Abstract

The histone N-terminal tails have been shown previously to be important for chromatin assembly, remodeling, and stability. We have tested the ability of human SWI-SNF (hSWI-SNF) to remodel nucleosomes whose tails have been cleaved through a limited trypsin digestion. We show that hSWI-SNF is able to remodel tailless mononucleosomes and nucleosomal arrays, although hSWI-SNF remodeling of tailless nucleosomes is less effective than remodeling of nucleosomes with tails. Analogous to previous observations with tailed nucleosomal templates, we show both (i) that hSWI-SNF-remodeled trypsinized mononucleosomes and arrays are stable for 30 min in the remodeled conformation after removal of ATP and (ii) that the remodeled tailless mononucleosome can be isolated on a nondenaturing acrylamide gel as a novel species. Thus, nucleosome remodeling by hSWI-SNF can occur via interactions with a tailless nucleosome core.

In eukaryotic cells, DNA is compacted into chromatin, the central unit of which is the nucleosome. The nucleosome consists of an octamer of two each of the four core histones (H2A, H2B, H3, and H4) and approximately 146 bp of DNA. The core histones are small proteins (<140 amino acids), and all have a basic N-terminal tail. These tails have been shown to be important for a wide range of regulatory processes (19, 22, 34, 38, 54, 63). The importance of the H4 histone tail is also suggested by its high degree of conservation (28).

The N-terminal tails directly interact with numerous regulatory complexes. Since the histone tails are active sites for posttranslational modifications like phosphorylation, acetylation, and deacetylation (1, 5), they must interact with complexes like histone acetyltransferases (7, 30, 41, 48) and deacetylases (53, 67). Histone chaperones such as CAF-1 interact primarily with acetylated histones (60), and repressive complexes such as the SIR complex in S. cerevisiae are believed to form structures on nucleosomes by binding the histone tails (21). These studies and others have led to the notion that the tails provide an essential handle for manipulating the nucleosome.

The histone tails were not resolved by the recent crystal structure of the nucleosome (37), implying that they protrude from the nucleosome in an unstructured manner. Early experiments demonstrated that they could be effectively cleaved from the rest of the nucleosome with trypsin (4), while other parts of the histones are protected from digestion via compaction into the nucleosome core. Limited trypsinization removes approximately 70% of the tail portion of the histones, including all of the known human acetylation sites (55). While the trypsinization procedure does not remove the entire tail, the terms trypsinized template and tailless template will be used synonymously throughout this paper for simplicity.

The purpose of this study is to examine whether histone tails are required for the activity of the human SWI-SNF (hSWI-SNF) family of ATP-dependent nucleosome remodeling complexes. Members of the SWI-SNF family of remodeling complexes have been found in yeast (10, 16, 43), Drosophila melanogaster (18, 52), and mammals (31, 51, 64). In yeast, there are two related complexes termed SWI-SNF and RSC (12). Each of these complexes has more than 10 subunits, 6 of which are highly related to each other in their primary sequences (9, 11, 13, 32, 44). In humans, the SWI-SNF family has been defined as those complexes that have either Brg1 or hBrm as a central DNA-dependent ATPase. Brg1 and hBrm both have a high degree of similarity to the yeast SWI2-SNF2 subunit (14, 29, 39) and the STH1 subunit of RSC (12). Purified hSWI-SNF preparations also contain proteins with a high degree of similarity to three other members of the yeast SWI-SNF and RSC complexes and contain at least eight total peptides (51, 64, 65). It now appears that hSWI-SNF preparations may contain heterogeneous populations of highly related complexes having many of the same subunits and similar activities in nucleosome remodeling assays.

SWI-SNF complexes have been shown to increase the binding of transcription factors (8, 16, 23, 49), alter the nucleosomal DNase cleavage pattern (16, 31), and increase restriction enzyme cleavage of nucleosomal DNA (35, 49, 56). Recent studies have isolated a stable remodeled form of the nucleosome that can form as a consequence of hSWI-SNF (49) or yeast RSC (36) function. Based on these findings, it has been proposed that the SWI-SNF complexes function by using the energy of ATP hydrolysis to interconvert nucleosomes between their normal structure and a remodeled structure that has an altered DNA path.

A second family of ATP-dependent remodeling complexes has been characterized primarily in Drosophila and contains the ISWI protein as the ATPase subunit (57). One member of this family, the NURF complex (58), has been shown to require histone N termini for remodeling (20). In contrast, we report here that hSWI-SNF does not require histone N termini to remodel nucleosomes. This provides an important mechanistic distinction between NURF and hSWI-SNF and suggests that the SWI-SNF family of complexes are able to remodel nucleosome structure via interactions with the tailless nucleosome core.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Purification of hSWI-SNF.

hSWI-SNF was purified as described previously (51). Briefly, approximately 50 mg of nuclear extract (3) from Flag-tagged Ini1 HeLa cell lines was incubated 10 to 14 h at 4°C with 1 ml of anti-Flag antibody beads (Kodak, Inc.). The beads were washed with 5 column volumes of BC150 (150 mM KCl, 20% glycerol, 20 mM HEPES [pH 7.9], 0.2 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol [DTT], 0.2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride [PMSF]), then were washed with 5 column volumes of BC300 (300 mM KCl, 20% glycerol, 20 mM HEPES [pH 7.9], 0.2 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM DTT, 0.2 mM PMSF), and finally were washed with 3 column volumes of BC100 (100 mM KCl, 20% glycerol, 20 mM HEPES [pH 7.9], 0.2 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM DTT, 0.2 mM PMSF). The column was incubated for 1 h with 20-fold molar excess Flag peptide (Kodak, Inc.) in BC100. Eluted hSWI-SNF was quantified by a Bradford assay, and purity was judged to be 50% by silver stain analysis.

Purification of nucleosomes, trypsinized nucleosomes, histones, and trypsinized histones.

H1-depleted HeLa nucleosomes were prepared and quantitated as described previously (17, 49, 61), with the exception that nuclei extracted by a Dignam procedure were used as the starting material.

Trypsinized nucleosomes were made essentially as described previously (2). This involved digesting polynucleosomes (0.5 μg/μl) in buffer V (25 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 1 mM EDTA) with trypsin (6.7 ng/μl; Sigma, Inc.) at room temperature for 20 to 40 min. The trypsinization reaction was stopped with 20-fold excess (wt/wt) soybean trypsin inhibitor (Sigma, Inc.), and the reaction was monitored by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). Quantitation of nucleosomes is given as the DNA concentration.

HeLa histones were purified via hydroxyapatite chromatography as described previously (66). Trypsinized histones were prepared by creating a stock of trypsinized nucleosomes and then purifying the histones from the DNA, trypsin, and inhibitor via hydroxyapatite chromatography as described previously (66), with the exceptions that binding of the nucleosomes to the hydroxyapatite (Bio-Rad, Inc.) and washing of the column was done in LSB (75 mM NaCl, 50 mM NaH2PO4 [pH 6.8], 0.5 mM PMSF).

Reconstitution and purification of labeled mononucleosomes.

The template designated TPT (49) is 155 bp long and contains a rotational positioning sequence. This template was end labeled with a Klenow fill-in reaction either at the EcoRI end, using [α-32P]dATP (NEN Life Sciences, Inc.), or at the MluI end, using [α-32P]dCTP (NEN Life Sciences, Inc.). Free nucleotides were removed through a Sephadex G-50 (Pharmacia, Inc.) spin column, the DNA was ethanol precipitated, and the fragment was assembled into nucleosomes by the histone octamer transfer reaction (45). To assemble tailed nucleosomes, 90-fold excess tailed donor nucleosomes were used; to make trypsinized mononucleosomes, 26-fold excess tailless donors were used. Assembly was monitored on a 5% nondenaturing acrylamide gel. After assembly, the assembled nucleosomes were purified on a 5 to 30% glycerol gradient (glycerol, 50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 1 mM EDTA, bovine serum albumin [BSA] [0.1 mg/ml]) run at 110,000 × g in a Beckman SW55 rotor for 10 to 14 h at 4°C.

