Abstract

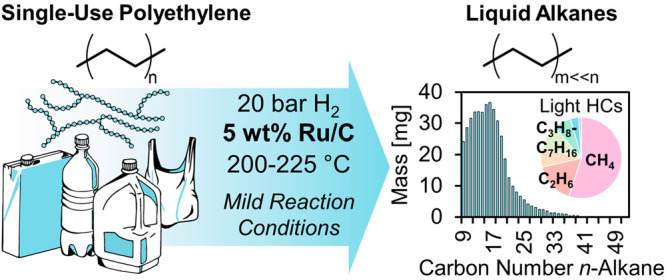

Chemical upcycling of waste polyolefins via hydrogenolysis offers unique opportunities for selective depolymerization compared to high temperature thermal deconstruction. Here, we demonstrate the hydrogenolysis of polyethylene into liquid alkanes under mild conditions using ruthenium nanoparticles supported on carbon (Ru/C). Reactivity studies on a model n-octadecane substrate showed that Ru/C catalysts are highly active and selective for the hydrogenolysis of C(sp3)–C(sp3) bonds at temperatures ranging from 200 to 250 °C. Under optimal conditions of 200 °C in 20 bar H2, polyethylene (average Mw ∼ 4000 Da) was converted into liquid n-alkanes with yields of up to 45% by mass after 16 h using a 5 wt % Ru/C catalyst with the remaining products comprising light alkane gases (C1–C6). At 250 °C, nearly stoichiometric yields of CH4 were obtained from polyethylene over the catalyst. The hydrogenolysis of long chain, low-density polyethylene (LDPE) and a postconsumer LDPE plastic bottle to produce C7–C45 alkanes was also achieved over Ru/C, demonstrating the feasibility of this reaction for the valorization of realistic postconsumer plastic waste. By identifying Ru-based catalysts as a class of active materials for the hydrogenolysis of polyethylene, this study elucidates promising avenues for the valorization of plastic waste under mild conditions.

Keywords: plastic upcycling, hydrogenolysis, ruthenium, depolymerization, polyethylene, polyolefins, heterogeneous catalysis, alkanes

The development of polyolefins has enabled the production of safe and sturdy single-use plastic packaging for transportation and storage, sterile medical devices, and countless other transformative consumer products. Because the raw materials for producing polyolefins such as polyethylene (PE) and polypropylene (PP) are abundant and inexpensive, the manufacture of these plastics is immense and continues to grow. Worldwide, approximately 380 million tons of plastics are generated annually, 57% percent of which are polyolefins.1 Projections estimate that by 2050, plastic production will reach over 1.1 billion tons per year.2 From a chemistry perspective, the strong sp3 carbon–carbon bonds in polyolefins that provide desirable material properties also make them highly recalcitrant to degradation. Mechanical recycling is one method of utilizing plastic waste; however, only around 16% of plastic is actually recycled3 and usually ends up being “downcycled” into lower-value materials with diminished properties.4 The majority of single-use plastics end up in landfills or the environment, harming the ecosystem and affecting the natural environment.1,3,5

Thermochemical pathways such as pyrolysis and thermal cracking enable polyolefin depolymerization by breaking the strong C–C bonds in PE to produce small molecules that could be used as fuel or integrated into chemical refineries. However, these processes are energy intensive and suffer from low control over product selectivity.6−8 Alternatively, C–C bond cleavage via hydrogenolysis allows for selective depolymerization of polyolefins into liquid alkanes with targeted molecular weight ranges. This reaction has been studied in the context of short-chain alkane9−14 and lignin15,16 conversion but has not been extensively explored for the depolymerization of polyolefins with high molecular weights. Dufaud and Basset studied the degradation of model PE (C20–C50) and PP over a zirconium hydride supported on silica–alumina and found moderate activity under mild conditions (190 °C).17 Celik et al. investigated hydrogenolysis using well-dispersed Pt nanoparticles supported on SrTiO3 nanocuboids for the depolymerization of PE (Mn = 8000–158 000 Da) at 170 psi H2 and 300 °C for 96 h under solvent-free conditions, obtaining high yields of liquid hydrocarbons.18 The authors argued that this catalyst is superior to Pt/Al2O3 because it produced fewer light hydrocarbons and promoted favorable adsorption of PE on Pt sites. Open questions remain whether the higher yield of light hydrocarbons over Pt/Al2O3 was due to the acidity of the support, a promotional effect of the isomerization and hydrocracking pathways, or increased activity for terminal C–C bond cleavage, and whether similar activity could be obtained at lower temperatures. Indeed, further investigation of other supported noble metals for hydrogenolysis at even milder conditions is needed.

