Abstract

Purpose

This review describes the current scientific evidence of therapeutic options in unresectable oral squamous cell carcinoma.

Methods

This study followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA). We searched MEDLINE (Via PubMed) to identify studies assessing treatments for unresectable oral squamous cell carcinoma. The methodological quality assessment of the included studies was performed using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) checklist tool. The evidence was organized and presented using tables and narrative synthesis.

Results

Thirty-three studies met the eligibility criteria. Most studies had an observational design. The sample size varied from 16 to 916 participants. The methodology quality of the included studies ranged from 2.5 to 10 using the JBI tool. Overall, the optimal treatment of patients with unresectable oral cancer is challenging, so there is a sprinkling of studies assessing a variety of therapeutic options, such as radiotherapy, chemotherapy, concurrent chemoradiotherapy, immunotherapy, targeted therapy plus chemotherapy or radiotherapy, and gene therapy plus chemotherapy.

Conclusion

There is lacking evidence about the benefits of some therapeutic options for unresectable oral squamous cell carcinoma. Overall, these patients can be treated using a multimodal approach such as concurrent chemoradiotherapy or induction chemotherapy followed by chemoradiotherapy, which have shown good clinical outcomes. However, other options could be considered depending on the assessment of risk/benefits, tumor extension, and patient values and preferences.

Keywords: mouth neoplasms, unresectable oral cancer, oral squamous cell carcinoma, treatment, therapy

Introduction

Oral cancer is a health issue globally. It fully meets the criteria to be considered a public health problem such as high mortality rate, the impact of the condition on an individual level, and impact on wider society.1 To illustrate, it has been reported that around 650,000 new cases are diagnosed annually; although it represents just 2% of the tumor incidence worldwide, the major reason for concern is its high mortality rate of around 50%.2 Regarding the region‐specific incidence age‐standardized rates by sex for oral cancer in 2018, there is a higher incidence of this oral disease for men than women in all countries, being Melanesia, South Central Asia, Australia/New Zealand, Eastern Europe, Western Europe, and Northern America, the regions with the highest incidence.3 Likewise, this malignancy accounts for over 140,000 deaths per year and its age-standardized mortality rates can vary depending on geographical settings.3

This disease stands amongst the six most common cancers worldwide, and about 40% of head and neck tumors are oral squamous cell carcinomas,4 which is the most common type of mouth cancers. Moreover, oral cancer has a substantial financial burden on the public healthcare system and produces both physical and psychological impacts on people suffering from this disease such as swallowing function, speech difficulties, and self-image concerns.5

Currently, there are important technological advances in cancer management and oncology research, but oral carcinoma still has a poor prognosis and its treatment involves usually severe physical and psychological after-effects.6,7 Amongst the main therapeutic options for oral cancer are surgery, radiotherapy (RT), and chemotherapy (CT);8,9 commonly locoregionally oral neoplasms are treated by surgical approach considered as the gold standard treatment,10 while those advanced or aggressive oral tumors with high probabilities of relapse after definitive treatment with surgery or RT are treated using a multimodal approach that combines surgery and pre/postoperative RT or CT.11,12 However, for those patients with unresectable disease, when the surgical approach is not feasible because of the extension of lesion, surgery is expected to result in poor functional outcomes, patients’ poor status or patient values and preferences, the optimal therapeutic options are largely unclear.13

Likewise, it has been reported that the evidence on the benefits of therapeutic interventions for unresectable oral cancer is lacking.14 Thus, this review aimed to describe the current scientific evidence about therapeutic options in unresectable oral squamous cell carcinoma.

Methods

This review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA).15 The aim and all methods used in this study were specified a priori in a protocol (available on request).

Search Strategy

We searched MEDLINE (via PubMed) to identify relevant studies assessing any therapeutic options in unresectable oral squamous cell carcinoma. We used MeSH descriptor, free text, and treasure terms such as “mouth neoplasms”, “oral cancer”, “oral carcinoma”, “buccal carcinoma”, “unresectable”, “advanced”, “inoperable”, “therapeutics”, “treatment”, “management” and “therapy” (Supplementary Material 1). There were no language restrictions, and the search was filtered by the last 10 years in order to include the most updated evidence into the review. The last research was carried out on April 12, 2021. Also, a cited reference search was conducted.

Selection of Studies

Studies of different epidemiological designs (randomized controlled trial (RCT), clinical trial, cohort, and case–control studies) and published after 2010 were included. They had to evaluate any therapeutic option in individuals diagnosed with primary unresectable oral squamous cell carcinoma, defined as patients with advanced mouth neoplasm, no evidence of distant metastases, and unsuitable to surgical treatments for any reason. If a study was reported in more than one publication, only the most recent version was considered. Conversely, studies only on diagnosis and prognosis were excluded. Likewise, studies only focused on interventions before or after surgical treatments were excluded.

We managed all retrieved records using the Rayyan16 website. Initially, the duplicates automatically were removed, then at least two appraisers independently screened all titles/abstracts to exclude unrelated studies. Subsequently, full articles were obtained for a final decision. Detailed reasons for exclusion of any study considered relevant were clearly stated.

Methodological Critical Appraisal and Data Extraction

We critically appraised all included studies using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI)17 checklist for each study design included in this review. Overall, these checklists rate the quality of different factors such as selection, measurement, and comparability of groups. This tool gives a score for RCT (maximum of 13), clinical trial (maximum of 9), cohort (maximum of 11), and case–control (maximum of 10). There is no cut-off point, so a higher score indicates better methodology quality of the study.

At least two reviewers independently conducted all processes of study selection, methodological critical appraisal, and data extraction. If there were any disagreements, they were resolved by consensus, and when necessary, an additional reviewer participated in the discussion until an agreement was reached. We extracted data about general characteristics of the study (authors, publication year, design, country, aim, sample size, sample features, and risk factors reported) and characteristics of the therapeutic intervention (type, dose, comparison, outcomes, and conclusion about its effectiveness). The evidence was organized and presented using tables and narrative synthesis.

Results

Selection of Studies

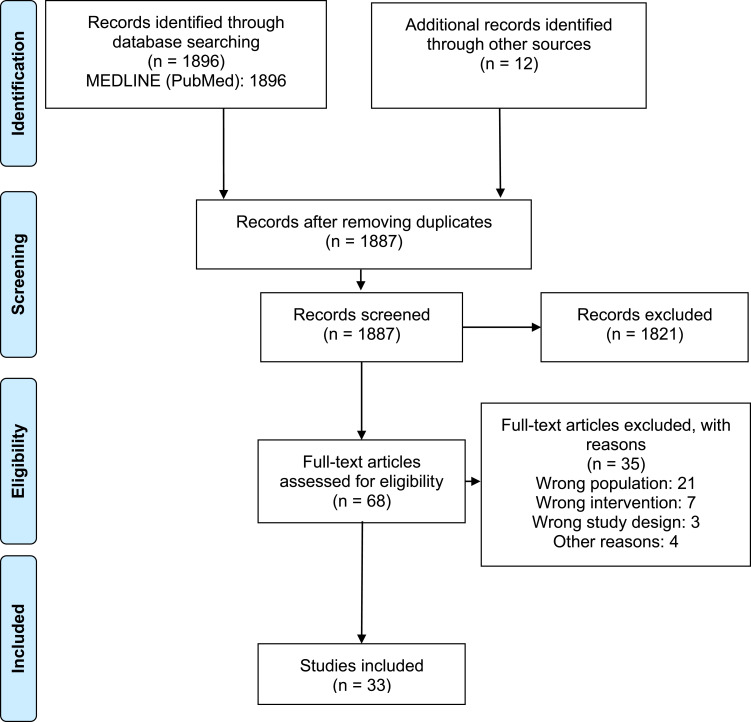

1887 records were identified after removing duplicates. After the title and abstract screening, 68 articles were obtained for final full‑text review; 33 studies18–50 met the eligibility criteria (Figure 1). The list of excluded studies along with exclusion rationale is available in Supplementary Material 2.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart describing the selection of studies.

