Abstract

Introduction: People of color and low-income and uninsured populations in the United States have elevated risks of adverse maternal health outcomes alongside low levels of postpartum visit attendance. The postpartum period is a critical window for delivering health care services to reduce health inequities and their transgenerational effects. Evidence is needed to identify predictors of postpartum visit attendance in marginalized populations.

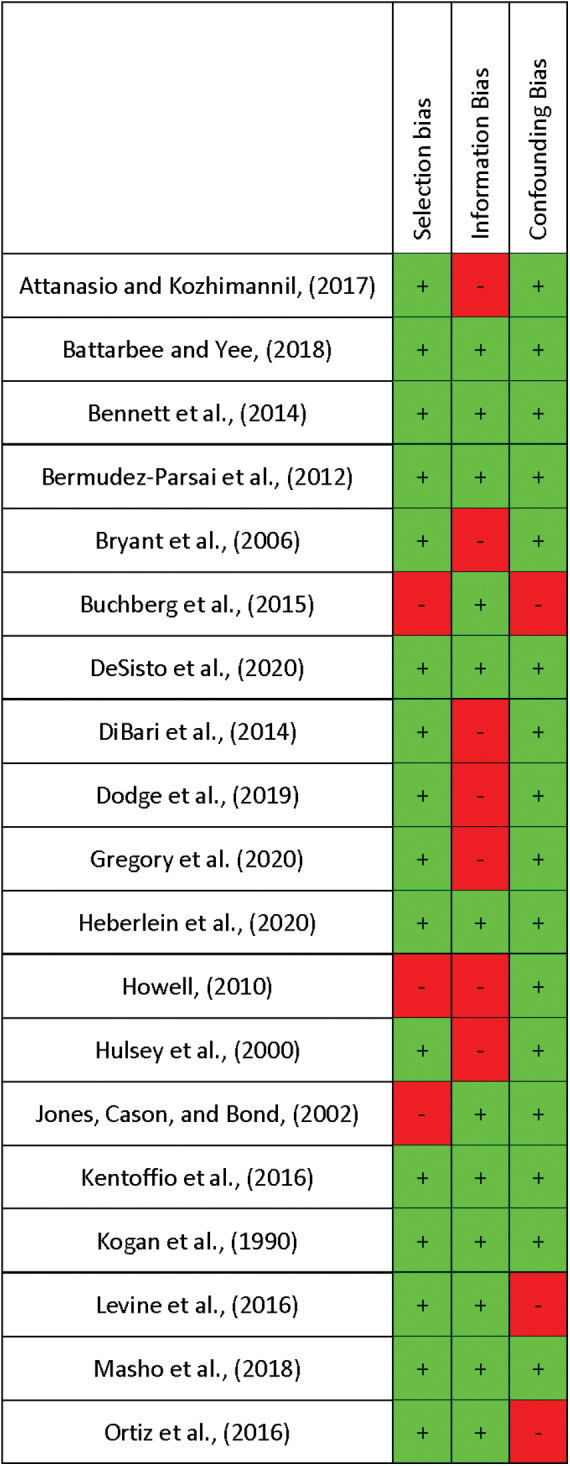

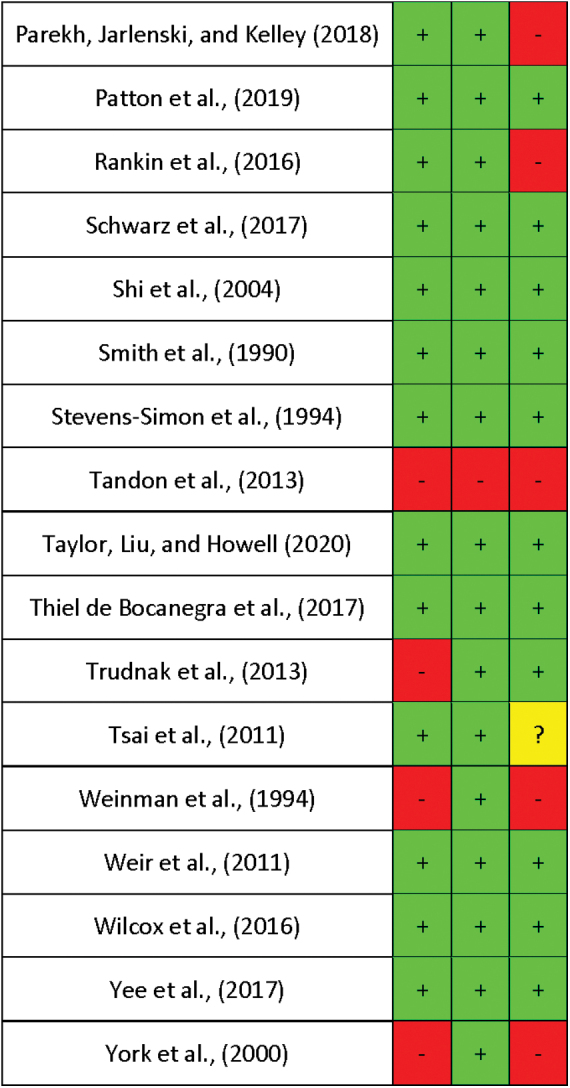

Methods: We conducted a systematic review of the peer-reviewed literature to identify studies that quantified patient-, provider-, and health system-level predictors of postpartum health care use by people of color and low-income and uninsured populations. We extracted study design, sample, measures, and outcome data from studies meeting our eligibility criteria, and used a modified Cochrane Risk of Bias tool to evaluate risk of bias.

Results: Out of 2,757 studies, 36 met our criteria for inclusion in this review. Patient-level factors consistently associated with postpartum care included higher socioeconomic status, rural residence, fewer children, older age, medical complications, and previous health care use. Perceived discrimination during intrapartum care and trouble understanding the health care provider were associated with lower postpartum visit use, while satisfaction with the provider and having a provider familiar with one's health history were associated with higher use. Health system predictors included public facilities, group prenatal care, and services such as patient navigators and appointment reminders.

Discussion: Postpartum health service research in marginalized populations has predominantly focused on patient-level factors; however, the multilevel predictors identified in this review reflect underlying inequities and should be used to inform the design of structural changes.

Keywords: postpartum, health care utilization, marginalized populations

Introduction

More than half of pregnancy-related mortality in the United States occurs in the postpartum period.1 One-third of these deaths occur after the first week following birth when health care is typically irregular, fractured, and misaligned with new mothers' health priorities.2,3 The importance of improving postpartum health care has been underscored by updated guidelines from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), which recommend comprehensive health care services to address a mother's physical, social, and psychological well-being across the 3 months after birth (ACOG, 2018).4 Understanding predictors of postpartum health care use can inform the design of quality postpartum services that are accessible to communities most burdened by maternal health inequities.

Black and Indigenous mothers in the United States have the highest risks of pregnancy-related mortality and morbidity1,5–7 and Hispanic and Asian mothers have elevated risks of severe maternal morbidity.8–10 People of color and low-income and/or uninsured mothers have been found to have low rates of postpartum health care use.11–16 Low-income mothers, those who do not speak English at home, and those covered by public insurance are more likely to lose insurance coverage in the 6 months following birth,17 and many rely on emergency departments for necessary postpartum medical care.18–21 Distrust of the health system resulting from experiences of discrimination and mistreatment has also been shown to deter some racial and ethnic groups from using care.22–25

Healthy People 2020 includes an objective to increase the percentage of women who attend a postpartum visit with a health worker following delivery.26 While nationally about 90% of mothers attended a postpartum visit in 2012, only about 58% of Medicaid-insured mothers attended this visit.27 The postpartum visit and ongoing process of care recommended by ACOG offer opportunities to address the intersecting health concerns of new mothers, including infant feeding, physical recovery, and emotional well-being.2 In addition, postpartum visit attendance in the first 2 months after birth is associated with increased use of primary care services in subsequent years.19 To our knowledge, predictors of postpartum health care use have not yet been summarized. It is critical to identify these predictors among marginalized populations to improve health care engagement and reduce health inequities.

The purpose of this systematic review is to summarize the literature on predictors of postpartum visit attendance in marginalized populations in the United States. We identified patient-, provider-, and health system-level factors associated with postpartum health care use by people of color and low-income and/or uninsured populations that can inform the design of future interventions and policies. We applied a health disparities conceptual framework for health service research to assess and organize these multilevel predictors.28

Materials and Methods

Search strategy

Our systematic review protocol was registered in PROSPERO: International prospective register of systematic reviews in 2019 (CRD42019133990). The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) checklist guided our review methods.29 A medical librarian developed search strategies on postpartum health care utilization by low-income, uninsured, and/or mothers from racial and ethnic minority groups.

The search strategies included a combination of subject headings and keywords and were used to search PubMed, CINAHL Plus, and Web of Science, from date of database inception to March 7, 2019, and then again on June 5, 2020, when all searches were updated. In addition to these databases, the ClinicalTrials.gov website was searched for any past or current trials. One of the investigators additionally reviewed references of included studies to identify additional publications meeting eligibility criteria. No filters or limits were added to any of the searches. The complete strategy for all searches can be found in Supplementary Figure S1.

