2019

|

March–June 2020

|

P value | |||||

|

n

|

(%)

|

n

|

(%)

|

n

|

(%)

|

n

|

(%)

|

|||

| Demographics | 182 | 50 | 179 | 50 | 152 | 49 | 161 | 51 | ||

| Age, median (IQR) | 24.9 | 13.8–47.2 | 32.2 | 15.1–48.9 | 0.33 | 46.7 | 32.6–65.3 | 48.8 | 35.4–61.4 | 0.99 |

| Gender, n (%) | 0.57 | 0.33 | ||||||||

| Female | 77 | 42 | 82 | 46 | 97 | 64 | 93 | 58 | ||

| Male | 105 | 58 | 97 | 54 | 55 | 36 | 68 | 42 | ||

| Race, n (%) | 0.35 | 0.98 | ||||||||

| White | 96 | 53 | 79 | 44 | 58 | 32 | 58 | 32 | ||

| Black or African American | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 7 | 4 | 8 | 4 | ||

| Asian | 35 | 19 | 40 | 22 | 29 | 16 | 31 | 17 | ||

| Other | 50 | 27 | 57 | 32 | 58 | 32 | 64 | 36 | ||

| Interpreter needed, n (%) | 25 | 14 | 24 | 13 | > 0.99 | 23 | 13 | 28 | 16 | 0.68 |

| Spanish | 21 | 84 | 18 | 75 | 0.50 | 20 | 87 | 24 | 86 | 0.78 |

| BMI, median (IQR) | 24.2 | 20.2–29.8 | 23.1 | 19.9–27.5 | 0.13 | 28.8 | 25.8–32.5 | 29.5 | 24.5–33.9 | 0.73 |

| Charlson Comorbidity score | 0.35 | 0.22 | ||||||||

| None: CCI score 0, n (%) | 136 | 75 | 133 | 74 | 80 | 53 | 69 | 43 | ||

| Mild: CCI score 1-2, n (%) | 31 | 17 | 24 | 13 | 33 | 22 | 46 | 29 | ||

| Moderate: CCI score 3-4, n (%) | 12 | 7 | 14 | 8 | 21 | 14 | 26 | 16 | ||

| Severe: CCI ≥ 5, n (%) | 3 | 2 | 8 | 4 | 14 | 9 | 19 | 12 | ||

CCI: Comprehensive complication index; BMI: Body mass index.

Two patients in the gallbladder group (1%) and zero in the appendicitis group were confirmed positive for SARS-CoV-2 in 2020. One patient with symptomatic cholelithiasis was discharged directly from the ED with a COVID-positive test resulting after the time of discharge. The second patient was admitted to the hospital for magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography to evaluate for possible choledocholithiasis, which was negative. The patient was found to be COVID positive on admission and was transferred to the COVID isolation unit before being discharged home to self-isolate.

Presentation

Cholecystitis and cholelithiasis: The share of patients with acute cholecystitis was greater during the COVID-19 pandemic compared to the year prior (50% vs 35%; P = 0.01), with the remaining patients presenting with biliary colic (50% vs 65%; P = 0.01). Although not statistically significant, the duration of symptoms prior to presentation was longer in the COVID-19 cohort than in the control group [mean (SD) 4.2 d (12.7) vs 2.9 d (5.8); P = 0.212]. Mean Tokyo Criteria Guidelines grade was higher in the COVID-19 cohort with acute cholecystitis compared to the control group [mean (SD) 1.39 (0.562) vs 1.17 (0.437); P = 0.02] (Table 2). Overall severity of presentation was similar between cohorts. Seven percent of patients in 2020 and 5% in 2019 were classified as emergent presentations by an ESI score of 2 (P = 0.60, Table 3).

Table 2.

Gallbladder disease presentation, management, and operative findings

|

Gallbladder disease

|

|||||

|

March–June 2019

|

March–June 2020

|

P value | |||

|

152

|

161

|

||||

| Diagnosis, n (%) | 0.01 | ||||

| Symptomatic cholelithiasis | 99 | 65% | 81 | 50% | |

| Acute cholecystitis | 53 | 35% | 80 | 50% | |

| Tokyo criteria, mean (STD) | 1.17 | 0.437 | 1.39 | 0.562 | 0.02 |

| Symptom duration prior to ED (d), mean (STD) | 2.9 | 5.8 | 4.2 | 12.7 | 0.21 |

| ED length of stay (h), median (IQR) | 5 | (3.5–7) | 5 | (4–7) | 0.55 |

| Disposition from ED | 0.02 | ||||

| Discharged, n (%) | 52 | 34% | 41 | 25% | |

| Discharged with urgent follow up, n (%) | 17 | 11% | 15 | 9% | |

| Admitted, n (%) | 76 | 50% | 104 | 65% | |

| Other, n (%) | 7 | 5% | 1 | 1% | |

| Time from presentation to OR (h), median (IQR) | 18 | (11–28.2) | 19 | (13–27.5) | 0.42 |

