Abstract

Lentinula edodes (shiitake mushrooms) is heavily affected by the infection of Trichoderma atroviride, causing yield loss and decreases quality in shiitake mushrooms. The selection and breeding of fungal-resistant L. edodes species are an important approach to protecting L. edodes from T. atroviride infection. Herein, a highly resistant L. edodes strain (Y3334) and a susceptible strain (Y55) were obtained by using a resistance evaluation test. Transcriptome analyses and qRT-PCR detection showed that the expression level of LeTLP1 (LE01Gene05009) was strongly induced in response to T. atroviride infection in the resistant Y3334. Then, LeTLP1-silenced and LeTLP1-overexpression transformants were obtained. Overexpression of LeTLP1 resulted in resistance to T. atroviride. Compared with the parent strain Y3334, LeTLP1-silenced transformants had reduced resistance relative to T. atroviride. Additionally, the LeTLP1 protein (Y3334) exhibited significant antifungal activity against T. atroviride. These findings suggest that overexpression of LeTLP1 is a major mechanism for the resistance of L. edodes to T. atroviride. The molecular basis provides a theoretical basis for the breeding of resistant L. edodes strains and can eventually contribute to the mushroom cultivation industry and human health.

Keywords: Lentinula edodes, Trichoderma atroviride, resistance mechanism, LeTLP1

1. Introduction

Lentinula edodes (also known as Xiang Gu or shiitake), a widely cultivated edible mushroom, is famous for its nutritional properties and pharmacological effects, such as its hypocholesterolemic, anti-inflammatory, antitumor, and neuroprotective effects [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8]. The cultivation, production, and consumption of shiitake are important nowadays not only in Asian countries but also in western countries. The white-rot basidioycete L. edodes grows on the wood logs, and it is now cultivated on the sterilized sawdust-based substrates [1,9,10]. In practice, making use of sawdust-based cultivation as a replacement for natural logs has contributed to the expansion of the production and consumption of L. edodes [11]. However, the cultivation of L. edodes is severely affected by the infection of Trichoderma spp., which overgrows mushroom mycelia and kills them, resulting in a reduction in the mushroom yield [12,13]. As a result, the green mold disease induced by Trichoderma spp. on L. edodes severely limits the sustainable development of the mushroom industry.

The main Trichoderma species affecting L. edodes in China are T. harzianum, T. atroviride, T. viride, T. longibrachiatum, T. polysporum, T. pleuroticola, and T. oblongisporum [12,13,14,15]. Among them, T. harzianum is the most general and widespread pathogen in mushrooms [14,16,17,18]. The mycelia of T. atroviride possess a stronger capacity of overgrowth on L. edodes, and they attack the mycelium of L. edodes [12]. The other five species—namely, T. viride, T. longibrachiatum, T. polysporum, T. pleuroticola, and T. oblongisporum—are rare in shiitake logs [12,19,20]. Given the widespread growth of T. atroviride, it is crucial to protect L. edodes from being infected by T. atroviride in order to promote the yield and quality of L. edodes.

Fungicides such as carbendazim, thiabendazole, and benomyl have been widely applied for the control of the green mold disease caused by Trichoderma in mushrooms [21,22]. Additionally, prochloraz and metrafenone might also be recommended for the control of green mold disease in mushrooms [13]. However, the increasing fungicides resistance level in fungi and the occurrence of fungicide residues may cause a negative impact on the health of living organisms. This has triggered a strong interest in the development of alternative methods for fungal control [23,24]. Although several studies on the screening of resistant L. edodes strains have been conducted by many researchers [12,16,18,25], the effects of Trichoderma spp. on L. edodes are still not well documented. Previous studies revealed that laccase expression was increased in L. edodes when it interacted with Trichoderma spp. [26,27]. L. edodes secreted lignocellulose, which might play a key role in the resistance to Trichoderma [27]. In addition, other edible basidiomycete mushrooms produce defense proteins, known as ribotoxin-like proteins (e.g., ageritin), which inhibit the growth of Trichoderma through the damage to fungal ribosomes and the consequent inhibition of protein synthesis [28]. However, the molecular basis of the resistance of L. edodes to T. atroviride is largely unknown.

Herein, 56 strains of L. edodes were collected, and the resistance levels of these strains against T. atroviride were evaluated. Based on a systematic resistance evaluation test, two typical strains (the highly resistant strain Y3334 and the susceptible strain Y55) were obtained. Furthermore, the molecular basis of the resistance of L. edodes to T. atroviride is elaborated upon. This study provides a theoretical basis for the breeding of resistant L. edodes strains and will be beneficial to the promotion of the development of the mushroom cultivation industry.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. L. edodes and T. atroviride Strains

The 56 strains of L. edodes (Table S1) were collected and identified by the Institute of Applied Mycology, Huazhong Agriculture University [29,30,31]. The T. atroviride strain 92-1 was isolated and identified from logs with green mold disease in Suizhou, Hubei [12,30].

2.2. Evaluation of the Resistance of L. edodes to T. atroviride

The confrontation assay method was used to test the resistance levels of the 56 L. edodes strains against T. atroviride with a dual culture of each L. edodes strain and the T. atroviride strain 92-1 on PDA plates. Mycelial plugs (8 mm in diameter) were obtained from the 7 day old colonies of L. edodes strains and were inoculated onto PDA at 1 cm from the edge of Petri plates that were 9 cm in diameter at 25 °C in a dark environment. Eight days later, mycelial plugs (8 mm in diameter) of T. atroviride strain 92-1 were inoculated onto the PDA on the opposite side (1 cm away from the plate’s edge). The confrontation conditions of T. atroviride strain 92-1 against the mycelial growth of L. edodes were observed. Additionally, the infection rates (LT:LL) were calculated as described by Wang et al. (2018) [32]. Each test was repeated thrice.

2.3. Responses of the Highly Resistant and Susceptible L. edodes Strains to Infection with T. atroviride

Highly resistant (Y3334) and the susceptible (Y55) L. edodes strains were chosen as representative strains. The confrontations of the highly resistant (Y3334) and the susceptible (Y55) L. edodes strains with T. atroviride (92-1) were observed at 24, 48, 72, 96, and 120 h post-infection (hpi), as well as 30 days post-infection (dpi). Furthermore, the changes in the mycelium of L. edodes that was treated with T. atroviride were observed via SEM (scanning electron microscopy) at 24 and 48 hpi.

