Abstract

Premature translation termination codon (PTC)-mediated effects on nuclear RNA processing have been shown to be associated with a number of human genetic diseases; however, how these PTCs mediate such effects in the nucleus is unclear. A PTC at nucleotide (nt) 2018 that lies adjacent to the 5′ element of a bipartite exon splicing enhancer within the NS2-specific exon of minute virus of mice P4 promoter-generated pre-mRNA caused a decrease in the accumulated levels of P4-generated R2 mRNA relative to P4-generated R1 mRNA, although the total accumulated levels of P4 product remained the same. This effect was seen in nuclear RNA and was independent of RNA stability. The 5′ and 3′ elements of the bipartite NS2-specific exon enhancer are redundant in function, and when the 2018 PTC was combined with a deletion of the 3′ enhancer element, the exon was skipped in the majority of the viral P4-generated product. Such exon skipping in response to a PTC, but not a missense mutation at nt 2018, could be suppressed by frame shift mutations in either exon of NS2 which reopened the NS2 open reading frame, as well as by improvement of the upstream intron 3′ splice site. These results suggest that a PTC can interfere with the function of an exon splicing enhancer in an open reading frame-dependent manner and that the PTC is recognized in the nucleus.

Premature termination codons (PTCs) decrease the accumulated levels of most known mRNAs in which they reside (reviewed in reference 28). In the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the UPF genes are involved in the degradation of PTC-containing RNAs in the cytoplasm (review in reference 37). Similarly, the SMG proteins of Caenorhabditis elegans are required for the rapid decay of PTC-containing unc-54 myosin heavy-chain mRNAs (reviewed in reference 41).

PTC-mediated effects on nuclear RNA processing have been shown to be associated with a number of human genetic diseases (reviewed in references 28 and 29); however, how PTCs mediate such effects in the nucleus is still unclear. In mammalian cells, PTCs have been shown to decrease the levels of nucleus-associated mRNAs by a posttranscriptional mechanism, often attributed to mRNA decay (3, 6, 9, 28, 45). Experiments done with PTCs in the human TPI gene suggest that nonsense-mediated decay (NMD) occurs on a fully spliced nucleus-associated mRNA molecule, possibly during mRNA export to the cytoplasm (4, 5, 9, 28).

There is also increasing evidence that PTCs may affect mammalian RNA processing events other than decay. For example, several instances of PTC-associated exon skipping have been described (15, 19, 28, 33). Perhaps the best-studied example is skipping of the 66-nucleotide (nt) exon 51 of fibrillin FBN1 RNA, which was detected when nonsense but not missense mutations were present within this exon, which was independent of protein synthesis, and for which normal splicing was restored when the nonsense codon was shifted out of frame with the initiation codon (14, 23). Retention of introns upstream of PTC-containing exons has also been reported for P4-generated RNAs of the parvovirus minute virus of mice (MVM) (32) and for mouse immunoglobulin kappa light-chain (Igκ)RNA (26). PTCs have also been reported, in one instance, to inhibit splicing of Igκ RNA in vitro in a manner independent of protein synthesis (1). These observations have led to the suggestion, still controversial, that PTCs may affect splice site choice (28), implying that the template for nonsense-codon mediated events may, at least in some cases, be a partially spliced or unspliced mRNA, and further suggesting that recognition of PTCs within pre-mRNAs may occur in the nucleus before or concomitant with splicing (47).

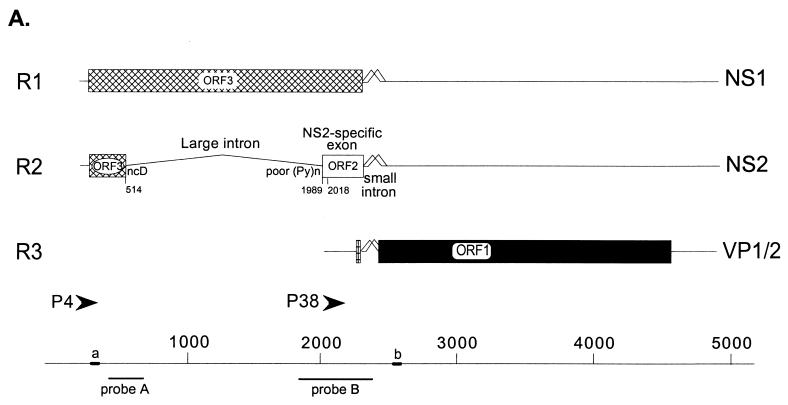

The parvovirus MVM is organized into two overlapping transcription units (Fig. 1A) (2, 10, 39). Transcripts R1 and R2 are generated from a promoter (P4) at map unit 4 and encode the viral nonstructural proteins NS1 and NS2, respectively, while the R3 transcripts are generated from a promoter (P38) at map unit 38 and encode the viral capsid proteins (12, 39). Both NS1 and NS2 play essential roles in viral replication and cytotoxicity (13), and so maintenance of their relative steady-state levels, which is controlled at least partially by alternative splicing (40), is critical to the MVM life cycle. All MVM mRNAs generated during infection or following transfection are very stable (43). The alternative splicing of MVM pre-mRNAs is accomplished solely by the interactions between cellular factors and viral cis-acting signals (40).

FIG. 1.

A PTC nt 2018 in the NS2-specific exon does not target R2 mRNA for nuclear degradation in vivo. (A) Genetic map of MVM. The three major transcript classes and protein-encoding ORFs are shown. The two promoters (P4 and P38) are indicated by arrows. The large intron, small intron, and NS2-specific exon are indicated. The nonconsensus donor (ncD) and the poor polypyrimidine tract [poor (Py)n] of the large intron are also shown. The position of the PTC mutation at nt 2018 within the NS2-specific exon is indicated; the mutant sequence is shown in Fig. 2A. The bottom diagram shows nucleotide locations, the two probes (A [nt 385 to 650] and B [nt 1854 to 2378]) used for RNase protection assays, and the two primers (a [nt 326 to 345]) and (b [nt 2557 to 2538]) used for RT-PCR as described in Materials and Methods. (B) RNase protection analysis, using probe B, of either total, nuclear, or cytoplasmic RNA generated by A9 cells infected with WT MVM virus, infected with 2018TAA virus, or mock infected, as designated above each lane. The identities of the protected bands are shown on the left and described in Materials and Methods. NUCLEAR (+DRB) and CYTOPLASMIC (+DRB), nuclear and cytoplasmic RNAs, respectively, collected 0.5 and 5 h after cells were treated with DRB (40 μg/ml), which was added 24 h after infection with WT MVM virus, infection with 2018TAA virus, or mock infection, as designated above each lane; TOTAL 0.5 h, total RNA isolated 0.5 h after cells were either treated with 40 μg of DRB per ml (+DRB) or left untreated (−DRB), which demonstrated that DRB did indeed inhibit transcription: the absence of unspliced R1 (R1un) and unspliced R3 (R3un) in total RNA isolated 0.5 h after treatment indicated that minimal (if any) new P4 or P38-directed transcription occurred after exposure to DRB. All transcripts were spliced to mature mRNA within 0.5 h of such treatment, as shown earlier (32, 43). RNA from equal cell equivalents was protected for all samples show. The average accumulated ratios of R2 relative to R1, as well as the average accumulated ratios of total P4 product (R2+R1) versus total P38 product (R3), in each RNA, as determined by phosphorimager analysis of duplicate experiments, are summarized in Table 1. The relative ratios of R1 and R2 in total, nuclear, and cytoplasmic RNAs were the same for RNA isolated either immediately after addition of DRB (i.e., 0 h) or 0.5 h after addition (data not shown). Nuclear RNA contains unspliced R1 and R3, which is absent from cytoplasmic RNA (32, 43)). Nuclear fractions were preparations were determined to be >95% pure as explained in Materials and Methods.

There are two types of introns in MVM P4-generated transcripts (40) (Fig. 1A). An overlapping downstream small intron, which undergoes an unusual pattern of overlapping alternative splicing using two donors (D1 and D2) and two acceptors (A1 and A2) (20), is located between nt 2280 and 2399 and is common to both P4- and P38-generated transcripts. An upstream large intron, located between nt 514 and 1989, is additionally excised from a subset of P4-generated pre-mRNAs to generate R2 mRNA. This upstream intron utilizes a nonconsensus donor at nt 514 and has a weak polypyrimidine tract at its 3′ splice site (48).

The NS2-specific exon is a 290-nt alternatively spliced exon which is translated in two open reading frames (ORFs). In singly spliced R1, this region utilizes ORF3 to encode NS1; in doubly spliced R2, this exon utilizes ORF2 to encode NS2 (Fig. 1A). Efficient inclusion of the NS2-specific exon as an internal exon in vivo, and consequent excision of the upstream large intron from P4-generated pre-mRNA to generate R2, requires an internally redundant, bipartite exon splicing enhancer (ESE) comprised of 5′ and 3′ elements within the NS2-specific exon (18).

