Abstract

Domestic violence is known to be one of the most prevalent forms of gender-based violence in emergency contexts and anecdotal data during the COVID-19 pandemic suggest that related restrictions on movement may exacerbate such violence. As such, the purpose of this study was to measure differences in domestic violence incident reports from police data in Atlanta, Georgia, before and during COVID-19. Thirty weeks of crime data were collected from the Atlanta Police Department (APD) in an effort to compare Part I offense trends 2018–2020. Compared with weeks 1–31 of 2018 and 2019, there was a growth in Part I domestic crimes during 2020 as reported to the APD. In addition, trendlines show that 2020 domestic crimes were occurring at a relatively similar pace as the counts observed in previous years leading up to the pandemic. A spike in domestic crimes was recorded after city and statewide shelter-in-place orders. The rise of cumulative counts of domestic crimes during the COVID-19 period of 2020 compared with the previous 2 years suggests increased occurrence of domestic violence. The co-occurring pandemics of COVID-19 and domestic violence come amidst a period of racial justice reckoning in the United States; both have a disproportionate impact on Black, Indigenous, and People of Color. As the country grapples with how to deal with health and safety concerns related to the pandemic, and the unacceptable harms being perpetrated by police, a public health approach is strongly warranted to address both universal health care and violence prevention.

Keywords: domestic violence, intimate partner violence, COVID, violence against women, police, crime

Introduction

Intimate partner violence (IPV), including physical, sexual, and psychological abuse by a past or current intimate partner [World Health Organization (WHO) 2012], is a “shadow pandemic” that has both preceded and paralleled the global COVID-19 pandemic (Mlambo-Ngcuka 2020; Moreira and Pinto de Costa 2020). One of the most pervasive human rights violations in the world, before COVID-19, one in three women and girls were victimized by an abusive partner during their lifetime (García-Moreno et al. 2013).

IPV is known to be one of the most prevalent forms of gender-based violence in emergency contexts (Stark and Ager 2011); increases in violence, including IPV are a manifestation of existing gender inequities exacerbated by the cascading impacts of emergencies (John et al. 2020). During the 2014–2016 Ebola Virus Disease epidemic in West Africa—which included strict quarantine measures—widespread increases in IPV were observed (Onyango et al. 2019). Studies of the impact of Hurricane Katrina found increased rates of IPV after the natural disaster; rates of violence against women rose from 4.6 cases per 100,000 per day to >16 cases per 100,000 per day among those displaced by the storm (Bell and Folkerth 2016). Based on both existing literature and emerging evidence, there is reason to believe that COVID-19 will follow this pattern of increased violence.

Data from earlier emergencies and anecdotal data during the pandemic suggest that COVID-19-related restrictions on movement may exacerbate IPV. Early in the pandemic, countries hard hit by COVID-19 began raising the alarm bell about the impacts of the disease on IPV occurrence. France saw a 36% increase in the number of reported IPV cases (Godin 2020; Strianese 2020). Police in China reported that 90% of the causes of recent IPV cases could be attributed to the pandemic (Wanqing 2020). An online survey of 15,000 Australian women found that 65.4% of women who experienced IPV during the pandemic experienced violence for the first time, or observed an escalation in the intensity or frequency of violence relative to earlier experiences, supporting the notion of emergencies exacerbating underlying vulnerabilities and inequities (Boxall et al. 2020). Increased economic strain and diminished health care capacity to support survivors are among the potential reasons for such dramatic effects.

Before COVID-19, nearly 20 people every minute in the United States were physically abused by an intimate partner (Black et al. 2011). Early concerns about increases in IPV during the pandemic have prompted mental health organizations to issue statements outlining the potential impacts of COVID-19 on IPV [Abramson 2020; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) 2020]. These concerns have proven to be well founded as early reporting indicated significant increases in calls to police and domestic violence hotlines (Bosman 2020; Crombie 2020).

In Georgia—even before the onset of shelter-in-place regulations—there was a 79% increase in domestic violence cases in comparison with the previous year, suggesting that individuals were experiencing significant impacts early in the outbreak (Burns 2020). Georgia is notable because it was the first US state to “re-open” (Jarvie 2020); although the state did not experience a COVID-19 case spike initially by August 2020 it was among a number of states where both COVID-19 cases and deaths were increasing—and at numbers significantly higher than they had been during movement restrictions (New York Times 2020).