2.4. Comparative Transcriptomics Analysis

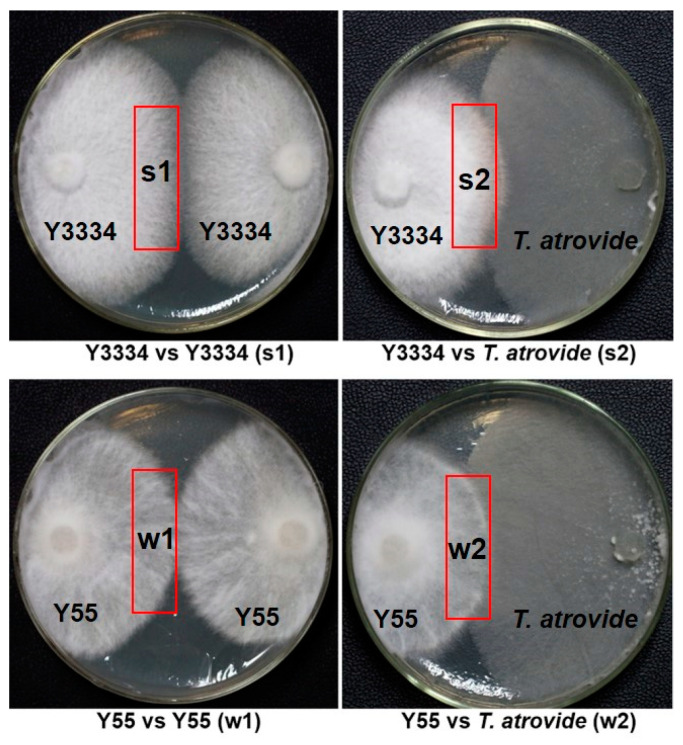

The highly resistant strain Y3334 and the susceptible strain Y55 were grown on PDA plates that were covered with cellophane at 25 °C in a dark environment. The mycelia of L. edodes were collected when the T. atrovide strain 92-1 had made contact with the L. edodes strain for 24 h. As controls, the Y3334 strain and Y55 strain of L. edodes were confronted with themselves. Four mycelia samples (s1, s2, w1, and w2) of the peripheral hyphal zones from L. edodes at the AC stage (after contact for 24 h) were collected (Figure 1) and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen. There were three replicates of each sample. In total, twelve libraries that represented the highly resistant and susceptible L. edodes strains’ responses to T. atrovide or themselves were constructed for transcriptome sequencing (Illumina HiSeq).

Figure 1.

Collection of four mycelial samples (s1, s2, w1, and w2) of peripheral hyphal zones from L. edodes at the AC (after contact for 24 h) stage. The highly resistant (Y3334) and susceptible (Y55) L. edodes strains were grown on PDA plates that were covered with cellophane at 25 °C in a dark environment. The resistant and susceptible samples of the mycelia of L. edodes (s2, w2) were harvested after the T. atrovide strain 92-1 had made contact with the L. edodes strains for 24 h. As controls, the Y3334 strain and Y55 strain of L. edodes were confronted with themselves. The mycelial samples of resistant and susceptible L. edodes (s1 and w1) were harvested after contact for 24 h; s1 represents Y3334 vs. Y3334; s2 represents Y3334 vs. T. atrovide strain 92-1; w1 represents Y55 vs. Y55; w2 represents Y55 vs. T. atrovide strain 92-1. The red square represents the sampling location.

2.4.1. RNA Extraction, Library Preparation, and Sequencing

Mycelial samples were ground into fine powders in liquid nitrogen. Total RNAs were extracted using RNAiso Plus (TaKaRa, Dalian, China) and Fruit-mateTM for the RNA Purification Kit (TaKaRa, Dalian, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA concentrations and RNA integrity numbers were determined by using agarose gel electrophoresis and an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Carpinteria, CA, USA), respectively. Amounts of 20 μg of RNA were equally isolated from mycelia for mRNA isolation, cDNA library construction, and sequencing according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). The twelve libraries were sequenced through paired-end sequencing on an Illumina Hiseq 4000 sequencer (BGI). Sequencing services were provided by the Beijing Genomics Institute (BGI)-Shenzhen, Wuhan, China.

2.4.2. Transcriptome Data Analysis

Twelve sets of raw data of all samples were pre-treated with FastQC, filtered, and trimmed via Trimmonmatic (parameter, PE and phred33). The indices were constructed via bowtie2 according to the L. edodes genome files (L. edodes W1-26 genome v1.0: http://shiitakegdb.chenlianfu.com/ accessed on 15 November 2019), followed by mapping of the RNA-seq reads to the reference genome of L. edodes with Tophat2 by using the default settings [33]. Subsequently, Samtools was used to create SAM files for the bam files [34]. Integrated and comprehensive transcript sets were obtained via Cufflinks and Cuffmerge. We ran the Cuffdiff function to find differentially expressed genes and transcripts in the samples using the default settings [33]. One-way ANOVA was applied, and a step-up FDR p-value was calculated to sort out the statistically significant differentially expressed genes (DEGs) by filtering the data at p < 0.05 (FDR) and with >2-fold change in the expression. The GO term enrichment and functional categorization for biological processes and cellular and molecular functions were carried out using Gene Ontology at the BGI databank.

2.5. qRT-PCR

The L. edodes mycelial samples for the RNA-seq analysis were also used for qRT-PCR. Gene-specific primers were designed using the Primer Premier 5.0 [35] for the target genes as well as the reference actin-1 gene (Table S2). The relative expression levels of the ten selected genes (Table S2) were calculated by using the 2−ΔΔCT method [36].

2.6. Construction of LeTLP1-Overexpression and LeTLP1-Silencing Vectors and Fungal Transformation

The LeTLP1-overexpression vector was constructed by following the published protocols described by Yan et al. (2019) [37], with minor modifications. The CaMV 35S promoter of pCAMBIA1300 was replaced with the Legpd (L. edodes glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) promoter in order to produce the pCAMBIA1300-g vector. The Legpd promoter sequence was PCR amplified from the DNA of L. edodes strain W1-26 with the O-Legpd Promotor-F and O-Legpd Promotor-R primers (Table 1). The full length of the LeTLP1 gene was amplified from L. edodes strain Y3334 cDNA with the O-LeTLP1-F and O-LeTLP1-R primers (Table 1), which contained the homologous arms, and then ligated into the pCAMBIA1300-g vector digested with EcoRI and KpnI in order to generate the overexpression vector pCAMBIA1300-o-LeTLP. All constructs were assessed by sequencing analysis and transferred into L. edodes strain Y55 through A. tumefaciens EHA105 infection.

Table 1.

Sequence information of the primers used for the construction of LeTLP1-overexpression and LeTLP1-silencing vectors.

| Primer Name | Primer Sequence (5′ to 3′) |

|---|---|

| O-Legpd Promotor-F | catATTCAAGCAGTCAATGGATTGGA |

| O-Legpd Promotor-R | tctagaggatccccgggtaccCGAAGTTTGAGGTGGTTGCG |

| O-LeTLP1-F | ccacctcaaacttcggaattcTCAGGGGCAAAATGTAACAGCATA |

| O-LeTLP1-R | ccattgactgcttgaatATGATGAAGAATTCTATCATTATCTCTGC |

| R-LeTLP1-F | agctcttcacgGATCCACTGCAGCAGTTGGG |

| R-LeTLP1-R | tgcttgaatTGGCCGGCAATCTTCACG |

| R-Leactin-F | ccacctcaaacttcggaattcGCAGTATTTATACCTACGGAGC |

| R-Leactin-R | cagtggatcCGTGAAGAGCTGCGAGTGTTG |

For the construction of the LeTLP1-silencing vector, a 500-bp antisense fragment from LeTLP1 was amplified with the R-LeTLP1-F and R-LeTLP1-R primers (Table 1) from the cDNA of L. edodes. The Leactin promoter fragment was amplified with the R-Leactin-F and R-Leactin-R primers (Table 1) from the cDNA of L. edodes. Then, the Leactin promoter fragment, LeTLP1 antisense fragment, and the aforesaid digested pCAMBIA1300-g vector were ligated in order to generate the silencing vector pCAMBIA1300-Ri-LeTLP. All constructs were assessed through sequencing analysis and transferred into L. edodes strain Y3334 through A. tumefaciens EHA105 infection.

