Abstract

Objectives

Thromboinflammation, resulting from a complex interaction between thrombocytopathy, coagulopathy, and endotheliopathy, contributes to increased mortality in COVID-19 patients. MR-proADM, as a surrogate of adrenomedullin system disruption, leading to endothelial damage, has been reported as a promising biomarker for short-term prognosis. We evaluated the role of MR-proADM in the mid-term mortality in COVID-19 patients.

Methods

A prospective, observational study enrolling COVID-19 patients from August to October 2020. A blood sample for laboratory test analysis was drawn on arrival in the emergency department. The primary endpoint was 90-day mortality. The area under the curve (AUC) and Cox regression analyses were used to assess discriminatory ability and association with the endpoint.

Results

A total of 359 patients were enrolled, and the 90-day mortality rate was 8.9%. ROC AUC for MR-proADM predicting 90-day mortality was 0.832. An optimal cutoff of 0.80 nmol/L showed a sensitivity of 96.9% and a specificity of 58.4%, with a negative predictive value of 99.5%. Circulating MR-proADM levels (inverse transformed), after adjusting by a propensity score including eleven potential confounders, were an independent predictor of 90-day mortality (HR: 0.162 [95% CI: 0.043-0.480])

Conclusions

Our data confirm that MR-proADM has a role in the mid-term prognosis of COVID-19 patients and might assist physicians with risk stratification.

Keywords: Mid-regional proadrenomedullin, SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19, endotheliopathy, severity, second wave

Introduction

In December 2019, an outbreak of pneumonia due to a novel coronavirus, named severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), occurred in Wuhan (Hubei Province, China). The disease caused by this virus was called Coronavirus disease 19 (COVID-19), resulting in a pandemic affecting millions of people globally (Zhu et al., 2020).

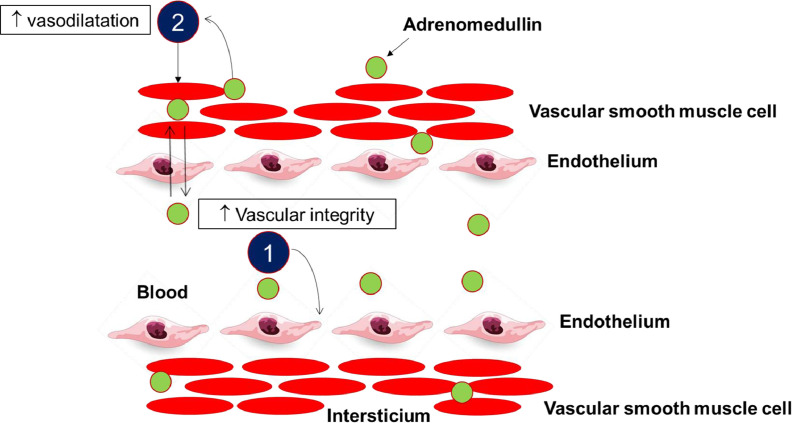

Emerging advances in understanding the pathophysiology of infection by SARS-COV-2 have been crucial to improving the treatment and management of COVID-19. The most severe forms of this disease are not limited to the respiratory system but is a multisystem syndrome in which the vascular endothelium is the primary damaged organ, characterized by inflammation and immunothrombosis within microvessels (Bonaventura et al., 2021; Pons et al., 2020; Kaur et al., 2020; Bernard et al., 2020). Because the vascular endothelium constitutes a cellular barrier playing a crucial role in the maintenance of vessel integrity, endothelial damage and dysfunction may also be prominent features of COVID-19 induced severe illness (Stein and Young, 2021; Wilson et al., 2020) endothelial biomarkers should be evaluated for their value in the risk stratification of COVID-19 patients (Evans et al., 2020). In this sense, adrenomedullin (ADM) is a key hormone secreted by endothelial and vascular smooth muscle cells, playing a role as an endothelial barrier function-stabilizing agent (Tay et al., 2020; van Lier et al., 2020) (Figure 1 ). Its blood levels are increased in severe infection as well as sepsis, and correlate with severity and mortality (Karpinich et al., 2011), being a helpful tool for risk stratification (Andaluz-Ojeda et al., 2017, Bernal-Morell et al., 2018, Cavallazzi et al., 2014, Saeed et al., 2019). Because endothelial dysfunction is one of the major hallmarks of COVID-19 (Libby and Lüscher, 2020), mid-regional-pro-adrenomedullin (MR-proADM), measured as a surrogate of adrenomedullin secretion (Morghentaler et al.; 2005), may be of interest as an indicator of COVID-19 induced endotheliitis (Wilson et al., 2020; Hupf et al., 2020).

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the mechanism of action of intravascular vs. interstitial ADM (adapted from Voors et al. 2019).

1. ADM present within the blood vessels improves vascular integrity and reduces vascular permeability

2. Adrenomedullin present in the interstitium acts on the vascular smooth muscle cells and causes dilatation of the vascular resistance and capacitance vessels.

Preliminary results in small scale studies, including patients in the first wave, suggest a potential role for MR-proADM regarding prognosis (García de Guadiana-Romualdo et al., 2021, Gregoriano et al., 2021, Montrucchio et al., 2021, Sozio et al., 2021), but these findings need confirmation in larger trials (Saeed et al., 2021). Of note, most of these studies focused on a short follow-up period to outcome (28/30 days) (García de Guadiana-Romualdo et al., 2021; Gregoriano et al., 2021). Finally, differences in the predictive accuracies of biomarkers as D-dimer or IL-6 between the first and second wave have been reported, reflecting a different disease stage of patients on arrival to the hospital (Mollinedo-Gajate et al., 2021) and a lower severity during the second wave (Fan et al., 2020), conditions both affecting to the accuracy of biomarkers.

In the present study, we aimed to evaluate the role of MR-proADM with regards to the prediction of severity in hospitalized patients by SARS-CoV-2 infection, focusing on a longer period after the index event (90 days), in a large cohort including patients in the second wave.

