Abstract

Gonadal differentiation is dependent upon a molecular cascade responsible for ovarian or testicular development from the bipotential gonadal ridge. Genetic analysis has implicated a number of gene products essential for this process, which include Sry, WT1, SF-1, and DAX-1. We have sought to better define the role of WT1 in this process by identifying downstream targets of WT1 during normal gonadal development. We have noticed that in the developing murine gonadal ridge, wt1 expression precedes expression of Dax-1, a nuclear receptor gene. We document here that the spatial distribution profiles of both proteins in the developing gonad overlap. We also demonstrate that WT1 can activate the Dax-1 promoter. Footprinting analysis, transient transfections, promoter mutagenesis, and mobility shift assays suggest that WT1 regulates Dax-1 via GC-rich binding sites found upstream of the Dax-1 TATA box. We show that two WT1-interacting proteins, the product of a Denys-Drash syndrome allele of wt1 and prostate apoptosis response-4 protein, inhibit WT1-mediated transactivation of Dax-1. In addition, we demonstrate that WT1 can activate the endogenous Dax-1 promoter. Our results indicate that the WT1–DAX-1 pathway is an early event in the process of mammalian sex determination.

The process of sex determination is considered a paradigm for how gene action can influence developmental fate. Mutations that cause sex reversal have proved to be important for identifying genes involved in mammalian sex determination (5, 19, 21). In mammals, both Sry and Sox9 direct or initiate testis determination (15, 25, 50). The Sry gene is expressed within cells of the male genital ridge during a narrow window between ∼10.5 and 12.5 days post coitum (dpc). This expression is not dependent on the presence of germ cells and is likely to occur in cells of the supporting lineage, resulting in their differentiation into Sertoli cells rather than follicle cells. Neither Sry nor Sox9 is expressed in the ovary.

Shortly after testis development is triggered, Sertoli cells align into visible cord-like structures (the testis cords) and begin to express Müllerian inhibiting substance (MIS), a transforming growth factor β-like hormone which causes the regression of the Müllerian ducts, the anlagen of the female reproductive tract (10). In the absence of MIS, the Müllerian ducts will develop into the oviducts, uterus, and upper vagina. The generation of mice lacking a functional MIS gene has confirmed that the primary role of this hormone is in the regression of the Müllerian ducts and that MIS plays no critical role in testicular determination per se (4).

The orphan nuclear receptor, steroidogenic factor 1 (SF-1), has been directly implicated in regulating MIS gene expression by binding to a conserved upstream regulatory region (46). In addition, SF-1 is postulated to play a role in regulating the steroid hydroxylases and aromatase and in the adult mouse is expressed in all primary steroidogenic tissues, including the adrenal cortex, testicular Leydig cells, ovarian theca and granulosa cells, and corpus luteum (for a review, see reference 35). In the developing mouse embryo, SF-1 is expressed in the urogenital ridges of both sexes beginning at 9.5 dpc and is also present in fetal Sertoli cells (17). Targeted disruption of the Ftz-F1 gene in mice, which encodes SF-1, has demonstrated that SF-1 is essential for development of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis and is essential for normal testis differentiation (28).

Targeted disruption of the Wilms’ tumor suppressor gene, wt1, also produces mice displaying an arrest of gonadal development (26). During development, the wt1 gene is expressed in the indifferent gonad and then becomes localized to the Sertoli cells of the testis and granulosa and epithelial cells of the ovary (38, 39). In humans, loss-of-function germ line mutations in the wt1 gene are associated with mild effects on sexual differentiation (hypospadias and cryptorchidism) (7, 37), whereas germ line wt1 mutations producing dominant-negative products are associated with severe effects on gonadal development and sexual differentiation (male pseudohermaphroditism) (7, 36). Although the expressivity of the phenotypes associated with germ line wt1 mutations can vary, these data indicate that WT1 plays a critical role in both gonadal development and sexual differentiation. Recent experiments by Nachtigal et al. (33) have suggested that WT1 and SF-1 synergize to promote MIS expression during sexual differentiation.

The wt1 gene encodes a protein having many characteristics of a transcription factor, including a glutamine-proline-rich amino terminus, nuclear localization, and four Cys2-His2 zinc finger motifs (42). The three carboxy-terminal-most zinc fingers have 64% identity to the three zinc fingers of the early growth response gene-1 (EGR-1). The mRNA contains two alternative sites of translation and two alternatively spliced exons and undergoes RNA editing, thus potentially encoding 16 different protein isoforms with predicted molecular masses ranging from 52 to 65 kDa (42). The functions of the alternative translation initiation event, the RNA editing, and the first alternative splicing event (exon V) have not been well defined, although exon V can repress transcription when fused to a heterologous DNA binding domain (42). Alternative splicing of exon IX inserts or removes three amino acids (±KTS) between zinc fingers III and IV and changes the DNA binding specificity of WT1 (42). The WT1(−KTS) isoforms can bind to two DNA motifs: (i) a GC-rich motif, 5′ G(G/Y)GTGGGC(G/C) 3′, similar to the EGR-1 binding site (41), and (ii) a (5′ TCC 3′)n-containing sequence (52). The DNA binding properties of the WT1(+KTS) isoforms are not well understood, since no high-affinity, specific binding site has been elucidated for these splice variants. A number of genes involved in growth regulation and cellular differentiation contain WT1 binding sites within their promoters, and their expression can be modulated by WT1 in transfection assays (42). The wt1 gene product has the potential to mediate both transcriptional repression and activation (42).

The Dax-1 (for DSS [dosage-sensitive sex reversal]-AHC [adrenal hypoplasia congenita] critical region on the X chromosome, gene 1) gene is an orphan nuclear receptor localized to chromosome Xp21 and is thought to be important for the development of the adrenal gland and the reproductive system (3, 54). Mutations in the Dax-1 gene are associated with X-linked adrenal hypoplasia and hypogonadotropic hypogonadism (32), whereas duplication of a 160-kbp genomic region (the DSS critical region), encompassing the Dax-1 gene, is associated with male-to-female sex reversal (3). Since XY individuals with Dax-1 deleted develop as males, it has been proposed that this gene is required for ovarian, but not testicular, development (3). In the mouse, DAX-1 is first expressed in the somatic component of the genital ridge at 10.5 to 11 dpc and peaks at around 12 dpc (48). In males, the levels of DAX-1 decrease dramatically as the testis cords begin to appear, whereas in females, Dax-1 continues to be expressed throughout the gonad after 12.5 dpc (48). DAX-1 binds to DNA hairpin structures and can act as a repressor of StAR (steroidogenic acute regulatory protein) gene expression, an enzyme involved in regulation of steroid production (55). DAX-1 can also inhibit steroidogenesis by a second mechanism—by binding to SF-1 and suppressing its activation properties (18). This interaction occurs through a repressor domain within the carboxy terminus of SF-1, and DAX-1 appears to serve as an adaptor molecule capable of recruiting N-CoR (nuclear receptor corepressor) to SF-1 and extending the range of corepressor function (13).

The presence of WT1 binding sites within the Dax-1 promoter (this report), the relative temporal and spatial expression of both genes in the fetal gonad, and the postulated role of both genes in gonadal differentiation raised the possibility that WT1 might regulate Dax-1 expression. In this report, we provide evidence in support of this hypothesis and suggest that WT1 is responsible for the initial activation of Dax-1 expression early in differentiation of the indifferent gonad, thus triggering a regulatory gene hierarchy implicated in sex determination.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials and general methods.

Restriction endonucleases, calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase, the Klenow fragment of DNA polymerase I, T4 DNA ligase, and T4 DNA polymerase were purchased from New England Biolabs. d-Threo-[dichloroacetyl-1-14C]chloramphenicol (54.0 Ci/mmol) was purchased from Amersham-Pharmacia. [γ-32P]ATP and [α-32P]dCTP (3,000 Ci/mmol) were purchased from New England Nuclear.

Preparation of plasmid DNA, restriction enzyme digestion, agarose gel electrophoresis of DNA, DNA ligation, and bacterial transformations were carried out by standard methods (reference 45 and references therein). Subclones of DNA PCR amplifications were always sequenced by the chain termination method with double-stranded DNA templates to ensure the absence of mutations.

Plasmid construction.

The murine and human Dax-1 promoters were cloned by PCR amplification from genomic DNA. The amplification primers used for this purpose were: (i) mDAX(s) (5′ GGCAAGCTTTAGTTCCAGTGCTGAG 3′) (a HindIII restriction site is underlined) and mDAX(as) (5′ GAACTGCAGATGGCCTGAGGCTCCT 3′) (a PstI site is underlined) for the murine promoter and (ii) hDAX(s) (5′ GGCAAGCTTGAGCTCCCACGCTGCTGT 3′) (a HindIII site is underlined) and hDAX(as) (5′ GAACTGCAGATGGCCCGCGGCGCCC 3′) (a PstI site is underlined) for the human promoter. Both promoter fragments were cloned into the HindIII-PstI sites of the promoterless pCAT expression vector (Promega). The sequences of the two promoter fragments used in this study are shown in Fig. 1B.