The ten transformants were selected randomly to analyze their over-expression and silencing efficiency with qRT-PCR by using the primers for LeTLP1 (LE01Gene05009) and by normalizing to the actin-1 gene by using the primers for the actin-1 gene (Table S2). The relative expression levels were calculated with the 2−ΔΔCT method [36]. Three replicates for each isolate were analyzed, and the experiment was independently repeated three times.

2.7. Evaluation of the Level of Resistance against T. atroviride in LeTLP1-Overexpression and LeTLP1-Silenced Transformants

In order to test the effects of LeTLP1 over-expression and silencing on the resistance of L. edodes against T. atroviride, the confrontation assays were undertaken according to the method presented in Section 2.2. The confrontations of the LeTLP1 overexpression transformants (Y55_OE_3 and Y55_OE_10), silencing transformants (TLP1-Ri-3 and TLP1-Ri-8), and their parent isolates against T. atroviride (92-1) were observed on the 15th day after inoculation with T. atroviride in order to evaluate the level of the resistance of the transformants against T. atroviride, with five replicates for each group. Infection rates (LT:LL) were also calculated in order to evaluate the effects of T. atroviride on the mycelia of L. edodes [32].

2.8. Prokaryotic Expression of LeTLP1 and LeTLP (Y55)

For prokaryotic expression, the fragments (Figure S2) of LeTLP1 and LeTLP (Y55) cloned from Y3334 and Y55 fused with a 6 × His-tag were ligated into the plasmid pET32a (Novagen, WI, USA). The pET32a plasmids harboring LeTLP1 and LeTLP (Y55) were transferred into the E. coli BL21(DE3) strain (Tiangen Biotech, Beijing, China). Then, each colony was induced in fresh LB broth with 40 μM isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG). For purification of recombinant proteins, cultures were harvested after 16 h of induction at 18 °C. Suspensions were disrupted by squeezing in lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, 200 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.4). After centrifugation (7000× g, 4 °C, 10 min), the recombinant proteins in the E. coli lysate supernatant were purified using a nickel-affinity chromatography column (Yeasen, Shanghai, China) with an imidazole gradient elution. Recombinant proteins were verified with sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE).

2.9. Assays of the Antifungal Activity of LeTLP1

The antifungal activity of LeTLP1 was measured by using the paper disc method described by Imtiaj and Lee (2007) [38]. Agar discs taken from 10 day old cultures of T. atroviride strain 92-1 were placed in the center of the Petri plates. The paper discs of Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), sterilized water, 20 μg of LeTLP (Y55), 5 μg of LeTLP1, 10 μg of LeTLP1, and 20 μg of LeTLP1 were separately placed at 1 cm from the edge of the Petri plates. As a control, agar discs of T. atroviride strain 92-1 were placed in the same manner on a fresh PDA plate with the paper discs of Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) and sterilized water. The inhibition rates (the percent inhibition of mycelial growth—PIMG) were calculated as described in Imtiaj and Lee (2007) [38]. The experiments were independently repeated three times.

2.10. Statistical Analysis

Following a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), Duncan’s multiple range test was used to evaluate significant differences in the gene expression levels, infection rates (LT:LL), and inhibition rates (the percent inhibition of mycelial growth—PIMG).

3. Results

3.1. Evaluation of Lentinula edodes Strains That Were Resistant to Trichoderma atrovide

The resistance levels of the 56 strains (Table S1) of L. edodes against T. atroviride were evaluated by using the resistance evaluation test (Table 2). The results revealed that the 56 L. edodes strains (21 cultivated strains and 35 wild strains) could be divided into a highly resistant group (Y3334, Y29, Y1515, Y121, and c67), medium-resistant group (++ labeled strains in Table 2), and susceptible group (Y55). Among them, the highly resistant strain Y3334 and the susceptible strain Y55 were chosen to be representative for the subsequent research on the resistance mechanism of L. edodes against T. atroviride.

Table 2.

Evaluation of the resistance of L. edodes strains to T. atrovide.

| Strains | AC about 7 Days | AC about 30 Days | Strains | AC about 7 Days | AC about 30 Days |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c2 | + | ++ | Y30 | + | ++ |

| c6 | + | ++ | Y37 | + | ++ |

| c9 | + | ++ | Y39 | + | ++ |

| c10 | + | ++ | Y51 | + | ++ |

| c20 | + | ++ | Y55 | − | − |

| c23 | + | ++ | Y70 | + | ++ |

| c27 | + | ++ | Y76 | + | ++ |

| c28 | + | ++ | Y78 | + | ++ |

| c31 | + | ++ | Y79 | + | ++ |

| c42 | + | ++ | Y84 | + | ++ |

| c47 | + | ++ | Y88 | + | ++ |

| c48 | + | ++ | Y89 | + | ++ |

| c49 | + | ++ | Y91 | + | ++ |

| c50 | + | ++ | Y94 | + | ++ |

| c51 | + | ++ | Y100 | + | ++ |

| c64 | + | ++ | Y104 | + | ++ |

| c67 | + | +++ | Y110 | + | ++ |

| c82 | + | ++ | Y111 | + | ++ |

| c85 | + | ++ | Y113 | + | ++ |

| c87 | + | ++ | Y118 | + | ++ |

| c88 | + | ++ | Y121 | + | +++ |

| Y1 | + | ++ | Y234 | + | ++ |

| Y5 | + | ++ | Y358 | + | ++ |

| Y7 | + | ++ | Y366 | + | ++ |

| Y8 | + | ++ | Y1515 | + | +++ |

| Y11 | + | ++ | Y1518 | + | ++ |

| Y14 | + | ++ | Y3334 | + | +++ |

| Y29 | + | +++ | Y3353 | + | ++ |

AC means after contact; − represents susceptible; + represents the low resistance level; ++ represents the medium resistance level; +++ represents the high resistance level.

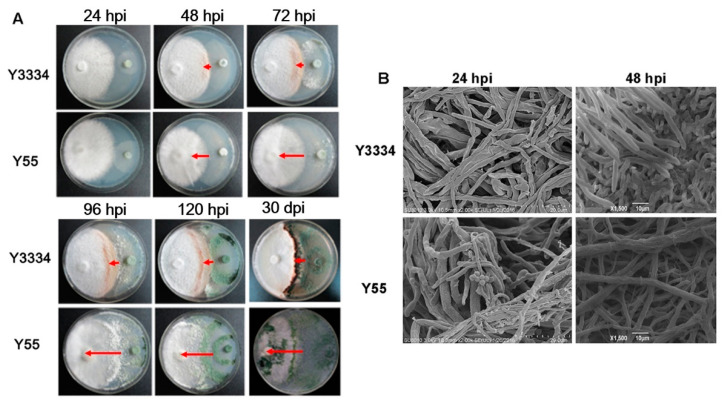

3.2. Significant Differences in the Responses of the Highly Resistant and Susceptible L. edodes strains to T. atroviride Infection

On the PDA plate, significant differences were shown in the interactions of the highly resistant strain Y3334 and susceptible strain Y55 with T. atroviride at 24, 48, 72, 96, and 120 h post-infection (hpi) and 30 days post-infection (dpi), respectively (Figure 2A). Notably, the infection rates (LT:LL) were significantly lower in the confrontation of the highly resistant strain Y3334 with T. atroviride than for the susceptible strain Y55 at 24, 48, 72, 96, and 120 h, as well as 30 d (Figure 2A). Furthermore, we observed that the mycelia of T. atroviride became ruptured and rough, and conidia were not generated in the zone of interaction between the hyphae of L. edodes (Y3334) and T. atroviride. By contrast, the mycelium of T. atroviride was smooth and straight, and many conidia that adhered to the surface of the susceptible L. edodes strain Y55 were generated (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Photographs and SEM observations of the responses of highly resistant and susceptible L. edodes to T. atroviride inoculation. (A) The confrontations of the L. edodes Y3334 and Y55 strains with T. atroviride strain 92-1. The red arrows represent LT (the length of the mycelia of T. atroviride covering L. edodes), as described by Wang et al. (2018) [32]. (B) SEM observations of the interactions of the L. edodes Y3334 and Y55 strains with T. atroviride strain 92-1 at 24 and 48 hpi, respectively. Bars = 10.0 μm.