Here, we demonstrate the selective depolymerization of polyethylene to processable liquid hydrocarbons under mild conditions in the absence of solvent using Ru nanoparticles supported on carbon. First, we screened a series of noble metal catalysts using n-octadecane—a model compound for linear polyethylene—and identified Ru nanoparticles supported on carbon as the most active. Next, we investigated the C–C bond cleavage selectivity as a function of conversion to understand how product distributions change as a function of extent of reaction. We then implemented optimized reaction conditions for the hydrogenolysis of a model PE substrate (average Mw 4000 Da) and commercial low-density polyethylene (LDPE). Finally, we demonstrated that the Ru/C catalyst is capable of converting LDPE from a real postconsumer plastic bottle. The identification of Ru-based catalysts as a class of materials for highly active hydrogenolysis is important for developing effective depolymerization processes of waste plastics to produce processable and transportable liquid that could be used as fuels, chemicals, or synthons for the next generation of infinitely recyclable polymers.19

Ruthenium-based catalysts such as Ru/CeO2, Ru/SiO2, Ru/Al2O3, and Ru/TiO2 have been shown to be active both for the hydrogenolysis of light alkanes9−14 and lignin.20,21 Our group has also shown that cobalt-based catalysts have tunable activity for C–O vs C–C bond hydrogenolysis of oxygenated arenes.22 These previous observations prompted us to test a series of noble metal catalysts including Ru- and Co-based catalysts, as well as other transition metals, for the hydrogenolysis of n-octadecane in 25 mL Parr stainless steel pressurized reaction vessels under temperatures and H2 pressures ranging from 200 to 250 °C and 30–50 bar, respectively (see Table 1). Products were identified by gas chromatography mass spectrometry (GC-MS) and quantified using a GC equipped with a flame ionization detector (FID) and a thermal conductivity detector (TCD). Additional methods, catalyst characterization, and product characterization are provided in the Supporting Information (Figures S1–S4, Tables S1–S5). At 250 °C, 1% Pt/γ-Al2O3, NiO, 5 wt % Ni on carbon, and γ-Al2O3 showed little to no activity. Co-based catalysts (entries 1 and 2) and Rh-based catalysts (entry 9) showed moderate hydrogenolysis activity, converting n-octadecane into a range of C1–C17 alkanes. Notably, Ru-based catalysts stood out for their high hydrogenolysis activity (entries 5–8, 10, and 11). Specifically, the 5 wt % Ru/C catalyst (entry 10) reached an n-octadecane conversion of 92% at 200 °C, generating a mixture of liquid and gaseous alkanes, while at 250 °C, 100% of the n-octadecane was converted into CH4. Due to the high activity at low temperatures and relatively low catalyst loadings, the 5 wt % Ru/C catalyst was selected for further investigation. Using a catalyst that is active at low temperatures decreases both the energy requirements for polyethylene processing and the thermodynamic driving force toward terminal C–C bond cleavage to produce CH4.

