Abstract

The study aimed to understand the nature and context of mental health stigma among people living with a mental health condition and the subsequent effect on their caregivers. Semi-structured qualitative face to face interviews were conducted by trained mental healthcare professionals with mental health service users (n = 26) and caregivers (n = 24) in private rooms at a tertiary health facility, where service users were admitted. Following transcription and translation, data was analysed using framework analysis. There was limited knowledge about their mental health diagnosis by service users and generally low mental health literacy among service users and caregivers. Mental health service users reported experiences of stigma from their own families and communities. Caregivers reported withholding the patient’s diagnosis from the community for fear of being stigmatised, and this fear of stigma carries the risk of negatively affecting care treatment-seeking. Limited mental health knowledge, coupled with a high prevalence of perceived family and community stigma among caregivers and service users, impedes the capacity of caregivers to effectively cope in supporting their family members living with mental illness. There is a need for interventions to provide psychoeducation, reduce community stigma, and support coping strategies for caregivers and people with mental health conditions.

Keywords: Mental health stigma, Caregivers, Mental health service users, Burden of care, Coping mechanisms

Introduction

Mental health conditions have been gradually increasing over the past decades and now reported as a significant contributor towards disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) (Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, 2018). Despite an improved public attitude towards mental health, limited attention persists (Angermeyer et al., 2017). Stereotypes surrounding mental health persist globally (Egbe et al., 2014), impeding mental health services access and utilisation. Academic contributions towards the global mental health agenda to promote uptake and improvement of services have increased (Patel et al., 2018). The World Health Organisation (WHO) developed the 2019–2023 Special Initiative for Mental Health to reiterate the significance of comprehensive, integrated, and responsive community-based mental health services (WHO, 2019). These global efforts aim to build on the momentum and progress achieved to date, especially in developing countries where funding for mental health services remains constrained (Monnapula-Mazabane et al., 2021).

In sub-Saharan Africa, mental health disorders are responsible for approximately 13.6 million DALYs and a total of 9% of the non-communicable diseases (NCDs) burden (Gouda et al., 2019). The burden of mental illness in South Africa is explicitly reported to be high, with a lifetime prevalence of mental health disorders estimated to be one in three (A. A. Herman et al., 2009). In the face of this high burden, the treatment gap is large, with an estimated 75% of people living with mental illness not accessing treatment of any kind (Williams et al., 2008). The South African Mental Health Care Policy Framework and Strategic Plan (2013–2020) provides policy guidance to narrow this treatment gap through integrating mental health into primary health care and strengthening community-based mental health services.

Community mental health services comprise ‘formal’ services to support the re-integration of discharged service users into their communities. These services include day-care, supervised residential services, halfway houses, group homes, rehabilitation services, and mobile crisis teams. In Africa, including in South Africa, these ‘formal’ community services are, however, scarce, with a reliance on informal community mental health services, provided by natural caregivers or family members in the community (Dako-Gyeke & Asumang, 2013; MacGregor, 2018; Mavundla et al., 2009). Within this context, where family members become the main, if not the only support, for mental health service users (Dako-Gyeke & Asumang, 2013; MacGregor, 2018; Mavundla et al., 2009), the role played by mental health stigma in hampering the capacity of these natural caregivers within Africa communities requires urgent attention.

Mental health stigma constitutes negative stereotypes and beliefs against people with mental illness (Corrigan, 2004). Stigma is a multifaceted construct composed of problems linked to knowledge, attitudes, and behaviour (Thornicroft, 2006). Associate stigma is prejudice and discrimination against people who do not have a mental illness because they have a social relationship with a person living with a mental illness (Corrigan, Watson, & Miller, 2006). When family members internalise associate stigma, it is termed affiliate stigma (Mak & Cheung, 2012).

Families of individuals living with a mental illness are vulnerable to stigma by association (Nxumalo & Mchunu, 2017), and are vulnerable to negative emotions similar to those with mental illness, e.g. low self-esteem, shame, anger. In Africa, mental illness is associated with certain cultural beliefs and traditions (Egbe et al., 2014; Petersen & Lund, 2011) and has been found to impede access to health care services (Assefa et al., 2012; Corrigan, 2004; Egbe et al., 2014; Lund et al., 2012), as well as militating against integration of people with mental illness within society (Dako-Gyeke & Asumang, 2013; Egbe et al., 2014; Nxumalo & Mchunu, 2017).

There have been some recent mental health stigma reduction interventions in Africa, such as a current community campaign to curb mental health stigma in Ghana and Kenya (Potts & Henderson, 2021). Literature on mental health stigma reduction interventions for family caregivers, however, remains sparse globally. A recent review reported only a few family interventions (Morgan et al., 2018). Stigma interventions in developing countries have primarily focused on HIV/AIDS and only 3% on mental health (Kemp et al., 2019). Studies in developed countries that evaluated stigma attitudes by ethnicity suggested higher stigmatising attitudes among Asians and Africans (Abdullah & Brown, 2011; L. H. Yang et al., 2013). The aim of this study was thus to understand the differential experiences of mental health stigma from service users and their family caregivers, with the view to inform the development of a family-focused anti-stigma intervention that could assist informal caregivers within families in their caregiving roles and ultimately the social integration of mental health service users into society.

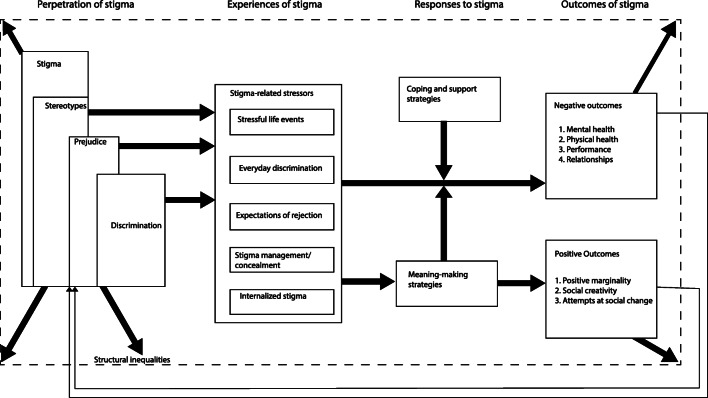

Frost’s Process Model of Stigma (Frost, 2011), shown below in Fig. 1, guided the study. Frost highlights those certain collective representations of meaning fuel the perpetuation of stigma in a society which includes shared values, beliefs, and ideologies that promote stereotyping and prejudice against certain groups of people- leading to acts of discrimination (Reupert, 2017). The process model guided the interview structure from stigma experiences, coping mechanisms and impacts of stigma experiences. For contextualisation and addressing research questions, two themes were added to interviews by the researcher, i.e., mental health knowledge and caregiver support recommendations.

