Abstract

Viruses are considered of major importance in strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa Duchesne) production given their negative impact on plant vigor and growth. Strawberry accessions from the National Clonal Germplasm Repository were screened for viruses using high throughput sequencing (HTS). Analyses of sequence information from 45 plants identified multiple variants of 14 known viruses, comprising strawberry mottle virus (SMoV), beet pseudo yellows virus (BPYV), strawberry pallidosis-associated virus (SPaV), tomato ringspot virus (ToRSV), strawberry mild yellow edge virus (SMYEV), strawberry vein banding virus (SVBV), strawberry crinkle virus (SCV), strawberry polerovirus 1 (SPV-1), apple mosaic virus (ApMV), strawberry chlorotic fleck virus (SCFaV), strawberry crinivirus 4 (SCrV-4), strawberry crinivirus 3 (SCrV-3), Fragaria chiloensis latent virus (FClLV) and Fragaria chiloensis cryptic virus (FCCV). Genetic diversity of sequenced virus isolates was investigated via sequence homology analysis, and partial-genome sequences were deposited into GenBank. To confirm the HTS results and expand the detection of strawberry viruses, new reverse transcription quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) assays were designed for the above-listed viruses. Further in silico and in vitro validation of the new diagnostic assays indicated high efficiency and reliability. Thus, the occurrence of different viruses, including divergent variants, among the strawberries was verified. This is the first viral metagenomic survey in strawberry, additionally, this study describes the design and validation of multiple RT-qPCR assays for strawberry viruses, which represent important detection tools for clean plant programs.

Keywords: strawberry, germplasm, virome, high throughput sequencing, virus, detection, RT-qPCR, diagnostic assay

1. Introduction

The garden or commercial strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa Duchesne) is a widely grown hybrid species of the genus Fragaria (family Rosaceae), which is cultivated as a source of food in many parts of the world [1]. This plant was first bred in Europe around 1750 and is a hybrid between F. virginiana from North America and F. chiloensis from South America [2,3]. The United States is one of the major worldwide producers of strawberry with 1.2 million tons in 2018, produced primarily in the state of California (Food and Agriculture Organization. http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QC, accessed on 26 October 2020). California strawberries are available year-round because of the mild climate, which allows harvesting fruits over a long period of time [4].

An important resource of genetic material from Fragaria is the US Department of Agriculture, ARS National Clonal Germplasm Repository (NCGR) located in Corvallis (OR, USA). The NCGR contains 2013 active strawberry accessions, representing 46 taxa including species and subspecies (GRIN-Global. https://npgsweb.ars-grin.gov/gringlobal/search, accessed on 27 October 2020). Besides having foundational material for horticultural distribution, the NCGR also separately houses pathogen-positive accessions for virology research.

Various viral diseases have been reported in strawberry and are associated with plant decline and yield loss (for a review [5,6]). The high number of identified viruses in strawberry is the result of vegetative propagation and exposure of the plant in open-field cultivation. Additionally, different vectors (e.g., insects and nematodes) have been shown to transmit these viruses. Lastly, viruses in strawberry plants may be in low concentrations and in mixed infections, and commonly induce non-specific symptoms [7].

Reliable and efficient diagnostic tests are critical in determining viral infection in strawberry and consequently the control of disease. Multiple laboratory-based tests are available for the diagnosis of viruses in strawberry, mainly involving ELISA and reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR), previously reviewed in [8]. In contrast, the use of quantitative RT-PCR (RT-qPCR) assays for strawberry viruses is extremely limited or absent. The advantages of using RT-qPCR over other classical molecular-serological methods to detect viruses are increased sensitivity, speed, reproducibility, and limited risk of contamination [9].

Recently, next generation sequencing or high throughput sequencing (HTS) has been used to reveal the etiology of several diseases in strawberry. For example, a novel virus (i.e., strawberry polerovirus-1, SPV-1) was associated with the strawberry decline disease in Canada [10]. Two new putative viruses in the genus Crinivirus, strawberry criniviruses 3 and 4 (SCrV-3 and 4), were identified in strawberry plants displaying virus-like symptoms [11,12]. In 2019, Fránová et al. [7] sequenced a novel rhabdovirus infecting garden and wild strawberry plants.

To further investigate the virome of strawberry, we analyzed 45 plants collected at the NCGR by HTS. Multiple variants of viruses known to infect strawberry were annotated and characterized, including near-complete genomes. To complement these HTS results, new RT-qPCR assays were developed and validated for 14 different viruses.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material and TNA Extraction

