Abstract

Introduction

This study retrospectively describes smoking cessation aids, cessation services, and other types of assistance used by current and ex-smokers at their last quit attempt in four high-income countries.

Aims and Methods

Data are from the Wave 3 (2020) International Tobacco Control Four Country Smoking and Vaping Survey in Australia, Canada, England, and the United States (US). Eligible respondents were daily smokers or past-daily recent ex-smokers who made a quit attempt/quit smoking in the last 24-months, resulting in 3614 respondents. Self-reported quit aids/assistance included: nicotine vaping products (NVPs), nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), other pharmacological therapies (OPT: varenicline/bupropion/cytisine), tobacco (noncombustible: heated tobacco product/smokeless tobacco), cessation services (quitline/counseling/doctor), other cessation support (e.g., mobile apps/website/pamphlets, etc.), or no aid.

Results

Among all respondents, at last quit attempt, 28.8% used NRT, 28.0% used an NVP, 12.0% used OPT, 7.8% used a cessation service, 1.7% used a tobacco product, 16.5% other cessation support, and 38.6% used no aid/assistance. Slightly more than half of all smokers and ex-smokers (57.2%) reported using any type of pharmacotherapy (NRT or OPT) and/or an NVP, half-used NRT and/or an NVP (49.9%), and 38.4% used any type of pharmacotherapy (NRT and/or OPT). A quarter of smokers/ex-smokers used a combination of aids. NVPs and NRT were the most prevalent types of cessation aids used in all four countries; however, NRT was more commonly used in Australia relative to NVPs, and in England, NVPs were more commonly used than NRT. The use of NVPs or NRT was more evenly distributed in Canada and the US.

Conclusions

It appears that many smokers are still trying to quit unassisted, rather than utilizing cessation aids or other forms of assistance. Of those who did use assistance, NRT and NVPs were the most common method, which appears to suggest that nicotine substitution is important for smokers when trying to quit smoking.

Implications

Clinical practice guidelines in a number of countries state that the most effective smoking cessation method is a combination of pharmacotherapy and face-to-face behavioral support by a health professional. Most quit attempts however are made unassisted, particularly without the use of government-approved cessation medications. This study found that about two in five daily smokers used approved cessation medications (nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) or other approved pharmacotherapies, such as varenicline). Notably, nicotine substitution in the form of either NRT and nicotine vaping products (NVPs) were the most common method of cessation assistance (used by one in two respondents), but the proportion using NRT and/or NVPs varied by country. Few smokers who attempted to quit utilized cessation services such as stop-smoking programs/counseling or quitlines, despite that these types of support are effective in helping smokers manage withdrawals and cravings. Primary healthcare professionals should ask their patients about smoking and offer them evidence-based treatment, as well as be prepared to provide smokers with a referral to trained cessation counselors, particularly when it comes to tailoring intensive treatment programs for regular daily smokers. Additionally, healthcare providers should be prepared to discuss the use of NVPs, particularly if smokers are seeking advice about NVPs, wanting to try/or already using an NVP to quit smoking, have failed repeatedly to quit with other cessation methods, and/or if they do not want to give up tobacco/nicotine use completely.

Introduction

Tobacco dependence is a chronic and relapsing condition, and smoking cessation is typically preceded by multiple failed quit attempts, particularly among those who have greater nicotine dependence.1,2 Sustained and successful cessation often requires repeated interventions and long-term support, and using an aid can double the chances of staying quit.1,3,4 Clinical practice guidelines in a number of countries state that the most effective smoking cessation method is a combination of pharmacotherapy and face-to-face behavioral support by a health professional.1,5 However, most quit attempts are made without guideline-based treatments, which results in a 90–95% failure rate,1,4 partly owing to smokers depending on their own willpower, and/or because they are unaware of effective treatments to assist with quitting.1,6

Over the last decade, the tobacco and nicotine product landscape has undergone dramatic changes with the emergence of novel and alternative products.1,7 The availability of less toxic forms of nicotine delivery (e.g., heated tobacco products, e-cigarettes, and snus) may represent a new paradigm for smoking cessation by offering smokers an opportunity to obtain nicotine in ways that do not require inhaling tobacco smoke. For example, nicotine vaping products (NVPs, known as e-cigarettes) are potential smoking cessation aids that can replace nicotine and provide a behavioral substitution for cigarette smoking. In recent years, the use of NVPs for smoking cessation has surpassed the use of other government-approved medical therapies in some high-income countries where they are legal and regulated, including in the United States (US), England, Canada, and some European countries.8–11 Moreover, a recent Cochrane review concluded that there is moderate evidence that NVPs with nicotine increase quit rates compared to nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) and nonnicotine-based vaping products.12 However, NVPs are not recommended as a cessation aid in clinical practice guidelines in any country, with the exception of England.13,14 Their inclusion has been opposed by governments, policy-makers, and medical organizations,15 fueled by the uncertainty of long-term safety and effectiveness, the concern that NVPs may weaken tobacco control measures, and that NVPs might serve as a gateway to smoking for nonsmoking youth and young adults.1,7,16,17 In light of these controversies about NVPs, and their absence from clinical practice guidelines, healthcare professionals rarely recommend them to smokers.18

Investigation of how NVPs are used by smokers, and whether they are being used to support a quit attempt should be a research priority. Moreover, exploring other types of cessation assistance is warranted, such as advice from a health professional, behavioral therapy, quitline services, and web and phone-based interventions, which have been found to be useful and effective for assisting smokers during a cessation attempt.1 The current study is a retrospective and descriptive analysis of self-reported quit aids/assistance (pharmacotherapy, NVPs, noncombustible tobacco products, cessation services, and other forms of support) used among a broad sample of adult current daily smokers and recent ex-smokers at their most recent quit attempt in Australia, Canada, England, and the US.