Material and methods

Study design and patient selection

This was a two-center prospective observational study recruiting consecutive adult (≥ 14 years) COVID-19 patients admitted to Reina Sofía University Hospital (Murcia, Spain) and Santa Lucía University Hospital (Cartagena, Spain) between September and October 2020, during the second wave in Spain. Infection by SARS-CoV-2 was diagnosed by a positive result of real-time reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction testing of a nasopharyngeal or lower respiratory tract specimen, according to WHO Guidelines (World Health Organization, 2020). Exclusion criteria were: (a) patients < 14 years; (b) pregnant women; (c) patients transferred from or to other hospitals and (d) lack of samples for the measurement of biomarkers. Only a first episode of admission to the hospital was considered for inclusion in the study.

The study protocol was approved by the local Ethics Committee of both hospitals and was performed under a waiver of informed consent and following the Declaration of Helsinki ethical guidelines.

Data collection

For eligible patients, clinical variables at admission and during the stay were extracted from electronic medical records. Admission variables were as follows: age, gender, SOFA score as an indicator for organ dysfunction, time from symptoms onset, the type of radiological pneumonia seen in chest X-ray or CT (absent, unilateral, or bilateral), comorbidities (hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus, obesity, current smoking, chronic kidney injury, cardiovascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, active cancer, liver disease, dementia, immunosuppression, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or other non-asthma respiratory diseases, asthma, and peptic ulcer), previous treatments (angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEi), angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB), non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, statins, immunosuppressors, systemic corticoids, and oral anticoagulants, including vitamin K antagonists and direct oral anticoagulants. In-hospital treatments were also recorded. Additionally, data from routine hematological, biochemical, and coagulation tests were collected from laboratory information systems.

Study endpoint

Ninety-day all-cause mortality following enrollment was the primary outcome. Patients were followed up from admission to 90 days after discharge or until death.

Blood sampling and laboratory analysis

In all patients, blood samples for biochemical analysis, including creatinine, albumin, bilirubin, C-reactive protein (CRP), procalcitonin and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), hematological analysis, including cell blood counts, and coagulation markers, including D-dimer, were drawn on arrival to the Emergency Department and results were made available according to clinical routine. For ferritin and interleukin-6 (IL-6), leftover serum was immediately frozen and stored at -80°C until testing. For the measurement of MR-proADM, blood samples collected in tubes containing EDTA K3 as anticoagulant were centrifuged at 2000 g for 10 min, and plasma was subsequently frozen and stored to -80°C until testing, according to stability results previously reported (Morgenthaler et al., 2005).

Plasma MR-proADM levels were measured by a homogeneous sandwich immunoassay with fluorescent detection using a time-resolved amplified cryptate emission (TRACE) technology assay (KRYPTOR® Gold, Brahms ThermoFisher Scientific Inc., Hennigsdorf, Berlin, Germany). According to the manufacturer's data, the detection limit, functional sensitivity, and quantification limit were 0.05 nmol/L, 0.23 nmol/L, and 0.25 nmol/L; intra-assay coefficient of variation (CV) and inter-assay CV were ≤ 10% and ≤ 20%, for a level ranging from 0.2 to 0.5 nmol/L, respectively.

Statistical analysis

The normality of continuous variables was tested by Kolmogorov-Smirnov or Shapiro-Wilk test, and they are reported as median (interquartile range [IQR]) or mean (standard deviation [SD]). Categorical variables are presented as frequency and percentage in each category. The Mann-Whitney U test and chi-squared test were used to compare continuous and categorical data between survivors and nonsurvivors as was the Kruskal-Wallis test and chi-squared test across quartiles of MR-proAMP and SOFA score on admission to the ED.

The discriminatory ability for 90-day mortality was evaluated by calculating the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC AUC). Youden's criterion was used to establish the optimal cutoff value, with sensitivity, specificity, negative and positive predictive values (NPV, PPV), negative and positive likelihood ratios (LR-, LR+) also reported. Furthermore, we validated the prognostic value of different reported MR-proADM cutoffs based on previous studies in other populations (Bernal-Morell et al., 2018, Saeed et al., 2019). Kaplan-Meier curves and log-rank tests were used to compare survival time stratified by an optimal cutoff.

We developed a full non-parsimonious logistic regression model to derive a propensity-score for the prediction of high circulating MR-proADM levels (above the median, 0.76 nmol/L) with eleven independent variables (age, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, obesity, COPD, CKD, cardiovascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, dementia and SOFA score). Our propensity score analysis attempted to compare outcomes for patients with COVID-19 that exhibited high vs. low MR-proADM levels, who had a similar distribution of measured covariates, and in this way approximated the condition of random assignment (Joffe and Rosenbaum, 1999). The C-statistic of the propensity score was 0.885 (95% CI 0.850–0.919). We then divided subjects into four equal-size groups using the quartiles of the estimated propensity score. Seven (1.9%) patients were excluded from multivariable and propensity scores analyses because of missing values. The independent effect of circulating MR-proADM levels was determined using the estimated regression coefficient from the fitted regression models; thus, we conducted adjusted analyses using Cox proportional hazard models, entering the propensity score as a covariate. MR-proADM was inverse-transformed before being entered into the Cox model, due to a non-gaussian distribution. The risk of the 90-day all-cause mortality was expressed as a hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). To test for consistency, CIs were calculated with a 3000-iterations bootstrapped method.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS vs. 22 (SPSS Inc) and MedCalc 15.0 (MedCalc Software).

Results

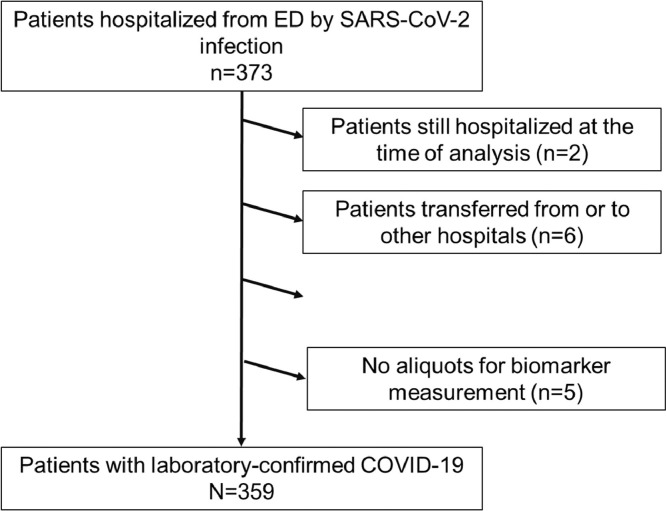

During the enrolment period, a total of 373 COVID-19 patients were recruited. Two patients were still hospitalized at the time of the analysis and therefore excluded from the data set. According to exclusion criteria, six patients transferred from or to other hospitals and one pregnant woman were excluded; in five cases, aliquots for biomarker analysis were not available. Finally, the study population included 359 hospitalized patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection, 197 from Santa Lucía University Hospital, and 162 from Reina Sofía University Hospital. Figure 2 provides an overview of the study flow.