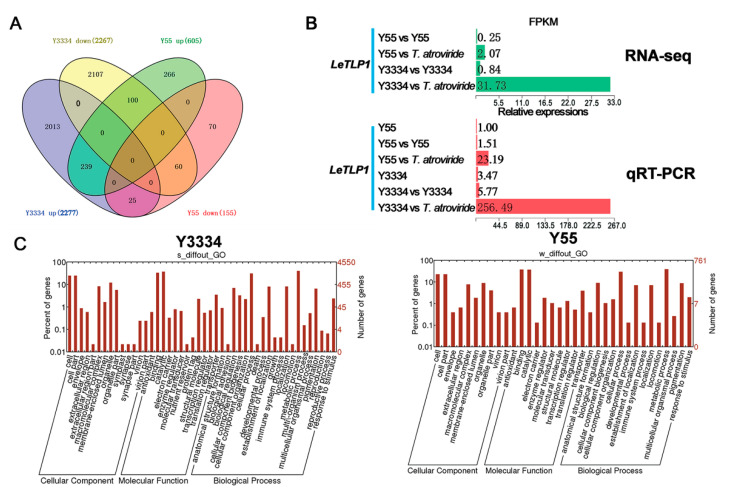

3.3. Transcriptional Responses of the Highly Resistant and Susceptible L. edodes strains to T. atroviride

In order to screen the candidate genes for conferring resistance to T. atroviride in L. edodes, we synthesized twelve cDNA libraries from the mycelia of L. edodes, which were collected from the peripheral hyphal zones of Y3334 vs. T. atroviride (s2), Y55 vs. T. atroviride (w2), Y3334 vs. Y3334 (s1), and Y55 vs. Y55 (w1) (Figure 1). This was the first time that transcriptome RNA-sequencing data were generated for the Y3334 and Y55 strains of L. edodes.

The DEGs were obtained by comparing the gene expressions among the s2, w2, s1, and w1 groups. As shown in the Venn diagram, a total of 4880 DEGs were obtained. In both the Y3334 and Y55 strains, 239 up-regulated genes were identified (Figure 3A). Among them, ten genes (Table S2) were selected to validate our differentially expressed gene results using qRT-PCR. The qRT-PCR results were correlated with the RNA-seq data (R2 = 0.8575, Figure S1), which confirmed the high reliability of the RNA-seq data in this study. Interestingly, the expression level of the thaumatin-like protein gene LeTLP1 (LE01Gene05009) was strikingly increased in the resistant Y3334 when responding to infection with T. atroviride, and the LeTLP1 expression level was extremely significantly higher than that in the susceptible Y55 in response to T. atroviride infection (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Transcriptional responses of the highly resistant and susceptible L. edodes strains to T. atroviride. (A) Venn diagram of upregulated and downregulated genes in L. edodes. (B) Significantly up-regulated LeTLP1 in the Y3334 and Y55 strains. The mycelial samples (s1, s2, w1, and w2) of the peripheral hyphal zones were harvested from L. edodes at the AC (after contact for 24 h) stage. s1: Y3334 vs. Y3334; s2: Y3334 vs. T. atrovide strain 92-1; w1: Y55 vs. Y55; w2: Y55 vs. T. atrovide strain 92-1. (C) The GO terms of differentially expressed genes in the Y3334 and Y55 strains.

The Gene Ontology enrichment analysis demonstrated that the most dominant groups among the biological process components were metabolic processes and cellular processes in both the Y3334 and Y55 strains (Figure 3C). The growth and death GO terms were only found in the highly resistant strain Y3334, while they were not found in the susceptible strain Y55. The genes in the growth and death GO terms might be resistance-related candidate genes. Meanwhile, the catalytic and binding activities were the most abundant functional groups among the molecular functions, implying that enzyme encoding genes (such as LeTLP1) may play key roles in the regulation of the resistance of L. edodes to T. atroviride.

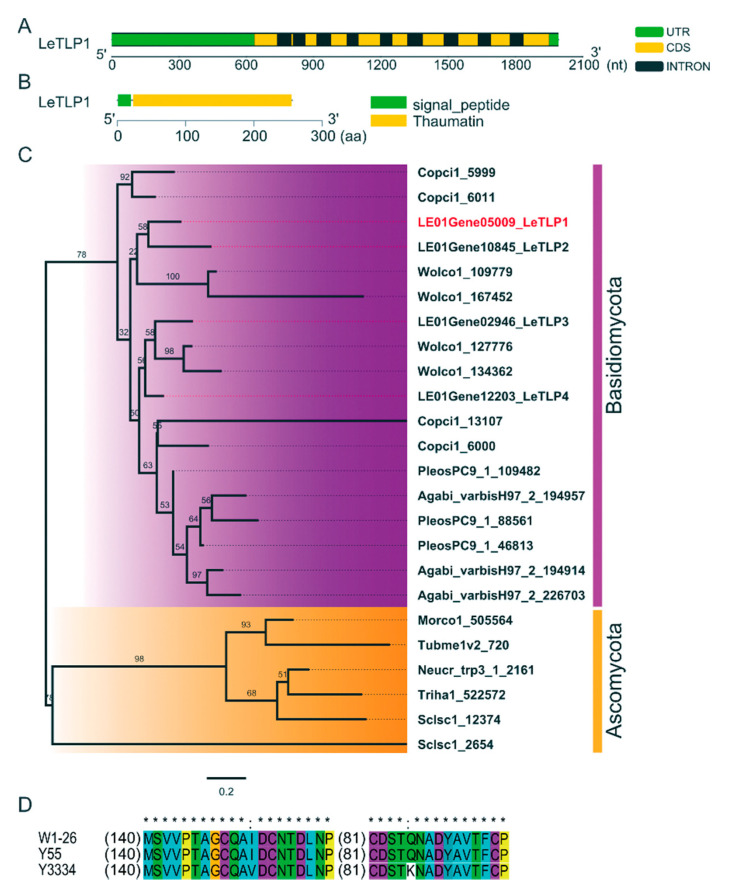

3.4. Molecular Characterization of LeTLP1

The full length of LeTLP1 was 1993 bp. The DNA and cDNA sequence analyses revealed that the 768-bp ORF of LeTLP1 was interrupted by nine introns (Figure 4A). The LeTLP1 gene was predicted to encode a protein of 255 amino acids that contained a signal peptide and a conserved thaumatin domain (Accession pfam00314, E-Value 1.14894e-96), which belonged to the GH64-TLP-SF superfamily (Figure 4B). The phylogenetic analysis of the TLP indicated that LeTLP1 was clustered with the LeTLP2, while it was separate from LeTLP3, LeTLP4, and the TLP genes of other fungi (Figure 4C). The amino acid sequences of LeTLP1 from W1-26 and Y55 were exactly the same, while the amino acid sequence of LeTLP1 from the resistant strain Y3334 exhibited two mutation sites (I-152-V and Q-245-K) compared to that of the sensitive strain Y55 (Figure 4D).

