Abstract

Background

Aspergillus species cause aflatoxin contamination in groundnut kernels, being a health threat in agricultural products and leading to commodity rejection by domestic and international markets. Presence of Aspergillus flavus and A. parasiticus colonizing groundnut in eastern Ethiopia, as well as presence of aflatoxins have been reported, though in this region, no genetic studies have been done of these species in relation to their aflatoxin production.

Results

In this study, 145 Aspergillus isolates obtained from groundnut kernels in eastern Ethiopia were genetically fingerprinted using 23 Insertion/Deletion (InDel) markers within the aflatoxin-biosynthesis gene cluster (ABC), identifying 133 ABC genotypes. Eighty-four isolates were analyzed by Ultra-Performance Liquid Chromatography (UPLC) for in vitro aflatoxin production. Analysis of genetic distances based on the approximately 85 kb-ABC by Neighbor Joining (NJ), 3D-Principal Coordinate Analysis (3D-PCoA), and Structure software, clustered the isolates into three main groups as a gradient in their aflatoxin production. Group I, contained 98% A. flavus, including L- and non-producers of sclerotia (NPS), producers of B1 and B2 aflatoxins, and most of them collected from the lowland-dry Babile area. Group II was a genetic admixture population of A. flavus (NPS) and A. flavus S morphotype, both low producers of aflatoxins. Group III was primarily represented by A. parasiticus and A. flavus S morphotype isolates both producers of B1, B2 and G1, G2 aflatoxins, and originated from the regions of Darolabu and Gursum. The highest in vitro producer of aflatoxin B1 was A. flavus NPS N1436 (77.98 μg/mL), and the highest producer of aflatoxin G1 was A. parasiticus N1348 (50.33 μg/mL), these isolates were from Gursum and Darolabu, respectively.

Conclusions

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that combined the use of InDel fingerprinting of the ABC and corresponding aflatoxin production capability to describe the genetic diversity of Aspergillus isolates from groundnut in eastern Ethiopia.

Three InDel markers, AFLC04, AFLC08 and AFLC19, accounted for the main assignment of individuals to the three Groups; their loci corresponded to aflC (pksA), hypC, and aflW (moxY) genes, respectively. Despite InDels within the ABC being often associated to loss of aflatoxin production, the vast InDel polymorphism observed in the Aspergillus isolates did not completely impaired their aflatoxin production in vitro.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12866-021-02290-3.

Keywords: Aflatoxin, Aspergillus, Genetic diversity, Peanut, Insertion/deletion markers

Background

Groundnut (A. hypogaea L.) is an annual legume, important as a source of nutrition and income around the world. Ethiopia currently produces 78,475 MT of this crop [1], with the eastern parts of the country, mainly the East Hararghe region, accounting for 43% of groundnut production, where is replacing major crops in the area [2]. However, groundnut production and quality are hampered by the presence of Aspergillus fungi on kernels [3–5].

Aspergillus is a genus consisting of many species with worldwide distribution and adaptation to various climates [6]. Within the genus Aspergillus, section Flavi includes economically important species that can be divided into two main groups: the aflatoxigenic species (e.g. A. flavus, A. parasiticus, and A. nomius) and the non-aflatoxigenic species which include the domesticated (e.g. A. oryzae and A. sojae) [7] and the naturally occurring non-aflatoxigenic A. flavus strains [8–11]. The morphological complex species A. flavus [12] has two sclerotium-size morphotypes: the large (L)-morphotype, which produces few sclerotia that are > 400 μm in diameter and numerous conidiophores, and the small (S)-morphotype, which produces numerous sclerotia < 400 μm in diameter in association with few conidiophores [13]. Other isolates show typical A. flavus morphology though apparently have lost their ability to produce sclerotia in culture medium [12, 14, 15]. In the present work, isolates were grouped according to those general morphotypes, and those that did not produce sclerotia were referred as NPS.

Aflatoxins are mycotoxins produced primarily by species from Aspergillus section Flavi, such as A. flavus, A. parasiticus, and A. nomius. Many commodities used for human and animal consumption are contaminated with these toxins [16], which are known to be mutagenic, teratogenic, carcinogenic, and immunosuppressive [16, 17]. Fungi from section Flavi are able to produce: B1, B2, G1, and G2 aflatoxins, with type B1 being the most potent carcinogen known in nature [18]. Other aflatoxins such as M1 are naturally produced by A. flavus NRRL3251 [19], and other A. flavus isolates produce aflatoxins M1 and M2 [20].

Research has shown widespread presence of aflatoxins in groundnut and groundnut products in African countries [21, 22]. In eastern Ethiopia, reports of presence of Aspergillus spp. and aflatoxins in groundnut products has aimed to raise awareness of the risk such contamination poses to human health [4, 5, 23]. From hepatocellular carcinoma to growth impairment, aflatoxin contamination of food stuff is a constant threat [24, 25], and every few years aflatoxicosis results in human casualties [26].

Few technologies and methods are available to prevent the impact of aflatoxin contamination [27, 28] but these are often not affordable in developing countries. One strategy is the application of atoxigenic strains that can out-compete the toxigenic ones. For example, the product Afla-guard®, that contains the atoxigenic strain of A. flavus NRRL 21882, was able to reduce 88% of aflatoxin contamination in peanut fields [29]. However, not all geographic areas are colonized by the same strains of Aspergillus, for example, West African A. flavus S morphotype isolates differed from North American isolates in aflatoxin type and quantity produced [30]. Therefore, biocontrol programs with Aspergillus require understanding the population biology of this fungus in the region of interest before the control is implemented [31]. The most successful results in aflatoxin control have been accomplished by using native non-aflatoxin-producing strains [32]. One of the objectives of the present work was to identify the most common Aspergillus genotypes colonizing groundnut in Ethiopia by using ABC InDels to later subject them to whole-genome sequencing. Such information could be used in designing targets for RNA-interference-mediated gene silencing of aflatoxin synthesis genes that could be potentially effective against the most common genotypes. A secondary objective was to find non-aflatoxigenic isolates that could be used in biological control in the region. The workflow used in the present work performing InDel fingerprinting of the ABC of isolates has demonstrated this approach gives comparable results as cluster analysis of the complete ABC genomic sequences (~ 100 kb) of selected isolates [11].

Twenty-five genes are involved in aflatoxin biosynthesis in Aspergillus [33] and genetic diversity exists within the cluster among species [11, 34]. InDels within the ABC influence aflatoxin biosynthesis [35] which makes InDel marker a valuable tool for characterizing intraspecific variations [11]. InDel markers have been used to monitor non-aflatoxigenic A. flavus strains [36] and to distinguish groups according to their aflatoxin profile and genotype abundance in a geographic region [11].

There is a knowledge gap in the genetic diversity and aflatoxin production capacity of Aspergillus species in Ethiopia, which is hindering efforts to select non-aflatoxigenic Aspergillus isolates as potential biocontrol agents. In the current study, InDels were used to analyze the genetic diversity of Aspergillus species isolated from groundnut samples in eastern Ethiopia, and the production of aflatoxins was determined for selected isolates. Potential associations between fungal genotype and geographic area, as well as identification of the most frequent genotypes of Aspergillus in the groundnut-producing area of eastern Ethiopia are described.