Table 1. Hydrogenolysis of n-Octadecane Using Heterogeneous Transition Metal Catalystsa.

| entry | catalyst | temp (°C) | mass catalyst (mg) | conversion, C18 (mol %) | products (liquid) | products (gaseous) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Co3O4 | 200 | 104 | 0 | none | none |

| 2 | Co3O4 | 250 | 109 | 46 | n-alkanes (C14–C17) | n/a |

| 3 | γ-Al2O3 | 250 | 103 | 0 | none | none |

| 4 | 1% Pt/γ-Al2O3 | 250 | 47.0 | 0 | none | none |

| 5 | RuO2 | 250 | 43.0 | 100 | none | CH4 |

| 6 | RuO2 | 200 | 20.4 | 9 | n-alkanes (C9–C17) | CH4 |

| 7 | 5% Ru/Al2O3 | 200 | 26.7 | 65 | n-alkanes (C8–C17) | light alkanes (C1–C4) |

| 8 | 5% Ru/Al2O3 | 250 | 26.3 | 100 | none | light alkanes (C1–C4) |

| 9 | 5% Rh/C | 250 | 22.6 | 21 | n-alkanes (C8–C17) | light alkanes (C1–C6) |

| 10 | 5% Ru/C | 200 | 25.0 | 92 | n-alkanes (C6–C17) | light alkanes (C1–C5) |

| 11 | 5% Ru/C | 250 | 25.0 | 100 | none | CH4 |

| 12 | NiO | 250 | 25.0 | 0 | none | none |

| 13 | 5% Ni/C | 250 | 25.0 | <4 | trace n-alkanes (C8–C17) | trace light alkanes (C1–C3) |

Reaction conditions: 700 mg of n-octadecane, 14 h, 30 bar H2 (entries 1, 10), 50 bar H2 (entries 2–9, 11–13).

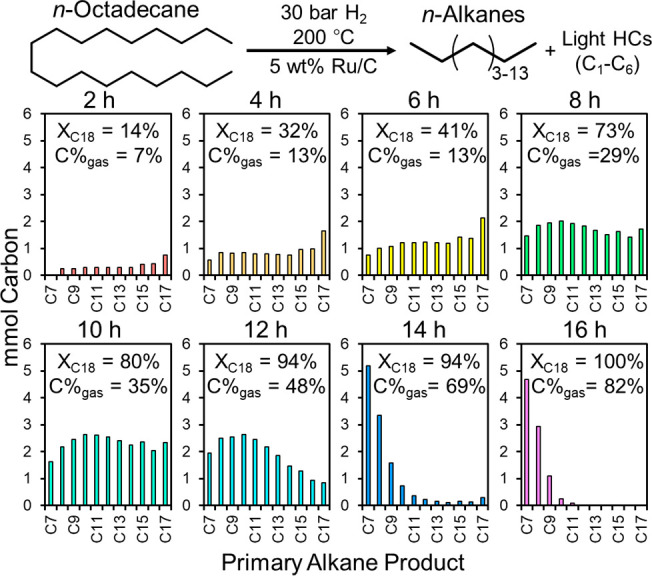

Based on these preliminary results, the hydrogenolysis of n-octadecane over 5 wt % Ru/C at 200 °C was investigated as a function of time to track changes in the product distribution of n-alkanes with increasing conversion. As shown in Figure 1, the product distribution after 2 h includes C8–C17n-alkanes, and increasing the extent of reaction shifts the product distribution to lower molecular weights, implicating sequential cleavage events of both terminal and nonterminal C–C bonds. After 16 h, 100% of the n-octadecane was consumed, and the products shifted from liquid-range alkanes to gaseous products in the C1–C6 range. Based on these data, we surmised the hydrogenolysis of longer-chain polyethylene over Ru/C would also proceed via both terminal C–C bond cleavage to produce CH4 and internal C–C bond cleavage to produce shorter chain alkanes.

Figure 1.

Hydrogenolysis of n-octadecane as a function of time over 5 wt % Ru/C. Reaction conditions: 700 mg n-octadecane (∼50 mmol carbon), 25 mg 5 wt % Ru/C, 30 bar H2, 200 °C.

