Abstract

Drying temperature (DT) of corn can influence its nutritional quality, but whether this is influenced by endosperm hardness is not clear. Two parallel experiments were conducted to investigate the effects of 2 yellow dent corn hybrids with average and hard kernel hardness, dried at 3 temperatures (35, 80, and 120°C), and 2 supplementation levels of an exogenous amylase (0, 133 g/ton of feed) on live performance, starch and protein digestibility, and energy utilization of Ross 708 male broilers. Twelve dietary treatments consisting of a 2 × 3 × 2 factorial arrangement were evaluated using 3-way ANOVA in a randomized complete block design. In Experiment 1, a total of 1,920 male-chicks were randomly allocated to 96 floor pens, whereas 480 day-old chicks were distributed among 96 cages for Experiment 2. At 40 d, interaction effects (P < 0.05) were detected on BWG, FCR, and flock uniformity. Supplementation with exogenous amylase resulted in heavier broilers, better FCR and flock uniformity, only in the diets based on corn dried at 35°C. Additionally, interaction effects were observed on FCR due to kernel hardness and DT (P < 0.01), kernel hardness and amylase supplementation (P < 0.001), and DT and amylase supplementation (P < 0.05). Exogenous amylase addition to the diets based on corn with an average hardness improved FCR up to 2 points (1.49 vs. 1.51 g:g) whereas there was no effect of amylase on FCR of broilers fed diets based on corn with hard endosperm. Total tract retention of starch was increased (P < 0.05) in broilers fed diets based on corn with average kernel hardness compared to hard kernel. Corn dried at 80 and 120°C had up to 1.21% points less starch total tract retention than the one dried at 35°C. Supplementing alpha-amylase resulted in beneficial effects for broiler live performance, energy utilization, and starch total tract digestibility results. Treatment effects on starch characteristics were explored. Corn endosperm hardness, DT and exogenous amylase can influence the live performance of broilers. However, these factors are not independent and so must be manipulated strategically to improve broiler performance.

Key words: corn kernel hardness, drying temperature, amylase supplementation, broiler chickens

INTRODUCTION

Corn (Zea mays) is the primary source of energy for domestic animal nutrition (Kljak et al., 2018) and main feed ingredient for poultry (IGC, 2018; USDA, 2021). Corn can be categorized into 5 general classes by kernel hardness, more appropriately termed vitreousness, meaning glassy (Watson, 1987; Williams et al., 2009; Kljak et al., 2011). These classes are, in order of decreasing vitreousness: flint, popcorn, flour, dent, and sweet (Ratnayake and Jackson, 2003). Most commercial maize used in feed is dent, which is a derivative of flint-floury crosses (Lasek et al., 2012; Kaczmarek et al., 2014a). It has been reported that corn kernel hardness could affect the live performance and nutrient utilization in broiler chickens and hens (Moore et al., 2008; O'Neill et al., 2012). However, the possible interaction effects with grain drying temperature and amylase supplementation on nutrient utilization have been vaguely investigated. An early study (Kaczmarek et al., 2014b) suggested that kernel hardness and drying temperature affected protein digestibility of broilers at 35 d. However, live performance was not influenced by this interaction when dietary treatments were offered in mash form.

Worldwide, corn grain is often harvested with moisture contents between 26 and 36% or even higher depending on weather conditions and is dried until moisture reaches about 12 to 15% for subsequent storage and use in animal feeds (Odjo et al., 2015). The drying process can occur on the field but is commonly performed by artificial means. Grain drying temperatures used in different countries could reach more than 100°C (Larbier et al., 1971; Kaczmarek et al., 2014a; Li et al., 2014) to reduce the energy consumption of grain dryers (Barrier-Guillot et al., 1993). Nevertheless, the use of high temperatures to dry the grain may induce the formation of new chemical bonds within and between substrates that are resistant to digestive enzymes (Larbier et al., 1971; Iji et al., 2003; Bhuiyan et al., 2010). These changes include increments in surface area to mass ratio, increase of protein cross-linking on starch granules surface after grain fractionation, modification of the crystallinity of starch granules, and probably unfolding of amylose and amylopectin clusters. These changes of morphological and structural parameters are probably responsible for differences in enzymatic in vitro and in vivo digestibility and fermentation of starch residues (Malumba et al., 2008), potentially causing negative impacts on nutrient digestibility and live performance (Martins et al., 2001; Iji et al., 2003; Cowieson, 2005; Huart et al., 2018). In addition, high drying temperatures may promote the occurrence of Maillard reactions (Žilić et al., 2013), leading to poor digestibility of some essential amino acids, especially lysine (Wall and Donaldson, 1975; Rutherfurd et al., 1997; Odjo et al., 2015), cysteine, tyrosine, and threonine (Kaczmarek et al., 2014a). Endosperm hardness may play an important role in animal responses due to variations in starch structure, the content of resistant and damaged starch, amylose and amylopectin ratio, and the physical fragmentation properties during grinding that can influence feed traits, gut development and morphology, and ingestion behavior (Kaczmarek et al., 2014a; Córdova-Noboa et al., 2021; Ma et al., 2020).

Starch is quantitatively the main energy-yielding source for poultry, representing approximately 690 g/kg of corn composition (Svihus, 2014). Even though chickens have been adapted to starch-based diets, early growth in the chick could be limited during the post-hatching period since pancreatic amylase secretion from the immature pancreas might retard intestinal starch digestion (Zanella et al., 1999; Stefanello et al., 2015). Moreover, the fast feed intake in modern broilers of 4 to 5 wk of age may produce a physiological limitation to starch digestion (Sklan and Noy, 2003), as feed passage rate may be too rapid for optimal digestibility of nutrients (Croom et al., 1999; Svihus et al., 2002). The use of exogenous enzyme blends, including xylanase, amylase, and protease, has been reported to improve broilers' energy utilization and live performance in corn-based diets (Cowieson et al., 2005; Cowieson, 2010; Stefanello et al., 2015). Amylase has been supplemented to diets containing phytase, which is currently an ubiquitous enzyme; however, some studies could not detect improvements in live performance or starch digestibility (Kaczmarek et al., 2014b; Stefanello et al., 2015). Perhaps, much of the failures of the poultry industry to adopt carbohydrase enzymes in corn-based diets has to do with intrinsic factors of corn that are not yet well understood (Klein, 2013). Information related to dietary amylase supplementation and its effects on broiler chickens fed corn dried at high temperature is scarce. How these factors influence animal performance depending on endosperm hardness is still not clear (Lasek et al., 2012; Kaczmarek et al., 2014a).

Despite the reported differences in the nutritional value of corn subjected to different drying temperatures, limited data is published regarding a possible interaction effect between kernel hardness and drying temperature. Likewise, data investigating the interactive effects of these parameters with amylase supplementation on broiler growth performance is scarce. Therefore, the objective of the current project was to explore the interactive effects of kernel hardness, drying temperature, and amylase supplementation on the endosperm and starch characteristics, the nutritional value of yellow dent corn for broiler chickens and the final impact on live performance.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

All procedures involving broiler chicken used in the present experiment were approved by the North Carolina State University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Grain Production and Drying Management

Seeds from 2 yellow dent corn hybrids (DEKALB 68-05 and DEKALB 65-20) differing in kernel hardness (average and hard, respectively) were obtained from a commercial supplier and planted the same day in 2 fields within a distance of less than a mile. Vitreousness content before drying the grain was 66.86% for corn with average endosperm hardness, while for the harder kernel hybrid was 68.84% (P < 0.05) with a SEM ± 0.52%. Corn vitreousness and the total salt-protein solubility index were evaluated by near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS DS2500, FOSS, Denmark) in 5 random samples for both hybrids using the calibration model developed by AB Vista Feed Ingredients (Plantation, FL) before and after drying (Table 1). The same agricultural practices, such as seed disinfection, herbicide application, fertilization, and harvesting methods, were applied in both fields to reduce variability due to these parameters. After 125 and 135 d of plantation, both hybrids were harvested and de-grained mechanically with initial moistures of 19.89 and 23.19% SEM = 0.42 (P < 0.001) for average and hard kernel hardness, respectively and were split into 3 batches each. The drying process was conducted as described by Córdova-Noboa et al. (2021). For both hybrids, the first batch was dried at 35°C, the second at 80°C, and the last at 120°C in the same industrial dryer (GSI, single-fan, natural gas, open flame, forced-air dryer, Competitor Series Dryers, model competitor 112, Newton, IL). The required time to batch-dry the corn to the target moisture content of 13% at each temperature was approximately 4 to 5 h for 120°C, 7 to 8 h for 80°C, and 9 to 10 h for 35°C.

Table 1.

Effect of graded drying temperatures on endosperm vitreousness and starch characteristics of two corn varieties with differences in kernel hardness.

| Kernel hardness1 | Drying temperature (°C) | Endospermvitreousness2 | Protein solubility index2 | Corn starch characteristics3 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total starch | Amylose content | Gelatinized starch | Resistant starch | Damaged starch4 | ||||

| ––––––––––––– %––––––––––––– |

||||||||

| Average | 61.98b | 23.67 | 68.17a | 23.81a | 13.91 | 4.84a | 3.75a | |

| Hard | 63.31a | 23.22 | 67.10b | 22.67b | 15.00 | 4.40b | 2.36b | |

| SEM | 0.07 | 0.20 | 0.07 | 0.27 | 0.75 | 0.14 | 0.12 | |

| 35 | 62.87a | 24.06a | 67.09b | 21.49b | 13.81 | 4.49 | 3.20a | |

| 80 | 62.49b | 23.16b | 67.86a | 22.72b | 14.53 | 4.64 | 3.38a | |

| 120 | 62.57b | 23.13b | 67.95a | 25.51a | 15.02 | 4.72 | 2.59b | |

| SEM | 0.08 | 0.25 | 0.09 | 0.33 | 0.92 | 0.17 | 0.15 | |

| Average | 35 | 63.06b | 24.65 | 67.54b | 21.71c | 13.72 | 4.56 | 3.35bc |

| 80 | 60.75d | 23.41 | 67.84b | 25.43ab | 13.41 | 4.82 | 4.07a | |

| 120 | 62.13c | 22.97 | 69.12a | 24.28b | 14.60 | 5.14 | 3.85ab | |

| Hard | 35 | 62.68b | 23.47 | 66.64c | 21.28c | 13.90 | 4.42 | 3.04cd |

| 80 | 64.23a | 22.92 | 67.87b | 20.01c | 15.65 | 4.47 | 2.69d | |

| 120 | 63.01b | 23.28 | 66.79c | 26.73a | 15.45 | 4.31 | 1.34e | |

| SEM | 0.12 | 0.35 | 0.12 | 0.47 | 1.30 | 0.24 | 0.21 | |

| Source of variation | ––––––––––––– P-value ––––––––––––– | |||||||

| Kernel hardness | <0.001 | 0.130 | <0.001 | 0.012 | 0.344 | 0.080 | <0.001 | |

| Drying T | 0.007 | 0.022 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.661 | 0.677 | 0.013 | |

| Hardness × Drying T | <0.001 | 0.130 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.731 | 0.413 | 0.002 | |

Means in columns followed by different superscript letters are statistically different (P < 0.05) by Tukey's test.