Results

Genetic diversity of Aspergillus isolates

A total of 145 isolates of Aspergillus obtained from groundnut kernels collected during the 2014/15 season were evaluated (Supplementary Table 1); and the methodology for isolation and identification of these isolates has already been published [23]. Additional morphological observations of the isolates, such as colony color, conidia and sclerotium size indicated that A. flavus NPS was the predominant species (69%, n = 101) followed by A. parasiticus (15%, n = 22) and A. flavus S-morphotype (14%, n = 21), while A. flavus L-morphotype was the least abundant (1%, n = 2). A. flavus S- and L- morphotypes were distinguished by presence of sclerotia smaller or larger than 400 μm, respectively.

A total of 23 InDel markers utilized to assess the isolates for genetic variations within the ABC identified 133 different genotypes (Fig. 1), the DNA sequences of 22 of these markers had been published [11]. Most markers amplified all the isolates, but two markers, AFLC14 and AFLC25, did not amplify 31 and 26% of the isolates, respectively. Since the amount of DNA was not a limiting factor for other markers to detect amplicons, the lack of amplification in these two markers was considered as presence of null alleles. InDel markers detected a total of 123 amplicons, these ranged from 2 to 11 per marker, with an average of 5 (Table 1). All raw data of fingerprinting have been deposited at Harvard Dataverse repository, with persistent weblink: 10.7910/DVN/CXX0TG.

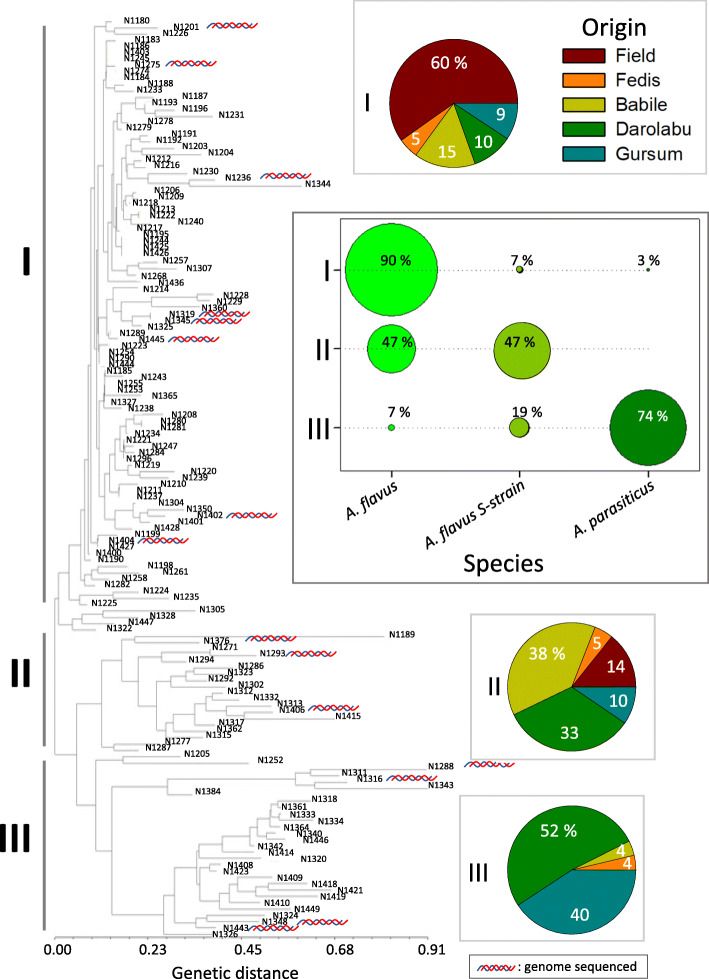

Fig. 1.

Neighbor Joining (NJ) analysis of the genetic distances estimated from the aflatoxin biosynthesis cluster. NJ of 145 Aspergillus isolates from groundnut kernels in Ethiopia based of genetic fingerprinting of 23 InDels in the aflatoxin-biosynthesis pathway. Three main groups were identified: Group I consisted mainly of A. flavus sclerotia-non producers (NPS). Group II included mainly A. flavus S-strain and A. flavus NPS, all producers of type B aflatoxin. Group III comprised primarily A. parasiticus with a small sub-clade of A. flavus S-strains, all producers of B and G aflatoxins. Symbol  : indicates isolates from which their genomes have been sequenced (Arias et al. 2020). Percentage of each of the species present within each group is indicated in a separate frame

: indicates isolates from which their genomes have been sequenced (Arias et al. 2020). Percentage of each of the species present within each group is indicated in a separate frame

Table 1.

InDel markers within the aflatoxin biosynthesis cluster used for fingerprinting Aspergillus species

| Marker name | Relative position | Forward 5′ → 3′ | Reverse 5′ → 3′ | Amplicon size range (bp) | Amplicons/sample (mean ± SE) | Number of amplicons | Fingerprint reference to raw data |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AFLC01 | 190–340 | CCGACCTCACGACGCATTAT | CCGGCTAGCTTCAACAGACG | 127–370 | 0.80 ± 0.36 | 6 | AFLC01 |

| AFLC02 | 1367–1521 | GGTTGGCGGATTGAGAGGTA | GGAGATCAGCCGAGAAGACA | 161–216 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 6 | AFLC02 – AFLC14 |

| AFLC03 | 5738–5868 | TCCGCCGAGAGCCATAATAG | GGATGCTGACACCTCGATAG | 152–155 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 3 | AFLC15 |

| AFLC04 | 7897–8073 | ACAGCTGGCATGCTCCGTAT | ATTGCTGCGCACGACGCTTA | 194–199 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 4 | AFLC16 |

| AFLC05 | 11633–11783 | GTGGATGGACTGCCACTTAG | AGACCACAGTGAGTGCTTCT | 161–195 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 9 | AFLC17 |

| AFLC06 | 12333–12543 | GCTGTCCTGGACGGATAGTA | CATCGGTCAACGACGAAGTA | 230–232 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 3 | AFLC18 |

| AFLC07 | 12715–12889 | GTCAGCAAGAGGAGCCTTCA | GGTCACGGAGATCCTCCATA | 160–197 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 3 | AFLC03 |

| AFLC08 | 14001–14235 | CGCCAGCACGGAGATCGAAT | CGTCTCCTCAGGCGGTCTAT | 243–257 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 5 | AFLC20 |

| AFLC09 | 16162–16331 | AACACTCCGCTGCTCAACTA | AACGCTCAGGCAACGTCGAA | 131–318 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 7 | AFLC04 |

| AFLC10 | 16315–16498 | GACGTTGCCTGAGCGTTAAT | TGACTGGTCGTCGCCAGAAT | 135–218 | 1.00 ± 0.08 | 9 | AFLC21 |

| AFLC11 | 21671–21862 | CTCGACGTAGCGTTGAACAG | AACGCATGGCCAGCTAATCT | 157–228 | 1.00 ± 0.11 | 5 | AFLC22 |

| AFLC12 | 21895–22149 | CGCAAGGAGCTCGACCAATA | TTCAGCTCAGCGACGAGAGT | 134–278 | 1.00 ± 0.19 | 6 | AFLC23 |

| AFLC13 | 22059–22241 | TCGGTTCAATGCTCGAACAC | TCCAACCTTCGGCCTAGTCT | 183–194 | 1.00 ± 0.08 | 3 | AFLC24 |

| AFLC14 | 22155–22242 | GACGCCTCGGCTTGTCAAGA | CTCCAACCTTCGGCCTAGTC | 96–121 | 0.80 ± 0.44 | 3 | AFLC05 |

| AFLC18 | 62617–62825 | GGCAGCCAGACCAAGGAATA | CCTTCTCGTAGCCGCTCATC | 230–231 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 2 | AFLC13 |

