Abstract

PINCH is a widely expressed and evolutionarily conserved protein comprising primarily five LIM domains, which are cysteine-rich consensus sequences implicated in mediating protein-protein interactions. We report here that PINCH is a binding protein for integrin-linked kinase (ILK), an intracellular serine/threonine protein kinase that plays important roles in the cell adhesion, growth factor, and Wnt signaling pathways. The interaction between ILK and PINCH has been consistently observed under a variety of experimental conditions. They have interacted in yeast two-hybrid assays, in solution, and in solid-phase-based binding assays. Furthermore, ILK, but not vinculin or focal adhesion kinase, has been coisolated with PINCH from mammalian cells by immunoaffinity chromatography, indicating that PINCH and ILK associate with each other in vivo. The PINCH-ILK interaction is mediated by the N-terminal-most LIM domain (LIM1, residues 1 to 70) of PINCH and multiple ankyrin (ANK) repeats located within the N-terminal domain (residues 1 to 163) of ILK. Additionally, biochemical studies indicate that ILK, through the interaction with PINCH, is capable of forming a ternary complex with Nck-2, an SH2/SH3-containing adapter protein implicated in growth factor receptor kinase and small GTPase signaling pathways. Finally, we have found that PINCH is concentrated in peripheral ruffles of cells spreading on fibronectin and have detected clusters of PINCH that are colocalized with the α5β1 integrins. These results demonstrate a specific protein recognition mechanism utilizing a specific LIM domain and multiple ANK repeats and suggest that PINCH functions as an adapter protein connecting ILK and the integrins with components of growth factor receptor kinase and small GTPase signaling pathways.

Many of the essential cellular processes, including cell proliferation, differentiation, and survival, are controlled by signal transduction pathways involving specific protein-protein interactions. Frequently, the protein-protein interactions are mediated by adapter proteins, a group of noncatalytic proteins specialized in mediating multiprotein complex formation. Structurally, the adapter proteins are characterized by containing multiple protein binding motifs. The LIM domain is a protein binding motif consisting of a cysteine-rich consensus sequence of approximately 50 amino acids that fold into a specific three-dimensional structure comprising two zinc fingers (6, 11). LIM domains have been identified in a variety of nuclear and cytoplasmic proteins that are critically involved in embryonic development and many pathological processes, including cancer. While many LIM proteins contain various other functional domains such as homeodomains or kinase domains, a subfamily of LIM proteins that are composed of only LIM domains (LIM-only proteins) has also been described. Because the primary function of the LIM domains, and probably also the LIM-only proteins, is in mediating protein-protein interactions (6, 11, 23), identification of structural targets recognized by the LIM domains is fundamentally important in understanding specific functions of the LIM proteins. PINCH is a widely expressed LIM-only protein that was initially identified from screening of a human cDNA library with antibodies recognizing senescent erythrocytes (20). The structure of PINCH is particularly interesting, as it contains a tandem array of five LIM domains (the most among all known LIM-containing proteins). Recently, we have found that PINCH interacts with Nck-2, an SH2/SH3-containing adapter protein physically associated with key components of small GTPase- and growth factor receptor kinase signaling pathways, including IRS-1 and receptors for epidermal growth factor (EGF) and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) (26). The binding of PINCH to Nck-2 is mediated solely by the fourth LIM domain (26), leaving other PINCH LIM domains free to interact with other binding partners.

Integrin-linked kinase (ILK) is an intracellular serine/threonine protein kinase capable of interacting with the integrin β1 cytoplasmic domain (10). ILK regulates integrin-mediated cell adhesion (10), E-cadherin expression (17, 31), and pericellular fibronectin matrix assembly (31). Overexpression of ILK in epithelial cells has been shown to activate the LEF-1/β-catenin signaling pathway (17) and to induce anchorage-independent cell growth (10) and oncogenic transformation (31). Furthermore, ILK is intimately involved in cell adhesion-dependent cell cycle progression by regulation of the level or activity of several key components of cell cycle machinery, including cyclin A, cyclin D1, and Cdk 42 (19). Recently, Delcommenne et al. have demonstrated that the kinase activity of ILK can be regulated by cell adhesion to fibronectin and by insulin in a phosphoinositide-3-OH kinase-dependent manner (8). Moreover, ILK can directly phosphorylate protein kinase B (PKB)/AKT on serine-473, one of the two phosphorylation sites involved in the activation of PKB/AKT, and regulate glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK-3) activity (8). However, while it is clear that ILK plays important roles in regulation of the cell adhesion, growth factor, and Wnt signaling pathways, how ILK functions in the signaling pathways has not been completely understood, due in part to the incomplete understanding of the protein-protein interactions involving ILK.

ILK comprises three structurally, and likely also functionally, distinctive domains (8, 10). The C-terminal domain is highly homologous to the catalytic domains of a large number of protein kinases and is responsible for the kinase activity. In addition, it includes a binding site for the integrin β1 cytoplasmic domain (10). N terminal to the kinase domain is a PH-like domain that likely binds phosphatidylinositol(3,4,5)triphosphate and participates in regulation of the kinase activity (8). The N-terminal-most domain comprises primarily four ankyrin (ANK) repeats, which most likely define a structure mediating additional protein-protein interactions (2, 10, 14). However, proteins interacting with the ANK repeats containing the N-terminal domain of ILK had not been identified. To facilitate studies aimed at elucidating the molecular basis of the ILK signaling pathway, we have carried out a series of experiments to identify and characterize ILK interactive proteins. We report here that the LIM-only protein PINCH is an ILK binding protein, and we describe the molecular characterization of the PINCH-ILK interaction. Furthermore, we provide evidence indicating that PINCH functions as a bridge protein linking ILK to Nck-2. Finally, we show that PINCH is concentrated in peripheral ruffles and recruited to integrin-rich cell adhesion sites in cells spreading on fibronectin.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents.

All organic chemicals were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, Mo.) or Fisher Scientific Co. (Pittsburgh, Pa.) unless otherwise specified. Media for cell culture were from Gibco Laboratories (Grand Island, N.Y.) unless otherwise specified. Fetal bovine serum was from HyClone Laboratories, Inc. (Logan, Utah). Rat kidney mesangial cells were kindly provided by John Couchman and Anne Woods (University of Alabama at Birmingham). Human ILK cDNA and a polyclonal anti-human ILK antibody (91-5) were kindly provided by Shoukat Dedhar (Jack Bell Research Center, Vancouver, Canada). Mouse ILK cDNA was isolated as previously described (12). A rabbit polyclonal anti-glutathione S-transferase (GST)–ILK antibody (31T) was generated by using an affinity-purified GST-ILK fusion protein containing the full-length mouse ILK sequence. Rabbit polyclonal anti-α5 integrin antibody was generated as previously described (21). Rabbit polyclonal anti-focal adhesion kinase (FAK) antibody (A-17) was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. Mouse monoclonal antivinculin antibody (V9131) and polyclonal rabbit anti-GST antibody were from Sigma. Rabbit anti-MBP antiserum was from New England Biolabs. Restriction enzymes, DNA-modifying enzymes, DNA molecular weight markers, and dideoxyribonucleoside triphosphates were purchased from Promega. Synthetic oligonucleotides were prepared by Gibco BRL. CNBr-activated Sepharose 4B was purchased from Amersham Pharmacia Biotech (Piscataway, N.J.).

Yeast two-hybrid assays.

A cDNA fragment encoding the human ILK N-terminal region (amino acid residues 1 to 163) was amplified by PCR and inserted into the EcoRI/XhoI site in the pLexA vector (Clontech). The sequence of the bait construct (pLexA/ILK1) was verified by DNA sequencing, and the construct was introduced into EGY48[P8OP-lacZ] yeast cells (Clontech) by using a lithium acetate transformation protocol (9). The transformants were used to screen a human lung MATCHMAKER LexA cDNA library (>5.7 × 106 independent clones [Clontech]) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, EGY48[P8OP-lacZ; pLexA/ILK] cells transformed by the library plasmids were selected by plating on SD medium lacking histidine, uracil, and tryptophan (SD/−His/−Ura/−Trp). Expression of proteins encoded by the pB42AD library vectors was induced by growing the cells in the presence of galactose (SD/Gal/Raf/−His/−Ura/−Trp medium [Clontech]). Twenty-seven positive yeast colonies, as indicated by activation of both reporter genes (LEU2 and lacZ), were independently identified and isolated. Plasmids were isolated from positive yeast cells by a glass beads/phenol-chloroform extraction protocol provided by the manufacturer (Clontech). We transformed Escherichia coli KC8 cells with the plasmids and selected cells containing the pB42AD vectors by growing them in medium lacking tryptophan. The pB42AD plasmids were isolated from E. coli KC8 cells and restriction (EcoRI/XhoI) mapped, and the sequences of the inserts were determined by DNA sequencing.

