Abstract

This study aimed to investigate the incidence of and risk factors for postoperative new-onset deep venous thrombosis (PNO-DVT) following intertrochanteric fracture surgery. Information on 1672 patients who underwent intertrochanteric fracture surgery at our hospital between January 2016 and December 2019 was extracted from a prospective hip fracture database. Demographic information, surgical data, and preoperative laboratory indices were analysed. Receiver operating characteristic curve analysis, univariate analyses and binary logistic regression analyses were performed. The incidences of postoperative deep venous thrombosis (DVT) and PNO-DVT in inpatients after intertrochanteric fracture surgery were 11.5% (202 of 1751 patients) and 7.4% (123 of 1672 patients), respectively. PNO-DVT accounted for 60.9% of postoperative DVT. Additionally, there were 20 cases of central thrombosis (16.3%), 82 cases of peripheral thrombosis (66.7%), and 21 cases of mixed thrombosis (17.1%). In addition, 82.1% of PNO-DVTs were diagnosed within 8 days after surgery. The multivariate analysis revealed that age > 70 years, duration of surgery (> 197 min), type of anaesthesia (general), and comorbidities (≥ 3) were independent risk factors for the development of PNO-DVT after intertrochanteric fracture surgery. This study demonstrated a high incidence of PNO-DVT in inpatients after intertrochanteric fracture surgery. Therefore, postoperative examination for DVT should be routinely conducted for patients.

Subject terms: Biological techniques, Genetics

Introduction

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) has become the third leading vascular disease following acute myocardial infarction and stroke, and its incidence increases with age1. VTE is not only associated with increasing morbidity and mortality but also correlated with a greater economic burden2,3. Deep venous thrombosis (DVT), one main manifestation of venous thromboembolism (VTE), is a serious complication that is closely associated with increased morbidity and mortality after intertrochanteric fractures4. Previous studies have reported that the incidence of perioperative DVT due to hip fractures, including femoral neck fractures and intertrochanteric fractures, ranges from 11.1 to 34.98%1,5–7. Some studies have also reported that the prevalence of DVT is as high as 62% in patients with hip fractures when the time to surgery is delayed by more than 2 days8. Most of these studies were conducted to detect the incidence of and risk factors for preoperative DVT in patients with hip fractures and combined the rates of DVT for femoral neck fractures and intertrochanteric fractures. Park et al.9 found that the prevalence of preoperative DVT following hip fractures was 18.4% (56 of 305 patients). A 16.3% incidence of preoperative DVT following hip fractures has been reported by Luksameearunothai et al.10.

It has been reported that postoperative DVT can increase patient mortality11. However, limited studies have been conducted to detect the incidence of postoperative DVT, especially postoperative new-onset DVT (PNO-DVT), after hip fractures. Song et al.6 reported that the prevalence of postoperative DVT following hip fractures was 32.8% (39 in 119 patients). Zhang et al. investigated the prevalence of preoperative and postoperative DVT in patients with hip fractures and found that the incidence of postoperative DVT was 57.23%6. These studies did not explore the incidence of or risk factors for PNO-DVT, which is important for the perioperative management of intertrochanteric fractures. Furthermore, no study has investigated the prevalence of or risk factors for PNO-DVT in inpatients with intertrochanteric fractures alone. Previous studies have reported several risk factors associated with the rate of DVT after hip fractures, including age, female sex, cardiovascular disease, pulmonary disease, cancer, previous hospitalization for VTE, and type of anaesthesia1,12,13. Recent studies have found that the time from injury to surgery, anaemia, fibrinogen, D-dimer, and blood loss are associated with the incidence of DVT after hip fractures6,9,14. Park et al. found that high-energy injuries were associated with the development of DVT after hip fractures15.

Few studies have investigated the risk factors for PNO-DVT in intertrochanteric fracture patients. The present study aimed to detect the incidence of and risk factors for PNO-DVT in inpatients with intertrochanteric fractures.

Patients and methods

Patients

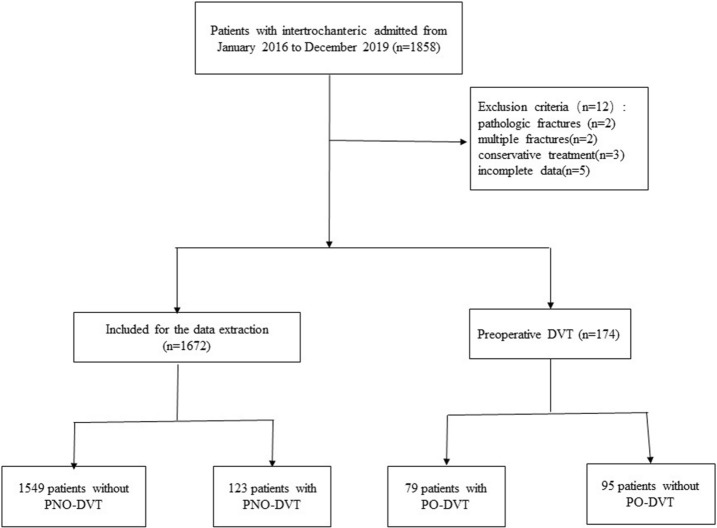

This study was a prospective study and was performed in a level I trauma centre of a tertiary university hospital. Data from a total of 1672 patients who underwent intertrochanteric fracture surgery in our hospital from January 2016 to December 2019 were extracted from a prospective intertrochanteric fracture database and analysed according to the exclusion criteria (Fig. 1). The exclusion criteria of this study were patients with (1) conservative treatment; (2) preoperative DVT; (3) pathologic fracture; (4) multiple fractures; and (5) incomplete data. The Institutional Review Board of Third Hospital of Hebei Medical University approved our study. This study followed the principles outlined in the Helsinki Declaration, and informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Figure 1.

