Abstract

Background:

The safety of platelet concentrates with longer storage duration has been questioned due to biochemical and functional changes that occur during blood collection and storage. Some studies have suggested that transfusion efficacy is decreased and immune system dysfunction is worsened with increased storage age. We sought to describe the effect of platelet storage age on laboratory and clinical outcomes in critically ill children receiving platelet transfusions.

Study Design and Methods:

We performed a secondary analysis of a prospective, observational point-prevalence study. Children (3 days to 16 years of age) from 82 pediatric intensive care units in 16 countries were enrolled if they received a platelet transfusion during one of the predefined screening weeks. Outcomes (including platelet count increments, organ dysfunction and transfusion reactions) were evaluated by platelet storage age.

Results:

Data from 497 patients were analyzed. The age of the platelet transfusions ranged from 1–7 days but the majority were 4 (24%) or 5 (36%) days of age. Nearly two-thirds of platelet concentrates were transfused to prevent bleeding. The indication for transfusion did not differ between storage age groups (p=0.610). After adjusting for patient and product variables, there was no association between storage age and incremental change in total platelet count or organ dysfunction scoring. A significant association between fresher storage age and febrile transfusion reactions (p=0.002) was observed.

Conclusion:

The results in a large, diverse cohort of critically ill children raise questions about the impact of storage age on transfusion and clinical outcomes which require further prospective evaluation.

Keywords: platelet transfusion, storage age, critical illness, children

INTRODUCTION

Traditionally, platelet concentrates are stored at 20–24°C for up to five to seven days. [1–3] Over time, as the stored platelets age, there are changes in their functional integrity, in their ability to aggregate, activate, and in their effect on immune and endothelial function and microvesiculation. [4, 5] In addition, in vitro studies have shown that older platelet concentrates contain higher levels of inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-8. [6] Platelets of older storage age have been independently associated with adverse outcomes in certain adult cohorts including poorer response to platelet transfusions, [7] increased transfusion reactions, [8] and adverse inflammatory events. [9]

Critically ill children are at particular risk of requiring platelet transfusions because of underlying organ dysfunction, including suppression of bone marrow and/or hepatic insufficiency, administration of medications that may suppress functional ability to clot, platelet consumption due to bleeding or microangiopathy, as well as frequent invasive procedures. Platelet transfusions have been independently associated with increased mortality in this patient population. [10] However, there has been limited work to explore the clinical consequences of transfusing platelet concentrates of older storage age in children.

In this study, we sought to describe the effect of platelet storage age on platelet count increments, organ dysfunction and transfusion reactions in critically ill children requiring platelet transfusions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study is an a priori secondary analysis of a prospective, point-prevalence observational study examining the epidemiology of platelet transfusions in critically ill children (“Point Prevalence Study of Platelet Transfusions in Critically Ill Children,” otherwise known as P3T). The full methodology has been previously published. [10] The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Weill Cornell Medicine, as well as by all participating sites. Eighty-two sites from sixteen countries contributed data. Each site was assigned six random weeks (between September 2016 to April 2017) during which they screened subjects for eligibility and enrollment. A child was enrolled if he/she was between 3 days and 16 years of age and received a platelet transfusion prescribed by the pediatric intensive care team during one of the screening days. Patients were excluded if life expectancy was considered to be less than 24 hours, gestational age of the patient was less than 37 weeks at the time of admission, or the patient had already been enrolled in a previous screening week. In total, 16,934 patients were screened and 559 eligible patients receiving platelet transfusions were enrolled. Data for the P3T study were recorded in the Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap™) web data application and extracted for this secondary analysis.

Data regarding the age of the platelet concentrate were collected from the blood bank for the platelet transfusion administered at time of enrollment but did not include data from every platelet transfusion received during the subject’s PICU stay. If a patient received more than one platelet transfusion on the day of enrollment, the data regarding the platelet concentrate only pertained to the first transfusion. For patients who received multiple platelet transfusions in the same day or pooled platelets, their results were only included in the analysis if the age of units was the same. The storage age was analyzed both as a categorical variable in three groups: 1–2 days, 3–4 days and 5–7 days of age, as well as a continuous variable. ABO incompatibility was defined as follows. A transfusion was considered to have major incompatibility if platelets from A, B or AB donors were given to O recipients, or from AB donors given to A or B recipients. Transfusions with bidirectional incompatibility (A donor to B recipient or B donor to A recipient) were included in the major incompatibility group. Minor incompatibility was defined as platelets from O donors to A, B or AB recipients, or from A or B donors to AB recipients.[11]

Data collected included patient demographics, reason for admission, any prior platelet transfusions during the current ICU admission, validated measures of organ dysfunction (PELOD-2 scoring),[12] information regarding the platelet product (including the storage age of the platelet concentrate), and any adverse reactions that occurred during the transfusion. Organ dysfunction was assessed by the change in PELOD-2 scoring 24 hours before and 24 hours following the platelet transfusion of interest. The adverse reactions were documented via passive reporting and included fever of ≥ 38.5C, hypotension, bronchospasm, urticaria, and hemolytic reactions. The total platelet count before and after transfusion was recorded if obtained as standard of care. The timing of the assays was determined by the medical team. The pre-transfusion platelet count was measured within 36 hours of start of the transfusion and recorded according to the following time intervals: < 1 hour, 1–2 hours, 2–6 hours, 6–12 hours, 12–24 hours and 24–36 hours. The timing of the post-transfusion platelet count was recorded in relation to the completion of the transfusion of interest with the same time intervals as listed above. The corrected count increment (CCI) was calculated for those patients in whom a post-transfusion platelet count was obtained less than one hour after the completion of the transfusion.