In addition to library screening, we performed yeast two-hybrid binding assays to determine the interactions between specific protein sequences. Yeast cells were cotransformed with purified pLexA and pB42AD expression vectors encoding various PINCH and ILK sequences or control proteins (paxillin and zyxin LIM domains and integrin β1 cytoplasmic domain), as specified for each experiment. The transformants were selected as described above and plated on leucine-deficient selection medium containing 80 μg of X-Gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside) per ml (SD/Gal/Raf/−His/−Ura/−Trp/−Leu/X-Gal medium [Clontech]). The growth of blue colonies in the leucine-deficient medium indicated a positive interaction. Additionally, the β-galactosidase activity of the yeast transformants was quantified with o-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside as a substrate in a liquid culture assay (Clontech) (2a).

DNA sequencing.

Sequences of DNA fragments were determined manually with Sequenase, version 2.0 (United States Biochemicals).

PINCH and ILK deletion mutations.

DNA fragments encoding PINCH and ILK deletion mutants were generated by PCR, and the amino acid residues encoded are specified for each experiment. 5′ EcoRI and 3′ XhoI restriction sites were incorporated into the amplified products via PCR primers to facilitate the insertion of the PINCH DNA fragments into the pB42AD expression vector and the ILK DNA fragments into the pLexA expression vector. Correct reading frames and sequences of all constructs were verified by DNA sequencing.

Expression and isolation of MBP, GST, and His fusion proteins.

The DNA construct (pMAL-C2/PINCH) encoding MBP-PINCH was generated by inserting the full-length human PINCH cDNA into the BamHI/HindIII site of the pMAL-C2 vector (New England Biolabs). To generate MBP fusion protein containing LIM1, a cDNA encoding the LIM1 domain of PINCH (amino acid residues 1 to 70) was inserted into the EcoRI/BamHI site of the pMAL-C2 vector (pMAL-C2/LIM1). MBP and the recombinant MBP fusion proteins containing either full-length PINCH or the LIM1 domain of PINCH were expressed in E. coli DH5α and isolated by affinity chromatography with amylose-agarose following the manufacturer’s protocols (New England Biolabs). The generation of a GST fusion protein containing full-length mouse ILK was described previously (12). Briefly, a cDNA encoding the entire open reading frame of mouse ILK was amplified from clone M9 by PCR and inserted into the SmaI/XhoI site of a pGEX-5x-3 vector (Pharmacia). The recombinant vector pGEX-ILK and the pGEX-5x-3 vector, as a control, were then used to transform E. coli cells (DH5α). The expression of the GST-ILK fusion protein and GST were induced with IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside), and the GST-ILK fusion protein and GST were purified by glutathione-Sepharose 4B affinity chromatography (12). To produce His-tagged fusion proteins containing full-length ILK and various LIM domains of PINCH, cDNA sequences encoding full-length mouse ILK and various human PINCH LIM domains (as specified for each experiment) were amplified by PCR and inserted into the NdeI/BamHI site of a pET-15b vector (Novagen, Madison, Wis.). The recombinant vectors were then used to transform E. coli BL21(DE3) cells, and the recombinant proteins were purified with His-Bind Resin (Novagen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Coprecipitation assays.

IMR-90 human lung fibroblasts were cultured in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 2 mM glutamine in 100-mm cell culture plates. Cells were harvested with 0.02% (wt/vol) EDTA in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), washed with PBS, and lysed with lysis buffer (1% Triton X-100 in 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.5, containing 150 mM NaCl, 15% [vol/vol] glycerol, 2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride [PMSF], 10 μg of aprotinin per ml, 5 μg of pepstatin A per ml, and 10 μg of leupeptin per ml). The lysate was clarified by centrifugation at 20,800 × g for 10 min, and the protein concentration was determined with a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay (Pierce). The cell lysate was preincubated with amylose-agarose beads (50%; New England Biolabs) at 4°C for 1.5 h, followed by centrifugation at 20,800 × g for 5 min. The cell lysate was then incubated with equal amounts (as specified for each experiment) of MBP-PINCH, MBP-LIM1, or MBP as a control at 4°C overnight. The MBP and MBP fusion proteins were then precipitated with 50 μl of amylose-agarose beads. After five washes with lysis buffer, human ILK associated with MBP-PINCH was detected by immunoblotting with an affinity-purified rabbit polyclonal anti-human ILK antibody (91-5; 69 ng/ml), a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibody (27 ng/ml), and the SuperSignal chemiluminescent substrate (Pierce).

Solid-phase-based binding assays.

A solid-phase-based binding assay was used to detect direct interactions between PINCH and ILK. Polystyrene enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) plates (Corning) were coated with 10 μg of MBP-PINCH, MBP-LIM1, or MBP per ml, and the remaining protein binding sites were blocked with 10 mg of bovine serum albumin (BSA) in 100 mM NaHCO3 (pH 9.2). The wells were rinsed three times with 0.1% (vol/vol) Triton X-100 in TBS (20 mM Tris-HCl, 140 mM NaCl [pH 7.2]), followed by incubation with 1 μg of GST-ILK, or GST as a control, per ml in TBS containing 0.1% (vol/vol) Triton X-100 and 10 mg of BSA per ml at 37°C for 90 min. At the end of the incubation, the wells were rinsed four times with 0.1% (vol/vol) Triton X-100 in TBS. The wells were then incubated with a rabbit anti-GST antibody (1 μg/ml) (Sigma) at 37°C for 60 min, washed four times with 0.1% (vol/vol) Triton X-100 in TBS, and incubated with alkaline phosphate-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (60 ng/ml) (Jackson ImmunoResearch). After four rinses with 0.1% (vol/vol) Triton X-100 in TBS and two rinses with TBS, bound alkaline phosphate conjugate was detected colorimetrically with p-nitrophenyl phosphate at 405 nm with an ELISA microplate reader. The A405 of the blank control was determined by omitting the alkaline phosphate conjugate and ranged from 0.06 to 0.07. The specific binding was calculated by subtracting the blank control A405 from the total A405.

To test whether ILK could form a complex with Nck-2 through interactions mediated by PINCH, we immobilized His-tagged ILK to Reacti-Bind metal chelate-coated 96-well plates (Pierce) by adding 100 μl of 0.1 μM His-tagged ILK per well to the Reacti-Bind plates. The plates were incubated with shaking for 1 h at room temperature, followed by two washes with TBS (20 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl [pH 8.0]). The wells were then incubated with 100 μl of 0.1 μM MBP-PINCH, or 0.1 μM MBP as a control, per well for 1 h at room temperature. At the end of the incubation, the wells were washed four times with TBS containing 0.05% (vol/vol) Tween 20 and then incubated with 0.1 μM GST–Nck-2, or 0.1 μM GST as a control, for 1 h at room temperature. After four washes with TBS containing 0.05% (vol/vol) Tween 20, the GST–Nck-2 (or GST) proteins bound were detected with a rabbit anti-GST antibody (1 μg/ml) (Sigma), as described above.

Generation of polyclonal and monoclonal anti-PINCH antibodies.

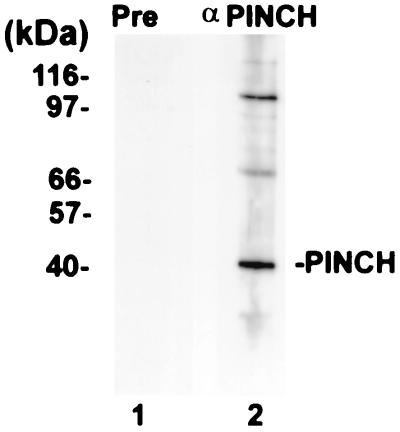

Rabbit polyclonal anti-PINCH antibodies were produced by immunizing New Zealand White rabbits with an MBP-PINCH fusion protein as the antigen by a standard protocol. The rabbit anti-PINCH antiserum, but not the preimmune rabbit serum, strongly reacted with the MBP-PINCH fusion protein in immunoblotting and ELISAs (data not shown). The rabbit anti-PINCH antiserum recognized a prominent protein band with an apparent molecular mass (approximate 40 kDa) that is similar to the predicted molecular mass of native PINCH in immunoblotting analyses of mammalian cell lysates (Fig. 1, lane 2). Additionally, two protein bands with higher molecular masses were also recognized by the rabbit anti-PINCH antiserum (Fig. 1, lane 2). In control experiments, no protein band was recognized by the preimmune rabbit serum (Fig. 1, lane 1). The polyclonal anti-PINCH IgG fraction was prepared by affinity chromatography with an immobilized protein G column (UltraLink; Pierce).