Figure 2.

Flow chart of patient recruitment

Patients' characteristics and biomarkers stratified by the primary endpoint

Baseline characteristics in the overall cohort and stratified data according to 90-day mortality are summarized in Table 1 . Median age was 59 years (Interquartile range [IQR]: 47-71) and 64.1% (n=230) were male. The most prevalent comorbidities were hypertension (46.0%), obesity (n=240 [45.0%]) and diabetes mellitus (25.3%). Radiographic signs of infiltrates were recorded in 331 patients (92.2%) on chest X-rays at admission. In the overall cohort, 36.5% were on ACEI/ARBs and 31.5% on statins. Forty-three patients (12.0%) required invasive mechanical ventilation, 106 (29.5%) were admitted to ICU, and 32 (8.9%) died within the first 90 days of follow-up. Overall, patients hospitalized due to SARS-CoV-2 infection had a median length of hospital stay (LOS) of ten days (IQR: 6-17).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics in overall population and in groups according to 90-day mortality

| All patients n=359 | Survivors n=327 (91.1%) | Non-survivors n=32 (8.9%) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 59 (47-71) | 57 (46-68) | 76 (65-82) | <0.001 |

| Gender, male (n [%]) | 230 (64.1) | 209 (63.9) | 21 (65.6) | 0.847 |

| SOFA score, median (IQR) [n=352] | 2 (1-3) | 2 (1-2) | 3 (2-4) | <0.001 |

| SOFA score ≥ 2, n (%)[n=352] | 191 (54.3) | 162 (50.6) | 29 (90.6) | <0.001 |

| Time from symptom onset, median (IQR) | 7 (4-9) | 7 (5-9) | 6 (3-7) | 0.015 |

| Infiltrates on admission | 0.862 | |||

| Absents | 28 (7.8) | 26 (8) | 2 (6.3) | |

| Unilateral infiltrate | 78 (21.7) | 70 (21.4) | 8 (25.0) | |

| Bilateral infiltrates | 253 (70.5) | 231 (70.6) | 22 (68.8) | |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | ||||

| Hypertension | 165 (46) | 143 (43.7) | 22 (68.8) | 0.007 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 91 (25.3) | 73 (22.3) | 18 (56.3) | 0.001 |

| Obesity [n=240] | 108 (45.0) | 92 (42.4) | 16 (69.6) | 0.013 |

| COPD or non-asthma respiratory diseases | 54 (15.0) | 43 (13.1) | 11 (34.4) | 0.001 |

| Active smoker [n=345] | 15 (4.4) | 14 (4.4) | 1 (3.4) | 0.804 |

| Asthma | 17 (4.7) | 15 (4.6) | 2 (6.3) | 0.673 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 61 (17) | 50 (15.3) | 11 (34.4) | 0.006 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 45 (12.5) | 37 (11.3) | 8 (25.0) | 0.026 |

| Cancer | 7 (1.9) | 5 (1.5) | 2 (6.3) | 0.065 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 19 (5.3) | 16 (4.9) | 3 (9.4) | 0.280 |

| Dementia | 16 (4.5) | 11 (3.4) | 5 (15.6) | 0.001 |

| In-hospital treatments, n (%) | ||||

| Vasopressors or inotropic drugs | 15 (4.2) | 8 (2.4) | 7 (21.9) | <0.001 |

| Dialysis or hemofiltration | 5 (1.4) | 1 (0.3) | 4 (12.5) | <0.001 |

| Azithromycin | 120 (33.4) | 110 (33.6) | 10 (31.3) | 0.785 |

| Remdesivir | 92 (25.6) | 89 (27.2) | 3 (9.4) | 0.027 |

| Methylprednisolone and/or dexamethasone | 336 (93.6) | 304 (93) | 32 (100) | 0.121 |

| Tocilizumab | 59 (16.4) | 48 (14.7) | 11 (34.4) | 0.004 |

| Low heparin molecular weight | 350 (97.5) | 318 (97.2) | 32 (100) | 0.342 |

| Other antimicrobials | 164 (45.7) | 139 (42.5) | 25 (78.1) | <0.001 |

| Laboratory findings on admission to ED | ||||

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.99 (0.79-1.22) | 0.97 (0.78-1.18) | 1.34 (1.05-1.92) | <0.001 |

| Bilirubin (mg/dL), n=350 | 0.41 (0.30-0.60) | 0.41 (0.30-0.60) | 0.41 (0.33-0.55) | 0.931 |

| Albumin (g/dL), n=347 | 3.8 (3.4-4.2) | 3.9 (3.4-4.2) | 3.2 (3.0-3.6) | <0.001 |

| LDH (U/L) | 288 (234-372) | 286 (234-368) | 305 (234-408) | 0.532 |

| Ferritin (μg/L), n=352 | 441 (215-819) | 451 (222-810) | 391 (82-977) | 0.659 |

| CRP (mg/dL) | 7.49 (3.40-12.42) | 7.23 (3.33-12.08) | 8.21 (5.08-16.71) | 0.094 |

| Procalcitonin (μg/L), n=355 | 0.10 (0.06-0.17) | 0.09 (0.06-0.15) | 0.23 (0.18-0.43) | <0.001 |

| IL-6 (pg/mL) | 35.6 (19.2-65.6) | 34.8 (18.4-61.8) | 66.2 (38.9-129.5) | <0.001 |

| WBC count (*109/L) | 6.36 (4.90-8.30) | 6.40 (4.96-8.31) | 5.80 (4.25-7.85) | 0.283 |

| Neutrophil count (*109/L) | 4.70 (3.23-6.69) | 4.70 (3.23-6.70) | 4.45 (3.30-5.71) | 0.775 |

| Lymphocyte count (*109/L) | 1.07 (0.73-1.41) | 1.10 (0.79-1.43) | 0.90 (0.65-1.10) | 0.012 |

