Abstract

Reduced cell surface levels of major histocompatibility complex class I antigens enable adenovirus type 12 (Ad12)-transformed cells to escape immunosurveillance by cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL), contributing to their tumorigenic potential. In contrast, nontumorigenic Ad5-transformed cells harbor significant cell surface levels of class I antigens and are susceptible to CTL lysis. Ad12 E1A mediates down-regulation of class I transcription by increasing COUP-TF repressor binding and decreasing NF-κB activator binding to the class I enhancer. The mechanism underlying the decreased binding of nuclear NF-κB in Ad12-transformed cells was investigated. Electrophoretic mobility shift assay analysis of hybrid NF-κB dimers reconstituted from denatured and renatured p50 and p65 subunits from Ad12- and Ad5-transformed cell nuclear extracts demonstrated that p50, and not p65, is responsible for the decreased ability of NF-κB to bind to DNA in Ad12-transformed cells. Hypophosphorylation of p50 was found to correlate with restricted binding of NF-κB to DNA in Ad12-transformed cells. The importance of phosphorylation of p50 for NF-κB binding was further demonstrated by showing that an NF-κB dimer composed of p65 and alkaline phosphatase-treated p50 from Ad5-transformed cell nuclear extracts could not bind to DNA. These results suggest that phosphorylation of p50 is a key step in the nuclear regulation of NF-κB in adenovirus-transformed cells.

All human adenoviruses are able to transform nonpermissive rodent cells in vitro. The viral E1A and E1B transforming genes are responsible for disruption of the cell cycle and prevention of apoptosis (reviewed in reference 56). Interestingly, only a subset of adenovirus serotypes, including adenovirus type 12 (Ad12), can induce the formation of tumors in immunocompetent rodents following inoculation of virus or transformed cells. The highly tumorigenic phenotype of Ad12 correlates with a sharp decrease in cell surface levels of the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I antigens (11, 17, 59). The diminished class I antigen expression on Ad12-transformed cells enables them to escape detection by cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL) and contributes to their tumorigenic potential (11, 63, 70). In contrast, significant cell surface expression of class I antigens on nontumorigenic Ad5-transformed cells allows for CTL recognition and lysis.

E1A is the only gene of Ad12 required for down-regulated synthesis of class I antigens (67). The block in the expression of class I antigens is at the level of transcription (1, 20), and the 47-bp class I enhancer is the target of this transcriptional down-regulation (21, 32) (Fig. 1). In Ad12-transformed cells, the orphan nuclear hormone receptor COUP-TF is strongly bound to the R2 site of the enhancer (39). Additionally, the transcriptional activator NF-κB is weakly bound to the R1 site of the enhancer in Ad12-transformed cells (2, 38, 43, 46). The increased binding of COUP-TF and the decreased binding of NF-κB to the enhancer are mediated by the first exon (residues 1 to 144) of Ad12 E1A (33). In direct contrast, active class I transcription in Ad5-transformed cells can be accounted for by the strong binding of NF-κB and the weak binding of COUP-TF to their respective recognition elements in the enhancer.

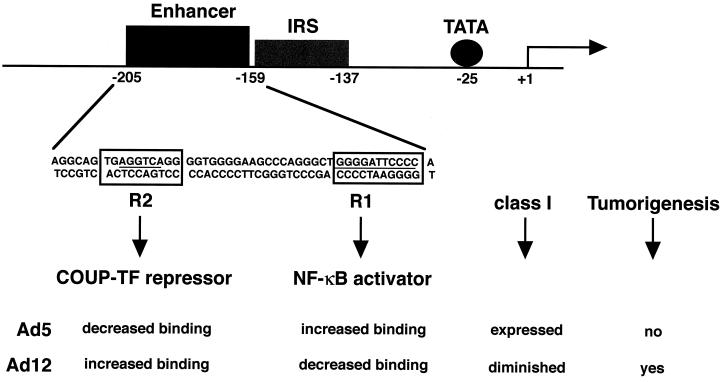

FIG. 1.

Regulation of the MHC class I promoter in adenovirus-transformed cells. Transcription of class I genes is greatly reduced in Ad12- versus Ad5-transformed cells because of increased binding of the COUP-TF repressor to the R2 site and decreased binding of the NF-κB activator to the R1 site of the enhancer. Diminished MHC class I levels correlate with tumorigenic potential. Arrow, transcriptional start site; closed circle, TATA box; gray rectangle, interferon response element (IRS); black rectangle, H-2Kb class I enhancer.

The reason for the decreased binding of NF-κB to the class I enhancer in Ad12-transformed cells is not fully understood. NF-κB is a dimer composed of proteins of the Rel family (reviewed in references 8, 42, 45, and 64). The transcriptionally active form of NF-κB is a heterodimer (66) of the p50 (NF-κB1-p50) subunit (12, 23, 30, 44) and the p65 (RelA) subunit (47, 57), which contains the transactivation domain (10, 54, 58). Typically, NF-κB is sequestered in the cytoplasm by an IκB (reviewed in reference 69). Stimulation of cells with various inducers, such as cytokines, phorbol esters, or growth factors, causes IκB to be phosphorylated by means of a complex kinase cascade (reviewed in reference 62) and degraded by the 26S proteasome (3, 14, 15, 37, 50, 65). As a consequence, cytoplasmic NF-κB becomes free to translocate to the nucleus.

However, in adenovirus-transformed cells, the p50 and p65 subunits of NF-κB are constitutively present in the nucleus (38). In Ad5-transformed cells, NF-κB binds to the R1 site of the class I enhancer, activating class I expression (2, 9, 27, 38, 43, 46, 55, 60). Intriguingly, in Ad12-transformed cells, NF-κB binding to the R1 site is greatly diminished, contributing to the down-regulation of class I transcription. In Ad12- and Ad5-transformed cells, this differential ability of NF-κB to bind to the R1 site cannot be accounted for by a difference in the levels of NF-κB, since the amounts of nuclear p50 and p65, respectively, are approximately equal in these cells (33, 38).

In this paper, we demonstrate that the p50 subunit of the NF-κB dimer is responsible for the decreased binding observed in Ad12-transformed cells. In addition, we provide evidence that hypophosphorylation of the p50 subunit is responsible for the decreased binding phenotype.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines.

The Ad5 (DP5-2) and Ad12 (12-1) E1-transformed Hooded Lister rat cell lines were constructed previously (28, 29). Monolayer cultures of cells were grown in minimal essential medium α (GIBCO-BRL) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (HyClone), 2 mM l-glutamine, 100 U of penicillin per ml, 0.1 mg of streptomycin per ml, and 2.5 μg of amphotericin B (Fungizone) per ml.

Nuclear extract preparation.

Nuclear extracts of DP5-2 and 12-1 cells were prepared as described previously (33) with slight modifications. Briefly, cells were harvested by trypsinization, washed in phosphate-buffered saline, and lysed in 2 packed-cell volumes of Triton lysis buffer (9 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 135 mM NaCl, 0.9 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol [DTT], 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride [PMSF], and either 0.3% Triton X-100 [DP5-2 cells] or 0.35% Triton X-100 [12-1 cells]) for 4 to 6 min on ice. Nuclei were pelleted at 1,000 × g for 5 min at 4°C, washed once in Triton lysis buffer lacking Triton X-100, and then resuspended in 2 packed-cell volumes of Dignam buffer C (25% glycerol, 20 mM HEPES [pH 7.9], 0.42 M NaCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM PMSF, 0.5 mM DTT [16]). Nuclear proteins were extracted by mixing at 4°C for 45 min. Insoluble material was pelleted at 16,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C, and the supernatant was dialyzed for 1 h at 4°C against Shapiro’s buffer D (20 mM HEPES [pH 7.9], 20% glycerol, 100 mM KCl, 0.2 mM EDTA, 0.2 mM EGTA, 2 mM DTT, 0.5 mM PMSF, 0.5 mg of leupeptin per liter, 0.7 mg of pepstatin A per liter [61]). Precipitated proteins were removed by centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C, and the supernatant was stored in aliquots at −80°C. For phosphatase experiments, nuclear extracts were isolated in buffers lacking phosphatase inhibitors.

Western blots and antisera.