Study selection

Two investigators independently screened all study titles and abstracts, and included studies where they met the following criteria: (1) published in a peer-reviewed journal; (2) conducted in the United States; (3) reported patient-, provider-, or health system-level predictors of postpartum health care use in low income, uninsured, and/or people of color; and (4) defined the outcome as any health care visit occurring in the 3 months following birth, pregnancy loss, or termination or, if no time period was specified, as an outpatient “postpartum visit.” Systematic reviews and studies of (1) postpartum health outcomes other than health service use, (2) predictors of postpartum hospital readmission, or (3) specialist health care use or treatment were excluded. A third investigator resolved any discrepancy.

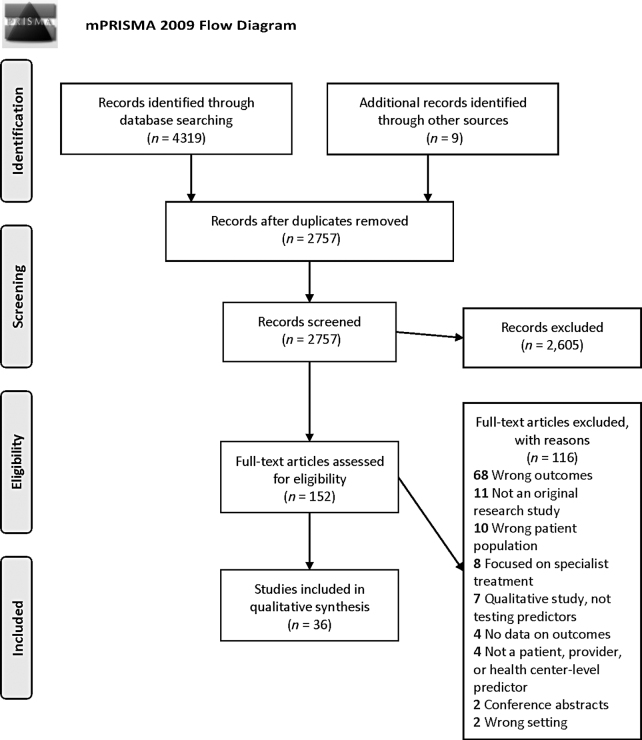

Next, two investigators screened all studies included in the full-text review. Qualitative studies were excluded at this stage, as our review aims to identify predictors of postpartum health care use tested through statistical modeling. The PRISMA diagram in Figure 1 illustrates the number of studies excluded at each stage of screening.

FIG. 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) diagram. From: Moher et al.75 For more information, visit www.prisma-statement.org

Data extraction

Two investigators extracted data from each study meeting inclusion criteria (Tables 1 and 2). Data were extracted on the study objectives, design, sample size, participants, data sources, predictor and outcome measures, statistical methods, efforts to minimize bias, and descriptive and statistical results. Predictors reported by each study were classified as patient-, provider-, and health system-level characteristics based on the clinical and substantive expertise of the investigators. Predictor variables were identified as statistically associated with postpartum visit attendance based on a two-tailed hypothesis test at p < 0.05.

Table 1.

Study Characteristics

| Authors (year) | Study objectives | Study design | Sample size | Participants | Data source/measurement |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attanasio and Kozhimannil (2017) | To assess whether perceptions of discrimination during intrapartum hospitalization are associated with postpartum visit attendance | Cross-sectional | 2,400 | Women with singleton births in U.S. hospitals in 2011–12 drawn from online panels and weighted to be representative of the national childbearing population | Listening to Mothers III survey |

| Battarbee and Yee (2018) | To determine patient and provider factors associated with receipt of postpartum care after a pregnancy complicated by GDM | Cohort analysis | 683 | Women diagnosed with GDM who delivered at NMH in 2008–2016 and received care in 1 of 4 practices; excluded if history of pregestational diabetes (DM) or delivery at an outside hospital. If a woman had multiple pregnancies with GDM, only data for the index pregnancy included | Electronic medical records |

| Bennett et al. (2014) | To compare health care use after birth between mothers with and without pregnancy complications | Cohort analysis | 37,751 deliveries: 8,389 complicated and 28,054 comparison | Women age >12 and <45 years with a delivery defined by HEDIS in 2003–2009. Included ICD-9-CM codes for stillborn and multiple gestation births. Applied 2 insurance coverage requirements: pregnancy coverage ≥100 days and ≥42 days after delivery | Claims data from 2 plans managed by Johns Hopkins HealthCare: a Medicaid MCO in Maryland, and a self-insured commercial health benefit plan that covers most university employees |

| Bermúdez-Parsai et al. (2012) | To assess if more acculturated women are more likely to access postpartum care | Prospective cohort study of intervention group drawn from an RCT | 172 controls and 202 in the intervention | Patients of Women's Care Clinic at Maricopa Medical Center in Phoenix, Arizona: >18 years old, enrolled at ≤34 weeks gestation with no prior prenatal visits at recruitment | Predictor and covariate data drawn from surveys at enrollment into RCT; outcome data drawn from patient medical record |

| Bryant et al. (2006) | To determine factors associated with postpartum visit use by low-income women served by 14 Healthy Start sites, using Andersen's behavioral model of health services use | Cross-sectional | 1,637 | Face-to-face interviews conducted with Healthy Start participants and nonparticipants living in project areas December 1995 to April 1996. Women interviewed before 6 weeks postpartum were excluded. | Healthy Start Survey of Postpartum Women designed to collect information on the prenatal and postpartum experiences of women in Healthy Start Project Areas |

| Buchberg et al. (2015) | To identify and describe the factors associated with postpartum care among a sample of low-income, HIV-infected women in the southern United States | Prospective cohort study | 35 | Participants recruited from 2 clinics in Houston, Texas, providing obstetric care for uninsured/underinsured HIV-infected women. Included those HIV infected, ≥18 years, able to read and write in English/Spanish, in the 2nd/3rd trimester, and intending to continue care with the county postpartum. | Baseline assessment used self-report demographic, behavioral, and psychosocial measures. The county electronic medical record used for HIV-related data at baseline and delivery and on all current and historical patient appointments. |

| DeSisto et al. (2020) | To compare postpartum health care use for women with continuous Medicaid eligibility versus pregnancy-only Medicaid | Cohort analysis | 105,718 | Medicaid-insured women in Wisconsin who delivered a live birth 2011–2015. For women with >1 live birth, one was randomly selected to be included. Women using emergency Medicaid and pregnant inmates excluded. | Medicaid claims, Medicaid eligibility, and infant birth certificates |

| DiBari et al. (2014) | To examine the extent to which postpartum care use is related to sociodemographic characteristics and to identify factors that decrease postpartum care use | Cross-sectional | 4,075 | Probability sample of mothers contacted within 6 months after birth who lived in a stratified random sample of census tract-defined neighborhoods in Los Angeles County, California, who had a live birth in LA County in 2007 | LAMB study data through mailed surveys. Surveys were available in Spanish and Chinese and a phone translation service provided access in 88 languages. Survey data linked to birth certificate data. |

| Dodge et al. (2019) | To test implementation and impact of the FC nurse home visiting program | RCT | 316 | Discharge records from women who gave birth at Duke University Hospital January 1, 2014, to June 30, 2014: 456 odd-date births assigned to the FC intervention and 456 even-date births received usual care | Maternal interview at 6 months postpartum |

| Gregory et al. (2020) | To use Andersen's behavioral model of health service use to determine which factors drive health care use in the period following birth | Cohort analysis of a cluster RCT designed to test receipt of interconception care in the pediatric setting | 376 | Women eligible for the RCT up to 1 year after birth; English or Spanish speaking. Enrolled October 2013–March 2015 during infant well visits at 4 pediatric primary care sites in the Baltimore, Maryland metropolitan area; analysis includes those interviewed 6–15 months postpartum. | Maternal in-person self-report at enrollment and through telephone interview at 6 and 12 months after enrollment. Study instruments developed using validated items from national surveys or studies. |

| Heberlein et al. (2020) | To study the effect of CenteringPregnancy group prenatal care versus individual care on postpartum visit attendance | Cohort analysis | 15,922 | CenteringPregnancy in 18 sites across South Carolina representing academic medical centers, family medicine practices, and private OB-GYN practices where ≥1 Centering Pregnancy group has had all mothers give birth and have birth certificates processed. All women had viable pregnancies covered by Medicaid. Excluded women with more than one birth (or multiple gestation). | Medicaid claims and matched birth certificate data for births occurring in the 18 sites between 2013 and 2017 |

| Howell (2010) | To assess whether counseling from obstetricians and midwives prepared patients to expect common postpartum symptoms and whether preparation was associated with satisfaction with the health care provider | Sample drawn from a prospective longitudinal cohort study, but data for this analysis come from cross-sectional interviews | 621 at 3-month interview | Mothers who delivered without complications at an urban tertiary care academic medical center in New York City in 2002. Inclusions: ≥18, English/Spanish speaking, healthy neonate; and reached at 3 months postpartum. Exclusions: hospitalization >3 days (vaginal) or >5 days (cesarean) postdelivery. | Interviews at 2–6 weeks postpartum and at 3 months postpartum used a survey with both validated and new scales |

