Abstract

The aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) acts as a receptor that responds to ligands, including dioxin. The AhR–ligand complex translocates from the cytoplasm into the nucleus to induce gene expression. Because dioxin exposure impairs cognitive and neurobehavioral functions, AhR-expressing neurons need to be identified for elucidation of the dioxin neurotoxicity mechanism. Immunohistochemistry was performed to detect AhR-expressing neurons in the mouse brain and confirm the specificity of the anti-AhR antibody using Ahr−/− mice. Intracellular distribution of AhR and expression level of AhR-target genes, Cyp1a1, Cyp1b1, and Ahr repressor (Ahrr), were analyzed by immunohistochemistry and quantitative RT-PCR, respectively, using mice exposed to 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD). The mouse brains were shown to harbor AhR in neurons of the locus coeruleus (LC) and island of Calleja major (ICjM) during developmental period in Ahr+/+ mice but not in Ahr−/− mice. A significant increase in nuclear AhR of ICjM neurons but not LC neurons was found in 14-day-old mice compared to 5- and 7-day-old mice. AhR was significantly translocated into the nucleus in LC and ICjM neurons of TCDD-exposed adult mice. Additionally, the expression levels of Cyp1a1, Cyp1b1, and Ahrr genes in the brain, a surrogate of TCDD in the tissue, were significantly increased by dioxin exposure, suggesting that dioxin-activated AhR induces gene expression in LC and ICjM neurons. This histochemical study shows the ligand-induced nuclear translocation of AhR at the single-neuron level in vivo. Thus, the neurotoxicological significance of the dioxin-activated AhR in the LC and ICjM warrants further studies.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00418-021-01990-1.

Keywords: Aryl hydrocarbon receptor, Dioxin, Immunohistochemistry, Island of Calleja major, Locus coeruleus, Mouse

Introduction

The aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR), a ligand-activated transcription factor, exists in a wide range of animal species, including humans and rodents (Hahn 2002). Ligand-bound AhR translocates from the cytoplasm into the nucleus and enhances the expression of AhR-target genes, such as Cyp1a1 and Cyp1b1, whereas these are not activated in Ahr−/− mice (Mimura and Fujii-Kuriyama 2003). To date, evidence has accumulated to indicate the presence of endogenous and exogenous substances that act as AhR ligands (Barroso et al. 2021). An intake of indole-3-carbinol, a dietary AhR ligand, induces expression of Cyp1a1 mRNA in the small intestine of the mouse (Li et al. 2011). Thus, intracellular localization of AhR can be directly linked to its transcriptional function.

Orthologues of the mammalian Ahr gene regulate neuronal growth in Caenorhabditis elegans and Drosophila (Huang et al. 2004; Kim et al. 2006; Qin and Powell-Coffman 2004; Smith et al. 2013). In rodents, Ahr transcripts are detected in various brain regions, including the cerebral cortex, cerebellum, hippocampus, and olfactory bulb (Kimura and Tohyama 2017; Petersen et al. 2000). In particular, Ahr−/− mice show learning and memory impairments possibly due to atypical proliferation and morphology of hippocampal neurons (de la Parra et al. 2018; Latchney et al. 2013), implying that ligand-activated AhR is involved in the regulation of neuronal growth and brain function.

Exposure to dioxin, an exogenous AhR ligand, causes disease conditions, such as cleft palate and hydronephrosis, in Ahr+/+ mice but not Ahr−/− mice (Mimura et al. 1997), showing that AhR is required for induction of dioxin toxicity. Disruption of neuronal migration and neurite elongation is observed in neurons expressing AhR constitutively in the mouse brain (Kimura et al. 2017), suggesting that AhR overactivation impairs neuronal growth and neural circuit structure. Indeed, perinatal dioxin exposure enhances AhR-target gene expression and alters neuromorphology in the mouse brain (Kimura et al. 2016, 2015). Furthermore, dioxin exposure adversely affects a variety of cognitive and neurobehavioral functions in humans (Nishijo et al. 2014; Patandin et al. 1999; Rogan et al. 1988) and rodents (Endo et al. 2012; Haijima et al. 2010; Kakeyama et al. 2014; Kimura et al. 2020; Kimura and Tohyama 2018). These results enabled us to speculate that brain neurons having a greater amount of AhR are strongly associated with dioxin neurotoxicity.

To understand the mechanism of dioxin neurotoxicity, we utilized histological experiments for the identification of AhR-rich neurons and analysis in intracellular AhR dynamics at the single-neuron level. We examined the expression of Ahr transcript and AhR protein in the mouse brain, identified AhR-expressing neurons immunohistochemically, and evaluated the nuclear translocation of AhR in dioxin-exposed mice.

Materials and methods

Animals

The experimental protocols were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Tokyo and that of the National Institute for Environmental Studies. Pregnant female and adult male C57BL/6J mice were purchased from CLEA Japan (Tokyo, Japan). Ahr−/− mice with a B6.129S-Ahr < tm1Yfk > mouse strain (BRC01710) (Mimura et al. 1997) were provided by RIKEN BioResource Research Center (Tsukuba, Japan). Ahr+/− male and female B6.129S-Ahr < tm1Yfk > mice were bred to obtain Ahr−/− progeny. These mice were housed singly and in groups (three per cage), respectively, in an animal facility at a temperature of 22–24 °C and humidity of 40–60% on a 12:12-h light/dark cycle (lights on from 08:00 to 20:00). Laboratory rodent chow (Lab MR Stock; Nosan, Yokohama, Japan) and distilled water were provided ad libitum. Offspring were selected for transcript and protein expression analyses as described in sections of RT-PCR, western blotting, quantitative RT-PCR, and immunohistochemistry below. The number of animals used for these analyses is described in the legends to figures.

To produce and maintain the Ahr−/− mouse strain, genotyping of the Ahr gene was performed as follows: genomic DNA was extracted from tail tips by lysis in 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.0), 100 mM NaCl, 20 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), 1% sodium dodecyl sulphate, and proteinase K (Wako Pure Chemicals, Osaka, Japan) at 55 °C for 4 h. The lysate was centrifuged at 17,400×g at 4 °C for 3 min. The genomic DNA in the supernatant was purified using phenol and chloroform, followed by washing with 70% ethanol. The genomic DNA (dissolved in Tris–EDTA buffer) was used as the template for PCR using the Takara LA Taq PCR kit (Takara Bio, Kusatsu, Japan) on a Veriti thermal cycler (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). The amplification conditions were as follows: 94 °C for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 55 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 35 s. The PCR primers to amplify the genomic Ahr locus were 5′-GCCCGAGTCTCCTCTGTCG-3′/5′-CTCACGGCAGCGGAGATCT-3′ for the wild-type Ahr allele and 5′-GCCCGAGTCTCCTCTGTCG-3′/5′-CGCCGAGTTAACGCCATCAA-3′ for the Ahr-null allele. The 25-μl reaction contained 400 nM of each primer, 1× GC buffer II, 320 μM deoxynucleoside triphosphate (dNTP) mixture, and 0.5 U of LA Taq DNA polymerase. PCR products were separated by electrophoresis on agarose gels, which were stained with Midori Green Advance (Nippon Gene, Tokyo, Japan). The PCR products of the wild-type Ahr allele and Ahr-null allele were expected to be 439 and 671 bp in size, respectively.