Trypsinized mononucleosomes were also prepared in a second reaction in which 9 ng of end-labeled, glycerol gradient-purified tailed mononucleosomes was diluted to 100 μl with buffer V. Trypsin was added to 5 ng/μl, and the samples were digested for 8 to 20 min. Trypsin digestion was stopped with 15-fold excess (wt/wt) soybean trypsin inhibitor. Digestion was monitored on a 5% nondenaturing acrylamide gel.

Mononucleosome DNase I accessibility assay.

All reactions were carried out with 5.7 ng of total nucleosomal DNA unless otherwise noted. Of that, 0.3 ng was end-labeled nucleosomes and 5.4 ng was unlabeled nucleosomes of similar status (tailed or tailless). For the nucleosome titration experiment shown in Fig. 3B, up to 400 ng of unlabeled nucleosomes of similar status was used as competitor. Mononucleosome disruption reactions were carried out in 25 μl of reaction buffer (72 mM KCl, 15 mM HEPES [pH 7.9], 10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 15% glycerol, 3.5 mM MgCl2, 0.3 mM DTT, 0.3 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM PMSF, BSA [20 μg/ml]) with up to 150 ng of hSWI-SNF for 30 min at 30°C in the presence or absence of 0.5 mM ATP. Tailed nucleosomes were then digested for 2 min with 0.2 U of DNase I (diluted with 25 mM CaCl2, 20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 5 mM NaCl, 2.5% glycerol), tailless nucleosomes were digested for 2 min with 0.05 U of DNase I, and free DNA was digested for 2 min with 0.02 U of DNase I. For assays with higher amounts of nucleosomal competitor (see Fig. 3B), DNase I digestion times were increased up to 8 min. The digestion was stopped with 2 μl of 0.5 M EDTA, pH 8.0. The samples were phenol extracted, ethanol precipitated, and separated on 8% urea sequencing gels as described previously (25).

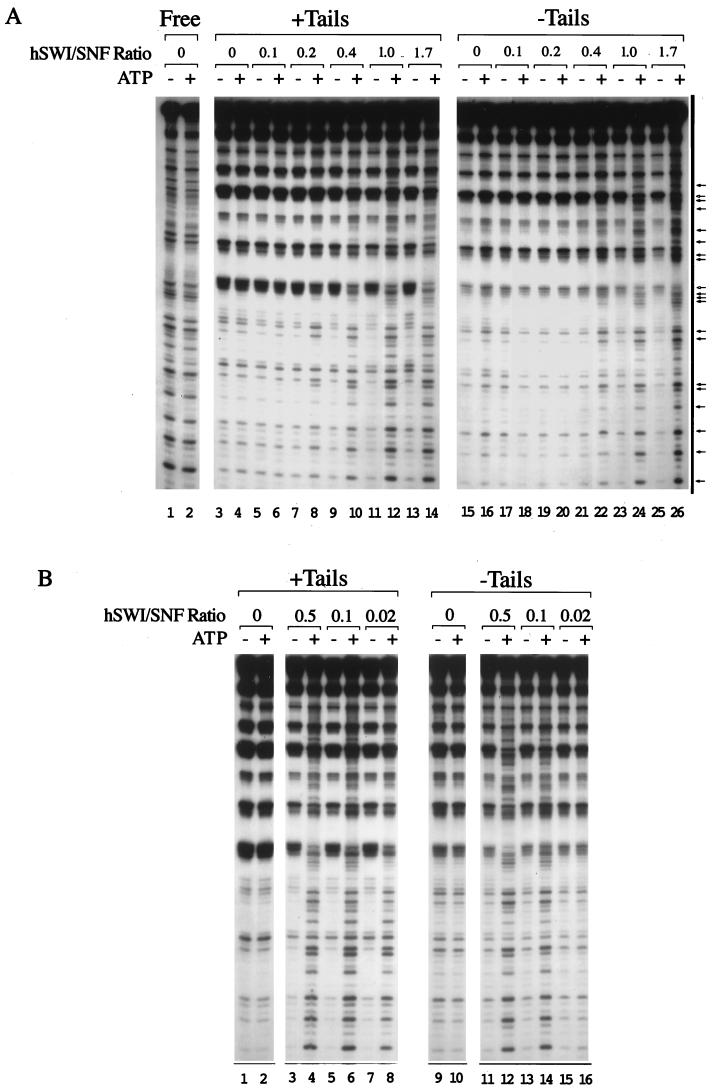

FIG. 3.

The efficiency of remodeling tailed (+Tails) and tailless (−Tails) mononucleosomes was assayed with the DNase I mononucleosome disruption assay by varying the hSWI-SNF/nucleosome molar ratio. (A) The amounts of nucleosomes were held constant (5.4 ng of cold nucleosomes and 0.5 ng of labeled nucleosomes), and the amount of hSWI-SNF was increased up to 150 ng. Molar ratios of hSWI-SNF to nucleosomes are indicated. The arrows with filled heads indicate sites with increased cutting, and the arrows with hollow heads represent sites with decreased cutting. (B) The amounts of hSWI-SNF (150 ng) and labeled nucleosomes (0.5 ng) were held constant, and the amount of cold nucleosomes (tailed or tailless) was increased up to 400 ng. Molar ratios of hSWI-SNF to nucleosomes are indicated. −, without ATP; +, with ATP.

Mononucleosome PstI restriction enzyme accessibility assay.

Reactions were reconstituted exactly as per the DNase I accessibility assays, but instead of incubating at 30°C for 30 min, the remodeling reaction was allowed to proceed up to 60 min. Afterwards, 1 μl of PstI (20 or 50 U/μl) was added and the reaction was allowed to incubate for an additional 30 min. The reactions were then phenol extracted, ethanol precipitated, separated on an 8% urea sequencing gel, and quantified with a Molecular Dynamics PhosphorImager.

Reconstitution of labeled nucleosomal arrays and the plasmid supercoiling assay.

An internally labeled plasmid was prepared as described previously (51) by linearizing pSAB8 (6) with EcoRI. Briefly, the plasmid was then alkaline phosphatase (NEB, Inc.) treated and kinased with T4 polynucleotide kinase (NEB, Inc.) and [γ-32P]ATP (NEN Life Sciences, Inc.). Labeled plasmid was separated from unincorporated nucleotides with a Sephadex G-50 (Pharmacia, Inc.) spin column. The labeled linear plasmid was religated at a concentration of 1 μg/ml with T4 DNA ligase (NEB, Inc.).

Internally labeled plasmid DNA was then reconstituted into nucleosomal arrays by using Xenopus laevis heat-treated assembly extracts (66) and full-length or trypsinized histones as required. The assembled plasmids were layered onto a 10 to 40% glycerol gradient (glycerol, 50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 1 mM EDTA, BSA [0.1 mg/ml]). The gradient was run at 110,000 × g in a Beckman SW55 rotor for 4 h at 4°C. Fractions were collected and analyzed for assembly by deproteinizing and separating on an agarose gel.

Plasmid supercoiling experiments were carried out in 23.5 μl of reaction buffer (65 mM KCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 13 mM HEPES [pH 7.9], 15% glycerol, 7.4 mM MgCl2, 0.3 mM EDTA, 0.3 mM DTT, 0.1 mM PMSF, BSA [20 μg/ml]) containing 0.4 U of wheat germ topoisomerase I (Promega, Inc.) and hSWI-SNF to 300 ng, in either the presence or absence of 4.4 mM ATP. Reaction mixtures were incubated at 30°C for 90 min. The plasmids were deproteinated by adding 6 μl of stop buffer (3% SDS, 100 mM EDTA, 50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 25% glycerol) and 3 μl of proteinase K (20 mg/ml) before incubating at 37°C for 1 h. The samples were phenol extracted, ethanol precipitated, and analyzed on a 1.75% agarose gel in plasmid supercoiling buffer, pH 8.0 (40 mM Tris base, 30 mM NaPO4, 1 mM EDTA), at 40 V for 40 to 48 h.