| Hulsey et al. (2000) | To examine sociodemographics, feelings about pregnancy, consideration of abortion, use of birth control at time of conception, and pregnancy intendedness as predictors of a missed postpartum visit | Prospective cohort study | 319 | Convenience sample of women using prenatal care at a tertiary clinic in Detroit in 1996–1997. Eligible if English speaking and Medicaid eligible and entering prenatal care ≤32 weeks gestation. First interview occurred ≤32 weeks gestation; postpartum interview occurred ≤48 weeks postpartum. | Prenatal and postpartum interviews were conducted in person by a research assistant reading questions and filling in responses on a scannable form. Questionnaires were informed by national databases such as the National Survey of Family Growth. |

| Jones et al. (2002) | To describe the relationship between pay category and attending a postpartum family planning visit | Prospective cohort study | 397 | Convenience sample of pregnant women with Hispanic surnames drawn from those attending 4 community-based prenatal clinics affiliated with a public teaching hospital system in Dallas, Texas, serving the community's Hispanic population (mostly Mexican). | Questionnaire at the prenatal visit for acculturation and demographic information (in English or Spanish), medical record review for health information and postpartum visit attendance/contraceptive use, and health system database for payor information |

| Kentoffio et al. (2016) | To determine how prenatal care initiation among refugees in the United States compares with that of U.S.-born women, and to evaluate the overall use of prenatal and postpartum health services among these women in a setting where basic health insurance is available regardless of immigration status | Matched case–control | 375 | Patients of CHC, a state-designated refugee clinic and community health center in MA where comprehensive insurance is universally available to refugees. Refugee women ≥18 who arrived to the United States in 2001–2013 and initiated care at CHC were eligible; matched by age, gender, and date of care initiation in a 1:3 ratio to (1) Spanish-speaking nonrefugee immigrants and (2) English-speaking controls. Excluded if pregnancies ended in abortion <20 weeks gestation. | Electronic medical records with information from >40 primary care practices and several tertiary care hospitals. |

| Kogan et al. (1990) | To determine factors associated with returning for a postpartum visit | Cohort analysis | 13,921 | Women registered for care between 1985 and 1987 at MA sites of an MIC Program, who remained in the program through delivery | Records of 21 MIC offices run by the MA Department of Public Health and located at community-based facilities in high-risk areas |

| Levine et al. (2016) | To determine factors associated with lower postpartum follow-up rates among women with PEC-S | Cohort analysis | 193 | Women with PEC-S diagnosed before active labor, carrying a singleton gestation, ≤34 weeks gestation, and delivering 2011–2013 at Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania. | Electronic medical records |

| Masho et al. (2018) | To use Anderson's behavioral model of health service use to identify correlates of postpartum visit use; focused on individual characteristics, personal health choices, health care needs, and health service use | Cohort analysis | 25,692 | Women with singleton live births who received prenatal care through a nonprofit MCO that provides public insurance for about 200,000 Medicaid patients across Virginia. If a mother gave birth >once in the time period, the most recent birth was analyzed. | Claims, demographic, and administrative data were obtained from Virginia Premier between 2008 and 2012. |

| Ortiz et al. (2016) | To determine the proportion of women with GDM, who receive a postpartum visit and glucose screen | Cohort analysis | 97 | Women with a GDM diagnosis from a large tertiary hospital in New Mexico, who gave birth in 2012. | A sample of electronic medical records from across the calendar year |

| Parekh et al. (2018) | To assess disparities by race, ethnicity, region, MCO, and year in the provision and timeliness of postpartum care for women enrolled in Pennsylvania Medicaid | Cohort analysis | 12,228 | Representative sample of women of all ages continuously enrolled in a Medicaid Managed Care program called HealthChoices, which comprises Pennsylvania's 8 Medicaid MCOs. | HEDIS member-level data files from the HealthChoices MCOs from calendar years 2012–2015 |

| Patton et al. (2019) | To investigate the impact of Medicaid expansion on length of Medicaid coverage after delivery in women with an OUD diagnosis during pregnancy and to test the association between Medicaid expansion and use of postpartum health care | Cohort analysis | 1,562 (744 preexpansion and 818 postexpansion) | Women 15–45 with a live birth covered by Pennsylvania Medicaid and a prenatal diagnosis of OUD. Excluded those with dual Medicaid-Medicare eligibility or non-Pennsylvania residency. Pre-Medicaid expansion group delivered Nov 1, 2013–March 1, 2014; postexpansion group delivered November 1, 2014–March 1, 2015. All followed for 300 days postdelivery. | Medicaid health care data provided by the Pennsylvania Department of Human Services. |

| Rankin et al. (2016) | To describe patterns of postpartum care received through 90 days postpartum by Illinois women with Medicaid-paid deliveries in 2009 and 2010 | Cohort analysis | 55,577 | Women with a Medicaid-paid delivery for a livebirth or stillbirth in 2009–2010. Women with managed care claims (6.9%) versus fee-for-service claims from traditional Medicaid were excluded. Second deliveries to the same woman were also excluded. | Illinois Medicaid Analytic Extract data. Encounters for care in the first 90 days postpartum used CPT and ICD-9-CM codes. Data from the American Community Survey 2008–2012 were linked by zip code of residence. |

| Schwarz et al. (2017) | To test associations between preconception DM or GDM and postpartum visit attendance | Cohort analysis | 199,860 | Women 15–44 with a singleton or multiple gestation live birth, 2011–2012, continuously enrolled in California's Medicaid program from 43 days before 99 days after delivering. | Medi-Cal claims and encounter data with procedure and diagnosis codes, verified using birth statistical master file records |

| Shi et al. (2004) | To examine receipt of perinatal services across racial/ethnic groups receiving care in community health centers | Cross-sectional | 572,578 | Women who used prenatal care services between 1996 and 2001 from about 700 community health centers | Aggregate community health center-level data from the UDS |

| Smith et al. (1990) | To assess if different incentives affect postpartum care use among adolescents | RCT | 534 | Adolescents 12–19 years old enrolled in a large county hospital in the Southwest in 1988–1989. Exclusions: if not continuously enrolled in Medi-Cal from 43 days before through 99 days after delivery and if incomplete claims data or missing data on race/ethnicity, language, or delivery | Clinic records |

| Stevens-Simon et al. (1994) | To test the hypothesis that incentives enhance postpartum visit attendance | RCT | 240 | Adolescents 12–19 years of age enrolled in the Colorado Adolescent Maternity Program randomized at about 34 weeks gestation to incentive and nonincentive groups | Medical records and patient interviews |

| Tandon et al. (2013) | To examine the effectiveness of the CenteringPregnancy group prenatal care model in improving maternal and child health outcomes, including postpartum visit attendance | Prospective cohort study | 214 | Pregnant women from 2 Palm Beach County public health clinics who identified as Hispanic or Mayan and were ≤20 weeks gestation in 2008–2009; offered the choice of Centering Pregnancy or traditional care. | Palm Beach County Health Department medical records used to obtain the number of prenatal visits; all other information from a baseline (within 2 weeks of enrollment) and follow-up (3 months postpartum) survey |

| Taylor et al. (2020) | To compare health care use by insurance status among women giving birth after the implementation of the ACA in 2014 | Cohort analysis | 9,613 | Women 18 years of age and older who had a live birth during 2014–15 and resided in Mecklenburg County, North Carolina. Excluded if gestational age at delivery >42 weeks or missing; invalid address; no documented prenatal visits; insurance status not classified as commercial, Medicaid, or uninsured; and missing neighborhood level data or BMI | Electronic medical records from the Atrium Health electronic data warehouse, a centralized data repository of clinical and billing data from all hospitals and physician offices affiliated with a large vertically integrated health care system in North Carolina |

| Thiel de Bocanegra et al. (2017) | To assess racial/ethnic variation in receipt of postpartum care among low-income women in California | Cohort analysis | 199,860 | Women with deliveries of live births from November 6, 2011–November 5, 2012 | Medi-Cal administrative data (including claims and encounter data) and Family PACT Health Access Program data |

| Trudnak et al. (2013) | To compare postpartum visit attendance between women in a CenteringPregnancy program and individual prenatal care | Cohort analysis | 240 | Women identified as Spanish-speaking and of Hispanic ethnicity, entered into prenatal care at the clinic for an initial visit November 2006–November 2009, and completed prenatal care by June 2010. Excluded if transferred out of the clinic, stopped care, had an initial prenatal care visit after 4 months gestation, or did not complete ≥50% of their expected number of visits. Participants were offered the choice of group or individual care. | Patient charts and vital statistics data, 2006–2010 |

| Tsai et al. (2011) | To study postpartum follow-up rates, as well as counseling opportunities before and after a postpartum quality improvement initiative was implemented | Pre-post intervention | 221 | Clients who received prenatal care at an urban clinic, QEC, in Honolulu, Hawai'I, and delivered between April 2006 and April 2008. Excluded if delivered at QEC, but had no prenatal care or received PNC from another facility. | QEC medical records, 2006–2008 |

| Weinman and Smith (1994) | To examine factors associated with postpartum care use in a population of adolescent mothers who delivered at a county hospital in Texas | Cohort analysis | 255 | Hispanic adolescents <20 years of age who delivered an infant at Harris County Hospital District, scheduled a postpartum visit at the teen health clinic, and provided informed consent | Medical charts at Harris County Hospital District |