Figure 4.

Molecular characterization of LeTLP1. (A) Structure of LeTLP1. (B) The prediction of the conserved domain in LeTLP1. (C) Molecular phylogenetic tree of TLP generated with the neighbor-joining (NJ) method using MEGA 7.0. One thousand bootstrap replicates were calculated, and the bootstrap values are shown at each node. Accession numbers for the sequences are listed on the clades of the phylogenetic tree. They are recorded in JGI (https://genome.jgi.doe.gov/portal/ accessed on 5 January 2020) as follows: LE01Gene (L. edodes W1-26 v1.0), Agabi_varbisH97_2 (Agaricus bisporus var bisporus(H97) v2.0), Copci1 (Coprinopsis cinerea), PleosPC9_1 (Pleurotus ostreatus PC9 v1.0), Wolco1 (Wolfiporia cocos MD-104 SS10 v1.0), Morco1 (Morchella importuna CCBAS932 v1.0), Neucr_trp3_1 (Neurospora crassa FGSC73 trp-3 v1.0), Sclsc1 (Sclerotinia sclerotiorum v1.0), Triha1 (Trichoderma harzianum CBS 226.95 v1.0), and Tubme1v2 (Tuber melanosporum Mel28 v1.2). (D) Multiple alignments of the amino acid sequences of LeTLP1 from W1-26, Y55, and Y3334. * represents the same amino acid residues at the site; represents the different amino acid residues at the site. () indicates that the amino acid sequences are the same in the region.

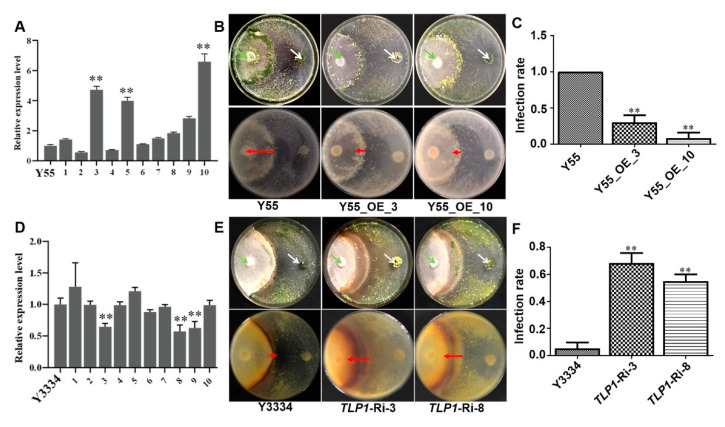

3.5. Effects of LeTLP1 Overexpression on the Resistance of L. edodes against T. atroviride

Compared with the parent isolate Y55, the gene expression levels of LeTLP1 in the three LeTLP1-overexpression transformants Y55_OE_3, Y55_OE_5, and Y55_OE_10 increased (p < 0.01) 4.5-fold, 4.0-fold, and 6.5-fold, respectively (Figure 5A). For two LeTLP1-overexpression strains (Y55_OE_3 and Y55_OE_10), significant differences in the responses of the LeTLP1-overexpression transformants and the susceptible (Y55) L. edodes strain to the infection with T. atroviride were observed (Figure 5B). The susceptible (Y55) L. edodes strain was completely covered by the mycelia and spores of T. atroviride, while only a few T. atroviride spores were observed on the surface of the mycelia of the LeTLP1-overexpression transformants. Notably, the infection rates (LT:LL) of T. atroviride in the mycelia of LeTLP1-overexpression transformants were significantly decreased compared to those in the parent isolate Y55 (Figure 5C). The results demonstrated that the overexpression of LeTLP1 played a crucial role in the resistance of L. edodes to T. atroviride.

Figure 5.

The effects of LeTLP1 overexpression on the resistance of L. edodes to T. atroviride infection. (A) Relative expression levels of LeTLP1 in the parent isolate Y55 of L. edodes and its LeTLP1-overexpression transformants; 1–10: Y55_OE_1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10. (B) The confrontations of the LeTLP1 overexpression transformants (Y55_OE_3 and Y55_OE_10) and the susceptible Y55 L. edodes against T. atroviride (92-1) were observed on the 15th day after inoculation with T. atroviride. (C) Infection rates (LT:LL) of T. atroviride in the susceptible Y55 strain and the LeTLP1-overexpression transformants. (D) Relative expression levels of LeTLP1 in the parent isolate Y3334 of L. edodes and its LeTLP1-silenced transformants; 1–10: TLP1-Ri-1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10. (E) The confrontations of the LeTLP1-silenced transformants (TLP1-Ri-3, TLP1-Ri-8, and TLP1-Ri-9) and the susceptible L. edodes (Y55) against T. atroviride (92-1) were observed on the 15th day after inoculation with T. atroviride, respectively. (F) Infection rates (LT:LL) of T. atroviride in the resistant strain Y3334 and LeTLP1 RNAi transformants. Bars denote the standard error of the mean of three replicates in each of three independent experiments. ** indicates a statistically significant difference (p < 0.01). Green arrows refer to mycelial plugs of L. edodes; white arrows refer to mycelial plugs of T. atroviride. Red arrows represent LT (the length of T. atroviride mycelia covering L. edodes), as described by Wang et al. (2018) [32].

Compared with the parent isolate Y3334, the transcription levels of LeTLP1 in the three silenced transformants TLP1-Ri-3, TLP1-Ri-8, and TLP1-Ri-9 declined by 35%, 43%, and 38%, respectively (Figure 5D). For two LeTLP1 RNAi strains (TLP1-Ri-3 and TLP1-Ri-8), deep black compounds were generated in the interaction zone between the mycelia of the LeTLP1 RNAi strains and the T. atroviride strains (Figure 5E), and the infection rates (LT:LL) of T. atroviride in the mycelia of L. edodes increased dramatically compared to those in the parent isolate Y3334 (Figure 5F). The results indicated that the resistance levels significantly declined when LeTLP1 was silenced in L. edodes.

