Abstract

Social networking platforms have become an essential means for communicating feelings to the entire world due to rapid expansion in the Internet era. Several people use textual content, pictures, audio, and video to express their feelings or viewpoints. Text communication via Web-based networking media, on the other hand, is somewhat overwhelming. Every second, a massive amount of unstructured data is generated on the Internet due to social media platforms. The data must be processed as rapidly as generated to comprehend human psychology, and it can be accomplished using sentiment analysis, which recognizes polarity in texts. It assesses whether the author has a negative, positive, or neutral attitude toward an item, administration, individual, or location. In some applications, sentiment analysis is insufficient and hence requires emotion detection, which determines an individual’s emotional/mental state precisely. This review paper provides understanding into levels of sentiment analysis, various emotion models, and the process of sentiment analysis and emotion detection from text. Finally, this paper discusses the challenges faced during sentiment and emotion analysis.

Keywords: Affective computing, Natural language processing, Opinion mining, Pre-processing, Word embedding

Introduction

Human language understanding and human language generation are the two aspects of natural language processing (NLP). The former, however, is more difficult due to ambiguities in natural language. However, the former is more challenging due to ambiguities present in natural language. Speech recognition, document summarization, question answering, speech synthesis, machine translation, and other applications all employ NLP (Itani et al. 2017). The two critical areas of natural language processing are sentiment analysis and emotion recognition. Even though these two names are sometimes used interchangeably, they differ in a few respects. Sentiment analysis is a means of assessing if data is positive, negative, or neutral.

In contrast, Emotion detection is a means of identifying distinct human emotion types such as furious, cheerful, or depressed. “Emotion detection,” “affective computing,” “emotion analysis,” and “emotion identification” are all phrases that are sometimes used interchangeably (Munezero et al. 2014). People are using social media to communicate their feelings since Internet services have improved. On social media, people freely express their feelings, arguments, opinions on wide range of topics. In addition, many users give feedbacks and reviews various products and services on various e-commerce sites. User's ratings and reviews on multiple platforms encourage vendors and service providers to enhance their current systems, goods, or services. Today almost every industry or company is undergoing some digital transition, resulting in vast amounts of structured and unstructured increase data. The enormous task for companies is to transform unstructured data into meaningful insights that can help them in decision-making (Ahmad et al. 2020)

For instance, in the business world, vendors use social media platforms such as Instagram, YouTube, Twitter, and Facebook to broadcast information about their product and efficiently collect client feedback (Agbehadji and Ijabadeniyi 2021). People’s active feedback is valuable not only for business marketers to measure customer satisfaction and keep track of the competition but also for consumers who want to learn more about a product or service before buying it. Sentiment analysis assists marketers in understanding their customer's perspectives better so that they may make necessary changes to their products or services (Jang et al. 2013; Al Ajrawi et al. 2021). In both advanced and emerging nations, the impact of business and client sentiment on stock market performance may be witnessed. In addition, the rise of social media has made it easier and faster for investors to interact in the stock market. As a result, investor's sentiments impact their investment decisions which can swiftly spread and magnify over the network, and the stock market can be altered to some extent (Ahmed 2020). As a result, sentiment and emotion analysis has changed the way we conduct business (Bhardwaj et al. 2015).

In the healthcare sector, online social media like Twitter have become essential sources of health-related information provided by healthcare professionals and citizens. For example, people have been sharing their thoughts, opinions, and feelings on the Covid-19 pandemic (Garcia and Berton 2021). Patients were directed to stay isolated from their loved ones, which harmed their mental health. To save patients from mental health issues like depression, health practitioners must use automated sentiment and emotion analysis (Singh et al. 2021). People commonly share their feelings or beliefs on sites through their posts, and if someone seemed to be depressed, people could reach out to them to help, thus averting deteriorated mental health conditions.

Sentiment and emotion analysis plays a critical role in the education sector, both for teachers and students. The efficacy of a teacher is decided not only by his academic credentials but also by his enthusiasm, talent, and dedication. Taking timely feedback from students is the most effective technique for a teacher to improve teaching approaches (Sangeetha and Prabha 2020). Open-ended textual feedback is difficult to observe, and it is also challenging to derive conclusions manually. The findings of a sentiment analysis and emotion analysis assist teachers and organizations in taking corrective action. Since social site's inception, educational institutes are increasingly relying on social media like Facebook and Twitter for marketing and advertising purposes. Students and guardians conduct considerable online research and learn more about the potential institution, courses and professors. They use blogs and other discussion forums to interact with students who share similar interests and to assess the quality of possible colleges and universities. Thus, applying sentiment and emotion analysis can help the student to select the best institute or teacher in his registration process (Archana Rao and Baglodi 2017).

Sentiment and emotion analysis has a wide range of applications and can be done using various methodologies. There are three types of sentiment and emotion analysis techniques: lexicon based, machine learning based, and deep learning based. Each has its own set of benefits and drawbacks. Despite different sentiment and emotion recognition techniques, researchers face significant challenges, including dealing with context, ridicule, statements conveying several emotions, spreading Web slang, and lexical and syntactical ambiguity. Furthermore, because there are no standard rules for communicating feelings across multiple platforms, some express them with incredible effect, some stifle their feelings, and some structure their message logically. Therefore, it is a great challenge for researchers to develop a technique that can efficiently work in all domains.

In this review paper, Sect. 2, introduces sentiment analysis and its various levels, emotion detection, and psychological models. Section 3 discusses multiple steps involved in sentiment and emotion analysis, including datasets, pre-processing of text, feature extraction techniques, and various sentiment and emotion analysis approaches. Section 4 addresses multiple challenges faced by researchers during sentiment and emotion analysis. Finally, Sect. 5 concludes the work.

Background

Sentiment analysis

Many people worldwide are now using blogs, forums, and social media sites such as Twitter and Facebook to share their opinions with the rest of the globe. Social media has become one of the most effective communication media available. As a result, an ample amount of data is generated, called big data, and sentiment analysis was introduced to analyze this big data effectively and efficiently (Nagamanjula and Pethalakshmi 2020). It has become exceptionally crucial for industry or organization to comprehend the sentiments of the user. Sentiment analysis, often known as opinion mining, is a method for detecting whether an author’s or user’s viewpoint on a subject is positive or negative. Sentiment analysis is defined as the process of obtaining meaningful information and semantics from text using natural processing techniques and determining the writer’s attitude, which might be positive, negative, or neutral (Onyenwe et al. 2020). Since the purpose of sentiment analysis is to determine polarity and categorize opinionated texts as positive or negative, dataset’s class range involved in sentiment analysis is not restricted to just positive or negative; it can be agreed or disagreed, good or bad. It can also be quantified on a 5-point scale: strongly disagree, disagree, neutral, agree, or strongly agree (Prabowo and Thelwall 2009). For instance, Ye et al. (2009) applied sentiment analysis on reviews on European and US destinations labeled on the scale of 1 to 5. They associated 1-star or 2-star reviews with the negative polarity and more than 2-star reviews with positive polarity. Gräbner et al. (2012) built a domain-specific lexicon that consists of tokens with their sentiment value. These tokens were gathered from customer reviews in the tourism domain to classify sentiment into 5-star ratings from terrible to excellent in the tourism domain. Moreover, Sentiment analysis from the text can be performed at three levels discussed in the following section. Salinca (2015) applied machine learning algorithms on the Yelp dataset, which contains reviews on service providers scaled from 1 to 5. Sentiment analysis can be categorized at three levels, mentioned in the following section.

Levels of sentiment analysis

Sentiment analysis is possible at three levels: sentence level, document level, and aspect level. At the sentence-level or phrase-level sentiment analysis, documents or paragraphs are broken down into sentences, and each sentence’s polarity is identified (Meena and Prabhakar 2007; Arulmurugan et al. 2019; Shirsat et al. 2019). At the document level, the sentiment is detected from the entire document or record (Pu et al. 2019). The necessity of document-level sentiment analysis is to extract global sentiment from long texts that contain redundant local patterns and lots of noise. The most challenging aspect of document-level sentiment classification is taking into account the link between words and phrases and the full context of semantic information to reflect document composition (Rao et al. 2018; Liu et al. 2020a). It necessitates a deeper understanding of the intricate internal structure of sentiments and dependent words (Liu et al. 2020b). At the aspect level, sentiment analysis, opinion about a specific aspect or feature is determined. For instance, the speed of the processor is high, but this product is overpriced. Here, speed and cost are two aspects or viewpoints. Speed is mentioned in the sentence hence called explicit aspect, whereas cost is an implicit aspect. Aspect-level sentiment analysis is a bit harder than the other two as implicit features are hard to identify. Devi Sri Nandhini and Pradeep (2020) proposed an algorithm to extract implicit aspects from documents based on the frequency of co-occurrence of aspect with feature indicator and by exploiting the relation between opinionated words and explicit aspects. Ma et al. (2019) took care of the two issues concerning aspect-level analysis: various aspects in a single sentence having different polarities and explicit position of context in an opinionated sentence. The authors built up a two-stage model based on LSTM with an attention mechanism to solve these issues. They proposed this model based on the assumption that context words near to aspect are more relevant and need greater attention than farther context words. At stage one, the model exploits multiple aspects in a sentence one by one with a position attention mechanism. Then, at the second state, it identifies (aspect, sentence) pairs according to the position of aspect and context around it and calculates the polarity of each team simultaneously.

