Abstract

Background and Objectives: The Internet is widely used and disseminated amongst youngsters and many web-based applications may serve to improve mental health care access, particularly in remote and distant sites or in settings where there is a shortage of mental health practitioners. However, in recent years, specific digital psychiatry interventions have been developed and implemented for special populations such as children and adolescents. Materials and Methods: Hereby, we describe the current state-of-the-art in the field of TMH application for young mental health, focusing on recent studies concerning anxiety, obsessive-compulsive disorder and affective disorders. Results: After screening and selection process, a total of 56 studies focusing on TMH applied to youth depression (n = 29), to only youth anxiety (n = 12) or mixed youth anxiety/depression (n = 7) and youth OCD (n = 8) were selected and retrieved. Conclusions: Telemental Health (TMH; i.e., the use of telecommunications and information technology to provide access to mental health assessment, diagnosis, intervention, consultation, supervision across distance) may offer an effective and efficacious tool to overcome many of the barriers encountering in the delivery of young mental health care.

Keywords: adolescents, adolescence, affective disorders, anxiety, obsessive-compulsive disorder, TeleMental Health, telepsychiatry, youngsters, youth, youth mental health

1. Introduction

The dissemination of interconnected networks, the growth and spread of new communication and information technologies (IT) and the capillary digitalization across all ages at different levels, have rapidly led to an increasing usage of the Internet and online tools worldwide [1], being smartphones and other online devices used nowadays as primary means of source of information and as preferred mode for social communication and peer interaction, particularly among ‘digital native’ young people [1,2]. Young people born after 1993 (i.e., when the Internet became widely available) have been referred to as ‘digital natives’ as they fundamentally grew up with the Internet and within the digital revolution [3,4]. A systematic review evaluating the effectiveness of online services in facilitating mental health seeking care in young people aged 14–25 years, reported in 38.4% of the sample a preference in online seeking mental health information [5]. Overall, the current digitalization may effectively facilitate the delivery and increase the access to mental health care among youngsters, particularly due to the current COVID-19 pandemic [6,7,8]. Within this context, Telemental Health (TMH) was born mainly due to an increased need in offering an equity access to mental health care to those people living in rural and remote areas, reducing the logistic and financial barriers encountering by people seeking help for a mental health condition and to overcome the lack of local specialty professionals in specific mental health areas such as Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (CAP) and CAP subspecialties (i.e., Autism Spectrum Disorders, Attention-Deficit-Hyperactivity Disorders, etc.) [7,9]. Several studies reported that TMH interventions may deliver and substitute any in-person mental health care [10,11,12,13,14,15]. Moreover, mobile health (mHealth), e-Mental Health and social media have been also demonstrated to be effectively used to access and treat patients at all ages, including adolescents, their parents and families [9,15,16].

Within the context of Youth Mental Health, TMH interventions have been successfully used to provide mental health services to children, adolescents and their parents, by offering several delivering modalities (i.e., audio call or audio plus video call) and typologies of interventions (i.e., telepsychiatry, telepsychotherapy, psychoeducation, etc.) [8,9,17,18] (Table 1). TMH held the promise to reach a larger population of youngsters that relies on paediatric or primary care, school, and juvenile correctional populations for their mental health assessment and treatment [8,17]. Overall, the youngsters usually display a greater comfort and satisfaction in receiving a treatment through technology compared to earlier generations, including their parents [5,17,19,20,21].

Table 1.

Psychiatric services delivered by TeleMental Health.

| Psychiatric Evaluation |

|

| Psychiatric Crisis service |

|

| Initial Outpatient Visit |

|

| Established Outpatient Visit |

|

| Teletherapy |

|

1.1. TeleMental Health

TMH comprise the use of real-time and interactive synchronous videoconferencing (VC), including telepsychiatry and telepsychotherapy, synchronous audioconferencing (i.e., audio call) as well as asynchronous technology modalities, including e-mails, text-based mobile health interventions, chatbots, e-consultations, and standalone remote devices [7,18,22,23,24,25]. TMH may include the process of mental health assessment, diagnosis, online-based interventions, consultations, supervision, and information across distance [10,12,13,25].

1.2. Telepsychiatry and/or Telepsychotherapy via Audio and/or Video Calls

In 1973, the term ‘telepsychiatry’ was first used to describe consultation services provided from the Massachusetts General Hospital to a medical site in Boston’s Logan International Airport and the Bedford Veteran’s Administration [26]. Telepsychiatry consists of a synchronous (i.e., 2-way) VC service rendered via a real-time interactive audio and video telecommunication system, used to provide a psychiatric evaluation, consultation, supervision, education and treatment [25]. The real-time interaction is provided between a psychiatrist and a patient who is located at a distant site from the physician or other qualified health care professional. Telepsychiatry requires little adaptation to provide care comparable to usual in-person care, being flexible and being a reasonable alternative to office visits for patients who cannot readily access needed care [7,25]. TMH may be as well delivered only by using telephony (i.e., voice/audio calls). Voice phone calls represent the oldest form of TMH and has been used in the treatment and management of several psychiatric conditions, including anxiety disorders, suicidal ideation and depression [18,19,27].

1.3. Asynchronous Technology Modes

Apart from the conventional, real-time, interactive, bi-directional and audio-video communication, other technology modes are becoming the mainstream in mental health care, including those ‘asynchronous modalities’ such as mobile technology which are integrated in phones, wearable devices and sensors, e-mails, text-based mobile health interventions, chatbots, e-consultations, and standalone remote devices [13]. e-Mail interviewing with youngsters represents a cost-effective and flexible modality able to provide to clinicians a written transcript for analysis, allowing clinicians’ reflections and give an adequate and balanced feedback to the adolescent [13]. Text-based mobile health interventions (i.e., text messaging or short message services, SMS) have been used as an mTherapy intervention, which guarantees also the immediate delivery of interventional reminders, supportive messages, self-monitoring and informative sharing [19]. Text-based communication are fast and allow an interaction, which potentially builds youngsters’ trust [13]. Evidence-based apps, eTools and social networking may promote self-managed mental health and wellbeing for youngsters and support integrated online initiatives with schools, workplaces and universities [23]. mTherapy refers to the use of mobile phone devices, smartphones and mobile applications (aka ‘apps’) in the delivery of mental health care services. Currently, mTherapy offer help with diagnosing, self-monitoring, self-awareness, symptom tracing and documentation, appointment and therapy homework reminders as well as adherence to traditional therapy [19]. In addition, e-consultations (aka e-consult/eConsult) may involve a physician who asks for a consultation related to questions outside of their expertise by using a VC modality [10]. Finally, sensors and wearable technologies (i.e., patches, bandages, shirts, smartwatches, smart glasses, wristbands, etc.) may offer a further digital tool useful for monitoring, assessing and treating Youth Mental Health conditions [15,16,28].

1.4. Aims of the Paper

The current COVID-19 pandemic posed clinicians in the condition to modulate and change mental health service delivery and treatment in order to guarantee the continuity and the management of ex novo mental health issues. However, most countries have not adequately prepared and equipped in the implementation process of TMH, especially in the context of Youth Mental Health. The major concerns and obstacles reside in the lack of equipment for TMH as well as a general poor IT knowledge and skill among mental health professionals. However, VC or audio calls TMH interventions appear to be the most feasible and easy to access and to be administered worldwide, especially in low-middle income countries. For this reason, the aim of the present paper is at providing an overview on the current state-of-the-art in the field of TMH interventions in Youth Mental Health, by focusing on both therapist-delivered online psychotherapy and telepsychiatry by the use of VC and audio calls, by excluding all interventions based on m-Health, MHealth and smartphone systems which may not be easily accessible to all countries.

