Abstract

Neu differentiation factors (NDFs), or neuregulins, are epidermal growth factor-like growth factors which bind to two tyrosine kinase receptors, ErbB-3 and ErbB-4. The transcription of several genes is regulated by neuregulins, including genes encoding specific subunits of the acetylcholine receptor at the neuromuscular junction. Here, we have examined the promoter of the acetylcholine receptor ɛ subunit and delineated a minimal CA-rich sequence which mediates transcriptional activation by NDF (NDF-response element [NRE]). Using gel mobility shift analysis with an NRE oligonucleotide, we detected two complexes that are induced by treatment with neuregulin and other growth factors and identified Sp1, a constitutively expressed zinc finger phosphoprotein, as a component of one of these complexes. Phosphatase treatment, two-dimensional gel electrophoresis, and an in-gel kinase assay indicated that Sp1 is phosphorylated by a 60-kDa kinase in response to NDF-induced signals. Moreover, Sp1 seems to act downstream of all members of the ErbB family and thus may funnel the signaling of the ErbB network into the nucleus.

Protein phosphorylation plays an important role in the transfer of the signal from the cell surface into the nucleus (27). Several pathways of signal transduction have been described, including intracellular hormone receptors which are themselves transcription factors; direct interaction between cell surface receptors and transcription factors which, upon modification, translocate to the nucleus; and linear cascades of protein kinases, e.g., the mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) (reviewed in reference 55), that serve as the link between cell surface receptors and nuclear transcription factors. One of the best-characterized families of surface receptors that stimulate transcription through MAPKs is the ErbB family, which consists of four receptors, ErbB-1 [epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)], ErbB-2, ErbB-3, and ErbB-4. Upon ligand binding, these receptors form different combinations of homo- and heterodimers, thereby increasing the diversification potential of signaling and tightly tuning MAPK activation (51). Each ErbB protein consists of a large extracellular ligand-binding domain, a single transmembrane segment, and an intracellular portion containing a tyrosine kinase subdomain and a carboxy-terminal tail region. Multiple ligands exist for ErbB-1, ErbB-3, and ErbB-4, which appear to induce distinct homo- and heterodimers of ErbB proteins. The ligands for ErbB-3 and ErbB-4, Neu differentiation factors (NDFs) or neuregulins, are peptide growth factors which bind to and activate their cognate receptors.

The biological activity of neuregulins, inferred from the phenotypes of knockout mice and cell lines grown in culture (reviewed in reference 11), depicts a role in epithelial cell-mesenchyme and other types of inductive cell-cell interactions. Different isoforms of neuregulins, also called NDF, heregulin, or the acetylcholine receptor (AChR)-inducing activity, were isolated as activities which lead to ErbB-2 tyrosine phosphorylation (26, 48, 65) or to induction of AChR in the neuromuscular synapse (19), respectively. Only later was it established that the isoforms of the neuregulin family of ligands do not bind directly to ErbB-2 but interact with both ErbB-3 and ErbB-4 (58, 62). In situ hybridization analyses indicated that NDF is expressed predominantly in parenchymal organs and in the embryonic central and peripheral nervous systems, in adult brain, and at nerve-muscle synapses (12, 32, 44, 46). Thus, these observations led to the notion that neuregulins control inductive processes through transcriptional regulation of ligands and receptors involved in heterophilic cell-cell interactions (reviewed in reference 6). However, to date only a few genes have been shown to be transcriptionally regulated by NDF: the AChR α, δ, and ɛ subunits genes were demonstrated to be induced two- to threefold by NDF in muscle cells at the nerve-muscle junction both in vivo and in vitro (3, 12, 32, 60). The AChR genes are selectively expressed in muscle fiber nuclei lying beneath the synapse, and NDF is currently a leading candidate to be the motor neuron-derived inducer of AChR expression. Another neuregulin-regulated gene, Krox-20, is a zinc finger transcription factor that is involved in the control of Schwann cell myelination (61). NDF, which regulates the survival and proliferation of rat Schwann cell precursors (17), has been implicated in the induction of Krox-20 expression in Schwann cells during embryogenesis (45). Another gene known to be regulated by signals generated by NDF binding to its receptor is the neurotrophin 3 (NT-3) gene, which encodes a Trk ligand produced by nonneuronal cells immediately surrounding sympathetic ganglia (64).

The Sp1 family of transcription factors includes three members in addition to Sp1 itself: the ubiquitously expressed Sp2 and Sp3 (24, 37), and Sp4, whose expression is limited to the brain (24). Sp1 is a phosphoprotein containing three zinc finger motifs of the Cys-2–His-2 type, which binds with high affinity to GC- or GT-rich promoter elements (29, 30, 53). Several regions of the protein are involved in its functional regulation, including three transactivation domains (14), a DNA binding region, and a carboxy-terminal domain involved in multimerization and cooperative transactivation (22, 47). Sp1 has been demonstrated to act downstream of signaling cascades originating at the cell surface, and its DNA binding, transcriptional activity, and protein-protein interactions are regulated by both phosphorylation and dephosphorylation events (4, 15, 31, 39, 53, 68, 69). Phosphorylation of Sp1 by casein kinase II results in down-regulation of its DNA binding and thus in attenuation of transcription of two genes encoding the D-site binding protein (4, 39) and the glucose-mediated acetyl coenzyme A carboxylase (68). Similarly, induction of the α2(I) collagen gene by the transforming growth factor β involves dephosphorylation of Sp1 (23). In contrast, Sp1 phosphorylation by protein kinase A (PKA) has been demonstrated to augment both its DNA binding and transcriptional activities in HL-60 cells (53). Furthermore, Sp1 is involved in cell cycle regulation, since its activity is modulated by the retinoblastoma protein (36), possibly via direct protein-protein interactions with a member of the retinoblastoma family, p107 (16). Thus, Sp1 is subjected to multiple cell-type-specific modes of regulation, which serve in mediating its role in cell growth and differentiation.

In this study, we show that transcriptional control of NDF target genes is mediated through Sp1 binding to a CA-rich element shared by the respective promoters. Binding of NDF, as well as other EGF-like ligands, to ErbB receptors induces phosphorylation of Sp1 by a putative 60-kDa protein kinase. Subsequently, an Sp1-containing complex is formed on the CA-rich site (which we call the NDF response element [NRE]), and this leads to an increase in transcriptional activity. Apparently, formation of the Sp1-DNA complex at the NRE is not due to modulation of DNA-binding activity per se, and it probably involves higher-order protein-protein interactions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials and antibodies.

EGF was purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, Mo.), and recombinant NDF preparations (EGF-like domains) were from Amgen (Thousand Oaks, Calif.). Radioactive materials were from Amersham (Little Chalfont, United Kingdom). Rabbit and goat anti-Sp1 polyclonal antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnologies. The Sp1 antibody is directed toward amino acids 436 to 454 of Sp1. There is no cross-reactivity with other Sp family members. All other materials were from Sigma, unless otherwise indicated. pCI-Sp1 was the kind gift of Scott L. Friedman (Mount Sinai Medical Center, New York, N.Y.).

Plasmids.

The rat AChR ɛ subunit gene promoter fragment (−228 to +27) was cloned as a BamHI-HindIII fragment from the pɛ-228/CAT plasmid (18) into the BglII-HindIII sites of pSEAP-basic (Clontech Laboratories, Inc.). To construct p(NRE)3E1b-LUC, a double-stranded NRE oligonucleotide (top strand, 5′-TCGACTGCCACCCCCACCCCCACATCACC-3′) was phosphorylated with T4 kinase and then cloned into the XhoI site of pE1b-LUC (1). The annealed oligonucleotide was designed to carry a SalI site at the 5′ end and an XhoI site at the 3′ end. Automated dideoxynucleotide sequencing established that the phagemid contained three copies of the NRE oligonucleotide, all in the same orientation. pGEX-Sp1, a plasmid directing bacterial expression of a fusion between Sp1 and gluthatione S-transferase (GST), was constructed by cloning an EcoRI (this end was filled in with Klenow enzyme)-SmaI fragment from pCI-Sp1 into the EcoRI (blunt ended by Klenow enzyme) site of pGEX-3X (Pharmacia).

Cell transfection and reporter gene assays.

P-19 teratocarcinoma cells were transfected by the calcium phosphate precipitation method. The cells were seeded 24 h prior to transfection at 2 × 105 cells/60-mm dish in growth medium (alpha minimal essential medium [MEM] supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum [FCS]) and refed with Dulbecco MEM plus 10% FCS 3 h before transfection. The cells were transfected in triplicate with 8 μg of reporter plasmid [pɛ-228/SEAP or p(NRE)3E1b-LUC] and 2 μg of pCMV-βGal as an internal control for transfection efficiency. They were kept in transfection medium for 14 to 16 h and then washed and refed with growth medium. At 10 h later, the cells were treated with NDFβ (100 ng/ml) in growth medium, or left untreated for 12 h, and then harvested for luciferase or β-galactosidase assays. Alternatively, an aliquot of the growth medium was removed and assayed for placental alkaline phosphatase activity. Secreted alkaline phosphatase (SEAP) activity was assayed as described by the manufacturer (Clontech Laboratories, Inc.). In short, 12 h after ligand addition, an aliquot (110 μl) of the medium was removed and centrifuged to remove cell debris. The resulting supernatant was mixed (1:3) with SEAP dilution buffer and incubated for 30 min at 65°C. Assay buffer and chemiluminescent substrate were added, and the mixture was incubated for 20 minutes at room temperature. SEAP activity was measured in a tube luminometer (Turner). Luciferase and β-galactosidase assays were performed from cells that were scraped in phosphate-buffered saline and divided between two tubes. For the β-galactosidase assay, cells were centrifuged and resuspended in 50 μl of 0.25 M Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) and extracts were prepared by six freeze-thaw cycles. The cellular debris were removed by centrifugation, and an aliquot of the supernatant was assayed for β-galactosidase activity in sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5) containing 1 mM MgCl2, 45 mM β-mercaptoethanol, and 0.88 μg of ONPG (o-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside) per ml. Extracts for luciferase assays were prepared by resuspending the cells in 30 μl of lysis buffer (Promega). Following a 10-min incubation at room temperature, the cellular debris were removed and an aliquot of the resulting supernatant was mixed with 100 μl of luciferin buffer (0.1 M Tris-acetic acid, 10 mM magnesium acetate, 1 mM EDTA [pH 8.0], 74 mM luciferin, 2.2 mM ATP). The light intensity was measured with a luminometer. To exclude variation due to differences in transfection efficiency, the activities of the reporters luciferase and SEAP were normalized to the levels of the internal β-galactosidase control at each point.

