Abstract

Introduction

The purpose of this study was to compare patient-specific acetabular cup target orientation using functional simulation to the Lewinnek Safe Zone (LSZ) and determine associated rates of postoperative dislocation.

Methods

A retrospective review of 1500 consecutive primary THAs was performed. Inclination, anteversion, pelvic tilt, pelvic incidence, lumbar flexion, and dislocation rates were recorded.

Results

56% of dynamically planned cups were within LSZ (p < 0.05). 6/1500 (0.4%) of these cups dislocated at two year follow-up, and all were within LSZ.

Conclusion

Optimal acetabular cup positioning using dynamic imaging differs significantly from historical target parameters but results in low rates of dislocation.

Level of evidence

Level III: Retrospective;

Keywords: Total hip arthroplasty, Dislocation, Patient-specific components, Cup positioning, Dynamic imaging, Technology

1. Introduction

The “safe zone” for acetabular inclination (40° ± 10°) and anteversion (15° ± 10°) in total hip arthroplasty (THA) was originally described by Lewinnek et al. 4 decades ago and has since been referred to as the “Lewinnek safe zone” (LSZ).1 Although the concept of LSZ is widely used in clinical practice, the majority of dislocations have been shown to occur within the proposed safe zone.2 Dislocations continue to be the most common cause of revision surgery within the first 2 years postoperatively.3 Attempts to elucidate the reason for postoperative dislocation have not been able to reproduce the original authors’ guide to predict hip stability and avoid mechanical complications.2,4, 5, 6, 7 Consequently, THA surgeons have come to identify implant size and diameter, component positioning, surgical approach, correction of joint biomechanics, and soft tissue preservation and tensioning as crucial factors in THA stability.7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14

Measured using lateral sitting and standing x-rays, functional cup positioning describes the changes in cup position that occur with changes in posture. Cup inclination and anteversion measured in the coronal plane on standard pelvic x-rays (i.e. LSZ) and obtained at surgery do not represent the position of the cup during these functional activities.15, 16, 17 This is particularly true in patients with limited changes in the orientation of pelvic tilt, such as those with spinopelvic disease, which alters the ability to keep the cup in the “safe zone”.5,18, 19, 20 Heckmann and colleagues described some form of spinopelvic imbalance in 90% of hip dislocations.19 Meanwhile, DelSole et al. found that among spinal deformity patients who dislocated after THA, 80% had safe anteversion, 80% had safe inclination, and 60% had both parameters within the LSZ.5 As such, it can be inferred that dynamic functional cup positioning reliably accounts for variations in acetabular orientation during pelvic mobility, something that cannot be accurately described using static operative coronal positioning (LSZ).21

Using a functional and dynamic simulation that accounts for individual patient anatomy and variations in pelvic tilt, we created a patient-specific target orientation for the acetabular cup. The purposes of this study were to: (1) compare pre-operative acetabular cup parameters using this novel dynamic imaging sequence to the Lewinnek safe zone, and (2) describe the rates of dislocation in patients whose pre-operative acetabular cup parameters were determined using this novel dynamic imaging sequence.

2. Materials and methods

A retrospective review of 1500 consecutive primary THAs that took place between January 2017 to March 2018 at multiple institutions was conducted. All THAs were performed via the posterior approach with posterior soft tissue capsular repair. Inclusion criteria included patients with radiographically evident end-stage osteoarthritis who had failed conservative management and been indicated for primary unilateral THA. Exclusion criteria included patients with prior THA. Included THA candidates underwent dynamic pre-operative acetabular cup planning utilizing pre-operative radiographic imaging (Optimized Positioning System (OPS)™, Corin Group, Cirencester, UK). Close follow-up and evaluation of these patients was performed by chart review and direct contact at each surgeon's clinic and office. This study involved the first 1500 patients in the United States who received a THA performed with the OPS™ computer navigation system and were available for a minimum 2-year follow-up.