| Pre-op ERCP required, n (%) | 22 | 14% | 18 | 11% | 0.40 |

| Antibiotics during admission, n (%) | 61 | 80% | 98 | 94% | 0.10 |

| Underwent surgical procedure, n (%) | 61 | 40% | 83 | 52% | 0.06 |

| Symptomatic cholelithiasis | 16 | 16% | 22 | 27% | 0.098 |

| Acute cholecystitis | 45 | 87% | 61 | 76% | 0.12 |

| Operations performed, n (%) | 0.75 | ||||

| Laparoscopic cholecystectomy | 55 | 90% | 75 | 90% | |

| Laparoscopic converted to open cholecystectomy | 2 | 3% | 1 | 1% | |

| Percutaneous cholecystostomy | 4 | 7% | 7 | 8% | |

| Post-op diagnosis, n (%) | 0.23 | ||||

| Acute cholecystitis only | 38 | 62% | 43 | 52% | |

| Acute cholecystitis with gallbladder mucocele (Hydrops) | 1 | 2% | 2 | 3% | |

| Acute gangrenous cholecystitis | 6 | 10% | 14 | 17% | |

| Acute hemorrhagic cholecystitis | 1 | 2% | 0 | 0% | |

| Symptomatic cholelithiasis | 6 | 10% | 11 | 13% | |

| Chronic cholecystitis | 1 | 2% | 8 | 10% | |

| Other | 7 | 12% | 6 | 7% | |

| Choledocholithiasis present, n (%)–Biliary colic subgroup | 24 | 16% | 28 | 17% | 0.92 |

| Drains left in place post op, n (%) | 8 | 13% | 15 | 18% | 0.39 |

| Patients with additional procedures, n (%) | 8 | 13% | 7 | 8% | 0.40 |

| Drain placement | 1 | 6% | 0 | 0% | |

| PICC line | 0 | 0% | 1 | 7% | |

| Lysis of adhesions | 0 | 0% | 2 | 13% | |

| Intra-op cholangiogram | 1 | 6% | 1 | 7% | |

ED: Emergency departments; ERCP: Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; OR: Odds ratios; PICC: Peripherally inserted central catheters.

Table 3.

Gallbladder disease postoperative course and complications

|

Gallbladder disease

|

|||||

|

March–June 2019

|

March–June 2020

|

P value | |||

|

152

|

161

|

||||

| Length of stay for surgically managed patients (d), median (IQR) | 3 | (2–4) | 2 | (1–3) | 0.3 |

| Discharged on antibiotics, n (%) | 21 | 14% | 29 | 18% | 0.39 |

| Inpatient complications, n (%) | 10 | 16% | 11 | 13% | 0.62 |

| Sepsis | 0 | 0% | 4 | 5% | |

| Transaminitis | 1 | 2% | 1 | 1% | |

| Death | 0 | 0% | 1 | 1% | > 0.99 |

| Representation within 30 d, n (%) | 16 | 11% | 20 | 12% | 0.71 |

| Postoperative intra-abdominal abscess | 0 | 0% | 1 | 1% | |

| Cholecystitis | 3 | 2% | 4 | 2% | |

| Cholelithiasis/Choledocholithiasis | 1 | 1% | 5 | 3% | |

Appendicitis: More patients presenting during the COVID-19 pandemic had severe cases of appendicitis as indicated by lower (i.e. more severe) ESI [mean (SD) 2.37 (0.49) vs 2.87 (0.33); P < 0.001]. There was no significant difference in the Alvarado scores between the two cohorts (mean (SD) 6.50 (1.89) in 2020 vs 6.53 (1.82) in 2019; P = 0.63, Table 4).

Table 4.

Appendicitis presentation, management, and operative findings

|

|

Appendicitis

|

||||

|

March–June 2019

|

March–June 2020

|

P value | |||

|

182

|

179

|

||||

| Alvarado score, mean (SD) | 6.53 | 1.82 | 6.50 | 1.89 | 0.63 |

| Ruptured appendix, n (%) at diagnosis | 29 | 16% | 36 | 20% | 0.02 |

| Ruptured appendix, n (%) post op | 43 | 23% | 41 | 23% | 0.68 |

| Symptom duration prior to ED (d), mean (SD) | 2.72 | 7.23 | 2.19 | 3.12 | 0.36 |