Methods

The International Tobacco Control Project Four Country Smoking and Vaping (ITC 4CV) Survey is a cohort study that consists of parallel online surveys conducted in Canada, US, England, and Australia. Respondents (adults ≥ 18 years) were recruited by commercial panel firms in each country as established cigarette smokers (smoke ≥ monthly, and smoked at least 100 cigarettes in their lifetime), recent ex-smokers (quit ≤ 2 years), or vapers (vape ≥ weekly). Full details of the ITC 4CV Surveys can be found in the Wave 3 (2020) technical report.19

The Wave 3 2020 ITC 4CV Survey was conducted from February to June 2020, and included 11 607 respondents, of whom 7298 were daily smokers and 1010 were recent ex-smokers at the time of the survey. Respondents were eligible for inclusion for the analyses in the current study if they were current daily smokers or past-daily ex-smokers who self-reported that they had made a quit attempt/quit smoking in the last 24 months. This resulted in a sample of 3614 eligible respondents. Respondents’ characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Respondents’ Characteristics, Unweighted %

| Canada | United States | England | Australia | Overall sample | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 1211 | n = 706 | n = 1108 | n = 589 | N = 3614 | ||

| Respondent type | Cohort | 46.7 | 59.6 | 37.4 | 58.2 | 48.2 |

| Replenishment | 53.3 | 40.4 | 62.6 | 41.8 | 51.8 | |

| Sex | Male | 43.7 | 46.2 | 51.8 | 46.5 | 47.1 |

| Female | 56.3 | 53.8 | 48.2 | 53.5 | 52.9 | |

| Age group | 18–39 | 52.4 | 40.7 | 55.4 | 18.3 | 45.5 |

| 40+ | 47.7 | 59.4 | 44.6 | 81.7 | 54.5 | |

| Education level | Low | 28.7 | 32.9 | 11.6 | 30.1 | 24.5 |

| Moderate | 44.2 | 41.9 | 53.2 | 41.1 | 46.0 | |

| High | 26.7 | 25.1 | 33.4 | 28.4 | 28.7 | |

| Not reported | 0.5 | 0.1 | 1.9 | 0.5 | 0.9 | |

| Annual household income | Low | 29.1 | 38.5 | 19.6 | 30.7 | 28.3 |

| Moderate | 26.7 | 26.8 | 33.9 | 22.1 | 28.2 | |

| High | 37.8 | 34.1 | 41.0 | 41.8 | 38.7 | |

| Not reported | 6.4 | 0.6 | 5.5 | 5.4 | 4.8 | |

| Smoking Status | Daily smoker | 76.2 | 69.6 | 79.6 | 80.0 | 76.6 |

| Recent ex-smoker | 23.8 | 30.5 | 20.4 | 20.0 | 23.4 |

Data are unweighted and unadjusted.

Measures

Self-reported Quit Aids/Assistance

Those who answered that they made a quit attempt (current smokers) or quit smoking (ex-smokers) in the last 24 months were subsequently asked: “Did you use a vaping product on your last (smokers)/current (ex-smokers) quit attempt?” Responses were: “yes,” “no,” refused or “don”t know.” Those who had never vaped, or answered “no” or “don’t know,” were included as “no.” Those who did not answer the question were excluded.

For the use of other aids/assistance (referred to hereafter as “quit aids”), respondents were asked: “Which of the following forms of help did you receive or use as part of your last (smokers) / current (ex-smokers) quit attempt?” (referred to hereafter as “last quit attempt” [LQA]). Respondents could select from the following aids (multiple options were allowed to be selected): (1) NRT; (2) varenicline (Chantix™ or Champix); (3) bupropion (Zyban or Wellbutrin); (4) cytisine; (5) quitline service; (6) stop smoking service/behavior counseling; (7) smoking cessation session(s) offered by your doctor; (8) mobile apps; (9) cessation website; (10) pamphlets or brochures; (11) heated tobacco product (e.g., IQOS); (12) smokeless tobacco (snus, chew, or dip); (13) other type of aid not mentioned above (open-ended: books, acupuncture, laser therapy, hypnosis, support groups, social media, cognitive behavioral therapy, meditation/mindfulness, or quit campaign). Mutually exclusive categories were created to distinguish between “exclusive use” or “used in combination” (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Prevalence of Quit Aids Used at Last/Current Quit Smoking Attempt

| n, yes | Weighted % | |

|---|---|---|

| N = 3614 | ||

| Any Use of Quit Aids by Type* | ||

| NVP | 1392 | 28.0 |

| NRT | 1195 | 28.8 |

| Varenicline | 431 | 9.1 |

| Bupropion | 150 | 1.6 |

| Cytisine | 48 | 0.1 |

| Quitline service | 166 | 2.5 |

| Stop smoking service/counseling | 193 | 3.1 |

| Doctor | 169 | 2.8 |

| Mobile apps | 208 | 4.6 |

| Cessation website | 417 | 8.5 |

| Pamphlets/brochures | 235 | 4.0 |

| Heated tobacco product | 101 | 1.2 |

| Smokeless tobacco | 64 | 1.1 |

| Other type of support not listed above | 61 | 1.8 |

| Cessation Aid Categories* | ||

| Any type of OPT (varenicline/ bupropion/cytisine) | 569 | 12.0 |

| Any type of pharmacotherapy (NRT/OPT) | 1593 | 38.4 |

| Any use of NRT and/or or NVP | 2112 | 49.9 |

| Any use of NRT, OPT, and/or NVP | 2364 | 57.2 |

| Any type of (noncombustible) tobacco (HTP/smokeless) | 154 | 1.7 |

| Any type of services | 425 | 7.8 |

| Any type of other support | 723 | 16.5 |

| Exclusive Use of Pharmacotherapy, NVP, or Non-Combustible Tobacco | ||

| Used pharmacotherapy (NRT/OPT) only | 654 | 17.4 |

| Used pharmacotherapy/NVP/tobacco (noncombustible) only | 1198 | 33.0 |

| Any form of Combination of Aids | ||

| Any pharmacotherapy, NVP, tobacco, cessation services, and support combination | 1218 | 25.0 |