RT-PCR

Developing mice at P3 and P5 were decapitated, and several organs, including the brain, liver, lung, kidney, thymus, and spleen, were quickly removed and stored at −80 °C until RT-PCR analysis. The total RNA was isolated from each organ using an RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Tokyo, Japan). The cDNA for a given mRNA was synthesized using oligo-dT and random hexamers with a Primescript RT reagent kit (Takara Bio). Expression levels of Ahr and Gapdh transcripts were determined using a Veriti thermal cycler (Applied Biosystems) with a KOD Plus kit (Toyobo, Osaka, Japan). The amplification conditions were as follows: 95 °C for 1 min, followed by 35 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s, 55 °C for 15 s, and 68 °C for 30 s. The PCR primers for amplifying the murine Ahr and Gapdh transcripts were 5′-AGGATTTGCAAGAAGGAGAG-3′/5´-TTGGTTCGAATTTCCAGGAT-3´ and 5′-ACCCAGAAGACTGTGGATGG-3′/5′-CACATTGGGGGTAGGAACAC-3′, respectively. The 20-μl reaction solution contained 400 nM of each primer, 1× KOD Plus buffer, 200 μM dNTP mixture, 1 mM MgSO4, and 0.5 U of KOD Plus DNA polymerase. PCR products were separated by electrophoresis on agarose gels, which were stained with Midori Green Advance (Nippon Gene). The PCR products of the Ahr and Gapdh transcripts were expected to be 508 and 171 bp in size, respectively.

Western blotting

Developing mice at P3, P5, and P14 were decapitated, and several organs (brain, liver, lung, kidney, thymus, and spleen) were quickly collected and stored at −80 °C until western blotting analysis. Protein was extracted at 4 °C in an ice bath unless stated otherwise. Each type of organ was homogenized with 4 mM HEPES–NaOH buffer, pH 7.3, containing 0.32 M sucrose and 1% protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), using a Potter-type homogenizer. The homogenates were centrifuged at 1000×g at 4 °C for 10 min, and the supernatants were used for western blotting. Protein concentration in the supernatants was measured with the Quick Start Bradford Protein Assay (BioRad, Hercules, CA, USA). Proteins in the supernatants were separated on a 7.5% polyacrylamide gel and blotted onto immobilon-P transfer membranes (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA). The proteins adsorbed to membranes were allowed to react with mouse monoclonal anti-AhR antibody (1:1000; sc-398877, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) in Tris-buffered saline, pH 7.4, containing 0.1% Tween-20 (TBST), overnight at 4 °C, followed by incubation in TBST containing anti-mouse IgG-horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated antibody (1:5000; 7076S, Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA, USA), for 1 h at room temperature. Chemi-Lumi One (Nacalai Tesque, Kyoto, Japan) was used to visualize the protein bands, which were detected on Hyperfilm ECL (GE Healthcare Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) and developed and fixed with GBX developer and GBX fixer (Kodak, Rochester, NY, USA), respectively. Following deactivation of endogenous HRP by incubation in TBST containing 15% hydrogen peroxide for 30 min at room temperature, the membranes were immersed in TBST containing rabbit polyclonal anti-GAPDH antibody (1:5000; ab9485, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), overnight at 4 °C, followed by incubation in TBST containing anti-rabbit IgG-HRP-conjugated antibody (1:5000; 7074S, Cell Signaling Technology). Then, targeted protein bands were visualized in the same manner as described for AhR detection. The intensity of AhR and GAPDH bands was measured using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA).

Chemical treatment

2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD; purity > 99.5%) was purchased from Cambridge Isotope Laboratory (Andover, MA, USA). Corn oil and n-nonane were purchased from Wako Pure Chemicals and Nacalai Tesque, respectively. Twelve-week-old male C57BL/6J mice were divided to control and TCDD groups, and they were orally administered with vehicle (corn oil containing 0.6% n-nonane) or TCDD dissolved in vehicle (20 μg/kg body weight).

Quantitative RT-PCR

Brain and liver tissues of 12-week-old male mice treated with vehicle or TCDD were collected quickly and stored at −80 °C until analysis. Total RNA was isolated from the brain and liver using an RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen). The cDNA for a given mRNA was synthesized using oligo-dT and random hexamer primers with a PrimeScript RT reagent kit (Takara). Gene expression levels were determined quantitatively using a LightCycler System (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Indianapolis, IN, USA) with Thunderbird SYBR qPCR Mix (Toyobo). The genes and primers are summarized in Supplementary Table 1. No-template reactions were analyzed in every PCR to monitor for cross-contamination. To verify the specificity of amplification, melting curve analyses of the products were performed at the end of every PCR. The Cyp1a1, Cyp1b1, and Ahr repressor (Ahrr) mRNA expression levels were calculated using the ΔΔCt method and normalized to the 18S rRNA expression.

Immunohistochemistry

Developing and adult mice were transcardially perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) under anesthesia with sodium pentobarbital (conducted at the University of Tokyo) or three types of mixed anesthetic agents containing medetomidine hydrochloride, midazolam, and butorphanol (at the National Institute for Environmental Studies). Brains were collected, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight, immersed in a series of 0.1 M PBS containing 5%, 15%, and 30% sucrose, frozen in Tissue-Tek O.C.T. compound (Sakura Finetek, Tokyo, Japan), and stored at −80 °C until histological sectioning. Frozen brains were sliced in the sagittal plane using a cryostat (Model 3050S; Leica Microsystems, Tokyo, Japan). Brain sections were cut at 50 μm thickness for immunofluorescence analysis.