| NLR | 4.2 (2.7-7.8) | 4.2 (2.6-7.7) | 4.6 (3.5-8.7) | 0.196 |

| Platelet count (*109/L) | 197 (158-257) | 203 (162-261) | 167 (122-195) | <0.001 |

| D-dimer (ng/mL FEU), n=350 | 574 (351-966) | 572 (350-954) | 710 (482-1004) | 0.096 |

| MR-proADM (mmol/L) | 0.76 (0.57-1.15) | 0.73 (0.56-1.06) | 1.50 (0.98-2.31) | <0.001 |

| In-hospital LOS, median (IQR) | 10 (6-17) | 9 (6-16) | 18 (12-26) | <0.001 |

Abbreviations: IQR: Interquartile range; SOFA: Sequential Organ Failure Assessment; COPD: Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; LDH: Lactate dehydrogenase; CRP: C-reactive protein; IL-6: Interleukin 6; WBC: White blood cell; NLR: Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; MR-proADM: Mid-regional proadrenomedullin; ICU: Intensive Care Unit; LOS: Lenght of stay (days); ADRS: acute respiratory distress syndrome

During hospitalization, the most common complication was ARDS (45.4%), followed by liver (21.2%) and acute kidney injury (KDIGO stage 1 acute kidney injury or worse) (18.7%). In addition, 23 (6.4%) patients developed an episode of bacteremia. Concerning the in-hospital treatments, low molecular weight heparin, corticosteroids (methylprednisolone and/or dexamethasone), antimicrobials drugs (azithromycin or others), and remdesivir were frequently used (97.5%, 93.6%, 79.1%, and 25.6%, respectively).

Laboratory findings in the overall cohort and stratified according to survival status are summarized in Table 1. Creatinine, procalcitonin, IL-6, and MR-proADM were significantly higher and, in contrast, albumin and lymphocyte count significantly lower, in deceased patients. Median admission MR-proADM levels were two-fold higher in non-survivors compared to survivors (1.50 nmol/L [IQR: 0.98-2.31] vs. 0.73 nmol/L [IQR: 0.56-1.06]).

Patients' characteristics stratified by MR-proADM levels

The median level of MR-proADM in our cohort was 0.76 nmol/L (IQR: 0.57-1.15 nmol/L). When patients were stratified according to MR-proADM quartiles (Supplementary Table 1), those with higher levels upon admission were older and had a higher rate of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, obesity, cardiovascular disease, chronic kidney disease, and dementia. All-cause 90-day mortality increased significantly from the first quartile (n=0) to the fourth quartile (n=20 [22.2%]).

Association of MR-proAMP with disease severity on admission

SOFA, as an indicator of severity on arrival to the ED, was calculated in 352 patients (98%) and was significantly associated with higher concentrations of MR-proANP, ranging from 0.63 nmol/L (IQR: 0.50-0.83) in patients with SOFA < 2 to 2.28 (IQR: 1.22-3.91) in patients with SOFA ≥ 7 (Figure 3 ).

Figure 3.

MR-proADM levels stratified according to disease severity (SOFA) on admission. Abbreviations: SOFA: Sequential Organ Failure Assessment. * p-value < 0.001. The box represents the 25th and 75th percentiles, and the whiskers are the upper and lower adjacent values; one outlier of 11.13 nmol/L in the SOFA 2-6 group was removed for visual presentation; n = 352

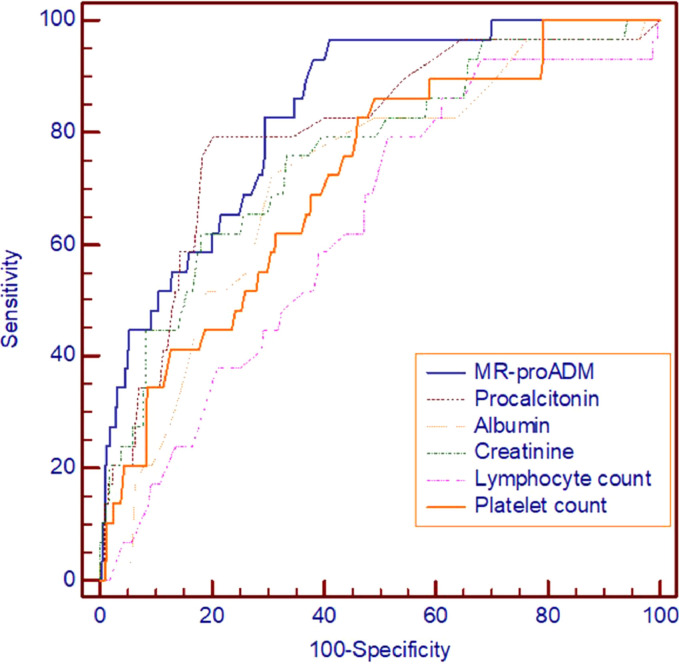

Receiver operating curves for prediction of 90-day mortality by MR-proADM and other biomarkers and Kaplan-Meier analysis

Concerning predictive ability, circulating levels of MR-proADM showed the highest discrimination ability for 90-day mortality (ROC AUC: 0.832; 95% [CI]: 0.770-0.894) (Table 2 and Figure 4 ), although a significant difference was not detected in comparison to procalcitonin (ROC AUC: 0.795; 95% CI: 0.716-0.874) (Table 2). According to the Youden Index, we found an optimal cut-off at 0.80 nmol/L, with a sensitivity of 96.9% (95% CI: 83.8-99.9%) and a specificity of 58.4% (95% CI: 52.9-63.8%) yielding a very high negative predictive value of 99.5% (95% CI: 97.1-100%). When higher cutoffs were analyzed, such as 1.54 and 1.8 nmol/L, a higher specificity was reached, as expected, but with positive predictive values below 40% (Table 3 ). MR-proADM achieved a similar accuracy (ROC AUC; 0.832; 95%CI: 0.763-0.901; p<0.001) when short-term (30 day) mortality was taken as the endpoint.

Table 2.

