Abstract

Locus control regions (LCRs) are cis-acting regulatory elements thought to provide a tissue-specific open chromatin domain for genes to which they are linked. The gene for T-cell receptor α chain (TCRα) is exclusively expressed in T cells, and the chromatin at its locus displays differentially open configurations in expressing and nonexpressing tissues. Mouse TCRα exists in a complex locus containing three differentially regulated genes. We previously described an LCR in this locus that confers T-lineage-specific expression upon linked transgenes. The 3′ portion of this LCR contains an unrestricted chromatin opening activity while the 5′ portion contains elements restricting this activity to T cells. This tissue-specificity region contains four known DNase I hypersensitive sites, two located near transcriptional silencers, one at the TCRα enhancer, and another located 3′ of the enhancer in a 1-kb region of unknown function. Analysis of this region using transgenic mice reveals that the silencer regions contribute negligibly to LCR activity. While the enhancer is required for complete LCR function, its removal has surprisingly little effect on chromatin structure or expression outside the thymus. Rather, the region 3′ of the enhancer appears responsible for the tissue-differential chromatin configurations observed at the TCRα locus. This region, herein termed the “HS1′ element,” also increases lymphoid transgene expression while suppressing ectopic transgene activity. Thus, this previously undescribed element is an integral part of the TCRαLCR, which influences tissue-specific chromatin structure and gene expression.

The locus control region (LCR), first described in the β-globin gene cluster (18, 23), is defined by its ability to impart position-independent and high-level tissue-specific expression of a linked transgene in chromatin (recently reviewed in references 19 and 32). An LCR protects a transgene from “position effect variegation,” which could silence its transcription if it integrates into inactive chromatin (46). LCRs are thought to provide an open chromatin environment, which is necessary for physiological expression of a linked transgene at any integration site (17, 42). LCRs are frequently associated with loci that maintain tissue-restricted expression. Accordingly, it has been observed that the activity of an LCR is restricted to the tissues in which its locus of origin is normally expressed (2, 3, 5, 23, 31, 35, 38), even when it is linked to heterologous transgenes (22, 45, 53). What provides tissue specificity to LCR activity is not completely clear. Mutational analyses of LCRs have led to the conclusion that the chromatin opening activity of an LCR is inherently tissue specific in nature (11, 47, 53).

The T-cell receptor α (TCRα) gene is exclusively expressed in T-lineage cells. Prerearranged TCRα transgenes under endogenous controls are expressed only in T-cell-bearing tissues, such as thymus and spleen, but not in other organs, such as liver and heart (9). Mouse TCRα exists in a complex locus on mouse chromosome 14 that also includes the genes for the TCRδ chain and Dad1 (1, 26). TCRα and TCRδ genes are mutually exclusively expressed by the αβ and γδ subpopulations of T cells, respectively. In contrast, the Dad1 gene, which is 3′ of TCRα, is expressed ubiquitously. We have described an LCR in this locus that, in T-cell lines, manifests itself as eight DNase I hypersensitive sites (HS) extending from the TCRα chain constant region exons to 5′ of the Dad1 gene. HS1 maps to the well-characterized TCRα enhancer (25, 36, 58). HS2 to HS6 lie 3′ of HS1 in the locus. HS7 and -8 are 5′ of HS1. Fragments containing HS7 and -8 also contain transcriptional silencers defined in transient transfection assays (59). Additionally, a ninth HS, named HS1′, has been discovered in a 1-kb region of unknown function between HS1 and HS2 (26, 45). The chromatin at the endogenous LCR exists in differential configurations in TCRα-expressing and nonexpressing tissues (26, 45). In normal thymocytes, HS1 and HS6 are the strongest HS in the LCR region. These HS are either weak or are not present in non-T-cell-bearing organs. HS2 to -5 and HS7 and -8, are weak in all organs, while HS1′ is predominantly present in nonlymphoid tissues.

The 9-kb region containing all nine HS of the LCR has been shown to direct high-level, position-independent, copy number-dependent, and T-cell compartment-specific expression of a linked TCRα transgene and a heterologous human β-globin transcription unit (9, 45). Our initial characterization of the LCR (45) revealed that it contained an unrestricted chromatin opening activity located in the 3′ HS2 to HS6 region. This fragment drives widespread transgene expression and adopts an abnormal, wide-open chromatin configuration in which all of HS2 to -6 are equally prominent in both lymphoid and nonlymphoid organs. The 5′ LCR region containing HS7, -8, -1, and 1′ confers cell-type specificity to the chromatin opening activity. This is marked by a restoration of T-cell-specific expression and the naturally occurring tissue-differential chromatin structures observed at the TCRα locus. The unique arrangement of a 3′ unrestricted chromatin opening activity and a 5′ T-cell-specificity region in the TCRαLCR is noteworthy. It suggested that, endogenously, the Dad1 gene, residing 3′ of the LCR, and the TCRα gene, localized 5′ of the LCR, may be sharing some of the LCR elements (26). How the regulation of T-cell-specific and ubiquitously expressed genes is coordinated within the same locus is a question of considerable interest.

Our previous work showed for the first time that the chromatin-opening and tissue-specific functions of LCRs can, at least in some cases, be separated (45). The presence of a T-cell-specific enhancer and silencers in the 5′ tissue-specificity region would suggest a role for these elements in the restriction of LCR activity. While the 1-kb region containing HS1′ is highly conserved between mouse and human loci (33), to date, no activity has been ascribed to it. To determine the contributions of activities in HS7 and -8, HS1, and HS1′ to tissue-specific LCR function, we report here further deletion analysis of the mouse TCRαLCR. We find that the silencer region containing HS7 and -8 has a very minor inhibitory effect on transgene expression in T-cell-bearing organs and appears dispensable for complete LCR activity. The T-cell-specific enhancer (HS1) increases transcription in thymus and has no other apparent effect on expression in other organs. In addition, HS1 contributes to copy-number-dependent expression of the reporter and is thus an integral part of the LCR. Surprisingly, removal of these silencer- and enhancer-containing regions has no severe effect on the chromatin structure of the remaining LCR sequences. Rather, the HS1′ region appears to be responsible for maintaining the cell-type-specific chromatin structures observed at the 3′ chromatin opening region. Although no transcriptional activity has ever been described in the HS1′ region, we find that this region increases transcription in thymus and spleen and suppresses ectopic expression of our reporter transgene. Thus, this previously undescribed control element plays an important role in tissue-specific functions of the TCRαLCR. The location of this novel activity, which we term the “HS1′ element,” between the T-cell-specific enhancer and the region containing unrestricted chromatin opening activity may also suggest a potential role for it in separating the regulation of the TCRα and Dad1 genes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Transgenic mice.

