Abstract

Purpose

Drawing on the uncertainty management theory, this study explores the relationships between paradoxical leader behaviors (PLB) and followers perceptions of overall justice and organizational citizenship behaviors (OCB), as well as the mediating role of two components of followers perceptions of renqing (affective interaction and discretionary consideration) and the moderating role of trait agreeableness.

Methods

This study employed two-wave surveys with the aim of reducing the potential risk of common method bias. Participants were 325 employees from seven enterprises located in Northern and Southwest China. A moderated-mediation path analysis based on Hayes’ Process Model was performed in AMOS to examine the hypotheses.

Results

Results from two-wave surveys of 325 Chinese employees indicated that PLB is positively related to followers perceptions of overall justice. Two components of followers perceptions of renqing significantly mediate the relationship between PLB and overall justice. Moreover, two components of perceptions of renqing and overall justice exert a serial mediation effect in the relationship of PLB and OCB. More importantly, followers trait agreeableness strengthens the effects of affective interaction on overall justice.

Conclusion

This study advances the current understandings of the influencing mechanisms between PLB and followers overall justice perceptions and OCB. It is suggested that leaders PLB will facilitate two components of followers perceptions of renqing first, then boost their perceptions of overall justice, which in turn leading to more OCB, especially for those followers who endorse more agreeableness.

Keywords: paradoxical leader behaviors, perception of renqing, overall justice, organizational citizenship behaviors, trait agreeableness

Introduction

Overall justice, defined as the extent to which employees perceive the justice of their organization as a whole,1,2 has been widely recognized as one crucial variable in the organizational settings. Numerous studies have confirmed that employees overall justice perceptions substantially affect their following attitudes and behaviors, such as job satisfaction, commitment, turnover intention,3 perceptions of organizational support,4 emotional exhaustion,5 task performance, organizational citizenship behaviors (OCB3), silence,6 and creativity.1 Considering the great importance of overall justice, an increasing number of studies have attempted to identify its antecedents. For example, research demonstrated that overall justice perceptions could be triggered by several individual and organizational factors including fairness propensity and fairness anchor,7 job insecurity,8 perceptions of distributive, procedural, interactional, and informational justice,9,10 as well as organizational trust,11 and corporate social responsibility.12

In addition, followers tend to interpret their leaders behaviors as providing information about the organization’s intentions and commitment,13 since leaders are usually regarded as key agents of the organization.14 Previous work has identified the critical role of various leaderships in affecting followers perceptions of overall justice, such as supervisor’s charismatic qualities,10 paternalistic leadership,15 and servant leadership.16 However, what remains unknown is the effect of paradoxical leader behavior (PLB), a typical Eastern-culture-rooted leadership construct, on followers perceptions of overall justice and their following behaviors.

PLB represents “leader behaviors that are seemingly competing, yet interrelated, to meet competing workplace demands simultaneously and over time”.17 It manifests in five “both-and” behavioral dimensions: (1) treating subordinates uniformly, while also allowing for individualization; (2) combining self-centeredness with other-centeredness; (3) maintaining decision control, while also allowing autonomy; (4) enforcing work requirements, while also allowing for flexibility; and (5) maintaining both distance and closeness.17 The core tenet of PLB is to respond to the paradoxical challenges and tensions in the organizational systems.18

PLB has primarily been associated with several positive employee outcomes.17,19 Apart from these studies, Tripathi et al (2018), on the contrary, found that the “both-and” essence of PLB challenges employees need for consistency and certainty, triggering defensive and counterproductive behavior.20 Indeed, Tripathi et al (2018) have spotlighted PLB’s potential for triggering employee uncertainty which in turn may elicit negative behavior, but to date, we are not aware of any published studies explaining why positive effects of PLB on employee outcomes have been repeatedly found in Chinese organizational settings even with the uncertainty tensions, and what cultural norms and values have impacts on these relationships.20 Hence, in this study, we drew on the theory of uncertainty management to address the above gaps in the literature.

Uncertainty management theory suggests that “uncertainty can prompt people’s heuristic processing of fairness information”21 and their fairness judgement “is greatly affected by the notion of whether the event violates or bolsters their cultural norms and values”.22,23 Given that PLB incorporate five unpredictable “both-and” dimensions which may trigger followers’ uncertainty,20 employees who follow PLB leaders tend to rely on their cultural norms to first form fairness judgment and then to guide their following social behaviors,21 such as organizational citizenship behavior (OCB3).

In particular, this study introduces one specific notion of Chinese culture — renqing, — to explore the effect of PLB on followers’ fairness judgment and OCB. Renqing connotes a set of social norms that requires people to conduct proper social actions, and to show appropriate emotional feelings for others.24,25 In organizational settings, Ren et al (2021) defined perceptions of renqing as the extent to which employees perceive that people’s actions in their organizations follow the renqing norm.15 It incorporates two components: affective interaction and discretionary consideration. The former focuses on the interpersonal interactions while the latter centers upon the managerial practices within the workplace.

The renqing norm requires people to treat others generously and charitably in their interactions,26 and meanwhile, it demands leaders to show flexibility27 rather than uniformity in the managerial practices, which are essentially in line with Chinese traditional mindset of yin-yang philosophy that “views the world as being holistic, dynamic, and dialectical”.28 Given that PLB was fundamentally conceptualized in yin-yang perspectives,17 it is reasonable to propose that PLB is positively associated with followers’ perceptions of affective interaction and discretionary consideration (ie, two components of perceptions of renqing), which in turn leads to a higher fairness judgment and more OCB.