Brain tissue sections were immunohistochemically stained for AhR, tyrosine hydroxylase (TH), dopamine β-hydroxylase (DBH), or NeuN. In brief, the tissue sections were washed in PBS containing 0.1% Triton X-100 (PBST), soaked in 0.01 M citrate buffer (pH 6.0) (Muto Pure Chemicals, Tokyo, Japan), and incubated at 90 °C (developing mouse brains) or 65 °C (adult mouse brains) in a water bath for 10 min. The sections were blocked with PBST containing 5% bovine serum albumin (A3059; Sigma-Aldrich) (blocking solution) and allowed to react with mouse monoclonal anti-AhR antibody (1:500; sc-398877, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and rabbit polyclonal anti-TH antibody (1:1000; ab112, Abcam), anti-DBH antibody (1:1000; 22,806, Immunostar, Hudson, WI, USA), or anti-NeuN (1:1000; ab177487, Abcam) in blocking solution overnight at 4 °C. Then, the signals of AhR and TH, DBH, or NeuN were visualized with the respective secondary antibodies anti-mouse IgG AlexaFluor 488 (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) and anti-rabbit IgG AlexaFluor 568 (Life Technologies) in PBST (1:1000). Furthermore, the nucleus was stained with PBST containing Hoechst 33342 (1:1000; Dojin Laboratories, Kumamoto, Japan), followed by mounting with VECTASHIELD (H-1400; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) for confocal microscopy. Immunostained images were captured using an inverted Leica DMi8 microscope, equipped with the Leica TCS SP8 confocal module (Leica Microsystems). Specific objective lens (HC PL APO CS 10×/NA = 0.40 and HC PL APO CS2 20×/NA = 0.75; Leica Microsystems) and LAS X 3.1.5 software (Leica Microsystems) were used to capture images (x = 2048 pixels and y = 2048 pixels, bit depth = 8 in each RGB color).

Intracellular localization of AhR

Cellular morphology and immunostaining intensity of AhR- and TH-double-positive cells in the locus coeruleus (LC) and AhR- and NeuN-double-positive cells in the island of Calleja major (ICjM) were analyzed by applying the ImageJ software to the confocal microscopy images. In analyses of AhR- and TH-double-positive cells in the LC, we outlined the nucleus and soma of TH-positive cells [i.e., noradrenergic (NA) neurons] and measured their nuclear and soma sectional areas, and then calculated the nuclear area percentage by dividing the nuclear area by the soma area in each cell. In addition, we determined AhR immunostaining intensity per nucleus and soma (AhRNuc intensity and AhRSoma intensity, respectively) of TH-positive cells. After the background subtraction of AhR-stained images, the AhRNuc intensity percentage was calculated by dividing the AhRNuc intensity by the AhRSoma intensity. In order to analyze the intracellular localization of AhR, AhRNuc intensity percentage data were normalized depending on the soma size of TH-positive cells. We divided the AhRNuc intensity percentage by the nuclear area percentage to calculate the ratio in locus coeruleus-noradrenergic (LC-NA) neurons (ratioLC−NA, thereafter). In order to compare ratioLC−NA of individual mice between the control and TCDD groups, we used the distribution of ratioLC−NA values in each mouse as a surrogate parameter and analyzed the percentage of ratioLC−NA that was divided by the arbitrarily chosen value of 0.2. For each mouse, 57 to 103 cells in developing mice and 51 to 96 cells in adult mice were subjected to analyses in intracellular localization of AhR in TH-positive cells in the LC. In analyses of AhR- and NeuN- double-positive cells in the ICjM, we outlined the nucleus of NeuN-positive cells and measured nuclear sectional areas and AhRNuc intensity in each cell. To adjust the variability of luminance among images, AhRNuc intensity was normalized to the mean value of immunostained AhR intensity in the whole ICjM area. The parameter ratio in ICjM neurons (ratioICjM, thereafter) was calculated by dividing AhRNuc intensity by the nuclear area in each cell. Furthermore, we analyzed the percentage of the ratioICjM that was divided by the arbitrarily chosen value of 0.005. The numbers of cells that were used to analyze the intracellular localization of AhR in NeuN-positive cells in the ICjM ranged from 65 to 263 cells in developing mice and from 133 to 291 cells in adult mice.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using BellCurve for Excel software (Social Survey Research Information Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). Protein expression, cellular morphology, immunostaining intensity, and ratio values were analyzed using Student’s t-test or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by the Tukey–Kramer post hoc test, and p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Because the mention of F- and p-values for each statistical analysis in the main text is very complicated, statistically significant differences are shown by asterisks in each figure.

Results

AhR expression in developing organs

In developing mice, AhR was observed in various organs, including the brain, by RT-PCR and western blotting, although AhR protein amounts in the brain were significantly lower than those in other organs (Fig. 1a–c). No significant difference in expression was found between male and female brains (Fig. 1d, e). The AhR protein was not detected in Ahr−/− mice (Fig. 1f), indicating the specificity of the anti-AhR antibody.

Fig. 1.

Ahr transcript and AhR protein expression in developing mouse organs. a RT-PCR–amplified Ahr (508 bp) and Gapdh (171 bp) transcripts were detected in the brain, liver, lung, kidney, thymus, and spleen of mice at P3 and P5 (n = 4 mice at each stage). NC negative control. b Representative images showing AhR and GAPDH proteins detected by western blotting in the brain, liver, lung, kidney, thymus, and spleen of male mice at P3. c Quantitative analysis of AhR band intensity in six organs (n = 8 mice/tissue). d Images showing AhR and GAPDH proteins detected by western blotting in the brains of male and female mice at P5. e Quantitative analysis of AhR band intensity in male and female mouse brains (n = 4 mice/group) at P5, showing no significant difference in AhR protein amounts between sexes. AhR band intensity was normalized to GAPDH band intensity. f Images showing AhR and GAPDH proteins detected by western blotting in the brain, liver, and lung of Ahr+/+ and Ahr−/− mice at P5 (n = 1 in each genotype). No AhR protein was detected in these tissues of Ahr−/− mice, demonstrating the specificity of the antibody. Circles represent individual mouse data. Values are shown as the mean ± SD. Asterisks (** and ***) denote statistical significance at p < 0.01 and 0.001, respectively, by one-way ANOVA with the Tukey–Kramer post hoc test

AhR localization in neurons of the developing brain

Distinct AhR immunostaining was observed in the LC, where AhR was detected in nearly all the NA neurons expressing TH or DBH in Ahr+/+ mice at P5, P7, and P14, whereas no AhR was detected in Ahr−/− mice (Fig. 2a–d and Supplementary Table 2). Because the nuclear and soma areas of LC-NA neurons increased differently between P5 and P14 (Fig. 3a–c), two indexes were used for a normalization purpose: the percentage of nuclear area to soma area and the percentage of AhRNuc intensity to AhRSoma intensity. The nuclear area percentage decreased significantly with age (P5, P7, and P14; Fig. 3d). Despite a significantly higher AhRNuc intensity at P5 than P7 and P14 (Fig. 3e), no significant difference was found in the normalized ratio of AhRNuc intensity percentage to nuclear area percentage (ratioLC−NA) during development (Fig. 3f).

Fig. 2.