As concerns about the “shadow pandemic” mount and as COVID-19 cases continue, the need for additional data on the impacts of COVID-19 on IPV are apparent (Emezue 2020; UN Women 2020). In the absence of real-time IPV-related data, domestic crime data serve as the best available proxy measure. The purpose of this study was to measure differences in domestic violence incident reports from police data in Atlanta, Georgia, before and during COVID-19.

Materials and Methods

Setting

Before the pandemic Georgia ranked 10th in the nation for the rate at which women were killed by men; the state's certified domestic violence agencies answered 52,282 crisis calls in 2019; yet, over 4,700 women and their children were turned away from shelters owing to lack of space demonstrating the significant health need for Georgians even before COVID-19 [Georgia Commission on Family Violence (GCFV) 2020; Violence Policy Center (VPC) 2019].

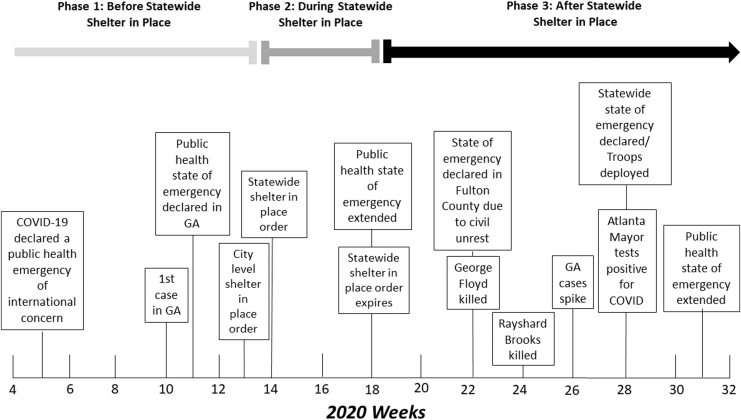

Georgia instituted a mandatory shelter–in-place order one month after the first known COVID-19 case in the state (Fig. 1). The statewide shelter in place was lifted on May 1, 2020 despite continuing infections, although high-risk individuals were urged to continue sheltering in place (Raymond 2020). In addition to the COVID-19 pandemic, widespread civil unrest and protests followed the murder of George Floyd including several high-profile events in Atlanta in late May and early June (Fausset and Levenson 2020; Macaya and Hayes 2020). The murder of Rayshard Brooks by an Atlanta Police officer shortly thereafter escalated tensions between civil society and municipal authorities (Wall Street Journal 2020).

FIG. 1.

Timeline of COVID-19 and racial unrest in Georgia.

Data source

The Atlanta Police Department (APD) is one of the few that provide open source crime data that are regularly updated. Part I offense data are released for public use based on all incidents stored in the APD electronic Integrated Compliance Information System (ICIS) Case Management and available through the APD Open Data portal. The APD Open Data portal can be queried by current day or the prior day for an HTML list of incidents. Historical data from 2009 to 2019 can also be downloaded as a comma delimited (.csv) file. The APD feeds these data into the LexisNexis Community Crime Map for the public to filter and plot with basic analytical tools. Preliminary testing of crime patterns during the pandemic using the mapping dashboard suggested further analysis were warranted.

Through a separate portal, select year-to-date 2020 incident-level data can be extracted, lagging a maximum of 2 weeks from the current date. These data are based on APD crime incidents and are posted by the APD Weekly Crime Reports. PDFs with management stats include aggregate totals by week on common crimes of concern and arrests. None of the aforementioned formats, however, include domestic crime counts.

Measures

Part I crime types are defined by the Federal Bureau of Investigation's (FBI) Uniform Crime Reports (UCR) (U.S. Department of Justice, n.d.). If multiple crimes occur during the same event, the incident is captured using the “hierarchy rule,” which ranks Part I crimes from most to least serious as follows: homicide, manslaughter, rape, robbery, assault, burglary, larceny-theft, motor vehicle theft, and arson (U.S. Department of Justice 2011). APD offense definitions follow the standards set by the FBI with the exception of arson, which is excluded from the APD data as Part I offense. The incident-level data for Atlanta include only the most serious offense occurring during the episode (i.e., APD offense id#). This differs from the FBI's UCR program data, which are recorded by victim allowing for multiple crimes to be included within a single report.

Domestic crimes are as subset of Part I crimes—most often appearing as a subcategory of assault but also as a subset of other serious crimes such as homicide. Domestic crimes can include nonpartner relationships, such as family violence and child abuse. Therefore, our measure is broader than IPV, but inclusive of it. Because crime data routinely uses the term domestic crimes, we use the term domestic violence instead of the term IPV when making reference to the data used here and reserve use of the term IPV for references to the larger literature on this topic.