Demographic and clinical characteristics were described as counts and percentages or median and interquartile range (IQR) as appropriate. Categorical variables were compared using either Chi-squared or Fisher’s exact test, depending on the size of the sample. Continuous variables were compared using Kruskal Wallis test. Two-sided p values below 0.05 were considered significant and there was no adjustment made for multiple comparisons.

Multivariable linear and logistic models were developed to assess the association between storage duration (as a continuous variable) and clinical outcomes (incremental platelet count change, change in PELOD-2 score and transfusion reactions). Variables were considered potential predictors if they were associated with the outcome in univariate analysis (p<0.10). The final model was selected using a bidirectional step-wise selection on the potential predictors with a significance criterion of p <0.05 to enter in the model and p >0.1 to be removed. All analyses were conducted using SPSS version 25 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY).

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

Four hundred and ninety-seven enrolled patients had complete storage age data and were included in the analysis. The patients were treated in the following locations: 349/497 (70%) in North America, 76/497 (15%) in Europe, 33/497 (7%) in Oceania, 26/497 (5%) in Asia, and 13/497 (3%) in the Middle East. Fifty-six percent (277/497) were male with a median (IQR) age of 3.9 (0.5–10.6) years. The most common admitting diagnoses were respiratory insufficiency/failure (199/497, 40%), septic shock (109/497, 22%), and cardiac bypass surgery (65/497, 13%). Nearly two-thirds of platelet concentrates were transfused to prevent bleeding (prophylaxis, 321/497, 65%) as opposed to treat bleeding (therapeutic, 176/497, 35%).

Storage Age and Patient Characteristics

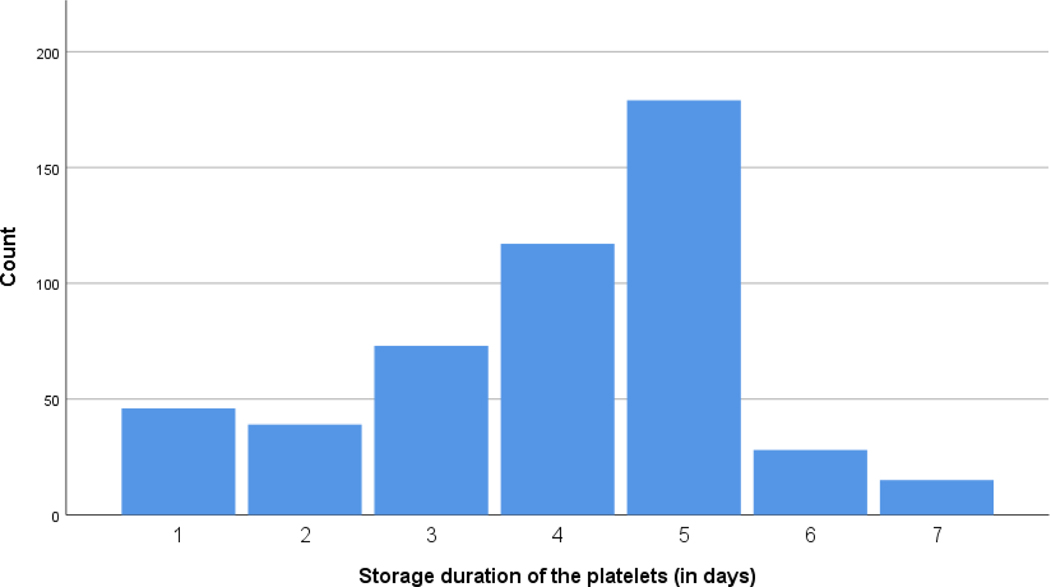

Figure 1 describes the storage ages of the platelet concentrates transfused. The majority were either 4 (117/497, 24%) or 5 (179/497, 36%) days of age. Table 1 describes the demographics and clinical characteristics of the patients by storage age of platelets received at time of enrollment. Patients who received the oldest category of platelet transfusions had been admitted for a longer period of time prior to enrollment as compared to patients who received fresher platelet transfusions (p=0.04). In addition, patients who received the oldest category of platelet transfusions were more likely to have received a platelet transfusion prior to enrollment as compared to the other groups (p=0.002) but for those who had received a prior platelet transfusion, there was no difference in the doses received between the three groups (p=0.41). Those patients with septic shock as an admitting diagnosis were more likely to receive fresher platelets (p<0.01). The indication for transfusion did not differ between storage age groups (p=0.61).

Figure 1.

Distribution of Storage Age of Platelet Concentrates Transfused

Table 1.

Patient demographics and clinical characteristics by storage age of platelets received at time of enrollment

| Patient Variable | 1–2 days of age (n = 85) | 3–4 days of age (n = 191) | 5–7 days of age (n = 221) | p-Values |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr), median (IQR) | 4.6 (0.5–9.8) | 3.5 (0.8–9.0) | 4.1 (0.5–11.1) | 0.69 |

| Sex (male), n (%) | 44 (52) | 104 (55) | 129 (58) | 0.52 |

| Days since admission, median (IQR) | 1 (0–4) | 2 (0–6) | 3 (0–9) | 0.04 |

| Mechanical ventilation, n (%) | 56 (66) | 119 (62) | 147 (67) | 0.22 |

| Underlying oncologic diagnosis, n (%) | 30 (35) | 82 (43) | 98 (44) | 0.35 |

| PELOD-2 Score prior to transfusion, median (IQR) | 7 (4–10) | 7 (4–9) | 7 (5–9) | 0.32 |