| AFLC19 | 63261–63509 | ACAGGACCGCACGGATCAAT | AGGAGCGGATGTCGAAGTCT | 260–270 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 6 | AFLC12 |

| AFLC20 | 67451–67735 | GCCTAGCGCTCCATTCTCAG | CCATCGTATCCGGCTCTATC | 262–369 | 1.00 ± 0.11 | 11 | AFLC11 |

| AFLC21 | 68690–68852 | TACCTTACTCCGCTAAGCAG | GCGGTCACCTACCAATGAAT | 169–321 | 1.00 ± 0.19 | 9 | AFLC10 |

| AFLC22 | 68718–68959 | TTCGCAGGAGTGTAGCCAAG | GTTGGAACACGCTCCATAGG | 259–269 | 1.00 ± 0.11 | 7 | AFLC09 |

| AFLC23 | 72035–72162 | GGCGTCAGTGGATTCCGGAT | CGTGGTCCGCAGCAATAGTG | 140–156 | 1.00 ± 0.11 | 3 | AFLC08 |

| AFLC24 | 73119–73357 | GAACGAGATAACGGCTGCAT | ATCAATCCACGGACCGTTGT | 260–261 | 1.00 ± 0.19 | 2 | AFLC06 |

| AFLC25 | 72652–72811 | CAGTGCGACCGGATGGTACA | CGGCTGAACGCGATGACTCT | 110–184 | 0.80 ± 0.39 | 5 | AFLC07 |

| AFLC26a | 13627–13702 | CGGCGTGGTGCGGTACTAAT | TAATACGCGCCGGCATCTCC | 89–95 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 6 | AFLC19 |

SE standard error of the mean

aMarker used only in this study, while the rest adopted from Faustinelli et al. [11]. Marker names in italics, correspond to the labels used in the raw data files of fingerprinting DOI: 10.15482/USDA.ADC/1520771

NJ analysis [37] distinguished three main groups of isolates, labelled as I, II, and III in Fig. 1. Group I (n = 97) was the largest, comprising mainly A. flavus (97%), most of them (91%) NPS, and few (7%) S-morphotype isolates. Group II (n = 21) had a similar number of A. flavus NPS (47%) and A. flavus S-morphotype (47%). Group III (n = 27) included mostly A. parasiticus (74%), followed by A. flavus S-morphotype (19%), and a small percentage of A. flavus NPS (7%), Fig. 1. The geographic origin of most isolates in Groups I and II, 75 and 52%, respectively, was mainly from the low-land dry area of Babile, which includes samples labelled Field and Babile. Whereas isolates in Group III were mainly from Darolabu (52%) and Gursum (40%), Fig. 1.

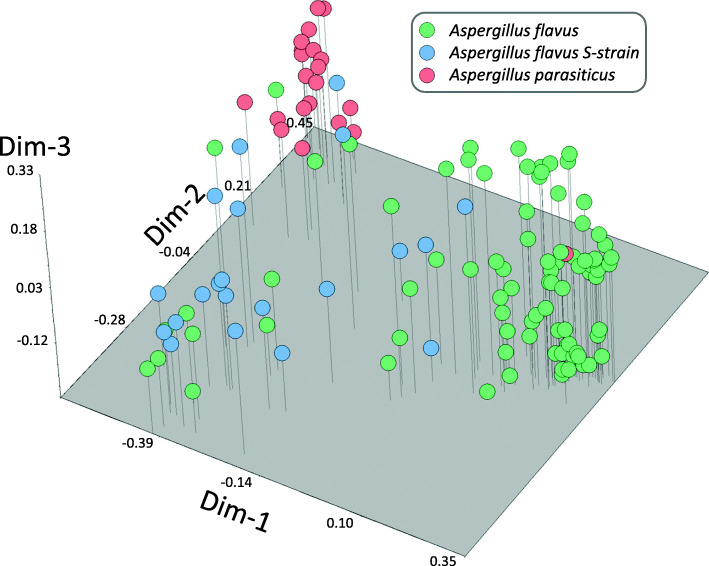

A 3-D Principal Coordinate Analysis (3D-PCoA) was evaluated from binary data of DNA fingerprinting used in Neighbor Joining analysis, Fig. 2. The 3D-PCoA categorized by species showed that the first three coordinates explained 88% of the total observed variation. The first coordinate (Dim-1; 53%) clustered together most of the A. flavus that belong to Group I in NJ analysis; whereas the second coordinate (Dim-2; 22%) discriminated Group II (mostly A. flavus S-morphotype) from Group III (mostly A. parasiticus), Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

3D-Principal Coordinate Analysis (3D-PCoA) of groundnut Aspergillus isolates. 3D-PCoA of 145 Aspergillus isolates from groundnut from eastern Ethiopia using 23 InDel markers. The first coordinate (Dim-1) distinguished most of the A. flavus that belong to Group I. The second coordinate (Dim-2) contributed to the differentiation of Group II (most of them A. flavus S-strain) and Group III containing mainly A. parasiticus isolates

Structure analysis was done for different values of parameter K. The K value that captured the major structure in our data was K = 2 (ΔK = 1231.9) indicating that based on the data of ABC fingerprinting there were only two major genetic groups, A. flavus and A. parasiticus. The A. flavus group was formed mainly by isolates from the Babile area, whereas the A. parasiticus group contained isolates mainly from Darolabu and Gursum.