In addition, prior studies verified the significant association between employees’ organizational justice perceptions and five-factor model personality traits; among them, agreeableness is one critical factor.29 Agreeableness is characterized by trust in and sympathy towards others.30 Agreeable individuals are more likely to be high in prosocial and functional tendencies (eg, conducting more OCB) due to their high interpersonal sensitivity.31 Although practicing and respecting the renqing norm is shown to be stronger in China than in other countries, within-culture individual differences are also robust.25,32 Therefore, we argue that followers’ agreeableness serves as a moderator in the relationship linking two components of perceptions of renqing and overall justice.

Drawing on the uncertainty management theory, we proposed and examined a moderated mediation model linking PLB to followers overall justice perceptions and OCB. The main contributions of this study are: (1) we examined the effect of PLB on followers perceptions of overall justice; (2) we found the mediating role of two components of perceptions of renqing linking PLB to overall justice; (3) we explored the serial mediating role of two components of perceptions of renqing and overall justice in the relationship between PLB and OCB; and (4) we revealed the moderating effect of agreeableness in the association between two components of perceptions of renqing and overall justice.

In so doing, we begin with the review of the focal variables to propose the moderated mediation model and hypotheses. Then we examine these hypotheses with two-wave surveys of employees from seven enterprises located in Northern and Southwest China. Finally, we discuss the theoretical and practical implications as well as limitations and future directions of our findings.

Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

PLB and Followers Perceptions of Overall Justice

As we introduced before, PLB has five “both-and” behavioral dimensions. The typical leader behaviors in each dimension were (1) “uses a fair approach to treat all subordinates uniformly, but also treats them as individuals”; (2) “shows a desire to lead, but allows others to share the leadership role”; (3) “controls important work issues, but allows subordinates to handle details”; (4) “stresses conformity in task performance, but allows for exceptions”; and (5) “keeps distance from subordinates, but does not remain aloof”.17

PLB has been confirmed to exert positive effects on Chinese employees outcomes, including psychological capital,18 psychological safety,19 engagement,33 proficient, adaptive, and proactive behavior,17 performance,34 and creativity.35 However, as every coin has two sides, Tripathi et al (2018) cautioned that the “both-and” essence of PLB may trigger followers feeling of uncertainty resulting in their defensive and counterproductive behavior.20 In this regard, we draw on uncertainty management theory to examine the effect of PLB on followers perceptions of overall justice.

Uncertainty management theory depicts that “when people feel uncertain or when they attend to the uncertain aspects of their worlds they have especially strong concerns about fairness”.21 Accordingly, we believe that employees whose leader evidences more PLB are prone to stronger concerns about justice. Given the fact that managers are often seen as core agents of the organization,14 followers tend to interpret leader behaviors to form a judgement of overall justice of their organization. In addition, Bos et al (2005; 2010) further identified a key facet underlying uncertainty management processing: people tend to form a fairness judgment when they subjectively believe that the situations or the events are in line with their cultural norms.22,23 Given that PLB has roots in a Chinese traditional mindset,17 it is reasonable to predict a positive association of PLB with followers perceptions of overall justice. Therefore, we propose:

H1. PLB is positively associated with followers perceptions of overall justice;

The Serial Mediating Role of Followers Perceptions of Renqing and Overall Justice

Uncertainty management theory presents a potential linking path in which PLB, as an antecedent, first stimulate followers feeling of uncertainty, then strengthen their concerns about justice, and finally guide their following behaviors. In particular, as defined by Bos et al (2005; 2010), the key facet of people’s fairness judgement is whether the event such as leader behaviors like PLB accord with their cultural norms and values.22,23 This study introduce a Chinese culturally-specific notion: renqing. Note that there is no direct English-language translation of renqing.15

Renqing manifests in every sphere of Chinese people’s social life26,36 and connotes a set of social norms.24,25 In Chinese organizations, employees perceptions of renqing incorporate two components: affective interaction and discretionary consideration.15 The renqing norm requires people to conduct proper social actions, and to show positive emotional feelings for others, which is practiced by helping, caring for others, and showing sympathy.26 In addition, to follow the renqing norm, Chinese managers are encouraged to show flexibility27 rather than uniformity, which somewhat manifest in leaders “both-and” behaviors as PLB. Therefore, it is reasonable to propose that PLB is in accordance with Chinese cultural norms of renqing, which in turn, leads to a higher fairness judgment.

OCB, defined as “individuals discretionary or extra-role behaviors aiming to facilitate organizational functioning, which are usually not included in the formal reward system”,37 has been identified as one critical outcome variable in the management literature.38 Generally, feeling that one has been treated fairly typically leads to positive behaviors such as OCB.3 Taken together, we argue that two components of followers perceptions of renqing (ie, affective interaction and discretionary consideration) and perceptions of overall justice serve as serial mediators in linking PLB to OCB.

H2. Two components of perceptions of renqing (ie, affective interaction and discretionary consideration) simultaneously mediate the relationship between PLB and followers perceptions of overall justice.

H3: Two components of perceptions of renqing (ie, affective interaction and discretionary consideration) and perceptions of overall justice serially mediate the relationship of PLB with followers OCB.