| Reason for PICU Admission, n (%): | ||||

| Organ Failure | ||||

| Respiratory insufficiency/failure | 39 (46) | 74 (39) | 86 (39) | 0.48 |

| Renal failure | 12 (14) | 19 (10) | 18 (8) | 0.29 |

| Hepatic failure | 4 (5) | 11 (6) | 9 (4) | 0.73 |

| Shock | ||||

| Septic shock | 31 (37) | 42 (22) | 36 (16) | <0.01 |

| Hemorrhagic shock | 1 (1) | 13 (7) | 17 (8) | 0.1 |

| Other shock | 2 (2) | 12 (6) | 9 (4) | 0.31 |

| Trauma | 1 (1) | 7 (4) | 6 (3) | 0.51 |

| Cardiac | ||||

| Cardiac surgery-bypass | 9 (11) | 27 (14) | 29 (13) | 0.72 |

| Cardiac surgery-no bypass | 0 (0) | 4 (2) | 4 (2) | 0.42 |

| Cardiac – non-surgical | 8 (9) | 16 (8) | 24 (11) | 0.69 |

| Post-operative | ||||

| Emergency surgery | 3 (4) | 11 (6) | 4 (2) | 0.1 |

| Elective surgery | 0 (0) | 13 (7) | 11 (5) | 0.05 |

| Post-op liver transplant | 1 (1) | 3 (2) | 8 (4) | 0.29 |

| Neurosurgical | ||||

| Traumatic brain injury | 1 (1) | 5 (3) | 3 (1) | 0.56 |

| Intracranial bleed/intracranial hypertension | 1 (1) | 5 (3) | 6 (3) | 0.72 |

| Neurologic | ||||

| Seizure | 3 (4) | 7 (4) | 3 (1) | 0.29 |

| Encephalopathy | 10 (12) | 9 (5) | 19 (9) | 0.1 |

| Meningitis | 0 (0) | 4 (2) | 1 (1) | 0.15 |

| Veno-occlusive disease | 0 (0) | 2 (1) | 5 (2) | 0.28 |

| New leukemia/hyperleukocytosis | 4 (5) | 5 (3) | 9 (4) | 0.62 |

| Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis | 1 (1) | 2 (1) | 3 (1) | 0.96 |

| Therapies Received, n (%) | ||||

| Medications | ||||

| Milrinone | 14 (17) | 29 (15) | 41 (19) | 0.66 |

| Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agent | 0 (0) | 5 (3) | 5 (2) | 0.34 |

| Aspirin | 0 (0) | 5 (3) | 8 (4) | 0.21 |

| Devices | ||||

| Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation | 9 (11) | 33 (17) | 36 (16) | 0.35 |

| Continuous renal replacement therapy | 8 (9) | 23 (12) | 21 (10) | 0.66 |

| Intermittent hemodialysis | 2 (2) | 2 (1) | 4 (2) | 0.69 |

| Molecular adsorbent circulating system | 0 (0) | 2 (1) | 3 (1) | 0.57 |

| Received platelet transfusion prior to enrollment, n (%) | 17 (20) | 64 (34) | 92 (42) | 0.002 |

| Median (IQR) dose (mL/kg) of platelet transfusions received prior to enrollment * | 15 (8–38) | 25 (12–67) | 43 (14–105) | 0.41 |

Calculated only for those patients who had received at least one platelet transfusion prior to enrollment. Admitting diagnoses were not mutually exclusive and patients may have had more than one diagnosis on admission.

P-values comparing medians were calculated using Kruskal Wallis test and categorical variables using Chi-square test.

Transfusion Product Characteristics

Table 2 describes the characteristics of the platelet concentrates grouped by storage age. There were differences in the source of platelets (apheresis versus whole-blood derived) (p<0.001), leukoreduction (p=0.048), volume reduction (p<0.001), pathogen-inactivation (p=0.001) and ABO compatibility (p=0.016) between the three storage age groups. The median (IQR) dose of platelet concentrates transfused was 9 (5–13) mL/kg and did not differ across storage age groups (p=0.73).

Table 2.

Characteristics of the platelet concentrates grouped by storage age

| Transfusion Variable | 1–2 days of age (n = 85) | 3–4 days of age (n = 191) | 5–7 days of age (n = 221) | p-Values |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source | ||||

| Apheresis | 58 (68) | 179 (94) | 194 (88) | <0.001 |

| Whole blood derived | 27 (32) | 12 (6) | 27 (12) | |

| Leukoreduction | 78 (92) | 180 (94) | 215 (97) | 0.048 |

| Irradiation | 67 (79) | 153 (80) | 176 (80) | 0.890 |

| HLA-matched | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 2 (1) | 0.328 |

| Volume reduced (washed) | 23 (27) | 7 (4) | 11 (5) | <0.001 |

| Pathogen inactivation | 2 (2) | 6 (3) | 18 (8) | 0.001 |

| ABO compatibility | ||||

| Compatible | 60 (71) | 124 (65) | 135 (61) | 0.016 |

| Major incompatibility | 13 (15) | 50 (26) | 65 (29) | |

| Minor incompatibility | 2 (2) | 9 (5) | 13 (6) | |

| Unknown | 10 (12) | 8 (4) | 8 (4) |

All values represent n (%). P-values comparing categorical variable were calculated using Chi-square test.