2.1. Pre-operative imaging

A few weeks prior to arthroplasty, each patient had 4 sagittal functional x-rays taken: supine, standing, flex-seated, and step-up. Positioning the patient in a hip flexed, seated posture and stepping up onto a raised surface prior to obtaining lateral x-rays in these functional positions can be useful for preoperative evaluation of posterior and anterior dislocation risks, respectively. Additionally, all patients underwent a low-dose computerized tomography (CT) scan to capture the individual's bony hip anatomy as well as soft tissue landmarks. Utilizing these functional images, parameters such as pelvic tilt, pelvic incidence, and lumbar flexion angles were measured (Fig. 1). The pelvic tilt angle was measured between the anterior pelvic plane (anatomic plane defined by the 2 anterior superior iliac spines and the pubic tubercle) and the coronal plane.22 This angle can be positive if the pelvis is tilted anteriorly or negative if the pelvis is tilted posteriorly when compared to the coronal plane. The pelvic incidence angle was measured between a line perpendicular to the sacral plate at its midpoint and a line connecting this point to the middle axis of the femoral heads.23 Lumbar flexion angles were measured as the difference between the lumbar lordotic angle (angle between the superior endplates of L1 and S1) in the standing and flex-seated positions.24 These measurements helped define bony position at the limits of hip extension and flexion. Risk factors for adverse spinopelvic mobility included the following5,24, 25, 26, 27, 28:

-

(1)

Stiff lumbar spine, defined by a lumbar flexion ≤20°

-

(2)

Large standing posterior pelvic tilt, characterized by a standing pelvic tilt ≤ −10°

-

(3)

Severe sagittal spinal deformity, defined by a pelvic incidence minus lumbar lordosis mismatch of ≥20°

Fig. 1.

Standing lateral radiograph demonstrating spinopelvic measurements. The pelvic incidence (PI) measurement is obtained by drawing a line from the center point of the femoral heads to the center of the superior endplate of S1, with another line drawn perpendicular to the S1 endplate. PI is a constant value, reflective of body morphology after skeletal maturity is reached. The lumbar lordosis (LL) measurement is obtained by measuring the Cobb angle between the superior endplate of L1 and superior endplate of S1. Pelvic tilt (PT) is measured by taking the angle between the two anterior superior iliac spines (or horizontal midpoint between the two if rotated) and the pubic symphysis and a vertical reference line. Lumbar flexion (LF) is calculated by the difference between standing versus flex-seated lumbar lordosis.

2.2. Determination of optimal cup orientation

Using these measurements, patient-specific femoral and acetabular component templating was performed utilizing the OPS™ computer-based software program with the goal of restoring native anatomy and achieving optimal metaphyseal loading. The results of the component templates are then inputted into a flexion/extension dynamic simulation that is guided by the aforementioned functional radiographic measurements. The hip joint reaction forces across the articulating surface throughout flexion and extension are then plotted for 9 different acetabular cup orientations (Fig. 2). These polar plots represent the cup orientation's effect on contact mechanics across a patient-specific hip joint. With the help of the simulation, the optimal cup orientation, through targeted inclination and anteversion angles, is calculated.

Fig. 2.

(a) The nine black points on the Functional Hip Analysis (FHA) report represent the nine supine cup orientation as presented to the arthroplasty surgeon during preoperative evaluation. These orientation options are equivalent to cup orientations of 40° ± 5° inclination and 25° ± 5° anteversion referenced to the coronal plane when standing. The surgeon can toggle between these nine supine cup orientations using interactive buttons on the FHA report to view functional cup orientations during activities hip flexion and extension. Callanan et al.’s safe zone of 30–45° inclination and 5–25° anteversion is displayed within the background of the FHA plot, to be utilized as a reference for target cup orientation. It is not recommended to directly apply this zone when considering cup orientations during flexion and extension. Furthermore, surgeon discretion should always be used with determining target cup orientation as it is possible that some of the nine supine cup orientations may fall outside of Callanan's recommendation. It is prudent for surgeons to use this FHA plot in conjunction with other clinical information in order to determine a prescribed cup orientation. The final decision on target angles should be made by the operating surgeon after thorough consideration of all potential factors that influence cup orientation. (b) Lateral x-rays obtained in functional positions (standing, flexed seated, step-up) can be utilized to analyze patient-specific spinopelvic mobility through the evaluation and measurement of pelvic tilt, sacral slope, and lumbar lordotic angle.