As stated earlier, sentiment analysis and emotion analysis are often used interchangeably by researchers. However, they differ in a few ways. In sentiment analysis, polarity is the primary concern, whereas, in emotion detection, the emotional or psychological state or mood is detected. Sentiment analysis is exceptionally subjective, whereas emotion detection is more objective and precise. Section 2.2 describes all about emotion detection in detail.

Emotion detection

Emotions are an inseparable component of human life. These emotions influence human decision-making and help us communicate to the world in a better way. Emotion detection, also known as emotion recognition, is the process of identifying a person’s various feelings or emotions (for example, joy, sadness, or fury). Researchers have been working hard to automate emotion recognition for the past few years. However, some physical activities such as heart rate, shivering of hands, sweating, and voice pitch also convey a person’s emotional state (Kratzwald et al. 2018), but emotion detection from text is quite hard. In addition, various ambiguities and new slang or terminologies being introduced with each passing day make emotion detection from text more challenging. Furthermore, emotion detection is not just restricted to identifying the primary psychological conditions (happy, sad, anger); instead, it tends to reach up to 6-scale or 8-scale depending on the emotion model.

Emotion models/emotion theories

In English, the word 'emotion' came into existence in the seventeenth century, derived from the French word 'emotion, meaning a physical disturbance. Before the nineteenth century, passion, appetite, and affections were categorized as mental states. In the nineteenth century, the word 'emotion' was considered a psychological term (Dixon 2012). In psychology, complex states of feeling lead to a change in thoughts, actions, behavior, and personality referred to as emotions. Broadly, psychological or emotion models are classified into two categories: dimensional and categorical.

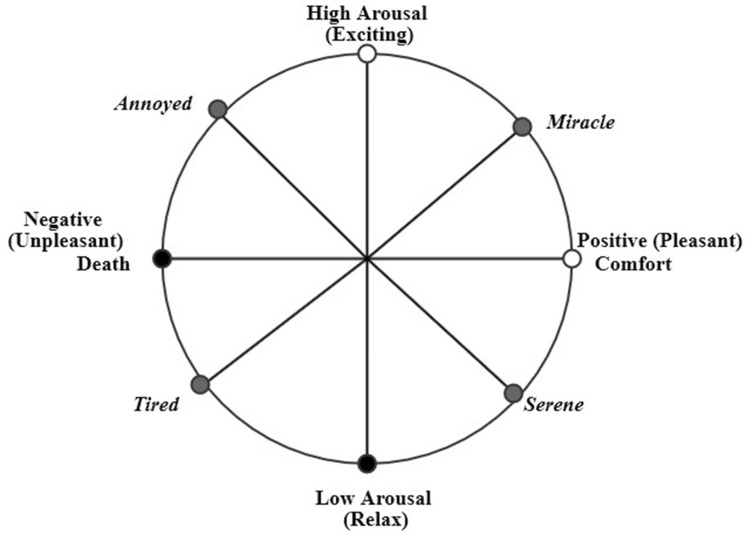

Dimensional Emotion model This model represents emotions based on three parameters: valence, arousal, and power (Bakker et al. 2014. Valence means polarity, and arousal means how exciting a feeling is. For example, delighted is more exciting than happy. Power or dominance signifies restriction over emotion. These parameters decide the position of psychological states in 2-dimensional space, as illustrated in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Dimensional model of emotions

Categorical Emotion model

In the categorical model, emotions are defined discretely, such as anger, happiness, sadness, and fear. Depending upon the particular categorical model, emotions are categorized into four, six, or eight categories.

Table 1 demonstrates numerous emotion models that are dimensional and categorical. In the realm of emotion detection, most researchers adopted Ekman and Plutchik’s emotion model. The emotional states defined by the models make up the set of labels used to annotate the sentences or documents. Batbaatar et al. (2019), Becker et al. (2017), Jain et al. (2017) adopted Ekman’s six basic emotions. Sailunaz and Alhajj (2019) used Ekman models for annotating tweets. Some researchers used customized emotion models by extending the model with one or two additional states. Roberts et al. (2012) used the Ekman model to annotate the tweets with the 'love' state. Ahmad et al. (2020) adopted the wheel of emotion modeled by Plutchik for labeling Hindi sentences with nine different Plutchik model states, decreasing semantic confusion, among other words. Plutchik and Ekman’s model's states are also utilized in various handcrafted lexicons like WordNet-Affect (Strapparava et al. 2004) and NRC (Mohammad and Turney 2013) word–emotion lexicons. Laubert and Parlamis (2019) referred to the Shaver model because of its three-level hierarchy structure of emotions. Valence or polarity is presented at the first level, followed by the second level consisting of five emotions, and the third level shows discrete 24 emotion states. Some researchers did not refer to any model and classified the dataset into three basic feelings: happy, sad, or angry.

Table 1.

Emotion models defined by various psychologists

| Emotion model | Type of model | No. of states | Psychological states | Representations | Discussion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ekman model (Ekman 1992) | Categorical | 6 | Anger, disgust, fear, joy, sadness, surprise | – | Ekman’s model consisted of six emotions, which act as a base for other emotion models like Plutchik model |

| Plutchik Wheel of Emotions (Plutchik 1982) | Dimensional | – | Joy, pensiveness, ecstasy, acceptance, sadness, fear, interest, rage, admiration, amazement, anger, vigilance boredom, annoyance, submission, serenity, apprehension, contempt, surprise, disapproval, distraction, grief, loathing, love, optimism, aggressiveness, remorse, anticipation, awe, terror, trust, disgust | Wheel | Plutchik considered two types of emotions: basic (Ekman model + Trust +Anticipation) and mixed emotions (made from the combination of basic emotions). Plutchik represented emotions on a colored wheel |

| Izard model (Izard 1992) | – | 10 | Anger, contempt, disgust, anxiety, fear, guilt, interest, joy, shame, surprise | – | – |

| Shaver model (Shaver et al. 1987) | Categorical | 6 | Sadness, joy, anger, fear, love, surprise | Tree | Shaver represented the primary, secondary and tertiary emotions in a hierarchal manner. The top-level of the tree presents these six emotions |

| Russell’s circumplex model (Russell 1980) | Dimensional | – | Sad, satisfied, Afraid, alarmed, frustrated, angry, happy, gloomy, annoyed, tired, relaxed, glad, aroused, astonished, at ease, tense, miserable, content, bored, calm, delighted, excited, depressed, distressed, serene, droopy, pleased, sleepy | – | Emotions are presented over the circumplex model |

| Tomkins model (Tomkins and McCarter 1964) | Categorical | 9 | Disgust, surprise-Startle, anger-rage, anxiety, fear-terror, contempt, joy, shame, interest-Excitement | – | Tomkins identified nine different emotions out of which six emotions are negative. Most of the emotions are defined as a pair |

| Lövheim Model (Lövheim 2012) | Dimensional | – | Anger, contempt, distress, enjoyment, terror, excitement, humiliation, startle | Cube | Lövheim arranged the emotions according to the amount of three substances (Noradrenaline, dopamine and Serotonin) on a 3-D cube |

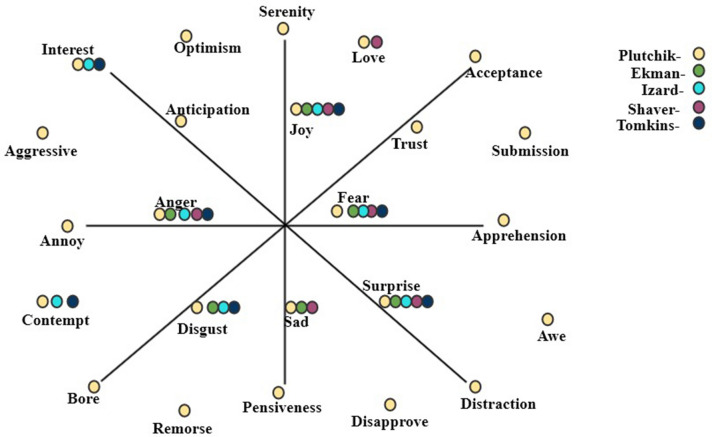

Figure 2 depicts the numerous emotional states that can be found in various models. These states are plotted on a four-axis by taking the Plutchik model as a base model. The most commonly used emotion states in different models include anger, fear, joy, surprise, and disgust, as depicted in the figure above. It can be seen from the figure that emotions on two sides of the axis will not always be opposite of each other. For example, sadness and joy are opposites, but anger is not the opposite of fear.

Fig. 2.