Preparation of extracts from whole cells and nuclei.

Whole-cell extracts were prepared from cultures grown in 10-cm dishes. Cell monolayers were washed twice and scraped in 1 ml of phosphate-buffered saline containing 2 mM sodium orthovanadate, 10 mM sodium fluoride, 0.5 μg of leupeptin per ml, 2 μg of aprotinin per ml, 0.5 μg of pepstatin A per ml, and 0.5 mM benzamidine and transferred to microcentrifuge tubes. After a 10-s centrifugation at 12,000 × g, the cells were resuspended in 0.3 ml of buffer A (10 mM HEPES-KOH [pH 7.9], 1.5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM KCl, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol [DTT], 0.2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride [PMSF], 20 mM β-glycerophosphate, 10 mM p-nitrophenyl phosphate, 400 nM okadaic acid), incubated on ice for 10 min, vortexed for 10 s, and centrifuged for 10 s as above. The crude cellular extract was resuspended in 30 μl of buffer C (20 mM HEPES-KOH [pH 7.9], 25% glycerol, 420 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM EDTA [pH 8.0], 0.5 mM DTT, 0.2 mM PMSF, 20 mM β-glycerophosphate, 10 mM p-nitrophenyl phosphate, 400 nM okadaic acid) incubated on ice for 20 min, and centrifuged (14,000 × g for 2 min) at 4°C. The protein concentration was determined by using the Bradford reagent (Bio-Rad Laboratories). Aliquots (5 μl) of whole-cell extracts were snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −70°C. Nuclear extracts were prepared from cell cultures grown in 150-mm dishes. The cell monolayers were washed twice with an ice-cold wash buffer (2.7 mM KCl, 1.5 mM KH2PO4, 136 mM NaCl, 8.1 mM Na2HPO4 · 7H2O) and once with buffer A-NE (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.8], 15 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.2 mM PMSF, 2 μg of leupeptin per ml, 0.1 mg of aprotinin per ml, 30 mM β-glycerophosphate, 400 nM okadaic acid, 2 mM sodium orthovanadate). The cells were scraped into 2 ml of buffer A-NE and centrifuged. The cell pellets were lysed in 1 ml of buffer B (buffer A-NE containing 0.2% Nonidet P-40), pipetted vigorously 10 times, and immediately centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 2 min to pellet the nuclei. A concentrated (10×) cytoplasm extraction buffer (0.3 M HEPES-KOH [pH 7.9], 1.4 M KCl, 0.03 M MgCl2) was added to the supernatant, the mixture was centrifuged for 10 min at 100,000 × g, and the resulting cytoplasmic extract was snap frozen in liquid nitrogen. The pelleted nuclei were resuspended in 315 μl of buffer C-NE (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.8], 50 mM KCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 0.1 M PMSF, 10% glycerol, 30 mM β-glycerophosphate, 400 nM okadaic acid, 2 mM sodium orthovanadate), 35 μl of 3 M ammonium sulfate (pH 7.9) was added, and the mixture was inverted gently for 30 min at 4°C. Following a 15-minute centrifugation step (200,000 × g at 4°C), an equal volume of 3 M ammonium sulfate was added to the supernatant, and nuclear proteins were pelleted at 100,000 × g for 10 min. The pelleted proteins were resuspended in 50 μl of buffer C-NE for an in-gel kinase assay and snap frozen in liquid nitrogen. Alternatively, resuspension was performed in a mixture (1:4) of sample buffer I (0.3% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], 200 mM DTT, 28 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.0], 22 mM Tris base) and sample buffer II (9.9 M urea, 4% Nonidet P-40, 2.2% ampholytes, 100 mM DTT) for two-dimensional gel electrophoresis. Protein concentrations were determined with the Bradford reagent.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA).

Whole-cell extracts (5 to 10 μg) prepared from untreated cells or cells treated for the indicated time intervals with NDF or EGF (each at 100 ng/ml) were incubated for 20 min (at room temperature) with 0.1 ng (20,000 cpm) of double-stranded, end-labeled NRE oligonucleotide probe. The incubation mixture also contained 250 ng of sheared salmon sperm DNA per ml and binding buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 25 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM EDTA, 0.1 mg of bovine serum albumin per ml [BSA], 5 mM DTT, 10% glycerol). Protein-DNA complexes were resolved by electrophoresis on 4% nondenaturing acrylamide gels as described previously (51). For control of extract activity and quantity, sister reactions were performed with a double-stranded oligonucleotide (top strand, 5′-TTTTGGATTGAAGCCAATTATGATAA) of the NF-Y binding basal transcription factor. For analysis of the on-rate, extracts were incubated in binding buffer without labeled probe and aliquots of 9 μl (containing 2.5 μg of protein of whole-cell extract) were mixed with NRE probe (104 cpm) and incubated for the specified time. At the end of the incubation samples were loaded on a running mobility shift gel.

Treatment with alkaline phosphatase.

Whole-cell extracts (5 μg) were equilibrated for 5 min at room temperature in dephosphorylation buffer (25 mM HEPES-KOH [pH 7.9], 34 mM KCl, 50 mM MgCl2). Alkaline phosphatase (0.1 U; Boehringer Mannheim) was added on ice, and the mixture was incubated for 15 min. The reaction was stopped by the addition of an equal volume of inhibitor mixture (20 mM NaF, 20 mM sodium vanadate, 20 mM potassium pyrophosphate, 200 μg of BSA per ml, 0.02% Nonidet P-40, 20% glycerol, 5 mM DTT, 250 ng of sheared salmon sperm DNA per ml), and then the NRE probe (20,000 cpm) was added. Incubation was continued for 20 min at room temperature, and protein-DNA complexes were separated as described above. As a control for the different binding buffers, the inhibitor mixture was added before incubation with the alkaline phosphatase.

Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis.

Isoelectric focusing of P-19 nuclear extracts (5 μg) was carried out as specified by the manufacturer (Bio-Rad) with vertical tube gels and equal volumes of two ampholytes (pH 3 to 10 and pH 8 to 10 [Bio-Rad]). The second dimension consisted of SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) in a 10% polyacrylamide gel. Separated proteins were electroblotted onto nitrocellulose filters, and the Sp1 protein detected with Sp1-specific antibodies (see below) followed by horseradish peroxidase-linked protein A. The complexes were detected with chemiluminescence reagents as specified by the manufacturer (Amersham).

Western and Southwestern blots.

Samples of a P-19 nuclear extract (in triplicate, 60 μg each) were separated by gel electrophoresis (8% acrylamide) under reducing conditions and transferred to nitrocellulose filters. The filter was cut to allow each set of samples to be probed with either antibody or a radiolabeled probe. For Western analysis, the blot was washed once in TBST buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 150 mM NaCl, 0.05% Tween 20) and blocked for 1 h at room temperature in TBST buffer containing 5% milk. The blot was subsequently incubated with the Sp1-specific antibody (1 μg/ml) in TBST buffer containing 5% milk. For Southwestern analysis, the membranes were washed twice with renaturing buffer (20 mM HEPES-KOH [pH 7.9], 3 mM MgCl2, 40 mM KCl, 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 80 μM ZnSO4) and subsequently blocked for 1 h with 20 mM HEPES-KOH (pH 7.9) containing 4% milk. The membranes were equilibrated in Southwestern binding buffer (10 mM HEPES-KOH [pH 7.9], 70 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, 0.3 mM MgCl2, 0.1% Triton X-100, 60 μg of BSA per ml, 37.5 μg of sheared salmon sperm DNA per ml) and NRE probe (double-stranded oligonucleotide labeled with Klenow fragment and [α-32P]ATP) was added for a 3-h incubation at room temperature. As a control, twofold excess cold NRE in binding buffer was incubated for 1 h prior to probe addition. Finally, the membranes were washed twice for 5 min at room temperature with binding buffer containing 0.01% Triton X-100 and autoradiographed.

In-gel kinase assay.

Nuclear extracts were separated on a 10% polyacrylamide gel containing 0.2 mg of GST-Sp1 or GST protein alone as control per ml. GST fusion proteins were affinity purified over a column of glutathione-agarose. The gels were washed in 50 mM HEPES-NaOH (pH 7.5) containing 20% isopropanol and denatured by two washes in buffer I (50 mM HEPES [pH 7.5], 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol) and two washes in buffer I containing 50 mM urea. Stepwise renaturation was performed with buffer I containing 0.02% Tween 20, with a final overnight wash in the same buffer. Kinase reactions were performed in kinase buffer (20 mM HEPES-NaOH [pH 7.5], 20 mM MgCl2, 2 mM DTT, 20 μM ATP, 5 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP per ml) for 2 h at 30°C, and the gels were washed several times with a mixture containing 5% trichloroacetic acid and 1% sodium pyrophosphate, dried, and autoradiographed.

Metabolic labeling with [32P]orthophosphate and immunoprecipitation.