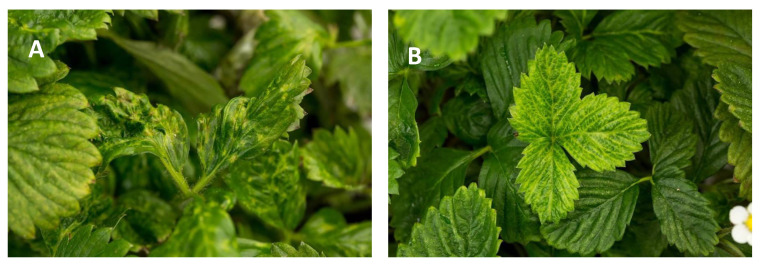

In the summer of 2020, 45 accessions of strawberry were received as propagative material from the NCGR, under a USDA Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) movement permit, for HTS analysis at Foundation Plant Services (FPS, University of California-Davis, Davis, CA, USA). These 45 plants were previously determined to be positive for viruses or virus-like agents using RT-PCR and bio-indexing. Stolons were propagated under mist and later transferred to single 1-gal pots within a greenhouse. Four months after bud break, 0.7 g of leaf tissue from each strawberry plant was collected and spiked with 5% (w/w) tissue of Phaseolus vulgaris cultivar Black Turtle Soup (BTS). BTS is naturally infected by two different endornaviruses and is used as an internal control in HTS virus screening [13]. At the time of sampling different leaf symptoms were observed in several strawberry plants (Figure 1). Following the protocol described in [14], total nucleic acid (TNA) extracts were prepared using guanidine isothiocyanate lysis buffer and a KingFisher Flex System with the MagMax™ Plant RNA Isolation kit (ThermoFisher Scientific, Sunnyvale, CA, USA).

Figure 1.

Virus-like symptoms on select strawberry plants that were sampled during the study. (A), plant infected by beet pseudo yellows virus and strawberry crinkle virus; (B), plant infected by strawberry vein banding virus.

2.2. HTS and Plant Virus Identification

For individual samples, a total of 700 ng per 10 µL of extracted nucleic acids were subjected to rRNA and cDNA library construction using TruSeq Stranded Total RNA with Ribo-Zero Plant kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). Subsequently, cDNA libraries were end-repaired, adapter-ligated by unique dual-indexes, and PCR enriched. Finally, the amplicons were sequenced in an Illumina NextSeq 500 platform using a single-end 75-bp format.

Sequenced reads were demultiplexed and adapter trimmed using Illumina bcl2fastq2 v2.20.0.422. To obtain the highest quality contig for an annotated virus, three de novo assemblies were performed: (1) a de novo assembly using SPAdes v3.14.1 [15]; (2) a de novo assembly using SPAdes v3.14.1 in RNA; and (3) an overlap layout consensus assembly of the virus annotated contigs from (1) using the Minimo assembler [16]. For each virus infection, the assembly yielding the longest contigs was chosen.

To annotate de novo assemblies, all contigs greater than 200 bp were aligned to the June 2020 version of the GenBank non-redundant database of nucleotide sequences using BLASTn with a reduced word size of 7 to identify known viruses. Additionally, to screen for potential unknown viruses, contigs greater than 200 bp were aligned to the June 2020 version of the GenBank non-redundant database of nucleotide sequences using BLASTx. Then, sequences with significant hits (E-value < 1 × 10−5) in this database to a virus known to infect land plants went through a final manual annotation check.

2.3. Plant Virus Genome Analysis

Potential open reading frames (ORFs) and proteins encoded by the HTS-detected viruses were annotated by ORFfinder and BLASTp analysis. Conserved domains present in the putative proteins were searched in the Pfam database [17] using HMMER v3.1 [18]. Once sequence analysis was completed, new virus sequences were deposited in GenBank.

2.4. RT-qPCR Assay Design

Following the protocol described in [19], new RT-qPCR assays were designed for all the viruses identified during the HTS analysis. Using a comprehensive approach that covers all the known virus genetic diversity in this study and in GenBank, detection assays based on sequence-specific DNA hydrolysis probes (TaqMan™ MGB) were generated. Determination of primer and probe sequences for a target region included the default parameters for qPCR in the Primer Express software (ThermoFisher Scientific, Sunnyvale, CA, USA).

After initial assay design was completed, in silico analysis facilitated by purpose-built scripts implementing the procedures described below was used to incorporate additional viral genetic diversity into assay design. For each of the viruses, the RT-qPCR assay was first evaluated against all virus sequences in the July 2020 version of GenBank as well as all virus isolates identified during this study. First, a BLAST database search is used to identify and obtain all sequences overlapping the current assay region. To maximize sensitivity, a tBLASTn translated alignment exploiting codon redundancy was used. Once target sequences were collected and their species identification confirmed, all existing primers and probes were aligned to all target sequences covering the assay region. This alignment was accomplished using a script that used an end-gap-free nucleotide alignment to identify the best matching probe, forward and reverse primer sequences to each variant. In each case, the variant sequences corresponding to the matching oligos were collected and analyzed for divergence. Thus, all unique candidate sequence variants were inspected for total or partial divergence to an existing primer/probe sequence. The location and quantity of nucleotide differences and the frequency of the differences were also determined, and the assays were updated with extra primers or probes as needed. A probe or primer was added when more than two nucleotide mismatches or a single mismatch near the end were detected during the sequence comparison. Lastly, in order to reduce the effective number of primers in each reaction, degenerate bases were not used in the oligos.