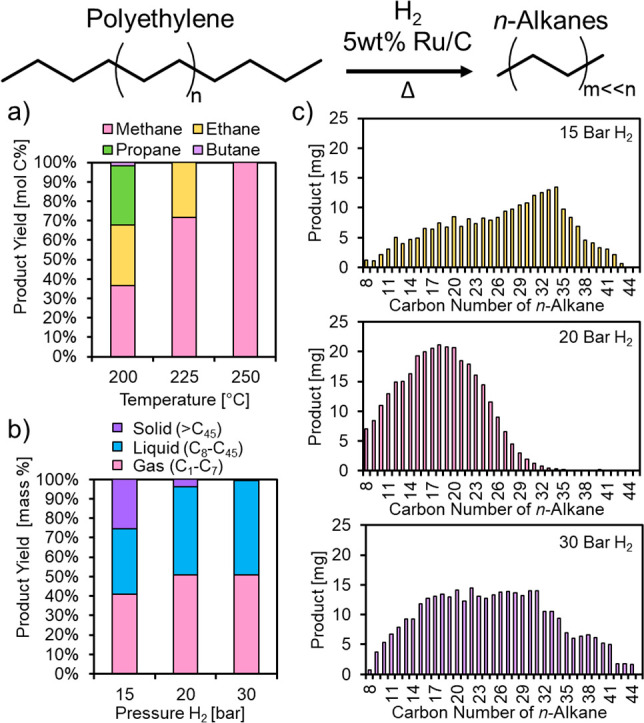

The effect of temperature and hydrogen pressure on the hydrogenolysis of model polyethylene (Sigma-Aldrich, average Mw 4000 Da, average Mn 1700 Da, Table S1) was investigated over Ru/C to identify suitable reaction conditions for the hydrogenolysis of realistic postconsumer polyethylene waste (Figure 2, Figures S5–S7). At all temperatures investigated between 200 and 250 °C and using a 4:1 PE:catalyst mass ratio, polyethylene conversion reached 100% and generated exclusively gaseous products. At 200 °C, the head space contained mainly CH4, ethane, propane, and butane. Upon increasing the temperature to 225 °C, only CH4 and ethane were produced, and at 250 °C, the product yield was pure CH4 in near stoichiometric yields. The effect of hydrogen pressure on polyethylene hydrogenolysis products over Ru/C at 200 °C (using a 28:1 PE:catalyst mass ratio) is shown in Figure 2b, with a more detailed compositional analysis shown in Figure 2c. At increasing hydrogen pressures, the yield of gas relative to liquid and solid increases, suggesting a sequence shifting from solid alkanes (>C45) to solvated liquid alkanes (C8–C45), and finally to light alkane gases (C1–C7).

Figure 2.

Optimizing reaction conditions for the hydrogenolysis of polyethylene (average Mw 4000): (a) effect of temperature on overall product yields, 100 mg PE (average Mw 4000), 16 h, 30 bar H2, 25 mg 5 wt % Ru/C, 200–250 °C, 100% conversion. (b) Effect of H2 pressure on overall product composition, 200 °C, 16 h, 700 mg PE (average Mw 4000), 25 mg 5 wt % Ru/C. (c) Liquid composition of C8–C45 products shown in panel b.

Based on these data, we selected reaction conditions of 20 bar H2, 200 °C as optimal for producing a distribution of n-alkanes in the processable liquid range when using 700 mg polyethylene and 25 mg of catalyst. Investigations of hydrogenolysis of Ir-based catalysts with both experiment and density functional theory (DFT) calculations have suggested that hydrogen inhibits hydrogenolysis rates, the extent of which is affected by the structure of the alkane due to changes in enthalpy and entropy of the transition state.23 A study of the mechanism of hydrogenolysis of light alkanes over Ru/CeO2 also suggested that H2 pressure had a marked effect on selectivity for C–C bond scission, where high H2 pressure is necessary to avoid CH4 formation.11 These opposing effects explain why an intermediate H2 pressure of 20 bar was ideal for achieving high selectivity to liquid-range n-alkanes in our experiments. As observed from both the model compound studies with n-octadecane and with polyethylene, the product distribution and selectivity for hydrogenolysis can be tuned by manipulating reaction temperature, H2 pressure, and residence time.