ATPase assay.

Tailless polynucleosome stocks were prepared as described above. This provided tailless stocks at a DNA concentration of 0.29 mg/ml. Tailed polynucleosomes were prepared for this assay by diluting H1-depleted nucleosome stocks to a DNA concentration of 0.29 mg/ml with the same buffers used to make trypsinized stocks (trypsin was not added, but trypsin inhibitor was).

ATPase assays were carried out at 30°C in 5 μl of reaction buffer (13 mM NaHEPES [pH 7.9], 3 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 60 mM KCl, 9 mM NaCl, 7 mM MgCl2, 6% glycerol, 0.6 mM DTT, 0.3 mM EDTA, 2 μM unlabeled ATP, 30 nM [γ-32P]ATP) with 12 ng of hSWI-SNF per μl (6 nM) and 4 ng of tailed or tailless nucleosomes per μl (∼40 nM). Reactions were initiated by the addition of ATP and MgCl2. At specific times after initiating the reaction, 1-μl aliquots were quenched in 2 μl of stop solution (3% SDS, 100 mM EDTA, 50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5]). Each time point was spotted onto polyethyleneimine-cellulose thin-layer chromatography (TLC) plates (JT Baker, Inc.), which had been prerun in distilled water and dried. Inorganic phosphate was separated from unreacted ATP by running the TLC plates in 0.5 M LiCl and 1 M formic acid. The ratio of inorganic phosphate to ATP was quantified with a Molecular Dynamics PhosphorImager.

Apyrase experiments.

The DNase I mononucleosome assay and the plasmid supercoiling experiments were modified to include apyrase. Apyrase (Sigma, Inc.) was reconstituted to stock concentrations of both 1 and 0.5 U/μl in 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.9)–1 mM MgCl2–1 mM DTT–1 mM EDTA–BSA (1 mg/ml). For both the DNase I and the PstI mononucleosome assays, reactions were reconstituted as described above. One unit of apyrase was then added either before or after incubating at 30°C for 30 min (to test apyrase activity or remodeling stability, respectively). After adding apyrase, the reaction mixture was reincubated at 30°C for the indicated times (0 to 30 min) before treating with DNase I. The remainder of the procedure was performed as described above.

For the plasmid supercoiling experiment, reactions were also reconstituted as described above. Two units of apyrase were then added either before or after incubating at 30°C for 30 min (to test apyrase activity or remodeling stability, respectively). After adding apyrase, the reaction mixture was reincubated at 30°C for the indicated times (30 to 90 min) before deproteinizing and analyzing on a 1.75% agarose gel were performed as described above.

Gel shift of the novel species.

Glycerol gradient purified mononucleosomes (tailed or tailless) were incubated in a 5-μl reaction mixture containing 1 μl of nucleosomes (∼0.15 ng of DNA), 1 μl of MgCl2-H2O-ATP (35 mM MgCl2, 15 mM ATP), 2 μl of hSWI-SNF (100 ng), and 1 μl of BC100. The reaction mixture was incubated at 30°C for 55 min before the addition of 1 μl of plasmid DNA competitor (1 μg/μl). The reaction mixture was reincubated at 30°C for 15 minutes before being run on a 5% nondenaturing acrylamide gel in 1× Tris-borate-EDTA (TBE) at 4°C.

RESULTS

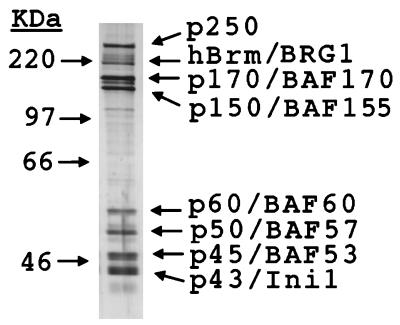

Chromatin remodeling complexes have been characterized by their ability to hydrolyze ATP in a nucleosome-stimulated reaction (12, 16, 46, 58, 59), to alter the topology of arrays of nucleosomes (26, 31, 58, 59), to alter DNase access to mononucleosomes (12, 31, 58), and to increase restriction enzyme access to nucleosomal DNA (35, 49, 58). We used different protocols that measure each of these properties to determine the effects of removing the tails on hSWI-SNF function. All four properties were tested, because it is not clear whether these reactions all reflect the same process or whether they reflect different reactions that are catalyzed by remodeling complexes. To perform these experiments, hSWI-SNF was affinity purified from HeLa cell lines that contain an epitope-tagged copy of Ini1 (51), the smallest subunit of the hSWI-SNF complexes. As judged by SDS-PAGE followed by silver staining, hSWI-SNF purified in this manner is at least 50% pure (Fig. 1) (49, 51). In all assays performed to date, hSWI-SNF purified in this manner retains all the characteristics of SWI-SNF purified by conventional chromatography (31).

FIG. 1.

Purification of hSWI-SNF. hSWI-SNF was purified on an immunoaffinity column, analyzed by SDS-PAGE, and silver stained.

hSWI-SNF remodeling of trypsinized mononucleosomes.

One characteristic activity of many remodeling complexes is the ability to alter the DNase digestion pattern of a rotationally positioned mononucleosome. In the absence of remodeling, cleavage of a rotationally positioned mononucleosome by DNase results in a 10-bp periodicity of maximal and minimal cleavages (Fig. 2C, lane 2). In an ATP-dependent process, hSWI-SNF alters the cleavage pattern of a tailed mononucleosome (Fig. 2C, lanes 4 and 5).

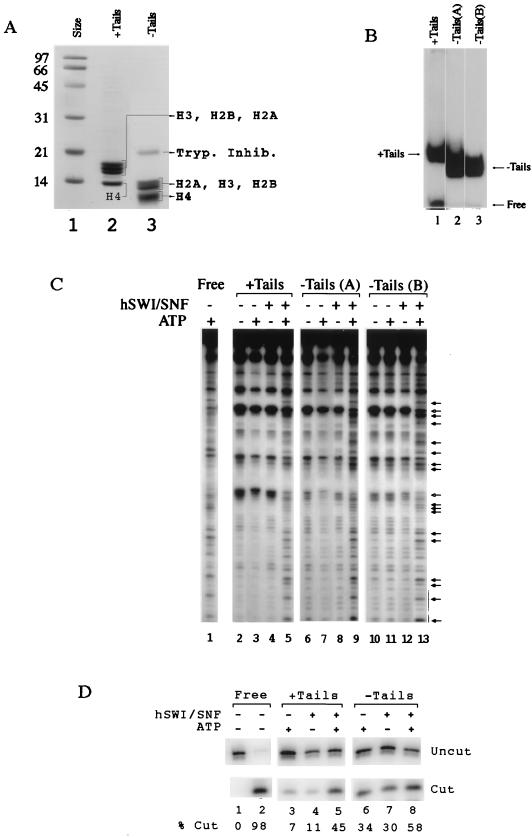

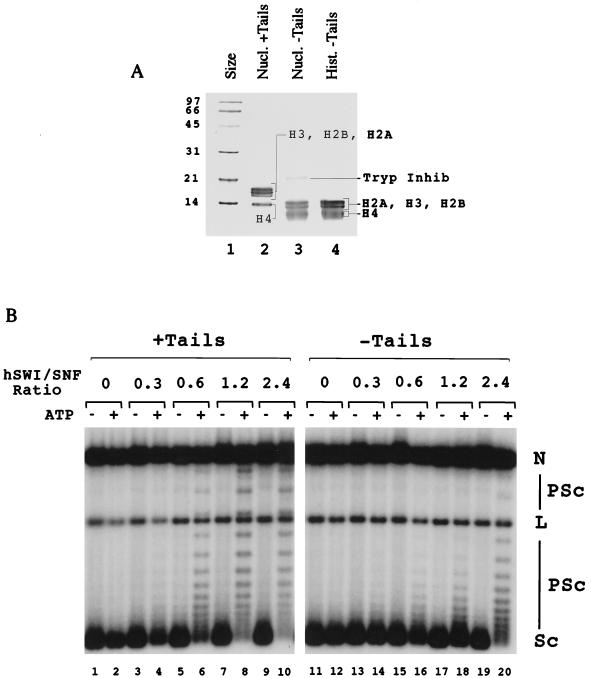

FIG. 2.