Furthermore, being mental health problems among young people mainly represented by anxiety, depression and OCD, we conducted a retrospective file systematic review of all peer-review literature regarding the application of TMH in youth depression, anxiety and obsessive compulsive disorder. A review of all objectively selected, critically assessed, and reasonably synthetized evidence on available published data, available up to 25 January 2021, was undertaken.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Sources and Strategies

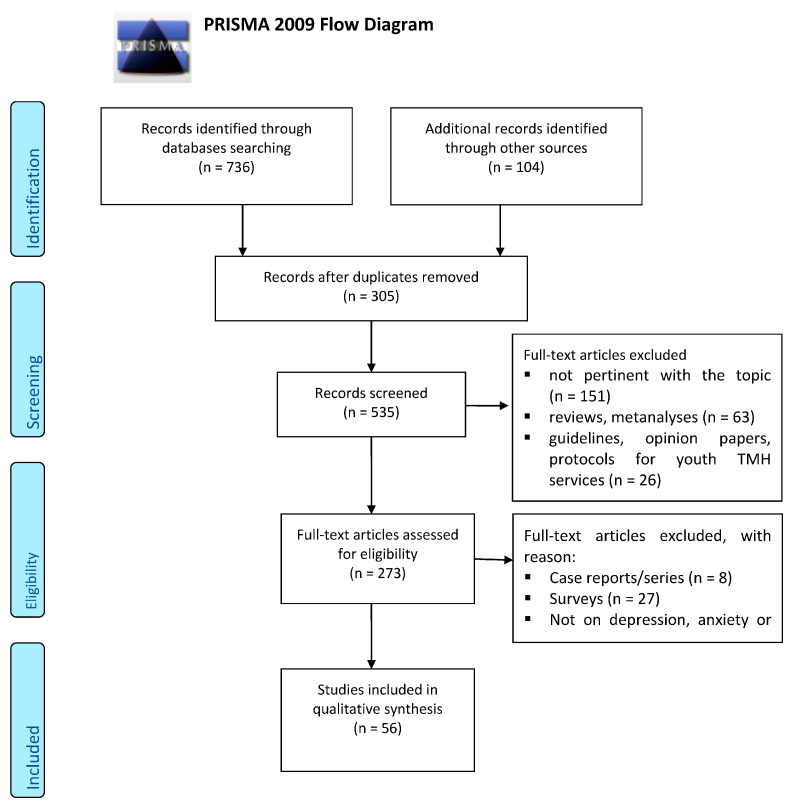

A systematic literature search, according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Metanalysis (PRISMA) guidelines, was performed by using the following electronic databases (last update: 25 January 2021): PubMed, MEDLINE, EMBASE and Google Scholar online databases, by combining the search strategy of free text terms and exploded MESH headings for the topic of “Telemental health (TMH)”, “Telepsychiatry”, “Telepsychotherapy” and “Adolescent Psychiatry” as follows: (((Telepsychiatry[Title/Abstract]) OR (Telemental health[Title/Abstract]) OR (Telepsychotherapy[Title/Abstract]) OR (Tele*[Title/Abstract]) OR (remote[Title/Abstract]) OR (Videoconferencing[Title/Abstract])) AND (Youth Mental Health[Title/Abstract])). A further search strategy was applied with the following keyterms: (((Telepsychiatry[Title/Abstract]) OR (Telemental health[Title/Abstract]) OR (Telepsychotherapy[Title/Abstract]) OR (Tele*[Title/Abstract]) OR (remote[Title/Abstract]) OR (Videoconferencing[Title/Abstract])) AND ((Depress*[Title/Abstract]) OR (Anxiety[Title/Abstract]) OR (Obsessive Compulsive[Title/Abstract]))). The strategy was first developed in MEDLINE and then adapted for use in other databases (Appendix A). The search was limited to “humans”, English papers and peer-reviewed journals. No limitation on the year of publication of was applied. Full papers of all potentially relevant studies and those papers whose abstract was insufficient to determine eligibility, were obtained and analyzed. Full text papers were further screened and discarded if they did not meet the inclusion criteria. Further references were retrieved through hand-searches of reference listings of review studies and of the included studies were also checked and examined for further references to be included.

2.2. Study Selection, Data Extraction and Management

We evaluated all studies specifically investigating TMH in Youth Mental Health, by excluding all papers addressing only adult people, m-Health, MHealth, and applications. We examined all titles and abstracts and obtained full texts of potentially relevant papers. Duplicate publications were excluded. All abstracts and titles describing apps for mobile devices (mHealth), e-Mental Health or virtual reality exposure treatment were excluded, even though they were targeted to young people. All experimental and observational study designs were considered, excluding case reports. Randomized, controlled clinical trials involving humans were prioritized, even though observational studies have been considered and included if pertinent. Narrative and systematic reviews, letters to the editor and book chapters were excluded as well for the specific aim of the systematic review but considered useful for the background of the research. In particular, all abstracts and titles evaluating TMH in Youth Mental Health were included if they were pertinent to the treatment of depression, anxiety and/or Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD). Whilst those addressed to neurodevelopmental disorders, autism spectrum disorders (n = 13), youth bipolar disorder (n = 0), youth Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) (n = 7), youth psychosis/schizophrenia (n = 5), youth eating disorders (n = 2) and youth posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or stress-related disorders (n = 1) were excluded. Moreover, those studies recruiting young people affected with depression, anxiety or obsessive compulsive disorders but not specifically evaluating the efficacy of TMH services were excluded in the present analysis, such as those specifically focusing on the level of satisfaction, level of engagement and users’ experiences and perceptions.

2.3. Characteristics of Included Studies

Of the 840 abstracts initially identified, 305 were excluded because of duplicates. Of the 534 remaining papers, 151 papers have been excluded as they do are not pertinent with the main topic of the present review (i.e., studies not addressed to TMH, studies not concerning with the application of TMH in mental disorders, etc.); whilst 63 studies were eliminated because of reviews or metanalyses, 19 are opinion papers or protocols on Youth TMH services, 6 are TMH protocols not designed to youngsters, 7 are guidelines and 16 are letters to editor. Amongst those remaining 273 papers, 8 are case reports/case series and 27 are surveys regarding the perceptions and level of satisfaction amongst clinicians who provide a TMH to youngsters or amongst young people or their parents. Further 182 articles were eliminated from the remaining 237 full-text articles after an assessment of eligibility by reading the full text articles, as they are pertinent to only TMH Adult services, without data on youngsters (n = 137) or they are addressed to young people but not specifically on depression, anxiety or obsessive compulsive disorder (n = 45). Finally, a total of 56 full-text articles met the inclusion criteria for the present review, as illustrated in the flow diagram detailing the review process and results at each stage (Appendix B). The findings have been classified according to the following diagnostic categories: studies on TMH applied to youth depression (n = 29), to only youth anxiety (n = 12) or mixed youth anxiety/depression (n = 7) and youth OCD (n = 8) and summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of retrieved papers.

| Study | Sample Features | Intervention | Advantages | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety | ||||

| [29] | 49 children (M 33; F 16), aged 7–13 yy, with a principal anxiety disorder |

|

Findings support the feasibility, acceptability and beneficial effects of CCAL for anxious youth. |

|

| [30] | 115 clinically anxious adolescent, aged 12 to 18 yy (M 47; F 68) and their parents |

|

Online CBT, with minimal therapist contact, for adolescent anxiety disorders offer an efficacious alternative to clinic-based treatment. |

|

| [31] | 52 pre-school r children (M 24; F 28), aged 3–6 yy, with clinical anxiety disorders (ADIS-C) |

|

|

|

| [32] | 433 parents of children aged 3 to 6 yy, with an inhibited temperament (OAPA) |

|

|

|

| [33] | 73 children (33 M; 40 F) with anxiety disorders (ADIS-C/P), aged 7–12 yy, and their parents. |

|

|

|

| [34] | 72 clinically anxious children (M 42; F 30), aged 7–14 yy |

|

The internet treatment content was highly acceptable to families, with minimal dropout and a high level of therapy compliance. |

|

| [35] | 5 adolescents (M 1; F 4), aged 14–16 yy, with anxiety disorder (ADIS-C) |

|

Participants were generally satisfied with multimedia content, the modules and the delivery format of the program. |

|

| [36] | 43 adolescents (M 16; F 27), aged 17–17 yy, with primary diagnosis of anxiety (ADIS-C/P & SCAS-C/P) |

|

The Cool Teens program is an efficacious option for the treatment of adolescent anxiety. |

|

| [37] | 19 high school students, aged 15–21 yy, with social anxiety disorder (SPSQ-C & MADRS-S) |

|

Internet-delivered CBT could be an option to treat high school students although strategies to increase compliance should be found. |

|

| [38] | 66 distressed university students (DASS-21) |

|

An individual-adaptable, internet-based, self-help programs can reduce psychological distress in university students. |

|

| [39] | 558 internet users, recruited via the Australian Electoral Roll | The sample was randomly assigned to 5 arms:

|

This trial is not able to demonstrate the preventative effects of the website on anxiety symptoms as measured by the GAD-7. |

|

| [40] | A three-arm cluster stratified randomised controlled trial take in consideration 1767 students (M 37.2%; F 62.8%) about anxiety disorder |