We have previously shown that PTCs in either the first exon (NS1/NS2 common exon) or second exon (the NS2-specific exon) of R2 (Fig. 1A) caused a decrease in the accumulated levels of R2 relative to R1, although the total accumulated levels of R1 plus R2 remained the same (32). This decrease was the consequence of the artificially introduced translation termination signal acting in cis rather than in the absence of a functional viral gene product and was shown for a PTC in the NS2-specific exon at nt 2018 to be evident in nuclear RNA and independent of stability of total RNA (32). Here we have demonstrated that the PTC at nt 2018, which lies one nucleotide downstream of the 5′ element of the bipartite ESE within the NS2-specific exon, interfered with the excision of the upstream large intron in an ORF-dependent manner. This effect was evident in both nuclear and cytoplasmic RNA, yet the nonsense mutation had no effect on either the nuclear or cytoplasmic stability of either R1, R2, or the total P4 product (R1+R2). Further, when combined with a deletion of the 3′ element of the bipartite NS2-specific exon enhancer, the PTC at nt 2018 prevented efficient inclusion of the NS2-specific exon, also in an ORF-dependent manner. Our results are consistent with a model in which the PTC at nt 2018 can interfere with the ability of the bipartite ESE to strengthen interactions at the upstream intron polypyrimidine tract in an ORF-dependent manner and suggest that this PTC is recognized in the nucleus.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mutant construction.

Construction of pΔD1/2, pΔSX, pΔXP, pΔPH, pΔHS, pΔSX+ΔHS pCSDΔSX+ΔHS, p4TΔSX+ΔHS, and p2018TAA has been previously described (18, 32, 48).

Mutants p2018CAA, pfs(2011)2018TAA, pfs(2011)2018CAA, pfs(505), p1T2018TAA, p2T2018TAA, and p4T2018TAA were constructed by M13-based oligonucleotide mutagenesis as previously described (31). Mutant oligonucleotides were homologous to the viral DNA except at the nucleotides which were to be altered or deleted. The changes made in p2018CAA, p1T2018TAA, p2T2018TAA, and p4T2018TAA are shown in Fig. 2A. The frameshift at nt 2011 in mutants pfs(2011)2018TAA, and pfs(2011)2018CAA was made by deleting a single nucleotide at position 2011, while the frameshift at nt 505 in the mutant pfs(505) was made by deleting a single nucleotide at position 505. All final clones of the above mutants were sequenced to confirm that only the desired mutations were introduced. All additional mutants were made by combining these mutations via standard recombinant DNA techniques.

FIG. 2.

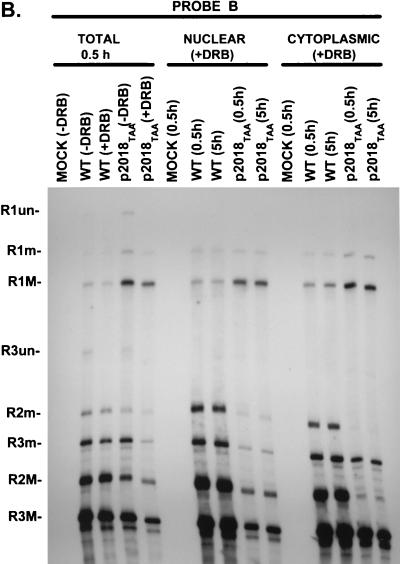

A nonsense but not a missense mutation at nt 2018 interferes with excision of the upstream intron in an ORF-dependent manner. (A) Sequences of the large intron polypyrimidine tract and nt 2018 in WT MVM and mutants, as well as the presence (fs [frameshift]) or absence of single nucleotide frameshift deletions at nt 505 and 2011, are shown below the appropriate map positions (deviations from the WT sequence are underlined). Quantitations of R2/R1 obtained by RNase protection analysis using probe B are also indicated. All values are averages of at least three separate experiments. Standard deviations are indicated in parentheses. (B) RNase protection analysis of RNA, using probe B (Fig. 1A), of RNA generated in A9 cells following transfection with WT MVM, transfection with mutants (as described in text), or mock transfection, as designated above each lane. Identities of the protected bands for WT are shown on the left and explained in Materials and Methods. ∗, undigested probe B. (C) RNase protection analysis of RNA, using probe B (Fig. 1A), of RNA generated in A9 cells following transfection with WT MVM transfection with mutants (as described in the text), or mock transfection, as designated above each lane. Identities of the protected bands are shown on the left and explained in Materials and Methods. RNA generated by pfs(505) and pfs(505)2018TAA did not generate P38 products (R3 transcripts), since the 505 frameshift mutation disrupts the ORF of NS1 which is required for transactivation of the P38 promoter. ∗, undigested probe B.

Transfection and RNA isolation.

Murine A92L cells, the normal tissue culture host for MVM(p), and baby hamster kidney (BHK) cells, were grown and transfected with wild-type (WT) and mutant MVM plasmids, using either DEAE-dextran (31, 32) or Lipofectamine-Plus reagent (as described in the protocol for the Gibco-BRL Lipofectamine-Plus reagent kit). RNA was typically isolated 48 h posttransfection, after lysis in guanidinium thiocyanate, by centrifugation through CsC1 exactly as previously described (43).

RNA analysis. (i) RNase protection assays.

RNase protection assays were performed as previously described (43), using an [α-32P]UTP-labeled, SP6-generated antisense MVM RNA probe from MVM nt 385 to 652 (probe A) or 1854 to 2378 (probe B) (Fig. 1A). Probe A identifies all P4 products and distinguishes between R1 and those RNAs that use the nt 514 donor (R2+ES [exon-skipped product]) (Fig. 3B). Probe B extends from before the acceptor site of the large intron to within the small intron common to all MVM RNAs and distinguishes between P4 RNA species using the large intron acceptor and either of the alternative small intron donors, designated by the suffixes “M” for the major splice donor (D1) at nt 2280 and “m” for the minor splice donor (D2) at nt 2317 (Fig. 2B). Thus, probe B can distinguish between unspliced (suffix “un”), minor, and major forms of both R1 and R2, as well as R3; however, it cannot detect the ES product. For analysis of RNA produced after transfection with mutants within the region covered by probe B, RNase protection probes homologous to the mutants being analyzed were used. No attempt was made to standardize between lanes for equivalent amounts of specific RNA, which vary from sample to sample depending on transfection or infection efficiencies. RNase protection products were analyzed on a Betagen B scanning phosphorimage analyzer, and molar ratios of MVM RNA were determined by standardization to the number of uridines in each protected fragment.

FIG. 3.

