Abstract

STUDY QUESTION

Which outcomes and outcome measures are reported in interventional trials evaluating the treatment of adenomyosis?

SUMMARY ANSWER

We identified 38 studies, reporting on 203 outcomes using 133 outcome measures.

WHAT IS KNOWN ALREADY

Heterogeneity in outcome evaluation and reporting has been demonstrated for several gynaecological conditions and in fertility studies. In adenomyosis, previous systematic reviews have failed to perform a quantitative analysis for central outcomes, due to variations in outcome reporting and measuring.

STUDY DESIGN, SIZE, DURATION

A systematic search of Embase, Medline and Cochrane Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) was performed with a timeframe from 1950 until February 2021, following the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis (PRISMA).

PARTICIPANTS/MATERIALS, SETTING, METHODS

Studies reporting on any uterus-sparing intervention to treat adenomyosis, both prospective and retrospective, were eligible for inclusion. Inclusion criteria were a clear definition of diagnostic criteria for adenomyosis and the modality used to make the diagnosis, a clear description of the intervention, a follow-up time of ≥6 months, a study population of n ≥ 20, a follow-up rate of at least 80%, and English language. The population included premenopausal women with adenomyosis. Risk of bias was assessed using the Evidence Project risk of bias tool.

MAIN RESULTS AND THE ROLE OF CHANCE

We included 38 studies (6 randomized controlled trials and 32 cohort studies), including 5175 participants with adenomyosis. The studies described 10 interventions and reported on 203 outcomes, including 43 classified as harms, in 29 predefined domains. Dysmenorrhoea (reported in 82%), heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB) (in 79%) and uterine volume (in 71%) were the most common outcomes. Fourteen different outcome measures were used for dysmenorrhoea and 17 for HMB. Quality of life was reported in 9 (24%) studies, patient satisfaction with treatment in 1 (3%). A clear primary outcome was stated in only 18%.

LIMITATIONS, REASONS FOR CAUTION

This review includes studies with a high risk of bias.

WIDER IMPLICATIONS OF THE FINDINGS

Shortcomings in the definition and choice of outcomes and outcome measures limit the value of the conducted research. The development and implementation of a core outcome set (COS) for interventional studies in adenomyosis could improve research quality. This review suggests a lack of patient-centred research in adenomyosis and people with adenomyosis should be involved in the development and implementation of the COS.

STUDY FUNDING/COMPETING INTERESTS

No funds specifically for this work were received. T.T. receives fees from General Electrics for lectures on ultrasound independently of this project.

TRIAL REGISTRATION NUMBER

This review is registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO; registration number CRD42020177466) and the Core Outcome Measures in Effectiveness Trials (COMET) initiative (registration number 1649).

Keywords: outcome reporting, methodology, research, adenomyosis, core outcome sets, uterine-sparing intervention, gynaecological conditions

WHAT DOES THIS MEAN FOR PATIENTS?

A treatment for a disease is developed and tested in research studies, to find out how effective the treatment is and to make sure it is safe. Researchers do this by measuring how a treatment changes so-called ‘outcomes’. Examples for outcomes could be pain or bleeding. It is important that the measured outcomes are relevant to the patients that are treated, and that they are measured with tools that are reliable. Also, the outcomes and measuring tools should be the same in all studies on the same disease, so that studies can be compared with each other.

In our work, we investigated the nature of outcomes that were reported in trials on the treatment of adenomyosis, a common benign disease of the uterus.

We found that the reported outcomes are largely focused on menstrual symptoms and uterine size, with only a minority of studies reporting outcomes relating to fertility or quality of life. Furthermore, the outcomes were measured with different types of measuring instruments, which made it difficult to compare studies. This inconsistent outcome reporting and measuring prevents clinicians to determine which treatments are best and should be recommended to patients with adenomyosis.

We recommend the development of a set of outcomes that should be measured and reported in all future trials on adenomyosis. This work needs to include input from all relevant stakeholders, especially people with adenomyosis.

Introduction

Adenomyosis is a common benign disease of the uterus that can be found in 20–70% of patients, depending on the characteristics of study populations (Upson and Missmer, 2020). Despite its reported negative impact on quality of life (QOL), fertility and obstetric outcomes (Harada et al., 2019; Horton et al., 2019; Upson and Missmer, 2020), data on the efficacy of treatments for adenomyosis are lacking. Systematic reviews evaluating interventions for adenomyosis have been unable to perform quantitative data-synthesis of commonly reported outcomes, such as abnormal uterine bleeding, due to the variation in outcome reporting (de Bruijn et al., 2017; Abbas et al., 2020). These reviews highlighted a significant variation in both the definition and measurement of outcomes, thereby preventing useful comparison of treatment outcomes. Variations in outcome reporting and measurements also contribute to the exaggeration of treatment effects and reporting bias by omitting unfavourable data (Duffy et al., 2017). For example, there is a controversy regarding the extent to which surgery could improve fertility outcomes in patients with adenomyosis. As reporting of fertility and obstetric outcomes is highly selective, the success of treatment is interpreted differently by the authors, with the risk of being overstated (Abbott, 2017; Dueholm, 2017).

Carefully selected outcomes and outcome measures can enhance research quality, increase the relevance of research results for the people treated for a condition, and reduce research waste. There is a growing consensus that the use of standardized or ‘core’ outcome sets in clinical trials would improve research into womens’ health. Such examples are published consensus on core outcomes in endometriosis research or fertility reporting (Duffy et al., 2020, 2021). There is currently no consensus amongst key stakeholders regarding which outcomes should be measured in trials assessing interventions for adenomyosis-related symptoms. A collection of 84 editors of women’s health journals, including the Cochrane Gynaecology and Fertility Group, have formed a consortium to support core outcome sets (COSs): the Core Outcomes in Women’s Health (CROWN) (Khan, 2016). The Core Outcome Set in Adenomyosis Research (COSAR) initiative aims to develop a COS for studies investigating therapeutic interventions for adenomyosis in conjunction with the CROWN-network.

As part of this work, the aim of the present review was to develop an inventory and systematically evaluate the outcomes and outcome measures reported in clinical trials investigating the treatment of adenomyosis.

Materials and methods

This review is registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO; CRD42020177466) and reports in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) statement (Liberati et al., 2009). COSAR is registered with the Core Outcome Measures in Effectiveness Trials (COMET) initiative (registration number 1649). No approval from the institutional review board or ethics committee was sought owing to the nature of this work.