Fig. 1.

Process Model for Stigma (Frost, 2011)

Methods

Qualitative Approach

A qualitative descriptive approach using framework analysis was used to gain an in-depth contextual understanding of mental health stigma experiences among service users and their caregivers. The framework analysis approach, commonly used in health services and policy research, was used to clarify how data moved from interview transcripts to themes for an in-depth understanding of the study findings (Ritchie & Spencer, 2002).

Sample and Sampling Strategy

Purposive sampling was used to identify service users and caregivers of Black/African ethnicity for inclusion in the study. Participants were accessed from Witrand Hospital, which is a provincial psychiatric hospital in the North West province of South Africa. Respondents were identified by accessing the health facility register of service users admitted to Witrand Hospital who had a mental illness and had previously been admitted to the hospital. After the service users’ conditions were confirmed to be stabilised by the treating psychiatrist and psychologist, a mental health status examination was administered by the researcher, a qualified clinical psychologist with experience in working with service users with severe mental illness, to ascertain participants’ capacity to understand the informed consent process and understand the interview questions. Fifty-six interviews were conducted, which comprised 32 service users previously admitted to Witrand Hospital and 24 family caregivers not necessarily related to the 32 service users. Of the 32 services users, three were deemed unfit to continue with the study after demonstrating challenges in fully understanding the interview questions, and three withdrew, leaving a total of 26. The 50 completed interviews were included in the data analysis. All participants were over the age of 18 years old (Table 1).

Table 1.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

|

• Black/African ethnicity. • Aged over 18 years. • Previously admitted and discharged from a mental health facility. • The mental state evaluation shows a stable condition and ability to understand fully. • Informed consent is given |

• Non-African ethnicities. • Minors or the elderly. • Participant not previously admitted at the facility. • The evaluation shows mental or emotional instability and or limited capacity to understand fully. • Informed consent is not given. |

Data Collection Methods

The interviews lasted 45–75-min with service users and caregivers and were conducted between December 2019 and January 2020. All interviews with caregivers and service users were conducted at the health facility in a private space. Interviewers ensured that respondents were comfortable within the setting prior to the interview. After a verbal explanation about the study objectives, including the willingness to opt-out of the study at any point in time, written consent to participate in the study and record the interview was sought from all the respondents prior to the interviews. All interviews were conducted in the respondents’ language of choice (English or Setswana) and were audio-recorded. One interviewer was a clinical psychologist, and the other a qualified and certified psychological counsellor. Both interviewers had experience working with service users.

Two interview guides were developed for use during interviews, with one for caregivers and one for service users, including possible probes. Caregivers were asked questions such as “As someone taking care of a loved one with mental illness, have you experienced negative attitudes from your family, community members or people you closely interact with?”. Further probing questions were used, e.g., “If yes, can you describe what happened?” and “What was your reaction?” In addition, the interviewers wrote down field notes in journals to contextualise responses during data analysis.

Data Analysis

Data analysis followed the 7-step framework analysis for multi-disciplinary health sciences research (Gale et al., 2013). The first step of the framework analysis is data transcription. Interviews conducted in local languages were translated and transcribed by data collectors verbatim to English before data analysis with back translation checks applied. The researcher reviewed and verified the transcriptions against the audio recordings.

After transcription to English, the researcher familiarised herself with the interview transcripts and journal notes (i.e., observation or field notes) written by interviewers during data collection. Frost’s (2011) process model guided the initial data coding framework. After familiarisation with the first few transcribed interviews, additional thematic issues were identified and used to build on this initial coding structure. This coding structure was then applied to the rest of the interviews and adapted as additional themes emerged. NVivo 11 was used to apply the analytical framework to all transcripts from caregivers and service users and chart the data into the framework matrix. Initial notes on data interpretation were written within NVivo 11 and used in making final inferences from the data. Findings are reported according to the analytical framework, and quotes were taken as is without any manipulation by the researcher.

Trustworthiness

Assessment of methodological rigour followed the guideline for qualitative studies that address transferability, reliability, credibility, and confirmability (Forero et al., 2018). Transferability was considered before developing the sampling strategy for study respondents. To optimise reliability, the assistant interviewer was trained to understand the research objectives and the data collection tools to ensure uniformity and non-ambiguity in the research questions. The training covered probing techniques in such a manner that follow-up questions were asked similarly. Interviews were conducted within private rooms at the mental health hospital facility. The researcher and assistant had no previous relationships with the respondents selected for the study.

Credibility in qualitative research aims to ensure that findings are accurate from the perspectives of study respondents. To ensure credibility, interviewers were trained to double-check responses by reiterating the points raised by study participants and noting any added clarifications. Participant responses that involved non-verbal cues were repeated to participants as the interviewer had understood it, allowing the respondent to clarify any misunderstanding or miscommunication. In addition, interviewers kept reflective journals to capture critical interpretations during interviews and contribute to accurate and balanced inferences.

Confirmability of the study findings was done to increase the research confidence in the study findings. For this, the study used peer checking. Samples of translated interviews with respondents and journal notes taken during data transcription and analysis were shared with another experienced researcher for their inferences from the data. The inferences from peer checking were discussed and used during data interpretation to contextualise responses from respondents.

Ethical Issues

The University of Kwa-Zulu Natal approved the research study through the Biomedical Research Committee under the reference number: BFC 133/19. The gatekeeper’s approval was obtained from the Department of Health North West Province and Witrand Hospital Management. Participants (mental health service users and caregivers) were informed that the study was voluntary and assured they were free to withdraw at any given point in time. After treating psychologists at the health facility had provided an assessment that a service user was stable and coherent, the research team conducted a primary mental health status check before recruiting the service users into the study. All participants were provided written informed consent and permission to report findings, following an explanation of the research in their first language. The interviews were conducted in a private room, and all personal identifying information was removed from the data. Hard copies of interview transcripts were stored in a locked office, and soft copies were stored on password-protected computers.