| Weir et al. (2011) | To examine factors associated with prenatal and postpartum health care use in a sample of women with Medicaid insurance coverage; informed by Andersen's model of health services use | Cohort analysis | 1,858 | Women with Medicaid insurance coverage in MA and delivered a live-born infant in 2005–2006. Women had to have continuous enrollment in MassHealth Medicaid program for 43 days before delivery through 56 days postdelivery; had to have complete data on the outcome and covariates. | Linked individual HEDIS data with MassHealth (Medicaid program) claims files |

| Wilcox et al. (2016) | To identify predictors of postpartum visit nonattendance | Cohort analysis | 4,049 | Women who delivered a live birth at Montefiore Health System in the Bronx, New York, in 2013, who also received prenatal care at a Montefiore affiliated site. | Electronic medical records |

| Yee et al. (2017) | To estimate if postpartum visit attendance improved following the adoption of a patient navigator program | Pre-post intervention | 474 | Intervention women received prenatal care in a clinic at NMH and delivered an infant ≥2nd trimester May 30, 2015–May 30, 2016, and received patient navigation support to schedule their postpartum visit. Comparison group received prenatal care in the same clinic, delivered with same conditions May 30, 2014–May 30, 2015; Excluded if <18 years of age, HIV positive, or non-English speaking. | Medical records |

| York et al. (2000) | To examine the relationship between prenatal care use and postpartum maternal and infant health care use among women at high risk for inadequate prenatal care | Prospective cohort study | Original sample: 297; analytic sample: 180 | African American women with <high school education, receiving Medicaid (or eligible to receive Medicaid), who delivered at a large metropolitan teaching hospital. Excluded those with a history of chronic disease. | Prenatal care self-reported during recruitment. Prenatal care use validated using patient medical records. Women were followed for 1 year, with monthly phone calls to ascertain information regarding health care use. |

ACA, Affordable Care Act; CHC, Chelsea Health Care Center; CPT, Current Procedural Terminology; DM, Diabetes Mellitus; FC, family connects; GDM, gestational diabetes; HEDIS, Health care Effectiveness Data and Information Set; LAMB, Los Angeles Mommy and Baby; MA, Massachusetts; MCO, Managed Care Organization; MIC, Maternal and Infant Care; NMH, Northwestern Memorial Hospital; OUD, opioid use disorder; PEC-S, preeclampsia with severe features; PNC, Prenatal Care; QEC, Queen Emma Clinic; RCT, randomized control trial; UDS, Uniform Data Systems.

Table 2.

Study Findings

| Authors (year) | Predictors | Outcome | Statistical methods | Descriptive data | Main results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attanasio and Kozhimannil (2017) | Provider level: perceived discrimination during the childbirth hospitalization based on (1) race, ethnicity, cultural background, or language; (2) health insurance situation; or (3) a difference of opinion with caregivers about the right care for yourself or your baby. Responses were dichotomized as ever/never experiencing each type of discrimination and any versus none. | Postpartum visit attendance with a maternity care clinician in the 8 weeks after birth | Multivariable logistic regression to calculate aORs for each discrimination measure. Analyses weighted to be nationally representative. | Around 91.1% attended the postpartum visit. Racial and/or ethnic minorities, uninsured mothers, first-time mothers, and those with hypertension or diabetes were more likely to report perceived discrimination. Approximately 24% reported some form of perceived discrimination during the intrapartum hospitalization. | Any discrimination associated with over twice the odds of not attending a postpartum visit (aOR 2.28, 95% CI: 1.39–3.73); insurance-based discrimination with 2.70 (95% CI: 1.55–4.69), race-based discrimination with 2.11 (95% CI: 1.15–3.87), and discrimination due to a difference of opinion about care with 1.86 (95% CI: 1.06–3.27) times the odds of nonattendance. |

| Battarbee and Yee (2018) | Patient level: age, race/ethnicity, primary language, and insurance status; presenting to care >24 weeks gestation; method and timing of diagnosis and type of GDM management, birth complications, including route of delivery and neonatal admission to the neonatal intensive care unit. Provider level: resident and fellow involvement in care |

Returning for postpartum care in the first 4 months | Bivariable analyses used Student's t-test and Fisher's exact test to compare cases/controls. Factors associated with postpartum follow-up with p < 0.1 were retained in the multivariable logistic regression model. | The sample was 26.5% Hispanic, 24% non-Hispanic white, 21.8% non-Hispanic black, 10.8% Asian, and 16.8% other or unknown race/ethnicity. About 39% of the sample was Medicaid insured. Around 82% of the sample returned for a postpartum visit, and of these women, 49.8% completed a 2-hour glucose tolerance test. | In adjusted models, Medicaid insurance (OR 0.3, 95% CI: 0.2–0.6), late presentation to prenatal care (OR 0.4, 95% CI: 0.2–0.7), and preterm delivery (OR 0.4, 95% CI: 0.2–0.7) were associated with decreased odds of postpartum care, and Asian race (OR 4.2, 95% CI: 1.1–15.3) was associated with increased odds of postpartum care. |

| Bennett et al. (2014) | Patient level: mothers considered having a complicated pregnancy if they had ≥1 of the following: GDM, pregestational DM, or hypertensive disorders in pregnancy. The first pregnancy or first complicated pregnancy was the index; if a woman had multiple complications in the same pregnancy, she was classified into each group for comparison. The comparison group contained mothers without any of the above complications. | An obstetric postpartum visit within 3 months | Multivariable logistic regression. A sensitivity analysis added births defined by other ICD-9-CM and CPT codes, yielding 4% more deliveries; used race/ethnicity from Medicaid claims and zip code at delivery to link the data with the 2000 Census. | About 87.2% had Medicaid and 44.3% identified as African American. Rates of hypertensive disorders, GDM, and DM were 17.0%, 9.1%, and 1.4%. Among those with Medicaid, 65% with a complicated pregnancy and 61.5% of comparison mothers attended the postpartum visit. | Among women with Medicaid, predictors of a 3-month visit included white race (aOR 1.22) or Hispanic ethnicity (aOR 1.48), chronic hypertension (aOR 1.28), preeclampsia (aOR 1.30), GDM (aOR 1.14), cesarean delivery (aOR 1.29), depression (aOR 1.22), and Medicaid eligibility due to pregnancy (aOR 1.16). Predictors of nonattendance included other mental disorders in pregnancy (aOR 0.81) and drug or alcohol use (aOR 0.71). |

| Bermúdez-Parsai et al. (2012) | Patient level: acculturation measured by the Bicultural Involvement Questionnaire, which asks questions like “How much do you enjoy your native music?” and “How much do you enjoy American TV programs?” Answers from 1 = “not at all” to 5 = “very much.” Two subscales: Hispanicism indicates level of socialization to Latino way of life, versus Americanism indicates affinity for Anglo-American way of life. Both scores used to calculate 5 levels: assimilation, separation, alienation, moderation, and biculturalism. | Attendance at a postpartum visit during the intervention | Multivariable logistic regression | Average age was 27 years; 84% were first-generation immigrants and 81% were of Mexican heritage. About 85% of families lived under the FPL. Around 11% had attended or graduated from college. Most women were not working (76%) and 46% were single, while 28% were married and 16% were living with a partner. About 37% were “Separates”; 34% were “Bicultural”; about 20% of the sample was represented by “Moderates.”; the smallest groups were “Assimilated” and “Alienated” (4 and 5%). | Adjusted for confounders, mothers in the Separation group were 45% less likely (aOR 0.55, 95% CI: 0.32–0.96) than Bicultural mothers to attend the postpartum visit, and those in the Assimilation group were 68% less likely (aOR 0.32, 95% CI: 0.09–1.15) than Bicultural mothers to attend the visit. |

| Bryant et al. (2006) | Patient level: demographic variables such as age, race/ethnicity, and parity; family size, education, time spent doubled up in housing, income, receipt of Aid to Families with Dependent Children, preterm delivery, presence of a chronic health condition, and domestic violence during the pregnancy Provider level: trouble understanding the provider Health system level: appointment reminders |