Literature search

The literature search was performed with support from a trained medical librarian. The electronic databases Medline, Embase and Cochrane Register of Controlled Trials were searched using the terms ‘adenomyosis’ and ‘treatment’, as well as a range of treatment-specific key words that were identified through a pilot search. The electronic search strategy is presented in Supplementary Data S1. The time range was from 1950 until February 2021. In addition, the reference lists of included articles and identified reviews on the topic were scanned, and manually searched for further studies.

Study selection

Studies reporting on any uterus-sparing intervention to treat adenomyosis, of any study design, both prospective and retrospective, were eligible for inclusion. Inclusion criteria were a study population comprising ≥20 women, a clear description of the modality and diagnostic criteria used to diagnose adenomyosis, a clear description of the intervention, follow-up time ≥6 months, loss to follow-up <20% and English language. Exclusion criteria included data presented in short communications, reviews, letters to the editors and congress abstracts. Studies with experimental design (e.g. performed on tissue samples or looking exclusively at molecular markers) or fundamental design flaws (unclear intervention) were also excluded. Two researchers (T.T. and M.O.) independently screened the retrieved titles and abstracts using the Rayyan application (Ouzzani et al., 2016). Potentially eligible studies were retrieved in full text for the assessment of their eligibility. Their methodological quality was independently assessed by two researchers (T.T. and M.O.) using the Evidence project risk of bias tool (Kennedy et al., 2019). The signalling questions were answered with ‘yes’, ‘no’, ‘not reported’ or ‘not applicable’. At each step, conflicting decisions were resolved through discussion.

The quality of outcome reporting was assessed by T.T. and M.O. using the Management of Otitis Media with Effusion in Cleft Palate (MOMENT) criteria (Harman et al., 2013), as described previously (Hirsch et al., 2016; Pergialiotis et al., 2018). One point was given for each of the following six domains: whether a primary outcome was clearly stated; whether the primary outcome was clearly defined for reproducible measures; whether the secondary outcomes were clearly stated; whether the secondary outcomes were clearly defined for reproducible measures; whether the authors explain the choice of outcome; whether the methods that were used were appropriate to enhance the quality of measures. We awarded a point for stating a primary outcome even if multiple primary outcomes were described. We did not award a point for a clear definition of the primary outcome if no primary outcome was stated. When most of the secondary outcomes were clearly defined for reproducible measures, we awarded a point even if not all secondary outcomes were clearly described. We did not award a point under the last domain if the study was retrospective and if it was not described how the outcomes were documented.

Data extraction and analysis

The data extraction was performed by T.T. and M.O. First author, year of publication, country of origin, study design, number of participants with adenomyosis and type of intervention were noted. We also recorded whether a sample size calculation was carried out. Outcomes were documented as primary or secondary outcomes, according to how they were classified in the Materials and method (M&M) section. Generic statements found in the title or abstract, such as ‘efficacy’ or ‘clinical effect’, that were not further specified in the manuscript, were not regarded as (primary) outcomes. Outcomes that were described in the result section or the discussion, but not defined in the M&M section as outcomes, were still included as secondary outcomes in the synthesis. As this was a recurring problem, the authors found that it would not reflect the reporting of outcomes if only the outcomes mentioned in the M&M section were included. The outcome measure and, if given, the definition was recorded, as well as the time points of outcome measuring and reporting. The outcomes were classified to core areas and domains according to a taxonomy recommended by COMET (Dodd et al., 2018). Composite outcomes, such as QOL, were reported with each item classified to the respective domain.

Results from this review are presented as percentages. Means and SD are calculated for normally distributed data. Distribution of data within the samples was assessed by analysing skewness and kurtosis. Associations between date of publication and quality of outcomes were analysed using linear regression. Probability values were rounded to two decimal places, with the exception of P < 0.001. Data analysis was performed using Microsoft Excel software (Version 2102, Microsoft Corporation, Redmont, USA).

Results

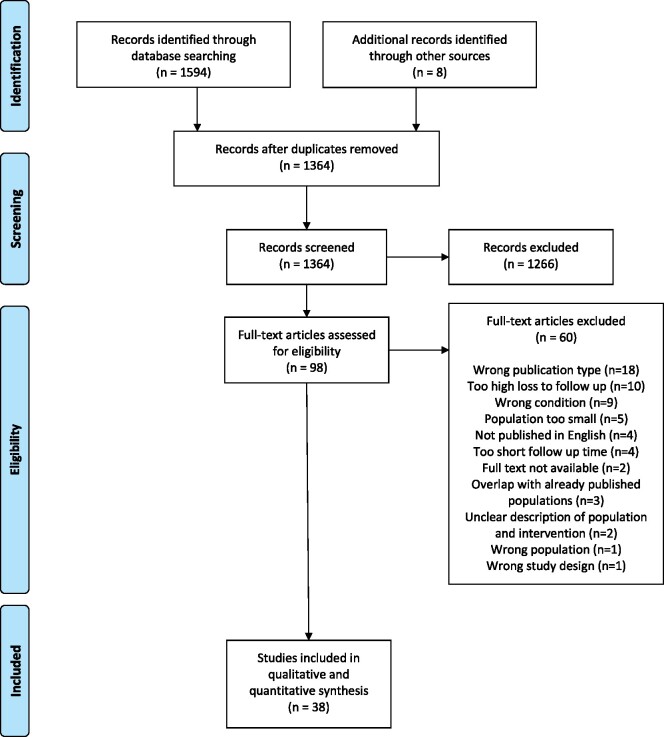

The literature search identified 1364 unique citations; eight additional studies were found through searching of reference lists (Fig. 1). In total, 38 studies were included in the final selection. The characteristics of the final 38 articles are listed in Table I.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram for a systematic review of outcome reporting and outcome measures in studies investigating uterine-sparing treatment for adenomyosis.

Table I.

Study characteristics and types of intervention of the included studies.

