Abstract

Introduction

Variation in CYP2A6, the primary enzyme responsible for nicotine metabolism, is associated with nicotine dependence, cigarette consumption, and abstinence outcomes in smokers. The impact of CYP2A6 activity on nicotine reinforcement and tobacco cue-reactivity, mechanisms that may contribute to these previous associations, has not been fully evaluated.

Aims and Methods

CYP2A6 activity was indexed using 3 genetic approaches in 104 daily smokers completing forced-choice and cue-induced craving tasks assessing nicotine reinforcement and tobacco cue-reactivity, respectively. First, smokers were stratified by the presence or absence of reduced/loss-of-function CYP2A6 gene variants (normal vs. reduced metabolizers). As nicotine metabolite ratio (NMR) is a reliable biomarker of CYP2A6 activity, our second and third approaches used additional genetic variants identified in genome-wide association studies of NMR to create a weighted genetic risk score (wGRS) to stratify smokers (fast vs. slow metabolizers) and calculate a wGRS-derived NMR.

Results

Controlling for race and sex, normal metabolizers (vs. reduced) selected a greater proportion of puffs from nicotine-containing cigarettes (vs. denicotinized) on the forced-choice task (p = .031). In confirmatory analyses, wGRS-based stratification (fast vs. slow metabolizers) produced similar findings. Additionally, wGRS-derived NMR, which correlated with actual NMR assessed in a subset of participants (n = 55), was positively associated with the proportion of puffs from nicotine-containing cigarettes controlling for race and sex (p = .015). None of the CYP2A6 indices were associated with tobacco cue-reactivity in minimally deprived smokers.

Conclusions

Findings suggest increased nicotine reinforcement is exhibited by smokers with high CYP2A6 activity, which may contribute to heavier smoking and poorer cessation outcomes previously reported in faster metabolizers.

Implications

CYP2A6 activity is a key determinant of smoking behavior and outcomes. Therefore, these findings support the targeting of CYP2A6 activity, either therapeutically or as a clinically relevant biomarker in a precision medicine approach, for tobacco use disorder treatment.

Introduction

Tobacco use disorder, a problematic pattern of tobacco use, is responsible for significant health and financial burden. Worldwide, there are estimated to be more than one billion tobacco smokers.1 Across the globe annually, deaths are estimated to be over eight million1 and health care costs and other financial losses attributable to smoking are estimated to be thousands of billions of dollars.2 Tobacco use disorder is a chronic relapsing condition. Although pharmacotherapy for smoking cessation can be beneficial in assisting smokers to achieve initial abstinence, relatively recent data modeling suggests 12-month abstinence rates may be less than 23% when using available cessation pharmacotherapy.3 Increasing our understanding of the biology underlying tobacco addiction may lead to improved cessation outcomes via identification of cessation targets or personalized treatment strategies.

CYP2A6 is the primary enzyme responsible for the majority of nicotine inactivation to cotinine. In turn, cotinine is exclusively metabolized by CYP2A6 to trans-3′-hydroxycotinine (3HC), and the ratio of 3HC to cotinine, referred to as the nicotine metabolite ratio (NMR), is a reliable and validated biomarker of CYP2A6 activity.4 The NMR is highly heritable, and genome-wide association studies (GWASs) of the NMR have identified many variants mapping to CYP2A6.5–7 CYP2A6 activity can therefore be operationalized phenotypically by assessment of NMR (lower NMR indicates slower nicotine clearance4), or genetically by identification of change-of-function CYP2A6 gene variants. Individuals with reduced or loss-of-function variants, such as CYP2A6*2, *9, and *17 (for full list see methods and https://www.pharmvar.org/gene/CYP2A6), are typically described as reduced metabolizers, while those without reduced or loss-of-function variant alleles are typically defined as normal metabolizers.8 Individual with reduced or loss-of-function CYP2A6 variants (“reduced metabolizers”) have lower CYP2A6 activity, and therefore lower NMR (ie, lower 3HC/cotinine), compared with individuals without these variants (“normal metabolizers”).

Variation in CYP2A6 activity, measured by the NMR or by CYP2A6 genotype, is associated with numerous smoking behaviors including cigarette consumption, nicotine dependence, and smoking cessation outcomes. A positive correlation has been reported between NMR and cigarettes per day,9 indicating that consumption is greater in smokers with faster CYP2A6 activity. Consistent with this, a meta-analysis examining the association of CYP2A6 genetic polymorphisms with consumption found that reduced metabolizers smoked fewer cigarettes per day,10 and a large GWAS, in 337 334 individuals, replicated the association between multiple variants in CYP2A6 and cigarettes per day.11 In terms of nicotine dependence, an early study showed that individuals lacking functional CYP2A6 were protected against dependence,12 and more recent studies support the idea that dependence may be lowest in reduced metabolizers.12–14 However, some studies have failed to find an association between dependence and CYP2A6 genotype,10 and others find the opposite association.15,16 With respect to smoking cessation, reduced metabolism was associated with an increased likelihood of abstinence in adolescent smokers.17 In adult smokers receiving transdermal nicotine patches, higher quit rates have been found for reduced metabolizers relative to faster metabolizers.18,19 Further, in a NMR-randomized trial, faster metabolizers had higher quit rates on varenicline compared with nicotine patch, while quit rates were similar for each treatment in slower metabolizers.20

Despite evidence that CYP2A6 activity may alter the risk for nicotine dependence and smoking behaviors, including relapse and consumption levels, causative mechanisms for these associations are not fully elucidated. Nicotine reinforcement and cue-reactivity may represent two such mechanisms. The reinforcing properties of nicotine underlie addiction to tobacco smoking,21,22 and variation in CYP2A6 activity may impact nicotine reinforcement. For instance, Sofuoglu et al. found higher levels of nicotine-induced liking and drug wanting among overnight abstinent smokers administered IV nicotine who were in the highest quartile of the NMR (ie, fastest metabolizers).23 Further, normal (vs. reduced) metabolizers had a shorter time to first cigarette during free smoking which may indicate increased nicotine reinforcement in smokers with higher CYP2A6 activity.24 However, a separate study found no NMR-based differences in reward/satisfaction scores following smoking.25 There is additional evidence of an effect of CYP2A6 activity on nicotine reinforcement from self-administration studies. In mice, administration of a novel CYP2A6 inhibitor reduced nicotine self-administration.26 Similarly, in human smokers, administration of methoxsalen, a CYP2A6 inhibitor, reduced smoking during a period of free smoking.27