Results

The demographics of respondents are summarised in the table below. Most caregivers (67%) were female, while most service users (65%) were male. Unemployment was high among caregivers (58%). Substance-induced depressive disorders were the most common diagnosis (50%), followed by bipolar (23%) and depression (19%).

| Demographics | Service Users n (%) | Caregivers n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 9 (35) | 16 (67) |

| Male | 17 (65) | 8 (33) | |

| Ethnicity | Black | 26 (100) | 24 (100) |

| Age | 18–19 | 3 (12) | 0 |

| 20–24 | 6 (24) | 1 (4) | |

| 25–30 | 7 (28) | 1 (4) | |

| 31–40 | 3 (12) | 4 (17) | |

| 41–50 | 3 (12) | 11 (46) | |

| 51–60 | 3 (12) | 7 (29) | |

| Clinical diagnosis | Bipolar | 6 (23) | N/A |

| Depression | 5 (19) | N/A | |

| Schizophrenia | 2 (8) | N/A | |

| Substance-induced depression | 13 (50) | N/A | |

| Employment | Employed | . | 10 (42) |

| Unemployed | . | 14 (58) | |

The study findings were grouped into 6 themes across different aspects of stigma. They included the role of mental health knowledge and stigma, perceived community misconceptions on mental health, mental health stigma coping strategies, impacts of mental health stigma on family support/caregiving, and caregiver support needs to deal with stigma. Each theme was categorised to show responses from service users and caregivers, except for 2 themes, i.e., impacts of mental health stigma on family support/caregiving and caregiving caregiver support needs to deal with stigma, which was explicitly relevant for family caregivers.

Knowledge about Mental Illness

Mental Health Knowledge among Service Users

The majority of service users (n = 24) responded by briefly describing mental illness using terms such as “brain dysfunction”, “disabled”, and “failing to cope in the community”.

"What I understand is that mental illness is an illness that sometimes you're not even sure that you suffer from it... Your mind becomes disturbed by things like stress. Sometimes it's like you lose control of your mind; you start hearing noises." ~ SU 01

Service users further identified some of the common symptoms of mental illness.

"It is about people who have problems with the processes and neurotransmitters in their brain; there is a chemical imbalance in their brain. One minute you are happy, talkative and you make plans; the next minute you are depressed, sad, you do not want to do anything, you do not want to talk to anyone." ~ SU 05

Service users’ perceptions of the illness’s treatment outcomes and whether the illness would go away were varied among service users, where most were unsure if mental illness could be cured or go away. However, they felt optimistic and were hopeful that it could be controlled through medication.

“I think if you take your medication, it can be controlled.” ~ SU03

“I see it as something that will go away because I understand myself and who I am; I know what I want and where I stand.” ~ SU07

“It’s a condition that I think will go away if I stay on treatment.” ~ SU19

“I think it started going away since I have been here because I feel better, it has been 2 weeks now (in hospital), and I feel better.” ~ SU22

Based on these discussions, it becomes apparent that most service users possessed limited knowledge regarding mental illness. About a third of service users knew their clinical diagnosis, with most reporting depression (n = 6), bipolar (n = 4), and schizophrenia (n = 3). About a third of service users (n = 8) reported that they didn’t know their clinical diagnosis, with several service users reporting they had not been told their diagnosis. Further responses from service users suggested that their knowledge enabled self-awareness, and they did not appear to be self-stigmatising.

“And from what I've seen, this [hospital] is not a place for crazy people. I also had that mentality; I never thought that one day I would also be here, but here I am, and I can see it is different." ~ SU 01

“I just think people be more informed about mental illness. If they know how it is, maybe it will change. I don’t know if they will ever understand it… because they don’t even know anything about depression, and when you say you’re schizophrenic you scare them you know.” ~ SU 09

Knowledge of Mental Illness among Caregivers

The majority of caregivers (n = 22) provided responses describing mental illness by its signs and symptoms, e.g., acting strangely, forgetfulness, incoherent and illogical communication.

"The person starts doing things that are not normally what they used to do, things that are just out of the way. From what I saw with my sibling, she would take cups from the kitchen and place them in the wardrobes, beating up a small child, which wasn't something she used to do. Even when she spoke, you couldn't understand what she was trying to say." ~ Caregiver 04

"The person gets out of hand; what they say doesn't make sense; they no longer care about their upkeep, and they take something that belongs in one room to the other; that is how you see that there is a problem there." ~ Caregiver 14

"When the person is not fully functional, I don't know how to put it… by their behaviour or how they act which is not normal…. Some might say things that do not make sense; some are violent; some scream...there are a lot of different things." ~ Caregiver 21

Most caregivers perceived mental illness to persist for life, basing their observations from their personal involvement in caring and their relative’s experiences.

“From what I see, I think it’s something that she will live with.” ~ CG04

“I don’t think it will heal, I used to think that it will in the initial stages but now it looks worse because she is very forgetful. If I don’t remind her to take medication or bath, she doesn’t remember.” ~ CG07

“I don't know, because there was a time when I thought he had completely healed, but he started again.” ~ CG10

“I think it is something that will always be there because he once went to the hospital and he was fine; as time went by, he changed again.” ~ CG17

“I don’t think it will ever go away, but that it can be conditioned through medication.” ~ CG20

Indications from the above discussions suggested that caregivers have some general knowledge about mental illness, its symptoms and treatment outcomes. The gaps in caregivers’ general understanding of the mental illness appeared limited to their personal experiences only.

Perceived Community Misconceptions about Mental Illness

Perceived Community Mental Illness Misconceptions among Service Users

At least 16 service users highlighted those negative beliefs, misconceptions and limited knowledge about mental health were high in their communities, which was understood to fuel stigma.

"People say Witrand is a hospital for crazy people, but when I got here, I saw what kind of hospital it is because it helped me. I didn't see crazy people running around. I just saw normal people with different issues. People like to label others wrongfully." ~ SU 25

Community misconceptions and beliefs about mental illness were associated with perceptions of shameful and indecent behaviours among people with a mental illness, such as undressing in public, violence, and aggression.

"They think that one is mad and that they are most likely to undress in the streets and doing abnormal things that other people don't do... I feel people don't know about mental illness, which is one reason people are misjudged. If media were teaching people, less people would say that Witrand was a hospital for crazy people." ~ SU 16

The belief that if one gets admitted into a mental health institution, one is ultimately “unhinged” was perceived to be prevalent in communities, thereby validating or giving credence to the perpetuation of stigma.

"When people are aware that you get seizures and regularly get taken by an ambulance, and then hear that you went to Witrand, you are crazy." ~ SU 01

Perceived Community Mental Illness Misconceptions among Caregivers

As with responses from service users, caregivers (n = 23) reported that most misconceptions surrounding the behaviour of mentally ill persons stem from a lack of knowledge about mental illness in terms of cause, treatment, and course.