|

The e-couch Anxiety and Worry program did not have a significant positive effect on participants. |

|

| [41] | 340 adolescents (M 42.4%; F 57.6%), aged 11–18 yy, recruited from 14 regular high schools in the Netherlands | To evaluate the efficacy of CBM-A, the sample was randomly allocated to eight sessions of a dot-probe (DP), or a visual search-based (VS) attentional training, or one of two corresponding placebo control conditions and received 8 sessions of an online training over four weeks. | More research is needed to investigate and improve the efficacy of CBM-A in adolescents. |

|

| [42] | 108 adolescents (M 33.3%; F 66.7%), aged 11–19 yy, with symptoms of anxiety and/or depression (SCARED & CDI) | The current study investigated the effects of eight online sessions of visual search (VS) ABM, following four weeks, compared to both a VS placebo-training and a no-training control group online training sessions. | There is no evidence for the efficacy of online visual search ABM in reducing anxiety or depression or increasing emotional resilience in selected adolescents. |

|

| [43] | 173 participants |

|

Results suggest that interpretation training as implemented in this study has no added value in reducing symptoms or enhancing resilience in unselected adolescents. |

|

| [44] | 13 youth (M 6; F 7), aged 8–13 yy, with a primary/co-primary anxiety disorder diagnosis and their mothers |

|

Videoconferencing treatment formats may serve to improve the quality care of youth anxiety disorders. |

|

| [45] | 49 undergraduate students (M 4; F 45) who were seeking counseling for mild to moderate anxiety |

|

The findings provide support for the treatment of college students with anxiety with SFBT through online, synchronous video counseling. |

|

| [46] | Develop a Therapist-assisted Online Parenting Strategies (TOPS) program that is acceptable to parents whose adolescents have anxiety and/or depressive disorders, using a consumer consultation approach | TOPS intervention was developed via three linked studies.

|

This study provided preliminary support for the feasibility, acceptability and perceived usefulness of the TOPS program |

|

| Depression | ||||

| [9] | Observational an 18-month program for children less than 18 years (n = 87) who received physical and mental health assessment by ED physician | Wabash Valley Rural Telehealth Network utilizes an on-demand design with a centralized “hub” of medical providers that delivers specialty based psychiatric care via a regional telehealth network. | Decreasing waiting time in ED for those children and adolescents who need a CAP specialist in remote areas without CAP. |

|

| [47] | 1477 students (M 651; F 826), aged 12–17 yy, from 32 schools across Australia |

|

Although small to moderate, the effects obtained in the current study provide support for the utility if prevention programs in schools. |

|

| [48] | 38 families e 28 children (20 M; 6 F), aged 8–14 yy, with childhood depression (K-SADS-P & CDI) |

|

NA |

|

| [49] | 297 patients (M 32%; F 68%), aged 18–75 yy, having a new episode of depression (BDI & CIS-R) |

|

This type of therapy appeals in particular to those who like to write their feelings down, those who value the opportunity to review and reflect on the dialogue of the therapy session, and those who prefer the anonymity offered by this method of delivering CBT.It could be an alternative to face-to-face treatment for those whose first language is not English.The intervention may also be useful when traveling is difficult or expensive because of rurality, disability or social phobia. |

|

| [50] | 244 young people, aged 16–25 yy, with depressive symptoms (CES-D) |

|

MYM course was effective in reducing depressive and anxiety symptoms and increasing mastery in young people. |

|

| [51] | 363 children and adolescents, aged ≥ 12 yy, with subsyndromal symptoms of depression (PHQ-A) recruited at five sites across Germany, by the German ProHEAD consortium. |

|

|

|

| [52] | 79 boys, aged 15–16 yy |

|

Considering the high drop-out rate there is the need to review the appropriateness and difficulty of the material as well as the formats used in Internet programs. |

|

| [53] | 157 girls, aged 15–16 yy, come from a single sex school in Canberra, Australia | Students were allocated to undertake either MoodGYM or their usual curriculum. |

|

|

| [54] | 263 young individuals aged 12–22 yy with depressive symptoms (CES-D) |

|

Chat condition demonstrated a reliable and clinically significant improvement at 4.5 months, but not yet at 9 weeks. |

|

| [55] | 84 adolescents, aged 14–21 yy, at risk for developing major depression (PHQ-A) were selected through the CATCH-IT project |

|

In the BA condition, the physician takes a directive approach and advises the adolescent that he is experiencing a depressed mood and refers the adolescent to the CATCH-IT internet site. |

|

| [56] | 84 adolescents, aged 14–24 yy, recruited when they visited the primary care provider for risk of depressive disorder, as well as through advertisements posted in and around the clinics. |

|

This tool may help extend the services at the disposal of a primary care provider and can provide a bridge for adolescents at risk for depression. |

|

| [57] | 84 participants (M 43.4%, F 56.6%), with mean age of 17.47 yy, were recruited by screening for risk of depression in 13 primary care practices |

|

It would be useful to make these interventions more accessible to adolescents given their good effectiveness. |

|

| [58] | 83 adolescents recruited from 12 primary care sites across Southern and Midwestern United States |

|

The tool may help extend the services at the disposal of a primary care provider and can provide a bridge for adolescents at risk for depression. |

|

| [59] | 34 students were recruited from nine schools | A pilot study employed a pre-test/post-test design with 8-week intervention based on the Reframe Internet-based program interventions. It consists of 8 modules, based on CBT, each of which takes around 10–20 min to complete. | The finding are promising and suggest that young people at risk of suicide can safely be included in trials as long as adequate safety procedures are in place. |

|

| [60] | 62 participants with major depressive disorder were defined by two age subgroups: adolescents (n = 31), aged 13–18 yy (CDRS-R), and young adults (n = 32), aged 19–24 yy (HAMD). |

|

Spirituality is increasing as an important consideration in mental Health and mental health interventions. |

|

| [61] | 3224 youth (M 1676; F 1568), aged 11–18 yy, selected from 5 schools in the Red Deer Public School system |

|

Suggesting that a multimodal school-based program may provide an effective and pragmatic approach to help reduce youth depression and suicidality. |

|

| [62] | 42 youth (M 22; F22), aged 15–25 yy, affected by depression in partial or full remission |

|

These types of online social networking are well appreciated by the young people, and further studies would be needed to perfect their development. |

|

| [63] | 104 participants, aged 18–25 yy, with moderate depression symptomatology (DASS-21) and use of alcohol at hazardous levels (AUDIT) |

|

DEAL Project it could be a good option for patients with both depression symptoms and alcohol use. |

|

| [64] | 257 Chinese adolescents, aged 13–17 yy, with mild-to-moderate depressive symptoms were recruited from three secondary schools in Hong Kong |

|

Poor completion rate is the major challenge in the study. |

|

| [65] | 208 Dutch female adolescents with elevated depressive symptoms (RADS-2) |

|

Videogames could be a good strategy to improve the compliance of adolescents for computerized CBT. |

|

| [66] | 107 participants (M 8%, F 92%), aged 17–48 yy, recruited at The University of Queensland Health Service |

|

It could be useful to introduce LI-CBT in the university system, even if further studies are needed. |

|

| [67] | 206 female students, aged 18–25 yy, at very high risk for eating disorder onset (WCS) |

|

IaM is an inexpensive, easy intervention that can reduce ED onset in high-risk women. |

|

| [68] | Web-based awareness and self-management protocol to mild-to-moderate depression |

|

Protocol for the development, implementation and evaluation of the iFight Depression tool, cost-free, multilingual, guided, self-management program for mild-to-moderate depression cases. |

|

| [69] | 927 students, enrolled in universities in Massachusetts, were recruited to join the web-based screening survey for depression. |

|

Current online technologies can provide depression screening and psychiatric consultation to college students. |

|

| Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder | ||||

| [70] | 31 youth (19 M; 12 F), aged 7–16 yy, with OCD (CY-BOCS & ADIS-C/P) |

|

This preliminary study suggests the possible role of W-CBT in reducing OC symptoms in youth with OCD. |

|

| [71] | 22 child (13 M; 9 F), aged 4–8 yy, with OCD (ADIS-C/P & CY-BOCS) |

|

VTC methods may offer solutions to overcoming traditional barriers to care for early-onset OCD. |

|

| [72] | 3 female patients with a story of OCD |

|

Manualized CBT for OCD can be effectively delivered via a VC network. |

|

| [73] | 6 patients (M 1; F 5) with history of OCD (ADIS) |

|

Internet-delivery CBT may be a promise method treatment for OCD patients. |

|

| [74] | 15 adults (M 13.3%; F 86.7%) with OCD |

|

This study adds to the growing body of literature suggesting that videoconference-based interventions are viable alternatives to face-to-face treatment. |