ROC curve and AUC analysis for 90-day mortality prediction

| Biomarker | ROC AUC, 95% CI | p-value of comparison vs. MR-proADM |

|---|---|---|

| MR-proADM | 0.832 (0.770-0.894; p<0.001) | - |

| Procalcitonin | 0.795 (0.716-0.874; p<0.001) | 0.349 |

| Creatinine | 0.751 (0.660-0.842; p<0.001) | 0.046 |

| Albumin | 0.712 (0.618-0.806; p<0.001) | 0.010 |

| Platelet count | 0.698 (0.605-0.791; p<0.001) | 0.031 |

| IL-6 | 0.689 (0.591-0.788; p<0.001 | 0.008 |

| Lymphocyte count | 0.634 (0.542-0.726; p<0.001) | <0.001 |

Only biomarker levels or blood cell counts with a significant ROC AUC were included in this table

Abbreviations: ROC: Receiver Operating Characteristics; AUC: Area under the curve; CI: Confidence interval; MR-proADM: Mid-regional proadrenomedullin; IL-6: Interleukin 6

Figure 4.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves for prediction of primary 90-day mortality

Table 3.

Accuracy of biomarkers for predicting in-hospital mortality

| Biomarker | Cutoff (nmol/L) | S (95% CI) | Sp (95% CI) | LR (-) (95% CI) | LR (+) (95% CI) | PPV (95% CI) | NPV (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MR-proADM | >0.801 | 96.9 (83.8-99.9) | 58.4 (52.9-63.8) | 0.05 (0.01-0,4) | 2.3 (2.1-2.6) | 18.6 (13.0-25.3) | 99.5 (97.1-100) |

| <0.872 | 87.5 (71.0-96.5) | 64.2 (58.8-69.4) | 0.19 (0.08-0.5) | 2.5 (2.1-2.9) | 19.3 (13.2-26.7) | 98.1 (95.3-99.5) | |

| ≥1.542 | 50.0 (31.9-68.1) | 89.3 (85.4-92.4) | 0.6 (0.4-0.9) | 4.7 (3.3-6.6) | 31.4 (19.0-46.0) | 94.8 (91.7-97.0) | |

| ≤0.603 | 96.9 (83.8-99.9) | 30.3 (25.3-35.6) | 0.10 (0.01-0.7) | 1.4 (1.2-1.7) | 12.2 (8.4-16.8) | 99.0 (94.8-100) | |

| >1.83 | 43.8 (26.4-62.3) | 93.3 (90.0-95.7) | 0.6 (0.4-1.0) | 6.5 (4.4-9.6) | 38.9 (22.9-56.8) | 94.4 (91.3-96.7) |

Abbreviations: S: Sensitivity; Sp: Specificity; LR: Likelihood ratio; PPV: positive predictive value; NPV: Negative predictive value; CI: Confidence interval: MR-proADM: Mid-regional proadrenomedullin

Optimal cutoff according to Index Youden

Recommended cutoffs by Saaed et al., 2019 and Saeed et al., 2021

Recommended cutoffs by Bernal-Morell et al., 2018

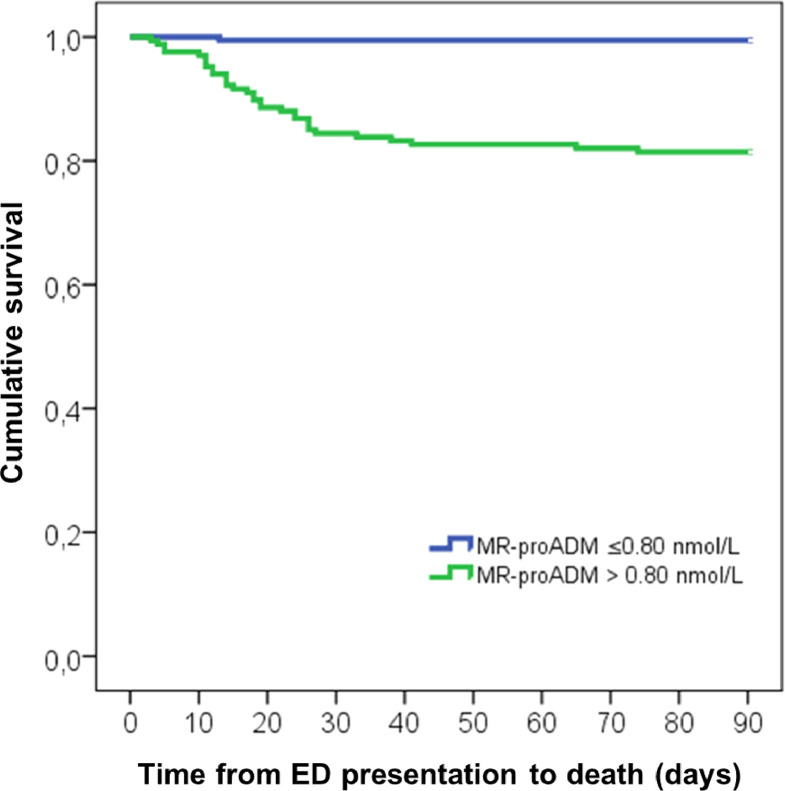

Kaplan-Meier curves using the optimized MR-proADM cut-off identified a higher mortality (18.6% vs. 0.5%; p<0.001) in patients with MR-proADM > 0.80 (n=167) in comparison to those with a MR-proADM ≤ 0.80 nmol/L (n=192) (Figure 5 ).

Figure 5.

Cumulative incidence of 90-day mortality stratified according to optimal cutoff for MR-proADM

Association of MR-proADM with 90-day mortality

In regression analyses, after adjusting by a propensity score, inverse transformed MR-proADM levels showed an independent association with the study endpoint (HR:0.162 [95% CI: 0.043-0.480]; p=0.002).

Discussion

Recent research into the underlying mechanisms of coronavirus-mediated diseases suggests that a complex interaction between coagulopathy, thrombocytopathy, and endotheliopathy contribute to COVID-19-associated thromboinflammation, a significant cause of morbidity and mortality in infected patients by SARS-CoV-2 (Gu et al., 2021). Furthermore, those features are associated with cardiovascular risk factors such as diabetes mellitus, obesity, and aging, conditions reported as predictors for a poorer evolution (Ssentongo et al., 2020; Bermejo-Martín et el., 2020). Hence, the combination of cardiovascular risk factors and infection by SARS-Cov-2 leads to exacerbated thrombosis and increased mortality (Gu et al., 2021).

