Abstract

Purpose:

Pediatric cystic fibrosis (CF) patients have a variable onset, severity, and progression of sinonasal disease. The objective of this study was to identify genotypic and phenotypic factors associated with CF that are predictive of sinonasal disease, recurrent nasal polyposis, and failure to respond to standard treatment.

Methods:

A retrospective case series was conducted of 30 pediatric patients with CF chronic rhinosinusitis with and without polyps. Patient specific mutations were divided by class and categorized into high risk (Class I-III) and low risk (Class IV-V). Severity of pulmonary and pancreatic manifestations of CF, number of sinus surgeries, nasal polyposis and recurrence, age at presentation to Otolaryngology, and Pediatric Sinonasal Symptom Survey (SN-5)/Sinonasal Outcome Test (SNOT-22) scores were examined.

Results:

27/30 patients (90%) had high risk mutations (Class I-III). 21/30 (70.0%) patients had nasal polyposis and 10/30 (33.3%) had recurrent nasal polyposis. Dependence on pancreatic enzymes (23/27, 85.2% vs 0/3, 0.0%, p=0.009) and worse forced expiratory volumes (FEV1%) (mean 79, SD 15 vs mean 105, SD 12, p=0.009) were more common in patients with high risk mutations. Insulin-dependence was more common in those with recurrent polyposis (5/10, 50% vs 2/20, 10%, p=0.026). There was no statistical difference in ages at presentation, first polyps, or sinus surgery, or in polyposis presence, recurrence, or extent of sinus surgery based on high risk vs. low risk classification.

Conclusion:

CF-related diabetes was associated with nasal polyposis recurrence. Patients with more severe extra-pulmonary manifestations of CF may also be at increased risk of sinonasal disease.

Keywords: Cystic Fibrosis, Chronic Sinusitis, FESS, Forced Expiratory Volumes, Mutation, Pancreatic Function, Paranasal Sinus Disease, Pediatric Rhinology, Polyp, Sinonasal Disease Outcomes

1. Introduction

Cystic Fibrosis (CF) is an autosomal recessive disorder with multi-organ dysfunction [1]. Although the classic symptoms include respiratory tract and gastrointestinal disease, a large number of patients with CF have sinonasal dysfunction as well [2]. Chronic Rhinosinusitis (CRS) affects the CF population roughly four times more commonly than the general population [3]. Some have hypothesized that impaired mucociliary clearance may increase the risk of chronic rhinosinusitis, nasal polyposis, and sinonasal disease in general [4]. CF is characterized by both genetic and clinical heterogeneity and there is poor correlation between genotype and phenotypic expression. Mutations have generally been classified based on the mechanism by which they disrupt the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) protein [5]. Patients who have Class I mutations have defective synthesis of CFTR; those with Class II mutations, including F508del, have impaired processing of CFTR; those with class III mutations have reduced channel opening time of CFTR protein; those with Class IV mutations have impaired conductance of the CFTR channel; and those with Class V mutations have poor synthesis and stability of the CFTR protein [6]. The mutations can be further classified into “high” and “low” risk; patients fall into the “high” risk mutation category when they have two mutations from Class I-III. These patients typically have more severe global disease manifestation. Patients with “low” risk genotypes include those with at least one mutation in Class IV-V, and they typically have milder and later onset presentation of disease [7].

Several studies in the adult literature seem to indicate that nasal polyposis and sinonasal symptoms in general are more severe in patients with high risk mutations, including homozygous F508del [8,9]. Pediatric CF patients have a variable onset, severity, and progression of sinonasal disease. To our knowledge, Do et al has been the only group to investigate the effects of genotype on endoscopic sinus surgery outcomes [10]. By primarily using the endpoints of age of first intervention, Lund-Mackay score, extent of surgery score, and length of hospitalization, they found little difference between patients who were homozygous versus heterozygous for F508del. Given the phenotypic variability of CF, even among patients with similar genotype, we chose to investigate both genotypic and phenotypic predictors of sinonasal disease in the pediatric CF population. The goal of this study was to evaluate phenotypic expression of CF (i.e. respiratory, pancreatic, and gastrointestinal dysfunction) and sinonasal manifestations of CF. We aimed to identify genotype and phenotypic factors associated with CF that are predictive of early onset sinonasal disease, recurrent nasal polyposis, and failure to respond to standard medical and surgical management.

