Summary

The International Mouse Phenotyping Consortium reports the generation of new mouse mutant strains for over 5,000 genes, including 2,850 novel null, 2,987 novel conditional- ready, and 4,433 novel reporter alleles.

Despite thirty years of mouse targeted mutagenesis, in vivo function of the majority of genes in the mouse genome are still unknown. This reflects the observation that a small number of genes have been the object of intensive study including the development of multiple mouse models, while a significant proportion of the coding genome remains entirely unexplored 1 The completion of the sequencing of the mouse genome, coupled with the use of mouse embryonic stem (ES) cells for gene targeting to create complex mutant alleles, presented an opportunity to functionally analyze all the protein coding genes of a mammalian species 2,3 Taking advantage of comprehensive manual annotation of the genome 4, the International Knockout Mouse Consortium (IKMC) systematically generated single-gene, reporter-tagged null alleles for protein-coding genes by homologous recombination in mouse ES cells 5,6 Subsequently, large-scale mouse production and phenotyping programs deployed these unique resources, establishing the feasibility of genome-scale mouse production and phenotyping 7–9 Building upon these successes, the International Mouse Phenotyping Consortium (IMPC) was established to coordinate a network of programs around the globe, assuring uniformity and reproducibility of these efforts, including standardization of phenotyping protocols and the use of a single inbred mouse strain background, C57BL/6N, with the ultimate goal of generating and phenotyping a single-gene knockout (KO) mouse line for every protein-coding gene in the genome.

