Abstract

Objective

The rates of caesarean section (CS) in Ethiopian private hospitals are high compared with those in public facilities, and there are limited descriptions of groups of women contributing to these high rates. The objective of this study was to describe the groups contributing to increased CS rates using the Robson classification in two major private hospitals in eastern Ethiopia.

Design

Cross-sectional study.

Setting

Two major private hospitals in eastern Ethiopia.

Participants

All women who gave birth from 9 January 2019 to 8 January 2020 in two major private hospitals in eastern Ethiopia.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

The primary outcome was the Robson 10 Group Classification System. The secondary outcome was indication for CS as recorded in the medical files.

Results

Of 1203 births in both hospitals combined during the study period, 415 (34.5%) were by CS. Women with a uterine scar due to previous CS (group 5), single cephalic term multiparous women in spontaneous labour (group 3) and single cephalic term nulliparous women in spontaneous labour (group 1) were the leading groups contributing 33%, 27.5% and 17.1%, respectively. The leading documented indications were fetal compromise (29.4%), previous CS (27.2%) and obstructed labour (12.3%).

Conclusion

More than three-fourths of CS were performed among Robson groups 5, 3 and 1, indicating inadequate trial of labour after CS or management of labour among relatively low-risk groups (3 and 1). Improving management of spontaneous labour and strengthening clinical practice around safely providing the option of vaginal birth after CS practice are strategies required to reduce the high CS rates in these private facilities.

Keywords: obstetrics, epidemiology, audit, public health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study to apply the Robson classification to private hospitals in Ethiopia.

Because routinely collected clinical data were used, some sociodemographic variables of interest were missed.

The retrospective nature of the study may be prone to incomplete documentation.

Introduction

Although caesarean section (CS) is a life-saving intervention when vaginal delivery is deemed to be of higher risk for the woman or the newborn, there is no significant improvement in maternal and neonatal health outcomes when the population-based CS rate is higher than 15%.1 2 From being performed to save the life of the woman or the neonate, CS is also being performed for non-absolute indications, such as maternal request or obstructed labour with intact membrane.3 The overall rate of CS in Ethiopia is one of the lowest (0.6%), with huge regional variations.4 Moreover, the rates of CS significantly vary within and among countries, with women from urban areas, literate women and those visiting private facilities having more CS compared with their counterparts.4 5

With the unprecedented rise in CS rates, there is a need to institute a robust system to minimise unnecessary and medically non-indicated CS.6 The risks associated with (repeated) CS for women and newborn are well established.7–9 These range from increased risk of uterine rupture and abnormal placentation in women to stillbirth and iatrogenic preterm birth in babies. Moreover, long-term effects on hormonal, physical, bacterial and physiological conditions and risk of allergic reactions to the newborn have also been reported.9

A recommended system for clinical auditing of CS is the Robson 10 Group Classification System.9–11 Based on obstetric history, course of labour and gestational age, the Robson classification categorises all women undergoing CS into 10 mutually exclusive and exhaustive groups.12–14 Although the Robson classification has been promoted by the WHO as a method to reduce the rates of CS,13 15 16 the system has rarely been applied to private facilities in Africa.17 18

Given the increase in global rates of CS, including in low-income and middle-income countries,2 19–21 and in private facilities in particular, audit of CS practices and identifying groups contributing to CS rates using the Robson classification are important to design appropriate interventions.17 22–26 To the best of our knowledge, no such study has been performed in private facilities in Ethiopia, rendering the contribution of different groups to overall CS rates in these institutions unknown.27 28

The aim of this study was to determine which groups are driving the CS rate in selected major private hospitals in eastern Ethiopia using the Robson 10 Group Classification System.