DNA fragments for microinjection were double purified by gel electrophoresis on low-melting-point agarose (Seaplaque-FMC) followed by digestion with β-agarase (New England Biolabs). DNA was microinjected into the pronucleus of (C57BL/6 × CBA)F2 fertilized mouse eggs, and transferred into pseudopregnant CD1 foster mothers. Transgenic founders were identified by Southern blot analysis on tail DNA. The founders were outcrossed to C57BL/6 mice, and offspring from these crosses were analyzed. Transgenic offspring were identified by Southern blotting and/or PCR of ear-punch DNA. Relative copy number was determined for each line by analysis of at least two Southern blots by PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics). All lines directly compared in this work were analyzed for relative copy number on the same Southern blot by using the same probe (to the HS6 region) and enzyme digestion, with endogenous TCRα locus signal used as a normalizing control.

DNA constructs.

The construction of the 9-kb HS1 to -8 fragment, 5.9-kb HS2 to -6 fragment, and the β:1-8 and β:2-6 transgenes has been previously described (45). For the β:1-6 construct, a 7.4-kb XhoI-SacI fragment of the HS1 to -8 region was excised from the pSP72:HS1-8 vector by using XhoI and ClaI. This fragment was cloned into the previously described pSP72 vector (Promega) containing the 4.9-kb BglII human β-globin fragment (22, 45) in a position 3′ of the transcription unit. β:1′-6 was similarly constructed by using a 6.8-kb PmlI-SacI fragment of the LCR. Transgenic inserts for microinjection were liberated from vector DNA by using SalI and ClaI.

RNA analysis.

RNA was prepared according to the one-step protocol (7) from transgenic mouse tissues that were dissected of fat, minced (except for thymus and spleen), and rinsed extensively with phosphate-buffered saline to minimize contaminating blood. Five micrograms of RNA samples was used in each of the RNase protection assays (21). RNA probes were labeled with [32P]GTP and SP6 RNA polymerase as follows. For β-globin, a 2.0-kb BamHI fragment spanning exons 1 and 2 was cloned into pSP72 in the opposite orientation with respect to the SP6 promoter. The plasmid was linearized with AvaII to generate an RNA probe to exon 2. For γ-actin, plasmid was made and linearized with HinfI (14). For the TCRα constant region probe, a fragment representing Cα exon 1 was cloned into pGEM-3 (Promega) antisense to the SP6 promoter and linearized with either NcoI to generate a 450-bp probe or with AvaII to generate a 135-bp probe by using SP6 RNA polymerase. The resulting RNA probes were purified by acrylamide gel electrophoresis prior to hybridization. Absolute numbers reported for mRNA expression levels are normalized to those of internal loading controls and quantified within the experiment presented. Because differences in RNA probe preparation and RNase digestion conditions are sometimes unavoidable between separate experiments, comparison of absolute expression levels between individual points in different experiments is not valid.

DNase hypersensitivity assays.

Nuclei from liver (60) and thymus (15) were prepared and resuspended in DNase digestion buffer (51) at 108 nuclei/ml. Nuclei were digested for 10 min on ice. Digestion was stopped with 1/10 volume 5% sodium dodecyl sulfate–100 mM EDTA. T cells of the γδ lineage were isolated from 30 TCRβ mutant mice (43). Lymph nodes were dissected, and B cells were depleted by panning with antimouse immunoglobulin (Caltag M30800) (39). The remaining cells were purified by fluorescence-activated cell sorting with fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated anti-γδ TCR monoclonal antibody (GL3; Pharmingen). Nuclei were isolated from γδ T cells in the same manner as thymocytes. For transgene analysis, genomic DNA was digested with SwaI and SacI to generate a fragment extending from the β-globin coding region on the 5′ end to HS6 on the 3′ end. A 32P-labeled SwaI-PstI fragment of the β-globin reporter was used as a probe. For the endogenous LCR, a 9-kb EcoRV fragment from 3′ of Cα exon 1 to the area near HS2 was analyzed by probing with a 32P-labeled EcoRV-NcoI fragment of the LCR. The digested, DNase I-treated DNA samples were subjected to electrophoresis through 0.8% agarose. Southern blots were prepared on Hybond-N+ membrane (Amersham). Hybridization was performed by using Quickhyb solution (Stratagene).

RESULTS

Deletion analysis of the TCRα LCR tissue distribution-determining region.

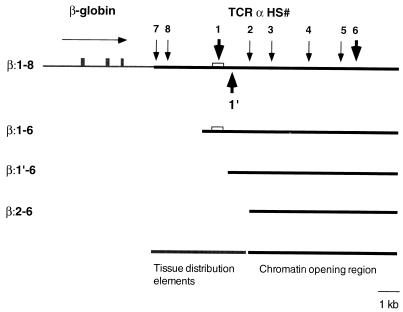

For our LCR analyses, we utilized a 4.9-kb BglII fragment of the human β-globin locus as a reporter gene. This fragment has been extensively used in the analysis of LCRs, because on its own, it is subject to severe position effects in transgenic mice (6, 22, 23, 54). It has been used in the analysis of the LCRs for the human β-globin (23), human CD2 (22), and mouse TCRα genes (45). In the latter two systems, the T-cell-specific activity of the heterologous LCR dominates the β-globin regulatory elements, resulting in T-cell compartment-specific expression of the reporter. In our previous analyses of mice transgenic for the β:1-8 and β:2-6 constructs (see reference 45 and Fig. 1), we showed that removal of the four 5′ proximal HS of the TCRαLCR abolishes its T-cell-specific expression pattern and chromatin structure. To define the contribution of each of these HS regions to tissue-specific LCR activity, two additional transgenic constructs were made in which the human β-globin reporter was linked to either HS1 to -6 or HS1′ to -6 of the LCR. Transgenic mice were generated with these new transgenes, called β:1-6 (a deletion of HS7 and -8 from β:1-8) and β:1′-6 (a further deletion of HS1 from β:1-6) (Fig. 1). Transgenic mouse lines derived from multiple independent founders were analyzed for each construct. Four lines for the β:1-6 transgene and 10 lines for the β:1′-6 construct were generated. All four of the former and eight of the latter lines are analyzed here. These lines were compared to three representative lines of previously generated β:1-8 and β:2-6 transgenic mice (45) to assess the activities present in the HS clusters.

FIG. 1.

Diagram of the transgenic constructs used in this study. Four transgenic constructs are depicted with DNase I hypersensitive sites of the TCRα locus (as observed in T-cell lines) labeled with vertical arrows. Large arrows above the line indicate the predominant HS found in normal thymocytes. A horizontal arrow indicates the transcriptional orientation of the β-globin reporter gene, which is present in all four constructs. Tissue distribution and chromatin opening regions were described in reference 45.

Transcriptional contributions of TCRα silencer and enhancer regions.