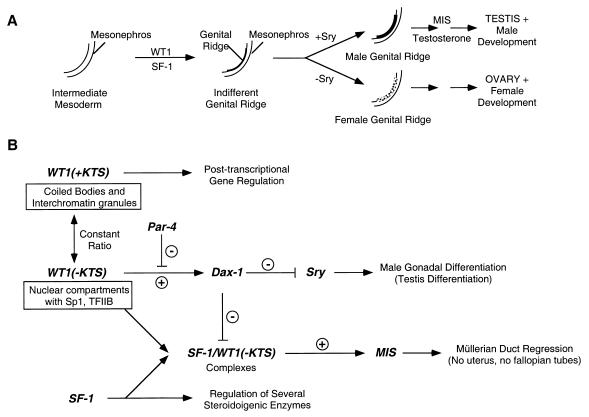

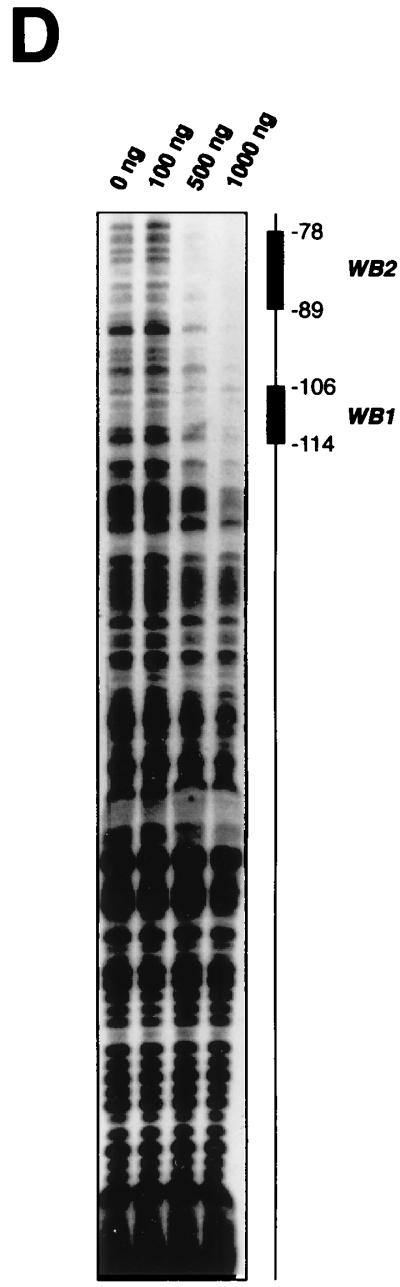

FIG. 1.

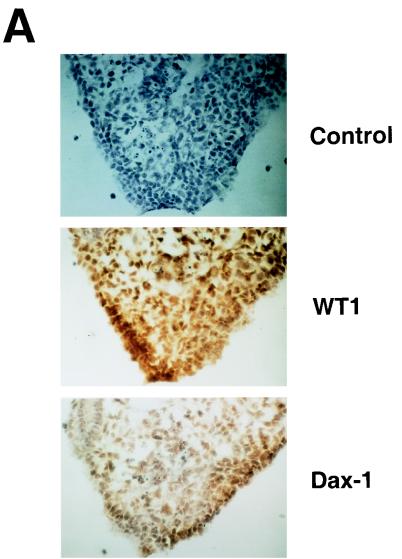

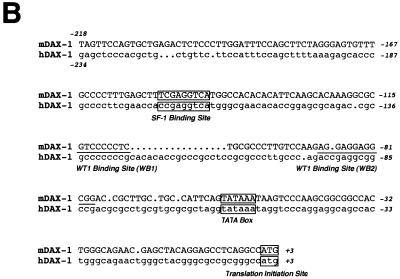

Comparison of WT1 and DAX-1 expression in the fetal gonad and EMSA analysis of the Dax-1 promoter. (A) Immunohistochemical analysis demonstrates colocalization of WT1 and DAX-1 signals to pre-Sertoli cells in 11.5-dpc murine testis. (B) Alignment of the murine (mDAX-1) (48) and human (hDAX-1) (54) sequences upstream of the ATG translation initiation codon. The dots represent regions which are not conserved. The characteristic TATAA box and a putative SF-1 binding site are boxed, and two potential WT1 recognition elements are underlined. The nucleotide numbering is relative to the adenosine residue of the ATG initiation codon, which is numbered as +1. (C) EMSA eliciting the DNA binding properties of WTZF(±KTS) isoforms to the Dax-1 promoter. The Dax-1 promoter was divided into two MscI fragments of 77 and 143 bp. Following preparation of radiolabeled probes, EMSAs were performed with recombinant WTZF protein as described in Materials and Methods. The nature of the input probe (5′MSC or 3′MSC), as well as the amount of recombinant protein used for the EMSA, is indicated above the gels. The position of migration of the free probe and protein-DNA complexes is indicated. Protein-DNA complexes were resolved on nondenaturing 4% polyacrylamide (acrylamide/bisacrylamide ratio, 37/1) gels electrophoresed at 4°C in 0.5× TBE (44.5 mM Tris-HCl, 44.5 mM boric acid, 1 mM EDTA). (D) DNase I footprint analysis of putative WT1 binding sites in the mDax-1 promoter. A single end-labeled probe (nucleotides +3 to −141) was incubated with increasing amounts of purified recombinant WTZF(−KTS) protein (indicated above the gel). After digestion with DNase I, the samples were separated on a urea–8% polyacrylamide gel. A sequencing ladder was electrophoresed in parallel to determine the sizes of the observed fragments. Shown are the footprints obtained on the WB1 (potential WT1 binding site 1) and WB2 (potential WT1 binding site 2) sites. Although the protected region is larger than the indicated footprint, clearly WB1 and WB2 sites are encompassed.

Several mutants of pmDax-1/CAT were generated in which putative WT1 binding sites were eliminated (see Fig. 4). These mutants were generated by amplification of the respective fragments by PCR, followed by splicing of the regions by a PCR overlap extension method (11). To construct mDAX-1/CAT [WB1m], in which the putative upstream WT1 binding site (−114GTCCCCC TC−106) is changed to −114GTCACCCTCT−106 (the altered nucleotide is underlined), initial PCRs were performed with primers mDAX(s) and WB1m(as) (5′ CTTGGACAAGGGCGCAGAGGGTGACGCGCCTTTGTGCTTG 3′), which generated a fragment containing the WB1 mutation. Primers WB1m(s) (5′ CAAGCACAAAGGCGCGTCACCCTCTGCGCCCTTGTCCAAG 3′) and mDAX(as) were used to generate a second fragment containing the remaining downstream portion of the promoter. A third PCR for generating mDAX-1/CAT [WB1m] was performed with both gel-purified primary PCR products as templates and primers mDAX(s) and mDAX(as).

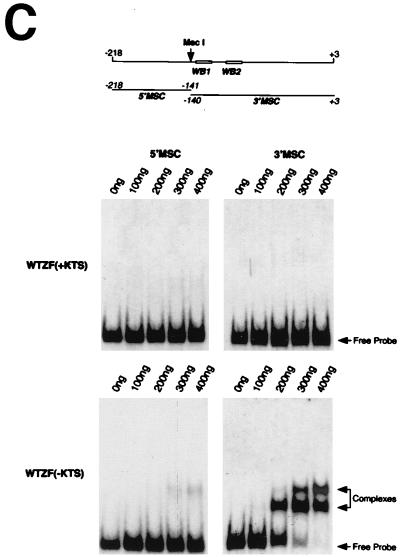

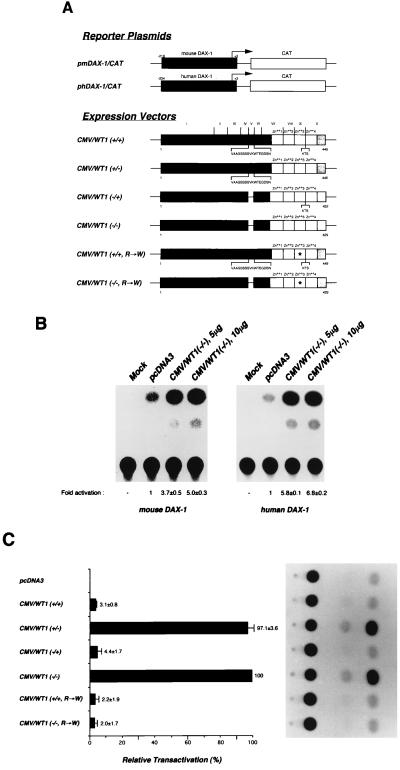

FIG. 4.

Mutational analysis of the Dax-1 promoter and inhibition of WT1-mediated transactivation by DDS alleles of wt1 and par-4 genes. (A) Mutational analysis of WT1 binding sites within the Dax-1 promoter. Mutations were introduced by PCR primer-directed mutagenesis to alter site WB1 (5′ GTCCCCCTC 3′) to WB1(m) (5′ GTCACCCTC 3′) and site WB2 (5′ AGGAGGAGGCGG 3′) to WB2(m) (5′ A---GG 3′) (changes are indicated in boldface, and a dash represents a deletion). Open box, wild-type WT1 binding site; filled box, mutated WT1 binding site. Transfections were performed with 1 μg of reporter plasmid, 10 μg of CMV/WT1(−/−) expression vector, and 2 μg of CMV/β-gal. CAT and β-galactosidase assays were performed with whole-cell extracts from transiently transfected COS-7 and 293T cells. The values represent the average fold activations of at least two experiments performed in duplicate. (B) DDS alleles inhibit WT1-mediated transactivation. One microgram of the pmDAX-1/CAT reporter plasmid was cotransfected into COS-7 cells with 5 μg of CMV/WT1(−/−) and the indicated amounts of WT1(−/−, R→W). The total transfected DNA concentration was kept constant by the addition of empty expression vector, pcDNA3, to make up differences in amounts of expression vector between tubes. CAT activity was determined from whole-cell extracts prepared 48 h after transfection. The standard deviation for each experiment is shown by an error bar. (C) Par-4 inhibits transcriptional activation of Dax-1 by WT1(−/−) in a dose-dependent fashion. For these experiments, 5 μg of WT1(−/−) expression vector was cotransfected with 1 μg of pmDAX-1/CAT and the indicated amounts of Par-4 expression vector. The total transfected DNA concentration was kept constant by the addition of empty expression vector, pcDNA3, to make up differences in amounts between tubes. CAT activity was determined from whole-cell extracts prepared 48 h after transfection. The standard deviation for each experiment is shown by an error bar.