Notes: Adapted from Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71.15 Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/legalcode).

Characteristics of the Included Studies

All selected studies18–50 were published in English language between 2011 and 2020. There were 15 retrospective cohort studies,22,24–26,28,34,36–42,47,50 eight were prospective cohort studies,19,23,29,32,33,35,44,46 six were RCTs,18,21,27,30,31,43 four were clinical trials,20,45,48,49 and none was case-control study. The sample size varied from 1627 to 97642 participants. There were eight studies from India,19,21,34,36–38,43,46 six from Japan,26,27,32,33,40,45 four from Taiwan,20,42,47,48 three from the United States,25,35,41 two from China,30,31 two from Pakistan,28,49 while the other studies were one from each of the following: Canada,50 Hungary,44 Italy,23 Iran,29 Spain,39 The Netherlands,24 Thailand,22 and Ukraine.18 Only 14 studies20,22,24,26,28,34–38,41–43,46 reported oral cancer risk factors, such as smoking, alcohol consumption and betel chewing. All general characteristics of the selected studies are presented in Supplementary Material 3.

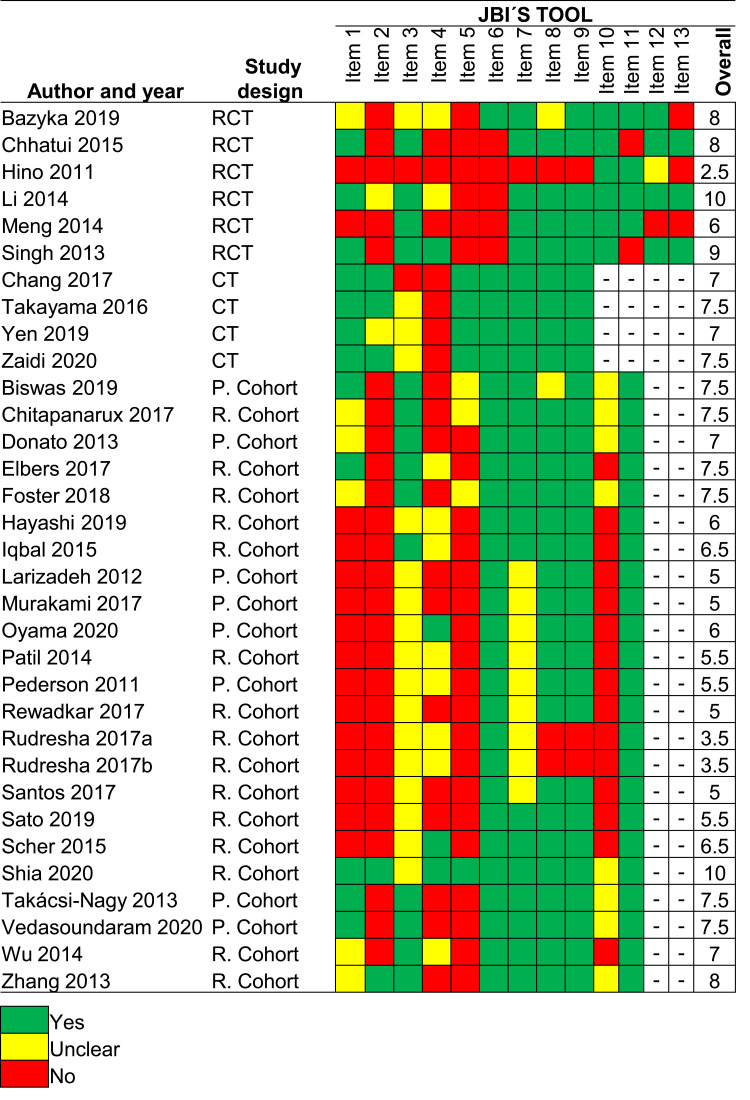

The Methodological Quality of the Included Studies

Using the JBI´s critical appraisal checklist tool, the mean score was 7.5 ± 2.7 (range from 2.5 to 10), 7.5 ± 0.3 (range from 7 to 10), and 6.3 ± 1.5 (range from 3.5 to 10) for RCTs, clinical trials, and cohort studies, respectively. The results in detail for each study are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The methodological quality of the included studies by design.

Abbreviations: CT, clinical trial; P, prospective; R, retrospective; RCT, randomized controlled trial.

Therapeutic Options in Unresectable Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Overall, included studies assessed a variety of therapeutic options in unresectable oral squamous cell carcinoma. Twenty-seven studies18,19,21–29,32–42,44–46,49,50 assessed different therapies that in some way combined the use of CT and RT, three studies42,43,50 evaluated RT alone, two studies31,47 assessed CT alone, four studies20,31,43,48 examined the combination of targeted therapy plus CT or RT, and only one study for each of the interventions of immunotherapy21 and gene therapy.30 The main outcomes reported were overall survival (OS), locoregional control (LRC), progression-free survival (PFS), disease-free survival (DFS), complete response (CR), and cancer-specific survival (CSS). All these studies used different approaches, doses, outcomes, etc. Thus, the scientific evidence about the effectiveness of the main treatments for unresectable oral cancer is summarized by groups as follows:

Concurrent Chemoradiotherapy

Concurrent chemoradiotherapy (CCRT) implies the use of CT delivered simultaneously with RT. This approach has multiple advantages, such as the improvement of the chances of LRC, OS rates, and organ-preserving intent. Moreover, CT given as part of CCRT could act systemically and possibly prevent distant metastases. Likewise, this therapeutic option improves function and cosmetic outcomes compared with surgical approaches. Fourteen studies19,21,24–28,32,33,35,40–42,50 evaluated the use of CCRT, two of them were clinical trials,25,27 one was a RCT,21 and the others were observational studies.19,24,26,28,32,33,35,40–42,50 The number of participants for each intervention group varied from 1627 to 25642 people. Twelve studies19,21,24–26,28,32,33,35,40,42,50 only focused on patients with clinical stage III/IV oral cancer, whereas two studies27,41 also included other clinical stages. The main outcomes assessed were OS and LRC, which were evaluated in 1024–28,32,33,35,40,41,50 and seven24–26,33,35,40,41 studies, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of Evidence on Concurrent Chemoradiotherapy

| Author and Year | Clinical Stages | Interventions | Follow-Up | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biswas 201919 | III IV |

Arm 1 (n=20): Age <40 Y, CCRT (cisplatin + RT 70 Gy) Arm 2 (n=26): Age >40 Y, CCRT (cisplatin + RT 70 Gy |