Once assay design was completed, their efficiency was calculated via serial dilutions of 1:1 to 1:10,000,000 and replicated in triplicate; standard curves were generated by the QuantStudio 6 Flex Real-Time PCR System software (ThermoFisher Scientific, Sunnyvale, CA, USA).

2.5. HTS Validation by RT-qPCR

Leaf tissue was collected from all the propagated strawberry plants and TNA was extracted as described above but reducing the input material to 0.2 g and omitting the addition of BTS. RT-qPCR reactions were completed in the QuantStudio 6 Flex Real-Time PCR System using the TaqMan Fast Virus 1-Step Master Mix (ThermoFisher Scientific, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) as per manufacturer’s protocol. Each reaction (10 µL final volume) included 2 µL of TNA and final primer and probe concentrations of 900 and 250 ῃM, respectively. In addition, the new assays were multiplexed with an 18S rRNA assay to confirm the presence of RNA [20].

2.6. Additional Testing by RT-qPCR

The new RT-qPCR assays were used to test 12 virus-positive strawberry plants located at FPS. Given the nature of FPS as a center for distribution of virus-tested propagation material, occasionally plants infected by viruses are identified and adopted as positive controls in routine screening (https://fps.ucdavis.edu/index.cfm, accessed on 1 July 2021). All 12 plants were previously analyzed by RT-PCR and HTS, revealing the presence of several viruses included in this study.

3. Results

3.1. Viral Sequences Identified by HTS

Forty-five strawberry plants originating from the NCGR were screened for viruses via HTS. HTS yielded consistent results for the sequencing, assembly, and annotation of each of the samples (Table S1). Across multiple runs, the Illumina sequenced read depth for each ranged from 23.4 to 32.2 million 75-bp reads with a median value of 28.0 million and a coefficient of variation of 0.09. More variation was observed in the subsequent Spades de novo assemblies of the metagenomes, which ranged from 9.0 Mbp to 30.0 Mbp contigs with a median value of 20.5 Mbp and a coefficient of variation of 0.27. The number of contigs that annotated as viral was a small fraction (0.01–0.25%) of each assembly.

Ignoring the multiple endornavirus-like contigs generated in all the HTS-analyzed samples, no plant infecting viruses were identified in five plants but viruses in single and mixed infections were identified in the remaining 40 plants (Table 1). These viruses included: strawberry mottle virus (SMoV), beet pseudo yellows virus (BPYV), strawberry pallidosis-associated virus (SPaV), tomato ringspot virus (ToRSV), strawberry mild yellow edge virus (SMYEV), strawberry vein banding virus (SVBV), strawberry crinkle virus (SCV), apple mosaic virus (ApMV), strawberry chlorotic fleck virus (SCFaV), Fragaria chiloensis latent virus (FClLV), Fragaria chiloensis cryptic virus (FCCV), SCrV-3, SCrV-4, and SPV-1.

Table 1.

Viruses identified in strawberry plants via high throughput sequencing (HTS). Plants originated from the National Clonal Germplasm Repository (NCGR) located in Corvallis, Oregon.

| Sample ID a | SMoV | BPYV | SPaV | ToRSV | SMYEV | SVBV | SCV | SCFaV | SCrV-4 | SPV-1 | ApMV | SCrV-3 | FClLV | FCCV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H2389 | + | |||||||||||||

| H2390 | ||||||||||||||

| H2391 | + | + | + | |||||||||||

| H2392 | + | + | ||||||||||||

| H2393 | + | |||||||||||||

| H2394 | + | + | ||||||||||||

| H2395 | + | + | ||||||||||||

| H2396 | + | + | ||||||||||||

| H2397 | ||||||||||||||

| H2398 | + | |||||||||||||

| H2399 | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||||

| H2400 | + | + | ||||||||||||

| H2401 | + | + | ||||||||||||

| H2402 | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||

| H2403 | + | + | + | |||||||||||

| H2404 | + | + | + | |||||||||||

| H2405 | + | + | ||||||||||||

| H2406 | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||

| H2407 | + | + | ||||||||||||

| H2408 | + | + | ||||||||||||

| H2409 | + | + | ||||||||||||

| H2411 | ||||||||||||||

| H2412 | ||||||||||||||

| H2413 | + | + | ||||||||||||

| H2414 | + | |||||||||||||

| H2415 | + | + | ||||||||||||

| H2416 | + | + | ||||||||||||

| H2417 | + | + | ||||||||||||

| H2418 | + | + | ||||||||||||

| H2419 | + | + | ||||||||||||

| H2421 | + | + | ||||||||||||

| H2422 | + | |||||||||||||

| H2423 | + | |||||||||||||

| H2427 | + | + | ||||||||||||

| H2424 | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||

| H2425 | + | + | + | |||||||||||

| H2426 | + | + | ||||||||||||

| H2428 | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||

| H2430 | ||||||||||||||

| H2429 | + | + | ||||||||||||

| H2431 | + | |||||||||||||

| H2432 | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||

| H2433 | + | |||||||||||||

| H2434 | + | + | ||||||||||||

| H2435 | + | + | + | + |

Strawberry mottle virus (SMoV), beet pseudo yellows virus (BPYV), strawberry pallidosis-associated virus (SPaV), tomato ringspot virus (ToRSV), strawberry mild yellow edge virus (SMYEV), strawberry vein banding virus (SVBV), strawberry crinkle virus (SCV), strawberry polerovirus 1 (SPV-1), apple mosaic virus (ApMV), strawberry chlorotic fleck virus (SCFaV), strawberry crinivirus 4 (SCrV-4), strawberry crinivirus 3 (SCrV-3), Fragaria chiloensis latent virus (FClLV) and Fragaria chiloensis cryptic virus (FCCV); a, sample IDs assigned to different strawberry plants analyzed by HTS.