Study ethics

The study was reviewed by the Emory University Institutional Review Board and deemed exempt from review based on the nature of the secondary analysis of de-identified data.

Data collection and management

Crime data were collected on August 10, 2020 from the APD Open Data Portal historical repository to capture 2018–2019 incidents; the Crime Data Downloads portal was queried to gather 2020 year-to-date incidents [Atlanta Police Department (APD) 2020]. The historical dataset and 2020 data can be queried by month, year, and crime type among other attributes, all of which were extracted. The raw data files were imported to SPSS, and then merged into an original incident-level dataset. Measures for analyses were coded into week-level measures by study year, 2018–2020. Six cumulative crime counts were calculated summing Part I and domestic crimes reported within the same 7 days for each year (i.e., week total plus all prior week totals). Two measures of the 2020 percent change in Part I and domestic crimes were computed by taking the difference in the most recent incident counts from the year before, then using the prior year total as the denominator or expected baseline (i.e., 2020 # − 2019 #/2019 #). Three per capita crime rate measures were set to equal the cumulative count multiplied per standard unit of residents over the estimated yearly population (e.g., 2020 rate = weekly aggregate # × 100,000/2020 population). Population estimates were retrieved from the United States Census Bureau. Finally, the complete dataset was exported to Microsoft Excel software for data visualization in analyses.

Data analysis

Crime data were examined for changes in Atlanta domestic crimes before and during the pandemic. First, we questioned whether domestic crimes had increased in 2020 compared with prior years and if so, whether the timing aligned with the issuance of city and/or state-level shelter-in-place orders. Graphing the cumulative counts allowed us to model yearly trendlines through August 1, 2020 and assess the sharpness of their divergence across years. Second, we questioned how much domestic crimes had changed from the year prior and if the observed change was simply reflective of the general crime trends in the city. A layer bar chart was generated using percent change computations for all Part I and domestic crimes to explore the variance in the subset of incidents within the broader crime context. Third, we questioned if the observed changes in domestic crime patterns were reflective of population changes over time. We explored this by tabulating the domestic crime counts normalized to the city population as a rate per 100,000 residents and crosswalking the rows. These analyses permitted us to examine the fluctuations and intensity of domestic crimes while accounting for population size across years—an apples-to-apples comparison.

Results

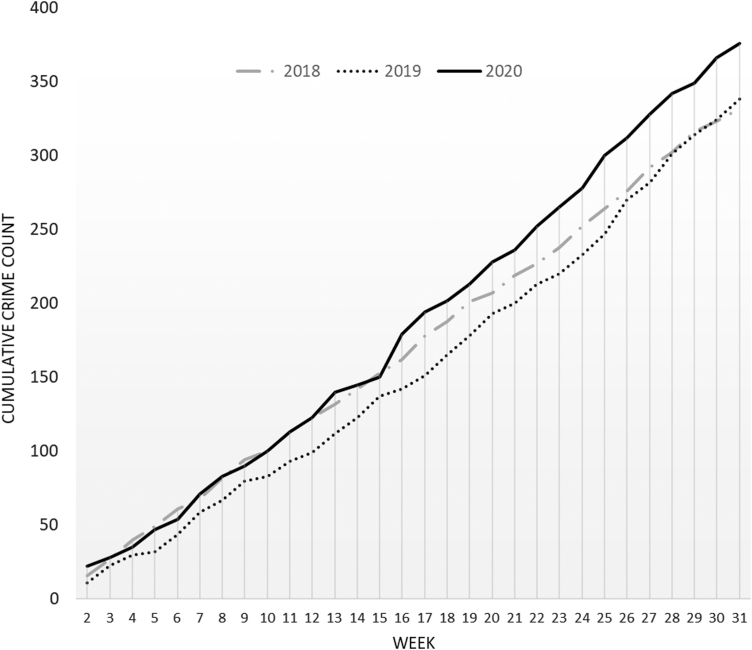

Compared with weeks 1–31 of 2018 and 2019 there has been a growth in Part I domestic crimes during 2020 as reported to the APD (Fig. 2). By week 31 of 2020, a total of 376 domestic incidents had been reported. Leading up to the pandemic the trendlines show that 2020 domestic crimes were occurring at a relatively similar pace as the counts observed in previous years, even overlapping with 2019. Then, a spike in domestic crimes was recorded following city and statewide shelter-in-place order (weeks 12–13). The uptick gained in intensity each passing week until it leveled off during the same time that the statewide shelter-in-place order was lifted in week 18. Domestic crimes began rising again in weeks 24–28, the period corresponding with the fallout from the murder of Rayshard Brooks and a spike in COVID-19 cases pulling the 2020 domestic crimes line even further from earlier years.