Tobacco-associated cues play an important role in smoking and relapse. Cues increase craving for cigarettes and promote relapse and existing smoking cessation medication does not offer protection from cue-induced increases in craving.28 The neural response to smoking cues in many brain regions including the amygdala, hippocampus, striatum, insula, and cingulate cortex is greater in smokers with higher CYP2A6 activity.29,30 The larger response among faster CYP2A6 metabolizers may be due to greater coupling between exposure to cigarettes and surges in blood nicotine concentration, in turn increasing conditioned responses to smoking cues.29

The current study is the first to investigate the association of CYP2A6 genotype-predicted activity with objectively assessed nicotine reinforcement and tobacco cue-induced craving within the same group of daily smokers. Participants completed forced-choice and cue-reactivity tasks assessing nicotine reinforcement and tobacco cue-induced craving, respectively, and were divided into reduced or normal metabolism groups8 based on the presence or absence of reduced/loss-of-function CYP2A6 variants. In supplementary confirmatory analyses, smokers were grouped, as slow or fast metabolizers, based on CYP2A6 weighted genetic risk scores (wGRSs) that were described previously31,32 and shown to capture 30%–35% of the variation in the NMR. We also investigated associations for predicted NMR (based on the wGRSs) with nicotine reinforcement and cue-reactivity. We hypothesized that smokers with higher CYP2A6 activity (ie, faster nicotine metabolism), measured using the genetic groupings or predicted NMR phenotype, would exhibit greater nicotine reinforcement and cue-induced craving compared with smokers with lower CYP2A6 activity. Greater nicotine reinforcement and tobacco cue-reactivity in those with high CYP2A6 activity might contribute to the higher cigarette consumption and poorer abstinence outcomes observed in these individuals.

Materials and Methods

Participants

Participants were 104 daily smokers recruited across three related studies, assessing both nicotine reinforcement and tobacco cue-reactivity, conducted at two sites (Baltimore, Maryland, United States and Toronto, Ontario, Canada). Participants were recruited from the community at both the Baltimore (n = 55) and the Toronto (n = 49) sites between 2011 and 2018. Previous analyses reported using this pooled dataset include the impact of dopamine D3 and cannabinoid CB1 receptor polymorphisms on nicotine reinforcement and cue-reactivity.33,34 In addition, data from this pooled sample have been reported with rat data to assess translational commonalities in laboratory assessment of nicotine reinforcement and cue-reactivity.35 Studies were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (7th revision) and were approved by ethics review boards at the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) and the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH). Participants were 18–64 years old, smoked ≥10 cigarettes per day for at least 1 year, had a positive urinary cotinine test, and were medically and psychologically healthy (assessed by medical and psychiatric history). Participants were ineligible if they were seeking treatment for nicotine dependence, recently used nicotine replacement products, consumed >15 alcoholic drinks per week, used illicit drugs regularly (>twice per week during the previous month including cannabis), were pregnant/nursing, or used medications that would knowingly impact nicotine metabolism or disrupt the experimental session protocols more generally (eg, due to dosing regimen).

Study Design

Full study details are described in Chukwueke et al.33 Briefly, participants attended an eligibility assessment where informed consent was obtained followed by collection of demographic and tobacco use related data, including the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND),36 medical/psychiatric history, and verification of smoking status (positive urine cotinine), illicit drug use (negative urine screen), recent drinking (negative breath alcohol), and recent smoking (positive breath carbon monoxide). Females were additionally required to provide a negative urine pregnancy test. Eligible participants completed a forced-choice task to assess nicotine reinforcement at a second study visit, and a cue-exposure task to assess cue-reactivity at a third and final study visit. All participants provided a blood sample allowing for genotypic analysis of CYP2A6 activity. In addition, 55 participants provided blood at the eligibility visit for quantification of cotinine and 3HC (for assessment of the NMR).

Forced-Choice Task

Relative reinforcing effects of nicotine were assessed with a forced-choice procedure.37 First, participants took four puffs of their preferred-brand cigarette to standardize time from last nicotine exposure. After 30–60 minutes, participants were presented with two identical research cigarettes, one with nicotine and one without (ie, denicotinized). In four counterbalanced exposure trials separated by 20–30-minute intervals (to avoid nicotine satiation and simulate regular smoking behavior, approx. eight puffs every 40 minutes38), participants took four puffs of a cigarette in counterbalanced order so that each cigarette was sampled twice. After 20–30 minutes following the last exposure trial, participants completed four choice trials separated by 20–30-minute intervals. In each trial, participants were presented with both nicotine-containing and denicotinized cigarettes concurrently and instructed to smoke any combination of four puffs from either or both cigarettes. The percentage of nicotine-containing cigarette choices was used as an objective indicator of nicotine reinforcement.

Forced-Choice Cigarettes

Due to product availability at each study site, it was not possible to use the same research cigarettes across all participants. Nicotine-containing cigarettes included Quest 1 cigarettes (Vector Tobacco, 0.6 mg nicotine yield), commercially available Player’s brand cigarettes, and SPECTRUM research cigarettes (RTI international, 0.9 mg nicotine yield). The denicotinized cigarettes used were Quest 3 cigarettes (<0.05 mg nicotine yield) and SPECTRUM research cigarettes (0.03 mg nicotine yield).

Cue-Exposure Task

Cue-induced craving in response to smoking and neutral cues was assessed with a cue-exposure task based on Weinberger et al.39 To begin, participants took four puffs of their preferred-brand cigarette to standardize time from last nicotine exposure. Cue exposure started 30–60 minutes after the last puff with the order of smoking and neutral exposure sessions counterbalanced across participants. The smoking cue consisted of a pack of cigarettes, a lighter, and an ashtray. Participants were instructed to light a cigarette from the pack without puffing and hold it for 30–60 seconds before extinguishing the cigarette. The neutral cue was a pack of pencils, a sharpener, and a notepad. Participants were instructed to sharpen a pencil and hold it as if writing for 30–60 seconds. To assess cue-reactivity, participants completed visual analogue scales (VAS) for “urge to smoke” and “cigarette craving” and the Tobacco Craving Questionnaire—Short Form (TCQ-SF)40 prior to cue exposure (baseline) and 15 minutes after cue exposure (post). Difference scores (post − baseline) were computed as an index of cue-reactivity.