2. Methods

An Institutional Review Board approved (STUDY# 19080188) retrospective case series was conducted of 30 patients with CF seen in the otolaryngology clinic of a tertiary care children’s hospital with a Cystic Fibrosis Center of Care designation by the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. Demographics (age at presentation to Otolaryngology and sex), sinus history (age at adenoidectomy and sinus surgery, sinuses entered during surgery, and presence or absence of polyps during flexible fiberoptic nasoendoscopy in clinic or in the operating room), lowest forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) at any hospital visit, pancreatic function (using pancreatic enzymes or insulin), asthma diagnosis, and follow-up (time from first to last Otolaryngology visit) were recorded from the electronic medical record. Patients were considered to have recurrent polyposis if polyps returned after surgical removal. In addition, patient specific mutations were extracted from the electronic medical record and were divided by class and categorized into high risk (Class I-III) and low risk (Class IV-V) (Table 1). Preoperative Pediatric Sinonasal Symptom Survey (SN-5) and Sinonasal Outcome Test (SNOT-22) scores were obtained in 7 and 6 patients, respectively, as part of a separate, ongoing study. Briefly, the patient’s parent completed the SN-5 for patients ≤ 5 years old and patients > 5 years old completed the SNOT-22 [11–13]. The maximum scores for the SN-5 and SNOT-22 are 7 and 110, respectively, with greater scores indicating more sinonasal symptoms.

Table 1.

Mutations Identified and Classifications

| High risk | Class | n |

|---|---|---|

| F508del / F508del | IIa | 15 |

| F508del / W1282X | IIa | 3 |

| F508del / E585X | IIb | 1 |

| F508del / N1303K | IIa | 1 |

| F508del / R553X | IIa | 1 |

| F508del / unknown | IIa | 1 |

| 2183AA>G / CFTRdel2,3 | IIc | 1 |

| 3659delC / V520F | IIIa | 1 |

| G542X / G551D | IIIa | 1 |

| N1303K / I507del | IIa | 1 |

| N1303K / L1077P | IIId | 1 |

| Low risk | Class | n |

| F508del / R117H | IVa | 1 |

| F508del / R334W | IVa | 1 |

| R553X / 3849+10kbC>T | Va | 1 |

References utilized to determine mutation class:

2.1. Statistics

Patients were grouped as having 1) a high risk or low risk mutation, 2) polyps or no polyps, and 3) recurrent polyposis or no recurrent polyposis. Categorical characteristics (sex; pancreatic enzyme use; insulin dependence; asthma; history of adenoidectomy, nasal polyps, or sinus surgery; and most distal sinus entered during initial sinus surgery) were summarized as n (%) and compared between these groups using Fisher’s exact test. Continuous data were evaluated for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Normally distributed data (Shapiro-Wilk p>0.05) were summarized as mean (standard deviation, SD) and compared between groups using Student’s t-tests. Non-normally distributed data (Shapiro-Wilk p<0.05) were compared between groups using Wilcoxon rank-sum tests. The time until first sinus surgery was evaluated using log-rank tests. All comparisons were performed using Stata/SE 16.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX) except for the log-rank tests, which were conducted using GraphPad Prism 7.02 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). p<0.05 was considered significant.

3. Results

3.1. Demographics and Patient Characteristics

Demographic characteristics of the 30 included patients are summarized in Table 2. Fifteen patients (15.0%) were male, and mean age at presentation to Otolaryngology was 10.3 years (SD: 5.5 years). Twenty-three patients were on pancreatic enzymes (76.7%), 7/30 (23.3%) were insulin-dependent, 13/30 (43.3%) had asthma, and mean lowest FEV1 was 82.0% (SD: 17.0%). Regarding otolaryngologic history, 9/30 (30.0%) patients had undergone adenoidectomy and 21/30 (70.0%) had nasal polyps. Polyps were first observed at a mean age of 10.9 years (SD: 5.5 years). Twenty-four (80.0%) underwent sinus surgery at a mean age of 11.2 years (SD: 5.1 years). Ten (33.3%) had more than 1 sinus surgery, and in these patients, the median time from first to second sinus surgery was 14.7 months (range 5.0–94.0 months). The maxillary, ethmoid, sphenoid, and frontal sinuses were all opened during 12/24 (50.0%) of initial sinus surgeries, and polyps were observed in 18/24 (75.0%) of these surgeries. Ten out of thirty (33.3%) had recurrence of polyposis. In the 7 patients with pre-operative SN-5 and 6 with SNOT-22, mean scores were 4.3 (SD: 0.8) and 22.7 (SD: 11.0), respectively. Mean follow-up was 13.8 months (SD: 4.7 months).

Table 2.