P-19 cells were grown in 10-cm plates to 70 to 80% confluence. The cells were washed three times and incubated for 2 h in phosphate-free Dulbecco MEM (Sigma) containing 5% dialyzed FCS. The medium was then changed to phosphate-free medium containing 0.5 mCi of [32P]orthophosphate (Amersham) per ml. At 4 h later, the cells were treated for 30 min with NDFβ (100 ng/ml) or left untreated. All subsequent steps were carried out on ice with ice-cold buffers. The cells were washed three times with phosphate wash buffer, scraped into 500 μl of RIPA buffer (50 mM HEPES-KOH, [pH 7.9], 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA [pH 8.0], 10% glycerol, 0.1% SDS, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 50 mM β-glycerophosphate, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 10 mM NaF, 400 nM okadaic acid, 10 mM K2HPO4, 1 mM PMSF, 1 μg each of aprotinin, leupeptin, and pepstatin per ml), and incubated for 20 min on ice. Following a 20-min centrifugation at 14,000 × g, the supernatant was transferred to a fresh microcentrifuge tube and the extract was precleared with 25 μl of protein A-Sepharose for 30 min with vigorous shaking. The beads were pelleted (12,000 × g for 2 min), the supernatant was transferred to a new tube, and 25 μl of protein A-Sepharose beads conjugated to Sp1- or Egr1-specific antibodies (rabbit polyclonal antibodies; Santa Cruz) was added. Immunoprecipitation was performed for 2 h at 4°C with vigorous shaking, after which the immunoprecipitated proteins were washed five times with RIPA buffer. At the last wash, the beads were transferred to a new tube, resuspended in 30 μl of 2× protein-sample buffer (120 mM Tris-HCl [pH 6.8], 10% glycerol, 3% SDS, 20 mM DTT, 0.4% bromophenol blue), and boiled for 5 min. The samples were separated by SDS-PAGE (7.5% acrylamide), transferred to nitrocellulose and autoradiographed. Later, the membranes were blocked and Western blotted as described above, except that the anti-Sp1 antibody was of goat origin (Santa Cruz) and the secondary antibody used was an anti-goat horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibody (Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories, Inc.).

RESULTS

Identification of an NDF-regulated DNA sequence in the promoters of genes encoding AChR δ and ɛ subunits and NT-3.

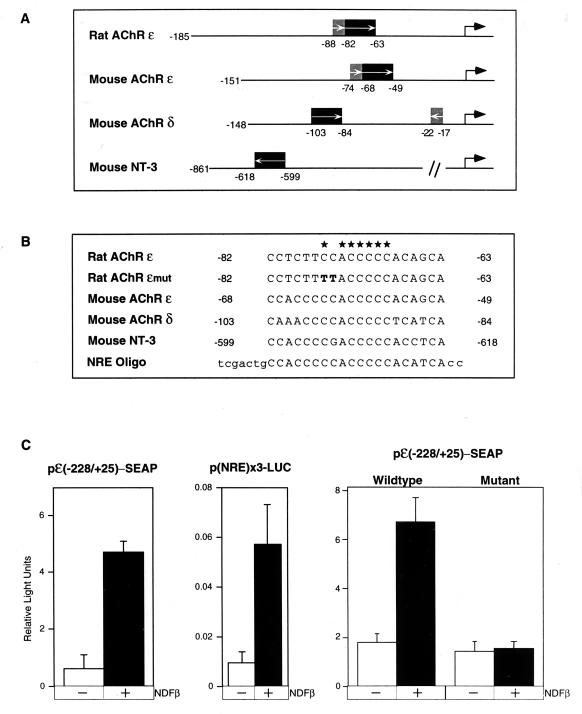

To identify an NDF-regulated sequence element, we compared the structures (Fig. 1A) and nucleotide sequences (Fig. 1B) of the promoters of the four genes known to be transcriptionally activated by NDF; these are the genes encoding the rat and murine ɛ subunits and the murine δ subunit of the AChR (5, 12, 32, 60), and NT-3 (64). The promoters of both the δ and ɛ subunits contain a region sufficient for muscle-specific and NDF-specific regulation (12, 32). Moreover, it has been demonstrated that an E box (Fig. 1A) in the AChR ɛ subunit gene is important for muscle-specific transcription whereas it is dispensable for induction by NDF (12). Regulation of the AChR ɛ subunit gene provides a particularly useful model for transsynaptic induction, since it is the only subunit that exhibits strict spatial regulation; the α, β, γ, and δ subunits are regulated by mechanisms that also allow expression outside the synaptic region under certain conditions. We identified a common 20-bp sequence in the enhancers of the AChR δ and ɛ subunits and in the upstream region of the NT-3 gene and hypothesized that this sequence element is important for the observed NDF-mediated induction of gene expression. To test this prediction, we placed the full promoter sequence (228 bp) of the rat AChR ɛ subunit (18) upstream of a reporter plasmid, construct pɛ(−228/+25)-SEAP. Another reporter plasmid, containing three copies of the suspected 20-bp sequence placed upstream of a luciferase gene [plasmid construct p(NRE)×3-LUC] was also constructed. P-19 teratocarcinoma cells were separately transfected in triplicate with the two reporter plasmids, as well as with a β-galactosidase plasmid, which served as an internal control for all transfection assays. As predicted, stimulation of the transfected P-19 cells with NDFβ resulted in significant induction of both reporter genes (Fig. 1C): in the context of the full-length promoter-enhancer, pɛ(−228/+25)-SEAP, NDF was able to elevate SEAP activity two- to fourfold (Fig. 1C, left). Moreover, the shared 20-bp sequence was sufficient to mediate the effect of NDF on luciferase expression (Fig. 1C, center).

FIG. 1.

Mapping of the NRE in the promoter of the AChR ɛ gene. (A) Minimal promoter regions needed for muscle-specific expression of the rat AChR ɛ gene (nucleotides −185 to +25), the mouse AChR ɛ gene (−151 to +84), and the mouse AChR δ gene (−148 to +24), as well as the region in the promoter of the NT-3 gene encompassing the putative NRE. The E-box element, which confers muscle-specific expression, is indicated by a shaded box, and the region that confers responsiveness to neuregulin is indicated by a solid box; arrows within the boxes denote the orientation of this element. The mRNA start sites are indicated by large arrows. (B) Sequence comparison of the CA-rich elements found in the promoters of the NDF-inducible genes (asterisks indicate bases that are strictly conserved). Also shown is the sequence of an oligonucleotide (NRE Oligo) that we used to construct a reporter plasmid and perform the EMSA. A mutation we introduced in the rat AChR ɛ reporter is also listed (Rat AChR ɛmut). (C) NDF-induced transcriptional activation through NRE. The following constructs were used to assay transcriptional activation of reporter genes (to cotransfect P-19 cells together with a β-galactosidase reporter as an internal control): a minimal promoter of the rat AChR ɛ gene fused to the SEAP gene [pɛ(−228/+25)-SEAP], three copies of the NRE oligonucleotide cloned upstream of a luciferase reporter gene [p(NRE)×3-LUC], and two versions, a wild-type and a mutant form (Rat AChR ɛmut [B]), of pɛ(−228/+25)-SEAP. At 24 h posttransfection, cells were untreated (−) or treated (+) with NDFβ (100 ng/ml). At 16 h later, the cells were harvested for luciferase and β-galactosidase assays, or their medium was assayed for SEAP activity. Signals obtained with the reporter genes were normalized to β-galactosidase activity.

To further establish the function of this element as an NDF-responsive site, two of its conserved cytosines were mutated to thymidines (Fig. 1B, Rat AChR ɛmut) in the context of the full-length AChR ɛ promoter. The mutated reporter construct was used in parallel transfection experiments with the wild-type reporter construct (Fig. 1C, right). The results of these experiments indicated that the mutated AChR ɛ reporter either was completely unresponsive to induction by NDF (Fig. 1C, right) or retained very low activity (data not shown), thus establishing the short sequence as an essential part of an NRE.

Identification of NRE-binding complexes whose activation is induced by several ligands.

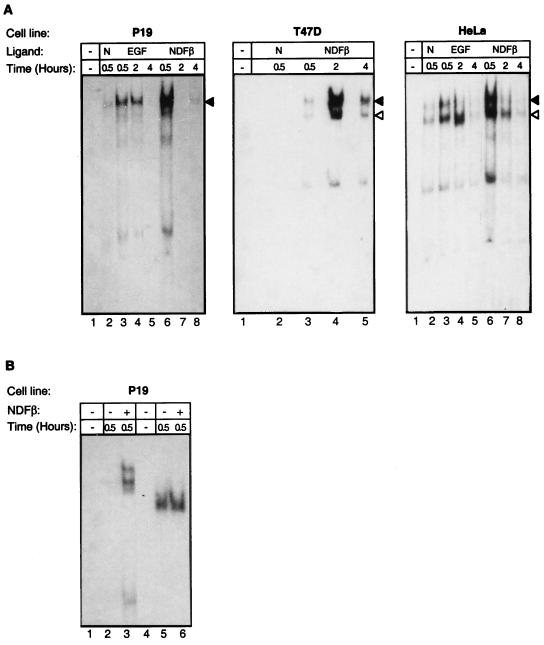

EMSA was used to study the NDF-mediated induction of protein-DNA complexes on the NRE. Whole-cell extracts were prepared from different cell types, after treatment for various time intervals with NDF, and incubated with a radiolabeled NRE oligonucleotide (Fig. 1B). As a control for equal gel loading, we used a NF-Y oligonucleotide as a probe for the NF-Y binding nuclear factor (Fig. 2B lanes 4 to 6). Two DNA-protein complexes were detected following a 30-min treatment with NDF in several cell lines (Fig. 2): P-19 teratocarcinoma cells (expressing ErbB-1, ErbB-2, and ErbB-3), T47D breast tumor cells (expressing all four ErbBs), and HeLa human cervical carcinoma cells (expressing ErbB-1 and ErbB-4), and others (data not shown). The kinetics of induction of NRE binding activity differed; in both P-19 and HeLa cells, maximal induction was observed at 30 min after NDF addition, whereas in T47D cells, maximal induction was seen only after 2 h, but it persisted longer. Furthermore, the intensity of the faster-migrating complex (Fig. 2A) differed among the cell lines we tested; its induction was relatively weak in P-19 cells whereas the intensities of the two bands were comparable in T47D and HeLa cells. In conclusion, the induction of NRE binding complexes by NDF appeared rapid, specific, and cell type independent and thus may serve to regulate the transcription of other genes by NDF.

