Abstract

The D-type cyclins and their major kinase partners CDK4 and CDK6 regulate G0-G1-S progression by contributing to the phosphorylation and inactivation of the retinoblastoma gene product, pRB. Assembly of active cyclin D-CDK complexes in response to mitogenic signals is negatively regulated by INK4 family members. Here we show that although all four INK4 proteins associate with CDK4 and CDK6 in vitro, only p16INK4a can form stable, binary complexes with both CDK4 and CDK6 in proliferating cells. The other INK4 family members form stable complexes with CDK6 but associate only transiently with CDK4. Conversely, CDK4 stably associates with both p21CIP1 and p27KIP1 in cyclin-containing complexes, suggesting that CDK4 is in equilibrium between INK4 and p21CIP1- or p27KIP1-bound states. In agreement with this hypothesis, overexpression of p21CIP1 in 293 cells, where CDK4 is bound to p16INK4a, stimulates the formation of ternary cyclin D-CDK4-p21CIP1 complexes. These data suggest that members of the p21 family of proteins promote the association of D-type cyclins with CDKs by counteracting the effects of INK4 molecules.

Progress through the G1 phase of the mammalian cell cycle is regulated by the ordered synthesis, assembly, and activation of distinct cyclin-CDK holoenzymes (45, 46). Cyclins D1, D2, and D3 are up-regulated as cells exit from quiescence and associate with their major kinase partners CDK4 and CDK6 (3, 29, 32, 53). These two kinase molecules are highly homologous and associate exclusively with the D-type cyclins (3). Numerous studies have implicated cyclin D-CDK4-CDK6 complexes as key regulators of the cell cycle up to a hypothetical point during late G1 (24, 25), the restriction point, when hyperphosphorylation and inactivation of the retinoblastoma tumor suppressor gene product, pRB, occur (37, 44).

In contrast to mitotic cyclin-CDK complexes, the D-type cyclins do not automatically assemble into complexes with either CDK4 or CDK6. For example, when overexpressed in NIH 3T3 cells in the absence of serum, D-type cyclins and CDK4 do not interact efficiently (30). Hence, assembly of D-type cyclins and CDK4 and CDK6 into functional complexes in vivo is likely to depend on numerous factors, in particular, synthesis rates and stability of the various components. Indeed, the D-type cyclins possess canonical PEST sequences near their C termini and have short half-lives in vivo (4, 31).

Association of the D-type cyclins with CDK4 and CDK6 is also influenced by the INK4 family of CDK inhibitors (p15INK4b, p16INK4a, p18INK4c, and p19INK4d) (9, 10, 12, 18, 42). INK4 polypeptides bind to the catalytic subunits and inhibit the association of D-type cyclins (10, 38). Typically, human cell lines that lack functional pRB express very high levels of p16INK4a (1, 35, 38). In such cells, CDK4 and CDK6 do not interact with D-type cyclins but are sequestered into long-half-life, binary complexes with p16INK4a (38). These observations have led to a simple model whereby INK4 family members compete with the D-type cyclins for binding to their target CDKs, and uncomplexed D-type cyclins are rapidly degraded.

Members of a second family of CDK-regulatory molecules (p21CIP1, p27KIP1, and p57KIP2) (8, 15, 22, 28, 40, 48) comprise a class of polypeptides thought to be broad-spectrum inhibitors of different cyclin-CDK complexes. The prototypic member is p21CIP1, a molecule independently identified by several laboratories. Variously described as a p53-regulated cell cycle inhibitor and a marker induced during cellular senesence (7, 34), p21CIP1 was also cloned biochemically by virtue of copurification with cyclin D1 from mammalian cell extracts (52). In vitro, p21 family members bind to and inhibit the kinase activities of many mammalian cyclin-CDK complexes (16). Recently, evidence has emerged that in addition to simply inhibiting kinase activity, members of the p21 family of molecules may have additional roles. For instance, in overexpression studies, p21CIP1 seemed to play a role during assembly of cyclin D-CDK complexes (20).

Aberrant accumulation of active cyclin D-CDK complexes and the inappropriate phosphorylation of pRB are common events in a variety of human tumors (11). Cyclin D1 becomes amplified or overexpressed in many different tumor types (5, 21). Similarly, CDK4 is subject to amplification (17, 26, 41), as well as to point mutations that render it insensitive to INK4 inhibition (50). However, of all the CDK inhibitors, only p16INK4a has been shown convincingly to be a tumor suppressor (19, 39). Consistent with this, p16INK4a levels rise dramatically during cellular senescence (2, 13, 36). In this work, we address the mechanism of cyclin D-CDK assembly by examining specific biochemical properties of individual CDK inhibitors and their associated target molecules. The data suggest that the INK4 and p21 families of CDK-regulatory polypeptides play antagonistic roles during the formation of cyclin D-CDK4-CDK6 holoenzymes. Moreover, we find that the p16INK4a tumor suppressor gene product is unique among the INK4 group, as it alone forms stable complexes with both CDK4 and CDK6 under proliferative conditions, suggesting that this molecule is a specialized member of the INK4 family.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture.

CEM and ML1 cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS); EL4, WI38, 293, and MCF7 cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) with 10% FCS. For adenovirus infections, 293 cells were split from the stock culture and grown to ∼80% confluence. Adenovirus supernatants, both AdVec control and recombinant Adp21CIP1 (49), were applied at multiplicities of infection of ∼2. Twenty-four hours postinfection, cells were harvested prior to lysis.

Antibodies.

Peptides corresponding to the C-terminal regions of the following polypeptides were synthesized (Research Genetics), coupled to keyhole limpet hemocyanin (Pierce), and injected into rabbits (Pocono Rabbit Farms): murine-human cyclin D1 (CLACTPTDVRDVDI), murine-human cyclin D2 (CDPDQATTPTDVRDVDL), murine-human cyclin D3 (CGPSQTSTPTDVTAIHL), murine-human CDK4 (CALQHSYLHKEESDAE), murine-human CDK6 (CSQNTSELNTA), murine p15INK4b (CGHRDIARYLHAATGD), human p15INK4b (CGHRDVAGYLRTATGD), human p16INK4a (CARIDAAEG PSDIPD), murine p18INK4c (CSLMEANGVGGATSLQ), human p18INK4c (CSLMQANGAGGATNLQ), murine p19INK4d (CQNLMDILQGHMMIPM), human p19INK4d (CQDLVDILQGHMVAPL), and human p21CIP1 (CTDFYHSKRRLIFSKRKP). All peptide antisera were affinity purified against the cognate immunogen (Sulfolink; Pierce). Antibodies to glutathione-S-transferase (GST) fusion proteins of murine p21CIP1 and human p27KIP1 were also raised. These were partially purified on protein A columns (Pierce) and subsequently depleted of GST-reactive immunoglobulins by passage over agarose-immobilized GST. Following purification, all sera were either dialyzed against phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)–1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) plus 20% glycerol or covalently coupled to protein A-Sepharose beads for use in immunoprecipitation analyses (14). Dialyzed sera were stored at −20°C, and antibody-bead slurries were maintained at 4°C. Antibody specificity was confirmed with specific in vitro-translated products and by immunoprecipitation, V8 proteolytic analysis, and Western blotting.

Gel filtration chromatography.

Gel filtration chromatography was carried out by using a Superdex 200 HR 10/30 column with a fast-performance liquid chromatography system (Pharmacia). Samples (500 μl) containing 5 to 10 mg of whole-cell extract were loaded onto the column and separated in gel filtration buffer (50 mM HEPES [pH 7.5], 10 mM MgCl2, 150 mM NaCl) at a flow rate of 0.3 ml/min for the first 5 ml, 0.4 ml/min for the next 10 ml, and then 0.5 ml/min for the final 10 ml. The molecular mass standards (Sigma) used to calibrate the column were blue dextran (2,000 kDa), thyroglobulin (669 kDa), apoferritin (443 kDa), β-amylase (200 kDa), alcohol dehydrogenase (150 kDa), bovine serum albumin (66 kDa), carbonic anhydrase (29 kDa) and cytochrome c (12.4 kDa). The void volume of different columns was between 8 and 8.5 ml, and this volume was the point at which fraction collection commenced. For each fractionation, 24 0.5-ml fractions were collected. Typically, fractions 2 to 19 were used in later experiments.