Visit attendance was defined as self-report of a visit to a doctor or midwife since the birth of the baby | Bivariate analyses used chi-squared tests between patient characteristics and postpartum visit attendance. Multiple logistic regression used to model predictors of postpartum visit attendance. Data were analyzed using weighted means, proportions, regression coefficients, and standard errors. | About 75.7% identified as black, 12.2% as white, and 10.9% as Hispanic. Around 79% were <30 years old, 60% were multiparous, and 65.2% had ≥high school education, and 40.6% had a chronic health problem. About 72% of pregnancies were reported as unintended. Approximately 86.5% attended the postpartum visit; visit attendance ranged from 74% to 100% by project area (p-value of 0.03). About 80.8% of white, 86.2% of black, and 91.1% of Hispanic women had a postpartum visit. | A chronic health condition was associated with 2.49 times (95% CI: 1.07–5.80) the odds of a visit. Having ≥2 housing moves in pregnancy (aOR 0.35, 95% CI: 0.18–0.67), having trouble understanding the provider (aOR 0.65, 95% CI: 0.43–0.99), and having difficulty with transportation to visits (aOR 0.59, 95% CI: 0.04–0.89) were negatively associated with a visit. Receipt of an appointment reminder was associated with 2.37 times (95% CI: 1.40–4.02) the odds of a visit. |

| Buchberg et al. (2015) | Patient level: demographic variables and behavioral variables included race/ethnicity, level of education, use of public assistance, ART adherence, alcohol, tobacco, and drug use; psychosocial measures included the CES-D, ISEL-12, and The Internalized Stigma of AIDS Tool. | Adherence to obstetric care defined as attending an appointment within 3 months after birth | Two sample t-tests used to test the differences in variables with the outcome. Statistical significance defined by a two-sided p-value <0.05. | The mean age of women in the baseline sample was 28.2 years, with the majority being African or African American (77.1%), being unemployed (76.7%), and receiving some form of public assistance. Postpartum obstetric appointments were attended by 71.4% within 3 months, and only 57.1% attended a primary care appointment within 6 months. About 14.3% attended neither an obstetric nor a primary care visit. | Higher CD4 count at delivery (median [IQR]: 512 [364–746] vs. 369 [285–637]; p = 0.04) and fewer other children (mean – SD: 1.13 – 1.26 vs. 2.40 – 1.96; p = 0.03) were associated with postpartum care by 3 months. No statistically significant differences were observed in demographic characteristics (i.e., race, age, and use of public assistance) between the women who attended the postpartum visit compared to those who did not. |

| DeSisto et al. (2020) | Patient level: primary predictor was Medicaid eligibility, either as continuous Medicaid eligibility or pregnancy-only eligibility determined using status codes on Medicaid eligibility file. Pregnancy-only Medicaid ends at the beginning of the month following the 60th day postpartum, so these mothers lose eligibility between 61 and 90 days postpartum; additional predisposing, enabling, and need factors considered age, marital status, educational attainment, race/ethnicity, previous live births, adequacy of prenatal care use, tobacco use during pregnancy, cesarean delivery, hypertension, diabetes, preterm delivery, and plurality (singleton or multiples). | Postpartum visit defined using a modified HEDIS measure: used ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes for a postpartum visit, intrauterine device insertion, or a bundled service through 12 weeks after birth using (1) codes for routine postpartum care and (2) routine postpartum care, excluding bundled codes (since bundled codes may be used in the immediate postpartum for the delivery, while not actually including a postpartum visit). | Chi-square tests used to test differences in receipt of care between the 2 groups; stratified analyses of crude relationship between Medicaid eligibility and postpartum care by maternal characteristics. Risk differences and 95% confidence intervals calculated using an adjusted binomial model | Around 25% of the sample had pregnancy-only Medicaid versus 75% had continuous Medicaid. The sample was 55.6% non-Hispanic white, 17.4% non-Hispanic black, 13.4% Hispanic, and 13.7% other race/ethnicity. Women with continuous Medicaid were younger, less likely to be married, and more likely to use tobacco. About 81.9% of those with pregnancy-only Medicaid attended a postpartum visit versus 87% of those with continuous Medicaid (or 41.9% vs. 53.2%, respectively, if bundled codes excluded) | Those with continuous Medicaid eligibility were more likely to use postpartum care. Mothers with pregnancy-only Medicaid had a postpartum visit rate 6.27% points lower (95 CI: −6.82 to −5.72) than for those with continuous eligibility. Mothers with no prenatal care had a postpartum visit rate 30.56% points lower (95% CI: −34.4 to −26.7) than for those with adequate prenatal care. Additional predictors of not receiving postpartum care included younger age (≤24), lower education (< high school/GED), race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic black and other race/ethnicity mothers vs. non-Hispanic white mothers), parity (≥3 previous live births vs. 0), tobacco use, cesarean delivery, having had prepregnancy or gestational hypertension, preterm delivery, and multiple gestations. |

| DiBari et al. (2014) | Patient level: sociodemographic factors included race, age, marital status, income, and education, insurance type, prenatal care use, care received before pregnancy, pregnancy intendedness, preterm birth, low birthweight, and whether the infant attended a newborn visit | Postpartum care visit attendance | Chi-squared analyses tested differences in postpartum care use by potential predictors. Multivariable logistic regression was used to identify predictors of postpartum care use. Survey weights were used to account for the sampling design and nonresponse. | The sample of mothers was predominantly (61%) Hispanic, between 19 and 39 years of age, married, low income, and with a high school-level education or less. About 91.7% attended a postpartum visit. Reasons for not attending the postpartum visit reported on the survey included that they felt fine, were too busy with the baby, had other things going on, and felt there was no need for the visit. | Hispanic mothers were significantly less likely to miss the postpartum visit versus non-Hispanic white mothers (OR 0.57, 95% CI: 0.38–0.87). Mothers 30–39 years of age (OR 0.68, 95% CI: 0.51–0.91) were less likely to miss the visit compared to mothers 19–29 years of age. Mothers with income <$20,000 were nearly 3 times as likely to miss the visit (OR 2.89, 95% CI: 1.43–5.82) compared to those with income >$100,000. Unmarried mothers and those with lower pregnancy intendedness were more likely to lack a visit. Mothers who did not attend prenatal care were more than 3 times as likely to lack a postpartum visit (OR 3.08, 95% CI: 1.68–5.63). When insurance status replaced income in the model, mothers with Medi-Cal insurance were over twice as likely to lack a visit compared to those on private insurance (OR 2.19, 95% CI 1.54–3.11). Hispanic ethnicity, maternal age, marital status, pregnancy intendedness, and prenatal care use remained significant. |

| Dodge et al. (2019) | Health system level: the intervention involved trained nurses offering mothers 1–3 postnatal home visits for support, clinical assessment, and referrals, as needed. They use motivational interviewing techniques to help families clarify their needs in 12 risk domains and facilitate referrals to appropriate community resources. | Mother's report at infant age 6 months of attendance at 6-week postpartum physician visit | Logistic regression models with exact 2-tailed p level and 95% confidence intervals; used multiple imputation for missing values; accounted for pretreatment differences using ordinary least-squares multivariate regression predicting outcomes from random assignment. | About 65% of the sample used Medicaid or were uninsured. Around 56% of mothers were white, 38% were black, 5.7% were other race/ethnicity, and 28.5% were Hispanic | Around 90.3% of mothers in the intervention group had a 6-week postpartum visit versus 83.8% of control mothers (b = 6.44; 95% CI: −0.62 to 13.51). |

| Gregory et al. (2020) | Patient level: health risks at enrollment (DM, hypertension, preterm birth, low birth weight), self-rated health; demographics (age, educational attainment, income, and marital status), social support, depression, stress, and insurance type Provider level: a personal relationship with a doctor or nurse (“A personal doctor or nurse is a health professional who knows you well and is familiar with your health history…Do you have one or more persons you think of as your personal doctor or nurse?”) Health system level: a usual place of care (“Is there ONE place that you USUSALLY go to when you are sick or need advice about your health?”) |

Postpartum visit: “After the birth of your most recent child, did you have your 6-week postpartum checkup?” Also asked about general preventive care after this visit: “Since the birth of your most recent child, have you visited a health care worker for a checkup?” Outcome was a dichotomous variable of affirmative response to both questions | Factors were compared between women with and without health risks using Fisher's exact tests and Student t tests; multivariable log-linear Poisson regression with robust standard errors to evaluate the association of interconception care with risk category and predictors. Relative risks and 95% CIs presented. Sensitivity analysis restricted to follow-up health care use in a narrower window (6–10 months). | The majority of the sample was non-Hispanic black (84%). Less than half (43%) completed education beyond high school and about half reported household income <$20,000 (50%), being married or living with a partner (55%), and current unemployment (54%). Almost all women reported a usual place of care (94%) and a majority reported having a personal doctor or nurse (69%). Most women had Medicaid insurance (70%) and 6% reported no insurance. About 74% reported attending the 6 weeks postpartum visit | Two enabling factors were associated with interconception visit use: having a personal doctor or nurse (RR 1.38, 95% CI: 1.11–1.70) and non-Medicaid insurance (1.64, 95% CI: 1.09–2.56). Results did not significantly change in sensitivity analyses. History of prepregnancy or prenatal hypertension was associated with slightly increased postpartum visit use, but not attendance at a second checkup (no estimates presented). |