|

| [75] | 21 participants, aged 12–17 yy, with OCD (MINI-KID) and their parents |

|

ICBT could be efficacious, acceptable and cost-effective for adolescents with OCD. |

|

| [76] | 72 adolescents, aged 11–18 yy, with OCD and their parents |

|

TCBT is an effective treatment and is not inferior to standard clinic-based CBT. |

|

| [77] | 30 children, aged 7-17, with primary diagnosis of OCD, and their parents |

|

NA |

|

CBT: Cognitive Behavioural Therapy; ICBT: internet based CBT; TCBT: Telephone CBT; W-CBT: web-camera CBT; VC: Videoconferencing; VTC: Video Teleconferencing; F: Female; M: Male; NET: Internet-based CBT; WLC: Waitlist control; CCAL: Camp Cope-A-Lot; TMH: Telemental Health; IPT: Interpersonal Psychotherapy techniques; BAC: Behavioral Activation; FCBT: family based CBT; VTC-FB-CBT: Video Teleconferencing-delivery family-based cognitive-behavioral therapy; CBM-A: Cognitive Bias Modification of Attention; ABM: Attentional Bias Modification; CBM-I: Cognitive Bias Modification for Interpretations; CATCH-IT: Competent Adulthood Transition with Cognitive-behavioral Humanistic and Interpersonal Training; OAPA: Online Assessment of Preschool Anxiety; ADIS-C/P: Anxiety Disorder Interview Schedule: Child and Parent; W-SFBT: Web-Solution Focused Brief Therapy DASS-21: Depression and Anxiety Stress Scale-21 CY-BOCS: Children’s Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale; K-SADS-P: Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School Age Children-Present Episode; SPSQ-C: Social Phobia Screening Questionnaire for Children up to 18 Years Old; MADRS-S: Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale; SCAS-C/P: The Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale-Child/Parent Version CDI: Children’s Depression Inventory; yy: years; OC: Obsessive Compulsive; OCD: Obsessive-compulsive Disorder; BTPS: Barriers to Treatment Participation Scale; WAI: Working Alliance Inventory, Parent-Report and Therapist-Report; CSQ-8: Client Satisfaction Questionnaire; SCARED: Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders; CGI: Clinical Global Impressions Scale; MASC-C/P: Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children, Child and Parent Reports; CBCL: Child Behavior Checklist; FACLIS: Family Accommodation Checklist and Interference Scale; BAI: Beck’s Anxiety Inventory; CCAPS College Counseling Assessment of Psychological Symptoms; Therapist-assisted Online Parenting Strategies; BDI: Beck Depression Inventory; CIS-R: Revised Clinical Interview Schedule; QUALYs: quality-adjusted life-years; CES-D: Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; HADS: Anxiety subscale of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; PSWQ: Penn State Worry Questionnaire PHQ-A: Patient health Questionnaire-9 modified for Adolescent; CASQ-R: The Revised Children’s Attributional Style Questionnaire; RSE: Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale; ADHEALTH: National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health; CDSR-R: Children’s Depression Rating Scale Revised; HAMD: Hamilton Depression Rating Scale for Depression; MINI: Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview; DEAL: Depression Alcohol Project; AUDIT: Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test; RADS-2: Reynolds Adolescent Depression Scale; OVK: school-based CBT prevention program ‘OP Volle Kracht’; SPARX program: computerized CBT program “SPARX”; LI-CBT: Low-Intensity cognitive-behaviour therapy; K10: Kessler10; CSE: Coping Self-Efficacy scale; WHO5: 5-item World Health Organization Well-Being Index; IaM: Image and Mood program; WCS: Weight Concerns Scale; ED: Eating Disorder; EDE-Q: Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire; EDI-2: Eating Disorder Inventory BDI-II: Beck Depression Inventory-II; ERP: Exposure and Response Prevention; SCID: Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM; Y-BOSC: Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale; WSAS: Work and Social Adjustment Scale; WAI-S: Working Alliance Inventory; MINI-kid: Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview for Children and Adolescents; QLESQ: Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire short form; RTQ: Reaction to Treatment Questionnaire; CSS: Client Satisfaction Survey; TVS: Telepresence in Videoconference Scale; PEAS: Patient EX/RP Adherence Scale; ChOCI-R: Children’s Obsessional Compulsive Inventory Revised; COIS-R: Child Obsessive-Compulsive Impact Scale; CGAS: Children’s Global Assessment Scale; SDQ: Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire; FAS-PR:: Family Accommodation Scale, Parent-Report.

3. TMH in Youth Mental Health

Research supported the feasibility and efficacy of computer-based treatments for youth anxiety and related disorders [29,30,31,32,78,79]. Several TMH sessions are based on self-administered platforms and behavioural intervention technologies with or without minimal therapist support, only leverage asynchronous communications between therapists and families [29,30,32,33,47,80] or technology-enhanced programs that augment face-to-face services conducted in the clinic [81]. Whilst synchronous TMH formats, which applies VC to deliver real-time treatment between therapists and families have been mainly applied to relatively small sample size of youth with anxiety-related conditions or OCD [70,71,82], depressed youth or externalizing youth [48]. Most of these TMH programs demonstrated a treatment response rates of 60–80% and a relatively comparability with clinic-based, face-to-face outcomes [30,82,83].

3.1. Anxiety Disorders

Using an internet-based approach, Spence et al. [34], developed and tested an online CBT-based program for youth anxiety disorders (BRAVE-ONLINE) in children (aged 7–12 years), comparing the internet-based approach with the clinical-based one, by demonstrating s significant reductions in anxiety symptomatology in both modalities. Another study by Spence et al. [30] carried out a randomized trial comparing computer-assisted CBT, in-person CBT and a waitlist control amongst 72 children affected with anxiety disorders (aged 7–14 years old), by delivering 6 sessions via the Internet and 6 in-person sessions in a clinic-based group treatment format. The findings of the study reported a significant reduction in anxiety symptomatology in both groups with active treatment, compared to the waitlist condition [30]. Accordingly, another Internet-based individual CBT program relative to a waitlist control in 73 children with anxiety disorders (aged 7–12 years) reported a significant reduction in anxiety symptomatology and a greater increase in adaptive functioning relative to the waitlist arm [33]. Khanna and Kendall [29] carried out a randomized trial of a computer-aided CBT protocol (Camp Cope-A-Lot[CCAL]), relative to in-person CBT and an Education/Support/Attention (ESA) control condition in 49 non-OCD anxious youth (aged 7–13 years old), by documenting a significant improvement in anxiety levels in both treatments compared to the ESA arm [29]. These improvements were maintained at 3-month follow-up. Similarly, the ‘Cool Teens’ program (i.e., a eight-session, CD-ROM-based program) demonstrated a clinically significant efficacy in improving anxiety symptomatology amongst adolescents in two studies [36,37]. A Sweden RCT using online CBT to reduce social anxiety, depression and general anxiety in high school students in a 9-week intervention consisting of psychoeducation, cognitive restructuring and exposure therapy, reported a significant decrease in social anxiety, social phobia, anxiety and depression levels which were maintained at the 1-year follow-up [37]. A Canadian RCT recruiting university students to test the effects of a self-help online intervention, including CBT, coaching, psychoeducation and relaxation together with audio files, pictures, videos and online activities, reported an improvement in depression, anxiety and stress levels, which were maintained at the 6-month follow-up [38]. An Australian 10-week online intervention consisting of five trail arms based on the presence of email or telephone reminders and consisting of 10 modules of CBT, psychoeducation, physical activity promotion, relaxation and mindfulness medication techniques, reported a significantly higher improvement in anxiety symptomatology at 12 months [39]. An Australian RCT recruiting students who were administered a 6-week online intervention at school consisting of CBT, psychoeducation, relaxation and physical activity named ‘Y-Worri/E-couch Anxiety and Worry Program’, described a significant improvement in anxiety levels after the TMH sessions [40]. A series of online attentional bias modification training RCTs were performed in the Netherlands, by recruiting high school students who reported a significant reduction in negative attentional bias for the visual search group [41,42,43]. A pilot study evaluating feasibility, acceptability and preliminary efficacy of real-time, Internet-delivered and family-based cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) for anxious youth (n = 13) delivered to the home setting over the Internet using VC [44]. The intervention was feasible and acceptable to families who reported high treatment retention, high satisfaction, strong therapeutic alliance and low barriers to participation. The treatment showed efficacy with 76.9% of the intention-to-treat sample and 90.9% of treatment completers who achieved treatment response at the Clinical Global Impressions-Improvement Scale in post-treatment. These findings have been maintained at 3-month follow-up evaluation [44]. An online, randomized, non-inferiority design, synchronous VC to in-person counselling using solution-focused brief therapy in a sample of college students who were seeking help for mild-to-moderate anxiety, showed significant changes in Beck Anxiety Inventory scale and in social anxiety levels in both interventions without any significant differences in effectiveness of the two delivery methods [45]. A feasibility pilot study of a therapist-assisted online parenting strategies (TOPS) program addressed to parents whose adolescents (aged 12–17 years) are affected with anxiety and/or depressive disorders reported an overly acceptability and perceived usefulness of a web-based program which also involves parents/caregivers of affected adolescents [46].