| Author, year | Country | Inclusion period | Study design | n, total (n per arm) | Diagnostic tool | Intervention group 1 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention group 2 | ||||||||

| Intervention group 3 | ||||||||

| Kwack et al., 2021 | Korea | May 2011–May 2019 | Cohort, retrospective | 22 | MRI | Adenomyomectomy, antenatal follow-up with strict protocol | ||

| Sun et al., 2021 | China | January 2015–July 2018 | Cohort, not reported if prospective or retrospective | 52 | MRI | Laparoscopic adenomyomectomy + insertion of LNG IUS | ||

| Sun et al., 2020 | China | June 2012–August 2014 | Cohort, not reported if prospective or retrospective | 90 | TVUS + MRI + Ca125 | ‘Major uterine wall resection and reconstruction of the uterus’ (MURU) + LNG-IUS | ||

| Lin et al., 2020 | China | October 2015–October 2017 | Prospective randomized parallel controlled trial | 133 (68/65) | Ultrasound + MRI | Transcutaneous microwave ablation | ||

| Percutaneous radiofrequency ablation | ||||||||

| Li et al., 2020 | China | January 2012–January 2017 | Retrospective open, non-randomized, controlled trial | 193 (57/83/53) | TVUS | Open adenomyomectomy | ||

| Open adenomyomectomy + 6 months GnRH-a | ||||||||

| Open adenomyomectomy + 6 months GnRH-a + LNG IUS | ||||||||

| Huang et al., 2020 | China | January 2012–January 2017 | Retrospective non-randomized controlled trial | 93 (50/43) | TVUS | HIFU + GnRH-a for 4–6 months | ||

| Adenomyomectomy + GnRH-a for 4–6 months | ||||||||

| Yang et al., 2019 | China | August 2015–November 2017 | Cohort prospective | 466 | MRI + TVUS | HIFU + GnRH-a for 3 months + LNG IUS | ||

| Lee et al., 2019 | Korea | February 2010–October 2017 | Cohort retrospective | 889 | MRI + TVUS | HIFU | ||

| Jun-Min et al., 2018 | China | January 2012–December 2014 | Cohort, retrospective | 198 | MRI + TVUS | U-shaped myometrial excavation and modified suture approach | ||

| Li et al., 2018 | China | February 2015–February 2016 | Prospective, nonrandomized, parallel-controlled study |

200 (40/40/40/40/20/20) |

TVUS |

Group 1: 3.75 mg GnRH-a |

Group 2: 1.88 mg GnRH-a |

Group 3: LNG IUS |

|

Group 4: 3.75 mg GnRH-a + LNG IUS |

Group 5: 1.88 mg GnRH-a + LNG IUS |

Group 6: San-Jie-Zhen-Tong capsules |

||||||

| Guo et al., 2018 | China | January 2013–January 2015 | Cohort retrospective | 78 (45/15/18) | MRI + TVUS | HIFU only | ||

| HIFU + LNG IUS | ||||||||

| HIFU + GnRH-a | ||||||||

| Alizzi, 2018 | Iraq | January 2016–January 2018 | Cohort prospective | 32 | TVUS + clinical symptoms | GnRH-a every 28 days until uterine volume <150 cm, then LNG IUS. | ||

| Yang et al., 2017 | China | January 2019–December 2013 | Cohort prospective | 112 (56/56) | TVUS and/or MRI | Laparoscopic uterine artery occlusion and partial adenomyomectomy + laparoscopic uterine pelvic plexus ablation | ||

| Laparoscopic uterine artery occlusion and partial adenomyomectomy only | ||||||||

| Osuga et al., 2017 | Japan | August 2014–June 2015 | Randomized, double-blind, multicentre, placebo-controlled phase III study | 68 (35/33) | TVUS + MRI | Dienogest twice daily for 16 weeks, starting between the second and fifth day of the menstrual cycle, analgetic if needed | ||

| Placebo twice daily for 16 weeks, starting between the second and fifth day of the menstrual cycle, analgetic if needed | ||||||||

| Liu et al., 2017 | China | January 2012–December 2016 | Cohort retrospective | 368 (66/302) | TVUS or MRI | HIFU | ||

| Abdominal hysterectomy | ||||||||

| Huang et al., 2017 | China | January 2011–August 2015 | Cohort retrospective | 102 | MRI | MR-HIFU alone | ||

| MR HIFU + exercise | ||||||||

| Hai et al., 2017 | China | January 2013–October 2015 | Cohort retrospective | 87 | MRI + TVUS + biopsy in some | Ultrasound-guided transcervical radiofrequency ablation | ||

| Park et al., 2016 | Korea | February 2010–December 2014 | Cohort retrospective | 192 | TVUS | HIFU | ||

| Liu et al., 2016 | China | January 2007–December 2013 | Cohort retrospective | 230 | MRI | HIFU | ||

| Chong et al., 2016 | Korea | August 2008–May 2011 | Cohort prospective | 33 | TVUS + MRI | Laparoscopic or robotic adenomyomectomy with uterine artery ligation | ||

| N = 18 (random) GnRH-a additionally | ||||||||

| Long et al. 2015 | China | January 2012–December 2012 | Cohort prospective | 51 | MRI | HIFU | ||

| Lee et al., 2015 | Korea | February 2010–October 2013 | Cohort retrospective | 346 | TVUS + MRI | HIFU | ||

| Huang et al., 2015 | China | March 2011–February 2014 | Cohort prospective (patient chose group) | 94 (48/46) | MRI + TVUS | Adenomyomectomy, conventional + 6 months GnRH-a | ||

| Adenomyomectomy double flap + 6 months GnRH-a | ||||||||

| Zhang et al., 2014 | China | November 2010–June 2012 | RCT | 86 (43/43) | MRI | HIFU + oxytocin injection during HIFU ablation procedure | ||

| HIFU + 0.9% saline injection | ||||||||

| Liu et al., 2014 | China | July 2003–July 2009 | Retrospective cohort | 182 | TVUS | Bilateral laparoscopic uterine artery occlusion + adenomyomectomy | ||

| Ekin et al., 2013 | Turkey | January 2012–December 2012 | Cohort prospective | 70 | TVUS | LNG IUS | ||

| Kelekci et al., 2012 | Turkey | March 2006–May 2009 | Prospective, open, nonrandomized | 74 (23/25/26) | TVUS | LNG IUS (patients with adenomyosis) | ||

| LNG IUS (patients without adenomyosis) | ||||||||

| Copper intrauterine device (patients without adenomyosis) | ||||||||

| Zhou et al., 2011 | China | March 2007–September 2008 | Cohort prospective | 78 | MRI | HIFU | ||

| Ozdegirmenci et al., 2011 | Turkey | April 2007–February 2009 | RCT | 75 (43/32) | TVUS + MRI | LNG IUS | ||

| Abdominal hysterectomy | ||||||||

| Kang et al., 2010 | China | January 2005–June 2007 | Randomized prospective observational | 70 | MRI or TVUS | ‘4-dose regimen’ (triptorelin 3.75 mg by intramuscular injection every 6 weeks for a total of 4 doses) | ||

| Conventional regimen (1 injection every 4 weeks for a total of 6 doses). | ||||||||

| Sheng et al., 2009 | China | NR | Prospective cohort | 94 | TVUS | LNG IUS | ||

| Kang et al., 2009 | China | July 2003–October 2005 | Retrospective cohort study | 37 | TVUS + clinical symptoms | Laparoscopic adenomyosis resection + uterine artery occlusion | ||

| Cho et al., 2008 | Korea | July 2003–March 2007 | Cohort prospective | 47 | TVUS | LNG IUS | ||

| Kim et al., 2007 | Korea | 1998–2000 | Cohort prospective | 54 | MRI | Uterine artery embolization | ||

| Bragheto et al., 2007 | Brazil | NR | Cohort prospective | 29 | MRI | LNG IUS | ||

| Hadisaputra and Anggraeni, 2006 | Indonesia | June 2003–June 2004 | Randomized controlled trial | 20 (10/10) | TVUS | Laparoscopic resection + GnRH-a for 3 months | ||

| Laparoscopic myolysis + GnRH-a for 3 months | ||||||||

| Maia et al., 2003 | Brazil | NR | Cohort retrospective | 95 (53/42) | TVUS | Transcervical endometrial resection + LNG IUS | ||

| Transcervical endometrial resection | ||||||||

| Fedele et al., 1997 | Italy | NR | Cohort prospective | 25 | TVUS or MRI | LNG IUS | ||