The flow chart for the selection of study participants.

Methods

Patients with intertrochanteric fractures were conventionally injected with subcutaneous low-molecular-weight heparin sodium (LMWHS, 4250 IU, once daily) during their hospital stay, and LMWHS was stopped at least 12 h prior to surgery and restarted at least 12 h after surgery16,17. Mechanical prophylaxis was performed by an intermittent foot pump during hospitalization. Colour Doppler ultrasound was used to detect the presence of DVT in both lower limbs at hospitalization, after the operation (1–2 days after surgery) and before discharge. If the surgery was delayed more than 72 h, ultrasound examination was performed again before the operation. Examination was required every 3 days postoperatively until discharge from the hospital. The diagnosis of DVT was made by sonographers, and the diagnostic criteria were based on the Robinov group’s criteria18. PNO-DVT in this study was defined as the in-hospital postoperative new-onset DVT which was occurring during hospitalization after operation. We recorded the types of DVT, which were divided into central-type thrombosis, peripheral-type thrombosis, and mixed-type thrombosis. The central type included thrombosis in the iliac, superficial femoral, femoral and popliteal veins, occurring proximal to the knee. The peripheral type referred to thrombosis in the posterior tibial and peroneal veins. The mixed type was defined as thrombosis involving both types. The time of thrombus formation was also reviewed.

We selected approximately 80 variables that might be potential risk factors for the development of DVT after intertrochanteric fractures, including demographic and fracture characteristics, laboratory indices, and surgical data. The demographic characteristics included age, sex, body mass index (BMI), residential location (rural or urban), medical complications, smoking history, and disease (e.g., cancer). The medical comorbidities were hypertension, cardiovascular disease (coronary heart disease and arrhythmia), cerebrovascular disease (haemorrhagic and ischaemic encephalopathy), chronic respiratory disease, (diabetes mellitus, chronic bronchitis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and bronchiectasis), liver disease (viral hepatitis and liver cirrhosis), renal disease (glomerulonephritis and chronic renal failure), and rheumatologic disease. The number of medical comorbidities was recorded as 0, 1–2, or ≥ 3. The American Society of Anesthesiologists score (ASA score) of each patient was also obtained, and the cases were divided into scores of 1–2 and 3–4. The fracture characteristics and surgical variables included the injury mechanism, duration of surgery, anaesthesia method, and implant type (intramedullary or extramedullary device). The laboratory indices were preoperative laboratory indices that were measured at the time of admission.

Statistical analysis

All patients were divided into two groups: the DVT group and the without-DVT group. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis was conducted to identify the optimum cut-off value for continuous variables, including age, time to surgery, duration of surgery, and variables (e.g., BMI). Continuous variable data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation and were analysed by either Student’s t test or the Mann–Whitney U test as appropriate. Nonnormally distributed variables are reported as median values with quartiles. Categorical variables are presented as the frequency and percentage and were tested by the Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test. Binary logistic regression modelling was conducted to distinguish the independent predictors of DVT according to the results of the univariate analysis. SPSS v23.0 software (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) was used for all statistical analyses. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05.

Results

Clinical parameters

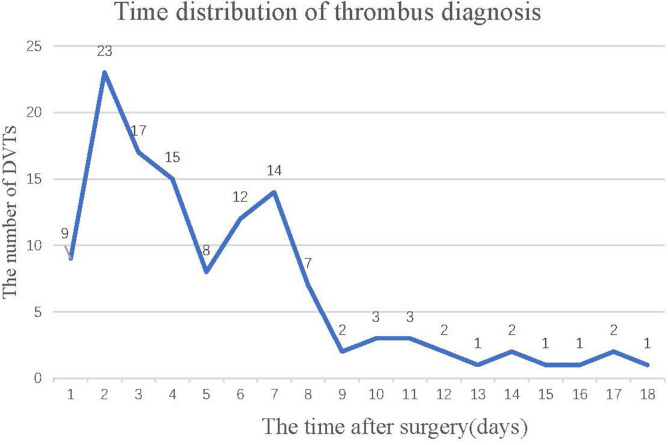

A total of 1672 patients with intertrochanteric fractures were analysed in our study. The incidences of postoperative DVT and PNO-DVT in inpatients after intertrochanteric fracture surgery were 11.5% (202 of 1751 patients) and 7.4% (123 of 1672 patients), respectively. PNO-DVT accounted for 60.9% of postoperative DVT. Additionally, there were 20 cases of central thrombosis (16.3%), 82 cases of peripheral thrombosis (66.7%), and 21 cases of mixed thrombosis (17.1%). The detection time of DVT was shown in Fig. 2, and 82.1% of DVTs were diagnosed within 8 days after surgery. Moreover, the results showed that 7 proximal PNO-DVT patients were treated with inferior vena cava filter placement, and the others, including proximal PNO-DVT, distal PNO-DVT and mixed PNO-DVT patients, received anticoagulation therapy (LMWH sodium, 4250 IU every 12 h). Ultimately, complete recanalization or partial recanalization was observed in all of the patients.