Overall, a total of 4,038 patients were recruited in 18 studies, of which 3 studies providing findings and clinical observation during a short-term period (i.e., less than 1 month) [37,38,41], 8 studies followed up patients over a medium-term period (i.e., up to 3 months) [29,30,33,34,36,42,44], while 7 studies were carried out by collecting data during a long-term period (i.e., more than 3–6 months) [31,32,37,39,40,43,45]. Overall, six studies provided I-CBT treatment, one implemented an online-parenting CBT-based intervention, two studies administered a CD-ROM-based CBT online program, one study administered a self-help CBT-based online CBT plus psychoeducation, two studies administered I-CBT plus psychoeducation (of which one study which provided also a relaxing program and physical activity), one study administered a VS-based CBM-A, one a VS-based ABM training, one study administering a CBM-1 training, one study investigated the efficacy of a TMH-based FCBT program, one study administered SFBT, and one a TOPOS program.

All studies demonstrated that TMH intervention determined an improvement in anxiety symptomatology, which seems to persist over the time. Moreover, literature so far published reported the overall superiority of the TMH-based interventions compared to placebo and, at least, a comparable efficacy to the face-to-face modality [29,30,31,32,33,34,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45]. In addition, patients and their relatives reported from moderate to higher satisfaction rate following these TMH-based interventions.

3.2. Depression

TMH interventions, including both computer-based and therapist-delivered online psychotherapy (i.e., cognitive behaviour therapy, CBT), for depression in youth have been demonstrated to be efficacious, cost-effective and very comparable with face-to-face treatment [49,50,51,84,85,86]. Overall, despite the benefits of TMH interventions for depression, there is a lack of studies specifically focusing on adolescents and with longer-term follow-up, most of them displaying only short-term follow-up periods are represented by self-guided (i.e., delivered with an asynchronous modality) interventions [20]. Several controlled trials applied a self-directed Internet intervention for depression in a youth population (aka ‘MoodGYM’, i.e., delivered as a part of the high school curriculum) including five modules based on CBT focusing on prevention, education, and treatment addressed to depressive symptoms, by reporting an overall reduction of depressive symptomatology [47,52,53]. An Internet-based, Dutch, solution-focused, brief chat, prevention intervention (named ‘Grip op Je Dip’ or ‘Dutch for Master your Mood/MYM’) for adolescents with subclinical depression consisting in six 90-min online chat room sessions focused on CBT, BA and future planning, reported significant reduction in depression and anxiety which continued during the 6-month follow-up period [50]. PratenOnline, a one-on-one chat intervention with trained professionals running Solution-Focused Brief Therapy (SFBT) reported an improvement of depressive symptomatology which continued to decrease steadily over a 7.5-month follow-up [54]. The Project CATCH-IT (Competent Adulthood Transition with Cognitive-Behavioural and Interpersonal Training) is a primary care-centered interventional website designed to prevent depression in at-risk adolescents, by applying the principles based on CBT, Interpersonal Psychotherapy (IPT) and Behavioural Activation (BA) [55,56,57,58]. These studies reported a significant improvement in depressive symptomatology, loneliness scores and hopelessness scores which persisted from the 6-month to 2.5-years of follow-up [57,58]. A pilot study evaluated an online intervention for at-risk school students, by reporting a reduced suicidal ideation, hopelessness and depressive symptoms [59]. A RCT on a spirituality informed e-mental health tool as an intervention for major depressive disorder in adolescents and young adults and a RCT on a school-based CBT program described an improvement of depression and suicidality [60,61]. A single-group pilot study was carried out to evaluate a moderated online social therapy intervention named ‘Rebound’ for depression relapse prevention in young people, by reporting a significant improvement at Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) (p = 0.014) [62]. An Australian intervention for youth called the DEAL Project evaluated co-occurring depression and alcohol misuse, by the application of a 4-week online intervention including four 1-h modules in the areas of CBT, MI, psychoeducation, BA, relaxing and mindfulness, coping strategies [63]. However, the study did not report any significant differences between intervention and control group over a 3- or 6-month period of follow-up [63]. ‘Grasp The Opportunity’ took place in Hong Kong and comprised the CBT, BA and resiliency themes from the original CATCH-IT website, by recruiting 257 Chinese youth who were asked to work through 10 online depression prevention modules and reported benefit at 12-months follow-up in the improvement of depressive symptomatology [64]. A randomized controlled trial compared a fantasy videogame named ‘SPARX’, applied to help adolescents with depressive symptoms over 7 weeks, to a control group, described a significant reduction in depressive symptomatology at the 12-month follow-up [65]. A RCT randomized a low-intensity CBT (LI-CBT) intervention versus self-help control arm in a sample of subclinical depression of university students, by reporting significant improvement in depression and anxiety at 2 months and over a 12-month period of follow-up [66]. An online 10-week active intervention, named ‘Image and Mood’ (aka ‘IaM’), consisting of CBT, IPT, BA, stress management and problem solving, was applied on female students at very high risk of developing an eating disorder with comorbid depression [67]. There was a significant improvement of eating and depressive symptomatology in iCBT group compared to the control group with a maintenance up to 1-year of follow-up [67]. A multicenter, randomized controlled E-motion trial, belonging to the German ProHEAD consortium (Promoting Help-seeking using E-technology for Adolescents), investigated the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of two online interventions to reduce depressive symptomatology in high-risk children and adolescents with subsyndromal symptoms of depression in comparison to an active control group [51]. The first intervention group complete the iFightDepression® (iFD® tool) which is an online, clinician-guided, self-management program aimed to help subjects with mild-to-moderate depression to self-manage their symptoms [68] whilst the second intervention group receive a clinician-guided, online, group chat intervention based on a CBT approach. Both groups are compared to a control intervention group who access to structured online psychoeducational modules on depression, however, the results of the study should be still published [51]. An observational 18-month TMH program by Fairchild et al. [9] reported an increased access to care for youngsters dealing with suicidality, depression, and anxiety in rural emergency departments. Similar findings have been previously reported in a study evaluating TMH resource usage by high school students, which reported that teens who reported depression symptoms, higher stress or suicidality were less likely to talk to a parent about stress or psychological distress but more likely to use TMH services or an online counselor to seek help [21]. A feasibility and acceptability study investigating a web-based model, including Skype, to screen and provide psychiatric consultation to 285 (out of 972 of the total sample) depressed college students, who reported the tool helpful in helping them understand their depression (76.4%) and thought that psychologists and psychiatrists could successfully see patients via VC (88.2%) [69].

In conclusion, a total of 8432 individuals were recruited from 24 studies here retrieved and analyzed on depression. Of which, 7 studies were conducted with a short-term follow-up (i.e., less than 1 month), 7 with a medium-term follow-up (i.e., up to 3 months) whilst 8 studies with a longer-term follow-up period. Among all studies, one study was based on a regional TMH work, one was based on a self-direct I-CBT program, one was based on W-CBT, one on VC-CBT, five studies were carried out to administer I-CBT intervention, two were based on a clinical-guided self-management program, one on a W-SFBT, five studies were based on a BA/MI intervention plus ICB, IPT and community resiliency concept, one study was performed to administer a I-CBT plus BA, MI, psychoeducation, relaxing, mindfulness, and coping strategies, one study was based on a spirituality-based e-mental health intervention, one study was based on online social networking, one study administered a videogame SPARX, one study on LI-CBT, one study on ICBT plus IPT, BA, stress management and problem solving, and one study was based on an online depressive toolkit. Overall, These THM-based interventions reported a good improvement in depressive symptomatology, which was maintained over the time, a superiority compared to placebo and a comparable efficacy to other types of face-to-face interventions. Moreover, these types of THM appear to be acceptable and feasible to patients and their relatives.