FIG. 2.

NDFβ and EGF induce the formation of two NRE binding complexes. (A) An oligonucleotide duplex (top strand sequence, 5′-TCGACTGCCACCCCCACCCCCACATCACC-3′) was used as a probe and incubated without (−) or with 5 μg of whole-cell extract prepared from P-19, T47D, or HeLa cells. The cells were untreated (N) or treated for the indicated time intervals with NDFβ or EGF, as indicated, and NRE binding was assayed by EMSA. Arrowheads indicate the positions of the two protein-DNA complexes. Note that the complex whose mobility is greater (open arrowhead) is absent in P-19 cells. (B) Whole-cell extracts prepared from NDF-treated or untreated P-19 cells were used for EMSA with the NRE oligonucleotide (lanes 1 to 3) or with the NF-Y oligonucleotide probe as a control (lanes 4 to 6). Note the absence of an NDF effect on NF-Y.

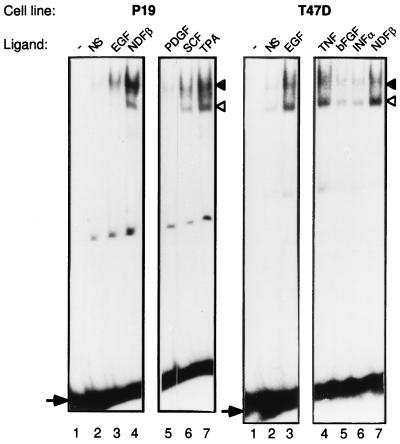

Similar to NDF, which binds to both ErbB-3 and ErbB-4, EGF, a ligand for ErbB-1, was able to induce a similar pattern of DNA-protein complexes (Fig. 2). However, the induction of complex formation was weaker than with NDF. EGF was thus used in transfection assays with the pɛ(−228/+25)-SEAP reporter to test its ability to induce transcription. We found that the induction of SEAP activity by EGF was very low (data not shown), which may reflect the significantly lower induction of DNA binding as measured by EMSA. To extend this observation to additional growth factors, P-19 and T47D cells were treated for 30 min with several other ligands. The stem cell factor (SCF/c-Kit ligand) and the tumor-promoting phorbol ester tetradecanoyl phorbol acetate (TPA) were able to induce the formation of the two DNA binding complexes in P-19 cells. The effect of SCF was much lower than that of TPA, and an SCF-related factor, platelet-derived growth factor, was inactive in this cell system. In addition, unlike NDF, which induced primarily the slow-migrating complex, both DNA-protein complexes were induced to a similar extent by SCF and TPA and a third, intermediate, band was also detectable upon treatment with these two factors (Fig. 3). In T47D cells, both EGF and tumor necrosis factor were able to induce the NRE-specific DNA-protein complex to a level similar to that induced by NDF whereas the basic fibroblast growth factor and alpha interferon exerted no effect (Fig. 3). Thus, induction of NRE binding activity is shared by several but not all of the growth factors tested. However, the levels and relative inductions of the two complexes varied.

FIG. 3.

Growth factor induction of protein-DNA complexes on the NRE probe. P-19 (left) or T47D (right) cells were treated for 30 min with the indicated growth factors or for 2 h with TPA, and whole-cell extracts were prepared. Extracts were incubated with a labeled NRE probe, and protein-DNA complexes were separated on a nondenaturing polyacrylamide gel. The arrows denote the positions of the free oligonucleotide probe, and the arrowheads denote the positions of protein-DNA complexes (a slow-migrating complex [closed arrowhead] and a fast-migrating complex [open arrowhead]). Abbreviations: NS, nonstimulated; PDGF, platelet-derived growth factor; SCF, stem cell factor; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; bFGF, basic fibroblast growth factor; INFα, alpha interferon.

The DNA-binding protein that is activated by NDFβ is the transcription factor Sp1.

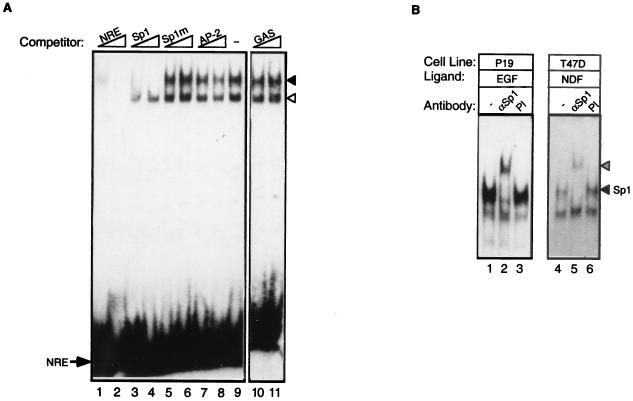

NDFβ induces transcriptional activation from the NRE site, as well as complex formation on this DNA sequence. To identify the factor(s) that binds to this site, we made use of unlabeled competitor oligonucleotides carrying consensus cytosine-rich binding elements for several known transcription factors. T47D cells were selected for this assay since in these cells the two complexes were comparably induced by NDF (Fig. 2 and 3). Whole-cell extracts of T47D cells were incubated with 100- and 500-fold molar excesses of various unlabeled competitor oligonucleotides, and NRE binding activity was tested by EMSA (Fig. 4A). Since EGF treatment of A-431 cells results in the phosphorylation and subsequent nuclear localization of the STAT-1 transcription factor, which enables it to bind to the cognate response element, the gamma interferon activation site (56), we tested the gamma interferon activation site oligonucleotide. However, this DNA element was unable to displace the NDF-induced complexes formed on the NRE oligonucleotide (Fig. 4A, lanes 10 and 11). Similarly, the AP-2 response element, a CA-rich sequence specific for the AP-2 family of transcription factors (66), chased neither protein-DNA complex (compare lanes 7 and 8 with lane 9). However, a consensus Sp1 element, a GC-rich sequence (41), specifically bound to the slower-migrating complex (compare lanes 3 and 4 with lane 9). In fact, the Sp1 consensus oligonucleotide more efficiently abolished the formation of the slower-migrating complex than did an unlabeled NRE probe (compare lanes 1 and 2 with lanes 3 and 4) (data not shown), indicating that the NRE-bound complex interacts more tightly with the consensus Sp1 sequence. A mutated Sp1 oligonucleotide, carrying a point mutation which abolishes binding by Sp1 (41), was unable to compete for the slower-migrating complex (lanes 5 and 6). Thus, the slower-migrating complex probably consists of Sp1 or another member of the Sp1 family that shares DNA binding specificity. To identify the specific member, we tried to retard the electrophoretic mobility of the NRE-protein complex with an Sp1-specific antibody. The antibody we used is directed against a region of Sp1, which differs between the Sp family members. Supershift analysis performed with whole extracts of P-19 and T47D cells indicated that the NRE-bound protein is indeed Sp1 (Fig. 4B): the antibody was specifically able to shift the upper band. A control preimmune serum or an Sp3-specific antibody displayed no effect when similarly tested (Fig. 4B, lanes 3 and 6) (data not shown). Since a reporter construct carrying a mutation in the NRE was not inducible by NDF in transfection assays, and the basal transcription activity was not compromised (Fig. 1C), we concluded that Sp1 is essential for AChR ɛ induction by NDF but not for basal promoter activity.

FIG. 4.

Identification of factors interacting with the NRE. (A) Competition between NRE and consensus oligonucleotides. Whole-cell extracts were prepared from NDFβ-treated T47D cells and incubated with the NRE probe in the absence (−) or presence of the indicated unlabeled competitor oligonucleotides at either 100-fold excess (lanes 1, 3, 5, 7, and 10) or 500-fold excess (lanes 2, 4, 6, 8, and 11). An arrow denotes the position of the free NRE probe, and arrowheads denote the positions of the two protein-DNA complexes (the solid arrowhead indicates the slower-migrating complex). (B) The slower-migrating protein-DNA complex is supershifted with an Sp1-specific antibody. Whole-cell extracts prepared from EGF-treated P-19 cells or NDF-treated T47D cells were preincubated with an Sp1-specific antibody (αSp1). As a control, extracts were treated with a preimmune serum (PI) or with no antibody (−). A labeled NRE probe was then added, and protein-DNA complexes were separated on nondenaturing polyacrylamide gels. The positions of the Sp1-specific complex (solid arrowhead) and the supershifted complex (hatched arrowhead) are marked. Note that the lower NRE complex underwent no supershift.

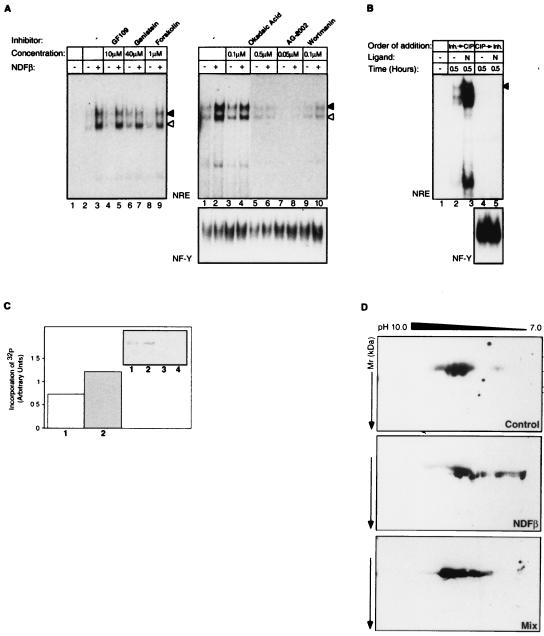

NDF-mediated induction of complex formation on the NRE is dependent on protein phosphorylation.