Genotyping

Variants were selected from previous GWASs of the NMR (a biomarker of CYP2A6 activity4), and included rs56113850, rs2316204, rs113288603, rs12459249, rs111645190, and rs185430475.5,7 We also selected established reduced or loss-of-function CYP2A6* variant alleles (CYP2A6*2 (rs1801272), *7 (rs5031016), *9 (rs28399433), *17 (rs28399454), *20 (rs568811809), *23 (rs56256500), *25/*26/*27 (all tagged by rs28399440), *28 (rs28399463), *31 (rs72549432), and *35 (rs143731390)). These single nucleotide polymorphisms and frameshift deletion were genotyped by qPCR approaches including TaqMan and two-step PCR assays (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) as previously described.8,31,32 Structural variants (CYP2A6*1X2 (gene duplication), *4 (gene deletion), and *12 (gene hybrid)) were determined through TaqMan copy number assays (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol and previous studies.41 Genotype frequencies for each variant were in Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (p > .05) in each race.

Genetic Groupings Based Exclusively on CYP2A6* Variant Alleles

All 104 participants, regardless of race, were grouped into reduced or normal metabolizers based on the presence of genotyped functionally characterized CYP2A6* variant alleles (ie, CYP2A6*2, *7, *9, *17, *20, *23, *25/*26/*27, *28, *31, and *35). All individuals whose genotype included one of these CYP2A6* variant alleles, or some combination of these * variant alleles, were defined as reduced metabolizers. Individuals with none of these CYP2A6* variant alleles were defined as normal metabolizers.8

Genetic Groupings Based on wGRS Analyses

A CYP2A6 wGRS defined for populations with African and European ancestries (AFR and EUR) has been described elsewhere.31,32 Briefly, these wGRSs included a combination of selected CYP2A6* alleles and independent signals identified from GWASs of the NMR. These wGRSs capture 30%–35% of the variation of log-transformed NMR in their respective ancestral populations. Since these wGRSs have only been described in those with AFR and EUR, wGRS-based grouping was restricted to the 94 participants reporting AFR and EUR. The AFR wGRS was applied to those reporting AFR and included 11 variants: independent signals from AFR-stratified GWAS analyses (rs12459249, rs111645190, rs185430475) and CYP2A6* alleles common in AFR populations (*1x2, *4, *9, *12, *17, *20, *25, and *35).32 The EUR wGRS was applied to those reporting EUR and included seven variants: independent signals from EUR-stratified GWAS analyses (rs56113850, rs2316204, rs113288603) and CYP2A6* alleles common in EUR populations (*2, *4, *9, and *12).31

An individual’s wGRS was calculated based on the weights previously identified for the respective ancestral population where the number of effect alleles present was multiplied by the respective allele weightings. For the purposes of dichotomous analyses (slow and fast metabolizers), optimal wGRS cutpoints that dichotomize slow and fast metabolizers were used.31,32 These optimal cutpoints are based on a previous NMR cutpoint implicated in unique smoking cessation outcomes. Slow (NMR <0.31): wGRS <2.089 in AFR or <2.140 in EUR. Fast (NMR ≥0.31): wGRS ≥2.089 in AFR or ≥2.140 in EUR. For the purposes of correlation and linear regression analyses, to integrate both ancestral populations onto the same scale, the respective AFR and EUR wGRS values were transformed to predicted log-NMR values. This was achieved by calculating the predicted log-NMR from the respective line equations of the wGRSs. For AFR populations, the predicted log-NMR = 1.0502 (AFR wGRS score) − 2.7042. For EUR populations, the predicted log-NMR = 0.684 (EUR wGRS) − 1.9417.

Determination of Cotinine, 3HC, and the NMR

The NMR (ie, a CYP2A6 activity phenotype measure) was determined for the 55 participants recruited at the Baltimore site as the ratio between nicotine’s major metabolites, 3HC and cotinine. Lower 3HC/cotinine ratios are indicative of slower CYP2A6 activity and slower nicotine clearance. The concentrations of these metabolites were measured from plasma by liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC–MS/MS) as described elsewhere.42 Briefly, 0.100 mL plasma was used for analysis, deuterated internal standards were utilized, and cotinine and 3HC were extracted from sample matrix using liquid–liquid extraction. Samples were analyzed by LC–MS/MS equipped with atmospheric-pressure chemical ionization (APCI) ion source. Limits of quantification were 1 ng/mL for cotinine and 1 ng/mL for 3HC.

Data Analyses

Descriptive statistics were calculated for demographic data on the whole sample (n = 104) and when split by normal/reduced metabolizer groups. FTND score was missing from one participant, and it was not possible to classify another participant as either a normal or reduced metabolizer. Demographic variables were compared across normal and reduced metabolizer groups with Chi square and independent samples t tests for categorical and continuous variables, respectively.

To assess the impact of normal versus reduced metabolizer grouping on nicotine reinforcement and cue-reactivity, three-way analyses of variance were conducted with percentage of nicotine puff choices and the cue-induced craving measures as dependent variables. Independent variables were genetic group (normal vs. reduced), race (Black vs. Caucasian vs. Other), and sex (male vs. female). A priori power calculations indicated that medium-to-large effect sizes and 104 participants would achieve power of >0.8. For nicotine reinforcement, analyses were conducted on n = 103 for whom genetic grouping was possible. Cue-reactivity data were missing from an additional participant, so analyses were conducted on n = 102. We sought to confirm normal/reduced metabolizer findings using the wGRS-based fast/slow metabolizer grouping, which was available for participants with AFR and EUR ancestry (n = 94; see Supporting Information).

Multiple linear regression models were used to test the association of wGRS-derived NMR with both nicotine reinforcement and cue-reactivity outcome measures. Percentage of nicotine puff choices and cue-induced craving measures were the dependent variables. wGRS-derived NMR was the main predictor variable and to control for race and sex these were included as additional predictors. A priori power calculations indicated that medium-to-large effect sizes and 104 participants would achieve power of >0.9. The model for nicotine reinforcement included data from participants with AFR and EUR (n = 94). Cue-reactivity data were missing from one participant, so analyses were conducted on n = 93. Finally, using correlation analyses (Pearson’s r), actual NMR measured in a subset of participants (n = 55) was used to verify the predicted NMR derived from the wGRS.