| Exclusive Use VS. Combination of Aids | ||

| NVP only | 530 | 13.6 |

| NRT only | 450 | 12.2 |

| OPT only | 204 | 5.5 |

| Cessation services only | 41 | 0.8 |

| Other support only | 149 | 4.6 |

| Tobacco (noncombustible) only | 14 | 0.0 |

| NVP + NRT | 237 | 4.6 |

| NVP + OPT | 77 | 1.3 |

| NRT + OPT | 53 | 0.8 |

| NVP + NRT + OPT | 36 | 0.3 |

| NVP + services or support | 193 | 3.5 |

| NRT + services or support | 164 | 4.7 |

| Other combinations | 458 | 9.3 |

| No Aid at all (no pharmacotherapy /NVP/Tobacco/Cessation Services/Support) | 1008 | 38.6 |

Data are weighted and adjusted for age, sex, country, respondent type, and smoking status.*Quit aids are not mutually exclusive.

NVP: nicotine vaping product; NRT: nicotine replacement therapy; OPT: other pharmacological therapies: varenicline, bupropion, cytisine; Tobacco (noncombustible): HTP or smokeless; Cessation services: quitline, doctor, clinic/counseling; Other support: mobile apps, cessation website, pamphlets/brochures, books, acupuncture, laser therapy, hypnosis, support groups, social media, cognitive behavioral therapy, meditation/mindfulness, quit the campaign.

Statistical Analyses

All estimates are descriptive and were estimated using adjusted regression analyses on weighted data using cross-sectional survey weights. A raking algorithm was used to calibrate the weights on smoking status, geographic region, and demographic measures. Weighting also adjusted for the oversampling of vapers and younger respondents aged 18–24 recruited for the ITC 4CV3 Survey.19

The initial descriptive analyses estimated the prevalence of each cessation aid used (yes vs. no) at LQA (not mutually exclusive) among the entire study sample (n = 3614). Second, we then explored various combined types of aids used among all respondents in the study (yes vs. no): (1) any type of other pharmacological therapies (OPT); (2) any type of pharmacotherapy (NRT/OPT); (3) any use of NRT and/or NVP (nicotine replacement); (4) any use of pharmacotherapy and/or NVPs; (5) any use of a (noncombustible) tobacco product; (6) any use of cessation services (quitline, doctor, clinic/counseling); and (7) any use of other types of support (mobile apps, cessation website, pamphlets/brochures, books, acupuncture, laser therapy, hypnosis, support groups, social media, cognitive behavioral therapy, meditation/mindfulness, quit campaign). Third, we then examined the prevalence of exclusive use of exclusive use of nicotine and/or an OPT among all respondents (n = 3614, yes vs. no) for: (1) pharmacotherapy (NRT/OPT only); and any type of pharmacotherapy, and/or alternative tobacco/nicotine products (NRT/OPT/NVP/tobacco) to see if respondents were substituting their nicotine only (e.g., without the use of other forms of support or cessation services). Fourth, we investigated the use of cessation aid categories (yes vs. no) by (1) country (n = 3614), and then (2) conditionally among only those who used an aid at LQA (n = 2606) for NVP; NRT; OPT, tobacco, cessation services; and other support (not mutually exclusive). The between-country analysis also included “no aid,” but did not include heated tobacco products (HTPs)/smokeless tobacco due to the small number of smokers who used them in some countries. Finally, we examined aids used alone or in combination (mutually exclusive) or no aid (n = 3614).

All analyses controlled for age, sex, country, respondent type (cohort vs. replenishment), and smoking status (current daily smoker vs. recent ex-smoker). All confidence intervals were computed at the 95% confidence level. Analyses were conducted using SAS Version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc. 2013, Cary, North Carolina, USA).

Results

Quit Aids Used at LQA

Table 2 shows the quit aids used at LQA. Among all smokers/ex-smokers (N = 3614), 38.6% used no type of aid at all, 28.8% used NRT, 28.0% used an NVP, 12.0% used OPT, 7.8% used a cessation service, 1.7% used a noncombustible tobacco product, and 16.5% used other types of cessation support. Slightly more than half of the respondents (57.2%) used pharmacotherapy (NRT/OPT) and/or an NVP, half used NRT and/or an NVP (49.9%), and 38.4% used a form of pharmacotherapy.

When quit aids at LQA were examined to describe use either exclusively or in combination, 13.6%, 12.2%, 5.5%, 4.6%, and 0.8% exclusively used an NVP, NRT, OPT, other types of support, or cessation services respectively. Among respondents who did not use any type of services or other support, 17.4% used pharmacotherapy only and 33.0% used pharmacotherapy, NVP, and/or tobacco only. A quarter of respondents used a combination of various forms of assistance (Table 2).

