Abstract

Background:

Reactivation of human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6) after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant (HCT) is associated with neurologic complications, but the impact of donor and/or recipient inherited chromosomally integrated HHV-6 (iciHHV-6) on post-HCT central nervous system (CNS) symptoms, diagnostic and therapeutic interventions is not well understood.

Objective:

The aims of the study were 1) to compare the cumulative incidence of CNS symptoms in the first 100 days following allogeneic HCT among patients with donor and/or recipient iciHHV-6 (iciHHV-6pos) to that of patients with neither donor nor recipient iciHHV-6 (iciHHV-6neg) and 2) to assess the role of HHV-6 detection in driving potentially unnecessary interventions in iciHHV-6pos patients.

Study Design:

We performed a retrospective matched cohort study of 87 iciHHV-6pos and 174 iciHHV-6neg allogeneic HCT recipients. HHV-6 testing was performed at the discretion of healthcare providers, who were unaware of iciHHV-6 status.

Results:

The cumulative incidence of CNS symptoms was similar in iciHHV-6pos (N=37, 43%) and iciHHV-6neg HCT recipients (N=81, 47%; P=0.63). HHV-6 plasma testing was performed in similar proportions of iciHHV-6pos (N=6, 7% ) and iciHHV-6neg (9%) and was detected in all tested iciHHV-6pos and 2 (13%) iciHHV-6neg HCTs. This resulted in more frequent HHV-6-targeted antiviral therapy after iciHHV-6pos HCT (OR, 12.8; 95% CI 1.5-108.2) with associated side effects. HHV-6 plasma detection in two iciHHV6pos patients without active CNS symptoms prompted unnecessary lumbar punctures.

Conclusions:

The cumulative incidence of CNS symptoms was similar after allogeneic HCT involving recipients or donors with and without iciHHV-6. Misattribution of HHV-6 detection as infection after iciHHV-6pos HCT may lead to unnecessary interventions. Testing for iciHHV-6 may improve patient management.

Keywords: human herpes virus-6 (HHV-6), inherited chromosomally integrated HHV-6 (iciHHV-6), hematopoietic cell transplant, immunocompromised

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6) is a double-stranded DNA herpesvirus that infects most people during childhood1. There are two distinct species, HHV-6A and HHV-6B. HHV-6B is a recognized pathogen that causes exanthema subitem during primary infection.2 Like other herpesviruses, HHV-6 establishes chronic latency, and reactivation can cause disease in severely immunocompromised hosts.3, 4 HHV-6B reactivation occurs in 30 to 50% of allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant (HCT) recipients and causes a range of central nervous system (CNS) symptoms, the most severe of which is limbic encephalitis.5 HHV-6A is rarely considered pathogenic.

Unlike other herpesviruses, HHV-6 has the ability to integrate its genome into the chromosomal telomeres of infected cells when establishing latency, resulting in chromosomally integrated HHV-6 (ciHHV6).6 When chromosomal integration occurs in germline cells, the HHV-6 viral genome is vertically transmitted to 50% of offspring, resulting in inherited chromosomally integrated HHV-6 (iciHHV-6). Affected individuals will have at least one copy of the HHV-6 genome in every nucleated cell of their body, and thus will have HHV-6 DNA detected in any cellular sample, and typically in acellular serum and plasma samples due to cell lysis and DNA release during processing, even in the absence of active viral replication.5, 7 This condition is present in approximately 1% of the human population.8 HCT recipients receiving a hematopoietic cell graft from iciHHV-6 positive donors will have HHV-6 DNA in all donor hematopoietic cells following engraftment. HCT recipients who independently have iciHHV-6 will retain iciHHV-6 in their non-hematopoietic cells after HCT.

Though iciHHV-6 is generally considered a benign condition, we lack a complete understanding of possible pathologic consequences, particularly in immunocompromised hosts at risk for HHV-6 reactivation. Importantly, HHV-6 reactivation and associated disease from both chromosomally integrated HHV-6A and HHV-6B genomes are well documented, and iciHHV-6 has been associated with an increased risk of CMV and acute graft versus host diseases (aGVHD) in HCT recipients.9–11 The potential for HHV-6 reactivation and associated CNS symptoms after HCT in which either the donor or recipient has iciHHV-6 (iciHHV-6pos ) warrants further investigation. An additional challenge is that routine diagnostic methods do not distinguish between these conditions, and detection of latent HHV-6 DNA after iciHHV-6pos HCT may lead to inappropriate diagnostic and therapeutic interventions if findings are misattributed to viral reactivation.12, 13 This may be particularly problematic if routine screening is performed for HHV-6 after HCT.

We performed a retrospective study to compare the incidence of CNS symptoms in the first 100 days following allogeneic HCT among patients with donor and/or recipient iciHHV-6 (iciHHV-6pos) and patients who were donor/recipient negative for iciHHV-6 (iciHHV-6neg). We quantified HHV-6-driven antiviral use and diagnostic interventions after iciHHV-6pos HCT to assess the impact of iciHHV-6 on potentially unnecessary healthcare interventions.

Methods

The protocol was approved by the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center Institutional Review Board.

Study population

In a previous study, we identified 87 allogeneic iciHHV-6pos HCT recipients from a cohort of 4,319 HCT donor-recipient pairs who underwent first allogeneic HCT from 1992 to 2013 at our center and had pre-transplant cryopreserved peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) available for testing.11 Droplet digital polymerase chain reaction (ddPCR) was used detect iciHHV-6 based on the ratio of HHV-6 to human genome equivalents in PBMCs.14 PCR amplification of a conserved region of the U67/68 gene was used to distinguish between HHV-6A and HHV-6B species.14 These 87 iciHHV-6pos HCT recipients were randomly matched in a 1:2 ratio to 174 iciHHV-6neg controls. Matching was based on age, donor relation, human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-match (10/10 allele or antigen HLA-match versus any mismatch), conditioning regimen (myeloablative versus non-myeloablative), and year of transplant (1992-1999 versus 2000-2013).