Unadjusted Clinical Outcomes

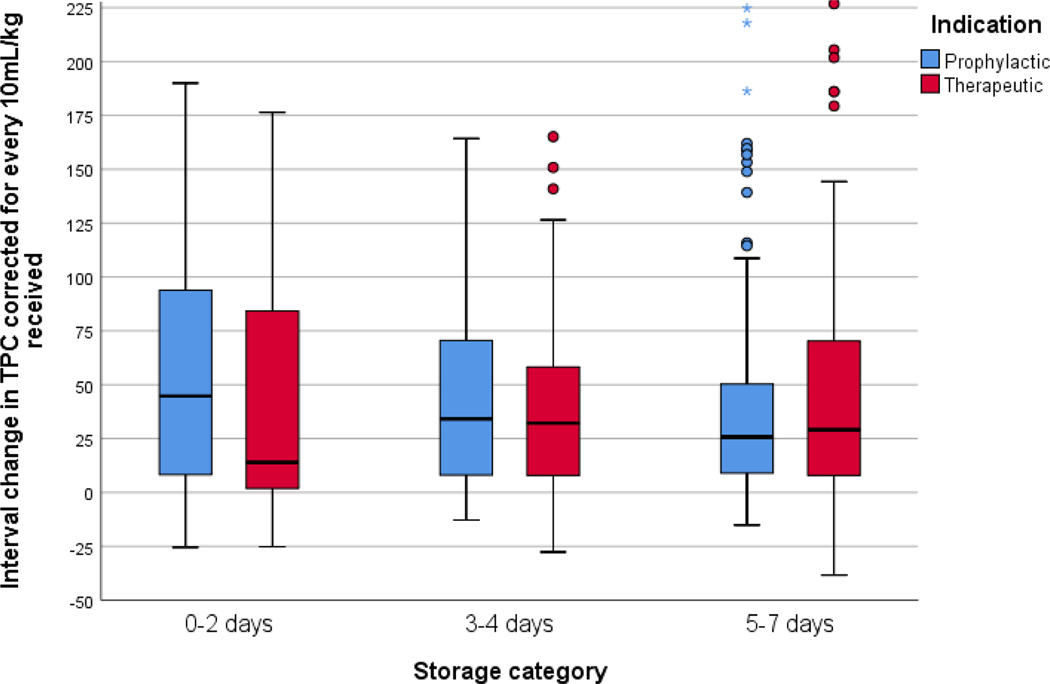

The median (IQR) incremental change in total platelet count (corrected for every 10mL/kg of platelet concentrate transfused) was 27 (8–67) x109 cells/L. This value did not differ between platelet storage age groups broken down for indication (see Figure 2). The patients had post-transfusion platelet counts assayed in the following time intervals: 41/497 (8%) in less than one hour following transfusion completion, 77/497 (16%) in 1–2 hours, 166/497 (33%) in 2–6 hours, 121/497 (24%) in 6–12 hours, 66/497 (13%) in 12–24 hours, and 11/497 (2%) in 24–36 hours. Three percent of patients (15/497) did not have a post-transfusion platelet count checked within 36 hours of the transfusion. All patients with post-transfusion platelet counts were included in the analysis. In the subset of patients who had post-transfusion platelet counts assayed less than one hour following completion of the transfusion, the median (IQR) CCI was 24 (9–88) x109 cells/L. The CCI did not differ between storage age groups (p=0.60).

Figure 2.

Incremental change in total platelet count observed for each platelet storage age category broken down by indication

The patients had significant organ dysfunction prior to platelet transfusion as represented by a median (IQR) PELOD-2 score of 7 (4–9). However, they did not have significant worsening of their organ dysfunction 24 hours following the transfusion, as represented by a median (IQR) change in PELOD-2 score of 0 (−2 – 1). The change in organ dysfunction scoring was not significantly different between the storage age groups (p=0.19). These results did not change when analysis was repeated for each indication (p=0.63 for therapeutic transfusions and p=0.37 for prophylactic transfusions).

Table 3 demonstrates the rates of transfusion reactions for each storage group. On direct comparison, although rates were relatively low overall, there were increased febrile reactions observed in patients receiving fresher platelet concentrates (p=0.01). There were no hemolytic reactions observed.

Table 3.

Transfusion reactions observed by storage age of platelet concentrates

| Transfusion Reaction | 1–2 days of age (n = 85) | 3–4 days of age (n = 191) | 5–7 days of age (n = 221) | p-Values |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fever | 5 (6) | 7 (4) | 1 (0.5%) | 0.01 |

| Urticaria | 0 (0) | 2 (1) | 1 (0.5%) | 0.55 |

| Bronchospasm | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.5%) | 0.54 |

| Hypotension | 2 (2) | 4 (2) | 6 (3) | 0.92 |

| Hemolytic reaction | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | NC |

All values represent n (%). P-values comparing categorical variable were calculated using Chi-square test. NC = not calculated.

Adjusted Clinical Outcomes

Given the differences in patient characteristics and transfusion characteristics between the storage age groups, multivariable linear and logistic regression models were developed to assess the association between storage duration (as a continuous variable) and clinical outcomes (incremental platelet count change, change in PELOD-2 score and transfusion reactions). After adjusting for days since PICU admission, platelet transfusions prior to enrollment, compatibility, source of platelets (apheresis versus whole-blood derived), leukoreduction, volume-reduction, and pathogen-inactivation, there was no statistically significant association between storage age and incremental change in total platelet count (p=0.23) or organ dysfunction scoring (p=0.33). However, there was a significant association between fresher storage age and febrile transfusion reactions (p=0.002), as shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Multivariable model to evaluate associations between storage age of platelet concentrates and clinical outcomes

| Clinical Outcome | Adjusted OR or β Coefficient (95% CI) | p-Values |

|---|---|---|

| Incremental Change in Total Platelet Count | β = −3.429 (−9.037–2.178) | 0.230 |

| Change in Organ Dysfunction Scoring | β = 0.096 (−0.099–0.291) | 0.333 |

| Febrile Transfusion Reactions | OR = 0.562 (0.342–0.807) | 0.002 |

Storage age analyzed as continuous variable. Reported as Adjusted Odds Ratio (OR) for categorical outcomes or Beta regression coefficient for continuous outcomes. Model adjusted for days since PICU admission, the receipt of platelet transfusions prior to enrollment, compatibility, source of platelets (apheresed versus whole-blood derived), leukoreduction, volume-reduction and pathogen-inactivation.