Methods

Study design and participants

This study was conducted as part of a larger study on maternal near miss and mortality in major private hospitals in eastern Ethiopia, which has been described elsewhere.29 In brief, all women who were admitted from 9 January 2019 to 8 January 2020 in two major private hospitals in eastern Ethiopia during pregnancy, childbirth or within 42 days of termination of pregnancy were identified. Then, all women who fulfilled the adapted sub-Saharan African maternal near miss criteria were identified.30 Finally, data on sociodemographic conditions, reproductive and obstetric factors, and respective feto-maternal outcomes at discharge were collected from those identified as near miss or not (for comparison). The study was retrospectively conducted from 1 February to 29 February 2020 at the department of obstetrics and gynaecology of hospital 1 and hospital 2—the two major private hospitals in Harar and Dire Dawa towns in eastern Ethiopia. As part of this study, data on category of pregnancy, presence of previous uterine scar, course of labour and delivery, and gestational age, which are essential for the Robson classification,12 were collected from all women who gave birth. To enable comparisons, records of women who gave birth vaginally were also reviewed. The identity of all women who visited both hospitals for maternity services was obtained from the admission and discharge registers, delivery logbooks and operation theatre registers. Using their medical registration number, all files were retrieved from the archive rooms at both hospitals and reviewed by research assistants who received dedicated inservice training.

Study setting

Hospital 1 is a general specialised 33-bed private hospital in Harar providing specialised care in internal medicine, surgery, obstetrics and gynaecology, paediatrics and child health, and some other smaller fields. During the study period, five consultants and six midwives were practising at the department of obstetrics. It provides care for both emergency and planned CS by consultants, with approximately 1000 births annually. Hospital 2 is one of the major private hospitals in Dire Dawa with almost 600 deliveries annually. Both hospitals have one major operation theatre which they share with all surgical specialties. Unlike public facilities, where all maternity services are free of charge,31 a typical CS procedure costs 10 000–15 000 Ethiopian birr ($267–400).

Variables

The dependent variable was the Robson classification groups 1–10 based on the category of pregnancy, presence of previous uterine scar, course of labour and delivery, and gestational age of pregnancy (table 1).12 The independent variables included sociodemographic conditions (age, referral status, residence), medical and obstetric history, and conditions present in the index pregnancy.

Table 1.

Robson 10 Group Classification System for caesarean section12

| Group | Description |

| 1 | Nulliparous, single cephalic, ≥37 weeks, in spontaneous labour. |

| 2 | Nulliparous, single cephalic, ≥37 weeks, induced or CS before labour. |

| 3 | Multiparous (excluding previous CS), single cephalic, ≥37 weeks, in spontaneous labour. |

| 4 | Multiparous (excluding previous CS), single cephalic, >37 weeks, induced or CS before labour. |

| 5 | Previous CS, single cephalic, ≥37 weeks. |

| 6 | All nulliparous breeches. |

| 7 | All multiparous breeches (including previous CS). |

| 8 | All multiple pregnancies (including previous CS). |

| 9 | All abnormal lies (including previous CS). |

| 10 | All single cephalic, <37 weeks (including previous CS). |

CS, caesarean section.

Data collection

This study was conducted as part of a larger study on maternal near miss.29 The near miss study was conducted to assess the magnitude of near miss among all women admitted to the department of obstetrics and gynaecology. All women who fulfilled any of the sub-Saharan African maternal near miss criteria were included in the main study.30 Trained research assistants collected data on maternal characteristics (age, parity, antenatal booking, referral status), obstetric and medical history, and conditions (history of uterine scar, history or presence of obstetric complications), labour and delivery-related information (onset, presentation, mode of birth, indication for CS for births by CS), fetal/neonatal information (vital status at birth, fifth minute Apgar score, admission to special intensive care unit, birth weight), presence of maternal near miss events, and maternal and fetal outcome at discharge.

Data processing and analysis

All collected data were cross-checked for completeness and consistency and double-entered to EpiData V.3.1 (http://www.epidata.dk) and exported to Stata V.13 (https://www.stata.com) for analysis. The Robson group was determined using the four basic obstetric concepts and their parameters—pregnancy category, history of CS, course of labour and gestational age.12 In addition, indications reported for CS were classified as absolute and non-absolute indications as per the recommendation of Stanton and Ronsmans.32 Absolute indications included obstructed labour, major antepartum haemorrhage (including placenta previa grades 3 and 4), malpresentation (transverse, oblique and brow presentation) and uterine rupture in hierarchical order. Non-absolute indications included history of CS, fetal compromise, failure to progress (prolonged labour, failed induction), breech presentation, severe pre-eclampsia and eclampsia without hierarchical order.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting or dissemination plans of this research.