AhR expression in mouse LC-NA neurons at P5, P7, and P14. a Diagram displaying the location of the LC (left) and the metabolic pathway of noradrenaline synthesis in LC-NA neurons (right). b, c Brain tissue sections immunostained with anti-TH or DBH and anti-AhR antibodies. AhR was detected in TH-expressing neurons in the LC at P5, P7, and P14 (n = 3 mice at each stage) (b). Additionally, AhR was also found in neurons expressing DBH in the LC at P14 (n = 3 mice) (c). Scale bar = 100 μm. d Representative images showing the LC of Ahr+/+ and Ahr−/− mice at P14 (n = 3 mice in each genotype), demonstrating antibody specificity. Arrowheads mark TH-negative cells with nonspecific anti-AhR antibody staining. Scale bar = 100 μm

Fig. 3.

Intracellular localization of AhR in mouse LC-NA neurons at P5, P7, and P14. a Immunostained LC-NA neurons double-positive for TH and AhR. The cellular boundary of TH-stained cells was clearly observed, which enabled the measurement of the nuclear and soma areas of individual LC-NA neurons. Scale bar = 10 μm. b–f Quantitative analyses of AhR-expressing LC-NA neurons. The nuclear area was significantly larger at P5 than at P7 and P14 (b), whereas the soma area was significantly larger at P14 compared to P5 and P7 (c), indicating that marked changes in cellular morphology occur between P5 and P14. The nuclear area percentage that represents the nuclear area normalized to the soma area in each neuron was significantly decreased during the period from P5 to P14 (d). The AhR immunostaining intensity per nucleus (AhRNuc intensity) was normalized to that of the soma in each neuron (AhRNuc intensity percentage). The AhRNuc intensity percentage at P5 was significantly higher than that at P7 and P14 (e). To normalize the developmental-stage-related changes in cellular morphology, the ratio calculated by dividing AhRNuc intensity percentage by nuclear area percentage (ratioLC−NA) served as an index to evaluate the nuclear AhR. No significant difference in ratioLC−NA was found across developmental periods (f). Values are shown as the mean ± SD. Circles represent individual cell data (215, 228, and 200 cells from 3 mice each at P5, P7, and P14, respectively). Asterisks (** and ***) denote statistical significance at p < 0.01 and 0.001, respectively, by one-way ANOVA with the Tukey–Kramer post hoc test

We also found AhR in cells expressing NeuN, a neuronal marker, in the ICjM of Ahr+/+ mice, but not in Ahr−/− mice (Fig. 4a–c). The boundary of the soma area of ICjM neurons was not traceable because they are densely located (Fig. 5a). Thus, using the nuclear area, we normalized the AhRNuc intensity to get an index (ratioICjM). The AhRNuc intensity was found to vary at the three different ages, and the ratioICjM was significantly higher at P14 than at P5 and P7 (Fig. 5b–d).

Fig. 4.

AhR expression in mouse ICjM neurons at P5, P7, and P14. a Diagram (left) illustrating the location of the ICjM anterior to the commissural fiber (cf). A representative low-magnification image (right) of Hoechst-stained brain tissue at P5 is shown. Scale bar = 200 μm. b Representative images of immunostained sections of the ICjM at P5, P7, and P14 show distinct AhR signals in cells expressing NeuN, a marker of mature neurons (n = 3 mice at each stage). Scale bar = 100 μm. c Representative images showing the ICjM of Ahr+/+ and Ahr−/− mice at P14 (n = 3 mice in each genotype). Immunostained AhR signals were not observed in Ahr−/− mice, demonstrating the specificity of the antibody. Scale bar = 100 μm

Fig. 5.

Intracellular localization of AhR in mouse ICjM neurons at P5, P7, and P14. a Immunostained ICjM neurons double-positive for NeuN and AhR. Because the cellular boundary could not be distinctly visualized, the soma areas of each neuron were not characterized. Scale bar = 10 μm. b–d Quantitative analyses of AhR-expressing ICjM neurons. The nuclear area of each neuron gradually increased with brain development (b). The AhR immunostaining intensity per nucleus (AhRNuc intensity) was significantly increased during the period from P5 to P14 (c). The ratioICjM representing AhRNuc intensity normalized to the nuclear area was significantly higher at P14 than those at P5 and P7, and no significant difference was observed between P5 and P7 (d). Values are shown as the mean ± SD. Circles represent individual cell data (711, 528, and 332 cells from 3 mice at each stage, P5, P7, and P14, respectively). Asterisks (***) denote statistical significance at p < 0.001 by one-way ANOVA with the Tukey–Kramer post hoc test

To study AhR dynamics in other brain regions, we analyzed the AhR expression in the cerebral cortex, cerebellum, hippocampus, and olfactory bulb at P14. Although AhR in these regions was observed by western blotting, distinct immunohistochemical signals were not detected (Supplementary Fig. 1a–c).

Nuclear translocation of AhR in dioxin-exposed mice

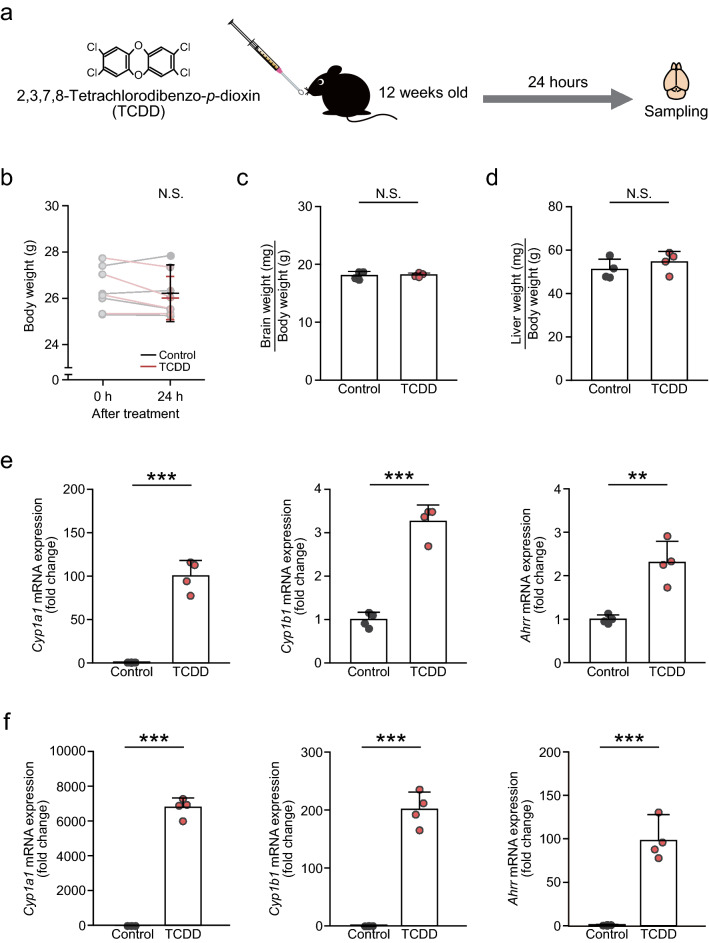

We studied whether dioxin altered the intracellular localization of AhR in LC-NA and ICjM neurons. Adult mice treated with TCDD, the most toxic dioxin congener (Van den Berg et al. 2006), did not show any signs of weight loss (Fig. 6a–d). In the TCDD group, the expression levels of the AhR-target genes Cyp1a1, Cyp1b1, and Ahrr were significantly increased in the brain and liver (Fig. 6e, f), indicating nuclear translocation of AhR upon dioxin exposure.