Illustration of various emotional models with some psychological states

Process of sentiment analysis and emotion detection

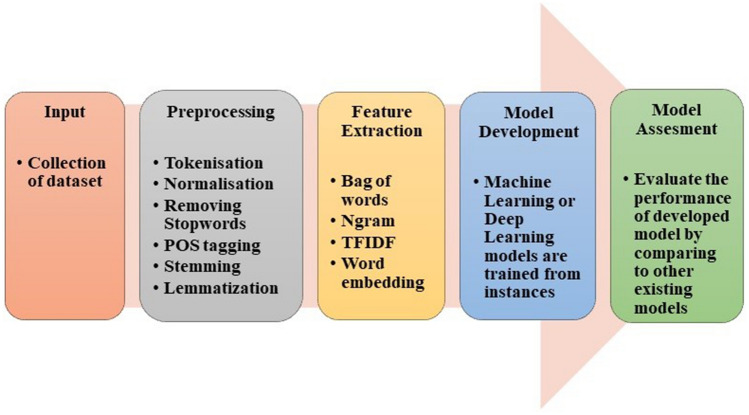

Process of sentiment analysis and emotion detection comes across various stages like collecting dataset, pre-processing, feature extraction, model development, and evaluation, as shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Basic steps to perform sentiment analysis and emotion detection

Datasets for sentiment analysis and emotion detection

Table 2 lists numerous sentiment and emotion analysis datasets that researchers have used to assess the effectiveness of their models. The most common datasets are SemEval, Stanford sentiment treebank (SST), international survey of emotional antecedents and reactions (ISEAR) in the field of sentiment and emotion analysis. SemEval and SST datasets have various variants which differ in terms of domain, size, etc. ISEAR was collected from multiple respondents who felt one of the seven emotions (mentioned in the table) in some situations. The table shows that datasets include mainly the tweets, reviews, feedbacks, stories, etc. A dimensional model named valence, arousal dominance model (VAD) is used in the EmoBank dataset collected from news, blogs, letters, etc. Many studies have acquired data from social media sites such as Twitter, YouTube, and Facebook and had it labeled by language and psychology experts in the literature. Data crawled from various social media platform's posts, blogs, e-commerce sites are usually unstructured and thus need to be processed to make it structured to reduce some additional computations outlined in the following section.

Table 2.

Datasets for sentiment analysis and emotion detection

| Dataset | Data size | Sentiment/emotion analysis | Sentiments/emotions | Range | Domain |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stanford Sentiment Treebank (Chen et al. 2017) | 118,55 reviews in SST-1 | Sentiment analysis | Very positive, positive, negative, very negative and neutral. | 5 | Movie reviews |

| 9613 reviews in SST-2 | Sentiment analysis | Positive and negative | 2 | Movie reviews | |

| SemEval Tasks (Ma et al. 2019; Ahmad et al. 2020) | SemEval- 2014 (Task 4): 5936 reviews for training and 1758 reviews for testing | Sentiment analysis | Positive, negative and neutral | 3 | Laptop and Restaurant reviews |

| SemEval-2018 (Affects in dataset Task): 7102 tweets in Emotion and Intensity for ordinal classification (EI-oc) | Emotion analysis | Anger, Joy, sad and fear | 4 | Tweets | |

| Thai fairy tales (Pasupa and Ayutthaya 2019) | 1964 sentences | Sentiment analysis | Positive, negative and neutral | 3 | Children tales |

| SS-Tweet (Symeonidis et al. 2018) | 4242 | Sentiment Analysis | Positive strength and Negative strength | 1 to 5 for positive and to for negative | Tweets |

| EmoBank (Buechel and Hahn 2017) | 10,548 | Emotion analysis | Valence, Arousal Dominance model (VAD) | – | News, blogs, fictions, letters etc. |

| International Survey of Emotional Antecedents and Reactions (ISEAR) (Seal et al. 2020) | Around 7500 sentences | Emotion analysis | Guilt, Joy, Shame, Fear, sadness, disgust | 7 | Incident reports. |

| Alm gold standard data set (Agrawal and An 2012) | 1207 sentences | Emotion analysis | happy, fearful, sad, surprised and angry-disgust(combined) | 5 | Fairy tales |

| EmoTex (Hasan et al. 2014) | 134,100 sentences | Emotion analysis | Circumplex model | – | |

| Text Affect (Chaffar and Inkpen 2011) | 1250 sentences | Emotion analysis | Ekman | 6 | Google news |

| Neviarouskaya Dataset (Alswaidan and Menai 2020) | Dataset 1: 1000 sentences and Dataset 2: 700 sentences | Emotion analysis | Izard | 10 | Stories and blogs |

| Aman’s dataset (Hosseini 2017) | 1890 sentences | Emotion analysis | Ekman with neutral class | 7 | Blogs |

Pre-processing of text

On social media, people usually communicate their feelings and emotions in effortless ways. As a result, the data obtained from these social media platform's posts, audits, comments, remarks, and criticisms are highly unstructured, making sentiment and emotion analysis difficult for machines. As a result, pre-processing is a critical stage in data cleaning since the data quality significantly impacts many approaches that follow pre-processing. The organization of a dataset necessitates pre-processing, including tokenization, stop word removal, POS tagging, etc. (Abdi et al. 2019; Bhaskar et al. 2015). Some of these pre-processing techniques can result in the loss of crucial information for sentiment and emotion analysis, which must be addressed.

Tokenization is the process of breaking down either the whole document or paragraph or just one sentence into chunks of words called tokens (Nagarajan and Gandhi 2019). For instance, consider the sentence “this place is so beautiful” and post-tokenization, it will become 'this,' "place," is, "so," beautiful.’ It is essential to normalize the text for achieving uniformity in data by converting the text into standard form, correcting the spelling of words, etc. (Ahuja et al. 2019).

Unnecessary words like articles and some prepositions that do not contribute toward emotion recognition and sentiment analysis must be removed. For instance, stop words like "is," "at," "an," "the" have nothing to do with sentiments, so these need to be removed to avoid unnecessary computations (Bhaskar et al. 2015; Abdi et al. 2019). POS tagging is the way to identify different parts of speech in a sentence. This step is beneficial in finding various aspects from a sentence that are generally described by nouns or noun phrases while sentiments and emotions are conveyed by adjectives (Sun et al. 2017).

Stemming and lemmatization are two crucial steps of pre-processing. In stemming, words are converted to their root form by truncating suffixes. For example, the terms "argued" and "argue" become "argue." This process reduces the unwanted computation of sentences (Kratzwald et al. 2018; Akilandeswari and Jothi 2018). Lemmatization involves morphological analysis to remove inflectional endings from a token to turn it into the base word lemma (Ghanbari-Adivi and Mosleh 2019). For instance, the term "caught" is converted into "catch" (Ahuja et al. 2019). Symeonidis et al. (2018) examined the performance of four machine learning models with a combination and ablation study of various pre-processing techniques on two datasets, namely SS-Tweet and SemEval. The authors concluded that removing numbers and lemmatization enhanced accuracy, whereas removing punctuation did not affect accuracy.

Feature extraction

The machine understands text in terms of numbers. The process of converting or mapping the text or words to real-valued vectors is called word vectorization or word embedding. It is a feature extraction technique wherein a document is broken down into sentences that are further broken into words; after that, the feature map or matrix is built. In the resulting matrix, each row represents a sentence or document while each feature column represents a word in the dictionary, and the values present in the cells of the feature map generally signify the count of the word in the sentence or document. To carry out feature extraction, one of the most straightforward methods used is 'Bag of Words' (BOW), in which a fixed-length vector of the count is defined where each entry corresponds to a word in a pre-defined dictionary of words. The word in a sentence is assigned a count of 0 if it is not present in the pre-defined dictionary, otherwise a count of greater than or equal to 1 depending on how many times it appears in the sentence. That is why the length of the vector is always equal to the words present in the dictionary. The advantage of this technique is its easy implementation but has significant drawbacks as it leads to a sparse matrix, loses the order of words in the sentence, and does not capture the meaning of a sentence (Bandhakavi et al. 2017; Abdi et al. 2019). For example, to represent the text “are you enjoying reading” from the pre-defined dictionary I, Hope, you, are, enjoying, reading would be (0,0,1,1,1,1). However, these representations can be improved by pre-processing of text and by utilizing n-gram, TF-IDF.

The N-gram method is an excellent option to resolve the order of words in sentence vector representation. In an n-gram vector representation, the text is represented as a collaboration of unique n-gram means groups of n adjacent terms or words. The value of n can be any natural number. For example, consider the sentence “to teach is to touch a life forever” and n = 3 called trigram will generate 'to teach is,' 'teach is to,' 'is to touch,' 'to touch a,' 'touch a life,' 'a life forever.' In this way, the order of the sentence can be maintained (Ahuja et al. 2019). N-grams features perform better than the BOW approach as they cover syntactic patterns, including critical information (Chaffar and Inkpen 2011). However, though n-gram maintains the order of words, it has high dimensionality and data sparsity (Le and Mikolov 2014).

