Abstract

Catalysis remains one of the final frontiers in molecular uranium chemistry. Depleted uranium is mildly radioactive, continuously generated in large quantities from the production and consumption of nuclear fuels and accessible through the regeneration of “uranium waste”. Organometallic complexes of uranium possess a number of properties that are appealing for applications in homogeneous catalysis. Uranium exists in a wide range of oxidation states, and its large ionic radii support chelating ligands with high coordination numbers resulting in increased complex stability. Its position within the actinide series allows it to involve its f-orbitals in partial covalent bonding; yet, the U–L bonds remain highly polarized. This causes these bonds to be reactive and, with few exceptions, relatively weak, allowing for high substrate on/off rates. Thus, it is reasonable that uranium could be considered as a source of metal catalysts. Accordingly, uranium complexes in oxidation states +4, +5, and +6 have been studied extensively as catalysts in sigma-bond metathesis reactions, with a body of literature spanning the past 40 years. High-valent species have been documented to perform a wide variety of reactions, including oligomerization, hydrogenation, and hydrosilylation. Concurrently, electron-rich uranium complexes in oxidation states +2 and +3 have been proven capable of performing reductive small molecule activation of N2, CO2, CO, and H2O. Hence, uranium’s ability to activate small molecules of biological and industrial relevance is particularly pertinent when looking toward a sustainable future, especially due to its promising ability to generate ammonia, molecular hydrogen, and liquid hydrocarbons, though the advance of catalysis in these areas is in the early stages of development. In this Perspective, we will look at the challenges associated with the advance of new uranium catalysts, the tools produced to combat these challenges, the triumphs in achieving uranium catalysis, and our future outlook on the topic.

Keywords: Actinides, Uranium, Small Molecule Activation, Catalysis, Molecular Complexes

Introduction

For the past century, uranium has been one of the most studied actinides. Despite the increasing interest in fundamental organo-actinide chemistry of the last 20 years,1 catalysis derived from uranium species remains relatively sparse. This is in part due to a number of challenges associated with organo-uranium chemistry, which diminish their catalytic utility. First and foremost, and due to ever-increasing austere regulations, uranium’s radioactivity limits its usage to laboratories capable of handling radioactive materials. The element’s grim public perception does not help either. There are, however, scientific obstacles to overcome as well. Its high oxophilicity results in very strong uranium–oxygen bonds, and uranium’s low electron affinity leads to high reduction potentials, which, ultimately, hampers the regeneration of the active, low-valent catalyst. While these properties can be leveraged for the synthesis of organo-uranium compounds, they hinder the prospects of catalysis. Despite all of these challenges, the development of uranium-based catalytic reactions has spanned the past 40 years, with molecular uranium chemistry and homogeneous catalysis having experienced a renaissance in the past two decades.

Arguably, the beginning of the current wave of interest in uranium chemistry began with Scott’s and Cummins’ reports of the first molecular dinitrogen complexes in 1998, wherein [U(N(N′)3)] was treated with an atmosphere of dinitrogen to generate the side-on N2-bridged complex [{(N(N′)3)U}2(μ2-η2η2-N2)] (Figure 1A).2 Later that same year, Cummins et al. reported the first end-on bridging dinitrogen complex, using the tris-amide [((Ar)(tBu)N)3U(THF)] in the presence of [Mo(N(tBu)(Ph))3] under an atmosphere of dinitrogen to generate the heterobimetallic [((Ar)(tBu)N)3U(μ-N2)Mo–((N(tBu)(Ph))3] (Figure 1B).3 Both of these results inspired and reinvigorated investigation of uranium’s potential as a catalyst in the Haber–Bosch process and initiated a “hunt” for a molecular uranium nitride species. These compounds are the first definitive structural examples of actinides coordinating dinitrogen and the first evidence of molecular interactions between uranium and dinitrogen since Haber’s initial patent on uranium’s catalytic competency in the Haber–Bosch process near the start of the 20th century.4 Additional strides to manifest potential intermediates in uranium-mediated dinitrogen reduction were soon to follow with Evans’ publication of the first monometallic uranium terminal dinitrogen complex [(Cp*3)U(η1-N2)] in 2003 (Figure 1C).5 The first example of a molecular uranium complex with a terminal nitrido ligand, [(TrenTIPS)U(N)], was then reported by Liddle et al. in 2013 (Figure 1D),6 which formed the basis for a synthetic cycle, producing ammonium chloride with the aid of trimesityl borane, TMSCl, and KC8.7 Finally, Mazzanti and co-workers reported the formation of an ammonia-evolving bimetallic uranium complex [K3{[U(OR)3]2(μ-N)(μ-η2:η2-N2)}] in 2017 (Figure 1E) and expanded on this report demonstrating the ability of a bridged dinitride complex to evolve ammonium chloride upon treatment with HCl in 2019.8,9

Figure 1.

(A) Scott’s reported side-on-bound N2-bridged diuranium complex; adapted from ref (2). (B) Cummins’ example of the first end-on-bound N2-bridged heteronuclear U/Mo complex; adapted from ref (3). (C) Evans’ demonstration of a terminally bound uranium dinitrogen complex; adapted from ref (5). (D) Liddle’s report of the first example of a terminally bound uranium nitride; adapted from ref (6). (E) Mazzanti’s uranium “cluster” showing the activation of molecular dinitrogen in a uranium-based system capable of evolving ammonia; adapted from ref (8).

Notably, uranium has also demonstrated an encouraging ability to reduce carbon monoxide and carbon dioxide with the first carbon monoxide complex being documented in 1986, when [(Me3SiC5H4)3U(CO)] was synthesized by Anderson et al. (Figure 2A).10 The unambiguous structural determination of a uranium carbonyl complex ([C5Me4H)3U(CO)]) was given by Parry et al. in 1995.11 Nearly 10 years later, Cloke and co-workers were able to demonstrate the reductive cyclotrimerization of carbon monoxide to form a dinuclear, mixed sandwich complex [{(η2-C8H4†)(Cp*)U}2(μ-C3O3)] under 1 atm of carbon monoxide (Figure 2C).12 Furthermore, Cloke et al. were able to expand this work to allow for the isolation of uranium complexes containing linear dimers and cyclotetramers through the alteration of the steric bulk on the adjacent Cp chelates.13 In 2004, our group reported the first example of an η1-OCO coordination mode of carbon dioxide in a UIV–CO2•– charge-separated [((Ad,t-BuArO)3tacn)U(η1-CO2)]14 complex (Figure 2B) as well as the first quantitative, stoichiometric example of uranium-mediated carbon dioxide reduction to form carbon monoxide and [{(t-Bu,t-BuArO)3tacn)U}2(μ-O)] when the chelate’s steric bulk is reduced from adamantyl to tert-butyl-derivatized aryloxides.15 These reactions with carbon dioxide and carbon monoxide are important first steps for the envisioned production of a synthetic closed-carbon cycle (vide infra), capable of generating renewable fuels (through Fischer–Tropsch catalysis upon reaction with “green” hydrogen) as well as providing renewable chemical feedstocks.