| ED severity score, mean (SD) | 2.87 | 0.33 | 2.37 | 0.49 | < 0.0001 |

| Resucitation, n (%)) | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | |

| Emergent, n (%) | 23 | 13% | 112 | 63% | |

| Non-emergent, n (%) | 159 | 87% | 67 | 37% | |

| ED length of stay (h), median (IQR) | 5.00 | 3.5–6.6 | 6.00 | 4–7 | 0.51 |

| Disposition from ED | 0.57 | ||||

| Discharged, n (%) | 3 | 2% | 3 | 2% | |

| Discharged with urgent follow up, n (%) | 0 | 0% | 1 | 1% | |

| Admitted, n (%) | 174 | 96% | 173 | 97% | |

| Underwent surgical procedure, n (%) | 150 | 82% | 156 | 87% | 0.47 |

| Laparoscopic appendectomy | 145 | 97% | 149 | 96% | |

| Laparoscopic converted to open appendectomy | 2 | 1% | 1 | 1% | |

| Right hemicolectomy | 2 | 1% | 0 | 0% | |

| Percutaneous abscess drain (IR) | 1 | 1% | 6 | 4% | |

| Post-op diagnosis, n (%) | |||||

| Ruptured appendix | 43 | 29% | 41 | 26% | 0.68 |

| Appendix not ruptured | 106 | 71% | 116 | 74% | |

| Time from presentation to OR (h), median (IQR) | 11.2 | 6–17 | 11.0 | 6–17 | 0.38 |

| Drains left in place post op, n (%) | 6 | 4% | 11 | 7% | 0.07 |

| Patients with additional procedures, n (%) | 17 | 11% | 11 | 7% | 0.27 |

| Draining of abscess | 7 | 41% | 2 | 18% | |

| Bowel resection | 2 | 12% | 0 | 0% | |

| Drain placement | 3 | 18% | 1 | 9% | |

| PICC line | 1 | 6% | 2 | 18% | |

| NGT placement | 0 | 0% | 2 | 18% | |

ED: Emergency departments; OR: Odds ratios; PICC: Peripherally inserted central catheters; IR: Immunoreactive; NGT: Nasogastric tube.

Management

Cholecystitis and cholelithiasis: During COVID-19, more patients with gallbladder disease were admitted to the hospital from the ED than in the year prior (65% vs 50%; P = 0.02) (Table 2). Although not statistically significant, the operative rate was overall higher in the COVID-19 cohort (52% in 2020 vs 40% in 2019; P = 0.06). However, split by disease group, a greater proportion of patients with symptomatic cholelithiasis underwent surgery (27% in 2020 vs 16% in 2019) while a smaller share of patients with acute cholecystitis were operated on in 2020 (76% in 2020 vs 87% in 2019). Of those managed surgically, laparoscopic cholecystectomy rates were comparable (90% in both years), with conversion to open cholecystectomy in 1% and 3% of cases, respectively (P = 0.8) (Table 2). Eight percent of patients in 2020 and 7% in 2019 underwent percutaneous cholecystostomy. There was no significant difference in time from presentation to operative intervention [median (IQR) 19 (13-28) h in 2020 vs 18 (11-28) h in 2019, Table 3].

Appendicitis: Hospital admission rates (97% vs 96%; P = 0.68) and operative rates (87% vs 82%; P = 0.47) did not differ between 2020 and 2019 (Table 4). There was a positive correlation between surgical intervention and diagnosis of ruptured appendix (P < 0.05) (Supplementary Tables 1-3). In those managed surgically, laparoscopic appendectomy rates were similar (96% in 2020 vs 97% in 2019), and only 1% of cases in either cohort required conversion to open appendectomy. Additionally, there was a trend toward increased intraoperative drain placement in 2020 (7% vs 4%; P = 0.07). There was no significant difference in the time from ED presentation to operation between the two cohorts [median (IQR) 11 (6-17) h in 2020 vs 11 (6-17) h in 2019; P = 0.38] (Table 4).

Outcomes

Cholecystitis and cholelithiasis: Most patients with gallbladder disease who underwent surgery had a pathologic diagnosis of acute cholecystitis, including acute cholecystitis with gallbladder mucocele, acute gangrenous cholecystitis, and acute hemorrhagic cholecystitis (52% in 2020 vs 62% in 2019, Table 2). Of those with a preoperative diagnosis of acute cholecystitis, fewer patients underwent surgery in 2020 (76% vs 85%; P = 0.12). The number of patients with gangrenous cholecystitis did not differ between years (17% vs 10%; P = 0.30). Median hospital length of stay for surgically-managed patients was similar between groups [median (IQR) 2 (1-3) in 2020 vs 3 (2-4) in 2019; P = 0.30]. Additionally, rate of discharge on antibiotics (14% in 2020 vs 18% in 2019; P = 0.4) and the rate of 30-d re-presentations to the hospital (12% in 2020 vs 11% in 2019; P = 0.71) did not differ across the years (Table 3). There was one death during admission among the COVID-19 cohort and none in the control group (P > 0.99).