Fig. 6.

Expression level of AhR-target genes in the brain and liver of TCDD-exposed mice. a Schematic of the TCDD experiment. Twelve-week-old mice were orally exposed to TCDD (20 μg/kg body weight), and their brains and livers were sampled 24 h later. The liver was used as a positive control to confirm increased expression of the AhR-target genes Cyp1a1, Cyp1b1, and Ahrr, which are drastically enhanced by TCDD exposure. b–d Body weight b and organ size of the brain c and liver d in the control and TCDD groups. Upon TCDD exposure, no changes in these weights were observed between the two groups. e, f Expression levels of Cyp1a1, Cyp1b1, and Ahrr mRNAs in the brain e and liver f. In the TCDD group, the expression of the three AhR-target genes in the brain and liver was significantly increased. Circles represent individual mouse data (n = 4 mice/group). Values are shown as the mean ± SD. Asterisks (** and ***) denote statistical significance at p < 0.01 and 0.001, respectively, by Student’s t-test

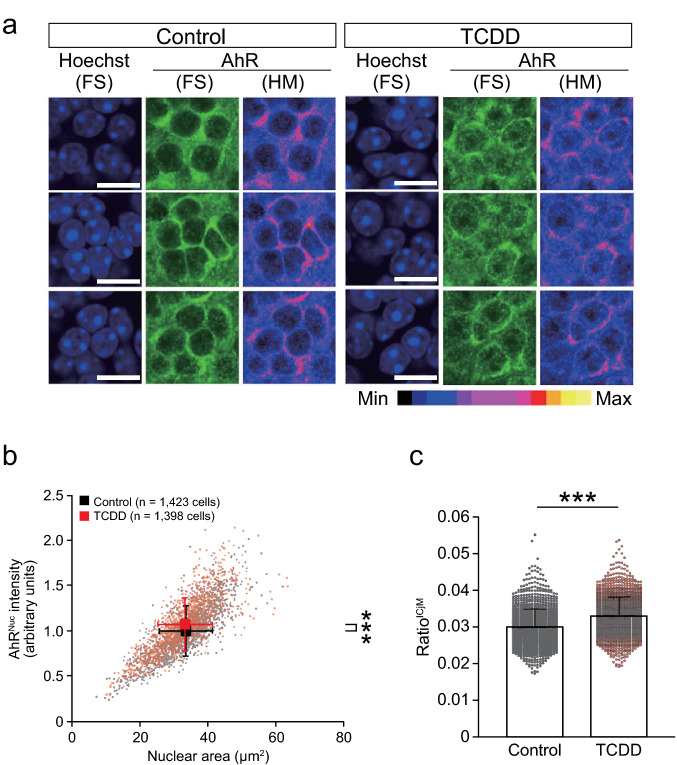

We observed no significant difference in the nuclear area of LC-NA neurons between the control and TCDD groups (Fig. 7a and Supplementary Fig. 2a, b). Although the soma area in the TCDD group was significantly higher than that in the control group (Supplementary Fig. 2c), the normalized nuclear area percentage did not differ (Fig. 7b), suggesting the minimized toxicity, if any, at the cellular level. The AhRNuc intensity percentage and ratioLC−NA were significantly increased in the TCDD group (Fig. 7b, c). To examine the effects of TCDD exposure on individual mice, we also compared the two groups regarding the distribution of ratioLC−NA values in each mouse and found that they were significantly shifted toward higher values in the TCDD group compared to control (Supplementary Fig. 2d). In ICjM neurons, both AhRNuc intensity and ratioICjM in the TCDD group were significantly higher than those in the control group without a significant change in the nuclear area (Fig. 8a–c and Supplementary Fig. 3a). The distribution of ratioICjM values in individual mice was right-shifted toward higher values in the TCDD group compared to control (Supplementary Fig. 3b). These histological analyses showed the translocation of AhR from the cytoplasm into the nucleus in the LC-NA and ICjM neurons of TCDD-exposed mice.

Fig. 7.

Nuclear translocation of AhR in LC-NA neurons of TCDD-exposed mice. a Representative images showing fluorescent signal (FS) of TH and AhR in LC-NA neurons in the control and TCDD groups. Heatmap (HM) images represent the relative intensity of immunostained AhR signals. The fluorescent intensity scale for HM images is shown below the images. Scale bar = 10 μm. b Scatter plot of nuclear area percentage (x-axis) and AhRNuc intensity percentages (y-axis) in LC-NA neurons in the control (black) and TCDD (red) groups. The AhRNuc intensity percentage of the TCDD group was significantly higher than that of the control group without a significant change in the nuclear area percentage. c The ratioLC−NA was significantly higher in the TCDD group than in the control group. Values are shown as the mean ± SD. Circles represent individual cell data (382 and 398 cells from 6 mice each in the control and TCDD groups, respectively). Asterisks (***) denote statistical significance at p < 0.001 by Student’s t-test

Fig. 8.

Nuclear translocation of AhR in ICjM neurons of TCDD-exposed mice. a Representative images showing fluorescent signal (FS) of Hoechst and AhR in ICjM neurons in the control and TCDD groups. Heatmap (HM) images represent the relative intensity of immunostained AhR signals. The fluorescent intensity scale for HM images is shown below the images. Scale bar = 10 μm. b Scatter plot of nuclear area (x-axis) and AhRNuc intensity (y-axis) in ICjM neurons in the control (black) and TCDD (red) groups. The AhRNuc intensity of the TCDD group was significantly higher than that of the control group without a significant change in the nuclear area. c The ratioICjM was significantly higher in the TCDD group than in the control group. Values are shown as the mean ± SD. Circles represent individual cell data (1423 and 1398 cells from six mice each in the control and TCDD groups, respectively). Asterisks (***) denote statistical significance at p < 0.001 by Student’s t-test

Discussion

The AhR–ligand complex translocates into the cellular nucleus to enhance the expression of AhR-target genes, which in turn may induce developmental and physiological responses or toxicities. Thus, the types of brain neurons expressing AhR must be characterized for understanding the impacts of AhR ligands on the nervous system. In the present study, we immunohistochemically identified two neuronal populations having AhR in the mouse LC and ICjM and quantitatively analyzed nuclear translocation of AhR at the single-neuron level. Although AhR expression in neurons and glias has been reported in humans and rodents (Bravo-Ferrer et al. 2019; de la Parra et al. 2018; Rothhammer et al. 2018, 2016; Shackleford et al. 2018), the specificity of the AhR antibodies in these studies has not been verified by immunohistochemistry using AhR-null tissues. After confirming the specificity of the AhR antibody using Ahr−/− mouse brains, we unequivocally demonstrated the presence of AhR in LC-NA and ICjM neurons (Figs. 2d, 4c). Furthermore, a significant increase in nuclear AhR was found in these neurons of TCDD-exposed mice (Figs. 7, 8 and Supplementary Figs. 2, 3), which is consistent with gene expression changes (Fig. 6e). Thus, our immunohistochemical analysis is considered to be robust. We describe three implications of the presence of neuronal AhR in the LC and ICjM below.