Figure 2.

(A) Anderson’s terminally bound carbon monoxide complex; adapted from ref (10). (B) Meyer’s end-on-bound carbon dioxide complex; adapted from ref (14). (C) Cloke’s reductive CO cyclotrimerization; adapted from ref (12).

Given the remarkable stoichiometric reactivity already shown with dinitrogen, carbon dioxide, and carbon monoxide, the interest in the development of uranium-based catalysis is self-evident. In this Perspective, we will follow up on a recent viewpoint16 and discuss important advances in uranium catalysis and closed-cycle transformations of small molecules of industrial relevance. Looking toward the future, we will discuss related synthetic cycles on the cusp of becoming catalytic reactions and provide our insights into what we see as the future of uranium catalysis.

Uranyl Photochemical Catalysis

The uranyl moiety ([O=UVI=O]2+) is one of the most common structural motifs in uranium chemistry. Its strong uranium–oxygen bonds as well as uranium’s high oxidation state make uranyl species particularly stable toward oxidation, enabling these complexes to be handled under oxygen and in aqueous environments.17 Despite this inherent stability, UV irradiation effects ligand-to-metal charge-transfers; thereby, generating highly oxidizing (+2.6 V vs SCE) terminal oxygen radicals (O=UV–O•) (Figure 3A). These uranyl oxygen radicals can act as very potent photo oxidation catalysts. In this section, we will describe the photocatalytic nature of uranyl complexes in the development of new reactions. It should also be noted that Behera published a review on uranyl catalysis in early 2021, which provides an extensive summary of modern uranyl chemistry, some of which was found to be outside the scope of this Perspective.17

Figure 3.

(A) Generalization of radical behavior displayed by [UO2]2+ upon irradiation. (B) Sorenson’s radical fluorination using uranyl nitrate as a catalyst; adapted from ref (18). (C) Ravelli’s example of radical C–C bond formation using uranyl nitrate as a catalyst; adapted from ref (19). (D) Jiang’s oxidation of organic sulfides; adapted from ref (20). (E) Arnold’s photocatalytic oxidation of C–H bonds; adapted from ref (21).

In 2016, Sorenson and co-workers demonstrated direct fluorination of unactivated, aliphatic C–H bonds in moderate to high yields (55–95%) (Figure 3B) using uranyl nitrate as the active catalyst.18 While this reaction suffers from a narrow substrate scope, it serves as a proof of concept for uranyl species to function in radical processes. In 2019, Ravelli et al. were able to expand this chemistry to include the formation of new C–C bonds with electron-deficient olefins using the same catalyst.19 Generally, these reactions occur through the same mechanism (Figure 3C) in which uranyl nitrate is first excited to form a terminal oxygen radical, which engages in hydrogen atom transfer (HAT), thus generating a carbon-centered radical species and a terminal hydroxide. The carbon radical adds to an olefin forming a new C–C bond with an adjacent carbon radical, which is subsequently reduced by O=U(V)=OH to the corresponding carbanion, thereby regenerating the uranyl catalyst through single electron transfer (SET). The carbanion is protonated in solution to generate the final product.

Jiang and co-workers were able to demonstrate the oxygenation of organic sulfide compounds, using uranyl acetate as a catalyst in the presence of oxygen.20 This reaction follows the same initiation pathway described by Sorenson with irradiation of the uranyl complex giving rise to a terminal oxygen radical. This radical can then oxidize the sulfide by one electron to generate a radical cation capable of coupling with triplet oxygen, generating a persulfoxide radical that is then reduced to a persulfoxide anion by O=U(V)=O–, thus restoring the uranyl catalyst. Upon comproportionation with another equivalent of sulfide, the persulfoxide is converted to sulfoxide. Interestingly, if phosphoric acid is present during this reaction, the oxidation terminates with the formation of sulfoxide, but in the absence of phosphoric acid the sulfoxide can be reoxidized by uranyl acetate and re-enters the catalytic cycle to give sulfones instead. In a related reaction, Arnold et al. were able to demonstrate the oxidation of unfunctionalized C–H bonds using a phenanthroline-ligated uranyl nitrate complex to form cyclic esters and ketones (Figure 3E).21

Uranium-Based Catalysis: Oxidative Additions and Reductive Eliminations

The processes of oxidative addition and reductive elimination lie at the heart of most modern homogeneous catalytic reactions, serving as “bookends” enclosing catalytic cycles. Often, oxidative addition initiates a catalytic process through insertion of a metal center into a labile chemical bond, concomitant with oxidation of the catalyst.22 Likewise, reductive elimination is typically the final step in a catalytic cycle, resulting in the regeneration of the metal catalyst to its active form and returning to the metal’s initial oxidation state; thereby, forming a new chemical bond (Figure 4A and B). A classic example of this “bookended” catalytic cycle can be observed in most organic cross coupling reactions, wherein a metal center inserts into a carbon–halide bond followed by transmetalation (commonly with organozinc, organocuprates or Grignard reagents) and termination by reductive elimination to regenerate the active metal catalyst through formation of a new chemical bond (Figure 4C).23 Most oxidative addition reactions reported for uranium occur through bimolecular, one-electron radical processes (Figure 4B) and are largely limited to the cleavage of carbon–halide or chalcogen–chalcogen bonds. These processes are relatively common.24 In contrast, and despite the number of oxidative additions known for uranium, reductive elimination is particularly rare with only a handful of examples described in the literature; key examples of these reactions are reported by Seyam,25 Bart et al.,26 and Liddle et al.27 (Figure 5). The challenge associated with reductive eliminations are likely due to uranium’s low electron affinity, which results in very high reduction potentials for high-valent uranium ions in coordination complexes. Thus, the generation of high-valent uranium(IV), (V), and (VI) complexes from lower-valent uranium(III), or even uranium(II), complexes is relatively trivial, while the reduction back to their low-valent counter parts remains synthetically challenging. Accordingly, traditional two-electron catalytic cycles, such as cross-coupling reactions, are virtually unknown for uranium.

Figure 4.

(A) General process for oxidative addition and reductive elimination through a two-electron pathway. (B) General process for oxidative addition and reductive elimination through two single-electron processes either concerted or stepwise. (C) General mechanism for catalytic cross coupling reactions.

Figure 5.

(A) Seyam’s example of reductive elimination from a uranium complex; adapted from ref (25). (B) Bart’s illustration of induced reductive elimination caused by introduction of a redox-active ligand; adapted from ref (26). (C) Liddle’s case of the reversible bonding of a diazo-complex, demonstrating a rare net four-electron reductive elimination; adapted from ref (27).

Two general strategies have been employed to circumvent the problems associated with high reduction potentials and poor stability of low-valent uranium centers, with these being (a) the development of redox-neutral catalytic reactions and (b) the use of external reductants for catalytic turnover. For the purpose of this Perspective, we will examine molecular uranium catalysts which utilize these two strategies to enable catalytic transformations. Further, we will discuss some preliminary studies describing the development of synthetic cycles that, we believe, are appealing and could be relevant in future developments of uranium-based catalysis.