FIG. 2.

Growth in Atlanta Police Department reported Part I domestic crimes through August 1 by year.

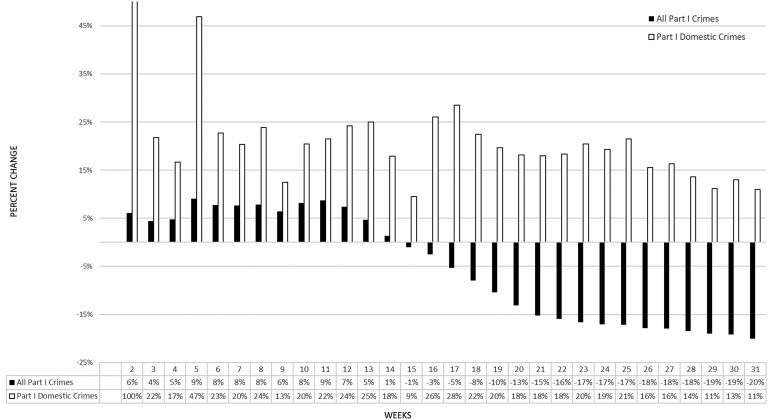

To understand the extent of the domestic crimes increase and see if it mirrored broader crime trends, we examined the percent change in crimes across the Part I total relative to domestic crimes (Fig. 2). The 2019–2020 percent change for domestic crimes was larger, yet in the same direction as all Part I offenses until week 14 when the statewide shelter in place was in effect.

In the subsequent weeks, domestic crimes increased by 11%, whereas Part I offenses decreased by 20%—a 31% difference (Fig. 3). It is notable that some of the highest domestic crime percent changes took place during the time that city and statewide shelter-in-place orders were in effect, whereas the largest decreases in Part I offenses align with the protests after George Floyd's death (Table 1).

FIG. 3.

Year-to-date Part I offenses: 2020–2019 percent change total versus domestic crimes through July 25, 2020.

Table 1.

Atlanta Police Reported Part I Domestic Crime Rate per 100,000 Residents

| Week No. | Start date | End date | 2020 Rate (population estimated 523,738) | 2019 Rate (population estimated 506,811) | 2018 Rate (population estimated 498,044) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | January 5 | January 11 | 4.201 | 2.170 | 3.213 |

