Abstract

Titanium dioxide nanoparticles (TiO2 NPs) have been widely used in food, medical, and other fields; their reproductive toxicity has been reported in numerous studies. However, the relevant toxicity mechanism still requires further exploration. In this paper, the effect of oral exposure to 500 mg/kg TiO2 NPs (anatase and rutile) in adult male SD rats was studied over 3 and 7 days. Results showed that the total sperm count and testosterone level of 7 days of exposure in serum decreased in the experimental group. Testicular tissue lesions, such as disappearance of Leydig cells, disorder of arrangement of spermatogenic cells in the lumen of convoluted seminiferous tubules, and disorder of arrangement of germ cells, were observed. Meanwhile, the expression of steroidogenic acute regulatory (StAR; the key factors of testosterone synthesis), MAPK (ERK1/2), and phosphorylated ERK1/2 in testes of SD rats after exposure to TiO2 NPs for 7 days decreased, while the malondialdehyde content increased and superoxide dismutase activity decreased in serum. The present study showed that TiO2 NPs could cause reproductive toxicity. Notably, anatase is more toxic than rutile. In addition, exposure to 500 mg/kg TiO2 NPs for 7 days inhibited testosterone synthesis in male rat, which may be related to the reactive oxygen species (ROS)-MAPK (ERK1/2)-StAR signal pathway. Warning that the use of TiO2 NPs should be regulated.

Keywords: titanium dioxide nanoparticle, smale reproductive toxicity, reactive oxygen species, ERK1/2, testosterone synthesis

Highlights

Titanium dioxide nanoparticles (TiO2 NPs) induced reproductive toxicity in the SD rats.

Inhibition of MAPK (ERK1/2) expression of ROS induced by TiO2 NPs.

Inhibition of testosterone synthesis induced by oral TiO2 NPs is associated with ROS-MAPK(ERK1/2)-StAR signaling pathway in SD rats.

Introduction

In recent years, nanomaterials have been widely used in various fields, especially in food additives and food contact materials [1]. Nano-silver, titanium dioxide, and silicon dioxide are the most commonly mentioned nanomaterials in literature [2]. Titanium dioxide nanoparticles (TiO2 NPs) is one of the most widely used nanomaterials in varying fields, including medicine [3], agriculture [4], bacteriostasis [5], wastewater treatment [6], personal care products [7], cosmetics, sunscreen, toothpaste, paint, and food [8]. TiO2 NPs are inevitably released into the environment due to widespread use, which will harm individual organisms and ecosystems. TiO2 NPs mainly exist in three different natural crystal forms, namely, anatase, rutile, and brookite [9]. Anatase and rutile are more commonly used than brookite; moreover, studies have reported that the surface activities of anatase and rutile differ [10]. Thus, these two kinds of crystal materials were selected for this study. Given the wide range of uses and special physical properties (small size), TiO2 NPs are transferred to the human body through inhalation, environmental intake, and medical applications (skin exposure) [11, 12] and then enter different organs through blood circulation, such as the heart, liver, lung, brain, and testis [13, 14]. According to previous studies, after continuous exposure for 14 days, the deposition of TiO2 NPs in various organs of mice is in the following order: liver > kidney > spleen > lung > brain > heart [15]. TiO2 NPs enter the testis through the blood–testis barrier (BTB) due to their small size and then migrate to the testicular microenvironment composed of Sertoli cells, sperm cells, and Leydig cells (LCs). They then destroy the normal structure of the testis [16, 17] and inhibit testosterone production; lead to a decline in sperm quality; and cause a decrease in LCs and sperm count, sperm motility, and other male fertility problems [18, 19]. However, studies on the mechanism of TiO2 NPs inhibiting testosterone production are few.