A separate annotation was performed to identify potential novel plant viruses in these samples, characterized by divergent protein homology to a virus known to infect plants. No such sequences were observed. However, distant protein homology to insect viruses, mycoviruses and phages was observed.

3.2. New Viral Genetic Diversity

The BLASTn annotation of the assembled contigs revealed a genetically diverse set of sequences from plant viruses known to infect strawberry. We identified the genomes of 14 plant viruses, represented by 65 different isolates (ApMV, 3; BPYV, 14; FCCV, 3; FClLV, 4; SCFaV, 1; SCrV-3, 3; SCrV-4, 3; SCV, 2; SMoV, 4; SMYEV, 14; SPaV, 5; SPV-1, 5; SVBV, 3; ToRSV, 1) among the 45 samples we analyzed. For each distinct infection (i.e., plant virus per sample), we selected the longest sequence as representative of the infecting isolate. Thus, a total of 65 partial sequences, including several near complete genomes, were annotated for their protein coding regions and deposited in GenBank.

We used the nucleotide identity to the closest homolog in GenBank as an estimate of the amount of additional nucleotide diversity each of these sequences provide. As indicated in Table 2, this study provides substantial new diversity for six of the 14 strawberry infecting viruses. Further, if we consider 90% nucleotide identity as the cutoff for a divergent isolate, we obtained a total of 19 new divergent isolates (BPYV, 1; SCrV-4, 2; SMoV, 1; SMYEV, 10; SPaV, 4; ToRSV, 1). The virus with the greatest amount of nucleotide diversity and largest number of divergent isolates was SMYEV, a positive sense RNA virus. In contrast, the virus with the lowest amount of additional nucleotide diversity, based on three sequenced isolates, was SVBV, a DNA genome virus.

Table 2.

New isolate sequences of strawberry-infecting viruses and their closest homolog in GenBank.

Strawberry mottle virus (SMoV), beet pseudo yellows virus (BPYV), strawberry pallidosis-associated virus (SPaV), tomato ringspot virus (ToRSV), strawberry mild yellow edge virus (SMYEV), strawberry vein banding virus (SVBV), strawberry crinkle virus (SCV), strawberry polerovirus 1 (SPV-1), apple mosaic virus (ApMV), strawberry chlorotic fleck virus (SCFaV), strawberry crinivirus 4 (SCrV-4), strawberry crinivirus 3 (SCrV-3), Fragaria chiloensis latent virus (FClLV) and Fragaria chiloensis cryptic virus (FCCV). Identity for GenBank accession number (ID), coverage (Cov). Blue shading, proportional to the value, highlights divergent isolates.

3.3. New RT-qPCR Assays

New RT-qPCR assays were developed for SMoV, BPYV, SPaV, ToRSV, SMYEV, SVBV, SCV, SPV-1, ApMV, SCFaV, SCrV-4, SCrV-3, FClLV and FCCV. According to the in silico analysis, most assays needed multiple forward and reverse primers and/or probes (Table 3) to cover all the known genetic diversity of these viruses. To reduce the number of potential primer combinations, we preferred using multiple primers to degenerate bases. The amplification efficiency varied among assays and ranged from 87.5% to 118.6% (Figure S1).

Table 3.

Newly designed assays for detection of strawberry-infecting viruses.

| Virus | Oligo Name | Sequence (5′ to 3′) | 5’ Reporter | Target Region | Length |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strawberry crinkle virus | SCV-F1 | ATAGGGAGGAAAAACATTATCCG | RdRp | 175 bp | |

| SCV-F2 | ATAGGGAGGAAAAACATCATCCG | ||||

| SCV-F3 | ATAGGGAGGAAAAACATAATCCG | ||||

| SCV-F4 | ATAGGGAGGAAGAATATCATCCG | ||||

| SCV-R1 | CATTGGTGGCAGACCCATCA | ||||

| SCV-R2 | CATTGGTAGCAGATCCATCA | ||||

| SCV-P1 | TGTCACAAGATGCTGGAAG | FAM | |||

| SCV-P2 | TGTCACAGGATGCTGGAA | FAM | |||

| Strawberry mottle virus | SMoV-F1 | GTAGTTTAGTGACAATCCAAGCGGA | 3’ UTR | 112 bp | |