Appendicitis: More patients in the COVID-19 cohort were diagnosed with perforated appendicitis at presentation compared to the year prior (20% vs 16%; P = 0.02). However, there was no significant difference in postoperative diagnosis of ruptured appendicitis between the cohorts (P = 0.68). The rate of ruptured appendicitis was higher in both cohorts when diagnosed postoperatively compared to diagnosis at the time of presentation (23% vs 20% in 2020; P < 0.01 and 23% vs 16% in 2019; P < 0.01). Of those admitted, the length of hospital stay did not differ between cohorts [median (IQR) 2 (2-3) vs 2 (2-3); P > 0.99] (Table 5).

Table 5.

Appendicitis postoperative course and complications

|

|

Appendicitis

|

||||

|

March–June 2019

|

March–June 2020

|

P value | |||

|

182

|

179

|

||||

| Length of stay (d), median (IQR) | 2.00 | 2–3 | 2.00 | 2–3 | > 0.99 |

| Discharged on antibiotics, n (%) | 35 | 19% | 52 | 29% | 0.04 |

| Patients with Inpatient complications, n (%) | 5 | 3% | 10 | 6% | 0.32 |

| Sepsis | 0 | 0% | 2 | 18% | |

| Post op ileus | 3 | 27% | 2 | 18% | |

| Abscess | 3 | 27% | 0 | 0% | |

| Representation within 30 d, n (%) | 8 | 4% | 23 | 13% | < 0.01 |

Patients in the COVID-19 cohort were more likely to be discharged on antibiotics (29% vs 19%; P = 0.04). Antibiotic prescription upon discharge was positively correlated with the duration of symptoms prior to ED presentation (P < 0.05) (Supplementary Table 2). Additionally, the 30-d representation rate was significantly higher in 2020 than in 2019 (13% vs 4%; P = 0.01). There was no significant difference between the two cohorts with regards to complication rate or the rate of additional procedures (Tables 4 and 5).

DISCUSSION

In our study, both patients with gallbladder disease and appendicitis presented with more severe cases during the COVID-19 pandemic.

For the gallbladder cohort, more patients were diagnosed with acute cholecystitis and fewer with symptomatic cholelithiasis during the pandemic, although overall rates of gallbladder disease were unchanged between the years. These findings deviate from a recent study that did, in fact, demonstrate an increased incidence of acute calculous cholecystitis during the pandemic, which the authors attributed primarily to greater consumption of fatty foods[22]. Our finding of proportionally fewer cases of symptomatic cholelithiasis suggests that patients may not have visited the ED for less severe or intermittent symptoms. Furthermore, since untreated biliary colic can progress to cholecystitis[22], this may have also accounted for the relative rise in acute cholecystitis cases in 2020.

Patients diagnosed with cholecystitis during the pandemic had more severe disease as evidenced by higher mean Tokyo Criteria scores. Although the difference in symptom duration prior to presentation did not reach statistical significance, it is plausible that delays in presentation partially accounted for the observed severity rise, as symptom duration ≥ 72 h increases the severity score from Tokyo Criteria grade I to grade II[23].

With more patients presenting with acute cholecystitis and of a higher grade, it follows that a greater proportion of patients with gallbladder disease were admitted to the hospital in 2020–even when system-wide efforts aimed to reduce non-COVID-related hospitalizations. Our finding again deviates from a previous report that found that, in New York City, hospitalizations for biliary disease decreased during the peak months of the pandemic period[24]. Interestingly, this same study notes that after the peak, overall non-COVID-related hospitalization rates rose slightly.

Similar to the gallbladder disease cohort, although rates of presentations for appendicitis remained stable during the pandemic, a greater proportion of patients presented with more severe appendicitis cases in 2020 as demonstrated by higher ED severity scores, higher drain placement rates, and higher antibiotic rates at discharge. Furthermore, more patients in the COVID-19 appendicitis cohort were diagnosed with perforated appendicitis at presentation. If appendicitis is untreated, the risk of rupture has been shown to rise over the first 36 h after symptom onset[25]. Although, like in gallbladder disease, the increase in duration of appendicitis symptoms during the pandemic did not reach statistical significance in our study, the higher rate of perforation could support a delay in appendicitis care.

Our findings are consistent with a robust body of literature evidencing increased incidence of complicated appendicitis (e.g., perforation, peri-appendicular abscess, and gangrenous appendicitis) during the COVID-19 pandemic[26-28]. Prior work has found higher rates of perforated appendixes in children during the pandemic, as well as longer mean duration of symptoms in those children with perforations[27]. In patients of all ages, one study noted a delay between onset of symptoms and presentation for care in both the elderly and groups at high-risk for COVID-19[28].