Redox-Neutral Processes

As mentioned before, while most uranium species appear incapable of engaging in reductive elimination, there are numerous reports of formally redox neutral processes in the +4, +5, and +6 oxidation states. As such, the most employed strategy for uranium catalysis is sigma-bond metathesis using mid- to high-valent uranium species. This method has afforded a broad scope of reactions, including hydrogenation, polymerization, hydroamination, oligomerization, hydrosilylation, and hydroboration, which we will discuss in this Perspective. While this is not an exhaustive list, it does serve to demonstrate a wide functional group tolerance and a wide range of reactivities. Generally, these reactions occur through common steps. First, a precatalyst species liberates a labile molecule (commonly hexamethyldisilazane (HMDS), methane, or dihydrogen) to generate the active catalyst. This active catalyst is then able to undergo a series of propagating insertions, ultimately terminating in the abstraction of another labile molecule, such as a hydride, to regenerate the active catalyst.

Hydrogenation

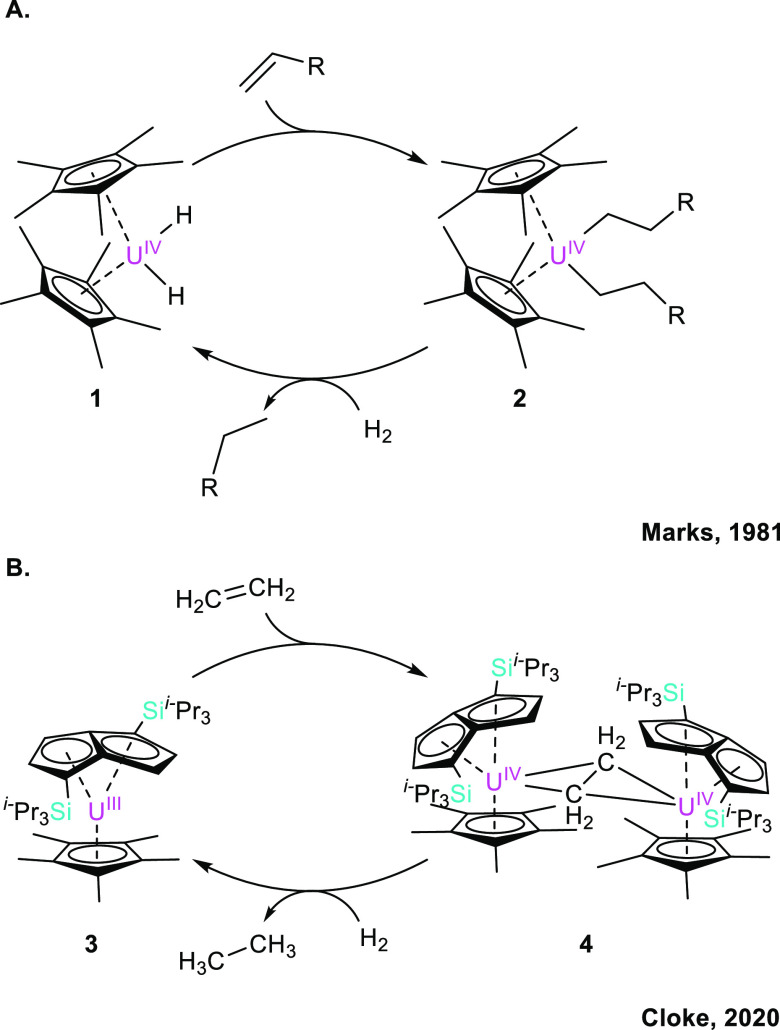

One of the earliest examples of uranium catalysis was demonstrated by Marks et al. in 1981, who established that [(Cp*)2U(Me)2] was catalytically competent to promote the hydrogenation of olefins (Figure 6A).28 The simple addition of hydrogen gas to [(Cp*)2U(Me)2] (5) effects the liberation of methane and formation of the active catalyst, namely, [(Cp*)2U(H)2] (1). The alkene can then insert into dihydride 1, generating a uranium bis-alkyl [(Cp*)2U(alkyl)2] (2), which, upon reaction with hydrogen gas, releases the reduced alkane product, thereby restoring the dihydride catalyst 1.

Figure 6.

(A) Marks’ model of catalytic olefin hydrogenation, which is thought to function through a sigma-bond metathesis mechanism; adapted from ref (28). (B) Cloke’s example of alkene hydrogenation using uranium(III) complex 3; adapted from ref (29).

Another particularly impressive example of olefin hydrogenation was presented by Cloke et al. in 2020, wherein the catalytic hydrogenation of ethylene was demonstrated under an atmosphere of hydrogen and ethylene.29 While no mechanistic details have been proposed, [U(Pn††)(Cp*)] (3) was capable of producing the dimer [{(Pn††)(Cp*)U}2(μ-C2H4)] (4) upon exposure to an atmosphere of ethylene gas (Figure 5B). Upon the reaction of 4 with dihydrogen, the release of ethane gas was observed along with regeneration of the active catalyst 3. This result is a very rare example of uranium catalysis featuring an oxidative addition/reductive elimination cycle using two uranium centers in close proximity to facilitate this formal two-electron process.