Term frequency-inverse document frequency, usually abbreviated as TFIDF, is another method commonly used for feature extraction. This method represents text in matrix form, where each number quantifies how much information these terms carry in a given document. It is built on the premise that rare terms have much information in the text document (Liu et al. 2019). Term frequency is the number of times a word w appears in a document divided by the total number of words W in the document, and IDF is log (total number of documents (N) divided by the total number of documents in which word w appears (n)) (Songbo and Jin 2008). Ahuja et al. (2019) implemented six pre-processing techniques and compared two feature extraction techniques to identify the best approach. They applied six machine learning algorithms and used n-grams with n = 2 and TF-IDF for feature extraction over the SS-tweet dataset and concluded TF-IDF gives better performance over n-gram.

The availability of vast volumes of data allows a deep learning network to discover good vector representations. Feature extraction with word embedding based on neural networks is more informative. In neural network-based word embedding, the words with the same semantics or those related to each other are represented by similar vectors. This is more popular in word prediction as it retains the semantics of words. Google’s research team, headed by Tomas Mikolov, developed a model named Word2Vec for word embedding. With Word2Vec, it is possible to understand for a machine that “queen” + “female” + “male” vector representation would be the same as a vector representation of “king” (Souma et al. 2019).

Other examples of deep learning-based word embedding models include GloVe, developed by researchers at Stanford University, and FastText, introduced by Facebook. GloVe vectors are faster to train than Word2vec. FastText vectors have better accuracy as compared to Word2Vec vectors by several varying measures. Yang et al. (2018) proved that the choice of appropriate word embedding based on neural networks could lead to significant improvements even in the case of out of vocabulary (OOV) words. Authors compared various word embeddings, trained using Twitter and Wikipedia as corpora with TF-IDF word embedding.

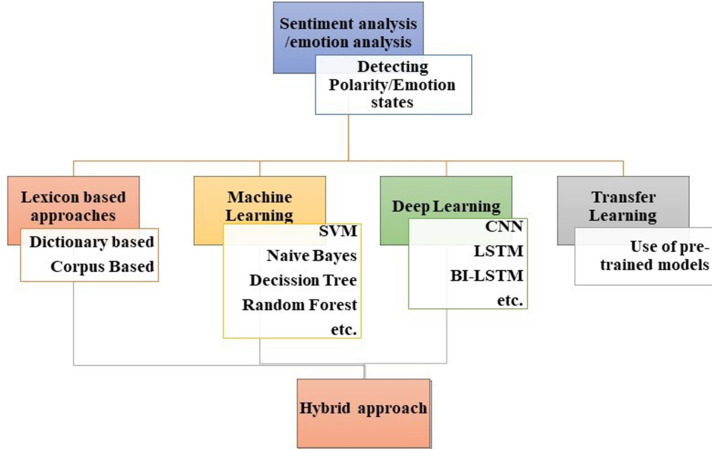

Techniques for sentiment analysis and emotion detection

Figure 4 presents various techniques for sentiment analysis and emotion detection which are broadly classified into a lexicon-based approach, machine learning-based approach, deep learning-based approach. The hybrid approach is a combination of statistical and machine learning approaches to overcome the drawbacks of both approaches. Transfer learning is also a subset of machine learning which allows the use of the pre-trained model in other similar domain.

Fig. 4.

Techniques for sentiment analysis and emotion detection

Sentiment analysis techniques

Lexicon-based approach This method maintains a word dictionary in which each positive and negative word is assigned a sentiment value. Then, the sum or mean of sentiment values is used to calculate the sentiment of the entire sentence or document. However, Jurek et al. (2015) tried a different approach called the normalization function to calculate the sentiment value more accurately than this basic summation and mean function. Dictionary-based approach and corpus-based approach are two types of lexicon-based approaches based on sentiment lexicon. In general, a dictionary maintains words of some language systemically, whereas a corpus is a random sample of text in some language. The exact meaning applies here in the dictionary-based approach and corpus-based approach. In the dictionary-based approach, a dictionary of seed words is maintained (Schouten and Frasincar 2015). To create this dictionary, the first small set of sentiment words, possibly with very short contexts like negations, is collected along with its polarity labels (Bernabé-Moreno et al. 2020). The dictionary is then updated by looking for their synonymous (words with the same polarity) and antonymous (words with opposite polarity). The accuracy of sentiment analysis via this approach will depend on the algorithm. However, this technique does not contain domain specificity. The Corpus-based approach solves the limitations of the dictionary-based approach by including domain-specific sentiment words where the polarity label is assigned to the sentiment word according to its context or domain. It is a data-driven approach where sentiment words along with context can be accessed. This approach can certainly be a rule-based approach with some NLP parsing techniques. Thus corpus-based approach tends to have poor generalization but can attain excellent performance within a particular domain. Since the dictionary-based approach does not consider the context around the sentiment word, it leads to less efficiency. Thus, Cho et al. (2014) explicitly handled the contextual polarity to make dictionaries adaptable in multiple domains with a data-driven approach. They took a three-step strategy: merge various dictionaries, remove the words that do not contribute toward classification, and switch the polarity according to a particular domain.

SentiWordNet (Esuli and Sebastiani 2006) and Valence Aware Dictionary and Sentiment Reasoner (VADER) (Hutto and Gilbert 2014) are popular lexicons in sentiment. Jha et al. (2018) tried to extend the lexicon application in multiple domains by creating a sentiment dictionary named Hindi Multi-Domain Sentiment Aware Dictionary (HMDSAD) for document-level sentiment analysis. This dictionary can be used to annotate the reviews into positive and negative. The proposed method labeled 24% more words than the traditional general lexicon Hindi Sentiwordnet (HSWN), a domain-specific lexicon. The semantic relationships between words in traditional lexicons have not been examined, improving sentiment classification performance. Based on this premise, Viegas et al. (2020) updated the lexicon by including additional terms after utilizing word embeddings to discover sentiment values for these words automatically. These sentiment values were derived from “nearby” word embeddings of already existing words in the lexicon.

Machine Learning-based approach There is another approach for sentiment analysis called the machine learning approach. The entire dataset is divided into two parts for training and testing purposes: a training dataset and a testing dataset. The training dataset is the information used to train the model by supplying the characteristics of different instances of an item. The testing dataset is then used to see how successfully the model from the training dataset has been trained. Generally, the machine learning algorithms used for sentiment analysis fall under supervised classification. Different kinds of algorithms required for sentiment classification may include Naïve Bayes, support vector machine (SVM), decision trees, etc. each having its pros and cons. Gamon (2004) applied a support vector machine over 40,884 customer feedbacks collected from surveys. The authors implemented various feature set combinations and achieved accuracy up to 85.47%. Ye et al. (2009) worked with SVM, N-gram model, and Naïve Bayes on sentiment and review on seven popular destinations of Europe and the USA, which was collected from yahoo.com. The authors achieved an accuracy of up to 87.17% with the n-gram model. indent Bučar et al. (2018) created the lexicon called JOB 1.0 and labeled news corpora called SentiNews 1.0 for sentiment analysis in Slovene texts. JOB 1.0 consists of 25,524 headwords extended with sentiment scaling from – 5 to 5 based on the AFINN model. For the construction of corpora, data were scraped from various news Web media. Then, after cleaning and pre-processing of data, the annotators were asked to annotate 10,427 documents on the 1–5 scale where one means negative and 5 means very positive. Then these documents were labeled with positive, negative, and neutral labels as per the specific average scale rating. The authors observed that Naïve Bayes performed better as compared to the support vector machine (SVM). Naive Bayes achieved an F1 score above 90% in binary classification and an F1 score above 60% for the three-class classification of sentiments. Tiwari et al. (2020) implemented three machine learning algorithms called SVM, Naive Bayes, and maximum entropy with the n-gram feature extraction method on the rotten tomato dataset. The training and testing dataset constituted 1600 reviews in each. The authors observed a decrease in accuracy with higher values of n in n-grams such as n = four, five, and six. Soumya and Pramod (2020) classified 3184 Malayalam tweets into positive and negative opinions using different feature vectors like BOW, Unigram with Sentiwordnet, etc. The authors implemented machine learning algorithms like random forest and Naïve Bayes and observed that the random forest with an accuracy of 95.6% performs better with Unigram Sentiwordnet considering negation words.

Deep Learning-based Approach In recent years, deep learning algorithms are dominating other traditional approaches for sentiment analysis. These algorithms detect the sentiments or opinions from text without doing feature engineering. There are multiple deep learning algorithms, namely recurrent neural network and convolutional neural networks, that can be applied to sentiment analysis and gives results that are more accurate than those provided by machine learning models. This approach makes humans free from constructing the features from text manually as deep learning models extract those features or patterns themselves. Jian et al. (2010) used a model based upon neural networks technology for categorizing sentiments which consisted of sentimental features, feature weight vectors, and prior knowledge base. The authors applied the model to review the data of Cornell movie. The experimental results of this paper revealed that the accuracy level of the I-model is extraordinary compared to HMM and SVM. Pasupa and Ayutthaya (2019) executed five-fold cross-validation on the children’s tale (Thai) dataset and compared three deep learning models called CNN, LSTM, and Bi-LSTM. These models are applied with or without features: POS-tagging (pre-processing technique to identify different parts of speech); Thai2Vec (word embedding trained from Thai Wikipedia); sentic (to understand the sentiment of the word). The authors observed the best performance in the CNN model with all the three features mentioned earlier. As stated earlier, social media platforms act as a significant source of data in the field of sentiment analysis. Data collected from this social sites consist lot of noise due to its free writing syle of users. Therefore, Arora and Kansal (2019) proposed a model named Conv-char-Emb that can handle the problem of noisy data and use small memory space for embedding. For embedding, convolution neural network (CNN) has been used that uses less parameters in feature representation. Dashtipour et al. (2020) proposed a deep learning framework to carry out sentiment analysis in the Persian language. The researchers concluded that deep neural networks such as LSTM and CNN outperformed the existing machine learning algorithms on the hotel and product review dataset.