DISCUSSION

This study reports on an exploratory analysis of the impact of platelet concentrate storage age and clinical outcomes in critically ill children. Patients included represent a diverse cohort based on both location and diagnoses. Though the majority of platelet concentrates were 4 or 5 days old, the storage age of the platelets was widely distributed. There were no differences in the response to platelet transfusions (represented by incremental change in total platelet count) or organ dysfunction based on the storage age of the platelet concentrate. However, the fresher platelet concentrates appeared to be independently associated with more febrile transfusion reactions. These results should be interpreted as hypothesis generating.

Many biochemical and functional changes occur in platelet concentrates over time. Because of the interactions between platelets and their storage containers and conditions, platelet lysis and activation occur with subsequent elevation in lactate dehydrogenase, von Willebrand factor and serotonin. [13–15] Glucose is depleted, lactate accumulates and acidification occurs within the platelet concentrate media over time. [16] In addition, the surface proteins expressed on stored platelets change over time affecting their thrombin sensitivity and they become more sensitized to nitric oxide which impairs their ability to aggregate. [17–19] Counter to the reduced aggregation with increased storage time, the accumulation of platelet microparticles amplifies thrombin formation. [20] All of these changes may impact the clinical outcomes of patients receiving platelet transfusions of differing storage age.

There is a much broader literature assessing the impact of storage age of red cells on clinical outcomes. In view of these concerns highlighted over many years, a number of large pragmatic randomized trials have been completed and published which include ABLE, [21] RECESS, [22] INFORM, [23] TRANSFUSE, [24] and more recently ABC-PICU. [25] No such comparable randomized trials exist for platelet storage age. However, it has been argued that a range of clinical, methodological and statistical problems do affect the analysis and interpretation of trial results for red cell storage age, and indeed the levels of reassurance for clinicians may not be that strong. [26]

A number of studies have identified variable associations between the storage age of platelet concentrates with laboratory parameters and inflammatory adverse events [7–9]. In adults, a cohort study of 381 critically ill trauma patients, reported that exposure to older apheresis platelet concentrates did not impact mortality or rates of acute respiratory distress syndrome, renal or liver failure, but was independently associated with higher rates of sepsis. [27] In contrast, in a larger cohort of more than 2000 adults following aortocoronary bypass surgery, platelet storage age was not associated with 30-day mortality, prolonged hospital stay, or post-operative infections. [28] The differences in these findings may be related to heterogeneity among the recipients or the platelet donors. [29]

Fewer studies have been published that explore a similar association in children. Given the differences in physiology and etiologies of critical illness that exist between children and adults, pediatric patients may have different clinical outcomes associated with the storage age of the platelet concentrates. A sub-analysis of the Platelet Dose (PLADO) Trial, which included non-critically ill children and adults, examined the association between platelet concentrate attributes, including storage age, and the risk of transfusion related adverse events. [30] Though there was no significant association, there appeared to be a trend toward increased transfusion reactions in the freshest platelet concentrates (0–2 days), similar to our findings. While this finding may seem counterintuitive given the increased presence of leukocyte-derived cytokines present in 5-day stored platelets, [6] [31] recent metabolomic studies have shown that platelet concentrates stored for a short period (0–3 days) have decreased mitochondrial function, down regulation of the TCA cycle and the accumulation of ATP degradation products. [32] ATP has been shown to have immunomodulatory effects on cytokines in human whole blood, in particular decreasing the rise in concentrations of TNF-alpha, interferon-gamma and IL-1beta [33]. It is therefore plausible that these metabolic changes may contribute to increased transfusion reactions.

There are important limitations of this study. These are inherent to the design of the main study and the analysis undertaken in this secondary work. The point prevalence study did not collect data for all platelet transfusions received by each enrolled subject during his/her admission; the age of all of the platelet transfusions that a patient received throughout his/her PICU course is unknown. Therefore, the only clinical outcomes that could be assessed in relation to the storage age of the platelet concentrate were the incremental change in platelet count, transfusion reactions and organ dysfunction. Additionally, because of the study design, we could not compare subsequent aliquots transfused from a single donor unit. As an observational study, post-transfusion platelet counts were assessed at the medical team’s discretion and thus not limited to a one hour post-transfusion assessment. We did not assess for clinical signs of platelet refractoriness such as splenomegaly. We did not collect information on pre-transfusion medications administered which may affect the rates of fever. There was a low incidence of any transfusion reactions in our cohort and the original study was not designed to be powered for this specific analysis. There are also multiple other potential confounding factors which may affect the modelling analysis. The analysis takes no consideration of other important variables for the platelet product such as manufacturing methods (collection, processing, and storage solutions). [34–36] It is of interest that one study in Canada highlighted the potential importance of processing and use of additive solutions on clinical outcomes. [37] Each platelet product contains a varying number of platelets which may affect the potential mechanisms through which harmful effect of platelets might be mediated, as demonstrated in other recent randomized trials (PATCH, PlaNeT2).[38, 39] We did not include the assessment of other clinical outcomes associated with transfusion such as thrombosis. Finally, leukoreduction techniques vary between North America and Europe [40] and the effects on the leukocytes present in the platelet concentrates were not assessed. Given the differences in blood bank practices as well as a relative shortage of platelet concentrates, a randomized controlled trial that controlled for other variables and only assessed different storage ages may be difficult to perform. However, a comparative effectiveness study within a larger database would be necessary to confirm our findings.

