Abstract

The protein tyrosine kinase ZAP-70 plays an important role in T-cell activation and development. After T-cell receptor stimulation, ZAP-70 associates with the receptor and is phosphorylated on many tyrosines, including Y292, Y315, and Y319 within interdomain B. Previously, we demonstrated that Y292 negatively regulates ZAP-70 function and that Y315 positively regulates ZAP-70 function by interacting with Vav. Recent studies have suggested that Y319 also positively regulate ZAP-70 function. Paradoxically, removal of interdomain B (to create the construct designated Δ), containing the Y292, Y315, and Y319 sites, did not eliminate the ability of ZAP-70 to induce multiple gene reporters in Syk-deficient DT-40 B cells and ZAP-70/Syk-deficient Jurkat cells. Here we show that Δ still utilizes the same pathways as wild-type ZAP-70 to mediate NF-AT induction. This is manifested by the ability of Δ to restore induction of calcium fluxes and mitogen-activated protein kinase activation and by the ability of dominant negative Ras and FK506 to block the induction of NF-AT activity mediated by Δ. Biochemically we show that the stimulated tyrosine phosphorylation of Vav, Shc, and ZAP-70 itself is diminished, whereas that of Slp-76 is increased in cells reconstituted with Δ. Deletion of interdomain B did not affect the ability of ZAP-70 to bind to the receptor. The in vitro kinase activity of ZAP-70 lacking interdomain B was markedly reduced, but the kinase activity was still required for the protein’s in vivo activity. Based on these data, we concluded that interdomain B regulates but is not required for ZAP-70 signaling function leading to cellular responses.

Stimulation of the T-cell receptor (TCR) and B-cell receptor (BCR) initiates a cascade of signal transduction events involving the activation of two families of protein tyrosine kinases (PTKs), Src PTKs and Syk/ZAP-70 PTKs (2–4, 20, 26). The Src family PTKs initiate these events by phosphorylating the tyrosine residues within the immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motifs (ITAMs) after TCR or BCR stimulation. The Syk/ZAP-70 PTKs are subsequently recruited to the phosphorylated ITAMs, where they become tyrosine phosphorylated and activated. Activation of these kinases further leads to tyrosine phosphorylation of numerous cellular proteins, including phospholipase C-γ isoforms, Vav, Shc, and Slp-76. Tyrosine phosphorylation of phospholipase C-γ induces its enzymatic activation, resulting in the generation of the two second messengers, inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate and diacylglycerol, which are responsible for a rapid and sustained intracellular calcium increase and activation of protein kinase C, respectively (32). These early biochemical events regulate downstream cytokine gene induction and other effector functions.

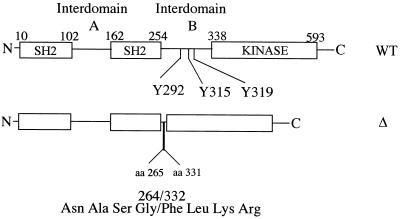

ZAP-70 is a crucial PTK in T-cell activation and development, as has been demonstrated in both humans and in mice lacking ZAP-70 (1, 8, 11, 17, 33). Similarly, a critical role for Syk in B-cell activation and development has been shown both in chicken B cells and in mice made deficient in Syk (9, 22, 24). Like Syk, ZAP-70 is composed of three easily identifiable domains, a tyrosine kinase domain and two tandemly arranged SH2 domains (N terminal and C terminal) which mediate the association of ZAP-70 with the TCR after its stimulation (7, 13, 29). ZAP-70 possesses rather large regions between the two SH2 domains (interdomain A) and between the C-terminal SH2 domain and the kinase domain (interdomain B) (Fig. 1). Interdomain A forms a coiled-coil structure and is likely involved in bringing together the two SH2 domains that bind to receptor ITAMs (12). Although the structure of interdomain B is not available, it contains multiple signaling motifs, including a proline-rich region as well as Y292, Y315, and Y319 that are inducibly phosphorylated (5, 10, 30). Previously we and others have shown that Y292 negatively regulates ZAP-70 function, likely by interacting with an inhibitor (14, 38). Recently, it has been reported that Cbl appears to interact, via a novel phosphotyrosine binding domain, with Y292 of ZAP-70, suggesting that Cbl may mediate the negative regulatory function of Y292 (16). However, the exact biochemical mechanism by which Cbl regulates ZAP-70 function is not clear. We have also shown that Y315 within interdomain B positively regulates ZAP-70 function by recruiting Vav via its SH2 domain (37). In a heterologous reconstitution system, mutation of Y315 has profound effects on ZAP-70 tyrosine phosphorylation and on BCR-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of other substrates, including Vav, Slp-76, and Shc, suggesting that Y315 contributes to multiple aspects of ZAP-70 function (37). Y319 also plays a functional role; mutation of Y319 has been shown to reduce the ability of ZAP-70 to reconstitute NF-AT induction in ZAP-70/Syk-deficient Jurkat cells (32a), and overexpression of a Y319 mutant also inhibits TCR-induced NF-AT induction in wild-type Jurkat cells in a dominant negative (DN) manner, suggesting that Y319 is essential for ZAP-70 function (10). Finally, the proline-rich sequence may also be functionally important. Mutation of the proline-rich sequence enhanced the ability of ZAP-70 to reconstitute NF-AT induction in Syk-deficient DT-40 cells (39). However, the overlap between this proline-rich sequence and the Y292 site may explain the gain-of-function phenotype of the mutation of prolines in this sequence.

FIG. 1.

Schematic representation of WT ZAP-70 and Δ. aa, amino acid.

Here, we extend our studies and show that ZAP-70 lacking interdomain B (Δ) retained its ability to reconstitute the antigen receptor-mediated induction of multiple nuclear factors including NF-AT, AP1, and NF-κB. This is quite surprising since both Y315 and Y319 have been shown to be essential for ZAP-70 function in inducing downstream gene expression. NF-AT induction in cells reconstituted by Δ is still dependent on the calcium- and Ras-dependent pathways since Δ still allows antigen receptor-induced calcium mobilization and mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase activation. Moreover, both FK506 and a DN Ras construct markedly inhibit NF-AT induction in cells reconstituted by Δ. Biochemically, we show that deletion of interdomain B reduces the antigen receptor-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of Vav, Shc, and ZAP-70 itself, whereas it increases that of Slp-76. In addition, deletion of interdomain B does not affect the recruitment of ZAP-70 to the TCR. Surprisingly, the in vitro kinase activity of Δ is much lower than that of wild-type (WT) ZAP-70; however, the kinase activity is still required for its in vivo activity. Based on all of these results, we conclude that interdomain B regulates but is not absolutely required for ZAP-70 function.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

DNA constructs.