Results

During the study period, 1287 maternity admissions were reported. After excluding 73 (5.7%) lost or incomplete files, 1214 records with complete data were reviewed, constituting 1203 births (excluding abortions and laparotomies not resulting in births). A total of 415 births were by CS, making the overall CS rate 34.5% (277 of 839, 33% in hospital A; 138 of 364, 37.9% in hospital B). The mean age of participants was 26.7 (±5.3) years, ranging from 17 to 40 years old. The mean gestational age was 38.9 (±1.6) weeks. The majority of women were married (98.8%), urban residents (70.6%) and self-referred (94.9%). Details of sociodemographic conditions are summarised in table 2.

Table 2.

Sociodemographic conditions of women who underwent CS in selected private hospitals in eastern Ethiopia, 2020

| Variable | Frequency | % |

| Age | ||

| <20 | 37 | 8.9 |

| 20–35 | 356 | 85.8 |

| >35 | 22 | 5.3 |

| Residence | ||

| Urban | 293 | 70.6 |

| Rural | 122 | 29.4 |

| Type of CS | ||

| Elective | 85 | 20.5 |

| Emergency | 350 | 79.5 |

| Referral status | ||

| Self-referral | 394 | 94.9 |

| Referred from other facilities | 21 | 5.1 |

| Antenatal care (at least one) | ||

| Yes | 387 | 93.3 |

| No | 28 | 6.7 |

| Parity | ||

| 0 | 95 | 22.9 |

| 1–4 | 285 | 68.7 |

| >4 | 35 | 8.4 |

| Gestational age (weeks)37 | ||

| Preterm (<37) | 9 | 2.2 |

| Term (37–41 6/7) | 400 | 96.4 |

| Post-term (≥42) | 6 | 1.4 |

| Onset of labour | ||

| Spontaneous | 285 | 68.7 |

| Induced | 24 | 5.8 |

| CS before labour | 106 | 25.5 |

| Fetal presentation | ||

| Cephalic | 393 | 94.7 |

| Breech | 18 | 4.3 |

| Transverse | 4 | 1 |

| Birth weight (g) | ||

| <2500 | 12 | 2.9 |

| 2500–4000 | 393 | 94.7 |

| >4000 | 10 | 2.4 |

CS, caesarean section.

Analysis of the Robson classification

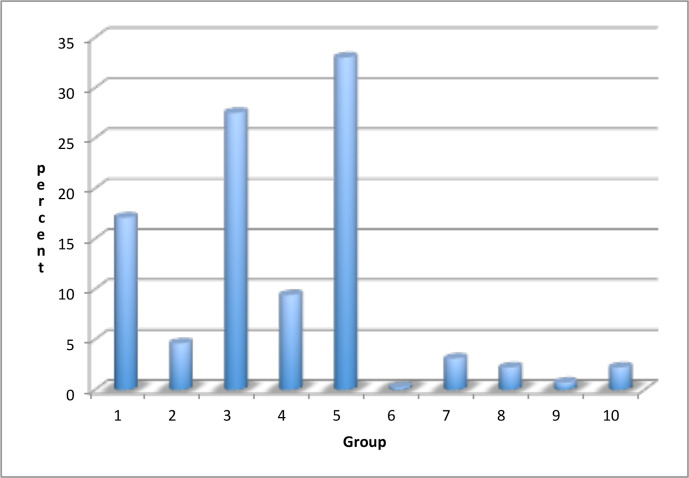

The three leading Robson groups were group 5 (n=137, 33%), group 3 (n=114, 27.5%) and group 1 (n=71, 17.1%). The overall contribution of the ‘high risk groups’ (groups 6, 7, 8 and 9) to the overall CS rate was almost nil (6.2%). Details of the Robson groups and their respective contributions are summarised in figure 1 and table 3.

Figure 1.

Distribution of women undergoing caesarean section according to the Robson groups in selected private hospitals in eastern Ethiopia, 2020.

Table 3.