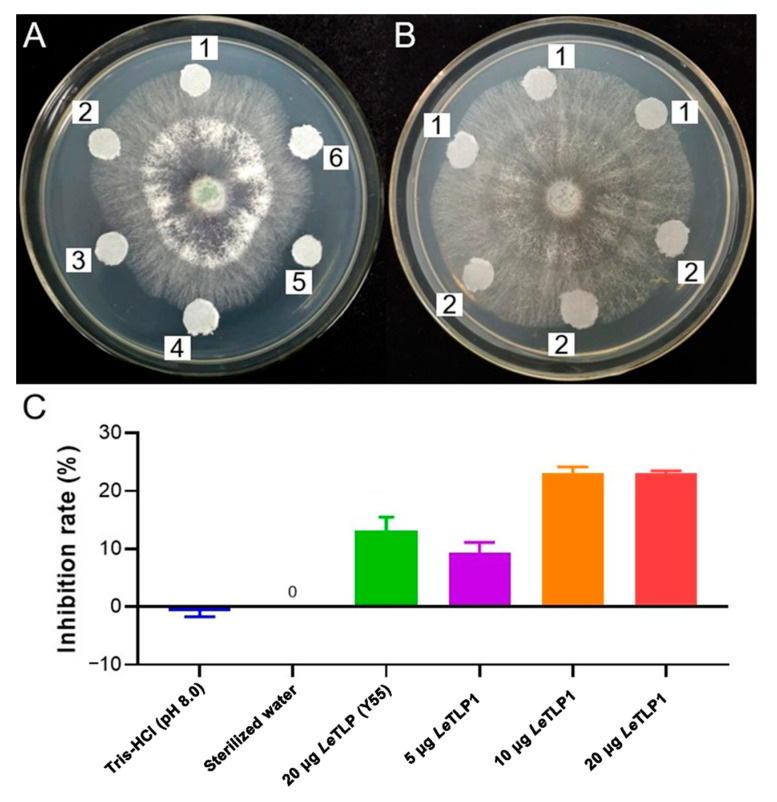

3.6. Antifungal Activity of LeTLP1 against T. atroviride

The filter paper discs that contained the purified LeTLP1 obviously inhibited the mycelial growth of T. atroviride (Figure 6A,B). On the other hand, LeTLP1 was found to be more effective than LeTLP (Y55) against the mycelial growth of T. atroviride (Figure 6C). The results demonstrated that LeTLP1 exhibited significant antifungal activity against T. atroviride.

Figure 6.

Antifungal activity of LeTLP1 against T. atroviride. (A,B) The antifungal activity of LeTLP1 was measured by using the paper disc method described by Imtiaj and Lee (2007) [38]. Agar discs taken from 10 day old cultures of T. atroviride strain 92-1 and were placed in the center of the Petri plates. 1–6: The paper discs of Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), sterilized water, 20 μg of LeTLP (Y55), 5 μg of LeTLP1, 10 μg of LeTLP1, and 20 μg of LeTLP1. (C) The inhibition rates (the percent inhibition of mycelial growth—PIMG) were calculated as described in Imtiaj and Lee (2007) [38].

4. Discussion

The nutritional compounds and pharmacological properties of Lentinula edodes are beneficial to human health [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8]. Unfortunately, L. edodes is heavily attacked by Trichoderma spp., which compete for limited resources and space for mycelial growth, and it harms the yield and quality of shiitake cultivation [12,16,17,39,40]. In order to protect L. edodes from the infection with T. atroviride, the screenings of resistant L. edodes germplasms and breeding of resistant L. edodes strains are eco-friendly and safe alternatives to the use of chemical fungicides [12,16,18]. Deciphering the molecular mechanisms of the resistance of L. edodes to T. atroviride will provide a theoretical basis for the breeding of resistant L. edodes strains.

In this study, significant differences in the responses of the highly resistant (Y3334) and susceptible (Y55) L. edodes strains to infection with T. atroviride were observed (Figure 2). A previous study demonstrated that T. atroviride possesses a strong capacity for attacking the mycelia of the susceptible L. edodes strain [12]. The SEM observations (Figure 2B) showed that the susceptible Y55 strain was heavily infected by T. atroviride, while the highly resistant Y3334 strain grew healthily. Therefore, the highly resistant Y3334 strain and the susceptible Y55 strain were proper materials for studying the molecular basis of the resistance of L. edodes to T. atroviride.

By using a transcriptomic analysis, we identified a novel candidate resistance-related gene, LeTLP1 (LE01Gene05009), which contains a conserved thaumatin domain (Figure 3 and Figure 4B) and belongs to the group of thaumatin-like protein (TLPs). LeTLP1 was strikingly significantly induced when the resistant L. edodes strain Y3334 responded to T. atroviride infection in comparison with the response of susceptible L. edodes, and this was verified by using qRT-PCR detection (Figure 3B). Similarly, thaumatin-like proteins (TLPs) were shown to be induced in rice plants that were infected with Rhizoctonia solani [41]. LeTLP1 (Figure S2) shares 16 conserved cysteines (Cys) that are required for eight disulfide bonds, as well as other TLPs, which play important roles in maintaining the structure and activity [42,43]. However, the functions of the novel LeTLP1 in L. edodes and whether it regulates the resistance to T. atroviride are yet unknown.

In plants, TLPs are known as PR-5 proteins, and some of TLPs are known to exhibit both β-1,3-glucan binding [27,44,45] and endo-β-1,3-glucanase activities [46]. β-glucan, the most abundant fungal cell wall polysaccharide in fungi, serves in microbe-associated molecular patterns (MAMPs) [47]. In fungal cell walls, the most abundant β-glucan is β-1,3-glucan, which consists of dominant β-glucan content [48]. The TLPs crack the β-1,3-glucan in the cell walls of fungi and exhibit antifungal activity [27,46]. Furthermore, recent studies found that the TLPs also occurred in L. edodes [42,46], and they were highly conserved in plants exhibiting endo-β-1,3-glucanase activity. A previous study indicated that TLPs exhibit antifungal activity by lysing the β-1, 3-glucan in the cell walls of pathogenic fungi. TLPs may participate in regulating the level of resistance of L. edodes relative to invading fungi. In addition, the overexpression of the rice TLP gene in transgenic cassava resulted in enhanced tolerance to Colletotrichum gloeosporioides [49]. Thaumatin-like protein (Pe-TLP) acted as a positive factor in the enhanced resistance to spot disease in transgenic poplars [50]. Therefore, we asked whether the novel LeTLP1 regulates the resistance level in L. edodes. Interestingly, the LeTLP1-overexpression experiment (Figure 5) demonstrated that the overexpression of LeTLP1 contributes to the enhancement of the level of resistance of L. edodes against T. atroviride. The resistance levels of LeTLP1-silenced transformants (TLP1-Ri-3 and TLP1-Ri-8) declined. Our results demonstrated that the overexpression of LeTLP1 plays a crucial role in the resistance of L. edodes to T. atroviride.

It is noteworthy that a thaumatin-like protein (TLG1) from L. edodes degrades lentinan (a β-1,3-glucan found in its own cell wall) and, thus, may play a role in cell wall degradation [42]. How does L. edodes protect itself against the activity of LeTLP1? Our results showed that the expression level of LeTLP1 was very low without T. atroviride infection (Figure 3B). Therefore, the production of LeTLP1 is likely to be very limited in mycelia grown in a sawdust culture. This indicates that there is not enough to inflict any harm on itself. However, the LeTLP1 gene expression level was strongly increased in the resistant L. edodes in response to the infection with T. atroviride (Figure 3B). LeTLP1 might affect the mycelia of L. edodes in response to the infection with T. atroviride. However, the SEM observations (Figure 2B) confirmed that the highly resistant L. edodes Y3334 strain grew healthily in a dual culture with T. atroviride. Consistently, L. edodes tlg1 was not transcribed in vegetative mycelia grown in a liquid culture or sawdust culture, suggesting that it was induced under stress conditions [42]. Notably, a previous study indicated that the thaumatin-like protein (TLG1) might not act as an antifungal agent [42]. However, our results demonstrated that the LeTLP1 protein exhibited significant antifungal activity against T. atroviride (Figure 6). Taking the results together, this study demonstrates that the overexpression of LeTLP1 in L. edodes results in resistance to T. atroviride.