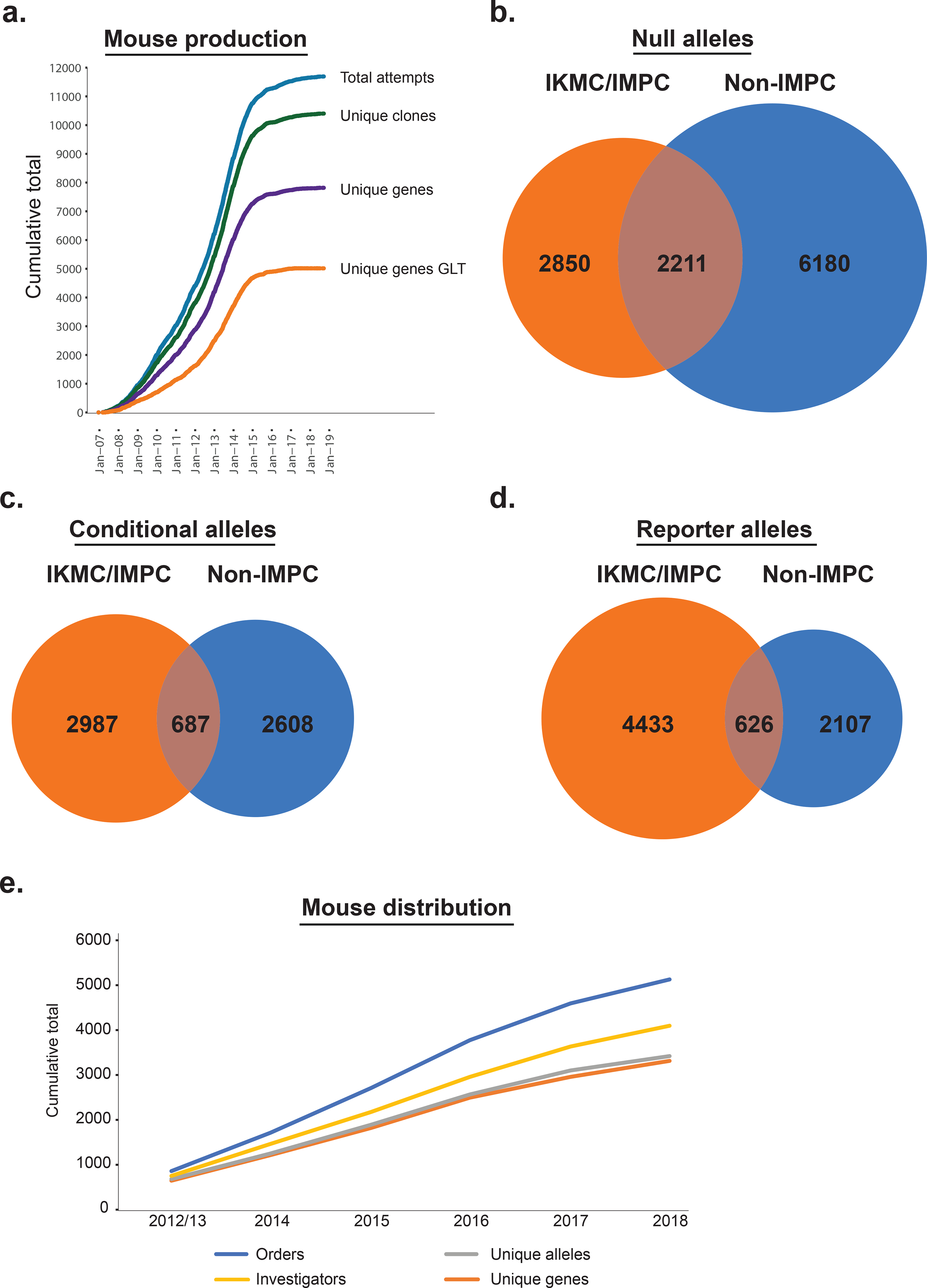

Production of KO mice began in concert with the expansion of the ES cell library, but rapidly accelerated after 2011 with the funding of multiple IMPC programs. To date, more than 17,500 individual production attempts (microinjection or aggregation) have resulted in the germline transmission of KO alleles for 5,061 unique genes (Figure 1a; Supplementary Table 1). These lines have been expanded for phenotyping, providing key insights into mammalian biology and disease 10–15; www.mousephenotype.org). To date, phenotype data for these lines shows that overall 72% of lines display at least one phenotype, revealing extensive pleiotropy (Supplementary Figure 1). This includes the 35.8% of lines that show partial or complete lethality, consistent with our earlier finding 11. The IMPC contribution extends the total number of genes with targeted KO alleles produced by the scientific community from the 8,391 reported and curated by Mouse Genome Informatics (MGI; 16)(Figure 1b; Supplementary Table 1), to 11,241, or more than half of the genome. Much of the overlap (2,211 genes) reflects specific community requests for the production of novel complex alleles (see below), targeting on an inbred C57BL/6N background, or for mutant mouse lines unavailable through public repositories. The growing use of CRISPR/Cas9 editing to produce null alleles for the IMPC led to the decrease in ES cell-based production beginning in 2015.

Figure 1:

Generation and impact of targeted alleles for 5,061 unique mouse genes. (a) Cumulative production progress, including all attempts (microinjection or aggregation (black), unique ES cell clones injected (red), unique genes attempted (yellow), and unique genes that achieved germline transmission (GLT; blue). For GLT, the date reflects the date of microinjection, and only reports the first instance of transmission for the small number of duplicate mutations produced. (b) Venn representation of unique gene null alleles produced by the IMPC (orange) and by the rest of the scientific community as reported in MGI (“Non- IMPC”; blue). (c) Unique gene conditional-ready alleles produced by the IMPC (orange) and by the rest of the scientific community (blue). (d) Unique gene reporter alleles produced by the IMPC (orange) and by the rest of the scientific community (blue). (e) Cumulative mouse orders of IMPC lines processed by production centres and mouse model Repositories from 2012–2018 (blue line). The cumulative number of ordering investigators, unique alleles ordered, and unique genes ordered are shown in yellow, grey, and orange, respectively.