The Moderating Role of Followers Trait Agreeableness

Agreeableness, as one of the five factors personality traits, is featured with trust in and sympathy towards others.30 Agreeable individuals are regarded as high interpersonal sensitivity, and thus more prosocial attitudes and behaviors.31 For example, Törnroos et al (2019) found that agreeableness relates positively to procedural and interactional justice.29 Given the fact that there exist great within-culture individual differences in respecting and practicing the renqing norm,25,32 we believe that followers agreeableness serves as a moderator in the relationship linking two components of perceptions of renqing and overall justice. In particular, we argue that when perceiving a high level of perceptions of renqing at the workplace, agreeable employees may be more prone to stronger justice perceptions through their high sensitivity to the interpersonal interactions (ie, affective interaction) and managerial practices (discretionary consideration) characterized by helping, caring for others, showing sympathy, and flexibility. Hence, we propose:

H4. Trait agreeableness strengthens the effects of two components of followers perceptions of renqing (ie, affective interaction and discretionary consideration) on their perceptions of overall justice.

Methods

Participants and Procedure

This study, as one part of a large research project on the antecedents and consequences of perceptions of renqing in the workplace, recruited 600 participants working in seven enterprises located in Northern and Southwest China. Two waves of data were collected with the aim of reducing the potential risk of common method bias.39 Questionnaires were distributed to the employees with the assistance of human resources managers in each company. To assure confidentiality, and to reduce participants’ potential concerns about being evaluated, each questionnaire was enclosed within an envelope, and participants were informed that immediately after completing the questionnaire, they should put it back in the envelope, seal it, and then give it to their human resources manager who was collecting data on site.

In the first wave of surveys, a total of 530 employees reported their perceptions of the leaders PLB and their own trait agreeableness and demographic information, with a response rate of 88.3%. Two weeks later, questionnaires for measuring perceptions of renqing, overall justice, and OCB were administered to the employees who completed the first survey, with the help of the human resources managers; 464 were returned (77.3%), of which 361 responses were matched with the first survey. Excluding the incomplete ones, the final sample pool contained 325 valid responses. Of the 325 employees, 66% were male. Their average age was 33.8, and the average organizational tenure was 9.6 years. 54.7% of them had a university degree or above. 44.5% of the participants occupied managerial positions. 65.5% worked in state-owned enterprises, with the rest working in private-owned or foreign owned companies.

Measures

All key variables were rated using a six-point Likert-type scale (from 1 = strongly disagree to 6 = strongly agree) to avoid the central tendency bias found among Chinese respondents.40 We employed translation and back-translation procedures as suggested by Brislin (1986) to translate all English items into Chinese.41

PLB

PLB was measured with 22 items developed and validated by Zhang et al (2015).17 This scale has good convergent and divergent validity, as well as predictive validity on multiple performance criteria.17 Five sample items of each dimension are: “Uses a fair approach to treat all subordinates uniformly, but also treats them as individuals”; “Shows a desire to lead, but allows others to share the leadership role”; “Controls important work issues, but allows subordinates to handle details”; “Stresses conformity in task performance, but allows for exceptions”; and “Keeps distance from subordinates, but does not remain aloof”. The Cronbach’s α of this scale was 0.951.

Agreeableness

We used the four-item scale of agreeableness from the 20-item Mini International Personality Item Pool developed by Donnellan et al (2006).42 The Mini-IPIP is derived from the 50-item IPIP-Five Factor Model developed by Goldberg (1999).43 In this study, the Cronbach’s α for these four items was 0.606, just meeting the minimum level of 0.60 for acceptable reliability according to Nunnally (1967).44

Perceptions of Renqing

The measure of perceptions of renqing was taken from Ren et al (2020).45 The scale consists of two dimensions: affective interaction (9 items) and discretionary consideration (5 items). One sample item of affective interaction is “If an employee or an employee’s family is sick, the supervisor and coworkers will visit the patient and express their concerns”, and that of discretionary consideration is “In managerial practices, my organization will consider the special situations faced by the employees rather than impose uniformity in all cases”. The Cronbach’s αs for affective interaction and discretionary consideration were 0.914 and 0.841, respectively.

Overall Justice

The 3-item scale of overall justice developed by Kim and Leung (2007) was adopted.2 One sample item was “Overall, I believe I receive fair treatment from this organization”. The Cronbach’s α of this scale was 0.928.

OCB

OCB was assessed with a 16-item scale developed by Lee and Allen (2002).38 Two sample items of each dimension are “Help others who have been absent” and “Keep up with developments in the organization”. The Cronbach’s α of this scale was 0.950.

Control Variables

On the basis of previous studies of overall justice10 and OCB,46 this study included individual’s demographic variables as control variables, such as sex, age, organizational tenure, education level, and position in the organization. The education level was measured by five categories: middle school or below, high school, college, university, and postgraduate; position in the organization as four types: employees, junior manager, middle manager, and senior manager. Adding these controls did not alter the results of our tests. Accordingly, we followed suggested recommendations regarding the use of control variables,10,47 and did not include these variables in our final analyses.

Results

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) and Common Method Variance (CMV) Caution

Prior to testing our hypotheses, a series of CFA procedures were employed to evaluate the distinctiveness among the variables. perceptions of renqing contains two dimensions. The baseline model was a six-factor measurement model with PLB, affective interaction, discretionary consideration, agreeableness, overall justice, and OCB. To reduce inflated measurement errors resulting from multiple items for the latent variable,48 consistent with previous research,49 five-item parcels were created for PLB in line with its five dimensions; similarly, two-item parcels were created for OCB in line with its two dimensions. Using data obtained from the two-wave surveys, we examined four alternative models against the baseline six-factor model (Model 1). As shown in Table 1, Model 1 fitted the data well (χ2/df = 2.239, SRMR = 0.052, RMSEA = 0.062, CFI = 0.928, IFI = 0.928, NNFI = 0.919) and provided substantial improvement in fit indices over alternative models (Model 2–5).