FIG. 1.

Immunoblot analysis of polyclonal anti-PINCH antibodies. CHO cellular proteins (10 μg of protein/lane) were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate–8% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (reduced) and analyzed by immunoblotting with a rabbit anti-MBP-PINCH antiserum (1:3,000 dilution, lane 2) or preimmune rabbit serum (1:3,000 dilution, lane 1) as a negative control.

Mouse monoclonal anti-PINCH antibodies were prepared with MBP-PINCH fusion protein as an antigen based on a previously described procedure (26). Hybridoma supernatants were screened for anti-PINCH antibody activity by ELISA and immunoblotting with affinity-purified MBP-PINCH and MBP, respectively. Monoclonal antibodies that recognize MBP-PINCH but not MBP were selected and were further tested by immunoblotting with His-PINCH proteins. One monoclonal antibody (clone 25.9, IgM) that specifically recognizes both the recombinant and native PINCH proteins was selected.

Association between native ILK and PINCH proteins.

Affinity-purified rabbit polyclonal anti-PINCH IgG was covalently coupled to CNBr-activated Sepharose 4B beads based on the protocol of the manufacturer (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). Briefly, 2 ml of CNBr-activated Sepharose 4B beads was incubated with 1 mg of anti-PINCH IgG that was dissolved in 5 ml of coupling buffer (0.1 M NaHCO3 buffer, pH 8.4, containing 0.5 M NaCl) at 4°C for 16 h. Control rabbit IgG-Sepharose 4B beads were prepared by incubating 2 ml of CNBr-activated Sepharose 4B beads with 1 mg of irrelevant rabbit IgG dissolved in 5 ml of 0.1 M NaHCO3 buffer under identical conditions. At the end of the incubation, the beads were packed into chromatographic columns and washed with coupling buffer. The beads were then incubated with 0.1 M Tris-HCl, pH 8, at room temperature for 2 h and pelleted, and the supernatants were collected. The protein concentrations of the collected supernatant solutions, which represented those of the uncoupled IgG, were determined with a BCA protein assay (Pierce). The coupling efficiency was calculated as (total amount of IgG − amount of uncoupled IgG)/total amount of IgG × 100% and found to be approximately 95% for both anti-PINCH IgG and the control rabbit IgG. The beads were washed for three cycles with 0.1 M acetate buffer containing 0.5 M NaCl (pH 4) and 0.1 M Tris-HCl containing 0.5 M NaCl (pH 8), respectively, followed by a wash with 100 mM glycine-HCl, pH 2.5, and PBS. The columns were equilibrated with 0.5% Triton X-100 in 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.5, containing 150 mM NaCl, 15% (vol/vol) glycerol, 2 mM PMSF, 10 μg of aprotinin per ml, 5 μg of pepstatin A per ml, and 10 μg of leupeptin per ml before loading of the cellular proteins.

CHO K1 cells were cultured in α-MEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 2 mM glutamine, harvested with 0.05% trypsin–0.53 mM EDTA (Mediatech/Cellgro, Herndon, Va.), and washed once with the α-MEM containing 10% FBS. The cells were then immediately lysed with lysis buffer (1% Triton X-100 in 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.5, containing 150 mM NaCl, 15% [vol/vol] glycerol, 2 mM PMSF, 10 μg of aprotinin per ml, 5 μg of pepstatin A per ml, and 10 μg of leupeptin per ml). The lysates were clarified by centrifugation at 20,800 × g for 10 min and filtered through 0.45-μm filters, and the protein concentration was determined with a BCA protein assay (Pierce). The cell lysates (6 ml of 0.42 mg of protein/ml) were loaded onto a column containing 2 ml of anti-PINCH IgG–Sepharose 4B beads at a flow rate of 0.15 ml/min. In control experiments, an equal amount of cell lysate was loaded onto a column containing 2 ml of irrelevant rabbit IgG-Sepharose 4B beads under identical conditions. The columns were then washed with 55 ml of 0.5% Triton X-100 in 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.5, containing 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM PMSF, 10 μg of aprotinin per ml, 5 μg of pepstatin A per ml, and 10 μg of leupeptin per ml and 55 ml of 0.5% Triton X-100 in 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.5, containing 700 mM NaCl, followed by elution with 100 mM glycine-HCl, pH 2.5. The eluates (15 fractions at 0.4 ml/fraction) were collected and further analyzed. The binding of PINCH protein to anti-PINCH IgG–Sepharose 4B beads, but not to the control rabbit IgG-Sepharose 4B beads, was confirmed by immunoblotting analyses of the elution fractions with anti-PINCH antibodies. The PINCH-associated protein (ILK) was detected by immunoblotting analysis of the fractions with antibodies recognizing ILK. In additional immunoblotting experiments, the elution fractions were also analyzed with antibodies against other cellular proteins (e.g., vinculin and FAK), as specified for each experiment.

Immunofluorescence staining of cells.

Rat kidney mesangial cells were cultured as a monolayer in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% FBS, 2 mM l-glutamine, and 1 mM sodium pyruvate (Mediatech/Cellgro) and harvested with 0.05% trypsin–0.53 mM EDTA (Mediatech/Cellgro). The cells were plated in Labtek eight-chamber culture slides (Nunc, Inc.) that were precoated with 20 μg of bovine plasma fibronectin per ml and incubated for different lengths of time (as specified for each experiment) in a 37°C incubator under a 5% CO2–95% air atmosphere to obtain cells that were in different stages of spreading. Within the first hour of plating, extensive membrane ruffling was observed in many of the mesangial cells that were spreading on fibronectin. Most of the cells were fully spread on fibronectin within 4 h (the spreading rate varied between different cells, and some cells were fully spread at a much earlier time). The cells were fixed with 3.7% paraformaldehyde in PBS, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS, and stained with mouse monoclonal anti-PINCH antibody 25.9 (mouse IgM; 5 μg/ml) and rabbit polyclonal anti-α5 integrin antibodies (rabbit IgG fraction; 100 μg/ml). After rinsing, the bound mouse IgM and rabbit IgG were detected with a Rhodamine Red-X-conjugated AffiniPure goat anti-mouse IgM antibody (μ chain specific) (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc.) (15 μg/ml) and a fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated AffiniPure goat anti-rabbit IgG antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc.) (60 μg/ml). Stained cells were observed under a fluorescence microscope equipped with rhodamine and FITC filters. In control experiments, no cross-reactivity between the monoclonal anti-PINCH antibody 25.9 and the FITC-conjugated AffiniPure goat anti-rabbit IgG antibody or between rabbit polyclonal anti-α5 integrin antibodies and the Rhodamine Red-X-conjugated AffiniPure goat anti-mouse IgM antibody was observed (data not shown).

RESULTS

Identification of PINCH as an ILK interactive protein by yeast two-hybrid screening.

We used a yeast two-hybrid system (pLexA system) to identify proteins that interact with the ANK repeat-containing N-terminal domain of ILK. A bait construct (pLexA/ILK1) encoding the N-terminal domain of ILK (amino acid residues 1 to 163) was used to screen a human lung MATCHMAKER LexA cDNA library (>5.7 × 106 independent clones [Clontech]). Twenty-seven strong positive clones were obtained. DNA sequencing showed that plasmids from 26 (16 with an insert of 1.6 kb, 6 with an insert of 1.5 kb, 3 with an insert of 1.3 kb, and 1 with an insert of 1.1 kb) of the 27 positive clones contained a common sequence encoding the LIM-only protein PINCH. The high percentage (96%) of positive clones that encode PINCH suggests that, at least in the lung cells, PINCH is a major ILK interactive protein. The interaction between the N-terminal domain of ILK and PINCH was confirmed by a yeast two-hybrid binding assay using a purified pB42AD expression vector encoding PINCH (Table 1). No interactions between the N-terminal domain of ILK and the LIM domains of paxillin and zyxin were detected, indicating that the ILK binding activity is a specific property of the PINCH LIM domains. In additional control experiments, elimination of either the bait plasmid or the library plasmid containing the PINCH sequence from the yeast host cells resulted in inactivation of both reporter genes, indicating that neither the N-terminal domain of ILK nor PINCH can activate the reporter genes in the absence of the other binding partner. In addition, replacement of the N-terminal domain of ILK with an irrelevant protein, lamin C, abolished the interaction (Table 1), further confirming the specificity of the interaction. In additional yeast two-hybrid binding experiments, we found that PINCH did not directly recognize the β1 integrin cytoplasmic domain (Table 1), to which the C-terminal domain of ILK binds (10).