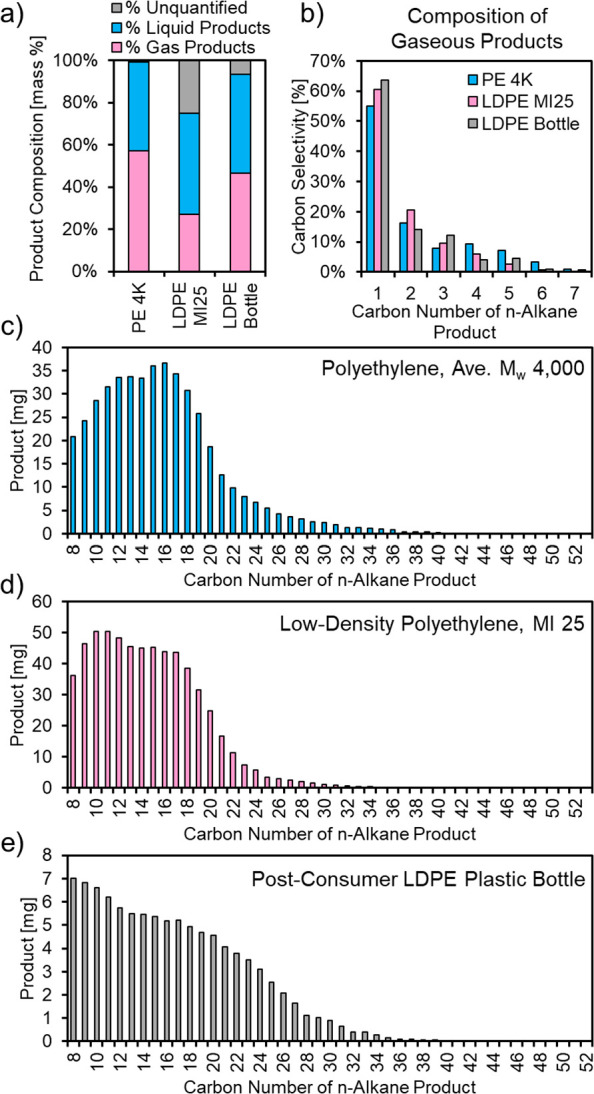

Implementation of hydrogenolysis technology for the catalytic upcycling of genuine postconsumer polyolefin waste will require flexibility in the molecular weight and composition of the feedstock, including extent of branching, moisture, and contaminants. To this end, we demonstrated the hydrogenolysis of two additional sources of polyethylene: low-density polyethylene (Aldrich, Table S2) with a melt index 25 g/10 min (190 °C/2.16 kg), denoted here as LDPE MI25, and a postconsumer LDPE plastic bottle. The former is a material commonly used in toys, lids, and closures,24 and the latter was previously used as a solvent bottle containing water (VWR). The results from these reactions are summarized in Figure 3 and Figures S8–S14. The mass yields of liquid (C8–C45) and gaseous (C1–C7) n-alkanes for these substrates are shown in Figure 3a. For each of these substrates, both liquid and gaseous products are obtained, while the gray represents the unaccounted products in the mass balance. Only gaseous and liquid products were observed for the reactions over polyethylene (average Mw 4000 Da, denoted PE 4K), LDPE MI25, and the LDPE plastic bottle. The gaseous product distributions for the three substrates are shown in Figure 3b, and the C8–C45+ products are shown in Figure 3c–e for PE 4K, LDPE MI25, and the postconsumer LDPE plastic bottle, respectively. A small number of branched alkanes was also observed (Figure S11) over LDPE MI25, likely due to carbon chain branches in the substrate. While less substrate was used for the hydrogenolysis of the LDPE plastic bottle (200 mg) compared to the model polyethene (1400 mg), the formation of liquid products in spite of the higher complexity of this material and lack of any pretreatment is promising and indicates the feasibility of this method for the production of liquid products from postconsumer polyolefins. Furthermore, we observed that at longer reaction times (16 h) at 225 °C, the LDPE plastic bottle could be converted into CH4 with nearly 100% selectivity (Figure S14), which represents a promising avenue to produce natural gas from postconsumer plastic waste.

Figure 3.