Distribution of Robson groups and their contribution to the overall CS rate in selected private hospitals in eastern Ethiopia, 2020

| Group | Description | CS/all births in the group | Contribution per group to total births (%) | CS rate within group (%) | Contribution per group to the CS rate (%) |

| 1 | Nulliparous, single cephalic, ≥37 weeks, in spontaneous labour. | 71/197 | 16.4 | 36.0 | 17.1 |

| 2 | Nulliparous, single cephalic, ≥37 weeks, induced or CS before labour. | 19/27 | 2.2 | 70.4 | 4.6 |

| 3 | Multiparous (excluding previous CS), single cephalic, ≥37 weeks, in spontaneous labour. | 114/690 | 57.4 | 16.5 | 27.5 |

| 4 | Multiparous (excluding previous CS), single cephalic, ≥37 weeks, induced or CS before labour. | 39/72 | 6.0 | 54.2 | 9.4 |

| 5 | Previous CS, single cephalic, ≥37 weeks. | 137/153 | 12.7 | 89.5 | 33.0 |

| 6 | All nulliparous breeches. | 1/1 | 0.1 | 100 | 0.24 |

| 7 | All multiparous breeches. | 13/22 | 1.8 | 59.1 | 3.1 |

| 8 | All multiple pregnancies (including previous CS). | 9/15 | 1.2 | 60 | 2.2 |

| 9 | All abnormal lies (including previous CS). | 3/3 | 0.3 | 100 | 0.7 |

| 10 | All single cephalic, ≤36 weeks (including previous CS). | 9/23 | 1.9 | 39.1 | 2.2 |

| Total | 415/1203 | 100 | 34.5 | 100 |

CS, caesarean section.

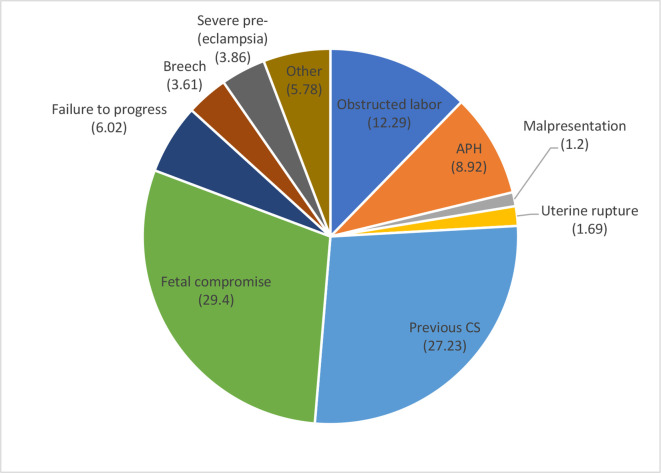

Overall and within-group indication for CS

As indicated in figure 2, the leading indications for performing CS in this study were fetal compromise (29.4%), previous CS (27.2%) and obstructed labour (12.3%). In general, CS was performed for absolute indications in 24.1% only (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Indications for performing CS in selected private hospitals in eastern Ethiopia, 2020. APH, antepartum haemorrhage; CS, caesarean section.

The major indications within each Robson group are summarised in table 4. Except for Robson groups 9 and 10, where malpresentation (n=3/3) and major antepartum haemorrhage (n=5/9) were the leading indications, non-absolute indications were the main indications in all other groups: fetal compromise in group 1 (n=40/71, 56.3%) and group 3 (n=68/114, 59.6%); previous CS in group 5 (n=106/137, 77.4%); and breech presentation in group 6 (n=1/1, 100%), group 7 (n=10/13, 76.9%) and group 8 (n=4/9, 44.4%).

Table 4.

Overall and within Robson group indications for performing CS in selected private hospitals in eastern Ethiopia, 2020

| Indications | Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 | Group 4 | Group 5 | Group 6 | Group 7 | Group 8 | Group 9 | Group 10 | Total |

| Absolute indications | |||||||||||

| Obstructed labour | 19 | 2 | 24 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 51 |

| Major APH | 2 | 1 | 14 | 6 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 37 |

| Malpresentation | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 5 |

| Uterine rupture | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 |

| Non-absolute indications | |||||||||||

| Previous CS | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 106 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 113 |

| Fetal compromise | 40 | 0 | 68 | 4 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 122 |

| Failure to progress | 4 | 6 | 1 | 13 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 25 |

| Breech presentation | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 10 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 15 |

| (Severe pre-eclampsia) eclampsia | 5 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 16 |

| Others | 1 | 8 | 1 | 11 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 24* |

| Total | 71 | 19 | 114 | 39 | 137 | 1 | 13 | 9 | 3 | 9 | 415 |

*18 on maternal requests and 6 unspecified.