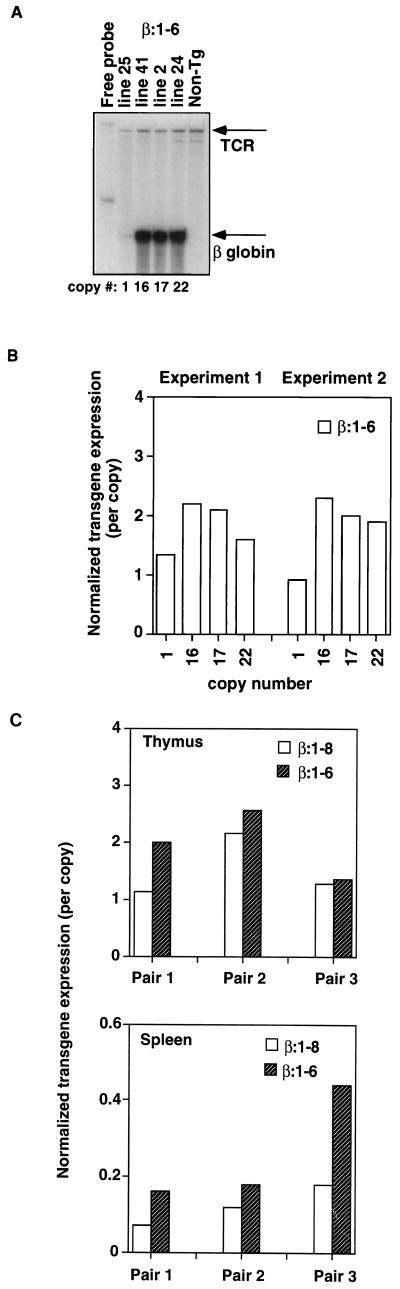

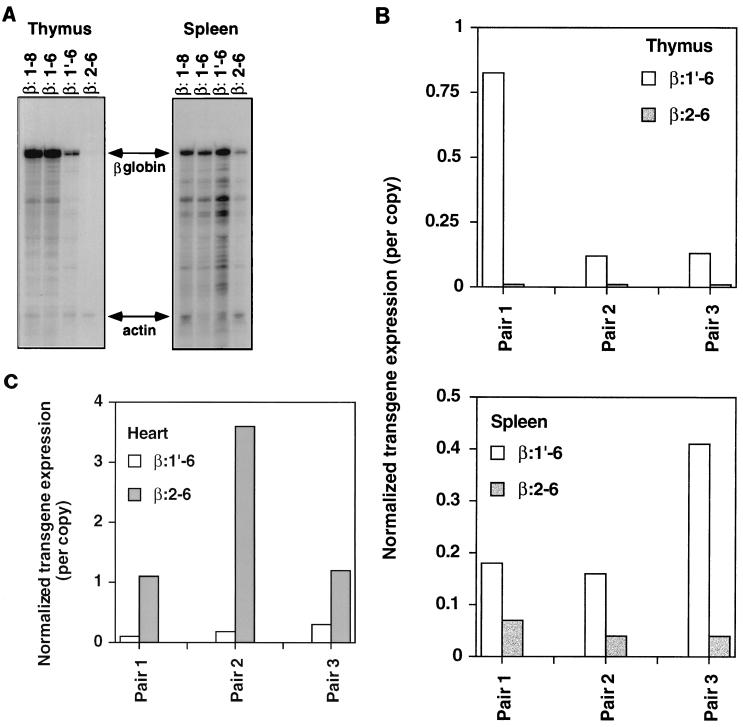

Expression of the reporter transgenes was assayed by RNase protection as described in Materials and Methods. Figure 2A shows that all four independent lines of β:1-6 mice of various copy numbers efficiently expressed the human β-globin mRNA in the thymus. PhosphorImager analysis, with endogenous TCRα or actin mRNA as an internal loading control, showed that transgene expression per copy was high and stable (only varying over a 2.3-fold range) across the independent lines. Expression levels range from one- to twofold of the endogenous mRNA control level (Fig. 2B). These data demonstrate that deletion of HS7 and -8 does not compromise the ability of the LCR to generate high-level, copy number-dependent transgene expression. Because silencer elements previously characterized by transient transfection reside in the deleted region (59), we compared the expression levels in organs of β:1-8 to β:1-6 transgenic mice in three pairs. Figure 2C shows PhosphorImager analysis of thymic and splenic expression in the three experiments. All three pairs display a minor to negligible negative effect of the HS7 and -8 region on transgene expression in thymus. Splenic expression of these transgenes shows a more reproducible but minor negative effect of this region ranging from 1.6- to 2.5-fold.

FIG. 2.

Copy number dependence of β:1-6 transgene transcription. (A) RNase protection assay with thymus RNA from four independent β:1-6 transgenic lines. Line numbers and their estimated relative copy number are indicated. Arrows indicate the signals from the human β-globin reporter transgene and endogenous TCRα signal. Migration of the full-length probes is shown in the probe lane. Non-Tg, nontransgenic. (B) PhosphorImager analysis of β:1-6 expression in thymus. RNase protection from experiment 1 is shown in panel A. Transgene expression was normalized to TCRα signal (defined as 1.0). Experiment 2 is a repeat of the previous experiment with different members of the same lines. Here, the transgene expression was normalized to the endogenous actin signal (see Materials and Methods), which is defined as 1.0 for this experiment. The ratio of transgene to endogenous control expression was then divided by the relative copy number to obtain the values presented. (C) Deletion of HS7 and -8 has a minor to negligible effect on transgene expression. PhosphorImager analysis of RNase protection assays. Thymus and spleen transgene expression was examined for three pairs of β:1-8 and β:1-6 transgenic mice. The relative β:1-8 and β:1-6 copy numbers are, respectively, as follows: pair 1, 2 and 16; pair 2, 21 and 17; and pair 3, 16 and 22. Transgene signal was normalized to endogenous actin signal (defined as 1.0) and divided by the copy number. Representative RNase protections are shown in Fig. 5A.

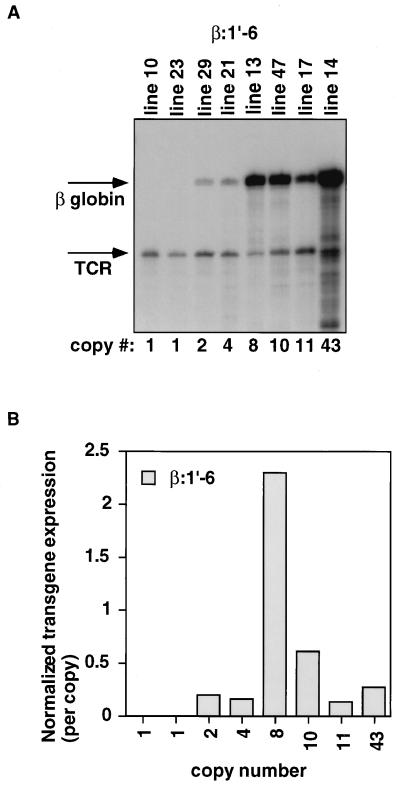

Eight lines of β:1′-6 mice were analyzed. All lines expressed the transgene in thymus (Fig. 3A). Longer exposures show low levels of transcripts (0.4 to 1.0% of the TCRα signal by PhosphorImager analysis) in the two single-copy lines (data not shown). Only one of the eight lines (no. 13) showed an expression level comparable to that of the β:1-6 transgene. Five others express between 14 and 60% of the endogenous TCRα signal per copy (Fig. 3). Among the multicopy lines, this construct has a 16-fold range of variation in expression level per copy. This indicates that copy number-dependent expression in thymus is compromised when the TCRα enhancer (HS1) is deleted. The much lower levels of expression of the two single-copy β:1′-6 lines further indicate an increased sensitivity to position effects in the absence of HS1 (11).