The reporters pmDAX-1/CAT [WB2m] and mDAX-1/CAT [WB1m][WB2m] were generated in a similar fashion. PCRs for generating mDAX-1/CAT [WB2m] involved using primers WB2(m)(as) (5′ AGCAAGCGGTCCTCTTGGACAAG 3′) in combination with mDAX(s) and WB2(m)(s) (5′ CTTGTCCAAGAGGACCGCTTGCT 3′) in conjunction with mDAX(as). Following gel purification of the products, they were mixed together and an additional PCR was performed with primers mDAX(s) and mDAX(as). For generating mDAX-1/CAT [WB1m][WB2m], primer pair mDAX(s) and WB2(m)(as) and primer pair WB2(m)(s) and mDAX(as) were used to generate the primary PCR products mDAX-1/CAT [WB1m] as a template. The second amplification was performed with gel-purified primary PCR products as templates and primers mDAX(s) and mDAX(as). The construction of WT1 expression vectors used in this study has been previously described (37, 38).

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs).

A truncated domain of the WT1 protein consisting of zinc fingers I to IV fused to a His6 tag was overexpressed and purified from Escherichia coli. Essentially, sequences coding for the WT1 carboxy terminus (codons 297 to 449) were replaced by a synthetic gene fragment generated by overlap extension PCR in order to obtain favorable codon usage for expression in bacteria. Following cloning into pET15B (Novagen) and introduction into E. coli BL21(pLysS), proteins were induced under the recommended conditions (Novagen). The proteins were purified by nickel chelate affinity chromatography (Qiagen, Mississagua, Ontario, Canada) under native conditions as recommended by the manufacturer. Eluted proteins were dialyzed against a buffer containing 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 70 mM KCl, 12% glycerol, 0.05% Nonidet P-40, 100 μM ZnSO4, and 0.5 mM dithiothreitol. The purity and integrity of the fusion proteins were assessed by Coomassie blue staining of sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gels.

Probes for EMSAs were prepared by PCR or from synthetically generated oligonucleotides. The sequences of the probes were as follows: WB1, 5′ CAAGCACAAAGGCGCGTCCCCCTCTGCGCCCTTGTCCAAG 3′ (the putative WT1 binding site is underlined); WB1(m), 5′ CAAGCACAAAGGCGCGTCACCCTCTGCGCCCTTGTCCAAG 3′ (the mutation introduced into the putative WT1 binding site is in boldface); WB2, 5′ CAAGAGGAGGAGGCGGACCGC 3′] (two overlapping putative WT1 sites are shown, one underlined and the other in italics); WB2(m), 5′ CTTGTCCAAGAGGACCGCTTGCT 3′, containing a 9-bp deletion which removes the cores of both overlapping WT1 sites; WTE, 5′ GAGTGCGTGGGAGTAGAA 3′ (the WT1 recognition site is underlined); and WTE(m), 5′ GAGTGCGTGAGAGTAGAA 3′ (the altered nucleotide is indicated in boldface). Synthetic oligonucleotide probes to the Dax-1 promoter region were prepared by end labeling annealed complimentary oligonucleotides with [γ-32P]ATP by using T4 polynucleotide kinase. EMSAs were performed with recombinant WT1 zinc finger (WTZF) proteins (+KTS and −KTS isoforms) for 30 min at 4°C in binding buffer {50 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 50 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM ZnSO4, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 20% glycerol, and 1 μg of poly[(dI · dC) · (dI · dC)]}. Following binding, the reaction mixtures were electrophoresed on a 4% polyacrylamide gel (acrylamide/bisacrylamide ratio, 37:1) in 0.5× TBE (44.5 mM Tris-HCl, 44.5 mM boric acid, 1 mM EDTA) buffer at 150 V for 2 to 3 h at 4°C. The gels were dried and exposed to Kodak X-Omat film at room temperature (RT).

Cell culture, transfections, and CAT assays.

COS-7 and 293T cell lines were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (Gibco-BRL), penicillin, and streptomycin. For transient transfections, cells were plated at a density of 2 × 105 to 5 × 105 cells per 100-mm-diameter dish 24 h prior to transfection. The cells were transfected by the calcium phosphate precipitation method (45). Individual DNA precipitates were adjusted to contain equal amounts of total DNA by the addition of the empty expression vector pcDNA3. To normalize for transfection efficiency, the cells were cotransfected with 2 μg of pRSV/β-gal. At 48 h after transfection, the cells were harvested and extracts were prepared and assayed for β-galactosidase and chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) activity (45). Following thin-layer chromatography analysis, regions containing acetylated [14C]chloramphenicol, as well as unacetylated [14C]chloramphenicol, were quantitated by direct analysis on a phosphorimager (Fujix BAS 2000). All CAT activity values were normalized against β-galactosidase values.

DNase I footprinting.

The Dax-1 promoter region was isolated from plasmid pmDAX-1/CAT by digestion with HindIII and SmaI, which released a 253-bp fragment (Fig. 1B). This fragment was isolated with the QIAEX II gel extraction kit (Qiagen). This fragment was gel purified and labeled with [α-32P]dCTP (3,000 Ci/mmol) by the Klenow fill-in reaction. Recombinant WTZF(−KTS) protein was preincubated for 15 min at RT with 1 μg of poly[(dI · dC) · (dI · dC)] in 50 μl of binding buffer prior to the addition of ∼20,000 cpm of labeled Dax-1 fragment. After an additional 15 min at RT, 0.4 U of DNase I (Boehringer, Mannheim, Germany) was added and the incubations were continued for another 60 s. DNase I digestion was stopped by adding 200 μl of stop buffer (5 μg of tRNA, 0.3 M sodium acetate [pH 5.2]) and 2.5 volumes of ethanol. After 20 min at −70°C, the precipitate was collected by centrifugation at 12,000 × g at 4°C for 20 min. The precipitates were resuspended in 90% formamide and analyzed on a 6% polyacrylamide (acrylamide/bisacrylamide ratio, 18:1)–8 M urea gel.

Total RNA isolation, S1 nuclease analysis, and Northern blotting analysis.

An HEK293 cell line expressing the WT1(+/−) isoform under tetracycline regulation was established based on the expression plasmids of Gossen and Bujard (16). HEK293 cells were first transfected with p15-3/tTA (a cytomegalovirus (CMV)-driven plasmid producing a Repressor/tTA fusion protein) and SVneo. A neomycin-resistant-colony which demonstrated tight tetracycline regulation of a test reporter plasmid (p10-3/β-gal) was then used for a second round of transfection with CMV-Hygro and p10-3/WT1(+/−). Twelve colonies resistant to hygromycin were tested for wt1 protein expression, and a colony showing inducibility of WT1 with no leakiness of expression (as assessed by Western blotting [see Fig. 5]) was chosen for the experiments reported here.

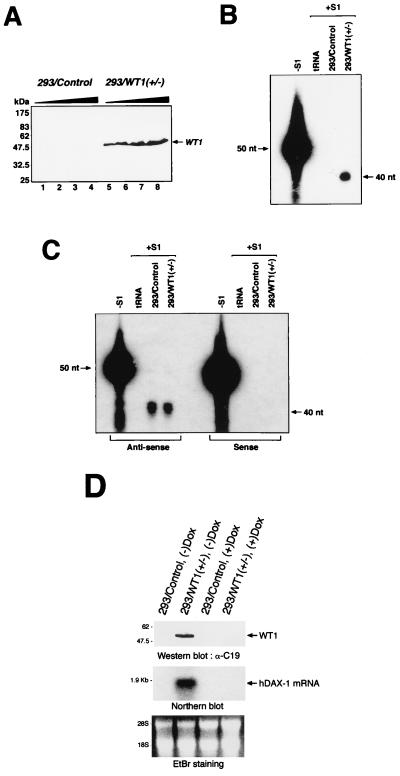

FIG. 5.

Activation of the endogenous Dax-1 promoter by WT1. (A) Western blot analysis of WT1 expression in 293 cells and in 293 cells harboring the WT1 gene under control of the inducible tetracycline promoter. Total cell extracts were prepared with 293/Control or 293/WT1(+/−) cells by sonication. Extracts were resolved by SDS–10% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membrane, and immunoblotted with anti-WT1 antibody (C-19). The blot was preblocked in TBST (10 mM Tris-Cl [pH 8.0], 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% Tween-20) containing 5% skim milk for 1 h at 4°C and probed with anti-mouse antibodies (Santa Cruz) (1:1,500). Following extensive washing with TBST, the blot was incubated with a horseradish peroxidase conjugated anti-mouse antibody (1:1,500) (Santa Cruz). The immune complexes were visualized with an ECL kit from Amersham. The positions of migration of the prestained molecular mass markers (New England Biolabs) are indicated to the left. Either 90 (lanes 1 and 5), 180 (lanes 2 and 6), 360 (lanes 3 and 7), or 540 (lanes 4 and 8) μg of total cell lysate was analyzed. (B) Quantitation of Dax-1 mRNA levels in RNA preparations from 293/Control or 293/WT1(+/−) cells. S1 analysis was performed with a single-stranded radioactive synthetic oligonucleotide probe directed against nucleotides +1 to +40 (relative to the translation start site) of the human Dax-1 gene mRNA as described in Materials and Methods. The products of the protection were visualized by autoradiography by exposing the dried gel to X-Omat film at −70°C overnight with an intensifying screen. (C) Quantitation of GAPDH mRNA levels in RNA preparations from 293/Control or 293/WT1(+/−) cells. The products of the protection assay were analyzed on a 6% polyacrylamide–8 M urea gel, and size determinations were made by comparing the positions of migration of the products with a set of sequencing reactions which had been electrophoresed in parallel. The free probe lane is indicated as −S1. The RNA sources incubated with the S1 probes are denoted at the top as tRNA, 293/Control, or 293/WT1(+/−). The products of the protection were visualized by autoradiography by exposing the dried gel to X-Omat film at −70°C overnight with an intensifying screen. (D) Quality assessment of WT1-induced Dax-1 mRNA. (Upper gel) Following incubation of 293/Control or 293/WT1(+/−) cells for 36 h in media lacking or containing 1 μg of doxycycline/ml (+/− Dox), cells were harvested for preparation of total protein and RNA extracts. Recombinant WT1 protein was visualized by immunoblotting, as described for panel A. (Middle gel) Total RNA was fractionated on a 6% formaldehyde–1.2% agarose gel, transferred to a nylon membrane, and probed with human Dax-1 cDNA as described in Materials and Methods. (Lower gel) The ethidium bromide (EtBr) staining of the agarose gel used for Northern blotting is shown to demonstrate that equal amounts of total RNA were loaded in each lane.