Immunoprecipitation and Western blotting analyses.

Cells were washed once in PBS and lysed in Nonidet P-40 (NP-40) lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES [pH 7.5], 1% NP-40, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, aprotinin [5 μg/ml], leupeptin [5 μg/ml], pepstatin [5 μg/ml], Pefabloc [5 μg/ml]) at 4°C for 30 min. Lysates were then clarified by centrifugation at 15,000 × g for 15 min. For kinase assays, lysates were prepared by the addition of Tween 20 lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES [pH 7.5], 10 mM MgCl2, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% Tween 20, 1 mM DTT, 25 μM ATP, aprotinin [5 μg/ml], leupeptin [5 μg/ml], pepstatin [5 μg/ml], Pefabloc [5 μg/ml]), followed by passage through a 19-gauge hypodermic needle and two rounds of freeze-thawing on dry ice. Immunoprecipitations were performed with 50 μl of bead-immobilized antibodies (20% slurries). Peptide blocks were performed by preincubating 5 μg of cognate peptide with antibody beads at 30°C for 30 min prior to the addition of lysate. Typically 500 to 1,000 μg of whole-cell extract was used in standard immunoprecipitations. Immune complexes were collected by rocking for 2 h at 4°C, followed by extensive washing with ice-cold lysis buffer. For Western blotting analysis, samples were subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred to Immobilon P membrane (Millipore). Membranes were probed with primary antibodies diluted in PBS–0.2% Tween 20–5% milk powder, either singly or in combination. Complexes were detected with horseradish peroxidase-linked secondary serum (Amersham) and enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL; Amersham).

Immunodepletions.

Whole-cell extracts were prepared with NP-40 lysis buffer and subjected to five rounds of immunodepletion, using either normal rabbit immunoglobulin or a combination of anti-p21CIP1 (αp21CIP1) and αp27KIP1 antibodies immobilized on beads. Following depletion, supernatants were immunoprecipitated with specific antisera as required.

In vitro binding assays.

In vitro translation products were generated by using a coupled transcription-translation system (TNT; Promega) according to manufacturer’s protocols. Equal amounts (typically 5 μl) of two freshly generated in vitro-translated products were mixed and incubated at 30°C for 30 min. The mixture was then diluted with 1 ml of lysis buffer containing 1% NP-40, 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 500 mM NaCl, 3% bovine serum albumin, and protease inhibitors, followed by centrifugation at 16,000 × g for 10 min to remove any denatured material. A 950-μl aliquot of the supernatant was transferred to a fresh tube containing INK4-specific antibody-bead slurry. The sample was then processed in the same way as a normal immunoprecipitation.

Pulse-chase analyses.

Approximately 107 cells per time point were washed in DMEM without methionine supplemented with 10% dialyzed FCS and incubated in similar medium for 30 min at 37°C. Cells were pulsed-labelled for 4 h with 35S cell labelling mix (Amersham) at 50 to 100 μCi/ml and then washed with warm PBS before being placed in complete DMEM. Cells were lysed as described above at hourly time points. Lysates were precleared overnight at 4°C with normal rabbit immunoglobulin and killed Staphylococcus aureus. Immunoprecipitations were performed by incubating lysates with immobilized antibodies, and immune complexes were washed and separated by SDS-PAGE. Immunoprecipitated proteins were visualized by fluorography using Amplify (Amersham).

Preparation of bacterially expressed recombinant protein.

For use in CDK4 kinase assays, a C-terminal fragment of human RB (amino acids 773 to 928) fused to GST was utilized as an in vitro substrate (32). Briefly, BL21(DE3)pLysS Escherichia coli transformed with pGEX-RBCT were induced at room temperature with 0.1 mM IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) for 3 h. Bacterial pellets were lysed by the addition of ice-cold Tween 20 lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES [pH 7.5], 10 mM MgCl2, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% Tween 20, 1 mM DTT, 25 μM ATP, aprotinin [5 μg/ml], leupeptin [5 μg/ml], pepstatin [5 μg/ml], Pefabloc [5 μg/ml]) and sonication. Soluble fusion proteins were purified by affinity chromatography on glutathione-agarose and eluted with 20 mM reduced glutathione. Positive fractions containing the fusion protein were pooled and dialyzed overnight against kinase assay buffer (50 mM HEPES [pH 8.0], 10 mM MgCl2, 2.5 mM EGTA, 1 mM DTT, 50 μM ATP) plus 20% glycerol. Dialyzed GST RB was dispensed as aliquots and stored at −80°C. GST fusion proteins that were to be used as immunogens were dialyzed against PBS containing 1 mM DTT and stored at −80°C until required.

Kinase assays.

Kinase assays were carried out according to an adaptation of a previously described protocol (30) using the GST RB C-terminal (GST-RBCT) construct described above as a substrate. Cells were lysed in Tween 20 lysis buffer and immunoprecipitated as described above. Immune complexes were washed three times with Tween 20 lysis buffer and twice with kinase reaction buffer (50 mM HEPES [pH 8.0], 10 mM MgCl2, 2.5 mM EGTA, 1 mM DTT, 50 μM ATP). GST RB (2.5 μg) and 10 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP (Amersham) were added to each sample, and the volume was made up to 50 ml with kinase reaction buffer. Reactions were incubated at 30°C for 20 min and stopped by adding 6× SDS sample buffer. Phosphorylated products were resolved on an SDS–12% polyacrylamide gel and analyzed by autoradiography at room temperature.

RESULTS

CDK4 and CDK6 have different gel filtration profiles.

We have previously shown by gel filtration that CDK6 from CEM cells is present in three major complexes, implying biochemical regulation of CDK6 interactions within cells (27). A 450-kDa complex comprises CDK6 complexes with chaperone molecules such as HSP90 and CDC37. A minor complex that migrates at approximately 150 to 170 kDa contains cyclin D-CDK6 complexes. When assayed in vitro with a GST RB substrate, this fraction of CDK6 is kinase active. Finally, CDK6 is present in a smaller, ∼55-kDa complex that comprises independent binary complexes of CDK6 with INK4 proteins, as well as potentially monomeric forms of the kinase. To examine whether CDK4 regulation was similar to that of CDK6, we extended these analyses in a range of cell lines (Table 1) and compared the properties of CDK4 and CDK6 by gel filtration.

TABLE 1.

Expression of D-type cyclins, CDK4, CDK6, and CDK inhibitors in a panel of cell lines

| Cell line | Expressiona of:

|

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D1 | D2 | D3 | CDK4 | CDK6 | p15 | p16 | p18 | p19 | p21 | p27 | |

| ML1 | + | − | ++ | + | ++ | +/− | − | ++ | + | + | ++ |

| EL4 | ++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | +++ | + | − | ++ | ++ | ++ | +++ |

| CEM | − | − | +++ | + | +++ | + | − | ++ | ++ | + | + |

| 293 | + | + | + | +++ | ++ | − | +++ | ++ | − | +/− | +/− |

| WI38 | ++ | + | + | +++ | + | +/− | + | +/− | − | ++ | + |

| MCF7 | +++ | ++ | + | +++ | + | − | − | + | − | ++ | + |

+++, ++, +, +/−, and −, relative intensites of the signal, from strongest to below the level of detection with the available antisera.