"They don’t understand that the [service user’s] condition is well managed, and it’s not something contagious. I feel like their lack of understanding is what causes them to be negative, if only they understood more about the conditions." ~ Caregiver 18

One persistent perception reported by caregivers was the community’s lowered expectations on achievements from persons living with a mental illness.

"I think that people have less expectations of people with mental illness. I know someone that was fired from his job because he had a mental illness, though when I saw him, he looked normal." ~ Caregiver 01

"They don't think that anything worthwhile can come out of someone with mental illness. Even when you say that you have recovered, they ask themselves if truly you have recovered… or it's just temporary, and you will go back to the state you were in." ~ Caregiver 14

Experiences of Stigma and Discrimination

Experiences of Stigma and Discrimination among Service Users

Experiences of stigma and discrimination from family members and the community were high among service users. Comments provided by service users suggested implicit stigma and significant stigma experiences from family members.

"…people would gossip, like family friends saying things that were not nice. They would go around telling people that I was mad, which is not true; people misunderstand people like myself that have a mental illness.” ~ SU 16

"My family don't want to listen to my options... My mom gets irritated by me and says things like she regrets having a child like me. She says such hurtful things that make me want to kill myself. I tried cutting my veins, hoping I'd bleed to death". ~ SU 08

"I was not treated well. I felt unloved and unwanted. They (family) did more nice things for my younger siblings than for me…. When I tell them what I needed, they didn't take me seriously. My sister didn't want me to go to the church that she goes to." ~ SU 02

A few service users also highlighted stigma and discrimination experiences within health facilities. Some of these negative experiences occurred at primary facilities before referral to the mental health hospital.

"Sometimes, the staff have attitude problems. Like the one will be on the phone the whole day, you know I don't think she's employed to do that." ~ SU 09

"I am not going to be specific say which hospital, something happened to me at night and I wanted to see the doctor, and he refused to see me. That is not how a psychiatrist should operate. ~ SU 18

"Here in the hospital, when the nurses treat us bad, it makes me want to go home and not continue my treatment. The nurses are very rude…. the way they speak to us. Nobody can ever know what it's like for somebody with a mental illness. You can read about it, but you don't know how it really is". ~ SU 05

One service user (SU 03) reported a negative experience with supermarket employees and no longer felt welcome at the supermarket. Several service users and caregivers reported the tendencies of communities to underestimate individuals because of mental illness.

"It seems like they undermine my intelligence. They don't treat me the same way they used to treat me; they start to treat me different. They think that everything I do is because I'm bipolar." ~ SU 05

Experiences of Stigma and Discrimination among Caregivers

Stigma experiences reported by caregivers were lower when compared to the experiences of mental health service users.

"None of the neighbours came out to offer us help. They were just there laughing at her; I think that worsened her condition. They were pointing at each other, and some of her friends have pulled away from her. ~ Caregiver 04

"The neighbours are not supportive; no one approaches us to ask or show support. What I know is that they do not come to help, the women are obviously scared of him." ~ Caregiver 22

Stigma experiences were influenced by whether caregivers or service users had made other people within their families or social settings aware of the condition. For example, service users who reported no stigma experiences were likely to have not disclosed their mental health status.

"Most people were not aware (of his condition), those that knew did not treat him negatively. I even asked him if they were mistreating him or saying things at school, he said no. We would really be lying because there are mentally ill people near our home, and they are not discriminated against". ~ Caregiver 01

Most caregivers reported not having made the community aware of their relative’s mental health status, with sentiments of fear of stigma and limited understanding cited as the primary reasons. Disclosure of mental illness by caregivers was mainly to a small circle of close, trusted family or friends who could empathise with the situation and possibly offer some support.

"It will be the first time experiencing stigma. I didn't disclose his situation to the community because they won't take it well, and he won't feel free. So, I only told people close to me because I want him to feel free in the community, for them to treat him normal so that he doesn't feel rejected." ~ Caregiver 11

Stigma and discrimination experiences appeared more consistent among caregivers who reported that the community was aware of their relative’s mental health status (n = 11). One caregiver highlighted how the service user was disrespected by referring to the service user as “that child of yours”. Some caregivers in communities aware of their relative’s mental health status and no stigma experiences highlighted they were not sure what was being said about them behind their backs.

"When she started showing symptoms, they thought she is bewitched, or she is a witch. It made the community isolate her, and they wanted her and us as a family to leave the community just because of her mental illness". ~ Caregiver 06

"They have turned him into an outcast. Normally at my grandmother's house, we love watching TV, but when he is around, they remove the TV and hide it, saying she is scared of him and should leave the house. My uncles don't like him at all. He talks about being referred to as 'crazy' or 'Witrand' in the house. One of our cousins I stay with is the one who usually uses that name." ~ Caregiver 17

Mental Health Stigma Coping Strategies

Coping Strategies among Service Users

Some service users reported negative coping mechanisms and strategies such as alcohol, drug use (n = 3), and self-isolation. A few service users reported using a combination of positive coping mechanisms such as prayer, physical activity (household chores, exercising, playing sports), talking and reaching out to supportive family or friends, writing, and sleeping. While these are common coping strategies, responses suggested that service users disclose their mental health status to only a few close relatives, and disclosure to friends is limited.

Service user acceptance of mental health status and learning to live with the condition was critical in ensuring that community stigma and discrimination do not affect them. Service user 16 explained this as, “I have accepted that I have bipolar, so I no longer take everything to heart”.

Communities were reported to use derogatory terms such as “rank” and “Witrand” (the name of the psychiatric institution) on service users. Service users who experienced such public verbal insults coped by ignoring these terms and reaffirming that they are not “insane”. A few service users who experienced public name-calling responded with hostility.

“Some of my friends refer to me as Witrand, and I don’t like that. I know that once I get discharged, some will call me ‘Witrand’…. I avoid them because I know I am not a ‘rank’ (mental health patient)”. ~ SU 15

“They call me ‘psych’ and are the ones that make me isolate myself from the community because of the harsh words that they say to me. I know that if I respond to such statements, it’s going to be a bigger issue, so I choose to isolate myself.” ~ SU 19

Coping Strategies among Caregivers

The primary coping strategy used by caregivers was highlighted during discussions on stigma experiences. The majority of caregivers reported non-disclosure of their relative’s mental health status, and in most cases, confiding it to a few close friends and family. Direct responses to coping strategy questions resulted in caregivers reporting other strategies to cope with mental illness burden rather than stigma, e.g., prayers, reaching out to supportive family or friends, and sleeping.