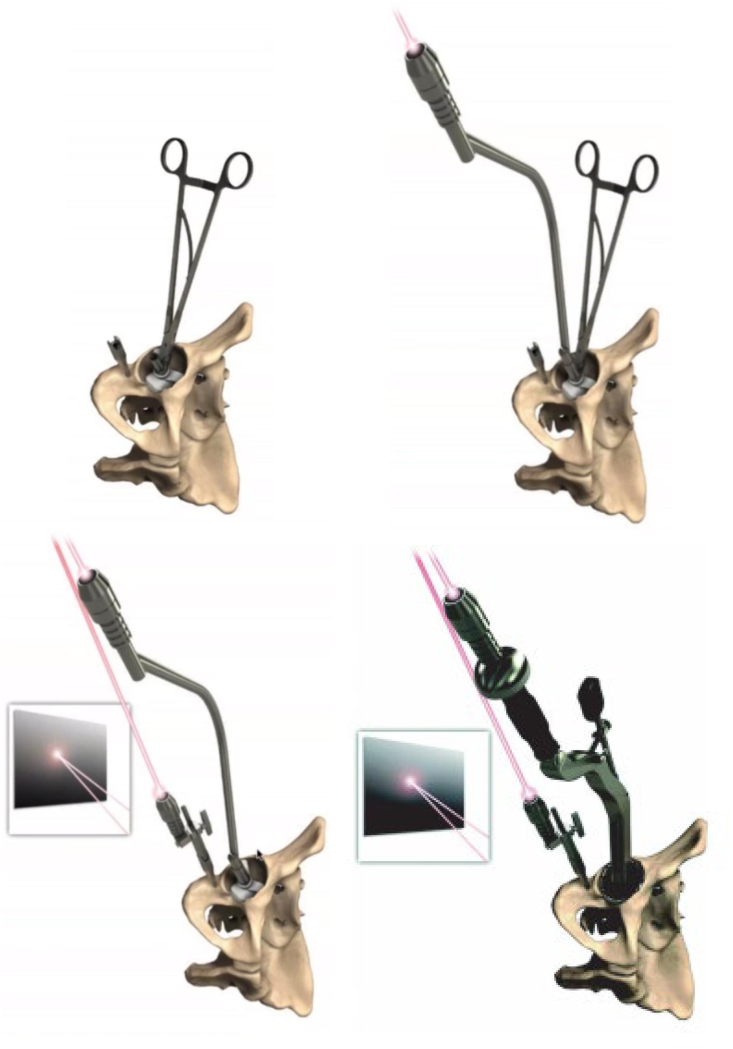

2.3. Intra-operative implementation

After the surgeon achieves their desired surgical exposure, the femoral guide is placed on the femoral head-neck junction to assist with femoral neck osteotomy. Attention is then diverted to the acetabulum with placement of the acetabular guide. A laser handle that connects to the acetabular guide as well as a laser mounted to the pelvis helps position the final cup in the targeted optimal orientation (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Intraoperatively, a sterile, patient-specific surgical guide is placed within the acetabulum to define the target acetabular orientation and an adjacent pin is placed in the pelvis (either on the ischium or just above the acetabulum) for placement of the pelvic reference laser. A laser is mounted on the guide within the acetabulum and then, a second laser guide is placed on the pelvis. Two laser marks will be visible on the operating room wall or ceiling and the marks are focused until coincident. Once the lasers are aligned, the acetabular guide and laser are removed and acetabular preparation and implantation is performed with the pelvic laser still in place, to be used as a reference. Following cup implantation, a laser is reintroduced and placed on the cup. The laser mark originating from the cup is compared with that from the pelvis to ensure orientation is correct.

2.4. Data analysis

Inclination and anteversion angles obtained through this targeted cup positioning system were compared to LSZ. Postoperative dislocations were recorded up to the patient's latest follow-up.

2.5. Statistical analysis

Data was collected, de-identified, and stored in Microsoft Excel Version 1710 (Microsoft, Redmond, Washington). All descriptive and inferential statistics were conducted using SPSS v23 (International Business Machines, Armonk NY) statistics software. Chi-square tests were performed to compare categorical variables and two-tailed Student's t-tests were performed to compare means among continuous variables. All tests performed were 2-sides where a p-value <0.05 was deemed statistically significant.