While the primary goal of the IKMC and IMPC was to generate and phenotype a null allele for every protein-coding gene, the mutant alleles included additional functional features. All alleles included a lacZ reporter cassette to facilitate analysis of gene transcription in situ (Supplementary Figure 2; 5,6). A large proportion of the alleles have conditional potential, providing future users with a useful tool for detailed, mechanistic analyses (Supplementary Figure 2a). The multifunctional utility of the alleles produced by the IMPC has greatly expanded the repertoire of genetic resources available to the scientific community. Of the 3,674 unique gene, conditional-ready mouse models generated and validated, 2,987 were novel alleles for genes without an existing conditional allele (81.3%). These nearly double the total number of genes with conditional KO alleles produced by the scientific community as a whole (2,987 IMPC conditional alleles added to the 3,295 conditional alleles reported in MGI as mouse lines; Figure 1c). The impact is even more significant for reporter alleles. The IMPC has produced reporter alleles for 5,059 unique genes, of which 4,433 are novel (87.6%), complementing the 2,733 produced by the scientific community (Figure 1d). This has nearly tripled the total number of genes with reporter alleles available to the community as mouse lines.

The generation of mouse lines was underpinned by comprehensive quality control strategies for both ES cell karyotype and targeted allele, which ensured efficient production and integrity of the targeting event (Supplementary Table 1; Supplementary Figures 3, 4). Further quality control (QC) analysis also showed that part of the ES cell collection contained an additional insertion of a wild-type nonagouti (A) gene on chromosome 8, likely introduced with the targeted reversion event in these cell lines (subclone JM8A317). However, as the insertion of the wild-type nonagouti gene results in an agouti coat color, this allele can be easily segregated from the mutant allele in most cases (Supplementary Figure 5). High- throughput allele validation of ES cells was performed using either a suite of quantitative and endpoint PCR-based tests or a combination of Southern blot18 and PCR-based analysis19, depending on production center (Supplementary Figures 3, 4 and 6; Supplementary Tables 2, 3; Supplementary Note). Despite these efforts, we found that additional quality control (QC) on the mouse lines themselves was required to ensure all IMPC lines resulted from the transmission of the correctly targeted allele (Supplementary Figure 4; 19). This additional QC at the mouse level identified a small but significant proportion of incorrect alleles that transmitted through the germline of chimera mice derived from clones that had passed initial and secondary validation QC testing in the ES cell. Our experience highlights the importance of careful allele validation before and after mouse production.

As a result of this effort, mouse lines with targeted alleles for more than 5,000 genes on a C57BL/6N genetic background with extensive and documented genetic validation of the targeted locus are now available to the biomedical research community, supporting high standards of reproducibility for future investigations. This resource nearly triples the number of genes with reporter alleles and almost doubles the number of conditional alleles available to the scientific community. When combined with more than 30 years of community effort, the total mutant allele mouse resource covers more than half of the genome. The IMPC resource has shown its usefulness through the continued and robust uptake of mutant mouse lines by investigators around the world. This includes both KO and conditional alleles with mouse lines distributed as live mice and cryopreserved stocks. To date, over 5,000 orders for mutant mice for 3,301 unique genes have been processed and shipped to more than 4,000 investigators around the world (Figure 1e). To date, more than 1,900 publications acknowledge the use of EUCOMM/KOMP alleles (for example 20–30). This demonstrates the utility of these resources, the cumulative use of which continues to grow over time, and complements the systematic phenotyping efforts of IMPC centers. In the new era of genome editing, this ES cell-derived collection remains of unique value as it offers particularly sophisticated and quality-controlled alleles representing a cornerstone of the collective development of a null allele resource for the complete mammalian genome 2.