The NF-AT luciferase reporter construct was provided by G. Crabtree (Stanford University, Stanford, Calif.). The NF-κB and AP1 reporters have been described previously (21). The Vav plasmid (pCI115) was constructed by subcloning human Vav into PCIneo (Invitrogen, San Diego, Calif.). The parental plasmid is pSXSRαmycZAP-70, kindly provided by L. Samelson (National Institute of Health, Bethesda, Md.). Y292F, Y315F, and Δ constructs were created as described previously (37, 38). Δ+KA was created by subcloning the K369A mutation into the backbone of Δ via the SphI fragment (nucleotides 1286 to 1988). The constructs PapuroZAP-70 and PapuroΔ were created by cloning the R1 fragment containing cDNA for WT ZAP-70 or Δ into an expression vector (Papuro) driven by the chicken actin promoter as described previously (22). The human Shc and Slp-76 cDNAs were provided by M. Gizhizky (Sugen Inc., Redwood City, Calif.) and G. Koretzky (University of Iowa, Iowa City), respectively.

Antibodies.

The monoclonal antibody (MAb) for stimulation of the BCR was M4 (provided by M. Cooper and C. L. Chen, University of Alabama, Birmingham). Anti-Vav polyclonal heteroserum, anti-Shc polyclonal heteroserum, and antiphosphotyrosine MAb 4G10 were purchased from Upstate Biotechnology (Lake Placid, N.Y.). The anti-ZAP-70 MAb was described previously (7). The anti-Myc epitope MAb was provided by J. M. Bishop (University of California, San Francisco). Anti-phospho-MAP kinase polyclonal antibody was purchased from New England Biolabs (Beverly, Mass.).

Cell lines, transfections, and luciferase assays.

WT and mutant DT-40 cells were maintained as described previously (22). Transient transfection for biochemical analyses and for luciferase assays was conducted as described previously (38). For stable transfection, 30 μg of DNA (PapuroZAP-70 or PapuroΔ) was electroporated as described previously (22, 38). Twenty-four hours following electroporation, cells were selected in medium containing 1 μg of puromycin (Sigma) per ml. WT and ZAP-70-/Syk-deficient Jurkat cells were maintained and electroporated as described previously (36).

Calcium fluorimetry.

Cells were loaded with Indo-1, and calcium-sensitive fluorescence was monitored with a Hitachi F4500 fluorescence spectrophotometer at wavelengths 355 and 400. Cells were stimulated with MAb M4 (2 μg/ml). Maximal fluorescence was determined after lysis of the cells with Triton X-100. Minimal fluorescence was obtained after chelation of calcium with EGTA.

Immunoprecipitations and immunoblotting.

Cells were harvested, washed, left unstimulated or stimulated with M4 (2 μg/ml), and then lysed as previously described (22). Lysates were then immunoprecipitated with the indicated antibodies. Resulting immunoprecipitates were resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). Immunoblotting was carried out as previously described (19). The stripping and reprobing of blots were done as previously described (19).

In vitro kinase assay.

After transient transfection, WT and mutant ZAP-70 proteins were immunoprecipitated and in vitro kinase assays were performed as previously described (6). Samples were then analyzed by SDS-PAGE, transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane, treated with 1 M KOH for 1 h, and then subjected to autoradiography.

RESULTS

Δ retains its ability to reconstitute gene expression in Syk/ZAP-70-deficient DT-40 B cells.

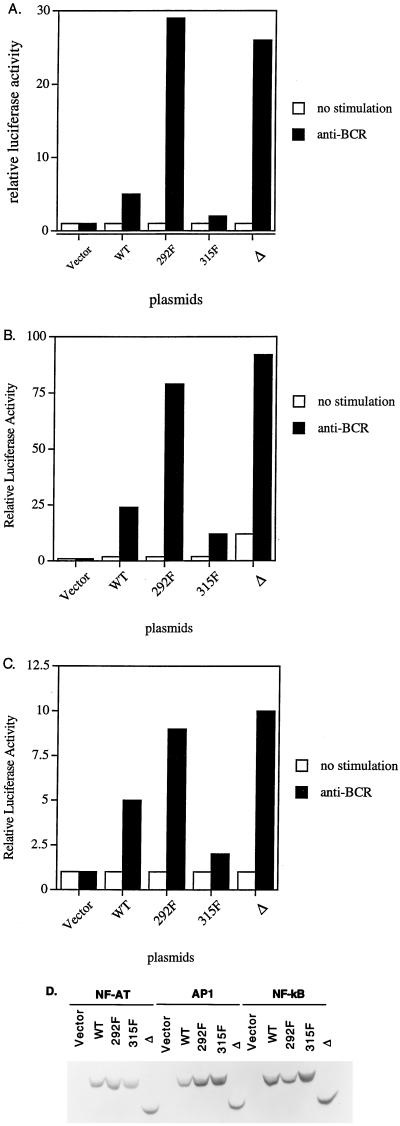

Previously we and others have demonstrated that ZAP-70 can compensate for the defect of Syk in the chicken B-cell line DT-40, as determined by the induction of cellular tyrosine phosphorylation, the mobilization of calcium mobilization, and the induction of gene expression (15, 38). We used this system to show that in interdomain B, Y292 negatively regulates ZAP-70 function whereas Y315 positively regulate ZAP-70 function (37, 38). Mutation of Y292 increased the function of ZAP-70 in BCR-induced downstream gene expression, whereas mutation of Y315 or of Y319 decreased downstream signaling (Fig. 2) (10, 32a). Interestingly, and consistent with our previous report (38), removal of interdomain B (Fig. 1) encompassing these tyrosines resulted in a form of ZAP-70 which still functions to activate the NF-AT transcription reporter (Fig. 2A). Here, we extend those studies to show a similar effect on AP1 and NF-κB induction following BCR stimulation in these cells (Fig. 2B and C). In addition, this deletion mutant allowed BCR induction of the activity of all three reporters to a level similar to that of mutation of Y292 site alone in Syk−/− DT-40 cells. The levels of protein expression for all of these ZAP-70 mutants were comparable (Fig. 2D), as were the responses to stimulation with phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) plus ionomycin in cells transfected with different ZAP-70 plasmids (data not shown). These results indicate that interdomain B of ZAP-70 regulates, but is not required for, its functional activity in the pathways leading to activation of all three reporter systems.

FIG. 2.

Δ retains its function in BCR-mediated signaling. Syk-deficient DT-40 B cells were transiently cotransfected with 20 μg of NF-AT-luc (A), AP1-luc (B), or NF-κB-luc (C) and 15 μg of empty vector, WT ZAP-70, Y292F, Y315F, or Δ. Cells were left unstimulated or stimulated with either anti-BCR or PMA plus ionomycin for 6 to 8 h and subsequently assayed for luciferase activity. The results are shown as fold induction of luciferase activity compared with the activity in unstimulated cells transfected with vector, which is about 200 arbitrary units. Luciferase activity was determined in triplicate in each experimental condition. The data represent at least three independent experiments. (D) Anti-ZAP-70 blot of equivalent amounts of lysates from different transfectants in the luciferase assay described above.