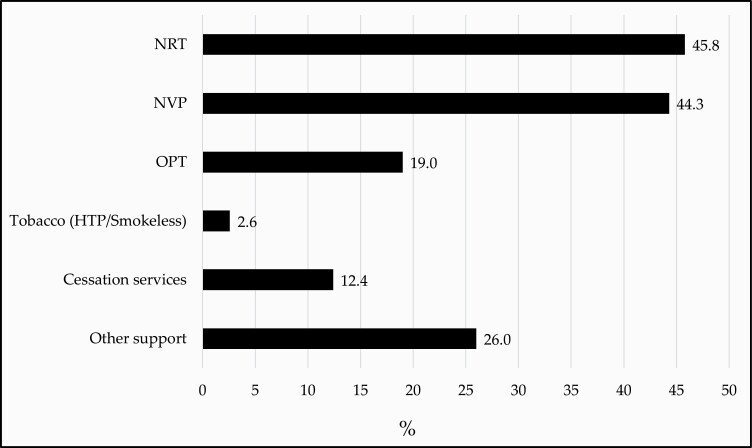

Among those who did use an aid at LQA (n = 2606), 45.8% used NRT, 44.3% used an NVP, 19.0% used OPT, 12.4% used cessation services, and 26.0% used other types of support (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Any use of quit aids/assistance among respondents who self-reported using an aid at LQA, n = 2606. Data are weighted and adjusted for age, sex, country, respondent type, and smoking status. Quit aids are not mutually exclusive. NVP: Nicotine vaping product; NRT: Nicotine replacement therapy; OPT: Other pharmacological therapies: varenicline, bupropion, cytisine; Tobacco: heated tobacco product (HTP), smokeless (snus, chew dip); Cessation services: quitline, doctor, clinic/counseling; Other support: mobile apps, cessation website, pamphlets/brochures, books, acupuncture, laser therapy, hypnosis, support groups, social media, cognitive behavioral therapy, meditation/mindfulness, quit the campaign.

Country Differences in Aids Used at LQA

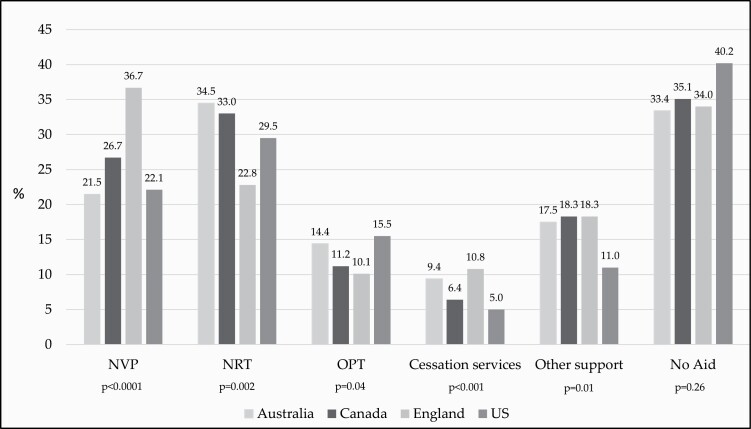

Figure 2 shows the aids used by country and Table 3 shows the country post hoc analyses. Using no aid was highest in the US (40.2%), followed by Canada (35.1%), England (34.0%), and Australia (33.4%), although there was little evidence for statistical differences between countries (p = .26).

Figure 2.

Prevalence of quit aids used at last quit attempt by country, N = 3614. Data are weighted and adjusted for age, sex, country, respondent type, and smoking status. Quit aids are not mutually exclusive. NVP: Nicotine vaping product; NRT: Nicotine replacement therapy; OPT: Other pharmacological therapies (varenicline, bupropion, cytisine); Cessation services: quitline, doctor, clinic/counseling; Other support: mobile apps, cessation website, pamphlets/brochures, books, acupuncture, laser therapy, hypnosis, support groups, social media, cognitive behavioral therapy, meditation/mindfulness, quit the campaign.

Table 3.

Country Differences of Quit Aids Used At LQA

| Country comparison | OR | LCI | UCI |

|---|---|---|---|

| NVP (n = 1392) | |||

| Australia vs. Canada | 0.75 | 0.54 | 1.05 |

| Australia vs. England | 0.47 | 0.33 | 0.68 |

| Australia vs. United States | 0.97 | 0.67 | 1.40 |

| Canada vs. England | 0.63 | 0.48 | 0.82 |

| Canada vs. United States | 1.29 | 0.96 | 1.71 |

| England vs. United States | 2.05 | 1.48 | 2.84 |

| NRT (n = 1195) | |||

| Australia vs. Canada | 1.07 | 0.80 | 1.44 |

| Australia vs. England | 1.79 | 1.26 | 2.54 |

| Australia vs. United States | 1.26 | 0.90 | 1.75 |

| Canada vs. England | 1.67 | 1.27 | 2.20 |

| Canada vs. United States | 1.18 | 0.90 | 1.53 |

| England vs. United States | 0.70 | 0.51 | 0.97 |

| OPT (n = 569) | |||

| Australia vs. Canada | 1.33 | 0.91 | 1.94 |

| Australia vs. England | 1.49 | 0.94 | 2.38 |

| Australia vs. United States | 0.91 | 0.61 | 1.37 |

| Canada vs. England | 1.12 | 0.77 | 1.63 |

| Canada vs. United States | 0.69 | 0.50 | 0.94 |

| England vs. United States | 0.61 | 0.41 | 0.92 |

| Cessation services (n = 425) | |||

| Australia vs. Canada | 1.50 | 0.94 | 2.40 |

| Australia vs. England | 0.85 | 0.52 | 1.39 |

| Australia vs. United States | 1.94 | 1.16 | 3.27 |

| Canada vs. England | 0.57 | 0.39 | 0.82 |

| Canada vs. United States | 1.30 | 0.85 | 1.98 |

| England vs. United States | 2.29 | 1.49 | 3.53 |

| Other support (n = 723) | |||

| Australia vs. Canada | 0.95 | 0.65 | 1.38 |

| Australia vs. England | 0.95 | 0.62 | 1.44 |

| Australia vs. United States | 1.72 | 1.08 | 2.73 |

| Canada vs. England | 1.00 | 0.74 | 1.36 |

| Canada vs. United States | 1.81 | 1.25 | 2.63 |

| England vs. United States | 1.81 | 1.20 | 2.74 |

| No aid (n = 1008) | |||

| Australia vs. Canada | 0.93 | 0.69 | 1.25 |

| Australia vs. England | 0.98 | 0.69 | 1.38 |

| Australia vs. United States | 0.75 | 0.53 | 1.05 |

| Canada vs. England | 1.05 | 0.81 | 1.38 |

| Canada vs. United States | 0.81 | 0.62 | 1.06 |

| England vs. United States | 0.76 | 0.56 | 1.05 |

Data are weighted and adjusted for age, sex, country, respondent type, and smoking status.