3. Results

The mean age of patients was 63 years (range, 18 to 95). The minimum follow-up was 2 years for the whole cohort. Pre-operative functional parameters included a mean supine pelvic tilt of 4.7° (range, −31° to 21°), standing pelvic tilt of −0.3° (range, −33° to 23°), and flex-seated pelvic tilt of −0.7° (range, −42° to 32°). Mean pelvic incidence was 54° (range, 24° to 88°) and mean lumbar flexion was 43° (range, 0° to 78°) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Pre-operative Functional Parameters using OPS™ Planning.

| Pre-operative Parameter | Mean (o) | Range (o) |

|---|---|---|

| Supine Pelvic Tilt (range) | 4.7 (−31.0 to 21.3) | 52.3 |

| Standing Pelvic Tilt (range) | −0.3 (−32.8 to 23.2) | 56.0 |

| Flex-Seated Pelvic Tilt (range) | −0.7 (−41.9 to 32.4) | 74.3 |

| Pelvic Incidence (range) | 54.4 (24.3–87.6) | 63.3 |

| Lumbar Flexion (range) | 43.1 (0.0–78.4) | 78.4 |

| Supine-to-Stand | −5.1 (−23.6 to 8.8) | 32.4 |

| Supine-to-Flex Seated | −5.4 (−48.1 to 26.1) | 74.2 |

Targeted cup orientation angles calculated consisted of a mean inclination angle of 40° (range, 34 to 49) and mean anteversion angle of 24° (range, 3.5 to 39) among all patients (Table 2).

Table 2.

Targeted Parameters using OPS™ Planning.

| Targeted Parameter | Mean (o) | Range (o) |

|---|---|---|

| Planned Inclination Supine (range) | 38.8 (35.0–43.2) | 8.2 |

| Planned Anteversion Supine (range) | 20.2 (10.5–28.7) | 18.2 |

| Planned Inclination Referenced to APP (range) | 40.2 (34.1–49.3) | 15.2 |

| Planned Anteversion Referenced to APP (range) | 24.3 (3.5–39.4) | 35.9 |

73 patients (4.9%) required the use of dual-mobility cups due to adverse spinopelvic mobility or severe sagittal spinal imbalance. Only 56% of the dynamically planned cups were within the LSZ (p < 0.05, Fig. 4). Mean inclination and anteversion difference between dynamic and LSZ was 1.3° (range, 0° to 12°) and 8.9° (range, 0° to 25°), respectively (Table 3).

Fig. 4.

The distribution of inclination and anteversion of the planned OPS™ Acetabular Cups in comparison to the Lewinnek Safe Zone (LSZ). 56% of the dynamically planned acetabular cups were within the LSZ.

Table 3.

Targeted OPS versus Lewinnek cup positioning.

| Parameter | Mean (o) | Range (o) |

|---|---|---|

| Inclination Difference (range) | 1.3 (0.0–11.8) | 11.8 |

| Anteversion Difference (range) | 8.9 (0.0–25.2) | 25.2 |

| Percentage of OPS Cups Placed in Lewinnek Zone | 56% | |

Only 6/1500 (0.4%) of all implanted cups dislocated postoperatively. All dislocations were in acetabular cups positioned in the LSZ. Of these 6 dislocations, 5 patients either had malpositioned acetabular components outside of the proposed OPS™ target zone or were extremely high risk due to spinopelvic pathology but did not receive a dual mobility bearing (Table 4).

Table 4.

Spinopelvic parameters and risk factors for the patients who suffered from postoperative dislocation.

| Gender | Age at Surgery | Adverse spinopelvic mobility |

Risk factors |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Supine to stand PT (°) | Stand to seated PT (°) | Standing PT (°) | LF (°) | PI-LL mismatch (°) | |||