Figure 2.

The diagnosis time of PNO-DVT in patients.

The results of the ROC curve analysis are shown in Table 1. The comparison of demographics and fracture characteristics between the two groups is shown in Table 2. There were 965 females and 707 males. The average age of all patients was 73.2 ± 14.4 years. Significant differences were found between the two groups in patients aged > 70 years (68.3% in the without-DVT group vs 78.9% in the DVT group, p = 0.015). There were more patients with high-energy injuries in the DVT group than in the without-DVT group, but no significant difference was found between the groups in terms of the injury mechanism (p = 0.346). Significant differences in terms of traumatic brain injury and comorbidities (no.) were found between the two groups. The mean intraoperative blood loss in the DVT group was 323.6 ± 466.52 ml, which was more than that in the without-DVT group. A comparison of preoperative laboratory indicators between the two groups is shown in Table 3, and no significant difference was found between the two groups. A comparison of surgical data between the two groups is shown in Table 4. Significant differences were found between the two groups in terms of spinal anaesthesia, implant and duration of surgery. In addition, the other data were comparable between them.

Table 1.

Optimum cut-off value of continuous variables detected by the ROC analysis.

| Variables | Cut-off value | Area under the ROC curve (AUC) | P value | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 70 | 0.560 | 0.025 | 0.510–0.609 |

| Time to surgery (days) | 2 | 0.514 | 0.592 | 0.462–0.566 |

| Duration of surgery (min) | 197 | 0.505 | 0.853 | 0.450–0.560 |

ROC receiver-operating characteristic, CI confidence interval.

Table 2.

Comparison of demographics and fracture characteristics between the two groups.

| Variables | Overall (N = 1672) | Without DVT (N = 1549) | With DVT (N = 123) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (> 70, years), n (%) | 1155 (69.1) | 1058 (68.3) | 97 (78.9) | 0.015 |

| Gender (male), n (%) | 707 (42.3) | 656 (42.3) | 51 (41.5) | 0.848 |

| Residential location (urban), n (%) | 749 (44.8) | 692 (44.7) | 57 (46.3) | 0.720 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 746 (44.6) | 694 (44.8) | 52 (42.3) | 0.587 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 342 (20.5) | 313 (20.2) | 29 (23.6) | 0.372 |

| Cerebrovascular disease, n (%) | 515 (30.8) | 471 (30.4) | 44 (35.8) | 0.215 |

| Cardiovascular disease, n (%) | 551 (33.0) | 502 (32.4) | 49 (39.8) | 0.009 |

| Chronic respiratory disease, n (%) | 83 (5.0) | 79 (5.1) | 4 (3.3) | 0.364 |

| Smoking history, n (%) | 113 (6.8) | 107 (6.9) | 6 (4.9) | 0.388 |

| Preoperative systemic infection, n (%) | 41 (2.5) | 41 (2.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0.068 |

| Tumors, n (%) | 36 (2.2) | 33 (2.1) | 3 (2.4) | 0.820 |

| Traumatic brain injury, n (%) | 20 (1.2) | 16 (1.1) | 4 (3.3) | 0.029 |

| Liver disease, n (%) | 36 (2.2) | 33 (2.1) | 3 (2.4) | 0.820 |

| Renal disease, n (%) | 48 (2.9) | 47 (3.0) | 1 (0.8) | 0.156 |

| Rheumatoid diseases, n (%) | 21 (1.3) | 20 (1.3) | 1 (0.8) | 0.647 |

| Previous surgical history | 258 (15.4) | 234 (15.1) | 24 (19.5) | 0.193 |

| Comorbidities (no.), n (%) | 0.004 | |||

| 0 | 323 (19.3) | 309 (19.9) | 14 (11.4) | |

| 1–2 | 758 (45.3) | 708 (45.7) | 50 (40.7) | |

| ≥ 3 | 591 (35.3) | 532 (34.3) | 59 (48.0) | |

| ASA3–4, n (%) | 767 (45.9) | 707 (45.9) | 60 (48.8) | 0.891 |

| BMI, n (%) | 0.664 | |||

| < 18.5 | 93 (5.6) | 88 (5.7) | 5 (4.1) | |

| 18.5–23.9 | 1009 (60.3) | 939 (60.6) | 70 (56.9) | |

| 24–27.9 | 428 (25.6) | 394 (25.4) | 34 (27.6) | |

| 28–31.9 | 115 (6.9) | 104 (6.7) | 11 (8.9) | |

| ≥ 32 | 27 (1.6) | 24 (1.5) | 3 (2.4) | |

| Injury mechanism (high energy), n (%) | 139 (8.3) | 126 (8.1) | 13 (10.6) | 0.346 |

| Side (left), n (%) | 809 (48.4) | 707 (51.5) | 66 (53.7) | 0.637 |

ASA American Society of Anesthesiologists, BMI body mass index.

Table 3.

