Abstract

Background

Although the clinical efficacy of tofacitinib in patients with ulcerative colitis (UC) has been assessed in the OCTAVE trial, there is a lack of adequate data on its efficacy in real-world clinical settings.

Aims

To analyze the efficacy of tofacitinib and the predictors of its continuation.

Methods

Changes in clinical activity index (CAI), blood test results (C-reactive protein [CRP], albumin [Alb], and hemoglobin), and endoscopic scores (Mayo endoscopic subscore [MES], ulcerative colitis endoscopic index of severity [UCEIS]) were evaluated, and we investigated the factors that affect the rate and continuity of tofacitinib.

Results

Twenty-two patients with UC who were treated with tofacitinib were enrolled. Tofacitinib was continued in 16/22 (72.7%) patients. CAI significantly improved 4 weeks after tofacitinib induction (P < 0.01). In the blood tests, only Alb level improved significantly at week 2 compared with baseline (P = 0.03). In the non-failure group, serum Alb and CRP levels improved significantly from week 0 to week 24; however, similar changes were not observed in the failure group. After 6 months, the overall MES and UCEIS had significantly improved (P = 0.03 and P = 0.02, respectively). Kaplan–Meier analysis demonstrated that those with baseline UCEIS ≥ 5 had significantly lower tofacitinib continuation rate than those with baseline UCEIS ≤ 4, suggesting that baseline UCEIS may be a predictor of tofacitinib continuation (log-rank test: P < 0.01).

Conclusions

Tofacitinib is a promising therapeutic agent for the induction and maintenance therapy in UC. Baseline UCEIS may predict its therapeutic effects.

Keywords: Ulcerative colitis, Therapy, Endoscopy, C-reactive protein, Serum albumin

Introduction

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is an idiopathic inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) with repeated relapses and remissions [1]. Previously, steroids constituted the basic treatment for moderate-to-severe UC; however, steroid resistance and refractory disease are common clinical problems [2–4]. Persistent chronic inflammation of the colon due to steroid resistance may eventually result in colectomy [5, 6]. Additionally, in the case of steroid dependence, it is necessary to use steroids continuously even if the symptoms of UC are alleviated because of frequent relapses when steroids are discontinued [7, 8].

There was no alternative treatment for steroids in refractory UC; however, the treatment options have increased in recent years with the development of various treatments. Most of them are biological therapies that can be used continuously—from induction of remission to the maintenance of remission. Previously, the usefulness of infliximab (IFX), adalimumab (ADA), and golimumab (GOL) that target the tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α have been reported, and they still play a central role in clinical practice in the treatment of UC [9–11]. Additionally, vedolizumab (VDZ), tofacitinib, and ustekinumab, which target other inflammatory cytokines involved in UC pathologies, have also been reported to be useful [12–14]. Tofacitinib is an oral Janus kinase inhibitor. Three randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III trials evaluated the usefulness and safety of tofacitinib in UC [13]. These trials focused on the induction of remission (OCTAVE Induction 1 and OCTAVE Induction 2) and maintenance therapy (OCTAVE Sustain); they revealed the induction and maintenance effects of tofacitinib in UC.

Therefore, although the usefulness and proper use of tofacitinib have been reported in large-scale clinical trials, its real-world data in clinical practice are lacking. Furthermore, with the increasing number of treatment options for steroid-resistant UC, it is crucial to analyze cases in clinical practice in which tofacitinib can be continued. In this study, we aimed to evaluate the clinical activity, biological laboratory findings, and endoscopic findings and analyze them to identify predictors of efficacy and continuation of tofacitinib at our institution.

Materials and Methods

Patients and Study Design

Patients with UC who were treated with tofacitinib at the Hamamatsu University School of Medicine between January 2019 and February 2021 were enrolled in this study. These patients were diagnosed with UC according to the established current criteria based on typical clinical symptoms, endoscopic findings, and histological evaluation [15]. Patients with IBD such as indeterminate colitis or unclassified IBD at the time of diagnosis were excluded.

This was a retrospective, single-center observational study. The primary endpoint was the evaluation of factors that affected the continuation rate of treatment with tofacitinib. The secondary endpoints were changes in clinical activity index (CAI), laboratory findings at weeks 0, 2, 8, and 24, and endoscopic scores at weeks 0 and 24.