(a) Product distributions for polyethylene hydrogenolysis over 5 wt % Ru/C with PE 4K (200 °C, 1.4 g of PE 4K, 56 mg of 5 wt % Ru/C, 22 bar H2, 16 h), LDPE MI25 (225 °C, 1.4 g of LDPE, 50 mg of 5 wt % Ru/C, 22 bar H2, 16 h), and a postconsumer LDPE plastic bottle (225 °C, 200 mg of LDPE, 25 mg of 5 wt % Ru/C, 22 bar H2, 2 h); (b) gaseous product distribution for PE 4K, LDPE MI25, and an LDPE plastic bottle; (c) C8–C45+ product distribution for PE 4K; (d) C8–C45+ product distribution for LDPE MI25; (e) C8–C45+ product distribution for an LDPE plastic bottle.

The depolymerization of a well-characterized NIST linear polyethylene Standard Reference Material (SRM 1475, avg Mw ∼ 52 000 Da, avg Mn ∼ 18 310 Da)25 was also investigated over 5 wt % Ru/C and was found to undergo complete conversion to liquid and gaseous alkanes under similar reaction conditions (Figures S15–S17). In addition, polyethylene hydrogenolysis experiments over recycled catalyst also demonstrated that the catalyst can be reused with minimal change in activity (Figure S18, Table S6). Characterization of the fresh and spent catalyst (XRD, TEM) is shown in Figures S2–S4. The slight increase in average particle diameter from 1.62 ± 0.36 to 2.10 ± 0.43 nm for the spent catalyst indicates some aggregation of nanoparticles over the course of the reaction, although changes in dispersion are minimal, and catalytic activity is maintained. For a more rigorous investigation of catalyst stability over time, the hydrogenolysis of n-dodecane, a model compound for PE, was studied in a gas phase flow reactor over 5 wt % Ru/C at 225 °C and showed high activity over 60 h of time on stream with minimal catalyst deactivation and changes to product distribution (Figure S19). The calculated lower bound for the number of catalytic turnovers (TON > 15 000) suggests that the activity of 5 wt % Ru/C is well within the range of industrially relevant catalysts (Supporting Information).26

In this work, we demonstrated that Ru-based catalysts exhibit high activity and stability for the hydrogenolysis of solid polyolefin plastics under mild conditions to produce processable liquid alkanes. Temperature, hydrogen pressure, and reaction time can all be manipulated to control product distribution and selectivity, enabling the production of liquid products or complete hydrogenolysis to pure CH4. The identification of Ru-based materials as a class of heterogeneous catalysts for the efficient depolymerization of polyethylene into liquid alkanes, or pure CH4 compatible with existing natural-gas infrastructure, opens doors for future investigations into improving reactivity, understanding selectivity, and exploration of a variety of feedstocks and compositions. Further studies involving the effects of substrate branching, reactivity, and characterization of other hydrocarbon polymers such as polypropylene and polystyrene, mechanistic interrogation of active site requirements for selective internal C–C bond cleavage, models for predicting distributions of C–C bond cleavage, utilization of experimentally determined kinetic parameters to inform cleavage probability at various locations along the carbon chain, characterization of the Ru catalyst surface and mass transfer in the polymer melt, and technoeconomic analysis of the process are currently underway in our laboratory.

With heterogeneous catalysts, additional parameters for exploration include utilizing tailored acid or acid–base supports to promote tandem isomerization and hydrogenolysis, zeolites and microporous materials to impose confinement effects, Raney-type catalysts to improve catalytic activity, and the synthesis of bimetallic catalysts to improve selectivity, activity, and stability, and to control C–O, C–C, and C=C bond scission in mixed plastics feeds. Exhaustive studies into the effects of moisture and contaminants27 as well as engineering product removal strategies to decrease the formation of light alkanes will be critical for the industrialization of this reaction, enabling the integration of polyolefin upcycling technology into the global economy and ultimately providing an economic incentive for the removal of waste plastics from the landfill and environment.