11.1 M | OR: Arm 1, 63.5%; Arm 2, 65.9% |

| Chhatui 201521 | III IV |

(n=25): CCRT (cisplatin + RT 70 Gy) | 15 M | DFS: 69% CR: 52% |

| Elbers 201724 | III IV |

(n=100): CCRT (cisplatin + RT up to 70 Gy) | 13 M | OS [5 Y]: 22% LRC [5 Y]: 49% DFS [5 Y]: 22% DSS [5 Y]: 39% |

| Foster 201825 | III IV |

(n=140): CCRT (CT + RT up to 75 Gy) | 5.7 Y | OS [5 Y]: 63.2% LRC [5 Y]: 78.6% PFS [5 Y]: 58.7% DC [5 Y]: 87.2% |

| Hayashi 201926 | III IV |

(n=46): CCRT (docetaxel + cisplatin + RT up to 60 Gy) | 40 M | OS [3Y]: 64.3% LRC [3Y]: 84.3% |

| Hino 201127 | II III IV |

(n=16): CCRT (S-1+ RT 30 Gy) | 7.4 M | OR: 87.5% OS [Median]: 42.5 M PFS [Median]: 6.3 M |

| Iqbal 201528 | III IV |

(n=63): CCRT (gemcitabine + cisplatin + RT 55 Gy) | 60 M | OS [5 Y]: 30% PFS [5 Y]: 49% DFS [5 Y]: 30% |

| Murakami 201732 | III IV |

(n=47): CCRT (S-1+ RT up to 70 Gy) | 22 M | OS [3 Y]: 37% PFS [3 Y]: 27% |

| Oyama 202033 | III IV |

(n=37): CCRT (docetaxel + nedaplatin + RT up to 70 Gy) |

40 M | OS [5 Y]: 64.5% DF [5 Y]: 59.9% LC [5 Y]: 85.5% |

| Pederson 201135 | III IV |

(n=20): CCRT (5-FU + hydroxyurea + RT up to 75 Gy) | 60 M | OS [2 Y]: 76% OS [5 Y]: 76% DFS [2 Y]: 71% DFS [5 Y]: 71% LRC [2 Y]: 90% LRC [5 Y]: 90% |

| Sato 201940 | III IV |

(n=17): CCRT (docetaxel+ cisplatin + RT up to 66 Gy) | 41 M | OS [3 Y]: 52.9% OS [5 Y]: 33.0% LRC [3 Y]: 50.9% LRC [5 Y]: 50.9% |

| Scher 201541 | I II III IV |

(n=73): CCRT (cisplatin + carboplatin + 5-FU or paclitaxel + RT up to 70 Gy) | 73.1 M | OS [5 Y]: 15% LRC [5 Y]: 37.4% DC [5 Y]: 70.2% |

| Shia 202042 | III IV |

Arm 1 (n=256): CCRT Arm 2 (n=227): Non-treatment |

15 M | Death risk: Arm 1, 1 (Ref); Arm 2, 1.60 (1.30–1.97) |

| Zhang 201350 | III IV |

(n=10): CCRT (cisplatin or carboplatin + RT up to 70Gy) | 3.52 Y | OS [2 Y]: 20% OS [5 Y]: 10% DSS [2 Y]: 26% DSS [5 Y]: 13% DFS [2 Y]: 13% |

Abbreviations: CCRT, concurrent chemoradiotherapy; CR, complete response; CT, chemotherapy; DC, distant control; DF, disease free rate; DFS, disease-free survival; DSS, disease specific survival; FU, fluorouracil; LC, local control; LRC, locoregional control; M, months; OR, overall response, OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival; RT, radiotherapy; Y, years.

Ten19,21,24–28,33,35,40 out of 1419,21,24–28,32,33,35,40–42,50 studies suggested that CCRT is a therapeutic option in people with unresectable oral cancer, so this treatment should be considered when surgery is not feasible. Among those studies in favor of CCRT, the 5-year OS and LRC rates ranged from 22%24 to 76%,35 and 49%24 to 90%,35 respectively. Overall, cisplatin remains as the main chemotherapeutic drug used in CCRT for unresectable oral cancer treatment; three studies19,21,24 used cisplatin plus RT up to 70 Gy, one study50 used cisplatin or carboplatin plus RT up to 70 Gy, while two studies27,32 used the S-1 (Taiho Pharmaceutical, Tokyo, Japan) plus RT. Biswas19 evaluated the use of cisplatin plus RT 70 Gy between younger (<40 years) and older (>40 years) adults, concluding that there is a similar overall response (63.5% vs 65.9%) between these groups; thus, CCRT can be used both for young as the elderly population.

According to the use of S-1, Murakami32 reported a 3-year OS and PFS of 37% and 27%, respectively, employing S-1 plus RT up to 70 Gy. Similarly, Hino27 assessed the use of S-1 plus RT 30 Gy and reported a median OS and PFS of 42.5 and 6.3 months, respectively, concluding that CCRT with S-1 is an effective treatment that can be safely conducted with minimal burden on patients. However, it is useful to highlight that that statement should be put into context because there are a small number of studies assessing this approach.

Regarding those studies that used 2–3 drug regimen CT, cisplatin was combined with docetaxel,26,40 carboplatin,41 gemcitabine,28 5-fluorouracil (5-FU),41 and paclitaxel.41 Hayashi26 evaluated the use of intra-arterial CT (total, 150 mg/m2 cisplatin and 60 mg/m2 docetaxel) with daily conventional RT (total, 60 Gy/30 fr) for 6 weeks. At a median follow-up of 40 months, the 3-year OS and LRC were 64.3% and 84.3%, respectively. Similarly, Sato40 evaluated the use of cisplatin combined with docetaxel plus RT up to 66 Gy, reporting a 3-year and 5-year OS and LRC of 52.9%, 33.0%, 50.9%, and 50.9%, respectively. Conversely, some studies41,50 have reported poor OS and LRC rates using CCRT in patients with unresectable oral cancer. To illustrate, Zhang50 reported a 5-year OS of just 10% using cisplatin or carboplatin plus RT up to 70 Gy. Similarly, Scher41 reported a 5-year OS of just 15% using cisplatin combined with carboplatin and 5-FU or paclitaxel plus RT up to 70 Gy. Likewise, Shia42 stated that although CCRT has benefits compared to non-treatment, there are no survival differences between the use of RT alone and CCRT.

Overall, CCRT could be considered as the main therapeutic option in unresectable oral squamous cell cancer because there is scientific evidence supporting its use. However, many factors should be taken into account in order to improve the clinical outcomes of these patients, who often are considered beyond cure.

Induction Chemotherapy Followed by Chemoradiotherapy

Induction chemotherapy (ICT) refers to CT given before the definitive treatment, in this case, that treatment was chemoradiotherapy (CRT). Among the benefits of ICT are to shrink the tumor, decrease the chances of distant metastases, increase the chances of organ preservation, and improving the outcomes such as OS and PFS. Seven studies29,34,36–38,45,49 assessed this approach, three studies29,45,49 were clinical trials and the rest of studies34,36–38 employed observational designs. The number of participants by group varied from 1629 to 16734 people. Three studies34,37,38 only involved patients with stage IV oral cancer, three studies29,45,49 recruited patients with clinical stages III/IV, and one study36 did not report it. All studies29,34,36–38,45,49 used the 2 or 3 drug regimens CT, and the main outcome reported was OS (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of Evidence on Induction Chemotherapy Followed by Chemoradiotherapy

| Author and Year | Clinical Stages | Interventions | Follow-Up | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Larizadeh 201229 | III IV |

Arm 1 (n=16): ICT with cisplatin + 5-FU followed by CCRT (cisplatin + RT) Arm 2 (n=41): ICT with cisplatin + 5-FU + docetaxel followed by CCRT (cisplatin + RT) |