Table 1.

Results of CFAs: Comparison of Alternative Measurement Models

| Models | Factors | χ2(df) | χ2/df | Δχ2(Δdf) | SRMR | RMSEA | CFI | IFI | NNFI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Six factors: PLB, AI, DC, Agreeableness, overall justice, OCB | 750.086 (335) | 2.239*** | 0.052 | 0.062 | 0.928 | 0.928 | 0.919 | |

| 2 | Five factors: AI and DC combined into one factor | 969.830 (340) | 2.852*** | 219.744***(5) | 0.060 | 0.076 | 0.891 | 0.891 | 0.878 |

| 3 | Four factors: AI and DC, overall justice and OCB combined into one factor, respectively | 1362.519 (344) | 3.961*** | 612.433***(9) | 0.101 | 0.096 | 0.823 | 0.824 | 0.806 |

| 4 | Three factors: AI, DC, overall justice and OCB combined into one factor | 1640.346 (347) | 4.727*** | 890.260***(12) | 0.075 | 0.107 | 0.775 | 0.776 | 0.755 |

| 5 | One factor: six factors combined into one factor | 2406.625 (350) | 6.876*** | 1656.539***(15) | 0.096 | 0.135 | 0.643 | 0.644 | 0.614 |

Note: ***p < 0.001.

Abbreviations: AI, affective interaction; DC, discretionary consideration.

For the use of self-report questionnaires, it is essential to detect whether there exists serious CMV. As recommended by Podsakoff et al (2003),39 the unmeasured latent method factor technique was applied to examine the degree of CMV. We constructed a latent factor called “CMV” by loading all indices of affective interaction, discretionary consideration, agreeableness, and overall justice, and five-item parcels of PLB and two-item parcels of OCB. Results revealed that the seven-factor measurement model regarding the CMV factor and key variables (χ2=660.398 df = 307, χ2/df = 2.151, SRMR = 0.048, RMSEA = 0.060, CFI = 0.939, IFI = 0.939, NNFI = 0.924) fit the data better than the baseline six-factor model, but the improvement of the goodness of fit was slight (Δχ2 = 89.688, Δdf = 28, p<0.05). Additionally, we calculated the average variance extracted (AVE) by the “CMV”, and it was 0.34, which was below the cutoff (0.50) to identify the presence of a latent construct.50 In conclusion, even though CMV may exist, we believe it does not undermine the research validity of this study.

Descriptive Statistics

Table 2 displays the means, standard deviations, and correlations among all variables. We find that key variables, ie, PLB, affective interaction, discretionary consideration, agreeableness, overall justice, and OCB, are positively related to each other, offering preliminary evidence for our hypotheses.

Table 2.

Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sex | 1.34 | 0.47 | ||||||||||

| 2 | Age | 33.77 | 8.26 | −0.171** | |||||||||

| 3 | Organizational tenure | 9.61 | 8.99 | −0.143* | 0.853** | ||||||||

| 4 | Education | 3.35 | 1.03 | 0.177** | −0.409** | −0.337** | |||||||

| 5 | Position | 1.55 | 0.67 | −0.122* | 0.251** | 0.187** | 0.238** | ||||||

| 6 | PLB | 4.21 | 0.91 | −0.026 | 0.043 | −0.013 | 0.037 | 0.101 | |||||

| 7 | AI | 4.50 | 0.91 | −0.142* | 0.133* | 0.136* | −0.051 | 0.111* | 0.602** | ||||

| 8 | DC | 4.14 | 0.92 | −0.162** | 0.072 | 0.089 | −0.035 | 0.064 | 0.436** | 0.646** | |||

| 9 | Agreeableness | 4.32 | 0.79 | 0.058 | −0.007 | −0.007 | 0.096 | 0.068 | 0.242** | 0.287** | 0.115* | ||

| 10 | Overall justice | 4.18 | 1.13 | −0.097 | 0.112* | 0.140* | −0.116* | 0.036 | 0.460** | 0.589** | 0.444** | 0.172** | |

| 11 | OCB | 4.65 | 0.77 | −0.103 | 0.205** | 0.199** | −0.027 | 0.192** | 0.383** | 0.652** | 0.597** | 0.321** | 0.399** |

Notes: **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05.

Abbreviations: AI, affective interaction; DC, discretionary consideration.

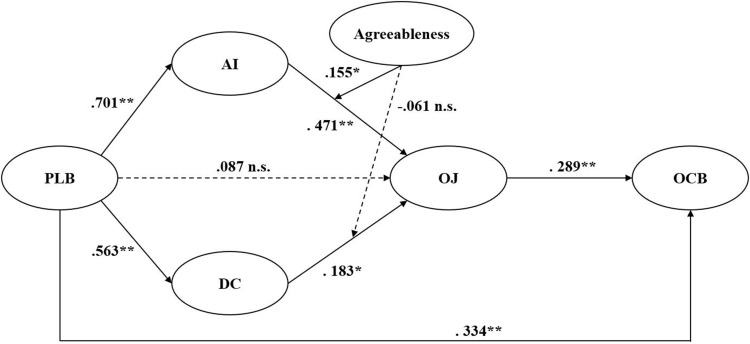

Hypotheses Testing

To examine our hypotheses, a moderated-mediation path analysis based on Hayes’ Process Model was performed in AMOS. As recommended, we employed a bootstrapping analysis with 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals based on 10,000 samples to determine the significance of indirect and conditional effects. The standardized path’s coefficients are shown in Figure 1. The hypothesized path model reported an excellent fit to the data (χ2=6.271, df = 314, χ2/df = 2.727, RMSEA = 0.073, CFI = 0.903, IFI = 0.904), explaining 31.7% of affective interaction variance, 49.1% of discretionary consideration variance, 42.0% of overall justice variance and 29.6% of OCB variance.