Because identifying early factors related to COVID-19 severity could provide valuable information about the appropriate clinical care for these patients as well as the allocation of health resources, the characterization of endothelial damage by the measurement of endothelial biomarkers may help to enable stratification of COVID-19 patients with the highest pro-thrombotic risk (Evans et al., 2020]. Although several studies have reported the biochemical evidence of endothelial dysfunction (Goshua et al., 2020; Pine et al., 2020) in COVID-19 patients, the methodologies used are cumbersome and not applicable for its implementation as a STAT laboratory test. In this sense, the automated measurement of MR-proADM, as a surrogate of ADM activity, which plays a key role in reducing vascular (hyper) permeability and promoting endothelial stability and integrity following severe infection, could be of interest to characterize COVID-19 induced endothelial damage (Wilson et al., 2020).

This prospective study aimed to analyze the value of MR-proADM as a surrogate biomarker of ADM activity for predicting mid-term mortality in confirmed COVID-19 patients during the second wave of the pandemic. The main findings were: (1) MR-proADM was the biomarker with the highest performance for predicting 90-day mortality; (2) a low MR-proADM level (0.80 nmol/L) showed a very high negative predictive value to rule-out mid-term mortality, which might contribute to decision-making by clinicians in combination with the clinical evaluation; (3) after adjusting by a propensity score, including eleven variables, MR-proADM was an independent predictor for mid-term mortality; and (4) similar to other studies recently published (García de Guadiana-Romualdo et al., 2021; Gregoriano et al., 2021), MR-proADM was also the biomarker with the highest prognostic accuracy for short-term mortality.

The prognostic value of MR-proADM has been previously reported in non-infectious diseases, such as acute pulmonary embolism (Öner et al., 2020), heart failure (Maisel et al., 2010) and myocardial infarction (Horiuchi et al., 2020), and also in infectious diseases, including acquired community pneumonia (Huang et al., 2009; Legramante et al., 2017), independently of its etiology (Bello et al., 2012), and independently of sepsis (Bernal-Morell et al.; 2018; Charles et al., 2017; Andaluz-Ojeda et al.; 2017). MR-proADM has been shown to be a useful tool to assess the overall severity of the host response; hence, it could accurately identify infected patients requiring admission into the ICU (Baldirà et al.; 2020) and the likelihood of further disease progression in patients with suspected infection presenting to the ED, to either initiate, escalate or intensify early treatment strategies, or identify patients suitable for safe outpatient treatment (Saeed et al.; 2019). Fewer studies have evaluated the prognostic role of MR-proADM in viral infections, mainly by the influenza virus, and the results reported are controversial, with ROC AUC ranging from 0.68 for a composite of death, ICU admission, and prolonged stay (Valero Cifuentes et al., 2019) to 0.871 for mortality (Valenzuela Sánchez et al., 2015).

Regarding COVID-19, several studies have studied the potential role of MR-proADM for the prognosis of short-term mortality (García de Guadiana-Romualdo et al., 2021; Gregoriano et al., 2021; Montrucchio et al., 2021), progression to severe disease (García de Guadiana et al., 2021; Sozio et al., 2021) and requirement of renal replacement therapy in critically ill patients (Roedl et al., 2021). The main limitations in these studies are the small sample size and the inclusion of patients recruited in the first wave, in which the role of laboratory tests has been recently disputed, with differences in the prognostic value of some thromboinflammation markers in comparison to the first wave. Noteworthy, in our study, differences between survivors and nonsurvivors for D-dimer or CRP were not detected, as Mollinedo-Gajate et al. reported (Mollinedo-Gajate et al., 2021). Furthermore, most of these studies focused on a short follow-up period (28/30 days) from ED admission to the endpoint. Although 28 or 30-day mortality is an outcome commonly used in studies in ED to evaluate the impact of an intervention on patients, COVID-19 patients, particularly those admitted to ICU, have required a prolonged hospital length of stay, so death could occur after 30 days from arrival to ED (González del Castillo, 2021).

Results of our study, including a cohort of 359 patients recruited during the second wave in two Spanish hospitals, confirm that MR-proADM levels may help to identify the risk for a poor outcome in patients presenting to the ED. Notably, and due to a elevated negative predictive value close to 100%, associated with the chosen optimal cutoff (0.8 nmol/L), low MR-proADM levels would allow recognizing patients with low mortality risk who could benefit from less intensive treatment. This finding, also reported by Gregoriano et al. (2021), opens the possibility for new studies evaluating the role of MR-proADM for a safe discharge from ED for outpatient management (Saeed et al., 2021). Similar to previous studies (García de Guadiana-Romualdo et al., 2021; Gregoriano et al., 2021), MR-proADM was the biomarker with the highest prognostic accuracy for short-term (30-day) mortality (ROC AUC: 0.832) and mid-term (90-day) mortality, although without a significant difference in comparison to procalcitonin (ROC AUC: 0.795), a bacterial infection biomarker, for this second outcome. Unfortunately, the presence of bacterial co-infection on arrival in the ED was not recorded in this study, and therefore it could not be excluded. It is unclear that the reported low co-infection rate is the result of large scale empirical antimicrobial administration or the limitation of the overwhelmed microbiological tests in health systems during the pandemic (Chang et al., 2020). Finally, multivariate analysis showed the value of MR-proADM as an independent predictor for 90-day mortality (HR for inverse transformed MR-proADM: 0.162 [95% CI: 0.043-0.480; p=0.002]) even after a bootstrap replication with 3000-iterations. Our results confirm the association of endothelial damage, characterized by MR-proADM levels, with COVID-19 severity.

Although this is the study with a larger sample size evaluating the role of MR-proADM for prognosis of severity in COVID-19 patients, it has some limitations. First, only one measurement of MR-proADM on arrival to ED was performed, and the impact of serial measurements was not evaluated. However, a single determination has been sufficient to reliably predict the evolution of these patients in both the short and mid-term. Second, other biomarkers previously reported as predictors of severity, such as troponin (Wibowo et al., 2021), were not measured. However, the European Society of Cardiology discouraged its routine measurement in COVID-19 because it concludes that it is unlikely that cardiac troponin provides incremental value to other strong predictors of death (The European Society of Cardiology., 2020).

In conclusion, our study confirms that MR-proADM levels, measured on arrival to the ED, have a potential role in establishing the prognosis of patients infected by SARS-CoV-2 requiring hospital admission. Low MR-proADM levels might assist physicians in the early identification of low-risk patients with a high probability of survival in clinical decision-making.