Disease Assessment

We evaluated the clinical disease activity using CAI according to Rachmilewitz [16]. In this study, clinical remission was defined as CAI of 4, while clinical response was defined as a decrease of 4 points in CAI compared with that at baseline. Patients who achieved clinical remission or clinical response were considered as responders. Serum levels of C-reactive protein (CRP), albumin (Alb), and hemoglobin (Hb) were measured at the Hamamatsu University School of Medicine.

Endoscopic Assessment

The endoscopic score of UC was evaluated using Mayo endoscopic subscore (MES) and ulcerative colitis endoscopic index of severity (UCEIS). The criteria for MES were as follows: 0, normal or inactive disease; 1, mild disease with erythema, decreased vascular pattern, and mild friability; 2, moderate disease with marked erythema, absence of vascular patterns, friability, and erosions; and 3, severe disease with spontaneous bleeding and ulceration [17]. UCEIS score was calculated by summing the scores of the following three descriptors: vascular pattern (score, 0–2), bleeding (score, 0–3), and erosions and ulcers (score, 0–3) [18]. UCEIS scores are in the range of 0–8.

Treatment and Follow-Up of Patients

Patients enrolled in this study visited our hospital regularly once a week for 2 months. Tofacitinib was orally administered at a dose of 10 mg twice daily during the induction phase and 5 mg twice daily during the maintenance phase. In order to understand the patient’s conditions outside the hospital, patients were instructed to record any clinical symptoms based on CAI. Patients filled out the CAI-based data daily on a record sheet, and at the time of examination, we collected the record sheet to evaluate the CAI. Switching from tofacitinib to another treatment due to an increase in the number of bowel movements, appearance of bloody stools, and increase in CAI by 4 points or more was defined as failure, and the treatment decisions were at the discretion of the attending physician. Some laboratory data were missing because some patients did not visit our hospital due to inconvenience.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS v24 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and EZR (Saitama Medical Center, Jichi Medical University, Saitama, Japan). The Mann–Whitney U test or Student’s t-test was used to evaluate differences. Kaplan–Meier analysis with log-rank test was used to evaluate the cumulative failure-free rate. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

Patient Characteristics

Overall, 22 patients with UC who were treated with tofacitinib were enrolled in this study (Table 1). The mean age of the patients was 45.7 years, and the mean disease duration was 7.2 years (range, 0.8–28). Of them, 14 patients had extensive colitis, seven had left-sided colitis, and one had proctitis. Other treatments administered at the start of tofacitinib therapy were oral 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) in 13 patients (59.1%), suppository steroids in three patients (13.6%), and systemic steroids in three patients (13.6%). Ten patients (45.5%) had a history of using biologicals. One patient in remission with GOL was forced to discontinue it due to the side effects and was switched to tofacitinib. The patient’s CAI was 1, CRP was 0.01 mg/dL, MES was 0, and UCEIS was 2.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Characteristics at enrollment | N = 22 |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 45.7 (20–73) ± 16.2 |

| Males/females | 13/9 (59.1/40.9) |

| Disease duration (years) | 7.2 (0.8–28) ± 7.2 |

| Disease extent | |

| Extensive colitis | 14 (63.6) |

| Left-sided colitis | 7 (31.8) |

| Proctitis | 1 (4.5) |

| CAI (Rachmilewitz index) | 4.8 (1–9) ± 1.8 |

| CRP (mg/dL) | 0.47 (0.01–6.59) ± 1.10 |

| Alb (g/dL) | 4.03 (2.9–4.8) ± 0.49 |

| Hb (g/dL) | 12.87 (8.9–15.5) ± 1.97 |

| MES | |

| MES 0 | 1 (4.5) |

| MES 1 | 6 (27.3) |

| MES 2 | 12 (54.5) |

| MES 3 | 3 (13.6) |

| UCEIS | 4.09 (2–7) ± 1.38 |

| Other medication at start | |

| Oral 5-ASA | 13 (59.1) |

| Suppository steroids | 3 (13.6) |

| Systemic steroids | 3 (13.6) |

| History of biologics use | 10 (45.5) |

Data are presented as mean (range) ± standard deviation or n (%)

CAI clinical activity index, CRP C-reactive protein, Alb albumin, Hb hemoglobin, MES Mayo endoscopic subscore, UCEIS ulcerative colitis endoscopic index of severity, 5-ASA 5-aminosalicylic acid