| 3 | January 12 | January 18 | 5.346 | 4.538 | 5.421 |

| 4 | January 19 | January 25 | 6.683 | 5.919 | 8.031 |

| 5 | January 26 | February 1 | 8.974 | 6.314 | 9.838 |

| 6 | February 2 | February 8 | 10.310 | 8.682 | 12.248 |

| 7 | February 9 | February 15 | 13.556 | 11.641 | 13.653 |

| 8 | February 16 | February 22 | 15.848 | 13.220 | 16.464 |

| 9 | February 23 | February 29 | 17.184 | 15.785 | 18.874 |

| 10 | March 1 | March 7 | 19.094 | 16.377 | 20.079 |

| 11 | March 8 | March 14 | 21.576 | 18.350 | 22.689 |

| 12 | March 15 | March 21 | 23.485 | 19.534 | 24.697 |

| 13 | March 22 | March 28 | 26.731 | 22.099 | 26.504 |

| 14 | March 29 | April 4 | 27.686 | 24.269 | 28.512 |

| 15 | April 5 | April 11 | 28.640 | 27.032 | 30.720 |

| 16 | April 12 | April 18 | 34.177 | 28.018 | 32.527 |

| 17 | April 19 | April 25 | 37.041 | 29.794 | 35.740 |

| 18 | April 26 | May 2 | 38.569 | 32.557 | 37.748 |

| 19 | May 3 | May 9 | 40.669 | 35.122 | 40.358 |

| 20 | May 10 | May 16 | 43.533 | 38.081 | 41.563 |

| 21 | May 17 | May 23 | 45.061 | 39.462 | 43.972 |

| 22 | May 24 | May 30 | 48.116 | 42.028 | 45.578 |

| 23 | May 31 | June 6 | 50.598 | 43.409 | 47.787 |

| 24 | June 7 | June 13 | 53.080 | 45.974 | 50.598 |

| 25 | June 14 | June 20 | 57.281 | 48.736 | 53.007 |

| 26 | June 21 | June 27 | 59.572 | 53.274 | 55.417 |

| 27 | June 28 | July 4 | 62.627 | 55.642 | 58.629 |

| 28 | July 5 | July 11 | 65.300 | 59.391 | 60.637 |

| 29 | July 12 | July 18 | 66.636 | 61.956 | 63.448 |

| 30 | July 19 | July 25 | 69.882 | 63.929 | 64.854 |

| 31 | July 26 | August 1 | 71.792 | 76.557 | 66.661 |

Because population increases might affect domestic crimes counts, rates were calculated to validate yearly comparison results and report the effect size. Table 1 displays the Part I domestic crimes rates per 100,000 residents by year. It is estimated that the Atlanta population increased by more than 25,000 people between 2018 and 2020. After controlling for that difference, our results show that domestic crimes per capita have been rising in 2020 compared with previous years. In week 31, there were nearly 72 domestic crimes per 100,000 residents: over a 5-unit increase from the same weeks in 2018 and 2019.

Discussion

COVID-19 is a “once in a century pandemic” that has posed unprecedented challenges to health and economic systems; globally greater than 243 million women and girls are simultaneously at risk of increasing violence as part of the “shadow pandemic” (Gates 2020). Recognizing the potential for increased IPV risk as a result of the pandemic and its associated movement restrictions, this study sought to explore differences in domestic crime incidents reported to the police in Atlanta, Georgia before and during COVID-19.

We found that cumulative counts of domestic crimes were higher during the COVID-19 period of 2020 than in the preceeding two years suggesting increased occurrence of domestic violence, especially during shelter-in-place orders. This is consistent with a reported 42% increase in domestic violence calls, only 2% of which were repeat offenses suggesting increased first-time violence during the COVID-19 period (Braverman 2020). People in violent relationships may experience difficulty calling for help and they may be unsure if police will report to be able to help them given COVID-19. These call data suggest that at least some proportion of people experiencing violence are able to reach out to police; our data on increased incident reports suggest that police are reporting to assist during domestic incidents.

We observed that overall Part I offenses substantially decreased during the COVID-19 period relative to the previous year. This finding is in contrast to National Crime Victimization Survey data from 2015 to 2018, which indicated a 28% increase in violent victimizations (Morgan and Oudekerk 2019). As a small silver lining to the tremendous harms of the pandemic itself, our findings suggest that during the first few months of the COVID-19 pandemic Part I offenses slowed indicating a general decrease in crime in Atlanta, Georgia, even during periods of civil unrest; this is in contrast to media portrayal of civil protests during this period being violent or characterized by criminal activity.

However, during the same time period domestic crimes increased substantially, corroborating the “shadow pandemic” hypothesis and prior reports. People experiencing violence in their relationships during emergencies must weigh the risks of leaving during an uncertain time or staying and facing potential harm at the hands of a partner. The time during and shortly after a survivor leaves a violent relationship is known to be among the most dangerous and is a known femicide risk factor (Campbell et al. 2003).

These domestic incident data also suggest an overall increase in IPV. Under normal circumstances: poverty, unemployment, economic stress, and social isolation are all risk factors for violence perpetration (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2019; Jewkes et al. 2013). Many of these factors worsen in the contexts of natural disasters and emergencies, including notable increases in financial strain (UN Women 2020). Unemployment claims in Georgia have surged 400% since the onset of the pandemic, likely indicating co-occurring financial stress for many isolated at home (Hagemann and Booker 2020; Kanell 2020). Although employment status was not a variable in our data, the high unemployment rates in Georgia as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic may be contributing to higher incident reports and IPV occurrence. Addressing unemployment and financial hardship at the family level through the provision of direct economic assistance, unemployment benefits, and the reduction of housing and food insecurity should be a priority endeavor that would benefit those facing harms as a result of COVID-19 and those at risk of experiencing IPV. In addition, current pandemic response efforts ought to consider ways to specifically direct resources to domestic violence prevention and response programming—including as follow-up to Part I offenses—and in emergency rooms where those experiencing injury as a result of domestic crimes are likely to receive care; future emergency and preparedness plans should similarly include scaled-up IPV response given what is now known about the increased likelihood of increases in IPV during public health emergencies and natural disasters.