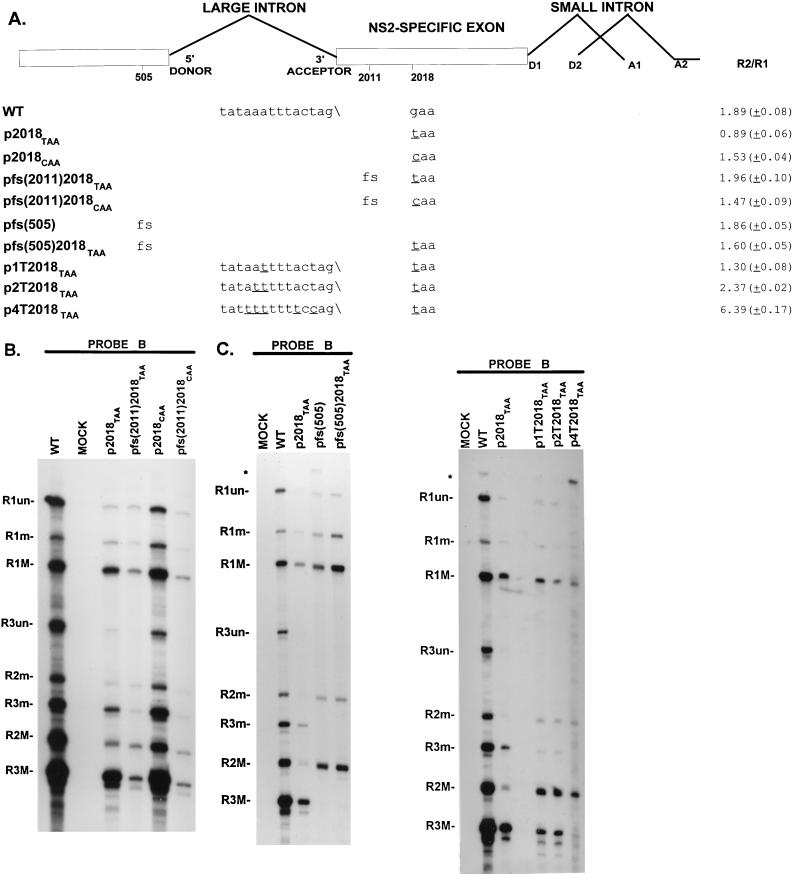

A nonsense but not a missense mutation at nt 2018 interferes, in an ORF-dependent manner, with the function of an ESE within the NS2-specific exon. (A) The restriction sites within the NS2-specific exon (SmaI, XhoI, PstI, HincII, and SacI), which divide the exon into four regions (SX, XP, PH, and HS) and were used to generate the different exon deletion mutants (ΔSX, for example, is a deletion between the SmaI and XhoI sites), are indicated. Sequences of the large intron donor, polypyrimidine tract, and nt 2018 in WT MVM and mutants, as well as the presence (fs [frameshift]) or absence of a single nucleotide frameshift deletion at nt 2011, are shown below the appropriate map positions (deviations from the WT sequence are underlined). Δ, deletion. At the bottom is shown the position of nt 2018 with respect to the CA-rich element within the 5′ SX enhancer element of the NS2-specific bipartite exon enhancer. (B) RNase protection analyses, using probes A and B (Fig. 1A), of RNA generated in A9 cells following transfection with WT MVM, transfection with mutants (as described in text), or mock transfection as designated above each lane. Identities of the protected bands in the left-hand panel are shown on the left. The larger species (R1) represents mRNA R1, while the smaller species (R2+ES) represents RNA that uses the large intron donor at nt 514. For the right-hand panel, identities of the bands generated by WT RNA and those generated by the mutants are shown on the left and right, respectively. The mutants were protected by versions of probe B homologous to the mutant region between nt 2011 and 2018 but nonhomologous in the HS region, and therefore the R1, R2, and R3 RNAs generated by these mutants protect fragments that are shorter than those generated by WT RNA. The identity of the bands designated ∗ and ∗∗ in the left-hand panel are unknown; however, they are likely breakdown products of the probe since they are not reproducibly seen and occasionally appear in lanes of mock-infected RNA (data not shown). The band designated ∗ in the right-hand panel represents undigested probe B. (C) The two panels represent RT-PCR analyses of RNA generated in A9 cells following transfection with WT MVM, transfection with mutants (as described in text), or mock transfection, as designated above each lane, with primers a and b (Fig. 1A) and performed as explained in Materials and Methods. Samples were run on a 6% acrylamide-urea gel. WT (−RT) is a control reaction utilizing WT RNA but excluding reverse transcriptase; pΔD1/2, a mutation in which both the donors of the downstream small intron were deleted and which results in almost uniform skipping of the NS2-specific exon (18, 48), was used as a control for amplification of the ES product. An RNase protection analysis, using probe B, of RNA generated by WT was used as a marker (sizes of the marker bands are shown on the left in the left-hand panel and on the right in the right-hand panel) for the sizes of the RT-PCR amplified bands. WT RNA generated a 658-nt amplified R2 product. RNA generated by the mutants showed R2 products of sizes consistent with the sizes of the deletions in these mutants, as well as two kinds of amplified ES products, both of which were considered in the quantitations: a larger 368-nt product and a smaller 346-nt product which represent exon skipping to acceptors A1 and A2 of the small intron, respectively. The ES product has previously been sequenced across the splice junction to confirm its identity (49).

(ii) Quantitative RT-PCRs.

First-strand cDNA synthesis used 5 μg of total RNA isolated after transfection and oligo(dT) priming by standard techniques (22). PCR detection of R2 and ES products was performed with primers (a and b [Fig. 1A]) described previously (49), with minor modifications (11). The forward primer (primer a) was 5′ end labeled with [γ-P32]ATP (as described in reference 30) and added to a 15-cycle PCR (94°C for 1 min, 55°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min, followed by extension at 72°C for 5 min). PCR products were run on 6% acrylamide-urea gels and analyzed on a Betagen B scanning phosphorimage analyzer, to calculate the molar ratio of R2 versus ES product (see Fig. 3C and 4C) and obtain a direct percent R2/(R2+ES) value (see Table 4).

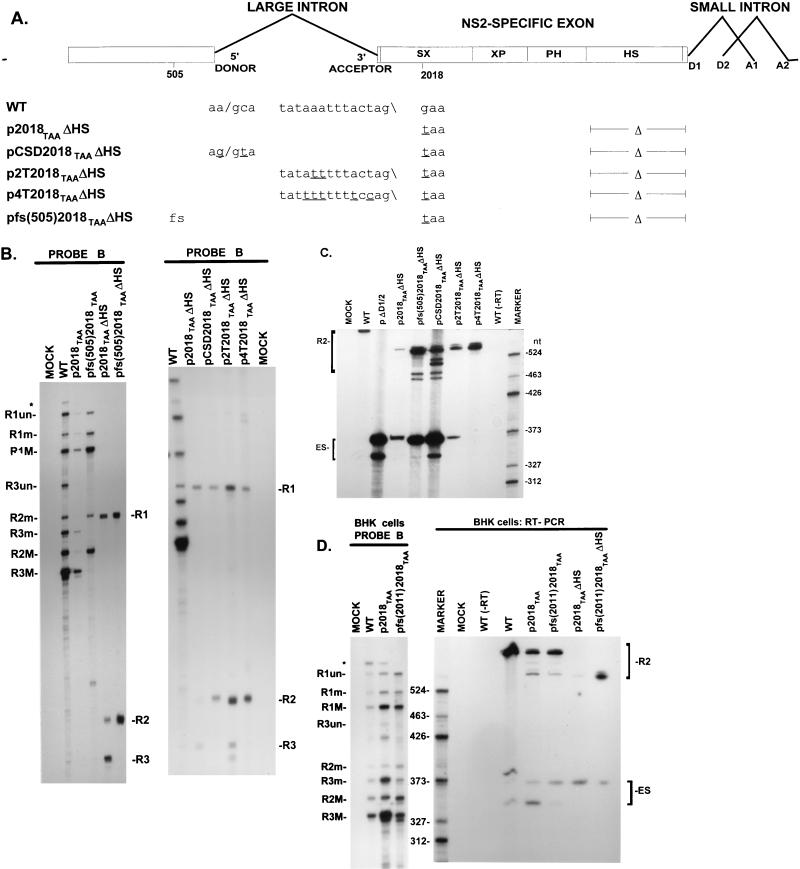

FIG. 4.