Ten micrograms of nuclear extract in sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) sample buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl [pH 6.8], 4% SDS, 0.2% bromophenol blue, 200 mM DTT, 20% glycerol) was boiled and electrophoresed on SDS-polyacrylamide gels. Separated proteins were transferred to Immobilon-P membranes (Millipore) by electroblotting. Membranes were blocked in 0.05% TBS-Tween (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 150 mM NaCl, 0.05% Tween 20) with 5% powdered milk (Carnation) for at least 1 h. Membranes were incubated for 1 h with primary antibody (see below) and then washed three times with 0.05% TBS-Tween. For detection of proteins by enhanced chemiluminescence, membranes were incubated for 1 h with goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G–horseradish peroxidase (Boehringer Mannheim Biochemicals), washed three times with 0.05% TBS-Tween and once with TBS (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 150 mM NaCl), and then exposed to enhanced chemiluminescence reagents (Amersham). For detection of proteins by 125I-conjugated secondary antibody, membranes were washed once with 0.01% TBS-Tween, incubated for 1 h with 1.5 μCi of goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (heavy and light) chains (ICN) per ml, washed three times with 0.01% TBS-Tween and once with TBS, and then exposed overnight on a PhosphorImager screen (Molecular Dynamics). The following peptide antibodies (kind gifts of Nancy Rice) were used in these studies: 1157, anti-p50; 1613, anti-p50; and 1226, anti-p65. YY1 antibody sc-281 was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology.

Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis.

Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis of nuclear extracts from DP5-2 and 12-1 cells was performed by the method of O’Farrell (48) by Kendrick Labs, Inc. (Madison, Wis.). Proteins were run in the first dimension on isoelectric focusing gels containing 2% pH 3.5 to 10 ampholines (BDH-Hoefer) for 9,600 V · h and in the second dimension on a 10% polyacrylamide gel (0.75 mm thick) for about 4 h at 12.5 mA/gel. Electroblotting of proteins to polyvinylidene difluoride paper in transfer buffer (12.5 mM Tris [pH 8.8], 86 mM glycine, 10% methanol) was done overnight at 200 mA. Molecular weight standards were from Sigma.

Denaturation-renaturation and analysis of NF-κB subunits.

Denaturation-renaturation of protein was performed essentially as described previously (24, 66) with modifications. Nuclear extracts from DP5-2 and 12-1 cells were isolated as described above, except that the proteins were dialyzed against Shapiro’s buffer D lacking glycerol and were concentrated at 4°C with a Centricon-30 (Amicon) to ca. 10 mg/ml, as determined by a modified Bradford assay (Bio-Rad). Equivalent milligram amounts of DP5-2 and 12-1 nuclear extracts were separated on SDS–8% polyacrylamide gels; with prestained molecular weight markers (Bio-Rad and New England Biolabs) as a guide, regions of the gels corresponding to 50 kDa (p50) and 65 kDa (p65) were excised and macerated. Protein was eluted overnight at 4°C in 350 μl of elution buffer (50 mM Tris [pH 8.0], 0.1% SDS, 0.1 mg of bovine serum albumin [BSA] per ml, 0.2 mM EDTA, 2.5% glycerol, 1 mM DTT, 0.1 mM PMSF). Two percent of the eluate was retained for Western analysis to verify the recovery of NF-κB subunits from the gel slice. For phosphatase experiments, the eluate was divided and treated with 8 U of calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase (CIP) in the absence or presence of 2 mM sodium orthovanadate, 20 mM NaF, and 1 mM EDTA for 30 min at 37°C. The eluate was precipitated with 4 volumes of acetone overnight at −20°C to remove SDS. The precipitate was pelleted, washed with −20°C methanol, and dissolved in 10 μl of 6 M urea with 2 mM DTT. Suspended 50-kDa (p50) and 65-kDa (p65) proteins were mixed together in various combinations to form NF-κB and then diluted 50-fold by the addition of 1.375× renaturation buffer (1.375× electrophoretic mobility shift assay [EMSA] binding buffer [10 mM Tris-HCl {pH 7.5}, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 5% glycerol], 7% Shapiro’s buffer D, 0.01 mM PMSF). After 2 h of renaturation at 4°C, 2% of the renatured protein was quantitated by 125I Western analysis to analyze the composition of NF-κB in each sample. After 24 h of renaturation, protein was concentrated in a Microcon-10 (Amicon) spin column and used as 73% of the final volume of an EMSA reaction mixture containing 1 μg of poly(dI-dC) and 30,000 cpm of 32P-labeled double-stranded R1 oligonucleotide probe. Reaction mixtures were incubated at 30°C for 30 min and electrophoresed on a 5% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gel in 0.5× TBE buffer (45 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.3], 45 mM boric acid, 0.5 mM EDTA). Dried gels were analyzed with a PhosphorImager and exposed to film.

For deoxycholate (DOC) experiments, after the 30-min EMSA reaction was completed, DOC was added to 0.8% and then Nonidet P-40 (NP-40) was added to 0.2%. After 10 min at room temperature, NP-40 was added to 1%. Five minutes later, samples were electrophoresed.

For supershift analysis, 3 μl of peptide antibody was added to reaction mixtures 15 min prior to the addition of the labeled probe. All denaturation-renaturation experiments were repeated at least three times; the results shown are representative.

Immunoprecipitation analysis.

Monolayer cultures of cells were labeled for 16 to 20 h with 200 μCi of 32Pi (Amersham) per ml. Cells were harvested, washed, and lysed for 20 min at 4°C in buffer X with BSA (50 mM Tris [pH 8.8], 250 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 2 mM EDTA, 2 mg of BSA per ml) and phosphatase and protease inhibitors (250 mM Na3VO4, 50 mM NaF, and 2 mg of aprotinin per ml). Lysates were clarified by centrifugation, normalized by counts per minute, and precleared with protein A for 1 h. Precleared lysates were subjected to primary immunoprecipitation for 4 h, protein A beads were added, and immunocomplexes were collected for 2 h. Beads were washed, and immunoprecipitated protein was released in 100 μl of denaturing buffer (50 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 0.5% SDS, 70 mM β-mercaptoethanol) at 95°C for 7 min. The supernatant was diluted eightfold with RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris [pH 7.2], 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% SDS, 1% DOC, 1% Triton X-100) with phosphatase and protease inhibitors, and sequential immunoprecipitation was performed at 4°C overnight. Protein A beads were added, and immunocomplexes were collected for 2 h. Beads were washed and boiled in SDS sample buffer, and the supernatant was analyzed by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE). Dried gels were autoradiographed.

RESULTS

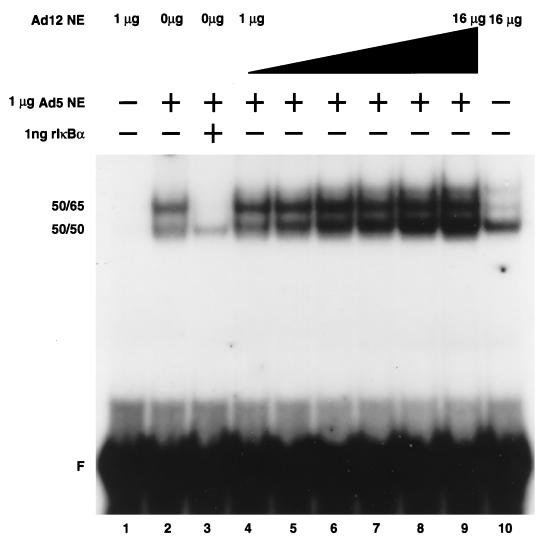

NF-κB binding to the R1 element of the MHC class I enhancer is diminished in tumorigenic Ad12- compared to nontumorigenic Ad5-transformed cells (2, 33, 38, 43, 46). This differential binding of NF-κB between the two cell lines is not due to significant variations in the levels of nuclear p50 or p65 (33, 38). As originally observed (38), treatment of Ad12-transformed cell nuclear extracts with DOC dramatically increased NF-κB binding to the R1 element, as observed by EMSA (see Fig. 4, compare lanes 1 and 2). This result suggested that DOC might selectively remove a nuclear inhibitor of NF-κB without perturbing the strong association of p50 and p65 for one another. Since DOC is known to dissociate IκB from NF-κB (7), it was reasonable to assume that an IκB family member could be the nuclear inhibitor. However, Western blot analysis failed to reveal the presence of known IκB family members in Ad12-transformed cell nuclear extracts (38 and data not shown). To examine if another type of inhibitor might be present in Ad12-transformed cell nuclear extracts, we performed a titration-mixing experiment in which increasing amounts of Ad12-transformed cell nuclear extracts were added to a constant amount of Ad5-transformed cell nuclear extracts and then analyzed by EMSA. As shown in Fig. 2, no reduction in the NF-κB binding activity from Ad5-transformed cell nuclear extracts was observed (lanes 4 to 9), whereas the addition of recombinant IκBα (1 ng) was sufficient to fully inhibit this activity (lane 3). Furthermore, blots probed with a p50 antibody following gel filtration, nondenaturing gel electrophoresis, or cross-linking of nuclear extracts did not reveal size differences in NF-κB from Ad5- and Ad12-transformed cells (data not shown). Thus, there was conflicting evidence for the presence of a nuclear inhibitor of NF-κB in Ad12-transformed cells.