BCR-mediated NF-AT induction in cells reconstituted by Δ is mediated by calcium- and Ras-dependent pathways.

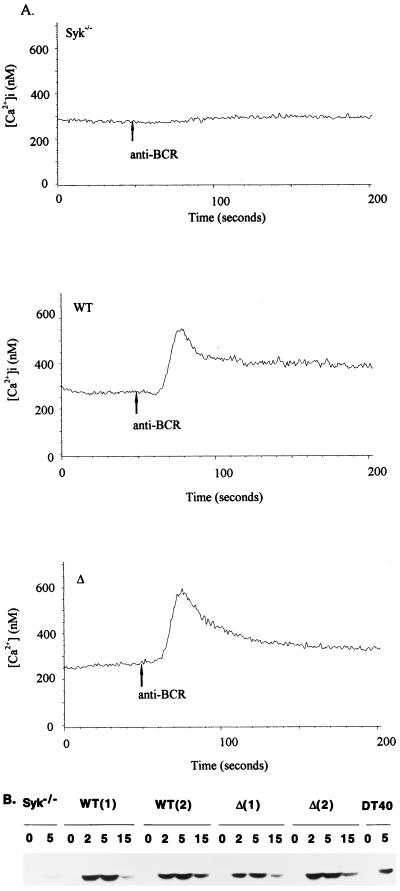

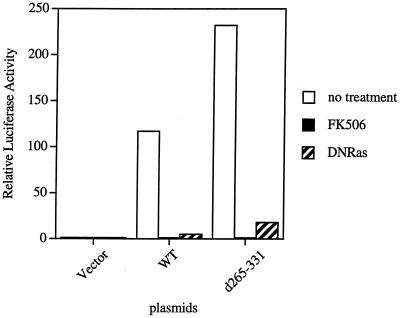

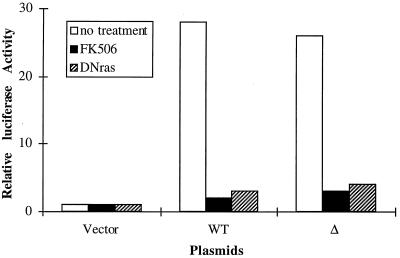

NF-AT induction has been used as an established marker of antigen receptor-mediated activation of T and B cells. The minimum signaling requirements for NF-AT induction are activation of both the Ras and calcium-dependent-calcineurin pathways (34). As shown in Fig. 2, Δ retained the ability to restore BCR induction of NF-AT activity. To determine whether NF-AT induction reconstituted by this mutant is also mediated by calcium- and Ras-dependent pathways, we established stable Syk-deficient DT-40 cell clones reconstituted with WT ZAP-70 and Δ. All of these stable clones have comparable expression of surface BCR and ZAP-70 proteins (data not shown). First we examined whether BCR stimulation in cells reconstituted with Δ can induce calcium mobilization and activate MAP kinase. Note that DT-40 B cells express only Erk-1 MAP kinase, and the activated form could be detected with human anti-phospho-MAP kinase antibody. BCR-mediated calcium responses (Fig. 3A) and MAP kinase activation (Fig. 3B) were induced to comparable extents in WT ZAP-70- and Δ-expressing cells. To further determine whether calcium- and Ras-dependent pathways are required for NF-AT induction in cells reconstituted with Δ, we examined whether this NF-AT induction can be blocked either by FK506 or by DN Ras (Ras N17 mutant). NF-AT induction in Δ-reconstituted cells was blocked by these agents (Fig. 4). Collectively, these results indicate that NF-AT induction in Δ-reconstituted cells is mediated by normal signaling pathways, i.e., the calcium- and Ras-dependent signaling cascades. Therefore, it is unlikely that aberrant signaling pathways are activated in cells reconstituted with Δ to induce NF-AT activity after BCR stimulation.

FIG. 3.

(A) Δ reconstitutes BCR-mediated calcium mobilization. Syk-deficient cells, or Syk-deficient cells stably transfected with WT ZAP-70 and Δ, were loaded with Indo-1 and stimulated with anti-BCR MAb M4 as described in Materials and Methods. [Ca2+]i, intracellular Ca2+ concentration. (B) Δ reconstitutes BCR-mediated MAP kinase activation. WT DT-40 B cells, Syk-deficient DT-40 B cells, or Syk-deficient DT-40 B cells stably transfected with WT ZAP-70 or Δ were either left unstimulated or stimulated with anti-BCR for the lengths of time (in minutes) indicated above the lanes. The cell lysates from equivalent number of cells were subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by blotting with anti-phospho-MAP kinase antibody. The levels of protein expression of endogenous Erk-1 are comparable among samples (not shown). Numbers in parentheses denote separate clones.

FIG. 4.

NF-AT induction mediated by Δ can be blocked by FK506 and DN Ras. A control vector or DN Ras (Ras N17) was transfected into Syk-deficient DT-40 cells, or Syk-deficient DT-40 B cells stably transfected with WT ZAP-70 or Δ, along with NF-AT-luc. The transfected cells were stimulated with anti-BCR and assayed for luciferase activity. Both cell types were transfected with NF-AT-luc, stimulated with anti-BCR in the presence or absence of FK506, and assayed for luciferase activity. Relative luciferase activities were determined and presented as in Fig. 1. The data shown are representative of at least three independent experiments. d285-331 represents the same plasmid as Δ represents in the other figures.

Deletion of interdomain B in ZAP-70 markedly decreases the BCR-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of Vav, Shc, and ZAP-70 itself but increases that of Slp-76.