Total RNA was prepared from 293 cells by the guanidine isothiocyanate-cesium chloride gradient method (45). Probes used in the S1 analysis were Dax-HIT (5′ AGAGGATGCTGCCCTGCCACTGGTGGTTCTCGCCCGCCATAAAAAAAAAA 3′), a 50-nucleotide oligonucleotide consisting of 40 nucleotides (+1 to +40 relative to the translation start site) complementary to the human Dax-1 mRNA 10 noncomplementary adenosine residues at the 3′ end; GAPDH-HIT(AS) (5′ GGGGTCATTGATGGCAACAATATCCACTTTACCAGAGTTATTTTTTTTTT 3′), a 50-nucleotide probe containing 40 nucleotides complementary to the glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) transcript (nucleotides +69 to +108 relative to the translation start site) and 10 noncomplementary thymidine residues; and GAPDH-HIT(S) (5′ GGGCTGCTTTTAACTCTGGTAAAGTGGATATTGTTGCCATAAAAAAAAAA 3′), a 50-nucleotide oligonucleotide containing 40 nucleotides from the sense strand of the GAPDH mRNA (nucleotides +59 to +98 relative to the translation start site) and 10 noncomplementary adenosine residues. Oligonucleotide probes were radiolabeled with [γ-32P]ATP (6,000 Ci/mmol) and T4 polynucleotide kinase. S1 nuclease analyses with gel-purified probes were performed as described previously (45). Briefly, 50 μg (for human Dax-1) or 15 μg (for GAPDH controls) of total RNA was ethanol precipitated with ∼30,000 cpm of radiolabeled probe, resuspended in 20 μl of S1 hybridization solution {80% deionized formamide, 40 mM PIPES [piperazine-N-N′-bis(2-ethanesulfonic acid)] [pH 6.4], 400 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA [pH 8.0]}, denatured at 90°C for 10 min, and hybridized at 30°C overnight. The samples were treated with 250 U of S1 nuclease (Boehringer) at 60°C for 30 min, ethanol precipitated, and analyzed on a 6% polyacrylamide (acrylamide/bisacrylamide ratio, 18:1)–8 M urea gel.

Total RNA isolated from control 293 and WT1-expressing 293 cells was also analyzed by Northern blotting. Briefly, 20 μg of total RNA was fractionated on a 6% formaldehyde–1.2% agarose gel and transferred to nylon membrane (Hybond-N+; Amersham) by the capillary transfer method utilizing 20× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate, pH 7.0). Following cross-linking of RNA, the blot was probed with a 32P-labeled human Dax-1 cDNA probe (∼1.5-kbp fragment obtained by EcoRI/XhoI digest of pBKCMV human Dax-1) (∼9 × 107 cpm/μg) which had been prepared by random priming (45). Probing was performed at a probe concentration of 106 cpm/ml at 42°C in hybridization buffer (50% formamide, 5× SSPE [1× SSPE is 0.15 M NaCl, 0.01 M NaH2PO4, 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.4], 2× Denhardt’s reagent, 0.1% SDS, 100 μg of denatured, fragmented salmon sperm DNA/ml). The blot was then washed once in 2× SSC–0.1% SDS at room temperature and twice in 0.2× SSC–0.1% SDS at 55°C and subjected to autoradiography.

Immunohistochemical analysis of WT1 and DAX-1 in the fetal gonads.

Mouse embryos (age, 11.5 dpc) were dissected and stored at −70°C without further fixation. Sections (7 to 10 μm thick) from tissues were cut with a cryostat, transferred onto glass slides, and fixed overnight at −20°C in methanol-EGTA. Tissue was preblocked with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)-methanol-H2O2 (59.5%/40%/0.5%) for 20 min at RT. After two washing steps in H2O and one rinse in PBS, the sections were buffered for 30 min in PBS-normal goat serum (10:1) at RT in a humidified chamber. Then anti-WT1 180 or anti-Dax-1 antibody (Santa Cruz) was applied to different sections in different dilutions ranging from 1:10 to 1:2,000, and the sections were incubated in a humidified chamber overnight at 4°C. The tissue sections were washed three times with PBS and then overlaid with biotinylated anti-rabbit antibody diluted in PBS (1:100) for 30 min. This incubation was again followed by washing the sections in PBS, after which the peroxidase reaction was performed for 20 min with the ABC Immunostain (Santa Cruz) solution and visualized with a diaminobenzidine coloring solution containing 0.01% H2O2 for 30 s to 4 min. The staining reaction was stopped by immersing the slides in distilled water, followed by a short counterstain in hematoxylin. The tissue sections were dehydrated by rinsing them in a series of washes with increasing ethanol concentrations (70 to 100%), washing them in xylene, and mounting them in Permount medium.

RESULTS

DAX-1 and WT1 are coexpressed in the fetal gonad.

The wt1 gene is expressed very early during fetal development in both male and female indifferent gonads. WT1 transcripts can be detected in the urogenital ridge as early as 9 dpc (1), and levels remain high during development of this organ (38). On the other hand, Dax-1 gene expression in the murine gonad begins later, at ∼10.5 dpc, and peaks at ∼11.5 to 12.5 dpc in both males and females, as assessed by RNase protection experiments (48). In the fetal gonad, WT1 is expressed in pre-Sertoli and Sertoli cells (31, 38, 39). Immunohistochemical analysis of DAX-1 in the fetal gonad indicates that it is expressed in the same cells as WT1 in the 11.5-dpc testis (Fig. 1A). Given the essential roles of both proteins for normal sexual development, their colocalization in cells of the indifferent gonad, and their temporal expression profiles, we wished to test whether WT1 could influence Dax-1 gene expression.

The Dax-1 promoter contains two WT1 responsive elements.

The sequences of the human and murine Dax-1 promoters have been previously elucidated (48, 54). The structure of the murine Dax-1 gene has been determined by restriction mapping and sequence comparison of genomic and cDNA clones (48). The immediate 5′ flanking regions of the murine and human Dax-1 genes contain a putative TATA box, an SF-1 binding site, and two potential WT1 binding sites (designated WB1 and WB2 [Fig. 1B]). EMSAs have demonstrated that recombinant SF-1 protein is able to bind to the putative SF-1 response element, although it remains to be established whether SF-1 can regulate Dax-1 expression (9).

WT1 can bind to DNA elements showing variations on the EGR-1 consensus binding site, 5′ GXGXGGGXG 3′ (for a review, see reference 42). Three such elements are delineated in the murine Dax-1 promoter (Fig. 1B), one at positions −114 to −106 (antisense orientation, 5′ GAGGGGGAC 3′) and two overlapping elements between nucleotides −89 and −78 (5′ AGGAGGAGG 3′ and 5′ AGGAGGCGG 3′). To experimentally assess whether WT1 can bind to these putative recognition elements, we performed EMSAs with two genomic fragments derived from the murine promoter (Fig. 1C, upper panel) in the presence of recombinant WT1 protein [WTZF(+KTS) and WTZF(−KTS) isoforms]. The probes used were generated by MscI digestion of the murine Dax-1 promoter region and were named 5′MSC and 3′MSC, encompassing nucleotides −218 to −141 and −140 to +3, respectively. Protein-DNA complexes are observed only with WTZF(−KTS) protein and the 3′MSC probe (Fig. 1C). The appearance of two complexes with this probe in the presence of WTZF(−KTS) protein suggests the existence of at least two WT1 recognition elements within the murine Dax-1 promoter (Fig. 1C). Given the overlapping nature of the two WT1 binding sites at −78 to −87 and the likelihood that only one WTZF molecule can bind to this region at any given time, our studies do not attempt to distinguish between these two sites; rather we have treated this region as harboring a single WT1 binding site, called WB2. To more accurately map the positions of the WT1 binding sites, DNase I footprinting assays were performed. For these purposes, a 32P-labeled DNA fragment encompassing the region from −218 to +3 was employed. Increasing amounts of WTZF(−KTS) protein added to the footprinting reaction led to the protection of a region between −114 and −78 on the Dax-1 promoter (Fig. 1D). The two WT1 binding sites, WB1 and WB2, map to this region (Fig. 1D). None of the other regions of the mouse Dax-1 promoter showed protection from DNase I cleavage, indicating the presence of two functional WT1 binding sites within the Dax-1 promoter—consistent with the EMSA data presented above.

Specificity of binding of WT1 to the Dax-1 promoter.