As race and sex differences have been reported in NMR/CYP2A6 genetic variant frequencies43,44 and smoking behavior,24,45 we included race and sex as factors/predictors in the main analyses presented. For three-way analyses of variance, assumptions of normality were checked by inspecting frequency and Q–Q plots and skew and kurtosis values,46 and the assumption of homogeneity of variance was checked with Leven’s test. For multiple linear regression models, assumptions of linearity, heteroskedasticity, multicollinearity, influential cases, and normality of residuals were checked by inspecting scatter plots for variables and residuals, variance inflation factors (all were below 2), Cook’s distances (all were below 0.5) and assessing normality as described above, respectively. Normality assumptions for several analyses were violated and transformation of variables improved this. As such, percentage of nicotine puff choices data were rank transformed (using the rntransform function in the GenABEL package of RStudio) and NMR data (actual and predicted) were log transformed. Statistical analyses were conducted in SPSS (v24, IBM Corp.) with the significance threshold set at α = 0.05.

Results

Demographics

Demographic and smoking-related characteristics are shown in Table 1 for the total sample (n = 104) and for the normal and reduced metabolizer groups. There were more males than females in the normal metabolizer group and the opposite was true for the reduced metabolizer group. Caucasians were over-represented in the normal metabolizer group, whereas there were more Black than Caucasian participants in the reduced metabolizer group. Our planned analyses included race and sex as covariates of interest as detailed above. Participants in the normal metabolizer group were also significantly older and had been smokers for significantly longer than those in the reduced metabolizer group.

Table 1.

Demographics for the Total Sample and by Normal/Reduced Metabolizer Group

| Total (n = 104) | NM (n = 71) | RM (n = 32) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | Significance (NM vs. RM) | ||

| Demographic characteristics | |||||

| Sex | Male | 57 (54.8) | 44 (62.0) | 12 (37.5) | |

| Female | 47 (45.2) | 27 (38.0) | 20 (62.5) | χ2(1) = 5.33, p = .032 | |

| Race | Black | 31 (29.8) | 17 (23.9) | 13 (40.6) | |

| Caucasian | 63 (60.6) | 52 (73.2) | 11 (34.4) | ||

| Other | 10 (9.6) | 2 (2.8) | 8 (25.0) | χ2(2) = 18.74, p < .001 | |

| Education | >High school | 63 (60.6) | 43 (60.6) | 19 (59.4) | χ2(1) = 0.01, p = 1.000 |

| Mean (SEM) | Mean (SEM) | Mean (SEM) | |||

| Age (years) | 41.80 (1.09) | 43.34 (1.30) | 38.38 (1.91) | t(101) = 2.13, p = .036 | |

| Smoking characteristics | |||||

| Cigarettes per day | 17.48 (0.57) | 18.06 (0.69) | 16.09 (1.04) | t(101) = 1.59, p = .116 | |

| Number of smoking years | 22.27 (1.12) | 24.32 (1.37) | 17.72 (1.78) | t(101) = 2.79, p = .006 | |

| FTND | 5.35 (0.19)a | 5.37 (0.24)b | 5.38 (0.28) | t(100) = −0.01, p = .993 |

FTND = Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence, NM = normal metabolizer, RM = reduced metabolizer, SEM = standard error of the mean. Note that NM/RM grouping was available for 103 of the 104 participants. Analyses presented are Chi square and independent samples t tests for categorical and continuous variables, respectively.

Bold values indicate significance.

aScore available for n = 103.

bScore available for n = 70.

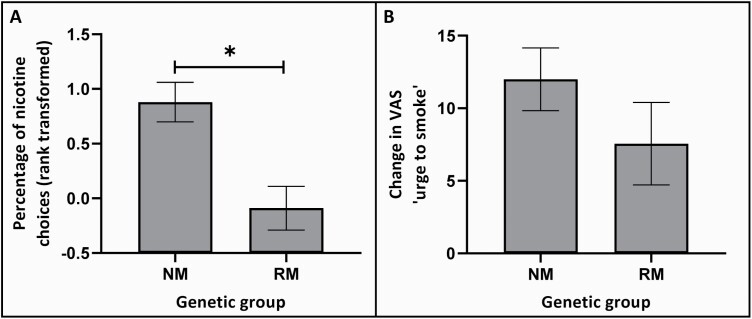

Normal Versus Reduced Metabolizers Display Greater Nicotine Reinforcement

Comparing normal with reduced metabolizers on the percentage of nicotine choices on the forced-choice task, there was a significant main effect of genetic group (F(1,92) = 4.77, p = .031, ) such that normal (vs. slower) metabolizers made more nicotine-containing cigarette choices (Figure 1). Overall, selection of high nicotine yield cigarette puffs occurred approximately 80% of the time for those in the normal metabolizer group compared with 60% for those in the reduced metabolizer group (mean cigarette choice data (untransformed) split by normal/reduced metabolizer group are shown in Supplementary Table S1). Main effects of race (F(2,92) = 1.30, p = .278) and sex (F(1,92) = 0.95, p = .332) and interactions between genetic group and these factors (genetic group × race: F(2,92) = 0.08, p = .922; genetic group × sex: F(1,92) = 0.33, p = .565) were all nonsignificant. The significant genetic group effect was replicated in supplementary analyses when splitting participants into fast and slow metabolizer groups based on their wGRS (participants with AFR and EUR ancestry only). Supplementary t tests showed that the percentage of nicotine choices was significantly higher for fast metabolizers than for slow metabolizers. However, adding race and sex as factors resulted in the loss of this main effect, possibly due to the loss of power in this subanalysis (see Supplementary Figure S1).

Figure 1.

Nicotine reinforcement (A) and cue-reactivity (B) by normal and reduced metabolizer group. Data represent means and error bars the standard error of the mean. Abbreviations: NM = normal metabolizer, RM = reduced metabolizer, *NM versus RM: p < .05.