GnRH-a, gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogue; HIFU, high-intensity focused ultrasound; LNG IUS, levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system; TVUS, transvaginal ultrasound.

Study characteristics

We included 38 trials, reporting on data from 5175 women (Table I) (Fedele et al., 1997; Maia et al., 2003; Hadisaputra and Anggraeni, 2006; Bragheto et al., 2007; Kim et al., 2007; Cho et al., 2008; Kang et al., 2009; Sheng et al., 2009; Kang et al., 2010; Ozdegirmenci et al., 2011; Zhou et al., 2011; Kelekci et al., 2012; Ekin et al., 2013; Liu et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2014; Huang et al., 2015; Lee et al., 2015, 2019; Long et al., 2015; Chong et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2016; Park et al., 2016; Hai et al., 2017; Huang et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2017; Osuga et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2017, 2019; Alizzi, 2018; Guo et al., 2018; Jun-Min et al., 2018; Li et al., 2018, 2020; Huang et al., 2020; Lin et al., 2020; Sun et al., 2020; Kwack et al., 2021; Sun et al., 2021). There were six (16%) randomized controlled trials (RCTs) (Hadisaputra and Anggraeni, 2006; Kang et al., 2010; Ozdegirmenci et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2014; Osuga et al., 2017; Lin et al., 2020); 13 studies (34%) were prospective, non-randomized trials, of which nine had cohorts with a single arm (Fedele et al., 1997; Bragheto et al., 2007; Kim et al., 2007; Cho et al., 2008; Sheng et al., 2009; Zhou et al., 2011; Ekin et al., 2013; Alizzi, 2018; Yang et al., 2019) and four studies had two or more arms (Kelekci et al., 2012; Huang et al., 2015; Yang et al., 2017; Li et al., 2018). There were 17 (45%) retrospective cohort studies, 12 with a single arm (Kang et al., 2009; Liu et al., 2014, 2016; Lee et al., 2015, 2019; Long et al., 2015; Chong et al., 2016; Park et al., 2016; Hai et al., 2017; Huang et al., 2017; Jun-Min et al., 2018; Kwack et al., 2021) and five with two or more arms (Maia et al., 2003; Liu et al., 2017; Guo et al., 2018; Huang et al., 2020; Li et al., 2020). Two studies with a single cohort did not specify if the cohort was retrospective or prospective (Sun et al., 2020, 2021).

Only five studies had a low risk of bias (Ozdegirmenci et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2014; Osuga et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2017; Lin et al., 2020) with all the other studies having an unclear or high risk of bias in at least one domain (Supplementary Data S2). Common concerns in terms of risk of bias were the retrospective nature of the studies, unclear representativeness of participants, the lack of control groups, and lack of randomization.

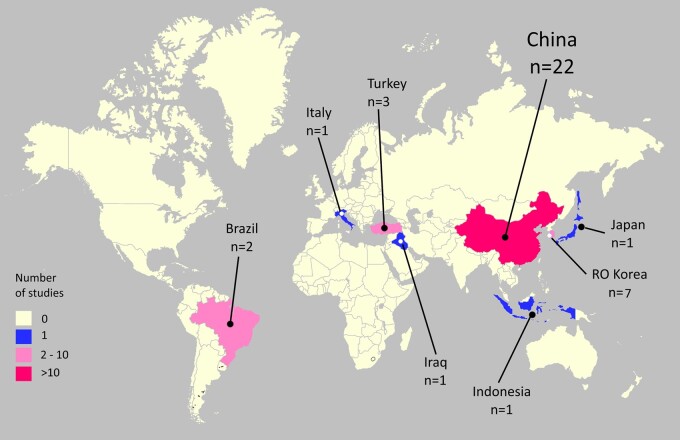

The majority of the 38 studies (84%) were conducted in Asia, of which 22 (58%) were from China (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

World map with an overview over the countries of origin for the included studies.

Ten different interventions, alone or in combination, were described in at least one arm (Table I).

Outcomes

We identified 203 outcomes in 29 domains, including 41 complications or adverse outcomes (Table II and Supplementary Data S3). Table III shows which studies measured the most frequent outcomes.

Table II.

Number of outcomes reported, classified by core area and outcome domain.

|

Core area Outcome domain |

Number of outcomes in this domain/of those harms |

|---|---|

| Physiological/clinical | |

| Blood and lymphatic system outcomes | 5/0 |

| Cardiac outcomes | 2/2 |

| Endocrine outcomes | 7/4 |

| Gastrointestinal outcomes | 4/4 |

| General outcomes | 12/3 |

| Infection and infestation outcomes | 2/2 |

| Injury and poisoning outcomes | 1/1 |

| Musculoskeletal and connective tissue outcomes | 2/2 |

| Outcomes relating to neoplasms: benign, malignant and unspecified (including cysts and polyps) | 1/1 |

| Nervous system outcomes | 4/4 |

| Pregnancy, puerperium and perinatal outcomes | 17/0 |

| Renal and urinary outcomes | 12/4 |

| Reproductive system and breast outcomes | 28/2 |

| Psychiatric outcomes | 4/2 |

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue outcomes | 2/2 |

| Vascular outcomes | 3/2 |

| Life impact | |

| Physical functioning | 24/0 |

| Social functioning | 5/0 |

| Role functioning | 6/0 |

| Emotional functioning/wellbeing | 32/0 |

| Cognitive functioning | 2/0 |

| Global quality of life | 1/0 |

| Perceived health status | 5/0 |

| Delivery of care | 15/2 |

| Personal circumstances | 4/0 |

| Resource use | |

| Economic | 2/1 |

| Hospital | 1/0 |

| Need for further intervention | 2/2 |

| Adverse events | |

| Adverse events/effects | 1/1 |

| Total * | 203/41 |

Outcomes could be classified in several domains but are counted once in the total. All individual outcomes are reported in Supplementary Data S3.