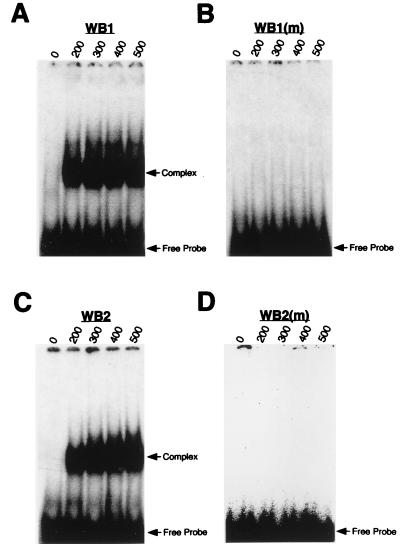

To demonstrate the specificity of the interaction between WTZF(−KTS) and the putative WT1 binding sites, WB1 and WB2, a series of gel shift experiments were performed with synthetic oligonucleotides containing the WB1 or WB2 sequence. A single protein-DNA complex was obtained with oligonucleotides harboring the wild-type WB1 or WB2 sequence (Fig. 2A and C). This interaction was abrogated when either (i) a cytosine residue (underlined) in WB1 (5′ GTCCCCCTC 3′), known to be necessary for WT1 binding (36), was changed to an adenosine residue (underlined) in WB1(m) (5′ GTCACCCTC 3′) (compare Fig. 2A and B) or (ii) a deletion was introduced into the overlapping WT1 sites in WB2 (compare Fig. 2C and D).

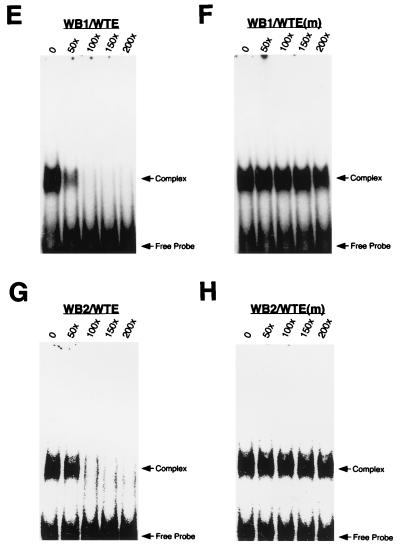

FIG. 2.

Specificity of WT1–Dax-1 complexes. (A to D) WTZF(−KTS) recombinant protein was used in EMSAs with oligonucleotides containing the sequences corresponding to regions designated WB1 (A), WB1(m), a mutant of WB1 (B), WB2 (C), and WB2(m), a deletion mutant (D). The nucleotide sequences of the oligonucleotides are presented in Materials and Methods. The amount of recombinant WTZF protein used in the EMSAs was titrated and is indicated (in nanograms) above each lane. (E to H) Competition experiments were performed in the presence of increasing amounts (the molar excess is indicated above each lane) of an unlabeled oligonucleotide harboring either the WTE recognition site (E and G) or a mutant version of WTE (F and H). Specific complexes were preformed between WTZF(−KTS) protein and an oligonucleotide containing the WB1 site (E and F) or between WTZF(−KTS) protein and an oligonucleotide containing the WB2 site (G and H). Protein-DNA complexes were resolved on nondenaturing 4% polyacrylamide (acrylamide/bisacrylamide ratio, 37/1) gels electrophoresed at 4°C in 0.5× TBE. To detect the complexes, the gel was dried and exposed to X-Omat film (Kodak) at −70°C for 12 h. The positions of migration of free probe and protein-DNA complexes are indicated.

Competition experiments were performed to demonstrate the specificities of the complexes formed between WTZF(−KTS) and WB1 and WB2. The oligonucleotide WTE (5′ GAGTGCGTGGGAGTAGAA 3′ [the WT1 binding site is underlined]) contains a 10-bp optimized WT1 binding site, originally identified by using a whole-genome PCR selection assay and full-length WT1 protein (34). WT1 has 20-fold higher affinity for this site than for the consensus EGR-1 site (5′ GCGGGGGCG 3′) (34). Oligonucleotide duplexes containing the WTE site or a mutant of it, WTE(m) (5′ GAGTGCGTGAGAGTAGAA 3′ [the substitution is in boldface]) were used as competitors in gel shifts involving WTZF(−KTS) recombinant protein and radiolabeled oligonucleotides containing WB1 or WB2 sites (Fig. 2E to H). The ability of WTE, but not WTE(m), to compete the WTZF(−KTS)-WB1 and WTZF(−KTS)-WB2 complexes indicates that the interaction of WT1 with these sites is specific (Fig. 2E to H).

Transcriptional activation of the Dax-1 promoter by WT1.

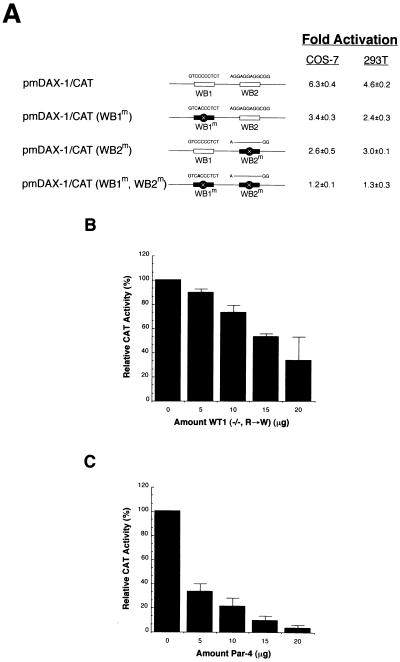

To investigate whether the WT1 binding sites within the murine and human Dax-1 promoters could mediate a transcriptional response to WT1, both promoter regions were cloned upstream of the CAT reporter gene (Fig. 3A). CMV-based expression vectors driving the production of all four alternatively spliced WT1 isoforms and two isoforms of the commonest Denys-Drash syndrome (DDS) allele (harboring a missense mutation in zinc finger III, converting 394Arg to 394Trp) were also generated. Reporter and expression vectors were then introduced into COS-7 cells and assayed for induction of CAT activity. No detectable amount of CAT activity was present in extracts prepared from untransfected COS-7 cells (Fig. 3B, “Mock” lane). Cotransfection of pmDAX-1/CAT or phDAX-1/CAT with the empty expression vector pcDNA3, resulted in a low-level production of CAT enzyme (Fig. 3B, “vector alone” lane). This basal level of CAT activity was arbitrarity set as 1. Cotransfection of 5 or 10 μg of CMV/WT1(−/−) expression vector produced a dose-dependent increase in CAT activity from both human and murine Dax-1 promoters (three- to sevenfold [Fig. 3B]). Similar results were obtained in human embryonic kidney 293T and simian CV-1 cells, indicating that the observed response is not cell line dependent (23) (Fig. 4A). The observed transcriptional response was dependent on the unique DNA binding specificities of the WT1(−KTS) isoforms, since only those isoforms could elicit a response from the DAX-1/CAT reporter (Fig. 3C). In this experiment, isoforms containing the +KTS amino acids between zinc fingers III and IV [WT1(+/+) and WT1(−/+)], or representing the commonest DDS allele [WT1(+/+, R→W) and WT1(−/−, R→W)] could not activate CAT expression above basal levels (Fig. 3C). Activation by WT1(−/−) and WT1(+/−) was dependent on the presence of the Dax-1 promoter, since no response was observed from the parental pCAT reporter vector lacking the Dax-1 promoter (23). These results demonstrate that activation of Dax-1 gene expression by WT1 is restricted to the −KTS isoforms. Since the majority of WT1 downstream targets identified to date are repressed by the wt1 tumor suppressor gene product, these results identify the Dax-1 promoter as one of the few promoters known to be activated by WT1 (42).

FIG. 3.

Transactivation of the human and murine Dax-1 promoters by WT1(−KTS) isoforms. (A) Schematic representation of reporter plasmids and expression vectors. The pmDax-1/CAT and phDAX-1/CAT reporter plasmids contain genomic DNA sequences from nucleotides −218 to +3 (for mouse) and −234 to +3 (for human), respectively (Fig. 1B). The murine promoter is indicated by solid boxes, the human Dax-1 gene promoter is indicated by shaded boxes, and the CAT gene is indicated by open boxes. Expression vectors driving the production of murine WT1 isoforms are also represented. The first alternative splice site (exon V) consists of 17 amino acids (VAAGSSSSVKWTEGDSN), and the second alternative splice site consists of three amino acids (KTS). The exon boundaries of wt1 are denoted above WT1(+/+), and the positions of the first and last amino acids are indicated below each construct. (B) Transcriptional activation of the murine and human Dax-1 promoters by WT1(−/−). Cotransfections of COS-7 cells were performed with 1 μg of reporter plasmid and 0, 5, or 10 μg of CMV/WT1(−/−) expression plasmid. Individual DNA precipitates were adjusted to contain equal amounts of total DNA by the addition of the empty expression vector, pcDNA3. To normalize for transfection efficiency, the cells were cotransfected with 2 μg of pRSV/β-gal. At 48 h after transfection, the cells were harvested and assayed for β-galactosidase and CAT activity. The average fold activation and standard error for CAT determinations are indicated below the chromatogram and represent the value obtained from three independent experiments. (C) Effect of WT1 isoforms on the transcriptional regulation of the murine Dax-1 promoter. The average relative transactivation (normalized CAT activity) and standard error is presented, with the relative transactivation values obtained with pcDNA3 and CMV/WT1(−/−) taken as 0 and 100%, respectively. The values shown are taken from three independent experiments. A representative autoradiogram is shown on the right. R→W indicates a missense mutation in WT1 zinc finger III converting an Arg residue to a Trp. This is the commonest DDS allele.