Normal and Reduced Metabolizers Display Equivalent Cue-Reactivity

For the tobacco cue-reactivity outcome measure, change in VAS “urge to smoke,” there were no significant main effects of genetic group (F(1,91) = 0.50, p = .480), race (F(2,91) = 1.63, p = .202), or sex (F(1,91) = 0.26, p = .609) and the interaction terms between genetic group with race and with sex were also nonsignificant (genetic group × race: F(2,91) = 1.57, p = .213; genetic group × sex: F(1,91) = 0.92, p = .340). Data are shown in Figure 1 (mean change in VAS “urge to smoke” data split by normal/reduced metabolizer group are shown in Supplementary Table S1). Findings for the other cue-reactivity outcome measures (change in VAS “cigarette craving” and change in TCQ-SF) were similar (see Supplementary Table S2). Supplementary t tests showed that fast and slow groups based on the wGRS also did not differ in any of the cue-reactivity outcome measures (see Supplementary Table S3).

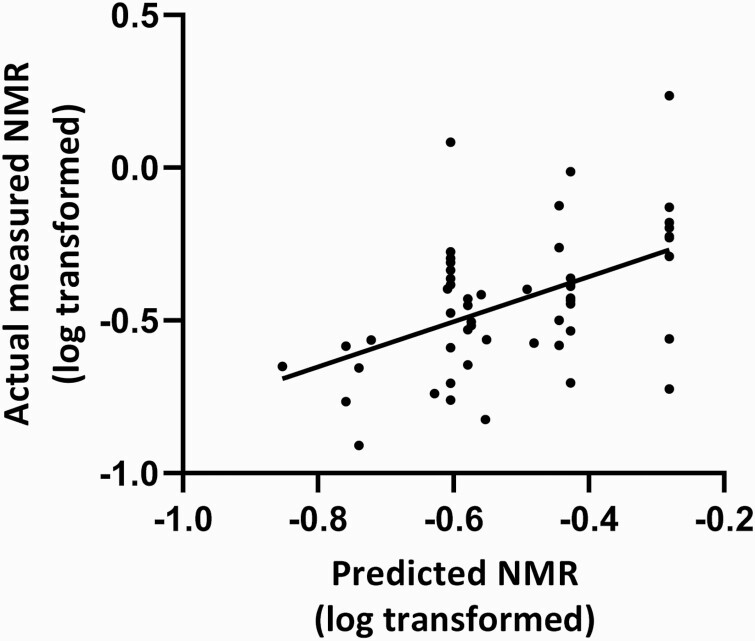

Correlation of Actual Measured NMR With Predicted NMR

Actual NMR measured in a subset of participants (n = 55) was positively correlated with predicted NMR (calculated from the wGRS) in this subset (r = 0.48, p < .001; Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Positive correlation between actual measured and predicted NMR. Abbreviation: NMR = nicotine metabolite ratio. Note that predicted NMR is calculated based on weighted genetic risk scores. Significant bivariate correlation between actual measured NMR (log transformed) and predicted NMR (log transformed), r = 0.48, p < .001, n = 55.

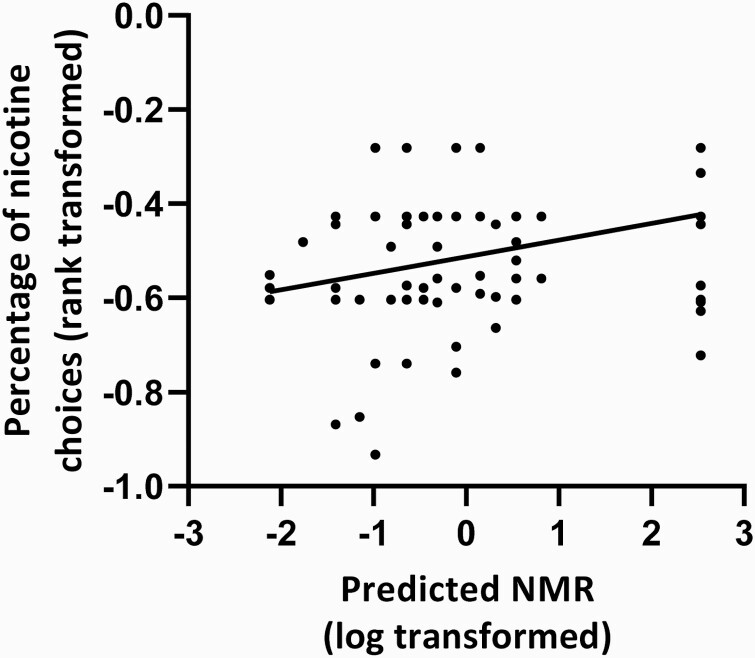

Predicted NMR Associated With Nicotine Reinforcement

Having validated the predicted NMR (calculated from the wGRS, see Figure 2), the association with nicotine reinforcement was tested. There was a significant positive association between predicted NMR (based on wGRS data) and the percentage of nicotine choices on the forced-choice task in a model controlling for race and sex (standardized β = 0.31, p = .015). Neither race nor sex were significantly associated with the percentage of nicotine choices in this model. The full regression model was also significant and predicted about 10% of the variability in the percentage of nicotine puff choices (see Table 2). The positive bivariate correlation between predicted NMR and the percentage of nicotine choices was significant (r = 0.35, p = .001, n=94), and the scatter plot showing this relationship is shown in Figure 3.

Table 2.

Association of Predicted NMR With Nicotine Reinforcement and Cue-Reactivity

| β | SE | t | p | Model fit | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nicotine choices (%)a | F(3,90) = 4.49, p = .006 | 0.101 | ||||

| Race | −0.07 | 0.40 | −0.59 | .558 | ||

| Sex | 0.05 | 0.30 | 0.49 | .626 | ||

| Predicted NMRb | 0.31 | 1.25 | 2.48 | .015 | ||

| Change in VAS “urge to smoke” | F(3,89) = 0.23, p = .875 | −0.026 | ||||

| Race | −0.03 | 4.87 | −0.22 | .830 | ||

| Sex | 0.06 | 3.67 | 0.59 | .555 | ||

| Predicted NMRb | 0.04 | 15.30 | 0.31 | .757 |

β = standardized beta, NMR = nicotine metabolite ratio, , SE = standard error of the regression coefficient, VAS = visual analogue scale. Note that predicted NMR data are based on weighted genetic risk scores.

Bold values indicate significance.

aRank-transformed data.

bLog-transformed data.

Figure 3.

Positive correlation between nicotine reinforcement and predicted NMR. Abbreviation: NMR = nicotine metabolite ratio. Note that predicted NMR is calculated based on weighted genetic risk scores. Significant bivariate correlation between predicted NMR (log transformed) and percentage of nicotine choices (rank transformed), r = 0.35, p = .001, n = 94.