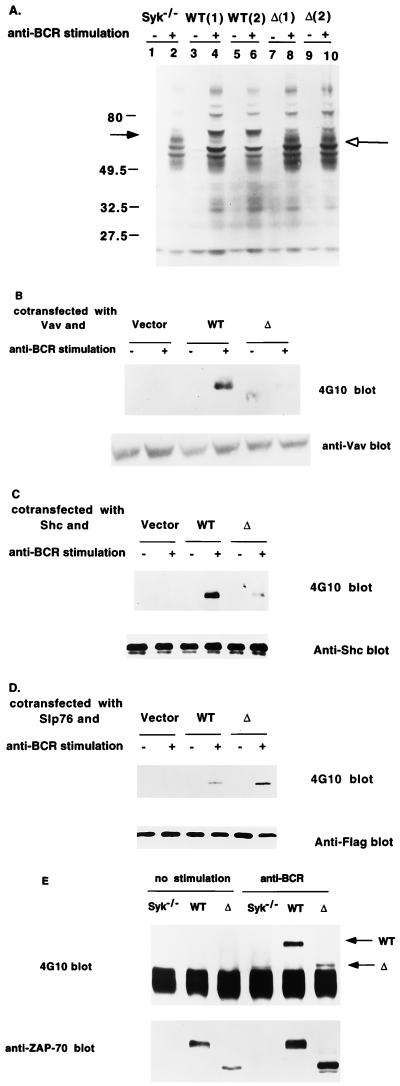

To determine whether Δ has altered ability to phosphorylate downstream substrates, we examined the ability of BCR stimulation to induce protein tyrosine phosphorylation in lysates from Syk−/− cells or from Syk−/− cell clones stably transfected with WT ZAP-70 or Δ. As previously reported, BCR stimulation of Syk-deficient DT-40 cells induced only a few cellular tyrosine phosphoproteins (Fig. 5A, lane 1 and 2). Expression of ZAP-70 in these cells increased the ability of the BCR to induce a number of cellular tyrosine phosphoproteins (Fig. 5A, lanes 3 to 6). Expression of Δ in these cells did not change the gross pattern of BCR-inducible cellular tyrosine phosphoproteins compared with WT ZAP-70 (Fig. 5A; compare lanes 4 and 6 with lanes 8 and 10). We examined whether deletion of interdomain B altered the ability of ZAP-70 to contribute to the phosphorylation of individual substrates. To test whether Δ affects the tyrosine phosphorylation of Vav, we transiently coexpressed human Vav with empty vector, WT ZAP-70, or Δ into Lyn/Syk-deficient DT-40 cells, in which BCR-induced Vav phosphorylation was completely absent (23) (Fig. 5B). Coexpression of Vav with WT ZAP-70 led to tyrosine phosphorylation of Vav following BCR stimulation. However, coexpression of Vav with Δ resulted in much reduced phosphorylation of Vav following BCR stimulation. This result is consistent with our previous studies showing that Y315 within the interdomain B is required for Vav phosphorylation. We also showed that glutathione S-transferase–Vav SH2 did not bind to Δ whereas WT ZAP-70 retains its binding function (data not shown), consistent with the notion that deletion of interdomain B does not create a new Vav binding site in ZAP-70. To further determine the impact of deletion of interdomain B on ZAP-70-mediated tyrosine phosphorylation of other downstream substrates, we analyzed the tyrosine phosphorylation of Slp-76 and Shc. Coexpression of WT ZAP-70 with Shc in Syk-deficient DT40 cells resulted in BCR stimulation-dependent tyrosine phosphorylation of Shc (Fig. 5C). However, coexpression of Δ with Shc resulted in marked reduction of Shc tyrosine phosphorylation. Interestingly, in contrast to Vav and Shc, coexpression of Δ with Slp-76 led to an increase in the BCR-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of Slp-76 in comparison with that induced in cells reconstituted by WT ZAP-70 (Fig. 5D). This is consistent with the notion that Slp-76 is a direct substrate and/or effector of ZAP-70 (31). To examine the effect of deletion of interdomain B upon the tyrosine phosphorylation of ZAP-70 itself, we performed an antiphosphotyrosine blotting analysis of the immunoprecipitates of WT ZAP-70 and Δ. Deletion of interdomain B markedly decreased the BCR-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of ZAP-70 (Fig. 5E). This is an expected result since it removes multiple tyrosine sites (Y292, Y315, and Y319). However, it is interesting that this form of ZAP-70, with an increased ability to restore BCR induction of NF-AT activity, was tyrosine phosphorylated to a lesser extent than WT ZAP-70.

FIG. 5.

Tyrosine phosphorylation of downstream substrates mediated by Δ following BCR stimulation. (A) Reconstitution of BCR-mediated tyrosine phosphorylation by WT ZAP-70 or Δ. Syk-deficient DT-40 B cells, two clones expressing either ZAP-70 or Δ, were stimulated with anti-BCR for 2 min, and cell lysates were analyzed by Western blotting with antiphosphotyrosine MAb 4G10. Molecular size markers are designated on the left in kilodaltons. The closed arrow indicates the transfected WT-ZAP-70; the open arrow indicates the transfected Δ. (B) Vav tyrosine phosphorylation is markedly reduced in cells transfected with Δ. Lyn/Syk-deficient DT-40 cells were transiently cotransfected with Myc-Vav and either an empty vector, WT ZAP-70, or Δ. Cells were either left unstimulated or stimulated with anti-BCR MAb M4 for 2 min. Lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-Myc MAb 9E10, and the immune complex was blotted with 4G10 (top). The blots were then stripped and reblotted with anti-Vav polyclonal antibody b (bottom). The levels of protein expression for WT ZAP-70 and Δ were comparable (not shown). (C) Shc tyrosine phosphorylation is reduced in cells transfected with Δ. Syk-deficient DT-40 B cells, or Syk-deficient DT-40 B cells stably expressing WT ZAP-70 or Δ, were transfected with Shc cDNA. Cells were stimulated and lysed as described for panel A. The lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-Shc MAb, and the immune complex was blotted with 4G10 (top). The blot was then stripped and reblotted with polyclonal anti-Shc antibody (bottom). Anti-ZAP-70 Western blotting showed equivalent expression between WT ZAP-70 and Δ (not shown). (D) Slp-76 tyrosine phosphorylation is increased in cells transfected with Δ following BCR stimulation. Syk-deficient cells, or Syk-deficient cells stably expressing WT ZAP-70 or Δ, were transfected with FLAG epitope-tagged human Slp-76. Cells were stimulated and lysed as described for panel A. The lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG epitope antibody M2, and the immune complex were blotted with 4G10 (top). The blot was then stripped and reprobed with anti-FLAG antibody (bottom). The anti-ZAP-70 Western blot revealed equivalent expression between WT ZAP-70 and Δ. (E) Induction of tyrosine phosphorylation of WT ZAP-70 and Δ. Syk-deficient DT-40 B cells, or cells stably transfected with WT ZAP-70 or Δ, were stimulated with anti-BCR MAb M4, and ZAP-70 immunoprecipitates were analyzed with 4G10. The blot was then stripped and reprobed with anti-ZAP-70 MAb (lower panel).

Deletion of interdomain B in ZAP-70 does not affect its binding to the TCR but markedly reduces its in vitro kinase activity.