| SMoV-F2 | GTAGTTTAGCGACAATCCAAGCGGA | ||||

| SMoV-R1 | ATCCCACTTAGGGGCAAAGAA | ||||

| SMoV-R2 | ATCCCACTTAGGGGCAGAGGA | ||||

| SMoV-P1 | TAGGACACCGGCTCT | FAM | |||

| Strawberry mild yellow edge virus | SMYEV-F1 | AGGCTTAAAATGGGAGTTTCTTCTC | CP | 83 bp | |

| SMYEV-F2 | AGGCTTTAAATGGGAGTTTCTTCTC | ||||

| SMYEV-F3 | AGGCTTCAAATGGGAGTTTCTTCTC | ||||

| SMYEV-R1 | ACGGTTAAGTAGTACTATATTCACTTCATGG | ||||

| SMYEV-R2 | ACGGTTAAGTAGTACTACATTCACTTCATGG | ||||

| SMYEV-P1 | TTCTTCTACCCAGCTCC | FAM | |||

| Strawberry pallidosis- associated virus | SPaV-F1 | TTTGTATTCTGGTATGAATTTGGAAACT | Polyprotein 1b | 123 bp | |

| SPaV-F2 | TCTTTATTCTGGGATGAATTTAGAGACT | ||||

| SPaV-R1 | ACACCTTGAGATTTATCAAATTTGCT | ||||

| SPaV-R2 | ACACCTTGGGATTTATCGAATTTACT | ||||

| SPaV-R3 | ACACCTTGAGATTTATCGAACTTGCT | ||||

| SPaV-P1 | TTCCAATTCAAGAGTACAGGAC | FAM | |||

| SPaV-P2 | TCCCAATTCAAGAGTATCGAAC | FAM | |||

| Strawberry vein banding virus | SVBV-F1 | TTTCTGTGACTATGAAACCAATCTTCT | CP | 99 bp | |

| SVBV-F2 | TTTCTGTGATTATGAAACCAATCTTCT | ||||

| SVBV-R1 | TCCATCCCGACAAAGGGTATT | ||||

| SVBV-R2 | TCCATTCCCACAAAGGGTATT | ||||

| SVBV-R3 | TCCATCCCAACAAAGGGTATT | ||||

| SVBV-P1 | CCTATAGAAGAATGGCCCAA | FAM | |||

| SVBV-P2 | CCAATAGAAGAATGGCCCAA | FAM | |||

| Strawberry polerovirus 1 | SPV1-F1 | GCCAGACGTCCCAGAGGTT | CP | 61 bp | |

| SPV1-R1 | GTCTTCCGGCATTCTGTTTCTT | ||||

| SPV1-P1 | AGAGGAGGAAAAGGAAA | FAM | |||

| Beet pseudo yellows virus | BPYV-F1 | AACGGTTGCAAGGTCAACATT | CP | 62 bp | |

| BPYV-R1 | GTTTCACGCTGTAGCCAATTTG | ||||

| BPYV-R2 | GTTTCACGCAGTAGCCAATTTG | ||||

| BPYV-R3 | GTTTCGCGCTGTAGCCAATTTG | ||||

| BPYV-P1 | CGGATGATGATTTGACG | FAM | |||

| Tomato ringspot virus | ToRSV-F1 | CCTGCAGAAGCAGATTGGC | CP | 140 bp | |

| ToRSV-F2 | CCTGCAGAAGCTGATTGGC | ||||

| ToRSV-F3 | CCTGCGGAAGCTGATTGGC | ||||

| ToRSV-R1 | GTTGGCCCGCGCCA | ||||

| ToRSV-R2 | GTAGGCCCGCGCCA | ||||

| ToRSV-R3 | GTTGGCCCACGCCA | ||||

| ToRSV-P1 | GGCGGTTCCTTTTATT | FAM | |||

| ToRSV-P2 | CGCCGTTCCTTTTATT | FAM | |||

| Apple mosaic virus | ApMV-F1 | AAGCGAACCCGAATAAGGGT | CP | 202 bp | |

| ApMV-F2 | AGCGAACCCGAACAAGGG | ||||

| ApMV-F3 | GCGAACCCGAATAAGGGTAAA | ||||

| ApMV-F4 | GCGAACCCGAACAAGGGTA | ||||

| ApMV-R1 | CGGAAGACATCGGCAAAGTC | ||||

| ApMV-R2 | ACGAAAGACATCGGCAAAGTC | ||||

| ApMV-P1 | CTTGGGAGGTTAGAGGC | FAM | |||

| ApMV-P2 | CTTGGGAGGTTAGTGTCC | FAM | |||

| Strawberry chlorotic fleck virus | SCFaV-F1 | TGAACTTGATCTGGGGCGTC | CP | 196 bp | |

| SCFaV-R1 | CCTCGAGCCCAGTGTCTCA | ||||

| SCFaV-P1 | AGGTTTGAAAAGAACCC | FAM | |||

| Strawberry crinivirus 3 | SCrV3-F1 | CAACCACCGTCTACAAACATTACAA | Polyprotein 1a | 126 bp | |