Lack of Association Between Predicted NMR and Cue-Reactivity

In contrast, there was no significant association between predicted NMR (based on wGRS data) and the change in VAS “urge to smoke” cue-reactivity outcome measure in a model controlling for race and sex (standardized β = 0.04, p = .757). Similarly, neither race nor sex were themselves significantly associated with change in VAS “urge to smoke” in this model. The full regression model was also not significant (see Table 2). Findings for the other cue-reactivity outcome measures (change in VAS “cigarette craving” and change in TCQ-SF) were similar (see Supplementary Table S4).

Discussion

We investigated the effect of variation in CYP2A6 activity on an objective measure of nicotine reinforcement and cue-reactivity in daily smokers. Smokers with higher CYP2A6 activity exhibited increased nicotine reinforcement compared with those with lower activity. This was found regardless of whether CYP2A6 activity was indexed genetically (ie, normal vs. reduced nicotine metabolizers) or using the predicted CYP2A6 activity phenotype (ie, the NMR) calculated from the wGRS and when controlling for both race and sex. In contrast, CYP2A6 activity did not impact cue-reactivity, with normal and reduced metabolizers displaying equivalent changes in cue-induced craving following exposure to tobacco cues. This lack of relationship was confirmed using the predicted phenotype index of CYP2A6 activity and in supplementary analyses where grouping was performed based on the wGRS.

Consistent with our finding that CYP2A6 activity impacts nicotine reinforcement in a forced-choice task (with faster nicotine metabolizers exhibiting increased nicotine reinforcement), previous research suggests that subjectively assessed nicotine reinforcement is elevated in those with higher CYP2A6 activity.23 Additionally, studies showing that nicotine and smoking self-administration can be attenuated by prior administration of CYP2A6 inhibitors26,27 provides pharmacological support for the influence of CYP2A6 activity on nicotine reinforcement. As previous work indicates that nicotinic receptors have an important role in reward and reinforcement,47 it is interesting to note that reduced nicotinic receptor availability has been demonstrated in smokers with reduced nicotine metabolism.48 Additional research is required to establish whether differences in nicotine reinforcement attributable to CYP2A6 activity are mediated by altered nicotinic receptor availability.

Previous functional imaging findings suggest that CYP2A6 activity may affect reward processing more generally in smokers.49 In smokers, but not in nonsmokers, normal metabolizers (vs. reduced metabolizers) exhibited enhanced connectivity in neural circuits that subserve reward processes. Similar increases in neural activity were found in the ventral striatum in smokers with faster metabolism (relative to reduced metabolizers) when anticipating a gain (vs. a neutral condition) during abstinence.49 We speculate that increased nicotine reinforcement, or reward processing more generally, may contribute to increased dependence emergence risk and cigarette consumption, as well as poorer abstinence outcomes in individuals with faster CYP2A6 activity. Future studies might examine whether nicotine reinforcement and reward processing mediate the relationship between CYP2A6 activity and cigarette consumption, or between CYP2A6 activity and relapse in abstinent smokers.

Unlike studies indicating that neural cue-reactivity is influenced by CYP2A6 activity,29,30 we did not observe an effect on cue-induced craving measures with any of our CYP2A6 activity indices. Differences between findings may be due, in part, to differences in the methods used: neural and subjective cue-reactivity are assessed at different levels of enquiry, with neural activity likely indexing more than craving alone. Increased neural cue-reactivity in smokers with high CYP2A6 activity was reported after 24 hours of abstinence (compared with satiety) in one of the brain imaging studies,30 whereas in our study, cue-induced craving measures were performed under a single shorter abstinence duration (30–60 minutes) to standardize time since smoking across participants. CYP2A6 activity may therefore interact with abstinence duration to influence neural cue-reactivity, and further work is required to establish if this is the case for subjective craving responses. While we report positive change in “urge to smoke” scores in our minimally deprived smokers, smokers that have been abstinent for longer durations may be expected to exhibit greater cue-reactivity. For instance, abstinence-induced sensitization (or incubation) of cue-reactive craving has been reported when assessing cue-induced craving over a much longer 35-day abstinence period.50 Therefore, we cannot completely rule out CYP2A6 effects on cue-reactivity in smokers with longer abstinence durations and future research should address this. This could be tested directly in abstaining smokers. Alternatively, given translational commonalities between cue-induced craving in human smokers and cue-induced reinstatement of nicotine seeking in animals35 and that CYP2A6 inhibition attenuates nicotine self-administration,26 this could be tested preclinically by investigating the impact of pharmacological inhibition of CYP2A6 on cue-induced reinstatement of nicotine seeking after different durations of extinction. Another difference between our study and those assessing neural cue-reactivity is the stimuli presented in the cue-reactivity paradigms. In the brain imaging studies participants are presented smoking-related images inside a scanner, whereas in our study participants light a cigarette allowing for more immersive and naturalistic engagement with cues.

Our findings have implications for tobacco use disorder treatment and personalized medicine. Together with existing findings that CYP2A6 activity is, in some studies, associated with greater dependence as well as increased smoking behavior and decreased smoking cessation, our work further supports the clinical relevance of CYP2A6 activity as an effective pharmacological target for smoking cessation therapy. Our findings also suggest that smokers with high CYP2A6 activity or those that exhibit increased nicotine reinforcement may benefit most from such treatment. Further discussion of the optimization of smoking cessation therapy in relation to variable CYP2A6 activity has been covered elsewhere.51

The indices of CYP2A6 genetically predicted activity used in the current study were: (1) genetic stratification of reduced and normal metabolizers based on the presence or absence of reduced/loss-of-function variants in the CYP2A6 gene, (2) stratification (slow vs. fast metabolizers) based on a race-specific wGRSs (that are known to explain approximately 30%–35% of the variability in NMR,31,32 and (3) predicted log-transformed NMR calculated from the race-specific wGRS. We demonstrated consistent effects of CYP2A6 activity on nicotine reinforcement using each of these CYP2A6 genetically predicted activity indices. In addition, predicted NMR significantly correlated with measured NMR in the subset of 55 participants where nicotine metabolite data were available. The assessment of actual NMR in all participants could be considered one way to strengthen the study. However, a strength of this study is that it provides evidence for the use of wGRS-derived NMR data, which could be used in future CYP2A6 activity studies where genetic information, but no nicotine metabolite data, are available. Another area which could be strengthened is more careful matching of participants. For instance, normal metabolizers reported having been smokers for longer than reduced metabolizers; this has been observed before and may be related to their greater failure in cessation attempts and thus longer duration smoking. This may have also been driven by age as normal metabolizers were slightly older than reduced metabolizers (see Table 1 and Supplementary Table S5 where we present an age by race and age by gender breakdown for all participants as well as split by metabolizer group). Although longer lifetime smoking might influence our findings, this remains speculative, as both normal and reduced metabolizers reported a substantial duration of lifetime smoking (mean >17 smoking years). The impact of smoking duration could be assessed in future studies that are powered to do so and that have larger variation in lifetime smoking durations among participants.