Transfer Learning Approach and Hybrid Approach Transfer learning is also a part of machine learning. A model trained on large datasets to resolve one problem can be applied to other related issues. Re-using a pre-trained model on related domains as a starting point can save time and produce more efficient results. Zhang et al. (2012) proposed a novel instance learning method by directly modeling the distribution between different domains. Authors classified the dataset: Amazon product reviews and Twitter dataset into positive and negative sentiments. Tao and Fang (2020) proposed extending recent classification methods in aspect-based sentiment analysis to multi-label classification. The authors also developed transfer learning models called XLNet and Bert and evaluated the proposed approach on different datasets Yelp, wine reviews rotten tomato dataset from other domains. Deep learning and machine learning approaches yield good results, but the hybrid approach can give better results since it overcomes the limitations of each traditional model. Mladenović et al. (2016) proposed a feature reduction technique, a hybrid framework made of sentiment lexicon and Serbian wordnet. The authors expanded both lexicons by addition some morphological sentiment words to avoid loss of critical information while stemming. Al Amrani et al. (2018) compared their hybrid model made of SVM and random forest model, i.e., RFSVM, on amazon’s product reviews. The authors concluded RFSVM, with an accuracy level of 83.4%, performs better than SVM with 82.4% accuracy and random forest with 81% accuracy individually over the dataset of 1000 reviews. Alqaryouti et al. (2020) proposed the hybrid of the rule-based approach and domain lexicons for aspect-level sentiment detection to understand people’s opinions regarding government smart applications. The authors concluded that the proposed technique outperforms other lexicon-based baseline models by 5%. Ray and Chakrabarti (2020) combined the rule-based approach to extract aspects with a 7-layer deep learning CNN model to tag each aspect. The hybrid model achieved 87% accuracy, whereas the individual models had 75% accuracy with rule-based and 80% accuracy with the CNN model.

Table 3 describes various machine learning and deep learning algorithms used for analyzing sentiments in multiple domains. Many researchers implemented the proposed models on their dataset collected from Twitter and other social networking sites. The authors then compared their proposed models with other existing baseline models and different datasets. It is observed from the table above that accuracy by various models ranges from 80 to 90%.

Table 3.

Work on sentiment analysis

| Reference | Level | Technique | Feature extraction | Learning algorithm | Domain | Dataset | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Songbo and Jin (2008) | Sentence | Machine learning | – | Centroid classifier, K-nearest Classifier, Winnow Classifier, Naïve Bayes, SVM | House, movie and education | Chn- sentiCorp | Micro F1 = 90.60% with SVM and IG and macro F1 = 90.43%. |

| Moraes (2013) | Aspect level | Machine learning and deep learning | Bag of words | Artificial neural network (ANN), Naïve Bayes, SVM | Movies, Books, GPS, Cameras | – | Accuracy = 86.5% on movie dataset, 87.3% on GPS dataset, 81.8% on book dataset 90.6% on camera dataset with ANN. |

| Tang et al. (2015) | Document-level | Deep learning | Word embeddings to dense document vector | UPNN (user product neutral network) based on CNN | Movies | Dataset collected from yelp dataset and IMDB | Accuracy = 58.5% with UPNN (no UP) and 60.8% with UPNN on Yelp 2014. |

| Dahou et al. (2016) | – | Deep learning | Word embedding built from Arabic corpus | Convolutional neural network (CNN) | Book, movie, restaurant etc. | LABR book reviews, Arabic sentiment tweet dataset, etc | Accuracy= 91.7% on and Accuracy = 89.6% unbalanced HTL and LABR dataset, respectively. |

| Ahuja et al. (2019) | Sentence | Machine learning | TF-IDF, n-gram | KNN, SVM, logistic regression, NB, random forest | – | SS-tweets | Accuracy = 57% with TF-IDF and logistic regression and accuracy = 51% with n-gram and random forest. |

| Untawale and Choudhari (2019) | – | Machine learning | – | Naïve Bayes and random forest | movie reviews | Rotten tomatoes, reviews from Times of India, etc | Naïve Bayes required more time and memory than random forest. |

| Shamantha et al. (2019) | - | Machine learning | – | Naïve bayes, SVM and random forest | Accuracy = above 80% with Naïve Bayes (3features) on 200 tweets. | ||

| Goularas and Kamis (2019) | – | Machine learning | – | Random forest and SVM | – | – | Accuracy = 95% with random forest. |

| Nandal et al. (2020) | Aspect level | Machine learning | – | SVM with different kernels: linear, radial basis function (RBF), and polynomial | – | Amazon reviews | Mean square error = 0.04 with radial basis function and 0.11 with linear kernel. |

| Sharma and Sharma (2020) | – | Machine learning and deep learning | – | Deep artificial neural network and SVM | Positive emotion rate = 87.5 with the proposed algorithm. | ||

| Mukherjee et al. (2021) | Sentence level | Machine learning and Deep Learning with negation prediction process | TF IDF | Naïve Bayes, support vector machines, artificial neural network (ANN), and recurrent neural network (RNN) | Cellphone reviews | Amazon reviews | Accuracy = 95.30% with RNN + Negation and 95.67% with ANN+negation. |

Emotion detection techniques

Lexicon-based Approach Lexicon-based approach is a keyword-based search approach that searches for emotion keywords assigned to some psychological states (Rabeya et al. 2017). The popular lexicons for emotion detection are WordNet-Affect (Strapparava et al. 2004 and NRC word–emotion lexicon (Mohammad and Turney 2013). WordNet-Affect is an extended form of WordNet which consists of affective words annotated with emotion labels. NRC lexicon consists of 14,182 words, each assigned to one particular emotion and two sentiments. These lexicons are categorical lexicons that tag each word with an emotional state for emotion classification. However, by ignoring the intensity of emotions, these traditional lexicons become less informative and less adaptable. Thus, Li et al. (2021) suggested an effective strategy to obtain word-level emotion distribution to assign emotions with intensities to the sentiment words by merging a dimensional dictionary named NRC-Valence arousal dominance. EmoSenticNet (Poria et al. 2014) also consists of a large number assigned to both qualitative and quantitative labels. Generally, researchers generate their lexicons and directly apply them for emotion analysis, but lexicons can also be used for feature extraction purposes. Abdaoui et al. (2017) took the benefit of using online translation tools to create a French lexicon called FEEL (French expanded emotion lexicon) consisting of more than 14,000 words with both polarity and emotion labels. This lexicon was created by increasing the number of words in the NRC emotion lexicon and semi-automatic translation using six online translators. Those entries obtained from at least three translators were considered pre-validated and then validated by the manual translator. Bandhakavi et al. (2017) applied a domain-specific lexicon for the process of feature extraction in emotion analysis. The authors concluded that features derived from their proposed lexicon outperformed the other baseline features. Braun et al. (2021) constructed a multilingual corpus called MEmoFC, which stands for Multilingual Emotional Football Corpus, consisting of football reports from English, Dutch and German Web sites and match statistics crawled from Goal.com. The corpus was created by creating two metadata tables: one explaining details of a match like a date, place, participation teams, etc., and the second table consisted of abbreviations of football clubs. Authors demonstrated the corpus with various approaches to know the influence of the reports on game outcomes.

Machine Learning-based Techniques Emotion detection or classification may require different types of machine learning models such as Naïve Bayes, support vector machine, decision trees, etc. Jain et al. (2017) extracted the emotions from multilingual texts collected from three different domains. The authors used a novel approach called rich site summary for data collection and applied SVM and Naïve Bayes machine learning algorithms for emotion classification of twitter text. Results revealed that an accuracy level of 71.4% was achieved with the Naïve Bayes algorithm. Hasan et al. (2019) evaluated the machine learning algorithms like Naïve Bayes, SVM, and decision trees to identify emotions in text messages. The task is divided into two subtasks: Task 1 includes a collection of the dataset from Twitter and automatic labeling of the dataset using hashtags and model training. Task 2 is developing a two-stage EmotexStream that separates emotionless tweets at the first stage and identifies emotions in the text by utilizing the models trained in the task1. The authors observed accuracy of 90% in classifying emotions. Asghar et al. (2019) aimed to apply multiple machine learning models on the ISEAR dataset to find the best classifier. They found that the logistic regression model performed better than other classifiers with a recall value of 83%.