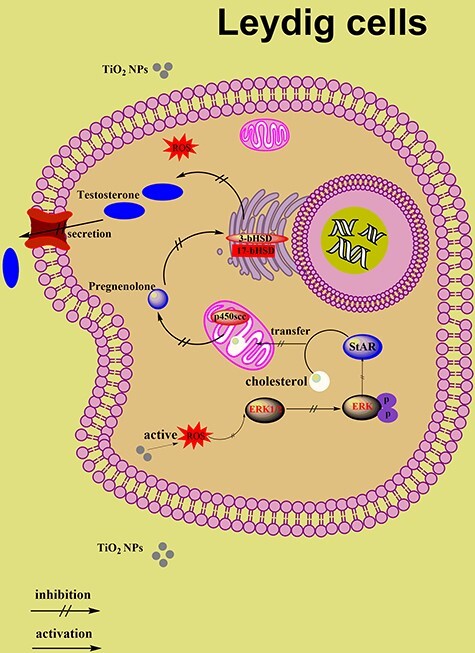

The process of testosterone synthesis has been reported [20]. First, cholesterol is carried from the outer membrane of the mitochondria to the intima through steroidogenic acute regulatory (StAR), and its side chain is cleaved and converted into pregnenolone by cytochrome P450 family 11 (Cyp11a1) in LCs [21]. Pregnenolone is transported to the smooth endoplasmic reticulum in the cytoplasm and forms testosterone through the reaction catalyzed by 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (3βHSD) and 17βHSD [22, 23]. StAR is an acute regulatory protein [24], which regulates the transfer of cholesterol to the mitochondria. Otherwise, it is considered a rate-limiting step in testosterone synthesis and is regulated by extracellular regulated protein kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2) [25, 26]. More specifically, the upstream of StAR gene expression is regulated by phosphorylated ERK1/2 (Only phosphorylated ERK1/2 is active) [27]. ERK1/2, a member of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) family [28], has been shown to promote the transcription of the StAR gene and may be involved in testosterone synthesis [29, 30]. In addition, previous studies have shown that MAPK is activated by reactive oxygen species (ROS) [31, 32], which may affect the normal expression of MAPK (ERK1/2) in the testis and affect testosterone synthesis. Notably, a large number of studies proved that the entry of TiO2 NPs into the body may break the oxidation balance and generate ROS, resulting in a series of adverse effects, such as hepatotoxicity, reproductive toxicity, and genotoxicity [33, 34].

Here, we hypothesized that oral exposure to TiO2 NPs in male rats may lead to the production of ROS and further activation of MAPK (ERK1/2) by ROS. ERK and StAR regulate each other [35]. Interference with the expression of ERK1/2 will lead to the inability of StAR to transport cholesterol to the mitochondria normally, resulting in the inhibition of testosterone synthesis in the testis.

In this study, the adverse effects of anatase and rutile TiO2 NPs on male reproductive function were evaluated by analyzing testicular histopathology, sperm count, and testosterone levels. The potential mechanism underlying the decreased testosterone synthesis pathway induced by TiO2 NPs was investigated through 3 and 7 days of oral exposure in male rats.

Materials and Methods

Characterization of TiO2 NPs

TiO2 NPs of anatase and rutile types (40 nm ± 5 nm) were obtained from Aladdin industrial Corporation (Shanghai, China). The size of TiO2 NPs was characterized by emission scanning electron microscopy (SEM) (JSM 6701F, JEOL Ltd, USA) after being dispersed by anhydrous ethanol and more than 100 nanoparticles sizes were measured by Image J software.

Animals treatment

Approximately 8-week-old adult male Sprague Dawley (SD) rats were purchased from the experimental animal center of Nanchang University (Nanchang, China). And then, the animals were kept in non-toxic and harmless cages in a room with a temperature at 22 ± 2°C and humidity of 45 ± 5% and 12 h cycle of dark and light. Animals have free access to clean drinking water and commercial food. Before the end of the experiment, clean the cage every 3 days in order to maintain a comfortable environment. The animal trials program was carried out with reference to the guidelines for experimental animal welfare and approved by the animal care review committee (approval No. 0064257), Nanchang University.

Adapting for a week, the animals were randomly divided into control, anatase, and rutile groups (n = 5). The study of Ali showed that exposure to 500 mg/kg TiO2 NPs had oxidative damage in mice [36]. The rats in the experimental group were oral administered with 500 mg/kg TiO2 NPs for 3 and 7 days in this study. Meanwhile, the control group was fed with the same amount of solvent. The clinical symptoms of rats were observed every day during the experiment. Twenty-four hours after the last administration, serum and testicular tissue samples of rats were obtained and stored in the refrigerator at −80°C.

Sperm counts

The assessment of testicular sperm count was adopted from the studies reported by Kisin et al. [37], and we made minor modifications. The isolated left epididymis was completely cut up and then put into 1 ml of saline and incubated at 37°C for 15 min in order to fully dissociate the sperm. 200 μl sperm sample was killed with hot water at 90°C, and then 10 μl sample was put into the blood cell counter to observe and determine the sperm count under light microscope (Nikon eclipse Ti). All studies were in triplicate.

Assay for testosterone in serum

The effects of TiO2 NPs exposure over 3 and 7 days on the testosterone levels in serum were evaluated. According to the instructions provided by the manufacturer, we used ELISA kit (Item No. 582701) to determine the content of testosterone in serum samples. Absorbance was recorded between 405 and 420 nm with the microplate reader (Thermo Scientific, USA). The plate should be read when the absorbance of the B0 wells is in the range of 0.3–1.0 A.U (blank subtracted). The accurate testosterone content was calculated according to the standard curve.

Histopathology examination

Histopathological damage of testis exposed to TiO2 NPs was evaluated. The testes of rat were extracted and stored in Bonn fixed solution for 24 h, then 75% alcohol was replaced for storage. The paraffin blocks were obtained by embedding the sample in paraffin after dehydration of ethanol and transparency of xylene, which were cut at 5 μm thickness and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. The stained sections were fixed on glass slides and magnified 200 and 400 times, respectively, under optical microscope to observe the seminiferous tubules, lumen, interstitial area, and germ cells.

Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction

According to Axyprep TM Multisource Total RNA Miniprep kit instructions (Takara Bio Inc.), total RNA was extracted from testis and reverse transcribed into cDNA. The primers were designed with NCBI Primer and Oligo Primer Analysis Software version7.0 (Molecular Biology Insights, Inc.; DBA Oligo, Inc.). And then, the primers were synthesized by Qingke Biology Co, Ltd (Shanghai, China). In the AriaMx Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) system (MY 19435252), we used the three-step method, that is 1 min at 95°C followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 5 s, 59°C for 60s, 72°C for 30 s. The relative quantification of mRNA was calculated by 2−△△Ct method and GAPDH was used as the internal reference gene.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) analysis

Paraffin sections of testicular tissue were dewaxed with xylene and ethanol and then placed in citric acid antigen repair buffer (pH 6.0) to repair antigens. The sections were incubated in 3% hydrogen peroxide and kept away from light at room temperature for 25 min in order to block the endogenous peroxidase. Next, add 3% BSA covering tissue and seal at room temperature for 30 min. After dripping primary antibody against StAR and pERK1/2 (1:500) and incubating overnight at 4°C, and adding corresponding secondary antibody (HRP marked, Servicebio, GB23303) for 50 min at room temperature. Finally, the sections were developed with diaminobenzidine (DAB). IHC was quantified with reference to the previous method and quantified with Image J software. The results obtained were converted into scores using [∑Pi(i + 1)] formula (i: staining intensity score; Pi: percentage of stained contribution, negative: 0, low positive: 1, positive: 2, high positive: 3).

Detection of superoxide dismutase, catalase and malondialdehyde

The activities of superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase (CAT) as well as the content of malondialdehyde (MDA) in serum were measured according to the instructions of the kit manufacturer, which purchased from Jiancheng Bio-tech Co. Ltd (Nanjing, China).

Statistical analysis

All the reported data were displayed with mean ± standard deviation (SD), which was analyzed using the SPSS (version 22) software. Differences between groups were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance. Significant differences were expressed by * (*P < 0.05,**P < 0.01,***P < 0.001). Specially, at least three independent parallel experiments were conducted in each group to ensure the authenticity of the reported data.

Results

Characterization of TiO2 NPs

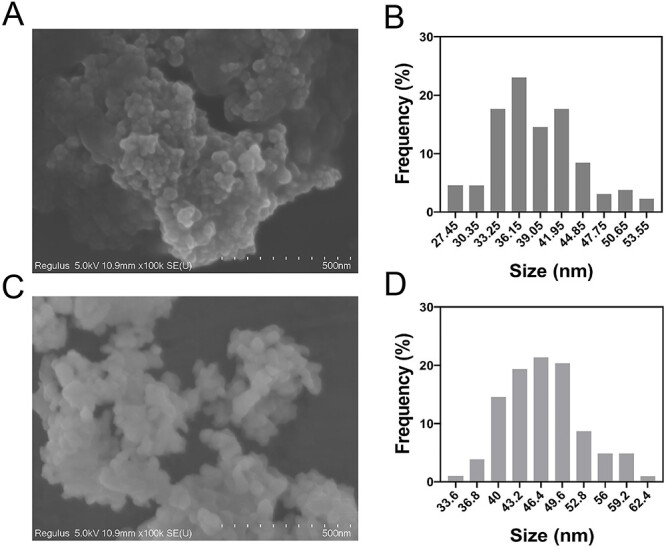

To explore the dispersion of nanoparticles in solution and the true particle size and shape, this study was observed by SEM. The results showed that the two types of TiO2 NPs were spherical with an average diameter of anatase of 37 nm and rutile 46 nm (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Characterization of TiO2 NPs. (A, C) SEM image of anatase and rutile TiO2 NPs. (B, D) The frequency of the size distribution of anatase and rutile TiO2 NPs.

Sperm counts

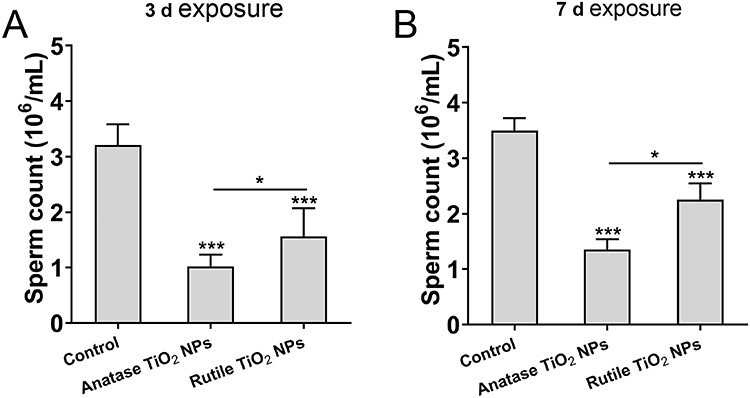

After exposure to different crystalline TiO2 NPs for 3 and 7 days, the spermatozoa of the left epididymis were collected and counted with the blood cell count plate. Compared with the control group, the total sperm count of the anatase and rutile groups after oral administration for 3 (Fig. 2A) and 7 days (Fig. 2B) decreased significantly (P < 0.001). In addition, the total sperm count of the anatase group was significantly lower than that of the rutile group (P < 0.05). The results showed that acute exposure to different crystal forms of TiO2 NPs had adverse effects on sperm survival in the testes of SD male rats, and the effect of anatase was greater than that of rutile.

Figure 2.

The number of sperms in the left epididymis of male rat after oral administration of 40 nm TiO2 NPs. The data are presented in the form of sperm per milliliter of saline. (A) 3-day exposure, (B) 7-day exposure. Data are expressed as mean ± SD. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001 compared with control.