Lactone Polymerization

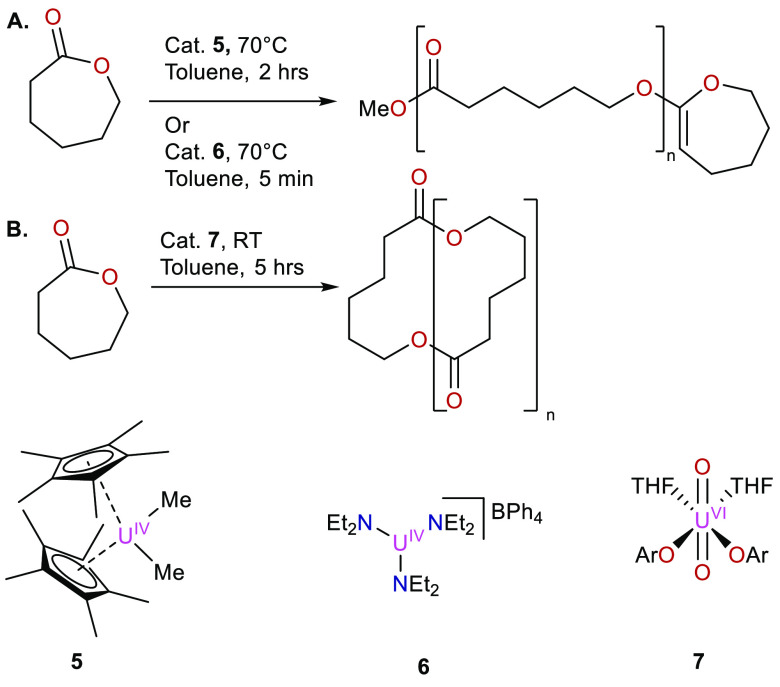

An early example of uranium catalyzed ring-opening polymerization of lactones was achieved in 2006 (Figure 7A).30 In this report, Eisen et al. demonstrated the competency of 5 to perform the polymerization of ε-caprolactone to yield polyesters. This reaction was found to be a living ring-opening metathesis polymerization (ROMP), capable of achieving 90% conversion at 70 °C in toluene over the course of 2 h with a catalyst ratio of 1 per 600 monomer units. Utilizing the “simple” uranium tris-amide [U(NEt2)3](BPh4) (6), the overall conversion could be increased to 100% and the reaction time reduced to about 5 min at 70 °C. This result was attributed to 6 being less sterically encumbered compared to 5. For both of these complexes, the polydispersity index (PDI) was low at 1.21 and 1.26, respectively, indicating both ends of the polymer were held in close proximity to the catalyst through weak interactions. The polymers formed were found to be linear.

Figure 7.

(A) Eisen’s linear polymerization of ε-caprolactone; adapted from ref (30). (B) Baker’s cyclic polymerization of ε-caprolactone using a uranyl complex; adapted from ref (31).

In 2013, the topic of lactone polymerization was revisited by Baker et al., this time using a uranyl bis-alkoxide [(ArO)2UO2] (7).31 Baker was able to show that this complex was proficient of polymerizing ε-caprolactone with comparable conversions (86%) with a catalyst ratio of 1 per 600 monomer units at room temperature in toluene. Unlike the reaction proposed by Eisen, however, this reaction proceeded by initial intramolecular ring opening, followed by intermolecular propagation of the polymerization. Interestingly, this reaction also demonstrated the formation of cyclic polymers rather than linear polymers, which was shown by Eisen (Figure 7B).

Oligomerization

Uranium(IV) complexes have also been documented for the oligomerization of alkynes, as early as 1995, when [(Cp*)2U(Me)2] (5) was found to catalyze the synthesis of alkyne trimers and dimers.32 It was found that, under catalytic conditions, reactions with tert-butyl-substituted alkynes resulted in oligomerization to form (noncyclic) trimers through path B (Figure 8A, red), while TMS- or phenyl-substituted alkynes preferred linear dimers through path A (Figure 6A, black). In 2015, Eisen et al. demonstrated that changing from [(Cp*)2U(Me)2] (5) to [(Me3Si)2U(κ2-(N,C)–CH2Si(CH3)2-N(SiMe3)] (8) allowed for cyclotrimerization to occur (Figure 4A, blue), which results in a statistical mixture of 1,2,4- and 1,3,5-arenes (Figure 8B) in the cases of phenyl acetylene and tert-butyl acetylene.33 It should be noted that TMS acetylene prefers to form linear dimers when treated with either 5 or 8.

Figure 8.

(A) Catalytic mechanism for alkyne dimer, trimer and cyclotrimerization reactions using uranium(IV) catalysts. (B) Distribution of products for each catalyst indicating different mechanisms for these reactions.

Hydroamination

Uranium-catalyzed hydroamination was shown by Eisen et al. in 1996, wherein it was demonstrated that 5 was capable of hydroamination of alkynes using primary amines (Figure 9A).34 In 2007, Marks established similar reactivity employing [(CGC)U(NMe2)2] (9) as a catalyst to promote intramolecular hydroamination with a surprisingly broad substrate scope, including alkenes, allenes, alkynes, and dienes (Figure 9B).35 Shortly after Marks’ report, Eisen et al. were able to further expand this chemistry to carbodiimides and an even larger number of E–H bonds, such as primary amines, alkynes, thiols, alcohols, and primary phosphines, using the simple tris-amido complex [U(N((SiMe3)2)3] (11) or the closely related [(Me3Si)2U(κ2-(N,C)–CH2Si(CH3)2–N(SiMe3))] (8).36 Following this preliminary result, these reactions have been further explored using N-heterocyclic imine ligands, using the catalyst [(BimMe,ArN)U(N(SiMe3)2)3] (10) (Figure 9C).37,38

Figure 9.

(A) Eisen’s example of catalytic hydroamination of alkynes; adapted from ref (34). (B) Marks’ blueprint for intramolecular hydroamination of tethered amines; adapted from ref (35). (C) Eisen’s work on catalytic reactions with various heteroallenes.

Hydrosilylation and Hydroboration

In 1999, Eisen et al. revealed the ability of 5 to function as a hydrosilylation catalyst for alkynes in the presence of phenyl silane.39 Under these conditions, the formation of mixtures of products was observed. The product distributions were highly dependent on the alkyne’s substituents, with less sterically bulky alkynes affording higher selectivity for the formation of Z-hydrosilylated alkenes. In contrast, bulky substituents were more selective toward the formation of terminal-hydrosilylated alkynes as well as hydrogenated alkenes (Figure 10A).

Figure 10.

(A) Eisen’s hydrosilylation of alkynes; adapted from ref (39). (B) Cantat’s display of the importance of the steric bulk of silanes on the selectivity of hydrosilylation versus homocoupling of ethers; adapted from ref (40). (C) Eisen’s demonstration of the hydroboration of carbodiimides using catalyst 10; adapted from ref (41). (D) Eisen’s hydroboration of internal ketones using catalyst 13; adapted from ref (42).

Cantat et al. were able to expand on this catalysis in 2019 using [UO2(OTf)2] (12) for the hydrosilylation of aldehydes (Figure 10B).40 Intriguingly, however, their studies revealed that while this process was tolerant of a large number of different functional groups, they were capable of driving the selectivity of this reaction through two different pathways to generate either silyl ethers or to allow for the synthesis of homocoupled ethers. Further, the selectivity of this reaction was determined to be dependent on both the identity and the concentration of the silane. The substrates generally preferred hydrosilylation when silanes with smaller substituents, for example, isopropyl, were used at higher concentrations. To contrast, larger substituents on these silanes, such as phenyl groups, formed ethers instead.

In 2018, Eisen et al. demonstrated the monohydroboration of aromatic and aliphatic carbodiimides with HBpin, using complex 10 at 0.02% catalyst loading, to produce hydroborated carbodiimides in greater than 99% yield.41 When examining this reactivity with asymmetric carbodiimides, hydroboration favored the carbon–nitrogen bond adjacent to the substituent with greater steric bulk (Figure 10C).41 When using [(L)U(N(SiMe3)2)3] 13 (L= 5,7-diisopropyl-5,7-dihydro-6H-dibenzo-[d,f][1,3]diazepin-6-imine) in 0.1% catalyst loading, hydroboration of dicyclohexyl ketone with HBpin occurred in greater than 99% yield (Figure 10D).42 This reaction is particularly notable given uranium’s high affinity for the formation of strong uranium–oxygen bonds as well as uranium’s documented ability to insert into the B–O bonds of HBpin.42

Processes Using External Reductants

Up until this point in this Perspective, we have discussed the use of “redox neutral” reactions in uranium catalysis. Despite the inherently high reduction potentials of most high-valent uranium complexes, the regeneration of low-valent reactive species through reduction of oxidized uranium species is possible, though it typically requires the use of strong metal reductants (Li, Na, K, Cs, etc.) or the application of an outside voltage via an electrode. In catalysis, these methods using outside reductants allow for the regeneration of catalytically active, low-valent complexes from higher valence, catalytically inactive complexes.