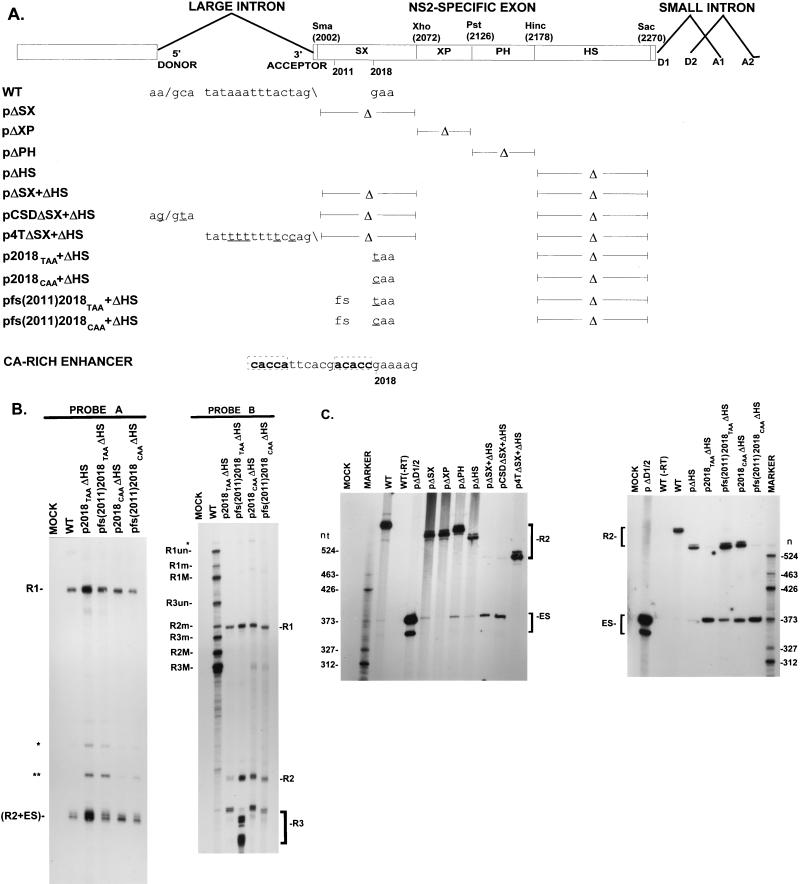

Exon skipping caused by p2018TAA+ΔHS can be suppressed by a frameshift in the upstream exon as well as by improvements of the upstream intron polypyrimidine tract. (A) The four regions (SX, XP, PH, and HS) of the NS2-specific exon are shown. Sequences of the large intron donor, polypyrimidine tract, and nt 2018 in WT MVM and mutants, as well as the presence (fs [frameshift]) or absence of a single nucleotide frameshift deletion at nt 505, are shown below the appropriate map positions (deviations from the WT sequence are underlined). Δ, deletion. (B) The two panels show RNase protection analyses of RNA, using probe B (Fig. 1A), of RNA generated in A9 cells following transfection with WT MVM, transfection with mutants (as described in the text), or mock transfection, as designated above each lane. Identities of the protected bands for WT are shown on the left, as explained in Materials and Methods, and those protected by the mutants are shown on the right of each panel. The mutants were protected by versions of probe B homologous to the mutant region of the upstream polypyrimidine tract and nt 2018 but nonhomologous in the HS region, and therefore the RNAs generated by the mutants protect fragments that are shorter than those generated by WT RNA. ∗, undigested probe B. (C) RT-PCR analysis of RNA generated by A9 cell transfections with WT MVM, transfection with mutants (as described in the text), or mock transfection, as designated above each lane, with primers a and b (Fig. 1A) as explained in Materials and Methods. Samples were run on a 6% acrylamide-urea gel. WT(−RT) and pΔD1/2 controls and marker bands are as described for Fig. 3C. WT RNA generated a 658-nt amplified R2 product, while RNA generated by the mutants showed R2 products of sizes consistent with the sizes of the deletions in these mutants. Some mutants show two or three kinds of amplified R2 products, all of which were considered in the quantitation; the largest of these is the authentic R2 product, while the smaller R2 products apparently use cryptic donors within the NS2-specific exon. As explained in the legend to Fig. 3C, two kinds of amplified exon-skipped products using either A1 or A2 were observed. (D) RNase protection analysis with probe B (Fig. 1A) (left) and quantitative RT-PCR analysis (right) of RNA generated in BHK cells following transfection with WT MVM, transfection with mutants, or mock transfection, as designated above each lane. Identities of the bands for the RNase protection assays using probe B are shown on the left. RT-PCR samples were run on a 6% acrylamide-urea gel; pΔD1/2 and WR (−RT) controls and markers for the RT-PCR are as described for Fig. 3C. In the RT-PCR analysis, RNA generated by WT shows 658-nt amplified R2 product, while RNA generated by the mutants show R2 products of sizes consistent with the sizes of the deletions in these mutants, as well as two kinds of amplified ES products, as explained in the legend to Fig. 3C. WT MVM generates more of the ES product in BHK cells than it does in murine A9 cells (Fig. 3C and 4C).

TABLE 4.

Direct measure of the percentage of R2 molecules relative to R2+ES molecules in RNA generated by WT MVM and mutants, determined by quantitative RT-PCR analysis

| Mutant | Direct % R2/(R2+ES)a |

|---|---|

| WT | 98.6 (1.2) |

| pΔD1/2 | 1.5 (2.5) |

| p2018TAA+ΔHS | 18.1 (5.3) |

| p2018CAA+ΔHS | 67.2 (2.1) |

| pfs(2011)2018TAA+ΔHS | 71.1 (5.3) |

| pfs(2011)2018CAA+ΔHS | 15.1 (4.1) |

| pΔSX | 93.0 (2.0) |

| pΔXP | 98.1 (1.2) |

| pΔPH | 94.2 (2.1) |

| pΔHS | 92.8 (3.3) |

| pΔSX+ΔHS | 15.2 (4.1) |

| pCSDΔSX+ΔHS | 14.2 (2.1) |

| p4TΔSX+ΔHS | 97.3 (1.2) |

| pCSD2018TAA+ΔHS | 29.1 (2.5) |

| p2T2018TAA+ΔHS | 67.2 (2.1) |

| p4T2018TAA+ΔHS | 97.1 (1.3) |

| pfs(505)2018TAA+ΔHS | 50.1 (4.1) |

To demonstrate that our RT-PCR assay was quantitative and accurately reflected the ratio of R2 to ES molecules in total RNA, we performed a comparison via RNase protection analysis of the RNA using probes A and B (Fig. 3). First, RNase protection probe A (Fig. 1A) was used to determine the ratio of molecules using the upstream intron donor at 514 (R2+ES) relative to R1 (Fig. 3B; see Table 2). RNase protection probe B (Fig. 1A) was then used to establish a quantitative ratio of R2 molecules relative to R1 molecules (Fig. 3B; see Table 2). Comparison of these values enabled indirect determination of the ratio between R2 and R2+ES percents (see Table 2) for comparison with values obtained by RT-PCR. Direct percent R2/(R2+ES) values obtained by quantitative RT-PCR assay (Fig. 3C; see Table 4) varied by no more than 7% from the values obtained indirectly from quantitative RNase protection assays (see Table 2) when tested multiple times with a panel of 15 mutants with different percents R2/(R2+ES) values (17) [for example, compare RT-PCR and RNase protection values for WT, pΔD1/2, p2018TAA+ΔHS, p2018CAA+ΔHS, pfs(2011)2018TAA+ΔHS, and pfs(2011)2018CAA+ΔHS (see Tables 2 and 4)]. Furthermore, the percents R2/(R2+ES) values obtained from RT-PCR varied by no more than 4% over a series dilution of template cDNA and over a range of 15, 20, or 30 cycles (17).

TABLE 2.

Indirect measure of the percentage of R2 molecules relative to R2+ES molecules in RNA generated by WT MVM or mutants

| Mutant | (R2+ES)/R1a | R2/R1b | Indirect % R2/(R2+ES)c |

|---|---|---|---|

| WT | 1.91 (0.05) | 1.89 (0.08) | 98.3 (1.1) |

| pΔD1/2 | 5.26 (0.07) | 0.091 (0.003) | 1.6 (2.1) |

| p2018TAA+ΔHS | 3.80 (0.18) | 0.60 (0.13) | 16.1 (4.7) |

| p2018CAA+ΔHS | 2.48 (0.10) | 1.72 (0.09) | 69.2 (2.1) |

| pfs(2011)2018TAA+ΔHS | 2.50 (0.16) | 1.87 (0.11) | 75.1 (4.1) |

| pfs(2011)2018CAA+ΔHS | 3.20 (0.11) | 0.69 (0.08) | 22.7 (3.6) |

Ratio of RNAs using the large intron donor at nt 514 (R2+ES) relative to R1, as determined by RNase protection assays using probe A (shown in Fig. 1A). Values are averages of at least three separate experiments, examples of which are shown in Fig. 3B (except for pΔD1/2). Standard deviations are indicated in parentheses.

Ratio of R2 relative to R1, as determined by RNase protection assays using probe B (shown in Fig. 1A). Values shown are averages of at least three separate experiments, examples of which are shown in Fig. 3B (except for pΔD1/2). Standard deviations are indicated in parentheses.

Determined from the (R2+ES)/R1 ratio and the R2/R1 ratio as described in Materials and Methods. Values are averages of at least three separate experiments. Standard deviations are indicated in parentheses.

For some of the mutants, the relative amounts of R1, R2, and ES product were calculated as a percentage of the total P4-generated product (see Table 3). These calculations, for all mutants except pCSD2018ΔHS and pfs(505)2018TAA+ΔHS, were done by using the (R2+ES)/R1 ratio (obtained by use of RNase protection analysis probe A), the R2/R1 ratio (obtained by use of RNase protection analysis probe B), and the indirect percents R2/(R2+ES) value (obtained as explained above). For pCSD2018ΔHS and pfs(505)2018TAA+ΔHS, these calculations were done by using the R2/R1 ratio (obtained by use of RNase protection analysis probe B) and the direct percent R2/(R2+ES) value (obtained from quantitative RT-PCR).

TABLE 3.

Relative amounts of R1, R2, and ES product as a percentage of total P4-generated product

| Mutant | % of P4 producta

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| R1 | R2 | ES | |

| WT | 34.1 (2.1) | 65.2 (1.9) | <1e |

| pΔD1/2b | 16.1 (2.0) | 1.5 (1.1) | 83.2 (1.1) |

| p2018TAAΔHS | 20.0 (3.0) | 12.1 (2.2) | 69.1 (3.1) |

| p2018CAA+ΔHS | 29.2 (2.1) | 50.0 (3.1) | 22.1 (1.0) |

| pfs(2011)2018TAA+ΔHS | 29.2 (2.0) | 54.1 (4.1) | 18.1 (1.3) |

| pfs(2011)2018CAA+ΔHS | 24.1 (3.3) | 17.1 (3.1) | 60.2 (2.1) |

| pCSD2018TAA+ΔHSc | 20.1 (3.1) | 19.1 (1.3) | 61.7 (3.1) |

| p2T2018TAA+ΔHSd | 26.1 (3.1) | 54.2 (2.7) | 20.1 (1.1) |

| p4T2018TAA+ΔHSd | 15.2 (2.3) | 83.6 (3.1) | 2.5 (1.8) |

| pfs(505)2018TAA+ΔHSc | 20.7 (4.6) | 41.2 (5.4) | 40.1 (5.2) |

Calculated from RNase protection analyses using probes A and B (Fig. 1A), examples of which are shown in Fig. 3B. Values shown are averages of at least three separate experiments. Standard deviations are indicated in parentheses.