Acknowledgments

Funding was provided by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy, Advanced Manufacturing Office (AMO) and Bioenergy Technologies Office (BETO). This work was performed as part of the Bio-Optimized Technologies to keep Thermoplastics out of Landfills and the Environment (BOTTLE) Consortium and was supported by AMO and BETO under Contract DE-AC36-08GO28308 with the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL), operated by Alliance for Sustainable Energy, LLC. The BOTTLE Consortium includes members from MIT, funded under Contract DE-AC36-08GO28308 with NREL. The authors thank Sujay Bagi for assistance with transmission electron microscopy and Kathryn Beers and Sara Orski at NIST for providing polyethylene standard reference material (SRM 1475). The views expressed in the article do not necessarily represent the views of the DOE or the U.S. Government.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/jacsau.0c00041.

Materials and methods (Figure S1, Table S1–S3), catalyst characterization (Figure S2–S3, Tables S4–S5), product characterization (GC-MS, GC-FID, GC-MS, supporting images, Figures S5–S17), recyclability studies (Figure S18, Table S6), catalyst stability studies in flow reactor, and TON calculation (Figure S19) (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Geyer R.; Jambeck J. R.; Law K. L. Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3 (7), e1700782 10.1126/sciadv.1700782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong M.; Chen E. Y. X. Future Directions for Sustainable Polymers. Trends Chem. 2019, 1 (2), 148–151. 10.1016/j.trechm.2019.03.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ormonde E.; DeGuzman M.; Yoneyama M.; Loechner U.; Zhu X.. Chemical Economics Handbook (CEH): Plastics Recycling; IHS Markit: 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Salem S. M.; Lettieri P.; Baeyens J. Recycling and recovery routes of plastic solid waste (PSW): A review. Waste Manage. (Oxford, U. K.) 2009, 29 (10), 2625–2643. 10.1016/j.wasman.2009.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrady A. L. Microplastics in the marine environment. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2011, 62, 1596–1605. 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2011.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serrano D. P.; Aguado J.; Escola J. M. Developing Advanced Catalysts for the Conversion of Polyolefinic Waste Plastics into Fuels and Chemicals. ACS Catal. 2012, 2 (9), 1924–1941. 10.1021/cs3003403. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anuar Sharuddin S. D.; Abnisa F.; Wan Daud W. M. A.; Aroua M. K. A review on pyrolysis of plastic wastes. Energy Convers. Manage. 2016, 115, 308–326. 10.1016/j.enconman.2016.02.037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kunwar B.; Cheng H. N.; Chandrashekaran S. R.; Sharma B. K. Plastics to fuel: a review. Renewable Sustainable Energy Rev. 2016, 54, 421–428. 10.1016/j.rser.2015.10.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bond G. C.; Rajaram R. R.; Burch R. Hydrogenolysis of Propane, n-Butane, and Isobutane over Variously Pretreated Ru/TI02 Catalysts. J. Phys. Chem. 1986, 90, 4877–4881. 10.1021/j100411a032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bond G. C.; Yide X. Effect of Reduction and Oxidation on the Activity of Ruthenium/Titania Catalysts for n- Butane Hydrogenolysis. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1983, 1248–1249. 10.1039/c39830001248. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa Y.; Oya S. I.; Kanno D.; Nakaji Y.; Tamura M.; Tomishige K. Regioselectivity and Reaction Mechanism of Ru-Catalyzed Hydrogenolysis of Squalane and Model Alkanes. ChemSusChem 2017, 10 (1), 189–198. 10.1002/cssc.201601204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flaherty D. W.; Hibbitts D. D.; Iglesia E. Metal-Catalyzed C-C Bond Cleavage in Alkanes: Effects of Methyl Substitution on Transition-State Structures and Stability. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136 (27), 9664–76. 