Average (DEKALB 68-05) and hard kernel corn (DEKALB 65-20).

Measured with NIRS (DS2500, FOSS, Denmark) using AB Vista calibration model, n = 5.

Assessed using Megazyme kits Total Starch (amyloglucosidase/α-amylase method), Amylose/Amylopectin, Resistant Starch, and Starch Damage assay procedures following manufacturer's recommendations (Megazyme Inc., Chicago, IL).Gelatinized starch was conducted based on AACC 76-11.01/AOAC 979.10 method., n = 3.

Values are means of 6 replications per treatment.

Treatments and Experimental Design

Two yellow dent corn hybrids varying in kernel hardness and dried at 35, 80, and 120°C (until reaching moisture content of 13%), and subsequently 2 inclusion levels of an exogenous amylase (0, 133 g/ton) were used to obtain a total of 12 dietary treatments with 8 replications each for the 2 experiments and lab analyses. A randomized complete block design with a 2 × 3 × 2 factorial arrangement of treatments was used to determine the effects on live performance, nutrient digestibility, and tract retention of broiler chickens throughout both parallel studies.

Experimental starter, grower, and finisher diets (Table 2) were formulated to meet or exceed the suggested nutrient levels for Ross 708 broilers (Aviagen, 2019). Diets for each treatment were sourced from a common basal diet to reduce variation due to ingredient composition between batches. The basal diet contained all other ingredients but corn and amylase. The basal diets contained 200 g/ton of phytase as Ronozyme HiPhos GT to supply 1,000 phytase units (FYT). For the digestibility evaluation, 0.3% titanium dioxide as an inert marker was added to the starter basal diet only. Subsequently, 6 groups were created to include corn from each one of the 6 treatments resulting from the combination of kernel hardness and drying temperature. Each of these 6 groups was split out to add either 133 g/ton of alpha-amylase as Ronozyme HiStarch CT (Novozymes A/S, Bagsvaerd, Denmark) to supply 80 kilo-Novo alpha-amylase units (KNU) or sand. Finally, experimental diets were mixed and pelletized.

Table 2.

Ingredient and nutrient composition (calculated and analyzed) of starter, grower, and finisher basal diets for Ross-708 male broilers.

| Starter1 |

Grower |

Finisher |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ingredient | (1–14 d) | (15–28 d) | (29–40 d) | ||||||

| ––––––––––––– (%) ––––––––––––– | |||||||||

| Corn2 | 50.90 | 59.82 | 63.53 | ||||||

| Soybean meal, 46% | 34.50 | 29.75 | 26.20 | ||||||

| Corn DDGS | 5.75 | 2.00 | 2.00 | ||||||

| Poultry fat | 4.24 | 4.66 | 5.03 | ||||||

| Limestone fine | 1.42 | 1.14 | 1.05 | ||||||

| Dicalcium phosphate, 18.5% | 1.05 | 0.96 | 0.66 | ||||||

| DL- Methionine, 99% | 0.35 | 0.30 | 0.27 | ||||||

| Titanium dioxide3 | 0.30 | - | - | ||||||

| Sand or Amylase4 | 0.0133 | 0.0133 | 0.0133 | ||||||

| Salt (NaCl) | 0.30 | 0.33 | 0.28 | ||||||

| L-Lysine-HCl, 78.8% | 0.29 | 0.23 | 0.21 | ||||||

| Sodium bicarbonate | 0.21 | 0.15 | 0.18 | ||||||

| Mineral5 and Vitamin6 premixes | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.30 | ||||||

| Choline chloride, 60% | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.18 | ||||||

| L-Threonine, 98% | 0.15 | 0.10 | 0.08 | ||||||

| Coccidiostat7 | 0.05 | 0.05 | - | ||||||

| Phytase8 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | ||||||

| Total | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | ||||||

| Formulated nutrient composition | |||||||||

| ME, kcal/kg | 3,000 | 3,100 | 3,170 | ||||||

| CP, % | 22.30 | 19.72 | 18.30 | ||||||

| Calcium, % | 0.96 | 0.88 | 0.78 | ||||||

| Non-phytate phosphorous, % | 0.48 | 0.44 | 0.39 | ||||||

| Digestible lysine, % | 1.28 | 1.09 | 0.99 | ||||||

| Digestible total sulfur amino acids, % | 0.95 | 0.84 | 0.78 | ||||||

| Digestible threonine, % | 0.86 | 0.73 | 0.66 | ||||||

| Digestible tryptophan, % | 0.24 | 0.21 | 0.19 | ||||||

| Digestible valine, % | 0.98 | 0.83 | 0.77 | ||||||

| Digestible arginine, % | 1.35 | 1.20 | 1.09 | ||||||

| Sodium, % | 0.20 | 0.19 | 0.18 | ||||||

| Potassium, % | 0.94 | 0.84 | 0.78 | ||||||

| Chloride, % | 0.28 | 0.29 | 0.26 | ||||||

| Dietary electrolyte balance, mEq/100 g | 267 | 233 | 222 | ||||||

| Corn drying temperature | 35°C | 80°C | 120°C | 35°C | 80°C | 120°C | 35°C | 80°C | 120°C |

| Analyzed nutrient and estimated AME9 | |||||||||

| DM, % | 88.20 | 88.45 | 88.72 | 87.95 | 87.34 | 88.00 | 88.00 | 88.22 | 88.91 |

| Moisture, % | 11.80 | 11.55 | 11.28 | 12.05 | 12.66 | 12.01 | 12.00 | 11.79 | 11.09 |

| AME, kcal/kg | 3,269 | 3,279 | 3,313 | 3,403 | 3,364 | 3,445 | 3,525 | 3,527 | 3,552 |

| CP, % | 26.52 | 26.78 | 25.95 | 23.70 | 23.43 | 23.39 | 21.78 | 21.93 | 21.64 |

| Total lysine, % | 1.57 | 1.59 | 1.55 | 1.37 | 1.35 | 1.36 | 1.25 | 1.27 | 1.22 |

| Total methionine, % | 0.71 | 0.72 | 0.72 | 0.61 | 0.62 | 0.65 | 0.60 | 0.61 | 0.61 |

| Total sulfur amino acids, % | 1.12 | 1.12 | 1.12 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 1.02 | 0.95 | 0.97 | 0.95 |

| Total threonine, % | 1.12 | 1.13 | 1.11 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.88 | 0.89 | 0.87 |

| Total glycine, % | 1.06 | 1.08 | 1.05 | 0.96 | 0.95 | 0.94 | 0.88 | 0.90 | 0.88 |

| Total isoleucine, % | 1.08 | 1.10 | 1.07 | 0.97 | 0.96 | 0.94 | 0.89 | 0.90 | 0.89 |

| Total leucine, % | 2.17 | 2.19 | 2.16 | 1.98 | 1.96 | 1.92 | 1.86 | 1.86 | 1.86 |

| Total valine, % | 1.21 | 1.23 | 1.20 | 1.08 | 1.07 | 1.06 | 1.00 | 1.01 | 1.00 |

| Total arginine, % | 1.70 | 1.73 | 1.68 | 1.52 | 1.50 | 1.49 | 1.39 | 1.40 | 1.36 |

| Analyzed nutrients of diets by wet chem10 | |||||||||

| DM, % | 95.00 | 95.09 | 95.02 | ||||||

| Starch, % | 33.71 | 31.93 | 32.90 | ||||||

| GE, kcal/kg | 4,145 | 4,126 | 4,157 | ||||||

| CP, % | 23.51 | 24.20 | 23.89 | ||||||

Starter diet was used for both experiments conducted in parallel.

Corn was included in the same inclusion level for all dietary treatments according to its phase. All other ingredients were mixed in a basal diet devoided of corn and amylase.

Insoluble marker (Titanium dioxide, Venator, Hombitan AFDC101, CAS 13463-67-7, Duisburg, Germany)

Either sand or amylase (Ronozyme HiStarch CT, batch ID: AU360086), 133g/ton were included according to each dietary treatment to supply 80 kilo-Novo alpha amylase units (KNU).

Trace minerals provided per kg of premix: manganese (Mn SO4), 60 g; zinc (ZnSO4), 60 g; iron (FeSO4), 40 g; copper (CuSO4), 5 g; iodine (Ca(IO3)2),1.25 g.

Vitamins provided per kg of premix: vitamin A, 13,227,513 IU; vitamin D3, 3,968,253 IU; vitamin E, 66,137 IU; vitamin B12, 39.6 mg; riboflavin, 13,227 mg; niacin, 110,229 mg; d-pantothenic acid, 22,045 mg; menadione, 3,968 mg; folic acid, 2,204 mg; vitamin B6, 7,936 mg; thiamine, 3,968 mg; biotin, 253.5 mg.

Coban 90 (Monensin), Elanco Animal Health, Greenfield, IN, at 500 g/ton in the starter and grower diets.

Ronozyme HiPhos GT, 200 g/ton to supply 1,000 FYT (Novozymes) delivering 0.14% of available P, and 0.10% of calcium.

Analyzed values are means of 2 samples in “DM” basis. Evonik Industries, Evonik Degussa GmbH, Hanau-Wolfgang, Germany.

Analyzed values are means of 4 samples.

After that, all diets were conditioned at 82°C for 30 s in a single pass conditioner (model C18LL4/F6, California Pellet Mill, Crawfordsville, IN) and then pelleted using a 30 HP CPM pellet mill (model PM1112-2, California Pellet Mill, Crawfordsville, IN) equipped with a 4.4 × 35.2 mm die with 548 cm2 of working surface area at a production rate of 980 kg/h. The steam pressure was 207 kPa. The pellet mill die was warmed with 455 kg of feed before pelleting the experimental batches. After pelleting, pellets were cooled in a counterflow cooler (Model VK09 × 09KL, Geelen Counterflow USA, Inc, Orlando, FL) and then crumbled (Model 624S, Roskamp Champion, Waterloo, IA) for the starter diets only while grower and finisher diets were in pellet form. Diets not containing the amylase were produced first, and feeds containing this enzyme were manufactured subsequently.

Chicken Husbandry

A total of 2,400 Ross-708 d-old male chicks were hatched at the North Carolina State University Chicken Education Unit's hatchery and were separated in 2 parallel experiments.

Experiment 1: A total of 1,920 chicks were randomly placed in 96-floor pens (2 m2) in groups of 20 birds per pen. Chicks were randomly assigned to 12 treatments with 8 replicates for each treatment. Each pen was equipped with one tubular feeder and one belt drinker. Supplemental feeders and drinkers were placed for the first 7 d of the study. The average temperature at placement was 33°C, which was gradually reduced to 20.6°C at 21 d and kept constant thereafter until 40 d. All pens were bedded with used litter. Broilers were exposed to continuous light on a 23L:1D (30 lux light intensity) program during the first 3 d of age. Day length was then gradually reduced to 17L:7D (10 lux) until 28 d of age. From 28 d until the end of the experiment, the light program was maintained at 17L:7D with an intensity of 5 lux.