Table III.

Outcome reporting and outcome quality scores in adenomyosis trials.

|

First author,

year of publication |

Dysmenor rhoea | Menstrual blood volume | Uterine volume | Lesion volume | Quality of life | Sexual (dys) function | Urinary symptoms | Pelvic pain | Adverse outcomes with classification | Adverse outcomes, unstructured | Pregnancy outcomes | Outcome quality score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kwack et al., 2021 | x | x | 3 | |||||||||

| Sun et al., 2021 | x | x | x | x | 4 | |||||||

| Sun et al., 2020 | x | x | x | x | 3 | |||||||

| Lin et al., 2020 | x | x | x | x | x | 4 | ||||||

| Li et al., 2020 | x | x | x | x | 5 | |||||||

| Huang et al., 2020 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | 4 | |||

| Yang et al., 2019 | x | x | x | 4 | ||||||||

| Lee et al., 2019 | x | x | x | x | x | x | 3 | |||||

| Jun-Min et al., 2018 | x | x | x | x | x | 2 | ||||||

| Li et al., 2018 | x | x | x | x | 2 | |||||||

| Guo et al., 2018 | x | x | x | x | x | x | 2 | |||||

| Alizzi, 2018 | x | x | x | x | 2 | |||||||

| Yang et al., 2017 | x | x | x | x | x | 4 | ||||||

| Osuga et al., 2017 | x | x | x | x | x | 6 | ||||||

| Liu et al., 2017 | x | x | x | x | x | x | 0 | |||||

| Huang et al., 2017 | x | x | 2 | |||||||||

| Hai et al., 2017 | x | x | x | x | x | x | 2 | |||||

| Park et al., 2016 | x | x | 1 | |||||||||

| Liu et al., 2016 | x | x | 2 | |||||||||

| Chong et al., 2016 | x | x | x | x | 3 | |||||||

| Long et al. 2015 | x | x | x | x | x | x | 3 | |||||

| Lee et al., 2015 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | 3 | ||||

| Huang et al., 2015 | x | x | x | x | x | 3 | ||||||

| Zhang et al., 2014 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | 3 | ||||

| Liu et al., 2014 | x | x | x | x | x | x | 5 | |||||

| Ekin et al., 2013 | x | x | x | x | 4 | |||||||

| Kelekci et al., 2012 | x | x | x | 6 | ||||||||

| Zhou et al., 2011 | x | x | x | 6 | ||||||||

| Ozdegirmenci et al., 2011 | x | x | x | x | 6 | |||||||

| Kang et al., 2010 | x | x | x | 4 | ||||||||

| Sheng et al., 2009 | x | x | x | x | 6 | |||||||

| Kang et al., 2009 | x | x | x | x | 2 | |||||||

| Cho et al., 2008 | x | x | x | x | 4 | |||||||

| Kim et al., 2007 | x | x | x | x | 5 | |||||||

| Bragheto et al., 2007 | x | x | x | x | 5 | |||||||

| Hadisaputra and Anggraeni, 2006 | x | x | x | x | 3 | |||||||

| Maia et al., 2003 | x | x | 1 | |||||||||

| Fedele et al., 1997 | x | x | x | 6 | ||||||||

| Reported by, n (%) |

31 (82) |

30 (79) |

27 (71) |

9 (24) |

9 (24) |

8 (21) |

9 (24) |

2 (5) |

8 (21) |

24 (63) |

7 (18) |

The mean quality score for the outcomes was 3.5 ± 0.51, with scores of 2, 3 and 4 being equally frequent and accounting for 66% of the studies (Table III). The association between the age of the publication and its quality score was not statistically significantly (P = 0.08).

Only seven (18%) studies had a clearly defined primary outcome (Fedele et al., 1997; Maia et al., 2003; Sheng et al., 2009; Chong et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2017; Osuga et al., 2017; Sun et al., 2021) and 11 (29%) studies stated multiple or all reported outcomes to be the primary (Hadisaputra and Anggraeni, 2006; Bragheto et al., 2007; Kang et al., 2010; Ozdegirmenci et al., 2011; Zhou et al., 2011; Kelekci et al., 2012; Ekin et al., 2013; Liu et al., 2014; Long et al., 2015; Li et al., 2018; Huang et al., 2020). Twenty studies (53%) did not define a primary outcome at all (Kim et al., 2007; Cho et al., 2008; Kang et al., 2009, 2010; Zhang et al., 2014; Huang et al., 2015; Lee et al., 2015, 2019; Liu et al., 2016; Park et al., 2016; Hai et al., 2017; Huang et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2017, 2019; Alizzi, 2018; Guo et al., 2018; Jun-Min et al., 2018; Li et al., 2018; Lin et al., 2020; Sun et al., 2020; Kwack et al., 2021). Most of these studies described the aims in non-specific terms, such as ‘clinical efficiency’, but without defining the terms ‘clinical’ or ‘efficiency’. Most studies did not provide a justification for the chosen outcomes.

Only three (8%) of the studies provided a sample size calculation based on an outcome (Liu et al., 2014; Osuga et al., 2017; Ozdegirmenci et al., 2011), and none of the other 35 studies provided a posthoc estimation of statistical power.

Outcome reporting and outcome measures

The majority of the studies provided an outcome measure for the main outcomes. The most common time points for measuring outcomes were at 3, 6 and 12 months after the intervention, as described in 14 studies (Fedele et al., 1997; Kang et al., 2009; Sheng et al., 2009; Huang et al., 2015; Lee et al., 2015, 2019; Long et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2016; Li et al., 2018; Yang et al., 2019; Lin et al., 2020; Sun et al., 2020). However, only 19 studies reported on all their outcomes at all the predetermined time points according to the described methods. Several studies provided only a visual or summarized outcome reporting for at least one of the outcomes, without values, SD or 95% CI (Maia et al., 2003; Bragheto et al., 2007; Ozdegirmenci et al., 2011; Ekin et al., 2013; Alizzi, 2018).

The various outcome measures and interpretation of the most common outcomes, namely dysmenorrhoea, menstrual volume/menorrhagia and QOL, are presented in Supplementary Data S4. There were 14 different measuring tools and interpretations for dysmenorrhoea, and 17 for menstrual blood loss (Supplementary Data S4). Only a minority of the studies reported how outcome measurement was performed, for example if the patients were instructed to use the Pictorial Blood Loss Assessment Chart (PBLAC), or if questionnaires were filled out by the patient or by the doctor, for example by telephone interview.