Controlling for both race and sex, this study demonstrated a positive association between CYP2A6 activity and nicotine reinforcement in daily smokers. In contrast, no association was observed between CYP2A6 activity and cue-induced craving in minimally deprived smokers. Increased nicotine reinforcement in high activity CYP2A6 smokers may contribute to increased smoking behaviors including higher cigarette consumption and poorer abstinence outcomes previously found to be associated with high CYP2A6 activity/faster nicotine metabolism. Our findings support the development of CYP2A6 targeting agents for smoking cessation and CYP2A6 activity as a clinically relevant biomarker that could be used to optimize personalized treatment strategies for tobacco use disorder.

Supplementary Material

A Contributorship Form detailing each author’s specific involvement with this content, as well as any supplementary data, are available online at https://academic.oup.com/ntr.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Chidera Chukwueke, Marie Gendy, and Richard Taylor for their contributions to participant recruitment, data collection, and data curation. The authors also thank Qian Zhou for performing genotyping experiments and Maria Novalen for assessments of cotinine and 3′-hydroxycotinine.

Funding

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Drug Abuse and the Pfizer 2011 GRAND Award (awarded to B Le Foll and S Heishman), the Canada Research Chairs program (RF Tyndale, the Canada Research Chair in Pharmacogenomics), the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (Foundation grant FDN-154294 and project grant PJY-159710 awarded to RF Tyndale), and the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. The funders provided salary support but did not have any additional role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Declaration of Interests

RF Tyndale has consulted for Quinn Emanuel and Ethismos Research Inc. B Le Foll has/will received in-kind medication donations from Pfizer, Bioprojet, and GW Pharma, in-kind cannabis product donations from Canopy and Aurora, and was provided a coil for TMS studies from Brainsway. All other authors report no conflict of interest for this study.

Data Availability

Data, research protocols, and information on materials used in this investigation will be made readily available upon request as allowed by the governing review boards of the involved research institutions.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Tobacco Factsheet, Updated 29 May 2019. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/tobacco. Accessed 1 June 2019.