Compared to service users (n = 3), fewer caregivers (n = 1) used poor coping strategies such as alcohol and drug use. Other caregivers highlighted the difficulty in coping with mental illness.

"I am not coping. If I had someone by my side, I would cope, but because I am alone, I am not. I have been diagnosed with depression, and I take fluoxetine. We lack moral support; we don't have support from home, honestly. So, if we can get more support, people being there for us, maybe it will be better." ~ Caregiver 18

Impact of Stigma on Family Support and Caregiving

All service users enrolled in the study had a family caregiver, except for one service user who reported that they live alone and could fully manage all aspects of their condition, including taking care of themself. Caregivers felt that providing care in most instances was too much responsibility. Feelings of being overwhelmed were worse in caregivers whose families discriminated against the service user, and in some instances, the caregiver. This burden of care translated into losses such as income loss and increased health expenditure for family caregivers. Despite the challenges, caregivers highlighted that giving up was not an option due to their close relationship with the service user, e.g., siblings or parents.

"I don't know if I can say I'm tired of him. Right now, I haven't lost hope. I have that fighting spirit. I want to know what went wrong. I lost his brother and his father; I can't lose this one. So, I haven't gotten to a point where I'm tired. I want the best for him." ~ Caregiver 11

" It does happen (feeling overwhelmed) because I have my own life. He is 22 years old, but I am more focused on his life. It gets difficult because I now have to live both our lives." ~ Caregiver 10

"I feel like the whole responsibility falls on me, my uncles no longer treat him well, and that hurts me a lot. One of my uncles (mom's brother) is no longer on speaking terms with my mom... I don't feel like I am living like other people, but I live amongst problems." ~ Caregiver 17

Caregiver Support Needs

Caregivers’ Perceptions and Need for Support Groups

Caregivers strongly felt that support groups would be instrumental in helping them learn more about mental illness, how to support their loved ones, and cope with the responsibilities related to caregiving.

"A support group because I might take advice from some of the things that they are sharing. What I need most is advice on how to help her when she is having an episode, and social workers can provide counselling." ~ Caregiver 04

"I would want to meet with others so that I can also hear their perspective on what is happening…. It's better if we all meet, there is a centre near Grace Mokhomo, Folang Disability Centre, which is in the centre so anyone can easily get there." ~ Caregiver 06

The major factor in caregiver acceptance of support groups was the opportunity to share experiences and inspire each other to continue providing the best possible care for their loved one living with a mental illness. An approach to the sessions that blends support from health professionals and other caregivers may be the most appropriate.

"It will be better if it is led by someone that has gone through it. I think we should also be included though we have not gone through the same situation… Social workers can guide people on how to start; then, a psychologist can be added to talk about how to deal with this thing. Different people will then share what happened to them." ~ Caregiver 08

Only one caregiver felt that neither option was relevant, based on the observation that her loved one managed most tasks independently. They described her condition as “not that bad” to warrant intervention or extended support.

Caregivers’ Recommendations for Services and/Support

Most caregivers were not aware of the community mental health services offered by the government apart from visiting the nearest health facilities (clinics). One caregiver reported that while they were not aware of other government services, they received messages from a private facility to join support groups. Another participant (Caregiver 06) put it as “I tried searching for them on the internet, and I couldn’t find anything. I find private sectors that need to be paid.”

A key theme from caregivers reflected the need for increasing awareness of mental health stigma, which could dispel myths and misconceptions of mental illnesses.

"I think the same things they did with HIV; mental illness is a condition that is still hidden. I think campaigns and also prominent people need to start coming out; like with HIV, there is a judge that came out. Because of his position, it gave people the courage to say if a man of this stature can come out and lead a productive life, it spread over to other people that they can live a normal and productive life." ~ Caregiver 16

Other suggestions included community activities such as increased youth-focused activities in youth centres, volunteers for mental health activities and donations to support families of people living with a mental health condition.

"I think support system, for example sending someone like we are chatting now. To send people from the clinic to check how we are doing, it's comforting talking to someone that understands your situation and doesn't judge." ~ Caregiver 14

"Support groups, informative meetings, you know, to talk about this and how we can prevent this, how can we fight this and have discussions between the parents and the children. Sometimes they are in their own world, and as parents, we are in our world.

Caregivers also reported financial constraints. Taking care of the service users took them away from other income-generating activities, making their households more vulnerable to poverty and food insecurity.

"I need help with basic needs, mostly finances and food. Those are the things that are most needed in the house. For example, when he goes to the hospital, he can make himself food and so forth. the government can help us with work and so forth." ~ Caregiver 05

Discussion

From this study, most service users displayed limited general knowledge about mental health and living with mental illness – with a third having knowledge of their diagnosis. Literature suggests that knowledge limitations may contribute towards negative perceptions and stigma (Evans-Lacko et al., 2010). Similar findings of inadequate knowledge about mental illness among caregivers and service users have been noted in previous studies conducted in sub-Saharan Africa (Girma et al., 2014; Tawiah et al., 2015). Knowledge on aspects of mental health such as treatment efficacy, recognition, help-seeking, and employment has a positive impact on stigma reduction (Evans-Lacko et al., 2010). Improving mental health literacy for both carers and service users could yield improved coping mechanisms.

Both service users and caregivers reported that their social relationships within families and in the community had suffered. The findings are consistent with the literature (Ailbhe Benson et al., 2016; Dako-Gyeke & Asumang, 2013; Vicente et al., 2013; Zhou et al., 2018). Financially, caregivers also highlighted that mental illness in the family posed a tremendous household strain, amplified in low-income and low-educational families. The World Health Federation of Mental Health (WFMH) (, 2010) noted that most carers experienced psychological, financial, physical, and social challenges when caring for someone with a severe mental illness. In low-income countries, the burden of care is further exacerbated by the scarcity of health care resources and the prevalence of psychiatric stigma (Addo et al., 2018; Mascayano et al., 2015).