First, loss-of-function and gain-of-function experiments reveal that AhR regulates neurogenesis, neuronal migration, and neurite elongation in C. elegans (Huang et al. 2004; Qin and Powell-Coffman 2004; Smith et al. 2013), Drosophila (Kim et al. 2006), and mice (de la Parra et al. 2018; Kimura et al. 2017; Latchney et al. 2013). Thus, it is plausible that AhR is involved in the growth of LC-NA and ICjM neurons. Although it has been reported that neurogenesis of ICjM occurs in rat fetuses (Bayer 1985) and that ICjM structure is formed in mice at P2 (Hsieh and Puche 2013), the molecular mechanisms regulating the growth of ICjM neurons remain largely unclear. Since, in the present study, altered AhR dynamics was found in the nuclei of ICjM neurons during development (Fig. 5), further studies on the role of AhR in ICjM neurons could help understand the mechanism of the ICjM formation. On the other hand, no distinct AhR immunostaining was observed in the cerebral cortex, cerebellum, hippocampus, and olfactory bulb, where AhR protein was detected by western blotting (Supplementary Fig. 1). One plausible explanation would be that AhR abundance in LC-NA and ICjM neurons is greater than that in other neurons, suggesting the possibility of AhR as a marker for specified neuronal populations.

Second, the intracellular dynamics of AhR is essential for understanding how AhR ligands impact cellular activities. AhR ligands contained in diet and gut microbiota metabolites have been reported to regulate various physiological systems. Treatment with indole-3-carbinol enhances the immune capacity of Ahr+/+ mice but not Ahr−/− mice (Kiss et al. 2011; Li et al. 2011). Furthermore, indole-3-aldehyde produced by lactobacilli has AhR agonistic activity and protects against candidiasis and colitis in an AhR-dependent manner (Zelante et al. 2013). In particular, a large body of evidence suggests that gut microbiota influences neuronal activities and brain functions (Mayer et al. 2015). However, the molecular mechanisms linking gut microbiota with brain neurons are not fully understood, although several pathways via which microbiota affect brain function have been proposed (Cryan and Dinan 2012). Our present study provides experimental evidence that oral exposure to TCDD significantly increases nuclear translocation of AhR in LC-NA and ICjM neurons (Figs. 7, 8 and Supplementary Figs. 2, 3), suggesting that other AhR ligands might also influence the AhR dynamics and signaling activation in these neurons.

Third, cognitive impairments and neurobehavioral abnormalities have been reported in humans and laboratory animals perinatally exposed to dioxin (Endo et al. 2012; Haijima et al. 2010; Kakeyama et al. 2014; Kimura et al. 2020; Kimura and Tohyama 2018; Nishijo et al. 2014; Patandin et al. 1999; Rogan et al. 1988). However, the brain regions and neuronal populations responsible for those neurotoxic effects remain still uncharacterized. Our immunohistochemical analysis demonstrated that LC-NA and ICjM neurons are targets of dioxin (Figs. 7, 8 and Supplementary Figs. 2, 3). LC-NA neurons elongate their axons into a wide range of brain regions and regulate a variety of brain functions (Waterhouse and Navarra 2019). For example, in rodents, the LC is involved in sleep/awake states (Aston-Jones and Bloom 1981), stress response (Ziegler et al. 1999), behavioral flexibility (McGaughy et al. 2008), fear memory (Soya et al. 2013), and everyday memory (Takeuchi et al. 2016) as well as infant attachment learning (Moriceau et al. 2009). Remarkably, mouse offspring born to dams exposed to TCDD show abnormalities related to attachment behavior in infancy (Kimura and Tohyama 2018) and executive function and emotion in adulthood (Endo et al. 2012; Haijima et al. 2010), suggesting that these phenotypes could be caused by impaired growth of LC-NA neurons. Additionally, a change in the number of midbrain dopaminergic neurons in TCDD-exposed mice (Tanida et al. 2009) has been reported. ICjM neurons receive axonal projections from midbrain dopaminergic neurons (Fallon et al. 1978) and express dopamine receptors (Mengod et al. 1991; Sokoloff et al. 1990). The dopaminergic circuit plays a role in reward-related behavior (Ikemoto 2007), and rats afflicted with drug addiction show an increase in ICjM neuronal activity (Prast et al. 2014; Singh et al. 2006), suggesting an involvement of the ICjM in reward-related behavior. Thus, it is plausible that dioxin adversely affects the growth of both ICjM and dopaminergic neurons, leading to an abnormality in reward-related behavior. Collectively, our histological results highlight the need for studies focusing on LC-NA and ICjM neurons to understand the molecular mechanisms of dioxin neurotoxicity.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Ms. Kayoko Taki and Dr. Shin Yamazaki at the National Institute for Environmental Studies for their excellent technical assistance and useful comments on statistics, respectively. The B6.129S-Ahr <tm1Yfk> mouse strain (BRC01710) was provided by RIKEN BRC through the National BioResource Project of the MEXT/AMED, Japan. We would like to thank Editage for English language editing.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: E.K. and C.T.; investigation: E.K., M.K., and F.M.; methodology: E.K. and M.K.; funding acquisition: E.K., F.M., and C.T.; resources: Y.F.-K.; supervision: C.T.; writing – original draft: E.K. and C.T.

Funding

This work was supported in part by grants from the JSPS Kakenhi (17K12826 to E.K., 19H01152 to F.M., and JP24221003 to C.T.).

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Ethical approval

All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with the experimental protocols approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Tokyo and that of the National Institute for Environmental Studies.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

6/18/2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1007/s00418-021-01997-8

Contributor Information

Eiki Kimura, Email: eiki-kimura@umin.ac.jp.

Chiharu Tohyama, Email: tohyama.chiharu@hestic.com.