FIG. 3.

β:1′-6 transgene expression is present in all founders, but is not as copy number dependent as the β:1-6 construct. (A) RNase protection assay with thymus RNA from eight independent β:1′-6 transgenic lines. Line numbers and their estimated relative copy numbers are indicated. Arrows indicate the signals from the human β-globin reporter transgene and endogenous TCRα signal (defined as 1.0). (B) PhosphorImager analysis of the experiment shown in panel A. Transgene signal was normalized to endogenous TCRα signal and then divided by the copy number.

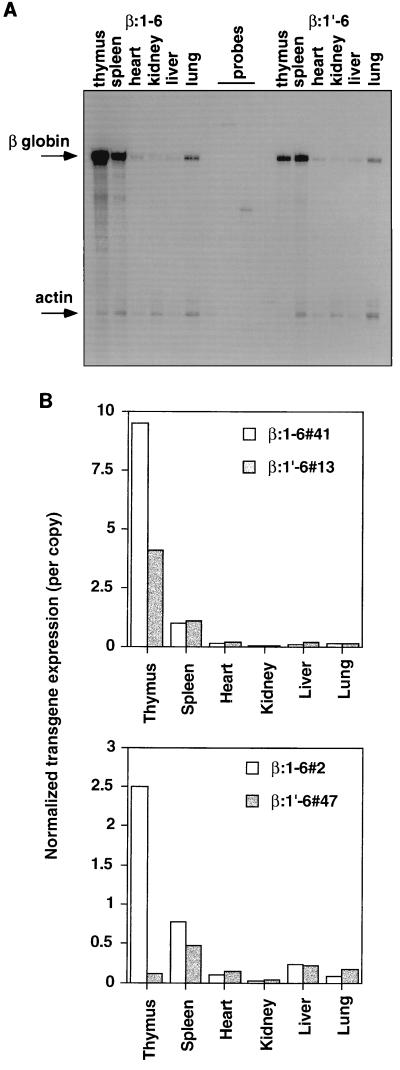

Analysis of the tissue distribution of β:1-6 and β:1′-6 transgene expression (Fig. 4) indicated that high-level expression of the former transgene was still restricted to thymus and spleen, as was the case for the full-length LCR transgene β:1-8 (45). Therefore the HS7 and -8 region does not appear to play a major role in the T-cell compartment specificity of TCRαLCR activity. However, deletion of the TCRα enhancer (HS1) results in a drop in thymic expression of the transgene. Surprisingly, splenic expression does not appear to be affected by the HS1 deletion. Nor is the silent to low-level expression in nonlymphoid organs altered by removal of the TCRα enhancer. Taken together, these data demonstrate that the silencer regions, containing HS7 and -8, participate negligibly in LCR activity at the whole-organ level. However, the HS1 (TCRα enhancer) region contributes to copy number-dependent expression and high-level thymic transgene expression.

FIG. 4.

Tissue distribution of β:1-6 and β:1′-6 transgene expression. (A) RNase protection assay on RNA from the indicated tissues of β:1-6 line 41 (16 copies) and β:1′-6 line 13 (8 copies) transgenic mice. Arrows indicate signals from the β-globin and endogenous actin control. (B) PhosphorImager analysis of the experiment shown in panel A and an additional experiment using other β:1-6 (line 2, 17 copies) and β:1′-6 (line 47, 10 copies) transgenic lines (lower panel). Transgene mRNA signal was normalized to that of endogenous actin control (defined as 1.0) and then divided by the copy number.

The HS1′ region profoundly alters tissue distribution of transgene expression.

Expression of the previously described β:2-6 transgene appears to be much more widespread than that of β:1′-6 (45). This indicates the presence of an important regulatory function in the HS1′ region. Indeed, comparison of expression levels in pairs of β:1′-6 and β:2-6 lines in some organs showed dramatic differences in transgene activity. Figure 5A shows an RNase protection assay done with thymus and spleen RNA of representative lines for each transgenic construct. In both organs, the negligible difference between β:1-8 and β:1-6 is evident (shown graphically in Fig. 2C). The drop in thymic expression and unaltered splenic expression (discussed above in the description of Fig. 4) between β:1-6 and β:1′-6 is also reproduced. Deletion of HS1′ causes a further, severe drop in thymic expression and a less severe, but significant, lowering of splenic transcription of the transgene. Because neither of these transgenes is perfectly copy number dependent in its expression, three separate pairs of lines were similarly analyzed to confirm these results. Figure 5B shows PhosphorImager analysis of these experiments. The drop in thymic expression resulting from HS1′ deletion ranges from 15- to 80-fold per copy, while splenic expression is lowered approximately 3- to 10-fold. These results are consistent regardless of how the lines are paired. Conversely, expression of the transgene in the heart rose due to HS1′ deletion (Fig. 5C). PhosphorImager analysis of the same three pairs of lines showed a 4- to 20-fold rise in the levels of heart transgene expression per copy. Again, the results are the same no matter how the strains are grouped. Expression of these transgenes in other organs was also investigated. Levels of transgene expression in liver, kidney, and lung were either inconsistently or not significantly affected by any of the deletions made in the multiple pairs of transgenic mice analyzed (data not shown). Nevertheless, together these data show that the removal of the HS1′ region results in a major alteration of the tissue distribution of transgene activity.

FIG. 5.

LCR HS deletion analysis. (A) RNase protection assays of the indicated organs of representative transgenic lines. The constructs are indicated. Relative copy numbers are as follows: β:1-8, 16; β:1-6, 22; β:1′-6, 43; and β:2-6, 28. Arrows indicate signals from human β-globin transgene mRNA and the endogenous actin control. (B) PhosphorImager analysis of RNase protection assays. Thymus and spleen transgene expression was examined for three pairs of β:1′-6 and β:2-6 transgenic mice. The relative β:1′-6 and β:2-6 copy numbers are, respectively, as follows: pair 1, 8 and 8; pair 2, 10 and 9; and pair 3, 43 and 28. Transgene signal was normalized to endogenous actin signal (defined as 1.0) and divided by the copy number. (C) PhosphorImager analysis of RNase protections performed with heart RNA from the same three pairs of transgenic mice used in panel B. Normalized transgene expression numbers were obtained as in panel B.

Tissue-differential chromatin structure is maintained in the β:1′-6 transgene.