| Heberlein et al. (2020) | Health system level: CenteringPregnancy (group prenatal care) versus individual prenatal care: defined as (1) any group attendance versus no group attendance and (2) attendance at ≥5 group sessions versus ≥5 prenatal visits (minimum threshold analysis where this cohort includes crossovers to individual care attending fewer than 5 group sessions) | Postpartum visit attendance was defined as any postpartum visit occurring between days 21 and 56 postpartum using the National Committee for Quality Assurance's HEDIS measure | Logistic regression models examined the impact of group care on the outcome with the matched group and individual care cohorts. Used propensity scores to match women participating in group care to those in individual care; also used a preferential within matching technique to match those with similar scores within the same practice to account for the nested nature of data within sites. | Group care participants were younger, had lower levels of education, and were more likely to be Hispanic (12.7% vs. 6.1%). This group had more primiparous mothers (55.1% vs. 36.4%), those starting prenatal care earlier, and those with higher levels of prenatal care use. Group care participants were less likely to have a BMI >45, prepregnancy DM/GDM or hypertension, or a previous preterm birth. Group care participants had lower rates of cesarean deliveries, preterm birth, or low-birth-weight babies, and were more likely to be breastfeeding at discharge. Before matching, 68.6% of the mothers in group care and 62.4% of the mothers in individual care attended a postpartum visit. | After propensity score matching, women who attended any group care visit versus no group care were equally likely to attend the postpartum visit (68.6% vs. 67.6%, p = 0.58). Among mothers who attended at least 5 prenatal visits, group participants had higher rates of postpartum visit attendance compared to individual care participants (71.5% vs. 67.5%, p < 0.05). |

| Howell (2010) | Provider level: Satisfaction with the clinician: inferred based on a 5-point Likert scale response to a question used in hospitals that rates overall care and concern shown by the provider. Because the response distribution was skewed, this measure was dichotomized into a rating of excellent versus not excellent. | Postpartum visit attendance in the first 3 months | Multivariable logistic regression models | Around 15% black/African American, 26% Hispanic/Latina, 50% white, and 9% other race/ethnicity. Around 30% were insured through Medicaid and 27% had a high school or less education level. Women who rated their clinician as excellent were more likely to be older, white, have >high school education, and not use Medicaid insurance. These women were also less likely to report poor self-assessed health and were more likely to have a regular doctor and more access to care and feel better prepared for the postpartum experience. | Rating a clinician as excellent was strongly associated with attending the postpartum visit within 3 months (p < 0.001). |

| Hulsey et al. (2000) | Patient level: early prenatal care (in the first 13 weeks); pregnancy intention; feelings about the pregnancy at the time of the prenatal interview and when she first found out about the pregnancy (Likert Scale from very happy to very unhappy); and if they had ever considered abortion. | Postpartum visit nonattendance: if the participant did not keep the visit within the 12 weeks following delivery | Multivariable logistic regressions used to identify independent associations between study variables and the outcome | Predominantly African American (83%), 20–35 years old (71%), single (82%), unemployed (73%), and had ≥12 years of education (60%). Around 55% had early prenatal care, 82% had an unintended pregnancy, and 33% considered having an abortion. About 83% attended the postpartum visit. | Mothers with ≥3 previous deliveries were 3 times as likely to miss the postpartum visit compared to those with 1–2 previous deliveries (aOR 3.04, 95% CI: 1.03–9.01) and unemployed mothers were 2.7 times as likely to miss their visit (95% CI: 1.00–7.42) versus employed. |

| Jones et al. (2002) | Patient level: the ARSMA II was used to determine acculturation level; demographics (age, marital status, education level, religious preference, country of origin, and generation in the United States); maternal pregnancy history; trimester of entry to prenatal care and number of prenatal visits; pregnancy complications; gestational age/birthweight of the infant; and tobacco, alcohol, and substance use. Pay category data were collected electronically using medical record numbers: self-pay, commercial carrier, and government subsidized. | Attendance at a 2-week postpartum visit, 3-month family planning checkup, and 1-year follow-up visit | Descriptive statistics, chi-square tests, Pearson product-moment correlations, Kendall tau correlations, Spearman rho correlations, and multiple regression analyses | Around 39% of the sample had a payment type classified as self-pay, 3% as commercial pay, and 58% as government subsidized. The majority were married or living in a stable relationship (71%). About 56% had an 8th grade education or less. Approximately 88% were first generation in the United States. Most of the sample were Very Mexican on the acculturation scale (78%). A majority entered prenatal care in the first (44%) or second (45%) trimester. Around 77% returned for a postpartum checkup at 2 weeks; 32% for a 3-month checkup; and 22% for an annual visit. | There were no significant differences in return rate for any visit type based on pay category. Women with lower gravidity, who were first generation, and who were less acculturated were more likely to return for at least one family planning visit. These 3 variables accounted for 10% of the variability in return for family planning visits. |

| Kentoffio et al. (2016) | Patient level: maternal age, educational attainment (<completion of high school versus high school diploma or greater), insurance type (private insurance, Medicare, Medicaid, free care, or self-pay), and baseline BMI. To account for neighborhood differences, patient addresses were geocoded and the median household income at the census tract level was abstracted. | Receipt of a postpartum visit at any point following delivery | Chi-square tests and Fisher's exact tests for unadjusted analyses; ANOVA for continuous outcomes. For adjusted analyses, logistic regression and Poisson models used with random effects to account for clustering from repeated pregnancies within individuals. | Refugee and Spanish-speaking immigrants less likely to have completed high school than U.S.-born controls. Only 5.9% did not have health insurance, with no difference between groups. Among refugees, the most common countries of origin were Somalia, Bhutan, Iraq, and Haiti. Refugees and immigrants had delayed initiation of prenatal care: 20.6% of refugee women and 15% of immigrant women had their first visit >12 weeks, versus 6% of controls. Refugees had fewer prenatal care visits than controls, but once in care were more likely to receive postpartum care | Refugees (73.3%) and immigrants (78.3%) were more likely to have had recommended postpartum care than controls (54.8%, p < 0.001). After adjustment, both refugee (aOR 2.00, 95% CI: 1.04–3.83) and Spanish-speaking immigrant (aOR 2.79, 95% CI: 1.72–4.53) women were more likely to attend a postpartum care visit compared to English-speaking controls. When examining only the first pregnancy, associations were generally stronger or similar. |

| Kogan et al. (1990) | Patient level: maternal age, education, parity, ethnicity, primary language, marital status; adequacy of prenatal care based on entry to care and number of visits, type of delivery, length of hospitalization, birth outcomes, length of pregnancy, NICU transfer, birth weight, and, beginning in 1986, source of payment (no insurance, commercial, or state funded). Health system level: site of prenatal care |

Postpartum visit within 2–6 weeks after delivery | Multivariable logistic regression | About 24% of the sample was teens, 48% had a < 12th grade education, 62% were unmarried, and 59% were a racial or linguistic minority. During the 3 study years, 78% of mothers who received care at an MIC office returned for a postpartum visit: 63% of mothers with inadequate prenatal care use returned for a follow-up versus 76% of mothers with intermediate care and 86% of those with adequate care. | Mothers with inadequate prenatal care were 2.8 times less likely to return for a postpartum visit compared to those with adequate care. White mothers were 1.2 times as likely to return for a visit compared to Hispanic mothers. Primiparous mothers were 1.7 times as likely to return as multiparous mothers. Publicly insured mothers were less likely to miss a postpartum visit compared to commercially insured. When government insurance was included in the model, no differences remained for Hispanic/black versus white mothers. |

| Levine et al. (2016) | Patient level: demographics, medical and obstetrical history, and labor, delivery, and postpartum information (specific variables not listed) | Attendance at the 6-week postpartum visit | Chi-square analyses and Fisher's exact tests were used to compare categorical variables and logistic regression was used to calculate unadjusted ORs. A two-sided p-value of <0.05 was used for statistical significance. | More than 75% of the sample was African American and just over half were nulliparous and obese. About 8% of the sample also had GDM or pregestational DM and 3.1% had chronic hypertension. Around 52.3% of the sample attended the postpartum visit. | Factors associated with lower postpartum visit use were African American race (OR 0.37, 95% CI: 0.18–0.77), attending <5 prenatal visits (OR 0.44, 95% CI: 0.20–0.97). Those with diabetes (OR 4.00, 95% CI: 1.09–14.66) and cesarean deliveries (OR 2.61, 95% CI: 1.40–4.88) had higher use. |

| Masho et al. (2018) | Patient level: age, race/ethnicity, and education, region of residence in Virginia, antenatal or prenatal care attendance, pregnancy complications, depression, tobacco use, drug abuse/dependence, alcohol abuse/dependence, delivery type, and birth outcome variables. Pregnancy complications included GDM, preeclampsia, eclampsia, hypertension, anemia, cervical incompetence, uterine inertia, premature separation of placenta, and placenta previa. Mode of delivery; and birth outcome categorized into term normal weight; preterm normal weight; term low birth weight; and preterm low birth weight. Health system level: type of health care system most used for prenatal care services |

Postpartum visit attendance defined by medical claims data using codes from the ICD-9-CM for routine postpartum follow-up (i.e., V24.2) 3–8 weeks postdelivery. | Chi-square tests and p-values to test for differences in proportions of correlates between postpartum attendance groups. All variables were tested for interaction. Logistic regression was used for crude and aORs and 95% CI. | Around 68% were 20–29 years old, 56% were white, and 51% had a high school education. The majority had vaginal delivery (67%) and gave birth to a normal weight and full-term baby (87%). About 49% of the sample attended the postpartum visit. | Black mothers (aOR 1.22, 95% CI: 1.03–1.44) and mothers of other race/ethnicity (aOR 1.26, 95% CI: 1.04–1.54) had higher odds of attending the visit. Those with no prenatal care were less likely to attend the postpartum visit (aOR 0.43, 95% CI: 0.34–0.55). Mothers who received prenatal care at a Hospital (aOR 1.41, 95% CI: 1.09–1.82), Health Department or FQHC, (aOR 1.76, 95% CI: 1.17–2.63) were more likely to attend compared to those who received care from private locations. Mothers with pregnancy complications had 22% higher odds of attending compared to those without (aOR 1.22, 95% CI: 1.05–1.42). Tobacco users had lower odds of attending (aOR 0.84, 95% CI: 0.72–0.98). |

| Ortiz et al. (2016) | Patient level: age, race/ethnicity, medical and insurance information Provider level: type of health care provider |