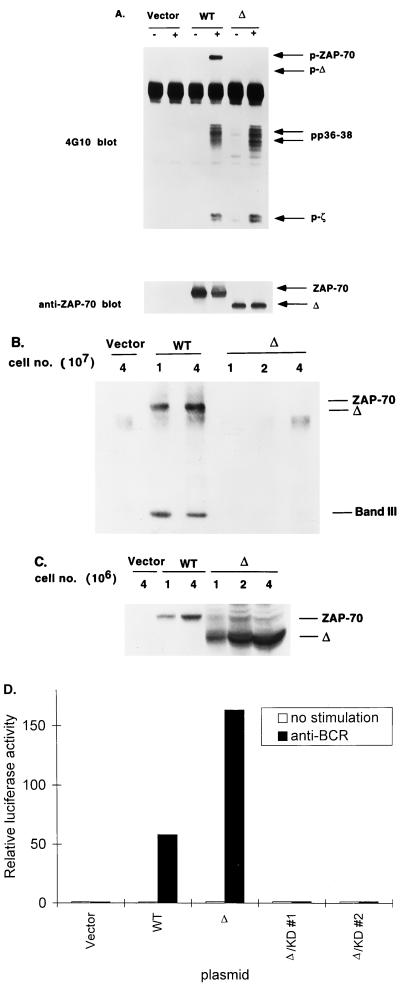

Following TCR stimulation, ZAP-70 is recruited to the receptor complex via its interaction with ITAMs, a step critical for ZAP-70 activation. Therefore, one possible mechanism by which interdomain B affects ZAP-70 function is to affect the relative accessibility of ZAP-70 to the receptor. We examined this possibility by using recently described ZAP-70/Syk-deficient Jurkat cells (P116). We used an antiphosphotyrosine antibody to blot anti-Myc immunoprecipitates from lysates of P116 cells transfected with Myc epitope-tagged WT ZAP-70 or Δ. No difference in binding to tyrosine-phosphorylated TCR ζ chain, either in the basal state or after TCR stimulation, was observed (Fig. 6A). Consistent with the data shown in Fig. 5A, we detected markedly less tyrosine phosphorylation of Δ than of WT ZAP-70 in P116 cells transfected with these constructs. The levels of protein expression of WT ZAP-70 and Δ were comparable (lower panel). Note that deletion of interdomain B did not affect the ability of ZAP-70 to associate with pp36-38 following TCR stimulation (double arrow in upper panel).

FIG. 6.

(A) Deletion of interdomain B in ZAP-70 does not affect the protein’s ability to interact with TCR. ZAP-70/Syk-deficient Jurkat cells were transfected with 30 μg of vector, Myc-WT ZAP-70, or Myc-Δ. Transfected cells were either left unstimulated or stimulated with anti-TCR MAb C305 for 2 min. Cells were lysed and immunoprecipitated with anti-Myc MAb 9E10. The immunoprecipitates were blotted with 4G10 (top). The blot were then stripped and reblotted with anti-ZAP-70 antibody (bottom). (B) Deletion of interdomain B in ZAP-70 markedly reduces the protein’s intrinsic kinase activity. Lyn/Syk-deficient cells were transiently transfected with either an empty vector, Myc-WT ZAP-70 or Myc-Δ. Lysates from transfected cells were immunoprecipitated with anti-Myc antibody 9E10 and subjected to an in vitro kinase assay as described in Materials and Methods. The in vitro-phosphorylated proteins were detected by autoradiography (top). An aliquot of the same lysates from cells transfected with Myc-WT ZAP-70 or Myc-Δ was used to detect levels of protein expression between WT ZAP-70 and Δ (C). (D) The kinase activity is still required for the function of Δ. Syk−/− DT-40 cells were transiently transfected with 15 μg of NF-AT luciferase plasmid with 15 μg of vector, WT ZAP-70, Δ, or Δ/KD (two clones). Cells were either left untreated or stimulated as described for Fig. 2. The data, shown as described for Fig. 2, represent at least three independent experiments.

To examine whether deletion of interdomain B affected the kinase activity of ZAP-70, Myc epitope-tagged WT ZAP-70 or Δ was expressed in Syk/Lyn-deficient DT-40 cells, and then the in vitro kinase activity of anti-Myc epitope-tagged immunoprecipitates was measured as both autophosphorylation and phosphorylation of an exogenous substrate, erythrocyte band III. We used Lyn/Syk-deficient DT-40 cells to express these ZAP-70 proteins because doing so avoided the potential problem of coimmunoprecipitating Src family PTKs in the kinase assays. As shown in Fig. 6B, compared with WT ZAP-70, Δ exhibited a marked reduction in basal kinase activity toward itself and band III. Δ also had a great reduction in BCR-induced kinase activity toward itself and band III (data not shown). These data indicate that deletion of interdomain B greatly reduced autophosphorylation and the kinase activity toward band III in vitro. To examine whether the kinase activity of ZAP-70 is required for the function of Δ in vivo, we introduced a point mutation in the ATP binding site of Δ and transfected this construct into Syk−/− DT-40 cells to examine the induction of NF-AT activity by this double mutant. As shown in Fig. 6D, a point mutation in the ATP binding site of Δ eliminated its ability to reconstitute NF-AT induction in Syk−/− DT-40 cells. This result indicates that the kinase activity is still required for the function of Δ.

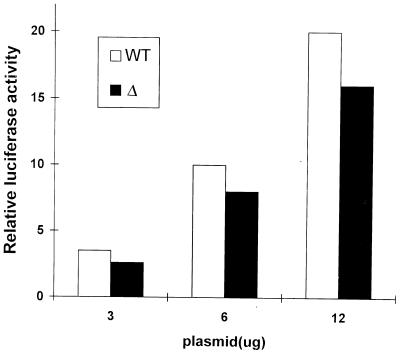

Δ retains the ability to reconstitute NF-AT induction in ZAP-70/Syk-deficient Jurkat cells.

So far, we have analyzed the functional and biochemical consequences of Δ in Syk/ZAP-70-deficient DT-40 B cells. To determine whether deletion of interdomain B also manifested similar effects in Jurkat T cells, we used recently described ZAP-70/Syk-deficient Jurkat cells. Coexpression of WT ZAP-70 or Δ with the NF-AT reporter demonstrated that Δ still retains its ability to reconstitute NF-AT induction in a dose-dependent manner following TCR stimulation. This result indicates that interdomain B is not absolutely required for the function of ZAP-70 in either B- or T-cell antigen receptor systems.

TCR-mediated NF-AT induction in ZAP-70/Syk-deficient Jurkat T cells reconstituted by Δ is mediated by calcium- and Ras-dependent signaling pathways.

The minimum signaling requirements for NF-AT induction are activation of both the Ras-dependent and calcium-dependent calcineurin pathways. As shown in Fig. 7, Δ retained the ability to restore TCR induction of NF-AT activity in ZAP-70/Syk-deficient Jurkat T cells. To determine whether calcium- and Ras-dependent pathways are required for NF-AT induction in these cells reconstituted with Δ, we examined whether this NF-AT induction can be blocked either by FK506 (inhibiting calcineurin) or by DN Ras (Ras N17 mutant). NF-AT induction in Δ-reconstituted ZAP-70/Syk-deficient Jurkat T cells was blocked by these agents (Fig. 8), similar to the result for Δ-reconstituted Syk/ZAP-70-deficient DT-40 B cells (Fig. 4). Taken together, these results indicate that NF-AT induction in both Δ-reconstituted ZAP-70/Syk-deficient Jurkat T cells and Δ-reconstituted Syk/ZAP-70-deficient DT-40 B cells is mediated by normal signaling pathways, i.e., the calcium- and Ras-dependent signaling cascades. Therefore, it is unlikely that aberrant signaling pathways are activated to induce NF-AT activity following TCR or BCR stimulation in cells reconstituted with Δ.