hSWI-SNF is able to remodel normal and trypsinized mononucleosomes. (A) SDS-PAGE analysis of tailed and trypsinized donor polynucleosomes used in the histone octamer transfer reaction. Lane 1, size standards (labeled in kilodaltons); lane 2, histones from nontrypsinized H1-depleted polynucleosomes; lane 3, trypsinized polynucleosomes. Tryp. Inhib., trypsin inhibitor. (B) Electrophoretic mobility shift assay of reconstituted nucleosomes showing nucleosomes with tails (lane 1), reconstituted nucleosomes in which the tails have been removed from labeled tailed mononucleosomes after glycerol gradient purification (lane 2), and nucleosomes prepared with the histone octamer transfer reaction using trypsinized donor nucleosomes (lane 3). (C) DNase I mononucleosome disruption assay. Tailed and trypsinized mononucleosomes in the presence or absence of both ATP and 150 ng of hSWI-SNF were digested with DNase I and analyzed by denaturing gel electrophoresis. Lane 1 contains nonnucleosomal DNA, and lanes 2 to 13 contain nucleosomes like those shown in panel B. The arrows with filled heads indicate sites with increased cutting, and the arrows with hollow heads represent sites with decreased cutting. (D) PstI mononucleosome restriction enzyme accessibility assay. Tailed and trypsinized mononucleosomes in the presence and/or absence of both ATP and 92 ng of hSWI-SNF were digested with PstI for 30 min. Reactions were analyzed by denaturing gel electrophoresis. % Cut, ratio of cut fragment to total template.

We used the DNase assay to determine whether hSWI-SNF could remodel a tailless substrate. To prepare tailless mononucleosomes, donor polynucleosomes were subjected to a limited trypsin digest. Digestion was stopped through the addition of excess soybean trypsin inhibitor. These polynucleosomes were then used as donors in a histone octamer transfer reaction to assemble mononucleosomes on a defined, end-labeled, DNA fragment of 155 bp. Trypsinized nucleosomes used in the octamer transfer reaction are shown in Fig. 2A, lane 3, while tailed nucleosomes are shown in lane 2.

To ensure that the reconstitution procedure for the trypsinized mononucleosomes did not create an artifactual result, tailless templates were also prepared in a separate procedure in which glycerol gradient-purified labeled mononucleosomes (with tails) were directly subjected to trypsinization. Mobilities of these nucleosomes were compared on a 5% nondenaturing acrylamide gel. Figure 2B shows that nucleosomes trypsinized either after assembly of tailed nucleosomes (lane 2) or assembled using trypsinized donors with the histone octamer transfer reaction (lane 3) migrated identically and concomitantly faster than nucleosomes with tails (lane 1).

These substrates were then used in the mononucleosome DNase I accessibility assay. Incubation of tailed mononucleosomes with hSWI-SNF resulted in the characteristic ATP-dependent change in the DNase I cleavage pattern (Fig. 2C, lanes 4 and 5). Similar ATP-dependent changes were also seen with both preparations of trypsinized mononucleosomes (Fig. 2C, lanes 8, 9, 12, and 13). As such, all subsequent mononucleosome experiments used tailless mononucleosomes prepared with tailless polynucleosomes in the histone octamer transfer reaction.

As a second measure of hSWI-SNF activity on tailless mononucleosomes, we examined restriction enzyme accessibility. SWI-SNF has been reported previously to make nucleosomal DNA more accessible to cleavage by a restriction enzyme (35, 49, 56). We compared cleavage of an internal nucleosomal PstI site in the presence and absence of hSWI-SNF. The PstI site is located approximately 30 bp from the dyad axis and was selected since it showed the clearest hSWI-SNF effect (data not shown and reference 49). hSWI-SNF increased PstI cleavage of both the tailed and tailless mononucleosomes (Fig. 2D). While the background cleavage of PstI on tailless templates was significantly higher, templates both with and without tails showed reproducible increases in PstI cleavage in the presence of hSWI-SNF and ATP. Taken together, the experiments of Fig. 2 demonstrate that hSWI-SNF can remodel mononucleosomes with trypsin-cleaved N termini.

To examine the efficiency with which hSWI-SNF remodels tailed and tailless mononucleosomes, we performed the mononucleosome DNase I accessibility experiment with titrations of either the enzyme (hSWI-SNF) or the substrate (nucleosomes) and characterized the resultant ATP-dependent remodeling by examining changes in the DNase digestion pattern. We first titrated into the reaction mixture increasing amounts of hSWI-SNF (up to 150 ng) while keeping the total nucleosome concentration constant at 5.9 ng/25 μl (Fig. 3A). This titration experiment shows that tailed mononucleosomes were remodeled by hSWI-SNF more effectively than tailless mononucleosomes (compare lanes 8 and 20). Since this experiment contains relatively dilute equimolar concentrations of hSWI-SNF and nucleosomes, it does not address whether hSWI-SNF can remodel more than one tailless nucleosome in a multiple-turnover reaction. To test this, another experiment was performed to change the hSWI-SNF/nucleosome ratio by increasing the nucleosome concentration. This was done by keeping a constant concentration of hSWI-SNF (150 ng in 25 μl of reaction mixture) and a constant concentration of labeled tailed or tailless mononucleosomes (0.5 ng) and then increasing the amount of unlabeled tailed or tailless nucleosomes (up to 400 ng). Figure 3B shows that hSWI-SNF was able to efficiently remodel tailless mononucleosomes under conditions with excess nucleosomes to SWI-SNF (lane 14), although remodeling of tailless templates is less pronounced under high-substrate conditions (Fig. 3B, compare lanes 8 to 16). Both of these titration experiments (Fig. 3) suggest that hSWI-SNF remodels tailless mononucleosomes less efficiently than tailed mononucleosomes.

hSWI-SNF ATPase activity on tailless templates.

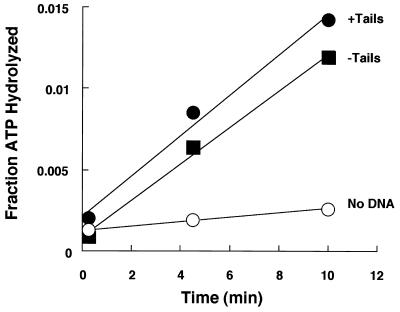

Although not previously reported for hSWI-SNF, yeast SWI-SNF has been shown to have a nucleosome-stimulated ATPase activity (16). We were interested in determining what effects, if any, removal of the tails would have, especially since it has been shown previously that removing the tails lowers the nucleosome-stimulated ATPase activity of the NURF chromatin-remodeling complex (20). Nucleosomal arrays were used as substrates in the reaction and were either prepared by digestion with trypsin as described above or mock treated in parallel reactions. The ability of these arrays to stimulate ATP-hydrolysis by hSWI-SNF was then measured. After various times of incubation of hSWI-SNF and nucleosomes, ATP and inorganic phosphate were separated by TLC and the amounts of each were quantified with a PhosphorImager. Both normal and trypsinized nucleosomes increased the rate of ATP hydrolysis by hSWI-SNF to a similar extent (Fig. 4). Thus, the tails are not required for stimulating the ATPase activity of hSWI-SNF.