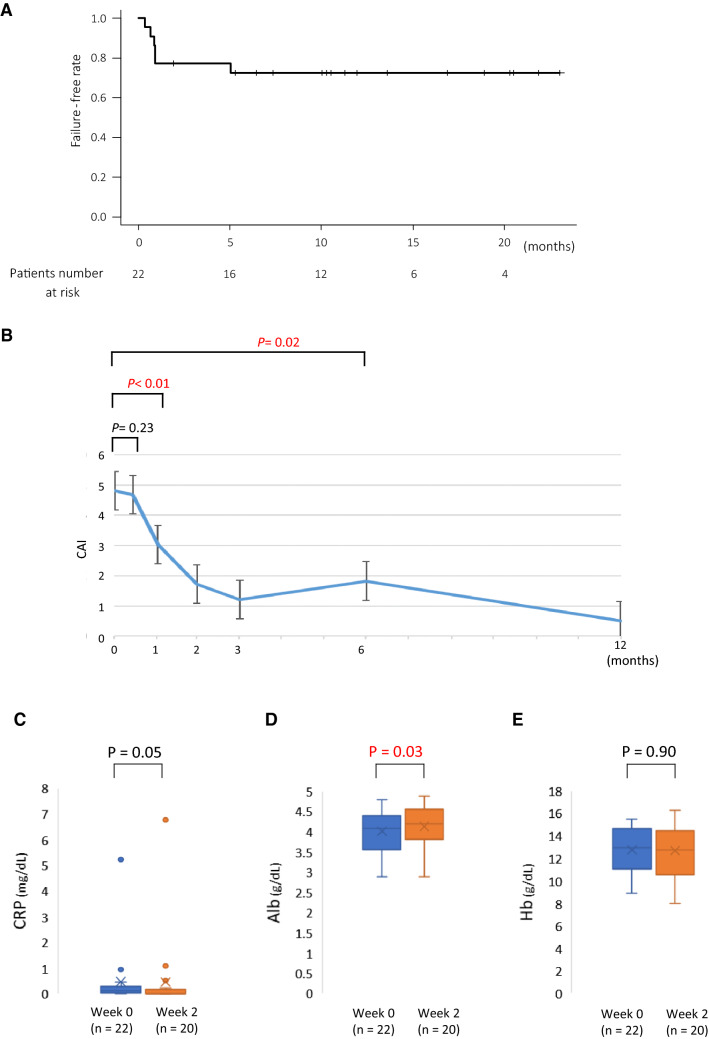

Changes in Failure-Free Rate, CAI, and Biomarkers with Tofacitinib

The failure-free rates with tofacitinib at 1 and 6 months were 77.3% and 72.4%, respectively (Fig. 1A). The median observation period in this study was 309.5 days. Five patients did not improve with tofacitinib within 1 month and were considered to have primary non-response. Although one patient demonstrated improvement after beginning the treatment, the patient failed to respond after 5 months and was adjudged to have secondary non-response. Therefore, 16/22 patients were determined to have non-failure, and the remaining six were determined to have failure to therapy. CAI did not improve significantly at week 2 in all patients but improved significantly at 1 month compared with the baseline (Fig. 1B). In 20 patients with available laboratory data, the data were compared between baseline and week 2. Although serum CRP level was not significantly different, it demonstrated an improving tendency, while serum Alb level showed a significant increase (P = 0.05, P = 0.03, respectively) (Fig. 1C, D). However, Hb levels did not demonstrated any significant change (P = 0.90) (Fig. 1E).

Fig. 1.

Failure-free rate following tofacitinib induction and changes in clinical activity index (CAI) and laboratory results in all enrolled patients. A Survival curve of failure-free patients after tofacitinib induction over time. B CAI changes in all enrolled patients following tofacitinib induction. The differences in serum levels of C-reactive protein (CRP) (A), albumin (Alb) (B) and hemoglobin (Hb) (C) between week 0 and week 2