FIG. 7.

Δ retains the ability to reconstitute NF-AT induction in ZAP-70/Syk-deficient Jurkat cells. ZAP-70/Syk-deficient Jurkat cells (P116) were transiently transfected with 15 μg of NF-AT-luc along with different amounts of WT ZAP-70 or Δ. Cells were left unstimulated or stimulated with either anti-TCR antibody C305 or PMA plus ionomycin for 6 to 8 h and subsequently assayed for luciferase activity. Only shown are data for C305-stimulated luciferase activity. Relative luciferase activities, determined and presented as in Fig. 1, represent at least three independent experiments. The levels of protein expression for WT ZAP-70 and Δ were comparable (not shown).

FIG. 8.

NF-AT induction in Δ-reconstituted ZAP-70/Syk-deficient Jurkat T cells can be blocked by FK506 and DN Ras. For FK506 inhibition assay, 15 μg of control vector, WT ZAP-70, or Δ was cotransfected with 15 μg of NF-AT-luc plasmid into ZAP-70/Syk-deficient Jurkat T cells. Twenty-four hours later, the transfected cells were stimulated with anti-TCR MAb C305 in the presence or absence of FK506 and assayed for luciferase activity. Only shown are data for C305-stimulated luciferase activity. For the DN Ras inhibition assay, 15 μg of a control vector, or DN Ras, and 15 μg of a control vector, WT ZAP-70, or Δ were cotransfected into ZAP-70/Syk-deficient Jurkat T cells along with 15 μg of NF-AT luciferase. The transfected cells were stimulated with C305 and assayed for luciferase activity. Only shown are data for C305-stimulated luciferase activity. Relative luciferase activities, determined and presented as in Fig. 1, represent at least three independent experiments. The levels of protein expression for WT ZAP-70 and Δ were comparable (not shown).

DISCUSSION

Previously, we demonstrated that Y292 within interdomain B plays a negative role in regulating ZAP-70 function (38), whereas Y315 plays a positive role in regulating its function (37). Recently it has been shown that Y319 within interdomain B also has an important positive regulatory function (10, 32a). Here, we have demonstrated that deletion of the interdomain B resulted in a form of ZAP-70 which still functions in BCR induction of multiple downstream transcription reporters including NF-AT, AP1, and NF-κB. In addition, this mutant allowed BCR induction of the activity of all three reporters to a level similar to that of cells reconstituted with ZAP-70 containing mutation of Y292 site alone in Syk−/− DT-40 cells. We further demonstrated that this mutant (Δ) participated in the same pathways as WT ZAP-70 to activate NF-AT (Fig. 3, 4, and 8), arguing against the possibility that some aberrant pathways had been unmasked by Δ. Biochemically we showed that Δ mediated reduced tyrosine phosphorylation of Vav, Shc, and itself while it increased that of Slp-76, suggesting that interdomain B plays a complex role in regulating ZAP-70 function. In addition, deletion of interdomain B did not affect the accessibility of ZAP-70 to the TCR, although it markedly reduced the in vitro kinase activity of ZAP-70 toward itself (autophosphorylation) and toward exogenous substrate band III. All of these results suggest that interdomain B regulates but is not required for ZAP-70 function.

One current model for ZAP-70 activation in T-cell lines and clones is that TCR stimulation induces tyrosine phosphorylation of the receptor ITAMs which is mediated by the Lck Src family PTK (32). ZAP-70 is activated after its recruitment to the phosphorylated ITAMs and its subsequent tyrosine phosphorylation. The association of ZAP-70 with the tyrosine-phosphorylated ITAMs is critical but not sufficient for activating ZAP-70 (15, 25, 28). TCR stimulation induces the tyrosine phosphorylation of ZAP-70 and its activation via an Lck-dependent mechanism. Tyrosine phosphorylation of ZAP-70 may serve two purposes. First, tyrosine phosphorylation of ZAP-70 may provide one mechanism for its catalytic activation. Phosphorylation of Y493 and Y492 within the kinase domain has been shown to positively and negatively, respectively, regulate its catalytic activity (5, 27). These residues are predicted to be in the activation loop of the ZAP-70 kinase domain. Second, tyrosine-phosphorylated tyrosine residues in ZAP-70 may serve as binding sites for the recruitment of other regulators and effectors (18).

Multiple tyrosine phosphorylation sites (Y292, Y315, and Y319) within interdomain B regulate ZAP-70 function (5, 10, 30). We and others have previously demonstrated that mutation of Y292 to phenylalanine or glutamic acid enhances ZAP-70 function in BCR or TCR induction of NF-AT activity in either Syk/ZAP-70-deficient DT-40 B cells or TAg-Jurkat cells (14, 38). Mutation of Y292 does not affect the kinase activity of ZAP-70 or its ability to bind to the TCR. These results suggest that Y292 may recruit a negative regulator to downregulate ZAP-70 function. Recently, Lupher et al. have used a heterologous system to show that the Cbl–ZAP-70 interaction can be disrupted by mutation of Y292 to phenylalanine, which suggests that Cbl may mediate the negative regulatory function of Y292 (16). Indeed, an N-terminal phosphotyrosine binding domain was shown to be able to interact in vitro with Y292 in ZAP-70. However, the exact mechanism by which Cbl functions to regulate ZAP-70 function remains to be defined. We have also shown that Y315 has a positive regulatory function in ZAP-70. Mutation of Y315 significantly reduced the ability of ZAP-70 to reconstitute BCR-induced NF-AT induction in Syk-deficient DT-40 B cells. This mutation also eliminated binding of the Vav SH2 domain to ZAP-70 and markedly reduced tyrosine phosphorylation of Vav. In addition, mutation of Y315 reduced BCR-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of Vav, Slp-76, Shc, and ZAP-70 itself, suggesting that Y315 mutation affects multiple aspects of ZAP-70 signaling (37). Our studies with Δ are consistent with the effects of Y315F on tyrosine phosphorylation of Vav and Shc. Recently, it was shown that Y319 is also essential for ZAP-70 function; mutation of Y319 significantly reduces the ability of ZAP-70 to reconstitute Syk/ZAP-70-deficient Jurkat cells and functions as a DN mutation when overexpressed in wild-type Jurkat cells (10, 32a). All of these data indicate that within interdomain B, multiple tyrosines play different roles, presumably by interacting with different proteins, to regulate ZAP-70 function.