FIG. 4.

ATPase activity in the presence of tailed and tailless polynucleosomes. The fraction of ATP hydrolyzed by hSWI-SNF in the presence of tailed (filled circles) and trypsinized (filled squares) nucleosomes is plotted. The background ATPase activity of hSWI-SNF without nucleosomes is also shown (open circles).

hSWI-SNF remodeling of trypsinized nucleosomal arrays.

The DNase I and restriction enzyme protocols shown in Fig. 2 and 3 measured remodeling activity on mononucleosomes. We also used arrays of nucleosomes as substrates for hSWI-SNF, both because these substrates are presumably more similar to in vivo chromatin than mononucleosomes and because histone N termini have been shown to have important effects on the biophysical properties of nucleosomal arrays (50). hSWI-SNF has been shown previously to cause significant changes in the topology of closed circular nucleosomal plasmids in an ATP-dependent reaction, resulting in a significant decrease in negative supercoiling (31, 51). We used this assay to test for effects of the histone tails.

Plasmids were assembled into nucleosomal arrays with either tailed histones or trypsinized histones by using a Xenopus heat-treated assembly extract (as described in Materials and Methods). This procedure (66) required free histones. To isolate trypsinized free histones, trypsinized nucleosomes were prepared from HeLa cells as described above, and then the tailless histones were separated from the DNA, trypsin, and inhibitor via hydroxyapatite chromatography (Fig. 5A). Control experiments showed that the assembled plasmids contained stoichiometric amounts of each of the respective trypsinized or tailed histones (data not shown).

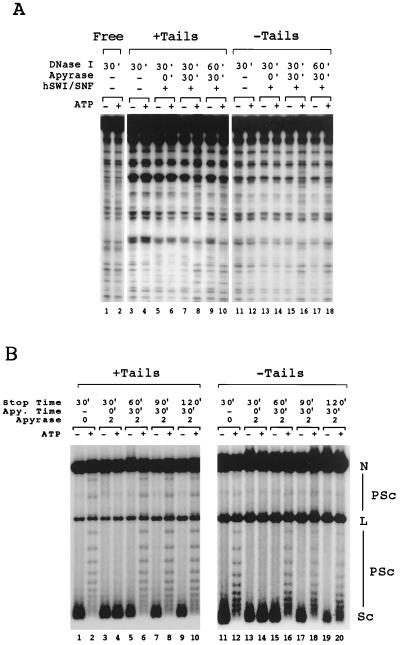

FIG. 5.

Remodeling of tailed and tailless nucleosomal arrays by hSWI-SNF. (A) SDS-PAGE analysis of trypsinized histones used in assembling tailless arrays. Lane 1, size standards (labeled in kilodaltons); lane 2, H1-depleted nucleosomes prior to trypsinization; lane 3, nucleosomes after trypsinization; lane 4, histones after hydroxyapatite chromatography. Tryp Inhib, trypsin inhibitor. (B) Plasmid supercoiling experiment comparing hSWI-SNF remodeling activity of nucleosomal arrays both with tails (+Tails) and without tails (−Tails). Molar ratios of hSWI-SNF to nucleosomes are indicated. N, nicked DNA; PSc, partially supercoiled DNA; L, linear DNA; Sc, supercoiled DNA; −, without ATP; +, with ATP.

The effect of hSWI-SNF on these nucleosomal plasmids was measured by following changes in topology. When closed circular nucleosomal DNA is relaxed by topoisomerase I and then deproteinized, each molecule of DNA contains one negative supercoil for every nucleosome. Incubation of a nucleosomal plasmid with hSWI-SNF and ATP changes the nature of the nucleosomes on the plasmid; this is reflected by a significant decrease in negative supercoils following topoisomerase I treatment and deproteinization (e.g., Fig. 5B, compare lanes 9 and 10).

Titration of hSWI-SNF into reaction mixtures with either normal or trypsinized arrays showed that hSWI-SNF was able to remodel both types of nucleosomal arrays in an ATP-dependent manner (Fig. 5B). To get similar degrees of remodeling, tailed arrays required three- to fourfold less hSWI-SNF than tailless arrays. We conclude that, like mononucleosomes, hSWI-SNF can remodel arrays of nucleosomes that do not contain tails, although these trypsinized arrays are remodeled less efficiently than their tailed counterparts.

Remodeled tailless mononucleosomes and nucleosomal arrays are stable in the absence of active remodeling.

The experiments described above show that hSWI-SNF can remodel nucleosomes that do not have histone N termini. All experiments were performed under conditions in which hSWI-SNF was continually active, and thus these experiments did not directly address whether the presence or absence of histone tails affects the stability of the remodeled state. Previous work had shown that hSWI-SNF-modified tailed templates maintain a remodeled state for an extended period after removal of ATP and/or dissociation from SWI-SNF (15, 24, 40). We first tested to see if the tailless remodeled state was stable in the absence of ATP. The assays used were the same as those described above, with the exception that after remodeling, ATP was removed with apyrase and the remodeled templates were incubated for various times before assaying for remodeling. Since SWI-SNF activity requires ATP, SWI-SNF is not active after the addition of apyrase (Fig. 6A, lanes 5 and 6; Fig. 6B, lanes 3 and 4). Without continued SWI-SNF remodeling, an unstable intermediate would return to the unremodeled state and be detected as such.

FIG. 6.

The stability of remodeled tailed (+Tails) and tailless (−Tails) templates. (A) DNase I mononucleosome disruption assays were performed at intervals (in minutes [indicated by prime mark]) following removal of ATP by apyrase. Lanes 1 and 2, naked DNA; lanes 3, 4, 11, and 12, no apyrase and no hSWI-SNF added; lanes 5, 6, 13, and 14, apyrase added at the same time as hSWI-SNF and incubated for 30 min before DNase I digestion; lanes 7, 8, 15, and 16, apyrase added after hSWI-SNF disruption, but just prior to DNase I digestion; lanes 9, 10, 17, and 18, hSWI-SNF disruption allowed to take place for 30 min, apyrase added, and sample reincubated at 30°C for 30 min before DNase I treatment. (B) Plasmid supercoiling assays were performed at intervals following the removal of ATP by 2 U of apyrase (Apy. Time). Lanes with tailed arrays contain 110 ng of hSWI-SNF, while lanes with tailless arrays contain 190 ng of hSWI-SNF. Lanes 1, 2, 11, and 12, normal hSWI-SNF disruption after 30 min; lanes 3, 4, 13, and 14, apyrase added at the same time as hSWI-SNF; lanes 5, 6, 15, and 16, hSWI-SNF disruption allowed to take place for 30 min, apyrase added, and sample reincubated for 30 min; lanes 7, 8, 17, and 18, hSWI-SNF disruption allowed to take place for 30 min, apyrase added, and sample reincubated for 60 min; lanes 9, 10, 19, and 20, hSWI-SNF disruption allowed to take place for 30 min, apyrase added, and sample reincubated for 90 min. N, nicked DNA; PSc, partially supercoiled DNA; L, linear DNA; Sc, supercoiled DNA; −, without ATP; +, with ATP.