At the same time COVID-19 has been ravaging the United States, the country has experienced a racial justice reckoning (Elving 2020). As calls to defund the police mount, policy makers and communities must grapple with how to simultaneously address the health and safety concerns related to the pandemic—including potential increases in IPV—and the unacceptable harms being perpetrated by police against Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) [Black Lives Matter (BLM) 2020; Sinyangwe and McKesson 2020]. A public health approach is warranted to address both universal health care and violence prevention; police divestment and community investment strategies complement a public health approach and center BIPOC who are disproportionately impacted by both COVID-19 and IPV [Godoy and Wood 2020; Petrosky et al. 2017; The Movement for Black Lives (M4BL) 2020].

Limitations

We used readily available crime data to examine differences in Part I offenses including domestic offenses during the COVID-19 period. Our data come from one city, thus may not be generalizable; however, they do provide evidence into what is happening within Atlanta, Georgia, which policy makers can utilize. Although these data are timely and may serve as a rapidly available proxy, they are not equivalent to standard health measures such as IPV incidence. Because domestic crimes can include nonpartner relationships such as family violence, this measure is broader than IPV although inclusive of it; therefore, our data cannot be used as a direct measure of IPV. However, previous research suggests around half of violent victimizations go unreported to the police (Morgan and Kena 2018). Therefore, it is likely that the data on domestic crime presented here are still an underestimation of IPV. The absence of domestic crimes during Part II incidents within our data is another limitation, although one that underscores the idea that our data are reflective of an underestimation. Given that health data routinely lag years behind—and given the urgency of the potential harms of the pandemic—we believe use of police data are appropriate even given their limitations.

Conclusions

As the COVID-19 pandemic continues, future research exploring differences in IPV-related injuries in health care settings and IPV support services demand and utilization during the COVID-19 pandemic would complement the data presented, especially because anecdotal reports suggest a marked increase in demand for services (Fox 5 Atlanta 2020; Oppenheimer and Rayam 2020). Additional analysis accounting for pandemic-related movement restrictions would also provide nuance into the effects of these restrictions on IPV occurrence, allowing for more appropriate planning by policy makers as they work to balance protection of public health with limitations on free movement during the COVID-19 pandemic and in other future public health emergencies.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the APD for the provision of timely open source crime data. The authors are also grateful to the Injury Prevention Research Center at Emory University for facilitating the introduction of the authors and this collaboration.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Funding Information

No funding was received in support of this work.

Podcast

This article includes a podcast interview. Go behind the scenes with the authors by visiting Violence and Gender online (podcast available online).

Supplementary Material

References

- Abramson A. (2020). How COVID-19 may increase domestic violence and child abuse. Retrieved from https://www.apa.org/topics/covid-19/domestic-violence-child-abuse (accessed October23, 2020)

- Atlanta Police Department (APD). (2020). Crime data downloads. Retrieved from https://www.atlantapd.org/i-want-to/crime-data-downloads (accessed October23, 2020)

- Bell S, Folkerth L. (2016). Women's mental health and intimate partner violence following natural disaster: A scoping review. Prehosp Disaster Med. 31, 648–657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black Lives Matter (BLM). (2020). What defunding the police really means. Retrieved from https://blacklivesmatter.com/what-defunding-the-police-really-means/ (accessed October23, 2020)

- Black M, Basile K, Breiding J, et al. (2011). The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS): 2010 Summary Report. (National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA.) [Google Scholar]

- Bosman J. (2020). Domestic violence calls mount as restrictions linger: ‘No one can leave’. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/15/us/domestic-violence-coronavirus.html (accessed October23, 2020)

- Boxall H, Morgan A, Brown R. (2020). The prevalence of domestic violence among women during the COVID-19 pandemic. Retrieved from https://www.aic.gov.au/sites/default/files/2020-07/sb28_prevalence_of_domestic_violence_among_women_during_covid-19_pandemic.pdf (accessed October23, 2020)

- Braverman J. (2020). APD says domestic violence crimes up 42% while other crimes down significantly during COVID-19 pandemic. Retrieved from https://www.11alive.com/article/news/health/coronavirus/apd-says-domestic-violence-crimes-up-42-while-other-crimes-down-significantly-during-covid-19-pandemic/85-63770e9d-5722-48a9-b2b1-9cb2d43aa43f (accessed October23, 2020)