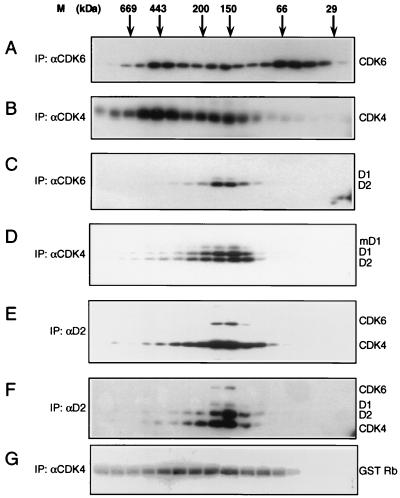

Whole-cell extracts were prepared from EL4 cells, a T-lymphoma cell line that expresses roughly equivalent levels of both CDK4 and CDK6 as well as all three D-type cyclins (27) (Table 1). These extracts were fractionated by gel filtration on Superdex 200 and immunoprecipitated with αCDK4 or αCDK6 serum. The immune complexes were then separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with the precipitating sera to detect the independent complexes. As expected, the presence of CDK6 in three complexes was revealed (Fig. 1A). In contrast, CDK4 from these cells was present in only two major complexes, of approximately 450 and 170 kDa (Fig. 1B). CDK4 complexes corresponding to the 55-kDa CDK6 complex were barely detectable. Identical profiles were obtained when fractionated whole-cell extract from EL4 cells was directly immunoblotted with αCDK4 or αCDK6 serum, suggesting that the observed difference was not due to an inability of our CDK4 serum to recognize any putative 55-kDa CDK4 complexes (data not shown). The same Western blots were subsequently reprobed with αD1 and αD2 sera, singly or in combination. Both CDK4 and CDK6 were found to associate with these cyclins in complexes of approximately 150 to 170 kDa (Fig. 1C and D). The faint band visible above cyclin D1 in Fig. 1C corresponds to the mouse-specific, modified form of this molecule (p37 mD1) (3, 31). In agreement with previous findings (6, 47), the larger, 450-kDa CDK4 complex was found to contain CDC37 and HSP90 (data not shown). In reciprocal experiments, αD2 serum was used to immunoprecipitate fractionated EL4 extract. Following SDS-PAGE, immune complexes were immunoblotted with αCDK4 and αCDK6 sera (Fig. 1E). CDK4- and CDK6-containing complexes detected by this approach were found to be approximately 150 to 170 kDa in size, which is in agreement with the results achieved via precipitation through the kinase partner. When reprobed with αD2 serum, it was apparent that all of the detectable cyclin D2 was eluted in such complexes (Fig. 1F). Similar experiments with a variety of cell lines gave comparable results for all three D-type cyclins (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Gel filtration analysis of CDK4 and CDK6. EL4 whole-cell extract was separated and immunoprecipitated with αCDK6 serum (A) or αCDK4 serum (B) followed by blotting with the precipitating antiserum to reveal the different complexes. Blots were reprobed with αD1 and αD2 sera (C and D). (E) Column fractions were immunoprecipitated with αD2 serum and immunoblotted with a mixture of αCDK4 and αCDK6 sera. This blot was then reprobed with αD2 (F). (G) CDK4 kinase assays on similar EL4 fractions, with GST-RBCT used as a substrate. M, molecular mass markers; IP, immunoprecipitation.

Since the majority of the cyclin D-CDK4 complexes were indistinguishable in size from CDK6 complexes previously demonstrated to be kinase competent in vitro (27), we wanted to confirm that the 150- to 170-kDa CDK4 complexes were active. Following gel filtration, CDK4 immunocomplex kinase assays were performed with the GST RBCT construct (32) as a substrate. CDK4 kinase activity was found to correlate with elution of detectable cyclin D-CDK4 complexes in these cells (Fig. 1G). Therefore, although broadly similar, CDK4 and CDK6 gel filtration profiles from EL4 cell extract exhibit a clear difference, as CDK4 does not form detectable 55-kDa complexes analogous to the CDK6-INK4 moiety previously identified in proliferating cells.

Members of the INK4 family differ in ability to form complexes with both CDK4 and CDK6.

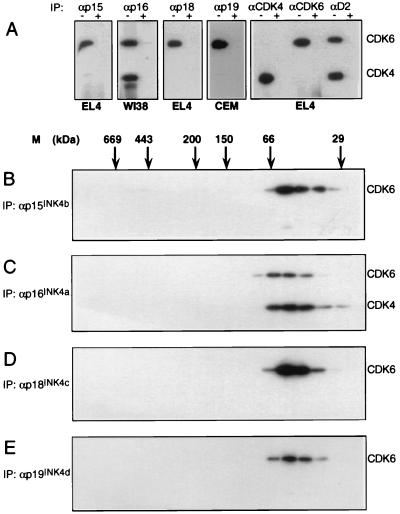

To examine CDK4 association with INK4 family members, we surveyed INK4-CDK4 and -CDK6 interactions in a variety of cell lines by using specific αINK4 sera (Table 2). Representative samples of the data are shown in Fig. 2A. Significantly, only p16INK4a was found to form steady-state complexes with both CDK4 and CDK6, as shown by immunoprecipitation from WI38 diploid fibroblasts. In contrast, p15INK4b, p18INK4c, and p19INK4d immunoprecipitations from asynchronously growing cells contained CDK6 but no detectable CDK4. Under similar conditions, CDK4 was detected in αD2 complexes, suggesting that CDK4 functions normally in these cells (Fig. 2A). To address the stoichiometries of these interactions, whole-cell extracts were fractionated by gel filtration and subjected to immunoprecipitation with specific αINK4 sera. Binary complexes of p16INK4a with CDK4 and p16INK4a with CDK6 were present in WI38 lysates (Fig. 2C). However, when assayed by this method the other INK4 family members formed 55-kDa complexes with CDK6 only (Fig. 2B, D, and E). The blots were reprobed with the precipitating antiserum to reveal the elution profiles of the various INK4 molecules. In the cell lines tested, all four INK4 family members coeluted with CDK4 or CDK6 in complexes of ∼55 kDa. INK4 proteins were not detected in complexes outside of this size range (data not shown). Overall, an interesting correlation between absence of p16INK4a and lack of 55-kDa CDK4 complexes was observed, suggesting that the majority of INK4 family members interact with CDK6 but not CDK4 under these conditions.

TABLE 2.

Analysis of CDK4 and CDK6 interactions in a panel of cell linesa

| Cell line | CDK4 complexes with:

|

CDK6 complexes with:

|

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D | p15 | p16 | p18 | p19 | p21 | p27 | D | p15 | p16 | p18 | p19 | p21 | p27 | |

| ML1 | + | +/− | − | − | − | + | ++ | +++ | ++ | − | ++ | ++ | +/− | + |

| EL4 | +++ | − | − | − | − | +++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | − | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| CEM | + | − | − | − | − | + | + | +++ | ++ | − | ++ | ++ | + | ++ |

| 293 | − | − | +++ | ++ | − | − | − | − | − | +++ | ++ | − | − | − |

| WI38 | ++ | − | ++ | − | +/− | ++ | +/− | ++ | − | ++ | +/− | − | + | +/− |

| MCF7 | +++ | − | − | − | − | ++ | + | ++ | − | − | + | − | + | + |

See footnote to Table 1 for explanation of symbols.

FIG. 2.