Comparison of Non-failure and Failure with Tofacitinib

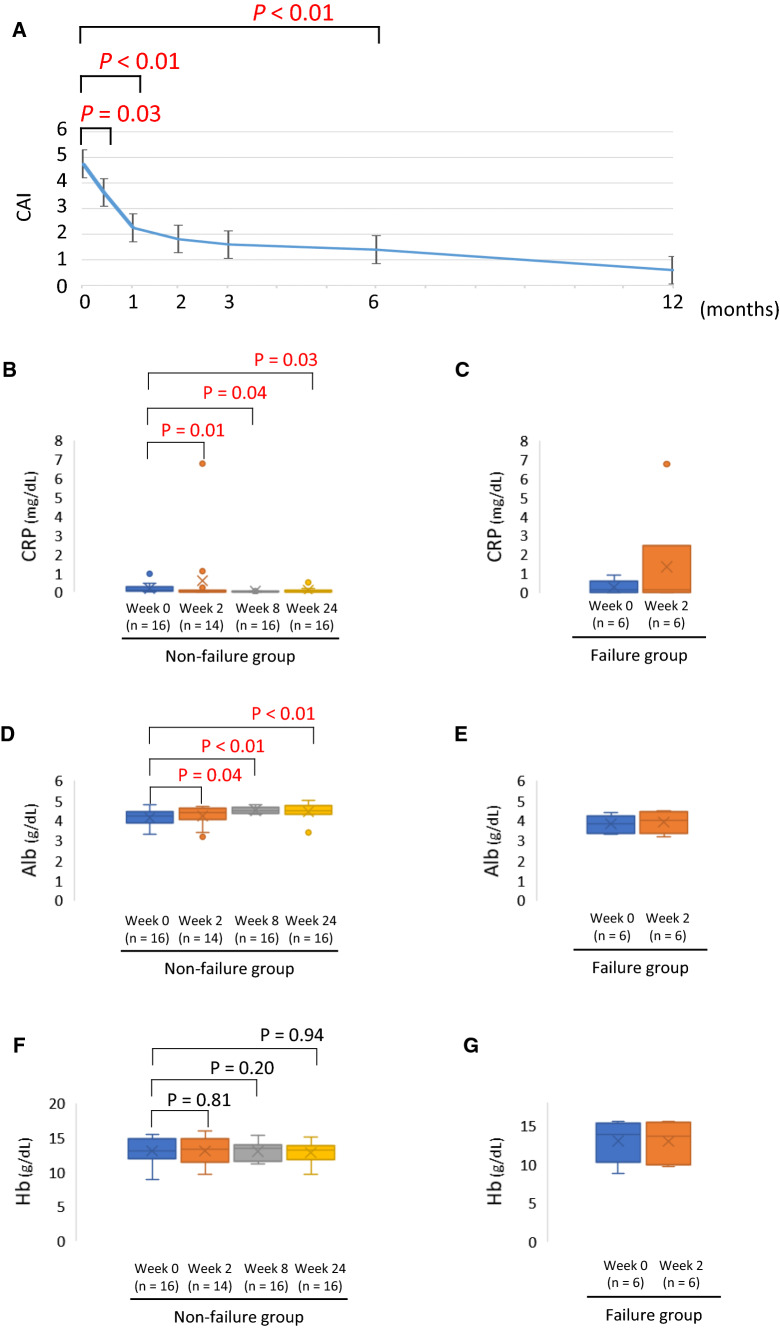

The 16 patients with non-failure and six patients with failure with tofacitinib treatment were compared (Table 2). Regarding the disease extent in the non-failure group, eight patients had extensive colitis, seven patients had left-sided colitis, and one patient had proctitis, whereas all patients in the failure group had extensive colitis. Significant differences were observed in the MES and UCEIS scores for the baseline endoscopic score. One patient had MES 0 in the failure group who was switched from GOL to tofacitinib due to the side effects of GOL. The CAI in the non-failure group demonstrated a significant improvement between week 2 and month 6 compared with baseline value (Fig. 2A).

Table 2.

Comparison of non-failure and failure with tofacitinib

| Characteristics at enrollment | Non-failure n = 16 |

Failure n = 6 |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 44.19 (16.33) | 50.00 (16.58) |

| Males/females, n (%) | 8/8 (50.0/50.0) | 5/1 (83.3/16.7) |

| Disease duration (years) | 8.18 (7.37) | 4.50 (6.63) |

| Disease extent | ||

| Extensive colitis | 8 (50.0) | 6 (100.0) |

| Left-sided colitis | 7 (43.8) | 0 (0.0) |

| Proctitis | 1 (6.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| CAI (Rachmilewitz index) | 4.75 (1.77) | 5.00 ± 2.19 |

| CRP (mg/dL) | 0.53 (1.28) | 0.30 (0.36) |

| Alb (g/dL) | 4.11 (0.50) | 3.83 (0.43) |

| Hb (g/dL) | 12.82 (1.76) | 13.02 (2.62) |

| MES | ||

| MES 0 | 0 (0.0) | 1 (16.7) |

| MES 1 | 6 (37.5) | 0 (0.0) |

| MES 2 | 9 (56.2) | 3 (50.0) |

| MES 3 | 1 (6.2) | 2 (33.3) |

| UCEIS | 3.62 (1.20) | 5.33 (1.03) |

| Other medications | ||

| Oral 5-ASA | 10 (62.5) | 3 (50.0) |

| Suppository steroids | 3 (18.8) | 0 (0.0) |

| Systemic steroids | 2 (12.5) | 1 (16.7) |

| History of biologics use | 7 (43.8) | 3 (50.0) |

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation or n (%)