Acknowledgments

Funding

ThermoFisher Scientific, BRAHMS, Henningsdorf (Germany) supported the study by providing reagents and other materials for the measurement of MR-proADM. ThermoFisher Scientific, BRAHMS, did not participate in the manuscript's study design, data collection, and analysis or writing.

Conflict of interest

The authors state no conflict of interest.

Author contributions

EGB and LGGR designed the study, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. LCS provided statistical advice. PET and NSR measured MR-proADM in plasma samples. MMM, MJA, AA, CBPC, CTJ, MDRM, MHO, MGM, VCR, ACH, PPS and MSRB contributed to the enrollment of patients and clinical data collection. PET, NSR, and VRA managed the laboratory investigations. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript. All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2021.08.058.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- Andaluz-Ojeda D, Nguyen HB, Meunier-Beillard N, Cicuéndez R, Quenot JP, Calvo D. Superior accuracy of mid-regional proadrenomedullin for mortality prediction in sepsis with varying levels of illness severity. Ann Intensive Care. 2017;7(1):15. doi: 10.1186/s13613-017-0238-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldirà J, Ruiz-Rodríguez JC, Wilson DC, Ruiz-Sanmartin A, Cortes A, Chicano L. Biomarkers and clinical scores to aid the identification of disease severity and intensive care requirement following activation of an in-hospital sepsis code. Ann Intensive Care. 2020;10(1):7. doi: 10.1186/s13613-020-0625-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bello S, Lasierra AB, Mincholé E, Fandos S, Ruiz MA, Vera E, de Pablo F, Ferrer M, Menendez R, Torres A. Prognostic power of proadrenomedullin in community-acquired pneumonia is independent of aetiology. Eur Respir J. 2012;39(5):1144–1155. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00080411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bermejo-Martin JF, Almansa R, Torres A, González-Rivera M, Kelvin DJ. COVID-19 as a cardiovascular disease: the potential role of chronic endothelial dysfunction. Cardiovasc Res. 2020;116(10):e132–e133. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvaa140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernal-Morell E, García-Villalba E, Vera MDC, Medina B, Martinez M, Callejo V. Usefulness of midregional pro-adrenomedullin as a marker of organ damage and predictor of mortality in patients with sepsis. J Infect. 2018;76(3):249–257. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2017.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard I, Limonta D, Mahal LK, Hobman TC. Endothelium infection and dysregulation by SARS-CoV-2: evidence and caveats in COVID-19. Viruses. 2020;13(1):29. doi: 10.3390/v13010029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonaventura A, Vecchié A, Dagna L, Martinod K, Dixon DL, Van Tasell BW. Endothelial dysfunction and immunothrombosis as key pathogenic mechanisms in COVID-19. Nat Rev Immunol. 2021 Apr 6 doi: 10.1038/s41577-021-00536-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavallazzi R, El-Kersh K, Abu-Atherah E, Singh S, Loke YK, Wiemken T, Ramirez J. Midregional proadrenomedullin for prognosis in community-acquired pneumonia: a systematic review. Respir Med. 2014;108(11):1569–1580. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2014.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang CY, Chan KG. Underestimation of co-infections in COVID-19 due to non-discriminatory use of antibiotics. J Infect. 2020;81(3):e29–e30. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.06.077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans PC, Rainger GE, Mason JC, Guzik TJ, Osto E, Stamataki Z. Endothelial dysfunction in COVID-19: a position paper of the ESC working group for Atherosclerosis and Vascular Biology, and the ESC council of basic Cardiovascular Science. Cardiovasc Res. 2020;116(14):2177–2184. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvaa230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan G, Yang Z, Lin Q, Zhao S, Yang L, He D. Decreased case fatality rate of COVID-19 in the second wave: a study in 53 countries or regions. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2020;6 doi: 10.1111/tbed.13819. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García de Guadiana-Romualdo L, Calvo Nieves MD, Rodríguez Mulero MD, Calcerrada Alises I, Hernández Olivo M, Trapiello Fernández W. MR-proADM as marker of endotheliitis predicts COVID-19 severity. Eur J Clin Invest. 2021;11:e13511. doi: 10.1111/eci.13511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González del Castillo J. Keys to interpreting predictive models for the patient with COVID-19. Emergencias. 2021;33 [Epub ahead of print] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goshua G, Pine AB, Meizlish ML, Chang CH, Zhang H, Bahel P. Endotheliopathy in COVID-19-associated coagulopathy: evidence from a single-centre, cross-sectional study. Lancet Haematol. 2020;7(8):e575–e582. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(20)30216-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregoriano C, Koch D, Kutz A, Haubitz S, Conen A, Bernasconi L. The vasoactive peptide MR-pro-adrenomedullin in COVID-19 patients: an observational study. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2021;8 doi: 10.1515/cclm-2020-1295. cclm-2020-1295Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu SX, Tyagi T, Jain K, Gu VW, Lee SH, Hwa JM. thrombocytopathy and endotheliopathy: crucial contributors to COVID-19 thromboinflammation. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2021;18(3):194–209. doi: 10.1038/s41569-020-00469-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horiuchi Y, Wettersten N, Patel MP, Mueller C, Neath SX, Christenson RH. Biomarkers enhance discrimination and prognosis of type 2 myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2020;142(16):1532–1544. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.046682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang DT, Angus DC, Kellum JA, Pugh NA, Weissfeld LA, Struck J. Midregional proadrenomedullin as a prognostic tool in community-acquired pneumonia. Chest. 2009;136(3):823–831. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hupf J, Mustroph J, Hanses F, Evert K, Maier LS, Jungbauer CG. RNA-expression of adrenomedullin is increased in patients with severe COVID-19. Crit Care. 2020;24(1):527. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-03246-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joffe MM, Rosenbaum PR. Invited commentary: propensity scores. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;150(4):327–333. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a010011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karpinich NO, Hoopes SL, Kechele DO, Lenhart PM, Caron KM. Adrenomedullin function in vascular endothelial cells: insights from genetic mouse models. Curr Hypertens Rev. 2011;7(4):228–239. doi: 10.2174/157340211799304761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur S, Tripathi DM, Yadav A. The enigma of endothelium in COVID-19. Front Physiol. 2020;11:989. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2020.00989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legramante JM, Mastropasqua M, Susi B, Porzio O, Mazza M, Miranda Agrippino G. Prognostic performance of MR-pro-adrenomedullin in patients with community-acquired pneumonia in the Emergency Department compared to clinical severity scores PSI and CURB. PLoS One. 2017;12(11) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0187702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Libby P, Lüscher T. COVID-19 is, in the end, an endothelial disease. Eur Heart J. 2020;41(32):3038–3044. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maisel A, Mueller C, Nowak R, Peacock WF, Landsberg JW, Ponikowski P. Mid-region pro-hormone markers for diagnosis and prognosis in acute dyspnea: results from the BACH (Biomarkers in Acute Heart Failure) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55(19):2062–2076. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mollinedo-Gajate I, Villar-Álvarez F, Zambrano-Chacón MLÁ, Núñez-García L, de la Dueña-Muñoz L, López-Chang C. First and second waves of Coronavirus disease 2019 in Madrid, Spain: clinical characteristics and hematological risk factors associated With critical/fatal Illness. Crit Care Explor. 2021;3(2):e0346. doi: 10.1097/CCE.0000000000000346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montrucchio G, Sales G, Rumbolo F, Palmesino F, Fanelli V, Urbino R. Effectiveness of mid-regional pro-adrenomedullin (MR-proADM) as prognostic marker in COVID-19 critically ill patients: An observational prospective study. PLoS One. 2021;16(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0246771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgenthaler NG, Struck J, Alonso C, Bergmann A. Measurement of midregional proadrenomedullin in plasma with an immunoluminometric assay. Clin Chem. 2005;51(10):1823–1829. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2005.051110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Öner Ö, Deveci F, Telo S, Kuluöztürk M, Balin M. MR-proADM and MR-proANP levels in patients with acute pulmonary embolism. J Med Biochem. 2020;39(3):328–335. doi: 10.2478/jomb-2019-0049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pine AB, Meizlish ML, Goshua G, Chang CH, Zhang H, Bishai J. Circulating markers of angiogenesis and endotheliopathy in COVID-19. Pulm Circ. 2020;10(4) doi: 10.1177/2045894020966547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pons S, Fodil S, Azoulay E, Zafrani L. The vascular endothelium: the cornerstone of organ dysfunction in severe SARS-CoV-2 infection. Crit Care. 2020;24(1):353. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-03062-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roedl K, Jarczak D, Fischer M, Haddad M, Boenisch O, de Heer G. MR-proAdrenomedullin as predictor of renal replacement therapy in a cohort of critically ill patients with COVID-19. Biomarkers. 2021;23:1–20. doi: 10.1080/1354750X.2021.19044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saeed K, Legramante JM, Angeletti S, Curcio F, Miguens I, Poole S. Mid-regional pro-adrenomedullin as a supplementary tool to clinical parameters in cases of suspicion of infection in the Emergency Department. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2021 doi: 10.1080/14737159.2021.1902312. Mar 19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saeed K, Wilson DC, Bloos F, Schuetz P, van der Does Y, Melander O. The early identification of disease progression in patients with suspected infection presenting to the emergency department: a multi-centre derivation and validation study. Crit Care. 2019;23(1):40. doi: 10.1186/s13054-019-2329-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sozio E, Tascini C, Fabris M, D'Aurizio F, De Carlo C, Graziano E. MR-proADM as prognostic factor of outcome in COVID-19 patients. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):5121. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-84478-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ssentongo P, Ssentongo AE, Heilbrunn ES, Ba DM, Chinchilli VM. Association of cardiovascular disease and 10 other pre-existing comorbidities with COVID-19 mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2020;15(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0238215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein RA, Young LM. From ACE2 to COVID-19: A multiorgan endothelial disease. Int J Infect Dis. 2021;100:425–430. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.08.083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tay MZ, Poh CM, Rénia L, MacAry PA, Ng LFP. The trinity of COVID-19: immunity, inflammation and intervention. Nat Rev Immunol. 2020;20(6):363–374. doi: 10.1038/s41577-020-0311-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The European Society for Cardiology. ESC Guidance for the Diagnosis and Management of CV Disease during the COVID-19 Pandemic. https://www.escardio.org/Education/COVID-19-and-Cardiology/ESC-COVID-19-Guidance. (Last update: 10 June 2020).