Histopathological evaluation

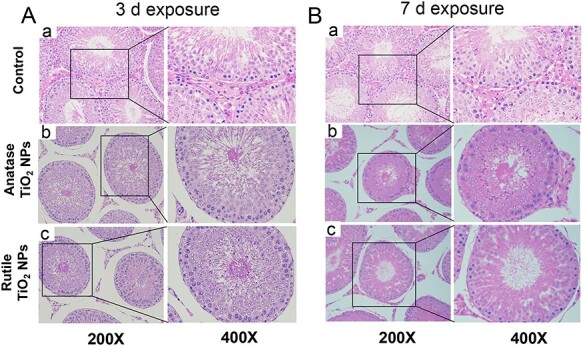

The histopathological evaluations of the testicular sections and histomorphology of the control group revealed normal findings. The seminiferous tubules were closely connected and arranged neatly; the interstitial region was intact; germ cells were abundant in the control group; and spermatogonia, spermatocytes, and sperm cells were clearly observed (Fig. 3A-a and B-a). In the anatase group exposed for 3 (Fig. 3A-b) and 7 days (Fig. 3B-b), the number of LCs disappeared; spermatogenic disorder appeared in the lumen of seminiferous tubules; interestingly, germ cells were randomly arranged, the number decreased, and spermatocytes were exfoliated and vacuolated. The pathological condition in the rutile group was similar to that in the anatase group, but Fig. 3A-c and B-c shows that the pathological condition was not poor. Therefore, acute exposure to TiO2 NPs could cause damage to the testis of animals and interfere with the production of spermatozoa.

Figure 3.

Light microscopy of cross sections of hematoxylin and eosin-stained testes from male rat. (A) 3-day exposure, (B) 7-day exposure.

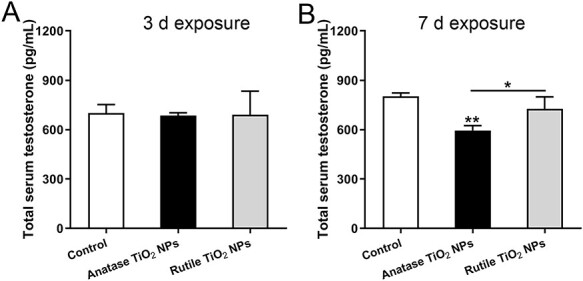

Testosterone levels

The change in the testosterone level determined by an ELISA kit is shown in Fig. 4. The results showed that the testosterone levels in serum exposed for 7 days were lower in the treatment group than in the control group, and the anatase levels were lower in the treatment group than in the rutile group. These findings indicated that acute exposure to different crystal forms of TiO2 NPs could affect the synthesis of testosterone, and the effect of anatase was more serious than that of rutile.

Figure 4.

Testosterone concentration in male rat serum detected by ELISA. (A) 3-day exposure (B) 7-day exposure. Data are expressed as mean ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 compared with control.

Change in relative gene quantification in testis

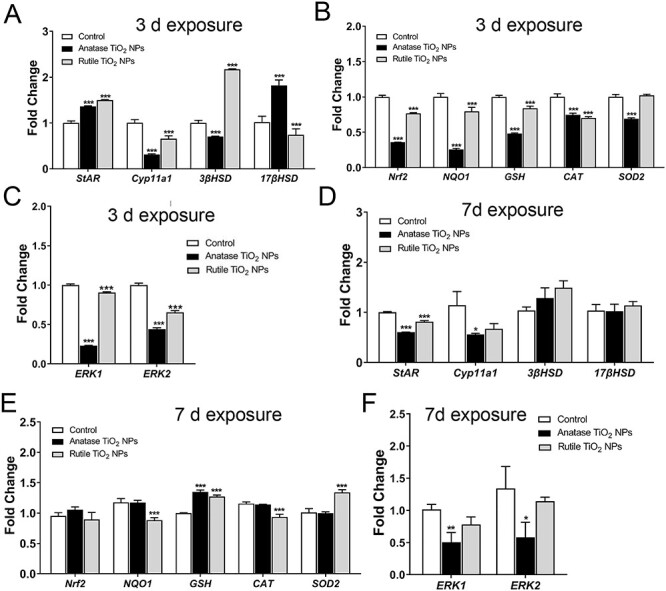

In this study, the changes in gene quantification related to ROS, MAPK (ERK1/2), and testosterone production were assessed by RT-qPCR. The primer information of related genes is shown in Table 1. In the 3-day exposure group, the expression levels of ROS-associated gene of nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2), NAD(P)H quinone dehydrogenase 1 (NQO1), glutathione (GSH), CAT, superoxide dismutase 2 (SOD2), and MAPK (ERK1/2) were significantly downregulated in the experimental groups compared with the control groups. The testosterone production-associated gene of StAR was markedly upregulated in the experimental groups. By contrast, Cyp11a1 was markedly downregulated. 3βHSD was significantly downregulated in the anatase group and upregulated in the rutile group, whereas 17βHSD was significantly upregulated in the anatase group and downregulated in the rutile group. Similarly, in the 7-day exposure group, the ROS-associated gene of GSH was significantly upregulated, whereas HO-1 was downregulated in the experimental groups. CAT and NQO1 were downregulated in the rutile group, while Nrf2 showed no significant alteration. MAPK (ERK1/2) was significantly downregulated in the anatase groups. The testosterone production-associated gene of StAR was significantly downregulated in the experimental groups. Cyp11a1 was significantly downregulated in the anatase groups, while 3βHSD and 17βHSD showed no significant alteration (Fig. 5).

Table 1.