CAI clinical activity index, CRP C-reactive protein, Alb albumin, Hb hemoglobin, MES Mayo endoscopic subscore, UCEIS ulcerative colitis endoscopic index of severity, 5-ASA 5-aminosalicylic acid

Fig. 2.

Changes in clinical activity index (CAI) in patients with non-failure and differences in the laboratory data between patients in non-failure group (week 0–24) and those in failure group (week 0–2) after tofacitinib induction. A CAI change in patients in non-failure group. The differences in serum level of C-reactive protein (CRP) between non-failure group (B) and failure group (C). The differences in serum albumin (Alb) levels between non-failure group (D) and failure group (E). The differences in blood hemoglobin (Hb) level between non-failure group (F) and failure group (G)

Changes in the laboratory results between the groups were examined. In the non-failure group, CRP demonstrated a significant improvement at week 2 and was maintained until week 8 and week 24 compared with the baseline value (Fig. 2B). The group with failure was evaluated up to week 2 due to treatment interruption. CRP, Alb, and Hb levels demonstrated no significant change at week 2 compared with the baseline values (Fig. 2C, E, G). Similar to CRP, Alb also demonstrated a significant improvement between week 2 and week 24 in the non-failure group compared with the baseline value; however, Hb did not demonstrate any significant change in any of the periods evaluated (Fig. 2D, F).

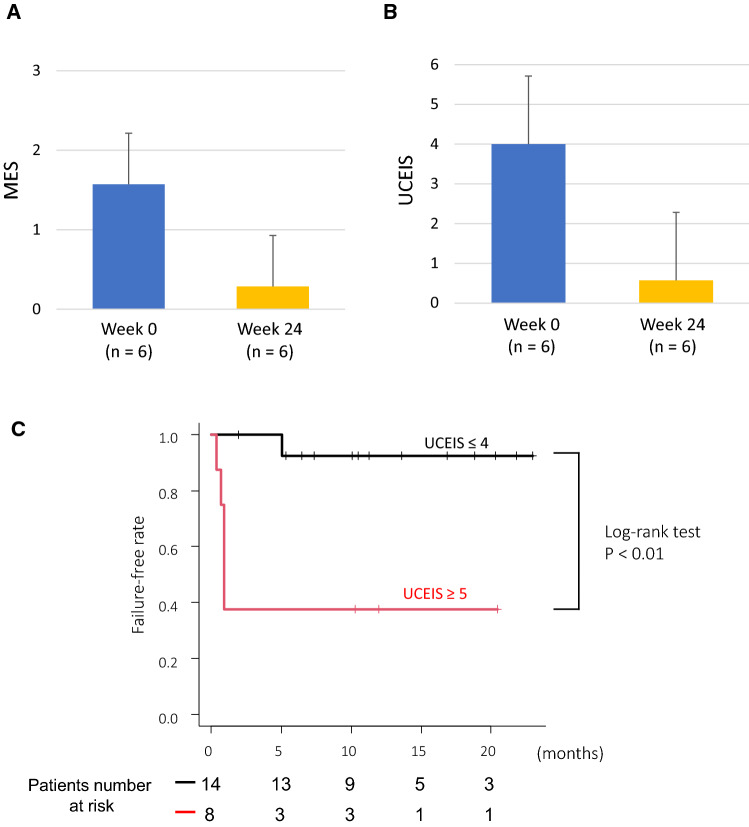

Endoscopic Evaluation in Tofacitinib Treatment

Changes in endoscopic scores were analyzed in six patients with non-failure who continued tofacitinib treatment for up to 6 months (Fig. 3A, B). Both MES and UCEIS demonstrated significant improvement 6 months after starting tofacitinib. Particularly, UCEIS had improved remarkably. Furthermore, we analyzed the failure-free rate by dividing patients into UCEIS ≥ 5 and UCEIS ≤ 4 groups (Fig. 3C). Of 14 patients in the UCEIS ≤ 4 group, one failed to respond to therapy. In contrast, of eight patients in the UCEIS ≥ 5 group, five failed to respond due to primary non-response. The failure-free rates of these two groups were significantly different according to Kaplan–Meier analysis (log-rank test, P < 0.01).