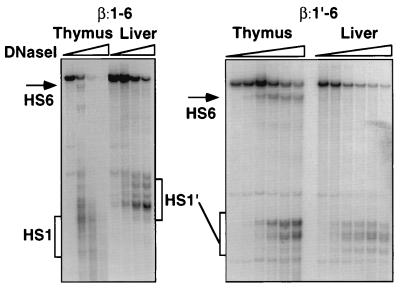

As described in the introduction, our previous work demonstrated that full-length LCR transgenes exhibit cell-type-specific chromatin structures similar to that of the endogenous TCRα locus (26, 45). To investigate the roles of the HS regions in the maintenance of tissue-differential chromatin structure, we analyzed the β:1-6 and β:1′-6 transgene loci by using the DNase I hypersensitivity assay. Figure 6 shows the results from a representative experiment with a β:1-6 transgenic line (left panel). As expected, this transgene contains a stronger HS6 in thymus than in liver. With the increased resolution afforded by smaller transgene fragments (4 kb less than in our study of the β:1-8 transgene [45]), it is now possible to see that HS1, which preferentially forms in thymus, is actually an HS cluster. HS1′ also appears to be a cluster of discrete HS. A small amount of hypersensitivity in the HS1′ region can be seen in thymic chromatin as well. Similar assays with β:1′-6 transgenic mice (Fig. 6, right panel) show that the differential DNase I hypersensitivity at HS6 is preserved in this transgene, despite the absence of HS1. The only minor difference between the HS patterns of β:1-6 and β:1′-6 is in the relative intensities of the individual members of the HS1′ cluster. The wide-open chromatin configuration in both thymus and liver that was evident in the β:2-6 transgene (45) does not materialize in either of the new transgenes. These data, together with those from our earlier studies, indicate that the HS1′ region contains an activity that maintains the tissue-differential chromatin structure at the HS2 to -6 region of the TCRα locus.

FIG. 6.

Chromatin structure analysis at transgene loci. (Left panel) DNase I hypersensitivity assay of the indicated organs of β:1-6 line 41 transgenic mice. The parent band is a SwaI-SacI restriction fragment of the transgene. The probe is to the 5′ end of the fragment. The positions of HS clusters are indicated by brackets or arrows. (Right panel) DNase I hypersensitivity assay of the indicated organs of β:1′-6 line 14 transgenic mice. The parent fragment was generated as in panel A and detected with the same probe. Slopes indicate increasing DNase I concentration (general range, 0.0 to 4.0 μg/ml).

HS1′ in the endogenous TCRα/δ gene locus.

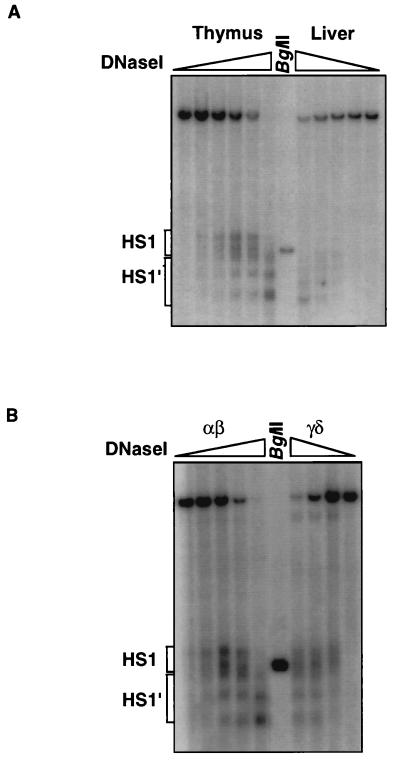

We previously had no evidence of HS1′ formation in thymic chromatin (26, 45). Therefore, we wanted to determine if this new detection of HS1′ was the direct result of a loss of some activity in HS7 and -8, or was merely a result of the increased resolution that arises from examination of smaller restriction fragments. Given its apparent activity in our transcription assays, it became important to us to establish if HS1′ could form in the endogenous TCRαLCR. We examined this by performing a higher-resolution DNase I hypersensitivity assay with a restriction enzyme and a probe that detects the HS1 and HS1′ region on a smaller fragment (approximately 3 kb). Figure 7A shows that, in thymic chromatin, HS1 forms preferentially, but HS1′ does appear at higher DNase titration points. This HS1′ appears equivalent to that formed in liver chromatin. Because αβ T cells rearrange and express the TCRα chain gene while γδ T cells rearrange and express the TCRδ chain gene, it then became of interest to determine if these two HS clusters had any differential activity in these two populations. Figure 7B shows that the DNase I hypersensitivity pattern in thymocytes (99% αβ T cells) is equivalent to that formed in γδ T cells isolated from mouse lymph nodes. HS1 forms first, followed by HS1′ forming at higher DNase concentrations. This indicates that both of these HS clusters may have a common role to play in both TCRα and TCRδ chain expression in αβ and γδ T cells, respectively.

FIG. 7.

Analysis of chromatin structure at the endogenous TCRαLCR. (A) DNase I hypersensitivity assay of the indicated organs from nontransgenic C57BL6/J mice. The parental band is an EcoRV restriction fragment of the TCRαLCR region. The probe is to the 3′ end of the fragment. HS clusters are indicated with brackets. (B) Similar assay with αβ thymocytes and γδ T cells isolated as described in Materials and Methods (99% purity). Slopes indicate increasing DNase I concentration. The middle lane (labeled BglII) contains EcoRV-BglII codigested genomic DNA. The BglII site is 15 nucleotides 5′ of the PmlI site and marks the junction of the HS1 and HS1′ clusters.

DISCUSSION

The examination of gene expression in the context of chromatin in both transgenic mice and in cell culture has led to the identification of cis-acting elements that do not necessarily have activity in transient reporter gene transcription assays. LCRs are perhaps the most obvious example of this, but activities in chromatin have also been ascribed to enhancer elements (4, 56), matrix-attachment regions (28), facilitator elements (2), boundary elements (8, 37, 62), and CpG methylation islands (61). The HS1′ element described here is yet another example of a cryptic cis-acting control element revealed through the study of gene expression in chromatin. Characterization of activities such as these is essential to understanding the molecular mechanisms governing tissue-specific gene expression and cell type differentiation in vivo.

Besides TCRα, LCRs have been described in many other tissue-specifically expressed gene loci (reviewed in references 19 and 32). These LCRs have all been shown to drive tissue-specific expression of linked transgenes in mice and/or cell lines. Thus, LCRs are thought to be important to the development of tissue-specific gene expression. What provides tissue specificity to LCR function is not clear, although many of these LCRs contain within them elements with tissue-restricted classical enhancer activity (3, 5, 31, 34, 38, 55). Several studies have documented the ability of enhancer elements to counteract repressive chromatin structures as a component of their action (4, 29, 56). Therefore, a reasonable presumption would be that these enhancer elements have a role to play in tissue-specific chromatin opening and LCR function. The TCRαLCR, with its apparently unique layout of separable chromatin opening and tissue-specificity regions (the latter containing a T-cell-specific enhancer), has afforded us an excellent opportunity to examine this question.

The HS1-to-6 region is the TCRαLCR.