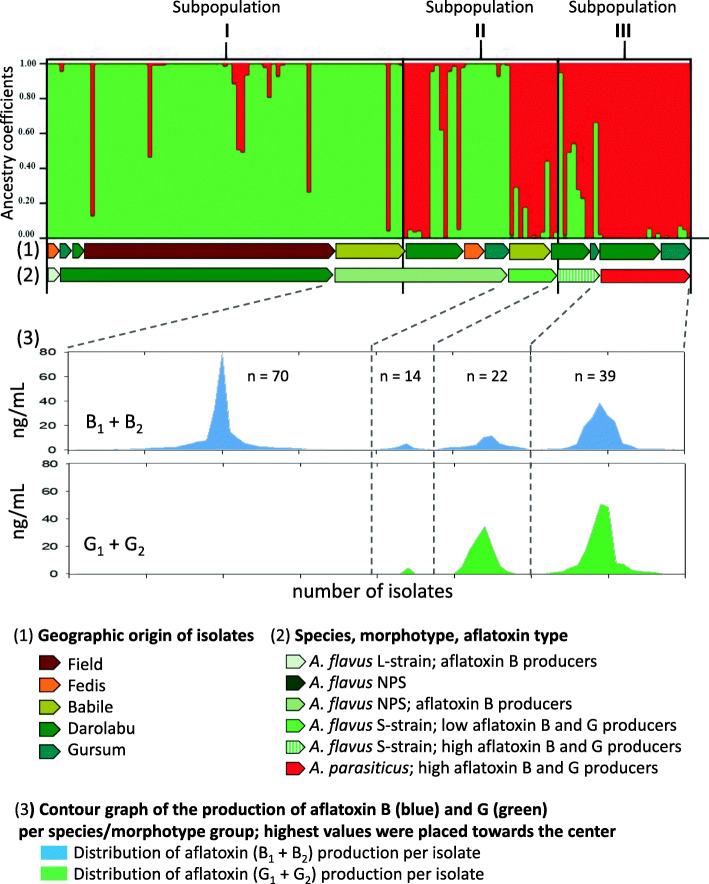

In our study, the detected partition consisted of three Groups. Group I contained most of the A. flavus-NPS that produced aflatoxins B1 and B2 (henceforth referred as type B) and geographically originated from the Babile area (Field + Babile), Fig. 3. Group II was a transitional admixture group, containing A. flavus NPS producing only low levels of aflatoxin B, and S-morphotype producing low levels of type B aflatoxins as well as aflatoxins G1 and G2 (henceforth referred as type G); this Group comprised isolates from all the areas tested. Group III included mostly A. parasiticus followed by A. flavus S-morphotype, both groups being producers of aflatoxin type B and G, and mostly originated from the highland-humid areas of Darolabu and Gursum, Fig. 3. NJ groups I and III had 79 and 89% of the same isolates as Group I and III from the Structure analysis, respectively.

Fig. 3.

Population Structure Analysis of groundnut Aspergillus isolates. Population structure of 145 isolates from eastern Ethiopia evaluated using genetic fingerprinting of 23 InDels within the aflatoxin-biosynthesis gene cluster. K = 2; ΔK = 1231.9

Some common features were found within Groups by DNA fingerprinting of InDels using capillary electrophoresis. For example, for marker AFLC19, most of the isolates in Group I presented a 2 bp deletion when compared to Group II, or 3 bp deletion if compared to Group III. Marker AFLC19 is located within the aflW (moxY) gene, and only few samples showed null alleles for this locus. In Group II, comprised by A. flavus NPS aflatoxin-B producers and A. flavus S-morphotype, both producing almost exclusively B-aflatoxins, most of the individuals were distinguished from other Groups by a single allele in marker AFLC08. The polymorphic locus of AFLC08 is in the intergenic region between the hypC and aflD genes. Finally, all isolates from Group III were distinguished from the other Groups by a single allele in marker AFLC04 with locus on the pksA gene which encodes a polyketide synthase at the beginning of the aflatoxin biosynthesis pathway.

In vitro aflatoxin production of Aspergillus isolates

Aflatoxins B1, B2, G1, and G2 were screened in 84 isolates obtained from groundnut kernels. Average aflatoxin production by each type of isolates is shown in Table 2, and the complete list of results are shown in Additional file 1. The highest aflatoxin B1 producer (A. flavus NPS N1436 from Gursum; 77.98 μg/mL), and the highest aflatoxin G1 producer (A. parasiticus N1348 from Darolabu; 50.33 μg/mL) were found within Groups I and III, respectively. The 62 isolates from Field experiments were not evaluated for aflatoxin production as these came from the same Babile location from where many other samples had already been analyzed for aflatoxin production and had shown genetic similarity by clustering together both in Neighbor Joining as in Structure analyses.

Table 2.

Average aflatoxins produced by isolates

| AFLATOXINS (μg/mL) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ISOLATES | B1 | B2 | G1 | G2 |

| Mean ± SE | Mean ± SE | Mean ± SE | Mean ± SE | |

| A. flavus L-strain (n = 2) | 14.16 ± 11.12 | 0.21 ± 0.17 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 |

| A. flavus NPS (n = 39) | 4.94 ± 2.16 | 0.10 ± 0.05 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 |

| A. parasiticus (n = 22) | 7.26 ± 2.42 | 0.26 ± 0.08 | 8.74 ± 3.27 | 0.12 ± 0.05 |

| A. flavus S-strain (n = 21) | 2.89 ± 0.64 | 0.09 ± 0.02 | 12.5 ± 2.53 | 0.13 ± 0.03 |

High values highlighted in bold

n number of individuals, SE standard error of the mean

Discussion

This is the first study that characterized the genetic diversity of the ABC of Aspergilli section-Flavi by combining InDel fingerprinting of their ABC and the corresponding aflatoxin production of isolates collected from groundnuts in eastern Ethiopia. Neighbor Joining and 3D-PCoA analyses based on DNA fingerprinting of 23 InDels within the ABC separated Ethiopian isolates in three groups: Group I, A. flavus which produced type B aflatoxin, Group II, an admix of A. flavus and A. flavus S-morphotype, both producers of low levels of aflatoxins, and Group III, A. parasiticus with a subclade of A. flavus S-morphotype, a group in which most isolates were high producers of G and B aflatoxins, Figs. 1 and 3. S-morphotype is known to produce both main types of aflatoxins, B and G [30, 38, 39]. Using the same InDels, genetic fingerprinting of Aspergillus isolates from groundnuts in Georgia, USA, also identified three main groups, though in that study, one group of isolates did not produce aflatoxins, and no S-morphotype were observed [11].

Even though Structure analysis of the Ethiopian isolates based on ABC InDels clearly distinguished two major genetic groups, corresponding mainly to A. flavus and A. parasiticus, a third group was observed using PCoA and NJ which are more robust to missing genotype data [40], positioned A. flavus S-morphotype as a transition group between those groups, Fig. 3. We estimated the ancestral components of 145 isolates of Aspergillus section Flavi from Ethiopia peanut kernels, using Structure program (K = 2) and 23 InDel markers. Group I to III represent groups with different ancestral components. Researchers working with RAPD data and the sequence of an amylase gene, had also placed A. flavus S-morphotype as phylogenetically intermediate between A. flavus and A. parasiticus [41]; more recently, several new species names have been proposed within the S-morphotype group [42–44]. The goal of the present work was to determine variations within the ABC and identify predominant genotypes in relation to their aflatoxin production; thus, no taxonomic identification of the isolates was done at the molecular level. Despite that InDels within the ABC in Aspergillus flavus are in some instances associated with loss of aflatoxin production [35], all Ethiopian Aspergillus section Flavi isolates produced detectable levels of aflatoxins in vitro. InDels have been used to monitor non-aflatoxigenic Aspergillus spp. [36] and to characterize the genetic diversity of Aspergillus spp. to later sequence the genomes of the most frequent genotypes [11, 45]. In a similar approach, the genomes of 16 of the 145 Ethiopian Aspergillus isolates presented here have already been sequenced [46], as indicated in Fig. 1.

Group I through III also showed a gradient in chemotype, from producers of aflatoxin B in Group I, to producers of high levels of B and G aflatoxins in Group III, Fig. 3. Since all the isolates tested produced aflatoxins, no group of isolates corresponded to the aflatoxin non-producers (clade IB-type or GI) that had been described in the literature [11, 47], respectively.

Three InDels, AFLC19, AFLC08 and AFLC04, mainly accounted for the assignment of isolates to Groups I, II and III, respectively. In Group I, most of the isolates had a 3 bp insertion in the aflW (moxY) gene detected by marker AFLC19. This group consisted mostly of A. flavus NPS and few A. flavus L-morphotype isolates. The monoxygenase encoded by aflW [48] catalyzes the reactions HVN (hydroxyversicolorone) to VHA (versiconal hemiacetal acetate) and VONE (versicolorone) to VOAc (versiconol acetate), both oxidative steps required for aflatoxin biosynthesis [49]. In our study, the insertion found in the aflW gene of Group I isolates did not result in loss of aflatoxin production.