TABLE 1.

Interaction of PINCH with ILK in yeast two-hybrid binding assaysa

| pLexA construct | pB42AD construct | Reporter gene

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| LEU2 | lacZ | ||

| pLexA-ILK1 | pB42AD-PINCH | + | + |

| pLexA-ILK1 | − | − | |

| pLexA-ILK1 | pB42AD-paxillin (LIM1-4) | − | − |

| pLexA-ILK1 | pB42AD-zyxin (LIM1-3) | − | − |

| pB42AD-PINCH | − | − | |

| pLexA | pB42AD-PINCH | − | − |

| pLexA-Lam C | pB42AD-PINCH | − | − |

| pLexA-β1 integrin cyto | pB42AD-PINCH | − | − |

The yeast two-hybrid assay was performed as described in Materials and Methods. The interactions between the proteins encoded by the pLexA and pB42AD constructs were determined by the activation of the reporter genes. ILK1, ILK N-terminal domain (residues 1 to 163); paxillin (LIM1-4), human paxillin sequence containing all four LIM domains (residues 322 to 557); zyxin (LIM1-3), human zyxin sequence containing all three LIM domains (residues 381 to 572); β1 integrin cyto, human β1A integrin C-terminal sequence containing the entire cytoplasmic domain (residues 738 to 798).

PINCH directly interacts with ILK in vitro.

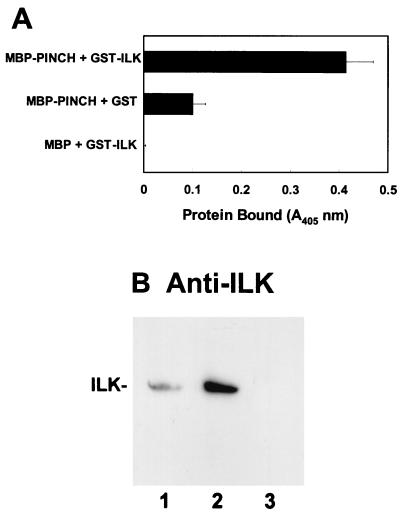

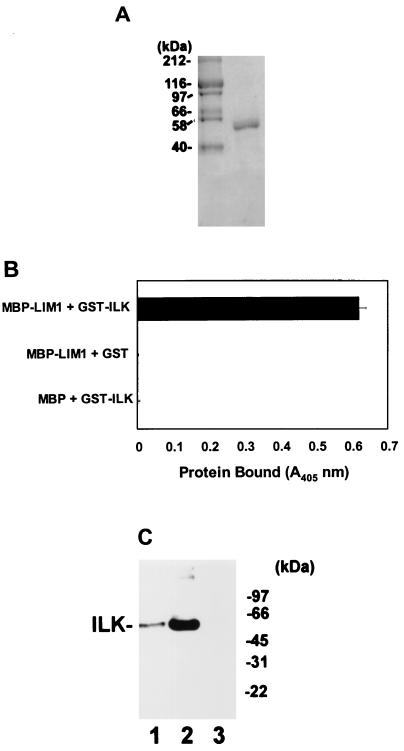

To test if PINCH could directly interact with ILK in vitro, we expressed an MBP-PINCH fusion protein, and MBP as a control, in E. coli by using pMAL-C2 expression vectors (New England Biolabs) and isolated them by affinity chromatography with amylose-agarose beads. The ability of purified recombinant MBP-PINCH to interact with a recombinant GST-ILK fusion protein was analyzed in a solid-phase-based binding assay. The results showed that the MBP-PINCH fusion protein readily interacted with the GST-ILK fusion protein (Fig. 2A, top row). In control experiments, no significant binding was detected when the GST-ILK fusion protein was replaced with GST (Fig. 2A, middle row) or when the MBP-PINCH fusion protein was replaced with MBP (Fig. 2A, bottom row) under otherwise identical conditions. Thus, consistent with the results of two-hybrid binding in yeast cells, PINCH directly interacts with ILK in vitro.

FIG. 2.

PINCH directly interacts with ILK in vitro. (A) Direct interaction between PINCH and ILK. Top, immobilized MBP-PINCH incubated with GST-ILK; middle, immobilized MBP-PINCH incubated with GST; bottom, immobilized MBP incubated with GST-ILK. The binding of GST-ILK or GST to immobilized MBP-PINCH or MBP was determined by ELISA as described in Materials and Methods. (B) Coprecipitation of human ILK by recombinant MBP-PINCH fusion protein. IMR-90 human fibroblast lysates (0.76 mg of protein/ml) were incubated with 15 μg of MBP-PINCH (lane 2) or 15 μg of MBP as a control (lane 3) in 500 μl of lysis buffer. MBP-PINCH and MBP were precipitated with amylose-Sepharose beads. Lane 1 was loaded with 38 μg of IMR-90 cell lysate. Human ILK in the cell lysate and the MBP-PINCH precipitate was detected by immunoblotting with a rabbit anti-ILK antibody.

PINCH and ILK associate with each other in mammalian cells.

We next tested whether PINCH could associate with native ILK derived from mammalian cells. Human IMR-90 cell lysates were incubated with MBP-PINCH and MBP (as a negative control). The MBP-PINCH fusion protein and MBP were then precipitated with amylose-agarose beads. Immunoblotting analyses of the precipitates showed that ILK was coprecipitated with MBP-PINCH (Fig. 2B, lane 2) but not MBP (Fig. 2B, lane 3), indicating that the recombinant PINCH protein is capable of associating with native ILK derived from mammalian cells.

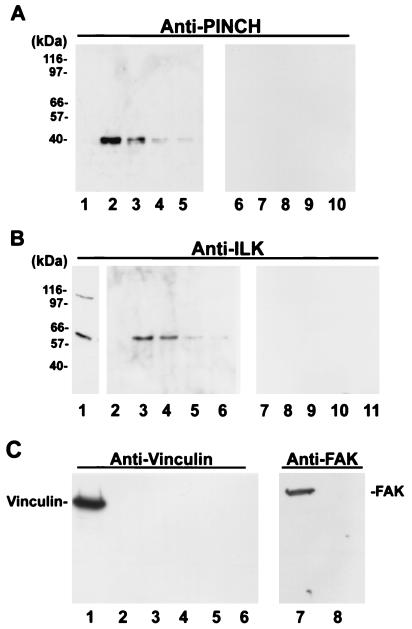

To test whether native PINCH and ILK proteins form a complex in mammalian cells, we covalently coupled rabbit anti-PINCH IgG to CNBr-activated Sepharose 4B beads and isolated PINCH and protein complexes containing PINCH by immunoaffinity chromatography with an anti-PINCH IgG–Sepharose 4B column. Immunoblotting analyses with an anti-PINCH antibody showed that, as expected, PINCH was eluted from the anti-PINCH immunoaffinity column under conditions that denature the immune complex (pH 2.5) (Fig. 3A, lanes 2 to 5). Under identical experimental conditions, no PINCH was detected in the elution fractions from a control rabbit IgG column containing Sepharose 4B beads covalently coupled with the same amount of irrelevant rabbit IgG (Fig. 3A, lanes 7 to 10). Analyses of elution fractions from the anti-PINCH immunoaffinity column by immunoblotting with an anti-ILK antibody showed that ILK was present in the fractions that contained PINCH (Fig. 3B, lanes 3 to 6) but absent from the fraction that lacked PINCH (Fig. 3B, lane 2). Moreover, the amount of ILK present in the elution fractions from the anti-PINCH immunoaffinity column correlated well with that of PINCH. In additional control experiments, no ILK was detected in the elution fractions from the control IgG column (Fig. 3B, lanes 8 to 11). To further test the specificity of the association between PINCH and ILK, we analyzed the fractions with antibodies recognizing other cellular proteins, such as vinculin and FAK, by immunoblotting. Neither vinculin (Fig. 3C, lanes 3 to 6) nor FAK (Fig. 3C, lane 8) was detected in the fractions containing PINCH, although abundant vinculin and FAK were detected in the total lysates (Fig. 3C, lanes 1 and 7). These results demonstrate that native PINCH and ILK proteins specifically associate with each other in cells to form a multiprotein complex that is devoid of vinculin and FAK.

FIG. 3.