- Burns A. (2020). Stay-at-home order poses new problems for family violence victims, shelters. Retrieved from https://www.ajc.com/news/breaking-news/stay-home-order-poses-new-problems-for-family-violence-victims-shelters/HKeZoZvHJIoKVzi8fI7okO (accessed October23, 2020)

- Campbell J, Webster D, Koziol-McLain J, et al. (2003). Risk factors for femicide in abusive relationships: Results from a multisite case control study. Am J Public Health. 93, 1089–1097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019). Risk and protective factors for perpetration. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/intimatepartnerviolence/riskprotectivefactors.html (accessed October23, 2020)

- Crombie N. (2020). Calls to Oregon's domestic violence crisis lines spike amid coronavirus crisis. The Oregonian. Retrieved from https://www.oregonlive.com/crime/2020/03/calls-to-oregons-domestic-violence-crisis-lines-spike-amid-coronavirus-crisis.html (accessed October23, 2020)

- Elving R. (2020). Will this be the moment of reckoning on race that lasts?. National Public Radio. Retrieved from https://www.npr.org/2020/06/13/876442698/will-this-be-the-moment-of-reckoning-on-race-that-lasts (accessed October23, 2020)

- Emezue C. (2020). Digital or digitally delivered responses to domestic and intimate partner violence during CoVID-19. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 6, e19831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fausset R, Levenson M. (2020, May 30). Atlanta protesters clash with police as mayor warns ‘you are disgracing our city’. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/29/us/atlanta-protest-cnn-george-floyd.html (accessed October23, 2020)

- FOX 5 Atlanta. (2020). Governor: Domestic violence cases up, child abuse reports down in Georgia. Retrieved from https://www.fox5atlanta.com/news/governor-domestic-violence-cases-up-child-abuse-reports-down-in-georgia (accessed October23, 2020)

- García-Moreno C, Pallitto C, Devries K, et al. (2013). Global and regional estimates of violence against women: Prevalence and health effects of intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence. (World Health Organization, Geneva.) [Google Scholar]

- Gates B. (2020). Responding to Covid-19—A once-in-a-century pandemic? N Engl J Med. 382, 1677–1679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgia Commission on Family Violence (GCFV). (2020). Domestic violence in Georgia. Retrieved from https://gcfv.georgia.gov/document/document/2020-gcfv-fact-sheet/download (accessed October23, 2020)

- Godin M. (2020). France to house domestic abuse victims in hotels amid lockdown. Retrieved from https://time.com/5812990/france-domestic-violence-hotel-coronavirus/ (accessed October23, 2020)

- Godoy M, Wood D. (2020). What do coronavirus racial disparities look like state by state?. Retrieved from https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2020/05/30/865413079/what-do-coronavirus-racial-disparities-look-like-state-by-state (accessed October23, 2020)

- Hagemann H, Booker B. (2020). Georgia beginning to reopen its economy, lifting some coronavirus-crisis limits. Retrieved from https://www.npr.org/sections/coronaviruslivupdates/2020/04/20/839338550/georgiabeginning-to-reopen-its-economy-lifting-some-coronavirus-crisis-limits (accessed October23, 2020)

- Jarvie J. (2020). Georgia reopened first. What the data show is a matter of fierce debate. Retrieved from https://www.latimes.com/world-nation/story/2020-05-23/georgia-reopened-first-the-data-say-whatever-you-want-them-to (accessed October23, 2020)

- Jewkes R, Fulu E, Roselli T, Garcia-Moreno C. (2013). UN Multi-Country Cross Sectional Study on Men and Violence. Prevalence of and factors associated with male perpetration of intimate partner violence: Findings from the UN Multi-country Cross-sectional Study on Men and Violence in Asia and the Pacific. Lancet Global Health. 1, e208–e218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John N, Casey S, Carino G, McGovern T. (2020). Lessons never learned: Crisis and gender-based violence. Dev World Bioeth. 20, 65–68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanell M. (2020, March 20). Jobless claims soar in Georgia—Worse likely coming. Retrieved from https://www.ajc.com/business/jobless-claims-soar-georgiaworse-likely-coming/zTXTHDiTe1i2HK3SYJGmWL (accessed October23, 2020)

- Macaya M, Hayes M. (2020). Arrest warrants issued for 6 Atlanta police officers in excessive force case. Retrieved from https://www.cnn.com/us/live-news/george-floyd-protests-06-02-20/h_98f026c33f5f4bdcbe991cbed382af97 (accessed October23, 2020)