In 2016, our group developed the first uranium-catalyzed water reduction process using a uranium(III) electrocatalyst, wet THF, and a glassy carbon electrode.43 During these studies, tris-aryloxide [UIII((OArAd,Me)3mes)] (14) was employed as a catalyst at a potential of −3.25 V (vs [Fe(Cp)2]0/+) to catalytically produce dihydrogen from water. The onset potential of 14 was determined to be −2.75 V vs [Fe(Cp)2]0/+, which was 0.25 V higher than the onset potential of a platinum electrode and 0.50 V lower than that of a bare glassy carbon electrode, which had an onset potential of −3.25 V vs [Fe(Cp)2]0/+. Remarkably, catalyst 14 exhibits nearly 100% faradaic efficiency. In 2018, we revisited this topic with new mechanistic studies on this reaction (Figure 11).44 According to these studies, initially, water coordinates to the trivalent catalyst to furnish [((Ad,MeArO)3mes)UIII(OH2)], which, subsequently, inserts into one of the water’s hydrogen–oxygen bonds to produce the uranium(V) hydroxo hydrido species, [((Ad,MeArO)3mes)UV(H)(OH)], via a crucial oxidative addition reaction. This EPR-active, pentavalent compound then engages in a thermal transformation to release 1 equiv of H2, thereby, generating a uranium(V) oxo complex, [((Ad,MeArO)3mes)UV(O)], which undergoes comproportionation through reaction with water and 14 to yield 2 equiv of the hydroxide [((Ad,MeArO)3mes)UIV(OH)]. Finally, electrochemical one-electron reduction forms the negatively charged [((Ad,MeArO)3mes)UIII(OH)]− that re-enters the catalytic cycle with the release of the axial hydroxide ligand, thus regenerating catalyst 14.

Figure 11.

Our proposed electrocatalytic cycle for the production of H2 via water reduction, using the arene-supported uranium(III) catalyst [UIII((Ad,MeArO)3mes)] (14). Crucial steps include the oxidative addition of an O–H bond from H2O and the cleavage of the U–OH bond with elimination of OH–; adapted from ref (44).

Independent synthesis and characterization of the uranium(V) oxide complex indicated the importance of the axially positioned arene ring, which provides additional stability through δ-backbonding interactions with the uranium ion, hinting at the crucially important redox-noninnocence of the arene ring in this species. This was further proven by comparison of 14 with the reactivity of the [UIII((Ad,MeArO)3tacn)] analogue, in which the redox-active arene anchor is substituted for the redox-inactive, macrocyclic triazacyclononane (tacn). This species also stabilizes all relevant intermediates of the above-mentioned catalytic cycle, namely, the U(IV) hydroxide and the U(V) oxide, but is catalytically inactive. The latter example highlights the preference for uranium complexes to engage in one-electron transfer chemistry, while two electrons are required for H2 production. Clearly, the redox-active chelate overcomes the uranium ion’s constraint.

A closely related study was published in 2019, by Pal et al., using a U(VI) uranyl species.45 In this work, the authors were able to achieve 84% faradaic efficiency at a potential of −1.1 V (vs. reversible hydrogen electrode) with a TOF of 384 h–1 in water, buffered at pH 7. This catalyst was also capable of functioning using a dye-sensitized TiO2-electrode, irradiated with a 450 W Xe arc lamp rather than a conventional FTO electrode (Figure 12).

Figure 12.

Proposed photocatalytic cycle for Pal’s uranium-catalyzed generation of hydrogen; adapted from ref (45).

Very recently, in 2020, Arnold et al. were able to demonstrate a dinuclear uranium complex capable of the challenging six-electron reduction of molecular dinitrogen to ammonia (Figure 13).46 In this work, a dinuclear uranium complex was synthesized using an arene-anchored bis-aryloxide ligand to generate the diuranium(IV/IV) “letterbox” complex, [U(mTP)]2 (15), which could then be reduced using 4 equiv of KC8 to form the hydrazide complex K4[{(mTP)U}2(μ-N2H2)] (16). Dimeric 15 was also found to be competent in the formation of both ammonia and HMDS upon treatment with an excess of KC8 as a reductant under an atmosphere of dinitrogen. The authors reported that 15 produced 0.78 molar equiv of ammonia under these conditions. The performance and yield are comparable to what Mazzanti et al. reported (0.77 molar equiv, upon exposure to 20 equiv of HNEt3BPh4).8 If the species was treated with 60 equiv of SiMe3Cl and 30 equiv of HNEt3BPh4, 6.4 molar equiv of HMDS could be produced. While the demonstrated yield is poor in both cases, it echoes uranium’s surprising ability to function as a molecular catalyst in the industrially highly relevant Haber–Bosch catalysis (vide supra), a result that has inspired uranium-based molecular chemistry for decades. While this outcome is indeed remarkable, it should be noted that stoichiometric metal reductants, such as potassium, sodium, or lithium, are not suitable for large-scale catalysis; lithium metal on its own, for example, is known to stoichiometrically reduce molecular nitrogen as is aluminum (more precisely, a mixture of alumina or calcined bauxite with carbon), allowing for the production of ammonia from hydrolysis of AlN through the Serpek process.47

Figure 13.

Arnold’s dinuclear [U(mTP)]2 complex 15 capable of the production of ammonia; adapted from ref (46).

Development of Uranium-Centric Synthetic Cycles

Typically, when describing a catalytic process, one thinks of a closed flask, wherein reagents are added in the presence of a catalyst to perform a specific transformation. In the final paragraphs of this Perspective, we will discuss “recyclable” uranium reactions, wherein a uranium species can facilitate an interesting, possibly industrially relevant but stoichiometric reaction to produce a new compound, for example, the formation of carbon monoxide from carbon dioxide, leaving the uranium complex in a deactivated state. Subsequently, the deactivated uranium species can be isolated from the reaction mixture and restored to its active state to engage in further reactions. Clearly, these reactions are not catalytic, and “re-activation” typically involves harsh (industrially irrelevant) conditions and strong reductants (vide supra). However, they do allow for the cycling of an active species in a (stoichiometric) transformation. Additionally, while these uranium complexes cannot engage in catalytic turnover, their ability to be cycled through a stoichiometric process multiple times may lay the groundwork for new catalytic reactions; possibly by coupling to an electrochemical or even photoelectrochemical process.