LQA, last quit attempt; NVP, nicotine vaping product; NRT, nicotine replacement therapy; OPT, other pharmacological therapies.

NVP use differed between countries (p < .0001), with a significantly higher percentage of respondents using NVP for quit attempts in England (36.7%) relative to the other three countries [Canada (26.7%), the US (22.1%), and Australia (21.5%)].

NRT use also differed between countries (p = .002), with Australian respondents reporting the highest rate of NRT use (34.5%), followed by Canada (33.0%), the US (29.5%), and England (22.8%). Canada and Australia had a significantly higher proportion of NRT use compared to England, and England a higher proportion than the US (Figure 2).

The use of OPT differed by country (p = .04), with the US having the highest proportion of OPT use (15.5%), followed by Australia (14.4%), Canada (11.2%), and England (10.1%). The US had a significantly higher proportion of OPT use than both England and Canada.

The use of cessation services differed by countries (p < .001). England (10.8%) had a significantly higher proportion of respondents who used cessation services compared to Canada (6.4%) and the US (5.0%). Australia and England had a significantly higher proportion of the use of cessation services compared to the US, and England also had a significantly higher rate than Canada.

Finally, the use of other types of support also differed by country (p = .01), where Canada (18.3%), England (18.3%), and Australia (17.5%) were all more likely to utilize other types of support than the US (11.0%).

Discussion

This study retrospectively describes smoking cessation aids, cessation services, and other types of assistance used by current and ex-smokers at their LQA in Australia, Canada, England, and the US. Overall, we found that slightly more than one-third of respondents did not use any type of aid at LQA, and about two in five respondents used approved cessation medications (NRT and/or OPT). Notably, nicotine substitution in the form of either NRT and/or NVPs was the most common method of cessation assistance (used by one in two respondents), but the proportion using NRT or NVPs varied by country. Interestingly, it appears that the prevalence of pharmacotherapy use (NRT and OPT) for a quit attempt has remained stable (about 40%) across the four countries since 2008.20

Few respondents used other forms of services and support. For example, about 8% of respondents reported using any type of services from their doctor, a cessation clinic/service, and/or a quitline, which is disconcerting, considering that counseling from healthcare providers and cessation counselors are effective in helping smokers learn how to manage withdrawals and cravings.1,21,22 These service providers can also suggest the use of medical therapies that can further increase a smokers’ chance of quitting.1,4,5 Unfortunately, studies have shown that a large proportion of smokers who have had a recent physician visit do not receive advice to quit smoking,1,11,18 and receive a much lower level of systematic identification and support compared to other chronic conditions.23,24 This lack of guidance constitutes a lost opportunity to help smokers, especially since some smokers are unaware of the forms of cessation assistance that are available, or they do not believe that cessation aids improve the likelihood of quitting.1,6 Perhaps most importantly, primary healthcare professionals and other specialists should ask their patients about smoking and offer them treatment, as well as be prepared to provide smokers with a referral to trained cessation counselors, particularly when it comes to tailoring intensive treatment programs for regular daily smokers who may be highly addicted.1,4,5

While this study did not examine the efficacy of any type of cessation aid or other assistance, we found that among those who did use an aid at LQA, nearly half used an NVP despite the controversy in many countries in supporting their use. Population evidence regarding the effectiveness of using NVPs to quit smoking is mixed; however, there is growing evidence from randomized trials and observational studies that NVPs can be helpful in facilitating quit smoking attempts, reductions in cigarette consumption, and smoking cessation.8,12,25–31 While the evidence of effectiveness for cessation has not been found in other studies,25,32,33 it does indicate stronger effects when NVPs are used to quit smoking (vs. use for other reasons) when a certain type of device used (e.g., tank-based system, salt-based e-liquid), and when used more frequently (e.g., daily).27,33–37

There were some cross-country differences found in this study. For example, England had the highest proportion of respondents who used an NVP for cessation compared to the other three countries. This is not surprising, given that England has the most supportive smoking harm-reduction policies, with several public health organizations supporting the use of NVPs for cessation.13,14 Using NVPs as cessation support is included in the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines, providing guidance for health professionals to give informed advice about the use of NVPs for smoking cessation.14 National tracking data in England have shown that the increased use of NVPs was positively associated with a reduction in smoking.38,39 In contrast, Australian smokers were less likely to use NVPs for their LQA relative to the other countries. This could be because NVPs are effectively prohibited as they are classified as poison under Australian law; 40 thus, it is illegal to possess nicotine without a valid prescription. In general, Australian public health authorities have taken a “precautionary approach” and have mostly advised against their use, even for smoking cessation,17,40 albeit with some recent exceptions, where some Australian medical organizations have recognized they may have the potential to help some smokers quit.40 In the US, since 2016, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has regulated NVPs as tobacco products.41 Many US-based public health organizations have not supported the use of NVPs for smoking cessation, often citing insufficient evidence that e-cigarettes can help smokers quit, the unknown health harms of long-term/regular use, and use by nonsmokers (particularly by youth).42,43 Additionally, the 2019 outbreak of severe pulmonary disease (EVALI) in the US was initially attributed to NVPs, which greatly elevated concerns about the safety of vaping products, leading to a flurry of regulations to restrict consumer access to NVPs. The EVALI outbreak was later discovered to be caused by vaping vitamin E acetate added to cannabis vaping liquids.42,44,45 Thus, as a result of the negative publicity, smokers may have been discouraged from using NVPs when they attempted to quit smoking. The Canadian government’s 2018 Tobacco and Vaping Products Act,46 allowed NVPs to be regulated and sold. While the Canadian government has not approved e-cigarettes to be used as a method of cessation, they have suggested that NVPs may help smokers quit,47 but the Canadian Medical Association has called for more research into the possible health benefits and consequences of NVPs and evidence for their effectiveness as a smoking cessation aid.48 However, the wide range of availability in Canada and more liberal regulations since 2018 may account for the higher rates of NVP use for cessation in Canada compared to Australia and the US.