- van Lier D., Kox M., Pickkers P. Promotion of vascular integrity in sepsis through modulation of bioactive adrenomedullin and dipeptidyl peptidase 3. J Intern Med. 2021;289(6):792–806. doi: 10.1111/joim.13220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valenzuela Sanchez F, Valenzuela Mendez B, Rodríguez Gutierrez JF, Bohollo de Austria R, Rubio Quiñones J, Puget Martínez L. Initial levels of mr-proadrenomedullin: a predictor of severity in patients with influenza a virus pneumonia. Intensive Care Med Exp. 2015;3(Suppl 1):A832. doi: 10.1186/2197-425X-3-S1-A832. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Valero Cifuentes S, García Villalba E, Alcaraz García A, Alcaraz García MJ, Muñoz Pérez Á, Piñera Salmerón P. Prognostic value of pro-adrenomedullin and NT-proBNP in patients referred from the emergency department with influenza syndrome. Emergencias. 2019;31(3):180–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voors AA, Kremer D, Geven C, Ter Maaten JM, Struck J, Bergmann A. Adrenomedullin in heart failure: pathophysiology and therapeutic application. Eur J Heart Fail. 2019;21:163–171. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.1366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wibowo A, Pranata R, Akbar MR, Purnomowati A, Martha JW. Prognostic performance of troponin in COVID-19: a diagnostic meta-analysis and meta-regression. Int J Infect Dis. 2021;105:312–318. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2021.02.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson DC, Schefold JC, Baldirà J, Spinetti T, Saeed K, Elke G. Adrenomedullin in COVID-19 induced endotheliitis. Crit Care. 2020;24(1):411. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-03151-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Laboratory testing for coronavirus disease (COVID-19) in suspected human cases. https://www.who.int/publications-detail/laboratory-testing-for-2019-novel-coronavirus-insuspected-human-cases-20200117. [Accessed 25 August 2020]

- Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, Li X, Yang B, Song J. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(8):727–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.