Figure 1.

Results of the moderated mediation path model analysis.

Notes: Standardized coefficients were presented. **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05.

Hypothesis 1 assumed that leader’s PLB is positively related to followers perceptions of overall justice. Results indicated that the effect of PLB on perceptions of overall justice (β = 0.496, CI: [0.399, 0.585]) was significantly positive, which provided support for Hypothesis 1.

Hypothesis 2 postulated that two components of followers perceptions of renqing (ie, affective interaction and discretionary consideration) mediate the relationship between PLB and overall justice. The indirect effect was significant (effect = 0.433, CI: [0.317, 0.579]), indicating that Hypothesis 2 was supported.

Hypothesis 3 proposed a series-linking path from PLB to OCB mediated by affective interaction, discretionary consideration, and overall justice. The bootstrapping result indicated a significant indirect effect of PLB on OCB (effect = 0.150, CI: [0.069, 0.239]), thus supporting Hypothesis 3.

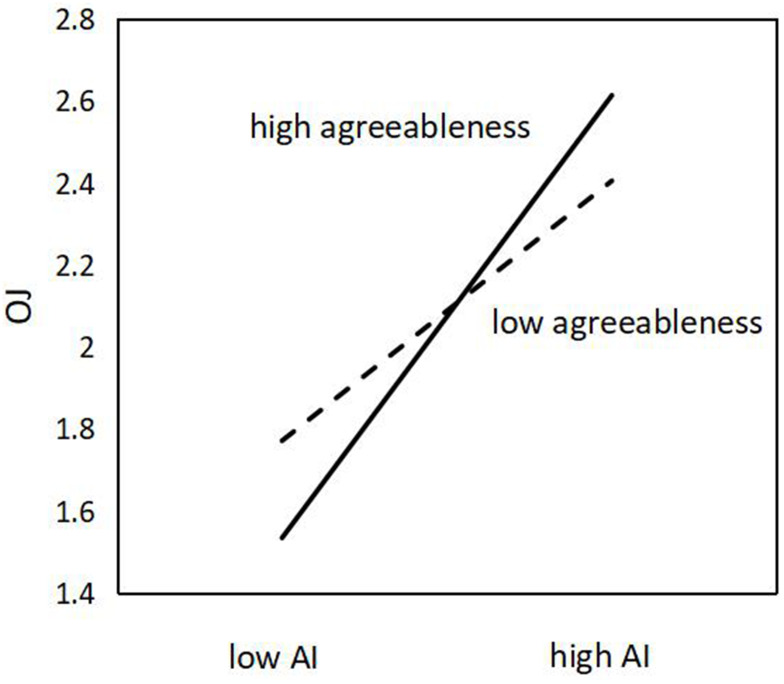

To test hypothesis 4, we constructed the interaction term between centered values of two components of perceptions of renqing and agreeableness, ie, affective interaction × agreeableness and discretionary consideration × agreeableness. The results showed that the interaction term of affective interaction × agreeableness was significant (β = 0.155, CI: [0.014, 0.317]) while that of discretionary consideration × agreeableness was not significant (β = −0.061, CI: [−0.221, 0.086]).

To further explicate this interaction, we followed Aiken and West’s (1991) suggestion to draw separate plots for employees whose scores were one SD below and above the mean of agreeableness.51 Figure 2 shows the interaction effect between affective interaction and agreeableness on overall justice. The relationship between affective interaction and overall justice was positive and significant for the employees endorsing higher trait agreeableness (estimate = 0.583, p = 0.000, CI: [0.396, 0.740]). However, for the employees whose trait agreeableness was low, the relation of affective interaction with overall justice was weakened and still significant (estimate = 0.335, p = 0.015, CI: [0.067, 0.574]). Hence, Hypothesis 4 was supported.

Figure 2.

The interactive effect of AI (affective interaction) and agreeableness on overall justice.

Discussion

The present study proposed and examined a moderated mediation mechanism underlying the effect of PLB on followers overall justice perceptions and OCB. In particular, we found a positive association between PLB and followers perceptions of overall justice, and more importantly, we revealed a mediating path of two components of perceptions of renqing in this association. Additionally, the results also indicated a serial mediating effect of two components of follower perceptions of renqing (ie, affective interaction and discretionary consideration) and perceptions of overall justice linking PLB to OCB. Furthermore, we found that trait agreeableness plays a significant moderating role in the effects of affective interaction on overall justice, but not in that of discretionary consideration on overall justice.

Theoretical Contributions

First, we found a positive association between PLB and followers perceptions of overall justice. This finding is consistent with previous work suggesting that Chinese traditional culture based leadership, eg, paternalistic leadership,15 will positively relate to employees perceptions of overall justice in Chinese organizational settings. Our study is among the first to spotlight the relationship of PLB with perceptions of overall justice, and provides a novel insight into why positive outcomes of PLB are repeatedly found in Chinese workplace by drawing on the theory of uncertainty management.