Uterine volume was reported as an outcome in 27 (71%) studies (Table III). In most cases, the volume was measured using transvaginal ultrasound. Only three studies reported if the measurement included the cervix and how uterine length was measured. None of the papers provided a clinical justification for this outcome.

Eight (21%) studies followed a classification when registering and reporting adverse events (Zhou et al., 2011; Liu et al., 2016; Hai et al., 2017; Li et al., 2018; Lin et al., 2020), while the others did not report how complications or side effects were registered or reported.

Discussion

In this review, we identified substantial heterogeneity in outcome reporting in studies evaluating interventions for the treatment of adenomyosis-associated symptoms. Only six studies that met the inclusion criteria were RCTs. A small proportion of studies provided a clear primary outcome, or a sample size/power calculation and incomplete outcome reporting was common.

The most frequently reported outcome was dysmenorrhoea, which was reported in 31 (82%) of studies. There were 14 different outcome measures used to assess dysmenorrhoea, with different visual analogue scales being the most frequently used. Most researchers attempted to use validated measuring tools for the main outcomes.

Interpretation

Outcomes identified through this systematic review of published studies reflect outcomes that healthcare professionals or researchers have chosen to select, collect and report. These outcomes are largely focused on menstrual symptoms and uterine volume with only a minority of studies reporting outcomes relating to fertility or QOL.

Dyspareunia, chronic pelvic pain and other pain-related outcomes were measured in very few studies. A review of outcome reporting in endometriosis, a condition which has significant overlap of both patient population and associated symptoms with adenomyosis, reported eight different pain-related outcomes (Hirsch et al., 2016). This difference may be explained by the wider variation in pain symptoms that women with endometriosis may experience.

Patient-centredness is defined by ‘health care which takes into account the preferences and aspirations of individual service users’ and is one of the dimensions of quality of care (World Health Organization, 2006). Focus on outcomes such as satisfaction with the treatment or health-related QOL in clinical studies reflect patient-centredness. These outcomes are important for patients to make informed decisions about different treatment options. However, those type of outcomes were reported infrequently.

Patient-centredness is also reflected in outcomes being important to women, and we assume that dysmenorrhoea and heavy menstrual bleeding are amongst those. These were frequently reported. A challenge is, however, that many of those outcomes are by nature patient-reported and can be difficult to measure and replicate (Magnay et al., 2020). In addition, there is no disease-specific QOL measurement for adenomyosis, which makes the QOL results reported by other tools less reliable for this group of women.

In contrast, imaging outcomes, such as the uterine size, were reported in the majority of the studies. It remains unclear whether this surrogate marker of disease severity is associated with clinical symptoms in women with adenomyosis. This suggests that uterine volume may be an outcome of convenience rather than clinical significance. Similarly, serum levels of CA-125 were commonly reported without a clear clinical justification. The use of these outcomes suggests a lack of patient involvement and input in adenomyosis research.

Reporting fertility and pregnancy outcomes is highly relevant for adenomyosis trials, as many women with adenomyosis find it difficult to fall pregnant. Unfortunately, those outcomes are only reported sporadically. Seemingly random reporting on pregnancies or live birth, as well as leaving it unclear how many women in a study sample tried to get pregnant, possibly augments the effect of certain interventions on fertility outcomes.

The lack of well-designed randomized trials in adenomyosis exacerbates the difficulty in determining which treatments are more effective and better to use.

Outcome reporting variation seen in this study prohibits the combination, comparison, and synthesis of research data into meta-analysis. This limits the ability of research to inform clinical care guidelines and progress the specialty. This variation in outcome reporting may reflect selective outcome reporting and outcome reporting bias. This has been identified to be a major limitation in Cochrane systematic reviews. Following adjustment for outcome reporting bias, 19% of all their reviews would no longer have statistically significant treatment effects while 26% of their reviews would have over-estimated the treatment effects by 20% (Chalmers and Glasziou, 2009). This represents a large area of potentially avoidable research waste. Three key areas of avoidable research waste are related to outcome reporting. These include: important outcomes are not assessed; research studies fail to consider outcomes in the context of previously published research; and over half of all outcomes collected are never reported in the final publication (Chalmers and Glasziou, 2009).

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of this study include its originality, and the robust search strategy and design. The review process was performed by two independent researchers, to prevent bias. This is the first systematic review to describe outcome reporting variation in adenomyosis studies.

This review is not without limitations. We included studies written in English only. Four studies published in Chinese had to be left out, but no further papers were excluded for language reasons. We included studies of differing methodological design, limiting the ability to compare and contrast the study quality.

Most studies were retrospective and had a high risk of bias, which could have influenced the quality and type of reported outcomes. We considered limiting the inclusion criteria to high quality RCTs or prospective observational studies, however this would have limited the number of outcomes and not accurately reflected current outcome reporting.

Recommendations

This review highlights the importance of the recent initiatives to enhance research methodology including the CONSORT statement, the AllTrials initiative and the CROWN initiative. These initiatives aim to ensure that all prospectively registered RCTs are published regardless of their findings, eliminating publication bias from studies that are withheld where there is negative or no effect demonstrated (Song et al., 2010). The development and use of a collection of widely agreed and well-defined outcomes, termed a COS, would help to address selective outcome reporting bias and facilitate the production of comparable data for improved evidence-based patient care. This progressive approach to standardize research methodology is supported by national and international stakeholders. The World Health Organization, the National Institutes of Health and the Cochrane Collaboration are committed to supporting, developing and implementing COSs.

There is a clear and evident need for the development of a COS together with recommendations for uniform outcome measures in adenomyosis research and it is important that people with adenomyosis participate in this process.

This systematic review is the first step in the development of a minimum data set to be selected, collected, and reported in all future clinical trials on adenomyosis. It will be developed by the COSAR initiative with reference to methods described by the COMET initiative (Williamson et al., 2017). The development of a COS for therapeutic interventional studies in adenomyosis research will enhance the quality of adenomyosis research facilitating a more patient-centred approach to care.

Data availability

The data underlying this article are available in the article and in its online supplementary material.

Authors’ roles

Conception of work, study design: T.T., M.O., J.N., M.H., D.J.; Literature search, quality assessment, data extraction: T.T., M.O.; Interpretation of results, drafting of manuscript and approval of final version: T.T., M.O., J.N., M.H., D.J.

Funding

T.T. receives a grant (2020083) from the South Eastern Norwegian Health Authority, which had no influence on study design, data extraction, analysis or interpretation.

Conflict of interest

T.T. receives fees from General Electrics for lectures on ultrasound independently of this project.