32 M | OR: 68.4% OS [2 Y]: 38% OS [3 Y]: 26% OS [Mean]: Arm 1, 17.1 M; Arm 2, 27.9 |

| Patil 201434 | IV | (n=167): ICT with paclitaxel or docetaxel + cisplatin or carboplatin ± 5-FU followed by CCRT (cisplatin + RT up to 70 Gy) | 28 M | OS [2 Y]: 20% LRC [2 Y]: 15.0% |

| Rewadkar 201736 | NR | (n=25): ICT with bleomycin + methotrexate + cisplatin followed by CCRT (cisplatin + RT) | NR | CR: 84% |

| Rudresha 2017a37 | IV | (n=27): ICT with paclitaxel + carboplatin followed by CCRT | NR | OS [Median]: 11.8 M |

| Rudresha 2017b38 | IV | (n=44): ICT with docetaxel + cisplatin + 5-FU or paclitaxel + carboplatin followed by CCRT | NR | OS [Median]: 9.4 M |

| Takayama 201645 | III IV |

(n=33): ICT with 5-FU + nedaplatin + RT 36 Gy followed by CCRT (5-FU + nedaplatin + RT 39.6 Gy + cisplatin) | 43 M | OS [3 Y]: 87.0% PFS [3 Y]: 74.1% LC [3 Y]: 86.6% |

| Zaidi 202049 | III IV |

(n=35): ICT with docetaxel + cisplatin followed by CCRT (cisplatin + RT up to 60 Gy) | 4 M | OR: 78.8% CR: 10.5% PR: 68.4% |

Abbreviations: CCRT, concurrent chemoradiotherapy; CR, complete response; FU, fluorouracil; ICT, induction chemotherapy; LC, local control; LRC, locoregional control; M, months; NR, not reported; OR, overall response, OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival; PR, partial response, RT, radiotherapy; Y, years.

In a clinical trial by Larizadeh,29 patients with locoregionally advanced oral cancer were enrolled. ICT comprise 3 cycles of cisplatin and 5-FU with or without docetaxel. The overall response rate after ICT was 68.4%, and OS rates after 2 and 3 years were 38% and 26%, respectively. This author concluded that the outcome of patients with unresectable oral cancer is poor, so the benefits of the use of this therapeutic intervention for these patients are unclear. Likewise, Patil34 reported after 2 years an OS rate of 20% and an LRC of 15.0% for patients who underwent ICT with multiple drugs (paclitaxel or docetaxel plus cisplatin or carboplatin with or without 5-FU) followed by CCRT (cisplatin plus RT up to 70 Gy).

In terms of CR, two studies36,49 reported this outcome. Rewadkar36 reported a CR of 84% using bleomycin, methotrexate, and cisplatin on day 1 and repeated at an interval of 21 days during 3 cycles; then, participants were treated with CCRT using cisplatin infusion. That study stated that this approach can be superior to other treatments such as ICT plus RT alone. Conversely, Zaidi49 conducted an open-label, non-randomized trial and reported a complete response of just 10.5% using ICT with docetaxel plus cisplatin followed by cisplatin plus concurrent RT up to 60 Gy.

Takayama45 evaluated a complex approach using ICT followed by CCRT in 33 patients with stage III–IVB tongue cancer. Briefly, after two systemic CT courses and whole-neck irradiation using 36 Gy in 20 fractions, CCRT was used comprising proton beam therapy with weekly retrograde intra-arterial CT by continuous infusion of cisplatin with sodium thiosulfate. At a median follow-up of 43 months, the 3-year OS, PFS, local control (LC) rates were 87.0%, 74.1% and 86.6%, respectively. Overall, although ICT followed by CCRT can be used as a therapeutic option in unresectable oral cancer, its potential benefits still are controversial.

Induction Chemotherapy Followed by Radiotherapy

Four studies18,36–38 assessed this approach, one of them was an RCT,18 and the others were retrospective cohort studies,36–38 the number of participants by intervention group varied from 837 to 9918 people. Two studies37,38 included patients with clinical stage IV oral cancer, while two studies18,36 did not report it. All studies18,36–38 used the 2 or 3 drug regimen involving chemotherapeutic drugs, such as cisplatin, carboplatin, 5-FU, bleomycin, polyplatilene, methotrexate, paclitaxel, and docetaxel. The main outcome was OS, which was evaluated in three studies18,37,38 (Table 3).

Table 3.

Summary of Evidence on Induction Chemotherapy Followed by Radiotherapy

| Author and Year | Clinical Stages | Interventions | Follow-Up | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bazyka 201918 | NR | Arm 1 (n=99): ICT with cisplatin + 1.5-FU followed by RT up to 70 Gy Arm 2 (n=43): ICT with polyplatilene + 5-FU followed by RT up to 70 Gy |

NR | OS [36 M]: Arm 1, 29%*; Arm 2, 58%* |

| Rewadkar 201736 | NR | (n=25): ICT with bleomycin + methotrexate + cisplatin followed by RT up to 70 Gy | NR | CR: 60% |

| Rudresha 2017a37 | IV | (n=8): ICT with paclitaxel + carboplatin followed by RT | NR | OS [Median]: 8.5 M |

| Rudresha 2017b38 | IV | (n=11): ICT with docetaxel + cisplatin + 5-FU or paclitaxel + carboplatin followed by RT | NR | OS [Median]: 7.3 M |

Note: *Data extracted from a figure.

Abbreviations: CR, complete response; FU, fluorouracil; ICT, induction chemotherapy; M, months; NR, not reported; OS, overall survival; RT, radiotherapy.

One RCT18 have examined the role the ICT followed by RT in patients with locally advanced oral cavity, suggesting in terms of OS, that the use of ICT with polyplatilene plus 5-FU followed by RT 70 Gy is better than using ICT with cisplatin plus 1,5-FU followed by RT 70 Gy (36 months OS= 58% vs 29%). Two observational studies37,38 reported only a median OS of 7.3 and 8.5 months for patients treated with ICT followed by RT, which suggests that other therapeutic options should be considered in order to improve the disease-related outcomes.

Radiotherapy with/without Chemotherapy

All studies assessing RT alone or RT with or without CT were included in this group. Overall, five studies22,23,42,43,50 assessed this approach, three studies42,43,50 assessed RT alone and two studies22,23 assessed RT with or without CT. There was an RCT,43 a clinical trial23 and three observational studies.22,42,50 The number of participants for each group ranged from 923 to 31522 people. All studies22,23,42,43,50 recruited patients with stage III/IV oral cancer (Table 4).

Table 4.

Summary of Evidence on Radiotherapy with/without Chemotherapy

| Author and Year | Clinical Stages | Interventions | Follow-Up | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chitapanarux 201722 | III IV |

(n=315): RT 60–70 Gy ± CT | 11 M | OS [5 Y]: 15.9% OS [10 Y]: 12.9% |

| Donato 201323 | III IV |

(n=9): RT up to 70 Gy ± CT | 24 M | OR: 77.8% OS [2 Y]: 55.6% DFS [2 Y]: 75% |

| Shia 202042 | III IV |

Arm 1 (n=237): RT Arm 2 (n=227): Non-treatment |

15 M | Death risk: Arm 1, 1.06 (0.87, 1.31); Arm 2, 1.60 (1.30, 1.97) |

| Singh 201343 | III IV |

(n=30): RT 70 Gy | 20 M | CR: 33% |

| Zhang 201350 | III IV |

(n=28): RT up to 80Gy | 3.52 Y | OS [2 Y]: 18% OS [5 Y]: 10% DSS [2 Y]: 21% DSS [5 Y]: 21% DFS [2 Y]: 21% DFS [5 Y]: 21% |

Abbreviations: CR, complete response; CT, chemotherapy; DFS, disease-free survival; DSS, disease specific survival; M, months; OR, overall response, OS, overall survival; RT, radiotherapy; Y, years.