Experiences of stigma by association or self-stigma were noted but varied among caregivers. The majority reported little or no stigma experiences since they deliberately concealed the mental conditions of their relatives from the community, only sharing with close family ties. Caregivers said they kept the diagnosis secret out of fear of being stigmatised and attempting to protect their loved ones from stigma within communities. Fear of stigma among caregivers can be explained by other studies that linked caregiver feelings of being stigmatised to the relationship with the mentally ill relative (Struening et al., 2001; L. H. Yang et al., 2013). Caregivers reluctance to disclose the service users’ illness in the community followed a similar trend reported in previous studies that observed the same pattern of behaviour from carers of service users (A. Benson et al., 2015; Dockery et al., 2015; Koschorke et al., 2017). Girma et al. (2014) found an association between self-stigma and perceived signs of mental illness and identified that caregivers were reluctant to be associated with mental health service users. Unfortunately, this trend poses a risk to service users dependent on their caregivers for seeking treatment as caregiver reluctance can negatively affect help-seeking behaviours. They may not support treatment follow-up as a way of avoiding stigmatisation.

More service users reported stigma-related discriminatory experiences compared to their caregivers. Girma et al. (2014) posited that self-stigma might interfere with service users’ treatment-seeking, adherence, and rehabilitation courses and outcomes. While caregivers were reluctant to share with the community that their relative had been diagnosed with a mental illness, most service users indicated that negative sentiments from family members and the community would not deter them from seeking help for their condition. The need for support for caregivers to support continued help-seeking for their relatives was highlighted in this study.

Fear of stigma among service users and affiliate stigma among caregivers remains an important issue that needs to be addressed in the recovery journey of service users with mental illness following their discharge from hospital in South Africa. Data shows that caregivers mostly keep silent about their ward’s mental health status, thus preventing stigma for both of them. The behaviour suggests a high prevalence of implicit psychiatric stigma attitudes in families and communities. Implicit stigma attitudes are internal beliefs held by an individual and are deemed outside of one’s conscious control or awareness (Sandhu et al., 2018). Even without being consciously aware of them, implicit biases can influence thoughts, feelings, and behaviours (Park et al., 2008). Several other studies have reported high implicit stigma among family members of mental health service users (González-Sanguino et al., 2019; Singh et al., 2016; Tawiah et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2018). Given the continued prevalence of mental health stigma, especially in African communities, it is understandable how non-disclosure is an appealing stigma prevention strategy (Abdullah & Brown, 2011; Dako-Gyeke & Asumang, 2013; MacGregor, 2018; Mavundla et al., 2009; L. H. Yang et al., 2013).

On potential coping interventions, both caregivers and service users indicated that support groups might be helpful. Previous research has shown that intervention approaches that strengthen the relationship between caregiver and their wards reduce caregiver burden and strengthen coping capabilities (C. T. Yang et al., 2014). The use of multi-component approaches (e.g. face to face training, telephone and digital platforms) are necessary not only for improved efficacy as suggested in the literature (Balaji et al., 2012; Fiorillo et al., 2011; Ngoc et al., 2016; Perlick et al., 2011; Shamsaei et al., 2018), but should be aligned with the current global regulations regarding the outbreak of the coronavirus (COVID-19) to mitigate the risk of transmission to both mental health service users and caregivers. Further, multi-component approaches would ensure that financially vulnerable families are accommodated to choose a convenient support method.

However, this study provides compelling evidence that mental health stigma reduction interventions in Africa should not only focus on caregivers, services users, and immediate families. Responses from both caregivers and service users provide evidence of strong mental health stigma in communities. Social rejection is a constant stressor that negatively impacts self-esteem for former institutionalised service users (N. J. Herman, 1993; Wright et al., 2000). For mental illness, there are social markers of transcendence from the “normal” to the “deviant” and yet there are no rites of passage to demonstrate, celebrate, and reintegrate the “redeemed deviants” (N. J. Herman, 1993). The continued lack of social support structures that help integrate discharged mental health service users into society threatens social re-integration and participation. Mass media platforms, including social media, have increased awareness and reduced mental health stigma in African communities (Potts & Henderson, 2021). This approach may be considered in improving the lives of many mental health service users, significantly contributing towards their social re-integration upon release from mental health institutions.

Strengths and Limitations

Generalizability of data is relatively limited due to the relatively small sample size, comprised of a specific ethnic group, generally low socio-economic status and being drawn from one referral facility servicing various surrounding communities. A selection bias may also have been introduced by only using participants who could coherently answer questions - potentially resulting in inhomogeneity of experiences as caregivers of service users who were unstable were excluded.

The clinical training of the researcher and the assistant interviewer was used to ensure that high-quality data on experiences of caregivers and service users were collected, with necessary probing to gain in-depth perspectives. Interviewers were of the same ethnic and cultural backgrounds as study participants to optimise cultural perspectives and influences not being missed from interviews for interpretation and contextualisation of findings.

Conclusion

The study has shown that both service users and their family caregivers suffer wide-ranging adverse outcomes psychologically, socially, and economically. In the context of the drive towards deinstitutionalisation in South Africa and the reliance on informal community mental health services that includes family members, low mental health literacy, and mental health stigma inhibits the social re-integration of mental health service users into communities. In addition to developing community psychosocial support programmes for service users and caregivers alike, the need to match these efforts with population and community-level interventions to combat stigmatising beliefs in the general public to counter social rejection and promote re-integration and participation in society of mental health service-users has been foregrounded by this study.

Funding

The authors did not receive support from any organisation for the submitted work.

Data Availability

The data are not publicly available due to the information’s sensitivity and to protect study participants’ confidentiality. The datasets are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author [PM].

Declarations

Consent to Participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Portia Monnapula-Mazabane, Email: pmazabane@icloud.com.

Inge Petersen, Email: peterseni@ukzn.ac.za.