Native PINCH protein associates with ILK but not with vinculin or FAK. CHO cell lysates (6 ml of 0.42 mg of protein/ml) were loaded onto a column containing rabbit anti-PINCH IgG–Sepharose 4B beads and washed, and proteins bound to the anti-PINCH IgG–Sepharose 4B beads were eluted as described in Materials and Methods. (A) Immunoblotting with anti-PINCH antibody. Lane 1, a fraction (0.4 ml/fraction) collected immediately before elution; lanes 2 to 5, fractions (0.4 ml/fraction) eluted with 100 mM glycine-HCl (pH 2.5). Each lane was loaded with 15 μl of sample (10 μl of the fraction plus 5 μl of reducing sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS]-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis sample buffer), electrophoresed on an SDS–8% polyacrylamide gel, transferred to an Immobilon membrane, and probed with a polyclonal anti-PINCH antibody. Fifteen elution fractions from each chromatography were analyzed, and only the position fractions are shown. In control experiments, an equal amount of CHO cell lysate was chromatographed through a column containing irrelevant rabbit IgG-Sepharose 4B beads under identical conditions, and the washing and elution fractions were analyzed by immunoblotting with the anti-PINCH antibody. No PINCH was detected in any of the fractions from the control column. Lanes 6 through 10 show the results obtained with control column fractions corresponding to lanes 1 through 5. (B) Immunoblotting with a rabbit polyclonal anti-ILK antibody (51-9 [0.12 μg/ml]). Lane 1, CHO cellular proteins (10 μg of protein/lane); lanes 2 to 11, samples identical to lanes 1 to 10, respectively, in panel A (washing and elution fractions). (C) Immunoblotting with a mouse monoclonal antivinculin antibody (V9131 [0.7 μg/ml]) (lanes 1 to 6) or a rabbit polyclonal anti-FAK antibody (A-17 [1 μg/ml]) (lanes 7 and 8). Lanes 1 and 7, CHO cellular proteins (10 μg of protein/lane); lanes 2 to 6, samples identical to lanes 1 to 5, respectively, in panel A (washing and elution fractions); lane 8, same sample as lane 2 in panel A. We performed immunoaffinity chromatography with lysates from human IRM-90 cells in addition to CHO cell lysates, and similar results were obtained (data not shown in the figure).

Mapping of a major ILK binding site to the first N-terminal LIM domain of PINCH.

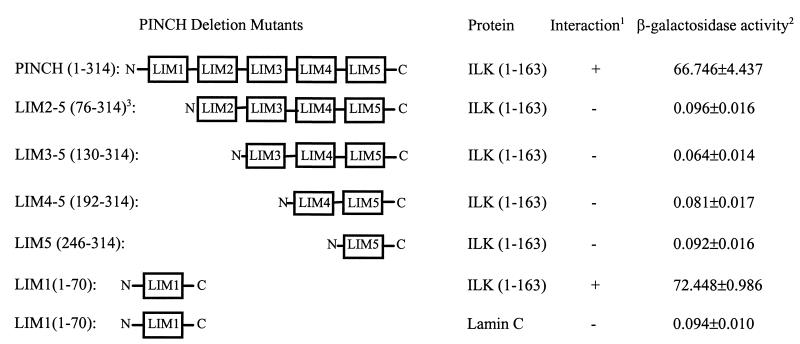

Having identified PINCH as a specific binding protein for ILK, we next sought to define the molecular sites involved in the PINCH-ILK interaction. PINCH comprises primarily five tandem LIM domains (20). To identify the LIM domain(s) involved in the PINCH-ILK interaction, we generated a series of PINCH mutants in which one or more LIM domains were deleted (Fig. 4). The ILK binding activity of the PINCH mutants was first tested in a yeast two-hybrid assay. Deletion of the N-terminal 75 residues, which eliminated the first LIM domain (LIM1) and five residues of the N-terminal zinc finger in the second LIM domain (the five LIM2 residues were deleted due to the presence of an EcoRI restriction site at this position), completely abolished ILK binding activity (Fig. 4). This suggests that the first and/or the second LIM domain, but not the three C-terminal LIM domains, mediates the interaction with ILK. To test whether LIM1 is sufficient for interacting with ILK, we generated a construct containing only the LIM1 domain of PINCH (residues 1 to 70). Analysis of yeast cells expressing the LIM1 domain of PINCH and the N-terminal domain of ILK showed that they readily interacted with each other (Fig. 4). In control experiments, no interaction was detected between the LIM1 domain and an irrelevant protein (lamin C), confirming the specificity of the interaction. Taken together, these results show that a major ILK binding site is located within the N-terminal-most LIM1 domain of PINCH and that none of the three C-terminal LIM domains of PINCH can interact with ILK.

FIG. 4.

Identification of a major ILK binding site in the N-terminal-most LIM domain of PINCH by mutational analysis. The PINCH and ILK cDNA fragments were inserted into the pB42AD vector and the pLexA vector, respectively. The numbers in parentheses indicate PINCH and ILK amino acid residues encoded by each construct. The lamin C construct contained the lamin C cDNA inserted into the pLexA vector and was used as a negative control. (Note 1) Positive interaction denotes growth of blue colonies on leucine-deficient selection medium containing 80 μg of X-Gal per ml (SD/Gal/Raf/−His/−Ura/−Trp/−Leu/X-Gal medium [Clontech]). (Note 2) β-Galactosidase activity was calculated based on measurement of five independently isolated yeast colonies and is presented as the mean value of absorbance at 600 nm ± the standard deviation. Under identical assay conditions, the β-galactosidase activity of the yeast cells harboring pLexA-53 (p53) and pB42AD-T (simian virus 40 large T antigen) was 20.143 ± 1.483. (Note 3) The N-terminal zinc finger in the second LIM domain (LIM2) was most likely disrupted in LIM2-5, as the consensus sequence CHQC (residues 71 to 75) was deleted. Amino acid residues 71 to 75 were eliminated during construction of the expression vector due to the presence of an EcoRI restriction site at this position.

To further analyze the LIM1-ILK interaction, we expressed an MBP fusion protein containing the LIM1 domain in E. coli and purified the MBP-LIM1 fusion protein by affinity chromatography (Fig. 5A). The binding of the PINCH LIM1 domain to ILK was analyzed in a solid-phase-based binding assay. The results showed that MBP-LIM1 readily interacted with GST-ILK but not with GST (Fig. 5B). Thus, consistent with the results of the yeast two-hybrid binding assays (Fig. 4), the LIM1 domain, like full-length PINCH, is capable of directly interacting with ILK in vitro.

FIG. 5.

LIM1 is sufficient for interacting with ILK. (A) Coomassie blue staining of MBP-LIM1 (right lane). MBP-LIM1 was generated and purified as described in Materials and Methods. Left lane, molecular mass standards. (B) LIM1 directly binds to ILK. Binding was analyzed by ELISA as described for Fig. 2A except that MBP-PINCH was replaced with MBP-LIM1. (C) Coprecipitation of human ILK by MBP-LIM1 fusion protein. IMR-90 human fibroblast lysates (0.3 mg of protein/ml) were incubated with equal amounts (6 μg) of MBP-LIM1 (lane 1), MBP-PINCH (lane 2), or MBP as a control (lane 3) in 170 μl of lysis buffer. MBP and the MBP fusion proteins were then precipitated with amylose-Sepharose beads. Human ILK was detected by immunoblotting with a rabbit anti-ILK antibody.

In addition to interacting with ILK in yeast cells and purified ILK recombinant protein in the solid-phase-based binding assays, the LIM1 domain of PINCH was also able to associate with native mammalian ILK. Figure 5C shows that MBP-LIM1 (lane 1), like MBP-PINCH (lane 2), precipitated ILK from lysates of human IMR-90 fibroblasts. The association of MBP-LIM1 with ILK depended on LIM1 sequence, as ILK was not coprecipitated with MBP under identical conditions (Fig. 5C, lane 3). Thus, a single LIM domain of PINCH (LIM1) is sufficient for mediating the interaction with ILK in mammalian cells.

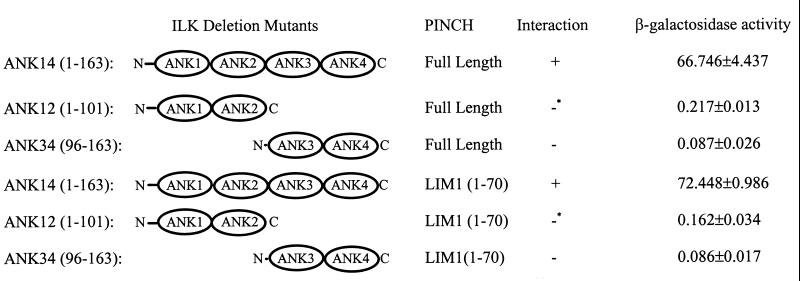

Deletion of either the first and second ANK repeats or the third and fourth ANK repeats of ILK dramatically reduces PINCH binding activity.