Paradoxically, ZAP-70 lacking interdomain B encompassing Y292, Y315, and Y319 still retained the ability of ZAP-70 to reconstitute BCR or TCR induction of multiple transcriptional reporters in Syk-deficient DT-40 cells and in ZAP-70/Syk-deficient Jurkat cells. This is an intriguing result considering this deletion removes one negative regulatory site (Y292) and two positive regulatory sites (Y315 and Y319). The minimum signaling requirements for NF-AT induction are activation of the Ras pathway leading to MAP kinase activation and mobilization of calcium leading to calcineurin activation. To determine whether these signaling pathways are still used by Δ to mediate the antigen receptor induction of NF-AT, we conducted two types of experiments. First, we showed that cells transfected with Δ still mobilize calcium and activate MAP kinase as well as WT ZAP-70 (Fig. 3). Second, we showed that NF-AT induction mediated by Δ can be blocked by a pharmacological inhibitor of calcineurin (FK506) and by a DN mutant of Ras (inhibiting Ras activation) (Fig. 4 and 8). Therefore, it is unlikely that aberrant signaling pathways have been unmasked by Δ to activate NF-AT following TCR or BCR stimulation. Like the Y315F mutant we previously reported, Δ mediated reduced phosphorylation of Vav and Shc, consistent with the notion that Y315 within the interdomain B is required for Vav recruitment and phosphorylation. In contrast, we consistently detected an increased tyrosine phosphorylation of Slp-76 by Δ, compared with WT, consistent with the notion that Slp-76 is a direct substrate/effector of ZAP-70 (31). Although it has been shown that Slp-76 can associate with Vav, it appears that Vav–Slp-76 complex formation is independent of Vav–ZAP-70 complex formation (35). It is therefore likely that Slp-76 is tyrosine phosphorylated by ZAP-70 through mechanisms that do not depend on Y315 or any other residues within interdomain B.

Δ enhances the ability of ZAP-70 to reconstitute BCR stimulation-dependent NF-AT induction in Syk-deficient DT-40 cells. However, it is not more active than WT ZAP-70 in Syk/ZAP-70-deficient Jurkat cells in its ability to reconstitute NF-AT induction in these cells. The difference in the effect of Δ in these two cell types is not clear. The cell context difference observed might be due to the relative abundance levels of other signaling molecules.

One possible mechanism by which interdomain B could function to regulate ZAP-70 is by affecting the interaction of ZAP-70 with the TCR. We provided evidence to argue against this possibility by showing that WT ZAP-70 and Δ have comparable abilities to bind to the TCR ζ chain in the basal state or after TCR stimulation (Fig. 6A). Another possibility is that interdomain B affects the kinase activity of ZAP-70. As shown in Fig. 6B, we detected a much lower in vitro kinase activity of Δ than of WT ZAP-70 in the basal state or following BCR stimulation (data not shown). This is surprising, especially considering that Δ has the ability, comparable to that of WT ZAP-70, to induce expression of multiple downstream reporters following TCR and BCR stimulation (Fig. 2 and 7). To determine whether the kinase activity of ZAP-70 is required for the function of Δ, we tested the function of a double mutant combining Δ and K369A, in which the ATP binding site was mutated. As shown in Fig. 6C, introduction of a point mutation of ATP binding site into Δ eliminated the ability of Δ to reconstitute NF-AT induction in Syk−/− DT-40 cells, indicating that the kinase activity is still required for the function of Δ. Thus, the reduction of in vitro kinase activity does not reflect the kinase-dependent functions of Δ in vivo.

We propose at least two models to explain how interdomain B functions to regulate ZAP-70 function. First, individual tyrosines (Y292, Y315, and Y319) within interdomain B interact with proteins which mediate either negative or positive regulatory function of ZAP-70. These sites may serve to fine-tune ZAP-70 function. Y292 may interact with Cbl to negatively regulate NF-AT induction. Y315 and Y319 may interact with Vav and other proteins to positively regulate NF-AT induction. Perturbing these tyrosines by mutation of either the negative or positive regulatory site results in the delivery of too much or too little signal. However, deleting the entire interdomain B removes both the positive and negative tyrosine sites and renders ZAP-70 capable of participating in antigen receptor signaling function. The elaboration of ZAP-70 signaling by the addition of positive and negative elements may provide an important mechanism whereby the delivery of the signal to trigger T-cell activation can be modulated in a more precise manner. This level of precision may not be appreciated in the conditions used in other studies. As an alternative model, interdomain B may interact with other parts of ZAP-70 in a conformation that inhibits its function. Antigen receptor stimulation may serve to open up the molecule (or suppress the inhibited conformation), leading to activation of ZAP-70. Thus, deletion of interdomain B keeps ZAP-70 in an uninhibited conformation to potentiate its function. This might lead to an increased ability of ZAP-70 to induce activation of downstream signaling events. This is especially true in Syk−/− DT-40 cells. These two models are not mutually exclusive. The binding of proteins to the tyrosines within the interdomain region following antigen receptor stimulation could contribute to uninhibited conformation of ZAP-70. Needless to say, further definition of the function of interdomain B in ZAP-70 awaits structural studies of the intact molecule.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Tomohiro Kurosaki, Chen lo Chen, and Max Cooper for providing cell lines. We thank members of Weiss laboratory for helpful discussion and critically reading the manuscript.

Q.Z. is an associate of and A.W. is an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arpaia E, Shahar M, Dadi H, Cohen A, Roifman C M. Defective T cell receptor signaling and CD8+ thymic selection in humans lacking ZAP-70 kinase. Cell. 1994;76:947–958. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90368-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bolen J B. Protein tyrosine kinase in the initiation of antigen receptor signaling. Curr Opin Immunol. 1995;7:306–331. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(95)80103-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cambier J C, Pleiman C M, Clark M R. Signal transduction by the B cell antigen receptor and its coreceptors. Annu Rev Immunol. 1994;12:457–486. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.12.040194.002325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chan A C, Shaw A S. Regulation of antigen receptor signal transduction by protein tyrosine kinases. Curr Opin Immunol. 1995;8:394–401. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(96)80130-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chan A C, Dalton M, Johnson R, Kong G-H, Wang T, Thoma R, Kurosaki T. Activation of ZAP-70 kinase activity by phosphorylation of tyrosine 493 is required for lymphocyte antigen receptor function. EMBO J. 1995;14:2499–2508. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07247.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chan A C, Irving B A, Fraser J D, Weiss A. The ζ-chain is associated with a tyrosine kinase and upon T cell antigen receptor stimulation associates with ZAP-70, a 70 kilodalton tyrosine phosphoprotein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:9166–9170. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.20.9166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chan A C, Iwashima M, Turck C W, Weiss A. ZAP-70: a 70kD protein tyrosine kinase that associates with the TCR ζ chain. Cell. 1992;71:649–662. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90598-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chan A C, Kadlecek T A, Elder M E, Filipovich A H, Kuo W-L, Iwashima M, Parslow T G, Weiss A. ZAP-70 deficiency in an autosomal recessive form of severe combined immunodeficiency. Science. 1994;264:1599–1601. doi: 10.1126/science.8202713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheng A M, Rowley B, Pao W, Hayday A, Bolen J B, Pawson T. Syk tyrosine kinase required for mouse viability and B cell development. Nature. 1995;378:303–306. doi: 10.1038/378303a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Di Bartolo, V., D. Mege, V. Germain, M. Pelosi, E. Dufour, J.-M. Pascussi, F. Michael, G. Magistrelli, A. Isacchi, and O. Acuto. T cell antigen receptor signaling depends on the SH2-mediated association of lck to ZAP-70. Submitted for publication.