Regulation of transcription factor activity can result from induction of de novo protein synthesis or from modification, primarily phosphorylation (27), of an existing protein. Because Sp1 is a heavily phosphorylated phosphoprotein which is ubiquitously expressed in all cell lines and tissues (34), we postulated that the induction of Sp1 binding activity is due to protein phosphorylation or dephosphorylation events. Cell treatment with a general inhibitor of tyrosine kinases, genistein (49), abolished NDF induction of the slower-migrating complex while leaving unaffected the activation of the faster-migrating species (Fig. 5A [left], compare lanes 6 and 7 with lanes 2 and 3). By contrast, an inhibitor specific to ErbB tyrosine kinases, tyrphostin AG-2002 (21), inhibited the induction of both protein-DNA complexes (Fig. 5A [right], lanes 7 and 8). An inhibitor of PKC, GF109203X, an activator of the protein kinase A signaling pathway, and forskolin had no effect on complex formation. Wortmannin, a phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase inhibitor, lowered both basal and NDF-induced levels of the mobility shifts. However, the induction by NDF was still detectable. By contrast, treatment with okadaic acid, a potent inhibitor of protein phosphatases (13), strongly inhibited the induction of both NRE-protein complexes as determined by EMSA (Fig. 5A [right], compare lanes 3 through 6 with lanes 1 and 2). The inhibitory concentration of okadaic acid (0.5 μM) (Fig. 5A, left) can specifically inhibit protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A), implying that PP2A acts as a positive regulator of signaling upstream of Sp1 activation by NDF.

FIG. 5.

Phosphorylation events are important for the regulation of Sp1 binding to the NRE site. (A) Effects of kinase and phosphatase inhibitors on NRE binding activity in NDFβ-treated T47D cells. Prior to EMSA with an NRE probe, the cells were preincubated for 20 min with the inhibitors GF109203X (GF109, a protein kinase C-specific inhibitor), genistein (a general inhibitor of tyrosine kinases), forskolin (an inhibitor of cyclic AMP phosphodiesterases), okadaic acid (OA, an inhibitor of protein phosphatase 2A), AG2002 (an inhibitor of the ErbB tyrosine kinase activity), and wortmannin (a phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase inhibitor) and then treated with NDF. Control cultures were not treated with an inhibitor. The positions of the two protein-DNA complexes are denoted by arrowheads (closed arrowhead, Sp1-specific complex; open arrowhead, faster-migrating complex). As a control, EMSA was performed with the NF-Y probe (lower panel). (B) Inhibition of Sp1 DNA binding by in vitro treatment with CIP. The NRE (upper panel) and NF-Y (lower panel) probes were incubated with 5 μg of extracts prepared from P-19 cells that were incubated for the indicated time intervals with NDFβ (N). Control cultures were not treated with a growth factor (−). Prior to EMSA, extracts were incubated with CIP and then the phosphatase was inhibited by addition of specific inhibitors (a mixture of NaF, sodium vanadate, and potassium pyrophosphate [lanes 4 and 5]). Alternatively, the inhibitors were added prior to treatment with CIP (lanes 2 and 3). The position of the Sp1-specific complex is indicated by an arrowhead. (C) Sp1 is a phosphoprotein whose phosphorylation is increased by NDF. P-19 cells were preincubated with a medium containing [32P]orthophosphate and then treated (lanes 1 and 3) or not treated (lanes 2 and 4) with NDF. Whole-cell extracts were prepared and incubated with an anti-Sp1 antiserum (lanes 1 and 2) or an anti-Egr1 antibody (lanes 3 and 4). The immunoprecipitates were resolved by SDS-PAGE and electrophoretically transferred to a nitrocellulose filter. The filter was subjected to autoradiography (inset) and then immunoblotted with an antibody to Sp1 (data not shown). Both signals were quantified, and their ratio is presented in a histogram. Numbers below the bars correspond to gel lanes. (D) Analysis of NDF-induced phosphorylation of Sp1 by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis. Nuclear extracts (5 μg of protein) were prepared from untreated (Control), or P-19 cells treated with 100 ng of NDFβ per ml. As a control, a mixture of the two nuclear extracts (2.5 μg each) was analyzed (MIX). Extracts were separated by isoelectric focusing in the first dimension (pH values are indicated) and by SDS-PAGE in the second dimension (the locations of marker proteins are indicated in kilodaltons). The proteins were then transferred to nitrocellulose filters, and the Sp1 protein was detected by immunoblotting with an anti-Sp1 antibody.

We next examined the possibility that the NRE-bound complex is phosphorylated and that this protein phosphorylation is essential for DNA binding. To test this paradigm, we treated whole-cell extracts, which were prepared from growth factor-treated cells, with a nonspecific phosphatase (calf intestinal phosphatase, CIP) and then determined how this affected the EMSA pattern. As a control for the difference in buffer conditions, extracts were treated with CIP in the presence of specific inhibitors. In addition, as a specificity control CIP-treated extracts were incubated with the NF-Y response element. The result of these analyses indicated that protein dephosphorylation inhibited the binding of both Sp1 and the faster-migrating complex (Fig. 5B, compare lanes 3 and 5). CIP treatment did not compromise the DNA binding activity of the extract in a nonspecific manner, since binding to the NF-Y probe could still be detected (Fig. 5B, bottom).

To determine if NDF induces an increase in Sp1 phosphorylation in living cells, we incubated P-19 cells with radioactive orthophosphate, stimulated the cells with NDF, and then determined the state of Sp1 phosphorylation. Sp1 was immunoprecipitated from labeled cells, subjected to SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, and autoradiographed. As expected, Sp1 was phosphorylated in unstimulated cells (Fig. 5C, inset, lane 1), but incubation with NDF for 30 min moderately increased its phosphorylation (lane 2). By contrast, the state of phosphorylation of another zinc finger-containing transcription factor, Egr-1, was not affected by NDF. Reblotting of the nitrocellulose filter with an anti-Sp1 antibody enabled precise quantification of Sp1 phosphorylation: a 50 to 60% increase in Sp1 phosphorylation was determined. This moderate increase is probably due to the relatively high basal phosphorylation of Sp1. Therefore, NDF-induced phosphorylation was tested by an alternative approach, two-dimensional gel electrophoresis, which examines the change in isoelectric point due to phosphorylation. Nuclear extracts were prepared from untreated and NDF-treated P-19 cells and resolved by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis, which separates proteins according to their isoelectric point in the first dimension and by their size in the second dimension. Gel-separated proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose filters and immunoblotted with an Sp1-specific antibody. This analysis revealed that several isoforms of Sp1 exist in unstimulated cells, but NDF can induce broadening of their pI range toward the acidic pole (Fig. 5D), consistent with the addition of phosphate groups. Electrophoresis of a mixture of extracts from treated and untreated cells confirmed the effect of NDF (Fig. 5D, bottom). We estimate that approximately half of the Sp1 molecules are modified upon NDF treatment. In addition, the appearance of the modified Sp1 suggested that more than one phosphate group is attached to these hyperphosphorylated Sp1 molecules. In experiments whose results are not presented, we detected no tyrosine phosphorylation of Sp1, indicating that modification of this serine- and threonine-rich protein does not affect its few tyrosine residues.

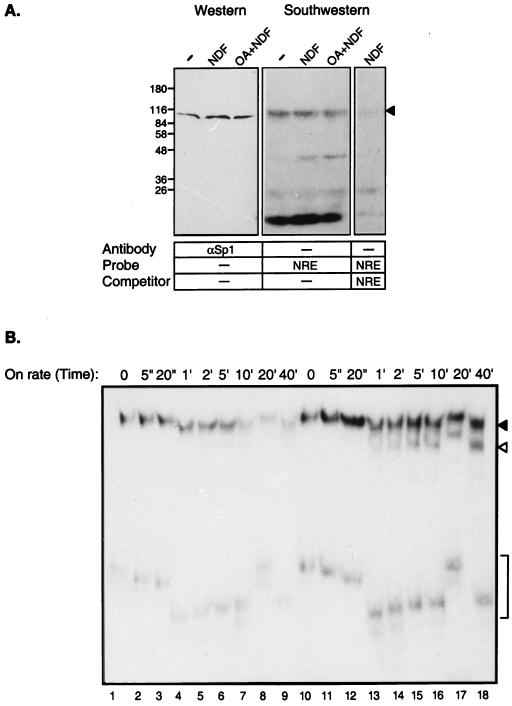

NDF regulation of Sp1 binding activity is independent of monomeric Sp1 DNA binding capacity.

The observed NDF-induced increase in Sp1 binding to the NRE may be attributed to a change in protein level or to enhanced DNA binding capacity. To gain an insight into the underlying mechanism, Western and Southwestern analyses were performed to determine if there was a change in Sp1 protein levels or in its capability to bind DNA. Immunoblotting of whole-cell extracts with anti-Sp1 antibodies excluded the possibility that changes in protein levels were responsible for increased binding of a protein complex to the NRE (Fig. 6A, left). Southwestern analysis of the nuclear extracts with labeled NRE as a probe showed that the binding of a monomeric Sp1 was not affected by NDF treatment (Fig. 6A, center). However, NRE binding to an unidentified protein with a molecular weight of approximately 45,000 was increased by NDF. Nevertheless, combined treatment with NDF and okadaic acid failed to affect the binding of either p45 or Sp1 (p110) to the NRE (Fig. 6A), although this treatment inhibited NDF-induced complex formation on the NRE oligonucleotide in EMSA (Fig. 5A). The specificity of binding of the labeled NRE probe to gel-separated proteins, including Sp1, was evident from the right panel of Fig. 6A: an unlabeled NRE oligonucleotide displaced the labeled probe from all protein bands. Conceivably, although NDF increases the phosphorylation of Sp1, this modification apparently regulates the oligomerization state of Sp1 or its interaction with other proteins, since NRE binding of monomeric Sp1 was not altered.