Supplementary Material

References

- Abbas AM, Samy A, Atwa K, Ghoneim HM, Lotfy M, Saber Mohammed H, Abdellah AM, El Bahie AM, Aboelroose AA, El Gedawy AM. et al. The role of levonorgestrel intra-uterine system in the management of adenomyosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2020;99:571–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abbott J.Surgical treatment is an excellent option for women with endometriosis and infertility. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2017;57:679–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alizzi FJ.The clinical efficacy of sequential use of gonadotropin-releasing hormone analog-levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system in medically ill women with symptomatic and relatively large adenomyosis. Asian J Pharm Clin Res 2018;11:144–148. [Google Scholar]

- Bragheto AM, Caserta N, Bahamondes L, Petta CA.. Effectiveness of the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system in the treatment of adenomyosis diagnosed and monitored by magnetic resonance imaging. Contraception 2007;76:195–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalmers I, Glasziou P.. Avoidable waste in the production and reporting of research evidence. Lancet 2009;374:86–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho S, Nam A, Kim H, Chay D, Park K, Cho DJ, Park Y, Lee B.. Clinical effects of the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device in patients with adenomyosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2008;198:373.e1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chong GO, Lee YH, Hong DG, Cho YL, Lee YS.. Long-term efficacy of laparoscopic or robotic adenomyomectomy with or without medical treatment for severely symptomatic adenomyosis. Gynecol Obstet Invest 2016;81:346–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Bruijn AM, Smink M, Lohle PNM, Huirne JAF, Twisk JWR, Wong C, Schoonmade L, Hehenkamp WJK.. Uterine artery embolization for the treatment of adenomyosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2017;28:1629–1642.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodd S, Clarke M, Becker L, Mavergames C, Fish R, Williamson PR.. A taxonomy has been developed for outcomes in medical research to help improve knowledge discovery. J Clin Epidemiol 2018;96:84–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dueholm M.Uterine adenomyosis and infertility, review of reproductive outcome after in vitro fertilization and surgery. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2017;96:715–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy J, Bhattacharya S, Herman M, Mol B, Vail A, Wilkinson J, Farquhar C.. Reducing research waste in benign gynaecology and fertility research. BJOG 2017;124:366–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy J, Hirsch M, Vercoe M, Abbott J, Barker C, Collura B, Drake R, Evers J, Hickey M, Horne AW. et al. A core outcome set for future endometriosis research: an international consensus development study. BJOG 2020;127:967–974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy JMN, Bhattacharya S, Bhattacharya S, Bofill M, Collura B, Curtis C, Evers JLH, Giudice LC, Farquharson RG, Franik S. et al. Standardizing definitions and reporting guidelines for the infertility core outcome set: an international consensus development study. Fertil Steril 2021;115:201–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekin M, Cengiz H, Ayağ ME, Kaya C, Yasar L, Savan K.. Effects of the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system on urinary symptoms in patients with adenomyosis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2013;170:517–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedele L, Bianchi S, Raffaelli R, Portuese A, Dorta M.. Treatment of adenomyosis-associated menorrhagia with a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device. Fertil Steril 1997;68:426–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Q, Xu F, Ding Z, Li P, Wang X, Gao B.. High intensity focused ultrasound treatment of adenomyosis: a comparative study. Int J Hyperthermia 2018;35:505–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadisaputra W, Anggraeni TD.. Laparoscopic resection versus myolysis in the management of symptomatic uterine adenomyosis: alternatives to conventional treatment. Med J Indonesia 2006;15:9–17. [Google Scholar]