Experiment 2: A total of 480-day-old chicks were distributed among 4 Petersime battery brooder units (96 cages of 0.47 m2 each; 5 chicks per cage) equipped with trough-type feeders and waterers. Chicks were then randomly assigned to 12 treatments with eight replicates for each treatment. The average temperature at placement was 33°C, which was transiently reduced to 26°C at 13 d and maintained until the end of the experiment. Chicks were exposed to continuous light on a 23L:1D (30 lux light intensity) program throughout the 16-d experimental period, and chickens received the only starter diets according to treatment during this period.

Experimental Procedure

In Experiment 1, chickens and feeders were weighed at 1, 14, 35, and 40 d to obtain BW and feed leftovers. BW gain, feed intake, and FCR were calculated thereafter, and at 40 d, individual BW of broilers were obtained to determine flock uniformity (CV%). In Experiment 2, chicks and feeders were weighed to obtain BW and feed leftovers at 13 d, and BW gain, feed intake, and FCR were calculated. At 15 d, excreta was collected on waxed paper in 2 shifts, being immediately mixed and pooled by cage and stored in a freezer at −15°C. Ileal digesta contents were obtained from all chicks at 16 d after euthanizing them by cervical dislocation, and digesta samples were collected from approximately 10 cm after the Meckel's diverticulum to approximately 5 cm before the ileocecal junction. Ilea digesta contents were flushed with de-ionized water into plastic containers, pooled by cage, and immediately stored in a freezer at −15°C. Excreta and ileal digesta samples were lyophilized using FreeZone 6 (Labconco Corp., Kansas City, MO). Subsequently, samples were ground to be able to pass through a 0.5-mm screen in a grinder.

Chemical Analysis and Parameter Calculations for Experiment 2

Proximate and amino acid content analyses of corn and soybean meal were conducted before feed formulation of experimental diets by near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS, DS2500, FOSS, Denmark) using calibration models developed by Evonik Nutrition & Care GmbH (Hanau, Hessen, Germany). All experimental diets were also analyzed with the same NIRS methodology and by wet chemistry as follows.

Dietary treatments (12 starter feeds), excreta, and ileal digesta samples were analyzed for DM, CP, and titanium dioxide content. Excreta samples were further analyzed for gross energy (GE) and ileal digesta samples for starch. DM was determined according to AOAC International (2012) standard methods, CP (N × 6.25) was determined by combustion method (LECO, AOAC International, 2006; method 990.03). The GE analysis was determined using an oxygen bomb calorimeter (IKA C5003; IKA Labortechnik, Staufen, Germany), and AME was corrected to zero N retention (AMEn) using a factor of 8.22 kcal/g (Hill and Anderson, 1958). Total starch, amylose proportion within the starch, resistant starch, and in vitro hydrolyzed starch or damaged starch analyses were done using Megazyme kits: Total Starch (amyloglucosidase/α-amylase method), Amylose/Amylopectin, Resistant Starch, and Starch Damage assay procedures following manufacturer's recommendations (Megazyme Inc., Chicago, IL). Gelatinized starch was conducted based on AACC 76-11.01/AOAC 979.10 method. Amylase activity in pelleted feed was determined using Megazyme kit assay of alpha-amylase using red-starch (Megazyme, Bray, Ireland). Titanium dioxide concentrations were measured in triplicate for dietary feeds and duplicates for excreta and ileal digesta samples on a UV spectrophotometer following the method described by (Myers et al., 2004). Apparent ileal digestibility, total tract utilization, and AMEn were calculated using the following equations (Kong and Adeola, 2014):

where Mi represents the concentration of titanium dioxide in the diet in g/kg DM; Mo represents the concentration of titanium dioxide in the excreta and ileal digesta in g/kg DM output; Ei represents the concentration of DM, CP, energy, or starch in the diet in mg/kg of DM; and Eo represents the concentration of DM, CP, starch, and energy in the excreta and ileal digesta, in mg/kg DM. The GEi is gross energy (kcal/kg) in the diet; GEo is the gross energy (kcal/kg) in the excreta; Ni represents nitrogen concentration in the diet; and No represents nitrogen concentration in the excreta in g/kg DM.

Statistical Analysis

The experimental design for the live performance experiments and nutrient utilization was a randomized complete block design with a factorial arrangement of 2 corn kernel hardness, 3 drying temperatures, and 2 amylase supplementation levels. For both experiments, each treatment had 8 replicates distributed equally either in 96-floor pens (Exp. 1) or 96 cages (Exp. 2). Additionally, the location of the floor pen inside the broiler house and the location of the cage in the batteries were considered blocks and random effects. Data for both experiments were analyzed separately and submitted to a 3-way ANOVA in a mixed model. Endosperm and starch traits were evaluated with a completely randomized design with the same factorial arrangement of treatments without the amylase effect. Mean separation was performed by the LS means method using Tukey's or Student t test at a significance level of alpha = 0.05. Pairwise correlations, regression, and principal component analyses were conducted to evaluate the effects of variability in corn endosperm and starch traits due to treatments on performance, nutrient, and energy utilization. Partition analyses were used to determine threshold levels of endosperm and starch properties on performance or nutrient utilization. All analyses were conducted using JMP 14 (SAS Institute. Inc., Cary, NC, 2018).

RESULTS

The effects of drying temperature on the endosperm vitreousness, protein solubility index, and starch traits of these 2 yellow dent corn varieties are presented in Table 1. Interaction effects (P < 0.01) between drying temperature and endosperm hardness were detected on vitreousness, amylose content, and in vitro hydrolyzed starch or damaged starch. Vitreousness was lower in average hardness corn dried at 80 and 120°C than at 35°C, but in the hard kernel, the one dried at 80°C had the highest vitreousness. The protein solubility index was reduced (P = 0.022) by drying at 80 and 120 °C. Both hybrids dried at 35°C, and hard kernel corn dried at 80°C had the lowest amylose concentrations within the starch. Furthermore, 1.5 and 2.4% points higher damaged starch was observed when average hardness corn was dried at 80 and 120°C, than in corn with harder endosperm. In corn with hard endosperm, kernels dried at 120 °C had lower damaged starch than those dried at 80 and 35°C. Gelatinized starch content was not affected (P > 0.05) by treatments. The resistant starch was higher (P = 0.08) in the average corn kernels. Vitreousness was positively correlated (P < 0.001) with amylopectin (r = 0.59), and negatively correlated with damaged starch (r = −0.61) and resistant starch (r = - 0.58). Damaged starch and resistant starch were positively (P < 0.001) correlated (r = 0.79). The analyzed DM, CP, and total amino acid contents of finished feeds were similar among treatments and data is shown in Table 2. Enzyme recovery analysis demonstrated that the results were in agreement with the expected values (Table 3). The concentration of Ronozyme HiStarch activity CT was similar to the targeted enzyme activity.

Table 3.

Declared and analyzed activities of amylase in the experimental diets1.

| Amylase, KNU/kg2 |

||

|---|---|---|

| Dietary treatments3 | Declared | Analyzed |

| Starter without amylase | 0 | 0.00 |

| Starter with amylase | 80 | 77.19 |

| Grower without amylase | 0 | 0.00 |

| Grower with amylase | 80 | 70.08 |

| Finisher without amylase | 0 | 0.00 |

| Finisher with amylase | 80 | 78.45 |

Enzyme activity of Ronozyme HiStarch CT is expressed as the quantity of product added in the feed.

KNU, kilo-Novo alpha-amylase units per kg of feed.

Analyzed values are means of 6 samples.

Live Performance

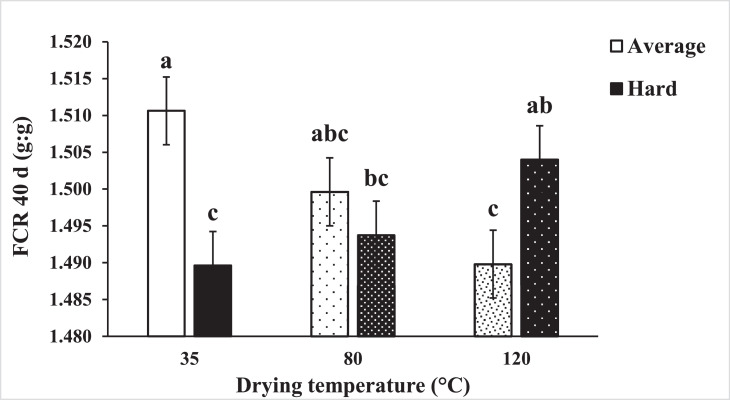

Experiment 1: Results of live performance are presented in Table 4, Table 5, Table 6. Interaction effects of treatments (Table 4) between drying temperature and amylase supplementation were observed on BW gain (P = 0.076) and BW (P = 0.073) at 14 d. Main differences were detected while feeding corn dried at 35°C, in which supplementing with an exogenous amylase increased the BW gain of chickens compared to broilers that consumed nonsupplemented diets. At 28 d (Table 5) a 3-way interaction effect was detected on BW, BW gain (P = 0.015) and FCR (P = 0.002). Only for chickens fed corn with average hardness and dried at 35°C, the addition of amylase enhanced the BW gain compared to broilers fed nonsupplemented diets (1,770 vs. 1,699 g); consequently; these chickens were heavier by about 71 g (P = 0.015). Furthermore, differences in FCR were mainly detected among the chickens that ate diets containing corn with average hardness. At this level, the supplementation with alpha-amylase resulted in improvements of 3.3 and 2.3 points of FCR in broilers fed corn dried at 35 and 80°C, respectively. In contrast, no effect was observed for chickens eating corn dried at 120°C. Interaction effects were detected at 40 d (Table 6) between drying temperature and amylase supplementation on BW gain (P = 0.05), BW (P = 0.05), FCR (P < 0.03), and flock uniformity (P = 0.003). Additionally, for FCR at 40 d (Figure 1), interaction effects between kernel hardness with drying temperature (P = 0.01) and kernel hardness with amylase supplementation (P < 0.001) were observed. Main differences were detected while drying the corn at 35°C. At this level, broilers fed amylase-supplemented diets gained more weight (∼90 g), resulting in heavier chickens (3,353 vs. 3,265 g), and FCR and flock uniformity were improved by 2 points and 1 % point respectively.

Experiment 2: Live performance results are presented in Table 7. No interaction effects (P > 0.05) were found among kernel hardness, drying temperature, and amylase supplementation on live performance at 14 d. Moreover, FCR was improved (P = 0.018) by 3 points when feeding diets containing corn dried at 120°C compared to feeding corn dried at 35 and 80°C. Feeding diets containing the harder kernel increased FCR (P = 0.055) by almost 2 points compared to chickens fed corn with average endosperm hardness (1.180 vs. 1.197 g:g). Feed intake was not affected (P > 0.05) by any of the parameters investigated in this study, and this was observed for both experiments.