To demonstrate that the observed transactivation of the Dax-1 promoter by WT1(−KTS) is mediated through the GC-rich WT1 recognition elements defined above by EMSAs and footprinting, a mutational analysis of these sites was conducted. Reporter constructs were generated in which either (i) each site was individually mutated or (ii) both sites were altered (Fig. 4A). These reporter constructs were cotransfected with CMV/WT1(−/−) into COS-7 and 293T cells, and CAT assays performed. Mutation of either WT1 binding site, WB1 or WB2, produced reporter plasmids showing an ∼50% decreased transcriptional response to WT1(−/−) (Fig. 4A). Cotransfection of WT1(−/−) and pmDAX-1/CAT(WB1m,WB2m) failed to produce any significant CAT activity (Fig. 4A). These results indicate that both WT1 binding sites defined in this study within the Dax-1 promoter are essential for mediating optimal transactivation by WT1.

Several studies have documented that the transcriptional properties of WT1 can be influenced by a number of proteins. Among these are products of DDS alleles of wt1, which behave as dominant negatives by interacting with wild-type WT1 via an NH2-terminal domain, thus sequestering functional WT1 protein in inactive complexes (8, 30, 43). In addition, previous studies have shown that the prostate apoptosis response-4 (par-4) gene product binds to WT1 through the zinc finger region and inhibits WT1-mediated transcriptional activation (20). We examined whether either of these two proteins could modulate transactivation of the Dax-1 promoter by WT1. Introduction of increasing amounts of CMV/WT1(−/−, R→W) to a transfection containing fixed amounts of pmDAX-1/CAT and CMV/WT1(−/−) led to a progressive reduction in CAT activity (Fig. 4B). Since WT1(−/−, R→W) cannot bind to WT1 recognition elements and does not by itself affect Dax-1 expression (Fig. 3C), the observed interference on transcriptional activation is likely mediated through sequestration of wild-type WT1(−/−), as previously demonstrated (8).

A similar approach was used to determine if Par-4 could decrease WT1-mediated activation of the Dax-1 promoter. Cotransfection of increasing amounts of a CMV-Par-4 expression vector with pmDAX-1/CAT and CMV-WT1(−/−) leads to a reproducible decrease in the activation of the Dax-1 promoter (Fig. 4C). Par-4 did not affect the basal activity of the pmDAX-1/CAT reporter when transfected in the absence of CMV-WT1(−/−) (23). These results suggest that under certain conditions, Par-4 and DDS alleles of wt1 may act as possible antagonists of WT1 function during urogenital system development.

Activation of the endogenous Dax-1 promoter by WT1.

To investigate whether ectopic expression of WT1 could modulate expression of the endogenous Dax-1 gene, a tetracycline-repressible 293 cell line was generated in which the murine WT1(+/−) cDNA had been placed under control of the reverse tetracycline transactivator (16). In this system, the tetracycline analogue, doxycycline, is used to keep expression of WT1 off. Removal of doxycycline from the growth medium of this cell line results in the production of WT1(+/−) protein, as determined by Western blotting of total cell extracts (Fig. 5A and D, upper panel). Although 293 cells have been reported to express WT1 protein (40), our Western blot conditions did not detect the very low amounts of endogenous WT1 protein (Fig. 5A, compare lanes 1 to 4 and 5 to 8). To examine the effects of activating WT1 expression on endogenous Dax-1 gene expression, S1 nuclease analyses were performed with complementary synthetic oligonucleotides targeting the Dax-1 mRNA. To distinguish between undigested probe and protected probe, a 50-mer oligonucleotide containing 10 noncomplementary nucleotides (adenosine residues at the 3′ end were synthesized). Protection with this probe was observed only when it was hybridized to total RNA isolated from 293-WT1(+/−) cells but not with total RNA from 293 cells or with control tRNA (Fig. 5B). Sense and antisense probes against GAPDH were used as controls in these experiments. To verify that both 293 and 293-WT(+/−) RNA preparations contained equivalent amounts of RNA, both samples were probed for the presence of GAPDH (Fig. 5C). The observed GAPDH signal was not due to DNA contamination of the RNA preparation, since no signal was obtained with a sense GAPDH oligonucleotide (Fig. 5C).

To confirm these results and exclude the possibility that Dax-1 expression is regulated by WT1 through a mechanism of attenuation whereby a signal within the Dax-1 gene would result in premature termination of transcription, thereby producing a nonfunctional transcript, we assessed the quality of RNA isolated from 293 and 293-WT1(+/−) cells grown in the presence or absence of doxycycline (Fig. 5D). Western blotting demonstrated that expression of WT1(+/−) was activated only in 293-WT1(+/−) cells grown in the absence of doxycycline and not in 293-WT1(+/−) cells grown in the presence of doxycycline or in 293 cells grown under both conditions (Fig. 5D, upper panel). Northern blot analysis of total RNA isolated from these cells revealed that full-length Dax-1 transcripts were detectable only in 293-WT1(+/−) cells grown in the absence of doxycycline, conditions resulting in activation of WT1(+/−) protein (Fig. 5D, middle panel). Equivalent amounts of RNA were present in each lane, as judged by ethidium bromide staining of the agarose gel before transfer of the nucleic acid to Hybond N+ (Fig. 5D, lower panel). These results demonstrate that WT1 is capable of activating the Dax-1 promoter in vivo.

DISCUSSION

Dax-1 is an immediate downstream target of WT1.

Our results imply a direct regulatory link between the wt1 tumor suppressor gene product and Dax-1, an unusual member of the nuclear hormone receptor superfamily (Fig. 6). There are three criteria which WT1 fulfills as an upstream regulator of Dax-1. (i) WT1 expression precedes that of DAX-1 in the urogenital ridge. In fact, very high levels of wt1 transcripts are present in the urogenital ridge of 9-dpc mouse embryos, a time when there is no detectable Dax-1 expression (1). Dax-1 transcripts are first detected in the developing indifferent murine gonads of both XX and XY embryos at 10 to 10.5 dpc; transcript levels peak at 11.5 to 12 dpc and remain fairly constant in females throughout the remainder of development, whereas in males the levels rapidly decline (48). (ii) Both DAX-1 and WT1 proteins show an overlapping spatial expression profile in the developing fetal gonad (Fig. 1A). (iii) WT1(−KTS) isoforms are capable of directly transactivating Dax-1 gene expression (Fig. 3 and 5). We propose that the initial rise in Dax-1 expression in the developing male and female gonad is mediated by WT1 (Fig. 6). It is not yet clear what subsequent events uncouple expression of these genes in the male gonad. One possible effector of Dax-1 expression may be par-4, a regulator of WT1 transcriptional activity, since we have shown that Par-4 can interfere with WT1-mediated transactivation of Dax-1 in vitro (Fig. 4C). Additionally, once testicular differentiation has commenced, sequestration of Dax-1 expression to Leydig cells and wt1 expression to Sertoli cells would also clearly abrogate the WT1–DAX-1 axis in males. Alternatively, other cell-specific repressors or coactivators may contribute to this effect.

FIG. 6.

(A) Schematic representation illustrating the relative expression of gene products involved in sexual differentiation of the gonad. (B) Model depicting our results and the predicted effects on gene expression in the developing male gonad. The separate nuclear localization of WT1 isoforms is highlighted. The male-specific gene Sry is antagonized by the Dax-1 gene product (47), whereas MIS is activated via a synergistic effect of SF-1–WT1(−KTS) complexes, causing regression of the female anlagen (33). As a result of WT1-mediated activation, levels of DAX-1 are increased during normal early gonadal development. Once DAX-1 has accumulated to a certain threshold level, Sry activity is antagonized.

There is a potentially interesting link between the regulation of Dax-1 by WT1 and activation of the cyclic AMP cAMP pathway. Dax-1 expression in Sertoli cells is down-regulated by the pituitary hormone FSH through the cAMP signaling pathway (49). Interestingly, previous studies have shown that the DNA binding activity of WT1 can be modified by phosphorylation in vivo (44, 53). Treatment of WT1-expressing cells with forskolin, an activator of the cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA) in vivo, induces phosphorylation of WT1 at two serine residues in the WT1 zinc fingers, abrogating DNA binding. We therefore speculate that the down-regulation of Dax-1 gene expression observed in Sertoli cells following exposure to FSH could be due to phosphorylation of WT1 via the cAMP-dependent pathway, resulting in loss of WT1 DNA binding and transcriptional activation effects.

wt1 mutations and gonadal differentiation.

Genetic evidence has indicated that although DAX-1 is not required for normal testis differentiation (32, 54), XY individuals with duplications of Dax-1 show male-to-female sex reversal, implying a link between DAX-1 and the gonadal differentiation pathway (3). Consistent with this interpretation, DAX-1 has been shown to antagonize Sry function in some transgenic mice containing a weakened Sry allelic background made to overexpress DAX-1 (47). In this experimental setting, altering the window of Dax-1 expression has severe consequences—if DAX-1 levels peak too early, then Sry activity is inhibited before the male differentiation program has been activated, providing a rationale for the sex reversal associated with increased dosage of Dax-1 in individuals with duplications of Xp21. The outcome of delayed Dax-1 expression is more difficult to predict, but should not impair the testis differentiation process, since this program is activated by Sry.

Our model implying that WT1 directly up-regulates Dax-1 expression has several implications. Genetic analysis of individuals with germ line wt1 mutations has demonstrated a role for this transcription factor in both sexual and gonadal differentiation (36, 37). Heterozygous germ line deletion of wt1 is associated with predisposition to Wilms’ tumor and mild developmental defects of the male reproductive system (37). Severe intersex disorders (including XY pseudohermaphroditism) and renal defects, in contrast, are frequently associated with germ line heterozygous point mutations in the zinc finger region of wt1 in DDS (7, 36). The DDS phenotypes are thought to be the result of dominant-negative inhibition of wild-type WT1 activity by the product of the mutant allele. The molecular basis of this phenomenon may involve the ability of WT1 to self-associate via an amino-terminal domain (8, 30, 36). Products of the mutant allele may sequester WT1 protein in inactive complexes and inhibit wt1-mediated transregulation of critical genes necessary for sexual development.