Within the area of “closed-synthetic-cycle” developments for uranium-based small molecule transformations, we and others have made several contributions. In 2006, we demonstrated the synthesis of a carbodiimide species using trimethylsilyl azide (TMS azide) and methyl isocyanide (Figure 14).48 Initial treatment of [U((OArAd,t-Bu)3tacn)] (17) with TMS azide produced the imido complex [((Ad,t-BuArO)3tacn)U(NTMS)] (Figure 14). Subsequent reaction of [((Ad,t-BuArO)3tacn)U(NTMS)] with methyl isocyanide produced the terminally bound carbodiimide complex [((Ad,t-BuArO)3tacn)U(N=C=NTMS)] and released (SiMe3)2. Finally, [((Ad,t-BuArO)3tacn)U(N=C=NTMS)] could be treated with dichloromethane or methyl iodide to release the carbodiimides ClCH2N=C=NTMS and CH3N=C=NCH3, respectively, with concomitant formation of the corresponding halide complexes [((Ad,t-BuArO)3tacn)U(X)]. These halides could be reduced in the presence of an excess of Na/Hg to regenerate 17, thus closing a cycle in which a nitrogen atom is transferred from a uranium imide to a nitrile in a multiple-bond metathesis reaction that ultimately forms and releases carbodiimides via successive one-electron steps.

Figure 14.

Closed-synthetic-cycle, demonstrating the synthesis of carbodiimides using the uranium(III) species [U((OArAd,tBu)3tacn)] 17; adapted from ref (48).

In 2011, Cloke et al. demonstrated a synthesis of methoxytrimethylsilane (Figure 15) through the use of [U(Cp*)(C8H6{Sii-Pr3-1,4}2)] (18).49 When 1 equiv of CO was added to 18, followed by the addition of 2 equiv of hydrogen gas, [(C8H6{Sii-Pr3-1,4}2)(Cp*)U(OCH3)] was formed, which releases methoxytrimethylsilane through the addition of TMSOTf. This generates the triflate [(C8H6{Sii-Pr3-1,4}2)(Cp*)U(OTf)], which could be reduced with K/Hg to regenerate 18. This reaction is reminiscent of Fischer–Tropsch catalysis,50 where CO is transformed into liquid fuels. It is intriguing to imagine a uranium-based tandem catalytic system in which one catalyst reduces CO2 to CO (vide infra) and another one transforms CO to methanol.

Figure 15.

Cloke’s synthetic cycle for the production of methoxytrimethylsilane from CO and H2 gas; adapted from ref (49).

In 2012, our group presented a closed-synthetic cycle in which CO2 was converted to carbon monoxide and carbonate with an excess of potassium graphite, KC8 (Figure 16).51 Upon treatment of [U((OArNeop,Me)3tacn)] (19) with an excess of CO2, the μ-oxo-bridged complex [{((Neop,MeArO)3tacn)U}2(μ-O)] is formed with the release of 1 equiv of CO. While the tert-butyl derivative [{((t-Bu,MeArO)3tacn)U}2(μ-O)] is inert, the neo-pentyl-analogue U(IV/IV) μ-oxo is capable of reacting further with CO2 to yield the carbonate [{((Me,NeopArO)3tacn)U}2(μ-CO3)]. Over a bed (an excess) of KC8, the carbonate is released and the trivalent precursor 19 engages in subsequent cycles of CO2 reduction to CO and transformation to CO32–. This reaction is continued until a tetranuclear uranium carbonate cluster precipitates from the reaction solution.

Figure 16.

Our example of CO2 reduction to CO and CO32–using a tris-aryloxide uranium(III) complex; adapted from ref (51).

Finally, an inspiring example of CO activation was offered by Liddle et al. in 2012, which produced alkyne diols using [U(trenDMSB)] (20, Figure 17).52 The uranium-based transformation of CO to ynediolates is not unprecedented,53,54 but treatment of 20 with an atmosphere of CO results in the formation of [{(trenDMSB)U}2(μ-OCCO)], which releases one-half of a molar equivalent of alkyne upon addition of two stoichiometric equivalents of TMS iodide, thereby producing the halide [(trenDMSB)U(I)] that could then be reduced with potassium metal to restore [U(trenDMSB)]. The resulting bis(trimethylsiloxy) acetylene was found to be unstable, both neat and in solution, undergoing cyclization to form 3,4-dimethoxy-5-(hydroxymethyl)-5-methyl-2(5H)-furanone.

Figure 17.

Liddle’s demonstration of CO coupling and transformation to 2(5H)-furanone using the [U(trenDMSB)]-system; adapted from ref (52).

Outlook

Over the course of this Perspective, we have discussed advances in the development of uranium catalysts. Currently, the majority of uranium-based catalysts operate through redox-neutral sigma-bond metathesis mechanisms at mid- to high-valent uranium centers. These reactions have demonstrated a surprising breadth of reactivity, including polymerization, group transfer, and hydrogenation reactivities. It is evident that minor changes in complex/catalyst design allow for fundamentally differing reactivity patterns. For example, Eisen and co-workers revisited uranium-catalyzed olefin oligomerization reactivity and demonstrated that upon simply changing from [(Cp*)2U(Me)2] (5) to [(Me3Si)2U(κ2-(N,C)–CH2Si(CH3)2–N(SiMe3)] (8) the formation of cyclic trimers was favored over linear trimers. A similar effect is seen in the polymerization of ε-caprolactone, where upon changing from 5 to [(ArO)2UO2] (12) cyclic polymers were found to be favored over linear polymers. Given the dearth of catalytic reactions known for uranium, expansion of the available reactivities in this area is very likely.

While the use of sigma-bond metathesis has allowed for great advances in uranium catalysis and these reactions have shown an impressive range of different reactivities, we imagine the future of uranium catalysis to be a fusion of electro- or even photoelectrochemistry and molecular uranium chemistry. The uranium(III/IV), and to lesser extent uranium(V/VI), redox couples already serve as workhorses of modern uranium coordination and small molecule activation chemistry. Given the broad reactivity associated with these low-valent uranium complexes, including the so far stoichiometric small molecule activations of molecular dinitrogen, carbon dioxide, and carbon monoxide, it is not too much of a leap to imagine that continued progress in chemical catalysis with these complexes would provide a benefit for modernization of uranium catalysis. While chemical catalysis has largely been overlooked for low-valent uranium species, due to the inherent difficulty associated with the reduction of high-valent uranium, the application of an electrode allows for the efficient production of electron equivalents at high reduction potentials. Extrapolating outward, it appears logical that electrocatalytic methods of catalyst reduction could be used to replace expensive, highly reactive metal reductants. Given the growing importance of renewably sourced feedstocks, the ability to convert inert, abundant molecules into chemically relevant species will continue to play a large role in modern synthetic chemistry. The uranium-mediated reduction of carbon dioxide to carbon monoxide has already been documented stoichiometrically, and so has the stoichiometric reduction of carbon monoxide to organic synthons and liquid fuels. Molecular uranium complexes have even been shown to form ammonia from molecular dinitrogen. Using the existing reactivity known for uranium as a roadmap, continued development of uranium catalysis for application in renewable energy systems appears likely in the near future.