Among the studies assessing RT alone, one study50 reported a 2-year and 5-year OS of just 18% and 10%, respectively. One study43 reported a CR of 33%, whereas another study42 reported that the death risk for those receiving non-treatment was approximately 60% higher than those receiving RT alone. Among those evaluating the use of RT with or without CT, Donato23 reported a 2-year OS and DFS of 55.6% and 75%, respectively. Conversely, Chitapanarux22 reported a 5-year OS of just 15.9%. Overall, there is no strong evidence to support this approach to treat patients suffering from unresectable oral cancer.

Radiotherapy with or without Chemotherapy Followed by Brachytherapy

Three studies39,44,46 focused on the use of external beam RT (EBRT) with or without concurrent CT followed by brachytherapy (BT), two of them were clinical trials44,46 and one was a retrospective cohort study.39 The number of participants for each intervention group varied from 2439 to 6044 people. One study39 included patients with clinical stage III/IV oral cancer, one study46 only included patients with stage III oral cancer, and another study44 also included other clinical stages. The main outcomes assessed were OS, LRC, and CSS, which were evaluated in two39,44 out of three39,44,46 studies (Table 5).

Table 5.

Summary of Evidence on Radiotherapy with or without Chemotherapy Followed by Brachytherapy

| Author and Year | Clinical Stages | Interventions | Follow-Up | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Santos 201739 | III IV |

(n=24): EBRT up to 60 Gy + CT followed by HDR-BT | 44 M | OS [3 Y]: 68% OS [4 Y]: 68% CSS [3 Y]: 75% CSS [4 Y]: 68% LC [3 Y]: 80% LC [4 Y]: 80% LRC [3 Y]: 84% LRC [4 Y]: 76% DFS [3 Y]: 62% DFS [4 Y]: 48% |

| Takácsi-Nagy 201344 | I II III IV |

(n=60): EBRT up to 70 Gy ± CT with cisplatin followed by HDR-BT up to 30 Gy | 121 M | OS [5Y]: 47% LRC [5Y]: 50% LC [5Y]: 57% CSS [5Y]: 61% |

| Vedasoundaram 202046 | III | (n=57): EBRT 50 Gy + CT with cisplatin followed by HDR-BT up to 21 Gy | 60 M | CR: 77.2% |

Abbreviations: CT, chemoradiotherapy; CR, complete response; CSS, cancer specific survival; DFS, disease-free survival; EBRT, external beam radiotherapy; HDR-BT, high dose rate brachytherapy; LC, local control; LRC, locoregional control; M, months; OS, overall survival; RT, radiotherapy; Y, years.

In a nonrandomized clinical trial by Takácsi-Nagy,44 a high-dose-rate (HDR) BT boost with a mean dose of 17 Gy was delivered after 50–70 Gy locoregional EBRT. Moreover, around 30% of participants also received concurrent CT with cisplatin, reporting that the 5-year rate of LC, LRC, OS, and CSS was 57%, 50%, 47%, and 61%, respectively. Furthermore, OS was significantly better in patients receiving concurrent CT (69% vs 39%; p=0.005). Santos39 assessed the use of EBRT up to 60 Gy plus concurrent CT followed by HDR-BT up to 24 Gy with a median follow-up of 44 months, reporting that the 4-year OS and LRC rate was 68% and 80%, respectively. Similarly, Vedasoundaram46 assessed the use of EBRT 50 Gy plus CT with cisplatin followed by HDR-BT 21 Gy and reported a CR of 77.2%. Overall, this approach seems to be effective to treat patients with unresectable oral cancer, but more research about it is needed.

Chemotherapy

Two studies31,47 evaluated the use of CT, one of them was a controlled clinical trial,47 and another was an observational retrospective study.31 One study47 included 21 participants in the intervention group, whereas the other study31 included just 8 people in the intervention group. All two studies31,47 focused on patients with clinical stage III/IV oral cancer.

Wu47 aimed to assess the efficacy of intra-arterial infusion CT for patients with locally advanced oral cancer. Patients received continuously an infusion of methotrexate (50 mg/day) into the external carotid artery for 8 days, followed by a weekly intra-arterial bolus of 25 mg methotrexate for 10 weeks. Overall, CR and the partial response rate were 62% and 33%, respectively. At a median follow-up of 69 months, the 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year OS rates were 80%, 71%, and 64%, respectively. Similarly, Meng31 evaluated the use of the docetaxel-cisplatin-FU regimen, showing a response rate of 37.5% and a disease control rate of 62.5%. However, few studies are assessing the use of CT alone for unresectable oral cancer, so its effectiveness should be determined.

Targeted Therapy, Immunotherapy, and Gene Therapy

Six studies20,21,30,31,43,48 were included in this group, four20,31,43,48 of them assessed therapeutic options for unresectable oral cancer including at least a drug considered as targeted therapy, one study21 assessed the use of immunotherapy plus ICT followed by CRT, and one study30 evaluated the use of gene therapy plus CT. There were three RCTs21,30,43 and three clinical trials.20,31,48 The number of participants for each intervention group varied from 931 to 4320 people. Two studies20,48 only focused on patients with clinical stage IV oral cancer, whereas four studies21,30,31,43 focused on patients with stages III/IV. The main outcome assessed was OS, which was assessed in three20,30,48 out of six20,21,30,31,43,48 studies (Table 6).

Table 6.

Summary of Evidence on Targeted Therapy, Immunotherapy and Gene Therapy

| Author and Year | Clinical Stages | Interventions | Follow-Up | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chang 201720 | IV | (n=43): cetuximab + docetaxel + cisplatin + 5-FU followed by bio-CRT with cisplatin and cetuximab | 15 M | OS [1 Y]: 68% PFS [1 Y]: 43% |

| Chhatui 201521 | III IV |

(n=25): ICT with cisplatin + 5-FU + interferon α-2b followed by CRT (cisplatin + RT 70 Gy) | 15 M | CR: 64% DFS: 87% |

| Li 201430 | III IV |

Arm 1 (n=35): rAd-p53 + CT Arm 2 (n = 33): rAd-p53 + placebo CT Arm 3 (n = 31): placebo rAd-p53 + CT |

36 M | CR: Arm 1, 48.5%; Arm 2, 16.7%, Arm 3, 17.2% |

| Meng 201431 | III IV |

(n=9): nimotuzumab + docetaxel + cisplatin + 5-FU | NR | RR: 89.9% DCR: 100% |

| Singh 201343 | III IV |

(n=30): gefitinib + RT 70 Gy | 20 M | CR: 60% |

| Yen 201948 | IV | (n=39): cetuximab + paclitaxel + cisplatin followed by BioRT (cetuximab + RT 70Gy) | 6.5 Y | OR: 70.2% CR: 8.5% PR: 61.7% PFS [Median]= 10.3 M OS [Median]= 15.2 M |

Abbreviations: CR, complete response; CRT, chemoradiotherapy; CT, chemotherapy; DCR, disease control rate; DFS, disease-free survival; FU, fluorouracil; ICT, induction chemotherapy; M, months; NR, not reported; OR, overall response; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival; PR, partial response; rAd-p53, recombinant adenoviral p53; RR, response rate; RT, radiotherapy; Y, years.