Deep Learning and Hybrid Technique Deep learning area is part of machine learning that processes information or signals in the same way as the human brain does. Deep learning models contain multiple layers of neurons. Thousands of neurons are interconnected to each other, which speeds up the processing in a parallel fashion. Chatterjee et al. (2019) developed a model called sentiment and semantic emotion detection (SSBED) by feeding sentiment and semantic representations to two LSTM layers, respectively. These representations are then concatenated and then passed to a mesh network for classification. The novel approach is based on the probability of multiple emotions present in the sentence and utilized both semantic and sentiment representation for better emotion classification. Results are evaluated over their own constructed dataset with tweet conversation pairs, and their model is compared with other baseline models. Xu et al. (2020) extracted features emotions using two-hybrid models named 3D convolutional-long short-term memory (3DCLS) and CNN-RNN from video and text, respectively. At the same time, the authors implemented SVM for audio-based emotion classification. Authors concluded results by fusing audio and video features at feature level with MKL fusion technique and further combining its results with text-based emotion classification results. It provides better accuracy than every other multimodal fusion technique, intending to analyze the sentiments of drug reviews written by patients on social media platforms. Basiri et al. (2020) proposed two models using a three-way decision theory. The first model is a 3-way fusion of one deep learning model with the traditional learning method (3W1DT), while the other model is a 3-way fusion of three deep learning models with the conventional learning method (3W3DT). The results derived using the Drugs.com dataset revealed that both frameworks performed better than traditional deep learning techniques. Furthermore, the performance of the first fusion model was noted to be much better as compared to the second model in regards to accuracy and F1-metric. In recent days, social media platforms are flooded with posts related to covid-19. Singh et al. (2021) applied emotion detection analysis on covid-19 tweets collected from the whole world and India only with Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT) model on the Twitter data sets and achieved accuracy 94% approximately.

Transfer Learning Approach In traditional approaches, the common presumption is that the dataset is from the same domain; however, there is a need for a new model when the domain changes. The transfer learning approach allows you to reuse the existing pre-trained models in the target domain. For example, Ahmad et al. (2020) used a transfer learning technique due to the lack of resources for emotion detection in the Hindi language. The researchers pre-trained a model on two different English datasets: SemEval-2018, sentiment analysis, and one Hindi dataset with positive, neutral, conflict, and negative labels. They achieved a score of 0.53 f1 using the transfer learning and 0.47 using only base models CNN and Bi-LSTM with cross-lingual word embedding. Hazarika et al. (2020) created a TL-ERC model where the model was pre-trained over source multi-turn conversations and then transferred over emotion classification task on exchanged messages. The authors emphasized the issues like lack of labeled data in multi-conversations with the framework based on inductive transfer learning.

Table 4 shows that most researchers implemented models by combining machine learning and deep learning techniques with various feature extraction techniques. Most of the datasets are available in the English language. However, some researchers constructed the dataset of their regional language. For example, Sasidhar et al. (2020) created the dataset of Hindi-English code mixed with three basic emotions: happy, sad, and angry, and observed CNN-BILSTM gave better performance compared to others.

Table 4.

Work on emotion detection

| Reference | Approach | Feature extraction | Models | Datasets | Emotion model | No of emotions | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chaffar and Inkpen (2011) | Machine learning | Bag of words, N-grams, WordNetAffect | Naïve Bayes, decision tree, and SVM | Multiple dataset | Ekman with neutral class, Izard | 10 | Acuracy = 81.16% on Aman’s dataset and 71.69% on Global dataset |

| Kratzwald et al. (2018) | Deep learning with transfer learning approach | Customised embedding GloVe | Sent2Affect | Literary tales, election tweet Isear Headlines General tweets | – | – | F1-score = 68.8% on literary dataset with pre-trained Bi-LSTM |

| Sailunaz and Alhajj (2019) | Machine learning | NAVA (Noun Adverb, verb and Adjective) | SVM, Random forest, Naïve Bayes | ISEAR | Guilt, Joy, Shame, Fear, sadness, disgust | 6 | Accuracy = 43.24% on NAVA text with Naïve Bayes. |

| Shrivastava et al. (2019) | Deep learning | Word2Vec | Convolutional neural network | TV shows transcript | – | 7 | Training accuracy = 80.41% and 77.54% with CNN (7 emotions) |

| Batbaatar et al. (2019) | Deep learning | Word2Vec, GloVe, FastText, EWE | SENN | ISEAR, Emo Int, electoral tweets, etc | – | – | Acuracy = 98.8% with GloVe+EWE and SENN on emotion cause dataset |

| Ghanbari-Adivi and Mosleh (2019) | Deep learning | DoctoVec | Ensemble classifier, tree-structured parzen estimator (TPE) for tuning parameters | wonder, anger, hate, happy , sadness, and fear | 6 | OANC, CrowdFlower, ISEAR, | 99.49 on regular sentences |

| Xu et al. (2020) | Deep learning-based Hybrid Approach | – | 3DCLS model for visual , CNN-RNN for text and SVM for text | Moud and IEMOCAP | Happy, sad, angry, neutral | 4 | Accuracy = 96.75% by fusing audio and visual features at feature level on MOUD dataset |

| Adoma et al. (2020) | Pretrained transfer models (machine learning and deep learning) | – | BERT, RoBERTa, DistilBERT, and XLNet | ISEAR | shame, anger,fear, disgust,joy, sadness, and guilt | 7 | Accuracy = 74%, 79% , 69% for RoBERTa, BERT, respectively. |

| Chowanda et al. (2021) | Machine learning and Deep learning | sentistrength, N-gram and TF IDF | Generalised linear model, Naïve Bayes, fast-large margins, etc. | Affective Tweets | Anger, fear, sadness, joy | 4 | Accuracy = 92% and recall = 90% with the generalized linear model |

| Dheeraj and Ramakrishnudu (2021) | Deep learning | Glove | Multi-head attention with bidirectional long short-term memory and convolutional neural network (MHA-BCNN) | Patient doctor interactions from Webmd and Healthtap platforms | Anxiety, addiction, obsessive cleaning disorder (OCD), depression, etc | 6 | Accuracy = 97.8% using MHA-BCNN with Adam optimizer |

Model assessment

Finally, the model is compared with baseline models based on various parameters. There is a requirement of model evaluation metrics to quantify model performance. A confusion matrix is acquired, which provides the count of correct and incorrect judgments or predictions based on known actual values. This matrix displays true positive (TP), false negative (FN), false positive (FP), true negative (TN) values for data fitting based on positive and negative classes. Based on these values, researchers evaluated their model with metrics like accuracy, precision, and recall, F1 score, etc., mentioned in Table 5.

Table 5.

Evaluation metrics

| Evaluation metric | Description | Equation |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | It’s a statistic that sums up how well the model performs in all classes. It’s helpful when all types of classes are equally important. It is calculated as the ratio between the number of correct judgments to the total number of judgments. | (TP+TN)/(TP+TN+FP+FN) |

| Precision | It measures the accuracy of the model in terms of categorizing a sample as positive. It is determined as the ratio of the number of correctly categorized Positive samples to the total number of positive samples (either correctly or incorrectly). | TP/(TP+FP ) |

| Recall | This score assesses the model’s ability to identify positive samples. It is determined by dividing the number of Positive samples that were correctly categorized as Positive by the total number of Positive samples. | TP/(TP+FN) |

| F-measure | It is determined by calculating the harmonic mean of precision and recall. | (2*Precision*Recall)/(Precision+Recall) = (2*TP)/((2*TP)+FP+FN) |

| Sensitivity | It refers to the percentage of appropriately detected actual positives and it quantifies how effectively the positive class was anticipated. | TP/((TP+FN)) |

| Specificity | It is the complement of sensitivity, the true negative rate which sums up how effectively the negative class was anticipated. The sensitivity of an imbalanced categorization may be more interesting than specificity. | TN/(FP+TN) |

| Geometric-mean (G-mean) | It is a measure that combines sensitivity and specificity into a single value that balances both objectives. |

Challenges in sentiment analysis and emotion analysis

In the Internet era, people are generating a lot of data in the form of informal text. Social networking sites present various challenges, as shown in Fig. 5, which includes spelling mistakes, new slang, and incorrect use of grammar. These challenges make it difficult for machines to perform sentiment and emotion analysis. Sometimes individuals do not express their emotions clearly. For instance, in the sentence “Y have u been soooo late?”, 'why' is misspelled as 'y,' 'you' is misspelled as 'u,' and 'soooo' is used to show more impact. Moreover, this sentence does not express whether the person is angry or worried. Therefore, sentiment and emotion detection from real-world data is full of challenges due to several reasons (Batbaatar et al. 2019).

Fig. 5.

Challenges in sentiment analysis and emotion detection

One of the challenges faced during emotion recognition and sentiment analysis is the lack of resources. For example, some statistical algorithms require a large annotated dataset. However, gathering data is not difficult, but manual labeling of the large dataset is quite time-consuming and less reliable (Balahur and Turchi 2014). The other problem regarding resources is that most of the resources are available in the English language. Therefore, sentiment analysis and emotion detection from a language other than English, primarily regional languages, are a great challenge and an opportunity for researchers. Furthermore, some of the corpora and lexicons are domain specific, which limits their re-use in other domains.