| SCrV3-R1 | GGACCACGGTCGGAAGTTG | ||||

| SCrV3-P1 | TTTGTAGAACGCAGGCACAGT | FAM | |||

| Strawberry crinivirus 4 | SCrV4-F1 | TTTGGGATTTCAGATTTGGGC | Polyprotein 1a | 155 bp | |

| SCrV4-F2 | ATAGGAATCTCGGATTTGGGC | ||||

| SCrV4-R1 | CGAGATCCAGATGAAGAAGTAACATAG | ||||

| SCrV4-R2 | CGAGATCCAGAGGAAGAAGTGAC | ||||

| SCrV4-P1 | TGTGAAGGAGAAGAATACCTA | FAM | |||

| Fragaria chiloensis latent virus | FClLV-F1 | CGTACTATCAATGAAACACTATCCAGAT | MP | 189 bp | |

| FClLV-R1 | TGGTTCAATCGGAACATTGTTC | ||||

| FClLV-P1 | CCATGTCTGATTTAGATAAA | FAM | |||

| Fragaria chiloensis cryptic virus | FCCV-F1 | CCTGACATAGCGTTCACACGA | RdRp | 96 bp | |

| FCCV-R1 | AAGTAGGACGTAATGAAACGCCTC | ||||

| FCCV-P1 | CAAATCAAGGTGAAGAGAA | FAM |

Forward primer (F), reverse primer (R), and TaqMan™ MGB probe (P). Coat protein (CP), movement protein (MP), RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp), and untranslated region (UTR). Default parameters for primer and probe Tm are 58–60 °C and 68–70 °C, respectively.

3.4. Detection of Viruses by RT-qPCR

To confirm the presence of viruses identified by HTS, source plants were analyzed by newly designed RT-qPCR assays. Virus detection was then validated by comparing HTS and RT-qPCR results for each virus-infected sample. In all cases, RT-qPCR and HTS results agreed (Table S2). Likewise, no amplification was observed in samples H2390, H2397, H2411, H2412 and H2430, confirming the virus-free status of these plants.

To further validate the new assays, twelve FPS positive control plants were analyzed by both HTS and RT-qPCR (Table S3). The following viruses were identified by both methods: SMoV (four plants), BPYV (seven plants), SPaV (five plants), SMYEV (three plants), SVBV (two plants), and SPV-1 (three plants).

4. Discussion

The primary objectives of this study were to increase available genetic diversity of strawberry viruses by characterizing a diverse set of infected plants and to develop a comprehensive set of RT-qPCR assays for detecting viruses infecting strawberries. The new sequence resources were utilized in the design of the detection assays.

The NCGR provided us with a vast collection of accessions of geographically and genetically diverse provenance. From that collection, all strawberry samples identified as pathogen-infected were included in a viral metagenomic survey using HTS. This approach allowed us to efficiently obtain sequences for all viruses infecting the sample. It is the first such survey of this type in strawberry, templated on work done in previous crops [21,22,23]. The metagenomic analysis revealed the presence of 14 different strawberry infecting viruses, the majority of which had RNA genomes. More detailed HTS analyses indicated that 40 out of 45 plants were infected with at least one virus and 34 had mixed infections of up to five different viruses.

Considerable additional genetic diversity was observed in several cases of strawberry viruses. In total, 65 partial genome sequences from 14 strawberry-infecting viruses were deposited in GenBank. These represent a substantial contribution to sequence resources for strawberry viruses, increasing the number of sequences deposited in GenBank by approximately 10%. Moreover, these sequences extend the genetic diversity of strawberry infecting viruses characterized in previous amplicon-based studies [24,25,26,27]. Notably, our most highly divergent population of new virus isolates comes from SMYEV. Xiang et al. [28] also observed multiple highly divergent populations of SMYEV in their amplicon-based study. The lowest amount of additional genetic diversity was observed in SVBV; this result is also consistent with the lower mutation rates observed for DNA viruses [29].

Four different criniviruses infecting strawberry were found during the metagenomics survey (BPYV, SPaV, SCrV-3 and -4). Most of these viruses displayed considerable genetic diversity, with the exception of SCrV-3, which lacked divergent variants. In that sense, an outstanding question we believe needs to be addressed is whether SCrV-3 and SCrV-4 represent new virus species or whether they are strains of a known virus. Novel data, like those generated here, will help to understand the biology and molecular biology of criniviruses, which remains to be fully understood [30].

Utilizing these new genetic resources, a comprehensive set of new RT-qPCR detection assays were designed for strawberry viruses. New assays were validated in vitro to confirm their reliability. For example, twelve strawberry samples previously screened for viruses and located at FPS were retested using the newly designed RT-qPCR assays. While we did not compare the sensitivity of our new assays with other PCR-based methods such as end-point RT-PCR, it is generally accepted that RT-qPCR is a highly sensitive method. Multiple primers and probes were employed to detect diverse virus isolates, as demonstrated with a similar assay for grapevine leafroll-associated virus 3, a highly divergent virus infecting grapevine [31].