RNase protection analysis using probes A and B for RNA generated by this mutant, although not shown in Fig. 3B or 4B, were used for the calculations as described in Materials and Methods.

Values were calculated from RNase protection analysis with probe B (an example shown in Fig. 4B) and quantitative RT-PCR analysis (an example shown in Fig. 4C) as described in Materials and Methods.

RNase protection analyses using probes A (an example is not shown) and B (an example is shown in Fig. 4B) for RNA generated by this mutant were performed, and values were calculated from these protection analyses as described in Materials and Methods.

For RNA generated by WT MVM, the indirect measures are not precise enough to establish the presence of the ES product, and direct RT-PCR analysis inconsistently showed a small (<1%) amount of the ES product.

Nuclear and cytoplasmic RNA stability experiment.

WT and mutant (2018TAA) virus stocks were titered, propagated, and used to infect A92L murine fibroblasts as previously described (31). The 2018TAA virus is a host range mutant virus that can be propagated in 324K cells (31, 32). At 24 h after infection, A92L cells were treated with 40 μg/l of 5,6-dichloro-1-β-d-ribofuranosyl benzimidazole (DRB) (Sigma) per ml, and nuclear and cytoplasmic fractionation of infected cellular RNA was done as described previously (32) at 0.5 and 5 h after the addition of DRB. DRB was used rather than actinomycin D since the latter has been shown to stabilize some RNA species (24). We have previously determined that this concentration of DRB effectively inhibits the production of MVM-specific RNA in infected murine A9 cells (32, 43). Briefly, nuclei were isolated after pelleting through sucrose twice, and the nuclear fractions were determined to be >95% pure, as monitored by the relative absence of mature rRNA and the presence of rRNA precursors in these preparations, by ethidium bromide staining after gel electrophoresis (data not shown) as described previously (32). The relative ratio of unspliced to spliced messages in the nuclear RNA preparations is also consistent with the purity of the nuclear fractions (data not shown). The absence of unspliced R1 and R3 in total RNA isolated 0.5 h after treatment with DRB demonstrated that minimal P4 or P38 transcription occurred after exposure to the drug. RNase protection assays using probe B were done as described above.

RESULTS

A PTC at nt 2018 in the MVM NS2-specific exon results in an increased accumulated steady-state level of R1 relative to R2 but does not target R2 mRNA for nuclear or cytoplasmic degradation in vivo.

We previously showed that virus bearing a PTC transversion mutation at nt 2018 within the MVM NS2-specific exon (2018TAA [Fig. 1A]) generated approximately half of the nuclear levels of doubly spliced R2 mRNA relative to singly spliced R1 mRNA compared to the ratio generated during WT infection, although the total accumulated levels of P4-generated product remained the same (32) (Fig. 1B; Table 1). Now we demonstrate that in the presence of the transcriptional inhibitor DRB, 2018TAA-generated RNAs were as stable as those generated by WT MVM; there was no detectable difference in the relative stability of either R1, PTC-containing R2, or the total P4 product, as measured relative to the P38-generated product R3 (Fig. 1B; Table 1). These results, together with evidence presented below, demonstrated that neither nuclear or cytoplasmic degradation of PTC-containing R2 nor an increase in the stability of R1 could account for reduced accumulated ratios of R2 relative to R1, suggesting that the decreased levels of R2 generated by 2018TAA may have been due to PTC-mediated interference with excision of the upstream large intron from P4-generated pre-mRNA.

TABLE 1.

Stability of R1, R2, and total P4 product in nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions of WT MVM- and 2018TAA-infected A9 cells at 0.5 and 5 h after the addition of DRB

| Mutant | Total RNA, 0.5 h

|

Nuclear RNA

|

Cytoplasmic RNA

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −DRB | +DRB | 0.5 h after DRB added | 5 h after DRB added | 0.5 h after DRB added | 5 h after DRB added | |

| WT | ||||||

| R2/R1a | 1.97 (0.13) | 1.90 (0.14) | 2.06 (0.23) | 2.02 (0.16) | 3.48 (0.28) | 3.39 (0.19) |

| (R2+R1)/R3b | 0.50 (0.11) | 0.47 (0.12) | 0.57 (0.10) | 0.55 (0.11) | 0.61 (0.14) | 0.58 (0.11) |

| 2018TAA | ||||||

| R2/R1 | 0.91 (0.06) | 0.88 (0.12) | 0.84 (0.12) | 0.87 (0.10) | 0.49 (0.08) | 0.51 (0.09) |

| (R2+R1)/R3 | 0.56 (0.11) | 0.58 (0.13) | 0.54 (0.14) | 0.53 (0.10) | 0.50 (0.13) | 0.47 (0.11) |

Ratio of R2 relative to R1, as determined by RNase protection assays using probe B for either WT MVM or 2018TAA, as indicated. Values are averages of at least two separate experiments, in which the purity of nuclear RNA was determined to be >95% (as described in Materials and Methods), an example of which is shown in Fig. 1B. Standard deviations are indicated in parentheses. Two additional experiments in which the purity of nuclear RNA was determined to be >90% gave approximately the same values (data not shown).

Ratio of total P4 product (R2+R1) relative to total P38 product (R3), as determined by RNase protection assays using probe B for either WT MVM or 2018TAA, as indicated. Since the ratio of P4 product to P38 product remains relatively constant during infection, this ratio allows us to monitor a change in the nuclear or cytoplasmic stability of the total P4 product after inhibiting transcription with DRB. Values are averages of at least two separate experiments, in which the purity of nuclear RNA was determined to be >95% (as described in Materials and Methods), an example of which is shown in Fig. 1B. Standard deviations are indicated in parentheses. Two additional experiments in which the purity of nuclear RNA was determined to be >90% gave approximately the same values (data not shown).

By 0.5 h after DRB addition, there was a significantly higher ratio of accumulated R2 relative to R1 in the cytoplasmic fraction compared to the nuclear fraction during WT infection. During 2018TAA infection, however, while the levels of R2 relative to R1 were lower than that seen for the WT, there was an even lower ratio of accumulated R2 relative to R1 in the 2018TAA cytoplasmic fraction compared to the nuclear fraction (Fig. 1B; Table 1). The total P4-to-P38 ratios [i.e., (R2+R1)/R3] were approximately the same for both infections and in both compartments. Similar results were obtained previously in the absence of DRB (32). These results may suggest that there is an additional effect on the transport of 2018 PTC-containing R2 RNA.

A nonsense mutation at nt 2018 in the NS2-specific exon interferes with excision of the upstream intron in an ORF-dependent manner.

R2 encodes the viral protein NS2, which is normally translated in ORF2 within the NS2-specific exon (Fig. 1A). Deletion of nt 2011 in the NS2-specific exon (Fig. 2A) prior to the PTC at nt 2018 shifted the NS2-encoding ORF2 into the long ORF3 which is normally used for NS1. The PTC at nt 2018 was thus bypassed in R2 by this frameshift and the NS2 ORF was thus reopened until the authentic stop site for NS1 at nt 2278 (Fig. 1A). This frameshift [pfs(2011)2018TAA (Fig. 2A)] resulted in the recovery to WT levels of accumulated R2 relative to R1 (Fig. 2A and B). While a missense transversion mutation at nt 2018 (p2018CAA [Fig. 2A]) also resulted in a minor decrease in the accumulated levels of R2 relative to R1, a frameshift-causing deletion at nt 2011 [pfs(2011)2018CAA (Fig. 2A)] was unable to suppress this small effect (Fig. 2A and B). Thus, the effect on excision of the upstream intron of the nonsense, but not the missense, transversion mutation at nt 2018 was dependent on the integrity of a previously open reading frame that had the potential, after splicing, to be in frame with the initiating AUG.

Minor improvements of the upstream large intron polypyrimidine tract were also able to dramatically suppress the effect of p2018TAA (Fig. 2A and C). Improvements in the polypyrimidine tract of the large upstream intron increase its efficiency of excision (48), and since these mutations do not reside in the final R2 mRNA product, these results further supported a model in which the premature termination codon at nt 2018, rather than affecting the stability of R2 mRNA, interfered with the excision of the upstream intron from P4-generated pre-mRNAs, perhaps by impeding interactions at the upstream intron polypyrimidine tract.