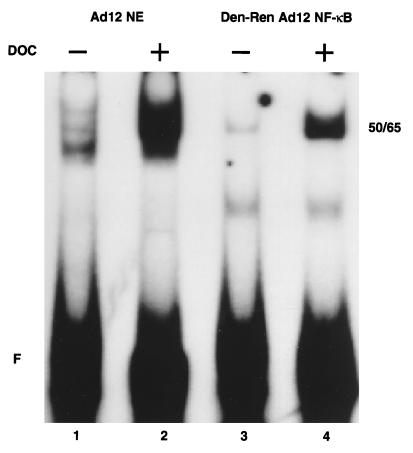

FIG. 4.

Low binding activity of denatured-renatured NF-κB from Ad12-transformed cells is restored by DOC treatment. Nuclear extracts (NE) (lanes 1 and 2) and denatured-renatured (Den-Ren) NF-κB (lanes 3 and 4) from Ad12-transformed cells were subjected to EMSA following treatment with DOC (lanes 2 and 4). Migration of the NF-κB complex is indicated (50/65). F, free R1 site probe.

FIG. 2.

A freely dissociable inhibitor of NF-κB is not present in Ad12-transformed cell nuclear extracts. One microgram of Ad5-transformed cell nuclear extracts (NE) was incubated in an EMSA reaction alone (lane 2), with 1 ng of purified recombinant IκBα (rIκBα) (lane 3), or with increasing amounts (1, 2, 4, 8, 12, or 16 μg) of Ad12-transformed cell nuclear extracts (lanes 4 to 9), followed by electrophoresis on a nondenaturing gel. The increased binding activity in the titration curve (lanes 4 to 9) was largely contributed by the increasing amounts of Ad12-transformed cell nuclear extracts (compare lanes 1 and 10 [1 and 16 μg, respectively]). Identical results were obtained when the total protein in each reaction mixture was adjusted to 17 μg with BSA (data not shown). 50-50 homodimer and 50-65 heterodimer species are indicated. F, free R1 site probe.

The block in NF-κB binding to DNA in Ad12-transformed cells does not appear to involve a dissociable inhibitor.

To examine whether or not a nuclear inhibitor is truly involved in the decreased DNA binding activity of NF-κB in Ad12-transformed cells, we used a denaturation-renaturation approach in which nuclear extracts from Ad5- and Ad12-transformed cells were fractionated by PAGE and the p50 and p65 subunits were excised from the gel, eluted, denatured, mixed together, renatured, and subjected to EMSA. Restoration of binding of denatured-renatured NF-κB from Ad12-transformed cells would indicate the separation of an inhibitor from p50 and p65 during PAGE, whereas nonrestoration of binding would be indicative of an alternative mechanism.

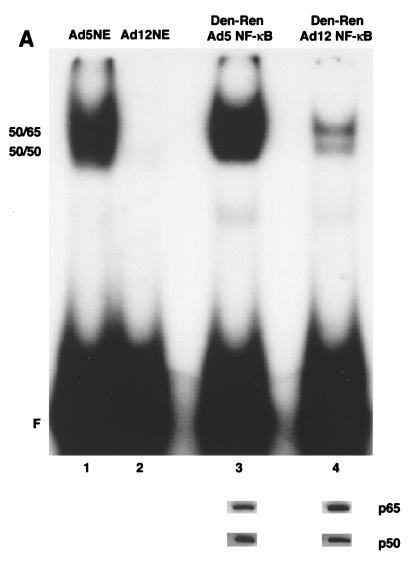

The EMSA in Fig. 3A indicated that NF-κB binding remains diminished after denaturation-renaturation of the p50 and p65 subunits from Ad12- compared to Ad5-transformed cell nuclear extracts. Note that the differential binding activities observed with the denatured-renatured NF-κB proteins (Fig. 3A, lanes 3 and 4) are similar to those seen with unmanipulated nuclear extracts (lanes 1 and 2). This result suggested that there is not a dissociable inhibitor of NF-κB in Ad12-transformed cell nuclear extracts. This low binding activity of denatured-renatured NF-κB from Ad12 was not due to a lack of input of p50 and p65. First, Western blotting indicated that p50 and p65 were individually isolated from the polyacrylamide gel (Fig. 3A, lower panel) and subsequently were retained throughout the denaturation-renaturation procedure. Second, approximately equivalent amounts of the mixed and renatured p50 and p65 subunits from Ad12- and Ad5-transformed cell nuclear extracts were used to obtain dimer compositions with ratios of 125I signals of p65 and p50 similar to those from unmanipulated nuclear extracts (data not shown).

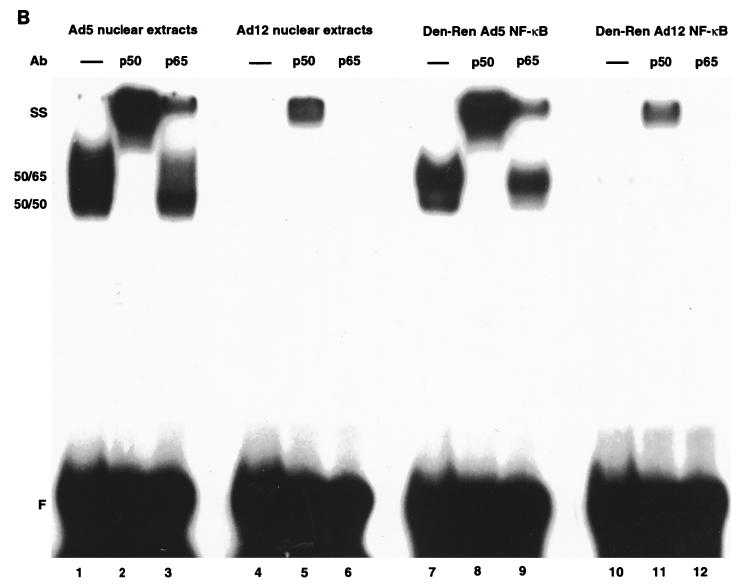

FIG. 3.

Denatured-renatured NF-κB from Ad12-transformed cells retains diminished binding activity. (A) Nuclear extracts (NE) from Ad5- and Ad12-transformed cells were analyzed by EMSA either directly (lanes 1 and 2) or following denaturation-renaturation (Den-Ren) of gel-isolated 50- and 65-kDa proteins (lanes 3 and 4). (Lower panel) Western analysis indicating retention of p50 and p65 during the denaturation-renaturation procedure. (B) Nucleoprotein complexes from denatured-renatured NF-κB (lanes 7 to 12) mirrored those from nuclear extracts (lanes 1 to 6) in a supershift analysis with p50 (1613) and p65 (1226) antibodies (Ab). Overexposures of nucleoprotein complexes from lanes 4 to 6 and 10 to 12 are shown in lanes 13 to 15 and 16 to 18, respectively. 50-50 homodimer, 50-65 heterodimer, and supershift (SS) species are indicated. F, free R1 site probe.

To verify that the EMSA complexes generated from the samples of denatured-renatured NF-κB (Fig. 3A) were truly composed of p50 and p65, a supershift analysis was performed. As shown in Fig. 3B, for Ad5, anti-p50 and anti-p65 antibodies were each able to supershift NF-κB from both unmanipulated nuclear extracts and denatured-renatured NF-κB (33) (Fig. 3B, lanes 1 to 3 and 7 to 9). For Ad12, these antibodies also shifted NF-κB from both unmanipulated nuclear extracts and denatured-renatured NF-κB (Fig. 3B, lanes 4 to 6 and 10 to 12), although the signal was dramatically reduced, as expected. These signals can be seen upon overexposure (Fig. 3B, lanes 13 to 18). Note that the increased binding activity seen in the supershifts with the anti-p50 antibody 1613 (Fig. 3B, lanes 2, 5, 8, 11, 14, and 17) is likely due to a stabilization effect.