Interestingly, while there were country differences in the use of NVPs and NRT, the proportion using nicotine products in either of these forms was strikingly similar across the four countries. This may suggest that nicotine substitution is important for smokers when trying to quit, but that the proportion of smokers using NVPs versus NRT may vary depending on the country’s regulatory stance on NVPs. This seems to be most evident for Australia and England, where NRT was more commonly used in Australia relative to NVPs, and in England, NVPs were more commonly used than NRT. The use of NVPs and NRT was more evenly distributed in Canada and the US, where NVPs are legal and regulated, but not encouraged as a primary aid for cessation. However, while we have presented a snapshot of what smokers are using for their most recent quit attempt, we cannot attribute this to country policies in the present study due to the cross-sectional design. It would be valuable for future research to investigate how changing policies, either by increasing or reducing access to alternative noncombustible tobacco and nicotine products, may affect smoking cessation practices and smoking behaviors.

This study has important strengths, in that we had a large sample of current daily smokers and recent ex-smokers from four high-income countries. However, there are some important limitations to also consider. First, this study was cross-sectional, and therefore it cannot be used to demonstrate temporality or infer causality. Second, due to the sampling methods of ITC 4CV, the estimates reported in this study may not be representative of each country’s population. In particular, vapers were purposefully recruited for this survey, so our results may over-represent the use of NVPs for cessation, even though weighting was applied to correct for over-sampling. However, our estimates do not appear to be much different from national data. For example, the national Toolkit Study in England found that at the latest period (2020), 30% of those who made a quit attempt in England used an NVP,9 and our study found that 37% reported doing so. Canadian national data showed that 23.6% used an NVP to help them quit smoking in 2019,10 and our study found that 26.7% used an NVP at LQA. Third, we did not ask respondents if their NVP contained nicotine at their LQA; however, only 38 respondents reported that at the time of the survey, they did not vape with nicotine. Therefore, it is unknown whether these respondents used a non-nicotine vaping product for quitting, or instead used a nicotine-based e-liquid at the time of their LQA, and then down-titrated to no nicotine use over time. An alternative explanation for those using NVP with NRT and/or OPT is that some used a non-nicotine e-cigarette to help with the behavioral substitution of smoking only. Finally, the retrospective measurements in this study relied on respondent recall, which may impact reports of assistance used during a quit attempt. It has been previously shown that some smokers have poor recall of cessation methods,6,49 and that recall of quit attempts decreases with increasing time since the quit attempt,49,50 and this differs between those who used medication compared to those who did not.49

Conclusion

Although we know from two decades of research that smoking cessation aids increase the likelihood of successful quitting, particularly pharmacotherapy, we found that over one-third of respondents did not use any type of aid during their most recent (last) quit attempt. And while this proportion is lower than previous reports,1 it appears that many smokers are still trying to quit unassisted rather than utilizing proven cessation medications and services. Among respondents who did use an aid, nicotine substitution in the form of NRT and/or NVPs was the most commonly reported form of assistance. In light of these findings, it remains imperative that healthcare providers proactively screen for smoking, as well as communicate to smokers that their chances of successful smoking cessation will be greatly increased if they use an effective aid, particularly government-approved stop-smoking medications combined with behavioral support. Additionally, healthcare providers should be prepared to discuss the use of vaping products since many smokers have heard of them, and some may already be using NVPs to transition off cigarettes. Regardless of whatever quit methods patients may be using, or consider using, health professionals need to support their patients’ efforts to quit cigarette use as soon as possible. Providing the most recent and accurate information to smokers about the risks and benefits of different smoking cessation aids is important, and where evidence is lacking, that should be acknowledged so that they can make informed choices. Future research should examine the extent to which NVPs may be displacing pharmacotherapies (particularly NRT) as a cessation method, as well as to how NVPs are contributing to the expansion of quitting smoking, both of which may have important implications for guiding policies and estimating the impact of NVPs on population-level cessation rates.

Supplementary Material

A Contributorship Form detailing each author’s specific involvement with this content, as well as any supplementary data, are available online at https://academic.oup.com/ntr.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from the US National Cancer Institute (P01 CA200512), the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (FDN-148477), and the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (APP 1106451). GTF was supported in part by a Senior Investigator Award from the Ontario Institute for Cancer Research. Additional support to DTL is provided by the Center for the Assessment of Tobacco Regulations (U54CA229974). AL is supported by the Center for the Assessment of Tobacco Regulations (U54CA229974).