APH, antepartum haemorrhage; CS, caesarean section.

Discussion

This study was conducted to describe CS in selected private hospitals using the Robson classification. We found that women with a history of CS in a previous pregnancy (group 5), single cephalic multiparous women at term in spontaneous labour with no history of CS (group 3) and single cephalic nulliparous women at term and in spontaneous labour (group 1) were the leading Robson groups contributing to 8 in 10 CS. In addition, the relatively moderate risk groups (groups 1–4 combined) contributed 58.6% of all CS in the participating private hospitals. The leading recorded indications for performing CS were fetal compromise, previous CS and obstructed labour. Although the application of Robson classification for auditing CS is common practice, to the best of our knowledge this is only the second reported study to apply this classification to private hospitals in a low-income and middle-income country after the study by Begum et al18 in Bangladesh.

Our finding is consistent with a study previously conducted in a public university hospital in the same setting, although in a different order, where groups 3, 5 and 1 were the leading contributors.28 However, the contribution of group 5 in our study is much higher compared with the previous study (33% vs 21.4%). The fact that women with no previous CS (groups 1, 2, 3 and 4) contributed to 6 in 10 (58.6%) and mainly for non-absolute indications—fetal compromise and failure to progress—indicates the need to assess appropriateness of labour management in private settings. Minimising primary CS in these low-risk groups is essential since women with CS scar would often undergo CS.

Looking into the quality of data as per the WHO recommendation13 shows good quality of data. The size of group 9 is in the expected range of <1% (0.3), with an overall CS rate of 100%. In addition, looking into the relative size of the combination of ‘groups 1 and 2’ (18.6%) and ‘groups 3 and 4’ (63.3%) in table 3 (column 3) shows the presence of high multiparous women in the database, as evidenced by high total fertility rate (4.6) in the country.33 It may also reflect high vaginal delivery among women without prior scars. Furthermore, the ratio of ‘group 3 to 4’ is higher than the ratio of ‘group 1 to 2’, indicating good quality of data.13 However, the ratio of ‘group 6 to 7’ was very low (0.05) compared with the expected high breeches among nulliparas compared with multipara. Given the quality of our data is acceptable as indicated by other parameters above, this requires further audit.

Given that groups 5, 3 and 1 constitute large demographic shares, it was expected that these would contribute largely to the overall CS. However, the fact that CS rates within these groups were 89.5%, 16.5% and 36.0%, respectively, indicates vast opportunities to reduce CS rates by strengthening clinical practice around vaginal birth, including vaginal birth after CS. The numbers do raise concerns about quality of care around vaginal birth in private care facilities in Ethiopia. Although group 5 comprised 12.5% of all births, it contributed 33% to the overall CS rate, possibly indicating low utilisation of trial of labour or instrumental vaginal birth. Trial of labour in sub-Saharan Africa in general is low,34 although this practice may be justified in a majority of women with a previous scar if combined with proper labour monitoring.35

Strengths and limitations

This study is the first to apply the Robson classification to major private hospitals in Ethiopia. Inclusion of all women who gave birth in both facilities (CS and vaginal deliveries) during the study period helped us to indicate the Robson distribution as a whole and also among those who had CS without selection bias. However, the study has some limitations to be considered. First, as the data were retrospectively collected from medical records, some important socioeconomic variables which are not routinely documented were missed. Second, data on trial of labour or partograph use are not often documented, making it difficult to comment on management of labour and timeliness of the decisions to undergo CS.