Since these denaturation-renaturation experiments strongly suggested that there is no dissociable protein inhibitor of NF-κB in Ad12-transformed cell nuclear extracts, we wished to investigate the action of DOC on denatured-renatured NF-κB by EMSA. Nuclear proteins from Ad12-transformed cells were separated by PAGE, and p50 and p65 were isolated from the gel, denatured, and renatured as described above. EMSA reaction mixtures were incubated for 30 min, treated with DOC, and analyzed on a nondenaturing gel (Fig. 4). As described above, treatment of unmanipulated Ad12-transformed cell nuclear extracts with DOC resulted in increased DNA binding activity compared to that in untreated nuclear extracts (Fig. 4, lanes 1 and 2). Interestingly, a marked increase in this binding activity was also observed when denatured-renatured NF-κB was treated with DOC (Fig. 4, lane 4), compared to the results obtained with the untreated sample (lane 3). Therefore, DOC treatment likely increases NF-κB binding to DNA in a manner distinct from the dissociation of a protein inhibitor (see below).

These results demonstrated that it is possible to denature and reconstitute NF-κB from nuclear extracts from Ad5- and Ad12-transformed cells. The integrity and composition of the denatured-renatured NF-κB used in the EMSAs are reflective of those of native NF-κB from unmanipulated nuclear extracts. The observation that denatured-renatured NF-κB from Ad12-transformed cell nuclear extracts did not restore binding to DNA supports the notion that a dissociable inhibitor of nuclear NF-κB is not present in Ad12-transformed cells.

Nuclear p50 from Ad12-transformed cells is responsible for diminished NF-κB binding.

To further characterize the mechanism responsible for the decreased binding of NF-κB in Ad12-transformed cells, we sought to address if either p50 or p65 is functionally altered. To do so, we again used denaturation-renaturation analysis of the p50 and p65 subunits from Ad5- and Ad12-transformed cell nuclear extracts. Hybrid NF-κB dimers were created by mixing p50 from Ad5 with p65 from Ad12 and p50 from Ad12 with p65 from Ad5. Significantly, as shown in Fig. 5, the NF-κB–DNA complex containing the dimer composed of p50 from Ad5 and p65 from Ad12 (lane 3) recognized the labeled probe more strongly than did the complex containing the dimer composed of p50 from Ad12 and p65 from Ad5 (lane 4). The differential binding activities observed with the hybrid dimers (Fig. 5, lanes 3 and 4) paralleled those observed with the denatured-renatured dimers from Ad5- and Ad12-transformed cell nuclear extracts (lanes 1 and 2). This result demonstrated that p50 is the component of the p50-p65 heterodimer which is responsible for the reduced binding of NF-κB to DNA in Ad12-transformed cell nuclear extracts.

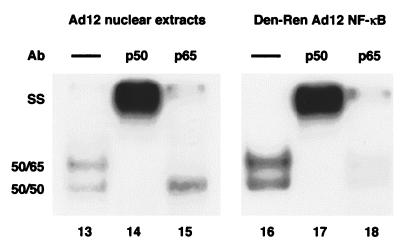

FIG. 5.

The p50 subunit contributes to the decreased DNA binding activity of NF-κB in Ad12-transformed cells. Lanes 1 and 2, denatured-renatured (Den-Ren) NF-κB from Ad5- and Ad12-transformed cell nuclear extracts, respectively. Lane 3, hybrid denatured-renatured NF-κB with p50 from Ad5-transformed cell nuclear extracts and p65 from Ad12-transformed cell nuclear extracts. Lane 4, hybrid denatured-renatured NF-κB with p50 from Ad12-transformed cell nuclear extracts and p65 from Ad5-transformed cell nuclear extracts. 50-50 homodimers and 50-65 heterodimers are indicated. F, free R1 site probe.

DOC can enhance NF-κB binding by affecting p65.

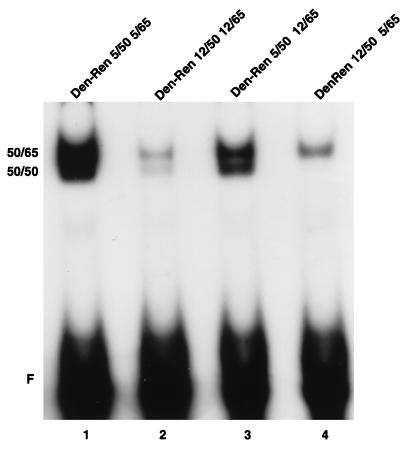

A caveat with regard to the above results is that the decreased binding activity of NF-κB from Ad12-transformed cell nuclear extracts is due to a 50-kDa “inhibitor” which fortuitously copurifies with the p50-containing gel slice. Such a putative copurified inhibitor would be stripped from NF-κB upon treatment of the nuclear extracts with DOC, thereby restoring NF-κB binding to DNA. To address the possibility of whether an inhibitor copurifies with p50, denatured-renatured p50 homodimers were treated with DOC and tested by EMSA to determine if increased binding would occur. As shown in Fig. 6, DOC had no enhancing effect on the binding activity of these homodimers from either Ad5- or Ad12-transformed cell nuclear extracts (lanes 1 to 4), consistent with the absence of a copurifying 50-kDa inhibitor in Ad12-transformed cells. Quite unexpectedly, however, when denatured-renatured p65 homodimers from Ad5- and Ad12-transformed cell nuclear extracts were similarly assayed, a noticeable increase in binding activity in the presence of DOC was observed (Fig. 6, compare lane 5 with lane 6 and compare lane 7 with lane 8). Supershift analysis confirmed that the complexes observed in Fig. 6, lanes 5 to 8, contain p65 (data not shown). Taken together, these results ruled out the possibility of a proteinaceous inhibitor in Ad12-transformed cells and also suggested that DOC restores NF-κB binding in Ad12-transformed cell nuclear extracts through its action on the p65 subunit.

FIG. 6.

DOC enhances DNA binding by affecting p65. Denatured-renatured homodimers of p50 (lanes 1 to 4) or p65 (lanes 5 to 8) from Ad5 (lanes 1, 2, 5, and 6)- and Ad12 (lanes 3, 4, 7, and 8)-transformed cell nuclear extracts were subjected to EMSA following treatment with DOC (even-numbered lanes). The reduced signals in lanes 7 and 8 compared to those in lanes 5 and 6 were due to less denatured-renatured p65 homodimer from Ad12 than from Ad5, respectively, used in the EMSA as determined by quantitative Western analysis. Migration of homodimers is indicated (50/50 and 65/65). F, free R1 site probe.

p50 in Ad12- and Ad5-transformed cells is differentially modified.

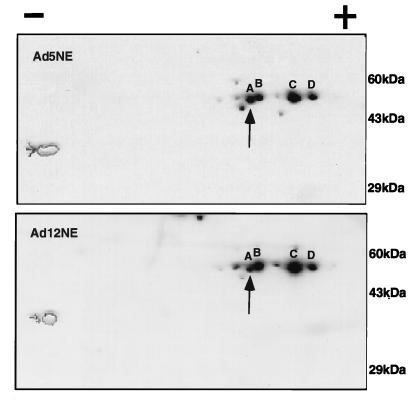

The denaturation-renaturation experiments indicated that the diminished NF-κB binding activity seen in Ad12-transformed cells is likely due to an alteration of p50 in these cells. To determine if Ad5- and Ad12-transformed cells harbor different forms of p50, nuclear extracts were separated by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis followed by Western blot analysis. As shown in Fig. 7, four major forms of p50 (species A to D) were identified in both Ad5- and Ad12-transformed cell nuclear extracts. These p50 species were authentic, as the antibody used (1157) has absolute specificity, based on its inability to recognize any 50-kDa protein in p50−/− knockout mouse cell extracts (52). Intriguingly, the signal from the most negatively charged of the four forms of p50 (species A) was found to be weaker in Ad12-transformed nuclear cell extracts than in Ad5-transformed cell nuclear extracts. Densitometric analysis revealed that there was approximately 4.5-fold less species A relative to the total amount of p50 in Ad12- than in Ad5-transformed cell nuclear extracts. The two-dimensional blot probed with a p65 antibody revealed no differences in the forms of p65 from Ad12- and Ad5-transformed cell nuclear extracts (data not shown).