5. Conclusions

We obtained a highly resistant L. edodes strain (Y3334) and a susceptible strain (Y55) and found a novel resistance-related gene, LeTLP1 (LE01Gene05009), in the resistant L. edodes strain (Y3334). Further analysis showed that the LeTLP1 gene expression level strongly increased in the resistant L. edodes in response to the infection with T. atroviride compared with the susceptible L. edodes strain. However, the expression level of LeTLP1 was very low without the T. atroviride infection. More importantly, the experiment with LeTLP1 overexpression and silencing clarified that the expression of LeTLP1 was highly correlated with the level of resistance of L. edodes against T. atroviride. In addition, the LeTLP1 protein (Y3334) exhibited significant antifungal activity against T. atroviride. LeTLP1 was found to be more effective than LeTLP (Y55) against the mycelial growth of T. atroviride. This study demonstrates that resistance to T. atroviride is endowed by the enhanced expression of LeTLP1 in L. edodes, thus providing insights into the molecular mechanisms of the resistance of L. edodes against T. atroviride. Further characterization of the upstream activators and downstream targets of LeTLP1 will be used to decipher the resistance mechanisms in L. edodes and other basidiomycetes.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Jianbo Cao for the scanning electron microscopy observations.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/life11080863/s1, Figure S1: qRT-PCR results of ten selected genes and the correlations between transcripotome data and real-time PCR results, Figure S2: Alignment of the amino acid sequences of LeTLP1 (Y3334), LeTLP (Y55), and L. edodes TLP (GenBank: AB244759), Table S1: Cultivated and wild strains of Lentinula edodes used in this study, Table S2: Primers used for real-time quantitative PCR.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.M., Y.X. and Y.B.; methodology, X.M., X.F., R.X. and Y.Z.; investigation, X.M., X.F., G.W. and L.Y.; validation, Y.Z.; resources, Y.Z.; formal analysis, Y.G.; writing—original draft preparation, X.M. and Y.X.; writing—reviewing and editing, Y.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant No. 2019YFD1001905-35), the Major Project for Technological Innovation Plans of Hubei Province (Grant No. 2018ABA095), and the Earmarked Fund for China Agriculture Research System of Edible Fungi (Grant No. CARS-20).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable. This study did not involve humans.