Declaration of Interest

KMC has served as a paid expert witness in litigation filed against cigarette manufacturers. GTF and DH have served as expert witnesses on behalf of governments in litigation involving the tobacco industry. AM is a UK National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Senior Investigator. The views expressed in this article are of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR, or the UK Department of Health and Social Care. All other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethics Approval

Study questionnaires and materials were reviewed and provided clearance by Research Ethics Committees at the following institutions: University of Waterloo (Canada, ORE#20803/30570, ORE#21609/30878), King’s College London, UK (RESCM-17/18–2240), Cancer Council Victoria, Australia (HREC1603), Deakin University, Australia (HREC2018-346), University of Queensland, Australia (2016000330/HREC1603); and Medical University of South Carolina (waived due to minimal risk). All participants provided consent to participate.

References

- 1.US Department of Health and Human Services. Smoking Cessation: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chaiton M, Diemert L, Cohen JE, et al. Estimating the number of quit attempts it takes to quit smoking successfully in a longitudinal cohort of smokers. BMJ Open. 2016;6(6):e011045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eisenberg MJ, Filion KB, Yavin D, et al. Pharmacotherapies for smoking cessation: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. CMAJ. 2008;179(2):135–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rigotti NA. Strategies to help a smoker who is struggling to quit. JAMA. 2012;308(15):1573–1580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reid RD, Pritchard G, Walker K, Aitken D, Mullen KA, Pipe AL. Managing smoking cessation. CMAJ. 2016;188(17-18):E484–E492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hammond D, McDonald PW, Fong GT, Borland R. Do smokers know how to quit? Knowledge and perceived effectiveness of cessation assistance as predictors of cessation behaviour. Addiction. 2004;99(8):1042–1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine (NASEM). Public Health Consequences of E-Cigarettes. 2018. https://www.nap.edu/catalog/24952/public-health-consequences-of-e-cigarettes. Accessed December 15, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Benmarhnia T, Pierce JP, Leas E, et al. Can E-Cigarettes and pharmaceutical aids increase smoking cessation and reduce cigarette consumption? Findings from a nationally representative cohort of American Smokers. Am J Epidemiol. 2018;187(11):2397–2404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.West R, Beard E, Brown J. Trends in Electronic cigarettes in England-Latest Trends. 2020. http://www.smokinginengland.info/latest-statistics/. Accessed December 15, 2020.

- 10.Reid JL, Hammond D, Rynard VL, Madfhill CL, Burkhalter R.. Tobacco Use in Canada: Patterns and Trends, 2019 Edition. Waterloo, ON: Propel Centre for Population Health Impact, University of Waterloo; 2017. https://uwaterloo.ca/tobacco-use-canada/tobacco-use-canada-patterns-and-trends. Accessed on December 15, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hummel K, Nagelhout GE, Fong GT, et al. Quitting activity and use of cessation assistance reported by smokers in eight European countries: Findings from the EUREST-PLUS ITC Europe Surveys. Tob Induc Dis. 2018;16(Suppl 2):A6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hartmann-Boyce J, McRobbie H, Lindson N, et al. Electronic cigarettes for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;10(10):CD010216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Public Health England. E-Cigarettes: A Developing Public Health Consensus. Joint Statement on e-Cigarettes by Public Health England and other UK public health organisations; July 2016. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/534708/E-cigarettes_joint_consensus_statement;_2016.pdf. Accessed December 15, 2020.

- 14.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Stop Smoking Interventions and Services. NICE Guideline [NG92]. Advice on e-Cigarettes. 2018. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng92/chapter/Recommendations#advice-on-ecigarettes. Accessed December 15, 2020.

- 15.Hatsukami DK, Carroll DM. Tobacco harm reduction: Past history, current controversies and a proposed approach for the future. Prev Med. 2020;140:106099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.World Health Organization. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. Countries Vindicate Cautious Stance on e-cigarettes. 2014. https://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/92/12/14-031214/en/. Accessed December 15, 2020.