FIG. 7.

Two-dimensional gel analysis of charged p50 species from Ad12- and Ad5-transformed cell nuclear extracts. Equivalent amounts of protein from nuclear extracts (NE) of Ad5- and Ad12-transformed cells were separated by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis, transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride paper, and probed with p50 antibody (1157). A to D, four major charged species of p50; the vertical arrow points to species A. The horizontal arrow pointing to the oval near the negative pole indicates the migration of the tropomyosin internal control, visualized by Coomassie blue staining prior to immunoblotting. The pH in the Western blots ranged from 4.8 (positive pole) to 8.9 (negative pole).

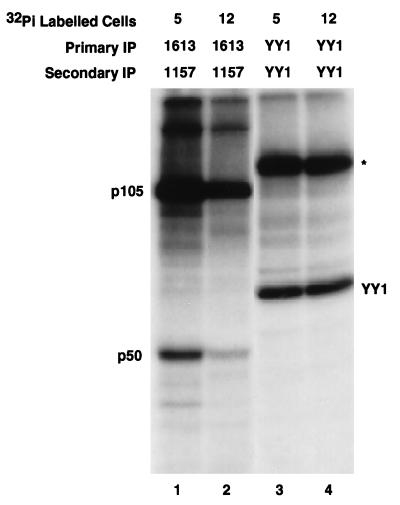

The reduced level of p50 species A from Ad12-transformed cells in the two-dimensional Western analysis suggested that p50 may be less phosphorylated in these cells. To examine this possibility, monolayer cultures of Ad5- and Ad12-transformed cells were labeled with 32Pi. Lysates normalized for counts were subjected to sequential immunoprecipitation analysis. Since the absolutely specific anti-p50 antibody 1157 (described above) reacts only against its denatured epitope, a p50 antibody which recognizes native p50 (1613) was used to perform the primary immunoprecipitation. The immunocomplexes were then boiled and subjected to the second immunoprecipitation with the p50-specific antibody 1157. Notably, the amount of 32Pi-labeled p50 recovered from lysates of Ad5-transformed cells was greater than that recovered from Ad12-transformed cells (Fig. 8, lanes 1 and 2), whereas no difference in the signal from control YY1 was observed (lanes 3 and 4). The YY1 transcription factor was chosen as a control because extracts from both Ad5- and Ad12-transformed cells harbor it in nearly equivalent amounts, as observed by Western analysis and EMSA (data not shown). Not surprisingly, the reduced level of phosphorylation of p105 in Ad12- compared to Ad5-transformed cells (Fig. 8, lanes 1 and 2) can be attributed to the fact that the p50 coding region is the N terminus of p105. In contrast, no difference in the level of phosphorylation of p65 was observed (data not shown). Thus, this differential level of phosphorylation of p50 from Ad12- and Ad5-transformed cells observed in the immunoprecipitation analysis correlates with the differential intensity of the most negatively charged form of p50, species A, seen in the Western blot of the two-dimensional gel (Fig. 7). This result is consistent with the notion that the low DNA binding activity of NF-κB in Ad12-transformed cell nuclear extracts stems from a modification of p50, such as phosphorylation, as opposed to the presence of a dissociable inhibitor.

FIG. 8.

p50 is less phosphorylated in Ad12- than in Ad5-transformed cells. Normalized lysates from 32Pi-labeled cells were subjected to sequential immunoprecipitation (IP) with antibodies 1613 and 1157 (reactive to native and denatured p50 epitopes, respectively) to detect phosphorylated p50. The equal amounts of phosphorylated YY1 that were immunoprecipitated from the two cell types verified that the normalization of counts was accurate. The positions of labeled protein species are indicated. The identity of the band (marked with an asterisk) that cross-reacted with the YY1 antisera is unknown.

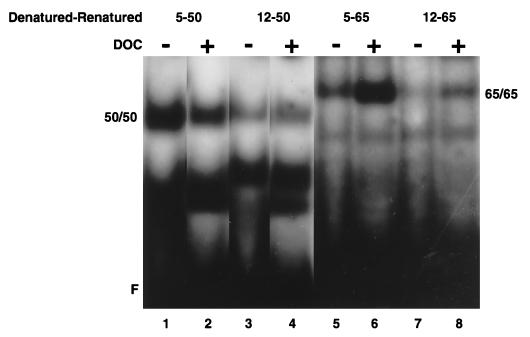

Phosphorylation of p50 contributes to DNA binding of NF-κB.

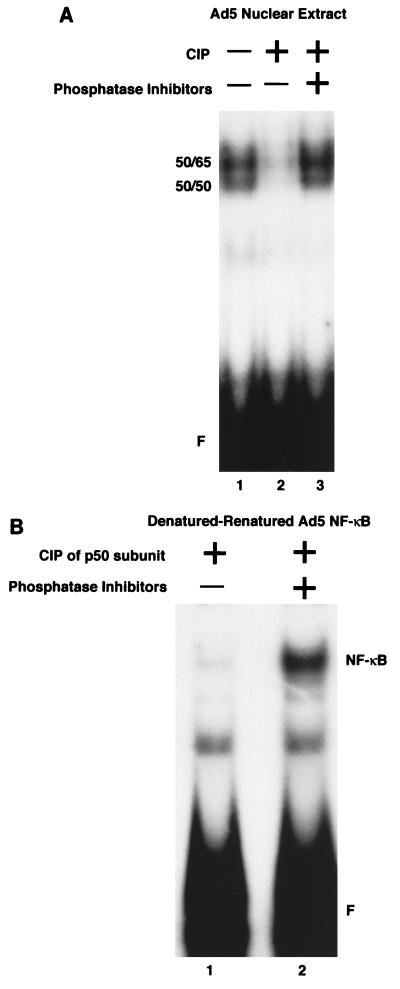

The experiments outlined above indicated that there may be a correlation between the level of phosphorylation of p50 and the ability of NF-κB to bind to DNA. To directly demonstrate that phosphorylation of NF-κB is important for DNA binding, nuclear extracts from Ad5-transformed cells (which contain hyperphosphorylated p50 and strongly binding NF-κB) were isolated in the absence of phosphatase inhibitors, either mock treated, CIP treated, or CIP treated in the presence of phosphatase inhibitors, and then subjected to EMSA. As shown in Fig. 9A, the endogenous NF-κB binding activity observed in Ad5-transformed cell nuclear extracts (lane 1) was ablated when extracts were CIP treated (lane 2) but was unaltered when CIP was added to extracts containing phosphatase inhibitors (lane 3), indicating that phosphorylation of NF-κB is critical for DNA binding activity.

FIG. 9.

Phosphorylation of p50 is critical for NF-κB binding activity. (A) Dephosphorylation of NF-κB ablates binding activity. Nuclear extracts were untreated (lane 1) or treated with CIP in the absence (lane 2) or presence (lane 3) of phosphatase inhibitors prior to EMSA. (B) Phosphorylation of p50 specifically contributes to DNA binding of NF-κB. The denaturation-renaturation procedure included a CIP treatment step after elution of the 50-kDa proteins from the polyacrylamide gel. EMSA reaction mixtures contained NF-κB with CIP-treated p50 (lane 1) or CIP-treated p50 in the presence of phosphatase inhibitors (lane 2) and untreated (phosphorylated) p65. F, free R1 site probe.

To determine if phosphorylation of p50 specifically is responsible for the ability of NF-κB to bind to DNA, the denaturation-renaturation system was again used. Nuclear extracts from Ad5-transformed cells were isolated and fractionated by PAGE, and the p50 and p65 subunits were excised from the gel and eluted. The eluate containing p50 was halved, treated with CIP or CIP in the presence of phosphatase inhibitors, and denatured. The p50 samples were mixed with the denatured p65 subunit which was not CIP treated. The mixed subunits were renatured and subjected to EMSA. Figure 9B shows that dephosphorylated p50, when present with phosphorylated p65, had dramatically reduced DNA binding activity (lane 1) compared to NF-κB in which p50 and p65 were both phosphorylated (lane 2). Interestingly, CIP treatment of denatured p50 subunits inhibited the formation of p50 homodimers following renaturation (data not shown). Therefore, phosphorylation of p50 is required for optimal DNA binding activity of NF-κB.