Two studies20,48 included the use of cetuximab in their treatment regimen. An open-label Phase II trial by Chang20 evaluated a regimen comprising cetuximab-docetaxel-cisplatin, and 5-FU followed by bio-CRT with cisplatin and cetuximab; the 1-year OS and PFS were 68% and 43%, respectively. This author stated that this approach is an effective and tolerable ICT regimen for inoperable oral cancer. Likewise, a phase II clinical trial by Yen48 assessed the neoadjuvant cetuximab plus paclitaxel, and cisplatin followed by cetuximab-based RT 70 Gy; and reported an overall response rate of 70.2% and a median OS of 15.2 months. Another study31 tested the use of nimotuzumab combined with the docetaxel-cisplatin-FU regimen, reporting a response rate of 89.9% and disease control rates of 100%, suggesting that this regimen is effective and safe in the treatment of advanced oral squamous cell carcinoma. Similarly, Singh43 assessed the use of gefitinib plus RT 70 Gy, showing a CR of 60% and suggesting that this intervention has better outcomes compared to RT alone.

Chhatui21 conducted an RCT assessing the ICT with cisplatin plus 5-FU regimen for three cycles and interferon alpha 2b, which was subcutaneously given at the dose of 3MU, biweekly for three weeks. Then, the participants received CRT with cisplatin 30 mg/m2/week and RT 70 Gy. This author reported a CR and DFS of 64% and 87%, respectively; concluding that this approach may produce superior outcomes. However, it is useful to highlight that there is limited evidence about it. Thus, the effectiveness of treatments involving immunotherapy for unresectable oral cancer is uncertain.

A Phase III RCT30 aimed to assess a combination of recombinant adenoviral p53 (rAd-p53) gene therapy and intra-arterial delivery of CT agents for the treatment of oral squamous cell carcinoma. In that study, 99 participants were recruited and randomly divided into three arms: arm I (n= 35; intra-arterial infusion of rAd-p53 plus CT), arm II (n = 33; intra-arterial infusion of rAd-p53 plus placebo CT), and arm III (n = 31; intra-arterial infusion of placebo rAd-p53 plus CT). The 5-year OS rate was 48.5%, 30% and 22.5% for arm 1, arm 2 and arm 3, respectively. These findings suggest that the use of rAd-p53 gene therapy plus CT can improve the clinical outcomes for people suffering from unresectable oral cancer, but these results should be considered with caution since there is lacking evidence about the effectiveness of these treatment options.

Discussion

In order to describe the main therapeutic options in unresectable oral squamous cell carcinoma, we conducted an evidence-based comprehensive analysis. This review may be the first one focused on unresectable oral cancer since we did not find any previous report. Moreover, other reviews focused on oral cancer treatment usually based their conclusions on studies including a large proportion of patients with other types of cancers such as head and neck tumors, and just a small proportion of people suffering from oral cancer.

Our findings suggest that the optimal treatment of patients with unresectable oral cancer is challenging; thus, there is a sprinkling of studies proposing a range of therapeutic options, such as RT, CT, CCRT, immunotherapy, targeted therapy plus CT or RT, and gene therapy plus CT. However, it is useful to highlight that the scientific evidence supporting many of these approaches is limited. Overall, the use of CCRT, and ICT followed by CRT have shown good clinical results such as improvement of overall response,49 OS and LCR rate.35 In this sense, most studies19,24–28,33,35,40 supported the use of the CCRT as a therapeutic option in people with unresectable oral cancer. Likewise, some studies36,45,49 indicated the benefits of the use of ICT followed by CRT for the treatment of these patients. Consequently, these therapeutic options can be useful when surgery is not feasible.

However, some factors should be considered to choose the optimal therapeutic options in unresectable oral squamous cell carcinoma. Firstly, the treatment side effects; to illustrate, Chhatui21 reported that those patients receiving ICT had more toxicities and treatment interruptions; among its side effects were skin reactions, mucositis, anemia, leukopenia, nausea, and vomiting. Similarly, Sato40 reported that among the adverse effects of using CCRT are stomatitis, dermatitis, anemia, and liver dysfunction. Secondly, individual patient factors and their possible role on the treatment effect should be taken into account. Some reports suggest that differences in lifestyle, living environment, and race, may affect the therapy effectiveness in oncology.51–53 For example, diet management improves OS and other clinical outcomes in people with head and neck cancers.51 Likewise, after oral cancer treatment, black people usually have poorer OS rates than whites.52 Moreover, changes in habits such as quitting smoking, alcohol drinking, and betel nut could have a considerable impact on therapeutic interventions, especially in patients with unresectable oral cancer.53 However, we highlight that few studies20,22,24,26,28,34–38,41–43,46 in this review reported those factors, and only one study22 analyzed the influence of them on treatment response. Finally, the reasons given to determine whether the tumor was unresectable should be considered; since unresectable oral neoplasms due to technical reasons could have different treatment responses compared with those unresectable tumors due to patients’ comorbidities or poor general health status.13 Overall, any treatment should be judged and discussed with a multidisciplinary team, evaluating its risks and benefits.

Our findings may be comparable with the results reported by Alzahrani,13 who narratively reviewed the evidence on the optimal care for people suffering from locally advanced oral cancer, concluding that when surgery is not recommended, these patients can be treated by curative CRT. In addition, this author suggested the use of ICT before surgery or CRT for unresectable oral cancers. However, these results should be taken with caution since there are some differences between these two reviews; firstly, most studies included in the Alzahrani13 review had focused on head and neck cancers, while our review included studies exclusively focused on oral cancer, or those studies showing results separately for this oral disease. Secondly, since our main goal was to describe the therapeutic options when surgery is not feasible, we did not consider interventions before or after surgical treatments, which intent to become an unresectable lesion to an operable one or to provide adjuvant therapy.54,55

Similarly, our findings also should be put into context. So initially, as it has been previously reported, there is limited evidence of therapeutic options in unresectable oral cancer.14 Secondly, most studies19,22–26,28,29,32–42,44,46,47,50 included in this review had an observational design and many of them conducted a retrospective analysis,22,24–26,28,34,36–42,47,50 therefore their conclusions may be biased since observational studies are not the best design to assess the effectiveness of treatments; so high-quality RCTs must be conducted, which have major relevance for clinical practice.56 Finally, the methodological quality of some studies26,27,29,31,32,34–38,40 was suboptimal using the JBI’s tool. Thus, any therapeutic option in this review should be analyzed and interpreted considering the limitations of each selected study.

The main practical implications of this review are related to helping practitioners and patients in the decision-making process. Given knowing the available evidence and its quality is so important to provide evidence-based health care, the findings of this review can be useful to improve the management of oral cavity cancer. In this sense, those interventions identified as beneficial could be considered into dental clinical practice to provide evidence-based dentistry. Similarly, those treatments that have been used for decades without evidence’ support, and have no potential benefits, should not be considered as options to treat unresectable mouth cancers. However, it is useful to highlight that this review does not pretend to replace any clinical practice guideline. Thus, any treatment should be adapted for each patient considering the clinical expertise, the available resources, their risk/benefit ratio, and other contextual aspects.57

Another potential implication of this review is related to conduct high-quality research on those interventions with lacking evidence such as gene therapy, which had only one selected study.30 In this sense, cancer gene therapy is considered a novel approach that may significantly improve clinical outcomes such as OS of patients suffering from cancers.58,59 Likewise, it is useful to mention that more research on targeted therapy is needed. All these new therapeutic approaches have been developed on a better understanding of molecular mechanisms involved in the cancer disease; thus, they are more selective against tumor cells, which leads to decrease in side effects. However, their clinical applicability to treat head and neck cancers still is unclear.60

Some limitations in this review should be mentioned such as the language barrier, due to all evidence found was published in English, which eliminated the inclusion of available evidence published in any other language. However, it is useful to highlight that no restrictions about languages were performed; moreover, since most evidence is published in English, it is more likely that evidence meeting the eligibility criteria is published in this language.