The N-terminal domain of ILK comprises primarily four ANK repeats (ANK1 through -4) (Fig. 6), which likely fold into a tertiary structure containing both α-helices and β-strands (14). To assess whether shorter peptides within the N-terminal domain of ILK could interact with PINCH and the LIM1 domain, we generated two ILK deletion mutants, which contain either the two N-terminal ANK repeats (ANK1 and ANK2) or the two C-terminal ANK repeats (ANK3 and ANK4). Together, they cover the entire ILK N-terminal domain (Fig. 6). ANK12 and ANK34, and ANK14 as a positive control, were tested in a yeast two-hybrid binding assay for their abilities to interact with PINCH as well as with the LIM1 domain of PINCH (Fig. 6). As expected, ANK14 readily bound to PINCH and the LIM1 domain (Fig. 6). By contrast, the interactions between ANK12 and PINCH or ANK12 and the LIM1 domain were dramatically reduced (<0.5% compared to the interactions between ANK14 and PINCH [or LIM1] based on β-galactosidase activity), and no interactions between ANK34 and PINCH or ANK34 and the LIM1 domain were detected (Fig. 6). Thus, neither the first and second ANK repeats (N-terminal region) nor the third and fourth ANK repeats (C-terminal region) are sufficient for mediating the interaction with PINCH in the absence of the other region, suggesting that residues from both regions contribute either directly to the binding of PINCH or indirectly to the formation of a protein conformation that is required for binding.

FIG. 6.

Deletion of either the first and second ANK repeats or the third and fourth ANK repeats of ILK dramatically reduces PINCH binding activity. Protein-protein interactions were determined with a yeast two-hybrid binding assay as described for Fig. 4. Asterisks indicate that very weak interactions may exist between the ANK12 repeats of ILK and PINCH or the PINCH LIM1 domain, as weak blue colonies harboring pLexA-ANK12 and pB42AD-PINCH or pB42AD-LIM1 were detected after a prolonged period of culture (5 days). No blue colonies harboring pLexA-ANK34 or pB42AD-LIM1 were detected during the longest period of culture used (6 days).

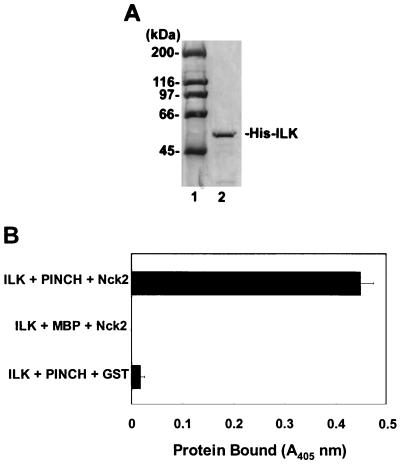

PINCH functions as a bridge protein physically linking ILK with Nck-2, an SH3/SH2-containing adapter protein associated with components of growth factor receptor kinase signaling pathways.

We recently identified Nck-2, a widely expressed adapter protein containing three N-terminal SH3 domains and one C-terminal SH2 domain, as another binding protein for PINCH (26). The Nck-2 binding site has been mapped to the fourth LIM domain of PINCH. Because Nck-2 is capable of associating with ligand-activated EGF and PDGF receptors via its SH2 domain and IRS-1 via its SH3 domains (26), and therefore is involved in growth factor receptor signal transduction pathways, we were interested in testing whether the interaction of ILK with PINCH could lead to association of ILK with Nck-2. To do this, we generated a His-tagged ILK (Fig. 7A, lane 2) and immobilized it on surfaces coated with chelated nickel via the polyhistidine tag. Immobilized ILK proteins were incubated with either MBP-PINCH or MBP (as a control), followed by incubation with GST–Nck-2 or GST (as a control). GST–Nck-2, but not GST, efficiently bound to the immobilized PINCH-ILK complex (Fig. 7B; compare the top and bottom rows). By contrast, no GST–Nck-2 directly bound to the immobilized ILK in the absence of PINCH proteins (Fig. 7B, middle row). Thus, ILK, together with PINCH, is capable of forming a multiprotein complex with Nck-2.

FIG. 7.

ILK associates with Nck-2 through PINCH. (A) Coomassie blue staining of His-tagged ILK (lane 2). His-tagged ILK was generated and purified as described in Materials and Methods. Lane 1, molecular mass standards. (B) Association of ILK with Nck-2 via PINCH. Top, immobilized His-ILK incubated with MBP-PINCH followed by incubation with GST-Nck-2; middle, immobilized His-ILK incubated with MBP followed by incubation with GST–Nck-2; bottom, immobilized His-ILK incubated with MBP-PINCH followed by incubation with GST. GST–Nck-2 or GST protein bound was detected by ELISA as described in Materials and Methods.

PINCH is concentrated in peripheral ruffles and recruited to α5β1 integrin-rich cell adhesion sites in cells spreading on fibronectin.

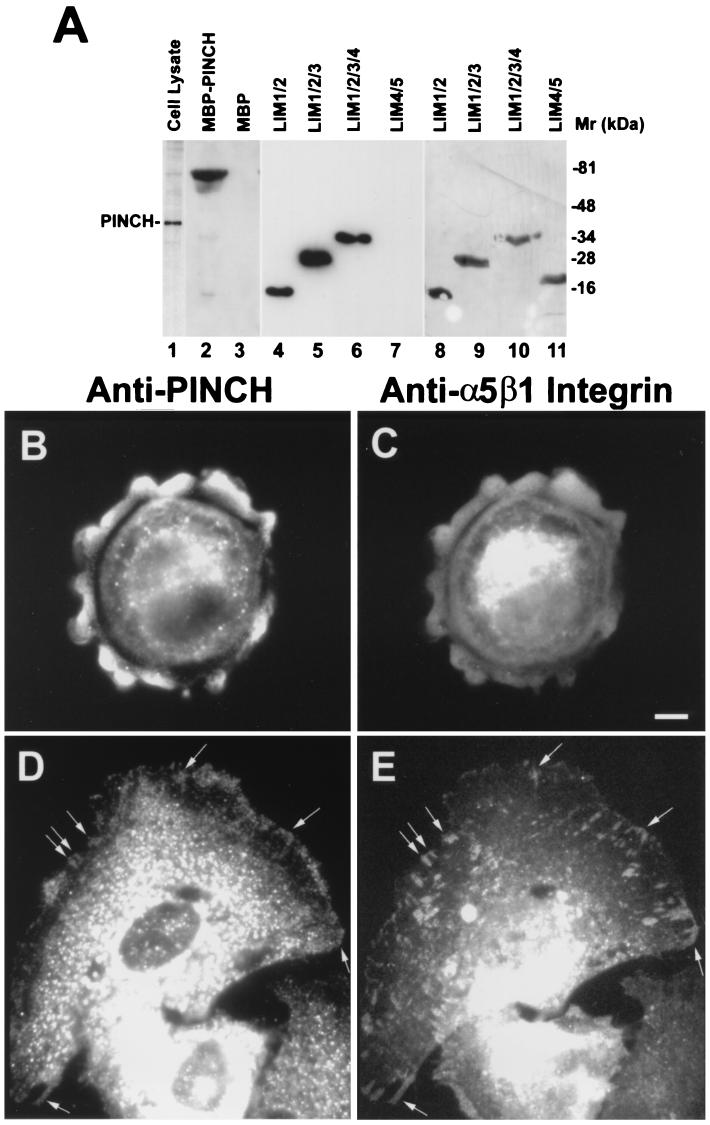

Previous studies have shown that ILK colocalizes with the β1 integrins and is involved in regulation of integrin-mediated cell adhesion to fibronectin (10). To analyze subcellular localization of PINCH, we generated a monoclonal anti-PINCH antibody (25.9) that recognizes both recombinant and native mammalian PINCH (Fig. 8A, lanes 1 to 3). Immunoblotting analyses with His-tagged fusion protein containing various PINCH sequences showed that it recognizes an epitope located within the N-terminal 129 amino acid residues of PINCH (Fig. 8A, lanes 4 and 8). The anti-PINCH antibody did not react with a His-tagged fusion protein containing the C-terminal region of PINCH (Fig. 8A, lanes 7 and 11) or other His-tagged fusion proteins containing irrelevant protein sequences (data not shown), further confirming the specificity of the antibody.

FIG. 8.