With regards to management, non-operative management of appendicitis increased during COVID-19, with no lower failure rates than reported in meta-analyses published prior to the pandemic[29]. In our study however, the only component of management that differed between the two appendicitis cohorts was an increase in antibiotic administration upon discharge. While outcomes also were largely consistent between the years, more patients diagnosed with appendicitis in 2020 re-presented to the ED within 30 d of discharge, suggesting that they experienced a greater number and/or greater severity of complications after their initial presentation.

Understanding such changes in presentation, management, and outcomes of various disease processes during the COVID-19 pandemic is essential for preparing for any future surges or other public health crises. Multiple studies have previously reported delays in medical care attributable to COVID-19, resulting in higher morbidity and mortality[30-33]. Stay-at-home orders and social distancing guidelines, fear of contracting coronavirus, and concerns regarding overburdening the healthcare system are just some of the factors that may have influenced patients’ delayed presentation for care and resulting clinical status[34,35]. Our finding, that patients with gallbladder disease and appendicitis also presented with disease of greater severity, adds to the body of literature raising concerns around the need to limit healthcare utilization during the pandemic, while also ensuring that patients do not avoid care at the cost of developing more advanced disease.

Limitations

Although Santa Clara County experienced the first stay-at-home order in the United States due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the academic center where this study was completed did not have a surge in coronavirus infections during the study period. Case load in the area remained relatively well-controlled, reaching 4600 total cases between the beginning of the pandemic and the end of our study period (Santa Clara County population: 1.928 million)[36]. Although elective procedures were suspended for several months, those presenting with urgent/emergent abdominal complaints were still able to access care. This study is perhaps a more sensitive measure of how fear changed patient behavior during the pandemic rather than of changes in actual healthcare capacity. Outcomes of acute care surgical procedures may be different in an area harder-hit by the pandemic and more affected by provider and healthcare capacity limitations.

CONCLUSION

We found that patients during the COVID-19 pandemic were more likely to present with more advanced gallbladder and appendicitis pathology compared to the same time period in 2019. Management of these acute surgical conditions differed during the pandemic in that, for gallbladder disease, a greater proportion of patients were admitted to the hospital, while for appendicitis, more patients received antibiotics at the time of discharge. Measures of patient outcomes did not meaningfully differ for gallbladder disease, but 30-d re-presentations were increased for patients with acute appendicitis.

It appears that the pandemic has affected patient decision-making, provider management approaches, as well as outcomes of acute care surgical conditions. As the response to the pandemic evolves on a local and national level, future research should continue to evaluate the effect of both patient behavior and guidelines for surgeons on outcomes for acute care surgical conditions. Projects such as the ongoing CholeCOVID study, which is auditing the impact of COVID-19 on patients with cholecystitis, may help guide management of this disease during future surges.

Additionally, attention is needed to strike a balance between discouraging excess healthcare utilization while also encouraging patients to seek care when necessary so as to avoid increased morbidity and mortality, and their accompanying costs to the health care system. Our study, among others, can help inform public messaging around healthcare utilization as the pandemic continues or future crises arise.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

Data from the early months of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic suggest that acute care patient populations deferred presenting to the emergency department (ED), portending more severe disease at the time of presentation. Additionally, care for this patient population trended towards initial non-operative management.

Research motivation

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has significantly disrupted both elective and acute medical care. Understanding the pandemic’s impact on acute care surgery patients can help inform responses to future COVID-19 surges or other public health crises.

Research objectives

The aim of this study was to examine the presentation, management, and outcomes of patients who developed gallbladder disease or appendicitis during the pandemic.

Research methods

A retrospective chart review of patients diagnosed with acute cholecystitis, symptomatic cholelithiasis, or appendicitis in two EDs affiliated with a single tertiary academic medical center in Northern California between March and June, 2020 and in the same months of 2019.

Research results

Patients with gallbladder disease and appendicitis both had more severe presentations during the pandemic in 2020 as compared to the year prior.

Research conclusions

The pandemic has affected patients with acute surgical conditions.

Research perspectives

These findings can inform policy and public messaging surrounding stay-at-home orders and access to care during future COVID-19 surges.

Footnotes

Institutional review board statement: The study was reviewed and approved by the Stanford University Institutional Review Board, No. 56347.

Informed consent statement: This retrospective chart review study is exempt from requiring informed consent.

Conflict-of-interest statement: There are no conflicts of interest to report.