Among the strengths of this review, we highlight that all methods were described in a protocol in advance. Moreover, a sensitive search strategy was carried out, so it is unlikely that any relevant evidence was missed. Similarly, at least two reviewers independently conducted the whole processes of selection, methodological quality assessment, and data extraction. All these processes provide reasonable confidence in our results.

Conclusion

There is lacking evidence about the benefits of some therapeutic options for unresectable oral squamous cell carcinoma. Overall, these patients can be treated using a multimodal approach, such as CCRT or ICT followed by CRT, which have shown good clinical outcomes. However, other therapeutic options could be considered depending on the assessment of risk/benefits, tumor extension and patient values and preferences. In all cases, any treatment should be adapted for each patient considering the clinical expertise, the available resources, and other contextual aspects.

Funding Statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data Sharing Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Author Contributions

Conceived the study: MM and LTA. Designed the study: MM, LTA and CLA. Analyzed the data: MM, LTA, CLA. Wrote the first draft of the manuscript: MM and LTA. Contributed to the writing of the manuscript: MM, LTA, CLA. All authors made substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; took part in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; agreed to submit to the current journal; gave final approval of the version to be published; and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest for this work.

References

- 1.Daly B, Batchelor P, Treasure E. Introduction to the principles of public health. In: Essential Dental Public Health. Vol. 2. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2013:1–48. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer Statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67(1):7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(6):394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Warnakulasuriya S. Global epidemiology of oral and oropharyngeal cancer. Oral Oncol. 2009;45(4–5):309–316. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2008.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kyrgias G, Hajiioannou J, Tolia M, et al. Intraoperative radiation therapy (IORT) in head and neck cancer: a systematic review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95(50):e5035. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000005035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koch L, Jansen L, Brenner H, Arndt V. Fear of recurrence and disease progression in long-term (≥ 5 years) cancer survivors–a systematic review of quantitative studies. Psycho-Oncol. 2013;22(1):1–11. doi: 10.1002/pon.3022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dzioba A, Aalto D, Papadopoulos-Nydam G, et al. Functional and quality of life outcomes after partial glossectomy: a multi-institutional longitudinal study of the head and neck research network. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surgery. 2017;46(1):56. doi: 10.1186/s40463-017-0234-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wong T, Wiesenfeld D. Oral cancer. Aust Dent J. 2018;63(Suppl 1):S91–s99. doi: 10.1111/adj.12594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hartner L. Chemotherapy for oral cancer. Dent Clin North Am. 2018;62(1):87–97. doi: 10.1016/j.cden.2017.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bulsara VM, Worthington HV, Glenny A-M, Clarkson JE, Conway DI, Macluskey M. Interventions for the treatment of oral and oropharyngeal cancers: surgical treatment. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;12(12):CD006205–CD006205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wolff KD, Follmann M, Nast A. The diagnosis and treatment of oral cavity cancer. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2012;109(48):829–835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grégoire V, Leroy R, Heus P, et al. Oral cavity cancer: diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Good clinical practice (GCP) Brussels: Belgian health care knowledge centre (KCE). KCE Rep. 2014:227. Available from: https://kce.fgov.be/sites/default/files/atoms/files/KCE_227Cs_oral%20cavity%20cancer_Synthesis_2.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alzahrani R, Obaid A, Al-Hakami H, et al. Locally advanced oral cavity cancers: what is the optimal care? Cancer Control. 2020;27(1):1073274820920727. doi: 10.1177/1073274820920727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Madera M, Franco J, Ballesteros M, Solà I, Urrútia G, Bonfill X. Evidence mapping and quality assessment of systematic reviews on therapeutic interventions for oral cancer. Cancer Manag Res. 2019;11:117–130. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S186700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Rayyan-a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2016;5(1):210. doi: 10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moola S, Munn Z, Tufanaru C, et al. Chapter 7: systematic reviews of etiology and risk. In: Aromataris E, Munn Z, editors. JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. 2020. Available from: https://synthesismanual.jbi.global. Accessed August16, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bazyka D, Vorobyov M, Kechyn I, Vorobyov O, Shmykova O. Radiothermometric personalisation of chemo- and radiotherapy for patients with advanced (III, IVa and IVb) stages malignant lesions of oral cavity, throat and epiglottis. Problemy Radiatsiinoi Medytsyny Ta Radiobiolohii. 2019;24:296–311. doi: 10.33145/2304-8336-2019-24-296-311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Biswas R, Halder A, Ghosh A, Ghosh SK. A comparative study of treatment outcome in younger and older patients with locally advanced oral cavity and oropharyngeal cancers treated by chemoradiation. South Asian j Cancer. 2019;8(1):47–51. doi: 10.4103/sajc.sajc_7_18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chang PM, Lu HJ, Wang LW, et al. Effectiveness of incorporating cetuximab into docetaxel/cisplatin/fluorouracil induction chemotherapy and chemoradiotherapy for inoperable squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity: a phase II study. Head Neck. 2017;39(7):1333–1342. doi: 10.1002/hed.24766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chhatui B, Devleena RS, Maji T, Lahiri D, Biswas J. Immunomodulated anterior chemotherapy followed by concurrent chemoradiotherapy in locally advanced tongue cancer: an Institutional experience. Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol. 2015;36(1):43–48. doi: 10.4103/0971-5851.151782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chitapanarux I, Traisathit P, Komolmalai N, et al. Ten-year outcome of different treatment modalities for squamous cell carcinoma of oral cavity. Asian Pacific j Cancer Prevention. 2017;18(7):1919–1924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Donato V, Cianciulli M, Fouraki S, et al. Helical tomotherapy: an innovative radiotherapy technique for the treatment of locally advanced oropharynx and inoperable oral cavity carcinoma. Radiation Oncol. 2013;8:210. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-8-210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Elbers JBW, Al-Mamgani A, Paping D, et al. Definitive (chemo) radiotherapy is a curative alternative for standard of care in advanced stage squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity. Oral Oncol. 2017;75:163–168. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2017.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Foster CC, Melotek JM, Brisson RJ, et al. Definitive chemoradiation for locally-advanced oral cavity cancer: a 20-year experience. Oral Oncol. 2018;80:16–22. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2018.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hayashi Y, Osawa K, Nakakaji R, et al. Prognostic factors and treatment outcomes of advanced maxillary gingival squamous cell carcinoma treated by intra-arterial infusion chemotherapy concurrent with radiotherapy. Head Neck. 2019;41(6):1777–1784. doi: 10.1002/hed.25607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hino S, Hamakawa H, Miyamoto Y, et al. Effects of a concurrent chemoradiotherapy with S-1 for locally advanced oral cancer. Oncol Lett. 2011;2(5):839–843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Iqbal H, Jamshed A, Bhatti AB, et al. Five-year follow-up of concomitant accelerated hypofractionated radiation in advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the buccal mucosa: a retrospective cohort study. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:963574. doi: 10.1155/2015/963574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Larizadeh MH, Shabani M. Survival following non surgical treatments for oral cancer: a single institutional result. Asian Pacific j Cancer Prevention. 