FIG. 6.

Sp1 binding and kinetics of complex formation on the NRE. (A) Southwestern analysis. Whole-cell extracts were prepared from P-19 cells that were untreated (−) or treated for 30 min with NDFβ. A third culture was incubated for 20 min with okadaic acid (OA) prior to treatment with NDF. Duplicate extracts (60 μg) were separated by SDS-PAGE and then subjected to either Western blot analysis with an antibody to Sp1 (left) or to Southwestern analysis with a labeled NRE probe (center and right). For control of NRE binding specificity, the Southwestern analysis was also performed in the presence of an excess of the unlabeled NRE probe (right). The Sp1 band is labeled by an arrowhead. (B) On-rate kinetics of complex formation on the NRE. Whole P-19 cell extracts prepared from untreated (lanes 1 to 9) or NDF-treated (lanes 10 to 18) cells were incubated in EMSA binding buffer. Equal volumes were removed and incubated for the indicated time intervals with a labeled NRE probe. At the end of the incubation, samples were loaded on a running mobility shift gel. The positions of the NRE-specific complexes are marked by a solid arrowhead (the slowest-migrating complex), an open arrowhead, and brackets (the fastest-migrating complex). Time is marked as seconds (“) or minutes (’). Note that due to continuous electrophoresis while loading samples on the gel, all of the bracket-labeled bands represent the same complex.

To detect such Sp1-containing complexes following treatment with NDF, an on-rate analysis was performed. Whole-cell extracts were incubated with the NRE probe for various time intervals (Fig. 6B). Two significant differences between untreated and NDF-treated extracts were observed (Fig. 6B, lanes 1 to 9 and lanes 10 to 18, respectively). First, at the shortest time intervals, NRE binding to both the slowest-migrating and fastest-migrating complexes was already increased by NDF (Fig. 6B). Second, upon longer incubation with the NRE probe, the two slower-migrating complexes displayed higher stability in the NDF-treated extracts (Fig. 6B). Thus, NDF appears to induce complex formation of Sp1 and other proteins on the NRE site.

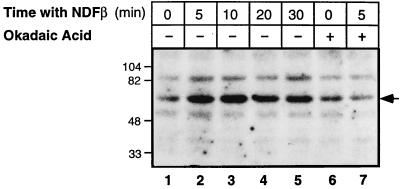

An NDF-stimulatable kinase of approximately 60 kDa phosphorylates Sp1 and is repressed by okadaic acid.

To test the scenario that NDF increases the phosphorylation of Sp1, which in turn leads to transactivation from the NRE, we analyzed extracts of NDF-treated P-19 cells by using an in-gel kinase assay. As a substrate for in-gel phosphorylation, we used a recombinant Sp1 protein, in the form of a fusion protein with GST. After denaturation and renaturation, the gel-resolved proteins were incubated with [γ-32P]ATP to detect in situ the Sp1-specific kinase(s). Three major bands of kinase activity were observed in the resolved extracts. Of these, a prominent band of approximately 60 kDa was rapidly induced by NDF, and its activity was sustained (Fig. 7). A second major protein band (ca. 84 kDa) was also detected in gels that were polymerized in the presence of GST alone (data not shown), and thus it was considered to be nonspecific for Sp1. Importantly, the observed induction of the 60-kDa kinase activity by NDF was blocked by pretreatment of cells with 0.5 μM okadaic acid (Fig. 7, compare lanes 2 and 7), in agreement with the inhibitory effect of okadaic acid on Sp1 binding to the NRE (Fig. 5A). Interestingly, a third kinase band (ca. 45 kDa) displayed sensitivity to okadaic acid and underwent weak activation by NDF (Fig. 7), implying that it is functionally related to the 60-kDa kinase. In conclusion, a renaturable Sp1-specific kinase, whose activity is inducible by NDF, exists in P-19 cells. This kinase may serve to transactivate Sp1 action at the NRE.

FIG. 7.

The kinase that enhances Sp1 binding to NRE is NDFβ inducible and okadaic acid sensitive. P-19 cells were treated with NDFβ for the indicated time intervals in the absence (−) or presence (+) of 0.5 μM okadaic acid (added 20 min prior to NDFβ). Cell extracts were then analyzed for kinase activity by using a recombinant form of the human Sp1 protein and an in-gel kinase assay as detailed in Materials and Methods. The position of the kinase which is induced by NDF and inhibited by okadaic acid is marked by an arrow. The locations of molecular weight marker proteins are indicated in thousands.

DISCUSSION

Sp1 binding to specific response elements and transactivation of its transcriptional function are regulated by a variety of extracellular stimuli. Insulin-like growth factor I regulates the elastin gene through disruption of Sp1 DNA binding (31), and transforming growth factor β enhances transcription of both the α2(I) collagen gene (28) and the p15 cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor (42) through an Sp1 consensus site. Likewise, EGF stimulation of the gastrin promoter is mediated by Sp1 (43). The present study extends this latter observation to another growth factor of the EGF family, NDF. Our survey of other EGF-like ligands implies that Sp1 mediates, to various extents, transcriptional regulation by most, if not all, ligands of ErbB receptors. In addition, cell lines expressing different combinations of the four ErbB receptors were responsive to NDF and EGF, suggesting that Sp1 acts downstream of all ErbB proteins (Fig. 2 and our unpublished observations). Several independent lines of evidence suggest a role for Sp1 in transmission of ErbB signals. (i) A full-length promoter containing the Sp1 binding site, as well as a derivative 20-bp sequence, can confer transcriptional activation by NDF of two reporter genes in living cells (Fig. 1C). (ii) NDF treatment of living cells increased the binding of a nuclear factor, which is recognized by anti-Sp1 antibodies, to the minimal NRE sequence element (Fig. 2 and 4). (iii) the observation that NDF can elevate phosphorylation of Sp1 (Fig. 5C and D) indirectly supports the notion that this transcription factor lies downstream to ErbB.

The sequence we identified as the NDF-regulated element differs from the common consensus Sp1 binding sites, the GC or GT boxes (33). Nevertheless, an NRE-related sequence, which contains three repeats of the element CCACCC, was identified as a basal and an inducible sequence bound by Sp1 in the interleukin-6 promoter (35). Another CA-rich sequence, the retinoblastoma control element, which is regulated by the retinoblastoma protein (Rb), was localized to the promoters of several growth-regulatory genes, such as c-fos and c-myc (52). This element binds several transcription factors including Sp1 and Sp3 (36, 63) and, depending on the cellular context, will be repressed or stimulated by Rb. Sp3 has been demonstrated to repress Sp1-mediated transcription due to competition for Sp1 binding sites (25). Thus, the effect of Rb may depend on the ratio between Sp1 and Sp3 molecules in a cell. Our preliminary analysis, however, did not detect functional interaction of Rb and Sp1 at the NRE.

The slow kinetics of transactivation of Sp1 by NDF probably reflects processing of the signal initiated by tyrosine phosphorylation of ErbBs (Fig. 2). However, the exact molecular mechanism that leads to Sp1 activation remains unclear. Analyses of Sp1 structure and function have revealed that the protein can be separated into discrete functional domains: a DNA binding domain and four separate domains that govern transcriptional activation (34). Our Southwestern analysis implies that Sp1 transactivation may not be due to increased affinity of the monomeric Sp1 DNA binding domain to the NRE (Fig. 6A). Sp1 binds to a single GC box as a monomer. However, higher-order complexes between Sp1 monomers are assembled via direct protein-protein interactions that do not involve additional contacts with DNA but require the two N-terminal transactivation domains (47). Sp1 phosphorylation may circumvent the need for a high local protein concentration by increasing the affinity of protein-protein interactions and thus facilitating the formation of Sp1 multimers on DNA without a change in monomeric DNA binding affinity, as implied by the Southwestern assay (Fig. 6A). Moreover, phosphorylation of Sp1 may affect complex formation with other proteins, as suggested by the on-rate analysis (Fig. 6B), resulting in the formation of an Sp1-containing complex on the NRE site. GBF, a GC homopolymer binding factor, was identified as a second factor that binds to the GC box lying downstream of the E-box of the AChR α subunit (fastest-migrating complex in EMSA) (8). Interactions between this factor and Sp1 may facilitate complex formation on the NRE in NDF-stimulated cells, thereby regulating transcription.

Pharmacological intervention of the signaling pathway leading to NRE binding yielded some new information. Inhibition of tyrosine phosphorylation by using either the general inhibitor genistein or an ErbB-specific tyrphostin efficiently reduced the NDF-dependent complex formation on the NRE (Fig. 5A). This observation is consistent with the requirement for tyrosine phosphorylation at the ErbB level and at the linear cascade leading to MAPK activation. Indeed, MAPK has been implicated in the regulation of two distinct subunits of the AChR by the neuregulin isoforms AChR-inducing activity (57) and heregulin (3). Inhibition of PKC did not affect Sp1 binding to the NRE (Fig. 5A), although TPA, an agonist of PKC, effectively transactivated Sp1 (Fig. 3). Similarly, a PKA-specific agonist exerted no effect on the formation of the Sp1-NRE complex (Fig. 5A), although it has been previously demonstrated that PKA can directly phosphorylate Sp1 (53). Conceivably, the functional linkage of ErbBs to Sp1 is mediated by MAPK but not by PKC or PKA, although these two kinases may be involved in activation of Sp1 by alternative extracellular stimuli.