DISCUSSION

Diminished surface expression of the MHC class I antigens contributes to the tumorigenic potential of transformed cells by enabling them to evade immune detection by CTL. The tumorigenicity of Ad12-transformed cells correlates with decreased MHC class I expression (11, 17, 59, 70). In these cells, E1A mediates down-regulation of MHC class I transcription by increasing the binding of the repressor COUP-TF and decreasing the binding of the activator NF-κB to the class I enhancer (2, 38, 39, 43, 46).

At the onset of this study, there were conflicting arguments to account for the mechanism by which NF-κB is blocked from binding to the R1 site of the class I enhancer in Ad12-transformed cells. In one case, the presence of a nuclear inhibitor was suggested by the restoration of NF-κB binding to DNA following treatment of nuclear extracts with the detergent DOC. However, Ad12-transformed cell nuclear extracts failed to transinhibit the strong NF-κB binding in Ad5-transformed cell nuclear extracts, leading us to question the existence of a nuclear inhibitor and suggesting that NF-κB could be differentially modified in Ad12-transformed cells.

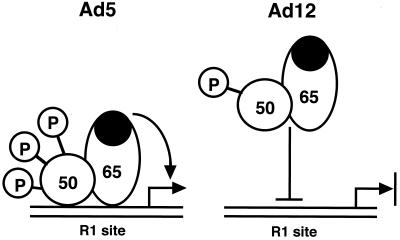

In this study, we used a variety of biochemical approaches to establish that in Ad12-transformed cells, decreased binding of NF-κB is related to a modification of the p50 subunit and is not due to a nuclear inhibitor. In addition, hypophosphorylation of p50 correlates with restricted binding of NF-κB to DNA (Fig. 10). Furthermore, the enhanced binding of NF-κB to DNA in the presence of DOC is due to an effect of the detergent on the p65 subunit of NF-κB. These findings therefore not only aid in the understanding of the mechanism responsible for the block of NF-κB binding to the class I enhancer in Ad12-transformed cells but also suggest that p50 phosphorylation is critical for NF-κB binding to DNA.

FIG. 10.

Model showing that NF-κB containing hypophosphorylated p50 has a reduced ability to bind to DNA in Ad12-transformed cells. In contrast, in Ad5-transformed cells, NF-κB containing hyperphosphorylated p50 actively binds to DNA. The black oval in p65 represents its transactivation domain.

To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first demonstration that p50 phosphorylation is important for NF-κB binding. This conclusion is based largely on the observation that dephosphorylation of the p50 subunit isolated from Ad5-transformed cell nuclear extracts impairs the ability of reconstituted NF-κB to bind to DNA. Consistent with this requirement for p50 phosphorylation for p50-p65 NF-κB heterodimer binding, Li et al. have shown that the in vitro phosphorylation of bacterially produced p50 by protein kinase C results in the enhancement of p50 homodimer binding to DNA (35).

It is important to consider how differential phosphorylation of p50 affects the ability of NF-κB to bind to DNA in Ad12-transformed cells. One possibility is that reduced p50 phosphorylation inhibits dimerization. However, equivalent amounts of p65 were coimmunoprecipitated with p50 in both Ad12- and Ad5-transformed cells (34). This result indicates that the decreased phosphorylation of p50 in Ad12-transformed cells does not impair dimerization but rather inhibits binding of the dimer to DNA. It is also important to question if p65 is differentially modified in Ad12- versus Ad5-transformed cells. Three pieces of evidence suggest that p65 is not differentially altered. First, identical species of p65 were observed in the two-dimensional gels of Ad12- and Ad5-transformed cell nuclear extracts (34). Second, a hybrid NF-κB composed of p65 from Ad12 and p50 from Ad5 strongly bound to DNA. Finally, the transactivation domain of p65 is not functionally impaired or inhibited in Ad12-transformed cells, since a transfected Gal4-p65 transactivation domain was able to transactivate a promoter containing Gal4 DNA binding sites (34). These results indicate that in Ad12- versus Ad5-transformed cells, p50, but not p65, is differentially modified and that this modification reduces the ability of NF-κB to bind to DNA.

While phosphorylation of p50 is critical for the binding of NF-κB to DNA as shown in this study, phosphorylation of p65 was recently shown to be important for NF-κB transactivation (71). Phosphorylation of p65 by protein kinase A allows p65 to unfold and interact with p300 in order to transactivate (71). In Ad12-transformed cells, unfolded and transcriptionally potent p65 dimerized with hypophosphorylated p50 would be unable to transactivate, as the NF-κB heterodimer cannot bind to DNA. Therefore, the phosphostatus of p50 may be critical in the ultimate ability of NF-κB to transactivate. Indeed, unlike p50 homodimers and the NF-κB heterodimer, p65 homodimers do not readily bind to DNA. Significantly, the recent elucidation of the DNA-bound NF-κB crystal structure (13) also indicates the importance of p50 making fixed contacts with a specific DNA sequence, 5′-GGGRN-3′. Perhaps phosphorylation of p50 alters its conformation to facilitate interaction with these key nucleotides. The observation that p65 has less rigorous requirements for specific residues for DNA interaction adds to the notion that p50 is important for enabling NF-κB to bind to DNA.

An interesting observation of this study is the indication that DOC acts directly on p65 to enhance NF-κB binding. One explanation is that detergent binding induces swelling or a conformational alteration of p65 which consequently facilitates the DNA binding ability of NF-κB. Intriguingly, upon binding to purified calf brain tubulin, DOC has been shown to expand the protein, as examined by sedimentation, circular dichroism, and synchrotron X-ray scattering analyses (4–6). Interestingly, Zhong and colleagues recently observed that the N and C termini of p65 intramolecularly interact until phosphorylated at serine 276 by protein kinase A, which opens the protein and enhances DNA binding of NF-κB (71). DOC may relieve this intramolecular interaction in p65, enhancing NF-κB binding. Indeed, we have observed that the enhanced binding of NF-κB to DNA in the presence of DOC is not limited to Ad12-transformed cell nuclear extracts but that DOC further increases the strong binding activity of NF-κB in nuclear extracts from Ad5- and simian virus 40-transformed cells (40). Perhaps in addition to opening p65, DOC acts in some manner to permit NF-κB binding activity to occur independently of the phosphostatus of p50. Notably, the ability of DOC to release IκB from NF-κB (7) may not be mutually exclusive of the possibility that DOC has the ability to disrupt the intramolecular association of p65 termini. Whether or not DOC has this effect on other transcription factors should be considered, as this detergent is commonly used to characterize multiprotein-DNA complexes by EMSA.

Multiple phosphorylation events have been shown to be critical in the regulation of members of the Rel/NF-κB family (reviewed in reference 19). Identification of the p50 phosphorylation sites and relevant kinases or phosphatases will enhance understanding of how the binding of NF-κB is regulated. Initial phosphopeptide mapping studies indicate that p50 is serine phosphorylated in primary T lymphocytes (25) and in phorbol myristate acetate- and phytohemagglutinin-stimulated Jurkat T cells (36), although other investigators have been unable to detect 32Pi-labeled p50 in stimulated Jurkat T cells by immunoprecipitation (41). We clearly can recover 32Pi-labeled p50 from Ad5-transformed cells and can observe a faint signal from Ad12-transformed cells. Interestingly, Ad5 E1A has been shown to be associated with a serine/threonine kinase composed of cyclin E-p33cdk2 and cyclin A-p33cdk2 (18, 26, 31). The former kinase has been shown to be associated with p65 via the E1A-associated coactivator p300 (53), but it is unclear if this kinase is specific for p50. Perhaps the decreased phosphorylation of p50 in Ad12-transformed cells results from inhibition of a kinase activity mediated by the Ad12 E1A protein. Alternatively, the possibility that a phosphatase acts on p50 exclusively in Ad12-transformed cells cannot be excluded. Additional regulatory complexity may result from the numerous protein interactions among E1A, p300, and p65. For example, both p300 and Ad5 E1A have been shown to interact with the C terminus of p65 (22, 49, 53). It has also been shown that an amino-terminally modified Ad12 E1A which fails to interact with p300 exists (68). In addition, p300 itself is differentially phosphorylated in Ad12 E1- versus Ad5 E1-transformed cells (51). Whether any of these interactions is significant in terms of regulation of NF-κB via p50 phosphorylation remains to be determined.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Nancy Rice for helpful discussions and for Rel family antibodies, Tom Kadesch for valuable suggestions, Rebecca Taub for recombinant IκBα, and Patrick Baeuerle for Gal4-p65 plasmids. We thank members of the Ricciardi laboratory for critical reading of the manuscript. We also thank Holly Hans, Noam Harel, Chuck Whitbeck, and Sharon Willis for technical advice.