The high throughput nature of RT-qPCR is desirable for clean plant certification facilities that process large sample numbers. Except for previous work describing RT-qPCR assays for strawberry necrotic shock virus and SCV, there is a scarcity of published assays of this kind for detecting strawberry viruses [32,33]. The novel diagnostic tools described here address that scarcity, looking to improve the management of strawberry viruses in the United States and globally.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Robert R. Martin, USDA-ARS, and Missy Fix and Kim Hummer from the USDA-ARS NCGR, Corvallis, OR for providing the plant material used in this study.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/v13081442/s1, Figure S1: Standard curves generated from new RT-qPCR assays for strawberry viruses, Table S1: Sequencing data generated from strawberry samples, Table S2: Detection of strawberry viruses in NCGR samples via RT-qPCR, Table S3: Detection of strawberry viruses in different positive controls stored at Foundation Plant Services.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.D.-L., V.K., K.A.S., M.S.H. and M.A.R.; methodology, A.D.-L., K.A.S., M.S.H. and M.A.R.; software, A.D.-L. and K.A.S.; validation, A.D.-L., K.A.S., V.K., and M.S.H.; formal analysis, A.D.-L., K.A.S., V.K. and M.A.R.; investigation, A.D.-L., V.K., K.A.S., M.S.H. and M.A.R.; data curation, A.D.-L., K.A.S. and M.S.H.; writing–original draft preparation, A.D.-L. and K.A.S.; writing—review and editing, A.D.-L., V.K., K.A.S. and M.A.R.; supervision, M.A.R.; project administration M.A.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are openly available in GenBank, reference numbers MZ320192-MZ320216, MZ326662-MZ326687 and MZ351164-MZ351177.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Manganaris G.A., Goulas V., Vicente A.R., Terry L.A. Berry Antioxidants: Small Fruits Providing Large Benefits. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2014;94:825–833. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.6432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dale A., Luby J.J. The Strawberry into the 21st Century. Timber Press; Portland, OR, USA: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hummer K.E., Bassil N., Njuguna W. Fragaria. In: Kole C., editor. Wild Crop Relatives: Genomic and Breeding Resources: Temperate Fruits. Springer; Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: 2011. pp. 17–44. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Geisseler D., Horwath W.R. Strawberry Production in California. Fertil. Res. Educ. Program FREP. 2014;4 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maas J.L. Compendium of Strawberry Diseases. 2nd ed. The American Phytopathological Society; Saint Paul, MN, USA: 1998. (Diseases and Pests Compendium Series). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Converse R.H. Virus and Viruslike Diseases of Fragaria (Strawberry) Agriculture Handbook-United States Department of Agriculture, Combined Forest Pest Research and Development Program; Cowallis, OR, USA: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fránová J., Přibylová J., Koloniuk I. Molecular and Biological Characterization of a New Strawberry Cytorhabdovirus. Viruses. 2019;11:982. doi: 10.3390/v11110982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tzanetakis I.E., Martin R.R. Expanding Field of Strawberry Viruses Which Are Important in North America. Int. J. Fruit Sci. 2013;13:184–195. doi: 10.1080/15538362.2012.698164. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Osman F., Rwahnih M.A., Rowhani A. Improved Detection of Ilarviruses and Nepoviruses Affecting Fruit Trees Using Quantitative RT-QPCR. J. Plant Pathol. 2014;96:577–583. doi: 10.4454/JPP.V96I3.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xiang Y., Bernardy M., Bhagwat B., Wiersma P.A., DeYoung R., Bouthillier M. The Complete Genome Sequence of a New Polerovirus in Strawberry Plants from Eastern Canada Showing Strawberry Decline Symptoms. Arch. Virol. 2015;160:553–556. doi: 10.1007/s00705-014-2267-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ding X., Li Y., Hernández-Sebastià C., Abbasi P.A., Fisher P., Celetti M.J., Wang A. First Report of Strawberry Crinivirus 4 on Strawberry in Canada. Plant Dis. 2016;100:1254. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-01-16-0009-PDN. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen D., Ding X., Wang A., Zhang J., Wu Z. First Report of Strawberry Crinivirus 3 and Strawberry Crinivirus 4 on Strawberry in China. New Rep. 2018;37:24. doi: 10.5197/j.2044-0588.2018.037.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kesanakurti P., Belton M., Saeed H., Rast H., Boyes I., Rott M. Screening for Plant Viruses by next Generation Sequencing Using a Modified Double Strand RNA Extraction Protocol with an Internal Amplification Control. J. Virol. Methods. 2016;236:35–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2016.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Diaz-Lara A., Navarro B., Di Serio F., Stevens K., Hwang M.S., Kohl J., Vu S.T., Falk B.W., Golino D., Al Rwahnih M. Two Novel Negative-Sense RNA Viruses Infecting Grapevine Are Members of a Newly Proposed Genus within the Family Phenuiviridae. Viruses. 