Comparison of preoperative laboratory indicators between the two groups.

| Variables | Without POP (N = 1945) | With POP (N = 53) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| TP < 65 g/L, n (%) | 1185 (82.2) | 47 (88.7) | 0.222 |

| ALB < 35 g/L, n (%) | 975 (67.6) | 37 (69.8) | 0.737 |

| GLOB (references 20–40 g/L), n (%) | 0.693 | ||

| < 20 | 228 (15.8) | 7 (13.2) | |

| > 40 | 12 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | |

| A/G (references 1.2–2.4), n (%) | 0.676 | ||

| < 1.2 | 314 (21.8) | 13 (24.5) | |

| > 2.4 | 16 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | |

| ALT (references 9–50 U/L), n (%) | 0.431 | ||

| < 9 | 162 (11.2) | 8 (15.1) | |

| > 50 | 72 (5.0) | 1 (1.9) | |

| AST (references 15–40 U/L), n (%) | 0.807 | ||

| < 15 | 269 (18.7) | 9 (17.0) | |

| > 40 | 140 (9.7) | 4 (7.5) | |

| TBIL (> 26), n (%) | 192 (13.3) | 9 (17.0) | 0.442 |

| DBIL (> 6), n (%) | 648 (44.9) | 30 (56.6) | 0.145 |

| IBIL (> 14), n (%) | 242 (16.8) | 10 (18.9) | 0.061 |

| ALP (references 45–125 U/L), n (%) | 0.720 | ||

| < 45 | 169 (11.7) | 7 (13.2) | |

| > 125 | 92 (6.4) | 2 (3.8) | |

| GGT (references 10–60 U/L), n (%) | 0.936 | ||

| < 10 | 83 (5.8) | 3 (5.7) | |

| > 60 | 116 (8.0) | 5 (9.4) | |

| CHE (references 5–12 U/L), n (%) | 0.254 | ||

| < 2 | 627 (43.5) | 29 (54.7) | |

| > 12 | 5 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | |

| TBA (references 1–10 μmol/L), n (%) | 0.411 | ||

| < 1 | 91 (6.3) | 3 (5.7) | |

| > 10 | 164 (11.4) | 3 (5.7) | |

| HCRP (> 8 mg/L), n (%) | 1210 (83.9) | 45 (84.9) | 0.846 |

| CK (> 310 U/L), n (%) | 297 (20.6) | 11 (20.8) | 0.978 |

| CKMB (> 20 U/L), n (%) | 219 (15.2) | 14 (26.4) | 0.027 |

| LDH (> 250 U/L), n (%) | 461 (32.0) | 16 (30.2) | 0.785 |

| TC (> 5.2 μmol/L), n (%) | 95 (6.6) | 2 (3.8) | 0.414 |

| TG (> 1.7 μmol/L), n (%) | 99 (6.9) | 4 (7.5) | 0.847 |

| Na (references 137–147 mmol/L), n (%) | 0.471 | ||

| < 137 | 663 (46.0) | 26 (49.1) | |

| > 147 | 9 (0.6) | 1 (1.9) | |

| K (references 3.5–5.3 mmol/L), n (%) | 0.610 | ||

| < 3.5 | 205 (14.2) | 6 (11.3) | |

| > 5.3 | 16 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | |

| CL (references 99–110 mmol/L), n (%) | 0.050 | ||

| < 99 | 225 (15.6) | 65 (4.5) | |

| > 110 | 65 (4.5) | 6 (11.3) | |

| TCO2 (references 20–30 mmol/L), n (%) | 0.889 | ||

| < 20 | 69 (4.8) | 3 (5.7) | |

| > 30 | 721 (5.0) | 2 (3.8) | |

| GLU (> 6.1), n (%) | 868 (60.2) | 34 (64.2) | 0.761 |

| UREA (> 8), n (%) | 327 (22.8) | 15 (28.3) | 0.320 |

| CREA (references 57–97 mmol/L), n (%) | 0.563 | ||

| < 57 | 623 (43.2) | 20 (37.7) | |

| > 97 | 92 (6.4) | 5 (9.4) | |

| UA (references 208–428 mmol/L), n (%) | 0.302 | ||

| < 208 | 729 (40.6) | 22 (41.5) | |

| > 428 | 44 (3.1) | 3 (5.7) | |

| CA (references 2.11–2.52 mmol/L), n (%) | 0.600 | ||

| < 2.11 | 761 (52.8) | 31 (58.5) | |

| > 2.52 | 12 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | |

| P (references 0.85–1.51 mmol/L), n (%) | 0.579 | ||

| < 0.85 | 185 (12.8) | 9 (17.0) | |

| > 1.51 | 50 (3.5) | 1 (1.9) | |

| Mg (references 0.75–1.02 mmol/L), n (%) | 0.671 | ||

| < 0.75 | 167 (11.6) | 44 (3.1) | |

| > 1.02 | 8 (15.1) | 1 (1.9) | |

| BNP (ng/L), n (%) | < 0.001 | ||

| < 75 | 558 (38.7) | 9 (17.0) | |

| > 75 | 416 (28.8) | 30 (56.6) | |

| Unknown | 468 (32.5) | 14 (26.4) | |

| WBC (references 3.5–9.5 × 109/L), n (%) | 0.307 | ||

| < 3.5 | 10 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | |

| > 9.5 | 513 (35.6) | 24 (45.3) | |

| NEU (references 2.8–6.3 × 109/L), n (%) | 0.071 | ||

| < 1.8 | 3 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | |

| > 6.3 | 749 (51.9) | 36 (67.9) | |

| LYM (references 1.1–3.2 × 109/L), n (%) | 0.818 | ||

| < 1.1 | 752 (52.1) | 29 (54.7) | |

| > 3.2 | 8 (0.6) | 0 (0) | |

| MON (references 0.1–0.6 × 109/L), n (%) | 0.520 | ||

| < 0. 1 | 3 (0.2) | 0 (0) | |

| > 0.6 | 870 (60.3) | 36 (67.9) | |

| EOS (references 0.02–0.05 × 109/L), n (%) | 0.052 | ||