Subcellular localization of PINCH in cells spreading on fibronectin. (A) Immunoblotting with monoclonal antibody 25.9. Lane 1, CHO cell lysate (10 μg/lane); lane 2, MBP-PINCH (0.5 μg/lane); lane 3, MBP (0.5 μg/lane); lanes 4 and 8, His fusion protein containing PINCH LIM1 and LIM2 domains (residues 1 to 129); lanes 5 and 9, His fusion protein containing PINCH LIM1, LIM2, and LIM3 domains (residues 1 to 187); lanes 6 and 10, His fusion protein containing PINCH LIM1, LIM2, LIM3, and LIM4 domains (residues 1 to 248); lanes 7 and 11, His fusion protein containing PINCH LIM4 and LIM5 domains (residues 188 to 314). Lanes 4 through 7 were loaded at 0.1 μg/lane, and lanes 8 through 11 were loaded at 0.5 μg/lane. Lanes 1 through 7 were blotted with monoclonal antibody 25.9, and lanes 8 through 11 were stained with Coomassie blue. (B to E) Immunofluorescence staining of cells spreading on fibronectin. Rat mesangial cells were plated on fibronectin for 1 (B and C) or 4 (D and E) h, fixed, and double stained with mouse monoclonal anti-PINCH antibody (B and D) and rabbit anti-α5β1 integrin antibody (C and E) as described in Materials and Methods. The bar in panel C is 5 μm and applies to panels B through E.

To detect subcellular localization of PINCH in cells that were in early stages of cell spreading, we stained kidney mesangial cells that were newly plated on fibronectin-coated surfaces with the monoclonal anti-PINCH antibody. The results showed that PINCH was highly concentrated at the peripheral ruffles of spreading cells (Fig. 8B). Previous studies have shown that α5β1 integrins are also concentrated in peripheral ruffles of cells spreading on fibronectin (see, for example, reference 25). We confirmed the colocalization of the α5β1 integrins with PINCH in the peripheral ruffles by costaining the cells with a rabbit polyclonal anti-α5 integrin antibody (Fig. 8C). Later, in cells that were well spread, clusters of PINCH were also detected in lamellipodia (Fig. 8D). Noticeably, PINCH was detected in many cell adhesion sites at the cell periphery, where α5β1 integrins were clustered (Fig. 8D and E), suggesting that PINCH is involved in integrin-mediated cell adhesion, spreading, or signal transduction. However, compared to cells that were in early stages of spreading (Fig. 8B and our unpublished observations), PINCH was less concentrated in the periphery of well-spread cells (Fig. 8D), suggesting that the presence of high concentrations of PINCH in the periphery of cells is transient during cell spreading. Intriguingly, we observed a number of α5β1 integrin clusters that lacked a detectable amount of PINCH (Fig. 8D and E), indicating that PINCH is not a permanent or structurally essential component of all integrin-rich cell adhesion sites.

DISCUSSION

PINCH is a widely expressed LIM-containing protein that was initially identified from screening of a human cDNA library with antibodies recognizing senescent erythrocytes (20). In this study, we have demonstrated that PINCH is a specific binding protein of ILK, a receptor-proximal component of the cell adhesion signaling pathway. Moreover, we show that PINCH is recruited to peripheral ruffles and integrin-rich sites in spreading cells. Thus, PINCH can now be considered a member of a group of the cytoplasmic LIM proteins, including cysteine-rich proteins (5, 30), zyxin (3, 4, 13, 22), and paxillin (27, 28), that are involved in cell-extracellular matrix interactions.

Several lines of evidence indicate that the ILK-PINCH interaction is highly specific. Firstly, a high percentage (96%) of the positive clones identified in the yeast two-hybrid screen encode PINCH, demonstrating that the binding is highly reproducible. Secondly, the ILK-PINCH interaction has been consistently observed under a variety of experimental conditions. For example, in addition to interacting in yeast cells, the purified PINCH and ILK recombinant proteins readily bind to each other in vitro. Thus, ILK binding and PINCH binding are intrinsic activities of PINCH and ILK. Furthermore, native PINCH and ILK were coisolated from mammalian cells by immunoaffinity chromatography, suggesting that they could also form a multiprotein complex in cells. Finally, mutational studies demonstrate that the PINCH-ILK interaction is mediated by specific domains of the proteins. Although PINCH comprises five LIM domains, a single LIM domain (LIM1) at the N terminus of PINCH is sufficient for interacting with ILK, and none of the three C-terminal LIM domains of PINCH interact with ILK. On the other hand, consistent with other protein-protein recognition systems utilizing multiple ANK repeats (2, 14, 15), deletion of either the first and second ANK repeats or the third and fourth ANK repeats of ILK dramatically reduced the PINCH binding activity.

The ILK binding activity of PINCH described in this report is consistent with its coordinated expression patterns in vivo. For example, we recently found that ILK is expressed in the extracellular-matrix-rich dermis, the hair follicles, and the basal cells of the interfollicular epidermis in mouse skin, but its expression is lost in the suprabasal layers of postmitotic keratinocytes that are undergoing terminal differentiation (32). In the same study, we found that PINCH exhibited a similar expression pattern in mouse skins (32). Additional evidence indicating that PINCH functions in cell adhesion and therefore in the ILK signaling pathway comes from recent genetic analyses of PINCH homologues in Caenorhabditis elegans and Drosophila melanogaster. A mutation in a C. elegans PINCH homologue, unc-97, causes locomotory defects resulting in an uncoordinated-movement phenotype, indicating that the PINCH homologue is functionally important for muscle attachment assembly and touch neuron functions in C. elegans (10a). The Drosophila PINCH homologue, d-PINCH, is expressed in both the body wall muscle and epidermal tendon cells during embryogenesis, coincident with integrin subunit expression in those tissues (10a). Moreover, Hobert and coworkers have shown that the loss-of-function phenotype of unc-97 resembles that of the Pat (loss of dense body components β-integrin/pat-3) phenotype (10a). In further support of a role for PINCH in cell adhesion, we show in this study that PINCH is recruited to α5β1 integrin-rich sites in cells spreading on fibronectin. Intriguingly, while PINCH was readily detected in many α5β1 integrin-rich adhesion sites, it was not detected in all α5β1 integrin-containing cell adhesion sites. Thus, we propose that PINCH is a transient or signaling component rather than a structurally essential component of all cell adhesion sites. This is consistent with a regulatory rather than a structural role for ILK in integrin-mediated cellular processes.

The colocalization of PINCH with α5β1 integrins appears to be mediated indirectly through other proteins, as we failed to detect a direct interaction between the PINCH LIM domains and the β1 integrin cytoplasmic domain in yeast two-hybrid binding assays (Table 1). Additionally, we have tested the ability of several major focal adhesion components, including vinculin and FAK, to interact with PINCH but failed to detect any interactions (Fig. 3C). Thus, although we cannot completely rule out the possibility that PINCH is recruited to the integrin-rich cell adhesion sites through some other structural components, the ability of ILK to interact with PINCH that was demonstrated in this study, together with previous observations that ILK binds to the integrins and is localized in cell adhesion sites (10), strongly suggests that PINCH is recruited to the integrin-rich cell adhesion sites via ILK. Consistent with this, ILK also appears to be a dynamic signaling component of the integrin signaling pathways, and ILK activity is transiently stimulated upon cell adhesion to fibronectin (8).

Recently, we have identified a novel SH2/SH3-containing adapter protein, Nck-2, as another binding protein for PINCH (26). PINCH binds to Nck-2 and ILK through two separate LIM domains (LIM4 for Nck-2 [26] and LIM1 for ILK [this study]). Furthermore, we demonstrate in this study that Nck-2 associated with ILK via the protein-protein interactions mediated by PINCH. Thus, PINCH may function as a bridge molecule physically linking ILK to Nck-2 in signal transduction. Because Nck-2 is capable of recognizing ligand-activated EGF and PDGF receptors and IRS-1, the ILK-PINCH-Nck interactions could potentially connect integrins and ILK with components of the growth factor receptor kinase signaling pathways. Indeed, it has been well documented that integrin receptors can colocalize and physically associate with components of growth factor signaling pathways (1, 16, 18, 24, 29). For example, the αvβ3 integrin, which associates with ILK in vivo (7, 10), could also form a complex with activated PDGF receptors (1, 24), IRS-1 (29), or the insulin receptor (24). Recent studies have shown that ILK is intimately involved in the growth factor and Wnt signaling pathways (8, 17). The kinase activity of ILK is regulated not only by cell adhesion to fibronectin but also by insulin in a phosphoinositide-3-OH kinase-dependent manner (8). Furthermore, Delcommenne et al. have demonstrated that ILK can directly phosphorylate PKB/AKT on serine-473, one of the two phosphorylation sites involved in the activation of PKB/AKT, and regulate GSK-3 (8). The ability of ILK to receive signals from various upstream regulators and transduce signals to different downstream effectors is likely controlled by, at least in part, formation of specific signaling complexes. Thus, during signal transduction, ILK not only is associated with the integrins but also, at least transiently, is in physical contact with components of the growth factor and Wnt signaling pathways. Given the interactions of PINCH with ILK and other signaling proteins (e.g., Nck-2) and the colocalization with the integrins, PINCH likely functions as an adapter protein mediating associations of ILK with other components of the signaling pathways.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Shoukat Dedhar for providing the human ILK cDNA and anti-human ILK antibody, Oliver Hobert (Massachusetts General Hospital) for sharing unpublished results, Keith Burridge (University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill) for valuable discussions, Mary Beckerle (University of Utah) for providing human zyxin cDNA, John Couchman and Anne Woods (University of Alabama at Birmingham) for providing rat kidney mesangial cells, and the Hybridoma Core Facility of the University of Alabama at Birmingham for technical assistance in the production of the mouse monoclonal anti-PINCH antibodies.