- 17.Greenhalgh EM, Jenkins S, Scollo MM. InDepth 18B: Electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes). In: Greenhalgh EM, Scollo MM, Winstanley MH, ed. Tobacco in Australia: Facts and Issues. Melbourne: Cancer Council Victoria; 2020. https://www.tobaccoinaustralia.org.au/chapter-18-harm-reduction/indepth-18b-e-cigarettes/18b-10-position-statements. Accessed February 10, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gravely S, Thrasher JF, Cummings KM, et al. Discussions between health professionals and smokers about nicotine vaping products: Results from the 2016 ITC Four Country Smoking and Vaping Survey. Addiction. 2019;114(Suppl 1):71–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.ITC Project. ITC Four Country Smoking and Vaping Survey, Wave 3 (4CV3, 2020) Preliminary Technical Report. University of Waterloo, Waterloo, Ontario, Canada; Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, South Carolina, United States; Cancer Council Victoria, Melbourne, Australia; the University of Queensland, Australia; King’s College London, London, United Kingdom; 2020, October. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fix BV, Hyland A, Rivard C, et al. Usage patterns of stop smoking medications in Australia, Canada, the United Kingdom, and the United States: Findings from the 2006-2008 International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2011;8(1):222–233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hersi M, Traversy G, Thombs BD, et al. Effectiveness of stop smoking interventions among adults: Protocol for an overview of systematic reviews and an updated systematic review. Syst Rev. 2019;8(1):28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.West R, Raw M, McNeill A, et al. Health-care interventions to promote and assist tobacco cessation: A review of efficacy, effectiveness and affordability for use in national guideline development. Addiction. 2015;110(9):1388–1403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bernstein SL, Yu S, Post LA, Dziura J, Rigotti NA. Undertreatment of tobacco use relative to other chronic conditions. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(8):e59–e65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gravely-Witte S, Stewart DE, Suskin N, Higginson L, Alter DA, Grace SL. Cardiologists’ charting varied by risk factor, and was often discordant with patient report. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61(10):1073–1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brose LS, Hitchman SC, Brown J, West R, McNeill A. Is the use of electronic cigarettes while smoking associated with smoking cessation attempts, cessation and reduced cigarette consumption? A survey with a 1-year follow-up. Addiction. 2015;110(7):1160–1168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hajek P, Phillips-Waller A, Przulj D, et al. A randomized trial of e-cigarettes versus nicotine-replacement therapy. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(7):629–637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Berry KM, Reynolds LM, Collins JM, et al. E-cigarette initiation and associated changes in smoking cessation and reduction: The Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health Study, 2013-2015. Tob Control. 2019;28(1):42–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rahman MA, Hann N, Wilson A, Mnatzaganian G, Worrall-Carter L. E-cigarettes and smoking cessation: Evidence from a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10(3):e0122544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jackson SE, Farrow E, Brown J, Shahab L. Is dual use of nicotine products and cigarettes associated with smoking reduction and cessation behaviours? A prospective study in England. BMJ Open. 2020;10(3):e036055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johnson L, Ma Y, Fisher SL, et al. E-cigarette usage is associated with increased past-12-month quit attempts and successful smoking cessation in two US population-based surveys. Nicotine Tob Res. 2019;21(10):1331–1338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pasquereau A, Guignard R, Andler R, Nguyen-Thanh V. Electronic cigarettes, quit attempts and smoking cessation: A 6-month follow-up. Addiction. 2017;112(9):1620–1628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pierce JP, Benmarhnia T, Chen R, et al. Role of e-cigarettes and pharmacotherapy during attempts to quit cigarette smoking: The PATH Study 2013-16. PLoS One. 2020;15(9):e0237938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang RJ, Bhadriraju S, Glantz SA. E-cigarette use and adult cigarette smoking cessation: A meta-analysis. Am J Public Health. 2021;111(2):230–246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Glasser A, Vojjala M, Cantrell J, et al. Patterns of e-cigarette use and subsequent cigarette smoking cessation over two years (2013/2014 to 2015/2016) in the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) Study. Nicotine Tob Res. 2021;23(4):669–677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Farsalinos KE NR. E-cigarettes and smoking cessation in the United States according to frequency of e-cigarette use and quitting duration: Analysis of the 2016 and 2017 National Health Interview Surveys. Nicotine Tob Res. 2020;22(5):655–662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hitchman SC, Brose LS, Brown J, Robson D, McNeill A. Associations between E-cigarette type, frequency of use, and quitting smoking: Findings from a longitudinal online panel survey in Great Britain. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015;17(10):1187–1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Levy DT, Yuan Z, Luo Y, Abrams DB. The Relationship of E-cigarette use to cigarette quit attempts and cessation: Insights from a large, nationally representative U.S. survey. Nicotine Tob Res. 2018;20(8):931–939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McNeill A, Brose LS, Calder R, Bauld L, Robson D.. Evidence review of e-cigarettes and heated tobacco products 2018. A report commissioned by Public Health England. London: Public Health England; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Beard E, West R, Michie S, Brown J. Association of prevalence of electronic cigarette use with smoking cessation and cigarette consumption in England: A time-series analysis between 2006 and 2017. Addiction. 2020;115(5):961–974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. Tobacco Harm Reduction (Chapter 5) in: Supporting Smoking Cessation: A Guide for Health Professionals. 2nd ed. Melbourne, Vic: RACGP; 2019. https://www.racgp.org.au/clinical-resources/clinical-guidelines/key-racgp-guidelines/view-all-racgp-guidelines/supporting-smoking-cessation/tobacco-harm-reduction. Accessed February 12, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Food and Drug Administration, HHS. Deeming Tobacco Products To Be Subject to the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, as Amended by the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act; Restrictions on the Sale and Distribution of Tobacco Products and Required Warning Statements for Tobacco Products. Final rule. Fed Regist. 2016;81(90):28973–9106. [PubMed]

- 42.Competitive Enterprise Institute. Media News Story. Federal Health Agencies’ Misleading Messaging on E-Cigarettes Threatens Public Health. January 2020. https://cei.org/onpoint/federal-health-agencies-misleading-messaging-on-e-cigarettes-threatens-public-health/#_edn5. Accessed December 15, 2020.

- 43.American Cancer Society. American Cancer Society Position Statement on Electronic Cigarettes. https://www.cancer.org/healthy/stay-away-from-tobacco/e-cigarettes-vaping/e-cigarette-position-statement.html. Accessed December 15, 2020.

- 44.Hammond D. Outbreak of pulmonary diseases linked to vaping. BMJ. 2019;366:l5445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Most EVALI Patients Used THC-Containing Products as New Cases Continue To Decline. January 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2020/p0117-evali-cases-decline.html. Accessed December 15, 2020.

- 46.Government of Canada. Tobacco and Vaping Products Act (TVPA). December 2018. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/health-concerns/tobacco/legislation/federal-laws/tobacco-act.html. Accessed December 15, 2020.

- 47.Health Canada. Vaping and Quitting Smoking. June 2020. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/smoking-tobacco/vaping/smokers.html. Accessed December 15, 2020.

- 48.Canadian Medical Association. Smoking and e-cigarettes. January 2020. https://www.cma.ca/smoking-and-e-cigarettes. Accessed December 15, 2020.

- 49.Borland R, Partos TR, Cummings KM. Systematic biases in cross-sectional community studies may underestimate the effectiveness of stop-smoking medications. Nicotine Tob Res. 2012;14(12):1483–1487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kasza KA, Hyland AJ, Borland R, et al. Effectiveness of stop-smoking medications: Findings from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey. Addiction. 2013;108(1):193–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.