Another common problem is usually seen on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram posts and conversations is Web slang. For example, the Young generation uses words like 'LOL,' which means laughing out loud to express laughter, 'FOMO,' which means fear of missing out, which says anxiety. The growing dictionary of Web slang is a massive obstacle for existing lexicons and trained models.

People usually express their anger or disappointment in sarcastic and irony sentences, which is hard to detect (Ghanbari-Adivi and Mosleh 2019). For instance, in the sentence, “This story is excellent to put you in sleep,” the excellent word signifies positive sentiment, but in actual the reviewer felt it quite dull. Therefore, sarcasm detection has become a tedious task in the field of sentiment and emotion detection.

The other challenge is the expression of multiple emotions in a single sentence. It is difficult to determine various aspects and their corresponding sentiments or emotions from the multi-opinionated sentence. For instance, the sentence “view at this site is so serene and calm, but this place stinks” shows two emotions, 'disgust' and 'soothing' in various aspects. Another challenge is that it is hard to detect polarity from comparative sentences. For example, consider two sentences 'Phone A is worse than phone B' and 'Phone B is worse than Phone A.' The word ’worse’ in both sentences will signify negative polarity, but these two sentences oppose each other (Shelke 2014).

Conclusion

In this paper, a review of the existing techniques for both emotion and sentiment detection is presented. As per the paper’s review, it has been analyzed that the lexicon-based technique performs well in both sentiment and emotion analysis. However, the dictionary-based approach is quite adaptable and straightforward to apply, whereas the corpus-based method is built on rules that function effectively in a certain domain. As a result, corpus-based approaches are more accurate but lack generalization. The performance of machine learning algorithms and deep learning algorithms depends on the pre-processing and size of the dataset. Nonetheless, in some cases, machine learning models fail to extract some implicit features or aspects of the text. In situations where the dataset is vast, the deep learning approach performs better than machine learning. Recurrent neural networks, especially the LSTM model, are prevalent in sentiment and emotion analysis, as they can cover long-term dependencies and extract features very well. But RNN with attention networks performs very well. At the same time, it is important to keep in mind that the lexicon-based approach and machine learning approach (traditional approaches) are also evolving and have obtained better outcomes. Also, pre-processing and feature extraction techniques have a significant impact on the performance of various approaches of sentiment and emotion analysis.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Pansy Nandwani, Email: pansynandwani.phd19cse@pec.edu.in, Email: pansynandwani1992@gmail.com.

Rupali Verma, Email: rupali@pec.edu.in.

References

- Abdaoui A, Azé J, Bringay S, Poncelet P. Feel: a French expanded emotion lexicon. Lang Resour Eval. 2017;51(3):833–855. doi: 10.1007/s10579-016-9364-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abdi A, Shamsuddin SM, Hasan S, Piran J. Deep learning-based sentiment classification of evaluative text based on multi-feature fusion. Inf Process Manag. 2019;56(4):1245–1259. doi: 10.1016/j.ipm.2019.02.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Adoma AF, Henry N-M, Chen W (2020) Comparative analyses of bert, roberta, distilbert, and xlnet for text-based emotion recognition. In: 2020 17th International Computer Conference on Wavelet Active Media Technology and Information Processing (ICCWAMTIP), IEEE, pp 117–121. 10.1109/ICCWAMTIP51612.2020.9317379

- Agbehadji IE, Ijabadeniyi A (2021) Approach to sentiment analysis and business communication on social media. In: Fong S, Millham R (eds) Bio-inspired algorithms for data streaming and visualization, big data management, and fog computing, Springer Tracts in Nature-Inspired Computing. Springer, Singapore. 10.1007/978-981-15-6695-0_9

- Agrawal A, An A (2012) Unsupervised emotion detection from text using semantic and syntactic relations. In: 2012 IEEE/WIC/ACM international conferences on web intelligence and intelligent agent technology, pp 346–353. 10.1109/WI-IAT.2012.170.

- Ahmad Z, Jindal R, Ekbal A, Bhattachharyya P. Borrow from rich cousin: transfer learning for emotion detection using cross lingual embedding. Expert Syst Appl. 2020;139:112851. doi: 10.1016/j.eswa.2019.112851. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed WM. Stock market reactions to domestic sentiment: panel CS-ARDL evidence. Res Int Bus Finance. 2020;54:101240. doi: 10.1016/j.ribaf.2020.101240. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ahuja R, Chug A, Kohli S, Gupta S, Ahuja P. The impact of features extraction on the sentiment analysis. Procedia Comput Sci. 2019;152:341–348. doi: 10.1016/j.procs.2019.05.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Akilandeswari J, Jothi G. Sentiment classification of tweets with non-language features. Procedia Comput Sci. 2018;143:426–433. doi: 10.1016/j.procs.2018.10.414. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Al Ajrawi S, Agrawal A, Mangal H, Putluri K, Reid B, Hanna G, Sarkar M (2021) Evaluating business yelp’s star ratings using sentiment analysis. Materials Today: Proceedings. 10.1016/j.matpr.2020.12.137

- Al Amrani Y, Lazaar M, El Kadiri KE. Random forest and support vector machine based hybrid approach to sentiment analysis. Procedia Comput Sci. 2018;127:511–520. doi: 10.1016/j.procs.2018.01.150. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alqaryouti O, Siyam N, Monem AA, Shaalan K (2020) Aspect-based sentiment analysis using smart government review data. Appl Comput Inf. 10.1016/j.aci.2019.11.003

- Alswaidan N, Menai MEB. A survey of state-of-the-art approaches for emotion recognition in text. Knowl Inf Syst. 2020;62(8):1–51. doi: 10.1007/s10115-020-01449-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Archana Rao PN, Baglodi K (2017) Role of sentiment analysis in education sector in the era of big data: a survey. Int J Latest Trends Eng Technol 22–24

- Arora M, Kansal V. Character level embedding with deep convolutional neural network for text normalization of unstructured data for twitter sentiment analysis. Soc Netw Anal Min. 2019;9(1):1–14. doi: 10.1007/s13278-019-0557-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arulmurugan R, Sabarmathi K, Anandakumar H. Classification of sentence level sentiment analysis using cloud machine learning techniques. Cluster Comput. 2019;22(1):1199–1209. doi: 10.1007/s10586-017-1200-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Asghar MZ, Subhan F, Imran M, Kundi FM, Shamshirband S, Mosavi A, Csiba P, Várkonyi-Kóczy AR (2019) Performance evaluation of supervised machine learning techniques for efficient detection of emotions from online content. arXiv preprint arXiv:190801587

- Bakker I, Van Der Voordt T, Vink P, De Boon J. Pleasure, arousal, dominance: Mehrabian and Russell revisited. Curr Psychol. 2014;33(3):405–421. doi: 10.1007/s12144-014-9219-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Balahur A, Turchi M. Comparative experiments using supervised learning and machine translation for multilingual sentiment analysis. Comput Speech Lang. 2014;28(1):56–75. doi: 10.1016/j.csl.2013.03.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bandhakavi A, Wiratunga N, Padmanabhan D, Massie S. Lexicon based feature extraction for emotion text classification. Pattern Recogn Lett. 2017;93:133–142. doi: 10.1016/j.patrec.2016.12.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Basiri ME, Abdar M, Cifci MA, Nemati S, Acharya UR. A novel method for sentiment classification of drug reviews using fusion of deep and machine learning techniques. Knowl Based Syst. 2020;198:105949. doi: 10.1016/j.knosys.2020.105949. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Batbaatar E, Li M, Ryu KH. Semantic-emotion neural network for emotion recognition from text. IEEE Access. 2019;7:111866–111878. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2934529. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Becker K, Moreira VP, dos Santos AG. Multilingual emotion classification using supervised learning: comparative experiments. Inf Process Manag. 2017;53(3):684–704. doi: 10.1016/j.ipm.2016.12.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bernabé-Moreno J, Tejeda-Lorente A, Herce-Zelaya J, Porcel C, Herrera-Viedma E. A context-aware embeddings supported method to extract a fuzzy sentiment polarity dictionary. Knowl-Based Syst. 2020;190:105236. doi: 10.1016/j.knosys.2019.105236. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bhardwaj A, Narayan Y, Dutta M, et al. Sentiment analysis for Indian stock market prediction using sensex and nifty. Procedia Comput Sci. 2015;70:85–91. doi: 10.1016/j.procs.2015.10.043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bhaskar J, Sruthi K, Nedungadi P. Hybrid approach for emotion classification of audio conversation based on text and speech mining. Procedia Comput Sci. 2015;46:635–643. doi: 10.1016/j.procs.2015.02.112. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Braun N, van der Lee C, Gatti L, Goudbeek M, Krahmer E. Memofc: introducing the multilingual emotional football corpus. Lang Resour Eval. 2021;55(2):389–430. doi: 10.1007/s10579-020-09508-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bučar J, Žnidaršič M, Povh J. Annotated news corpora and a lexicon for sentiment analysis in Slovene. Lang Resour Eval. 2018;52(3):895–919. doi: 10.1007/s10579-018-9413-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buechel S, Hahn U (2017) Emobank: Studying the impact of annotation perspective and representation format on dimensional emotion analysis. In: Proceedings of the 15th conference of the european chapter of the association for computational linguistics: volume 2, Short Papers, pp 578–585