Retrospective chart review was used to collect demographic and clinical information. The type and date of onset of any CNS symptom occurring during the first 100 days following HCT were captured. CNS symptoms were categorized as either isolated headache, toxic metabolic encephalopathy, seizure, HHV-6 encephalitis, or other. Toxic metabolic encephalopathy was defined as an acute change in mentation and/or behavior attributed to any combination of drugs, electrolyte abnormalities, organ dysfunction, endocrinopathy, or delirium. HHV-6 encephalitis was defined as a syndrome consisting of 1) clinical features of encephalitis AND 2) detectable HHV-6 DNA in cerebrospinal fluid AND 3) no alternative diagnosis.5 The dates of lumbar punctures (LP) and neuroimaging (computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain) performed between day 0 to day +100 were collected. Results of HHV-6 testing in plasma or CSF and HHV-6-targeted antiviral use (ganciclovir, valganciclovir or foscarnet specifically for the treatment of HHV-6) were recorded. Review of clinical notes was used to determine the indication for LPs performed within 7 days of HHV-6 testing. HHV-6 testing was not routinely performed but at the discretion of healthcare providers, who were unaware of patients’ or donor’s iciHHV-6 status.

Statistical analyses

We estimated the cumulative incidence of CNS symptoms stratified by iciHHV-6 status, HHV-6 species, and iciHHV-6 source (donor versus recipient) using Gray’s test; death was treated as a competing risk. Chi-square and Fischer’s-exact tests were used to compare proportions of iciHHV-6pos and iciHHV-6neg HCT recipients with detectable HHV-6 DNA in plasma and CSF or who received HHV-6 targeted antivirals, and to compare the crude incidence of neuroimaging between cohorts. Wilcoxon rank-sum used to compare peak plasma and CSF HHV-6 DNA viral loads. Pearson’s correlation coefficient was used to measure the association between HHV-6 DNA levels and the concentrations of nucleated cells and total protein in CSF specimens. We calculated that sample sizes consisting of 87 iciHHV-6pos and 174 matched iciHHV-6neg HCT recipients would provide >80% power to detect a ≥ two-fold difference in the incidence of CNS symptoms between cohorts with a type I error rate of 0.05, assuming an estimated 30% cumulative incidence of CNS symptoms in the iciHHV-6neg cohort (Table S1).15 R version 4.0.2 was used for analyses and figures.

Results

Patient and HCT characteristics

Of 87 iciHHV-6pos HCTs, the HCT recipient was iciHHV-6 positive (R+) in 60 (69%) cases, of which 13/60 (22%) involved an iciHHV-6 positive donor (D+/R+) and 47/60 (78%) involved an iciHHV-6 negative donor (D−/R+). The remaining 27 iciHHV-6pos HCTs (31%) were iciHHV-6 donor positive, recipient negative (D+/R−). The iciHHV-6 isolate was species B in 62 (72%) iciHHV-6pos HCTs and species A in 25 (28%). The iciHHV-6 species was concordant in all 13 D+/R+ pairs (3 iciHHV-6A and 10 iciHHV-6B). Demographics and clinical characteristics of the cohorts are in Table 1.

Table 1:

Demographics and clinical characteristics of iciHHV-6pos (donor and/or recipient iciHHV-6 pos) and iciHHV-6neg (both donor and recipient iciHHV-6 negative) allogeneic HCT cohorts.

| iciHHV-6pos (n=87) | iciHHV-6neg (n=174) | |

|---|---|---|

| Recipient age in years, median (range) | 41.4 (0.6-67.8) | 42.8 (0.5-71.5) |

| Female sex (recipient)*, n (%) | 33 (37.9) | 69 (39.7) |

| Year of transplant*, n (%) | ||

| 1992-1999 | 40 (45.9) | 66 (37.9) |

| 2000-2013 | 47 (54.0) | 108 (62.1) |

| Donor and recipient iciHHV-6 status, n (%) | ||

| D+/R− | 27 (31.0) | - |

| D+/R+ | 13 (14.9) | - |

| D−/R+ | 47 (54.0) | - |

| D−/R− | - | 174 (100.0) |

| iciHHV-6 species, n (%) a | ||

| iciHHV6-A | 25 (28.7) | - |

| iciHHV6-B | 62 (71.2) | - |

| CMV seropositive, donor, n (%) | 47 (44.0) | 76 (43.7) |

| CMV seropositive, recipient, n (%) | 45 (53.4) | 97 (55.6) |

| Underlying disease, n (%) | ||

| ALL | 11 (12.6) | 19 (10.9) |

| AML | 30 (34.5) | 46 (26.4) |

| CLL | 3 (3.4) | 4 (2.2) |

| CML | 19 (21.8) | 42 (24.1) |

| Lymphoma | 8 (9.2) | 12 (69.0) |

| MDS | 8 (9.2) | 20 (11.5) |

| Multiple myeloma | 3 (3.4) | 12 (6.9) |

| Otherb | 5 (5.7) | 19 (10.9) |

| Donor relationship/HLA matching* b, n (%) | ||

| Related, match | 33 (37.9) | 72 (41.4) |

| Related, mismatched | 6 (6.9) | 10 (5.7) |

| Related, haploidentical | 1 (1.1) | 1 (0.6) |

| Unrelated, matched | 35 (41.7) | 69 (39.6) |

| Unrelated, mismatched | 12 (14.2) | 22 (12.6) |

| Myeloablative conditioning* c | 62 (73.8) | 124 (70.8) |

| Cell source, n (%) | ||

| Bone marrow | 45 (51.7) | 86 (49.4) |

| Peripheral blood | 42 (48.3) | 87 (50.0) |

| Both | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.60) |

Abbreviations: Acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL), acute myelogenous leukemia (AML), chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML), cytomegalovirus (CMV), donor positive/recipient negative (D+/R−), donor negative/recipient positive (D−/R+), donor positive/recipient positive (D+/R+), donor negative/recipient positive (D−/R+), human leukocyte antigen (HLA), myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS)