The stability of the remodeled mononucleosome was tested with the DNase I accessibility assay. This experiment was performed by incubating hSWI-SNF, ATP, and end-labeled mononucleosomes for 30 min to allow for nucleosome remodeling, removing the ATP with 1 U of apyrase, and then reincubating the reaction mixture for an additional 30 min. The samples were then treated with DNase to determine if the remodeled state was maintained. One unit of apyrase is sufficient to deplete the ATP in the reaction mixture in less than 1 min and completely blocks remodeling when added at the same time as SWI-SNF (Fig. 6A, lanes 5, 6, 13, and 14). When apyrase was added after hSWI-SNF remodeling, but just before DNase I, both the tailed and tailless templates showed DNase I digestion patterns indicative of an SWI-SNF-modified nucleosome (Fig. 6A, lanes 8 and 16). When apyrase was added after remodeling and the reaction mixture was reincubated for 30 min before the addition of DNase I, the digestion pattern for both templates did not significantly change (Fig. 6A, compare lane 8 with 10 and lane 18 with 20). This indicates that the hSWI-SNF-modified state of these mononucleosomes is stable for at least 30 min regardless of the presence of the histone tails.

The stability of the remodeled tailless nucleosomes was also measured in the context of nucleosomal arrays by using the plasmid supercoiling experiment (Fig. 6B). Concentrations of hSWI-SNF that gave significant remodeling of either normal or trypsinized arrays were chosen (Fig. 6B, lanes 1, 2, 11, and 12). After the 30-min remodeling period, 2 U of apyrase was added and the reaction mixture was reincubated for an additional 30, 60, or 90 min (Fig. 6B, lanes 5 to 10 and 15 to 20). If the SWI-SNF-remodeled nucleosomes were unstable, they would return to the unremodeled state and regain the negative supercoiling lost during remodeling. Thirty minutes after the addition of apyrase, the SWI-SNF remodeling event was stable on both the trypsinized and normal nucleosomal arrays (lanes 5, 6, 15, and 16). After 90 min, though, the trypsinized template appeared to be returning toward a nonremodeled conformation (compare lanes 10 and 20).

Generation of a stable modified tailless mononucleosome.

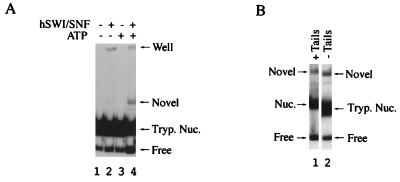

While the experiment in Fig. 6 shows that the remodeled state remained stable in the presence or absence of histone tails, it does not demonstrate the stability of the remodeled form when separated from hSWI-SNF. To address this, a nondenaturing acrylamide gel was run to detect a stable remodeled tailless nucleosome, similar to that seen previously for tailed mononucleosomes (49). When tailless mononucleosomes were incubated with hSWI-SNF and ATP for 55 min before competing away the bound hSWI-SNF with 1 μg of plasmid DNA, an ATP-enhanced SWI-SNF-dependent band was detected (Fig. 7A, lane 4). This novel species migrated slightly faster than the remodeled tailed conformation (Fig. 7B, compare lanes 1 and 2), which is consistent with the difference in mobility between the tailed and tailless substrates. As previously shown for the tailed mononucleosome (49), these data suggest that hSWI-SNF can also convert a tailless mononucleosome to a stable remodeled conformation.

FIG. 7.

Mobility shift of the trypsinized remodeled mononucleosome (Tryp. Nuc.). (A) Remodeling reactions (5 μl) were performed for 55 min in the presence (+) or absence (−) of ATP and hSWI-SNF before competing bound hSWI-SNF from the nucleosome with plasmid DNA. After a 15-min incubation with competitor, the reaction mixtures were loaded on a 4.5% acrylamide gel run in 0.5× TBE. Lane 4 shows the hSWI-SNF modified form of the tailless mononucleosomes (Novel). (B) Same as panel A, except that either tailed (lane 1) or tailless (lane 2) mononucleosomes were incubated with ATP and hSWI-SNF before separating on a 5% acrylamide gel run in 1× TBE.

DISCUSSION

The N-terminal tails are targets of histone acetylase (7, 30, 41, 48) and deacetylase (53, 67) complexes, are required for the function of the NURF chromatin-remodeling complex (20), and are believed to play an important role in repression by complexes such as the SIR complex (21). Thus, the tails frequently provide a key contact point for complexes that regulate chromatin and nucleosome structure. Our finding that the tails are not required for remodeling by hSWI-SNF both distinguishes this complex at a mechanistic level from these other complexes and raises the possibility that SWI-SNF complexes and complexes that require tails for function might be able to work together on the same nucleosome.

Remodeling by hSWI-SNF is currently believed to result from a conformational transition of the nucleosome that alters the path of the DNA as it wraps around the histones. This model is supported by observations that remodeled structures are stable in the absence of SWI-SNF contact, that remodeled nucleosomes contain the full complement of histones, and that a stable remodeled nucleosome product shows altered enzyme accessibility (36, 49). Although trypsinization does not remove the entire tail portion of the histones, the data presented here imply that the tails are not required to create this altered conformation.

The DNase I mononucleosome disruption data (Fig. 2 and 3) indicated that the path of the DNA around both the trypsinized and nontrypsinized mononucleosomes was similar. Without the tails, nucleosomes were still able to produce the characteristic 10-bp DNase I digestion pattern similar to that of tailed nucleosomes. After disruption, the DNase I patterns for both templates were remarkably similar. This implies that the DNA structure of the remodeled form is similar regardless of the status of the tails.

The remodeled structure can also be maintained in the absence of SWI-SNF on both trypsinized and nontrypsinized mononucleosomes as both substrates could form the stable modified species (Fig. 7). Stability of remodeling was also measured by removing ATP with apyrase and examining the stability of the remodeled state over time. Figure 6A shows that remodeled tailless mononucleosomes were stable in the absence of ATP for at least 30 min. Additionally, the plasmid supercoiling experiment (Fig. 6B) shows that while the trypsinized remodeled nucleosomal arrays were less stable, both the tailed and tailless templates remained in the remodeled configuration for over an hour. Thus, the tails are not required to maintain the disrupted conformation.

On mononucleosomes and arrays, hSWI-SNF was less active on trypsinized templates (Fig. 3 and 5). For the mononucleosome assays, however, less DNase (Fig. 2 and 3) and less PstI (Fig. 2) were required to cleave tailless nucleosomes than tailed nucleosomes. These and other physical characteristics of trypsinized nucleosomes have been shown previously to be different from those of tailed nucleosomes (2, 27, 33, 61). In particular, trypsinization has been shown to increase factor access towards nucleosomal DNA such that nucleases and transcription factors have greater effects on trypsinized nucleosomes. This is in contrast to remodeling by hSWI-SNF, which occurs more efficiently on nucleosomes with tails. One explanation for these observations is that SWI-SNF interacts with nucleosomes via a mechanism that is not inhibited by the histone tails and that therefore might differ from the mechanism via which other DNA-binding proteins contact the nucleosome.

Since hSWI-SNF does not require the histone tails for chromatin remodeling, what portion of the nucleosome might be contacted during SWI-SNF action? One possibility is that hSWI-SNF directly binds to the DNA and uses the energy of ATP hydrolysis to drive movement of the DNA in a manner that facilitates the transition between normal and remodeled nucleosome states (42). Unless hSWI-SNF has a method for accommodating the tails, this model could be argued against since the DNA of trypsinized nucleosomes is largely more accessible than that of tailed nucleosomes, yet the remodeling capability of hSWI-SNF is slightly less on tailless templates and the ATP hydrolysis rate remains the same. Alternatively, or in addition, SWI-SNF could directly contact portions of the core histone octamer to help facilitate this transition. The exposed histone tails, which are the most accessible protein component of the nucleosome, do not provide a necessary contact point for this reaction. Thus, if SWI-SNF requires direct interaction with nucleosomal proteins, it would be able to bind to the portions of the histones that constitute the core or that are immediately surrounded by DNA.