| Dislocator 1 | M | 68 | −10.8 | 1.1 | −7.9 | 18.1 | 19.6 |

| Dislocator 2 | M | 84 | −18.4 | 26.8 | −10.4 | 26.5 | 1.6 |

| Dislocator 3 | F | 40 | −2.2 | −7.2 | 8.6 | 52.3 | −19.1 |

| Dislocator 4 | F | 50 | −1.0 | 11.8 | −2.4 | 46.7 | 5.3 |

| Dislocator 5 | F | 72 | −13.3 | −1.0 | −14.1 | 23.5 | 23.1 |

| Dislocator 6 | F | 76 | −8.9 | 14.5 | −4.1 | 31.2 | 20.4 |

4. Discussion

The purpose of our study was to compare pre-operative acetabular cup parameters using a novel dynamic imaging sequence to the LSZ and describe dislocation rates of this novel dynamic imaging sequence. Only 56% of hips that underwent dynamic pre-operative acetabular cup planning were within the LSZ. Out of the 1500-patient cohort, there were 6 dislocation events (0.4%) with all dislocations occurring in cups positioned within the LSZ. Upon further analysis of the patients who dislocated, however, preoperative planning software data revealed that 5 out of the 6 patients who suffered from postoperative dislocations had either an incorrectly positioned cup, adverse spinopelvic mobility, or severe sagittal spinal imbalance making them higher risk (Table 4). Adverse spinopelvic mobility is defined by a change in sagittal pelvic tilt causing a well-oriented acetabular cup to move out of the functional safe zone in hip extension or flexion, while severe sagittal spinal imbalance is defined by a difference in pelvic incidence and lumbar lordosis greater than 20°. Additionally, failures to execute cup placement within the OPS™ proposed safe target resulted in component malpositioning for 1 patient who dislocated, due to increased impingement risk. There were also 4 high-risk patients with adverse spinopelvic mobility or sagittal spinal imbalance who should have received a dual mobility bearing to compensate for their elevated risk of instability, though none of them did.

Therefore, despite an overall dislocation rate of 0.4% associated with utilization of the OPS™ technology, more important to consider is the fact that cup placement outside of the functional predicted safe zone and the decision not to utilize dual mobility bearings in extremely high-risk patients with adverse spinopelvic mobility or sagittal spinal imbalance may have inflated these results. Component malpositioning outside of the proposed OPS™ target zone occurred in 1 patient while 4 patients had adverse spinopelvic mobility or sagittal spinal imbalance and were higher risk, yet did not receive a dual mobility bearing that would now be considered appropriate in such patients. When factoring in all of these considerations, the actual dislocation rate associated with OPS™ drops to 1/1,500, or 0.07%. Preoperative planning with OPS™ can assist surgeons in planning acetabular cup positioning and bearing choice, with the highest risk patients warranting dual mobility implants. Additionally, this technology can be utilized to improve intraoperative precision, which is necessary for surgeons to achieve the desired cup position. Despite all THAs in this study being performed with the posterior approach, OPS™ technology has been demonstrated to be highly effective in the direct anterior approach as well and thus these results are likely not approach dependent.29 Our study also demonstrates that historical target parameters for cup inclination and anteversion significantly differ to target values obtained with the use of functional imaging. Understanding the individual spinopelvic motion for each patient allows for more accurate placement of the acetabular component, which may help to reduce the risk of dislocation, premature wear and squeaking of bearing surfaces, and improve functional outcomes.

Previous studies have attempted to improve the predictive efficacy of coronal safe zones.30, 31, 32 Originally, Elkins and colleagues proposed narrowing the coronal safe zone inclination and anteversion from 37o-460 and 12o-220, respectively.30 Tezuka et al. reported that using this method resulted in fewer hips implanted into the narrow safe zone but no change in the number of hips in the functional safe zone.32 As a result, the authors believe that the size and shape of coronal safe zones are not predictive of safety. The large range of pre-operative acetabular cup parameters seen in our study further suggest that coronal safe zones do not correlate with improved stability. Pre-operative planning in our study utilized dynamic, individualized parameters to determine the optimal acetabular cup position for each patient, regardless of the LSZ. The low dislocation rate with dynamic imaging seen in our cohort further expands the claim that the only true “safe zones” are functional ones. Therefore, variations between patient morphology and the complex interplay of the hip-spine-pelvis necessitate acetabular component positioning with individualized, patient-specific safe zones.