Denotes matching criteria

iciHHV-6 species was concordant in all 13 iciHHV-6 D+/R+ cases (3 iciHHV-6A, 10 iciHHV-6B)

Other underlying diseases included: aplastic anemia, erythroleukemia, Chediak-Higashi syndrome, myelofibrosis, myelodysplastic syndrome, agnogenic myeloid metaplasia, paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobulinuria, refractory anemia, refractory anemia with excess blasts, Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinemia.

HLA match indicates 10/10 allele match or antigen match.

Myeloablative regimens included: any regimen containing ≥800 cGy total body irradiation, any regimen containing carmustine/etoposide/cytarabine/melphalan (BEAM), or any regimen containing busulfan/cyclophosphamide with or without anti-thymocyte globulin.

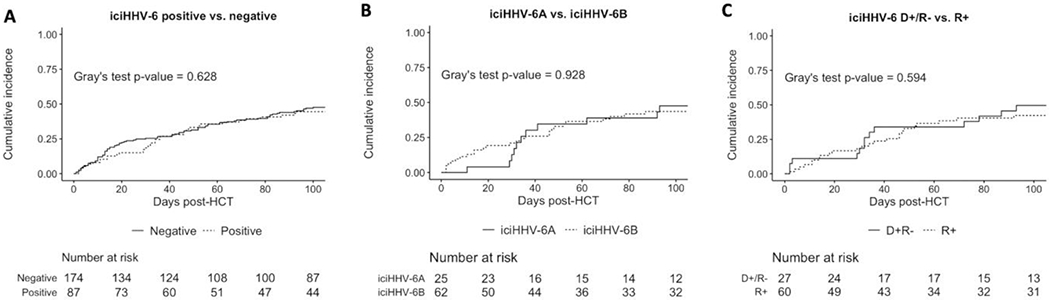

CNS symptoms

Thirty-seven (42.5%) iciHHV-6pos and 81 (46.6%) iciHHV-6neg HCT recipients developed any CNS symptom within the first 100 days post-HCT. The cumulative incidence of CNS symptoms was similar between iciHHV-6pos and iciHHV-6neg HCTs (P=0.63, Figure 1A). In the iciHHV6pos cohort, the cumulative incidence of CNS symptoms did not differ by HHV-6 species (P=0.93, Figure 1B) or recipient iciHHV-6 status (D+/R− versus D+/R+ or D−/R+, P=0.59; Figure 1C). The most frequent CNS symptom after both iciHHV-6pos and iciHHV-6neg HCT were headache (26% and 18%, respectively) and toxic-metabolic encephalopathy (18% and 21%, respectively) (Table 2). Neuroimaging studies were also performed with similar frequency in iciHHV-6pos and iciHHV-6 neg patients (33% vs. 29%, respectively, P=0.5).

Figure 1:

Cumulative incidence of CNS symptoms after allogeneic HCT

Abbreviations: Donor negative, recipient positive (D−/R+), donor positive, recipient negative (D+/R−), inherited chromosomally integrated HHV-6 (iciHHV-6)

Cumulative incidence probability estimates of time to first CNS symptom within the first 100 days after allogeneic HCT. Death was treated as a competing risk event. A: Cumulative incidence of CNS symptoms in iciHHV-6pos vs. iciHHV-6neg HCT recipients 1B: Cumulative incidence of CNS symptoms in iciHHV-6pos cases, stratified by HHV-6 species (HHV-6A vs. HHV-6B). C: Cumulative incidence of CNS symptoms in iciHHV6pos cases, stratified by donor/recipient status (D+/R− vs. R+).

Table 2:

Crude incidence of CNS symptoms in the first 100 days following hematopoietic cell transplant

| CNS symptom, n (%) | iciHHV-6pos (n=87) | iciHHV6neg (n=174) |

|---|---|---|

| Any CNS symptom a | 37 (42.5) | 81 (46.6) |

| Headache | 23 (26.4) | 32 (18.4) |

| Toxic-metabolic encephalopathy | 16 (18.4) | 38 (21.8) |

| Seizure | 6 (6.9) | 3 (1.7) |

| Other | 7(8.0) | 1 (0.6) |

| HHV-6 related CNS symptoms | ||

| Typical HHV-6 encephalitis | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.6) |

| Possible HHV-6 related CNS dysfunction | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) |

Abbreviations: central nervous system (CNS), inherited chromosomally integrated HHV-6 (iciHHV-6)