This work was supported in part by NIH training grant 5-T32-AI0735 (to D.B.K.) and by NIH grant CA29797 (to R.P.R.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Ackrill A M, Blair G E. Regulation of major histocompatibility class I gene expression at the level of transcription in highly oncogenic adenovirus transformed rat cells. Oncogene. 1988;3:483–487. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ackrill A M, Blair G E. Nuclear proteins binding to an enhancer element of the major histocompatibility complex promoter: differences between highly oncogenic and nononcogenic adenovirus-transformed rat cells. Virology. 1989;172:643–646. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(89)90207-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alkalay I, Yaron A, Hatzubai A, Jung S, Avraham A, Gerlitz O, Pashut-Lavon I, Ben-Neriah Y. In vivo stimulation of IκB phosphorylation is not sufficient to activate NF-κB. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:1294–1301. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.3.1294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andreu J M, de la Torre J, Carrascosa J L. Interaction of tubulin with octyl glucoside and deoxycholate. 2. Protein conformation, binding of colchicine ligands, and microtubule assembly. Biochemistry. 1986;25:5230–5239. doi: 10.1021/bi00366a037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andreu J M, Garcia de Ancos J, Starling D, Hodgkinson J L, Bordas J. A synchrotron X-ray scattering characterization of purified tubulin and of its expansion induced by mild detergent binding. Biochemistry. 1989;28:4036–4040. doi: 10.1021/bi00435a060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andreu J M, Muñoz J A. Interaction of tubulin with octyl glucoside and deoxycholate. 1. Binding and hydrodynamic studies. Biochemistry. 1986;25:5220–5230. doi: 10.1021/bi00366a036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baeuerle P A, Baltimore D. Activation of DNA-binding activity in an apparently cytoplasmic precursor of the NF-κB transcription factor. Cell. 1988;53:211–217. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90382-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baeuerle P A, Baltimore D. NF-κB: ten years after. Cell. 1996;87:13–20. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81318-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baldwin A S, Jr, Sharp P A. Two transcription factors, NF-κB and H2TF1, interact with a single regulatory sequence in the class I major histocompatibility complex promoter. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:723–727. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.3.723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ballard D W, Nixon E P, Peffer N J, Bogerd H, Doerre S, Stein B, Greene W C. The 65-kDa subunit of human NF-κB functions as a potent transcriptional activator and a target for v-Rel-mediated repression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:1875–1879. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.5.1875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bernards R, Schrier P I, Houweling A, Bos J L, van der Eb A J, Zijlstra M, Melief C J. Tumorigenicity of cells transformed by adenovirus type 12 by evasion of T-cell immunity. Nature (London) 1983;305:776–779. doi: 10.1038/305776a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bours V, Villalobos J, Burd P R, Kelly K, Siebenlist U. Cloning of a mitogen-inducible gene encoding a κB DNA-binding protein with homology to the rel oncogene and to cell-cycle motifs. Nature (London) 1990;348:76–80. doi: 10.1038/348076a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen F E, Huang D-B, Chen Y-Q, Ghosh G. Crystal structure of p50/p65 heterodimer of transcription factor NF-κB bound to DNA. Nature. 1998;391:410–413. doi: 10.1038/34956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen Z, Hagler J, Palombella V J, Melandri F, Scherer D, Baltimore D, Maniatis T. Signal-induced site-specific phosphorylation targets IκBα to the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Genes Dev. 1995;9:1586–1597. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.13.1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DiDonato J A, Mercurio F, Karin M. Phosphorylation of IκBα precedes but is not sufficient for its dissociation from NF-κB. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:1302–1311. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.3.1302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dignam J D, Lebovitz R M, Roeder R G. Accurate transcription initiation by RNA polymerase II in a soluble extract from isolated mammalian nuclei. Nucleic Acids Res. 1983;11:1475–1489. doi: 10.1093/nar/11.5.1475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eager K B, Williams J, Breiding D, Pan S, Knowles B, Appella E, Ricciardi R P. Expression of histocompatibility antigens H-2K, -D, and -L is reduced in adenovirus-12-transformed mouse cells and is restored by interferon-γ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:5525–5529. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.16.5525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Faha B, Harlow E, Lees E. The adenovirus E1A-associated kinase consists of cyclin E-p33cdk2 and cyclin A-p33cdk2. J Virol. 1993;67:2456–2465. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.5.2456-2465.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Finco T S, Baldwin A S., Jr Mechanistic aspects of NF-κB regulation: the emerging role of phosphorylation and proteolysis. Immunity. 1995;3:263–272. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90112-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Friedman D J, Ricciardi R P. Adenovirus type 12 E1A gene represses accumulation of MHC class I mRNAs at the level of transcription. Virology. 1988;165:303–305. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(88)90689-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ge R, Kralli A, Weinmann R, Ricciardi R P. Down-regulation of the major histocompatibility complex class I enhancer in adenovirus type 12-transformed cells is accompanied by an increase in factor binding. J Virol. 1992;66:6969–6978. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.12.6969-6978.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gerritsen M E, Williams A J, Neish A S, Moore S, Shi Y, Collins T. CREB-binding protein/p300 are transcriptional coactivators of p65. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:2927–2932. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.7.2927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ghosh S, Gifford A M, Riviere L R, Tempst P, Nolan G P, Baltimore D. Cloning of the p50 DNA-binding subunit of NF-κB: homology to rel and dorsal. Cell. 1990;62:1019–1029. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90276-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hager D A, Burgess R R. Elution of proteins from sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gels, removal of sodium dodecyl sulfate, and renaturation of enzymatic activity: results with sigma subunit of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase, wheat germ DNA topoisomerase, and other enzymes. Anal Biochem. 1980;109:76–86. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(80)90013-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hayashi T, Sekine T, Okamoto T. Identification of a new serine kinase that activates NF-κB by direct phosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:26790–26795. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Herrmann C H, Su L-K, Harlow E. Adenovirus E1A is associated with a serine/threonine protein kinase. J Virol. 1991;65:5848–5859. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.11.5848-5859.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Israël A, Le Bail O, Hatat D, Piette J, Kieran M, Logeat F, Wallach D, Fellous M, Kourilsky P. TNF stimulates expression of mouse MHC class I genes by inducing an NF-κB-like enhancer binding activity which displaces constitutive factors. EMBO J. 1989;8:3793–3800. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb08556.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jelinek T, Graham F L. Recombinant human adenoviruses containing hybrid adenovirus type 5 (Ad5)/Ad12 E1A genes: characterization of hybrid E1A proteins and analysis of transforming activity and host range. J Virol. 1992;66:4117–4125. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.7.4117-4125.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jelinek T, Pereira D S, Graham F L. Tumorigenicity of adenovirus-transformed rodent cells is influenced by at least two regions of adenovirus type 12 early region 1A. J Virol. 1994;68:888–896. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.2.888-896.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kieran M, Blank V, Logeat F, Vanderkerckhove J, Lottspeich F, Le Bail O, Urban M B, Kourilsky P, Baeuerle P A, Israël A. The DNA binding subunit of NF-κB is identical to factor KBF1 and homologous to the rel oncogene product. Cell. 1990;62:1007–1018. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90275-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kleinberger T, Shenk T. A protein kinase is present in a complex with adenovirus E1A proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:11143–11147. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.24.11143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kralli A, Ge R, Graeven U, Ricciardi R P, Weinmann R. Negative regulation of the major histocompatibility complex enhancer in adenovirus type 12-transformed cells via a retinoic acid response element. J Virol. 1992;68:6979–6988. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.12.6979-6988.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kushner D B, Pereira D S, Liu X, Graham F L, Ricciardi R P. The first exon of Ad12 E1A excluding the transactivation domain mediates differential binding of COUP-TF and NF-κB to the MHC class I enhancer in transformed cells. Oncogene. 1996;12:143–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kushner, D. B., and R. P. Ricciardi. Unpublished observations.