| < 0.02 | 373 (25.9) | 9 (17.0) | |

| > 0.52 | 4 (0.3) | 1 (1.9) | |

| BAS (> 0.06), n (%) | 83 (5.8) | 3 (5.7) | 0.977 |

| RBC (> 5.8), n (%) | 94 (6.5) | 4 (7.5) | 0.766 |

| NEU% (references 45–75%), n (%) | 0.650 | ||

| < 45 | 3 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | |

| > 75 | 865 (60.0) | 35 (66.0) | |

| LYM% (> 5.2), n (%) | 1378 (95.6) | 50 (94.3) | 0.673 |

| MON% (references 3–10%), n (%) | 0.638 | ||

| < 3 | 24 (1.7) | 0 (0.0) | |

| > 10 | 343 (23.8) | 13 (24.5) | |

| BAS% (> 1%), n (%) | 10 (0.7) | 11 (0.7) | 0.318 |

| HGB (< 110/120 g/L), n (%) | 1334 (92.5) | 50 (94.3) | 0.618 |

| MCV (references 82–100 fL), n (%) | 0.086 | ||

| < 82 | 31 (2.1) | 0 (0.0) | |

| > 100 | 110 (7.6) | 8 (15.1) | |

| MCH (references 27–34 pg), n (%) | 0.189 | ||

| < 27 | 38 (2.6) | 0 (0.0) | |

| > 34 | 92 (6.4) | 6 (11.3) | |

| MCHC (references 316–354 g/L), n (%) | 0.074 | ||

| < 316 | 38 (2.6) | 3 (5.7) | |

| > 354 | 61 (4.2) | 5 (9.4) | |

| RDW (references 11.6–16.5%), n (%) | 0.912 | ||

| < 11.6 | 5 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | |

| > 16.5 | 136 (9.4) | 5 (9.4) | |

| PLT (references 125–350 × 109/L), n (%) | 0.996 | ||

| < 125 | 135 (9.4) | 5 (9.4) | |

| > 250 | 86 (6.0) | 3 (5.7) | |

| MPV (references 7.4–11.0 fL), n (%) | 0.246 | ||

| < 7.4 | 227 (15.7) | 12 (22.6) | |

| > 11.0 | 49 (3.4) | 3 (5.7) | |

| PCT (references 0.16–0.43%), n (%) | 0.010 | ||

| < 0.16 | 937 (65.0) | 34 (64.2) | |

| > 0.43 | 7 (0.5) | 2 (3.8) | |

| PDW (references 12.0–18.1%), n (%) | 0.934 | ||

| < 7.4 | 130 (9.0) | 4 (7.5) | |

| > 11.0 | 26 (1.8) | 1 (1.9) | |

| PT (> 12.5 S), n (%) | 333 (23.1) | 10 (18.9) | 0.246 |

| PTA (< 80%), n (%) | 175 (12.1) | 7 (13.2) | 0.873 |

| INR (> 1.4%), n (%) | 11 (0.8) | 1 (1.9) | 0.368 |

| APTT (references 28–42 S), n (%) | 0.934 | ||

| < 28 | 500 (34.7) | 24 (45.3) | |

| > 42 | 20 (1.4) | 0 (0.0) | |

| APTT-R (references 0.7–1.3), n (%) | 0.528 | ||

| < 0.7 | 18 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) | |

| > 1.3 | 16 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | |

| TT (references 14–21 S), n (%) | 0.696 | ||

| < 14 | 1026 (71.2) | 35 (66.0) | |

| > 21 | 151 (10.5) | 6 (11.3) | |

| FIB (reference 2.0–4.4 mg/L), n (%) | 0.708 | ||

| < 2.0 | 16 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | |

| > 4.4 | 350 (24.3) | 14 (26.4) | |

| ATIII (reference 80–120%), n (%) | 0.916 | ||

| < 80 | 295 (20.5) | 12 (22.6) | |

| > 120 | 33 (2.3) | 1 (1.9) | |

| D-Dimer (> 2.26 mg/L), n (%) | 571 (39.6) | 34 (64.2) | < 0.001 |

ASA American Society of Anesthesiologists, BMI body mass index, TP total protein, ALB albumin, GLOB globulin, A/G values albumin/globulin, ALT alanine transaminase, AST aspartate aminotransferase, TBIL total bilirubin, DBIL direct bilirubin, IBIL indirect bilirubin, ALP alkaline phosphatase, GGT γ-glutamyl transpeptidase, CHE cholinesterase, TBA total bile acid, HCRP hypersensitive c-reactive protein, LDH lactate dehydrogenase, CREA creatinine, UA uric acid, CA calcium, P phosphorus, Mg magnesium, BNP brain natriuretic peptide, WBC white blood cell, NEUT neutrophile, LYM lymphocyte, MON mononuclear cell, EOS eosinophilic granulocyte, BAS basophilic granulocyte, RBC red blood cell, reference range: female, 3.5–5.0 × 1012/L; males, 4.0–5.5 × 1012/L. HGB hemoglobin, reference range: females, 110–150 g/L; males, 120–160 g/L, HCT haematocrit, 40–50%, MCV mean corpuscular volume, MCH mean corpuscular hemoglobin, MCHC mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration, RDW red blood cell distribution width, PLT platelet, 100–300 × 109/L, MPV mean platelet volume, PCT procalcitonin, pdw platelet distribution width, PT prothrombin time, PTA prothrombin activity, INR international normalized ratio, APTT activated partial thromboplastin time, APTT-R activated partial thromboplastin time ratio, TT thrombin time, TT-R thrombin ratio, FIB fibrinogen, ATIII antithrombin III.