10.1021/ja5037429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egawa C.; Iwasawa Y. Ethane hydrogenolysis on a Ru(1,1,10) surface. Surf. Sci. 1988, 198 (1), L329–L334. 10.1016/0039-6028(88)90465-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kempling J. C.; Anderson R. B. Hydrogenolysis of n-Butane on Supported Ruthenium. Ind. Eng. Chem. Process Des. Dev. 1970, 9 (1), 116–120. 10.1021/i260033a021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dong L.; Lin L.; Han X.; Si X.; Liu X.; Guo Y.; Lu F.; Rudić S.; Parker S. F.; Yang S.; Wang Y. Breaking the Limit of Lignin Monomer Production via Cleavage of Interunit Carbon-Carbon Linkages. Chem. 2019, 5 (6), 1521–1536. 10.1016/j.chempr.2019.03.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao L.-P.; Wang S.; Li H.; Li Z.; Shi Z.-J.; Xiao L.; Sun R.-C.; Fang Y.; Song G. Catalytic Hydrogenolysis of Lignins into Phenolic Compounds over Carbon Nanotube Supported Molybdenum Oxide. ACS Catal. 2017, 7 (11), 7535–7542. 10.1021/acscatal.7b02563. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dufaud V.; Basset J.-M. Catalytic Hydrogenolysis at Low Temperature and Pressure of Polyethylene and Polypropylene to Diesels or Lower Alkanes by a Zirconium Hydride Supported on Silica-Alumina: A Step Toward Polyolefin Degradation by the Microscopic Reverse of Ziegler± Natta Polymerization. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1998, 37 (6), 806–810. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celik G.; Kennedy R. M.; Hackler R. A.; Ferrandon M.; Tennakoon A.; Patnaik S.; LaPointe A. M.; Ammal S. C.; Heyden A.; Perras F. A.; Pruski M.; Scott S. L.; Poeppelmeier K. R.; Sadow A. D.; Delferro M. Upcycling Single-Use Polyethylene into High-Quality Liquid Products. ACS Cent. Sci. 2019, 5 (11), 1795–1803. 10.1021/acscentsci.9b00722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong M.; Chen E. Y. Towards Truly Sustainable Polymers: A Metal-Free Recyclable Polyester from Biorenewable Non-Strained gamma-Butyrolactone. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55 (13), 4188–93. 10.1002/anie.201601092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y.; Jiang G.; Xu G.; Mu X. Hydrogenolysis of lignin model compounds into aromatics with bimetallic Ru-Ni supported onto nitrogen-doped activated carbon catalyst. Mol. Catal. 2018, 445, 316–326. 10.1016/j.mcat.2017.12.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li T.; Lin H.; Ouyang X.; Qiu X.; Wan Z. In Situ Preparation of Ru@N-Doped Carbon Catalyst for the Hydrogenolysis of Lignin To Produce Aromatic Monomers. ACS Catal. 2019, 9 (7), 5828–5836. 10.1021/acscatal.9b01452. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shetty M.; Zanchet D.; Green W. H.; Roman-Leshkov Y. Cooperative Co0/CoII Communications Sites Stabilized by a Perovskite Matrix Enable Selective C-O and C-C bond Hydrogenolysis of Oxygenated Arenes. ChemSusChem 2019, 12, 2171–2175. 10.1002/cssc.201900664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibbitts D. D.; Flaherty D. W.; Iglesia E. Effects of Chain Length on the Mechanism and Rates of Metal-Catalyzed Hydrogenolysis of n-Alkanes. J. Phys. Chem. C 2016, 120 (15), 8125–8138. 10.1021/acs.jpcc.6b00323. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- DOW LDPE 993I Low Density Polyethylene Resin; The Dow Chemical Company, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hoeve C. A. J.; Wagner H. L.; Brown J. E.; Christensen R. G.; Frolen L. J.; Maurey J. R.; Ross G. S.; Verdier P. H.. The Characterization of Linear Polyethylene SRM 1475; National Bureau of Standards: Washington D.C., 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Kozuch S.; Martin J. M. L. Turning Over” Definitions in Catalytic Cycles. ACS Catal. 2012, 2 (12), 2787–2794. 10.1021/cs3005264. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ragaert K.; Delva L.; Van Geem K. Mechanical and chemical recycling of solid plastic waste. Waste Manage. (Oxford, U. K.) 2017, 69, 24–58. 10.1016/j.wasman.2017.07.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.