All data are freely available from the IMPC database hosted at EMBL-EBI via a web portal (mousephenotype.org), ftp (ftp://ftp.ebi.ac.uk/pub/databases/impc) and automatic programmatic interfaces. An archived version of the database will be maintained after cessation of funding (exp. 2021) for an additional 5 years. Information on alleles, together with phenotype summaries, are additionally archived with Mouse Genome Informatics at the Jackson Laboratory via direct data submissions (J: 136110, J:148605, J:157064, J:157065, J:188991, J:211773).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank all technical personnel at the different centers involved in this project for their contribution. We thank G. Clarke for support with illustrations. M.-C.B., G.P., M. W.-D., Y.H., and T.S. were supported by the Université de Strasbourg, the CNRS, the INSERM and the programmes ‘Investissements d’avenir’ (ANR-10-IDEX-0002–02, ANR-10-LABX-0030- INRT, ANR-10-INBS-07 PHENOMIN), AY. and M.T. were supported by RIKEN BioResource Research Center (BRC), Management Expenses Grant from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT), D.A, J.B., A.B., W.B., B.D., S.N., R.R.S., B.R., E.R., W.S., K.S. and H.W.-J. were supported by the Wellcome Trust, S.B., S.C., G.C., M.F., S.W. and L.T. were supported by the Medical Research Council (A410), M.G., C.McK. and L.N. were supported by Genome Canada and Ontario Genomics (OGI-051), ), H.L., Y.J.L., G.T.O., and J.K.S. supported by National Research Foundation (2014M3A9D5A01074636, 2014M3A9D5A01075128, 2013M3A9D5072550), Republic of Korea (KMPC), M B., A.B., S B., A.Bu., W.B., F.C., M.F., A.G., M. H. A., R. K., S.N., G.P., R.R.S., B.R., E.R., J.S., W.S., C.S., T.S., G.T.-V, S.W., W.W. and L.T. were supported by the European Commission (EUCOMM (LSHM-CT-2005–018931), EUCOMMTOOLS (FP7- HEALTH-F4–2010-261492), EUMODIC, Infrafrontier 01KX1012 (M.H.A.); EU Horizon 2020: IPAD-MD funding 653961 (M.H.A.)). R.S. and P.K. were supported by RVO 68378050 by Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic and by LM2015040 and LM2018126 (Czech Centre for Phenogenomics), CZ.1.05/2.1.00/19.0395, CZ.1.05/1.1.00/02.0109 funded by the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports and the European Regional Development Fund. Work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China 2018YFA0801100 to Y.X. Research reported in this publication was supported by the NIH Common Fund, the Office of The Director, and the National Human Genomic Research Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Numbers (U42OD011174 supported A.L.B. J.B., A.B., W.B., B.D., M.D., M.F., J. H., M. J., I.L., F.M., S.N., R.R.S., B.R., E.R., W.S., J.S., S.W., and L.T.; U42OD011175 supported M.G., C.McK., L.N., B.W., J.W, K.C.L.; U42OD011185 supported L.R.D., L.G., M.V.W. and S.A.M.; U54HG006370–02 supported A. G-S., R.E.K., A.-M.M., T.M., V.M.F. and L.S.). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors declare no competing interests.