Isolates within Group II shared similar amplicons for InDel AFLC08, showing a 14 bp deletion in the anthrone-oxidase gene hypC, a gene in the intergenic region between aflC (pksA) and aflD (nor-1). The monooxygenase coded by hypC converts norsolorinic acid anthrone to norsolorinic acid, a precursor of aflatoxins [50]. The deletion in hypC resulted in the grouping of A. flavus NPS aflatoxin-B producers together with A. flavus S-morphotype that were low producers of aflatoxins B and G.

Group III comprised primarily A. parasiticus but also included a subclade of A. flavus S-morphotype capable of producing aflatoxin types B and G. Whereas production of type B and G aflatoxins is characteristic of A. parasiticus, it is also known that A. flavus S-morphotype can produce B and G aflatoxins [47]. Group III was distinguished from the rest by a 3 bp deletion in the pksA gene detected by marker AFLC04; this gene is required in the early steps of aflatoxin biosynthesis [51]. Search of the AFLC04 locus in NCBI showed that A. parasiticus CP051029.1, AY371490.1, L42765.1, Z47198.1, ML734987.1, JZEE01000728.1, LOAP01000469.1 did not have the mentioned 3 bp deletion. However, A. parasiticus isolates E1319, E1348, E1443 and E1337 [46] had a 3 bp deletion within the AFLC04 locus, being in E1337 slightly downstream. Despite that in some cases a single nucleotide polymorphism in the pksA gene has caused premature termination of protein synthesis and resulted in no aflatoxin production [52], in the Ethiopian isolates of Aspergillus, the 3 bp deletion did not completely impaired aflatoxin-producing capability.

The percentage of Aspergillus section Flavi isolated from groundnuts and able to produce aflatoxins can vary, for example in Vietnam 38% of the isolates were aflatoxigenic [31] whereas in the USA 96% of the isolates produced aflatoxins [11], in the present study, 100% of Aspergillus isolates produced detectable levels of aflatoxins in vitro. Various authors have described the prevalence of aflatoxin contamination in groundnut in Ethiopia [3, 4, 23]; however, no referable data are available on the aflatoxin producing potential of individual isolates. Using the same methods for isolation and UPLC aflatoxin analysis applied in the present work, we had found that 3.3% of the Aspergillus isolates from groundnut did not produce aflatoxins [11], thus we expected to find at least two aflatoxin-non producers among the isolates. No isolate has been identified in the present work as a non-producer of aflatoxins and with potential use in biocontrol.

In the present work, some association was observed between Aspergillus genotypes and their geographic origin; for example, most of the isolates from Babile were A. flavus producers of type B aflatoxins; whereas those from Gursum and Darolabu were mostly A. parasiticus and A. flavus S-morphotype, both producers of B and G aflatoxins. While Babile is a lowland area with 1590 m average altitude and < 900 mm mean annual rainfall, the areas of Darolabu and Gursum are highland areas at 1720 m altitude and > 1000 mm rainfall [5]. If we consider a dry adiabatic lapse rate of − 1 °C every 100 m-increase in altitude [53], the areas of Gursum and Darolabu would be an average of 1.3 °C cooler than Babile. Studies over a range of water activities have shown that A. parasiticus grows better at marginally cooler temperatures, approximately 3 °C lower [54], than A. flavus [55]. Since environmental factors such as drought and elevated soil temperatures are important factors determining the severity of groundnut kernel colonization by Aspergillus species [56, 57], then, it is possible that the slightly higher altitude in Darolabu and Gursum may have favored groundnut colonization by A. parasiticus. Alternatively, groundnut plants grown at higher altitude possibly provide better conditions for the colonization by A. parasiticus. Further work will be necessary to determine whether this is an actual trend.

Conclusions

This is the first study of the genetic diversity of Aspergillus flavus and A. parasiticus isolates that colonize groundnut kernels in the main crop areas of Ethiopia, work performed using InDel loci within the ABC. Three groups were found, and these were mainly discriminated by InDels on three loci, aflW (moxY), aflC (pksA) and hypC. Despite the genetic polymorphism observed within the ABC, all isolates tested produced aflatoxins. Determining the most abundant species and genotypes colonizing groundnut in a particular area can provide basic information to develop new technologies for the control of aflatoxins.

Methods

Origin of Aspergillus isolates

During the 2014/2015 growing season, 20 cultivated groundnut samples from each of four Ethiopian districts (Babile, Darolabu, Fedis, and Gursum) were obtained in addition to 60 cultivated groundnut samples harvested from a field experiment (labelled: Field) from the Babile district in accordance to local legislation. Peanut samples were exported from Ethiopia under Phytosanitary Certificate: No. 339283, issued by the Ministry of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Regulatory Directorate, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, on 07-31-2014; and brought to the United States under Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS), Plant Protection and Quarantine (PPQ) permit Number P526–13-03711, the kernels were received at the National Peanut Research Laboratory for fungal isolation. From the groundnut samples 145 Aspergillus spp. of section Flavi were isolated, the methods of isolation and identification of the isolates have already been published [22].

Genetic diversity of Aspergillus species

DNA was extracted from spores and/or sclerotia of Aspergillus isolates that had been grown for 5–10 days on Petri plates containing Modified Dichloran Rose Bengal (MDRB) medium [58]. The spores and/or sclerotia were harvested using sterile plastic loops (Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) and placed in 2 mL screw-cap tubes (Omni International, Kennesaw, GA) that contained 2 metal (2.4 mm ∅) and 2 zirconium (2.8 mm ∅) beads. Grinding was performed with an Omni Bead Ruptor (Omni International) at 5 m/s for 40 s. DNA was extracted using the DNeasy Plant Mini Kit in a QIAcube robot (both from Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to manufacturer’s instructions for plant DNA extraction, and then quantified using Nanodrop 2000c spectrophotometer (Nanodrop Technologies Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA).

PCR amplification, fingerprinting and phylogenetic structures of Aspergillus isolates

DNA fingerprinting was done for 145 Aspergillus isolates using 23 InDel markers (Table 1) to analyze their genetic diversity, as previously described [11]. Forward InDel primers were 5′-tailed with the sequence 5′-CAGTTTTCCCAGTCACGAC-3′ to permit product labeling, and reverse primers were tailed at the 5′ end with the sequence 5′-GTTT-3′ to promote non-template adenylation [59]. Primer 5′-CAGTTTTCCCAGTCACGAC-3′ labeled with 6-carboxy-fluorescein (FAM) (IDT, Coralville, IA) was used for labelling the amplification of 10 ng DNA using Titanium Taq DNA Polymerase (Clontech, Mountain View, CA) in 5 μL reactions on an M & J thermal cycler (BioRad, Hercules, CA) at 95 °C for 60 s, 60 °C for 60 s (2 cycles), 95 °C for 30 s, 60 °C for 30 s, 68 °C for 30 s (27 cycles) and a final extension at 68 °C for 4 min. Fluorescently-labelled PCR fragments were analyzed on an ABI 3730XL DNA analyzer, and data were processed using GeneMapper 4.0 (both from Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA).