References

- Aston-Jones G, Bloom FE. Activity of norepinephrine-containing locus coeruleus neurons in behaving rats anticipates fluctuations in the sleep-waking cycle. J Neurosci. 1981;1(8):876–886. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.01-08-00876.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barroso A, Mahler JV, Fonseca-Castro PH, Quintana FJ. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor and the gut-brain axis. Cell Mol Immunol. 2021;18(2):259–268. doi: 10.1038/s41423-020-00585-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayer SA. Neurogenesis in the olfactory tubercle and islands of Calleja in the rat. Int J Dev Neurosci. 1985;3(2):135–147. doi: 10.1016/0736-5748(85)90004-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bravo-Ferrer I, Cuartero MI, Medina V, Ahedo-Quero D, Pena-Martinez C, Perez-Ruiz A, Fernandez-Valle ME, Hernandez-Sanchez C, Fernandez-Salguero PM, Lizasoain I, Moro MA. Lack of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor accelerates aging in mice. FASEB J. 2019;33(11):12644–12654. doi: 10.1096/fj.201901333R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cryan JF, Dinan TG. Mind-altering microorganisms: the impact of the gut microbiota on brain and behaviour. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012;13(10):701–712. doi: 10.1038/nrn3346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Parra J, Cuartero MI, Perez-Ruiz A, Garcia-Culebras A, Martin R, Sanchez-Prieto J, Garcia-Segura JM, Lizasoain I, Moro MA (2018) AhR deletion promotes aberrant morphogenesis and synaptic activity of adult-generated granule neurons and impairs hippocampus-dependent memory. eNeuro 5(4). 10.1523/ENEURO.0370-17.2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Endo T, Kakeyama M, Uemura Y, Haijima A, Okuno H, Bito H, Tohyama C. Executive function deficits and social-behavioral abnormality in mice exposed to a low dose of dioxin in utero and via lactation. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(12):e50741. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallon JH, Riley JN, Sipe JC, Moore RY. The islands of Calleja: organization and connections. J Comp Neurol. 1978;181(2):375–395. doi: 10.1002/cne.901810209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn ME. Aryl hydrocarbon receptors: diversity and evolution. Chem Biol Interact. 2002;141(1–2):131–160. doi: 10.1016/S0009-2797(02)00070-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haijima A, Endo T, Zhang Y, Miyazaki W, Kakeyama M, Tohyama C. In utero and lactational exposure to low doses of chlorinated and brominated dioxins induces deficits in the fear memory of male mice. Neurotoxicology. 2010;31(4):385–390. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2010.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh YC, Puche AC. Development of the Islands of Calleja. Brain Res. 2013;1490:52–60. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2012.10.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X, Powell-Coffman JA, Jin Y. The AHR-1 aryl hydrocarbon receptor and its co-factor the AHA-1 aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator specify GABAergic neuron cell fate in C. elegans. Development. 2004;131(4):819–828. doi: 10.1242/dev.00959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikemoto S. Dopamine reward circuitry: two projection systems from the ventral midbrain to the nucleus accumbens-olfactory tubercle complex. Brain Res Rev. 2007;56(1):27–78. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakeyama M, Endo T, Zhang Y, Miyazaki W, Tohyama C. Disruption of paired-associate learning in rat offspring perinatally exposed to dioxins. Arch Toxicol. 2014;88(3):789–798. doi: 10.1007/s00204-013-1161-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim MD, Jan LY, Jan YN. The bHLH-PAS protein spineless is necessary for the diversification of dendrite morphology of drosophila dendritic arborization neurons. Genes Dev. 2006;20(20):2806–2819. doi: 10.1101/gad.1459706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura E, Tohyama C. Embryonic and postnatal expression of aryl hydrocarbon receptor mRNA in mouse brain. Front Neuroanat. 2017;11:4. doi: 10.3389/fnana.2017.00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura E, Tohyama C. Vocalization as a novel endpoint of atypical attachment behavior in 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin-exposed infant mice. Arch Toxicol. 2018;92(5):1741–1749. doi: 10.1007/s00204-018-2176-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura E, Kubo KI, Matsuyoshi C, Benner S, Hosokawa M, Endo T, Ling W, Kohda M, Yokoyama K, Nakajima K, Kakeyama M, Tohyama C. Developmental origin of abnormal dendritic growth in the mouse brain induced by in utero disruption of aryl hydrocarbon receptor signaling. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2015;52(Pt A):42–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2015.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura E, Endo T, Yoshioka W, Ding Y, Ujita W, Kakeyama M, Tohyama C. In utero and lactational dioxin exposure induces Sema3b and Sema3g gene expression in the developing mouse brain. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2016;476(2):108–113. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.05.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura E, Kubo KI, Endo T, Ling W, Nakajima K, Kakeyama M, Tohyama C. Impaired dendritic growth and positioning of cortical pyramidal neurons by activation of aryl hydrocarbon receptor signaling in the developing mouse. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(8):e0183497. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0183497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura E, Suzuki G, Uramaru N, Endo T, Maekawa F. Behavioral impairments in infant and adult mouse offspring exposed to 2,3,7,8-tetrabromodibenzofuran in utero and via lactation. Environ Int. 2020;142:105833. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2020.105833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiss EA, Vonarbourg C, Kopfmann S, Hobeika E, Finke D, Esser C, Diefenbach A. Natural aryl hydrocarbon receptor ligands control organogenesis of intestinal lymphoid follicles. Science. 2011;334(6062):1561–1565. doi: 10.1126/science.1214914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latchney SE, Hein AM, O'Banion MK, DiCicco-Bloom E, Opanashuk LA. Deletion or activation of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor alters adult hippocampal neurogenesis and contextual fear memory. J Neurochem. 2013;125(3):430–445. doi: 10.1111/jnc.12130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Innocentin S, Withers DR, Roberts NA, Gallagher AR, Grigorieva EF, Wilhelm C, Veldhoen M. Exogenous stimuli maintain intraepithelial lymphocytes via aryl hydrocarbon receptor activation. Cell. 2011;147(3):629–640. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer EA, Tillisch K, Gupta A. Gut/brain axis and the microbiota. J Clin Invest. 2015;125(3):926–938. doi: 10.1172/JCI76304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGaughy J, Ross RS, Eichenbaum H. Noradrenergic, but not cholinergic, deafferentation of prefrontal cortex impairs attentional set-shifting. Neuroscience. 2008;153(1):63–71. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.01.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mengod G, Vilaro MT, Niznik HB, Sunahara RK, Seeman P, O'Dowd BF, Palacios JM. Visualization of a dopamine D1 receptor mRNA in human and rat brain. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1991;10(2):185–191. doi: 10.1016/0169-328X(91)90110-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mimura J, Fujii-Kuriyama Y. Functional role of AhR in the expression of toxic effects by TCDD. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2003;1619(3):263–268. doi: 10.1016/S0304-4165(02)00485-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mimura J, Yamashita K, Nakamura K, Morita M, Takagi TN, Nakao K, Ema M, Sogawa K, Yasuda M, Katsuki M, Fujii-Kuriyama Y. Loss of teratogenic response to 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) in mice lacking the Ah (dioxin) receptor. Genes Cells. 1997;2(10):645–654. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.1997.1490345.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriceau S, Shionoya K, Jakubs K, Sullivan RM. Early-life stress disrupts attachment learning: the role of amygdala corticosterone, locus ceruleus corticotropin releasing hormone, and olfactory bulb norepinephrine. J Neurosci. 2009;29(50):15745–15755. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4106-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishijo M, Pham TT, Nguyen AT, Tran NN, Nakagawa H, Hoang LV, Tran AH, Morikawa Y, Ho MD, Kido T, Nguyen MN, Nguyen HM, Nishijo H. 2,3,7,8-Tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin in breast milk increases autistic traits of 3-year-old children in Vietnam. Mol Psychiatry. 2014;19(11):1220–1226. doi: 10.1038/mp.2014.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patandin S, Lanting CI, Mulder PG, Boersma ER, Sauer PJ, Weisglas-Kuperus N. Effects of environmental exposure to polychlorinated biphenyls and dioxins on cognitive abilities in Dutch children at 42 months of age. J Pediatr. 1999;134(1):33–41. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(99)70369-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen SL, Curran MA, Marconi SA, Carpenter CD, Lubbers LS, McAbee MD. Distribution of mRNAs encoding the arylhydrocarbon receptor, arylhydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator, and arylhydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator-2 in the rat brain and brainstem. J Comp Neurol. 2000;427(3):428–439. doi: 10.1002/1096-9861(20001120)427:3<428::AID-CNE9>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prast JM, Schardl A, Schwarzer C, Dechant G, Saria A, Zernig G. Reacquisition of cocaine conditioned place preference and its inhibition by previous social interaction preferentially affect D1-medium spiny neurons in the accumbens corridor. Front Behav Neurosci. 2014;8:317. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2014.00317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin H, Powell-Coffman JA. The Caenorhabditis elegans aryl hydrocarbon receptor, AHR-1, regulates neuronal development. Dev Biol. 2004;270(1):64–75. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogan WJ, Gladen BC, Hung KL, Koong SL, Shih LY, Taylor JS, Wu YC, Yang D, Ragan NB, Hsu CC. Congenital poisoning by polychlorinated biphenyls and their contaminants in Taiwan. Science. 1988;241(4863):334–336. doi: 10.1126/science.3133768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothhammer V, Mascanfroni ID, Bunse L, Takenaka MC, Kenison JE, Mayo L, Chao CC, Patel B, Yan R, Blain M, Alvarez JI, Kebir H, Anandasabapathy N, Izquierdo G, Jung S, Obholzer N, Pochet N, Clish CB, Prinz M, Prat A, Antel J, Quintana FJ. Type I interferons and microbial metabolites of tryptophan modulate astrocyte activity and central nervous system inflammation via the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Nat Med. 2016;22(6):586–597. doi: 10.1038/nm.4106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothhammer V, Borucki DM, Tjon EC, Takenaka MC, Chao CC, Ardura-Fabregat A, de Lima KA, Gutierrez-Vazquez C, Hewson P, Staszewski O, Blain M, Healy L, Neziraj T, Borio M, Wheeler M, Dragin LL, Laplaud DA, Antel J, Alvarez JI, Prinz M, Quintana FJ. Microglial control of astrocytes in response to microbial metabolites. Nature. 2018;557(7707):724–728. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0119-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shackleford G, Sampathkumar NK, Hichor M, Weill L, Meffre D, Juricek L, Laurendeau I, Chevallier A, Ortonne N, Larousserie F, Herbin M, Bieche I, Coumoul X, Beraneck M, Baulieu EE, Charbonnier F, Pasmant E, Massaad C. Involvement of aryl hydrocarbon receptor in myelination and in human nerve sheath tumorigenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2018;115(6):E1319–E1328. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1715999115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh ME, McGregor IS, Mallet PE. Perinatal exposure to delta(9)-tetrahydrocannabinol alters heroin-induced place conditioning and fos-immunoreactivity. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31(1):58–69. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith CJ, O'Brien T, Chatzigeorgiou M, Spencer WC, Feingold-Link E, Husson SJ, Hori S, Mitani S, Gottschalk A, Schafer WR, Miller DM., 3rd Sensory neuron fates are distinguished by a transcriptional switch that regulates dendrite branch stabilization. Neuron. 2013;79(2):266–280. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokoloff P, Giros B, Martres MP, Bouthenet ML, Schwartz JC. Molecular cloning and characterization of a novel dopamine receptor (D3) as a target for neuroleptics. Nature. 1990;347(6289):146–151. doi: 10.1038/347146a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soya S, Shoji H, Hasegawa E, Hondo M, Miyakawa T, Yanagisawa M, Mieda M, Sakurai T. Orexin receptor-1 in the locus coeruleus plays an important role in cue-dependent fear memory consolidation. J Neurosci. 2013;33(36):14549–14557. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1130-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi T, Duszkiewicz AJ, Sonneborn A, Spooner PA, Yamasaki M, Watanabe M, Smith CC, Fernandez G, Deisseroth K, Greene RW, Morris RG. Locus coeruleus and dopaminergic consolidation of everyday memory. Nature. 2016;537(7620):357–362. doi: 10.1038/nature19325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanida T, Warita K, Ishihara K, Fukui S, Mitsuhashi T, Sugawara T, Tabuchi Y, Nanmori T, Qi WM, Inamoto T, Yokoyama T, Kitagawa H, Hoshi N. Fetal and neonatal exposure to three typical environmental chemicals with different mechanisms of action: mixed exposure to phenol, phthalate, and dioxin cancels the effects of sole exposure on mouse midbrain dopaminergic nuclei. Toxicol Lett. 2009;189(1):40–47. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van den Berg M, Birnbaum LS, Denison M, De Vito M, Farland W, Feeley M, Fiedler H, Hakansson H, Hanberg A, Haws L, Rose M, Safe S, Schrenk D, Tohyama C, Tritscher A, Tuomisto J, Tysklind M, Walker N, Peterson RE. The 2005 World Health Organization reevaluation of human and mammalian toxic equivalency factors for dioxins and dioxin-like compounds. Toxicol Sci. 2006;93(2):223–241. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfl055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterhouse BD, Navarra RL. The locus coeruleus-norepinephrine system and sensory signal processing: a historical review and current perspectives. Brain Res. 2019;1709:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2018.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zelante T, Iannitti RG, Cunha C, De Luca A, Giovannini G, Pieraccini G, Zecchi R, D'Angelo C, Massi-Benedetti C, Fallarino F, Carvalho A, Puccetti P, Romani L. Tryptophan catabolites from microbiota engage aryl hydrocarbon receptor and balance mucosal reactivity via interleukin-22. Immunity. 2013;39(2):372–385. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziegler DR, Cass WA, Herman JP. Excitatory influence of the locus coeruleus in hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical axis responses to stress. J Neuroendocrinol. 1999;11(5):361–369. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.1999.00337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.