2012;13(8):4133–4136. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2012.13.8.4133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li Y, Li LJ, Wang LJ, et al. Selective intra-arterial infusion of rAd-p53 with chemotherapy for advanced oral cancer: a randomized clinical trial. BMC Med. 2014;12:16. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-12-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meng J, Gu QP, Meng QF, et al. Efficacy of nimotuzumab combined with docetaxel-cisplatin-fluorouracil regimen in treatment of advanced oral carcinoma. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2014;68(1):181–184. doi: 10.1007/s12013-013-9686-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Murakami R, Semba A, Kawahara K, et al. Concurrent chemoradiotherapy with S-1 in patients with stage III-IV oral squamous cell carcinoma: a retrospective analysis of nodal classification based on the neck node level. Mol Clin Oncol. 2017;7(1):140–144. doi: 10.3892/mco.2017.1276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oyama T, Hosokawa Y, Abe K, et al. Prognostic value of quantitative FDG-PET in the prediction of survival and local recurrence for patients with advanced oral cancer treated with superselective intra-arterial chemoradiotherapy. Oncol Lett. 2020;19(6):3775–3780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Patil VM, Prabhash K, Noronha V, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by surgery in very locally advanced technically unresectable oral cavity cancers. Oral Oncol. 2014;50(10):1000–1004. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2014.07.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pederson AW, Salama JK, Witt ME, et al. Concurrent chemotherapy and intensity-modulated radiotherapy for organ preservation of locoregionally advanced oral cavity cancer. Am J Clin Oncol. 2011;34(4):356–361. doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e3181e8420b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rewadkar MS, Mahobia VK. Impact of induction chemotherapy to concurrent chemoirradiation over radiotherapy alone in advanced oral cavity. Indian J Cancer. 2017;54(1):16–19. doi: 10.4103/ijc.IJC_166_17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rudresha AH, Chaudhuri T, Lakshmaiah KC, et al. Induction chemotherapy in technically unresectable locally advanced t4a oral cavity squamous cell cancers: experience from a regional cancer center of South India. Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol. 2017;38(4):490–494. doi: 10.4103/ijmpo.ijmpo_185_16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rudresha AH, Chaudhuri T, Lakshmaiah KC, et al. Induction chemotherapy in locally advanced T4b oral cavity squamous cell cancers: a regional cancer center experience. Indian J Cancer. 2017;54(1):35–38. doi: 10.4103/ijc.IJC_131_17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Santos MA, Guinot JL, Tortajada MI, et al. High-dose-rate interstitial brachytherapy boost in inoperable locally advanced tongue carcinoma. Brachytherapy. 2017;16(6):1213–1218. doi: 10.1016/j.brachy.2017.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sato K, Hayashi Y, Watanabe K, Yoshimi R, Hibi H. Concurrent chemoradiotherapy with intravenous cisplatin and docetaxel for advanced oral cancer. Nagoya J Med Sci. 2019;81(3):407–414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Scher ED, Romesser PB, Chen C, et al. Definitive chemoradiation for primary oral cavity carcinoma: a single institution experience. Oral Oncol. 2015;51(7):709–715. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2015.04.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shia BC, Qin L, Lin KC, et al. Outcomes for elderly patients aged 70 to 80 years or older with locally advanced oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma: a propensity score-matched, nationwide, oldest old patient-based cohort study. Cancers. 2020;12(2):258. doi: 10.3390/cancers12020258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Singh K, Dixit A, Prashad S, Saxena T, Shahoo D, Sharma D. A randomized trial comparing radiotherapy alone versus radiotherapy with gefitinib in locally advance oral cavity cancer. Clin Cancer Investigation J. 2013;2:29–33. doi: 10.4103/2278-0513.110768 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Takácsi-Nagy Z, Oberna F, Koltai P, et al. Long-term outcomes with high-dose-rate brachytherapy for the management of base of tongue cancer. Brachytherapy. 2013;12(6):535–541. doi: 10.1016/j.brachy.2013.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Takayama K, Nakamura T, Takada A, et al. Treatment results of alternating chemoradiotherapy followed by proton beam therapy boost combined with intra-arterial infusion chemotherapy for stage III-IVB tongue cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2016;142(3):659–667. doi: 10.1007/s00432-015-2069-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vedasoundaram P, Raghava KA, Periasamy K, et al. The effect of high dose rate interstitial implant on early and locally advanced oral cavity cancers: update and long-term follow-up study. Cureus. 2020;12(5):e7910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wu CF, Chang KP, Huang CJ, Chen CM, Chen CY, Steve Lin CL. Continuous intra-arterial chemotherapy for downstaging locally advanced oral commissure carcinoma. Head Neck. 2014;36(7):1027–1033. doi: 10.1002/hed.23408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yen CJ, Tsou HH, Hsieh CY, et al. Sequential therapy of neoadjuvant biochemotherapy with cetuximab, paclitaxel, and cisplatin followed by cetuximab-based concurrent bioradiotherapy in high-risk locally advanced oral squamous cell carcinoma: final analysis of a Phase 2 clinical trial. Head Neck. 2019;41(6):1703–1712. doi: 10.1002/hed.25640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zaidi SHM, Masood AI, Shah SIH, Hashemy I. Open label, non-randomized, interventional study to evaluate response rate after induction therapy with docetaxel and cisplatin in locally advanced squamous cell carcinoma of oral cavity. Gulf J Oncol. 2020;1(32):12–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang H, Dziegielewski PT, Biron VL, et al. Survival outcomes of patients with advanced oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma treated with multimodal therapy: a multi-institutional analysis. J Otolaryngol. 2013;42(1):30. doi: 10.1186/1916-0216-42-30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Müller-Richter U, Betz C, Hartmann S, Brands RC. Nutrition management for head and neck cancer patients improves clinical outcome and survival. Nutr Res. 2017;48:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2017.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tomar SL, Loree M, Logan H. Racial differences in oral and pharyngeal cancer treatment and survival in Florida. Cancer Causes Control. 2004;15(6):601–609. doi: 10.1023/B:CACO.0000036166.21056.f9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zakeri K, MacEwan I, Vazirnia A, et al. Race and competing mortality in advanced head and neck cancer. Oral Oncol. 2014;50(1):40–44. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2013.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shanti RM, O’Malley BW Jr. Surgical management of oral cancer. Dent Clin North Am. 2018;62(1):77–86. doi: 10.1016/j.cden.2017.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zanoni DK, Montero PH, Migliacci JC, et al. Survival outcomes after treatment of cancer of the oral cavity (1985–2015). Oral Oncol. 2019;90:115–121. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2019.02.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sylvester RJ, Canfield SE, Lam TB, et al. Conflict of evidence: resolving discrepancies when findings from randomized controlled trials and meta-analyses disagree. Eur Urol. 2017;71(5):811–819. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2016.11.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Alonso-Coello P, Schunemann HJ, Moberg J, et al. GRADE evidence to decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 1: introduction. BMJ. 2016;353:i2016. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sun W, Shi Q, Zhang H, et al. Advances in the techniques and methodologies of cancer gene therapy. Discov Med. 2019;27(146):45–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Farmer ZL, Kim ES, Carrizosa DR. Gene therapy in head and neck cancer. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2019;31(1):117–124. doi: 10.1016/j.coms.2018.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Perrotti V, Caponio VCA, Mascitti M, et al. Therapeutic potential of antibody-drug conjugate-based therapy in head and neck cancer: a systematic review. Cancers. 2021;13:13. doi: 10.3390/cancers13133126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]