Table 4.

Effect of corn kernel hardness, grain drying temperature (T), and enzyme supplementation on live performance of Ross 708 male broilers at 14 d raised in floor pens (Experiment 1).

| Kernel hardness1 | Drying T (°C) | Enzyme2 | BW |

BW |

BWG |

Feed intake |

FCR3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 d | 14 d | 0–14 d | 0–14 d | 0-14 d | |||

| –––––––––(g) –––––––– | – (g:g)– | ||||||

| Average | 44.5 | 516 | 472 | 583 | 1.232 | ||

| Hard | 44.6 | 512 | 468 | 578 | 1.233 | ||

| SEM | 0.1 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 0.006 | ||

| 35 | 44.5 | 512 | 468 | 576 | 1.231 | ||

| 80 | 44.5 | 514 | 469 | 581 | 1.232 | ||

| 120 | 44.5 | 517 | 472 | 585 | 1.235 | ||

| SEM | 0.1 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 0.007 | ||

| No | 44.6 | 513 | 469 | 580 | 1.233 | ||

| Yes | 44.5 | 515 | 471 | 582 | 1.232 | ||

| SEM | 0.1 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 0.006 | ||

| Average | 35 | 44.5 | 515 | 471 | 577 | 1.225 | |

| 80 | 44.5 | 514 | 470 | 587 | 1.238 | ||

| 120 | 44.5 | 519 | 475 | 586 | 1.234 | ||

| Hard | 35 | 44.6 | 509 | 465 | 575 | 1.237 | |

| 80 | 44.5 | 514 | 469 | 575 | 1.226 | ||

| 120 | 44.6 | 514 | 469 | 585 | 1.236 | ||

| SEM | 0.1 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 0.009 | ||

| 35 | No | 44.5 | 507 | 463 | 572 | 1.237 | |

| Yes | 44.6 | 517 | 473 | 579 | 1.225 | ||

| 80 | No | 44.6 | 517 | 472 | 583 | 1.230 | |

| Yes | 44.4 | 511 | 467 | 579 | 1.234 | ||

| 120 | No | 44.7 | 516 | 471 | 584 | 1.232 | |

| Yes | 44.4 | 517 | 473 | 586 | 1.238 | ||

| SEM | 0.1 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 0.009 | ||

| Average | No | 44.5 | 518 | 473 | 584 | 1.232 | |

| Yes | 44.4 | 515 | 471 | 582 | 1.232 | ||

| Hard | No | 44.6 | 509 | 464 | 576 | 1.234 | |

| Yes | 44.5 | 515 | 471 | 581 | 1.232 | ||

| SEM | 0.1 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 0.008 | ||

| Source of variation | ———————————– P values ———————————– | ||||||

| Hardness | 0.326 | 0.141 | 0.136 | 0.291 | 0.947 | ||

| Drying T (°C) | 0.872 | 0.460 | 0.452 | 0.202 | 0.901 | ||

| Enzyme | 0.101 | 0.510 | 0.482 | 0.682 | 0.898 | ||

| Hardness × T | 0.797 | 0.693 | 0.686 | 0.534 | 0.399 | ||

| Hardness × Enzyme | 0.981 | 0.114 | 0.112 | 0.364 | 0.929 | ||

| Drying T × Enzyme | 0.150 | 0.073 | 0.076 | 0.553 | 0.561 | ||

| Hardness × T × Enzyme | 0.118 | 0.413 | 0.412 | 0.675 | 0.890 | ||

Values are means ± SEM of 8 pens per treatment combination with 20 male broiler chickens per pen.

Average (DEKALB 68-05) and hard kernel corn (DEKALB 65-20) with vitreousness of 66.86 and 68.84% predyring respectively, measured with NIRS (DS2500, FOSS, Denmark).

Ronozyme HiStarch CT to supply 80 (133 g/ton) kilo-Novo alpha amylase units (KNU).

Adjusted feed conversion ratio (FCR) with body weight of mortality for this period.

Table 5.

Effect of corn kernel hardness, grain drying temperature (T), and enzyme supplementation on live performance of Ross 708 male broilers at 28 d raised in floor pens (Experiment 1).

| Kernel hardness1 | Drying T (°C) | Enzyme2 | BW |

BWG |

Feed intake |

FCR3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 28 d | 0–28 d | 0–28 d | 0–28 d | |||

| —————(g) ————— | –(g:g)– | |||||

| Average | 1,795 | 1,751 | 2,416 | 1.376 | ||

| Hard | 1,792 | 1,747 | 2,413 | 1.375 | ||

| SEM | 7 | 7 | 11 | 0.003 | ||

| 35 | 1,779b | 1,735b | 2,404 | 1.379 | ||

| 80 | 1,796ab | 1,751ab | 2,414 | 1.373 | ||

| 120 | 1,806a | 1,761a | 2,426 | 1.374 | ||

| SEM | 8 | 8 | 13 | 0.003 | ||

| No | 1,787 | 1,742 | 2,408 | 1.379 | ||

| Yes | 1,801 | 1,756 | 2,421 | 1.372 | ||

| SEM | 7 | 7 | 11 | 0.003 | ||

| Average | 35 | No | 1,743b | 1,699d | 2,390 | 1.401a |

| Yes | 1,814ab | 1,770ab | 2,424 | 1.368cd | ||

| 80 | No | 1,793ab | 1,749abc | 2,429 | 1.385ab | |

| Yes | 1,817a | 1,773a | 2,423 | 1.362d | ||

| 120 | No | 1,811ab | 1,766ab | 2,420 | 1.367cd | |

| Yes | 1,794ab | 1,750abc | 2,410 | 1.375bcd | ||

| Hard | 35 | No | 1,774ab | 1,730bcd | 2,376 | 1.369cd |

| Yes | 1,787ab | 1,742abc | 2,425 | 1.377bcd | ||

| 80 | No | 1,806ab | 1,761abc | 2,412 | 1.369cd | |

| Yes | 1,768ab | 1,723cd | 2,393 | 1.378bcd | ||

| 120 | No | 1,793ab | 1,748abc | 2,424 | 1.383bc | |

| Yes | 1,825a | 1,781a | 2,451 | 1.373bcd | ||

| SEM | 15 | 15 | 23 | 0.006 | ||

| Source of variation | ———————————– P values ———————————– | |||||

| Hardness | 0.693 | 0.686 | 0.839 | 0.613 | ||

| Drying T (°C) | 0.049 | 0.050 | 0.362 | 0.440 | ||

| Enzyme | 0.107 | 0.105 | 0.326 | 0.051 | ||

| Hardness × T | 0.457 | 0.458 | 0.331 | 0.096 | ||

| Hardness × Enzyme | 0.174 | 0.169 | 0.594 | 0.011 | ||

| Drying T × Enzyme | 0.071 | 0.071 | 0.218 | 0.436 | ||

| Hardness × T x Enzyme | 0.015 | 0.015 | 0.725 | 0.002 | ||

Values are means ± SEM of 8 pens per treatment combination with 20 male broiler chickens per pen.

Means in a column not sharing a common superscript are significantly different (P < 0.05) by Student's t or Tukey's test.

Average (DEKALB 68-05) and hard kernel corn (DEKALB 65-20) with vitreousness of 66.86 and 68.84% respectively, measured with NIRS (DS2500, FOSS, Denmark).

Ronozyme HiStarch CT to supply 80 (133 g/ton) kilo-Novo alpha amylase units (KNU).

Adjusted feed conversion ratio (FCR) with body weight of mortality for this period.

Table 6.

Effect of corn kernel hardness, grain drying temperature (T), and enzyme supplementation on live performance of Ross 708 male broilers at 40 d raised in floor pens (Experiment 1).

| Kernel hardness1 | Drying T (°C) | Enzyme2 | BW |

BWG |

Feed intake |

FCR3 |

CV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 40 d | 0–40 d | 0–40 d | 0–40 d | 40 d | |||

| —————(g) ————— | –(g:g)– | –(%)– | |||||

| Average | 3,324 | 3,279 | 4,947 | 1.500 | 7.21 | ||

| Hard | 3,323 | 3,278 | 4,945 | 1.496 | 7.43 | ||

| SEM | 13 | 13 | 22 | 0.003 | 0.16 | ||

| 35 | 3,309 | 3,264 | 4,923 | 1.500 | 7.69 | ||

| 80 | 3,325 | 3,281 | 4,955 | 1.497 | 7.36 | ||

| 120 | 3,336 | 3,291 | 4,960 | 1.497 | 6.91 | ||

| SEM | 15 | 15 | 27 | 0.003 | 0.20 | ||

| No | 3,304b | 3,260b | 4,920 | 1.502 | 7.39 | ||

| Yes | 3,342a | 3,298a | 4,972 | 1.494 | 7.25 | ||

| SEM | 13 | 13 | 22 | 0.003 | 0.16 | ||

| 35 | No | 3,265b | 3,220b | 4,858 | 1.510a | 8.21a | |

| Yes | 3,353a | 3,309a | 4,989 | 1.490b | 7.18bc | ||

| 80 | No | 3,320ab | 3,275ab | 4,940 | 1.500ab | 7.58ab | |

| Yes | 3,331ab | 3,286ab | 4,969 | 1.493b | 7.14bc | ||

| 120 | No | 3,329ab | 3,284ab | 4,961 | 1.495b | 6.37c | |

| Yes | 3,343a | 3,299a | 4,959 | 1.499ab | 7.45ab | ||

| SEM | 19 | 19 | 38 | 0.005 | 0.30 | ||

| Average | No | 3,299 | 3,254 | 4,940 | 1.512a | 7.34 | |

| Yes | 3,349 | 3,304 | 4,954 | 1.488c | 7.07 | ||

| Hard | No | 3,310 | 3,265 | 4,899 | 1.492bc | 7.43 | |

| Yes | 3,336 | 3,291 | 4,991 | 1.500b | 7.43 | ||

| SEM | 16 | 16 | 31 | 0.004 | 0.24 | ||

| Source of variation | ———————————– P values ———————————– | ||||||

| Hardness | 0.952 | 0.947 | 0.937 | 0.240 | 0.365 | ||

| Drying T (°C) | 0.302 | 0.301 | 0.570 | 0.681 | 0.041 | ||

| Enzyme | 0.009 | 0.009 | 0.086 | 0.036 | 0.597 | ||

| Hardness × Drying T | 0.141 | 0.142 | 0.073 | 0.001 | 0.628 | ||

| Drying T × Enzyme | 0.050 | 0.050 | 0.184 | 0.030 | 0.003 | ||

| Hardness × Enzyme | 0.394 | 0.393 | 0.201 | <0.001 | 0.591 | ||

| Hardness × T × Enzyme | 0.530 | 0.525 | 0.812 | 0.185 | 0.677 | ||

Values are means ± SEM of 8 pens per treatment combination with 20 male broiler chickens per pen.