INK4-CDK4 and INK4-CDK6 interactions. (A) Cell lysates from EL4, WI38, and CEM cell lines were subjected to immunoprecipitation with specific αINK4 serum with (+) or without (−) peptide block as indicated. Anti-CDK4, αCDK6, and αD2 immunoprecipitations were included as controls. Immune complexes were separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with a mixture of αCDK4 and αCDK6 sera. Similar analyses were then performed on fractionated whole-cell extracts. (B) Fractionated EL4 extract was immunoprecipitated with αp15INK4b and immunoblotted with αCDK4-αCDK6. (C) Similarly, WI38 lysate was fractionated and immunoprecipitated with αp16INK4a, followed by blotting with αCDK4-αCDK6. Likewise, EL4 and CEM fractions were immunoprecipitated with αp18INK4c (D) and αp19INK4d (E), respectively, and probed with αCDK4-αCDK6. IP, immunoprecipitation.

All INK4 family members associate with CDK4 and CDK6 in vitro.

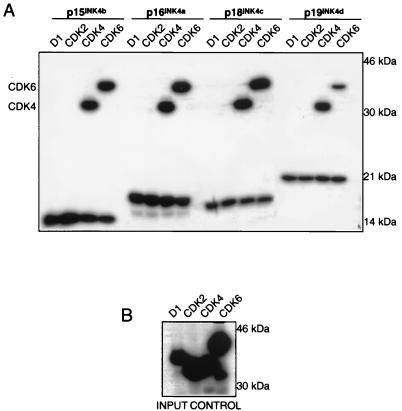

The differences in CDK4 and CDK6 binding found in vivo were unexpected, as members of the INK4 family are highly homologous in pairwise comparisons. One explanation for the data is that p15INK4b, p18INK4c, and p19INK4d do not bind CDK4. Indeed, p18INK4c was originally reported to be a specific CDK6 inhibitor (9). We performed in vitro binding assays using [35S]methionine-labelled, in vitro translates of all INK4 family members and CDK4 and CDK6. Cyclin D1 and CDK2 were used as negative controls for interaction. Under these conditions, all four INK4 family members bound CDK4 and CDK6 with similar affinities (Fig. 3A). Samples of cyclin D1, CDK2, CDK4, and CDK6 in vitro translates were run on a separate gel to control for input levels (Fig. 3B). Viewed in combination with the immunoprecipitation data, these data provide evidence that all INK4 proteins are capable of association with both CDK4 and CDK6 in vitro. However, detectable, steady-state complexes between p15INK4b, p18INK4c, or p19INK4d and CDK4 do not accumulate in proliferating cells.

FIG. 3.

In vitro binding of INK4 inhibitors to CDK4 and CDK6. (A) Freshly prepared D1, CDK2, CDK4, and CDK6 in vitro translates were mixed with individual INK4 in vitro translates, as indicated (A). Complexes were immunoprecipitated using specific antisera, separated by SDS-PAGE in a 12% gel, and visualized by autoradiography. (B) Aliquots of input in vitro translates were separated on another gel as a loading control.

CDK4 forms unstable complexes with p18INK4c in vivo.

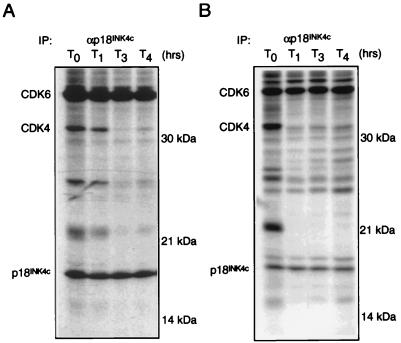

To test the hypothesis that the stability of INK4-CDK4 and -CDK6 interactions differ among family members, we performed pulse-chase experiments with two cell lines, EL4 and ML1. Cells were labelled with [35S]methionine and chased in nonradioactive medium over a 4-h time course. Lysates were prepared, and αp18INK4c immunoprecipitations were performed at hourly time points. Under these conditions, newly synthesized CDK6 and CDK4 were found to associate with p18INK4c at time zero, indicating that both kinases do indeed associate with p18INK4c, which confirms the in vitro binding experiments. However, during the chase in nonradioactive medium, 35S-labelled CDK4 disappeared rapidly from p18INK4c complexes in both cell lines analyzed (Fig. 4), whereas CDK6 remained associated with p18INK4c throughout the duration of the experiment. In control experiments, both CDK4 and CDK6 were found to possess long half-lives when measured by specific immunoprecipitation (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Stability of p18INK4c-CDK complexes. Logarithmically growing cultures of EL4 (A) and ML1 (B) cells were pulse-labelled with [35S]methionine and chased with medium containing unlabelled amino acids. At the time points indicated, cell extracts were prepared and subjected to immunoprecipitation (IP) with specific αp18INK4c sera. Immune complexes were separated by SDS-PAGE in a 12% gel.

CDK4 is found in steady-state, ternary complexes with cyclin D and p21CIP1-p27KIP1.

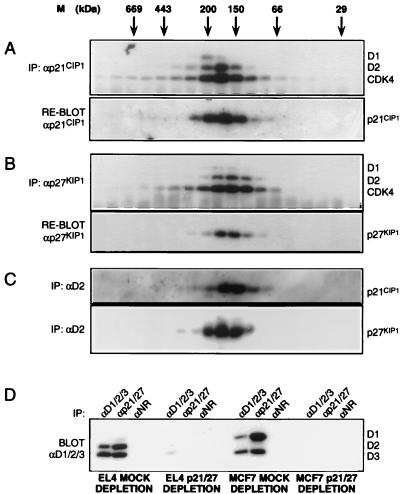

CDK4 does not form stable complexes with p18INK4c in EL4 and ML1 cells. In other metabolic labelling experiments, newly synthesized CDK4 was also detected in αp15INK4b and αp19INK4d immunoprecipitations (data not shown), implying that CDK4 forms similar short-lived complexes with these INK4 molecules. However, CDK4 is detectable by Western blotting as one component of a 150- to 170-kDa moiety, suggesting that in this context CDK4 is part of a stable complex. The D-type cyclins also contribute to this complex (Fig. 1). Other likely candidates for cyclin D-CDK interacting proteins were members of the p21 family of CDK inhibitors. To examine the distribution of p21 family molecules, EL4 whole-cell extracts were fractionated by gel filtration and immunoprecipitated with specific αp21CIP1 or αp27KIP1 sera. Immune complexes were separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with αD2 and αCDK4 sera. αp21CIP1 immunoprecipitations revealed a 150- to 170-kDa, p21CIP1-D2-CDK4 complex (Fig. 5A, upper panel). When reprobed with αp21CIP1, it was apparent that p21CIP1 was not detectable in complexes outside of this molecular mass range (Fig. 5A, lower panel). Virtually identical results were obtained for p27KIP1-containing complexes when αp27KIP1 serum was used as the precipitating antibody (Fig. 5B). Furthermore, similar profiles were obtained when p21CIP1-D2-CDK6 and p27KIP1-D2-CDK6 complexes were analyzed by gel filtration (data not shown). To confirm the ternary nature of these complexes, similar gel filtrations were performed, and fractions were immunoprecipitated with αD2 sera, separated by SDS-PAGE, and immunoblotted with αp21CIP1 (Fig. 5C, upper panel) or αp27KIP1 (Fig. 5C, lower panel). Thus, the majority of D-type cyclins and p21CIP1 and p27KIP1 are associated in readily detectable 150- to 170-kDa complexes. To rule out the possibility that p21CIP1 and p27KIP1 reside in the same complex simultaneously, αp21CIP1 immunoprecipitations were immunoblotted with αp27KIP1 sera, and vice versa. We could find no evidence for such quarternary interactions (data not shown). To estimate the fraction of the 150- to 170-kDa cyclin D-CDK complex that was associated with p21 family members, immunodepletion experiments using lysates prepared from two cell lines, EL4 (T lymphoma) and MCF7 (breast adenocarcinoma), were performed. Whole-cell extracts were subjected to immunodepletion with either normal rabbit immunoglobulin G or a combination of both αp21CIP1 and αp27KIP1 sera. The depleted extracts were then divided equally and immunoprecipitated with αD1-D2-D3, αp21CIP1-p27KIP1, or normal rabbit immunoglobulin G. The resulting immune complexes were separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with a mixture of αD1-D2-D3 sera. Significantly, all three D-type cyclins were removed from EL4 and MCF7 extracts upon immune depletion of p21CIP1 and p27KIP1 (Fig. 5D). There was no diminution of the D-type cyclin signal in αD1-D2-D3 or αp21CIP1-p27KIP1 immunoprecipitations performed with mock-depleted extracts of either cell line. Although not quantitative, these data strongly suggest that the majority of detectable cyclin D-CDK complexes contain either p21CIP1 or p27KIP1.