Data Availability Statement

The RNA-seq data generated for this study have been deposited into the Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under accession number: PRJNA590542.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Kwan H.S., Au C.H., Wong M.C., Qin J., Kwok I.S.W., Nong W.Y., Chum W.W.Y. Genome sequence and genetic linkage analysis of Shiitake mushroom Lentinula edodes. Nat. Preced. 2012;1:1. doi: 10.1038/npre.2012.6855.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Quaicoe E.H., Amoah C., Obodai M., Odamtten G.T. Nutrient requirements and environmental conditions for the cultivation of the medicinal mushroom (Lentinula edodes) (Berk.) in Ghana. Int. J. Sci. Technol. Res. 2014;3:45–50. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Finimundy T., Dillon A., Henriques J., Ely M. A review on general nutritional compounds and pharmacological properties of the Lentinula edodes mushroom. Int. J. Food. Sci. Nutr. 2014;5:1095–1105. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li C., Gong W.B., Zhang L., Yang Z.Q., Nong W.Y., Bian Y.B., Hoi-Shan K., Man-Kit C., Xiao Y. Association mapping reveals genetic loci Associated with Important Agronomic Traits in Lentinula edodes, Shiitake Mushroom. Front. Microbiol. 2017;8:237. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Diego M., Eva T.C., Noelia J.C., Gonzalo P., María T., Alejandro R.R., Carlota L., Cristina S.R. In vitro and in vivo testing of the hypocholesterolemic activity of ergosterol- and β-glucan-enriched extracts obtained from shiitake mushrooms (Lentinula edodes) Food Funct. 2019;10:7325–7332. doi: 10.1039/c9fo01744e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Diego M., María T., Carlota L., Gonzalo P., Adriana J.P., Cristina S.R. Effect of traditional and modern culinary processing, bioaccessibility, biosafety and bioavailability of eritadenine, a hypocholesterolemic compound from edible mushrooms. Food Funct. 2018;9:6360–6368. doi: 10.1039/c8fo01704b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Diego M., Renata R., Marisol A.V., Hellen A., Cristina S.R., Susana S., Marcello I., Fhernanda S. Isolation and comparison of α- and β-D-glucans from shiitake mushrooms (Lentinula edodes) with different biological activities. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019;229:115521. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2019.115521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pan W., Jiang P., Zhao J., Shi H., Yu Y. β-glucan from Lentinula edodes prevents cognitive impairments in high-fat diet-induced obese mice: Involvement of colon-brain axis. J. Transl. Med. 2021;19:54. doi: 10.1186/s12967-021-02724-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ohmasa M., Cheong M.L. Effects of culture conditions of Lentinula edodes, Shiitake mushroom, on the disease resistance of Lentinula edodes against Trichoderma harzianum in the sawdust cultures; Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Mushroom Biology and Mushroom Products; Sydney, Australia. 11–15 October 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Julian A.V., Reyes R.G., Eguchi F. Reference Module in Earth Systems and Environmental Sciences. 2nd ed. Elsevier; Amsterdam, The Netherlands: 2018. pp. 13–20. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ohga S., Royse D.J. Transcriptional regulation of laccase and cellulase genes during growth and fruiting of Lentinula edodes on supplemented sawdust. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2001;201:111–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2001.tb10741.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang G., Cao X., Ma X., Guo M., Liu C., Yan L., Bian Y. Diversity and effect of Trichoderma spp. associated with green mold disease on Lentinula edodes in China. MicrobiologyOpen. 2016;5:709–718. doi: 10.1002/mbo3.364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Luković J., Milijašević-Marčić S., Hatvani L., Kredics L., Szűcs A., Vágvölgyi C., Nataša D., Ivana V., Potočnik I. Sensitivity of Trichoderma strains from edible mushrooms to the fungicides prochloraz and metrafenone. J. Environ. Sci. Health B. 2020;56:54–63. doi: 10.1080/03601234.2020.1838821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jiang H.F., Wang F.L., Tan Q. A preliminary study on Trichoderma spp. and dominant T. species in Lentinula edodes growing. Shanghai ACTA Agric. 1995;11:85–90. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu X.P., Wu X.J., Hu F.P., He H.Z., Xie B.G. Identification of Trichoderma species associated with cultivated edible fungi. J. Agric. Biotechnol. 2008;16:1048–1055. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tokimoto K. Physiological studies on antagonism between Lentinula edodes and Trichoderma spp. in bedlogs of the former. Rep. Tottori. Mycol. Inst. 1985;23:1–54. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seaby D. Trichoderma as a weed mould or pathogen in mushroom cultivation. Trichoderma Gliocladium. 1998;2:267–272. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee H.M., Bak W.C., Lee B.H., Park H., Ka K.H. Breeding and Screening of Lentinula edodes species resistance to Trichoderma spp. Mycobiology. 2008;4:270–272. doi: 10.4489/MYCO.2008.36.4.270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Park M.S., Bae K.S., Yu S.H. Two new species of Trichoderma associated with green mold of oyster mushroom cultivation in Korea. Mycobiology. 2006;34:111–113. doi: 10.4489/MYCO.2006.34.3.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cao X.T., Bian Y.B., Xu Z.Y. First Report of Trichoderma oblongisporum Causing Green Mold Disease on Lentinula edodes (shiitake) in China. Plant Dis. 2014;98:1440. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-05-14-0537-PDN. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jhune C.S., You C.H., Cha D.Y. Effects of thiabendazole on green mold, Trichoderma spp. during cultivation of oyster mushroom, Pleurotus spp. Korean J. Mycol. 1990;18:89–96. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rezaei D.Y., Mohammadi G.E. Studies of the effects of benomyl and carbendazim on Trichoderma green mould control in button mushroom farms. J. Agric. Sci. 2007;16:157–165. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abdi S., Sobhan A.S., Sobhan A.S. Monitoring of Benomyl Residue in Mushroom Marketed in Hamadan City. Sci. J. Hamadan Univ. Med. Sci. 2015;22:137–143. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shuping D.S.S., Eloff J.N. The use of plants to protect plants and food against fungal pathogens: A review. Afr. J. Tradit. Complement. Altern. Med. 2017;14:120–127. doi: 10.21010/ajtcam.v14i4.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guo M.P., Ye Z.M., Shen G.Y., Bian Y.B., Xu Z.Y. Effects of mycovirus LeV-HKB on resistance of heat stress challenged Lentinula edodes mycelia against Trichoderma atroviride. Acta Edulis Fungi. 2020;27:143. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mata G., Savoie J.M. Screening of Lentinula Edodes strains by laccase induction and resistence to Trichoderma spp. Rev. Mex. Micol. 1998;14:29–32. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Savoie J.M., Mata G. The antagonistic action of Trichoderma spp. hyphae to Lentinula edodes hyphae changes ignocellulotytic activities during cultivation in wheat straw. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1999;15:369–373. doi: 10.1023/A:1008979701853. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ragucci S., Landi N., Russo R., Valletta M., Pedone P.V., Chambery A., Maro A.D. Ageritin from pioppino mushroom: The prototype of ribotoxin-like proteins, a novel family of specific ribonucleases in edible mushrooms. Toxins. 2021;13:263. doi: 10.3390/toxins13040263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu J., Wang Z.R., Li C., Bian Y.B., Xiao Y. Evaluating genetic diversity and constructing core collections of Chinese Lentinula edodes cultivars using ISSR and SRAP markers. J. Basic Microbiol. 2015;55:749–760. doi: 10.1002/jobm.201400774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jiang Q. Master’s Thesis. Huazhong Agricultural University; Wuhan, China: 2017. Preliminary Research on Resistance Differentiation of Lentinula edodes Resources to Trichoderma spp. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu J., Ma C.J., Xiang X.J., Li C., Bian Y.B., Zhang J., Xiao Y. Constructing Core Collections of Chinese Wild Lentinula edodes Strains Based on SRAP Markers. Acta Edulis Fungi. 2017;24:7–17. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang G.Z., Zhou S.S., Luo Y., Ma C.J., Gong Y.H., Zhou Y., Gao S.S., Huang Z.C., Yan L.L., Hu Y., et al. The heat shock protein 40 LeDnaJ regulates stress resistance and indole-3-acetic acid biosynthesis in Lentinula edodes. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2018;118:37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2018.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Trapnell C., Roberts A., Goff L., Pertea G., Kim D., Kelley D.R., Pimentel H., Salzberg S.L., Rinn J.L., Pachter L. Differential gene and transcript expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments with TopHat and Cufflinks. Nat. Protoc. 2012;7:562–578. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li H., Handsaker B., Wysoker A., Fennell T., Ruan J. The Sequence Alignment-Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2078–2079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lalitha S. Primer premier 5. Biotech Softw. Internet Rep. 2000;1:270–272. doi: 10.1089/152791600459894. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Livak K.J., Schmittgen T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yan L.L., Xu R.P., Dai S.H., Wang G.Z., Bian Y.B., Gong Y.H., Zhou Y. Overexpression of a laccase gene Lelcc1 and phenotypic characterizations in Lentinula edodes. Mycosystema. 2019;38:831–840. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Imtiaj A., Lee T.S. Screening of antibacterial and antifungal activities from Korean wild mushrooms. World J. Agrc. Sci. 2007;3:316–321. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ulhoa C.J., Peberdy J.F. Purification and some properties of the extracellular chitinase produced by Trichoderma harzianum. Enzym. Microb. Technol. 1992;14:236–240. doi: 10.1016/0141-0229(92)90072-V. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kobayashi T., Oguro M., Akiba M., Taki H., Kitajima H., Ishihara H. Mushroom yield of cultivated shiitake (Lentinula edodes) and fungal communities in logs. J. For. Res. 2020;25:269–275. doi: 10.1080/13416979.2020.1759886. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Velazhahan R., Chen-Cole K., Anuratha C.S., Muthukrishnan S. Induction of thaumatin-like proteins (TLPs) in Rhizoctonia solani-infected rice and characterization of two new cDNA clones. Physiol. Plant. 1998;102:21–28. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3054.1998.1020104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sakamoto Y., Watanabe H., Nagai M., Nakade K., Takahashi M., Sato T. Lentinula edodes tlg1 encodes a thaumatin-like protein that is involved in lentinan degradation and fruiting body senescence. Plant Physiol. 2006;141:793–801. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.076679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Koiwa H., Kato H., Nakatsu T., Oda J., Yamada Y., Sato F. Crystal structure of tobacco PR-5d protein at 1.8 Å resolution reveals a conserved acidic cleft structure in antifungal thaumatin-like proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 1999;286:1137–1145. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Trudel J., Grenier J., Potvin C., Asselin A. Several thaumatin like proteins bind to β-1,3-glucans. Plant Physiol. 1998;118:1431–1438. doi: 10.1104/pp.118.4.1431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kumar R., Mukherjee P.K. Trichoderma virens Alt a 1 protein may target maize PR5/thaumatin-like protein to suppress plant defence: An in silico analysis. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2020;112:101551. doi: 10.1016/j.pmpp.2020.101551. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Grenier J., Potvin C., Asselin A. Some fungi express β-1,3-glucanases similar to thaumatin-like proteins. Mycologia. 2000;92:841–848. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Philipp H.F., Alga Z. β-glucan: Crucial component of the fungal cell wall and elusive MAMP in plants. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2016;90:53–60. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2015.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brown S.M., Free S.J. The structure and synthesis of the fungal cell wall. BioEssays. 2006;28:799–808. doi: 10.1002/bies.20441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ojola P.O., Nyaboga E.N., Njiru P.N., Orinda G.O. Overexpression of rice thaumatin-like protein (Ostlp) gene in transgenic cassava results in enhanced tolerance to Colletotrichum gloeosporioides f. sp. manihotis. J. Genet. Eng. Biotechnol. 2018;16:125–131. doi: 10.1016/j.jgeb.2017.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sun W., Zhou Y., Movahedi A., Wei H., Zhuge Q. Thaumatin-like protein (Pe-TLP) acts as a positive factor in transgenic poplars enhanced resistance to spots disease. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2020;112:101512. doi: 10.1016/j.pmpp.2020.101512. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The RNA-seq data generated for this study have been deposited into the Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under accession number: PRJNA590542.