Deletion analysis of the full-length, HS1 to -8-containing LCR has demonstrated that the TCRα silencer containing the HS7 and -8 region is not required for LCR activity and only has a minor to negligible effect on lymphoid organ reporter gene expression. Because the silencer activity is postulated to have a role in silencing the TCRα enhancer in the rare subpopulation of γδ T cells, it is not too surprising that its effect seems minimal at the whole-organ level (59). The TCRα enhancer contained in HS1, however, is part of the LCR. It contributes to high-level thymic expression and copy-number-dependent transcription. The range of variation in expression levels per copy increases significantly in multicopy lines upon HS1 deletion. Furthermore, because single-copy transgenes are very sensitive to position effects without a complete LCR (11), the severe drop in thymic expression from single-copy β:1′-6 transgenes further indicates a requirement for the activity in HS1 for LCR function. Curiously, HS1 appears to be nonfunctional in the spleen, which is roughly 30% mature T cells. It is possible that the TCRα enhancer is not required for expression of the reporter gene in mature T cells. There is ample precedent for such a finding. The mouse CD8α (12, 27), CD4 (49), and p56lck (57) genes all have transcriptional control elements that are functional in immature, thymic T cells, but not in peripheral, mature T cells. However, formal demonstration of TCRα inactivity in peripheral T cells would require examination of isolated peripheral T cells from β:1-6 and β:1′-6 mice. From these data, we conclude that the 7.4-kb HS1 to -6 fragment contains the full-length T-cell compartment-specific LCR.

HS1′: a region influencing T-cell compartment-specific LCR activity.

Given the wealth of data suggesting a role for enhancers in remodeling chromatin, it was surprising to find that deletion of the TCRα enhancer had no gross effect on the cell-type-specific chromatin structures observed in β:1′-6 mice. These structures are similar to those formed at the endogenous LCR. Further deletion of the activity in the HS1′ region abolishes these chromatin configurations in favor of the wide-open, non-tissue-specific structures observed in β:2-6 transgenic mice (45). This HS1′ element increases thymic and splenic expression while suppressing ectopic expression of the reporter gene in the heart. Altogether, the data in the present study clarify the difference in observed expression patterns between the β:1-8 and β:2-6 transgenes reported in our previous work (45). The change consists of a rise in expression in the heart and a severe drop in expression in the thymus and spleen, to levels at or below that of basal activity in the other nonlymphoid organs. This results from the deletion of the T-cell-specific enhancer in HS1 and the removal of the complex activity in HS1′. Why does the suppressive aspect of HS1′ element activity only manifest itself in the heart, and not the other nonlymphoid organs, in this system? One likely possibility is that it is due to the organ bias of the β-globin reporter gene. Our previous work has shown that β:2-6-driven transgene expression in the heart is 10- to 20-fold higher than that in the other nonlymphoid organs (45). Since the β-globin transcription unit is considered to be erythrocyte specific in its expression (6, 23, 54), the expression we see in other organs under the influence of HS2 to -6 is most likely due to the wide-open state of the transcription unit (45). This would allow the transcriptional regulatory machinery of the various organs maximum access to the β-globin regulatory sequences. The heart appears to have a higher capacity than the other organs for taking advantage of this open state of the transgene to drive expression. This may be due to differences the in abundance of transcription factors able to act on the β-globin fragment. There is evidence that changes in chromatin structure can occur without a concomitant increase in transcription if the nuclear factor environment does not favor it. Several studies suggest that changes in chromatin structure can precede transcriptional activation (30, 50). It is possible that, were the reporter gene naturally ubiquitously expressed, HS1′ deletion would have caused more widespread ectopic expression. Formal demonstration of the full suppressive potential of the HS1′ element would require the use of a more uniformly expressed transcription unit than β-globin as a reporter gene. Nevertheless, it is clear that removal of the HS1′ element from the LCR dramatically alters the tissue distribution of transgene expression.

The TCRα enhancer region and its vicinity have been extensively studied both in vitro (4, 20, 41) and in vivo (24, 25, 48, 58). No enhancer or silencer activity has ever been detected in the HS1′ region. Furthermore, the HS1′ region was demonstrated to not contain an enhancer activity independent of the HS1 region (see Fig. 1A, construct J21-3′Cα, in reference 58). This makes the mechanism of action of the element contained therein an interesting question for investigation. There is extensive sequence homology in the HS1 and HS1′ regions between mouse and human loci (33). In one report, the human sequence which partially corresponds to the HS1 and HS1′ areas seemed to restrict V-D-J rearrangement of a transgenic recombination substrate to αβ T cells. The substrate containing the core TCRα enhancer (HS1 equivalent) was rearranged in both αβ and γδ T cells (48). Although transcription and chromatin structure were not examined in that report, this finding does suggest that the human TCRα locus may have an enhancer flanking activity similar to that which we describe here.

The role of the HS1′ region in the endogenous TCRαδ Dad1 locus.

Having determined that HS1′ does form in thymocyte chromatin along with HS1, it was tempting to speculate that perhaps some differential activity of these regions in αβ versus γδ T cells might play a role in the differential development of the two populations. However, our finding that both regions are hypersensitive to DNase in both primary αβ and γδ T cells suggests that both of these elements are active in both cell types and may play a common role in either lineage. TCRα enhancer region knockout mice have been generated and analyzed (52). This mutation affected both TCRα and TCRδ expression in αβ and γδ T cells, respectively. Our data are in agreement with this finding. However, the deleted region includes both the HS1 and HS1′ regions of the LCR, and it is difficult to discern the roles of the individual HS clusters from this knockout strain. The work of Roberts et al. (48), as discussed above, does raise the possibility that the HS1′ region may function in restricting TCRα rearrangement to αβ T cells. Generation of an HS1′-knockout mouse strain will be necessary to address this question.

The activity of the HS1′ element and its position between the T-cell-specific enhancer (HS1) and the chromatin opening activity (HS2 to -6) suggest that it may play a role in separating TCRα and Dad1 gene regulation. It could accomplish this if it contained a boundary-like element capable of blocking and/or directing transcriptional control activities (8, 37, 62). However, the complex activity contained in HS1′ suggests that this 1-kb region constitutes more than simply a boundary between the two genes. TCRα also needs access to the chromatin opening activity in the HS2 to -6 region to drive its high-level expression (9, 26, 45). Therefore, some mechanism of tissue-specific bypassing of a boundary element would be necessary in the locus. Further studies of this unusual control element may shed light on the molecular entities that separate the regulation of juxtaposed genes in the mammalian genome.

Comparisons and contrasts with other tissue-specific LCRs.

The β-globin LCR is the best-characterized LCR to date (reviewed in references 10, 13, 40, and 44). It consists of four HS located 6 to 22 kb upstream of the fetal ɛ-globin gene. LCR activity has been mapped to a combination of four core fragments of each HS (19). HS2 contains the classical enhancer activity, while HS3 contains the dominant chromatin opening activity responsible for position independence (11). We have sought to identify the activities of the HS clusters of the TCRαLCR. The HS1′ element appears to contribute to tissue-differential chromatin structure and expression of the reporter transgene. Could a similar element exist in other LCRs? The β-globin HS3 core element appears to be tissue specific in function, at least in fetal life (53). An HS1′-like element may coexist with chromatin opening elements in this small region. It is also possible that the TCRαLCR’s proximity to the ubiquitously expressed Dad1 gene creates a special requirement for separable chromatin opening and tissue-specific functions in this LCR that might not be necessary at other loci. Further mutational analysis, in vivo identification of factors interacting with the HS1′ region, and comparison to other systems should lead to a better understanding of tissue-specific LCR function. This, in turn, should illuminate molecular mechanisms involved in the development of tissue-specific gene expression.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank D. Kioussis for the human β-globin reporter gene fragment, Peter Schow for expert flow cytometry services, and Buyung Santoso for technical assistance. We thank Bill Sha, Jeanne Baker, Herb Kasler, and Jeff Wallin for critical reading of the manuscript.