Our study highlights the potential importance of storage age as a further variable to be explored when considering the effectiveness and safety of platelet transfusions. Whereas we did find increased transfusion reactions with fresher platelet concentrates, we did not find any differences in organ dysfunction or platelet count increments in patients receiving older platelet units. Future work should consider the lessons learned from the literature assessing storage age of red cells, and should assess mechanistic pathways through which storage age may have a clinical impact.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank all the P3T investigators for their contribution, as well as the Clinical Translational Science Center (CTSC) at Weill Cornell Medicine.

P3T investigators: Australia: Warwick Butt, Carmel Delzoppo (Royal Children’s Hospital, Melbourne); Simon Erickson, Elizabeth Croston, Samantha Barr (Princess Margaret Hospital, Perth); Elena Cavazzoni (Children’s Hospital at Westmead, Sydney). Belgium: Annick de Jaeger (Princess Elisabeth Children’s University Hospital, Ghent). Canada: Marisa Tucci, Mary-Ellen French, Marion Ropars, Lucy Clayton (CHU Sainte-Justine, Montreal QC); Srinivas Murthy, Gordon Krahn (British Columbia Children’s Hospital, Vancouver, BC). China: Dong Qu, Yi Hui (Children’s Hospital Capital Institute of Pediatrics, Beijing). Denmark: Mathias Johansen, Anne-Mette Baek Jensen, Inge-Lise Jarnvig, Ditte Strange (Rigshospitalet, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen). India: Muralidharan Jayashree, Mounika Reddy (Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh); Jhuma Sankar, U Vijay Kumar, Rakesh Lodha (All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi). Israel: Reut Kassif Lerner, Gideon Paret (The Edmond and Lily Safra Children’s Hospital, Sheba Medical Center, Ramat Gan); Ofer Schiller, Eran Shostak, Ovadia Dagan (Schneider Children’s Medical Center, Petah Tikva); Yuval Cavari (Soroka University Medical Center, Beersheva). Italy: Fabrizio Chiusolo, Annagrazia Cillis (Bambino Gesu Children’s Hospital, Rome); Anna Camporesi (Children’s Hospital Vittore Buzzi, Milano). Netherlands: Martin Kneyber (Beatrix Children’s Hospital, Groningen); Suzan Cochius-den Otter, Ellen Van Hemeldonck (Erasmus MC- Sophia Children’s Hospital, Rotterdam). New Zealand: John Beca, Claire Sherring, Miriam Rea (Starship Child Health, Auckland). Portugal: Clara Abadesso, Marta Moniz (Hospital Prof. Dr. Fernando Fonseca, Amadora). Saudi Arabia: Saleh Alshehri (King Saud Medical City, Riyadh). Spain: Jesus Lopez-Herce, Irene Ortiz, Miriam Garcia (Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Maranon, Madrid); Iolanda Jordan (Institut de Recerca Hospital Sant Joan de Deu, Barcelona); J Carlos Flores Gonzalez (Hospital Universitario Puerta del Mar, Cadiz); Antonio Perez-Ferrer, Ana Pascual-Albitre (La Paz University Hospital, Madrid). Switzerland: Serge Grazioli (University Hospital of Geneva, Geneva); Carsten Doell (University Children’s Hospital Zurich, Zurich). United Kingdom: Peter J. Davis (Bristol Royal Hospital for Children, Bristol); Ilaria Curio, Andrew Jones, Mark J. Peters (Great Ormond St Hospital NHS Trust and NIHR Biomedical Research Centre, London); Jon Lillie (Evelina London Children’s Hospital, London); Angela Aramburo, Medhat Shabana, Priya Ramachandran, Helena Sampaio (Royal Brompton Hospital, London); Kalaimaran Sadasivam (Royal London Hospital, Barts Health NHS Trust, London); Nicholas J Prince (St George’s Hospital, London); Hari Krishnan Kanthimathinathan (Birmingham Children’s Hospital, Birmingham); Ricardo Garcia Branco (Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Trust, Cambridge); Kim L. Sykes, Christie Mellish (University Hospital Southampton, Southampton); Avishay Sarfatti, James Weitz (Oxford University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Oxford). United States: Ron C. Sanders Jr, Glenda Hefley (Arkansas Children’s Hospital, Little Rock, AR); Rica Sharon P. Morzov, Barry Markovitz (Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA); Anna Ratiu, Anil Sapru (Mattel’s Children’s Hospital, Los