The MIS gene is a good candidate for such a gene. Nachtigal et al. (33) have shown that the WT1(−KTS) isoforms can associate and synergize with SF-1 to promote MIS gene expression. DAX-1 can antagonize this synergy, likely through a direct association with SF-1 (Fig. 6). It appears that the combination of WT1 and SF-1 in the male gonad leads to regression of the Müllerian ducts, whereas in the female gonad absence of SF-1 ensures that no MIS is produced. Reduced levels of MIS, due to inhibited WT1 function in patients with DDS, may account for incomplete regression of Müllerian ducts and the resulting pseudohermaphroditism in these patients.

It is not immediately apparent how activation of Dax-1 expression by WT1 can be integrated into models to account for defects in male sexual development in DDS and WAGR syndrome. These patients would be expected to have decreased Dax-1 expression in the gonad. This in itself should not interfere with male sexual development, since Dax-1 is dispensable in this process. WT1 mutations, however, may alternatively result in delayed Dax-1 expression, and this late Dax-1 expression could disturb development of the testis.

Recently, mutations which specifically cause a defect in alternative splicing at exon 9 of wt1 have been associated with Frasier syndrome (FS), a disorder characterized by focal glomerular sclerosis, delayed kidney failure, and gonadal dysgenesis (2, 22, 24). Individuals with this syndrome show mutations within wt1 intron 9 which specifically disrupt alternative splicing and prevent synthesis of the usually more abundant +KTS isoform from the mutant allele. An altered ratio of the WT1 isoforms is detected in these patients, indicating that renal and gonadal development are particularly sensitive to the appropriate WT1 isoform ratio (6, 24). How might this altered isoform ratio account for the FS phenotype? In our assays, only the WT1(−KTS) isoform is able to transactivate Dax-1 expression. The decrease in the WT1(+KTS) isoform in patients with FS may result in a larger amount of transcriptionally active WT1(−KTS) (since these isoforms can interact), causing abnormally high levels of DAX-1 to be expressed. Inhibition of Sry activity in response to elevated Dax-1 expression may then contribute to the intersex disorders in these patients. The implication of Dax-1 overexpression in FS gonadal abnormalities is conceptually more compelling than a role for deregulation of MIS expression, since the elevated levels of active WT1(−KTS) would be expected to increase MIS expression. Such an increase in MIS could not account for the abnormal development of male structures.

An alternative explanation for the FS phenotype is that WT1(+KTS) isoforms may play an important role in posttranscriptional regulation of genes involved in gonadal differentiation. Larsson et al. (27) have demonstrated that different WT1 isoforms localize to distinct nuclear compartments: −KTS isoforms show a distribution parallel to that of classical transcription factors, whereas +KTS isoforms are preferentially associated with interchromatin granules and coiled bodies. These latter structures may be regions of posttranscriptional processing of mRNA.

Activation of transcription by WT1.

The mechanism by which WT1 activates or represses genes is still a poorly understood process, although a large number of genes have been shown to be WT1-responsive. In the majority of cases analyzed, WT1 behaves as a repressor of transcription. The repressor domain maps to amino acids 84 to 179 (29, 52). In the case of the syndecan-1 and p21 genes, WT1 has been shown to activate transcription, although the two genes appear to require distinct activation domains (12, 14). The Dax-1 promoter is the only one characterized to date which contains two WT1-responsive sites, both of which can individually mediate transactivation by WT1 (Fig. 4A). In our hands, internal deletions of WT1 which either (i) remove the transactivation domain (a deletion of amino acids 160 to 262) or (ii) abolish the self-association domain (a deletion of amino acids 2 to 126) could no longer activate Dax-1 gene expression in transient transfection assays, suggesting that both of these domains are essential for the observed transcriptional effects (23).

The ability of SF-1 to bind to the Dax-1 promoter in vitro (9) suggests that it may interact with WT1(−KTS) to synergistically activate Dax-1 expression, as is observed for the MIS gene. Like wt2, SF-1 expression appears very early in the urogenital ridge of both sexes (9 dpc) and thus precedes Dax-1 expression (17). In transient transfection assays, we have observed that SF-1 activates the Dax-1 promoter; however, the effect was additive, not synergistic, when both SF-1 and WT1(−KTS) were cotransfected with pmDAX-1/CAT into COS-7 cells (23). Although we have not further characterized this response, we note that both factors may be necessary to obtain the full extent of Dax-1 activation early in gonadal development.

Our results help to define an early cascade of gonadal differentiation. Genetic analysis of these pathways in vivo will be required to define their exact roles in the differentiation process (i.e., redundancy, modifier loci, or allelic variation) and any steps involved in their regulation. Further transcriptional analysis of the wt1 gene and elucidation of the mechanism(s) regulating the expression of wt1 in male and female gonads should aid in identifying additional genes involved in male and female sex determination.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank J. Larry Jameson (Northwestern University) for his kind gift of pBKCMV human DAX-1.

J.K. was supported by a fellowship from a McGill Faculty of Medicine Scholarship. N.B. was supported by an MRC studentship. J.P. is a Medical Research Council of Canada Scientist. This work was supported by a grant from the National Cancer Institute of Canada to J.P.

REFERENCES

- 1.Armstrong J F, Pritchard-Jones K, Bickmore W A, Hastie N D, Bard J B L. The expression of the Wilms’ tumour gene, WT1, in the developing mammalian embryo. Mech Dev. 1992;40:85–97. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(93)90090-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barbaux S, Niaudet P, Gubler M C, Grunfeld J P, Jaubert F, Kuttenn F, Fekete C N, Souleyreau-Therville N, Thibaud E, Fellous M, McElreavey K. Donor splice-site mutations in WT1 are responsible for Fraiser syndrome. Nat Genet. 1997;17:467–470. doi: 10.1038/ng1297-467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bardoni B, Zanaria E, Guioli S, Floridia G, Worley K, Tonini G, Ferrante E, Chiumello G, McCabe E, Fraccaro M, Zuffardi O, Camerino G. A dosage sensitive locus at chromosome Xp21 is involved in male to female sex reversal. Nat Genet. 1994;7:497–501. doi: 10.1038/ng0894-497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Behringer R R, Finegold M J, Cate R L. Müllerian-inhibiting substance function during mammalian sexual development. Cell. 1994;79:415–425. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90251-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berta P, Hawkins J R, Sinclair A H, Taylor A, Griffiths B L, Goodfellow P N, Fellous M. Genetic evidence equating SRY and the testis-determining factor. Nature. 1990;348:448–450. doi: 10.1038/348448A0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bruening W, Bardeesy N, Silverman B L, Cohn R A, Machin G A, Aronson A J, Housman D, Pelletier J. Germline intronic and exonic mutations in the Wilms’ tumour gene (WT1) affecting urogenital development. Nat Genet. 1992;1:144–148. doi: 10.1038/ng0592-144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bruening W, Pelletier J. Denys-Drash syndrome: a role for the WT1 tumor suppressor gene in urogenital development. Semin Dev Biol. 1994;5:333–343. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bruening W, Moffett P, Chia S, Heinrich G, Pelletier J. Identification of nuclear localization signals within the zinc fingers of the WT1 tumor suppressor gene product. FEBS Lett. 1996;393:41–47. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00853-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burris T P, Guo W, Le T, McCabe E R B. Identification of a putative steroidogenic factor-1 response element in the DAX-1 promoter. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995;214:576–581. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.2324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cate R L, Mattaliano R J, Hession C, Tizard R, Farber N M, Cheung A, Ninfa E G, Frey A Z, Gash D J, Chow E P, Fisher R A, Bertonis J M, Torres G, Wallner B P, Ramachandran K L, Ragin R C, Manganaro T F, MacLaughlin D T, Donahoe P K. Isolation of the bovine and human genes for Müllerian inhibiting substance and expression of the human gene in animal cells. Cell. 1986;45:685–698. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90783-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clarkson T, Gussow D, Jones P T. General application of PCR to gene cloning and manipulation. In: McPherson M J, Quirke P, Taylor G R, editors. PCR—a practical approach. New York, N.Y: IRL Press; 1992. pp. 187–214. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cook D M, Hinkes M T, Bernfied M, Rauscher F J., III Transcriptional activation of the syndecan-1 promoter by the Wilms’ tumor protein WT1. Oncogene. 1996;13:1789–1799. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crawford P A, Dorn C, Sadovsky Y, Milbrandt J. Nuclear receptor DAX-1 recruits nuclear receptor corepressor N-CoR to steroidogenic factor 1. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:2949–2956. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.5.2949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Englert C, Maheswaran S, Garvin A J, Kreidberg J, Haber D A. Induction of p21 by the Wilms’ tumor suppressor gene wt1. Cancer Res. 1997;57:1429–1434. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Foster J W, Dominguez S M, Guioli S, Kowk G, Weller P A, Stevanovic M, Weissenbach J, Mansour S, Young I D, Goodfellow P N, Brook J D, Schafer A J. Campomelic dysplasia and autosomal sex reversal caused by mutations in an SRY-related gene. Nature. 1994;372:525–530. doi: 10.1038/372525a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gossen M, Bujard H. Tight control of gene expression in mammalian cells by tetracycline-responsive promoters. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:5547–5551. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.12.5547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ikeda Y, Shen W-H, Ingraham H, Parker K. Developmental expression of mouse steroidogenic factor-1, an essential regulator of the steroid hydroxylases. Mol Endocrinol. 1994;8:654–662. doi: 10.1210/mend.8.5.8058073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ito M, Yu R, Jameson J L. DAX-1 inhibits SF-1-mediated transactivation via a carboxy-terminal domain that is deleted in adrenal hypoplasia congenita. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:1476–1483. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.3.1476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jäger R J, Anvret M, Hall K, Scherer G. A human XY female with a frame shift mutation in the candidate testis-determining gene SRY. Nature. 1990;348:452–454. doi: 10.1038/348452a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnstone R W, See R H, Sells S F, Wang J, Muthukkumar S, Englert C, Haber D A, Licht J D, Sugrue S P, Roberts T, Rangnekar V M, Shi Y. A novel repressor, par-4, modulates transcription and growth suppression functions of the mouse Wilms’ tumor suppressor WT1. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:6945–6956. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.12.6945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Katoh-Fukui Y, Tsuchiya R, Shiroishi T, Nakahara Y, Hashimoto N, Noguchi K, Higashinakagawa T. Male-to-female sex reversal in M33 mutant mice. Nature. 1998;393:688–692. doi: 10.1038/31482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kikuchi H, Takata A, Akasaka Y, Fukuzawa R, Yoneyama H, Kurosawa Y, Honda M, Kamiyama Y, Hata J. Do intronic mutations affecting splicing of WT1 exon 9 cause Frasier syndrome? J Med Genet. 1997;35:45–48. doi: 10.1136/jmg.35.1.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim, J., and J. Pelletier. Unpublished data.