FIG. 5.

Analysis of p21CIP1 and p27KIP1 by gel filtration. EL4 whole-cell extracts were prepared and fractionated over Superdex 200. (A) Fractions were immunoprecipitated with αp21CIP1 sera and immunoblotted with a mixture of αD1-αD2 and αCDK4 sera (upper panel). The blot was then reprobed with αp21CIP1 (lower panel). (B) Immunoprecipitates from a similar EL4 fractionation using αp27KIP1 sera were immunoblotted in the same way. (C) α-D2 serum was used to immunoprecipitate complexes following gel filtration. After SDS-PAGE, the immune complexes were immunoblotted with sera specific for p21CIP1 (upper panel) or p27KIP1 (lower panel). (D) Mock-depleted and αp21CIP1-αp27KIP1-immunodepleted extracts of EL4 and MCF7 cells were subjected to immunoprecipitation with αD1-D2-D3, αp21CIP1-αp27KIP1 or normal rabbit serum, as indicated. Immune complexes were separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with a mixture of αD1/D2/D3 sera. IP, immunoprecipitation.

Both p16INK4a and p21CIP1 form stable complexes with CDK4.

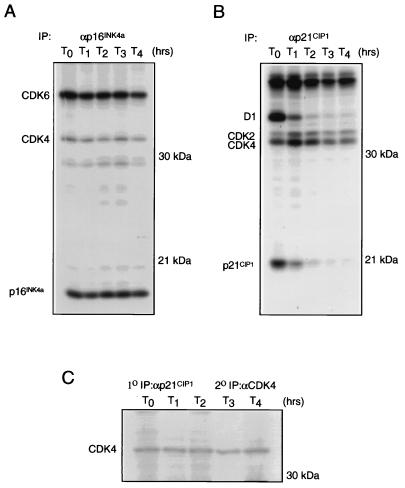

In pulse-chase experiments, CDK4 has a long-half-life interaction with p16INK4a (38), an observation supported by the relative ease with which both CDK4 and CDK6 can be detected in αp16INK4a immunoprecipitations. Other INK4 molecules seem less able to form stable complexes with CDK4 (Fig. 2 and 4) in the cell lines tested. Conversely, the abundance of CDK4 present in steady-state p21CIP1 complexes implies that cyclin D-CDK4-p21CIP1 ternary complexes have long half-lives. To compare the duration of CDK4 in p16INK4a- and p21CIP1-containing complexes, we performed pulse-chase analyses with WI38 primary fibroblasts, a cell line that expresses both proteins (Table 1). At each time point, lysates were prepared and immunoprecipitated with antisera specific for p16INK4a or p21CIP1. The resulting immune complexes were separated by SDS-PAGE, and the turnover rate of coprecipitated CDK4 was assessed by fluorography.

As expected, αp16INK4a immunoprecipitations contained 35S-labelled CDK4 and CDK6 throughout the time course, with the half-lives of these complexes being in excess of 4 h (Fig. 6A), which is in good agreement with previous findings (36, 38). Using αp21CIP1 sera to measure the stability of associated CDK4 revealed a stable, associated band migrating at approximately 33 kDa during SDS-PAGE (Fig. 6B). Since CDK2 is also known to associate with p21CIP1 (8) and has a mobility similar to that of CDK4 in SDS-PAGE, we wanted to definitively demonstrate the stability of CDK4 in such complexes. The pulse-chase was repeated, and the resulting αp21CIP1 immune complexes were denatured and subsequently reimmunoprecipitated with αCDK4 sera. As shown in Fig. 6C, CDK4 molecules reimmunoprecipitated from p21CIP1 complexes have a half-life similar to those coprecipitated with p16INK4a. In similar pulse-chases performed with other cell lines, CDK4 was repeatedly observed to be stable in p21CIP1 complexes (data not shown). The stability of CDK4 in the context of ternary complexes with D-type cyclins and p21CIP1 suggests that p21CIP1 affects the distribution of CDK4 between INK4 and cyclin D-associated states. Significantly, p21CIP1 consistently demonstrated a half-life of approximately 1 to 2 h, substantially shorter than the half-lives observed for p16INK4a and p18INK4c.

FIG. 6.

Relative stabilities of p16INK4a and αp21CIP1-bound CDK4. Logarithmically growing cultures of WI38 cells were pulse-labelled with [35S]methionine and chased with medium containing unlabelled amino acids. At the time points indicated, extracts were prepared and immunoprecipitated with specific αp16INK4a (A) or αp21CIP1 (B) sera. Immune complexes were separated by SDS-PAGE in a 12% gel. (C) Metabolically labelled CDK4 reimmunoprecipitated from an αp21CIP1 pulse-chase. IP, immunoprecipitation.

CDK4 forms stable complexes with p16INK4a and p18INK4c in cells that lack cyclin D-CDK4-p21CIP1 ternary complexes.

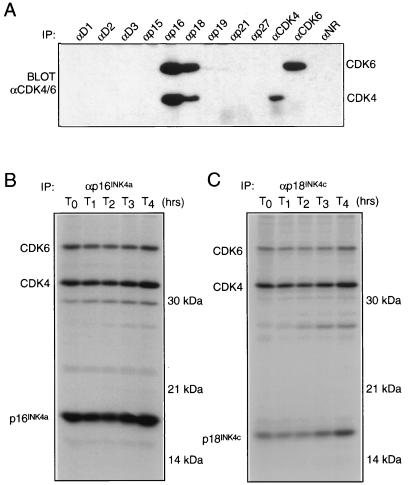

Pulse-chase analyses with WI38 cells suggested that p21 family members influence the interactions of CDK4 via competitive stabilization, thus antagonizing the effects of INK4 molecules. We were interested in examining the distribution of CDK4 in cells without ternary cyclin D-CDK-p21CIP1 complexes, such as human cell lines that lack functional pRB (4). In such cells, CDK4 and CDK6 are found associated with p16INK4a, and 293 is a cell line that conforms to this paradigm. 293 cells express p18INK4c and undetectable levels of both p21CIP1 and p27KIP1 (data not shown) on a background of extremely high p16INK4a expression. This allowed analysis of different INK4-CDK4 interactions in a setting independent of p21CIP1.

To confirm the lack of detectable cyclin D-CDK-p21CIP1 complexes in 293 cells, whole-cell extracts were prepared and immunoprecipitated with a variety of specific antisera. Immune complexes were separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with αCDK4 and αCDK6 sera. As expected, CDK4 and CDK6 were not detectable in αD1-D2-D3 or αp21CIP1-p27KIP1 immune complexes. Both kinases were present at high levels in αp16INK4a immune complexes. Significantly, αp18INK4c immune complexes were found to contain both CDK6 and CDK4 (Fig. 7A). To establish whether CDK4 forms long-lived complexes with p18INK4c under these conditions, pulse-chase experiments were performed with αp16INK4a and αp18INK4c sera. Consistent with the immunoblot analysis, CDK4 was found to form long-half-life complexes with both p16INK4a and p18INK4c in these cells (Fig. 7B and C).

FIG. 7.