- 2.Makate M, Whetton S, Tait RJ, et al. Tobacco cost of illness studies: a systematic review. Nicotine Tob Res. 2020;22(4):458–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jackson SE, McGowan JA, Ubhi HK, et al. Modelling continuous abstinence rates over time from clinical trials of pharmacological interventions for smoking cessation. Addiction. 2019;114(5):787–797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dempsey D, Tutka P, Jacob P III, et al. Nicotine metabolite ratio as an index of cytochrome P450 2A6 metabolic activity. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2004;76(1):64–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Loukola A, Buchwald J, Gupta R, et al. A genome-wide association study of a biomarker of nicotine metabolism. PLoS Genet. 2015;11(9):e1005498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buchwald J, Chenoweth MJ, Palviainen T, et al. Genome-wide association meta-analysis of nicotine metabolism and cigarette consumption measures in smokers of European descent [published online ahead of print March 10, 2020]. Mol Psychiatry. 2020. doi: 10.1038/s41380-020-0702-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chenoweth MJ, Ware JJ, Zhu AZX, et al. ; PGRN-PNAT Research Group . Genome-wide association study of a nicotine metabolism biomarker in African American smokers: impact of chromosome 19 genetic influences. Addiction. 2018;113(3):509–523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wassenaar CA, Zhou Q, Tyndale RF. CYP2A6 genotyping methods and strategies using real-time and end point PCR platforms. Pharmacogenomics. 2016;17(2):147–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Benowitz NL, Pomerleau OF, Pomerleau CS, Jacob P III. Nicotine metabolite ratio as a predictor of cigarette consumption. Nicotine Tob Res. 2003;5(5):621–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pan L, Yang X, Li S, Jia C. Association of CYP2A6 gene polymorphisms with cigarette consumption: a meta-analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;149:268–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu M, Jiang Y, Wedow R, et al. ; 23andMe Research Team; HUNT All-In Psychiatry . Association studies of up to 1.2 million individuals yield new insights into the genetic etiology of tobacco and alcohol use. Nat Genet. 2019;51(2):237–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pianezza ML, Sellers EM, Tyndale RF. Nicotine metabolism defect reduces smoking. Nature. 1998;393(6687):750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wassenaar CA, Dong Q, Wei Q, Amos CI, Spitz MR, Tyndale RF. Relationship between CYP2A6 and CHRNA5-CHRNA3-CHRNB4 variation and smoking behaviors and lung cancer risk. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103(17):1342–1346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Audrain-McGovern J, Al Koudsi N, Rodriguez D, Wileyto EP, Shields PG, Tyndale RF. The role of CYP2A6 in the emergence of nicotine dependence in adolescents. Pediatrics. 2007;119(1):e264–e274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chenoweth MJ, Sylvestre MP, Contreras G, Novalen M, O’Loughlin J, Tyndale RF. Variation in CYP2A6 and tobacco dependence throughout adolescence and in young adult smokers. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;158:139–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Olfson E, Bloom J, Bertelsen S, et al. CYP2A6 metabolism in the development of smoking behaviors in young adults. Addict Biol. 2018;23(1):437–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chenoweth MJ, O’Loughlin J, Sylvestre MP, Tyndale RF. CYP2A6 slow nicotine metabolism is associated with increased quitting by adolescent smokers. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2013;23(4):232–235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schnoll RA, Patterson F, Wileyto EP, Tyndale RF, Benowitz N, Lerman C. Nicotine metabolic rate predicts successful smoking cessation with transdermal nicotine: a validation study. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2009;92(1):6–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lerman C, Tyndale R, Patterson F, et al. Nicotine metabolite ratio predicts efficacy of transdermal nicotine for smoking cessation. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2006;79(6):600–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lerman C, Schnoll RA, Hawk LW Jr, et al. ; PGRN-PNAT Research Group . Use of the nicotine metabolite ratio as a genetically informed biomarker of response to nicotine patch or varenicline for smoking cessation: a randomised, double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2015;3(2):131–138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Benowitz NL. Nicotine addiction. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(24):2295–2303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Le Foll B, Wertheim C, Goldberg SR. High reinforcing efficacy of nicotine in non-human primates. PLoS One. 2007;2(2):e230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sofuoglu M, Herman AI, Nadim H, Jatlow P. Rapid nicotine clearance is associated with greater reward and heart rate increases from intravenous nicotine. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37(6):1509–1516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liakoni E, Nardone N, St Helen G, Dempsey DA, Tyndale RF, Benowitz NL. Effects of nicotine metabolic rate on cigarette reinforcement. Nicotine Tob Res. 2020;22(8):1419–1423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liakoni E, Edwards KC, St Helen G, et al. Effects of nicotine metabolic rate on withdrawal symptoms and response to cigarette smoking after abstinence. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2019;105(3):641–651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen YC, Fowler JP, Wang J, et al. The novel CYP2A6 inhibitor, DLCI-1, decreases nicotine self-administration in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2020;372(1):21–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sellers EM, Kaplan HL, Tyndale RF. Inhibition of cytochrome P450 2A6 increases nicotine’s oral bioavailability and decreases smoking. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2000;68(1):35–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ferguson SG, Shiffman S. The relevance and treatment of cue-induced cravings in tobacco dependence. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2009;36(3):235–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tang DW, Hello B, Mroziewicz M, Fellows LK, Tyndale RF, Dagher A. Genetic variation in CYP2A6 predicts neural reactivity to smoking cues as measured using fMRI. Neuroimage. 2012;60(4):2136–2143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Falcone M, Cao W, Bernardo L, Tyndale RF, Loughead J, Lerman C. Brain responses to smoking cues differ based on nicotine metabolism rate. Biol Psychiatry. 2016;80(3):190–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.El-Boraie A, Taghavi T, Chenoweth MJ, et al. Evaluation of a weighted genetic risk score for the prediction of biomarkers of CYP2A6 activity. Addict Biol. 2020;25(1):e12741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.El-Boraie A, Chenoweth MJ, Pouget JG, et al. Transferability of ancestry-specific and cross-ancestry CYP2A6 activity genetic risk scores in African and European populations [published online ahead of print December 9, 2020]. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2020. doi: 10.1002/cpt.2135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chukwueke CC, Kowalczyk WJ, Di Ciano P, et al. Exploring the role of the Ser9Gly (rs6280) Dopamine D3 receptor polymorphism in nicotine reinforcement and cue-elicited craving. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):4085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chukwueke CC, Kowalczyk WJ, Gendy M, et al. The CB1R rs2023239 receptor gene variant significantly affects the reinforcing effects of nicotine, but not cue-reactivity, in human smokers. Brain Behav. 2021;11(2):e01982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Butler K, Forget B, Heishman SJ, Le Foll B. Significant association of nicotine reinforcement and cue reactivity: a translational study in humans and rats. Behav Pharmacol. 2021;32(2&3):212–219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerström KO. The Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence: a revision of the Fagerström Tolerance Questionnaire. Br J Addict. 1991;86(9):1119–1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jones JD, Comer SD. A review of human drug self-administration procedures. Behav Pharmacol. 2013;24(5–6):384–395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hatsukami DK, Pickens RW, Svikis DS, Hughes JR. Smoking topography and nicotine blood levels. Addict Behav. 1988;13(1):91–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weinberger AH, McKee SA, George TP. Smoking cue reactivity in adult smokers with and without depression: a pilot study. Am J Addict. 2012;21(2):136–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Heishman SJ, Singleton EG, Pickworth WB. Reliability and validity of a Short Form of the Tobacco Craving Questionnaire. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10(4):643–651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shimizu M, Koyama T, Kishimoto I, Yamazaki H. Dataset for genotyping validation of cytochrome P450 2A6 whole-gene deletion (CYP2A6*4) by real-time polymerase chain reaction platforms. Data Brief. 2015;5:642–645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tanner JA, Novalen M, Jatlow P, et al. Nicotine metabolite ratio (3-hydroxycotinine/cotinine) in plasma and urine by different analytical methods and laboratories: implications for clinical implementation. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2015;24(8):1239–1246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Murphy SE. Nicotine metabolism and smoking: ethnic differences in the role of P450 2A6. Chem Res Toxicol. 2017;30(1):410–419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen A, Krebs NM, Zhu J, Sun D, Stennett A, Muscat JE. Sex/gender differences in cotinine levels among daily smokers in the Pennsylvania Adult Smoking Study. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2017;26(11):1222–1230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Perkins KA, Jacobs L, Sanders M, Caggiula AR. Sex differences in the subjective and reinforcing effects of cigarette nicotine dose. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2002;163(2):194–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kim HY. Statistical notes for clinical researchers: assessing normal distribution (2) using skewness and kurtosis. Restor Dent Endod. 2013;38(1):52–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brunzell DH, Stafford AM, Dixon CI. Nicotinic receptor contributions to smoking: insights from human studies and animal models. Curr Addict Rep. 2015;2(1):33–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dubroff JG, Doot RK, Falcone M, et al. Decreased nicotinic receptor availability in smokers with slow rates of nicotine metabolism. J Nucl Med. 2015;56(11):1724–1729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li S, Yang Y, Hoffmann E, Tyndale RF, Stein EA. CYP2A6 genetic variation alters striatal-cingulate circuits, network hubs, and executive processing in smokers. Biol Psychiatry. 2017;81(7):554–563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bedi G, Preston KL, Epstein DH, et al. Incubation of cue-induced cigarette craving during abstinence in human smokers. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;69(7):708–711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chenoweth MJ, Tyndale RF. Pharmacogenetic optimization of smoking cessation treatment. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2017;38(1):55–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data, research protocols, and information on materials used in this investigation will be made readily available upon request as allowed by the governing review boards of the involved research institutions.