- 24.Klamt B, Koziell A, Poulat F, Wieacker P, Scambler P, Berta P, Gessler M. Frasier syndrome is caused by defective alternative splicing of WT1 leading to an altered ratio of WT1 +/− KTS splice isoforms. Hum Mol Genet. 1998;7:709–714. doi: 10.1093/hmg/7.4.709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koopman P, Gubbay J, Vivian N, Goodfellow P, Lovell-Badge R. Male development of chromosomally female mice transgenic for Sry. Nature. 1991;351:117–121. doi: 10.1038/351117a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kreidberg J A, Sariola H, Loring J M, Maeda M, Pelletier J, Housman D, Jaenich R. WT-1 is required for early kidney development. Cell. 1993;74:676–691. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90515-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Larsson S H, Charlieu J-P, Miyagawa K, Engelkamp D, Rassoulzadegan M, Ross A, Cuzin F, van Heyningen V, Hastie N D. Subnuclear localization of WT1 in splicing or transcription factor domains is regulated by alternative splicing. Cell. 1995;81:391–401. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90392-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Luo X, Ikeda Y, Parker K L. A cell-specific nuclear receptor is essential for adrenal and gonadal development and sexual differentiation. Cell. 1994;77:481–490. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90211-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Madden S L, Cook D M, Rauscher F J., III A structure-function analysis of transcriptional repression mediated by the WT1, Wilms’ tumor suppressor protein. Oncogene. 1993;8:1713–1720. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moffett P, Bruening W, Nakagama H, Bardeesy N, Housman D, Housman D, Pelletier J. Antagonism of WT1 activity by protein self-association. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:11105–11109. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.24.11105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mundlos S, Pelletier J, Darveau A, Bachmann M, Winterpacht A, Zabel B. Nuclear localization of the protein encoded by the Wilms’ tumor gene WT1 in embryonic and adult tissues. Development. 1993;119:1329–1341. doi: 10.1242/dev.119.4.1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Muscatelli F, Strom T M, Walker A P, Zanaria E, Recan D, Meindl A, Bardoni B, Guioli S, Zehetner G, Rabl W, Achwart H P, Kaplan J-C, Camerino G, Meitinger T, Monaco A P. Mutations in the DAX-1 gene give rise to both X-linked adrenal hypoplasia congenita and hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. Nature. 1994;372:672–676. doi: 10.1038/372672a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nachtigal M W, Hirokawa Y, Enyeart-VanHouten D L, Flanagan J N, Hammer G D, Ingraham H A. Wilms’ tumor 1 and Dax-1 modulate the orphan nuclear receptor SF-1 in sex-specific gene expression. Cell. 1998;93:445–454. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81172-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nakagama H, Heinrich G, Pelletier J, Housman D. Sequence and structural requirements for high-affinity DNA binding by the WT1 gene product. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:1489–1498. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.3.1489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Parker K L, Schimmer B P. Steroidogenic factor 1: a key determinant of endocrine development and function. Endocr Rev. 1997;18:361–377. doi: 10.1210/edrv.18.3.0301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pelletier J, Bruening W, Kashtan C E, Mauer S M, Manivel J C, Striegel J, Houghton D C, Junien C, Habib R, Fouser L, Fine R N, Silverman B L, Haber D, Housman D. Germline mutations in the Wilms’ tumor suppressor gene are associated with abnormal urogenital development in Denys-Drash syndrome. Cell. 1991;67:437–447. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90194-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pelletier J, Bruening W, Li F P, Haber D A, Glaser T, Housman D. WT1 mutations contribute to abnormal genital system development and hereditary Wilms’ tumour. Nature. 1991;353:431–434. doi: 10.1038/353431a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pelletier J, Schalling M, Buckler A J, Rogers A, Haber D A, Housman D. Expression of the Wilms’ tumor gene WT1 in the murine urogenital system. Genes Dev. 1991;5:1345–1356. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.8.1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pritchard-Jones K, Fleming S, Davidson D, Bickmore W, Porteous D, Gosden C, Bard J, Buckler A, Pelletier J, Housman D E, van Heyningen V, Hastie N. The candidate Wilms’ tumor gene is involved in genitourinary development. Nature. 1990;346:194–197. doi: 10.1038/346194a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rackley R R, Flenniken A M, Kuriyan N P, Kessler P M, Stoler M H, Williams B R G. Expression of the Wilms’ tumor suppressor gene wt1 during mouse embryogenesis. Cell Growth Diff. 1993;4:1023–1031. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rauscher F J, III, Morris J F, Tournay O E, Cook D M, Curran T. Binding of the Wilms’ tumor locus zinc finger protein to the EGR-1 consensus sequence. Science. 1990;250:1259–1262. doi: 10.1126/science.2244209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reddy J C, Licht J D. The WT1 Wilms’ tumor suppressor gene: how much do we really know? Biochem Biophys Acta. 1996;1287:1–28. doi: 10.1016/0304-419x(95)00014-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reddy J C, Morris J C, Wang J, English M A, Haber D A, Shi Y, Licht J D. WT1-mediated transcriptional activation is inhibited by dominant negative mutant proteins. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:10878–10884. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.18.10878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sakamoto Y, Yoshida M, Semba K, Hunter T. Inhibition of the DNA-binding and transcriptional repression activity of the Wilms’ tumor gene product, WT1, by cAMP-dependent protein kinase-mediated phosphorylation of Ser-365 and Ser-393 in the zinc finger domain. Oncogene. 1997;15:2001–2012. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shen W-H, Moore C C D, Ikeda Y, Parker K L, Ingraham H A. Nuclear receptor steroidogenic factor 1 regulates the Müllerian inhibiting substance gene: a link to the sex determination cascade. Cell. 1994;77:1–20. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90050-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Swain A, Narvaez V, Burgoyne P, Camerino G, Lovell-Badge R. Dax1 antagonizes Sry action in mammalian sex determination. Nature. 1998;391:761–767. doi: 10.1038/35799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Swain A, Zanaria E, Hacker A, Lovell-Badge R, Camerino G. Mouse Dax-1 expression is consistent with a role in sex determination as well as in adrenal and hypothalamus function. Nat Genet. 1996;12:404–409. doi: 10.1038/ng0496-404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tamai K T, Monaco L, Alastalo T-P, Lalli E, Parvinen M, Sassone-Corsi P. Hormonal and developmental regulation of DAX-1 expression in Sertoli cells. Mol Endocrinol. 1996;10:1561–1569. doi: 10.1210/mend.10.12.8961266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wagner T, Wirth J, Meyer J, Zabel B, Held M, Zimmer J, Pasantes J, Bricarelli F D, Keutel J, Hustert E, Wolf U, Tommerup N, Schempp W, Scherer G. Autosomal sex reversal and campomelic dysplasia are caused by mutations in and around the SRY-related gene SOX9. Cell. 1994;79:1111–1120. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90041-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang Z-Y, Qiu Q-Q, Deuel T F. The Wilms’ tumor gene product WT1 activates or suppresses transcription through separate functional domains. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:9172–9175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang Z Y, Qiu Q-Q, Enger K T, Deuel T F. A second transcriptionally active DNA-binding site for the Wilms tumor gene product, WT1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:8896–8900. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.19.8896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ye Y, Raychaudhuri B, Gurney A, Campbell C E, Williams B R G. Regulation of WT1 by phosphorylation: inhibition of DNA binding, alteration of transcriptional activity, and cellular translocation. EMBO J. 1996;15:5606–5615. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zanaria E, Muscatelli F, Bardoni B, Strom T M, Guioli S, Guo W, Lalli E, Moser C, Walker A P, McCabe E R, Meitinger T, Monaco A P, Sassone-Corsi P, Camerino G. An unusual member of the nuclear hormone receptor superfamily responsible for X-linked adrenal hypoplasia congenita. Nature. 1994;372:635–641. doi: 10.1038/372635a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zazopoulos E, Lalli E, Stocco D M, Sassone-Corsi P. DNA binding and transcriptional repression by DAX-1 blocks steroidogenesis. Nature. 1997;390:311–315. doi: 10.1038/36899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]