Conclusion

More than three-fourths of CS were performed among Robson groups 5, 3 and 1, indicating inadequate trial of labour after CS or management of labour among relatively low-risk groups (3 and 1). Although the overall CS rate in this study is not as high as those reported in private hospitals in some other clinics, it requires further study since a majority (68%) of women who have undergone CS did not have any underlying obstetric complications.36 In addition, the high CS rate among women with a scarred uterus (89.2%) requires further audit of the obstetric interventions provided to these women. Since these private hospitals are well equipped with fetal monitoring and the ability to perform CS quickly, trial of labour after CS should be attempted and the missed opportunities should be further explored.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We want to thank the hospital managers for allowing us to conduct this study in their respective hospitals.

Footnotes

Contributors: AKT conceived the study and wrote the original draft of the manuscript, which was subsequently reviewed by SG, SGF and TvdA. SG was involved in proposal development and collected data under the supervision and mentorship of AKT. Analysis was done by AKT. SG, SGF and TvdA reviewed the manuscript for intellectual content and participated in the revision. All authors contributed to the writing and reviewed the article and approved the final version of the manuscript to be published.

Funding: SG received a grant from Haramaya University for his MSc study.

Disclaimer: The funding organisation has no role in the design, execution or decision to publish the study.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information. Data essential for conclusion are included in the manuscript. Additional data can be obtained from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the institutional health research ethics review committee of the College of Health and Medical Sciences, Haramaya University, Ethiopia (IHRERC/045/2020).