3.3. Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD)

VC interventions may be superior to other remote interventions (i.e., self-help, telephone-mediated psychotherapy or Telepsychiatry) as they may enhance face-to-face element of therapy and increase the accountability and adherence of patient [70,71,72,73,74,75,76]. However, most of studies carried out on OCD patients have small samples and intervention utilized expensive VC equipment [72,73]. A Swedish clinical trial named BiP (BarnInternetProjektet) OCD consisting in a 12-week, 12-chapter Internet-based intervention of CBT and psychoeducation delivered through film, exercises, animation and interactive scripts addressed to adolescents and their parents [75]. The intervention demonstrated an improvement in OCD symptomatology, which was maintained at the 6-month follow-up [75]. A RCT non-inferiority trial compared face-to-face CBT with telephone-CBT (TCBT) in a sample of 72 adolescents with OCD, by reporting a significant improvement in OCD and depressive symptomatology that persisted until 6-month follow-up [76]. An evidence-based treatment protocol for real-time delivery over webcam of CBT (W-CBT) intervention compared to a 4-week waitlist period reported a treatment response in OCD symptomatology in 81% of the youth sample with OCD with W-CBT compared to the waitlist arm with OCD improvements, which were maintained at a 3-month follow-up [70]. A pilot study evaluated an Internet-delivered family-based CBT intervention on a sample of early-onset OCD young people, by reporting an OCD symptomatology improvement and global severity improvements from pre- to -post-treatment [71]. An open label study explored the acceptability, feasibility and effectiveness of a newly developed enhanced CBT (eCBT) to children and adolescents [77]. The eCBT includes VC sessions, such as supervision and guided exposure exercises at home in addition to face-to-face sessions), an interconnected app designed for children, their parents and the therapists and an online assessment with direct feedback to patients and the therapist. The study was applied to 30 children (aged 7–17) with a primary diagnosis of OCD according to the DSM-5 criteria and their parents. The findings are still ongoing [77]. Overall, among 8 papers here retrieved, 2 were short-term, 4 medium-term, 1 with a long-term follow-up while only one is still ongoing not providing preliminary results but only a research protocol. A total of 200 patients were considered. One study investigating the use of W-CBT, one VTC-FB-CBT, one a manualized-CBT, one an intervention based on I-CBT only while one study combining I-CBT plus psychoeducational intervention, one study administering a VC-mediated-ERP intervention and one an eCBT. Therefore, a comparison of these studies is limiting being represented by not homogeneous interventions online delivered for OCD. However, all seven studies reporting preliminary findings showed a significant improvement in OCD symptomatology, which persisted over time [70,75,77], a superiority over placebo [70] and a comparable efficacy compared to face-to-face interventions [76], particularly among those studies in which the sample was randomly assigned to the intervention or WLC/face-to-face modality.

4. Discussion

Nowadays, TMH approaches using VC to hold real-time, remote treatments with a live therapist have shown increasing support for a range of youth mental health problems, including anxiety disorders, depression, schizophrenia, substance abuse, posttraumatic stress disorders, neurodevelopmental disorders, oppositional defiant disorder, autism spectrum disorders, family conflicts and externalizing behaviours, without any specific contraindications to its use for any disorder or age range [17,19,31,70,71,82,87,88,89,90]. Moreover, further studies demonstrated how implementing a web-delivered approach as a supportive and complimentary tool to treatment as usual interventions may potentially improve the individual’ predisposition to be engaged to online tools for the prevention, assessment, monitoring and delivering of psychiatric and psychotherapy treatments. For example, Toscos et al. [91] demonstrated, through the use of an immediate-response technology (IRT), able to gather mental health care data and educate youth on TMH resources, that after interacting with IRT, 43% of youths expressed their willingness to use online self-help resources, 40% of them an online therapist, and 29% an anonymous online chat. These findings demonstrated a statistically significant preference of TMH services particularly amongst females (p < 0.01) and those who reported higher depression and anxiety scores (p < 0.001).

The advances in the quality and availability of desktop VC technologies together with an increasingly large and sophisticated evidence-based studies in the field of TMH, including randomized controlled trials (RCTs) demonstrating the efficacy of TMH interventions in the treatment of several mental disorders, facilitated the implementation of TMH interventions amongst youngsters with mental disorders [8,22]. However, despite these encouraging premises, there are still few studies, which specifically addressed the feasibility and effectiveness of TMH interventions amongst youngsters in naturalistic settings. Moreover, there are still missing guidelines specifically addressing TMH practice for each mental health disorder in CAP (i.e., treating youth depression or anxiety or bipolar disorder, etc. with TMH). Overall, most of studies here retrieved demonstrated the superiority of TMH interventions over the placebo or a comparable efficacy of TMH intervention to face-to-face modality with regards to studies on youth anxiety [29,30,31,32,33,34,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45] depression [9,21,38,46,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,83,84,85,86] or OCD [70,71,73,74,75,76,77,87]. Computer-assisted CBT approaches have been proposed as a complementary or alternative modes of treatment delivery aimed at increasing access to therapy for many mental health problems, including youth anxiety disorders [29,30,31,32,33,34,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45], depression [47,50,51,52,53,55,56,57,58,60,61,63,64,66,67] and OCD [70,71,76,77,87]. Overall, computer-assisted CBT approach appear to be acceptable to youngsters and their parents and feasible for implementation by providers, as well as it seems to produce significantly greater reductions in clinician-rated anxiety and greater improvements in overall functioning compared to control group [29,30,31,32,33,34,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,83]. Some studies also reported a sustained improvement in anxiety symptomatology over a longer time [30,40]. Furthermore, parent-focused Internet-delivered CBT appear to be as well effective as an early intervention in treating preschool-age children with anxiety disorders in a modified version of the BRAVE-ONLINE program [31]. Studies including mixed samples (i.e., individuals with anxiety and depressive symptomatology) similarly reported improvements in both clinical dimensions [37,40,41,42,43,46,83]. Moreover, both computer-based and therapist-delivered online psychotherapy (i.e., cognitive behaviour therapy, CBT) for youth depression have been demonstrated to be effective, cost-effective and very comparable with face-to-face treatment [49,50,51,84,85,86]. Overall, despite the benefits of TMH interventions for youth depression, there is a lack of studies specifically focusing on adolescents and with longer-term follow-up, with most of them which display only short-term follow-up periods which are self-guided (i.e., delivered with an asynchronous modality) [20]. Moreover, some studies also observed a sustained improvement in depressive symptomatology over the time [9,50,54,57,58,67]. In addition, a significant improvement in OCD symptomatology has been observed as well [70,71,75,76], also maintained over the time [70,76]. Despite these encouraging findings, there are several limitations, which should be here considered. Firstly, most of the studies here retrieved own extreme heterogeneous methodologies and study designs, including interventions delivered via TMH which are not always comparable (i.e., CBT vs IPT vs family-based interventions), with a different length of treatment (with some of them which do not provide a longer follow-up), without homogenous characteristics of the sample (i.e., some studies included only children, some included children and adolescents whilst others included only adolescents). Secondly, not all studies compared internet-delivered intervention vs face-to-face intervention vs placebo group. Thirdly, few studies own a large sample size, mainly being carried out on small sample sizes, with mixed samples (i.e., anxious and depressive individuals, some including both parents/caregivers and patients). Finally, some studies are only pilot study or evaluated the feasibility and acceptability of computer-assisted or internet-based CBT or TMH interventions, without reporting completed findings [29,46,69,77].Therefore, further studies should include longer term follow-up (in order to assess the effectiveness in naturalistic settings); larger sample sizes to examine mediators and moderators of outcomes following TMH interventions in youngsters affected with anxiety disorders, major depressive disorder or OCD; provide complementary parent self-report measures (in order to compare and integrate findings coming from self-report assessments provided by young people) and clinician-based assessments during each TMH session. Moreover, further studies should investigate and define specific standardized, age- and young-tailored Internet-delivered protocols address to youth anxiety disorders (i.e., social anxiety, generalized anxiety disorder, separation anxiety disorder, phobias, etc.), depressive disorders and OCD.