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health grant DK54639, research project grant 98-220-01-CSM from the American Cancer Society, and research grants from the American Heart Association, the American Lung Association, the Francis Families Foundation, and the V Foundation for Cancer Research (to C.W.). F.L. was supported by The Cell Adhesion and Matrix Research Center of the University of Alabama at Birmingham. C.W. is a V Foundation Scholar and a Parker B. Francis Fellow in Pulmonary Research of the Francis Families Foundation.

Y.T. and F.L. contributed equally to this work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bartfeld N S, Pasquale E B, Geltosky J E, Languino L R. The alpha v beta 3 integrin associates with a 190-kDa protein that is phosphorylated on tyrosine in response to platelet-derived growth factor. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:17270–17276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bork P. Hundreds of ankyrin-like repeats in functionally diverse proteins: mobile modules that cross phyla horizontally? Proteins. 1993;17:363–374. doi: 10.1002/prot.340170405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2a.Clontech. Yeast protocol handbook. Clontech Laboratories, Palo Alto, Calif.

- 3.Crawford A W, Beckerle M C. Purification and characterization of zyxin, an 82,000-dalton component of adherens junctions. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:5847–5853. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crawford A W, Michelsen J W, Beckerle M C. An interaction between zyxin and alpha-actinin. J Cell Biol. 1992;116:1381–1393. doi: 10.1083/jcb.116.6.1381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crawford A W, Pino J D, Beckerle M C. Biochemical and molecular characterization of the chicken cysteine-rich protein, a developmentally regulated LIM-domain protein that is associated with the actin cytoskeleton. J Cell Biol. 1994;124:117–127. doi: 10.1083/jcb.124.1.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dawid I B, Breen J J, Toyama R. LIM domains: multiple roles as adapters and functional modifiers in protein interactions. Trends Genet. 1998;14:156–162. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(98)01424-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dedhar S, Hannigan G E. Integrin cytoplasmic interactions and bidirectional transmembrane signal transduction. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1996;8:657–669. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(96)80107-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Delcommenne M, Tan C, Gray V, Rue L, Woodgett J, Dedhar S. Phosphoinositide-3-OH kinase-dependent regulation of glycogen synthase kinase 3 and protein kinase B/AKT by the integrin-linked kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:11211–11216. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.19.11211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gietz D, St. Jean A, Woods R A, Schiestl R H. Improved method for high efficiency transformation of intact yeast cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:1425. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.6.1425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hannigan G E, Leung-Hagesteijn C, Fitz-Gibbon L, Coppolino M G, Radeva G, Filmus J, Bell J C, Dedhar S. Regulation of cell adhesion and anchorage-dependent growth by a new beta 1-integrin-linked protein kinase. Nature. 1996;379:91–96. doi: 10.1038/379091a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10a.Hobert, O., D. G. Moerman, K. A. Clark, M. C. Beckerle,, and G. Ruvkun. A conserved LIM protein that affects muscular adherens junction integrity and mechanosensory function in C. elegans. J. Cell Biol., in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Jurata L W, Gill G N. Structure and function of LIM domains. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1998;228:75–113. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-80481-6_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li F, Liu J, Mayne R, Wu C. Identification and characterization of a mouse protein kinase that is highly homologous to human integrin-linked kinase. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1997;1358:215–220. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(97)00089-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Macalma T, Otte J, Hensler M E, Bockholt S M, Louis H A, Kalff-Suske M, Grzeschik K H, von der Ahe D, Beckerle M C. Molecular characterization of human zyxin. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:31470–31478. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.49.31470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Michaely P, Bennett V. The ANK repeat: a ubiquitous motif involved in macromolecular recognition. Trends Cell Biol. 1992;2:127–129. doi: 10.1016/0962-8924(92)90084-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Michaely P, Bennett V. The membrane-binding domain of ankyrin contains four independently folded subdomains, each comprised of six ankyrin repeats. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:22703–22709. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miyamoto S, Teramoto H, Gutkind J S, Yamada K M. Integrins can collaborate with growth factors for phosphorylation of receptor tyrosine kinases and MAP kinase activation: roles of integrin aggregation and occupancy of receptors. J Cell Biol. 1996;135:1633–1642. doi: 10.1083/jcb.135.6.1633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Novak A, Hsu S C, Leung-Hagesteijn C, Radeva G, Papkoff J, Montesano R, Roskelley C, Grosschedl R, Dedhar S. Cell adhesion and the integrin-linked kinase regulate the LEF-1 and beta-catenin signaling pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:4374–4379. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.8.4374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Plopper G E, McNamee H P, Dike L E, Bojanowski K, Ingber D E. Convergence of integrin and growth factor receptor signaling pathways within the focal adhesion complex. Mol Biol Cell. 1995;6:1349–1365. doi: 10.1091/mbc.6.10.1349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Radeva G, Petrocelli T, Behrend E, Leung-Hagesteijn C, Filmus J, Slingerland J, Dedhar S. Overexpression of the integrin-linked kinase promotes anchorage-independent cell cycle progression. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:13937–13944. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.21.13937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rearden A. A new Lim protein containing an autoepitope homologous to “senescent cell antigen.”. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;201:1124–1131. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.1822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roman J, LaChance R M, Broekelmann T J, Kennedy C J, Wayner E A, Carter W G, McDonald J A. The fibronectin receptor is organized by extracellular matrix fibronectin: implications for oncogenic transformation and for cell recognition of fibronectin matrices. J Cell Biol. 1989;108:2529–2543. doi: 10.1083/jcb.108.6.2529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sadler I, Crawford A W, Michelsen J W, Beckerle M C. Zyxin and cCRP: two interactive LIM domain proteins associated with the cytoskeleton. J Cell Biol. 1992;119:1573–1587. doi: 10.1083/jcb.119.6.1573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schmeichel K L, Beckerle M C. The LIM domain is a modular protein-binding interface. Cell. 1994;79:211–219. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90191-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schneller M, Vuori K, Ruoslahti E. Alpha v beta 3 integrin associates with activated insulin and PDGF beta receptors and potentiates the biological activity of PDGF. EMBO J. 1997;16:5600–5607. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.18.5600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tawil N, Wilson P, Carbonetto S. Integrins in point contacts mediate cell spreading: factors that regulate integrin accumulation in point contacts vs. focal contacts. J Cell Biol. 1993;120:261–271. doi: 10.1083/jcb.120.1.261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tu Y, Li F, Wu C. Nck-2, a novel Src homology 2/3-containing adaptor protein that interacts with the LIM-only protein PINCH and components of growth factor receptor kinase signaling pathways. Mol Biol Cell. 1998;9:3367–3382. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.12.3367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Turner C E. Paxillin: a cytoskeletal target for tyrosine kinases. Bioessays. 1994;16:47–52. doi: 10.1002/bies.950160107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Turner C E, Glenney J R, Jr, Burridge K. Paxillin: a new vinculin-binding protein present in focal adhesions. J Cell Biol. 1990;111:1059–1068. doi: 10.1083/jcb.111.3.1059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vuori K, Ruoslahti E. Association of insulin receptor substrate-1 with integrins. Science. 1994;266:1576–1578. doi: 10.1126/science.7527156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weiskirchen R, Pino J D, Macalma T, Bister K, Beckerle M C. The cysteine-rich protein family of highly related LIM domain proteins. J Biol Chem. 1995;70:28946–28954. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.48.28946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu C, Keightley S Y, Leung-Hagesteijn C, Radeva G, Coppolino M, Goicoechea S, McDonald J A, Dedhar S. Integrin-linked protein kinase regulates fibronectin matrix assembly, E-cadherin expression, and tumorigenicity. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:528–536. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.1.528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xie W, Li F, Kudlow J E, Wu C. Expression of the integrin-linked kinase (ILK) in mouse skins: loss of expression in suprabasal layers of the epidermis and up-regulation by erbB-2. Am J Pathol. 1998;153:367–372. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65580-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]