Table 4.

Comparison of surgical data between the two groups.

| Variables | Without DVT (N = 1549) | With DVT (N = 123) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intraoperative blood loss (ml), mean (SD) | 277.5 (259.87) | 323.6 (466.52) | 0.079 |

| Intraoperative blood transfusion (ml), mean (SD) | 143.8 (349.53) | 102.85 (223.82) | 0.201 |

| Time to surgery (> 2 day), n (%) | 1261 (81.9) | 102 (82.9) | 0.772 |

| Type of anesthesia (general), n (%) | 648 (41.8) | 66 (53.7) | 0.011 |

| Implant, n (%) | 0.025 | ||

| Intramedullary devices | 1438 (92.8) | 122 (99.2) | |

| Extramedullary devices | 111 (7.2) | 1 (0.8) | |

| Duration of surgery (> 197 min), n (%) | 90 (5.8) | 15 (12.2) | 0.005 |

Risk factors for PNO-DVT

In the univariate analysis, age > 70 years, traumatic brain injury, comorbidities (no.), P, type of anaesthesia, implant and duration of surgery exhibited significant differences between the two groups. All the above factors were analysed in the multivariate analysis, and the results are shown in Table 5. Age > 70 years (OR = 1.832, p = 0.016), duration of surgery > 197 min (OR = 3.733, p = 0.000), general anaesthesia (OR = 1.558, p = 0.023) and number of comorbidities ≥ 3 (OR = 2.196, p = 0.015) were independent factors for increasing the risk of PNO-DVT.

Table 5.

OR, 95% CI, and P value for independent risk factors in the multivariable logistic regression analysis of PNO-DVT.

| Variable | OR | 95%CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (> 70 years) | 1.832 | 1.117–3.002 | 0.016 |

| Duration of surgery (> 197 min) | 3.733 | 1.955–7.219 | 0.000 |

| Type of anesthesia (general) | 1.558 | 1.064–2.281 | 0.023 |

| Comorbidities (no.) | |||

| 0 | 0.026 | ||

| 1–2 | 1.479 | 0.787–2.781 | 0.224 |

| ≥ 3 | 2.196 | 1.163–4.416 | 0.015 |

OR odds radio, CI confidence interval, CKMB creatine phosphokinase isoenzyme, BNP brain natriuretic peptide.

Discussion

Although pharmacological prophylaxis is recommended in hip fracture patients, the incidence of DVT remains high. The incidences of postoperative DVT and PNO-DVT in inpatients after intertrochanteric fracture surgery were 11.5% (202 of 1751 patients) and 7.4% (123 of 1672 patients), respectively. Patients with PNO-DVT accounted for 60.9% of those with postoperative DVT. A total of 82.1% of DVTs were diagnosed within 8 days after surgery. However, the diagnosis of DVT might be delayed because the examinations were performed every 3–5 days after surgery. In addition, the results of multivariate logistic regression analysis demonstrated that age > 70 years, duration of surgery > 197 min, general anaesthesia and number of comorbidities ≥ 3 were independent risk factors for the development of PNO-DVT.

The 11.5% incidence of postoperative DVT was similar to that of DVT in previous studies. In their study of DVT in hip fractures, Eriksson et al.19 found that the prevalence of DVT after hip fractures was 14% within postoperative day 11. Wang et al.20 detected the incidence of postoperative DVT in patients with intertrochanteric fractures. They found that the prevalence of DVT after intertrochanteric fracture surgery was 9.94% in 311 patients.

Patients with postoperative DVT could be divided into those with preoperative DVT and those without preoperative DVT, and those without preoperative DVT were defined as PNO-DVT in this study. In the present study, the incidence of PNO-DVT was 7.4% (123 of 1672 patients), which accounted for 60.9% of postoperative DVT. In addition, 39.1% of those patients had preoperative DVT, which was excluded from the statistical analysis. For patients with preoperative DVT, the dosage of LMWH and physical prophylaxis might be different from those of patients without preoperative DVT. In addition, their coagulation function might vary. All of the above might result in possible differences in risk factors for postoperative DVT between patients with PNO-DVT and patients with preoperative DVT. Moreover, a better understanding of the risk factors for PNO-DVT is conducive to taking more measures to prevent the development of PNO-DVT.

Four independent predictive factors for PNO-DVT in inpatients after intertrochanteric fracture surgery were identified in this study. As an independent risk factor for DVT, advanced age has been reported in previous studies. In this study, age > 70 years was a cut-off value for the development of PNO-DVT detected by ROC curve analysis. Shahi et al. reported a risk factor for the development of in-hospital VTE after hip surgery21. These researchers demonstrated that age > 70 years (OR: 1.3, 95%, CI: 1.1–1.4) was an independent factor for increasing the risk of developing in-hospital VTE, which was consistent with our study. Park et al. also reported that age > 60 was an independent risk factor for the development of DVT12. Advanced age has always been associated with frailty and additional comorbidities. Frailty is a common status in patients with intertrochanteric fractures, especially in patients with advanced age, and can seriously affect their quality of life22. Anaemia is a common condition in patients with advanced age that has been demonstrated to increase the risk of DVT23. In addition, immobilization tends to be longer in patients with advanced age, which is one of the primary reasons for the development of DVT24.