The inhibitory effect of okadaic acid (Fig. 5A) is interesting in light of the observations that dephosphorylation of Sp1 enhances its DNA binding activity (39) and that treatment of leukemic cells with okadaic acid enhances WAF1/CIP1 expression through Sp1 activation (10). In both these cases, PP2A directly acted on Sp1, whereas in the pathway linking NDF to Sp1, okadaic acid appears to act upstream of Sp1. Several protein kinases were implicated in the regulation of Sp1 activity, including a DNA-dependent protein kinase, whose phosphorylation of Sp1 does not affect its transactivation or DNA binding activity (29). In addition, both PKA (53) and casein kinase II, which is inhibitory to Sp1 (4), were implicated in previous studies. None of these kinases, however, appears similar to the 60- to 65-kDa protein kinase activity that we detected by using an in-gel kinase assay (Fig. 7). The identity of this NDF-inducible protein kinase and the pathway leading to its activation remain unclear. Nevertheless, the following sequence of events is likely to precede the augmentation of Sp1 binding to the NRE: NDF binding to an ErbB protein is followed by rapid stimulation of tyrosine phosphorylation and stepwise activation of the cascade leading to MAPK activation. The Sp1-specific protein kinase of 60 to 65 kDa is presumably located downstream of one of these kinases. Dephosphorylation by PP2A, or a related phosphatase, of one of the kinases upstream of Sp1 presumably activates Sp1 phosphorylation. Alternatively, it may be that PP2A dephosphorylates a site(s) in Sp1 which is required for activation of Sp1 in conjunction with phosphorylation of a distinct site (Fig. 5C). Upon phosphorylation, this transcription factor may oligomerize or associate with another cellular component(s), leading to enhanced binding to the NRE.

Signaling by NDF, as well as by other EGF-like ligands, is funneled into a complex signaling network that diversifies and tunes mitogenic and differentiation signals downstream of the 10 homo- and heterodimeric combinations of the four ErbB proteins (reviewed in reference 2). Like its primitive versions in worms (38) and in flies (50), the mammalian ErbB network acts primarily through the MAPK pathway. Our present results imply that most dimers of ErbB proteins are coupled to Sp1 transactivation. Consistent with this notion, a Drosophila zinc finger transcription factor, termed stripe, was shown to act downstream of the insect homologue of ErbB proteins (20). In addition, Krox-20 (61) and Egr-1 (40), two zinc finger transcription factors distinct from Sp1, were shown to be under transcriptional and translational control of NDF and EGF, respectively. Conceivably, the signaling machinery downstream of ErbBs translates extracellular signals into distinct gene expression programs by controlling multiple zinc finger transcription factors. This mechanism probably mediates the many inductive processes that are regulated by NDF and ErbB proteins, including the interaction between nerve and Schwann cells (45), the survival effect of nonneuronal cells on neurons (64), mesenchyme-epithelial cell interactions in parenchymal organs (67), and neurons and striated muscles at the synapse site (19). This last example is better understood: in addition to zinc finger proteins (8), GABP, an Ets-like transcription factor, regulates spatial expression of the nicotinic AchR at the neuromuscular synapse (54).

If all ErbB proteins are coupled to Sp1 activation, how is signal specificity maintained? Specificity of gene expression may be conferred by modifying the glycosylation (30) or phosphorylation (29) states of Sp1 or by tissue-specific expression of components of the ErbB-Sp1 signaling module. However, the ubiquitous expression of three of the four Sp1 proteins weakens the possibility that spatial and temporal controls of Sp1 expression confer specificity to NDF signaling. Alternatively, Sp1 may act as a scaffolding protein (9) that facilitates binding or enhances the transcriptional activation of additional transcription factors, whose expression is less ubiquitous. Once again, transcription from the ɛ and δ subunits of the nicotinic AchR may serve as an example: in addition to the NRE, these two promoters contain an E-box element (Fig. 1A) that binds myogenic factors such as myogenin and Myf-5 (18). According to a recent report, regulation of the α subunit of the AchR is under complex control by myogenic as well as nonmyogenic transcription factors, which include Sp1, Sp3, and three additional distinct factors (7). Recently, it has been shown that Sp1 may interact with histone deacetylases and thereby actively repress transcription. This interaction may be regulated by Sp1 phosphorylation, which will cause its dissociation from histone deacetylases, thereby alleviating repression (59). Thus, Sp1 binding to the NRE may be part of a complex cascade of events leading to transcriptional activation of NDF target genes in synergy with tissue- and stage-specific factors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank V. Witzemann for the p(−228/+35)AChRɛ-CAT promoter plasmid, Scott L. Friedman for the pCI-Sp1 plasmid, and Alexander Levitzki for tyrphostin AG2002.