CNS events were not mutually exclusive

Eight patients (7 iciHHV-6pos and 1 iciHHV-6neg) had detectable HHV-6 DNA in the CSF during the first 100 days post-HCT; their CNS symptoms and clinical courses are summarized in Table 3. Of the overall cohort, 1/174 iciHHV-6neg patients (0.5%) had typical HHV-6 encephalitis (species testing not performed) characterized by acute encephalopathy, bilateral mesial temporal lobe changes on MRI of the brain, and a peak CSF viral load of 300,000 copies/mL. Clinical improvement with expected virologic clearance occurred after treatment with ganciclovir (Case 8, Table 3 and Figure 2). In addition, one iciHHV-6Apos patient developed possible HHV-6 encephalitis characterized by delirium on day +11 and a peak CSF viral load of 2,500 copies/mL (Case 1, Table 3). Treatment with foscarnet was initiated without clear benefit and was stopped after two weeks due to renal failure. MRI of the brain was unremarkable and he died on day +40 post HCT with multiorgan failure. Post-mortem exam of the brain revealed increase in microglia and slight hippocampal neuronal dropout without prominent necrosis or astrogliosis, findings possibly consistent with viral encephalitis. This case was previously described and sequencing suggested reactivation from the integrated HHV-6 genome as the possible cause,16 although the patient was started on 2mg/kg of methylprednisolone for aGVHD the day prior which may have exacerbated CNS symptoms.

Table 3:

Clinical features of patients with HHV-6 DNA detected in CSF

| Case | Age/Sex | iciH HV-6 D/R status (species) | Symptom(s) prompting HHV-6 testing | Number of LPs | Number of HHV-6 plasma tests | Engraftment Day | Peak plasma HHV-6, copies/mL (day) | Peak CSFHHV-6, copies/mL (day) | Additional explanation for symptoms | Clinical course and comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Donor negative, recipient positive (D+/R−) iciHHV-6pos patients | ||||||||||

| 1 | 52 M | D−/R+ (A) | Confusion, hallucinations | 3 | 0 | +17 | N/A | 2,500 (+12) | Steroid-induced psychosis; possible encephalitis on autopsy | Foscarnet x 2 weeks, stopped due to acute renal failure |

| 2 | 49 F | D−/R+ (A) | Encephalopathy | 1 | 1 | +26 | 670 (+38) | 190 (+40) | Hyperamm onemia, sepsis due to E. faecium and E. cloacae bacteremia | Ganciclovir x 2 weeks, up to day of death from septic shock and multiorgan failure in the context of recurrent E. cloacae bacteremia |

| 3 | 23 F | D−/R+ (B) | Hallucinations | 1 | 8 | +27 | 2,100 (+18) | 28 (+21) | ICU delirium, self-resolved without intervention | LP performed in response to positive plasma PCR despite resolution of symptoms prior to LP. No treatment as HHV-6 was not felt to be clinically significant. Serial plasma HHV-6 monitoring performed |

| Donor positive, recipient negative (D−/R+) iciHHV-6pos patients | ||||||||||

| 4 | 61 M | D+/R− (A) | Agitation, confusion, seizures | 2 | 8 | +28 | 7,500 (+65) | 1,600 (+98) | Calcineurin inhibitory toxicity | IV ganciclovir x 2 weeks. LP performed in response to positive plasma PCR despite resolution of symptoms prior to LP. Treatment stopped due to unchanged viral load and resolution of symptoms |

| 5 | 20 M | D+/R− (A) | Headache | 2 | 3 | +28 | 20,000 (+78) | 8,000 (+77) | Intrathecal methotrexate | IV ganciclovir x 2 weeks, stopped due to resolution of headaches |

| 6 | 51 M | D+/R− (B) | Irritability, psychosis, argumentativeness | 1 | 1 | +27 | 11,000 (+91) | 760 (+94) | Steroid-induced psychosis | Course of ganciclovir for CMV enteritis was extended by 6 days due to HHV-6 findings |

| 7 | 6 F | D+/R− (B) | Fever | 2 | 12 | +29 | 130,000 (+72) | 15,000 (+70) | Coagulase-negative staphylococcus bacteremia | IV ganciclovir x 2 weeks; stopped due to continued fevers and unchanged HHV-6 DNA level |

| iciHHv-6neg patient | ||||||||||

| 8 | 52 F | iciH HV-6 negative | Headache, hallucinations, encephalopathy | 1 | 3 | +19 | 36,000 (+27) | 300,000 (+26) | None | Ganciclovir x 5 weeks, stopped after resolution of symptoms and CSF viral clearance |

Abbreviations: donor (D), female (F), cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), inherited chromosomally integrated human herpes virus 6 (iciHHV-6), intensive care unit (ICU), intravenous (IV), lumbar puncture (LP), male (M), recipient (R)