* IMPC Consortium Authors

Juan J Gallegos4, Jennie R Green4, Ritu Bohat4, Katie Zimmel4, Monica Pereira12, Suzanne MacMaster12, Sandra Tondat12, Linda Wei12, Tracy Carroll12, Jorge Cabezas12, Qing Fan-Lan12, Elsa Jacob12, Amie Creighton12, Patricia Castellonos-Penton12, Ozge Danisment12, Shannon Clarke12, Joanna Joeng12, Deborah Kelly12, Christine To12, Rebekah van Bruggen12, Valerie Gailus-Durner15, Helmut Fuchs15, Susan Marschall15, Stefanie Dunst15, Markus Romberger15, Bernhard Rey15, Sabine Fessele42, Philipp Gormanns42, Roland Friedel6, Cornelia Kaloff6, Andreas Hörlein6, Sandy Teichmann6, Adriane Tasdemir6, Heidi Krause6, Dorota German6, Anne Könitzer6, Sarah Weber6, Joachim Beig6, Matthew McKay10, Richard Bedigian10, Stephanie Dion10, Peter Kutny10, Jennifer Kelmenson10, Emily Perry10, Dong Nguyen-Bresinsky10, Audrie Seluke10, Timothy Leach10, Sara Perkins10, Amanda Slater10, Michaela Petit10, Rachel Urban10, Susan Kales10, Michael DaCosta10, Michael McFarland10, Rick Palazola10, Kevin A. Peterson10, Karen Svenson10, Robert E. Braun10, Robert Taft10, Mark Rhue22, Jose Garay22, Dave Clary22, Renee Araiza22, Kristin Grimsrud22, Lynette Bower22, Nicole L Anchell22, Kayla M Jager22, Diana L Young22, Phuong T Dao22, Wendy Gardiner9, Toni Bell9, Janet Kenyon9, Michelle E Stewart9, Denise Lynch9, Jorik Loeffler9, Adam Caulder9, Rosie Hillier9, Mohamed M Quwailid5, Rumana Zaman5, Luis Santos5, Yuichi Obata2, Mizuho Iwama2, Hatsumi Nakata2, Tomomi Hashimoto2, Masayo Kadota2, Hiroshi Masuya2, Nobuhiko Tanaka2, Ikuo Miura2, Ikuko Yamada2, Tamio Furuse2, Mohammed Selloum1, Sylvie Jacquot1, Abdel Ayadi1, Dalila Ali-Hadji1, Philippe Charles1, Elise Le Marchand1, Amal El Amri1, Christelle Kujath1, Jean-Victor Fougerolle1, Peggy Mellul1, Sandrine Legeay1, Laurent Vasseur1, Anne-Isabelle Moro1, Romain Lorentz1, Laurence Schaeffer1, Dominique Dreyer1, Valérie Erbs1, Benjamin Eisenmann1, Giovanni Rossi1, Laurence Luppi1, Annelyse Mertz1, Amélie Jeanblanc1, Evelyn Grau3, Caroline Sinclair3, Ellen Brown3, Helen Kundi3, Alla Madich3, Mike Woods3, Laila Pearson3, Danielle Mayhew3, Nicola Griggs3, Richard Houghton3, James Bussell3, Catherine Ingle3, Sara Valentini3, Diane Gleeson3, Debarati Sethi3, Tanya Bayzetinova3, Jonathan Burvill3, Bishoy Habib3, Lauren Weavers3, Ryea Maswood3, Evelina Miklejewska3, Ross Cook3, Radka Platte3, Stacey Price3, Sapna Vyas3, Adam Collinson3, Matt Hardy3, Priya Dalvi3, Vivek Iyer3, Tony West3, Mark Thomas3, Alejandro Mujica3, Elodie Sins3, Daniel Barrett3, Michael Dobbie43, Anne Grobler44, Glaudina Loots44, Rose Hayeshi44, Liezl-Marie Scholtz44, Cor Bester44, Wihan Pheiffer44, Kobus Venter44, Fatima Bosch45

42 INFRAFRONTIER GmbH

43 Phenomics Australia, John Curtin School of Medical Research, The Australian National University, Acton, Canberra, Australia

44 PCDDP, North-West University, Potchefstroom, South Africa

45 Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona

A full list of members and their affiliations appears in the Supplementary Information.