Sequences of the primers used for quantitative real-time PCR

| Target gene | Forward primer (5′-3′) | Revere primer (3′-5′) |

|---|---|---|

| StAR | TCCTCGCTACGTTCAAGCTG | CGTCGAACTTGACCCATCCA |

| Cyp11a1 | TAGCTTTGCCATGGGTCGAG | AGTACCGGAAGTGGGTGGTA |

| 3βHSD | ACACGGCTTCTGTCATGGATT | CCAATAGGTTCTGGGTACCTTTC |

| 17βHSD | TGCTTGGGTTTGGCACATT | TCTCTCCAGGCACTGACGTA |

| ERK1 | AATGGAAGGGCTATGACCG | AGCTTGAGAGGGAGAGGGTT |

| ERK2 | ATGACCCAAGTGATGAGCCC | GAGCCCTTGTCCTGACCAATTT |

| Nrf2 | AGACAAACATTCAAGCCGAT | CTCTCCTGCGTATATCTCGAA |

| NQO1 | TTGCTTTCAGTTTTCGCCTT | CCCCTAATCTGACCTCGTTC |

| GSH | ATCCCACTGCGCTCATGACC | AGCCAGCCATCACCAAGCC |

| CAT | ATAGCCAGAAGAGAAACCCACA | CCTCTCCATTCGCATTAACCAG |

| SOD2 | ACTTGAAACGTGTAACTAGGC | CTTTCATACAATACACAGTCGG |

| GAPDH | TCCCTCAAGATTGTCAGCAA | AGATCCACAACGGATACATT |

Figure 5.

Gene expression of testosterone synthesis, ROS, and MAPK (ERK1/2) in testis. (A–C) 3-day exposure, (D–F) 7-day exposure. Data are expressed as mean ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 compared with control.

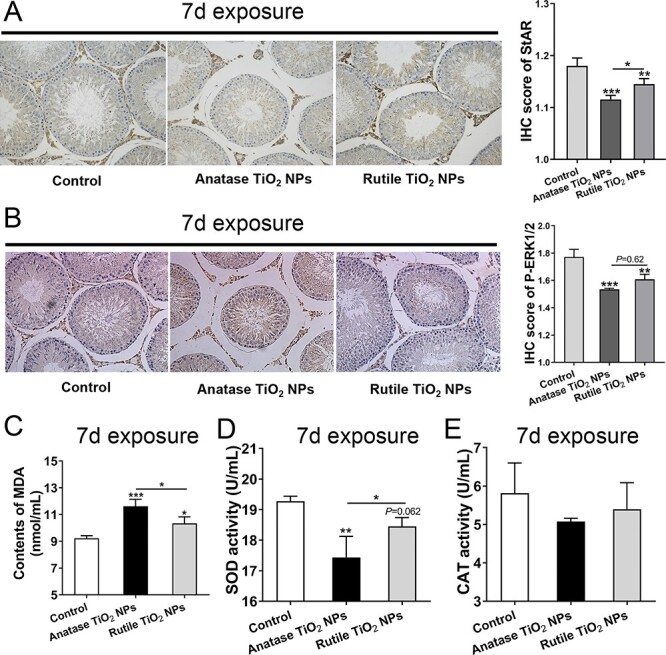

IHC analysis and ROS index determination

The results of IHC analysis of StAR and pERK1/2 in testes (Fig. 6A and B) showed that after 7 days of exposure to TiO2 NPs, the experimental group decreased significantly, and anatase was more obvious than rutile. In addition, the MDA content in serum of the experimental groups increased significantly, and the anatase group increased more significantly than the rutile group (Fig. 6C). MDA is one of the most important products of membrane lipid peroxide. SOD activity decreased significantly in the anatase group; a downward trend was observed in the rutile group compared with that in the control group, but the difference was insignificant (Fig. 6D). Moreover, there was no significant difference in CAT activity among the groups, but it was observed that there was a decreasing trend in the experimental group, especially in the anatase group (Fig. 6E). These results suggested that oral TiO2 NPs for 7 days could induce ROS production and inhibit ERK1/2 phosphorylation and StAR expression.

Figure 6.

IHC analysis and ROS index determination. (A, B) IHC analysis of StAR and pERK1/2. (C–E) ROS index determination of MDA, SOD, and CAT in serum. Data are expressed as mean ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P<0.01, ***P < 0.001 compared with control.