- 35.Li C-C H, Dai R-M, Chen E, Longo D L. Phosphorylation of NF-κB1-p50 is involved in NF-κB activation and stable DNA binding. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:30089–30092. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li C-C H, Korner M, Ferris D K, Chen E, Dai R-M, Longo D L. NF-κB/Rel family members are physically associated phosphoproteins. Biochem J. 1994;303:499–506. doi: 10.1042/bj3030499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lin Y C, Brown K, Siebenlist U. Activation of NF-κB requires proteolysis of the inhibitor IκB-α: signal-induced phosphorylation of IκB-α alone does not release active NF-κB. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:552–556. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.2.552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu X, Ge R, Ricciardi R P. Evidence for the involvement of a nuclear NF-κB inhibitor in global down-regulation of the major histocompatibility complex class I enhancer in adenovirus type 12-transformed cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:398–404. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.1.398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu X, Ge R, Westmoreland S, Cooney A J, Tsai S Y, Tsai M-J, Ricciardi R P. Negative regulation by the R2 element of the MHC class I enhancer in adenovirus-12 transformed cells correlates with high levels of COUP-TF binding. Oncogene. 1994;9:2183–2190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu, X., D. B. Kushner, and R. P. Ricciardi. Unpublished results.

- 41.MacKichan M L, Logeat F, Israël A. Phosphorylation of p105 PEST sequences via a redox-insensitive pathway up-regulates processing to p50 NF-κB. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:6084–6091. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.11.6084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.May M J, Ghosh S. Rel/NF-κB and IκB proteins: an overview. Semin Cancer Biol. 1997;8:63–73. doi: 10.1006/scbi.1997.0057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Meijer I, Boot A J M, Mahabir G, Zantema A, van der Eb A J. Reduced binding activity of transcription factor NF-κB accounts for MHC class I repression in adenovirus type 12 E1-transformed cells. Cell Immunol. 1992;145:56–65. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(92)90312-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Meyer R, Hatada E N, Hohmann H P, Haiker M, Bartsch C, Rothlisberger U, Lahm H W, Schlaeger E J, van Loon A P G M, Scheidereit C. Cloning of the DNA-binding subunit of human nuclear factor κB: the level of its mRNA is strongly regulated by phorbol ester or tumor necrosis factor α. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:966–970. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.3.966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Miyamoto S, Verma I M. Rel/NF-κB/IκB story. Adv Cancer Res. 1995;66:255–292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nielsch U, Zimmer S G, Babiss L E. Changes in NF-κB and ISGF3 DNA binding activities are responsible for differences in MHC and β-IFN gene expression in Ad5- versus Ad12-transformed cells. EMBO J. 1991;10:4169–4175. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb04995.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nolan G P, Ghosh S, Liou H C, Tempst P, Baltimore D. DNA binding and IκB inhibition of the cloned p65 subunit of NF-κB, a rel-related polypeptide. Cell. 1991;64:961–969. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90320-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.O’Farrell P H. High resolution two-dimensional electrophoresis of proteins. J Biol Chem. 1975;250:4007–4021. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Paal K, Baeuerle P A, Schmitz M L. Basal transcription factors TBP and TFIIB and the viral coactivator E1A 13S bind with distinct affinities and kinetics to the transactivation domain of NF-κB p65. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:1050–1055. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.5.1050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Palombella V J, Rando O J, Goldberg A L, Maniatis T. The ubiquitin-proteasome pathway is required for processing the NF-κB1 precursor protein and the activation of NF-κB. Cell. 1994;78:773–785. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(94)90482-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pereira D S, Jelinek T, Graham F L. The adenovirus E1A-associated p300 protein is differentially phosphorylated in Ad12 E1A- compared to Ad5 E1A-transformed rat cells. Int J Oncol. 1994;5:1197–1205. doi: 10.3892/ijo.5.6.1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pereira D S, Kushner D B, Ricciardi R P, Graham F L. Testing NF-κB1-p50 antibody specificity using knockout mice. Oncogene. 1996;13:445–446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Perkins N D, Felzien L K, Betts J C, Leung K, Beach D H, Nabel G J. Regulation of NF-κB by cyclin-dependent kinases associated with the p300 coactivator. Science. 1997;275:523–527. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5299.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Perkins N D, Schmid R M, Duckett C S, Leung K, Rice N R, Nabel G J. Distinct combinations of NF-κB subunits determine the specificity of transcriptional activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:1529–1533. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.5.1529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Plaksin D, Baeuerle P A, Eisenbach L. KBF1 (p50 NF-κB homodimer) acts as a repressor of H-2Kb gene expression in metastatic tumor cells. J Exp Med. 1993;177:1651–1662. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.6.1651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ricciardi, R. P. Adenovirus transformation and tumorigenicity. In P. Seth (ed.), Adenoviruses: from basic research to gene therapy applications, in press. Landes Publishing, Georgetown, Tex.

- 57.Ruben S M, Dillon P J, Schreck R, Henkel T, Chen C-H, Maher M, Baeuerle P A, Rosen C A. Isolation of a rel-related human cDNA that potentially encodes the 65-kD subunit of NF-κB. Science. 1991;251:1490–1493. doi: 10.1126/science.2006423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schmitz M L, Baeuerle P A. The p65 subunit is responsible for the strong activating potential of NF-κB. EMBO J. 1991;10:3805–3817. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb04950.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schrier P I, Bernards R, Vaessen R T M J, Houweling A, van der Eb A J. Expression of class I major histocompatibility antigens switched off by highly oncogenic adenovirus 12 in transformed rat cells. Nature (London) 1983;305:771–775. doi: 10.1038/305771a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Segars J H, Nagata T, Bours V, Medin J A, Franzoso G, Blanco J C G, Drew P D, Becker K G, An J, Tang T, Stephany D A, Neel B, Siebenlist U, Ozato K. Retinoic acid induction of major histocompatibility complex class I genes in NTera-2 embryonal carcinoma cells involves induction of NF-κB (p50-p65) and retinoic acid receptor β-retinoid X receptor β heterodimers. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:6157–6169. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.10.6157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shapiro D J, Sharp P A, Wahli W W, Keller M J. A high-efficiency HeLa cell nuclear transcription extract. DNA. 1988;7:47–55. doi: 10.1089/dna.1988.7.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Stancovski I, Baltimore D. NF-κB activation: the IκB kinase revealed? Cell. 1997;91:299–302. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80413-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tanaka K, Isselbacher K J, Khoury G, Jay G. Reversal of oncogenesis by the expression of a major histocompatibility complex class I gene. Science. 1985;228:26–30. doi: 10.1126/science.3975631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Thanos D, Maniatis T. NF-κB: a lesson in family values. Cell. 1995;80:529–532. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90506-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Traenckner E B-M, Wilk S, Baeuerle P A. A proteasome inhibitor prevents activation of NF-κB and stabilizes a newly phosphorylated form of IκBα that is still bound to NF-κB. EMBO J. 1994;13:5433–5441. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06878.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Urban M B, Schreck R, Baeuerle P A. NF-κB contacts DNA by a heterodimer of the p50 and p65 subunit. EMBO J. 1991;10:1817–1825. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07707.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Vasavada R, Eager K B, Barbanti-Brodano G, Caputo A, Ricciardi R P. Adenovirus type 12 early region 1A proteins repress class I HLA expression in transformed human cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:5257–5261. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.14.5257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wang H-G H, Yaciuk P, Ricciardi R P, Green M, Yokoyama K, Moran E. The E1A products of oncogenic adenovirus serotype 12 include amino-terminally modified forms able to bind to the retinoblastoma protein but not p300. J Virol. 1993;67:4804–4813. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.8.4804-4813.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Whiteside S T, Israël A. IκB proteins: structure, function, and regulation. Semin Cancer Biol. 1997;8:75–82. doi: 10.1006/scbi.1997.0058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yewdell J W, Bennink J R, Eager K B, Ricciardi R P. CTL recognition of adenovirus-transformed cells infected with influenza virus: lysis by anti-influenza CTL parallels adenovirus-12-induced suppression of class I MHC molecules. Virology. 1988;162:236–238. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(88)90413-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhong H, Voll R E, Ghosh S. Phosphorylation of NF-κB p65 by PKA stimulates transcriptional activity by promoting a novel bivalent interaction with the coactivator CBP/p300. Molec Cell. 1998;1:661–671. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80066-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]