The hypercoagulation state is well known as a main factor promoting thrombosis2. Surgery is a significant factor for the formation of DVT after acute trauma in terms of the introduction of the hypercoagulability state5,25. It has been reported that approximately 15% of all VTEs are surgery-related26. The surgery duration was 197 min according to the results of the ROC curve analysis. Multivariate logistic regression analyses revealed that a duration of surgery > 197 min was an independent risk factor for PNO-DVT. Blood loss increased with a prolonged duration of surgery. Riha et al. found that blood loss was an important factor in promoting the hypercoagulability state in their study27. Their study showed that blood loss was associated with an increase in the risk of DVT. Zhang et al. studied the incidences of DVT before and after surgery in in-hospital patients with hip fractures and found that blood loss was correlated with the formation of postoperative DVT6. Therefore, a longer duration of surgery might be associated with the development of DVT, leading to an increased level of coagulation.

The optimal anaesthetic modality in hip fracture surgery remains controversial. The choice of anaesthesia modality in hip fracture surgery often depends on the preference of the surgeon or the anaesthesiologist28. Previous studies have reported that the anaesthesia modality in hip fracture surgery plays an important role in the occurrence of postoperative complications29,30. Some studies have demonstrated that spinal anaesthesia is superior to general anaesthesia in preventing DVT, urinary tract infection, blood loss, superficial wound infection and overall complications13,31. The results of this study were the same as those of a previous study on the association between anaesthesia and DVT. The percentage of patients with general anaesthesia was 53.7% (66 of 123 patients) in the DVT group, whereas the percentage of patients in the without-DVT group was 41.8%. Significant differences in anaesthesia modality were found between the two groups (p = 0.011). In addition, the present study demonstrated that the risk for developing DVT in patients with general anaesthesia after intertrochanter fracture surgery was increased 1.558-fold compared with that in patients with spinal anaesthesia. The explanation for this phenomenon might be that general anaesthesia increases the length of hospital stay32. Further studies should be conducted to explore the specific mechanism of anaesthesia and DVT.

There were some strengths in our study. Few studies have investigated the risk factors for PNO-DVT, and this study excluded patients with preoperative DVT. Moreover, the data of this study were based on a prospective database, and approximately 80 factors were analysed in this study. All of the above would help increase the reliability and accuracy of the results in the present study. However, our study did have some limitations. First, all the data were extracted from one hospital. Additionally, this study was a single-centre study, which was limited by its inherent defects. Further multicentre randomized controlled trials are warranted. Second, some comorbidities, such as varicose veins and defects of the coagulation system, were not discussed in our study. Third, one limitation of this study was that the recent use of antiplatelet drugs (within 1 week before injury) was not analysed. A previous study reported that the recent use of antiplatelet drugs (within 1 week before injury) could decrease the incidence of preoperative DVT in femoral neck fracture. However, the effect of the recent use of antiplatelet drugs on postoperative hip fractures was not demonstrated. The potential mechanism by which antiplatelet drugs decrease the development of preoperative DVT might be associated with blood coagulation indices. Considering the potential influence of the recent use of antiplatelet drugs on PNO-DVT, we extracted the preoperative blood coagulation indices of all patients on admission. Fourth, no follow-up on patients was conducted, and the association between PNO-DVT and adverse events after surgery in the mid- or long-term could not be demonstrated.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated a high incidence of PNO-DVT in inpatients after intertrochanteric fracture surgery. Therefore, postoperative examination for DVT should be routinely conducted for patients.

Author contributions

K.Z., Data collection and analysis, Writing of paper. J.Z.Z. and J.L., Data collection and analysis of results. H.Y.M., Data collection and analysis. Z.Y.H., conceived the idea for this study. Y.Z.Z., discussion/design of project, Writing of paper.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 82072447, 81401789, 2019YFC0120600).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Kuo Zhao, Junzhe Zhang and Junyong Li.