Furthermore, despite the current increased use of telepsychiatry and telepsychotherapy due to the current COVID-19 pandemic, there is still limited knowledge and a missing formal clinician training and universally recognized certification in the field of TMH adolescent psychiatry [8]. Following the recommendation by Hilty et al. [87] for further clinical guidance on TMH particularly amongst the youngsters, the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) proposed a practice parameter for Telepsychiatry with children and adolescents [88]. The AACAP in partnership with the American Psychiatric Association (APA) developed an online Child and Adolescent Telepsychiatry Toolkit in 2019 to address issues and concerns regarding the practice of Telepsychiatry with children and adolescents [89]. The toolkit, developed as complementary to the APA’s Telepsychiatry Toolkit for adults, includes a series of video series covering general topics in telepsychiatry (i.e., history, theoretical background, reimbursement and regulatory issues) and sections on training, practice and clinical issues, particularly focusing on CAP [89]. In 2017, the American Telepsychiatry Association (ATA) provided a clinical guidance for the delivery of child and adolescent mental health and behavioural services by a licensed health care provider through real-time VC [7,25]. Furthermore, in 2018, ATA and APA released a guide to assist mental health professionals in providing effective and safe mental health care regarding VC-based TMH [88,90,91].

In general, mental health professionals working with adolescents should be trained and acquire a set of competencies and skills essential for effectively practicing TMH interventions in CAP (Table 3) as well as overly trained in social media, mHealth, wearable sensors and asynchronous modalities [10,12,13,88]. Before starting a TMH session, clinicians should be able to introduce and clearly explain TMH modality to young patients and their parents, including what to expect and a basic explanation of the process, confidentiality and the needed equipment (Table 3) [6,22,54,88,89,90,91].

Table 3.

Core competencies and skills in TMH by Adolescent Mental Health professional.

| Basic technical/IT skills |

|

| Assessment skills in TMH |

|

| Relational skills in TMH |

|

| Communication skills in TMH |

|

| Collaborative and inter-professional skills in TMH |

|

| Administrative skills in TMH |

|

|

Medico-legal competencies

and skills in TMH |

|

| Ethno- and cultural psychiatry skills in TMH |

|

Overall, TMH services may greatly address access issues in adolescent mental health, by limiting unnecessary travel, reducing school absences and parental time off from work, bring specialty care to local communities, and improving outcomes by reducing delays in diagnosis and treatment [23]. This is particular relevant, whether the clinician considers that the current digitally native youngsters appear to be more comfortable in seeing the doctor by video and in receiving mental health services by online, as they are accustomed to being connected through the use of electronics, such as social networks, videogames, and interactive VC applications on mobile devices [92,93]. However, the appropriateness of a TMH intervention in Youth Mental Health should be individualized and tailored depending on the developmental stages, patient’s comfortability with the digital tool, parents’ preferences, and the availability of technical supports at the patient site as well as the telepsychiatrists’ resourcefulness and competences in delivering TMH interventions in Youth Mental Health [83,94,95,96,97,98,99,100]. Moreover, as there are no uniform shared regulations regarding TMH interventions, it should be a recommended clinical practice to consult own country’s laws and medical board guidelines and regulations, before initiating a TMH session in Youth Mental Health, particularly regarding the practice of prescribing by means of the Internet (i.e., e-prescribing), the informed consent and the privacy issues. Ideally, the prescriber psychiatrist should conduct at least one face-to-face psychiatric evaluation of the patient before prescribing a psychopharmacological treatment through TMH. Moreover, TMH in Youth Mental Health may largely vary by country’s jurisdiction and needs a proper dedicated protocol, particularly amongst adolescents in at-risk situations and in the treatment provided in foster care and correctional settings [101,102] (Table 3).

Furthermore, TMH services should ensure privacy and data security. In fact, when a clinician decides to offer a TMH session, he/she should understand not only the labeling of encryption, but the publically available information about the encryption process and who could potentially access this information. Whether there are potential safety and privacy risks, the therapist should be encouraged to be transparent with the patient about limitations and pitfalls of technology used. Moreover, TMH protocols most often address the secure transfer of patient written information by fax and/or secure e-mails. Protocols should detail procedures for shared information between institutions for both paper and electronic health records associated with TMH care [96,101,102] (Table 4).

Table 4.

Before starting.

| General knowledge and experience about TMH |

|

| General notions about TMH |

|

| Specific notions about the efficacy and effectiveness of TMH interventions |

|

|

Explanation on

how TMH works |

|

|

Clarification about

recording TMH session |

|

| Establishing a visual context (i.e., setting) of TMH session |

|

| Discussing how to manage occurring technical issues |

|

|

Offering a space

for open questions |

|

| Obtain informed consent |

|

|

Obtain written and signed emergency

shared plan |

|

More in details, psychiatrists should be aware about the need to firstly obtain a specifically designed informed consent for TMH services, e.g., it would ideally better whether the informed consent is distinct and separate from that referring to face-to-face visit. Moreover, families and the child/adolescent should be informed, during the process of obtaining informed consent, about the steps needed and the practice of TMH services, its benefits, and any risks that might be involved at the patient’s site, including occurring privacy and safety issues. In addition, ethical issues should be balanced and communicated to the parents and young patient before commencing TMH services and keep sure that all (including parents/caregiver(s)) give their consents to proceed with TMH services [88,89,90,91,96,102] (Table 4).

Despite the lack of a complete clinical guidance for TMH for each youth mental disorder, there is currently available good telepsychiatry toolkits [89] and the ATA Child and Adolescent TMH Guideline [92,93] which provide a practical guide for apps, asynchronous, e-mail, e-consultation, monitoring, social media, text and wearables useful in the field of young mental health [25]. Furthermore, most psychiatrists and mental health professionals may be resistant in integrating TMH into their practice mainly due to the lack of relevant education, training, clinical experience and exposure to the technology during their training program. Moreover, specific training and education programs in TMH appear to be country-specific and there is a lack of a dedicated program of TMH in Youth Mental Health. Beyond these resistances and difficulties encountering by mental health professionals working with adolescents, another key component of TMH practice should include the need to ensure integrity (i.e., an accurate, honest and truthful clinical and scientific practice of mental health care) during a TMH session which may be missing in some not enough educated contexts [88,89,90,91,96,102].

5. Conclusions

Overall, VC-based or audio call TMH interventions appear to be feasible, preferred and easy to apply for youth mental health in the treatment and monitoring of youth depression, anxiety and OCD. However, it is still needed to shape practice models and tailored modalities, to ensure that the quality of care meets the standards of traditional face-to-face care and guarantees the safety and protection of adolescents and their parents. However, there is the still a need to develop national and regional TMH Resource Centers able to aid, provide training, education and information to organizations and individuals, both in academic, public and private practice settings, who are interested or confident in providing TMH care. Furthermore, TMH programs should be integrated and adequately trained within psychiatric training programs, by deepening multifaceted aspects of Youth Mental Health, including how to provide school-based TMH, TMH in juvenile correctional settings and in daycare centers. Finally, mobile health, sensors, social media, and other TMH services should be ideally integrated into clinical workflow for youth mental health. Further research directions, particularly RCTs, should be specifically addressed to youth mental health and the application of TMH by considering different levels of functioning and maturation of young people, as well as their diagnosis.

Appendix A

Table A1.

MEDLINE search strategy.

| SET | MEDLINE |

|---|---|

| 1 | Telepsychiatry |

| 2 | Telemental Health |

| 3 | Telepsychotherapy |

| 4 | Videoconferencing |

| 5 | Tele * |

| 6 | Remote |

| 7 | Sets 1–6 were combined with “OR” |

| 8 | Youth Mental Health |

| 9 | Depress * |

| 10 | Anxiety |

| 11 | Obsessive Compulsive |

| 12 | Sets 8–11 were combined with “OR” |

| 13 | Telemental health |

| 14 | Telepsychiatry |

| 15 | Adolescent Psychiatry |

| 16 | Sets 13–15 were combined with “OR” |

| 17 | Sets 7, 12 and 16 were combined with “AND” |

| 18 | Set 17 was limited to 25 January 2021 |

| Humans, no language or time restriction |

Words written in italic were used as MeSH headings, the others were used as free text. *, the search strategy chosen in the pubmed.

Appendix B

Figure A1.

PRISMA 2009 Flow Diagram.

Author Contributions

L.O. conceived and conceptualized the topic of the study. L.O. and S.P. performed the data collection, curation and analysis. L.O. and V.S. wrote, revised and draft the final draft. U.V. supervised the work and provided final feedback to the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be constructed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.WHO Sixty-Fourth World Health Assembly. Resolution WHA 64.28: Youth and Health Risks. Geneva, World Health Organization. [(accessed on 15 October 2020)];2011 Available online: https://www.who.int/hac/events/wha_a64_r28_en_youth_and_health_risks.pdf.