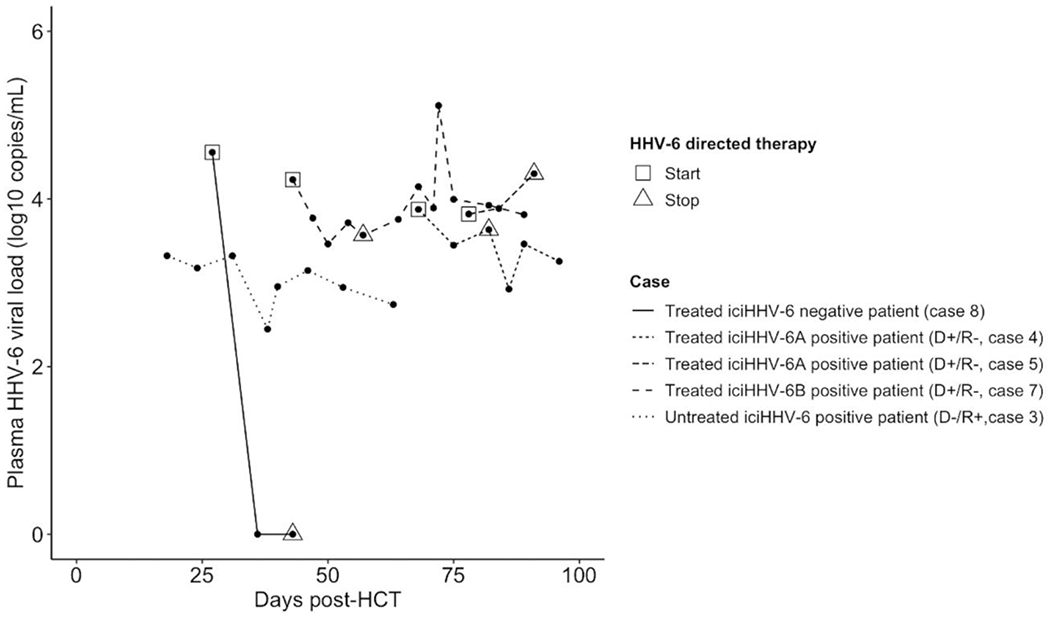

Figure 2.

Kinetics of plasma HHV-6 viral load in patients with longitudinal clinical testing

Abbreviations: donor positive, recipient negative (D+/R−), hematopoietic cell transplant (HCT), inherited chromosomally integrated human herpes virus 6 (iciHHV-6)

Plasma HHV-6 DNA levels among 3 treated iciHHV-6pos, 1 untreated iciHHV-6pos , and 1 treated iciHHV-6neg HCTs. Engraftment occurred prior to all HHV-6 plasma tests for all patients, with the exception of Case 3, in which the first specimen was on day +18, 3 days prior to engraftment on day +21.

Plasma and CSF HHV-6 PCR testing

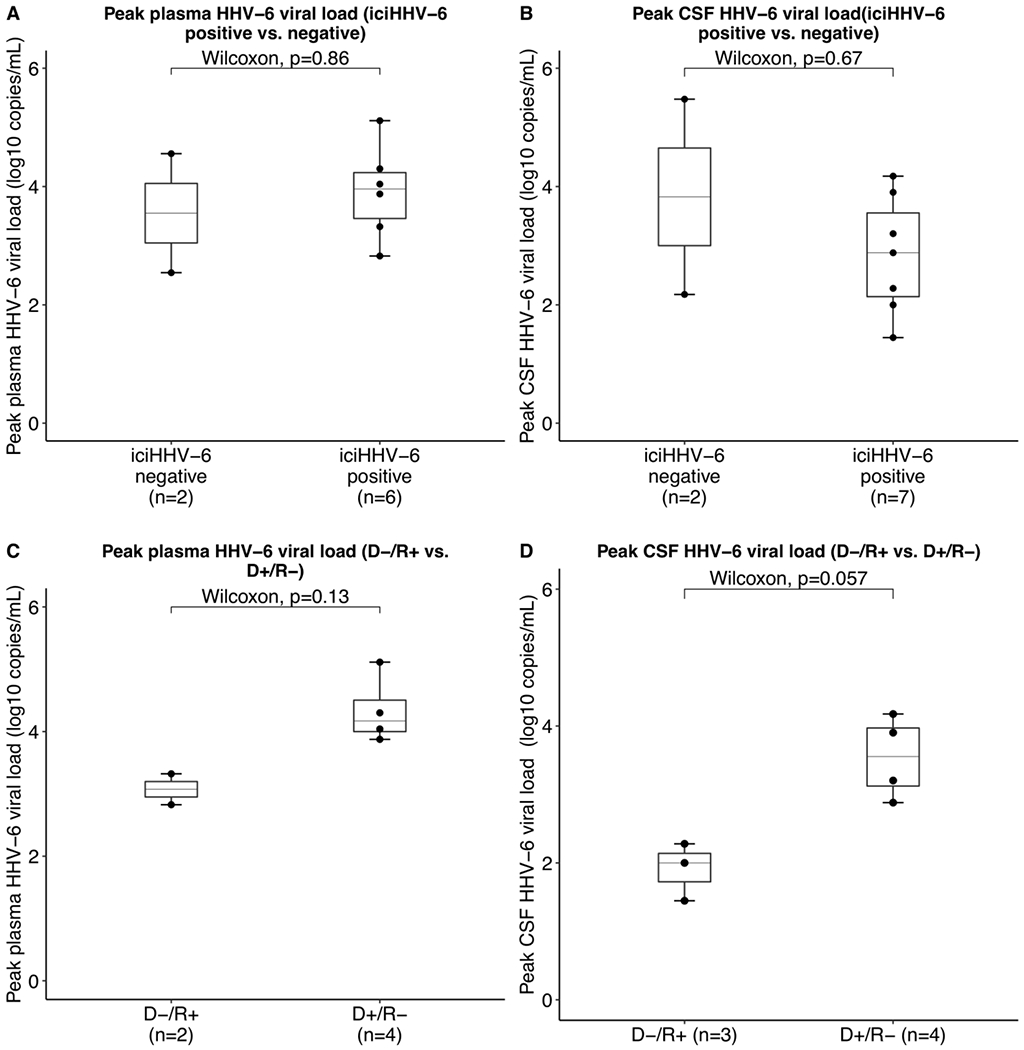

HHV-6 testing of plasma was performed in similar proportions of iciHHV-6pos (6/87, 7%) and iciHHV-6neg HCTs (15/174, 9%; P>0.9). HHV-6 testing of CSF was performed in 8/87 (9%) iciHHV-6pos and 10/174 (6%) iciHHV-6neg HCTs (P=0.8). All HHV-6 testing was performed after neutrophil engraftment, with the exception of one plasma and one CSF specimen from two different patients (Case 3 and 1, respectively; Table 3). HHV-6 DNA was significantly more likely to be detected in iciHHV-6pos patients compared to iciHHV-6neg patients, both in the plasma [6/6 (100%) vs. 2/15 (13%), P=0.005] and in the CSF [7/8 (88%) vs. 1/10 (10%), P=0.02]. Only one CSF specimen from an iciHHV-6pos (D+/R−, species A) HCT recipient did not have detectable HHV-6. Peak viral load in plasma and CSF were similar in the iciHHV-6pos and iciHHV-6neg cohorts (Figure 3). There was no apparent correlation between CSF HHV-6 viral load and CSF nucleated cell count in iciHHV-6 D+/R− or with total protein in iciHHV-6 R+ individuals (Figure S1, Supplementary materials).