A nonsense mutation at nt 2018 in the NS2-specific exon interferes with the function of an ESE in an ORF-dependent manner.

The PTC at nt 2018 resulted in decreased excision of the upstream large intron; however, nonsense mutations within internal exons in other genes have been, on occasion, shown to cause skipping of these exons. The NS2-specific exon contains a bipartite ESE that is required for efficient inclusion of this exon into mature spliced mRNA and consequently for efficient splicing of the upstream intron. This bipartite ESE consists of a 22-nt CA-rich element within the 5′ region of the exon (called the SX region) and a 58-nt purine-rich element in the 3′ region of the exon (called the HS region) (18). These elements have at least partially redundant functions; while deletion of either element alone (pΔSX or pΔHS [Fig. 3A and 3C, left panel; see Table 4] [18]) or extensive point mutagenesis of the SX enhancer element (18) permitted efficient inclusion of the NS2-specific exon, deletion of both elements together (pΔSX+ΔHS [Fig. 3A and C, left panel; see Table 4] [18]) resulted in substantial skipping of this exon in P4-generated pre-mRNAs (18), whereby the large intron donor at nt 514 was joined to either of the small intron acceptors. (Skipping of the NS2-specific exon could not be directly assessed by RNase protection analysis in our system. To measure the relative accumulated levels of P4-generated R2 and potential NS2-specific ES products, we used a quantitative RT-PCR assay, the results of which were validated indirectly by quantitative RNase protection assays as described below and in detail in Materials and Methods.) Improvement of the upstream intron polypyrimidine tract (p4TΔSX+ΔHS [Fig. 3A and C, left panel; see Table 4] [18]), but not improvement of the upstream intron donor (pCSDΔSX+ΔHS [Fig. 3A and C, left panel; see Table 4] [18]) could suppress exon skipping and substantially restore inclusion of the NS2-specific exon to the mutant in which both elements of the enhancer had been deleted, which suggested a model in which the bipartite ESE functioned by strengthening interactions at the weak upstream intron polypyrimidine tract (18).

The PTC at nt 2018 lies directly adjacent to the CA-rich motif within the 5′ SX element of the bipartite ESE (Fig. 3A, bottom). The 2018 PTC, similar to point mutations in the 5′ SX element (18), by itself does not induce significant exon skipping (data not shown). When the 2018 PTC was combined with a deletion of the 3′ HS element (p2018TAA+ΔHS [Fig. 3A]), however, the NS2-specific exon was skipped to levels seen for RNA generated by the double exon enhancer deletion mutant pΔSX+ΔHS. (Quantitative RT-PCR analysis which detects the ES product directly is shown in Fig. 3C [and see Table 4]; these values were validated indirectly by RNase protection analyses [Fig. 3B and Table 2] as explained in detail in Materials and Methods.) The ES product represented approximately 70% of the total p2018TAA+ΔHS-generated P4 product (Table 3). ΔHS is an in-frame deletion in the NS2 ORF which when present alone permitted near WT levels of exon inclusion (pΔHS [Fig. 3A and C; Table 4]). These results suggested that the PTC at nt 2018 affected NS2-specific exon inclusion in a manner phenotypically similar to disabling of the SX enhancer element. As might be expected for any mutation in an ESE, combination of the missense mutation at nt 2018 with deletion of the HS element (p2018CAA+ΔHS [Fig. 3A]) also resulted in exon skipping, but to a considerably lesser degree (Fig. 3B and C; Tables 2 and 4). The ES product represented approximately 22% of the total p2018CAA+ΔHS-generated P4 product (Table 3).

In the context of ΔHS, shifting of the 2018 PTC out of the NS2 ORF by deletion of nt 2011 within the NS2-specific exon [pfs(2011)2018TAA+ΔHS (Fig. 3A)] resulted in a dramatic recovery of exon inclusion, back to approximately the same levels seen for RNA generated by p2018CAA+ΔHS (Fig. 3B and C; Tables 2 and 4). The ES product represented approximately 18% of the total pfs(2011)2018TAA+ΔHSgenerated P4-product (Table 3.) The 2011 frameshift mutation was unable to suppress exon skipping of 2018CAA+ΔHS [pfs(2011)2018CAA+ΔHS (Fig. 3A)], however, and in fact resulted in an even greater loss of exon inclusion (Fig. 3B and C; Tables 2 and 4). The ES product now represented approximately 60% of the total pfs(2011)2018CAA+ΔHS-generated P4 product (Table 3). It may be that a C at nt 2018 disables the ESE to a greater degree than a T at this position, so that the double mutation (deletion of nt 2011 plus a C at nt 2018) results in even greater exon skipping. These results suggest that although both a nonsense (PTC) and a missense transversion mutation at nt 2018 in the NS2-specific exon interfered with the function of the 5′ SX element of the bipartite ESE, the major component of the effect of the PTC was open ORF dependent.

Improvement of the upstream intron polypyrimidine tract in p2018TAA+ΔHS by as few as two pyrimidines (p2T2018TAA+ΔHS [Fig. 4A]), but not improvement of the large intron donor, also suppressed exon skipping to the same extent that such improvement suppressed a mutation that deleted both exon enhancer elements [pΔSX+ΔHS and p4TΔSX+ΔHS [Fig. 3C; Table 4]). (Quantitative RT-PCR analysis [Fig. 4C; Table 4] was validated by RNase protection analysis with probe B [Fig. 4B], which together allowed determination of the amount of ES product as a percentage of the total P4 product for each mutant [Table 3]). Since the improvements of the polypyrimidine tract lie outside the final R2 mRNA, their effect cannot be attributed merely to an increase in the stability of R2. These observations were most consistent with a model in which the PTC at nt 2018, rather than affecting the stability of R2, interfered with NS2-specific exon definition and with the ability of the ESE to strengthen interactions at the upstream intron polypyrimidine tract.

Deletion of nt 505 within the upstream NS1/NS2-shared exon (Fig. 1A) also shifted the NS2 ORF in R2 into ORF3 after the large splice, thus bypassing the PTC at 2018 and reopening the NS2 ORF. This frameshift mutation resulted in substantial suppression of the p2018TAA phenotype (restoration of accumulated R2 relative to R1) to near WT levels [pfs(505)2018TAA (Fig. 2A and C, left panel) and also resulted in substantial suppression of the exon skipping seen for p2018TAA+ΔHS [pfs(505)2018TAA+ΔHS (Fig. 4A to C; Table 4)]. The ES product was reduced to approximately 40% of the total pfs(505)2018TAA+ΔHS-generated P4 product (Table 3). Since the deletion at nt 505 was within the upstream exon, 1.5 kb away from the PTC at nt 2018, the effect of the 505 frameshift mutation was unlikely to be due to the restoration of a cis-acting splicing signal that may have been disrupted by the PTC. In addition, the intron retention seen for p2018TAA and the loss of exon inclusion seen for p2018TAA+ΔHS were both ORF dependent in a manner necessitating communication between reading frames in the upstream and downstream NS2 exons, probably before the intervening large intron was spliced out.

The effect of the PTC at nt 2018 was not restricted to murine A92L fibroblast cells, the natural host for MVM. Examination of RNAs generated by transfection of p2018TAA and pfs(2011)2018TAA in BHK cells, which also support MVM infection, demonstrated ORF-dependent reduction in the accumulation of R2 relative to R1, similar to that seen in A92L cells (RNase protection analysis with probe B shown in Fig. 4D, left panel). Further, examination of RNAs generated by p2018TAA+ΔHS and pfs(2011)2018TAA+ΔHS in BHK cells revealed that the PTC at nt 2018 interfered with the function of the NS2-specific ESE in an ORF-dependent manner, similar to observations for A92L cells. (Quantitative RT-PCR analysis [Fig. 4D, right panel] was also validated by RNase protection analysis [data not shown].) Thus the ORF-dependent effect of a PTC at nt 2018 was evident in cell types from two different species.

DISCUSSION

In this report we demonstrate that a PTC at nt 2018, which caused a decrease in the accumulated levels of R2 relative to R1, although the total accumulated levels of R1+R2 remained the same, had no effect on either the nuclear or cytoplasmic stability of either R2 mRNA, R1 mRNA, or the total P4 product. This suggests that neither nucleus-associated or cytoplasmic degradation of PTC-containing R2 nor an increase in the stability of R1 could account for the decrease in R2 relative to R1. This interpretation was supported by the following observations. First, minor improvements in the upstream intron polypyrimidine tract could overcome the 2018 PTC effect and return accumulation of R2 to WT levels. Since these improvements lie outside the final mRNA, their effect could not be attributed merely to restoration of mRNA stability. Second, the effect of the 2018 PTC on the accumulation of R2 could be suppressed by mutations in either NS2-encoding exon which shift this PTC out of the NS2 ORF. These observations are consistent with a model in which the 2018 PTC interfered with nuclear excision of the upstream intron from P4-generated pre-mRNA in an ORF-dependent manner.