Amplicons within the range of the fluorescent ladder reference, 100 and 500 bp in length, were used in the analysis. Presence or absence of amplicons was converted to a binary matrix and used to calculate genetic distances among isolates. Cluster analysis of InDels was performed by NJ [60] using NTSYSpc2.2 (Applied Biostatistics Inc.) [61]. The same data were used in 3D-Principal Coordinate Analysis (3D-PCoA) [62] and run with Jaccard’s distances in NTSYSpc2.2 [61]. Analysis of the population structure was performed with Structure 2.1 [63]. Since only two species of Aspergillus were observed among the isolates, though up to four groups could be expected given that S-morphotype and L-morphotype were present. L-morphotype corresponds to isolates that have the morphology of a typical A. flavus but have apparently lost their capability to produce sclerotia, and have been normally reported separately in the literature [12, 15]. We use a maximum K = 5 in case that some other species was present. The use of a K value higher than the four predicted could help detect a potentially cryptic genetic structure in the database generated by fingerprinting. The admixture model was used with correlated allele frequencies, 200,000 as a period of burn-in, and 500,000 iterations after burn-in to allow the Markov chain to reach stationarity. Ten independent simulations were run for each value of K, ranging from K = 1 to K = 5, checking for consistency across outputs. To obtain the appropriate K from the data according to Evanno et al. [64], we used the Structure Harvester program [65].

In vitro aflatoxin production of Aspergillus isolates

A total of 84 Aspergillus isolates were screened for aflatoxin production. The other 61 isolates labelled as “Field”, originated from a 270 m2 area that had already been sampled and labelled as “Babile”, so no additional phenotypes were expected regarding aflatoxin production of “Field” isolates. The fungi were grown on yeast extract sucrose (YES) liquid medium, consisting of 150 g/L sucrose, 20 g/L yeast extract and 10 g/L soytone [66]. Four mL vials containing 2 mL of YES medium were inoculated with spores of A. flavus including L- and S-morphotype, and A. parasiticus using a sterilized needle. Inoculated vials with loose caps were incubated at 30 °C for 5 days. For extraction of aflatoxins, 1 mL of chloroform was added to each vial and vortexed for 10 s, then the vials were placed in the dark at room temperature for 24 h. After that, 300 μL of the chloroform layer were transferred to 4 mL vials and placed in a heated block at 45 °C. The solvent was removed by a stream of N2. The dry residue was re-dissolved in 500 μL methanol-water mixture (8:2, v/v), vortexed for 3 s, followed by application of 500 μL of acetonitrile and vortexed for an extra 3 s, then 500 μL of the mixture were applied to an Alltech 1.5 mL Extract-Clean minicolumn containing 200 mg basic aluminum oxide [67]. Aflatoxins were eluted by gravity and collected into a 700 μL UPLC vial (p/n: 186005221, Waters Co., Milford, MA). An aliquot of purified extract (1 μL) was injected into the UPLC system. Aflatoxin detection and quantification was performed using an Acquity UPLC instrument equipped with a Quaternary Solvent manager, a Sample Manager-FTN, a fluorescent detector-FLR, and an Acquity UPLC BEH C18 1.7 μm 2.1 × 50 mm analytical column (Waters Co., Milford, MA). The column temperature was 40 °C. The mobile phase was composed of water-methanol-acetonitrile mixture (70:20:10, v/v/v, respectively) and the flow rate was 0.25 mL/min. Analysis and data processing were performed with Waters Empower3 Chromatography Data Software (Waters Co., Milford, MA). Concentrations of aflatoxins were calculated as μg/mL by reference to the calibration curves obtained by injecting different amounts of corresponding commercial standards (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). The quantification limits of aflatoxins B1 and G1 were 0.100 μg/mL, and 0.015 μg/mL for aflatoxin B2 and G2, respectively. Working solutions of aflatoxins were prepared according to the protocol published by Sobolev and Dorner [67].

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Supplementary Table 1.Aspergillus isolates used for genetic diversity (N = 145) from Ethiopia of which, 84 isolates were screened for aflatoxin B1, B2, G1 and G2 production using UPLC protocol (μg/mL). nd = not detected; nt = not tested.

Acknowledgements

not applicable

Abbreviations

- InDel

Insertion/deletion

- UPLC

Ultra-performance liquid chromatography

- 3D-PCoA

3-Dimentional Principal Coordinate Analysis

- NJ

Neighbor Joining

- NPS

Non-producers of sclerotia

- L-strain

Aspergillus flavus that produce large, > 400 μm diam sclerotia

- S-strain

Aspergillus flavus that produce small, < 400 μm diam sclerotia

- bp

Base pairs

- ABC

Aflatoxin-biosynthesis gene cluster

Authors’ contributions

A.M., A.C., R.S.A.: conceptualization & Supervision; A.M., P.C.F., V.S.S., J.M.C., R.S.A.: data curation and formal analysis; D.A.H., M.D., C.F., A.A.: resources & funding acquisition; A.M. writing – original draft; AM, PCF, VSS, CO, AC, RSA: review & editing. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Funding

This study was made possible through support provided by the Office of Agriculture, Research and Policy, Bureau of Food Security, U.S. Agency for International Development, under the terms of award No. AID-ECG-A-00-07-0001 to the University of Georgia as a management entity for the U.S. Feed the Future Innovation Lab on Peanut Productivity and Mycotoxin Control. Additional support was provided by the United States Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, NP 301, Research Project 6604–21000-003-00D.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available in the Harvard Dataverse repository. The raw data of the genetic fingerprinting as output of ABI 3730 sequencer, have been deposited at Harvard Dataverse repository, with persistent web link: 10.7910/DVN/CXX0TG. Complete data set of aflatoxin determinations is provided in Additional File 1. Fungal isolates are stored at the National Peanut Research Laboratory collection, special APHIS permits are required to work with these fungi.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

All authors declare having no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.CSA. Central statistical agency, agricultural sample survey. Addis Ababa: Central Statistics Agency (CSA); 2019/2020.