Acknowledgments

Friedrich-Alexander-University of Erlangen-Nürnberg (FAU) and the Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (f-Char, BMBF support code 02NUK059E) are gratefully acknowledged for generous funding.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Löffler S. T.; Meyer K.. Actinides. In Comprehensive Coordination Chemistry; Elsevier, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019. 10.1016/B978-0-12-409547-2.14754-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roussel P.; Scott P. Complex of Dinitrogen with Trivalent Uranium. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998, 120, 1070–1071. 10.1021/ja972933+. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Odom A. L.; Arnold P. L.; Cummins C. C. Heterodinuclear Uranium/Molybdenum Dinitrogen Complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998, 120, 5836–5837. 10.1021/ja980095t. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haber F.Verfahren Zur Herstellung von Ammoniak Durch Katalytische Vereinigung von Stickstoff Und Wasserstoff, Zweckmäßig Unter Hohem Druch. DE229126, 1909.

- Evans W. J.; Kozimor S. A.; Ziller J. W. A Monometallic f Element Complex of Dinitrogen: (C5Me 5)3U(H1-N2). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 14264–14265. 10.1021/ja037647e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King D. M.; Tuna F.; McInnes E. J. L.; McMaster J.; Lewis W.; Blake A. J.; Liddle S. T. Isolation and Characterization of a Uranium(VI)-Nitride Triple Bond. Nat. Chem. 2013, 5, 482–488. 10.1038/nchem.1642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatelain L.; Louyriac E.; Douair I.; Lu E.; Tuna F.; Wooles A. J.; Gardner B. M.; Maron L.; Liddle S. T. Terminal Uranium(V)-Nitride Hydrogenations Involving Direct Addition or Frustrated Lewis Pair Mechanisms. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 337. 10.1038/s41467-019-14221-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falcone M.; Chatelain L.; Scopelliti R.; Živković I.; Mazzanti M. Nitrogen Reduction and Functionalization by a Multimetallic Uranium Nitride Complex. Nature 2017, 547, 332–335. 10.1038/nature23279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barluzzi L.; Falcone M.; Mazzanti M. Small Molecule Activation by Multimetallic Uranium Complexes Supported by Siloxide Ligands. Chem. Commun. 2019, 55, 13031–13047. 10.1039/C9CC05605J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan J. G.; Andersen R. A.; Robbins J. L. Preparation of the First Molecular Carbon Monoxide Complex of Uranium, (Me3SiC5H4)3UCO. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1986, 108, 335–336. 10.1021/ja00262a046. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parry J.; Carmona E.; Coles S.; Hursthouse M. Synthesis and Single Crystal X-Ray Diffraction Study on the First Isolable Carbonyl Complex of an Actinide, (C5Me4H)3U(CO). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995, 117, 2649–2650. 10.1021/ja00114a030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Summerscales O. T.; Cloke F. G. N.; Hitchcock P. B.; Green J. C.; Hazari N. Reductive Cyclotrimerization of Carbon. Science 2006, 311, 829–831. 10.1126/science.1121784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsoureas N.; Summerscales O. T.; Cloke F. G. N.; Roe S. M. Steric Effects in the Reductive Coupling of CO by Mixed-Sandwich Uranium(III) Complexes. Organometallics 2013, 32, 1353–1362. 10.1021/om301045k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Castro-Rodriguez I.; Nakai H.; Zakharov L. N.; Rheingold A. L.; Meyer K. A Linear, O-Coordinated H1-CO2 Bound to Uranium. Science 2004, 305, 1757–1759. 10.1126/science.1102602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro-Rodriguez I.; Meyer K. Carbon Dioxide Reduction and Carbon Monoxide Activation Employing a Reactive Uranium(III) Complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 11242–11243. 10.1021/ja053497r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox A. R.; Bart S. C.; Meyer K.; Cummins C. C. Towards Uranium Catalysts. Nature 2008, 455, 341–349. 10.1038/nature07372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behera N.; Sethi S. Unprecedented Catalytic Behavior of Uranyl(VI) Compounds in Chemical Reactions. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2021, 2021, 95–111. 10.1002/ejic.202000611. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- West J. G.; Bedell T. A.; Sorensen E. J. The Uranyl Cation as a Visible-Light Photocatalyst for C(Sp 3)–H Fluorination. Angew. Chem. 2016, 128, 9069–9073. 10.1002/ange.201603149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldo L.; Merli D.; Fagnoni M.; Ravelli D. Visible Light Uranyl Photocatalysis: Direct C-H to C-C Bond Conversion. ACS Catal. 2019, 9, 3054–3058. 10.1021/acscatal.9b00287. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y.; Rizvi S. A. e. A.; Hu D.; Sun D.; Gao A.; Zhou Y.; Li J.; Jiang X. Selective Late-Stage Oxygenation of Sulfides with Ground-State Oxygen by Uranyl Photocatalysis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 13499–13506. 10.1002/anie.201906080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold P. L.; Purkis J. M.; Rutkauskaite R.; Kovacs D.; Love J. B.; Austin J. Controlled Photocatalytic Hydrocarbon Oxidation by Uranyl Complexes. ChemCatChem 2019, 11, 3786–3790. 10.1002/cctc.201900037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muller P. Glossary of Terms Used in Physical Organic Chemistry (IUPAC Recommendations 1994). Pure Appl. Chem. 1994, 66, 1077–1184. 10.1351/pac199466051077. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hartwig J. F.Transition Metal-Catalyzed Coupling Reactions. In Organotransition Metal Chemistry: From Bonding to Catalysis; University Science Books: Mill Valley, CA, 2010; pp 877–965. [Google Scholar]