B.D.O. was supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from the National Science Foundation. A.W. is an NSF Presidential Faculty Fellow. This work was supported by NIH grant AI-31558 to A.W.

REFERENCES

- 1.Apte S S, Mattei M G, Seldin M F, Olsen B R. The highly conserved defender against the death 1 (DAD1) gene maps to human chromosome 14q11-q12 and mouse chromosome 14 and has plant and nematode homologues. FEBS Lett. 1995;323:304–306. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00321-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aronow B J, Ebert C A, Valerius M T, Potter S S, Wiginton D A, Witte D P, Hutton J J. Dissecting a locus control region: facilitation of enhancer function by extended enhancer-flanking sequences. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:1123–1135. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.2.1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aronow B J, Silbiger R N, Dusing M R, Stock J L, Yager K L, Potter S S, Hutton J J, Wiginton D A. Functional analysis of the human adenosine deaminase gene thymic regulatory region and its ability to generate position-independent transgene expression. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:4170–4185. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.9.4170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bagga R, Emerson B M. An HMG I/Y-containing repressor complex and supercoiled DNA topology are critical for long-range enhancer dependent transcription in vitro. Genes Dev. 1997;11:629–639. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.5.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bonifer C, Yannoutsos N, Kruger G, Grosveld F, Sippel A E. Dissection of the locus control function located on the chicken lysozyme gene domain in transgenic mice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4202–4210. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.20.4202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chada K, Magram J, Raphael K, Radice G, Lacy E, Costantini F. Specific expression of a foreign beta-globin gene in erythroid cells of transgenic mice. Nature. 1985;314:377–380. doi: 10.1038/314377a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chomczynski P, Sacchi N. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal Biochem. 1987;162:156–159. doi: 10.1006/abio.1987.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chung J H, Whiteley M, Felsenfeld G. A 5′ element of the chicken beta-globin domain serves as an insulator in human erythroid cells and protects against position effect in Drosophila. Cell. 1993;74:505–514. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)80052-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Diaz P W, Cado D, Winoto A. A locus control region in the T cell receptor alpha/delta locus. Immunity. 1994;1:207–217. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(94)90099-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dillon N, Grosveld F. Transcriptional regulation of multigene loci: multilevel control. Trends Genet. 1993;9:134–137. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(93)90208-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ellis J, Tan-Un K C, Harper A, Michalovich D, Yannoutsos N, Philipsen S, Grosveld F. A dominant chromatin-opening activity in 5′ hypersensitive site 3 of the human beta-globin locus control region. EMBO J. 1996;15:562–568. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ellmeier W, Sunshine M J, Losos K, Hatam F, Littman D R. An enhancer that directs lineage-specific expression of CD8 in positively selected thymocytes and mature T cells. Immunity. 1997;7:537–547. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80375-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Engel J D. Developmental regulation of human beta-globin gene transcription: a switch of loyalties? Trends Genet. 1993;9:304–309. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(93)90248-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Enoch T, Zinn K, Maniatis T. Activation of the human β-interferon gene requires an interferon-inducible factor. Mol Cell Biol. 1986;6:801–810. doi: 10.1128/mcb.6.3.801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Enver T, Brewer A C, Patient R K. Simian virus 40-mediated cis induction of the Xenopus beta-globin DNase I hypersensitive site. Nature. 1985;318:680–683. doi: 10.1038/318680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Felsenfeld G. Chromatin as an essential part of the transcriptional mechanism. Nature. 1992;355:219–224. doi: 10.1038/355219a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Festenstein R, Tolaini M, Corbella P, Mamalaki C, Parrington J, Fox M, Miliou A, Jones M, Kioussis D. Locus control region function and heterochromatin-induced position effect variegation. Science. 1996;271:1123–1125. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5252.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Forrester W C, Epner E, Driscoll M C, Enver T, Brice M, Papayannopoulou T, Groudine M. A deletion of the human β-globin locus activating region causes a major alteration in chromatin structure and replication across the entire β-globin locus. Genes Dev. 1990;4:1637–1649. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.10.1637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fraser P, Grosveld F. Locus control regions, chromatin activation and transcription. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1998;10:361–365. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(98)80012-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Giese K, Kingsley C, Kirshner J R, Grosschedl R. Assembly and function of a TCRα enhancer complex is dependent on LEF-1 induced DNA bending and multiple protein-protein interactions. Genes Dev. 1995;9:995–1008. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.8.995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gilman M. Ribonuclease protection assay. In: Ausubel F M, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seidman J G, Smith J A, Struhl K, editors. Current protocols in molecular biology. New York, N.Y: John Wiley and Sons; 1991. pp. 4.7.1–4.7.8. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Greaves D R, Wilson F D, Lang G, Kioussis D. Human CD2 3′-flanking sequences confer high-level, T cell-specific, position-independent gene expression in transgenic mice. Cell. 1989;56:979–986. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90631-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grosveld F, Blom van Assendelft G, Greaves D R, Kollias G. Position independent, high-level expression of the human β-globin gene in transgenic mice. Cell. 1987;51:975–985. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90584-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hernandez-Munain C, Roberts J L, Krangel M S. Cooperation among multiple transcription factors is required for access to minimal T-cell receptor α-enhancer chromatin in vivo. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:3223–3233. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.6.3223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ho I C, Yang L H, Morle G, Leiden J M. A T-cell specific transcriptional enhancer element 3′ of C alpha in the human T-cell receptor alpha locus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:6714–6718. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.17.6714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hong N A, Cado D, Mitchell J, Ortiz B D, Hsieh S N, Winoto A. A targeted mutation at the T-cell receptor α/δ locus impairs T-cell development and reveals the presence of the nearby antiapoptosis gene Dad1. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:2151–2157. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.4.2151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hostert A, Tolaini M, Roderick K, Harker N, Norton T, Kioussis D. A region in the CD8 gene locus that directs expression to the mature CD8 T cell subset in transgenic mice. Immunity. 1997;7:525–536. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80374-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jenuwein T, Forrester W C, Fernandez-Herrero L A, Laible G, Dull M, Grosschedl R. Extension of chromatin accessibility by nuclear matrix attachment regions. Nature. 1997;385:269–272. doi: 10.1038/385269a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jenuwein T, Forrester W C, Qiu R G, Grosschedl R. The immunoglobulin mu enhancer core establishes local factor access in nuclear chromatin independent of transcriptional stimulation. Genes Dev. 1993;7:2016–2032. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.10.2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jimenez G, Griffiths S D, Ford A M, Greaves M F, Enver T. Activation of the beta-globin locus control region precedes commitment to the erythroid lineage. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:10618–10622. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.22.10618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jones B K, Monks B R, Liebhaber S A, Cooke N E. The human growth hormone gene is regulated by a multicomponent locus control region. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:7010–7021. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.12.7010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kioussis D, Festenstein R. Locus control regions: overcoming heterochromatin-induced gene inactivation in mammals. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1997;7:614–619. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(97)80008-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koop B F, Rowen L, Wang K, Kuo C L, Seto D, Lenstra J A, Howard S, Shan W, Deshpande P, Hood L. The human T-cell receptor TCRAC/TCRDC (Cα/Cδ) region: organization, sequence and evolution of 97.6 kb of DNA. Genomics. 1994;19:478–493. doi: 10.1006/geno.1994.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lake R A, Wotton D, Owen M J. A 3′ transcriptional enhancer regulates tissue-specific expression of the human CD2 gene. EMBO J. 1990;9:3129–3136. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07510.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lang G, Wotton D, Owen M J, Sewell W A, Brown M H, Mason D Y, Crumpton M J, Kioussis D. The structure of the human CD2 gene and its expression in transgenic mice. EMBO J. 1988;7:1675–1682. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb02995.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Leiden J M. Transcriptional regulation of T cell receptor genes. Annu Rev Immunol. 1993;11:539–570. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.11.040193.002543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li Q, Stamatoyannopoulos G. Hypersensitive site 5 of the human beta globin locus control region functions as a chromatin insulator. Blood. 1994;84:1399–1401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Madisen L, Groudine M. Identification of a locus control region in the immunoglobulin heavy-chain locus that deregulates c-myc expression in plasmacytoma and Burkitt’s lymphoma cells. Genes Dev. 1994;8:2212–2226. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.18.2212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mage M G. Fractionation of T cells and B cells. In: Coligan J E, Kruisbeek A M, Margulies D H, Shevach E M, Strober W, editors. Current protocols in immunology. Vol. 1. New York, N.Y: John Wiley and Sons; 1994. pp. 3.5.1–3.5.6. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Martin D I K, Fiering S, Groudine M. Regulation of beta-globin gene expression: straightening out the locus. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1996;6:488–495. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(96)80072-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mayall T P, Sheridan P L, Montminy M R, Jones K A. Distinct roles for P-CREB and LEF-1 in TCRα enhancer assembly and activation on chromatin templates in vitro. Genes Dev. 1997;11:887–899. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.7.887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Milot E, Strouboulis J, Trimborn T, Wijgerde M, de Boer E, Langeveld A, Tan-Un K, Vergeer W, Yannoutsos N, Grosveld F, Fraser P. Heterochromatin effects on the frequency and duration of LCR-mediated gene transcription. Cell. 1996;87:105–114. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81327-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mombaerts P, Clarke A R, Rudnicki M A, Iacomini J, Itohara S, Lafailee J J, Wang L, Ichikawa Y, Jaenish R, Hooper M L, Tonegawa S. Mutations in T-cell antigen receptor genes alpha and beta block thymocyte development at different stages. Nature. 1992;360:225–231. doi: 10.1038/360225a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Orkin S H. Regulation of globin gene expression in erythroid cells. Eur J Biochem. 1995;231:271–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.tb20697.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ortiz B D, Cado D, Chen V, Diaz P W, Winoto A. Adjacent DNA elements dominantly restrict the ubiquitous activity of a novel chromatin-opening region to specific tissues. EMBO J. 1997;16:5037–5045. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.16.5037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Palmiter R D, Brinster R L. Germ-line transformation of mice. Annu Rev Genet. 1986;20:465–499. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.20.120186.002341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Philipsen S, Pruzina S, Grosveld F. The minimal requirements for activity in transgenic mice of hypersensitive site 3 of the beta globin locus control region. EMBO J. 1993;12:1077–1085. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05749.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Roberts J L, Lauzurica P, Krangel M S. Developmental regulation of VDJ recombination by the core fragment of the T-cell receptor alpha enhancer. J Exp Med. 1997;185:131–140. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.1.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Salmon P, Boyer O, Lores P, Jami J, Klantzmann D. Characterization of an intronless CD4 minigene expressed in mature CD4 and CD8 T cells, but not expressed in immature thymocytes. J Immunol. 1996;156:1873–1879. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Siebenlist U, Durand D B, Bressler P, Holbrook N J, Norris C A, Kamoun M, Kant J A, Crabtree G R. Promoter region of interleukin-2 gene undergoes chromatin structure changes and confers inducibility on a chloramphenicol acetyltransferase gene during activation of T cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1986;6:3042–3049. doi: 10.1128/mcb.6.9.3042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Siebenlist U, Hennighausen L, Battey J, Leder P. Chromatin structure and protein binding in the putative regulatory region of the c-myc gene in Burkitt lymphoma. Cell. 1984;37:381–391. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90368-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sleckman B P, Bardon C G, Ferrini R, Davidson L, Alt F W. Function of the TCRα enhancer in αβ and γδ T cells. Immunity. 1997;7:505–515. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80372-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tewari R, Gillemans N, Harper A, Wijgerde M, Zafarana G, Drabek D, Grosveld F, Philipsen S. The human β-globin locus control region confers an early embryonic, erythroid-specific expression pattern to a basic promoter driving the bacterial lacZ gene. Development. 1996;122:3991–3999. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.12.3991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Townes T M, Lingrel J B, Chen H Y, Brinster R L, Palmiter R D. Erythroid-specific expression of human β-globin genes in transgenic mice. EMBO J. 1985;4:1715–1723. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1985.tb03841.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tuan D Y H, Solomon W B, London I M, Lee D P. An erythroid-specific, developmental-stage-independent enhancer far upstream of the human ‘β-like globin’ genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:2554–2558. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.8.2554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Walters M C, Magis W, Fiering S, Eidemiller J, Scalzo D, Groudine M, Martin D I K. Transcriptional enhancers act in cis to suppress position-effect variegation. Genes Dev. 1996;10:185–195. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wildin R S, Garvin A M, Pawar S, Lewis D B, Abraham K M, Forbush K A, Ziegler S F, Allen J M, Perlmutter R M. Developmental regulation of lck gene expression in T lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1991;173:383–393. doi: 10.1084/jem.173.2.383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Winoto A, Baltimore D. A novel, inducible and T cell-specific enhancer located at the 3′ end of the T cell receptor alpha locus. EMBO J. 1989;8:729–733. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb03432.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Winoto A, Baltimore D. Alpha beta lineage-specific expression of the alpha T cell receptor gene by nearby silencers. Cell. 1989;59:649–655. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90010-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wu C. Analysis of hypersensitive sites in chromatin. Methods Enzymol. 1989;170:269–289. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(89)70052-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wutz A, Smrzka O W, Schweifer N, Schellander K, Wagner E F, Barlow D P. Imprinted expression of the Igf2r gene depends on an intronic CpG island. Nature. 1997;389:745–749. doi: 10.1038/39631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhong X P, Krangel M S. An enhancer blocking element between α and δ gene segments within the human T-cell receptor α/δ locus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:5219–5224. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.10.5219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]