Many other regulatory complexes like histone acetylases and deacetylases require the tails for activity. It is possible that these complexes and SWI-SNF are able to work on the same nucleosome at the same time. In this light, it is interesting that histone deacetylases have been found to be associated with a DNA-dependent ATPase with homology to the SWI-SNF family (62) and that remodeling of nucleosome structure can facilitate histone deacetylation (56). A mechanism of this sort would clearly work more efficiently if the remodeling complex contacted different portions of the nucleosome than that required for deacetylase activity. Similar scenarios would allow remodeling complexes to work in close association with acetylation complexes. Genetic experiments have shown that components of the SAGA histone acetyltransferase complex in yeast have synthetic phenotypes with yeast SWI-SNF subunits (47), which is consistent with a concerted function of these complexes.

Finally, data presented here suggest that different complexes that remodel chromatin work by contacting different portions of the nucleosome. It has been shown previously that NURF requires the tails for remodeling activity (20), and we show that hSWI-SNF does not. This suggests that these complexes use different mechanisms to achieve the same activity. This may provide a clue as to what roles different chromatin-remodeling complexes play inside the cell.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank G. Schnitzler, M. Phelan, L. Corey, F. Raible, and other members of the laboratory for comments and C. Logie and C. Peterson for communicating unpublished data. We also thank M. Hirschel and J. Moquist from Cellex Biosciences, Minneapolis, Minn., for growing our cell lines.

This work was supported by grants from the NIH (to R.E.K. and S.S.) and the Damon Runyon-Walter Winchell Foundation (to G.J.N.).