2019;11:685. doi: 10.3390/v11080685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bankevich A., Nurk S., Antipov D., Gurevich A.A., Dvorkin M., Kulikov A.S., Lesin V.M., Nikolenko S.I., Pham S., Prjibelski A.D., et al. SPAdes: A New Genome Assembly Algorithm and Its Applications to Single-Cell Sequencing. J. Comput. Biol. 2012;19:455–477. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2012.0021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Treangen T.J., Sommer D.D., Angly F.E., Koren S., Pop M. Next Generation Sequence Assembly with AMOS. Curr. Protoc. Bioinform. 2011;33:11–18. doi: 10.1002/0471250953.bi1108s33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bateman A., Coin L., Durbin R., Finn R.D., Hollich V., Griffiths-Jones S., Khanna A., Marshall M., Moxon S., Sonnhammer E.L.L., et al. The Pfam Protein Families Database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:D138–D141. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eddy S.R. Genome Informatics 2009. Imperial College Press; London, UK: 2009. A new generation of homology search tools based on probabilistic inference; pp. 205–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Diaz-Lara A., Stevens K., Klaassen V., Golino D., Al Rwahnih M. Comprehensive Real-Time RT-PCR Assays for the Detection of Fifteen Viruses Infecting Prunus spp. Plants. 2020;9:273. doi: 10.3390/plants9020273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Osman F., Leutenegger C., Golino D., Rowhani A. Real-Time RT-PCR (TaqMan®) Assays for the Detection of Grapevine Leafroll Associated Viruses 1–5 and 9. J. Virol. Methods. 2007;141:22–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2006.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coetzee B., Freeborough M.-J., Maree H.J., Celton J.-M., Rees D.J.G., Burger J.T. Deep Sequencing Analysis of Viruses Infecting Grapevines: Virome of a Vineyard. Virology. 2010;400:157–163. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alcalá-Briseño R.I., Casarrubias-Castillo K., López-Ley D., Garrett K.A., Silva-Rosales L. Network Analysis of the Papaya Orchard Virome from Two Agroecological Regions of Chiapas, Mexico. mSystems. 2020;5:e00423-19. doi: 10.1128/mSystems.00423-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Al Rwahnih M., Rowhani A., Westrick N., Stevens K., Diaz-Lara A., Trouillas F.P., Preece J., Kallsen C., Farrar K., Golino D. Discovery of Viruses and Virus-Like Pathogens in Pistachio Using High-Throughput Sequencing. Plant Dis. 2018;102:1419–1425. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-12-17-1988-RE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thompson J.R., Jelkmann W. The Detection and Variation of Strawberry Mottle Virus. Plant Dis. 2003;87:385–390. doi: 10.1094/PDIS.2003.87.4.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thompson J.R., Jelkmann W. Strain Diversity and Conserved Genome Elements in Strawberry Mild Yellow Edge Virus. Arch. Virol. 2004;149:1897–1909. doi: 10.1007/s00705-004-0353-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cieślińska M. Genetic Diversity of Seven Strawberry Mottle Virus Isolates in Poland. Plant Pathol. J. 2019;35:389. doi: 10.5423/PPJ.NT.12.2018.0306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koloniuk I., Fránová J., Sarkisova T., Přibylová J. Complete Genome Sequences of Two Divergent Isolates of Strawberry Crinkle Virus Coinfecting a Single Strawberry Plant. Arch. Virol. 2018;163:2539–2542. doi: 10.1007/s00705-018-3860-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xiang Y., Nie X., Bernardy M., Liu J., Su L., Bhagwat B., Dickison V., Holmes J., Grose J.M., Creelman A.C. Genetic Diversity of Strawberry Mild Yellow Edge Virus from Eastern Canada. Arch. Virol. 2020;165:923–935. doi: 10.1007/s00705-020-04561-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sanjuán R., Domingo-Calap P. Genetic Diversity and Evolution of Viral Populations. Ref. Modul. Life Sci. 2019:53–61. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-809633-8.20958-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kiss Z.A., Medina V., Falk B. Crinivirus Replication and Host Interactions. Front. Microbiol. 2013;4:99. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2013.00099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Diaz-Lara A., Klaassen V., Stevens K., Sudarshana M.R., Rowhani A., Maree H.J., Chooi K.M., Blouin A.G., Habili N., Song Y., et al. Characterization of Grapevine Leafroll-Associated Virus 3 Genetic Variants and Application towards RT-QPCR Assay Design. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0208862. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0208862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Skelton A.L., Boonham N., Posthuma K.I., Kirby M.J., Adams A.N., Mumford R.A. The Improved Detection of Strawberry Crinkle Virus Using Real-Time RT-PCR (TaqMan®); Proceedings of the X International Symposium on Small Fruit Virus Diseases 656; Valencia, Spain. 21–25 July 2003; pp. 81–86. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thekke Veetil T., Ho T., Moyer C., Whitaker V.M., Tzanetakis I.E. Detection of Strawberry Necrotic Shock Virus Using Conventional and TaqMan® Quantitative RT-PCR. J. Virol. Methods. 2016;235:176–181. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2016.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are openly available in GenBank, reference numbers MZ320192-MZ320216, MZ326662-MZ326687 and MZ351164-MZ351177.