STROBE statement: The authors have read the STROBE Statement—checklist of items, and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the STROBE Statement—checklist of items.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Peer-review started: April 1, 2021

First decision: May 13, 2021

Article in press: July 9, 2021

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: United States

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Ozair A S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: A P-Editor: Yuan YY

Contributor Information

Orly Nadell Farber, Department of Surgery, Stanford University School of Medicine, Palo Alto, CA 94305, United States.

Giselle I Gomez, Department of Surgery, Stanford University School of Medicine, Palo Alto, CA 94305, United States.

Ashley L Titan, Department of Surgery, Stanford University School of Medicine, Palo Alto, CA 94305, United States.

Andrea T Fisher, Department of Surgery, Stanford University School of Medicine, Palo Alto, CA 94305, United States.

Christopher J Puntasecca, Department of Surgery, Stanford University School of Medicine, Palo Alto, CA 94305, United States.

Veronica Toro Arana, Department of Surgery, Stanford University School of Medicine, Palo Alto, CA 94305, United States.

Arielle Kempinsky, Department of Surgery, Stanford University School of Medicine, Palo Alto, CA 94305, United States.

Clare E Wise, Department of Surgery, Stanford University School of Medicine, Palo Alto, CA 94305, United States.

Kovi E Bessoff, Department of Surgery, Stanford University School of Medicine, Palo Alto, CA 94305, United States.

Mary T Hawn, Department of Surgery, Stanford University School of Medicine, Palo Alto, CA 94305, United States.

James R Korndorffer, Jr, Department of Surgery, Stanford University School of Medicine, Palo Alto, CA 94305, United States.

Joseph D Forrester, Department of Surgery, Stanford University School of Medicine, Palo Alto, CA 94305, United States.

Micaela M Esquivel, Department of Surgery, Stanford University School of Medicine, Palo Alto, CA 94305, United States. mesquive@stanford.edu.

Data sharing statement

Technical appendix, statistical code, and dataset available from the corresponding author at mesquive@stanford.edu. No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Cheeyandira A. The effects of COVID-19 pandemic on the provision of urgent surgery: a perspective from the USA. J Surg Case Rep. 2020;2020:rjaa109. doi: 10.1093/jscr/rjaa109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klein MJ, Frangos SG, Krowsoski L, Tandon M, Bukur M, Parikh M, Cohen SM, Carter J, Link RN, Uppal A, Pachter HL, Berry C. Acute Care Surgeons' Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic: Observations and Strategies From the Epicenter of the American Crisis. Ann Surg. 2020;272:e66–e71. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000004028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coronavirus Disease 2019. Non-Emergent, Elective Medical Services, and Treatment Recommendations. [cited 10 February 2021]. Available from: https://www.medicaid.gov/resources-for-states/disaster-response-toolkit/coronavirus-disease-2019-covid-19/index.html .

- 4.ASCA State Guidance of Elective Surgeries. [cited 10 February 2021]. Available from: https://www.ascassociation.org/asca/resourcecenter/Latestnewsresourcecenter/covid-19/covid-19-state .

- 5.American College of Surgeons. COVID-19 Guidelines for Triage of Emergency General Surgery Patients. [cited 10 February 2021]. Available from: https://www.facs.org/covid-19/clinical-guidance/elective-case/emergency-surgery .