Although THA surgeons have aimed to orient implants based on the LSZ, dislocations still occur.7,11,33 Reize et al. previously reported that 58% of their dislocations were within both cup inclination and anteversion safe zones.34 Esposito and colleagues described a dislocation rate of 2.1% in 7040 patients with 57% of dislocated hips positioned in the LSZ.8 More recently, Tezuka et al. used computer navigation to determine whether implanting cups within the LSZ resulted in cup placement within their defined functional safe zone.32 They found that 85.8% of acetabular cups implanted within the previously described LSZ were within the functional safe zone, meaning 14.2% of cups within the LSZ were not within the functional safe zone. Although the authors did not report on the proportion of patients who dislocated, their results provide insight as to why hips continue to dislocate despite having “normal” cup angles. Of the 1500 THAs in our study, only 56% of dynamic pre-operatively planned acetabular cups were also within the LSZ, with a dislocation rate of only 0.5% for the total cohort. More important to consider is that all the dislocations occurred in cups that were within the LSZ. As such, our data shows that abandoning the historical target parameters for cup inclination and anteversion for functional, patient-specific safe zones results in low rates of dislocation in THA.

Our study is not without limitations. This was a retrospective, non-randomized analysis without a control group and thus, may be subject to inherent bias. However, all data was collected prospectively, all measurements were performed according to a standardized protocol, and all THAs were performed in a currently accepted surgical manner by board-certified, fellowship-trained orthopaedic surgeons. Additionally, the patient sample was not homogenous, as high-risk patients with spinopelvic pathology received dual mobility cups, which offer more stability and thus could affect the results. Nevertheless, this study aimed to demonstrate that achieving very low dislocation rates for all patients, regardless of dislocation risk, can be attained with judicious utilization of dual mobility cups in primary THA for the highest risk patients in conjunction with patient-specific safe zones for cup positioning. Furthermore, this study did not evaluate the individual impact of femoral stem position and the combined effect of femoral stem and acetabular cup orientation on postoperative dislocations. Future studies will include an analysis of the effect of additional parameters including surgical approach, surgeon experience, patient demographics, postoperative limb length discrepancy, femoral head size, femoral stem position, and neurological conditions, among others.35 Despite these limitations, our data elucidates the ability of functional imaging to reduce complications in THA, regardless of cup positioning within the LSZ.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that utilization of patient-specific safe zones results in low rates of dislocation in THA, regardless of cup positioning within the LSZ. Previously described target parameters for cup inclination and anteversion significantly differ to target values obtained with the use of functional imaging. Understanding the individual spinopelvic motion for each patient allows for more accurate placement of the acetabular component, which may help to reduce the complications and improve functional outcomes. THA surgeons should seek to transition away from historical target parameters (i.e. LSZ) for cup inclination and anteversion toward patient-specific functional safe zones. Future studies are needed to validate the utility of patient-specific safe zones in reducing instability.

Funding

The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work.

Availability of data and material

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author., A.K·S., upon reasonable request.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2013.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was waived from all patients included in this study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable; no patient images, identifiers or identifiable individual data were used in this study.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Abhinav K. Sharma: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, preparation, Manuscript Revision. Zlatan Cizmic: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. Douglas A. Dennis: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Stefan W. Kreuzer: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Michael A. Miranda: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Jonathan M. Vigdorchik: Conceptualization, Data curation, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of competing interest

Abhinav K. Sharma, M.D., declares that he has no conflict of interest. Zlatan Cizmic, M.D., declares that he has no conflict of interest. Douglas A. Dennis, M.D., reports receiving personal fees from Depuy Synthes and Corin Group, stock options in Joint Vue, research support from Depuy Synthes, Corin Group, Porter Adventist Hospital, royalties from Wolters Kluwer publishing, and being a board members for Joint Vue. Stefan W. Kreuzer, M.D., reports receiving personal fees from Corin Group, Smith and Nephew, Medtronic, Pacira, Brain Lab, Intellijoint Surgical, Swift Path, Think Surgical, Shukla, Zimmer/Biomet, and Pulse, stock options in Innovative Orthopedic Technologies, INOV8 Orthopedics, INOV8 Surgical, INOV8 Healthcare, K and S Solutions, Orthosensor, Argentum Medical (Silverlon), First Street Surgical Hospital, Texo-Venture, Employers Direct, Alpoza, research support from Corin Group, Smith and Nephew, Depuy, Think Surgical, being a medical/orthopaedic publications governing board member for Journal of Arthroplasty, and being a board member for ISTA, ICJR, Memorial Bone & Joint Research Foundation, Surgical Care Affiliates (Medical Advisory Board), Employers Direct (Medical Advisory Board). Michael A. Miranda, D.O., reports receiving personal fees from Corin Group. Jonathan M. Vigdorchik, M.D., reports receiving personal fees from Corin Group and has received research funding from Corin Group.