Postpartum visit and glucose test as documented in the hospital medical record | Descriptive statistics for the overall sample and by status of postpartum care receipt; Pearson's chi-square and Fisher's exact tests for associations between categorical variables and postpartum care; p-value of <0.05 for statistical significance. | The majority were Hispanic (60%) with 16% identifying as American Indian, 12% as other race/ethnicity, and 11% as non-Hispanic white. About 43% had no insurance and 39% had public insurance. About 70% had an MD health care provider and 30% had an Advanced Practice Registered Nurse provider. Postpartum visits occurred from 1 to 14 weeks postpartum with 54.6% of the sample attending a visit. Since 17% had the test done before the 6-week postpartum visit, only 19% of the overall sample had a proper GDM postpartum standard of care completing the test after 6 weeks postpartum. | Maternal age was not associated with having a postpartum visit (p = 0.212). Non-Hispanic white mothers were significantly more likely to attend a postpartum visit at the hospital (91%) compared to mothers who identified as other race/ethnicity (67%), Hispanic (53%), or American Indian (25%) (p < 0.01). Privately insured mothers were also more likely to attend a visit (88%) versus publicly insured (47%) or uninsured (48%) mothers (p < 0.01). |

| Parekh et al. (2018) | Patient level: race, ethnicity, region, and year | HEDIS measure of postpartum care within 21–56 days after delivery | Frequency-weighted multivariable logistic regression used for average predicted probabilities and aORs. | Nearly half of the sample were white, nearly one-third were black, about 3% were Asian, and 15% were Hispanic. About 86% met the HEDIS measure for prenatal care timeliness and 69% for frequency of prenatal care. 61% attended the postpartum visit. | Compared to black mothers, white and Asian mothers had higher odds of postpartum care (aOR 1.33 and 2.12, respectively). No differences in postpartum care were observed by Hispanic/Latina ethnicity. As MCOs performed worse postpartum care rates, disparities between black and white mothers widened. |

| Patton et al. (2019) | Patient level: Medicaid coverage before and after expansion; length of Medicaid enrollment following delivery; age, race, ethnicity, and Medicaid eligibility category (pregnancy medical assistance, TANF, disability, and other); substance use disorders other than OUD, tobacco and alcohol use in pregnancy, use of MAT in pregnancy, hepatitis C virus, HIV, and psychiatric disorders | Postpartum visit attendance within 60 days defined by ICD-9 codes | Kaplan-Meier curves and log-rank test with censoring at 300 days postpartum used to compare time to disenrollment between preexpansion and postexpansion groups; multivariable Cox proportional hazard regression models were used to evaluate predictors of contraceptive use and postpartum visit attendance. ORs and 95% confidence intervals. | A greater proportion of the mothers in the postexpansion group remained enrolled at 300 days postpartum versus the preexpansion group (87% vs. 81%). Within 60 days postpartum, 23.5% of mothers in the preexpansion group and 21% in the postexpansion group started contraception. About 15% of preexpansion mothers and 16.4% of postexpansion mothers attended the postpartum visit. | Medicaid expansion was not associated with any difference in the odds of postpartum visit use (OR 1.1, 95% CI: 0.8–1.4). Mothers in both groups who were not disenrolled during the 300-day follow-up period were more likely to have attended a visit (OR 1.6, 95% CI: 1.04–2.4). Substance use disorders other than OUD were associated with lower attendance (OR 0.6, 95% CI: 0.4–0.8). |

| Rankin et al. (2016) | Patient level: age, race/ethnicity, geographic residence, and percentage of woman's zip code living in poverty | Postpartum care defined to include (1) routine postpartum care or (2) services recommended as part of postpartum care, including gynecological examination; depression screening; other screenings and risk assessments; vaccinations; and family planning; or (3) visits with ICD-9-CM codes for routine medical care, follow-up or aftercare, or CPT codes for preventive care, evaluation, and management, consultation, or all-inclusive FQHC visits. The timing of each visit was categorized as <21, 21–56, and 57–90 days. | Univariate statistics were estimated for the timing of the first visit. Receipt, frequency, and timing of visits are estimated by maternal sociodemographic characteristics. | Around 95,183 visits to 55,577 women were identified. Routine visits typically occurred 21–56 days postpartum. Almost 19% of the sample was teens. Non-Hispanic African-American and Hispanic/Latina mothers made up 32.5% and 20.3% of the sample. About 77% resided in an urban core and 30% resided in zip codes where ≥20% of residents had incomes ≤ FPL. First visits typically occurred at 1 or 6 weeks. Around 23% attended an early visit, plus ≥1 more visit during the first 90 days. About 81% had ≥1 encounter in the first 90 days. Among those with visits, 60.2% had >2 visits and 33.5% had the first <21 days. | African-American mothers were least likely to receive any postpartum care (73.6%), versus 86.5% of non-Hispanic white mothers and 81.3% of Hispanic/Latina mothers. Among those with visits, 66.5% of white mothers had ≥2 visits versus 52% of African-American mothers. Those living in an urban core (78.5%) versus more rural areas (90%) were less likely to have postpartum care. Mothers in urban cores had the lowest proportion with multiple visits and the highest proportion with a first visit >8 weeks postpartum. Those residing in areas with ≥20% of residents below the poverty line had lower receipt, frequency, and early (<21 days) first visit rates, than mothers in less poor areas. |

| Schwarz et al. (2017) | Patient level: Women with pregnancies affected by diabetes were identified if an ICD-9 code for diabetes appeared on one or more occasions in the peripartum: women were categorized as having (1) preconception DM (2) GDM or (3) no diabetes. Other factors included maternal age at delivery, race/ethnicity, primary language, residence in a PCSA, and delivery type | Postpartum visit attendance defined 3 ways: (1) HEDIS Postpartum Care Measure for postpartum care 21–56 days after delivery; (2) a broader definition in the same time period that includes family planning or provision of contraception; and (3) the broadest definition including any office visit or contraceptive service across 0–99 days postpartum. | Differences in maternal demographic and service delivery factors by DM status were examined using chi square tests. Multivariable logistic regression used to assess the likelihood of receiving postpartum care among women with preconception DM or GDM versus women with no known DM. | Around 5.7% had preconception DM, 9.0% had GDM, and 85.3% had no diabetes. Those with diabetes were older, and more likely to be Latina, speak Spanish, and have a cesarean delivery. Postpartum visit use was higher for those with either form of diabetes versus no diabetes (55% vs. 48%, p < 0.001). When using the broadest definition of postpartum care, 89% of women with preconception DM and 88% of women with GDM received postpartum care within 99 days. | The adjusted odds of women attending a postpartum visit or receiving other postpartum care were at least 20% higher for women with preconception DM (aOR 1.22, 95% CI: 1.18–1.27) or GDM (aOR 1.24, 95% CI: 1.20–1.28) than women without known DM using the HEDIS measure of postpartum visit attendance, with increasing aORs as the definition of postpartum care was broadened. |

| Shi et al. (2004) | Health system level: Site-level racial/ethnic background of health center users; no. of patients with incomes at or below the FPL; rural versus urban center location; perinatal service capacity based on the total number of prenatal care users per full-time equivalent OB/GYN. | Any postpartum care within 8 weeks of birth | Rates of postpartum care by racial/ethnic group from 1998 to 2001, and chi-squared tests of statistical significance. Pooled regression analyses using a mixed linear model to account for the dependence of repeated measurements within each center. Missing predictor variable data imputed for a specific community health center based on a different year's data. | Hispanics were the largest proportion of prenatal care users, followed by black, white, American Indian/Alaskan Native, and API women. Across 1998–2001, 72.8% received postpartum care: API mothers were most likely to receive care (78.9%), followed by Hispanic (74.3%), white (71.5%), black (68.9%), and AI/AN (67.5%) mothers. | Community health centers with a higher proportion of first trimester prenatal care users had higher rates of postpartum care use (a 1% increase per 5% increase in prenatal care users). Poverty status positively predicted timely postpartum care as did centers with a higher ratio of patients to OB/GYNs (lower capacity). |

| Smith et al. (1990) | Health system level: providing a coupon for infant formula or gift for the mother (costume jewelry) as an incentive | Postpartum visit attendance between 4 and 6 weeks postdelivery | Randomized participants to one of three groups: Group A—control; Group B—infant formula coupon; and Group C—gift for mother; used chi-square tests for differences | Around 36% of those randomized were in Group A; 28% in group B; and 36% in group C. Mean age was 15.7 years with a range from 12 to 19. Around 43% was black, 45% Hispanic, and 12% white. About 74% were single. Approximately 13% of participants lived within 1 mile of the clinic versus 58% in 1–5-mile radius and 29% residing 5–10 miles of the clinic. | Postpartum visit attendance was highest in group B (37%), relative to group A (22%) and group C (23%, p < 0.003). black mothers were more likely to return for postpartum care (31%) versus Hispanic (26%) and white (14%) mothers (p < 0.02). |

| Stevens-Simon et al. (1994) | Patient level: Medicaid status, gravidity, parity, prenatal care, and educational status Health system-level: providing an incentive (Gerry “Cuddler” baby carrier gift) |