Figure 3:

Peak HHV-6 DNA levels in plasma and cerebrospinal fluid

Abbreviations: cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), donor negative, recipient positive (D−/R+), donor positive, recipient negative (D+/R−), inherited chromosomally integrated HHV-6 (iciHHV-6)

Peak HHV-6 DNA levels individuals with detectable DNA in the CSF and/or plasma 3A: Peak cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) HHV-6 viral load in iciHHV-6pos and iciHHV-6neg HCT recipients 3B: Peak CSF HHV-6 viral load in iciHHV-6pos cases, stratified by donor and recipient iciHHV-6 status. 3C: Peak plasma HHV-6 viral load in iciHHV-6pos and iciHHV-6neg HCT recipients. 3D: Peak plasma viral load in iciHHV-6pos cases, stratified by donor and recipient iciHHV-6 status. No D+/R+ patient underwent plasma or CSF testing. The peak CSF viral loads (and plotted data points) occurred post-engraftment in all patients. One patient had two identical CSF HHV-6 measurements in two different LPs, one of which was collected prior to engraftment (Case 1, Table 3).

HHV-6-driven lumbar puncture and antiviral therapy

We investigated how the detection of HHV-6 in plasma or CSF impacted medical interventions. In three of six (50%) iciHHV-6pos patients who had HHV-6 detected in the plasma, the positive result prompted CSF HHV-6 testing despite the absence of or improvement in CNS symptoms by the time LP was performed (Table 3). Two of these patients (Case 3 and Case 4) underwent an LP solely for HHV-6 diagnostics, and the third was receiving a planned LP for intrathecal chemotherapy at which time CSF was collected for HHV-6 testing (Case 7). Six of the eight iciHHV6pos patients who underwent an LP with testing of CSF for HHV-6 were treated with antivirals.

Overall, iciHHV-6pos HCT recipients were significantly more likely to receive HHV-6-targeted antivirals [6/87 (7%) versus 1/173 (0.6%); OR, 12.81; 95% CI, 1.52-108.2; P<0.001]. All six of the treated iciHHV-6pos patients had a more likely etiology for the symptoms that led to HHV-6 testing, except for the case of possible viral encephalitis on autopsy with concurrent corticosteroid use (Case 1, Table 3), as corticosteroids alone were unlikely to have precipitated the severe and prolonged CNS symptoms observed in that case. Two iciHHV-6pos patients developed treatment related toxicities including renal failure from foscarnet and neutropenia from ganciclovir (Cases 1 and 4, respectively; Table 3). Plasma HHV-6 DNA decreased in response to treatment in the iciHHV-6neg patient with HHV-6 encephalitis (Case 8) but remained elevated despite treatment in all iciHHV-6pos cases (Figure 2), as would be expected from detection of latently integrated viral DNA without viral replication.

Discussion

In this large study of allogeneic HCT recipients, there was no association between iciHHV-6 and CNS symptoms. As expected, HHV-6 was detected in the plasma of all six and in the CSF of 7 of 8 iciHHV-6pos patients who were tested. Positive plasma results prompted unnecessary LPs in two iciHHV-6pos patients without active CNS symptoms. HHV-6 directed antiviral use was significantly more common in iciHHV-6pos patients, two of whom developed serious toxicities related to therapy.

CNS symptoms following HCT are common and multifactorial due to toxicities associated with aspects of the HCT itself and post-HCT management.17 Conditioning regimens, pain medications, and medications used to prevent GVHD (e.g. calcineurin inhibitors, corticosteroids) or infections (e.g. voriconazole, cefepime) are all associated with altered mentation in the early post-HCT period, particularly when they occur in the setting of organ dysfunction, electrolyte abnormalities, or underlying delirium due to an unfamiliar hospital setting .15, 17 We observed a 40% cumulative incidence any CNS symptoms and a 20% incidence of toxic-metabolic encephalopathy, consistent with previously reported incidences in the first 100 days following HCT.15, 17 However, there was no evidence for an increased incidence of CNS symptoms, or HHV-6 encephalitis, after iciHHV-6pos compared to iciHHV6neg HCT, irrespective of HHV-6 species or whether the donor or recipient was affected. Possible HHV-6 encephalitis occurred in one iciHHV-6pos patient and definite HHV-6 encephalitis occurred in 1 iciHHV-6neg patient, consistent with expected incidences of HHV-6 encephalitis of about 1% in this population.18

As expected, HHV-6 was detected in nearly all tested CSF and plasma specimens after iciHHV-6pos HCT. Viral loads in plasma specimens from D+/R− did not decrease in response to antiviral therapy, indicating that plasma HHV-6 detection in these individuals was most likely from latently integrated DNA released during sample processing rather than viral replication.19, 20 Interestingly, two iciHHV-6 D+/R− patients had relatively high CSF HHV-6 viral loads (>3 log10 copies/mL) without any reported nucleated cells. This HHV-6 DNA could represent shedding of iciHHV-6 DNA from donor hematopoietic cells that migrated to the CNS or from blood contamination of CSF during LP. Reactivation from naturally acquired, non-chromosomally integrated HHV-6 in the CNS could explain these findings, although these individuals did not have a syndrome typical of HHV-6 CNS disease. There was overlap in the peak viral loads in both the CSF and plasma among iciHHV-6pos and iciHHV-6neg cases, demonstrating that viral loads in acellular specimens cannot reliably distinguish between iciHHV-6 and HHV-6 reactivation from naturally acquired infection.