Discussion

TiO2 NPs inevitably enter the environment because they are widely used in different fields and enter the human body through different pathways, including oral administration, skin contact, and injections. Studies have shown that oral TiO2 NPs are toxic to rodents and accumulate significantly over time due to slow tissue elimination and repeated exposure, notwithstanding low oral bioavailability [13]. Complementally, Hu et al. believes that it is easier to detect only higher doses of TiO2 NPs with higher toxicity [38]. Male infertility is a global population health concern, and global rates of male infertility range from 2.5 to 12% [39]. Thus, studies on the reproductive toxicity caused by TiO2 NPs are crucial. Results of this study clearly proved that oral exposure to anatase and rutile TiO2 NPs (500 mg/kg) for 7 days decreased the content of testosterone in serum compared with the control group (Fig. 3). This finding was consistent with the results of Jia et al. [19], who reported that TiO2 NPs can inhibit the synthesis of testosterone. The main organ of testosterone synthesis is the testis. The results of our histopathological sections showed that the normal structure of the testis was destroyed, such as seminal cavity disorder and shedding and vacuolation of germ cells. Moreover, a large number of LCs disappeared (Fig. 3). Similar results were reported by Elnagar et al. [40]. LCs are the main sites of testosterone synthesis and secretion; they are mainly distributed in the loose connective tissue of seminiferous tubules [41, 42] and are responsible for the production of androgens to maintain normal male development and reproductive function [43, 44]. In addition, testosterone is the main component of androgen, which is transported to the target organs of the body and makes an important contribution to reproductive function by binding to receptors [45, 46]. Previous studies reported that TiO2 NPs directly trigger androgen imbalance, which results in estrogen imbalance, testicular dysfunction, and inhibition of spermatogenesis [17]. In this study, the sperm count also showed similar results; the total number of sperm in the experimental group decreased considerably compared with that in the control group (Fig. 2). In general, TiO2 NPs can cause testicular damage and affect testosterone levels. A decrease in testosterone levels can affect the testes and exacerbate abnormal testicular spermatogenesis. In other words, the reproductive dysfunction and decrease in serum testosterone level in male SD rats are closely related to TiO2 NPs.

The synthesis and secretion of testosterone are regulated by the expression of StAR, Cyp11a1, 3βHSD, 17βHSD, and other genes [47]. In short, cholesterol is transported from the outer membrane of the mitochondria to the inner membrane of the mitochondria through StAR and is bioconverted to pregnenolone by Cyp11a1, which is then catalyzed by 3βHSD and 17βHSD in the endoplasmic reticulum to produce testosterone [48]. StAR is considered a rate-limiting enzyme in the transport of cholesterol to the mitochondria, where its expression is regulated by ERK1/2, and testosterone synthesis is directly affected by it [21, 49]. In the present study, the results showed that anatase TiO2 NPs significantly downregulated the expression of the ERK1/2, StAR, and Cyp11a1 genes in the 7-day exposure group (Fig. 4E and F). Similar results were obtained by Jia et al. [19] through oral administration of anatase TiO2 NPs (10, 50, or 250 mg/kg) to mice. Interestingly, StAR was significantly upregulated (Fig. 4A) in the 3-day exposure group, which possibly contributed to the negative feedback regulation of the hormone synthesis pathway in short-term exposure.

ROS produced in the body has been proven to activate members of the MAPK family, which contains ERK1/2 [50]. RT-qPCR results showed that ROS-related genes in the testis changed significantly after exposure to TiO2 NPs. For example, after 3 days of exposure, the expression of the GSH, CAT, and SOD2 antioxidant genes was significantly downregulated (Fig. 5B). Meena et al. [51] injected 50 mg/kg TiO2 NPs (21 nm) intravenously in male Wistar rats; their results showed that antioxidant enzymes such as CAT, GSH, and SOD decreased significantly in the testis. In addition, the Nrf2 and NQO1 genes related to the antioxidant pathway were significantly downregulated. TiO2 NPs induced ROS production and damaged the antioxidant capacity in the body. The MDA content in serum increased while SOD activity decreased after 7 days of exposure (Fig. 6C and D). TiO2 NPs destroy the oxidative balance in the testes of SD rats, which may be the source of the inhibition of testosterone synthesis.

Thus, the small size of TiO2 NPs could reach the testis through the BTB and induce ROS production. ROS may directly lead to apoptosis, inhibit the expression of the ERK1/2 gene, and reduce the phosphorylation level of ERK1/2, interfering with the normal transcription of the StAR gene. Finally, the synthesis of testosterone was inhibited (Fig. 7). Frankly, this study chose a high dose of TiO2 NPs acute exposure to rats, which hardly reflect the exposure that animals will face in real scenarios. In that sense, it is meaningful to mention that these investigation provide experimental evidence for the potential risks of nanomaterials in daily use. However, it is necessary to study more realistic situations in future research, namely subchronic and chronic exposures, as well as low doses similar to what we could be exposed to with commercial nanotechnology-based products.

Figure 7.

Schematic diagram for the suppression of testosterone production by TiO2-NPs associated with ROS-MAPK(ERK1/2)-StAR signaling pathway. Acute oral exposure to high doses of TiO2 NPs in male rats would lead to the production of ROS and further activation of MAPK (ERK1/2) by ROS. ERK and StAR regulate each other, and interference with the expression of ERK1/2 will lead to the inability of StAR to transport cholesterol to the mitochondria normally, resulting in the inhibition of testosterone synthesis in the testis. (“↑” activation, “‡” inactivation, “P” phosphorylation)

Conclusion

The potential mechanism underlying oral exposure to different crystal forms of TiO2 NPs for 3 and 7 days on testosterone synthesis in male SD rats was explored. The results showed that exposure to TiO2 NPs was harmful to sperm production and inhibited the synthesis of testosterone. The destruction of testicular tissue was manifested by the disappearance of LCs and exfoliation and vacuolation of spermatogenic cells. In general, the results after exposure to anatase for 7 days were more significant than those after exposure to rutile. Thus, anatase led to greater toxicity than rutile, which may be attributed to the high surface activity of anatase [10]. RT-qPCR results showed that TiO2 NPs inhibited the expression of antioxidant enzyme genes and induced ROS production in rats, which activated MAPK (ERK1/2). The expression of ERK1/2 and StAR was downregulated, resulting in the inhibition of testosterone synthesis. ROS-MAPK (ERK1/2)-StAR is a potential pathway in which testosterone synthesis is inhibited. Moreover, the synthesis and secretion of testosterone are complex processes, and the compound dynamic route of TiO2 NPs inhibiting testosterone synthesis needs to be further studied.