Demographics (N=30)

| Characteristic | n | % |

| Homozygous (F508del/F508del) | 15 | 50.0 |

| Lesser Mutation Class | ||

| II | 24 | 80.0 |

| III | 3 | 10.0 |

| IV | 2 | 6.7 |

| V | 1 | 3.3 |

| Male | 15 | 50.0 |

| On Pancreatic Enzymes | 23 | 76.7 |

| Insulin Dependent | 7 | 23.3 |

| Asthma | 13 | 43.3 |

| Adenoidectomy | 9 | 30.0 |

| Nasal Polyps | 21 | 70.0 |

| Sinus Surgery | 24 | 80.0 |

| Extent of First Sinus Surgery (n=24) | ||

| Maxillary | 1 | 4.2 |

| Ethmoid | 5 | 20.8 |

| Sphenoid | 6 | 25.0 |

| Frontal | 12 | 50.0 |

| Polyps at First Surgery (n=24) | 18 | 75.0 |

| Recurrent Nasal Polyposis | 10 | 33.3 |

| Multiple Sinus Surgeries | 10 | 33.3 |

| mean | SD | |

| Years of Age at Presentation | 10.3 | 5.5 |

| Years of Age at First Polyps (n=19) | 10.9 | 5.5 |

| Years of Age at First Sinus Surgery (n=24) | 11.2 | 5.1 |

| Lowest FEV1% (n=28) | 82.0 | 17.0 |

| Pre-Op SN 5 (n=7) | 4.3 | 0.8 |

| Pre-Op SNOT 22 (n=6) | 22.7 | 11.0 |

| Years of Follow-Up | 13.8 | 4.7 |

| median | range | |

| Months to Second Sinus Surgery (n=10) | 15.3 | 5.0–94.0 |

Abbreviations: FEV1: forced expiratory volume in one second; SN 5: Pediatric Sinonasal Symptom Survey; SNOT 22: Sinonasal Outcome Test

3.2. High Risk vs. Low Risk Mutations

Dependence on pancreatic enzymes (23/27, 85.2% vs. 0/3, 0.0%, χ2(1)=11.0, p=0.009) (Figure 1) and worse forced expiratory volumes (FEV1%) (mean 79, SD 15 vs. mean 105, SD 12, t(26)=2.85, p=0.009) were more common in patients with high risk mutations. However, there were no significant differences in polyp presence, recurrence, undergoing adenoidectomy or sinus surgery (Figure 1), extent of sinus surgery, or time until first sinus surgery based on high risk vs. low risk classification.

Figure 1.

Characteristics of patients with high risk and low risk mutations. Dependence on pancreatic enzymes was more common in patients with high risk mutations. *p=0.009