This work was supported by grants from the National Cancer Institute of the U.S. National Institutes of Health (grant CA-72981) and the Israel Science Foundation administered by the Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alroy I, Towers T L, Freedman L P. Transcriptional repression of the interleukin-2 gene by vitamin D3: direct inhibition of NFATp/AP-1 complex formation by a nuclear hormone receptor. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:5789–5799. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.10.5789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alroy I, Yarden Y. The ErbB signaling network in embryogenesis and oncogenesis: signal diversification through combinatorial ligand-receptor interactions. FEBS Lett. 1997;410:83–86. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00412-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Altiok N, Altiok X, Changeux J P. Heregulin-stimulated acetylcholine receptor gene expression in muscle: requirement for MAP kinase and evidence for a parallel inhibitory pathway independent of electrical activity. EMBO J. 1997;16:717–725. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.4.717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Armstrong S A, Barry D A, Leggett R W, Mueller C R. Casein kinase II-mediated phosphorylation of the C terminus of Sp1 decreases its DNA binding activity. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:13489–13495. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.21.13489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baldwin T J, Burden S J. Isolation and characterization of the mouse acetylcholine receptor delta subunit gene: identification of a 148-bp cis-acting region that confers myotube-specific expression. J Cell Biol. 1988;107:2271–2279. doi: 10.1083/jcb.107.6.2271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ben-Baruch N, Alroy I, Yarden Y. Developmental and physiological roles of ErbB receptors and their ligands in mammals. In: Dickson R B, Salomon D S, editors. Hormones and growth factors in development and neoplasia. Boston, Mass: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1997. pp. 145–168. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bessereau J L, Laudenbach V, Le Poupon C, Changeux J P. Nonmyogenic factors bind nicotinic acetylcholine receptor promoter elements required for response to denervation. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:12786–12793. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.21.12786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bessereau J L, Mendelzon D, LePoupon C, Fiszman M, Changeux J P, Piette J. Muscle-specific expression of the acetylcholine receptor alpha-subunit gene requires both positive and negative interactions between myogenic factors, Sp1 and GBF factors. EMBO J. 1993;12:443–449. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05676.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bidwell J P, Van Wijnen A J, Fey E G, Dweretzky S, Penman S, Stein J L, Lian J B, Stein G S. Osteocalcin gene promoter-binding factors are tissue-specific nuclear matrix components. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:3162–3166. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.8.3162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Biggs J R, Kudlow J E, Kraft A S. The role of transcription factor Sp1 in regulating the expression of the WAF1/CIP1 gene in U937 leukemic cells. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:901–906. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.2.901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burden S, Yarden Y. Neuregulins and their receptors: a versatile signaling module in organogenesis and oncogenesis. Neuron. 1997;18:847–855. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80324-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chu G C, Moscoso L M, Sliwkowski M X, Merlie J P. Regulation of the acetylcholine receptor epsilon subunit gene by recombinant ARIA: an in vitro model for transynaptic gene regulation. Neuron. 1995;14:329–339. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90289-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cohen P, Schelling D, Starck M. Remarkable similarities between yeast and mammalian protein phosphatases. FEBS Lett. 1989;250:601–606. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(89)80804-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Courey A J, Holtzman D A, Jackson S P, Tjian R. Synergistic activation by the glutamine-rich domains of human transcription factor Sp1. Cell. 1989;59:827–836. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90606-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Daniel S, Zhang S, DePaoli R A, Kim K H. Dephosphorylation of Sp1 by protein phosphatase 1 is involved in the glucose-mediated activation of the acetyl-CoA carboxylase gene. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:14692–14697. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.25.14692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Datta P K, Raychaudhuri P, Bagchi S. Association of p107 with Sp1: genetically separable regions of p107 are involved in regulation of E2F- and Sp1-dependent transcription. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:5444–5452. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.10.5444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dong Z, Brennan A, Liu N, Yarden Y, Lefkowitz G, Mirsky R, Jessen K R. Neu differentiation factor is a neuron-glia signal and regulates survival, proliferation, and maturation of rat Schwann cell precursors. Neuron. 1995;15:585–596. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90147-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Durr I, Numberger M, Berberich C, Witzemann V. Characterization of the functional role of E-box elements for the transcriptional activity of rat acetylcholine receptor epsilon-subunit and gamma-subunit gene promoters in primary muscle cell cultures. Eur J Biochem. 1994;224:353–364. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.00353.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Falls D L, Rosen K M, Corfas G, Lane W S, Fischbach G D. ARIA, a protein that stimulates acetylcholine receptor synthesis, is a member of the neu ligand family. Cell. 1993;72:801–815. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90407-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frommer G, Vorbruggen G, Pasca G, Jackle H, Volk T. Epidermal egr-like zinc finger protein of Drosophila participates in myotube guidance. EMBO J. 1996;15:1642–1649. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gazit A, Chen J, App H, McMahon G, Hirth P, Chen I, Levitzki A. Tyrphostins IV—highly potent inhibitors of EGF receptor kinase. Structure-activity relationship study of 4-anilidoquinazolines. Bioorg Med Chem. 1996;4:1203–1207. doi: 10.1016/0968-0896(96)00107-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gill G, Pascal E, Tseng Z H, Tjian R. A glutamine-rich hydrophobic patch in transcription factor Sp1 contacts the dTAFII110 component of the Drosophila TFIID complex and mediates transcriptional activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:192–196. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.1.192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Greenwel P, Hu W, Kohanski R A, Ramirez F. Tyrosine dephosphorylation of nuclear proteins mimics transforming growth factor beta 1 stimulation of alpha 2(I) collagen gene expression. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:6813–6819. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.12.6813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hagen G, Muller S, Beato M, Suske G. Cloning by recognition site screening of two novel GT box binding proteins: a family of Sp1 related genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:5519–5525. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.21.5519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hagen G, Muller S, Beato M, Suske G. Sp1-mediated transcriptional activation is repressed by Sp3. EMBO J. 1994;13:3843–3851. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06695.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Holmes W E, Sliwkowski M X, Akita R W, Henzel W J, Lee J, Park J W, Yansura D, Abadi N, Raab H, Lewis G D, Shepard M, Wood W I, Goeddel D V, Vandlen R L. Identification of heregulin, a specific activator of p185erbB2. Science. 1992;256:1205–1210. doi: 10.1126/science.256.5060.1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hunter T, Karin M. The regulation of transcription by phosphorylation. Cell. 1992;70:375–387. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90162-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Inagaki Y, Truter S, Ramirez F. TGF-β stimulates α2(I) collagen gene expression through a cis-acting element that contains an Sp1-binding site. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:14828–14834. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jackson S P, MacDonald J J, Lees-Miller S, Tjian R. GC box binding induces phosphorylation of Sp1 by a DNA-dependent protein kinase. Cell. 1990;63:155–165. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90296-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jackson S P, Tjian R. O-glycosylation of eukaryotic transcription factors: implications for mechanisms of transcriptional regulation. Cell. 1988;55:125–133. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90015-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jensen D E, Rich C B, Terpstra A J, Farmer S R, Foster J A. Transcriptional regulation of the elastin gene by insulin-like growth factor-I involves disruption of Sp1 binding. Evidence for the role of Rb in mediating Sp1 binding in aortic smooth muscle cells. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:6555–6563. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.12.6555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jo S A, Zhu X, Marchionni M A, Burden S J. Neuregulins are concentrated at nerve-muscle synapses and activate ACh- receptor gene expression. Nature. 1995;373:158–161. doi: 10.1038/373158a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kadonaga J T, Carner K R, Masiarz F R, Tjian R. Isolation of cDNA encoding transcription factor Sp1 and functional analysis of the DNA-binding domain. Cell. 1987;51:1079–1090. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90594-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kadonaga J T, Courey A J, Ladika J, Tijan R. Distinct regions of Sp1 modulate DNA binding and transcriptional activation. Science. 1988;242:1566–1570. doi: 10.1126/science.3059495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kang S-H, Brown D A, Kitajima I, Xu X, Heindenreich O, Gryaznov S, Nerenberg M. Binding and functional effects of transcriptional factor Sp1 on the murine interleukin-6 promoter. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:7330–7335. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.13.7330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim S-J, Onwuta U S, Lee Y I, Li R, Botchan M R, Robbins P D. The retinoblastoma gene product regulates Sp1-mediated transcription. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:2455–2463. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.6.2455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kingsley C, Winoto A. Cloning of GT box binding proteins: a novel Sp1 multigene family regulating T-cell receptor gene expression. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:4251–4261. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.10.4251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kornfeld K. Vulval development in Caenorbaditis elegans. Trends Genet. 1997;13:55–61. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(97)01005-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leggett R W, Armstrong S A, Barry D, Mueller C R. Sp1 is phosphorylated and its DNA binding activity down-regulated upon terminal differentiation of the liver. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:25879–25884. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.43.25879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lemaire P, Vesque C, Schmitt J, Stunnenberg H, Frank R, Charnay P. The serum-inducible mouse gene Krox-24 encodes a sequence-specific transcriptional activator. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:3456–3467. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.7.3456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Letovsky J, Dynan W S. Measurment of the binding of transcription factor Sp1 to a single GC box recognition sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:2639–2673. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.7.2639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li J-M, Nicholas M A, Chandrasekharan S, Xiong Y, Wang X-F. Transforming growth factor β activates the promoter of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p15INK4B through an Sp1 consensus site. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:26750–26753. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.45.26750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Merchant J L, Shiotani A, Mortensen E R, Shumaker D K, Abraczinskas D R. Epidermal growth factor stimulation of the human gastrin promoter requires Sp1. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:6314–6319. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.11.6314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Meyer D, Birchmeier C. Distinct isoforms of neuregulin are expressed in mesenchymal and neuronal cells during mouse development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:1064–1068. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.3.1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Murphy P, Topilko P, Schneider-Maunoury S, Seitanidou T, Evercooren B V, Charnay P. The regulation of Krox-20 expression reveals important steps in the control of peripheral glial cell development. Development. 1996;122:2847–2857. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.9.2847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Orr-Urtreger A, Trakhtenbrot L, Ben-Levi R, Wen D, Rechavi G, Lonai P, Yarden Y. Neural expression and chromosomal mapping of Neu differentiation factor to 8p12-p21. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:1867–1871. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.5.1867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pascal E, Tjian R. Different activation domains of Sp1 govern formation of multimers and mediate transcriptional synergism. Genes Dev. 1991;5:1646–1656. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.9.1646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Peles E, Bacus S S, Koski R A, Lu H S, Wen D, Ogden S G, Ben-Levy R, Yarden Y. Isolation of the neu/HER-2 stimulatory ligand: a 44 kd glycoprotein that induces differentiation of mammary tumor cells. Cell. 1992;69:205–216. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90131-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Peles E, Yarden Y. Inhibitors of protein tyrosine kinases. In: Sandler M, Smith J, editors. Design of enzyme inhibitors as drugs. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press; 1993. pp. 127–163. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Perrimon N, Perkins L A. There must be 50 ways to rule the signal: the case of the Drosophila EGF receptor. Cell. 1997;89:13–16. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80177-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pinkas-Kramarski R, Soussan L, Waterman H, Levkowitz G, Alroy I, Klapper L, Lavi S, Seger R, Ratzkin B, Sela M, Yarden Y. Diversification of Neu differentiation factor and epidermal growth factor signaling by combinatorial receptor interactions. EMBO J. 1996;15:2452–2467. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Robbins P D, Horowitz J M, Mulligan R C. Negative regulation of human c-fos expression by the retinoblastoma gene product. Nature. 1990;346:668–671. doi: 10.1038/346668a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rohlff C, Ahmad S, Borellini F, Lei J, Glazer R I. Modulation of transcription factor Sp1 by cAMP-dependent protein kinase. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:21137–21141. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.34.21137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schaeffer L, Duclert N, Huchet-Dymanus M, Changeux J-P. Implication of a multisubunit Ets-related transcription factor in synaptic expression of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. EMBO J. 1998;17:3078–3090. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.11.3078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Seger R, Krebs E G. The MAP kinase signaling cascade. FASEB J. 1995;9:726–735. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Seidel H M, Milocco H L, Lamb P, Darnell J E, Stein R B, Rosen J. Spacing of palindromic half sites as a determinant of selective STAT (signal transducers and activators of transcription) DNA binding and transcriptional activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:3041–3045. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.7.3041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Si J, Luo Z, Mei L. Induction of acetylcholine receptor gene expression by ARIA requires activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:19752–19759. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.33.19752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sliwkowski M X, Schaefer G, Akita R W, Lofgren J A, Fitzpatrick V D, Nuijens A, Fendly B M, Cerione R A, Vandlen R L, Carraway K L. Coexpression of erbB2 and erbB3 proteins reconstitutes a high affinity receptor for heregulin. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:14661–14665. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sowa Y, Orita T, Minawikawa S, Nakano K, Mizuno T, Nomura H, Sakai T. Histone deacetylase inhibitor activates the WAF1/Cip1 gene promoter through the Sp1 sites. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;241:142–150. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sunyer T, Merlie J P. Cell type- and differentiation-dependent expression from the mouse acetylcholine receptor ɛ-subunit promoter. J Neurosci Res. 1993;36:224–234. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490360213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Topilko P, Schneider-Maunoury S, Levi G, Baron-Van Evercooren A, Chennoufi A B Y, Seitanidou T, Babinet C, Charnay P. Krox-20 controls myelination in the peripheral nervous system. Nature. 1994;371:796–799. doi: 10.1038/371796a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tzahar E, Levkowitz G, Karunagaran D, Yi L, Peles E, Lavi S, Chang D, Liu N, Yayon A, Wen D, Yarden Y. ErbB-3 and ErbB-4 function as the respective low and high affinity receptors of all Neu differentiation factor/heregulin isoforms. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:25226–25233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Udvadia A J, Tempelton D J, Horowitz J M. Functional interactions between the retinoblastoma (Rb) protein and Sp-family members: superactivaton by Rb requires amino acids necessary for growth suppression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:3953–3957. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.9.3953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Verdi J M, Groves A K, Farinas I, Jones K, Marchionni M A, Reichardt L F, Anderson D J. A reciprocal cell-cell interaction mediated by NT-3 and neuregulins controls the early survival and development of sympathetic neuroblasts. Neuron. 1996;16:515–527. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80071-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wen D, Peles E, Cupples R, Suggs S V, Bacus S S, Luo Y, Trail G, Hu S, Silbiger S M, Ben-Levy R, Luo Y, Yarden Y. Neu Differentiation Factor: a transmembrane glycoprotein containing an EGF domain and an immunoglobulin homology unit. Cell. 1992;69:559–572. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90456-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Williams T, Tjian R. Analysis of the DNA-binding and activation properties of the human transcription factor AP-2. Genes Dev. 1988;2:670–682. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.4.670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yang Y, Spitzer E, Meyer D, Sachs M, Niemann C, Hartmann G, Weidner K M, Birchmeier C, Birchmeier W. Sequential requirement of hepatocyte growth factor and neuregulin in the morphogenesis and differentiation of the mammary gland. J Cell Biol. 1995;131:215–226. doi: 10.1083/jcb.131.1.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhang S, Kim K-H. Protein kinase CK2 down-regulates glucose-activated expression of the acetyl-CoA carboxylase gene. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1997;338:227–232. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1996.9809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zutter M M, Ryan E E, Painter A D. Binding of phosphorylated Sp1 protein to tandem Sp1 binding sites regulates α2 integrin gene core promoter activity. Blood. 1997;90:678–689. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]