Means in a column not sharing a common superscript are significantly different (P < 0.05) by Student's t or Tukey's test.

Average (DEKALB 68-05) and hard kernel corn (DEKALB 65-20) with vitreousness of 66.86 and 68.84% respectively, measured with NIRS (DS2500, FOSS, Denmark).

Ronozyme HiStarch CT to supply 80 (133 g/ton) kilo-Novo alpha amylase units (KNU).

Adjusted feed conversion ratio (FCR) with body weight of mortality for this period.

Figure 1.

Effect of corn kernel hardness (average and hard) and drying temperature (35, 80, and 120°C) on FCR at 40 d. Means not sharing a common superscript (a-c) are significantly different (n = 8; P < 0.01) by Tukey's test.

Table 7.

Effect of corn kernel hardness, grain drying temperature (T), and enzyme supplementation on live performance at 14 d of Ross 708 male broilers raised in battery cages (Experiment 2).

| Kernel hardness1 | Drying T (°C) | Enzyme2 | BW |

BWG |

Feed intake |

FCR3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 14 d | 0–14 d | 0–14 d | 0–14 d | |||

| —————(g) ————— | (g:g) | |||||

| Average | 466 | 422 | 506 | 1.197 | ||

| Hard | 465 | 421 | 497 | 1.180 | ||

| SEM | 3 | 3 | 4 | 0.006 | ||

| 35 | 462 | 418 | 500 | 1.196a | ||

| 80 | 466 | 422 | 506 | 1.198a | ||

| 120 | 469 | 425 | 499 | 1.170b | ||

| SEM | 4 | 4 | 4 | 0.008 | ||

| No | 464 | 420 | 500 | 1.189 | ||

| Yes | 467 | 423 | 503 | 1.187 | ||

| SEM | 3 | 3 | 4 | 0.006 | ||

| 35 | No | 459 | 416 | 498 | 1.199 | |

| Yes | 464 | 420 | 501 | 1.194 | ||

| 80 | No | 462 | 419 | 501 | 1.196 | |

| Yes | 470 | 426 | 511 | 1.200 | ||

| 120 | No | 470 | 427 | 500 | 1.173 | |

| Yes | 467 | 423 | 498 | 1.167 | ||

| SEM | 6 | 6 | 6 | 0.011 | ||

| Average | No | 468 | 424 | 507 | 1.198 | |

| Yes | 464 | 420 | 504 | 1.196 | ||

| Hard | No | 460 | 417 | 492 | 1.181 | |

| Yes | 470 | 426 | 502 | 1.178 | ||

| SEM | 5 | 5 | 5 | 0.009 | ||

| Source of variation | P values | |||||

| Hardness | 0.910 | 0.894 | 0.087 | 0.055 | ||

| Drying T (°C) | 0.487 | 0.480 | 0.449 | 0.018 | ||

| Enzyme | 0.543 | 0.549 | 0.454 | 0.792 | ||

| Hardness × Drying T | 0.411 | 0.410 | 0.072 | 0.228 | ||

| Hardness × Enzyme | 0.141 | 0.138 | 0.188 | 0.951 | ||

| Drying T × Enzyme | 0.594 | 0.632 | 0.612 | 0.898 | ||

| Hardness × T × Enzyme | 0.351 | 0.358 | 0.063 | 0.304 | ||

Values are means ± SEM of 8 pens per treatment combination with 20 male broiler chickens per pen.

Means in a column not sharing a common superscript are significantly different (P < 0.05) by Student's t or Tukey's test.

Average (DEKALB 68-05) and hard kernel corn (DEKALB 65-20) with vitreousness of 66.86 and 68.84%, respectively, measured with NIRS (DS2500, FOSS, Denmark).

Ronozyme HiStarch CT to supply 80 (133 g/ton) kilo-Novo alpha amylase units (KNU).

Adjusted feed conversion ratio (FCR) with body weight of mortality for this period.

Nutrient Digestibility and AMEn

The effects of kernel hardness, drying temperature, and amylase supplementation on apparent ileal digestibility and total tract retention until 16 d in experiment 2 are presented in Table 8. A 3-way interaction effect (P < 0.05) among kernel hardness, drying temperature, and amylase supplementation was observed on AID of DM and CP. Differences were mainly detected when feeding diets containing corn with average kernel hardness. At 120°C level, the inclusion of amylase decreased the CP digestibility by 4.4% compared to nonsupplementation. Starch total tract retention was increased by feeding corn with average hardness (P = 0.016), dried at 35°C (P < 0.001), and amylase supplementation (P = 0.011). Improvements up to 0.54, 1.29, and 0.56% points due to these factors were detected compared to their respective counterparts. Furthermore, ileal digestibility of starch in broilers fed hard endosperm corn-based diets was decreased (P < 0.001) by 2.23% points compared to feeding with average hardness corn (91.26 vs. 93.49 %, respectively).

Table 8.

Effect of corn kernel hardness, grain drying temperature (T), and enzyme supplementation on nutrient digestibility at 16 d in battery cages (Experiment 2).

| Kernel hardness1 | Drying T (°C) | Enzyme2 | Apparent ileal digestibility |

Total tract retention |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DM | CP | Starch | Starch | AMEn | |||

| —————(%)————— | % | kcal/kg DM | |||||

| Average | 71.32 | 84.89 | 93.49a | 96.22a | 3,421 | ||

| Hard | 71.00 | 84.00 | 91.26b | 95.68b | 3,467 | ||

| SEM | 0.92 | 0.56 | 0.36 | 0.16 | 13 | ||

| 35 | 71.29 | 84.74 | 92.74 | 96.64a | 3,513a | ||

| 80 | 70.14 | 83.48 | 91.81 | 95.35b | 3,326b | ||

| 120 | 72.05 | 85.11 | 92.58 | 95.86b | 3,494a | ||

| SEM | 1.08 | 0.66 | 0.45 | 0.19 | 18 | ||

| No | 71.90 | 84.93 | 92.90 | 95.67b | 3,420 | ||

| Yes | 70.41 | 83.96 | 91.86 | 96.23a | 3,468 | ||

| SEM | 0.93 | 0.57 | 0.36 | 0.16 | 13 | ||

| Average | 35 | 71.05ab | 85.88ab | 93.31 | 97.16 | 3,573a | |

| 80 | 72.58a | 84.56abc | 93.25 | 95.54 | 3,263c | ||

| 120 | 70.34ab | 84.23abc | 93.92 | 95.97 | 3,428b | ||

| Hard | 35 | 71.53ab | 83.60bc | 92.18 | 96.12 | 3,452ab | |

| 80 | 67.70b | 82.41c | 90.37 | 95.16 | 3,388b | ||

| 120 | 73.77a | 86.00a | 91.24 | 95.76 | 3,560a | ||

| SEM | 1.45 | 0.88 | 0.65 | 0.27 | 28 | ||

| 35 | No | 71.10ab | 84.51ab | 92.86 | 96.58 | 3,527a | |

| Yes | 71.48ab | 84.97ab | 92.62 | 96.70 | 3,498a | ||

| 80 | No | 69.87b | 83.51b | 92.30 | 94.77 | 3,253c | |

| Yes | 70.41b | 83.46b | 91.33 | 95.93 | 3,399b | ||

| 120 | No | 74.75a | 86.78a | 93.53 | 95.65 | 3,481a | |

| Yes | 69.35b | 83.44b | 91.62 | 96.08 | 3,507a | ||

| SEM | 1.45 | 0.88 | 0.65 | 0.27 | 28 | ||

| Average | 35 | No | 69.39bcd | 84.96abcd | 92.96 | 97.28 | 3,560 |

| Yes | 72.71abc | 86.79ab | 93.66 | 97.04 | 3,585 | ||

| 80 | No | 74.23ab | 86.11abc | 94.38 | 94.69 | 3,169 | |

| Yes | 70.93bcd | 83.01cde | 92.12 | 96.39 | 3,358 | ||

| 120 | No | 72.38abc | 86.04abc | 94.60 | 95.57 | 3,424 | |

| Yes | 68.29cd | 82.42de | 93.23 | 96.36 | 3,432 | ||

| Hard | 35 | No | 72.80abc | 84.06bcde | 92.77 | 95.87 | 3,494 |

| Yes | 70.25bcd | 83.15cde | 91.58 | 96.37 | 3,410 | ||

| 80 | No | 65.50d | 80.91e | 90.21 | 94.85 | 3,336 | |

| Yes | 69.90bcd | 83.91bcde | 90.53 | 95.46 | 3,440 | ||

| 120 | No | 77.12a | 87.52a | 92.46 | 95.73 | 3,538 | |

| Yes | 70.41bcd | 84.47abcd | 90.02 | 95.80 | 3,583 | ||

| SEM | 2.00 | 1.15 | 0.93 | 0.40 | 41 | ||

| CV% | 7.39 | 3.85 | 2.81 | 1.07 | 3.37 | ||

| Source of variation | ——————————— P values —————————- | ||||||

| Hardness | 0.775 | 0.195 | <0.001 | 0.016 | 0.064 | ||

| Drying T (°C) | 0.381 | 0.124 | 0.342 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| Enzyme | 0.190 | 0.154 | 0.058 | 0.011 | 0.053 | ||

| Hardness × Drying T | 0.012 | 0.024 | 0.352 | 0.293 | <0.001 | ||

| Hardness × Enzyme | 0.907 | 0.337 | 0.905 | 0.424 | 0.280 | ||

| Drying T × Enzyme | 0.048 | 0.049 | 0.442 | 0.149 | 0.014 | ||

| Hardness × T × Enzyme | 0.046 | 0.033 | 0.218 | 0.231 | 0.422 | ||

Values are means ± SEM of 8 pens per treatment combination with 3 male broiler chickens per pen.

Means in a column not sharing a common superscript are significantly different (P < 0.05) by Student's t or Tukey's test.

Average (DEKALB 68-05) and hard kernel corn (DEKALB 65-20) with vitreousness of 66.86 and 68.84%, respectively, measured with NIRS (DS2500, FOSS, Denmark).

Ronozyme HiStarch CT to supply 80 (133 g/ton) kilo-Novo alpha amylase units (KNU).

Moreover, starch digestibility at the ileal section was not influenced (P > 0.05) by drying temperature, amylase supplementation, or their interaction effects. Results obtained in AMEn showed interaction effects of kernel hardness with drying temperature (P < 0.001) and drying temperature with amylase supplementation (P = 0.014). For broilers fed diets with average kernel hardness corn, increasing the grain drying temperature to 80°C resulted in 310 less kcal/kg of AMEn and 120°C in a reduction of 145 kcal/kg of AMEn. For chickens fed diets with harder corn, increasing the drying temperature to 120°C did not cause a significant change. Still, numerically the AMEn improved by 108 kcal/kg compared to chickens consuming corn dried at 35°C. Diets with hard kernel corn dried at 80°C had 172 kcal/kg of AMEn less than those with corn dried at 120°C. In both corn varieties, drying at 80°C was more detrimental for AMEn with a combined average 172 kcal/kg reduction. However, the dietary inclusion of amylase improved 146 kcal/kg AMEn only in corn dried at 80°C (3,399 vs. 3,253 kcal/kg DM), and no significant differences due to amylase inclusion were observed on the AMEn of diets containing corn dried at 35 and 120°C.