- 6.COVIDSurg Collaborative. Mortality and pulmonary complications in patients undergoing surgery with perioperative SARS-CoV-2 infection: an international cohort study. Lancet. 2020;396:27–38. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31182-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cozza V, Fransvea P, La Greca A, De Paolis P, Marini P, Zago M, Sganga G I -ACTSS.-COVID19 Collaborative Study Group. I-ACTSS-COVID-19-the Italian acute care and trauma surgery survey for COVID-19 pandemic outbreak. Updates Surg. 2020;72:297–304. doi: 10.1007/s13304-020-00832-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cano-Valderrama O, Morales X, Ferrigni CJ, Martín-Antona E, Turrado V, García A, Cuñarro-López Y, Zarain-Obrador L, Duran-Poveda M, Balibrea JM, Torres AJ. Acute Care Surgery during the COVID-19 pandemic in Spain: Changes in volume, causes and complications. A multicentre retrospective cohort study. Int J Surg. 2020;80:157–161. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Romero J, Valencia S, Guerrero A. Acute Appendicitis During Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): Changes in Clinical Presentation and CT Findings. J Am Coll Radiol. 2020;17:1011–1013. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2020.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Callan R, Assaf N, Bevan K. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Acute General Surgical Admissions in a District General Hospital in the United Kingdom: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Surg Res Pract. 2020;2020:2975089. doi: 10.1155/2020/2975089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chew NW, Ow ZGW, Teo VXY, Heng RRY, Ng CH, Lee CH, Low AF, Chan MY, Yeo TC, Tan HC, Loh PH. The Global Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on STEMI care: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Can J Cardiol. 2021:S0828–282X(21)00179. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2021.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Czeisler MÉ, Marynak K, Clarke KEN, Salah Z, Shakya I, Thierry JM, Ali N, McMillan H, Wiley JF, Weaver MD, Czeisler CA, Rajaratnam SMW, Howard ME. Delay or Avoidance of Medical Care Because of COVID-19-Related Concerns - United States, June 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1250–1257. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6936a4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Glasgow RE, Cho M, Hutter MM, Mulvihill SJ. The spectrum and cost of complicated gallstone disease in California. Arch Surg. 2000;135:1021–5; discussion 1025-7. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.135.9.1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Livingston EH, Woodward WA, Sarosi GA, Haley RW. Disconnect between incidence of nonperforated and perforated appendicitis: implications for pathophysiology and management. Ann Surg. 2007;245:886–892. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000256391.05233.aa. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hassler KR, Collins JT, Philip K, Jones MW. Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy. 2021 Apr 21. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan–. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ansaloni L, Pisano M, Coccolini F, Peitzmann AB, Fingerhut A, Catena F, Agresta F, Allegri A, Bailey I, Balogh ZJ, Bendinelli C, Biffl W, Bonavina L, Borzellino G, Brunetti F, Burlew CC, Camapanelli G, Campanile FC, Ceresoli M, Chiara O, Civil I, Coimbra R, De Moya M, Di Saverio S, Fraga GP, Gupta S, Kashuk J, Kelly MD, Koka V, Jeekel H, Latifi R, Leppaniemi A, Maier RV, Marzi I, Moore F, Piazzalunga D, Sakakushev B, Sartelli M, Scalea T, Stahel PF, Taviloglu K, Tugnoli G, Uraneus S, Velmahos GC, Wani I, Weber DG, Viale P, Sugrue M, Ivatury R, Kluger Y, Gurusamy KS, Moore EE. 2016 WSES guidelines on acute calculous cholecystitis. World J Emerg Surg. 2016;11:25. doi: 10.1186/s13017-016-0082-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gurusamy KS, Koti R, Fusai G, Davidson BR. Early vs delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy for uncomplicated biliary colic. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013:CD007196. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007196.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Di Saverio S, Podda M, De Simone B, Ceresoli M, Augustin G, Gori A, Boermeester M, Sartelli M, Coccolini F, Tarasconi A, De' Angelis N, Weber DG, Tolonen M, Birindelli A, Biffl W, Moore EE, Kelly M, Soreide K, Kashuk J, Ten Broek R, Gomes CA, Sugrue M, Davies RJ, Damaskos D, Leppäniemi A, Kirkpatrick A, Peitzman AB, Fraga GP, Maier RV, Coimbra R, Chiarugi M, Sganga G, Pisanu A, De' Angelis GL, Tan E, Van Goor H, Pata F, Di Carlo I, Chiara O, Litvin A, Campanile FC, Sakakushev B, Tomadze G, Demetrashvili Z, Latifi R, Abu-Zidan F, Romeo O, Segovia-Lohse H, Baiocchi G, Costa D, Rizoli S, Balogh ZJ, Bendinelli C, Scalea T, Ivatury R, Velmahos G, Andersson R, Kluger Y, Ansaloni L, Catena F. Diagnosis and treatment of acute appendicitis: 2020 update of the WSES Jerusalem guidelines. World J Emerg Surg. 2020;15:27. doi: 10.1186/s13017-020-00306-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wagner M, Tubre DJ, Asensio JA. Evolution and Current Trends in the Management of Acute Appendicitis. Surg Clin North Am. 2018;98:1005–1023. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2018.