- 11.Elder M E, Lin D, Clever J, Chan A C, Hope T J, Weiss A, Parslow T. Human severe combined immunodeficiency due to a defect in ZAP-70, a T cell tyrosine kinase. Science. 1994;264:1596–1599. doi: 10.1126/science.8202712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hatada M H, Lu X, Laird E R, Green J, Morgenstern J P, Lou M, Marr C S, Phillips T B, Ram M K, Theriault K, Zoller M J, Karas J L. Molecular basis for the interactions of the protein tyrosine kinase ZAP-70 with the T cell receptor. Nature. 1995;377:32–38. doi: 10.1038/377032a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iwashima M, Irving B A, van Oers N S C, Chan A C, Weiss A. Sequential interactions of the TCR with two distinct cytoplasmic tyrosine kinases. Science. 1994;263:1136–1139. doi: 10.1126/science.7509083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kong G, Dalton M, Wardenberg J B, Straus D, Kurosaki T, Chan A C. Distinct tyrosine phosphorylation sites in ZAP-70 mediate activation and negative regulation of antigen receptor function. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:5026–5035. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.9.5026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kong G-H, Bu J-Y, Kurosaki T, Shaw A S, Chan A C. Reconstitution of Syk function by the ZAP-70 protein tyrosine kinase. Immunity. 1995;2:485–492. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90029-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lupher M L, Jr, Zhou S, Shoelson S E, Cantley L C, Band H. The Cbl phosphotyrosine-binding domain selects a D(N/D)XpY motif and binds to the Tyr292 negative regulatory phosphorylation site of ZAP-70. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:33140–33144. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.52.33140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Negishi I, Motoyama N, Nakayama K-I, Nakayama K, Senju S, Hatakeyama S, Zhang Q, Chan A C, Loh D Y. Essential role for ZAP-70 in both positive and negative selection of thymocytes. Nature. 1995;376:435–438. doi: 10.1038/376435a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neumeister E N, Zhu Y, Richard S, Terhorst C, Chan A S, Shaw A S. Binding of ZAP-70 to phosphorylated T-cell receptor ζ and η enhances its autophosphorylation and generates specific binding sites for SH2 domain-containing proteins. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:3171–3178. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.6.3171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Qian D, Mollenauer M, Weiss A. Dominant-negative ZAP-70 inhibits T cell antigen receptor signaling. J Exp Med. 1998;183:611–620. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.2.611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Qian D, Weiss A. T cell antigen receptor signal transduction. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1997;9:205–212. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(97)80064-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shapiro V S, Mollenauer M N, Greene W C, Weiss A. c-Rel regulation of IL-2 gene expression may be mediated through activation of AP-1. J Exp Med. 1996;184:1663–1670. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.5.1663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Takata M, Sabe H, Hata A, Inazu T, Homma Y, Nukada T, Yamamura H, Kurosaki T. Tyrosine kinases Lyn and Syk regulate B cell receptor-coupled Ca2+ mobilization through distinct pathways. EMBO J. 1994;13:1341–1349. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06387.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Takata M, Kurosaki T. A role for Bruton’s tyrosine kinase in B cell antigen receptor-mediated activation of phospholipase C-g2. J Exp Med. 1996;184:31–40. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.1.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Turner M, Mee P J, Costello P S, Williams O, Price A A, Duddy L P, Furlong M T, Geahlen R L, Tybulewicz V L J. Perinatal lethality and blocked B cell development in mice lacking the tyrosine kinase Syk. Nature. 1995;378:298–302. doi: 10.1038/378298a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Oers N S C, Tao W, Watts J D, Johnson P, Aebersold R, Teh H-S. Constitutive tyrosine phosphorylation of the T-cell receptor (TCR) ζ subunit: regulation of TCR-associated protein kinase activity by TCR ζ. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:5771–5780. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.9.5771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wange R L, Samelson L E. Complex complexes: signaling at the TCR. Immunity. 1996;5:197–205. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80315-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wange R L, Guitian R, Isakov N, Watts J D, Aebersold R, Samelson L E. Activating and inhibitory mutations in adjacent tyrosines in the kinase domain of ZAP-70. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:18730–18733. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.32.18730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wange R L, Isakov N, Burke J, R. T, Otaka A, Roller P P, Watts J D, Aebersold R, Samelson L E. F2(Pmp)2-TAM3, a novel competitive inhibitor of the binding of ZAP-70 to the T cell antigen receptor, blocks early T cell signaling. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:944–948. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.2.944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wange R L, Malek S N, Desiderio S, Samelson L E. Tandem SH2 domains of ZAP-70 bind to T cell antigen receptor ζ and CD3ɛ from activated Jurkat T cells. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:19797–19801. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Watts J D, Affolter M, Krebs D L, Wange R L, Samelson L E, Aebersold R. Identification by electrospray ionization mass spectrometry of the sites of tyrosine phosphorylation induced in activated Jurkat T cells on the protein tyrosine kinase ZAP-70. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:29520–29529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wardenberg J B, Fu C, Jackman J K, Flotow H, Wilkinson S E, Williams D H, Johnson R, Kong G, Chan A C, Findell P R. Phosphorylation of SLP-76 by the ZAP-70 protein-tyrosine kinase is required for T cell receptor function. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:19641–19644. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.33.19641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weiss A, Littman D R. Signal transduction by lymphocyte antigen receptors. Cell. 1994;76:263–274. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90334-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32a.Williams, B. L., and R. T. Abraham. Unpublished data.

- 33.Williams B L, Schreiber K L, Zhang W, Wange R L, Samelson L E, Leibson P J, Abraham R T. Genetic evidence for differential coupling of Syk family kinases to the T-cell receptor: reconstitution studies in a ZAP-70-deficient Jurkat T-cell line. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:1388–1399. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.3.1388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Woodrow M, Clipstone N A, Cantrell D. p21ras and calcineurin synergize to regulate the nuclear factor of activated T cells. J Exp Med. 1993;178:1517–1522. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.5.1517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wu J, Motto D G, Koretzky G A, Weiss A. Vav and Slp76 interact and functionally cooperate in IL-2 gene activation. Immunity. 1996;4:593–602. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80485-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wu J, Katzav S, Weiss A. A functional T cell receptor signaling pathway is required for p95vav activity. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:4337–4346. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.8.4337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu J, Zhao Q, Kurosaki T, Weiss A. The Vav binding site (Y315) in ZAP-70 is critical for antigen receptor-mediated signal transduction. J Exp Med. 1997;185:1877–1882. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.10.1877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhao Q, Weiss A. Enhancement of lymphocyte responsiveness by a gain-of-function mutation of ZAP-70. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:6765–6774. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.12.6765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhao, Q., and A. Weiss. Unpublished data.