Acknowledgements

The authors have no acknowledgements to make for this study.

References

- 1.Lewinnek G.E., Lewis J.L., Tarr R., Compere C.L., Zimmerman J.R. Dislocations after total hip-replacement arthroplasties. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1978;60(2):217–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abdel M.P., Roth P von, Jennings M.T., Hanssen A.D., Pagnano M.W. What safe zone? The vast majority of dislocated THAs are within the Lewinnek safe zone for acetabular component position. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2016;474(2):386–391. doi: 10.1007/s11999-015-4432-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bozic K.J., Katz P., Cisternas M., Ono L., Ries M.D., Showstack J. Hospital resource utilization for primary and revision total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(3):570–576. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.02121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Callanan M.C., Jarrett B., Bragdon C.R. The John Charnley Award: risk factors for cup malpositioning: quality improvement through a joint registry at a tertiary hospital. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(2):319–329. doi: 10.1007/s11999-010-1487-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DelSole E.M., Vigdorchik J.M., Schwarzkopf R., Errico T.J., Buckland A.J. Total hip arthroplasty in the spinal deformity population: does degree of sagittal deformity affect rates of safe zone placement, instability, or revision? J Arthroplasty. 2017;32(6):1910–1917. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2016.12.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karuppal R. Biological fixation of total hip arthroplasty: facts and factors. J Orthop. 2016;13(3):190–192. doi: 10.1016/j.jor.2016.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scior W., Kafchitsas K., Drees P., Graichen H. Hip arthroplasty - all problems solved or still place for improvement? J Orthop. 2016;13(4):327–330. doi: 10.1016/j.jor.2016.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Esposito C.I., Gladnick B.P., Lee Y. Cup position alone does not predict risk of dislocation after hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2015;30(1):109–113. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2014.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harrison C.L., Thomson A.I., Cutts S., Rowe P.J., Riches P.E. Research synthesis of recommended acetabular cup orientations for total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(2):377–382. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2013.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Higgins B.T., Barlow D.R., Heagerty N.E., Lin T.J. Anterior vs. posterior approach for total hip arthroplasty, a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Arthroplasty. 2015;30(3):419–434. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2014.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Howie D.W., Holubowycz O.T., Middleton R., Large Articulation Study Group Large femoral heads decrease the incidence of dislocation after total hip arthroplasty: a randomized controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(12):1095–1102. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.K.00570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peter R., Lübbeke A., Stern R., Hoffmeyer P. Cup size and risk of dislocation after primary total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2011;26(8):1305–1309. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2010.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dutta A., Nutt J., Slater G., Ahmed S. Review: trunnionosis leading to modular femoral head dissociation. J Orthop. 2021;23:199–202. doi: 10.1016/j.jor.2021.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Warnock J., Hill J., Humphreys L., Gallagher N., Napier R., Beverland D. Independent restoration of femoral and acetabular height reduces limb length discrepancy and improves reported outcome following total hip arthroplasty. J Orthop. 2019;16(6):483–488. doi: 10.1016/j.jor.2019.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DiGioia A.M., Jaramaz B., Colgan B.D. Computer assisted orthopaedic surgery. Image guided and robotic assistive technologies. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1998;354:8–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lazennec J.Y., Brusson A., Rousseau M.A. Lumbar-pelvic-femoral balance on sitting and standing lateral radiographs. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2013;99(1 Suppl):S87–S103. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2012.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lazennec J.-Y., Charlot N., Gorin M. Hip-spine relationship: a radio-anatomical study for optimization in acetabular cup positioning. Surg Radiol Anat. 2004;26(2):136–144. doi: 10.1007/s00276-003-0195-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bedard N.A., Martin C.T., Slaven S.E., Pugely A.J., Mendoza-Lattes S.A., Callaghan J.J. Abnormally high dislocation rates of total hip arthroplasty after spinal deformity surgery. J Arthroplasty. 2016;31(12):2884–2885. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2016.07.