The 2018 PTC interferes the function of an ESE within the NS2-specific exon that is required for efficient inclusion of this exon in an ORF-dependent manner.

Naturally occurring PTCs that have been shown to result in exon skipping are present within candidate purine-rich ESE in the 3-hydroxyl-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A, adenosine deaminase, FBN1, OAT, and dystrophin genes (15, 38, 42, 44). It may be that the skipped exons in these examples contain a single ESE element that is required for exon inclusion. Inclusion of the NS2-specific exon of MVM is governed by a bipartite ESE, which includes a CA-rich 5′ element (SX) and a purine-rich 3′ element (HS) that are redundant in function. The 2018 PTC transversion mutation, which when present alone resulted in retention of the upstream intron rather than exon skipping, is directly adjacent to the CA-rich motif within the 5′ SX element. Combination of the 2018 PTC and the 3′ HS enhancer element deletion (p2018TAA+ΔHS) resulted in a significant loss of NS2-specific exon inclusion. Consequently, the NS2-specific exon was skipped in P4-generated RNA, to levels similar to that seen in RNA generated by a mutant in which both the 5′ SX element and the 3′ HS element had been deleted (pΔSX+ΔHS). This implied that that the 2018TAA mutation was phenotypically similar to disabling of the SX enhancer element. Combination of ΔHS and a missense transversion mutation at nt 2018 alone (p2018CAA+ΔHS) resulted in some exon skipping, as might be expected for a missense mutation in an ESE. Shifting the 2018 PTC out of the NS2 ORF in the context of the HS element deletion [pfs(2011)2018TAA+ΔHS] resulted in recovery of exon inclusion back to the levels seen for the missense p2018CAA+ΔHS; however, the effect of 2018CAA+ΔHS could not be suppressed by such a frameshift [pfs(2011)2018CAA+ΔHS]. These results suggested that while both the PTC and missense transversion mutations had direct, ORF-independent effects on the function of the 5′ SX enhancer element, the PTC mutation had an additional effect which was ORF dependent.

A model to explain the effects of the 2018 PTC. (i) Nuclear detection of reading frame.

2018 PTC-mediated intron retention and exon skipping is nucleus associated and ORF dependent. These observations imply that PTCs in P4 pre-mRNAs can be recognized in the nucleus before or concomitant with exon definition and exon juxtaposition during splicing, as has been proposed for the DHFR gene (47). There is no direct evidence that such a reading frame recognition exists in the nucleus (28); however, a number of recent observations open the possibility that an appropriate apparatus may be in place. Ribosomal proteins and RNAs, elongation factor subunits eIF2A (8) and eIF4E (25), and aminoacyl-tRNAs (27) have recently been detected in the nucleus, and U5 snRNP, which binds to exon sequences adjacent to 5′ and 3′ splice sites and has a role in juxtaposing exons during splicing (34–36, 46), contains a 116 kDa protein which is both essential for splicing and closely related to the ribosomal translocase EF-2 (16). Finally, it has been reported in one instance that nonsense mutations can inhibit RNA splicing in an in vitro splicing-competent nuclear extract in a manner independent of protein synthesis (1), which is also consistent with the existence of such a function. We have also recently shown that the effect of the 2018 PTC was not dependent on the presence of an initiating AUG codon, suggesting that this effect was independent of cytoplasmic translation (17).

Frameshift mutational analysis showed that the effects of p2018TAA and p2018TAA+ΔHS were ORF dependent in a manner necessitating communication between reading frames in the upstream and downstream NS2 exons, since either intron retention or exon skipping was the effect observed, probably before the intervening large intron was spliced out. While it may be argued that nuclear pre-mRNA does not possess a continuous reading frame due to the presence of introns, a continuous reading frame in pre-mRNA may exist when exons are juxtaposed after initial exon definition but before introns are finally spliced out (7), an idea that is implicit in previous reports proposing that nuclear scanning affects splicing (8, 14).

(ii) If there is ORF scanning in the nucleus, how might such a mechanism affect nuclear steps of RNA processing?

Numerous models have been proposed to explain decreases in the nuclear abundance of PTC-containing RNAs, including effects on RNA stability and various steps of RNA processing (8, 28). For MVM P4-generated RNAs, although a PTC in the NS2-specific exon affects the relative accumulated levels of various spliced products, the PTC-containing RNAs in both the nuclear and cytoplasmic factions were very stable, suggesting that the 2018 PTC may have a direct effect on P4 pre-mRNA splicing. Since a significant component of the 2018 PTC effect was ORF dependent, and since this PTC interfered with the ability of the 5′ element of the bipartite NS2-specific ESE to strengthen interactions at the weak upstream polypyrimidine tract, perhaps recognition of the 2018 PTC somehow prevented the exon definition machinery from interacting with the 5′ exon enhancer element (SX). The net effect of this interaction would either be upstream intron retention (2018TAA) or exon skipping (p2018TAA+ΔHS). We have previously shown that PTCs at nt 2159 and 2268, which do not fall within the bipartite ESE of the NS2-specific exon, have very small effects on upstream intron excision (32). Although ESEs are thought to act primarily early in splice site recognition (7), an effect at later times during the splicing process has not been ruled out.

There is increasing evidence of nucleus-associated NMD in mammalian cells (28). There are at least two models that could reconcile our observations that PTC-containing MVM R2 is stable with the existence of an NMD pathway. In the first model, it may be that PTCs do indeed directly mediate NMD, but the process of large intron excision interferes with the putative nuclear scanning mechanisms. Consequently, decay of R2 would be prevented; however, efficient excision of the large intron may thus also be affected. In an alternative model, nucleus-associated NMD may occur after PTC-mediated effects on splicing. Degradation of PTC-containing RNAs, however, may not proceed under conditions in which a functional alternatively spliced product exists. If this were the case for MVM P4-generated RNA, since R1 is a functional alternative to PTC-containing R2 RNA, the presence of the 2018 PTC might result in the accumulation of non-PTC-containing R1, thus sparing R2 from degradation.

Our nuclear/cytoplasmic fractionation experiments suggest that the 2018 PTC may have an additional effect on the transport of R2 mRNA relative to R1 mRNA (Fig. 1B; Table 1). The ratio of PTC-containing R2 to R1 was less in the cytoplasm that it was in the nucleus. While this may be an independent effect, it may also suggest that transport and splicing of MVM RNA are linked such that a block to pre-mRNA splicing results in a subsequent block to transport of mRNAs, as has been previously suggested (21).

The effect of the PTC at 2018 appeared to occur in at least two independent cell types. This finding suggested that, unlike the cell-type-specific effect of nonsense mutations seen for Igκ and T-cell receptor beta-chain RNAs (1, 8), nonsense-mediated effect in MVM P4-generated RNA was not species specific and may thus be a part of a more generalized mechanism which scans ORFs in the nucleus.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Lynne Maquat and Greg Tullis for valuable advice and discussion and to Lisa Burger for excellent technical assistance.

This work was supported by PHS grant RO1 A121302 from NIAID and a grant from the Council for Tobacco Research, U.S.A., to D.J.P. A.G. was partially supported by the University of Missouri Molecular Biology Program during a portion of this work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aoufouchi S, Yélamos J, Milstein C. Nonsense mutations inhibit RNA splicing in a cell-free system: recognition of mutant codon is independent of protein synthesis. Cell. 1996;85:415–422. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81119-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Astell C R, Gardiner E M, Tattersall P. DNA sequence of the lymphotropic variant of minute virus of mice, MVM(i), and comparison with the DNA sequence of the fibrotropic prototype strain. J Virol. 1986;57:656–669. doi: 10.1128/jvi.57.2.656-669.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baserga S J, Benz E J., Jr β-Globin nonsense mutation: deficient accumulation of mRNA occurs despite normal cytoplasmic stability. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:2935–2939. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.7.2935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Belgrader P, Cheng J, Maquat L E. Evidence to implicate translation by ribosomes in the mechanism by which nonsense codons reduce the nuclear level of human triosephosphate isomerase mRNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:482–486. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.2.482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Belgrader P, Cheng J, Zhou X, Stephenson L S. Mammalian nonsense codons can be cis effectors of nuclear mRNA half-life. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:8219–8228. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.12.8219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Belgrader P, Maquat L E. Nonsense but not missense mutations can decrease the abundance of nuclear mRNA for the mouse major urinary protein, while both types of mutations can facilitate exon skipping. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:6326–6336. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.9.6326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berget S M. Exon recognition in vertebrate splicing. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:2411–2444. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.6.2411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carter M S, Li S, Wilkinson M F. A splicing-dependent regulatory mechanism that detects translation signals. EMBO J. 1996;15:5965–5975. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheng J, Maquat L E. Nonsense codons can reduce the abundance of nuclear mRNA without affecting the abundance of pre-mRNA or the half-life of cytoplasmic mRNA. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:1892–1902. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.3.1892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clemens K E, Pintel D J. Minute virus of mice (MVM) mRNAs predominantly polyadenylate at a single site. Virology. 1987;160:511–514. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(87)90028-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cooper, T. 1998. Personal communication.