CDK4 complexes in 293 cells. (A) 293 whole-cell extract was immunoprecipitated with the antisera shown. Immune complexes were separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with a combination of αCDK4 and αCDK6 sera. Asynchronously growing cultures of 293 cells were pulse-labelled with [35S]methionine and chased with medium containing unlabelled amino acids. At the time points indicated, cell extracts were prepared and immunoprecipitated with specific αp16INK4a (B) or αp18INK4c (C) sera. Immune complexes were separated by SDS-PAGE in a 12% gel. IP, immunoprecipitation.

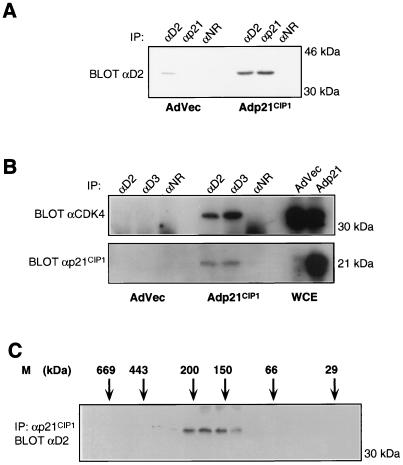

Overexpression of p21CIP1 in 293 cells restores p21CIP1-cyclin D-CDK4 ternary complexes.

The experiments outlined above demonstrate that CDK4 contributes to several independent complexes within cells and suggest that CDK4 may be involved in a dynamic equilibrium between INK4-bound and p21CIP1- or p27KIP1-bound states. To test this hypothesis, 293 cells were infected with recombinant adenovirus vectors expressing p21CIP1 under the control of a cytomegalovirus promoter (Adp21CIP1), or with vector control viruses (AdVec) (49). At 24 h postinfection, lysates were prepared and equivalent amounts were subjected to immunoprecipitation with αD2, αp21CIP1, or normal rabbit serum. Following SDS-PAGE, the immune complexes were immunoblotted with αD2 sera. In AdVec-infected lysates, low levels of cyclin D2 were detected in the αD2 immunoprecipitate, and no cyclin D2 was detectable in αp21CIP1 immunoprecipitates (Fig. 8A). Following infection with Adp21CIP1, the total level of cyclin D2 detected in αD2 immune complexes appeared elevated, suggesting that the introduction of p21CIP1 affected the steady-state levels of this protein (Fig. 8A). Significantly, in the αp21CIP1 immunoprecipitate from Adp21CIP1-infected lysate, cyclin D2 was present at a level similar to that seen in the adjacent αD2 immune complex, providing evidence that the majority of the cyclin D2 present in these cells was now associated with p21CIP1. Next, we tested for the presence of CDK4 and p21CIP1 in αD2 and αD3 immunoprecipitates from similarly infected lysates. As expected, in AdVec-infected cells no CDK4 was detectable in αD2 or αD3 immune complexes, whereas in lysate prepared from Adp21CIP1 infected cells, CDK4 was efficiently coimmunoprecipitated with cyclins D2 and D3 (Fig. 8B, upper panel). Aliquots of whole-cell extract separated on the same gel demonstrate that equivalent levels of CDK4 were present in both lysate preparations. The blot was subsequently reprobed with αp21CIP1 sera (Fig. 8B, lower panel). As expected, p21CIP1 was readily detected in Adp21CIP1- but not AdVec-infected whole-cell extracts. Significantly, in Adp21CIP1 lysates, p21CIP1 was coimmunoprecipitated with cyclin D2-CDK4 and cyclin D3-CDK4 complexes. These data suggest that p21CIP1 is able to stimulate the formation of cyclin D-CDK4-p21CIP1 ternary complexes, even in the presence of excess p16INK4a. To confirm this, whole-cell extract prepared from Adp21CIP1-infected 293 cells was fractionated by gel filtration and immunoprecipitated with αp21CIP1 sera. Immune complexes were separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with αD2. Cyclin D2 was found associated with p21CIP1 in a 150- to 170-kDa complex (Fig. 8C), which is in good agreement with similar complexes detected previously in EL4 cells (Fig. 5).

FIG. 8.

Stimulation of cyclin D-CDK4 interaction by p21CIP1. (A) 293 cells were infected with AdVec or Adp21CIP1 adenoviruses, and lysates were immunoprecipitated with αD2, αp21CIP1, or normal rabbit sera (αNR), as indicated. Following SDS-PAGE, the immune complexes were probed with αD2 sera. (B) Similar infections were immunoprecipitated with αD2, αD3, or normal rabbit sera. Immune complexes were separated by SDS-PAGE alongside equivalents of whole-cell extract prepared from the same samples. Following transfer, the membrane was immunoblotted with αCDK4 serum (upper panel) or αp21CIP1 serum (lower panel). (C) Adp21CIP1 293 cell lysate was separated on Superdex 200. Fractions were collected and immunoprecipitated with αp21CIP1 sera. Immune complexes were separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with αD2 serum. IP, immunoprecipitation.

DISCUSSION

Gel filtration analyses of CDK4 and CDK6.

Both CDK4 and CDK6 form large multimeric complexes with chaperone molecules such as HSP90 and CDC37 that elute at ∼450 kDa following gel filtration (6, 27, 47). Similarly, both kinases coelute with the peak of cyclin D in complexes with a molecular mass of 150 to 170 kDa that are capable of efficiently phosphorylating a GST RB substrate in vitro. A major difference between the CDK4 and CDK6 gel filtration profiles was the apparent lack of a 55-kDa CDK4 complex. We had previously demonstrated that the 55-kDa CDK6 complex comprises CDK6-p19INK4d complexes (27). The gel filtration observations implied that CDK4 did not associate with the INK4 proteins present in the cell lines analyzed. Consistent with this, CDK4 was not found in p15INK4b, p18INK4c, or p19INK4d immune complexes isolated from a variety of cells, indicating that although these inhibitors bound CDK6, they did not form complexes with CDK4 that were detectable on Western blots. A common feature of the immortalized cell lines analyzed is a lack of p16INK4a expression. When we examined WI38 primary diploid fibroblasts, CDK4 was identified in association with p16INK4a in 55-kDa complexes that had properties similar to those of the various 55-kDa CDK6-INK4 complexes. This correlation suggests that p16INK4a alone can titrate CDK4 into inactive binary complexes in asynchronously growing cells.

INK4-CDK4 interactions.

The INK4 protein, p18INK4c, was originally described as a CDK6-specific inhibitor because of a lack of association with CDK4 in CEM cells (9). However, p18INK4c overexpression is sufficient to arrest cells that express CDK4 as well as CDK6 in a pRB-dependent manner, implying that p18INK4c is capable of inhibiting the activity of CDK4 under certain circumstances (9, 18). The apparent inability of certain INK4 family members to bind CDK4 in vivo is surprising, since in vitro, all four INK4 family members associate with CDK4 and CDK6 equally well (Fig. 3). When we analyzed interactions between newly synthesized components in pulse-chase experiments, it became apparent that INK4 molecules such as p18INK4c do indeed associate with CDK4 in cells, but such complexes are short-lived in comparison to analogous CDK6-containing complexes. The transient nature of p18INK4c-CDK4 association in these cells provides a possible explanation for the lack of detectable interactions on Western blots. Significantly, when we examined p18INK4c interactions in cell lines such as 293 that lack cyclin D-CDK complexes, p18INK4c was found associated with both CDK4 and CDK6 in stable binary complexes indistinguishable from similar p16INK4a complexes (Fig. 7). It is possible, therefore, that cellular context influences the distribution of CDK4 and CDK6, with CDK4 being particularly sensitive to changes in subunit concentration. The exact mechanism that determines the half-lives of the different INK4-CDK4 complexes is unclear at present, although it seems likely that CDK4 interactions are strongly influenced by intracellular levels of D-type cyclins and p21 family members.

p21CIP1 as a holoenzyme stabilizer.