References

- Abdullah, T., & Brown, T. L. (2011). Mental illness stigma and ethnocultural beliefs, values, and norms: An integrative review. In clinical psychology review (Vol. 31, issue 6, pp. 934–948). 10.1016/j.cpr.2011.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Addo R, Agyemang SA, Tozan Y, Nonvignon J. Economic burden of caregiving for persons with severe mental illness in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review. PLoS One. 2018;13(8):e0199830. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0199830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angermeyer MC, van der Auwera S, Carta MG, Schomerus G. Public attitudes towards psychiatry and psychiatric treatment at the beginning of the 21st century: A systematic review and meta-analysis of population surveys. World Psychiatry. 2017;16(1):50–61. doi: 10.1002/wps.20383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assefa, D., Shibre, T., Asher, L., & Fekadu, A. (2012). Internalized stigma among patients with schizophrenia in Ethiopia: A cross-sectional facility-based study. BMC Psychiatry, 12(1), 239. 10.1186/1471-244X-12-239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Balaji, M., Chatterjee, S., Koschorke, M., Rangaswamy, T., Chavan, A., Dabholkar, H., Dakshin, L., Kumar, P., John, S., Thornicroft, G., & Patel, V. (2012). The development of a lay health worker delivered collaborative community based intervention for people with schizophrenia in India. BMC Health Services Research, 12(1). 10.1186/1472-6963-12-4222340662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Benson, A., O’Toole, S., Lambert, V., Gallagher, P., Shahwan, A., & Austin, J. K. (2015). To tell or not to tell: A systematic review of the disclosure practices of children living with epilepsy and their parents. In epilepsy and behavior (Vol. 51, pp. 73–95). Academic press Inc. 10.1016/j.yebeh.2015.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Benson A, O’Toole S, Lambert V, Gallagher P, Shahwan A, Austin JK. The stigma experiences and perceptions of families living with epilepsy: Implications for epilepsy-related communication within and external to the family unit. Patient Education and Counseling. 2016;99(9):1473–1481. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2016.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan P. How stigma interferes with mental health care. American Psychologist. 2004;59(7):614–625. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.7.614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan, P. W., Watson, A. C., & Miller, F. E. (2006). Blame, shame, and contamination: the impact of mental illness and drug dependence stigma on family members. Journal of Family Psychology, 20(2), 239. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Dako-Gyeke, M., & Asumang, E. S. (2013). Stigmatization and discrimination experiences of persons with mental illness: Insights from a qualitative study in southern Ghana. In Social Work & Society (Vol. 11, issue 1). http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:hbz:464-sws-421

- Dockery L, Jeffery D, Schauman O, Williams P, Farrelly S, Bonnington O, Gabbidon J, Lassman F, Szmukler G, Thornicroft G, Clement S. Stigma- and non-stigma-related treatment barriers to mental healthcare reported by service users and caregivers. Psychiatry Research. 2015;228(3):612–619. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2015.05.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egbe CO, Brooke-Sumner C, Kathree T, Selohilwe O, Thornicroft G, Petersen I. Psychiatric stigma and discrimination in South Africa: Perspectives from key stakeholders. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14(1):191. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-14-191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans-Lacko S, Little K, Meltzer H, Rose D, Rhydderch D, Henderson C, Thornicroft G. Development and psychometric properties of the mental health knowledge schedule. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2010;55(7):440–448. doi: 10.1177/070674371005500707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiorillo A, Bassi M, De Girolamo G, Catapano F, Romeo F. The impact of a psychoeducational intervention on family members’ views about schizophrenia: Results from the OASIS Italian multi-Centre study. International Journal of Social Psychiatry. 2011;57(6):596–603. doi: 10.1177/0020764010376607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forero R, Nahidi S, De Costa J, Mohsin M, Fitzgerald G, Gibson N, McCarthy S, Aboagye-Sarfo P. Application of four-dimension criteria to assess rigour of qualitative research in emergency medicine. BMC Health Services Research. 2018;18(1):120. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-2915-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost DM. Social stigma and its consequences for the socially stigmatized. Social and Personality Psychology Compass. 2011;5(11):824–839. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2011.00394.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, Rashid S, Redwood S. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2013;13(1):117. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-13-117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girma E, Möller-Leimkühler AM, Müller N, Dehning S, Froeschl G, Tesfaye M. Public stigma against family members of people with mental illness: Findings from the Gilgel gibe field research center (GGFRC), Southwest Ethiopia. BMC International Health and Human Rights. 2014;14(1):2. doi: 10.1186/1472-698X-14-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Sanguino C, Muñoz M, Castellanos MA, Pérez-Santos E, Orihuela-Villameriel T. Study of the relationship between implicit and explicit stigmas associated with mental illness. Psychiatry Research. 2019;272:663–668. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.12.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouda HN, Charlson F, Sorsdahl K, Ahmadzada S, Ferrari AJ, Erskine H, Leung J, Santamauro D, Lund C, Aminde LN, Mayosi BM, Kengne AP, Harris M, Achoki T, Wiysonge CS, Stein DJ, Whiteford H. Burden of non-communicable diseases in sub-Saharan Africa, 1990–2017: results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. The Lancet Global Health. 2019;7(10):e1375–e1387. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30374-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman AA, Stein DJ, Seedat S, Heeringa SG, Moomal H, Williams DR. The south African stress and health (SASH) study: 12-month and lifetime prevalence of common mental disorders. South African Medical Journal. 2009;99(5):339–344. doi: 10.7196/SAMJ.3374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman NJ. Return to sender: Reintegrative stigma-management strategies of ex-psychiatric patients. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography. 1993;22(3):295–330. doi: 10.1177/089124193022003002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. (2018). Global burden of disease study 2017. Institute of Health Metrics. http://www.healthdata.org/sites/default/files/files/policy_report/2019/GBD_2017_Booklet.pdf