- 2.Kebede A, Tana T. Genotype by environment interaction and stability of pod yield of elite breeding lines of groundnut (Arachis hypogaea L.) in eastern Ethiopia. Sci Technol Arts Res J. 2014;3(2):43–46. doi: 10.4314/star.v3i2.6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eshetu L. Aflatoxin content of peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.) in relation to shelling and storage practice of Ethiopian farmers. Addis Ababa: Addis Ababa University; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chala A, Mohammed A, Ayalew A, Skinnes H. Natural occurrence of aflatoxins in groundnut (Arachis hypogaea L.) from Eastern Ethiopia. Food Control. 2013;30(2):602–605. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2012.08.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mohammed A, Chala A. Incidence of Aspergillus contamination of groundnut (Arachis hypogaea L.) in Eastern Ethiopia. Afr J Microbiol Res. 2014;8(8):759–765. doi: 10.5897/AJMR12.2078. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bennett JW. An overview of the genus Aspergillus. In: Machida M, Gomi K, editors. Aspergillus: molecular biology and genomics. Norfolk: Caister Academic Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rodrigues P, Santos C, Venâncio A, Lima N. Species identification of Aspergillus section Flavi isolates from Portuguese almonds using phenotypic, including MALDI-TOF ICMS, and molecular approaches. J Appl Microbiol. 2011;111(4):877–892. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2011.05116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cotty PJ. Effect of atoxigenic strains of Aspergillus flavus on aflatoxin contamination of developing cottonseed. Plant Dis. 1990;74(3):233–235. doi: 10.1094/PD-74-0233. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dorner JW, Horn BW. Separate and combined applications of nontoxigenic Aspergillus flavus and A. parasiticus for biocontrol of aflatoxin in peanuts. Mycopathologia. 2007;163(4):215–223. doi: 10.1007/s11046-007-9004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abbas H, Zablotowicz RM, Horn BW, Phillips NA, Johnson BJ, Jin X, et al. Comparison of major biocontrol strains of non-aflatoxigenic Aspergillus flavus for the reduction of aflatoxins and cyclopiazonic acid in maize. Food Addit Contam Part A Chem Anal Control Expo Risk Assess. 2011;28(2):198–208. doi: 10.1080/19440049.2010.544680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Faustinelli PC, Palencia ER, Sobolev VS, Horn BW, Sheppard HT, Lamb MC, Wang XM, Scheffler BE, Martinez Castillo J, Arias RS. Study of the genetic diversity of the aflatoxin biosynthesis cluster in Aspergillus section Flavi using insertion/deletion markers in peanut seeds from Georgia, USA. Mycologia. 2017;109(2):200–209. doi: 10.1080/00275514.2017.1307095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Horn BW. Ecology and population biology of aflatoxigenic fungi in soil. J Toxicol Toxin Rev. 2003;22(2–3):351–379. doi: 10.1081/TXR-120024098. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cotty PJ. Virulence and cultural-characteristics of 2 Aspergillus flavus strains pathogenic on cotton. Phytopathology. 1989;79(7):808–814. doi: 10.1094/Phyto-79-808. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Novas MV, Cabral D. Association of mycotoxin and sclerotia production with compatibility groups in Aspergillus flavus from peanut in Argentina. Plant Dis. 2002;86(3):215–219. doi: 10.1094/PDIS.2002.86.3.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alaniz Zanon MS, Barros GG, Chulze SN. Non-aflatoxigenic Aspergillus flavus as potential biocontrol agents to reduce aflatoxin contamination in peanuts harvested in Northern Argentina. Int J Food Microbiol. 2016;231:63–68. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2016.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yiannikouris A, Jouany J-P. Mycotoxins in feeds and their fate in animals: a review. Anim Res. 2002;51(2):81–99. doi: 10.1051/animres:2002012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hussein HS, Brasel JM. Toxicity, metabolism, and impact of mycotoxins on humans and animals. Toxicology. 2001;167(2):101–134. doi: 10.1016/S0300-483X(01)00471-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.AACR. American Association for Cancer Research An evaluation of chemicals and industrial processes associated with cancer in humans based on human and animal data: IARC monographs volumes 1 to 20. Cancer Res. 1980;40(1):1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hsieh DP, Cullen JM, Hsieh LS, Shao Y, Ruebner BH. Cancer risks posed by aflatoxin M1. Princess Takamatsu Symp. 1985;16:57–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Uka V, Moore GG, Arroyo-Manzanares N, Nebija D, De Saeger S, Diana Di Mavungu J. Secondary metabolite dereplication and phylogenetic analysis identify various emerging mycotoxins and reveal the high intra-species diversity in Aspergillus flavus. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:667. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gnonlonfin GJ, Hell K, Adjovi Y, Fandohan P, Koudande DO, Mensah GA, Sanni A, Brimer L. A review on aflatoxin contamination and its implications in the developing world: a sub-Saharan African perspective. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2013;53(4):349–365. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2010.535718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Misihairabgwi JM, Ezekiel CN, Sulyok M, Shephard GS, Krska R. Mycotoxin contamination of foods in Southern Africa: a 10-year review (2007–2016) Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2019;59(1):43–58. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2017.1357003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mohammed A, Chala A, Dejene M, Fininsa C, Hoisington DA, Sobolev VS, Arias RS. Aspergillus and aflatoxin in groundnut (Arachis hypogaea L.) and groundnut cake in Eastern Ethiopia. Food Addit Contam Part B Surveill. 2016;9(4):290–298. doi: 10.1080/19393210.2016.1216468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kew MC. Aflatoxins as a cause of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2013;22(3):305–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khlangwiset P, Shephard GS, Wu F. Aflatoxins and growth impairment: a review. Crit Rev Toxicol. 2011;41(9):740–755. doi: 10.3109/10408444.2011.575766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Azziz-Baumgartner E, Lindblade K, Gieseker K, Rogers HS, Kieszak S, Njapau H, Schleicher R, McCoy LF, Misore A, DeCock K, Rubin C, Slutsker L, the Aflatoxin Investigative Group Case-control study of an acute aflatoxicosis outbreak, Kenya, 2004. Environ Health Perspect. 2005;113(12):1779–1783. doi: 10.1289/ehp.8384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khlangwiset P, Wu F. Costs and efficacy of public health interventions to reduce aflatoxin-induced human disease. Food Addit Contam Part A Chem Anal Control Expo Risk Assess. 2010;27(7):998–1014. doi: 10.1080/19440041003677475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ismail A, Gonçalves BL, de Neeff DV, Ponzilacqua B, Coppa CFSC, Hintzsche H, Sajid M, Cruz AG, Corassin CH, Oliveira CAF. Aflatoxin in foodstuffs: occurrence and recent advances in decontamination. Food Re Int. 2018;113:74–85. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2018.06.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dorner JW. Development of biocontrol technology to manage aflatoxin contamination in peanuts. Peanut Sci. 2009;36(1):60–67. doi: 10.3146/AT07-002.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cotty PJ, Cardwell KF. Divergence of West African and North American communities of Aspergillus section Flavi. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65(5):2264–2266. doi: 10.1128/AEM.65.5.2264-2266.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tran-Dinh N, Kennedy I, Bui T, Carter D. Survey of Vietnamese peanuts, corn and soil for the presence of Aspergillus flavus and Aspergillus parasiticus. Mycopathologia. 2009;168(5):257–268. doi: 10.1007/s11046-009-9221-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cotty PJ, Mellon JE. Ecology of aflatoxin producing fungi and biocontrol of aflatoxin contamination. Mycotoxin Res. 2006;22(2):110–117. doi: 10.1007/BF02956774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yu J, Chang P-K, Ehrlich KC, Cary JW, Bhatnagar D, Cleveland TE, Payne GA, Linz JE, Woloshuk CP, Bennett JW. Clustered pathway genes in aflatoxin biosynthesis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004;70(3):1253–1262. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.3.1253-1262.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Drott MT, Satterlee TR, Skerker JM, Pfannenstiel BT, Glass NL, Keller NP, et al. The frequency of sex: population genomics reveals differences in recombination and population structure of the aflatoxin-producing fungus Aspergillus flavus. mBio. 2020;11(4):e00963–e00920. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00963-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chang PK, Horn BW, Dorner JW. Sequence breakpoints in the aflatoxin biosynthesis gene cluster and flanking regions in nonaflatoxigenic Aspergillus flavus isolates. Fungal Genet Biol. 2005;42(11):914–923. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2005.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Callicott KA, Cotty PJ. Method for monitoring deletions in the aflatoxin biosynthesis gene cluster of Aspergillus flavus with multiplex PCR. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2015;60(1):60–65. doi: 10.1111/lam.12337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nei M. Genetic distance between populations. Am Nat. 1972;106(949):283–292. doi: 10.1086/282771. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pildain MB, Vaamonde G, Cabral D. Analysis of population structure of Aspergillus flavus from peanut based on vegetative compatibility, geographic origin, mycotoxin and sclerotia production. Int J Food Microbiol. 2004;93(1):31–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2003.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barros GG, Torres AM, Rodriguez MI, Chulze SN. Genetic diversity within Aspergillus flavus strains isolated from peanut-cropped soils in Argentina. Soil Biol Biochem. 2006;38(1):145–152. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2005.04.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reeves PA, Richards CM. Accurate inference of subtle population structure (and other genetic discontinuities) using principal coordinates. PLoS One. 2009;4(1):27. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Egel D, Cotty P, Elias KS. Relationships among isolates of Aspergillus sect. Flavi that vary in aflatoxin production. Phytopathology. 1994;84(9):906–912. doi: 10.1094/Phyto-84-906. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Singh P, Orbach MJ, Cotty PJ. Aspergillus texensis: a novel aflatoxin producer with S morphology from the United States. Toxins. 2018;10(12) Epub 2018/12/06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Frisvad JC, Hubka V, Ezekiel CN, Hong SB, Novakova A, Chen AJ, et al. Taxonomy of Aspergillus section Flavi and their production of aflatoxins, ochratoxins and other mycotoxins. Stud Mycol. 2019;93:1–63. doi: 10.1016/j.simyco.2018.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ohkura M, Cotty PJ, Orbach MJ. Comparative genomics of Aspergillus flavus S and L morphotypes yield insights into niche adaptation. G3-Genes Genom Genet. 2018;8(12):3915–3930. doi: 10.1534/g3.118.200553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Faustinelli PC, Wang XM, Palencia ER, Arias RS. Genome sequences of eight Aspergillus flavus spp. and one A. parasiticus sp., isolated from peanut seeds in Georgia. Genome Announc. 2016;4(2) Epub 2016/04/16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Arias RS, Mohammed A, Orner VA, Faustinelli PC, Lamb MC, Sobolev VS. Sixteen draft genome sequences representing the genetic diversity of Aspergillus flavus and Aspergillus parasiticus colonizing peanut seeds in Ethiopia. Microbiol Resour Announc. 2020;9(30) Epub 2020/07/25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Geiser DM, Dorner JW, Horn BW, Taylor JW. The phylogenetics of mycotoxin and sclerotium production in Aspergillus flavus and Aspergillus oryzae. Fungal Genet Biol. 2000;31(3):169–179. doi: 10.1006/fgbi.2000.1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yu J, Chang PK, Bhatnagar D, Cleveland TE. Genes encoding cytochrome P450 and monooxygenase enzymes define one end of the aflatoxin pathway gene cluster in Aspergillus parasiticus. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2000;53(5):583–590. doi: 10.1007/s002530051660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wen Y, Hatabayashi H, Arai H, Kitamoto HK, Yabe K. Function of the cypX and moxY genes in aflatoxin biosynthesis in Aspergillus parasiticus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71(6):3192–3198. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.6.3192-3198.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ehrlich KC, Li P, Scharfenstein L, Chang P-K. HypC, the anthrone oxidase involved in aflatoxin biosynthesis. App Environmental Microb. 2010;76(10):3374–3377. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02495-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chang P-K, Cary JW, Yu J, Bhatnagar D, Cleveland TE. The Aspergillus parasiticus polyketide synthase gene pksA, a homolog of Aspergillus nidulans wA, is required for aflatoxin B1 biosynthesis. Mol Gen Genet MGG. 1995;248(3):270–277. doi: 10.1007/BF02191593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ehrlich KC, Cotty PJ. An isolate of Aspergillus flavus used to reduce aflatoxin contamination in cottonseed has a defective polyketide synthase gene. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2004;65(4):473–478. doi: 10.1007/s00253-004-1670-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Brunt D. The adiabatic lapse-rate for dry and saturated air. Q J Roy Meteor Soc. 1933;59(252):351–360. doi: 10.1002/qj.49705925204. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Garcia D, Ramos AJ, Sanchis V, Marín S. Modelling the effect of temperature and water activity in the growth boundaries of Aspergillus ochraceus and Aspergillus parasiticus. Food Microbiol. 2011;28(3):406–417. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2010.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mousa W, Ghazali FM, Jinap S, Ghazali HM, Radu S. Modelling the effect of water activity and temperature on growth rate and aflatoxin production by two isolates of Aspergillus flavus on paddy. J Appl Microbiol. 2011;111(5):1262–1274. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2011.05134.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sanders TH, Blankenship PD, Cole RJ, Hill RA. Effect of soil-temperature and drought on peanut pod and stem temperatures relative to Aspergillus flavus invasion and aflatoxin contamination. Mycopathologia. 1984;86(1):51–54. doi: 10.1007/BF00437229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Craufurd PQ, Prasad PVV, Waliyar F, Taheri A. Drought, pod yield, pre-harvest Aspergillus infection and aflatoxin contamination on peanut in Niger. Field Crop Res. 2006;98(1):20–29. doi: 10.1016/j.fcr.2005.12.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Horn BW, Dorner JW. Regional differences in production of aflatoxin B1 and cyclopiazonic acid by soil isolates of Aspergillus flavus along a transect within the United States. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65(4):1444–1449. doi: 10.1128/AEM.65.4.1444-1449.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Brownstein MJ, Carpten JD, Smith JR. Modulation of non-templated nucleotide addition by Taq DNA polymerase: primer modifications that facilitate genotyping. Biotechniques. 1996;20(6):1004–1008. doi: 10.2144/96206st01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Saitou N, Nei M. The neighbor-joining method - a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol. 1987;4(4):406–425. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rohlf FJ. NTSYSpc: numerical taxonomy system, ver 2.2. Setauket: Exeter Publishing, Ltd.; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gower JC. Some distance properties of latent root and vector methods used in multivariate analysis. Biometrika. 1966;53(3/4):325–338. doi: 10.1093/biomet/53.3-4.325. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pritchard JK, Stephens M, Donnelly P. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics. 2000;155(2):945–959. doi: 10.1093/genetics/155.2.945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Evanno G, Regnaut S, Goudet J. Detecting the number of clusters of individuals using the software STRUCTURE: a simulation study. Mol Ecol. 2005;14(8):2611–2620. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2005.02553.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Earl DA. vonHoldt BM. STRUCTURE HARVESTER: a website and program for visualizing STRUCTURE output and implementing the Evanno method. Conserv Genet Resour. 2012;4(2):359–361. doi: 10.1007/s12686-011-9548-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Horn BW, Dorner JW. Soil populations of Aspergillus species from section Flavi along a transect through peanut-growing regions of the United States. Mycologia. 1998;90(5):767–776. doi: 10.1080/00275514.1998.12026969. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sobolev VS, Dorner JW. Cleanup procedure for determination of aflatoxins in major agricultural commodities by liquid chromatography. J Assoc Off Anal Chem. 2002;85(3):642–645. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Supplementary Table 1.Aspergillus isolates used for genetic diversity (N = 145) from Ethiopia of which, 84 isolates were screened for aflatoxin B1, B2, G1 and G2 production using UPLC protocol (μg/mL). nd = not detected; nt = not tested.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available in the Harvard Dataverse repository. The raw data of the genetic fingerprinting as output of ABI 3730 sequencer, have been deposited at Harvard Dataverse repository, with persistent web link: 10.7910/DVN/CXX0TG. Complete data set of aflatoxin determinations is provided in Additional File 1. Fungal isolates are stored at the National Peanut Research Laboratory collection, special APHIS permits are required to work with these fungi.