Although CDK4 does not normally form long-half-life associations with p18INK4c, it is found in steady-state complexes containing D-type cyclins in a variety of proliferating cell lines that retain functional pRB (Fig. 1). Upon analysis, such complexes were also found to contain p21 family members (Fig. 5). Moreover, following immunodepletion experiments it was apparent that the majority of cyclin D-CDK4 complexes are associated with p21CIP1 and p27KIP1. These findings extend previous observations (20) and imply that all detectable cyclin D-CDK complexes in asynchronously growing cells are associated with either p21CIP1 or p27KIP1 in 150- to 170-kDa complexes that are kinase active (Fig. 1G) (33). Additionally, pulse-chase analyses demonstrated that CDK4 has a long-half-life interaction with complexes containing p21CIP1 (Fig. 6), suggesting that p21 family members might influence ternary cyclin D-CDK interactions via stabilization. In agreement with this, expression of p21CIP1 can reconstitute detectable cyclin D-CDK4-p21CIP1 ternary complexes in 293 cells, even in the presence of excess p16INK4a (Fig. 8). We attempted to discover whether enforced expression of p21CIP1 led to a concomitant decrease in the level of p16INK4a-CDK4 or p18INK4c-CDK4 complexes, but were unable to definitively demonstrate such a decrease by immunoprecipitation-Western blot analyses or pulse-chase approaches (data not shown). It is likely that the extremely high level of INK4 activity (p16INK4a in combination with p18INK4c) in 293 cells continually interferes with cyclin D-CDK-p21CIP1 assembly, resulting in a process that is detectable but intrinsically inefficient. We estimate that the majority of CDK4 remains associated with p16INK4a-p18INK4c in this experimental system. Also, because p21CIP1 can interact with many other cyclin-CDK complexes, the specific concentration available to contribute to cyclin D-CDK assembly may actually be very low.

Both p16INK4a and p18INK4c are very stable molecules. In contrast, p21CIP1 and cyclin D1 demonstrate significantly shorter half-lives. Since the pool of metabolically labelled CDK4 associated with p21CIP1-cyclin D complexes remains relatively constant during pulse-chase experiments, the cyclin D and p21CIP1 components must be continually replaced by newly synthesized, unlabelled molecules during the time course. Therefore, constant synthesis of p21CIP1 may be required to allow accumulation of ternary complexes in the presence of competing INK4 family members. Consistent with this, many different mitogenic signals induce expression of p21CIP1 as well as members of the type D cyclin family during the G1 phase of the cell cycle (23, 43, 51). Taken together, these data suggest that during normal proliferation, p21 family members antagonize the inhibitory threshold function of the INK4 family, by stabilizing ternary cyclin D-CDK-p21CIP1 complexes in vivo.

Subunit arrangement and tumorigenesis.

CDK inhibitors play pivotal regulatory roles during the mammalian cell cycle by restraining the activity of cyclin-CDK complexes that might otherwise lead to inappropriate hyperphosphorylation of the RB tumor suppressor gene product. Because of this, all CDK inhibitors have been considered as candidate tumor suppressor genes. However, data compiled by numerous research groups from many different tumor types have demonstrated that p16INK4a alone is commonly affected in human cancers. The apparent inability of INK4 family members other than p16INK4a to suppress cyclin D-CDK4 association during normal proliferation, coupled with observations that p21 family members promote the formation of active cyclin D-CDK4 complexes during a mitogenic response, provides potential explanations as to why p16INK4a alone is specifically targeted during tumorigenesis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank members of the Lees, McMahon, and Bolen laboratories for thoughtful comments and suggestions; in particular we thank Frances Shanahan, Wolfgang Seghezzi, Wouter Korver, Douglas Woods, and Michael Tomlinson for critical reading of the manuscript. Also, we are grateful to Maribel Andonian and Gary Burget for assistance with graphics.