- Hai N, Hou Q, Ding X, Dong X, Jin M.. Ultrasound-guided transcervical radiofrequency ablation for symptomatic uterine adenomyosis. Br J Radiol 2017;90:20160119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harada T, Taniguchi F, Amano H, Kurozawa Y, Ideno Y, Hayashi K, Harada T.. Adverse obstetrical outcomes for women with endometriosis and adenomyosis: a large cohort of the Japan Environment and Children's Study. PLoS One 2019;14:e0220256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harman NL, Bruce IA, Callery P, Tierney S, Sharif MO, O'Brien K, Williamson PR.. MOMENT–management of otitis media with effusion in cleft palate: protocol for a systematic review of the literature and identification of a core outcome set using a Delphi survey. Trials 2013;14:70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch M, Duffy JMN, Kusznir JO, Davis CJ, Plana MN, Khan KS.. Variation in outcome reporting in endometriosis trials: a systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2016;214:452–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton J, Sterrenburg M, Lane S, Maheshwari A, Li TC, Cheong Y.. Reproductive, obstetric, and perinatal outcomes of women with adenomyosis and endometriosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update 2019;25:592–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X, Huang Q, Chen S, Zhang J, Lin K, Zhang X.. Efficacy of laparoscopic adenomyomectomy using double-flap method for diffuse uterine adenomyosis. BMC Womens Health 2015;15:24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X, Yu D, Zou M, Wang L, Xing HR, Wang Z.. The effect of exercise on high-intensity focused ultrasound treatment efficacy in uterine fibroids and adenomyosis: a retrospective study. BJOG 2017;124(Suppl 3):46–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang YF, Deng J, Wei XL, Sun X, Xue M, Zhu XG, Deng XL.. A comparison of reproductive outcomes of patients with adenomyosis and infertility treated with high-intensity focused ultrasound and laparoscopic excision. Int J Hyperthermia 2020;37:301–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jun-Min X, Kun-Peng Z, Yin-Kai Z, Ya-Qin Z, Xiao-Fan F, Xiao-Yu Z, Li W, Bin W.. A new surgical method of U-shaped myometrial excavation and modified suture approach with uterus preservation for diffuse adenomyosis. Biomed Res Int 2018;2018:1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang J-L, Wang X-X, Nie M-L, Huang X-h.. Efficacy of gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist and an extended-interval dosing regimen in the treatment of patients with adenomyosis and endometriosis. Gynecol Obstet Invest 2010;69:73–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang L, Gong J, Cheng Z, Dai H, Liping H.. Clinical application and midterm results of laparoscopic partial resection of symptomatic adenomyosis combined with uterine artery occlusion. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2009;16:169–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelekci S, Kelekci KH, Yilmaz B.. Effects of levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system and T380A intrauterine copper device on dysmenorrhea, duration and amount of menstrual bleeding in women with and without adenomyosis. J Endometr 2012;4:152–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy CE, Fonner VA, Armstrong KA, Denison JA, Yeh PT, O'Reilly KR, Sweat MD.. The Evidence Project risk of bias tool: assessing study rigor for both randomized and non-randomized intervention studies. Syst Rev 2019;8:3–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan K.The CROWN Initiative: journal editors invite researchers to develop core outcomes in women's health. BJOG 2016;123(Suppl 3):103–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim MD, Kim S, Kim NK, Lee MH, Ahn EH, Kim HJ, Cho JH, Cha SH.. Long-term results of uterine artery embolization for symptomatic adenomyosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2007;188:176–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwack JY, Lee SJ, Kwon YS.. Pregnancy and delivery outcomes in the women who have received adenomyomectomy: performed by a single surgeon by a uniform surgical technique. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol 2021;60:99–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J-S, Hong G-Y, Lee K-H, Song J-H, Kim T-E.. Safety and efficacy of ultrasound-guided high-intensity focused ultrasound treatment for uterine fibroids and adenomyosis. Ultrasound Med Biol 2019;45:3214–3221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J-S, Hong G-Y, Park B-J, Kim T-E.. Ultrasound-guided high-intensity focused ultrasound treatment for uterine fibroid & adenomyosis: a single center experience from the Republic of Korea. Ultrason Sonochem 2015;27:682–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Ding Y, Zhang X-Y, Feng W-W, Hua K-Q.. Drug therapy for adenomyosis: a prospective, nonrandomized, parallel-controlled study. J Int Med Res 2018;46:1855–1865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Yuan M, Li N, Zhen Q, Chen C, Wang G.. The efficacy of medical treatment for adenomyosis after adenomyomectomy. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 2020;46:2092–2099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, Clarke M, Devereaux PJ, Kleijnen J, Moher D.. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ 2009;339:b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin XL, Hai N, Zhang J, Han ZY, Yu J, Liu FY, Dong XJ, Liang P.. Comparison between microwave ablation and radiofrequency ablation for treating symptomatic uterine adenomyosis. Int J Hyperthermia 2020;37:151–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu M, Cheng Z, Dai H, Qu X, Kang L.. Long-term efficacy and quality of life associated with laparoscopic bilateral uterine artery occlusion plus partial resection of symptomatic adenomyosis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2014;176:20–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Wang W, Wang Y, Wang Y, Li Q, Tang J.. Clinical predictors of long-term success in ultrasound-guided high-intensity focused ultrasound ablation treatment for adenomyosis: a retrospective study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95:e2443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu XF, Huang LH, Zhang C, Huang GH, Yan LM, He J.. A comparison of the cost-utility of ultrasound-guided high-intensity focused ultrasound and hysterectomy for adenomyosis: a retrospective study. BJOG 2017;124: 40–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long L, Chen J, Xiong Y, Zou M, Deng Y, Chen L, Wang Z.. Efficacy of high-intensity focused ultrasound ablation for adenomyosis therapy and sexual life quality. Int J Clin Exp Med 2015;8:11701–11707. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnay JL, O'Brien S, Gerlinger C, Seitz C.. Pictorial methods to assess heavy menstrual bleeding in research and clinical practice: a systematic literature review. BMC Womens Health 2020;20:24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maia HJ, Maltez A, Coelho G, Athayde C, Coutinho EM.. Insertion of mirena after endometrial resection in patients with adenomyosis. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc 2003;10:512–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osuga Y, Fujimoto-Okabe H, Hagino A.. Evaluation of the efficacy and safety of dienogest in the treatment of painful symptoms in patients with adenomyosis: a randomized, double-blind, multicenter, placebo-controlled study. Fertil Steril 2017;108:673–678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osuga Y, Watanabe M, Hagino A.. Long-term use of dienogest in the treatment of painful symptoms in adenomyosis. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 2017;43:1441–1448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A.. Rayyan-a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev 2016;5:210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozdegirmenci O, Kayikcioglu F, Akgul MA, Kaplan M, Karcaaltincaba M, Haberal A, Akyol M.. Comparison of levonorgestrel intrauterine system versus hysterectomy on efficacy and quality of life in patients with adenomyosis. Fertil Steril 2011;95:497–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J, Lee JS, Cho J-H, Kim S.. Effects of high-intensity-focused ultrasound treatment on benign uterine tumor. J Korean Med Sci 2016;31:1279–1283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pergialiotis V, Durnea C, Elfituri A, Duffy J, Doumouchtsis SK.. Do we need a core outcome set for childbirth perineal trauma research? A systematic review of outcome reporting in randomised trials evaluating the management of childbirth trauma. BJOG 2018;125:1522–1531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng J, Zhang WY, Zhang JP, Lu D.. The LNG-IUS study on adenomyosis: a 3-year follow-up study on the efficacy and side effects of the use of levonorgestrel intrauterine system for the treatment of dysmenorrhea associated with adenomyosis. Contraception 2009;79:189–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song F, Parekh S, Hooper L, Loke YK, Ryder J, Sutton AJ, Hing C, Kwok CS, Pang C, Harvey I.. Dissemination and publication of research findings: an updated review of related biases. Health Technol Assess 2010;14:iii, ix. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun C, Ren XY, Gao Y, Liang ZG, Mou M, Gu HF, Xiao YB.. Clinical efficacy and safety of major uterine wall resection and reconstruction of the uterus combined with LNG-IUS for the treatment of severe adenomyosis. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd 2020;80:300–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun F, Zhang Y, You M, Yang Y, Yu Y, Xu H.. Laparoscopic adenomyomectomy combined with levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system in the treatment of adenomyosis: feasibility and effectiveness. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 2021;47:613–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Upson K, Missmer SA.. Epidemiology of adenomyosis. Semin Reprod Med 2020;38:89–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson PR, Altman DG, Bagley H, Barnes KL, Blazeby JM, Brookes ST, Clarke M, Gargon E, Gorst S, Harman N. et al. The COMET Handbook: version 1.0. Trials 2017;18:280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Quality of Care: A Process for Making Strategic Choices in Health Systems. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Yang W, Liu M, Liu L, Jiang C, Chen L, Qu X, Cheng Z.. Uterine-sparing laparoscopic pelvic plexus ablation, uterine artery occlusion, and partial adenomyomectomy for adenomyosis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2017;24:940–945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X, Zhang X, Lin B, Feng X, Aili A.. Combined therapeutic effects of HIFU, GnRH-a and LNG-IUS for the treatment of severe adenomyosis. Int J Hyperthermia 2019;36:486–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Zou M, Zhang C, He J, Mao S, Wu Q, He M, Wang J, Zhang R, Zhang L.. Effects of oxytocin on high intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) ablation of adenomysis: a prospective study. Eur J Radiol 2014;83:1607–1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou M, Chen J-Y, Tang L-D, Chen W-Z, Wang Z-B.. Ultrasound-guided high-intensity focused ultrasound ablation for adenomyosis: the clinical experience of a single center. Fertil Steril 2011;95:900–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article are available in the article and in its online supplementary material.