Although iciHHV-6pos HCT recipients did not experience an increased incidence of CNS symptoms, they were frequently subjected to healthcare interventions as a consequence of HHV-6 DNA detection given lack of recognition of iciHHV-6 at the time. Two iciHHV-6pos HCT recipients presented with transient CNS symptoms for which LP was not initially warranted but ultimately underwent an LP to evaluate for HHV-6 encephalitis in response detection of HHV-6 DNA in plasma, despite improvement of symptoms without antivirals by the time LP was performed. There was an additional explanation for CNS symptoms in most iciHHV-6pos patients who underwent evaluation for HHV-6 related CNS disease. Regardless, most iciHHV-6pos patients with a positive HHV-6 PCR result in either plasma or CSF received antiviral therapy, and iciHHV-6pos HCT was associated with a 12-fold increase in antiviral use. Two patients experienced significant toxicities related to HHV-6 directed treatment after iciHHV-6pos HCT. These cases highlight the potential for serious ramifications as a result of unrecognizediciHHV-6, and the potential role for better diagnostic approaches to improve antiviral stewardship.21

Donor and recipient screening for iciHHV-6 should be considered prior to HCT to assist with post-HCT clinical decision making, particularly if planning to monitor for HHV-6 viremia or initiate preemptive therapy as HHV-6 viremia is expected after iciHHV-6pos HCT and preemptive therapy will not result in viral clearance. However, testing for iciHHV-6 is not locally available at most transplant centers, and the prevalence of donor and/or recipient iciHHV-6 is low (~2% of all HCTs).11 Therefore, the utility of routine iciHHV-6 screening may be limited, and a pragmatic approach could be to perform iciHHV-6 testing when HHV-6 detection is of unclear clinical significance, particularly when HHV-6 viremia persists for 2-3 weeks despite antivirals.5 For severely ill patients, delaying LP and antiviral therapy until results of iciHHV-6 testing are available may not be appropriate, but identifying iciHHV-6 after commencing therapy may allow providers to discontinue antivirals, particularly when symptoms have alternative etiologies.

Routine HHV-6 PCR testing cannot distinguish between latent HHV-6 DNA and actively replicating HHV-6. Thus, diagnosing HHV-6 infection in known iciHHV-6pos HCT recipients remains a significant challenge. Amplification of HHV-6 messenger RNA (mRNA) using reverse transcription real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) is a novel technique that can identify viral gene expression from the integrated virus as a surrogate for viral replication and could be valuable in this scenario.7, 12, 22 RT-qPCR is currently limited to research settings, and clinically actionable thresholds will need to be established before incorporation into practice.7 Droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) may also distinguish reactivation of naturally acquired infection in the background of iciHHV-6. A ddPCR assay to identify iciHHV-6 can be ordered from the University of Washington Department of Laboratory Medicine. If iciHHV-6 is identified and there is concern for concurrent HHV-6 infection without a clear alternative etiology, continued antiviral therapy can be considered for a defined interval of 2-3 weeks based on symptomatic response.

A key strength of our was study was the use of a unique biorepository to identify a large population of iciHHV-6pos HCT recipients and a matched iciHHV-6neg cohort. Well-annotated clinical records were available for all study participants, allowing us to perform the largest epidemiological study of neurologic outcomes after iciHHV-6pos HCT. Yet, the retrospective nature of the study did not allow for standardized assessments of CNS symptoms, and lack of targeted cognitive testing may have precluded identification of subtle and less-acute neurologic insults associated with iciHHV-6.18, 23 CNS symptoms are often multifactorial in this patient population and may not be fully captured in clinical notes, making causal attributions challenging. To account for some of these limitations, we used neuroimaging as an objective correlate for CNS symptomatology and noted a similar crude incidence between iciHHV-6pos and iciHHV-6neg cohorts, corroborating the validity of our clinical observations. The majority of patients in the present study received allografts from HLA-matched donors, and no patients received umbilical cord blood transplant (UCBT) or ex-vivo T-cell depleted allografts. UCBT, HLA donor-recipient mismatch, and ex-vivo T-cell depletion confer a substantially increased risk of HHV-6 reactivation, delirium, and limbic encephalitis following HCT, 24, 25 and iciHHV-6 may have different sequalae in these high-risk groups that could not be appreciated in this investigation.

In summary, neither donor nor recipient iciHHV-6 was associated with CNS symptoms in the first 100 days following allogeneic HCT. Viral load in plasma or CSF could not reliably distinguish iciHHV-6 DNA from reactivation of non-chromosomally integrated virus. Detection of HHV-6 DNA in the plasma or CSF after iciHHV-6pos HCT led to unnecessary procedures and exposure to toxic antivirals. Reflexive or targeted testing for iciHHV-6 may aid in post-HCT management and reduce the cost and complications associated with HHV-6 directed antivirals, particularly if routine post-HCT HHV-6 screening tests are performed.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Byron Maltez and Andrew Cox for their assistance with chart review.

Funding:

This work was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health [T32AI118690 to M.R.H.]. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Disclosures:

M.B. received consulting fees from Symbio, Gilead Sciences, Allovir, and research support from Gilead Sciences. J.A.H received consulting fees from Gilead Sciences, Amplyx, Allovir, Allogene, Takeda, CRISPR and research support from Takeda, Allovir, Karius, Gilead.