- Mlambo-Ngcuka P. (2020). Violence against women and girls: The shadow pandemic. Retrieved from https://www.unwomen.org/en/news/stories/2020/4/statement-ed-phumzile-violence-against-women-during-pandemic (accessed October23, 2020)

- Moreira D, Pinto da Costa M. (2020). The impact of the Covid-19 pandemic in the precipitation of intimate partner violence. Int J Law Psychiatry. 71, 101606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan R, Kena G. (2018). Criminal victimization, 2016: Revised (NCJ 252121). Bureau of Justice Statistics. Retrieved from https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/cv16.pdf (accessed October23, 2020)

- Morgan R, Oudekerk B. (2019). Criminal victimization, 2018 (NCJ 253043). Bureau of Justice Statistics, US Department of Justice. Retrieved from https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/cv18.pdf (accessed October23, 2020)

- New York Times. (2020).Georgia coronavirus map and case count. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/us/georgia-coronavirus-cases.html (accessed October23, 2020)

- Onyango M, Resnick K, Davis A, Shah R. (2019). Gender-based violence among adolescent girls and young women: A neglected consequence of the West African Ebola outbreak. In Pregnant in the Time of Ebola. DA Schwartz, JN Anok, SA Abramowitz, eds. (Springer, Cham), pp. 121–132 [Google Scholar]

- Oppenheimer L, Rayam L. (2020). APD is reporting rising domestic violence calls. Here's how one Atlanta safe house is coping. WABE. Retrieved from https://www.wabe.org/atlanta-police-say-reported-domestic-violence-cases-last-month-increased-by-36-percent-compared-to-march-2019-heres-how-one-atlanta-safe-house-is-coping (accessed October23, 2020)

- Petrosky E, Blair J, Betz C, et al. (2017). Racial and ethnic differences in homicides of adult women and the role of intimate partner violence—United States, 2003–2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 66, 741–746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raymond J. (2020). Georgia's shelter-in-place order has expired: What it means for you at home. Retrieved from https://www.cbsnews.com/news/coronavirus-georgia-brian-kemp-governor-businesses-reopen-friday (accessed October23, 2020)

- Sinyangwe S, McKesson D. (2020). Mapping police violence: Police violence map. Retrieved from https://mappingpoliceviolence.org

- Stark L, Ager A. (2011). A systematic review of prevalence studies of gender-based violence in complex emergencies. Trauma Violence Abuse. 12, 127–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strianese R. (2020). Forced coexistence is an alarm for violence against women. Retrieved from https://www.ottopagine.it/av/attualita/211981/convivenza-forzata-e-allarme-per-la-violenza-sulle-donne.shtml (accessed October23, 2020)

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). (2020). Intimate partner violence and child abuse considerations during COVID-19. Retrieved from https://www.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/social-distancing-domestic-violence.pdf (accessed October23, 2020)

- The Movement for Black Lives (M4BL). (2020). Policy platforms: Invest-divest. Retrieved from https://m4bl.org/policy-platforms/invest-divest

- UN Women. (2020). PREVENTION: Violence against women and girls & COVID-19. New York: UN Women. Retrieved from https://www.unwomen.org/media/headquarters/attachments/sections/library/publications/2020/brief-prevention-violence-against-women-and-girls-and-covid-19-en.pdf?la=en&vs=3049 (accessed October23, 2020)

- U.S. Department of Justice. (n.d.). UCR offense definitions. Retrieved from https://www.bjs.gov/ucrdata/offenses.cfm (accessed October23, 2020)

- U.S. Department of Justice. (2011). Violent crime. Retrieved from https://ucr.fbi.gov/crime-in-the-u.s/2010/crime-in-the-u.s.-2010/violent-crime (accessed October23, 2020)

- Violence Policy Center (VPC). (2019). When men murder women: An analysis of 2017 homicide data. Retrieved from https://vpc.org/studies/wmmw2019.pdf (accessed October23, 2020)

- Wall Street Journal. (2020). George Floyd protests: Atlanta killing by police officer stirs unrest. Retrieved from https://www.wsj.com/livecoverage/protests-george-floyd-death-2020-06-13 (accessed October23, 2020)

- Wanqing Z. (2020). Domestic violence cases surge during COVID-19 epidemic. Retrieved from https://www.sixthtone.com/news/1005253/domestic-violence-cases-surge-during-covid19-epidemic (accessed October23, 2020)

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2012). Understanding and addressing violence against women: Intimate partner violence (No. WHO/RHR/12.36). (World Health Organization, Geneva.) [Google Scholar]