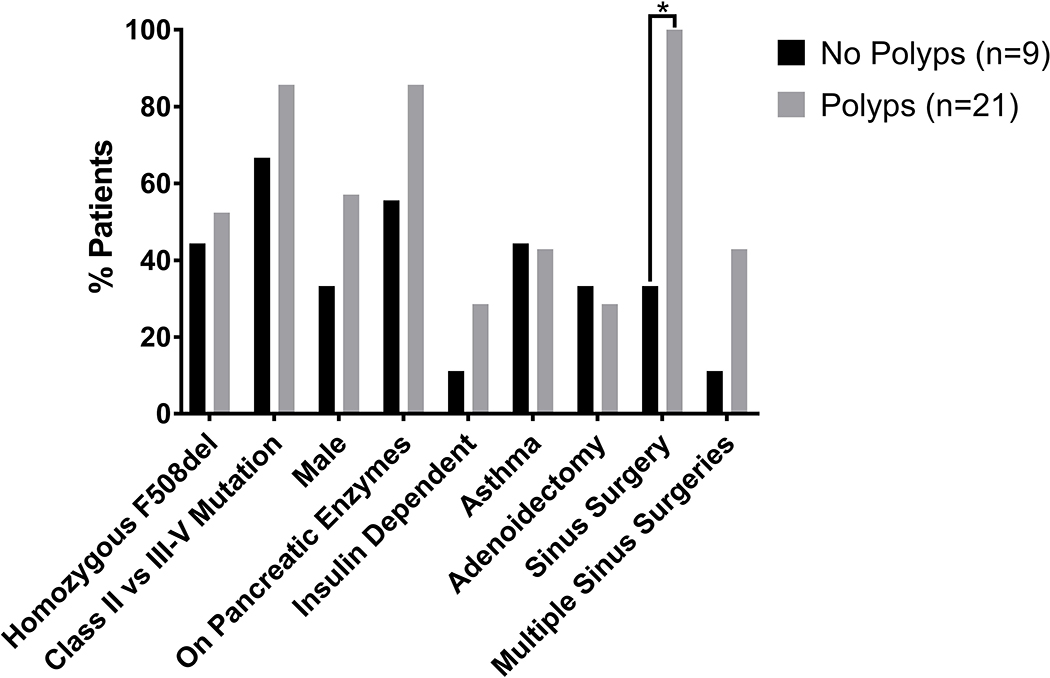

3.3. Polyposis

All 21 patients with nasal polyps underwent sinus surgery compared with 3 (33.3%) of those without nasal polyps (χ2(1)=17.5, p<0.001). None of the other factors examined, including homozygous F508del vs other mutations, high risk vs. low risk mutations, sex, receipt of pancreatic enzymes, insulin-dependence, asthma, adenoidectomy, or undergoing multiple sinus surgeries were significantly associated with polyposis in general (Figure 2). As expected, undergoing more than 1 sinus surgery was more common in patients with recurrent polyposis than in those without recurrent polyposis (7/10, 70.0% vs. 3/20, 15.0%, χ2(1)=9.08, p=0.005). Interestingly, insulin-dependence was more common in those with recurrent polyposis (5/10, 50% vs 2/20, 10%, χ2(1)=5.96, p=0.026) (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Characteristics of patients with polyps and no polyps. Sinus surgery was more common in patients with polyps. *p<0.001

Figure 3.

Characteristics of patients with recurrent polyposis and no recurrent polyposis. Insulin-dependence and multiple sinus surgeries were more common in patients with recurrent polyps. *p<0.05

4. Discussion

Coordinated multidisciplinary care for the CF patient has dramatically improved outcomes over the past several decades [14]. Pulmonary and endocrinology specialists have classically been most involved with CF patients, as manifestations in these organ systems may have dire and even fatal consequences. While sinonasal manifestations are not often life threatening, they contribute to increased inpatient admissions and morbidity [11].

This retrospective cohort analysis relied on pediatric CF patients seeking care in the Otolaryngologist office, yielding 30 patients over a 4-year period. A majority of patients (>70%) unsurprisingly had pancreatic deficiency requiring dependence on supplemental enzymes. Our cohort was skewed given the reason for inclusion in our study, namely that our patients had a diagnosis of CF and a reason to be in an Otolaryngology office, but nonetheless 24/30 (80%) required sinus surgery with or without adenoidectomy, and 10/30 (30%) required adenoidectomy alone. The SNOT-22 [13] and SN-5 [11] are 22 and 5 question evaluations used to help determine the severity of sinonasal symptoms in patients with Chronic Rhinosinusitis. Those who did undergo preoperative questionnaires generally fell into the mild-moderate disease range based on a mean of 22 on the SNOT-22 [13].

In general, dependence on pancreatic enzymes and worse forced expiratory volumes (FEV1%) were more common in patients with high risk mutations. There was no statistical difference in presence of nasal polyps, recurrence of nasal polyps, or extent of sinus surgery based on high risk vs. low risk classification.

Patients with more severe extrapulmonary disease as evidenced by the need for insulin were more likely to have recurrent polyposis (5/10, 50% vs 2/20, 10%, p=0.026). While not statistically significant, over 80% of patients who had nasal polyps were also on pancreatic enzymes, whereas only 55% of patients without nasal polyps were on pancreatic enzymes. One of the limitations of our study was the lack of diversity with regards to high and low risk mutations. A vast majority of our patients (27/30, 90%) had high risk mutations while only 3/30 (10%) had low risk mutations. This limited our ability to compare the two groups. While we would have preferred a more diverse group of genotypes, it is expected that most patients with sinonasal complaints have high risk mutations. Some patients with low risk mutations may have mild, undiagnosed sinonasal disease. Outreach to these patients and further analysis of their sinonasal phenotypic manifestations should be conducted. Another significant limitation in this study was the lack of prospective and longitudinal objective measures of sinus disease. Only 13/30 patients (43.3%) underwent preoperative SNOT-5 or SNOT-22 scoring. Future studies should include preoperative and postoperative objective measures to better quantify the amount of improvement patients with various CF mutations may get from sinus surgery.

5. Conclusion

Patients with more severe extrapulmonary manifestations of CF, including insulin dependence and need for pancreatic enzymes, had increased rates of sinonasal disease, especially in the form of recurrent nasal polyposis. Patients with more severe extrapulmonary manifestations of CF should be considered for additional screening by an Otolaryngologist. While there was no significant difference in our markers of sinonasal disease between high and low risk mutations, further studies should be conducted with broader diversity of genotype and phenotype in order to further elucidate the relationship between class of mutation and severity of sinonasal disease.

Highlights.

CF-related diabetes was associated with nasal polyposis recurrence.

High risk mutations were not associated with worse sinonasal disease.