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heckmann N., McKnight B., Stefl M., Trasolini N.A., Ike H., Dorr L.D. Late dislocation following total hip arthroplasty: spinopelvic imbalance as a causative factor. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2018;100(21):1845–1853. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.18.00078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miki H., Kyo T., Kuroda Y., Nakahara I., Sugano N. Risk of edge-loading and prosthesis impingement due to posterior pelvic tilting after total hip arthroplasty. Clin Biomech. 2014;29(6):607–613. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2014.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kanawade V., Dorr L.D., Wan Z. Predictability of acetabular component angular change with postural shift from standing to sitting position. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(12):978–986. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.M.00765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wan Z., Malik A., Jaramaz B., Chao L., Dorr L.D. Imaging and navigation measurement of acetabular component position in THA. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467(1):32–42. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0597-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Legaye J., Duval-Beaupère G., Hecquet J., Marty C. Pelvic incidence: a fundamental pelvic parameter for three-dimensional regulation of spinal sagittal curves. Eur Spine J. 1998;7(2):99–103. doi: 10.1007/s005860050038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Langston J., Pierrepont J., Gu Y., Shimmin A. Risk factors for increased sagittal pelvic motion causing unfavourable orientation of the acetabular component in patients undergoing total hip arthroplasty. The Bone & Joint Journal. 2018;100-B(7):845–852. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.100B7.BJJ-2017-1599.R1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Buckland A.J., Fernandez L., Shimmin A.J., Bare J.V., McMahon S.J., Vigdorchik J.M. Effects of sagittal spinal alignment on postural pelvic mobility in total hip arthroplasty candidates. J Arthroplasty. 2019;34(11):2663–2668. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2019.06.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Esposito C.I., Carroll K.M., Sculco P.K., Padgett D.E., Jerabek S.A., Mayman D.J. Total hip arthroplasty patients with fixed spinopelvic alignment are at higher risk of hip dislocation. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33(5):1449–1454. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2017.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Innmann M.M., Merle C., Phan P., Beaulé P.E., Grammatopoulos G. How can patients with mobile hips and Stiff lumbar spines Be identified prior to total hip arthroplasty? A prospective, diagnostic cohort study. J Arthroplasty. 2020;35(6S):S255–S261. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2020.02.029. S088354032030190X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vigdorchik J.M., Sharma A.K., Dennis D.A., Walter L.R., Pierrepont J.W., Shimmin A.J. The majority of total hip arthroplasty patients with a Stiff spine do not have an instrumented fusion. J Arthroplasty. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2020.01.031. S0883540320300681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kreuzer S., Madurawe C., Pierrepont J., Jones T. Accuracy of ct templating for direct anterior approach total hip arthroplasty. Orthopaedic Proceedings The British Editorial Society of Bone & Joint Surgery. 2020;102-B(suppl P_1) 112–112. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Elkins J.M., Callaghan J.J., Brown T.D. The 2014 Frank Stinchfield Award: the ‘landing zone’ for wear and stability in total hip arthroplasty is smaller than we thought: a computational analysis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473(2):441–452. doi: 10.1007/s11999-014-3818-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Murphy W.S., Yun H.H., Hayden B., Kowal J.H., Murphy S.B. The safe zone range for cup anteversion is narrower than for inclination in THA. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2018;476(2):325–335. doi: 10.1007/s11999.0000000000000051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tezuka T., Heckmann N.D., Bodner R.J., Dorr L.D. Functional safe zone is superior to the Lewinnek safe zone for total hip arthroplasty: why the Lewinnek safe zone is not always predictive of stability. J Arthroplasty. 2019;34(1):3–8. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2018.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Amlie E., Høvik Ø., Reikerås O. Dislocation after total hip arthroplasty with 28 and 32-mm femoral head. J Orthop Traumatol. 2010;11(2):111–115. doi: 10.1007/s10195-010-0097-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reize P., Geiger E.V., Suckel A., Rudert M., Wülker N. Influence of surgical experience on accuracy of acetabular cup positioning in total hip arthroplasty. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ) 2008;37(7):360–363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shah S.M. Survival and outcomes of different head sizes in primary total hip arthroplasty. J Orthop. 2019;16(6):A1–A3. doi: 10.1016/j.jor.2019.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author., A.K·S., upon reasonable request.