- Chaffar S, Inkpen D (2011) Using a heterogeneous dataset for emotion analysis in text. In: Butz C, Lingras P (eds) Advances in artificial intelligence. Canadian AI 2011. Lecture notes in computer science, vol 6657. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. 10.1007/978-3-642-21043-3_8

- Chatterjee A, Gupta U, Chinnakotla MK, Srikanth R, Galley M, Agrawal P. Understanding emotions in text using deep learning and big data. Comput Hum Behav. 2019;93:309–317. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2018.12.029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen T, Xu R, He Y, Wang X. Improving sentiment analysis via sentence type classification using BILSTM-CRF and CNN. Expert Syst Appl. 2017;72:221–230. doi: 10.1016/j.eswa.2016.10.065. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cho H, Kim S, Lee J, Lee JS. Data-driven integration of multiple sentiment dictionaries for lexicon-based sentiment classification of product reviews. Knowl-Based Syst. 2014;71:61–71. doi: 10.1016/j.knosys.2014.06.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chowanda A, Sutoyo R, Tanachutiwat S, et al. Exploring text-based emotions recognition machine learning techniques on social media conversation. Procedia Comput Sci. 2021;179:821–828. doi: 10.1016/j.procs.2021.01.099. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dahou A, Xiong S, Zhou J, Haddoud MH, Duan P (2016) Word embeddings and convolutional neural network for arabic sentiment classification. In: Proceedings of coling 2016, the 26th international conference on computational linguistics: Technical papers, pp 2418–2427

- Dashtipour K, Gogate M, Li J, Jiang F, Kong B, Hussain A. A hybrid Persian sentiment analysis framework: integrating dependency grammar based rules and deep neural networks. Neurocomputing. 2020;380:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.neucom.2019.10.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Devi Sri Nandhini M, Pradeep G. A hybrid co-occurrence and ranking-based approach for detection of implicit aspects in aspect-based sentiment analysis. SN Comput Sci. 2020;1:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s42979-020-00138-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dheeraj K, Ramakrishnudu T (2021) Negative emotions detection on online mental-health related patients texts using the deep learning with MHA-BCNN model. Expert Syst Appl 182:115265

- Dixon T. “Emotion”: the history of a keyword in crisis. Emot Rev. 2012;4(4):338–344. doi: 10.1177/1754073912445814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekman P. An argument for basic emotions. Cognit Emot. 1992;6(3–4):169–200. doi: 10.1080/02699939208411068. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Esuli A, Sebastiani F. Sentiwordnet: a publicly available lexical resource for opinion mining. LREC, Citeseer. 2006;6:417–422. [Google Scholar]

- Gamon M (2004) Sentiment classification on customer feedback data: noisy data, large feature vectors, and the role of linguistic analysis. In: COLING 2004: Proceedings of the 20th international conference on computational linguistics, pp 841–847

- Garcia K, Berton L. Topic detection and sentiment analysis in twitter content related to covid-19 from brazil and the USA. Appl Soft Comput. 2021;101:107057. doi: 10.1016/j.asoc.2020.107057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghanbari-Adivi F, Mosleh M. Text emotion detection in social networks using a novel ensemble classifier based on Parzen tree estimator (tpe) Neural Comput Appl. 2019;31(12):8971–8983. doi: 10.1007/s00521-019-04230-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goularas D, Kamis S (2019) Evaluation of deep learning techniques in sentiment analysis from twitter data. In: 2019 International conference on deep learning and machine learning in emerging applications (Deep-ML), IEEE, pp 12–17

- Gräbner D, Zanker M, Fliedl G, Fuchs M, et al. (2012) Classification of customer reviews based on sentiment analysis. In: ENTER, Citeseer, pp 460–470

- Hasan M, Rundensteiner E, Agu E (2014) Emotex: detecting emotions in twitter messages. In: 2014 ASE BIGDATA/SOCIALCOM/CYBERSECURITY Conference. Stanford University, Academy of Science and Engineering (ASE), USA, ASE, pp 1–10

- Hasan M, Rundensteiner E, Agu E. Automatic emotion detection in text streams by analyzing twitter data. Int J Data Sci Anal. 2019;7(1):35–51. doi: 10.1007/s41060-018-0096-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hazarika D, Poria S, Zimmermann R, Mihalcea R. Conversational transfer learning for emotion recognition. Inf Fusion. 2020;65:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.inffus.2020.06.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hosseini AS. Sentence-level emotion mining based on combination of adaptive meta-level features and sentence syntactic features. Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2017;65:361–374. doi: 10.1016/j.engappai.2017.08.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hutto C, Gilbert E (2014) Vader: a parsimonious rule-based model for sentiment analysis of social media text. In: Proceedings of the international AAAI conference on web and social media, vol 8

- Itani M, Roast C, Al-Khayatt S. Developing resources for sentiment analysis of informal Arabic text in social media. Procedia Comput Sci. 2017;117:129–136. doi: 10.1016/j.procs.2017.10.101. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Izard CE (1992) Basic emotions, relations among emotions, and emotion-cognition relations. Psychol Rev 99(3):561–565 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Jain VK, Kumar S, Fernandes SL. Extraction of emotions from multilingual text using intelligent text processing and computational linguistics. J Comput Sci. 2017;21:316–326. doi: 10.1016/j.jocs.2017.01.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jang HJ, Sim J, Lee Y, Kwon O. Deep sentiment analysis: mining the causality between personality-value-attitude for analyzing business ads in social media. Expert Syst Appl. 2013;40(18):7492–7503. doi: 10.1016/j.eswa.2013.06.069. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jha V, Savitha R, Shenoy PD, Venugopal K, Sangaiah AK. A novel sentiment aware dictionary for multi-domain sentiment classification. Comput Electr Eng. 2018;69:585–597. doi: 10.1016/j.compeleceng.2017.10.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jian Z, Chen X, Wang Hs. Sentiment classification using the theory of ANNs. J China Univ Posts Telecommun. 2010;17:58–62. doi: 10.1016/S1005-8885(09)60606-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jurek A, Mulvenna MD, Bi Y. Improved lexicon-based sentiment analysis for social media analytics. Secur Inform. 2015;4(1):1–13. doi: 10.1186/s13388-015-0024-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kratzwald B, Ilić S, Kraus M, Feuerriegel S, Prendinger H. Deep learning for affective computing: text-based emotion recognition in decision support. Decis Support Syst. 2018;115:24–35. doi: 10.1016/j.dss.2018.09.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Laubert C, Parlamis J. Are you angry (happy, sad) or aren’t you? Emotion detection difficulty in email negotiation. Group Decis Negot. 2019;28(2):377–413. doi: 10.1007/s10726-018-09611-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Le Q, Mikolov T (2014) Distributed representations of sentences and documents. In: International conference on machine learning, pp 1188–1196

- Li Z, Xie H, Cheng G, Li Q (2021) Word-level emotion distribution with two schemas for short text emotion classification. Knowledge-Based Syst 227:107163

- Liu Y, Wan Y, Su X. Identifying individual expectations in service recovery through natural language processing and machine learning. Expert Syst Appl. 2019;131:288–298. doi: 10.1016/j.eswa.2019.04.063. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F, Zheng J, Zheng L, Chen C. Combining attention-based bidirectional gated recurrent neural network and two-dimensional convolutional neural network for document-level sentiment classification. Neurocomputing. 2020;371:39–50. doi: 10.1016/j.neucom.2019.09.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S, Lee K, Lee I. Document-level multi-topic sentiment classification of email data with bilstm and data augmentation. Knowl-Based Syst. 2020;197:105918. doi: 10.1016/j.knosys.2020.105918. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lövheim H. A new three-dimensional model for emotions and monoamine neurotransmitters. Med Hypoth. 2012;78(2):341–348. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2011.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma X, Zeng J, Peng L, Fortino G, Zhang Y. Modeling multi-aspects within one opinionated sentence simultaneously for aspect-level sentiment analysis. Future Gener Comput Syst. 2019;93:304–311. doi: 10.1016/j.future.2018.10.041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meena A, Prabhakar TV (2007) Sentence level sentiment analysis in the presence of conjuncts using linguistic analysis. In: Amati G, Carpineto C, Romano G (eds) Advances in information retrieval. ECIR 2007. Lecture notes in computer science, vol 4425. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. 10.1007/978-3-540-71496-5_53

- Mladenović M, Mitrović J, Krstev C, Vitas D. Hybrid sentiment analysis framework for a morphologically rich language. J Intell Inf Syst. 2016;46(3):599–620. doi: 10.1007/s10844-015-0372-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammad SM, Turney PD. Crowdsourcing a word-emotion association lexicon. Comput Intell. 2013;29(3):436–465. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8640.2012.00460.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moraes R, Valiati JF, Gavião Neto WP (2013) Document-level sentiment classification: an empirical comparison between SVM and ANN. Expert Syst Appl 40(2):621–633