Sinonasal disease may correlate with more severe extra-pulmonary symptoms of CF.

Funding:

The project described was supported by the National Institutes of Health through Grant Number UL1 TR001857

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration Of Conflicting Interests

ADS and ALS receive some salary support from the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation and National Institutes of Health. However, this is unrelated to the work described, and the authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- [1].Tizzano EF, Buchwald M. CFTR expression and organ damage in cystic fibrosis. Annals Intern Med 1995; 123(4):305–8. 10.7326/0003-4819-123-4-199508150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Robertson JM, Friedman EM, Rubin BK. Nasal and sinus disease in cystic fibrosis. Paediatri Respir. Rev 9 2008;3:213–9. 10.1016/j.prrv.2008.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Halawi AM, Smith SS, Chandra RK. Chronic Rhinosinusitis: Epidemiology and cost. Allergy Asthma Proc 2013;34:328–34. 10.2500/aap.2013.34.3675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Sakano E, Ribeiro AF, Barth L, Condino Neto A, Ribeiro JD. Nasal and paranasal sinus endoscopy, computed tomography, and microbiology of upper airways and the correlations with genotype and severity of cystic fibrosis. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2007;71(1):41–50. 10.1016/j.ijporl.2006.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Bombieri C, Seia M, Catellani C. Genotypes and phenotypes in cystic fibrosis and cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator-related disorders. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2015;36:180–93. 10.1055/s-0035-1547318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Catellani C, Assael BM. Cystic Fibrosis: a clinical view. Cell Mol Life Sci 2017;74:129–40. 10.1007/s00018-016-2393-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Ferril GR, Nick JA, Getz AE, Barham HP, Saavedra MT, Taylor-Cousar JL, et al. Comparison of radiographic and clinical characteristics of low-risk and high-risk cystic fibrosis genotypes. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol 2014;4:915–20. 10.1002/alr.21412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Jorissen MB, De Boeck K, Cuppens H. Genotype-phenotype correlations for the paranasal sinuses in cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1999;159:1412–6. 10.1164/ajrccm.159.5.9712056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Abuzeid WM, Song C, Fastenberg JH, Fang CH, Ayou b N, Jerschow E, et al. Correlations between cystic fibrosis genotype and sinus disease severity in chronic rhinosinusitis. Laryngoscope 2018;128:1752–1758. 10.1002/lary.27019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Do BAJ, Lands LC, Saint-Martin C, Mascarella MA, Manoukian JJ, Daniel SJ, et al. Effect of the F508del genotype on outcomes of endoscopic sinus surgery in children with cystic fibrosis. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2014;78:1133–7. 10.1016/j.ijporl.2014.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Kay DJ, Rosenfeld RM. Quality of life for children with persistent sinonasal symptoms. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;128(1):17–26. 10.1067/mhn.2003.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Banglawala SM, Schlosser RJ, Morella K, Chandra R, Khetani J, Poetker DM, et al. Qualitative development of the sinus control test: a survey evaluating sinus symptom control. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2016; 6:491–9. 10.1002/alr.21690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Farhood Z, Schlosser RJ, Pearse ME, Storck KA, Nguyen SA, Soler ZM. Twenty-two–item Sino-Nasal Outcome Test in a control population: a cross-sectional study and systematic review. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2016;6:271–7. 10.1002/alr.21668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].MacKenzie T, Gifford AH, Sabadosa KA, Quinton HB, Knapp EA, Goss CH, et al. Longevity of patients with cystic fibrosis in 2000 to 2010 and beyond: survival analysis of the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation patient registry. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(4):233–1. 10.7326/M13-0636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Fanen P, Wohlhuter-Haddad A, Hinzpeter A. Genetics of cystic fibrosis: CFTR mutation classifications toward genotype-based CF therapies. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2014;52:94–102. 10.1016/j.biocel.2014.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Terzic M, Jakimovska M, Fustik S, Jakovska T, Sukarova-Stefanovsa E, Plaseska-Karanfilska D. Cystic Fibrosis Mutation Spectrum in North Macedonia: A Step Toward Personalized Therapy. Balkan J Med Genet. 2019;22(1):35–40. 10.2478/bjmg-2019-0009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Shahin WA, Mehaney DA, El-Falaki MM. Mutation spectrum of Egyptian children with cystic fibrosis. Springerplus. 2016;5(1):686. 10.1186/s40064-016-2338-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Bozon D, Zielenski J, Rininsland F, Tsui LC. Identification of four new mutations in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator gene: I148T, L1077P, Y1092X, 2183AA → G. Hum Mutat. 1994;3:330–2. 10.1002/humu.1380030329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]