DISCUSSION

The results in the studies presented herein confirm the interactive effects among yellow dent kernel hardness, drying temperature, and amylase supplementation on corn endosperm and starch traits, nutrient digestibility, energy utilization, and live performance. The difference in genetics of corn hybrids (Wang et al., 1993) and drying temperature affected starch structure, amylose:amylopectin ratio (AM:AP), damaged starch, and protein solubility of corn (Table 1), as discussed by Odjo et al. (2015) and Malumba et al. (2009). Damaged starch is known to increase water absorption capacity, susceptibility to erosion by α-amylase, and ultimately increase starch digestion (Tester, 1997).

The reduction in corn protein solubility index indicated modifications in the protein-starch matrix caused by heat during drying (Odjo et al., 2015). Heat treatments are known to increase Maillard reaction products (MRP) in all feedstuff ingredients (Hofmann et al., 2020). Reactive lysine and digestibility have been used as parameters to evaluate the final impact of the Maillard reaction, but there are many other MRP. These MRP have been evaluated especially in feedstuffs with higher protein and lysine content than corn like distiller dried grains with solubles (DDGS) and soybean, canola, and sunflower meals (Almeida, 2013; Hofmann et al., 2020). Preliminary evaluations of reactive lysine in a limited number of corn samples of the treatments evaluated in the present study indicated small differences with total lysine. No significant effects of drying temperatures were detected.

Consequently, MRP were not explored in the present study. However, several methodologies evaluate reactive lysine and MRP (Almeida, 2013; Hofmann et al., 2020). Additional evaluations of MRP could be important for future studies related to this topic, considering the results observed in the present experiment.

The effects on chicken live performance varied according to age. Young chickens in cages showed better FCR at 16 d when dietary treatments included hard corn kernel and both corn varieties dried at 120°C. In contrast, the final FCR of broilers, in floor pens at 40 d, was improved when corn was dried at high temperature only in those that consumed diets based on average corn kernel hardness, whereas for broilers fed diets containing corn with the hard kernel, the FCR was worsened as drying temperature increased (Figure 1). Nir et al. (1993) found that the pancreatic amylase activity was suboptimal in young chickens compared to older birds, and Uni et al. (1998) concluded that the gastrointestinal tract development in neonate chickens is immature. A similar response has been reported in young turkeys (Krogdahl and Sell, 1989). Therefore, optimal utilization of gelatinized or damaged starch in younger chicks may be limited. In the cage experiment, lower (P ≤ 0.01) damaged starch in the hard corn kernel (2.35 vs. 3.75%) and corn dried at 120°C (2.59 vs. 3.20, and 3.38%) was associated with better FCR at 16 d (Table 7).

It is important to consider that these treatments could cause changes in grain fragmentation during grinding and differences in the pelleting properties. The effects of corn variety and drying temperatures on particle size post-grinding under hammer and roller milling and on the pellet durability index (PDI) during the present study have been published by Córdova-Noboa et al. (2021). Briefly, in this study, hard corn kernel had a slightly bigger (P < 0.01) particle size (660 vs. 604 µm) geometric mean (dgw) than average corn kernel hardness. Corn dried at 120°C had lower (P < 0.001) particle size than corn dried at 35°C in starter (621 vs. 660 µm) and finisher (759 vs. 817 µm) diets. The small differences in particle size affected (P < 0.001) the FCR of chickens fed diets with hard corn kernel, but no effects (P > 0.05) were observed on the FCR of those fed average kernel hardness. Two regression models fitted the data (P < 0.001) and the small effect of corn dgw was modeled as FCR 40 d = −3.01986 + 0.00276*dgw starter + 0.00331 * dgw grower (R2 = 0.32) or FCR 40 d = 1.90149 – 0.000485 *dgw finisher (R2 = 0.21). The dgw did not affect (P > 0.05) starch digestibility or AMEn for average hardness corn, but was correlated (P < 0.01) with AMEn (r = 0.39) for hard corn kernel (AMEn 16 d = 2,523.5969 + 1.4338 8 dgw corn starter; R2 = 0.29). The geometric standard deviation of particle size (Sgw) was correlated (P < 0.001) with total tract starch digestibility (r = −0.33), and AMEn of both average (r = −0.58) and hard corn kernel (r = −0.45), but was not correlated (P > 0.05) with starch ileal digestibility. The PDI was correlated (P < 0.001) positively with dgw (r = 0.54) in the finisher diets and damaged starch (r = 0.41) in the starter diets. The PDI was positively correlated (r = 0.36) with FCR up to 28 d of age (P < 0.001).

The weak effects of corn particle size post grinding were influenced by AM:AP, damaged and resistant starch that were correlated to changes in corn vitreousness due to drying temperatures. The dgw of corn milled for grower diets was (P < 0.001) positively correlated (r = 0.69) with amylopectin content and negatively correlated with AM:AP (r = −0.68) and damaged starch (r = −0.65). The Sgw of corn ground for grower and finisher diets was positively correlated (P < 0.001) with damaged starch (r = 0.91 and 0.76, respectively). However, when the effects of dgw and Sgw were tested in several multiple linear regression models or principal component analysis to explain data variance in parameters of live performance or nutrient utilization, always amylose or amylopectin contents or its ratio, vitreousness, and damaged starch were stronger effects.

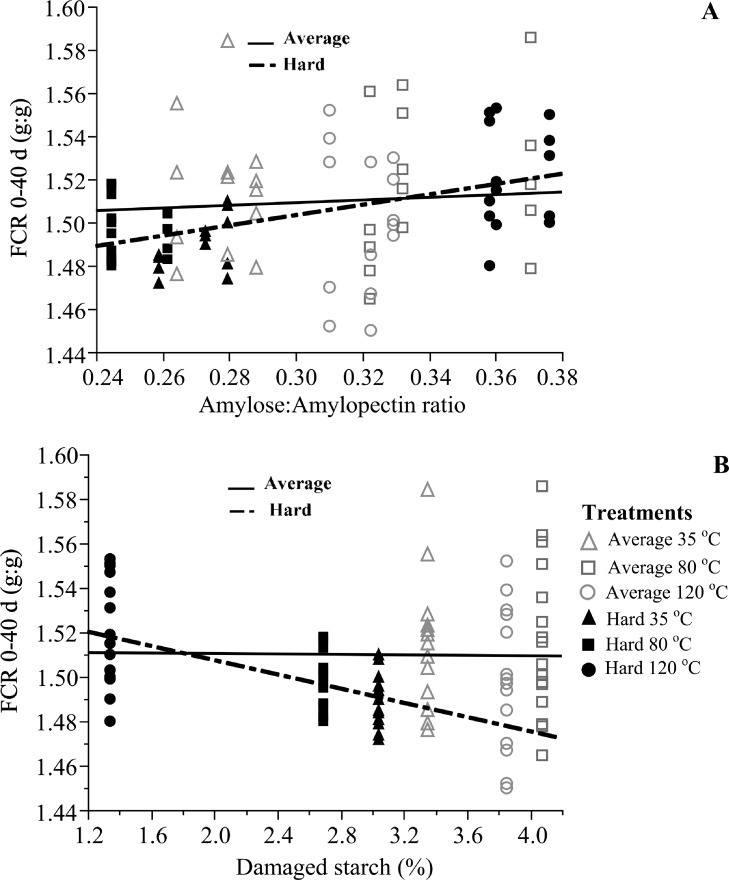

Vitreousness, protein solubility, and gelatinized starch were not correlated (P > 0.05) with FCR or flock uniformity, but AM:AP, damaged starch and resistant starch affected (P < 0.001) FCR (Figure 3) and feed intake mainly from 28 to 40 d (Feed intake 28 to 40 d = 2,003.631 + 1,092.727*AM:AP; R2 = 0.43), only in chickens fed diets with hard endosperm corn. Opposite effect on feed intake was observed (P < 0.001) with resistant starch (Feed intake 28–40 d = 5,793.701 – 788.421 * resistant starch; R2 = 0.40). Higher levels of resistant starch have been associated with positive gut microbiome modulation, improved nutrient utilization, and hindgut health (Zhang et al., 2020).

Figure 3.

(Panel A) Linear effect of corn Amylose:Amylopectin ratio (AM:AP) on FCR at 40 d in corn with average (P > 0.05) and hard (P < 0.001) kernel (FCR 0–40 d = 1.432 + 0.239*AM:AP; R2 = 0.34). (Panel B) Linear effect of damaged starch determined as in vitro hydrolyzed starch on FCR at 40 d (P < 0.01) in corn with average (P > 0.05) and hard (P < 0.001) kernel hardness (FCR 0–40 d = 1.5394 − 0.016* damaged starch; R2 = 0.34). Markers represent the eight means per treatment combination of kernel hardness (average or hard) and drying temperatures (35, 80, or 120°C) postharvest and lines the linear fit by kernel hardness.

The beneficial effects of amylase supplementation on growth performance were more evident when feeding diets containing corn with average endosperm hardness and diets based on corn dried at 35°C. Similarly, Kaczmarek et al. (2014a) observed the interactive effects of kernel hardness with drying temperature and hardness with enzyme (phytase + xylanase) addition on the AID of protein in chickens fed corn-SBM diets at 35 d. In agreement with our results, responses were most notably for chickens fed the softer kernel compared to feeding vitreous (harder kernel) corn. These researchers suggested that higher drying temperatures resulted in lower CP digestibility. In this experiment, that effect only was observed in hard kernel dried at 80°C. These contradictory responses may be due to different parameters affecting the nutritional content of the grain while drying, such as initial moisture, type of dryer, heat drying process, and duration of drying (Barrier-Guillot et al., 1993; Odjo et al., 2012; Malumba et al., 2014). In the current study, to reduce the moisture content while drying the corn at 35 and 80°C, it was required a longer time than to dry it at 120°C. The drying process at 120°C needed 4 to 5 h, whereas drying at 80 and 35°C took 7 to 8 h and 9 to 10 h, respectively. Thus, the starch properties and protein solubility may have been compromised (Table 1) as observed by previous researchers (Jayas and White, 2003; Malumba et al., 2008; Li et al., 2014).