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Elshove-Bolk J, Mencl F, van Rijswijck BT, Simons MP, van Vugt AB. Validation of the Emergency Severity Index (ESI) in self-referred patients in a European emergency department. Emerg Med J. 2007;24:170–174. doi: 10.1136/emj.2006.039883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Okamoto K, Suzuki K, Takada T, Strasberg SM, Asbun HJ, Endo I, Iwashita Y, Hibi T, Pitt HA, Umezawa A, Asai K, Han HS, Hwang TL, Mori Y, Yoon YS, Huang WS, Belli G, Dervenis C, Yokoe M, Kiriyama S, Itoi T, Jagannath P, Garden OJ, Miura F, Nakamura M, Horiguchi A, Wakabayashi G, Cherqui D, de Santibañes E, Shikata S, Noguchi Y, Ukai T, Higuchi R, Wada K, Honda G, Supe AN, Yoshida M, Mayumi T, Gouma DJ, Deziel DJ, Liau KH, Chen MF, Shibao K, Liu KH, Su CH, Chan ACW, Yoon DS, Choi IS, Jonas E, Chen XP, Fan ST, Ker CG, Giménez ME, Kitano S, Inomata M, Hirata K, Inui K, Sumiyama Y, Yamamoto M. Tokyo Guidelines 2018: flowchart for the management of acute cholecystitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2018;25:55–72. doi: 10.1002/jhbp.516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Friedman GD. Natural history of asymptomatic and symptomatic gallstones. Am J Surg. 1993;165:399–404. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(05)80930-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hirota M, Takada T, Kawarada Y, Nimura Y, Miura F, Hirata K, Mayumi T, Yoshida M, Strasberg S, Pitt H, Gadacz TR, de Santibanes E, Gouma DJ, Solomkin JS, Belghiti J, Neuhaus H, Büchler MW, Fan ST, Ker CG, Padbury RT, Liau KH, Hilvano SC, Belli G, Windsor JA, Dervenis C. Diagnostic criteria and severity assessment of acute cholecystitis: Tokyo Guidelines. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2007;14:78–82. doi: 10.1007/s00534-006-1159-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blecker S, Jones SA, Petrilli CM, Admon AJ, Weerahandi H, Francois F, Horwitz LI. Hospitalizations for Chronic Disease and Acute Conditions in the Time of COVID-19. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181:269–271. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.3978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bickell NA, Aufses AH Jr, Rojas M, Bodian C. How time affects the risk of rupture in appendicitis. J Am Coll Surg. 2006;202:401–406. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2005.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Orthopoulos G, Santone E, Izzo F, Tirabassi M, Pérez-Caraballo AM, Corriveau N, Jabbour N. Increasing incidence of complicated appendicitis during COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Surg. 2021;221:1056–1060. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2020.09.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fisher JC, Tomita SS, Ginsburg HB, Gordon A, Walker D, Kuenzler KA. Increase in Pediatric Perforated Appendicitis in the New York City Metropolitan Region at the Epicenter of the COVID-19 Outbreak. Ann Surg. 2021;273:410–415. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000004426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Willms AG, Oldhafer KJ, Conze S, Thasler WE, von Schassen C, Hauer T, Huber T, Germer CT, Günster S, Bulian DR, Hirche Z, Filser J, Stavrou GA, Reichert M, Malkomes P, Seyfried S, Ludwig T, Hillebrecht HC, Pantelis D, Brunner S, Rost W, Lock JF CAMIN Study Group. Appendicitis during the COVID-19 lockdown: results of a multicenter analysis in Germany. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2021;406:367–375. doi: 10.1007/s00423-021-02090-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Emile SH, Hamid HKS, Khan SM, Davis GN. Rate of Application and Outcome of Non-operative Management of Acute Appendicitis in the Setting of COVID-19: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2021:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s11605-021-04988-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Masroor S. Collateral damage of COVID-19 pandemic: Delayed medical care. J Card Surg. 2020;35:1345–1347. doi: 10.1111/jocs.14638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Garcia S, Albaghdadi MS, Meraj PM, Schmidt C, Garberich R, Jaffer FA, Dixon S, Rade JJ, Tannenbaum M, Chambers J, Huang PP, Henry TD. Reduction in ST-Segment Elevation Cardiac Catheterization Laboratory Activations in the United States During COVID-19 Pandemic. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:2871–2872. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Teo KC, Leung WCY, Wong YK, Liu RKC, Chan AHY, Choi OMY, Kwok WM, Leung KK, Tse MY, Cheung RTF, Tsang AC, Lau KK. Delays in Stroke Onset to Hospital Arrival Time During COVID-19. Stroke. 2020;51:2228–2231. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.030105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Woolf SH, Chapman DA, Sabo RT, Weinberger DM, Hill L. Excess Deaths From COVID-19 and Other Causes, March-April 2020. JAMA. 2020;324:510–513. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.11787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Emergency Physicians. Public Poll: Emergency Care Concerns Amidst COVID-19. [cited 10 February 2021]. Available from: http://www.emergencyphysicians.org/article/covid19/public-poll-emergency-care-concerns-amidst-covid-19 .

- 35.Lopes L, Muñana C. KFF Health Tracking Poll – June 2020 - Coronavirus, Delayed Care and 2020 Election. KFF 2020. [cited 10 February 2021]. Available from: https://www.kff.org/report-section/kff-health-tracking-poll-june-2020-social-distancing-delayed-health-care-and-a-look-ahead-to-the-2020-election/

- 36.University JH. COVID-19 United States Cases by County. [cited 10 February 2021]. Available from: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/us-map .

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Technical appendix, statistical code, and dataset available from the corresponding author at mesquive@stanford.edu. No additional data are available.