- Lu E.; Liddle S. T. Uranium-Mediated Oxidative Addition and Reductive Elimination. Dalton Trans. 2015, 44, 12924–12941. 10.1039/C5DT00608B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seyam A. M. Thermal Studies of “Dialkyldioxouranium(VI).. Inorg. Chim. Acta 1982, 58, 71–74. 10.1016/S0020-1693(00)90225-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kraft S. J.; Fanwick P. E.; Bart S. C. Carbon-Carbon Reductive Elimination from Homoleptic Uranium(IV) Alkyls Induced by Redox-Active Ligands. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 6160–6168. 10.1021/ja209524u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner B. M.; Kefalidis C. E.; Lu E.; Patel D.; McInnes E. J. L.; Tuna F.; Wooles A. J.; Maron L.; Liddle S. T. Evidence for Single Metal Two Electron Oxidative Addition and Reductive Elimination at Uranium. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1898. 10.1038/s41467-017-01363-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagan P. J.; Manriquez J. M.; Maatta E. A.; Seyam A. M.; Marks T. J. Synthesis and Properties of Bis(Pentamethylcyclopentadienyl) Actinide Hydrocarbyls and Hydrides. A New Class of Highly Reactive f-Element Organometallic Compounds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1981, 103, 6650–6667. 10.1021/ja00412a021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tsoureas N.; Maron L.; Kilpatrick A. F. R.; Layfield R. A.; Cloke F. G. N. Ethene Activation and Catalytic Hydrogenation by a Low-Valent Uranium Pentalene Complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 89–92. 10.1021/jacs.9b11929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnea E.; Moradove D.; Berthet J. C.; Ephritikhine M.; Eisen M. S. Surprising Activity of Organoactinide Complexes in the Polymerization of Cyclic Mono- And Diesters. Organometallics 2006, 25, 320–322. 10.1021/om050966p. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Walshe A.; Fang J.; Maron L.; Baker R. J. New Mechanism for the Ring-Opening Polymerization of Lactones? Uranyl Aryloxide-Induced Intermolecular Catalysis. Inorg. Chem. 2013, 52, 9077–9086. 10.1021/ic401275e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straub T.; Haskel A.; Eisen M. S. Organoactinide-Catalyzed Oligomerization of Terminal Acetylenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995, 117, 6364–6365. 10.1021/ja00128a029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Batrice R. J.; McKinven J.; Arnold P. L.; Eisen M. S. Selective Oligomerization and [2 + 2 + 2] Cycloaddition of Terminal Alkynes from Simple Actinide Precatalysts. Organometallics 2015, 34, 4039–4050. 10.1021/acs.organomet.5b00455. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haskel A.; Straub T.; Eisen M. S. Organoactinide-Catalyzed Intermolecular Hydroamination of Terminal Alkynes. Organometallics 1996, 15, 3773–3775. 10.1021/om960182z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stubbert B. D.; Marks T. J. Constrained Geometry Organoactinides as Versatile Catalysts for the Intramolecular Hydroamination/Cyclization of Primary and Secondary Amines Having Diverse Tethered C-C Unsaturation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 4253–4271. 10.1021/ja0665444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batrice R. J.; Eisen M. S. Catalytic Insertion of E-H Bonds (E = C, N, P, S) into Heterocumulenes by Amido-Actinide Complexes. Chem. Sci. 2016, 7, 939–944. 10.1039/C5SC02746B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karmel I. S. R.; Tamm M.; Eisen M. S. Actinide-Mediated Catalytic Addition of E-H Bonds (E = N, P, S) to Carbodiimides, Isocyanates, and Isothiocyanates. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 12422. 10.1002/anie.201502041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H.; Fridman N.; Tamm M.; Eisen M. S. Addition of E-H (E = N, P, C, O, S) Bonds to Heterocumulenes Catalyzed by Benzimidazolin-2-Iminato Actinide Complexes. Organometallics 2017, 36, 3896–3903. 10.1021/acs.organomet.7b00502. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dash A. K.; Wang J. Q.; Eisen M. S. Catalytic Hydrosilylation of Terminal Alkynes Promoted by Organoactinides. Organometallics 1999, 18, 4724–4741. 10.1021/om990655c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Monsigny L.; Thuéry P.; Berthet J. C.; Cantat T. Breaking C-O Bonds with Uranium: Uranyl Complexes as Selective Catalysts in the Hydrosilylation of Aldehydes. ACS Catal. 2019, 9, 9025–9033. 10.1021/acscatal.9b01408. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H.; Kulbitski K.; Tamm M.; Eisen M. S. Organoactinide-Catalyzed Monohydroboration of Carbodiimides. Chem. - Eur. J. 2018, 24, 5738–5742. 10.1002/chem.201705987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghatak T.; Makarov K.; Fridman N.; Eisen M. S. Catalytic Regeneration of a Th-H Bond from a Th-O Bond through a Mild and Chemoselective Carbonyl Hydroboration. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 11001–11004. 10.1039/C8CC05030A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halter D. P.; Heinemann F. W.; Bachmann J.; Meyer K. Uranium-Mediated Electrocatalytic Dihydrogen Production from Water. Nature 2016, 530, 317–321. 10.1038/nature16530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halter D. P.; Heinemann F. W.; Maron L.; Meyer K. The Role of Uranium-Arene Bonding in H2O Reduction Catalysis. Nat. Chem. 2018, 10, 259–267. 10.1038/nchem.2899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh S.; Srivastava A. K.; Govu R.; Pal U.; Pal S. Diuranyl(VI) Complex and Its Application in Electrocatalytic and Photocatalytic Hydrogen Evolution from Neutral Aqueous Medium. Inorg. Chem. 2019, 58, 14410–14419. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.9b01726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold P. L.; Ochiai T.; Lam F. Y. T.; Kelly R. P.; Seymour M. L.; Maron L. Metallacyclic Actinide Catalysts for Dinitrogen Conversion to Ammonia and Secondary Amines. Nat. Chem. 2020, 12, 654–659. 10.1038/s41557-020-0457-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards J. W. The Serpek Process for the Manufacture of Aluminium Nitride. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 1913, 5, 335–337. 10.1021/ie50052a024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Castro-Rodríguez I.; Nakai H.; Meyer K. Multiple-Bond Metathesis Mediated by Sterically Pressured Uranium Complexes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2006, 45, 2389–2392. 10.1002/anie.200501667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey A. S. P.; Cloke F. G. N.; Coles M. P.; Maron L.; Davin T. Facile Conversion of CO/H2 into Methoxide at a Uranium(III) Center. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 6881–6883. 10.1002/anie.201101509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dry M. E. Commercial Conversion of Carbon Monoxide to Fuels and Chemicals. J. Organomet. Chem. 1989, 372, 117–127. 10.1016/0022-328X(89)87082-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt A. C.; Nizovtsev A. V.; Scheurer A.; Heinemann F. W.; Meyer K. Uranium-Mediated Reductive Conversion of CO2 to CO and Carbonate in a Single-Vessel, Closed Synthetic Cycle. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 8634–8636. 10.1039/c2cc34150f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner B. M.; Stewart J. C.; Davis A. L.; McMaster J.; Lewis W.; Blake A. J.; Liddle S. T. Homologation and Functionalization of Carbon Monoxide by a Recyclable Uranium Complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2012, 109, 9265–9270. 10.1073/pnas.1203417109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey A. S.; Cloke F. G. N.; Hitchcock P. B.; Day I. J.; Green J. C.; Aitken G. Mechanistic Studies on the Reductive Cyclooligomerisation of CO by U(III) Mixed Sandwich Complexes; the Molecular Structure of [U(η-C 8H6{SiiPr3–1,4}2)(η- Cp*)]2(μ-H1:H1-C 2O2). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 13816–13817. 10.1021/ja8059792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansell S. M.; Kaltsoyannis N.; Arnold P. L. Small Molecule Activation by Uranium Tris(Aryloxides): Experimental and Computational Studies of Binding of N2, Coupling of CO, and Deoxygenation Insertion of CO2 under Ambient Conditions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 9036–9051. 10.1021/ja2019492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]