- 2.Burns J.M., Davenport T.A., Durkin L.A., Luscombe G.M., Hickie I.B. The internet as a setting for mental health service utilisation by young people. Med. J. Aust. 2010;192:S22–S26. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2010.tb03688.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Howe N., Strauss W. The next 20 years: How customer and workforce attitudes will evolve. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2007;85:41–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shatto B., Erwin K. Moving on from millennials: Preparing for generation, Z. J. Contin Educ Nurs. 2016;47:253–254. doi: 10.3928/00220124-20160518-05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kauer S.D., Mangan C., Sanci L. Do online mental health services improve help-seeking for young people? A systematic review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2014;16:e66. doi: 10.2196/jmir.3103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goldstein F., Glueck D. Developing rapport and therapeutic alliance during telemental health sessions with children and adolescents. J. Child. Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 2016;26:204–211. doi: 10.1089/cap.2015.0022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Myers K., Comer J.S. The case for telemental health for improving the accessibility and quality of children’s mental health services. J. Child. Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 2016;26:186–191. doi: 10.1089/cap.2015.0055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sharma A., Sasser T., Schoenfelder Gonzalez E., Vander Stoep A., Myers K. Implementation of home-based telemental health in a large child psychiatry department during the covid-19 crisis. J. Child. Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 2020;30:404–413. doi: 10.1089/cap.2020.0062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fairchild R.M., Ferng-Kuo S.F., Rahmouni H., Hardesty D. Telehealth increases access to care for children dealing with suicidality, depression, and anxiety in rural emergency departments. Telemed. J. E Health. 2020;26:1353–1362. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2019.0253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hilty D.M., Crawford A., Teshima J., Chan S., Sunderji N., Yellowlees P.M., Kramer G., O’neill P., Fore C., Luo J., et al. A framework for telepsychiatric training and e-health: Competency-based education, evaluation and implications. Int. Rev. Psychiatry. 2015;27:569–592. doi: 10.3109/09540261.2015.1091292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hilty D.M., Chan S., Torous J., Luo J., Boland R. A telehealth framework for mobile health, smartphones and apps: Competencies, training and faculty development. J. Technol. Behav. Sci. 2019;4:106–123. doi: 10.1007/s41347-019-00091-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Loncar-Turukalo T., Zdravevski E., Machado da Silva J., Chouvarda I., Trajkovik V. Literature on wearable technology for connected health: Scoping review of research trends, advances, and barriers. J. Med. Internet Res. 2019;21:e14017. doi: 10.2196/14017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hilty D.M., Zalpuri I., Torous J., Nelson E.L. Child and adolescent asynchronous technology competencies for clinical care and training: Scoping review. Fam. Syst. Health. 2020;39:121–152. doi: 10.1037/fsh0000536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Odgers C.L., Jensen M.R. Annual Research Review: Adolescent mental health in the digital age: Facts, fears, and future directions. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry. 2020;61:336–348. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.13190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sequeira L., Perrotta S., LaGrassa J., Merikangas K., Kreindler D., Kundur D., Courtney D., Szatmari P., Battaglia M., Strauss J. Mobile and wearable technology for mon- itoring depressive symptoms in children and ado- lescents: A scoping review. JAD. 2020;265:314–324. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2019.11.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Russell M.A., Gajos J.M. Annual Research Review: Ecological momentary assessment studies in child psychology and psychiatry. J. Child. Psychol Psychiatry. 2020;61:376–394. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.13204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Siemer C.P., Fogel J., Van Voorhees B.W. Telemental health and web-based applications in children and adolescents. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2011;20:135–153. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2010.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coughtrey A.E., Pistrang N. The effectiveness of telephone-delivered psychological therapies for depression and anxiety: A systematic review. J. Telemed. Telecare. 2018;24:65–74. doi: 10.1177/1357633X16686547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aboujaoude E., Salame W., Naim L. Telemental health: A status update. World Psychiatry. 2015;14:223–230. doi: 10.1002/wps.20218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abuwalla Z., Clark M.D., Burke B., Tannenbaum V., Patel S., Mitacek R., Gladstone T., Van Voorhees B. Long-term telemental health prevention interventions for youth: A rapid review. Internet Interv. 2017;11:20–29. doi: 10.1016/j.invent.2017.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Toscos T., Carpenter M., Drouin M., Roebuck A., Kerrigan C., Mirro M. College students’ experiences with, and willingness to use, different types of telemental health resources: Do gender, depression/anxiety, or stress levels matter? Telemed. J. E Health. 2018;24:998–1005. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2017.0243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gloff N.E., LeNoue S.R., Novins D.K., Myers K. Telemental health for children and adolescents. Int. Rev. Psychiatry. 2015;27:513–524. doi: 10.3109/09540261.2015.1086322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burns J.M., Birrell E., Bismark M., Pirkis J., Davenport T.A., Hickie I.B., Weinberg M.K., Ellis L.A. The role of technology in Australian youth mental health reform. Aust. Health Rev. 2016;40:584–590. doi: 10.1071/AH15115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goldschmidt K. Tele-mental health for children: Using videoconferencing for Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2016;31:742–744. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2016.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.American Telemedicine Association Practice Guideline for Child and Adolescent Telemental Health. Telemedicine Journal and E-Health. [(accessed on 15 November 2020)];2017 Available online: https://www.cdphp.com/-/media/files/providers/behavioral-health/hedis-toolkit-and-bh-guidelines/practice-guidelines-telemental-health.pdf?laen.

- 26.Dwyer T.F. Telepsychiatry: Psychiatric consultation by interactive television. Am. J. Psychiatry. 1973;130:865–869. doi: 10.1176/ajp.130.8.865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marasinghe R.B., Edirippulige S., Kavanagh D., Smith A., Jiffry M.T. Effect of mobile phone-based psychotherapy in suicide prevention: A randomized controlled trial in Sri Lanka. J. Telemed. Telecare. 2012;18:151–155. doi: 10.1258/jtt.2012.SFT107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mackintosh K.A., Chappel S.E., Salmon J., Timperio A., Ball K., Brown H., Macfarlane S., Ridgers N.D. Parental Perspectives of a Wearable Activity Tracker for Children Younger Than 13 Years: Acceptability and Usability Study. JMIR mHealth uHealth. 2019;7:e13858. doi: 10.2196/13858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Khanna M.S., Kendall P.C. Computer-assisted cognitive behavioral therapy for child anxiety: Results of a randomized clinical trial. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2010;78:737–745. doi: 10.1037/a0019739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Spence S.H., Donovan C.L., March S., Gamble A., Anderson R.E., Prosser S., Kenardy J. A randomized controlled trial of online versus clinic-based CBT for adolescent anxiety. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2011;79:629–642. doi: 10.1037/a0024512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Donovan C.L., March S. Online CBT for preschool anxiety disorders: A randomized control trial. Behav. Res. Therapy. 2014;58:24–35. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2014.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morgan A.J., Rapee R.M., Salim A., Goharpey N., Tamir E., McLellan L.F., Bayer J.K. Internet-delivered parenting program for prevention and early intervention of anxiety problems in young children: Randomized controlled trial. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adol. Psychiatry. 2017;56:417–425. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2017.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.March S., Spence S.H., Donovan C.L. The efficacy of an internet-based cognitive-behavioral therapy intervention for child anxiety disorders. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2009;34:474–487. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsn099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spence S.H., Holmes J.M., March S., Lipp O.V. The feasibility and outcome of clinic plus internet delivery of cognitive-behavior therapy for childhood anxiety. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2006;74:614–621. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.3.614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cunningham M.J., Wuthrich V.M., Rapee R.M., Lyneham H.J., Schniering C.A., Hudson J.L. The Cool Teens CD-ROM for anxiety disorders in adolescents: A pilot case series. Eur. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2009;18:125–129. doi: 10.1007/s00787-008-0703-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wuthrich V.M., Rapee R.M., Cunningham M.J., Lyneham H.J., Hudson J.L., Schniering C.A. A randomized cintrolled trial of the Cool Teens CD-ROM computerized program for adolescent anxiety. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2012;51:261–270. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2011.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tillfors M., Andersson G., Ekselius L., Furmark T., Lewenhaupt S., Karlsson A., Carlbring P. A randomized trial of Internet-delivered treatment for social anxiety disorder in high school students. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2011;40:147–157. doi: 10.1080/16506073.2011.555486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]