Postpartum examination 6–12 weeks after delivery | Student t-test and chi-square tests; stepwise multivariable logistic regression analysis | Mean age of participants was ∼17 years. About 54% of participants were white, about 27% were black, and 17% were Hispanic. Around 88% of participants were covered by Medicaid insurance. About 15% of participants reported transportation challenges, and slightly under half were in school at the time of delivery. | Mothers in the incentive group were more likely (82.4%) than those in the nonincentive group (65.2%) to return for a postpartum visit by 12 weeks (p = 0.003) and within 8 weeks (71.3%) versus those randomized to the nonincentive group (51.5%; p = 0.002). Medicaid coverage was associated with lower postpartum visit attendance (p = 0.04), while being primiparous, engaging in prenatal care, and being in school at the time of delivery were associated with higher visit attendance (<0.05). |

| Tandon et al. (2013) | Health system level: CenteringPregnancy (group prenatal care) | Postpartum checkup in the first 6 weeks after delivery | Chi-square tests | Average age was 27.5 years. Almost 21% were working at the time of baseline interview. About 43% of mothers in group and 37% in traditional prenatal care were single. In each group, 31% had ≥high school education, and 98% were born outside the United States. Over 90% in both groups reported Spanish as the primary language spoken at home. In both groups, the largest percentage were born in Central America. | CenteringPregnancy participants were more likely (99%) than traditional prenatal care participants (94%) to have had a postpartum checkup before 6 weeks (p = 0.04) |

| Taylor et al. (2020) | Patient level: insurance status defined as Medicaid, uninsured, or commercial, based on the primary payor source at delivery | Health care use: ICD codes to determine the number of well-woman visits in the 2 years before pregnancy; timing of prenatal care; adequacy of prenatal care; number of emergency department visits during pregnancy; and 6-week postpartum care visit. | Chi-square and multivariable regression models to estimate the aORs or rate of each outcome by insurance status. | Around 30% Hispanic, 27% non-Hispanic black, 28.2% non-Hispanic white, and 14.9% other race/ethnicity. About 46% had commercial insurance, 51.9% were Medicaid insured, and 1.9% were uninsured. Mothers who were Medicaid insured or uninsured were more likely to be younger, have comorbid diabetes, live in neighborhoods with higher poverty and lower education, and less likely to be non-Hispanic white than privately insured mothers. They had fewer well-woman visits before pregnancy and more ED visits in pregnancy. | Compared with commercially insured mothers (90%), Medicaid-insured mothers (49.2%, OR 0.65, 95% CI: 0.58–0.74) and uninsured mothers (41.2%, OR 0.42, 95% CI: 0.34–0.51) were significantly less likely to have a 6-week postpartum visit. Compared with non-Hispanic white mothers, Hispanic mothers were significantly less likely to attend a postpartum visit (OR 0.70, 95% CI: 0.64–0.76). |

| Thiel de Bocanegra et al. (2017) | Patient level: race/ethnicity, primary language, age at delivery, having ever resided in a PCSA, and delivery method | Receipt of postpartum care 21–56 days after delivery | Pearson chi-square tests and multivariable logistic regression | The majority of participants were Latina (67.4%). Half spoke English and 46% reported Spanish as their primary language. Approximately 58% were 20–29 years of age at delivery, 33.9% had cesarean deliveries, and 64.7% resided in a PCSA during their postpartum period. Around 49.4% of the sample attended the postpartum visit. | Black mothers had 27% lower odds of attending a postpartum visit versus white mothers (aOR 0.73, 95% CI: 0.71–0.76). Mothers <20 years old had lower odds of a versus those 20–29 years of age (aOR 0.82, 95% CI: 0.80–0.85). Mothers living in PCSAs were less likely to attend the visit (aOR 0.88, 95% CI: 0.86–0.89), and mothers with a cesarean delivery were less likely to attend the visit (aOR 0.81, 95% CI: 0.80–0.83). Mothers whose primary language was Spanish (aOR 1.65, 95% CI: 1.61–1.69) or “Other” (aOR 1.14, 95% CI: 1.08–1.21) had greater odds of returning for a visit versus those whose was English. |

| Trudnak et al. (2013) | Health system level: CenteringPregnancy (group prenatal care) versus individual prenatal care | Postpartum visit attendance by 6 weeks | Chi-square tests and multivariable logistic regression model | The majority of women were of Mexican origin, married, employed, did not smoke, and had a prepregnancy BMI in the normal weight range. | There was an increased odds of attending the 6-week postpartum visit among mothers in CenteringPregnancy (86.7%) versus those in individual care (74.6%, aOR 2.20, 95% CI: 1.20–4.05). |

| Tsai et al. (2011) | Health system level: Pre-post comparison of introducing a “Postpartum Follow-up Initiative” provided time and date of postpartum visit before hospital discharge and an appointment card with a congratulatory letter. At the patient's postpartum visit, a picture was taken with her baby and presented in an album with the hospital's logo when she returned for her second visit. | No. of postpartum follow-up visits | t-Test and chi-square tests to compare demographic characteristics for continuous and categorical variables, respectively. Sample size calculations were generated for the preintervention and postintervention groups based on an expected difference of 25% in postpartum follow-up rates. | Around 106 women were included in the preintervention group and 115 were included in the postintervention group. | Postpartum follow-up rates increased significantly in the postintervention phase versus the preintervention phase (86.1% vs. 71.7%, p = 0.012). In addition, after the initiative was initiated, mothers were more likely to have 2 postpartum visits (56.6%) relative to mothers who delivered before (39.6%) the intervention was implemented. |

| Weinman and Smith (1994) | Patient level: preterm delivery, previous miscarriage, previous abortion, prenatal care, support system, educational plans, marital status, country of origin, current living arrangements, and age of father. | Postpartum visit attendance | Chi-square tests | Adolescents ranged from 11 to 19 years with mean age of 17.3. Around 56.7% were married and 49.8% lived with their husbands. About 74.7% of the sample reported no support system. Approximately 88.9% delivered at term, 8.3% had a preterm delivery and 2.8% experienced fetal loss. About 85.1% received prenatal care and 34.3% reported no further educational plans. Around 17.3% attended the postpartum visit. | Mothers with a previous preterm birth (100%) or miscarriage (33%) were more likely to return than primiparous mothers (13.3%) or those with a child at home (28.4%; p-value <0.0001). Mothers who did not have prenatal care (34.9%) were more likely to return for a visit than those who had prenatal care (14.2%; p-value <0.0001). |

| Weir et al. (2011) | Patient level: age, race/ethnicity, primary language, county of residence, disability status; children <14 years in household, insurance coverage, prepregnancy health care use, ambulatory office visits, and median household income; overall illness burden, substance use/mental health/IPV diagnoses, or exposure Provider level: provider type |

A postpartum care visit for a pelvic examination or postpartum care on or between 21 and 56 days postdelivery | Multiple logistic regression to analyze associations between the independent variables and HEDIS measures. | Around 81.2% of sample was 20–34 years of age and English was the primary language for 87.4% of the sample. About 44.7% of sample was white, 21.8% were Hispanic, and 10.9% were black. Over 80% of women sampled received timely prenatal care. Approximately 60.1% of the sample attended the postpartum visit. | Mothers with a disability were less likely to attend a postpartum visit (aOR 0.54, 95% CI: 0.32–0.92). Adolescent mothers were less likely to attend (aOR 0.58, 95% CI: 0.40–0.85) than those 20–34 years of age. Mothers with 2–3 children <14 in the household were less likely to attend a visit (aOR 0.71, 95% CI: 0.53–0.95) compared to those with none. Mothers with higher health care use in the year before delivery were more likely to attend (aOR 1.42, 95% CI: 1.10–1.82). Mothers with recorded substance use were less likely to have a visit (aOR 0.40, 95% CI: 0.26–0.62). |

| Wilcox et al. (2016) | Patient level: age, race, ethnicity, attendance of a prenatal visit, type of insurance coverage, socioeconomic status, mode of delivery, and infant birth weight. | A postpartum visit by 12 weeks after birth | Pearson chi-square tests; multivariable logistic regression to identify statistically significant predictors; modified Poisson regression for adjusted risk ratios and 95% confidence intervals. | The majority of the sample were non-white: 40% multiracial, 31% black/African American; almost half Hispanic/Latino. 67% had a vaginal birth; and 9% had low birth weights. Around 67% attended the postpartum visit. | Mothers older than 30 versus those <20 years (p < 0.001), non-Hispanic/Latino versus Hispanic/Latino mothers (p = 0.0003), mothers with private insurance versus Medicaid (p < 0.001), and mothers with a cesarean versus vaginal delivery (p = 0.0003) were more likely to attend a visit. |