References

- 1.World Health Organization . World health statistics 2015. World Health Organization, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Betrán AP, Ye J, Moller A-B, et al. The increasing trend in caesarean section rates: global, regional and national estimates: 1990-2014. PLoS One 2016;11:e0148343. 10.1371/journal.pone.0148343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rijken MJ, Meguid T, van den Akker T, et al. Global surgery and the dilemma for obstetricians. Lancet 2015;386:1941–2. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00828-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fesseha N, Getachew A, Hiluf M, et al. A national review of cesarean delivery in Ethiopia. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2011;115:106–11. 10.1016/j.ijgo.2011.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boatin AA, Schlotheuber A, Betran AP, et al. Within country inequalities in caesarean section rates: observational study of 72 low and middle income countries. BMJ 2018;360:k55. 10.1136/bmj.k55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Betrán AP, Merialdi M, Lauer JA, et al. Rates of caesarean section: analysis of global, regional and national estimates. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2007;21:98–113. 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2007.00786.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Keag OE, Norman JE, Stock SJ. Long-term risks and benefits associated with cesarean delivery for mother, baby, and subsequent pregnancies: systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med 2018;15:e1002494. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Masukume G, McCarthy FP, Russell J, et al. Caesarean section delivery and childhood obesity: evidence from the growing up in New Zealand cohort. J Epidemiol Community Health 2019;73:1063–70. 10.1136/jech-2019-212591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sandall J, Tribe RM, Avery L, et al. Short-term and long-term effects of caesarean section on the health of women and children. Lancet 2018;392:1349–57. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31930-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Betrán AP, Vindevoghel N, Souza JP, et al. A systematic review of the robson classification for caesarean section: what works, doesn't work and how to improve it. PLoS One 2014;9:e97769. 10.1371/journal.pone.0097769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Le Ray C, Blondel B, Prunet C, et al. Stabilising the caesarean rate: which target population? BJOG: Int J Obstet Gy 2015;122:690–9. 10.1111/1471-0528.13199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robson MS. Can we reduce the caesarean section rate? Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2001;15:179–94. 10.1053/beog.2000.0156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health Organization . Robson classification: implementation manual, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Robson M. The ten group classification system (TGCS) - a common starting point for more detailed analysis. BJOG: Int J Obstet Gy 2015;122:701. 10.1111/1471-0528.13267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alonso BD, Silva FMBda, Latorre MdoRDdeO, et al. Caesarean birth rates in public and privately funded hospitals: a cross-sectional study. Rev Saude Publica 2017;51:101. 10.11606/S1518-8787.2017051007054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoxha I, Syrogiannouli L, Luta X, et al. Caesarean sections and for-profit status of hospitals: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2017;7:e013670. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Atnurkar KB, Mahale AR. Audit of caesarean section births in small private maternity homes: analysis of 15-year data applying the modified robson criteria, Canada. J Obstet Gynaecol India 2016;66:289–94. 10.1007/s13224-016-0894-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Begum T, Nababan H, Rahman A, et al. Monitoring caesarean births using the Robson ten group classification system: a cross-sectional survey of private for-profit facilities in urban Bangladesh. PLoS One 2019;14:e0220693. 10.1371/journal.pone.0220693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cavallaro FL, Cresswell JA, França GV, et al. Trends in caesarean delivery by country and wealth quintile: cross-sectional surveys in southern Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. Bull World Health Organ 2013;91:914–22. 10.2471/BLT.13.117598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hanson C, Betrán AP, Opondo C, et al. Trends in caesarean section rates between 2007 and 2013 in obstetric risk groups inspired by the robson classification: results from population-based surveys in a low-resource setting. BJOG 2019;126:690–700. 10.1111/1471-0528.15534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harrison MS, Saleem S, Ali S, et al. A prospective, population-based study of trends in operative vaginal delivery compared to cesarean delivery rates in low- and middle-income countries, 2010-2016. Am J Perinatol 2019;36:730–6. 10.1055/s-0038-1673656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chanrachakul B, Herabutya Y, Udomsubpayakul U. Epidemic of cesarean section at the general, private and university hospitals in Thailand. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 2000;26:357–61. 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2000.tb01339.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Phadungkiatwattana P, Tongsakul N. Analyzing the impact of private service on the cesarean section rate in public hospital Thailand. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2011;284:1375–9. 10.1007/s00404-011-1867-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Einarsdóttir K, Haggar F, Pereira G, et al. Role of public and private funding in the rising caesarean section rate: a cohort study. BMJ Open 2013;3:e002789. 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-002789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dahlen HG, Tracy S, Tracy M, et al. Rates of obstetric intervention among low-risk women giving birth in private and public hospitals in NSW: a population-based descriptive study. BMJ Open 2012;2:e001723. 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ali Y, Khan MW, Mumtaz U, et al. Identification of factors influencing the rise of cesarean sections rates in Pakistan, using MCDM. Int J Health Care Qual Assur 2018;31:1058–69. 10.1108/IJHCQA-04-2018-0087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gebremedhin S. Trend and socio-demographic differentials of caesarean section rate in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: analysis based on Ethiopia demographic and health surveys data. Reprod Health 2014;11:14. 10.1186/1742-4755-11-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tura AK, Pijpers O, de Man M, et al. Analysis of caesarean sections using robson 10-group classification system in a university hospital in eastern Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2018;8:e020520. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tenaw SG, Assefa N, Mulatu T, et al. Maternal near miss among women admitted in major private hospitals in eastern Ethiopia: a retrospective study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2021;21:1–9. 10.1186/s12884-021-03677-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tura AK, Stekelenburg J, Scherjon SA, et al. Adaptation of the WHO maternal near miss tool for use in sub-Saharan Africa: an international Delphi study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2017;17:445. 10.1186/s12884-017-1640-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pearson L, Gandhi M, Admasu K, et al. User fees and maternity services in Ethiopia. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2011;115:310–5. 10.1016/j.ijgo.2011.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stanton C, Ronsmans C, Baltimore Group on Cesarean . Recommendations for routine reporting on indications for cesarean delivery in developing countries. Birth 2008;35:204–11. 10.1111/j.1523-536X.2008.00241.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.CSACE I . Ethiopia demographic and health survey 2016. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, and Rockville, Maryland, USA: CSA and ICF, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Boulvain M, Fraser WD, Brisson-Carroll G. Trial of labour after caesarean section in sub-Saharan Africa: ameta-analysis. BJOG:An international journal of O&G 1997;104:1385–90. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1997.tb11008.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van Roosmalen J. Vaginal birth after cesarean section in rural Tanzania. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 1991;34:211–5. 10.1016/0020-7292(91)90351-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bishop D, Dyer RA, Maswime S, et al. Maternal and neonatal outcomes after caesarean delivery in the African surgical outcomes study: a 7-day prospective observational cohort study. Lancet Glob Health 2019;7:e513–22. 10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30036-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.World Health Organization . ICD-10:international statistical classification of diseases and related health problems, 2010: 151–2. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information. Data essential for conclusion are included in the manuscript. Additional data can be obtained from the corresponding author on reasonable request.