Angeles, CA); Allison S. Cowl (Connecticut Children’s Medical Center, Hartford, CT); E. Vincent S Faustino (Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, CT); Shruthi Mahadevaiah (University of Florida Shands Children’s Hospital, Gainesville, FL); Fernando Beltramo (Nicklaus Children’s Hospital, Miami, FL); Asumthia S Jeyapalan, Mary K Cousins (University of Miami/Holtz Children’s Hospital, Miami, FL); Cheryl Stone, James Fortenberry (Children’s Hospital of Atlanta, Atlanta, GA); Neethi P. Pinto, Chiara Rodgers, Allison Kniola (The University of Chicago, Chicago, IL); Melissa Porter, Erin Owen, Kristen Lee, Laura J. Thomas (University of Louisville, Kosair Charities Pediatric Clinical Research Unit, and Norton Children’s Hospital, Louisville, KY); Melania M Bembea, Ronke Awojoodu (Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD); Daniel Kelly, Kyle Hughes (Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston, MA); Zenab Mansoor, Carol Pineda (Tufts Floating Hospital for Children, Boston, MA); Phoebe H Yager, Maureen Clark (Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA); Scot T. Bateman (UMass Memorial Children’s Medical Center, Worcester, MA); Kevin W. Kuo, Erin F. Carlton (C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI); Brian Boville, Mara Leimanis (Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital, Grand Rapids, MI); Marie E. Steiner, Dan Nerheim (University of Minnesota Masonic Children’s Hospital, Minneapolis, MN); Kenneth E. Remy, Lauren Langford, Melissa Schicker (Washington University in St. Louis, St. Louis, MO); Marcy N Singleton, J Dean Jarvis, Sholeen T Nett (Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon, NH); Shira Gertz (Hackensack University Medical Center, Hackensack, NJ); Ruchika Goel (New York Presbyterian Hospital – Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, NY); James S. Killinger, Meghan Sturnhahn (Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY); Margaret M. Parker, Ilana Harwayne-Gidansky (Stony Brook Children’s Hospital, Stony Brook, NY); Laura A. Watkins (Cohen Children’s Medical Center, Northwell Health, Queens, NY); Gina Cassel, Adi Aran, Shubhi Kaushik (The Children’s Hospital at Montefiore, Bronx, NY); Andy Y. Wen (NYU Langone Medical Center, NYU School of Medicine, New York, NY); Amanda B. Hassinger (Women and Children’s Hospital of Buffalo, Buffalo, NY); Caroline P. Ozment, Candice M. Ray (Duke Children’s Hospital and Health Center, Durham, NC); Michael C. McCrory, Andora L Bass (Wake Forest Brenner Children’s Hospital, Winston-Salem, NC); Michael T Bigham, Heather Anthony (Akron Children’s Hospital, Akron, OH); Jennifer A. Muszynski, Jill Popelka (Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Columbus, OH); Julie C. Fitzgerald, Susan Doney Leonard (Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, PA); Neal J. Thomas, Debbie Spear (Penn State Hershey Children’s Hospital, Hershey, PA); Whitney E. Marvin (Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC); Arun Saini; Alina Nico West (University of Tennessee Health Science Center and Le BonHeur Children’s Hospital, Memphis, TN); Jennifer McArthur, Angela Norris, Saad Ghafoor, Ashlea Anderson (St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, Memphis, TN); Tracey Monjure, Kris Bysani (Medical City Children’s Hospital, Dallas, TX); LeeAnn M. Christie (Dell Children’s Medical Center, Austin, TX); Laura L Loftis (Baylor College of Medicine, Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston, TX); Andrew D. Meyer, Robin Tragus, Holly Dibrell, David Rupert (University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, San Antonio, TX); Claudia Delgado-Corcoran, Stephanie Bodily (University of Utah, Primary Children’s Hospital, Salt Lake City, UT); Douglas Willson (Children’s Hospital of Richmond at VCU, Richmond, VA); Leslie A. Dervan (Seattle Children’s, University of Washington, Seattle, WA); Sheila J. Hanson (Medical College of Wisconsin/ Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI); Scott A. Hagen, Awni M. Al-Subu (University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, Madison, WI).