References

- 1.Shin WC, Woo SH, Lee SJ, et al. Preoperative prevalence of and risk factors for venous thromboembolism in patients with a hip fracture: An indirect multidetector CT venography study. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 2016;98(24):2089–2095. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.15.01329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Di Nisio M, van Es N, Büller HR. Deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. Lancet. 2016;388:3060–3073. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(16)30514-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Raskob GE, Angchaisuksiri P, Blanco AN, et al. Thrombosis: A major contributor to the global disease burden. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2014;12:1580–1590. doi: 10.1111/jth.12698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carpintero P, Caeiro JR, Carpintero R, et al. Complications of hip fractures: A review. World J. Orthop. 2014;5:402–411. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v5.i4.402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Song K, Yao Y, Rong Z, et al. The preoperative incidence of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and its correlation with postoperative DVT in patients undergoing elective surgery for femoral neck fractures. Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. 2016;136:1459–1464. doi: 10.1007/s00402-016-2535-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang BF, Wei X, Huang H, et al. Deep vein thrombosis in bilateral lower extremities after hip fracture: A retrospective study of 463 patients. Clin. Interv. Aging. 2018;13:681–689. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S161191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu D, Niu S. Risk factors of preoperative DVT for patients with intertrochanteric fractures. Chin. J. Geriatr. Orthop. Rehabil. (Electronic Edition) 2020;6:3. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roberts TS, Nelson CL, Barnes CL, et al. The preoperative prevalence and postoperative incidence of thromboembolism in patients with hip fractures treated with dextran prophylaxis. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1990;255:198–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feng L, Xu L, Yuan W, et al. Preoperative anemia and total hospitalization time are the independent factors of preoperative deep venous thromboembolism in Chinese elderly undergoing hip surgery. BMC Anesthesiol. 2020;20:72. doi: 10.1186/s12871-020-00983-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luksameearunothai P, Sa-Ngasoongsong N, Kulachote S, et al. Usefulness of clinical predictors for preoperative screening of deep vein thrombosis in hip fractures. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2017;18:208. doi: 10.1186/s12891-017-1582-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Falck-Ytter Y, Francis CW, Johanson NA, et al. Prevention of VTE in orthopedic surgery patients: Antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141:e278S–e325S. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-2404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park SJ, Kim CK, Park YS, et al. Incidence and factors predicting venous thromboembolism after surgical treatment of fractures below the hip. J. Orthop. Trauma. 2015;29(10):e349–e354. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0000000000000336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fields AC, Dieterich JD, Buterbaugh K, et al. Short-term complications in hip fracture surgery using spinal versus general anaesthesia. Injury. 2015;46:719–723. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2015.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xing F, Li L, Long Y, et al. Admission prevalence of deep vein thrombosis in elderly Chinese patients with hip fracture and a new predictor based on risk factors for thrombosis screening. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2018;19:444. doi: 10.1186/s12891-018-2371-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang H, Kandemir U, Liu P, et al. Perioperative incidence and locations of deep vein thrombosis following specific isolated lower extremity fractures. Injury. 2018;49:1353–1357. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2018.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anderson DR, Morgano GP, Bennett C, et al. American Society of Hematology 2019 guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism: Prevention of venous thromboembolism in surgical hospitalized patients. Blood Adv. 2019;3:3898–3944. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2019000975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wendt K, Heim D, Josten C, et al. Recommendations on hip fractures. Eur. J. Trauma Emerg. Surg. 2016;42:425–431. doi: 10.1007/s00068-016-0684-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rabinov K, Paulin S. Roentgen diagnosis of venous thrombosis in the leg. Arch. Surg. 1972;104:134–144. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1972.04180020014004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eriksson BI, Bauer KA, Lassen MR, et al. Fondaparinux compared with enoxaparin for the prevention of venous thromboembolism after hip-fracture surgery. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001;345:1298–1304. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Su H, Liu H, Liu J, Wang X. Elderly patients with intertrochanteric fractures after intramedullary fixation: Analysis of risk factors for calf muscular vein thrombosis. Orthopade. 2018;47:341–346. doi: 10.1007/s00132-018-3552-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shahi A, Chen AF, Tan TL, et al. The incidence and economic burden of in-hospital venous thromboembolism in the United States. J. Arthroplasty. 2017;32:1063–1066. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2016.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kua J, Ramason R, Rajamoney G, et al. Which frailty measure is a good predictor of early post-operative complications in elderly hip fracture patients? Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. 2016;136:639–647. doi: 10.1007/s00402-016-2435-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abdullah HR, Sim YE, Hao Y, et al. Association between preoperative anaemia with length of hospital stay among patients undergoing primary total knee arthroplasty in Singapore: A single-centre retrospective study. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e016403. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chang CJ, Chen YT, Liu CS, et al. Atrial fibrillation increases the risk of peripheral arterial disease with relative complications and mortality: A population-based cohort study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95:e3002. doi: 10.1097/md.0000000000003002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kupcinskiene K, Trepenaitis D, Petereit R, et al. Monitoring of hypercoagulability by thromboelastography in bariatric surgery. Med. Sci. Monit. 2017;23:1819–1826. doi: 10.12659/msm.900769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jensvoll H, Severinsen MT, Hammerstrøm J, et al. Existing data sources in clinical epidemiology: The Scandinavian Thrombosis and Cancer Cohort. Clin. Epidemiol. 2015;7:401–410. doi: 10.2147/clep.S84279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Riha GM, Kunio NR, Van PY, et al. Uncontrolled hemorrhagic shock results in a hypercoagulable state modulated by initial fluid resuscitation regimens. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013;75:129–134. doi: 10.1097/ta.0b013e3182984a9b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Riha GM, Kunio NR, Van PY, et al. Anesthesia technique, mortality, and length of stay after hip fracture surgery. JAMA. 2014;311:2508–2517. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.6499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Neuman MD, Silber JH, Elkassabany NM, et al. Comparative effectiveness of regional versus general anesthesia for hip fracture surgery in adults. Anesthesiology. 2012;117:72–92. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3182545e7c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Parker MJ, Handoll HH, Griffiths R. Anaesthesia for hip fracture surgery in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2004 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000521.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maurer SG, Chen AL, Hiebert R, et al. Comparison of outcomes of using spinal versus general anesthesia in total hip arthroplasty. Am. J. Orthop. (Belle Mead NJ) 2007;36:E101–E106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen DX, Yang L, Ding L, et al. Perioperative outcomes in geriatric patients undergoing hip fracture surgery with different anesthesia techniques: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2019;98:e18220. doi: 10.1097/md.0000000000018220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]