Second, this study demonstrated that two components of followers perceptions of renqing (ie, affective interaction and discretionary consideration) mediate the relationship between PLB and overall justice. This finding can be explicated by uncertainty management theory.23 Specifically, although PLB, with its “both-and” feature, seems unpredictable and provokes followers feeling of uncertainty, it is particularly in line with Chinese cultural norm of renqing, which in turn facilitates followers perceptions of overall justice. As no previous work was found to examine the process mechanisms underlying the effects of PLB on overall justice, our study addresses this gap in the literature and advances our understanding of the mediating role of two components of perceptions of renqing linking PLB to overall justice in the perspective of uncertainty management theory.

Third, and more importantly, our study identified a serial mediating effect of two components of perceptions of renqing and overall justice in the relationship between PLB and OCB. This finding largely supports the reasoning that uncertainty management theory21,22 would predict, providing the empirical evidence for adopting uncertainty management theory as an overarching framework to account for the positive process mechanism from PLB to two components of perceptions of renqing and overall justice, and to OCB. Our study responds to a strong call made by Duan (2019) in his review of uncertainty management theory to shed light on whether this theory has value and validity to explain organizational phenomena.52

Fourth, we found that followers trait agreeableness strengthens the effects of affective interaction on overall justice, but not that of discretionary consideration on overall justice. In particular, affective interaction features with the prominent behavioral characteristics that follow the renqing norm, including expressing good emotions (eg, respect, trust, and sympathy), caring for others, and providing help.26 Discretionary consideration represents managers flexibility in considering both rational criteria (formal rules) and affective factors (renqing) in making decisions, rather than imposing uniformity in all cases.45 The reason for our findings of the significant and non-significant moderating effect of agreeableness in the relationship of affective interaction and discretionary consideration with overall justice respectively may lie in the fact that agreeable employees, indeed, are more sensitive to interpersonal interactions31 but not to managerial decisions. Our findings suggest ways in which managers can specifically improve agreeable followers perceptions of overall justice.

Practical Implications

Our study has several practical implications. First, the finding of the positive effect of PLB on two components of perceptions of renqing indicates that in order to facilitate followers perceptions of renqing, organizations can implement leadership training programs to improve leaders awareness of the importance of PLB and to strengthen their willingness to conduct PLB in management practices. When promoting employees to be managers, the organizations can purposely select those who with potential characteristics of PLB, such as holistic thinking,17 extraversion and openness.18 Second, given the serial mediation roles of two components of perceptions of renqing and overall justice on the PLB–OCB linkage, enhancing employees perceptions of renqing and then overall justice is an important pathway to improving OCB. Organizations and managers should be aware of the importance of perceptions of renqing, especially for those within collectivist-culture countries. Third, employees with high agreeableness perceive a stronger association between affective interaction and overall justice. Therefore, managers need to first identify their followers trait agreeableness and implement more personnel measures to facilitate their perceptions of affective interaction.

Limitations and Future Directions

This study has several limitations that we need to highlight. First, despite the use of two-wave surveys in collecting data, its correlational design cannot reach conclusions about the causation of the processes. Second, employees were the only data source in this study, which might result in serious CMV. Although our detection of CMV showed that it did not pose a threat to the results, we recommend future research incorporate sufficient measurement periods to separate the times at which antecedents, mediators, and outcomes are assessed using multiple data sources. Third, given that renqing is a typical phenomenon in Chinese society, we explored our research questions using Chinese sample. We suggest that our findings might be observed in other cultural contexts in which interpersonal relationships are highly valued, such as Japan and South Korea.53 We encourage future studies to examine the generalizability of our findings beyond China, and identify the specific effects of renqing in organizational settings.

Conclusions

This study advances the current understandings of the influencing mechanisms between PLB and followers perceptions overall justice and OCB. It is suggested that will facilitate followers perceptions of two components of renqing first, then boost their perceptions of overall justice, which in turn leading to more OCB, especially for those followers who endorse more agreeableness. In particular, the results demonstrate that PLB is positively related to followers perceptions of overall justice and two components of perceptions of renqing significantly mediates this relationship. Moreover, two components of followers perceptions of renqing and overall justice exert a serial mediation effect linking PLB to OCB. More importantly, followers trait agreeableness strengthens the effects of perceptions of affective interaction on overall justice. Given that both PLB and renqing are rooted in Chinese traditional culture and are crucial factors for facilitating employees positive outcomes such as overall justice and OCB, we hope this study could encourage future inquiry into the roles of PLB and renqing via relating them to other variables such as employees task performance and creativity.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Project No.: 71902123), China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (Project No.: 2018M643513), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Project No.: skbsh2019-39), and Postdoctoral Interdisciplinary Research Project of Sichuan University.