References

- 1.Stoeger T, Gerlach M, Morimoto RI & Nunes Amaral LA Large-scale investigation of the reasons why potentially important genes are ignored. PLoS Biol 16, e2006643 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Austin CP et al. The knockout mouse project. Nat Genet 36, 921–4 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Auwerx J et al. The European dimension for the mouse genome mutagenesis program. Nat Genet 36, 925–7 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ashurst JL et al. The Vertebrate Genome Annotation (Vega) database. Nucleic Acids Res 33, D459–65 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Skarnes WC et al. A conditional knockout resource for the genome-wide study of mouse gene function. Nature 474, 337–42 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Valenzuela DM et al. High-throughput engineering of the mouse genome coupled with high-resolution expression analysis. Nat Biotechnol 21, 652–9 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Angelis MH et al. Analysis of mammalian gene function through broad-based phenotypic screens across a consortium of mouse clinics. Nat Genet 47, 969–978 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.White JK et al. Genome-wide generation and systematic phenotyping of knockout mice reveals new roles for many genes. Cell 154, 452–64 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.West DB et al. A lacZ reporter gene expression atlas for 313 adult KOMP mutant mouse lines. Genome Res 25, 598–607 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bowl MR et al. A large scale hearing loss screen reveals an extensive unexplored genetic landscape for auditory dysfunction. Nat Commun 8, 886 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dickinson ME et al. High-throughput discovery of novel developmental phenotypes. Nature 537, 508–514 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Karp NA et al. Prevalence of sexual dimorphism in mammalian phenotypic traits. Nat Commun 8, 15475 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meehan TF et al. Disease model discovery from 3,328 gene knockouts by The International Mouse Phenotyping Consortium. Nat Genet 49, 1231–1238 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Munoz-Fuentes V et al. The International Mouse Phenotyping Consortium (IMPC): a functional catalogue of the mammalian genome that informs conservation. Conserv Genet 19, 995–1005 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rozman J et al. Identification of genetic elements in metabolism by high-throughput mouse phenotyping. Nat Commun 9, 288 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bult CJ et al. Mouse Genome Database (MGD) 2019. Nucleic Acids Res 47, D801–D806 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pettitt SJ et al. Agouti C57BL/6N embryonic stem cells for mouse genetic resources. Nat Methods 6, 493–5 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Codner GF et al. Universal Southern blot protocol with cold or radioactive probes for the validation of alleles obtained by homologous recombination. Methods (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ryder E et al. Molecular characterization of mutant mouse strains generated from the EUCOMM/KOMP-CSD ES cell resource. Mamm Genome 24, 286–94 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ingham NJ et al. Mouse screen reveals multiple new genes underlying mouse and human hearing loss. PLoS Biol 17, e3000194 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu X et al. The complex genetics of hypoplastic left heart syndrome. Nat Genet 49, 1152–1159 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miyata H et al. Genome engineering uncovers 54 evolutionarily conserved and testis-enriched genes that are not required for male fertility in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 113, 7704–10 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pol A et al. Mutations in SELENBP1, encoding a novel human methanethiol oxidase, cause extraoral halitosis. Nat Genet 50, 120–129 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Small KS et al. Regulatory variants at KLF14 influence type 2 diabetes risk via a female-specific effect on adipocyte size and body composition. Nat Genet 50, 572–580 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Akawi N et al. Discovery of four recessive developmental disorders using probabilistic genotype and phenotype matching among 4,125 families. Nat Genet 47, 1363–9 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bertero A et al. Activin/nodal signaling and NANOG orchestrate human embryonic stem cell fate decisions by controlling the H3K4me3 chromatin mark. Genes Dev 29, 702–17 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.de la Rosa J et al. A single-copy Sleeping Beauty transposon mutagenesis screen identifies new PTEN-cooperating tumor suppressor genes. Nat Genet 49, 730–741 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim JH et al. Regulation of the catabolic cascade in osteoarthritis by the zinc-ZIP8- MTF1 axis. Cell 156, 730–43 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koch S, Acebron SP, Herbst J, Hatiboglu G & Niehrs C Post-transcriptional Wnt Signaling Governs Epididymal Sperm Maturation. Cell 163, 1225–1236 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kochubey O, Babai N & Schneggenburger R A Synaptotagmin Isoform Switch during the Development of an Identified CNS Synapse. Neuron 90, 984–99 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.