- Kemp, C. G., Jarrett, B. A., Kwon, C. S., Song, L., Jetté, N., Sapag, J. C., Bass, J., Murray, L., Rao, D., & Baral, S. (2019). Implementation science and stigma reduction interventions in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review. In BMC medicine (Vol. 17, issue 1, pp. 1–18). BioMed central ltd. 10.1186/s12916-018-1237-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Koschorke M, Padmavati R, Kumar S, Cohen A, Weiss HA, Chatterjee S, Pereira J, Naik S, John S, Dabholkar H, Balaji M, Chavan A, Varghese M, Thara R, Patel V, Thornicroft G. Experiences of stigma and discrimination faced by family caregivers of people with schizophrenia in India. Social Science & Medicine. 2017;178:66–77. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.01.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund C, Petersen I, Kleintjes S, Bhana A. Mental health services in South Africa: Taking stock. African Journal of Psychiatry (South Africa) 2012;15(6):402–405. doi: 10.4314/ajpsy.v15i6.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacGregor H. Mental health and the maintenance of kinship in South Africa. Medical Anthropology: Cross Cultural Studies in Health and Illness. 2018;37(7):597–610. doi: 10.1080/01459740.2018.1508211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mak, W. W. S., & Cheung, R. Y. M. (2012). Psychological distress and subjective burden of caregivers of people with mental Illness: The role of affiliate stigma and face concern. Community Mental Health Journal, 48(3), 270–274. 10.1007/s10597-011-9422-9 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Mascayano, F., Armijo, J. E., & Yang, L. H. (2015). Addressing stigma relating to mental illness in low- and middle-income countries. Frontiers in psychiatry, 6(MAR). 10.3389/fpsyt.2015.00038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Mavundla TR, Toth F, Mphelane ML. Caregiver experience in mental illness: A perspective from a rural community in South Africa. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing. 2009;18(5):357–367. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0349.2009.00624.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monnapula-Mazabane P, Babatunde GB, Petersen I. Current strategies in the reduction of stigma among caregivers of patients with mental illness: A scoping review. South Africa Journal of Psychology. 2021;008124632110015:008124632110015. doi: 10.1177/00812463211001530. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan AJ, Reavley NJ, Ross A, Too LS, Jorm AF. Interventions to reduce stigma towards people with severe mental illness: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2018;103:120–133. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2018.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngoc TN, Weiss B, Trung LT. Effects of the family schizophrenia psychoeducation program for individuals with recent onset schizophrenia in Viet Nam. Asian Journal of Psychiatry. 2016;22:162–166. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2016.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nxumalo CT, Mchunu GG. Exploring the stigma related experiences of family members of persons with mental illness in a selected community in the iLembe district, KwaZulu-Natal. Health SA Gesondheid. 2017;22:202–212. doi: 10.1016/j.hsag.2017.02.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Park SH, Glaser J, Knowles ED. Implicit motivation to control prejudice moderates the effect of cognitive depletion on unintended discrimination. Social Cognition. 2008;26(4):401–419. doi: 10.1521/soco.2008.26.4.401. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Patel, V., Saxena, S., Lund, C., Thornicroft, G., Baingana, F., Bolton, P., Chisholm, D., Collins, P. Y., Cooper, J. L., Eaton, J., Herrman, H., Herzallah, M. M., Huang, Y., Jordans, M. J. D., Kleinman, A., Medina-Mora, M. E., Morgan, E., Niaz, U., Omigbodun, O., … UnÜtzer, Jü. (2018). The lancet commission on global mental health and sustainable development. In the lancet (Vol. 392, issue 10157, pp. 1553–1598). Lancet Publishing Group. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31612-X. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Perlick DA, Nelson AH, Mattias K, Selzer J, Kalvin C, Wilber CH, Huntington B, Holman CS, Corrigan PW. In our own voice-family companion: Reducing self-stigma of family members of persons with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services. 2011;62(12):1456–1462. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.001222011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen I, Lund C. Mental health service delivery in South Africa from 2000 to 2010: One step forward, one step back. South African Medical Journal. 2011;101(10):751–757. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potts LC, Henderson C. Evaluation of anti-stigma social marketing campaigns in Ghana and Kenya: Time to change global. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):1–14. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-10966-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reupert A. A socio-ecological framework for mental health and wellbeing. Advances in Mental Health. 2017;15(2):105–107. doi: 10.1080/18387357.2017.1342902. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie J, Spencer L. Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research. In: Huberman M, Miles MB, editors. The qualitative Researcher’s companion (pp. 305–329) Sage Publications; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Sandhu HS, Arora A, Brasch J, Streiner DL. Mental health stigma: Explicit and implicit attitudes of Canadian undergraduate students, medical school students, and psychiatrists. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2018;64(3):209–217. doi: 10.1177/0706743718792193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shamsaei F, Nazari F, Sadeghian E. The effect of training interventions of stigma associated with mental illness on family caregivers: A quasi-experimental study. Annals of General Psychiatry. 2018;17(1):1–5. doi: 10.1186/s12991-018-0218-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh A, Mattoo SK, Grover S. Stigma and its correlates among caregivers of schizophrenia: A study from North India. Psychiatry Research. 2016;241:302–308. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.04.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Struening EL, Perlick DA, Link BG, Hellman F, Herman D, Sirey JA. Stigma as a barrier to recovery: The extent to which caregivers believe most people devalue consumers and their families. Psychiatric Services. 2001;52(12):1633–1638. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.12.1633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tawiah PE, Adongo PB, Aikins M. Mental health-related stigma and discrimination in Ghana: Experience of patients and their caregivers. Ghana Medical Journal. 2015;49(1):30–36. doi: 10.4314/gmj.v49i1.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornicroft, G. (2006). Shunned: Discrimination against people with mental illness (Vol. 301). Oxford university press Oxford.

- Vicente JB, Mariano PP, Buriola AA, Paiano M, Waidman MAP, Marcon SS. Aceitação da pessoa com transtorno mental na perspectiva dos familiares. Revista Gaúcha de Enfermagem. 2013;34(2):54–61. doi: 10.1590/s1983-14472013000200007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Herman A, Stein DJ, Heeringa SG, Jackson PB, Moomal H, Kessler RC. Twelve-month mental disorders in South Africa: Prevalence, service use and demographic correlates in the population-based south African stress and health study. Psychological Medicine. 2008;38(2):211–220. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707001420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Federation of Mental Health (WFMH). (2010). Caring for the caregiver: Why your mental health matters when you are caring for others. WFMH Woodbridge, VA.

- World Health Organization. (2019). The WHO Special Initiative for Mental Health (2019–2023): Universal Health Coverage for Mental Health. http://www.who.int/iris/handle/10665/89966

- Wright ER, Gronfein WP, Owens TJ. Deinstitutionalization, social rejection, and the self-esteem of former mental patients. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2000;41(1):68–90. doi: 10.2307/2676361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang CT, Liu HY, Shyu YIL. Dyadic relational resources and role strain in family caregivers of persons living with dementia at home: A cross-sectional survey. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2014;51(4):593–602. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2013.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang LH, Purdie-Vaughns V, Kotabe H, Link BG, Saw A, Wong G, Phelan JC. Culture, threat, and mental illness stigma: Identifying culture-specific threat among Chinese-American groups. Social Science and Medicine. 2013;88:56–67. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.03.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Subramaniam M, Lee SP, Abdin E, Sagayadevan V, Jeyagurunathan A, Chang S, Shafie SB, Fauziana R, Rahman BA, Vaingankar JA, Chong SA. Affiliate stigma and its association with quality of life among caregivers of relatives with mental illness in Singapore. Psychiatry Research. 2018;265:55–61. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.04.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou T, Wang Y, Yi C. Affiliate stigma and depression in caregivers of children with autism Spectrum disorders in China: Effects of self-esteem, shame and family functioning. Psychiatry Research. 2018;264:260–265. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.03.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data are not publicly available due to the information’s sensitivity and to protect study participants’ confidentiality. The datasets are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author [PM].