Ethical Statement

The present study adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee on Human Experimentation of Sichuan University. All participants received the first-wave questionnaire in an envelope with an introduction of the study purposes as well as a written informed consent form. We explained that this study welcomed voluntary participation, and complied with the principle of confidentiality, and is only for research purposes. Before response to the first-wave questionnaire, all participants provided informed consent, claimed their understandings of the study purposes and they would like to participate in the study voluntarily.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Kim SL, Kim M, Yun S. What do we need for creativity? The interaction of perfectionism and overall justice on creativity. Pers Rev. 2017;46(1):154–167. doi: 10.1108/PR-06-2015-0187 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim T, Leung K. Forming and reacting to overall fairness: a cross-cultural comparison. Organ Behav Hum Dec. 2007;104(1):83–95. doi: 10.1016/j.obhdp.2007.01.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ambrose ML, Schminke M. The role of overall justice judgments in organizational justice research: a test of mediation. J Appl Psychol. 2009;94(2):491–500. doi: 10.1037/a0013203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arnéguy E, Ohana M, Stinglhamber F. Overall justice, perceived organizational support and readiness for change: the moderating role of perceived organizational competence. J Organ Change Manag. 2020;33(5):765–777. doi: 10.1108/JOCM-12-2019-0373 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Soenen G, Eib C, Torrès O. The cost of injustice: overall justice, emotional exhaustion, and performance among entrepreneurs: do founders fare better? Small Bus Econ. 2019;53(2):355–368. doi: 10.1007/s11187-018-0052-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Whiteside DB, Barclay LJ. Echoes of silence: employee silence as a mediator between overall justice and employee outcomes. J Bus Ethics. 2013;2(2):251–266. doi: 10.1007/s10551-012-1467-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Colquitt JA, Zipay KP, Lynch JW, Ryan O. Bringing “The Beholder” center stage: on the propensity to perceive overall fairness. Organ Behav Hum. 2018;148:159–177. doi: 10.1016/j.obhdp.2018.08.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haynie JJ, Svyantek DJ, Mazzei MJ, Varma V. Job insecurity and compensation evaluations: the role of overall justice. Manag Decis. 2016;54(3):630–645. doi: 10.1108/MD-04-2015-0134 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lind EA. Fairness heuristic theory: justice judgments as pivotal cognitions in organizational relations. In: Greenberg J, Cropanzano R, editors. Advances in Organizational Justice. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press; 2001:56–88. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rodell JB, Colquitt JA, Baer MD. Is adhering to justice rules enough? The role of charismatic qualities in perceptions of supervisors’ overall fairness. Organ Behav Hum Dec. 2017;140:14–28. doi: 10.1016/j.obhdp.2017.03.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holtz BC, Harold CM. Fair today, fair tomorrow? A longitudinal investigation of overall justice perceptions. J Appl Psychol. 2009;94(5):1185–1199. doi: 10.1037/a0015900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roeck KD, Marique G, Stinglhamber F, Swaen V. Understanding employees’ responses to corporate social responsibility: mediating roles of overall justice and organizational identification. Int J Hum Resour Man. 2014;25(1):91–112. doi: 10.1080/09585192.2013.781528 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Loi R, Yang J, Diefendorff JM. Four-factor justice and daily job satisfaction: a multilevel investigation. J Appl Psychol. 2009;94(3):770–781. doi: 10.1037/a0015714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Konovsky MA, Pugh DS. Citizenship behavior and social exchange. Acad Manage J. 1994;37:656–669. doi: 10.2307/256704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ren H, Zhong Z, Chen CW, Brewster C. Two-way in-/congruence in three components of paternalistic leadership and subordinate justice: the mediating role of perceptions of renqing. Asian Bus Manag. 2021:1–26. doi: 10.1057/s41291-021-00149-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khattak SI, Jiang Q, Li H, Zhang X. Corporate social responsibility (CSR) and leadership: validation of a multi-factor framework in the United Kingdom (UK). J Bus Econ Manag. 2019;20(4):754–776. doi: 10.3846/jbem.2019.9852 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang Y, Waldman DA, Han YL, Li XB. Paradoxical leader behaviors in people management: antecedents and consequences. Acad Manage J. 2015;58(2):538–566. doi: 10.5465/amj.2012.0995 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ishaq E, Bashir S, Khan AK. Paradoxical leader behaviors: leader personality and follower outcomes. Appl Psychol Int Rev. 2021;70(1):342–357. doi: 10.1111/apps.12233 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang Y, Li Z, Liang L, Zhang X. Why and when paradoxical leader behavior impact employee creativity: thriving at work and psychological safety. Curr Psychol. 2019;40(4):1911. doi: 10.1007/s12144-018-0095-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tripathi N, Miron-Spektor E, Lewis MW. Mixed blessings: dynamic impact of paradoxical leader behavior on subordinate’ engagement and CWB. Academy of Management Annual Meeting Proceedings; 2018:10654. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bos K, Lind EA. Uncertainty management by means of fairness judgments. Adv Exp Soc Psychol. 2002;34:1–60. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2601(02)80003-X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bos KVD, Poortvliet PM, Maas M, Miedema J, Ham EJVD. An enquiry concerning the principles of cultural norms and values: the impact of uncertainty and mortality salience on reactions to violations and bolstering of cultural worldviews. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2005;41(2):91–113. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2004.06.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bos KVD, Lind EA. The social psychology of fairness and the regulation of personal uncertainty. In: Arkin RM, Oleson KC, Carroll PJ, editors. Handbook of the Uncertain Self. New York, NY: Psychology Press; 2010:122–141. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hwang KK. Face and favor: the Chinese power game. Am J Sociol. 1987;92(4):944–974. doi: 10.1086/228588 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leung K, Chen Z, Zhou F, Kai L. The role of relational orientation as measured by face and renqing in innovative behavior in China: an indigenous analysis. Asia Pac J Manag. 