Financial Support: This project was supported in part by funds from the Clinical Translational Science Center (CTSC), National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) grant #UL1-TR000457.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: Drs. Cushing and Spinella received funding for research from Cerus Corporation. Dr. Spinella is a consultant for Secure Transfusion Services. The remaining authors have disclosed that they do not have any potential conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Greening DW, Glenister KM, Sparrow RL, Simpson RJ. International blood collection and storage: clinical use of blood products. J proteomics 2010, 73(3):386–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.de Vries R, Haas F. English translation of the Dutch Blood Transfusion guideline 2011. Vox sang 2012, 103(4):363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Slichter SJ, Bolgiano D, Corson J, Jones MK, Christoffel T, Pellham E. Extended storage of autologous apheresis platelets in plasma. Vox sang 2013, 104(4):324–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seghatchian J, Krailadsiri P. Platelet storage lesion and apoptosis: are they related? Transfus apher sci 2001, 24(1):103–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miyazawa B, Trivedi A, Togarrati PP, et al. Regulation of endothelial cell permeability by platelet-derived extracellular vesicles. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2019, 86(6):931–942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stack G, Snyder EL. Cytokine generation in stored platelet concentrates. Transfusion 1994, 34(1):20–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caram-Deelder C, Kreuger AL, Jacobse J, van der Bom JG, Middelburg RA. Effect of platelet storage time on platelet measurements: a systematic review and meta-analyses. Vox sang 2016, 111(4):374–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kreuger AL, Caram-Deelder C, Jacobse J, Kerkhoffs JL, van der Bom JG, Middelburg RA. Effect of storage time of platelet products on clinical outcomes after transfusion: a systematic review and meta-analyses. Vox sang 2017, 112(4):291–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Losos M, Biller E, Li J, et al. Prolonged platelet storage associated with increased frequency of transfusion-related adverse events. Vox sang 2018, 113(2):170–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nellis ME, Karam O, Mauer E, et al. Platelet Transfusion Practices in Critically Ill Children. Crit care med 2018, 46(8):1309–1317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nellis ME, Goel R, Karam O, et al. Effects of ABO Matching of Platelet Transfusions in Critically Ill Children. Pediatr crit care med 2019; 20(2):e61–e69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leteurtre S, Duhamel A, Deken V, Lacroix J, Leclerc F. Daily estimation of the severity of organ dysfunctions in critically ill children by using the PELOD-2 score. Crit care 2015, 19:324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van der Meer PF, de Korte D. Platelet preservation: agitation and containers. Transfus Apher Sci 2011; 44:297–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Snyder EL, Hezzey A, Katz AJ, Bock J. Occurrence of the release reaction during preparation and storage of platelet concentrates. Vox Sang 1981; 41:172–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maurer-Spurej E, Pfeiler G, Maurer N, Lindner H, Glatter O, Devine DV. Room temperature activates human blood platelets. Lab Investig 2001; 81: 581–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Slichter SJ. Preservation of platelet viability and function during storage of concentrates Prog Clin Biol Res 1978; 28: 83–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lozano ML, Rivera J, Gonzalez-Conejero R, Moraleda JM, Vicente V. Loss of high-affinity thrombin receptors during platelet concentrate storage impairs the reactivity of platelets to thrombin. Transfusion 1997; 37: 368–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schlagenhauf A, Kozma N, Leschnik B, Wagner T, Muntean W. Thrombin receptor levels in platelet concentrates during storage and their impact on platelet functionality. Transfusion 2012; 52: 1253–1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kobsar A, Klinker E, Kuhn S, et al. Increasing susceptibility of nitric oxide-mediated inhibitory platelet signaling during storage of apheresis-derived platelet concentrates. Transfusion 2014; 54: 1782–1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keuren JF, Magdeleyns EJ, Govers-Riemslag JW, Lindhout T, Curvers J. Effects of storage-induced platelet microparticles on the initiation and propagation phase of blood coagulation. Br J Haematol 2006; 134: 307–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lacroix J, Hebert PC, Fergusson DA, et al. Age of transfused blood in critically ill adults. N Engl J Med 2015, 372(15):1410–1418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Steiner ME, Ness PM, Assmann SF, et al. Effects of red-cell storage duration on patients undergoing cardiac surgery. N Engl J Med 2015, 372(15):1419–1429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heddle NM, Cook RJ, Arnold DM, et al. Effect of Short-Term vs. Long-Term Blood Storage on Mortality after Transfusion. N Engl J Med 2016, 375(20):1937–1945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Irving A, Higgins A, Ady B, et al. Fresh Red Cells for Transfusion in Critically Ill Adults: An Economic Evaluation of the Standard Issue Transfusion Versus Fresher Red-Cell Use in Intensive Care (TRANSFUSE) Clinical Trial. Crit care med 2019, 47(7):e572–e579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spinella PC, Tucci M, Fergusson DA, et al. Effect of Fresh vs Standard-issue Red Blood Cell Transfusions on Multiple Organ Dysfunction Syndrome in Critically Ill Pediatric Patients: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2019, 322(22):2179–2190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Trivella M, Stanworth SJ, Brunskill S, Dutton P, Altman DG. Can we be certain that storage duration of transfused red blood cells does not affect patient outcomes? BMJ 2019, 365:l2320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Inaba K, Branco BC, Rhee P, et al. Impact of the duration of platelet storage in critically ill trauma patients. J Trauma 2011, 71(6):1766–1773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Welsby IJ, Lockhart E, Phillips-Bute B, et al. Storage age of transfused platelets and outcomes after cardiac surgery. Transfusion 2010, 50(11):2311–2317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kelly AM, Garner SF, Foukaneli T, et al. The effect of variation in donor platelet function on transfusion outcome: a semirandomized controlled trial. Blood 2017, 130(2):214–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kaufman RM, Assmann SF, Triulzi DJ, et al. Transfusion-related adverse events in the Platelet Dose study. Transfusion 2015, 55(1):144–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hartwig D, Hartel C, Hennig H, Muller-Steinhardt M, Schlenke P, Kluter H. Evidence for de novo synthesis of cytokines and chemokines in platelet concentrates. Vox sang 2002, 82(4):182–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Paglia G, Sigurjónsson ÓE, Rolfsson Ó, et al. Comprehensive metabolomic study of platelets reveals the expression of discrete metabolic phenotypes during storage. Transfusion. 2014; 54(11):2911–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Swennen EL, Coolen EJ, Arts IC, Bast A, Dagnelie PC. Time-dependent effects of ATP and its degradation products on inflammatory markers in human blood ex vivo. Immunobiology. 2008; 213(5):389–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johannsson F, Guethmundsson S, Paglia G, et al. Systems analysis of metabolism in platelet concentrates during storage in platelet additive solution. Biochem J 2018, 475(13):2225–2240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van Hout FMA, van der Meer PF, Wiersum-Osselton JC, et al. Transfusion reactions after transfusion of platelets stored in PAS-B, PAS-C, or plasma: a nationwide comparison. Transfusion 2018, 58(4):1021–1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shea SM, Thomas KA, Spinella PC. The effect of platelet storage temperature on haemostatic, immune, and endothelial function: potential for personalised medicine. Blood Transfus. 2019;17(4):321–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Heddle NM, Arnold DM, Acker JP, et al. Red blood cell processing methods and in-hospital mortality: a transfusion registry cohort study. Lancet Haematol 2016, 3(5):e246–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baharoglu MI, Cordonnier C, Al-Shahi Salman R, et al. Platelet transfusion versus standard care after acute stroke due to spontaneous cerebral haemorrhage associated with antiplatelet therapy (PATCH): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2016, 387:2605–2613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Curley A, Stanworth SJ, Willoughby K, et al. Randomized Trial of Platelet-Transfusion Thresholds in Neonates. N Engl J Med 2019January17;380(3):242–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Greening DW, Sparrow RL, Simpson RJ. Preparation of platelet concentrates. Methods Mol Biology 2011, 728:267–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]