Footnotes

The other authors have no relevant interests to disclose.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Agut H, Bonnafous P, Gautheret-Dejean A. Laboratory and clinical aspects of human herpesvirus 6 infections. Clin Microbiol Rev Apr 2015;28(2):313–35. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00122-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zerr DM, Meier AS, Selke SS, et al. A population-based study of primary human herpesvirus 6 infection. N Engl J Med. February2005;352(8):768–76. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa042207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grinde B Herpesviruses: latency and reactivation - viral strategies and host response. J Oral Microbiol. October2013;5doi: 10.3402/jom.v5i0.22766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hill JA, Zerr DM. Roseoloviruses in transplant recipients: clinical consequences and prospects for treatment and prevention trials. Curr Opin Virol. December2014;9:53–60. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2014.09.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ward KN, Hill JA, Hubacek P, et al. Guidelines from the 2017 European Conference on Infections in Leukaemia for management of HHV-6 infection in patients with hematologic malignancies and after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Haematologica. 11 2019;104(11):2155–2163. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2019.223073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arbuckle JH, Medveczky MM, Luka J, et al. The latent human herpesvirus-6A genome specifically integrates in telomeres of human chromosomes in vivo and in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. March2010;107(12):5563–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0913586107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hill JA. Human herpesvirus 6 in transplant recipients: an update on diagnostic and treatment strategies. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 12 2019;32(6):584–590. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0000000000000592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pellett PE, Ablashi DV, Ambros PF, et al. Chromosomally integrated human herpesvirus 6: questions and answers. Rev Med Virol. May2012;22(3):144–55. doi: 10.1002/rmv.715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Endo A, Watanabe K, Ohye T, et al. Molecular and virological evidence of viral activation from chromosomally integrated human herpesvirus 6A in a patient with X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency. Clin Infect Dis. August2014;59(4):545–8. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Strenger V, Caselli E, Lautenschlager I, et al. Detection of HHV-6-specific mRNA and antigens in PBMCs of individuals with chromosomally integrated HHV-6 (ciHHV-6). Clin Microbiol Infect. October2014;20(10):1027–32. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hill JA, Magaret AS, Hall-Sedlak R, et al. Outcomes of hematopoietic cell transplantation using donors or recipients with inherited chromosomally integrated HHV-6. Blood. 08 2017;130(8):1062–1069. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-03-775759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hill JA, Sedlak RH, Jerome KR. Past, present, and future perspectives on the diagnosis of Roseolovirus infections. Curr Opin Virol. December2014;9:84–90. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2014.09.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Potenza L, Barozzi P, Masetti M, et al. Prevalence of human herpesvirus-6 chromosomal integration (CIHHV-6) in Italian solid organ and allogeneic stem cell transplant patients. Am J Transplant. Jul 2009;9(7):1690–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02685.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sedlak RH, Hill JA, Nguyen T, et al. Detection of Human Herpesvirus 6B (HHV-6B) Reactivation in Hematopoietic Cell Transplant Recipients with Inherited Chromosomally Integrated HHV-6A by Droplet Digital PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 05 2016;54(5):1223–7. doi: 10.1128/JCM.03275-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Siegal D, Keller A, Xu W, et al. Central nervous system complications after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: incidence, manifestations, and clinical significance. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. November2007;13(11):1369–79. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2007.07.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hill JA, Sedlak RH, Zerr DM, et al. Prevalence of chromosomally integrated human herpesvirus 6 in patients with human herpesvirus 6-central nervous system dysfunction. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. Feb 2015;21(2):371–3. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2014.09.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fann JR, Roth-Roemer S, Burington BE, Katon WJ, Syrjala KL. Delirium in patients undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Cancer. Nov 2002;95(9):1971–81. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zerr DM, Gooley TA, Yeung L, et al. Human herpesvirus 6 reactivation and encephalitis in allogeneic bone marrow transplant recipients. Clin Infect Dis. September2001;33(6):763–71. doi: 10.1086/322642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hubacek P, Maalouf J, Zajickova M, et al. Failure of multiple antivirals to affect high HHV-6 DNAaemia resulting from viral chromosomal integration in case of severe aplastic anaemia. Haematologica. Oct 2007;92(10):e98–e100. doi: 10.3324/haematol.11592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee SO, Brown RA, Razonable RR. Chromosomally integrated human herpesvirus-6 in transplant recipients. Transpl Infect Dis. August2012;14(4):346–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3062.2011.00715.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wolf J, Margolis E. Effect of Antimicrobial Stewardship on Outcomes in Patients With Cancer or Undergoing Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation. Clin Infect Dis. Aug 2020;71(4):968–970. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hill JA, Ikoma M, Zerr DM, et al. RNA Sequencing of the. J Virol. 02 2019;93(3)doi: 10.1128/JVI.01419-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zerr DM, Fann JR, Breiger D, et al. HHV-6 reactivation and its effect on delirium and cognitive functioning in hematopoietic cell transplantation recipients. Blood. May 2011;117(19):5243–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-10-316083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hill JA, Koo S, Guzman Suarez BB, et al. Cord-blood hematopoietic stem cell transplant confers an increased risk for human herpesvirus-6-associated acute limbic encephalitis: a cohort analysis. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. Nov 2012;18(11):1638–48. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2012.04.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hill JA, Boeckh M, Leisenring WM, et al. Human herpesvirus 6B reactivation and delirium are frequent and associated events after cord blood transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. Oct 2015;50(10):1348–51. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2015.154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.