2014;31(1):105–126. doi: 10.1007/s10490-011-9277-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang Z, Yang CF. Beyond distributive justice: the reasonableness norm in Chinese reward allocation. Asian J Soc Psychol. 1998;1(3):253–269. doi: 10.1111/1467-839X.00017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhu J, Xu S, Ouyang K, Herst D, Farndale E. Ethical leadership and employee pro-social rule-breaking behavior in China. Asian Bus Manag. 2018;17(1):59–81. doi: 10.1057/s41291-018-0031-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fang T. Yin yang: a new perspective on culture. Manage Organ Rev. 2012;8(1):25–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8784.2011.00221.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Törnroos M, Elovainio M, Hintsa T, et al. Personality traits and perceptions of organisational justice. Int J Psychol. 2019;54(3):414–422. doi: 10.1002/ijop.12472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barrick MR, Mount MK. The big five personality dimensions and job performance: a meta-analysis. Pers Psychol. 1991;44(1):1–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6570.1991.tb00688.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chiaburu DS, Oh IS, Berry CM, Li N, Gardner RG. The five-factor model of personality traits and organizational citizenship behaviors: a meta-analysis. J Appl Psychol. 2011;96(6):1140–1166. doi: 10.1037/a0024004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen ZJ, Davison RM, Mao JY, Wang ZH. When and how authoritarian leadership and leader renqing orientation influence tacit knowledge sharing intentions. Inf Manag. 2018;55(7):840–849. doi: 10.1016/j.im.2018.03.011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huertas-Valdivia I, Gallego-Burín AR, Lloréns-Montes FJ. Effects of different leadership styles on hospitality workers. Tourism Manage. 2019;71:402–420. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2018.10.027 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.She Z, Li Q, Yang B, Yang B. Paradoxical leadership and hospitality employees’ service performance: the role of leader identification and need for cognitive closure. Int J Hosp Manag. 2020;89:102524. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102524 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shao Y, Nijstad BA, Täuber S. Creativity under workload pressure and integrative complexity: the double-edged sword of paradoxical leadership. Organ Behav Hum Dec. 2019;155:7–19. doi: 10.1016/j.obhdp.2019.01.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yen DA, Abosag I, Huang YA, Nguyen B. Guanxi GRX (ganqing, renqing, xinren) and conflict management in sino-US business relationships. Ind Market Manag. 2017;66:103–114. doi: 10.1016/j.indmarman.2017.07.011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Organ DW. Organizational Citizenship Behavior: The Good Soldier Syndrome. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee K, Allen NJ. Organizational citizenship behavior and workplace deviance: the role of affect and cognitions. J Appl Psychol. 2002;87(1):131–142. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.87.1.131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Podsakoff PM, Mackenzie SB, Lee JY, Podsakoff NP. Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol. 2003;88(5):879–903. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen X, Eberly MB, Chiang T, Farh J, Cheng B. Affective trust in Chinese leaders: linking paternalistic leadership to employee performance. J Manage. 2014;40(3):796–819. doi: 10.1177/0149206311410604 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brislin RW. The wording and translation of research instrument. In: Lonner W, Berry J, editors. Field Methods in Cross-Cultural Research. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage; 1986:137–164. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Donnellan MB, Oswald FL, Baird BM, Lucas RE. The mini-ipip scales: tiny-yet-effective measures of the big five factors of personality. Psychol Assess. 2006;18(2):192–203. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.18.2.192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Goldberg LR. A broad-bandwidth, public-domain, personality inventory measuring the lower-level facets of several five-factor models. In: Mervielde I, Deary IJ, De Fruyt F, Ostendorf F, editors. Personality Psychology in Europe. Tilburg, The Netherlands: Tilburg University Press; 1999:7–28. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nunnally J. Psychometric Methods. New York: McGraw Hill; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ren H, Chen CW, Chen Y. Between culture and satisfaction: mediating roles of perceptions of renqing and rules. Asia Pac J Hum Resour. 2020. doi: 10.1111/1744-7941.12256 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu Y, Yin X, Li S, Zhou X, Zhu R, Zhang F. The relationship between employee’s status perception and organizational citizenship behaviors: a psychological path of work vitality. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2021;14:743–757. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S307664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Carlson KD, Wu J. The illusion of statistical control: control variable practice in management research. Organ Res Methods. 2012;15(3):413–435. doi: 10.1177/1094428111428817 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nasser-Abu Alhija F, Wisenbaker J, Monte A. Carlo study investigating the impact of item parceling strategies on parameter estimates and their standard errors in CFA. Struct Equ Modeling. 2006;13(2):204–228. doi: 10.1207/s15328007sem1302_3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ding H, Yu E. Followers’ strengths-based leadership and strengths use of followers: the roles of trait emotional intelligence and role overload. Pers Indiv Differ. 2020;168:110300. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2020.110300 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hair JF, Black WC, Babin BJ, Anderson RE. Multivariate Data Analysis. 7th ed. Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: testing and interpreting interactions. Eval Pract. 1991;14(2):167–168. doi: 10.1057/jors.1994.16 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Duan J. Uncertainty management theory. In: Li C, Xu S, editors. Management and Organization Theories. Peking: Peking University Press; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Horak S, Taube M. Same but different? Similarities and fundamental differences of informal social networks in China (guanxi) and Korea (yongo). Asia Pac J Manag. 2016;33(3):595–616. doi: 10.1007/s10490-015-9452-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]