- 12.Cotmore S F, Tattersall P. Organization of nonstructural genes of the autonomous parvovirus minute virus of mice. J Virol. 1986;58:724–732. doi: 10.1128/jvi.58.3.724-732.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cotmore S F, Tattersall P. The autonomously replicating parvoviruses of vertebrates. Adv Virus Res. 1987;33:91–174. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3527(08)60317-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dietz H C, Kendzior R J., Jr Maintenance of an open reading frame as an additional level of scrutiny during splice site selection. Nat Genet. 1994;8:183–188. doi: 10.1038/ng1094-183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dietz H C, Valle D, Francomano C A, Kendzior R J, Jr, Pyeritz R E, Cutting G R. The skipping of constitutive exons in vivo induced by nonsense mutations. Science. 1993;259:680–683. doi: 10.1126/science.8430317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fabrizio P, Laggerbauer B, Lauber J, Lane W S, Lührmann R. An evolutionarily conserved U5 snRNP-specific protein is a GTP binding factor closely related to the ribosomal translocase EF-2. EMBO J. 1997;16:4092–4106. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.13.4092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gersappe, A., and D. J. Pintel. 1998. Unpublished data.

- 18.Gersappe A, Pintel D J. CA- and purine-rich elements form a novel bipartite exon enhancer which governs inclusion of the minute virus of mice NS2-specific exon in both singly and doubly spliced mRNA. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:364–375. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.1.364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gibson R A, Hajianpour A, Murer-Orlando M, Buchwald M, Mathew C G. A nonsense mutation and exon skipping in the Fanconi anaemia group C gene. Hum Mol Genet. 1993;2:797–799. doi: 10.1093/hmg/2.6.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haut D D, Pintel D J. Intron definition is required for excision of the minute virus of mice small intron and definition of the upstream exon. J Virol. 1998;72:1834–1843. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.3.1834-1843.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang Y, Carmichael G G. A suboptimal 5′ splice site is a cis-acting determinant of nuclear export of polyomavirus late mRNAs. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:6046–6054. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.11.6046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Innis M A, Gelfand D H, Sninski J J, White T J. PCR protocols. A guide to methods and applications. San Diego, Calif: Academic Press, Inc.; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kendzior, R. 1998. Personal communication.

- 24.Kessler O, Chasin L A. Effects of nonsense mutations on nuclear and cytoplasmic adenine phosphoribosyltransferase RNA. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:4426–4435. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.8.4426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lejbkowicz F, Goyer C, Darveau A, Neron S, Lemieux R, Sonenberg N. A fraction of the mRNA 5′ cap-binding protein, eukaryotic initiation factor 4E, localizes to the nucleus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:9612–9616. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.20.9612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lozano F, Maertzdorf B, Pannell R, Milstein C. Low cytoplasmic mRNA levels of immunoglobulin kappa light chain genes containing nonsense codons correlate with inefficient splicing. EMBO J. 1994;13:4617–4622. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06783.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lund E, Dahlberg J E. Proofreading and aminoacylation of tRNAs before export from the nucleus. Science. 1998;282:2082–2085. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5396.2082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maquat L E. When cells stop making sense: effects of nonsense codons on RNA metabolism in vertebrate cells. RNA. 1995;1:453–465. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maquat L E. Defects in RNA splicing and the consequence of shortened translational reading frames. Am J Hum Genet. 1996;59:279–286. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McCullough A J, Berget S M. G Triplets located throughout a class of small vertebrate introns enforce intron borders and regulate splice site selection. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:4562–4571. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.8.4562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Naeger L K, Cater J, Pintel D J. The small nonstructural protein (NS2) of minute virus of mice is required for efficient DNA replication and infectious virus production in a cell-type-specific manner. J Virol. 1990;64:6166–6175. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.12.6166-6175.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Naeger L K, Schoborg R V, Zhao Q, Tullis G E, Pintel D J. Nonsense mutation inhibit splicing of MVM RNA in cis when they interrupt the reading frame of either exon of the final spliced product. Genes Dev. 1992;6:1107–1111. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.6.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Naylor J A, Green P M, Rizza C R, Giannelli F. Analysis of factor VIII mRNA reveals defects in everyone of 28 haemophilia A patients. Hum Mol Genet. 1993;2:11–17. doi: 10.1093/hmg/2.1.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Newman A J, Norman C. U5 snRNA interacts with exon sequences at 5′ and 3′ splice sites. Cell. 1992;68:743–754. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90149-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Newman A J, Teigelkamp S, Beggs J D. snRNA interactions at 5′ and 3′ splice sites monitored by photoactivated crosslinking in yeast spliceosomes. RNA. 1995;1:968–980. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nilsen T W. RNA-RNA interactions in the spliceosome: unraveling the ties that bind. Cell. 1994;78:1–4. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90563-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Peltz S W, Feng H, Welch E, Jacobson A. Nonsense-mediated decay in yeast. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 1994;47:271–298. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)60254-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pié J, Casals N, Casale C, Buesa C, Mascaro C, Barcelo A, Rolland M, Zabot T, Haro D, Eyskens F, Divry P, Hegardt F G. A nonsense mutation in the 3-hydroxyl-3-methylglutaryl-CoA lyase gene produces exon skipping in two patients of different origin with 3-hydroxyl-3-methylglutaryl-CoA lyase deficiency. Biochem J. 2328;329:335. doi: 10.1042/bj3230329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pintel D J, Dadachanji D, Astell C R, Ward D C. The genome of minute virus of mice, an autonomous parvovirus, encodes two overlapping transcription units. Nucleic Acids Pres. 1983;11:1019–1038. doi: 10.1093/nar/11.4.1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pintel D J, Gersappe A, Haut D, Pearson J. Determinants that govern alternative splicing of parvovirus pre-mRNAs. Semin Virol. 1995;6:283–290. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pulak R, Anderson P. mRNA surveillance by the Caenorhabditis elegans smg genes. Genes Dev. 1993;7:1885–1897. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.10.1885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Santisteban I, Arredondovega F X, Kelly S, Loubser M, Meydan N, Roifman C, Howell P L, Bowen T, Weinberg K I, Shrieder M L, Hershfield M S. Three new adenosine deaminase mutations that define a splicing enhancer and cause severe and partial phenotypes: implications for evolution of a CpG hotspot and expression of a transduced ADA cDNA. Hum Mol Genet. 1995;4:2081–2987. doi: 10.1093/hmg/4.11.2081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schoborg R V, Pintel D J. Accumulation of MVM gene products is differentially regulated by transcription initiation, RNA processing and protein stability. Virology. 1991;181:22–34. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90466-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shiga N, Takeshima Y, Sakamoto H, Inoue K, Yokota Y, Yokoyama M, Matsuo M. Disruption of the splicing enhancer sequence within exon 27 of the dystrophin gene by a nonsense mutation induces partial skipping of the exon and is responsible for Becker muscular dystrophy. J Clin Investig. 1997;100:2204–2210. doi: 10.1172/JCI119757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Simpson S B, Stolzfus C M. Frameshift mutations in the v-src gene of avian sarcoma virus act in cis to specifically reduce v-src mRNA levels. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:1835–1844. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.3.1835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Teigelkamp S, Newman A J, Beggs J D. Extensive interactions of PRP8 protein with the 5′ and 3′ splice sites during splicing suggest a role in stabilization of exon alignment by U5 snRNA. EMBO J. 1995;14:2602–2612. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07258.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Urlaub G, Mitchell P J, Giudad C J, Chasin L A. Nonsense mutations in the dihydrofolate reductase gene affect RNA processing. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9:2868–2880. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.7.2868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhao Q, Gersappe A, Pintel D J. Efficient excision of the upstream large intron from P4-generated pre-mRNA of the parvovirus minute virus of mice requires at least one donor and the 3′ splice site of the small downstream intron. J Virol. 1995;69:6170–6179. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.10.6170-6179.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhao Q, Mathur S, Burger L R, Pintel D J. Sequences within the parvovirus minute virus of mice NS2-specific exon are required for inclusion of this exon into spliced steady-state RNA. J Virol. 1995;69:5864–5868. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.9.5864-5868.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]