DNAX Research and Canji Incorporated are supported by Schering Plough Corporation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aagaard L, Lukas J, Bartkova J, Kjerulff A-A, Strauss M, Bartek J. Aberrations of p16Ink4 and retinoblastoma tumour-suppressor genes occur in distinct sub-sets of human cancer cell lines. Int J Cancer. 1995;61:115–120. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910610120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alcorta D, Xiong Y, Phelps D, Hannon G, Beach D, Barrett J. Involvement of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p16 (INK4a) in replicative senescence of normal human fibroblasts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:13742–13747. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.24.13742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bates S, Bonetta L, MacAllan D, Parry D, Holder A, Dickson C, Peters G. CDK6 (PLSTIRE) and CDK4 (PSK-J3) are a distinct set of the cyclin-dependent kinases that associate with cyclin D1. Oncogene. 1994;9:71–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bates S, Parry D, Bonetta L, Vousden K, Dickson C, Peters G. Absence of cyclin D/cdk complexes in cells lacking functional retinoblastoma protein. Oncogene. 1994;9:1633–1640. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brookes S, Lammie G, Schuuring E, de Boer C, Michalides R, Dickson C, Peters G. Amplified region of chromosome band 11q13 in breast and squamous cell carcinomas encompasses three CpG islands telomeric of FGF3, including the expressed gene EMS1. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 1993;6:222–231. doi: 10.1002/gcc.2870060406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dai K, Kobayashi R, Beach D. Physical interaction of mammalian CDC37 with CDK4. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:22030–22034. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.36.22030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.El-Deiry W S, Tokino T, Velculescu V E, Levy D B, Parsons R, Trent J M, Lin D, Mercer W E, Kinzler K W, Vogelstein B. WAF1, a potential mediator of p53 tumor suppression. Cell. 1993;75:817–825. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90500-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gu Y, Turck C W, Morgan D O. Inhibition of CDK2 activity in vivo by an associated 20K regulatory subunit. Nature. 1993;366:707–710. doi: 10.1038/366707a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guan K-L, Jenkins C W, Li Y, Nichols M A, Wu X, O’Keefe C L, Matera A G, Xiong Y. Growth suppression by p18, a p16INK4/MTS1 and p14INK4B/MTS2-related CDK6 inhibitor correlates with wild-type pRb function. Genes Dev. 1994;8:2939–2952. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.24.2939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guan K-L, Jenkins C W, Li Y, O’Keefe C L, Noh S, Wu X, Zariwala M, Matera A G, Xiong Y. Isolation and characterization of p19INK4d, a p16-related inhibitor specific to CDK6 and CDK4. Mol Biol Cell. 1996;7:57–70. doi: 10.1091/mbc.7.1.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hall M, Peters G. Genetic alterations of cyclins, cyclin-dependent kinases, and Cdk inhibitors in human cancer. Adv Cancer Res. 1996;68:67–108. doi: 10.1016/s0065-230x(08)60352-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hannon G J, Beach D. p15INK4B is a potential effector of TGF-beta-induced cell cycle arrest. Nature. 1994;371:257–261. doi: 10.1038/371257a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hara E, Smith R, Parry D, Tahara H, Stone S, Peters G. Regulation of p16CDKN2 expression and its implications for cell immortalization and senescence. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:859–867. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.3.859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harlow E, Lane D. Antibodies: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harper J W, Adami G R, Wei N, Keyomarsi K, Elledge S J. The p21 Cdk-interactting protein Cip1 is a potent inhibitor of G1 cyclin-dependent kinases. Cell. 1993;75:805–816. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90499-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harper J W, Elledge S J, Keyomarsi K, Dynlacht B, Tsai L-H, Zhang P, Dobrowolski S, Bai C, Connell-Crowley L, Swindell E, Fox M P, Wei N. Inhibition of cyclin-dependent kinases by p21. Mol Biol Cell. 1995;6:387–400. doi: 10.1091/mbc.6.4.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.He J, Allen J R, Collins V P, Allalunis T M, Godbout R, Day R R, James C D. CDK4 amplification is an alternative mechanism to p16 gene homozygous deletion in glioma cell lines. Cancer Res. 1994;54:5804–5807. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hirai H, Roussel M F, Kato J-Y, Ashmun R A, Sherr C J. Novel INK4 proteins, p19 and p18, are specific inhibitors of the cyclin D-dependent kinases CDK4 and CDK6. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:2672–2681. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.5.2672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koh J, Enders G H, Dynlacht B D, Harlow E. Tumor-derived p16 alleles encoding proteins defective in cell cycle inhibition. Nature. 1995;375:506–510. doi: 10.1038/375506a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.LaBaer J, Garrett M, Stevenson L, Slingerland J, Sandhu C, Chou H, Fattaey A, Harlow E. New functional activities for the p21 family of CDK inhibitors. Genes Dev. 1997;11:847–862. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.7.847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lammie G, Fantl V, Smith R, Schuuring E, Brookes S, Michalides R, Dickson C, Arnold A, Peters G. D11S287, a putative oncogene on chromosome 11q13, is amplified and expressed in squamous cell and mammary carcinomas and linked to BCL-1. Oncogene. 1991;6:439–444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee M H, Reynisdottir I, Massague J. Cloning of p57KIP2, a cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor with unique domain structure and tissue distribution. Genes Dev. 1995;9:639–649. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.6.639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu Y, Martindale J, Gorospe M, Holbrook N. Regulation of p21WAF1/CIP1 expression through mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway. Cancer Res. 1996;56:31–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lukas J, Bartkova J, Rohde M, Strauss M, Bartek J. Cyclin D1 is dispensable for G1 control in retinoblastoma gene-deficient cells independently of cdk4 activity. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:2600–2611. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.5.2600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lukas J, Parry D, Aagard L, Mann D J, Bartkova J, Strauss M, Peters G, Bartek J. Retinoblastoma-protein-dependent cell-cycle inhibition by the tumor suppressor p16. Nature. 1995;375:503–506. doi: 10.1038/375503a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maelandsmo G, Berner J, Florenes V, Forus A, Hovig E, Fodstad O, Myklebost O. Homozygous deletion frequency and expression levels of the CDKN2 gene in human sarcomas—relationship to amplification and mRNA levels of CDK4 and CCND1. Br J Cancer. 1995;72:393–398. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1995.344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mahony D, Parry D, Lees E. Active cdk6 complexes are predominantly nuclear and represent only a minority of the cdk6 in T cells. Oncogene. 1998;16:603–611. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matsuoka S, Edwards M C, Bai C, Parker S, Zhang P, Baldini A, Harper J W, Elledge S J. p57KIP2, a structurally distinct member of the p21CIP1 Cdk inhibitor family, is a candidate tumor suppressor gene. Genes Dev. 1995;9:650–662. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.6.650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matsushime H, Ewen M E, Strom D K, Kato J-Y, Hanks S K, Roussel M F, Sherr C J. Identification and properties of an atypical catalytic subunit (p34PSK-J3/cdk4) for mammalian D type cyclins. Cell. 1992;71:323–334. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90360-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matsushime H, Quelle D E, Shurtleff S A, Shibuya M, Sherr C J, Kato J-Y. D-type cyclin-dependent kinase activity in mammalian cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:2066–2076. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.3.2066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matsushime H, Roussel M F, Ashmun R A, Sherr C J. Colony-stimulating factor 1 regulates novel cyclins during the G1 phase of the cell cycle. Cell. 1991;65:701–713. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90101-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meyerson M, Harlow E. Identification of G1 kinase activity for cdk6, a novel cyclin D partner. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:2077–2086. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.3.2077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Musgrove E, Swarbrick A, Lee C S, Cornish A L, Sutherland R. Mechanisms of cyclin-dependent kinase inactivation by progestins. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:1812–1825. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.4.1812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Noda A, Ning Y, Venable S F, Pereira-Smith O M, Smith J R. Cloning of senescent cell-derived inhibitors of DNA synthesis using an expression screen. Exp Cell Res. 1994;211:90–98. doi: 10.1006/excr.1994.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Otterson G A, Kratzke R A, Coxon A, Kim Y W, Kaye F J. Absence of p16INK4 protein is restricted to the subset of lung cancer lines that retains wildtype RB. Oncogene. 1994;9:3375–3378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Palmero I, McConnell B, Parry D, Brookes S, Hara E, Bates S, Jat P, Peters G. Accumulation of p16INK4a in mouse fibroblasts as a function of replicative senescence and not of retinoblastoma gene status. Oncogene. 1997;15:495–503. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pardee A. A restriction point for control of normal animal cell proliferation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1974;71:1286–1290. doi: 10.1073/pnas.71.4.1286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Parry D, Bates S, Mann D J, Peters G. Lack of cyclin D-Cdk complexes in Rb-negative cells correlates with high levels of p16INK4/MTS1 tumour suppressor gene product. EMBO J. 1995;14:503–511. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07026.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Parry D, Peters G. Temperature-sensitive mutants of p16CDKN2 associated with familial melanoma. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:3844–3852. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.7.3844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Polyak K, Lee M H, Erdjument B H, Koff A, Roberts J M, Tempst P, Massague J. Cloning of p27Kip1, a cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor and a potential mediator of extracellular antimitogenic signals. Cell. 1994;78:59–66. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90572-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schmidt E E, Ichimura K, Reifenberger G, Collins V P. CDKN2 (p16/MTS1) gene deletion or CDK4 amplification occurs in the majority of glioblastomas. Cancer Res. 1994;54:6321–6324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Serrano M, Hannon G J, Beach D. A new regulatory motif in cell-cycle control causing specific inhibition of cyclin D/CDK4. Nature. 1993;366:704–707. doi: 10.1038/366704a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sewing A, Wiseman B, Lloyd A, Land H. High-intensity Raf signal causes cell cycle arrest mediated by p21Cip1. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:5588–5597. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.9.5588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sherr C J. Cancer cell cycles. Science. 1996;274:1672–1677. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5293.1672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sherr C J. G1 phase progression: cycling on cue. Cell. 1994;79:551–555. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90540-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sherr C J. Mammalian G1 cyclins. Cell. 1993;73:1059–1065. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90636-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stepanova L, Leng X, Parker S B, Harper J W. Mammalian p50cdc37 is a protein kinase-targeting subunit of Hsp90 that binds and stabilizes Cdk4. Genes Dev. 1996;10:1491–1502. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.12.1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Toyoshima H, Hunter T. p27, a novel inhibitor of G1 cyclin-Cdk protein kinase activity, is related to p21. Cell. 1994;78:67–74. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90573-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang J, Guo K, Wills K, Walsh K. Rb functions to inhibit apoptosis during myocyte differentiation. Cancer Res. 1997;57:351–354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wolfel T, Hauer M, Schneider J, Serrano M, Wolfel C, Klehmann-Hieb E, De Plaen E, Hankeln T, Meyer zum Buschenfelde K, Beach D. A p16INK4a-insensitive CDK4 mutant targeted by cytolytic T lymphocytes in a human melanoma. Science. 1995;269:1281–1284. doi: 10.1126/science.7652577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Woods D, Parry D, Cherwinski H, Bosch E, Lees E, McMahon M. Raf-induced proliferation or cell cycle arrest is determined by the level of Raf activity with arrest mediated by p21Cip1. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:5598–5611. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.9.5598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Xiong Y, Hannon G J, Zhang H, Casso D, Kobayashi R, Beach D. p21 is a universal inhibitor of cyclin kinases. Nature. 1993;366:701–704. doi: 10.1038/366701a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Xiong Y, Zhang H, Beach D. D type cyclins associate with multiple protein kinases and the DNA replication and repair factor PCNA. Cell. 1992;71:505–514. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90518-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]