Several studies described the potential of amylase supplementation to improve live performance and nutrient utilization in corn-SBM based-diets while being used in combination with xylanase, NSPs, and protease, suggesting synergism among these feed additives (Cowieson and Ravindran, 2008; Tang et al., 2014; Olukosi et al., 2015; Amerah et al., 2017) at any live production phase of broilers (Berti Sorbara et al., 2009). However, other authors observed no beneficial effects on growth performance and starch ileal digestibility when using an exogenous amylase alone (Kaczmarek et al., 2014b; Stefanello et al., 2015, 2017). Conversely, Gracia et al. (2003) concluded that starch digestibility and AMEn were increased in chickens by adding a different exogenous alpha-amylase (1,720 units of α-amylase/kg from Bacillus amyloliquefaciens) to corn-based diets.

Responses to amylase are related to starch digestibility. In the current experiment, lower values were observed for starch ileal digestibility compared to those for total tract starch retention. This is likely to be due to some cecal fermentation of starch (Józefiak et al., 2004) and starch digestion rate (Weurding et al., 2002a) in different portions of the intestine that could be affected by the hydrothermal processing that changed damaged starch (Weurding et al., 2002b) and the amylase activity. According to Klein (2013) and Kaczmarek et al. (2014b), responses in performance when supplementing an amylase may vary depending on intrinsic traits or characteristics of corn (Pirgozliev et al., 2010). In the current study, an inspection of the interactions revealed that the effects of amylase were notably dependent on the combination of corn kernel hardness and drying temperature caused by vitreousness, protein solubility index, AM:AP, and damaged starch. A recent study conducted by Córdova-Noboa et al. (2020b) showed beneficial effects of increasing amylase supplementation from 133 to 266 g/ton (80–160 kilo-Novo alpha-amylase units, respectively) on nutrient digestibility, energy utilization, and live performance of broilers fed diets based on hard kernel corn. The differences in responses to amylase depending on corn vitreousness could potentially explain the contradictory responses observed in previous experiments when supplementing amylase alone and the need for different amylase levels according to kernel hardness and other starch properties (Jiang et al., 2008).

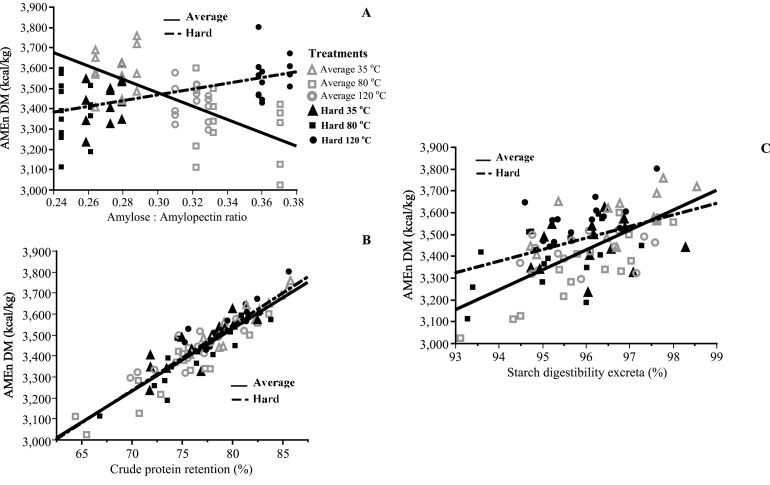

Results of the current studies indicated that damaged starch was negatively correlated (P < 0.001) with AMEn for average corn kernel (r = −0.64) and hard corn kernel (r = −0.47). Within the starch, it is also important to consider the AM:AP (Pirgozliev et al., 2010). In our data, higher amylose content reduced total tract digestibility of starch for average (r = 0.51; P < 0.001) and hard (r = 0.31; P < 0.05) corn kernel hardness at 16 d for chicks raised in cages. The AMEn was reduced (P < 0.001) when AM:AP increased (r = −0.51) for the average corn kernel, in contrast, for chicks fed diets based on harder kernel, the AMEn was positively correlated with AM:AP (r = 0.55). Even though the AM:AP affected linearly (P < 0.001) the AMEn (Figure 2, Panel A), it only partially explained the variability of energy utilization data for average kernel hardness (R2 = 0.37) and hard kernel corn (R2 = 0.30). The CP ileal digestibility had (P = 0.01) a weak correlation (r = 0.26) with AMEn, while the CP total tract digestibility measured in excreta or N retention had (P < 0.001) a strong correlation (r = 0.92). This effect (P < 0.001) by kernel hardness is observed in Figure 2, Panel B. The CP total tract digestibility was affected (P < 0.001) mainly by AM:AP, but vary by kernel hardness. In diets with corn of average hardness chicken CP total tract digestibility decreased (P < 0.001) as AM:AP increased (CP dig. = 105.304 − 88.990*AM:AP; R2 = 0.37), while in diets with hard kernel this weak effect (P < 0.001) was positive (CP dig. = 67.799 + 32.897*AM:AP; R2 = 0. 23). When damaged and resistant starch increased CP total digestibility decreased (P < 0.001) independently of kernel hardness (r = −0.47).

Figure 2.

(Panel A) Linear effect of amylose content on AMEn at 16 d in corn with average (P < 0.001) and hard kernel (P < 0.001) hardness. For average corn kernel hardness AMEn = 4,437.792 – 3,144.344* amylose:amylopectin ratio AM:AP (R2 = 0.44). For hard corn kernel AMEn = 3,040.029 + 1,421.562* AM:AP (R2 = 0.30). (Panel B.)Linear effect of CP retention assessed in excreta samples on AMEn at 16 d of age in corn with average (P < 0.001) and hard kernel (P < 0.001). For average corn kernel hardness AMEn = 1,152.539 + 29.676*CP retention (R2 = 0.86). For hard corn kernel AMEn = 1,067.541 + 30.942*CP retention (R2 = 0.79). (Panel C) Linear effect of starch digestibility evaluated in excreta samples on AMEn at 16 d of age in corn with average (P < 0.001) and hard kernel (P = 0.004). For average corn kernel hardness AMEn = −5,340.215 + 91.327*Starch dig (R2 = 0.50). For hard corn kernel AMEn = −1,611.428 + 53.057*Starch dig. (R2 = 0.17). Markers represent the eight means per treatment combination of kernel hardness (average or hard) and drying temperatures (35, 80, or 120°C) postharvest and lines the linear fit by kernel hardness.

Vitreousness and protein solubility index had a positive effect (P < 0.001) on CP total digestibility (r = 0.48 and 0.54, respectively), but only for diets with average hardness. The solubility index of total salt-soluble proteins is a suitable indicator of the severity of the corn drying treatment (Malumba et al., 2009). However, the effects of these four parameters were weaker than the AM:AP when tested in multiple linear regression models and principal component analysis. Total tract starch digestibility assessed using excreta, but no ileal starch digestibility (P > 0.05), was positively correlated (r = 0.55) and had a linear positive effect (P < 0.01) on AMEn in chickens fed either average or hard corn kernels (Figure 2, Panel C). Hindgut fermentation of N and starch seem to play an important role (Józefiak et al., 2004).

Multiple linear regression models were fitted to explain AMEn data variability including principal components. In all the models evaluated differences due to corn kernel hardness were observed. The model for corn with average kernel hardness explained (P < 0.001) 92% of the observed variance (AMEn average hardness = 1,279.839 – 957.123*AM:AP + 6.901*Starch ileal dig. + 23.632*CP total tract dig.). While the model for hard corn kernel explained 82% of the observed variance (AMEn hard kernel = 805.494 + 29.019 *CP total tract dig. + 0.624*dgw corn starter). In both models, total tract digestibility of CP explained 85.5 and 95.1% of the total variance, respectively. Consequently, it could be hypothesized that the dietary energy utilization of corn not only depends on the AM:AP and other starch properties but also on the interaction of starch with protein matrix in the endosperm affected by the treatments evaluated in the present experiment (Pirgozliev et al., 2010). This interaction effect was partially captured (P < 0.001) by endosperm vitreousness (r = 0.59) and the salt-protein solubility index (r = 0.52), but only for the average hardness corn. It can be hypothesized that some MRP may explain better the effects of corn drying temperatures on the protein-starch matrix for all varieties of corn.

A previous study (Zhou et al., 2010) conducted in ducks detected a strong positive correlation (r = 0.86, P < 0.05) between AM:AP and the true metabolizable energy (TME) values. This study showed that when ducks were fed high amylose-corn diets, they tend to have lower TME than those fed low amylose corn. In addition, Ma et al. (2020) reported that AM:AP higher than 0.35 reduced starch digestibility. Similar responses were observed in the studies presented herein for average corn kernel hardness, but an opposite effect for hard corn kernel was observed. Independent of dietary treatments, our AM:AP ranged from 0.24 to 0.38 (Figure 3, Panel A). A recent experiment (Huart et al., 2018) did not detect differences in AMEn due to drying temperatures when using flint-dent corn harvested between 29 and 36% of moisture content and dried at 54, 90, and 130°C. Therefore, responses on AMEn might change due to kernel hardness, the interactive effects with CP endosperm matrix, and its digestibility that could be affected by drying temperature and initial moisture content, as previous researchers have stated (Odjo et al., 2012; Huart et al., 2018).

In summary, results obtained in the current studies suggested that supplementing 80 kilo-Novo alpha-amylase units/kg resulted in beneficial effects for broiler live performance, energy utilization, and starch total tract digestibility. The mode of action of exogenous amylase is probably through decreasing endogenous nutrient losses, mainly amino acids that constitute an important part of the gut maintenance costs (Ritz et al., 1995; Gracia et al., 2003). Nevertheless, we observed amylase supplementation to be interactive with kernel hardness and drying temperature, as has been previously presumed (Amerah et al., 2017). Kernel hardness could be determined by near-infrared spectroscopy (Williams et al., 2009), showing the potential of this tool to assess corn vitreousness in a practical, economical, and time-efficient manner. Consequently, decisions about supplementation of exogenous amylase or other enzymes for broiler diets could be addressed more strategically.

The improvement observed on the FCR at 40 d for broilers fed the average hardness corn kernel dried at 80, and 120°C (Figure 1) was related to a higher damaged starch at these levels (Table 1). In contrast, for corn with the harder kernel, a higher damaged starch was observed when this hybrid was dried at 35°C (Table 1), which improved FCR at 40 d (Figure 3, Panel B). The gelatinization of starch and changes on damaged starch varies with kernel hardness, and more damaged starch negatively impacted FCR in young chickens (16 d). In comparison, it was positive for older broilers (40 d). Kernel hardness influenced the AM:AP and damaged starch in the grain. Only for hard corn kernel, both amylose content (r = 0.39) and damaged starch (r = −0.38) affected (P < 0.001) the final FCR at 40 d (Figure 3, Panel B). Corn with a lower proportion of amylose within the starch, AM:AP below 0.33 (0.24–0.33), damaged starch higher than 2.69%, vitreousness below 62.7%, protein solubility lower than 23.3% was associated with improved final FCR. These limits were estimated using a partition method in JMP 14. Ma et al. (2020) fed diets containing different AM:AP (0.11, 0.23, 0.35, and 0.47) and concluded that dietary 0.23 to 0.34 AM:AP promotes the best performance for broilers.