Funding

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (81771658 and 81560537).

Conflict of interest statement

The author reports no conflicts of interest in this work.

Contributor Information

Shanji Liu, State Key Laboratory of Food Science and Technology, Nanchang University, Nanchang 330047, China.

Yizhou Tang, State Key Laboratory of Food Science and Technology, Nanchang University, Nanchang 330047, China.

Bolu Chen, State Key Laboratory of Food Science and Technology, Nanchang University, Nanchang 330047, China.

Yu Zhao, State Key Laboratory of Food Science and Technology, Nanchang University, Nanchang 330047, China.

Zoraida P Aguilar, Zystein, LLC., Fayetteville, AR 72704, USA.

Xueying Tao, State Key Laboratory of Food Science and Technology, Nanchang University, Nanchang 330047, China.

Hengyi Xu, State Key Laboratory of Food Science and Technology, Nanchang University, Nanchang 330047, China.

References

- 1.Zhang J-R. Research on application of nanomaterials in food packaging design. Adv Mater Sci Technol 2019;1:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peters RJ, Bouwmeester H, Gottardo S et al. Nanomaterials for products and application in agriculture, feed and food. Trends Food Sci Technol 2016;54:155–64. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Çeşmeli S, Biray Avci C. Application of titanium dioxide (TiO2) nanoparticles in cancer therapies. J Drug Target 2019;27:762–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rodríguez-González V, Terashima C, Fujishima A. Applications of photocatalytic titanium dioxide-based nanomaterials in sustainable agriculture. J Photochem Photobiol C 2019;40:49–67. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhu X, K Pathakoti, Hwang H. M. Green synthesis of titanium dioxide and zinc oxide nanoparticles and their usage for antimicrobial applications and environmental remediation. In: Shukla AK, Iravani S (eds.), Green Synthesis, Characterization and Applications of Nanoparticles. E-Publishing Inc, 2019, 223–263. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Song T, Li R, Li N, Gao Y. Research progress on the application of nanometer TiO2 photoelectrocatalysis technology in wastewater treatment. Sci Adv Mater 2019;11:158–65. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weir A, Westerhoff P, Fabricius L et al. Titanium dioxide nanoparticles in food and personal care products. Environ Sci Technol 2012;46:2242–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abdulla IT. Histological effects of titanium dioxide nanoparticles size 10 nm in mice testes. Sci J Univ Zakho 2017;5:158–61. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Uboldi C, Urbán P, Gilliland D et al. Role of the crystalline form of titanium dioxide nanoparticles: rutile, and not anatase, induces toxic effects in Balb/3T3 mouse fibroblasts. Toxicol in Vitro 2016;31:137–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Matteis V, Cascione M, Brunetti V et al. Toxicity assessment of anatase and rutile titanium dioxide nanoparticles: the role of degradation in different pH conditions and light exposure. Toxicol in Vitro 2016;37:201–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang X, Li W, Yang Z. Toxicology of nanosized titanium dioxide: an update. Arch Toxicol 2015;89:2207–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shakeel M, Jabeen F, Shabbir S et al. Toxicity of nano-titanium dioxide (TiO2-NP) through various routes of exposure: a review. Biol Trace Elem Res 2016;172:1–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heringa MB, Geraets L, van Eijkeren JCH et al. Risk assessment of titanium dioxide nanoparticles via oral exposure, including toxicokinetic considerations. Nanotoxicology 2016;10:1515–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hong F, Wang L. Nanosized titanium dioxide-induced premature ovarian failure is associated with abnormalities in serum parameters in female mice. Int J Nanomedicine 2018;13:2543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu H, Ma L, Zhao J et al. Biochemical toxicity of nano-anatase TiO2 particles in mice. Biol Trace Elem Res 2009;129:170–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hong F, Wang Y, Zhou Y et al. Exposure to TiO2 nanoparticles induces immunological dysfunction in mouse testitis. J Agric Food Chem 2016;64:346–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sharafutdinova L, Fedorova AM, Bashkatov SA et al. Structural and functional analysis of the spermatogenic epithelium in rats exposed to titanium dioxide nanoparticles. Bull Exp Biol Med 2018;166:279–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gao G, Ze Y, Zhao X et al. Titanium dioxide nanoparticle-induced testicular damage, spermatogenesis suppression, and gene expression alterations in male mice. J Hazard Mater 2013;258-259:133–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jia F, Sun Z, Yan X et al. Effect of pubertal nano-TiO2 exposure on testosterone synthesis and spermatogenesis in mice. Arch Toxicol 2014;88:781–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Slaunwhite WR Jr, Burgett MJ. In vitro testosterone synthesis by rat testicular tissue. Steroids 1965;6:721–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stocco DM. StAR protein and the regulation of steroid hormone biosynthesis. Annu Rev Physiol 2001;63:193–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoberman JM, Yesalis CE. The history of synthetic testosterone. Sci Am 1995;272:76–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Payne AH, Youngblood GL, Sha L et al. Hormonal regulation of steroidogenic enzyme gene expression in Leydig cells. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 1992;43:895–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leers-Sucheta S, Stocco DM, Azhar S. Down-regulation of steroidogenic acute regulatory (StAR) protein in rat Leydig cells: implications for regulation of testosterone production during aging. Mech Ageing Dev 1999;107:197–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Luo D-Y, Yang G, Liu JJ et al. Effects of varicocele on testosterone, apoptosis and expression of StAR mRNA in rat Leydig cells. Asian J Androl 2011;13:287–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martinat N, Crépieux P, Reiter E, Guillou F. Extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERK) 1, 2 are required for luteinizing hormone (LH)-induced steroidogenesis in primary Leydig cells and control steroidogenic acute regulatory (StAR) expression. Reprod Nutr Dev 2005;45:101–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Poderoso C, Converso DP, Maloberti P et al. A mitochondrial kinase complex is essential to mediate an ERK1/2-dependent phosphorylation of a key regulatory protein in steroid biosynthesis. PLoS One 2008;3:e1443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Seger R, Krebs EG. The MAPK signaling cascade. FASEB J 1995;9:726–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Seger R, Hanoch T, Rosenberg R et al. The ERK signaling cascade inhibits gonadotropin-stimulated steroidogenesis. J Biol Chem 2001;276:13957–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matzkin ME, Yamashita S, Ascoli M. The ERK1/2 pathway regulates testosterone synthesis by coordinately regulating the expression of steroidogenic genes in Leydig cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2013;370:130–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Son Y, Cheong YK, Kim NH et al. Mitogen-activated protein kinases and reactive oxygen species: how can ROS activate MAPK pathways? J Signal Transduct 2011;2011:1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang C, Li P, Xuan J et al. Cholesterol enhances colorectal cancer progression via ROS elevation and MAPK signaling pathway activation. Cell Physiol Biochem 2017;42:729–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Proquin H, Rodríguez-Ibarra C, Moonen CGJ et al. Titanium dioxide food additive (E171) induces ROS formation and genotoxicity: contribution of micro and nano-sized fractions. Mutagenesis 2017;32:139–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shukla RK, Kumar A, Gurbani D et al. TiO2nanoparticles induce oxidative DNA damage and apoptosis in human liver cells. Nanotoxicology 2013;7:48–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Castillo AF, Orlando U, Helfenberger KE et al. The role of mitochondrial fusion and StAR phosphorylation in the regulation of StAR activity and steroidogenesis. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2015;408:73–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ali SA, Rizk MZ, Hamed MA et al. Assessment of titanium dioxide nanoparticles toxicity via oral exposure in mice: effect of dose and particle size. Biomarkers 2019;24:492–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kisin ER, Yanamala N, Farcas MT et al. Abnormalities in the male reproductive system after exposure to diesel and biodiesel blend. Environ Mol Mutagen 2015;56:265–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hu H, Guo Q, Wang C et al. Titanium dioxide nanoparticles increase plasma glucose via reactive oxygen species-induced insulin resistance in mice. J Appl Toxicol 2015;35:1122–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Agarwal A, Mulgund A, Hamada A, Chyatte MR. A unique view on male infertility around the globe. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 2015;13:37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Elnagar AMB, Ibrahim A, Soliman AM. Histopathological effects of titanium dioxide nanoparticles and the possible protective role of N-acetylcysteine on the testes of male albino rats. Int J Fertil Steril 2018;12:249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kordić M, Tomić D, Soldo D et al. Reinke’s crystals in perivascular and peritubular Leydig cells of men with non-obstructive and obstructive azoospermia: a retrospective case-control study. Croat Med J 2019;60:158–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ilacqua A, Francomano D, Aversa A. The physiology of the testis. In: Belfiore A, Leroith D (eds.), Principles of Endocrinology and Hormone Action. Italy: S-Publishing Inc, 2017, 1–38. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Payne AH, Youngblood GL. Regulation of expression of steroidogenic enzymes in Leydig cells. Biol Reprod 1995;52: 217–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sharpe R, Maddocks S, Kerr J. Cell-cell interactions in the control of spermatogenesis as studied using Leydig cell destruction and testosterone replacement. Am J Anat 1990;188:3–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dohle G, Smit M, Weber R. Androgens and male fertility. World J Urol 2003;21:341–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Elias M. Serum cortisol, testosterone, and testosterone-binding globulin responses to competitive fighting in human males. Aggress Behav 1981;7:215–24. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang L, Cui S. Effects of daidzein on testosterone synthesis and secretion in cultured mouse Leydig cells. Asian Australas J Anim Sci 2009;22:618–25. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hall PF, Osawa S, Mrotek J. The influence of calmodulin on steroid synthesis in Leydig cells from rat testis. Endocrinology 1981;109:1677–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang H, Wang Q, Zhao XF et al. Cypermethrin exposure during puberty disrupts testosterone synthesis via downregulating StAR in mouse testes. Arch Toxicol 2010;84:53–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Han A, Zou L, Gan X et al. ROS generation and MAPKs activation contribute to the Ni-induced testosterone synthesis disturbance in rat Leydig cells. Toxicol Lett 2018;290:36–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Meena R, Kajal K, Paulraj R. Cytotoxic and genotoxic effects of titanium dioxide nanoparticles in testicular cells of male Wistar rat. Appl Biochem Biotechnol 2015;175:825–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]