Footnotes

This paper is dedicated to Veronica Blasquez in remembrance of her guidance, encouragement, and friendship.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allfrey V G, Faulkner R, Mirsky A E. Acetylation and methylation of histones and their possible role in the regulation of RNA synthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1964;51:786–794. doi: 10.1073/pnas.51.5.786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ausio J, Dong F, van Holde K E. Use of selectively trypsinized nucleosome core particles to analyze the role of the histone “tails” in the stabilization of the nucleosome. J Mol Biol. 1989;206:451–463. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(89)90493-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ausubel F M, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seidman J G, Smith J A, Struhl K, editors. Current protocols in molecular biology. New York, N.Y: Greene Publishing Associates/Wiley Interscience; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Böhm L, Crane-Robinson C. Proteases as structural probes for chromatin: the domain structure of histones. Biosci Rep. 1984;4:365–386. doi: 10.1007/BF01122502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bradbury E M. Reversible histone modifications and the chromosome cell cycle. Bioessays. 1992;14:9–16. doi: 10.1002/bies.950140103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown S A, Imbalzano A N, Kingston R E. Activator-dependent regulation of transcriptional pausing on nucleosomal templates. Genes Dev. 1996;10:1479–1490. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.12.1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brownell J E, Zhou J, Ranalli T, Kobayashi R, Edmondson D G, Roth S Y, Allis C D. Tetrahymena histone acetyltransferase A: a homolog to yeast Gcn5p linking histone acetylation to gene activation. Cell. 1996;84:843–851. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81063-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burns L G, Peterson C L. The yeast SWI-SNF complex facilitates binding of a transcriptional activator to nucleosomal sites in vivo. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:4811–4819. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.8.4811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cairns B R, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Winston F, Kornberg R D. Two actin-related proteins are shared functional components of the chromatin-remodeling complexes RSC and SWI/SNF. Mol Cell. 1998;2:639–651. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80162-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cairns B R, Kim Y-J, Sayre M H, Laurent B C, Kornberg R D. A multisubunit complex containing the SWI1/ADR6, SWI2/SNF2, SWI3, SNF5, and SNF6 gene products isolated from yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:1950–1954. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.5.1950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cairns B R, Levinson R S, Yamamoto K R, Kornberg R D. Essential role of Swp73p in the function of yeast Swi/Snf complex. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2131–2144. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.17.2131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cairns B R, Lorch Y, Li Y, Zhang M, Lacomis L, Erdjument B H, Tempst P, Du J, Laurent B, Kornberg R D. RSC, an essential, abundant chromatin-remodeling complex. Cell. 1996;87:1249–1260. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81820-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cao Y, Cairns B R, Kornberg R D, Laurent B C. Sfh1p, a component of a novel chromatin-remodeling complex, is required for cell cycle progression. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:3323–3334. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.6.3323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chiba H, Muramatsu M, Nomoto A, Kato H. Two human homologues of Saccharomyces cerevisiae SWI2/SNF2 and Drosophila Brahma are transcriptional coactivators cooperating with the estrogen receptor and the retinoic acid receptor. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:1815–1820. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.10.1815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Côté J, Peterson C L, Workman J L. Perturbation of nucleosome core structure by the SWI/SNF complex persists after its detachment, enhancing subsequent transcription factor binding. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:4947–4952. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.9.4947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Côté J, Quinn J, Workman J L, Peterson C L. Stimulation of GAL4 derivative binding to nucleosomal DNA by the yeast SWI/SNF complex. Science. 1994;265:53–60. doi: 10.1126/science.8016655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Côté J, Utley R T, Workman J L. Basic analysis of transcription factor binding to nucleosomes. Methods Mol Gen. 1995;6:108–128. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(96)74024-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dingwall A K, Beek S J, McCallum C M, Tamkun J W, Kalpana G V, Goff S P, Scott M P. The Drosophila snr1 and brm proteins are related to yeast SWI/SNF proteins and are components of a large protein complex. Mol Biol Cell. 1995;6:777–791. doi: 10.1091/mbc.6.7.777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Durrin L K, Mann R K, Kayne P S, Grunstein M. Yeast histone H4 N-terminal sequence is required for promoter activation in vivo. Cell. 1991;65:1023–1031. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90554-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Georgel P T, Tsukiyama T, Wu C. Role of histone tails in nucleosome remodeling by Drosophila NURF. EMBO J. 1997;16:4717–4726. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.15.4717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hecht A, Laroche T, Strahl-Bolsinger S, Gasser S M, Grunstein M. Histone H3 and H4 N-termini interact with SIR3 and SIR4 proteins: a molecular model for the formation of heterochromatin in yeast. Cell. 1995;80:583–592. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90512-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang L, Zhang W, Roth S Y. Amino termini of histones H3 and H4 are required for a1-α2 repression in yeast. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:6555–6562. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.11.6555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Imbalzano A N, Kwon H, Green M R, Kingston R E. Facilitated binding of TATA-binding protein to nucleosomal DNA. Nature. 1994;370:481–485. doi: 10.1038/370481a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Imbalzano A N, Schnitzler G R, Kingston R E. Nucleosome disruption by human SWI/SNF is maintained in the absence of continued ATP hydrolysis. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:20726–20733. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.34.20726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Imbalzano A N, Zaret K S, Kingston R E. Transcription factor (TF)IIB and TFIIA can independently increase the affinity of the TATA-binding protein for DNA. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:8280–8286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ito T, Bulger M, Pazin M J, Kobayashi R, Kadonaga J T. ACF, an ISWI-containing and ATP-utilizing chromatin assembly and remodeling factor. Cell. 1997;90:145–155. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80321-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Juan L-J, Utley R T, Adams C C, Vettese-Dadey M, Workman J L. Differential repression of transcription factor binding by histone H1 is regulated by the core histone amino termini. EMBO J. 1994;13:6031–6040. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06949.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kayne P S, Kim U-J, Han M, Mullen J R, Yoshizaki F, Grunstein M. Extremely conserved histone H4 N terminus is dispensible for growth but essential for repressing the silent mating loci in yeast. Cell. 1988;55:27–39. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90006-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Khavari P A, Peterson C L, Tamkun J W, Mendel D B, Crabtree G R. BRG1 contains a conserved domain of the SWI2/SNF2 family necessary for normal mitotic growth and transcription. Nature. 1993;366:170–174. doi: 10.1038/366170a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kleff S, Andrulis E D, Anderson C W, Sternglanz R. Identification of a gene encoding a yeast histone H4 acetyltransferase. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:24674–24677. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.42.24674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kwon H, Imbalzano A N, Khavari P A, Kingston R E, Green M R. Nucleosome disruption and enhancement of activator binding by a human SWI/SNF complex. Nature. 1994;370:477–481. doi: 10.1038/370477a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Laurent B C, Yang X, Carlson M. An essential Saccharomyces cerevisiae gene homologous to SNF2 encodes a helicase-related protein in a new family. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:1893–1902. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.4.1893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee D Y, Hayes J J, Pruss D, Wolffe A P. A positive role for histone acetylation in transcription factor access to nucleosomal DNA. Cell. 1993;72:73–84. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90051-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ling X, Harkness T A, Schultz M C, Fisher-Adams G, Grunstein M. Yeast histone H3 and H4 amino termini are important for nucleosome assembly in vivo and in vitro: redundant and position-independent functions in assembly but not in gene regulation. Genes Dev. 1996;10:686–699. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.6.686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Logie C, Peterson C L. Catalytic activity of the yeast SWI/SNF complex on reconstituted nucleosome arrays. EMBO J. 1997;16:6772–6782. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.22.6772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lorch Y, Cairns B R, Zhang M, Kornberg R D. Activated RSC-nucleosome complex and persistently altered form of the nucleosome. Cell. 1998;94:29–34. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81218-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Luger K, Mader A W, Richmond R K, Sargent D F, Richmond T J. Crystal structure of the nucleosome core particle at 2.8 Å resolution. Nature. 1997;389:251–260. doi: 10.1038/38444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Megee P C, Morgan B A, Mittman B A, Smith M M. Genetic analysis of histone H4: essential role of lysines subject to reversible acetylation. Science. 1990;247:841–845. doi: 10.1126/science.2106160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Muchardt C, Yaniv M. A human homologue of Saccharomyces cerevisiae SNF2/SWI2 and Drosophila brm genes potentiates transcriptional activation by the glucocorticoid receptor. EMBO J. 1993;12:4279–4290. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06112.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Owen-Hughes T, Utley R T, Côté J, Peterson C L, Workman J L. Persistent site-specific remodeling of a nucleosome array by transient action of the SWI/SNF complex. Science. 1996;273:513–516. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5274.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Parthun M R, Windom J, Gottschling D E. The major cytoplasmic histone acetyltransferase in yeast: links to chromatin replication and histone metabolism. Cell. 1996;87:85–94. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81325-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pazin M J, Bhargava P, Geiduschek E P, Kadonaga J T. Nucleosome mobility and the maintenance of nucleosome positioning. Science. 1997;276:809–812. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5313.809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Peterson C L, Dingwall A, Scott M P. Five SWI/SNF gene products are components of a large multiprotein complex required for transcriptional enhancement. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:2905–2908. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.8.2905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Peterson C L, Zhao Y, Chait B T. Subunits of the yeast SWI/SNF complex are members of the actin-related protein (ARP) family. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:23641–23644. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.37.23641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rhodes D, Laskey R A. Assembly of nucleosomes and chromatin in vitro. In: Wasserman P M, Kornberg R D, editors. Methods in enzymology. Vol. 170. San Diego, Calif: Academic Press; 1989. pp. 575–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Richmond E, Peterson C L. Functional analysis of the DNA-stimulated ATPase domain of yeast SWI2/SNF2. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:3685–3692. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.19.3685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Roberts S M, Winston F. Essential functional interactions of SAGA, a Saccharomyces cerevisiae complex of Spt, Ada and Gcn5 proteins, with the Snf/Swi, and Srb/mediator complexes. Genetics. 1997;147:451–465. doi: 10.1093/genetics/147.2.451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Roth S Y, Allis C D. Histone acetylation and chromatin assembly: a single escort, multiple dances? Cell. 1996;87:5–8. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81316-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schnitzler G, Sif S, Kingston R E. Human SWI/SNF interconverts a nucleosome between its base state and a stable remodeled state. Cell. 1998;94:17–27. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81217-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schwarz P M, Felthauser A, Fletcher T M, Hansen J C. Reversible oligonucleosome self-association: dependence on divalent cations and core histone tail domains. Biochemistry. 1996;35:4009–4015. doi: 10.1021/bi9525684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sif S, Stukenberg P T, Kirschner M W, Kingston R E. Mitotic inactivation of a human SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2842–2851. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.18.2842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tamkun J W, Deuring R, Scott M P, Kissinger M, Pattatucci A M, Kaufman T C, Kennison J A. brahma: a regulator of Drosophila homeotic genes structurally related to the yeast transcription activator SNF2/SWI2. Cell. 1992;68:561–572. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90191-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Taunton J, Hassis C A, Schreiber S L. A mammalian histone deacetylase related to the yeast transcriptional regulator Rpd3p. Science. 1996;272:408–411. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5260.408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Thompson J S, Ling X, Grunstein M. The histone H3 amino terminus is required for telomeric and silent mating locus repression in yeast. Nature. 1994;369:245–247. doi: 10.1038/369245a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Thorne A W, Kmiciek D, Mitchelson K, Sautiere P, Crane-Robinson C. Patterns of histone acetylation. Eur J Biochem. 1990;193:701–713. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1990.tb19390.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tong J K, Hassig C A, Schnitzler G R, Kingston R E, Schreiber S L. Chromatin deacetylation by an ATP-dependent nucleosome remodelling complex. Nature. 1998;395:917–921. doi: 10.1038/27699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tsukiyama T, Daniel C, Tamkun J, Wu C. ISWI, a member of the SWI2/SNF2 ATPase family, encodes the 140 kDa subunit of the nucleosome remodeling factor. Cell. 1995;83:1021–1026. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90217-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tsukiyama T, Wu C. Purification and properties of an ATP-dependent nucleosome remodeling factor. Cell. 1995;83:1011–1020. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90216-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Varga-Weisz P D, Wilm M, Bonte E, Dumas K, Mann M, Becker P B. Chromatin-remodelling factor CHRAC contains the ATPases ISWI and topoisomerase II. Nature. 1997;388:598–602. doi: 10.1038/41587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Verreault A, Kaufman P D, Kobayashi R, Stillman B. Nucleosome assembly by a complex of CAF-1 and acetylated histones H3/H4. Cell. 1996;87:95–104. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81326-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vettese-Dadey M, Walter P, Chen H, Juan L-J, Workman J L. Role of the histone amino termini in facilitated binding of a transcription factor, GAL4-AH, to nucleosome cores. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:970–981. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.2.970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wade P A, Jones P L, Vermaak D, Wolffe A P. A multiple subunit Mi-2 histone deacetylase from Xenopus laevis cofractionates with an associated Snf2 superfamily ATPase. Curr Biol. 1998;8:843–846. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70328-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wallis J W, Rykowski M, Grunstein M. Yeast histone H2B containing large amino terminus deletions can function in vivo. Cell. 1983;35:711–719. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90104-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wang W, Côté J, Xue Y, Zhou S, Khavari P A, Biggar S R, Muchardt C, Kalpana G V, Goff S P, Yaniv M, Workman J L, Crabtree G R. Purification and biochemical heterogeneity of the mammalian SWI-SNF complex. EMBO J. 1996;15:5370–5382. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang W, Xue Y, Zhou S, Kuo A, Cairns B R, Crabtree G R. Diversity and specialization of mammalian SWI/SNF complexes. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2117–2130. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.17.2117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Workman J L, Taylor I C A, Kingston R E, Roeder R G. Control of class II gene transcription during in vitro nucleosome assembly. Methods Cell Biol. 1991;35:419–447. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)60582-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yang W M, Inouye C, Zeng Y, Bearss D, Seto E. Transcriptional repression by YY1 is mediated by interaction with a mammalian homolog of the yeast global regulator RPD3. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:12845–12850. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.23.12845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]