In conclusion, kernel hardness and drying temperature interact modifying the AM:AP and damaged starch, among other starch properties, which were pivotal factors to explain responses observed on dgw, Sgw, PDI during feed processing, chicken CP, and starch digestibility that affect AMEn and live performance. The beneficial effects of amylase supplementation observed on live performance, and nutrient digestibility were evidently dependent on corn kernel hardness and drying temperature, especially for broilers fed corn with average hardness. These studies revealed the importance of vitreousness, AM:AP, and damaged starch as corn quality parameters when deciding about amylase inclusion in broiler diets.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank AB Vista Feed Ingredients (Plantation, Fl) and Evonik Nutrition & Care (Hanau, Hessen, Germany) for their help with the analysis of nutrient content in feed ingredients and feed. Furthermore, thanks to all staff and students of the Prestage Department of Poultry Science at North Carolina State University. This research received funding from DSM Nutritional Products.

DISCLOSURES

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Footnotes

Mention of trade names or commercial products in this publication is solely for the purpose of providing specific information and does not imply recommendation or endorsement by North Carolina State University.

REFERENCES

- Almeida F. Univ. Illinois; Urbana-Champaign: 2013. Effects of the Maillard reactions on chemical composition and amino acid digestibility of feed ingredients and on pig growth performance. PhD Diss. [Google Scholar]

- Amerah A.M., Romero L.F., Awati A., Ravindran V. Effect of exogenous xylanase, amylase, and protease as single or combined activities on nutrient digestibility and growth performance of broilers fed corn/soy diets. Poult. Sci. 2017;96:807–816. doi: 10.3382/ps/pew297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AOAC INTERNATIONAL . 19th ed. AOAC International; Gaithersburg, MD: 2012. Official Methods of Analysis. [Google Scholar]

- AOAC Official Method 990.03 . Pages 30-31 in Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC International. 18th ed. Rev. 1. AOAC International; Gaithersburg, MD: 2006. Chapter 4 Protein (Crude) in animal feed, combustion method. [Google Scholar]

- Aviagen Ross Nutrition Specifications. Aviagen. 2019 http://es.aviagen.com/assets/Tech_Center/Ross_Broiler/RossBroilerNutritionSpecs2019-EN.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Barrier-Guillot B., Zuprizal C.Jondreville, Chagneau A.M., Larbier M., Leuillet M. Effect of heat drying temperature on the nutritive value of corn in chickens and pigs. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 1993;41:149–159. [Google Scholar]

- Sorbara Berti, O. J., Murakami A.E., Nakage E.S., Piracés F., Potença A., Holanda Guerra R.L. Enzymatic programs for broilers. Braz. Arch. Biol. Technol. 2009;52:233–240. [Google Scholar]

- Bhuiyan M.M., Islam A.F., Iji P.A. Variation in nutrient composition and structure of high-moisture maize dried at different temperatures. South Afr. J. Anim. Sci. 2010;40:190–197. [Google Scholar]

- Córdova-Noboa H.A., Oviedo-Rondón E.O., Ortiz A., Matta Y., Hoyos S., Buitrago G., Martinez J.D., Yanquen J., Chico M., San Martin V.E., Farenholz A., Ospina-Rojas I.C., Peñuela L. Effects of corn kernel hardness and grain drying temperature on particle size and pellet durability when grinding using a roller mill or hammermill. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2021;271 [Google Scholar]

- Córdova-Noboa, H. A., E. O. Oviedo-Rondón, A. Ortiz, Y. Matta, S. Hoyos, G. Buitrago, J. D. Martinez, J. Yanquen, L. Peñuela, J. O. Berti Sorbara, and A. J. Cowieson. 2020b. Corn drying temperature, particle size, and amylase supplementation influence growth performance, digestive tract development, and nutrient utilization of broilers. Poult. Sci. 99:5681–5696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Cowieson A.J. Factors that affect the nutritional value of maize for broilers. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2005;119:293–305. [Google Scholar]

- Cowieson A.J. Strategic selection of enzymes. Japan Poult. Sci. 2010;47:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Cowieson A., Pierson E., D'Alfonso T., Adeola O. Phytase, carbohydrase and protease have an additive effect on the performance of broilers fell on nutritionally marginal diets. Poult. Sci. 2005;84:84. doi: 10.1093/ps/84.12.1860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowieson A.J., Ravindran V. Effect of exogenous enzymes in maize-based diets varying in nutrient density for young broilers: growth performance and digestibility of energy, minerals and amino acids. Br. Poult. Sci. 2008;49:37–44. doi: 10.1080/00071660701812989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croom W.J., Brake J., Coles A., Havenstein G.B., Christensen V.L. Is intestinal absorption capacity rate-limiting for performance in poultry? J. Appl. Poult. Res. 1999;8:242–252. [Google Scholar]

- Gracia M.I., Araníbar M.J., Lázaro R., Medel P., Mateos G.G. α-Amylase supplementation of broiler diets based on corn. Poult. Sci. 2003;82:436–442. doi: 10.1093/ps/82.3.436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill F.W., Anderson D.L. Comparison of metabolizable energy and productive energy determinations with growing chicks. J. Nutr. 1958;64:587–603. doi: 10.1093/jn/64.4.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann T., Engling A.C., Martens S., Steinhofel O., Henle T. Quantification of Maillard reaction products in animal feed. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2020;246:253–256. [Google Scholar]

- Huart F., Malumba P., Odjo S., Al-Izzi W., Béra F., Beckers Y. In vitro and in vivo assessment of the effect of initial moisture content and drying temperature on the feeding value of maize grain. Br. Poult. Sci. 2018;59:452–462. doi: 10.1080/00071668.2018.1477253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iji P.A., Khumalo K., Slippers S., Gous R.M. Intestinal function and body growth of broiler chickens on diets based on maize dried at different temperatures and supplemented with a microbial enzyme. Reprod. Nutr. Dev. 2003;43:77–90. doi: 10.1051/rnd:2003007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Grains Council . IGC; London, UK: 2018. World Grain Statistics.https://www.igc.int/en/markets/marketinfo-sd.aspx Accessed Oct. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Jayas D.S., White N.D.G. Storage and drying of grain in Canada: low cost approaches. Food Control. 2003;14:255–261. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Z., Zhou Y., Lu F., Han Z., Wang T. Effects of different levels of supplementary alpha-amylase on digestive enzyme activities and pancreatic amylase mRNA expression of young broilers. Asian-Australasian J. Anim. Sci. 2008;21:97–102. [Google Scholar]

- Józefiak D., Rutkowski A., Martin S.A. Carbohydrate fermentation in the avian ceca: a review. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2004;113:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Kaczmarek S.A., Cowieson A.J., Józefiak D., Rutkowski A. Effect of maize endosperm hardness, drying temperature and microbial enzyme supplementation on the performance of broiler chickens. Anim. Prod. Sci. 2014;54:956–965. [Google Scholar]

- Kaczmarek S.A., Rogiewicz A., Mogielnicka M., Rutkowski A., Jones R.O., Slominski B.A. The effect of protease, amylase, and nonstarch polysaccharide-degrading enzyme supplementation on nutrient utilization and growth performance of broiler chickens fed corn-soybean meal-based diets. Poult. Sci. 2014;93:1745–1753. doi: 10.3382/ps.2013-03739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein R. Context Products Ltd; Leicestershire, UK: 2013. Chicken Nutrition: A Guide for Nutritionists and Poultry Professionals. [Google Scholar]

- Kljak K., Duvnjak M., Grbeša D. Contribution of zein content and starch characteristics to vitreousness of commercial maize hybrids. J. Cereal Sci. 2018;80:57–62. [Google Scholar]

- Kljak K., Grbeša D., Aleuš D. Relationships between kernel physical properties and zein content in corn hybrids. Bull. Univ. Agric. Sci. Vet. Med. Cluj-Napoca - Agric. 2011;68:188–194. [Google Scholar]

- Kong C., Adeola O. Evaluation of amino acid and energy utilization in feedstuff for swine and poultry diets. Asian-Australasian J. Anim. Sci. 2014;27:917–925. doi: 10.5713/ajas.2014.r.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krogdahl A., Sell J.L. Influence of age on lipase, amylase, and protease activities in pancreatic tissue and intestinal contents of young turkeys. Poult. Sci. 1989;68:1561–1568. doi: 10.3382/ps.0681561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larbier M., Guillaume J., Calet C. Mesure de la lysine libre du muscle chez le poulet. Ann. Zootech. 1971;20:653–661. [Google Scholar]

- Lasek O., Barteczko J., Borowiec F., Smulikowska S., Augustyn R. The nutritive value of maize cultivars for broiler chickens. J. Anim. Feed Sci. 2012;21:345–360. [Google Scholar]

- Li Q., Shi M., Shi C., Liu D., Piao X., Li D., Lai C. Effect of variety and drying method on the nutritive value of corn for growing pigs. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2014;5:1–7. doi: 10.1186/2049-1891-5-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J., Yang T., Yan Z., Zhao L., Yao L., Chen J., Chen Q., Tan B., Li T., Yin J., Yin Y. Effects of dietary amylose/amylopectin ratio and amylase on growth performance, energy and starch digestibility, and digestive enzymes in broilers. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Ntr. 2020;104:928–935. doi: 10.1111/jpn.13338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malumba P., Odjo S., Boudry C., Danthine S., Bindelle J., Beckers Y., Béra F. Physicochemical characterization and in vitro assessment of the nutritive value of starch yield from corn dried at different temperatures. Starch/Staerke. 2014;66:738–748. [Google Scholar]

- Malumba P., Vanderghem C., Deroanne C., Béra F. Influence of drying temperature on the solubility, the purity of isolates and the electrophoretic patterns of corn proteins. Food Chem. 2008;111:564–572. [Google Scholar]

- Malumba P., Janas S., Masimango T., Sindic M., Deroanne C., Béra F. Influence of drying temperature on the wet-milling performance and the proteins solubility indexes of corn kernels. J. Food Eng. 2009;95:393–399. [Google Scholar]

- Martins S., Jongen W., Van Boekel M. A review of maillard reaction in food and implications to kinetic modelling. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2001;11:364–373. [Google Scholar]

- Moore S.M., Stalder K.J., Beitz D.C., Stahl C.H., Fithian W.A., Bregendahl K. The correlation of chemical and physical corn kernel traits with production performance in broiler chickens and laying hens. J. Anim. Sci. 2008;87:665–676. doi: 10.3382/ps.2007-00184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers W.D., Ludden P.A., Nayigihugu V., Hess B.W. Technical Note : a procedure for the preparation and quantitative analysis of samples for titanium dioxide. J. Anim. Sci. 2004;82:179–183. doi: 10.2527/2004.821179x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nir I., Nitzan Z., Mahagna M. Comparative growth and development of the digestive organs and of some enzymes in broiler and egg type chicks after hatching. Br. Poult. Sci. 1993;34:523–532. doi: 10.1080/00071669308417607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]