Fig. 3.

Changes in endoscopic score after tofacitinib induction between week 0 and week 24 and survival curves of failure-free rate after tofacitinib induction. The endoscopic changes in Mayo endoscopic subscore (MES) (A) and ulcerative colitis endoscopic index of severity (UCEIS) (B). C Kaplan–Meier curve of failure-free rate after tofacitinib induction between those with baseline UCEIS ≤ 4 versus those with baseline UCEIS ≥ 5

Discussion

In this study based on real-world experience, we analyzed the treatment continuity rate of tofacitinib in UC and investigated the factors that influence the same. The usefulness of tofacitinib in UC was demonstrated in the OCTAVE trial [13]. The basis of treatment in UC is induction and maintenance of remission, and the OCTAVE trial conducted a detailed analysis of induction and maintenance. We compared the effects of tofacitinib and laboratory tests in the OCTAVE trial and our study as much as possible. We tried to analyze the laboratory findings and endoscopic scores from a different perspective than that of the OCTAVE trial. In the OCTAVE trial, CAI was evaluated using the partial Mayo score. In our study, changes in the clinical symptoms were evaluated using CAI according to Rachmilewitz. Although no significant improvement was observed in CAI at 2 weeks after starting tofacitinib in all patients, CAI demonstrated a significant improvement in those with non-failure but not in those with failure to therapy. In the OCTAVE trial, CRP levels were assessed, while we evaluated changes in Alb and Hb in addition to CRP. In the group with failure, evaluation can be performed for up to only 2 weeks due to the early modification of treatments other than tofacitinib, and none of these parameters demonstrated significant changes at week 2. In contrast, in the non-failure group, CRP demonstrated a significant decrease and Alb demonstrated a significant increase 2 weeks after starting tofacitinib. Although CRP is a non-specific marker that reflects systemic inflammation, it is the commonest biomarker used in clinical practice of IBD. It has been reported that improvement in CRP within a short period of 2–4 weeks after starting treatment with IFX and ADA is associated with the subsequent prognosis in UC [19–22]. In particular, Iwasa et al. [20] reported that CRP changes 2 weeks after IFX induction in UC could predict the clinical prognosis. Our study demonstrated a significant improvement in CRP level only in the group with non-failure, thus, suggesting that CRP level 2 weeks after tofacitinib induction may contribute to the non-failure rate. Lee et al. [23] reported that the improvement in Alb level at week 2 after the induction of anti-TNF-α antibody preparation was associated with colectomy, endoscopic outcomes, and clinical outcomes. These results are similar to those in our study, which demonstrated a significant increase in albumin levels 2 weeks after the introduction of tofacitinib. As described above, it was demonstrated that the improvement in CRP and Alb levels at 2 weeks after induction may be predictor of long-term prognosis in the treatment of UC using biologics, including tofacitinib. In this study, the continuation rate at 6 months after tofacitinib induction was 72.4%. In the analysis of other studies, the tofacitinib continuation rate was 55–71%, which was relatively close to our data, and the data of this study were considered to be valid [24–27]. Furthermore, changes in the endoscopic scores were evaluated in six patients with non-failure who were observed for more than 6 months. Originally, 14 patients were followed up for > 6 months, but colonoscopy was not performed in eight patients in order to prevent the spread of COVID-19 infection; therefore, only six patients had endoscopic assessment data. In addition to MES evaluated in the OCTAVE trial, UCEIS was evaluated in our study. After 6 months of follow-up, both MES and UCEIS had significantly improved. As presented in Table 2, UCEIS demonstrated a significant difference between the group with and without failure. Therefore, evaluation using UCEIS may indicate the association of the subsequent therapeutic effects of tofacitinib. Therefore, we performed Kaplan–Meier analysis by dividing the patients according to baseline UCEIS ≥ 5 and UCEIS ≤ 4; a significant difference was observed in the failure-free rate between the groups. Although the data are not shown, Kaplan–Meier analysis according to baseline MES revealed no significant differences in this study.

It is a simple theory that lower endoscopic scores before treatment can be expected to be more effective in UC treatment. In this study, the baseline UCEIS score was particularly superior to baseline MES in predicting the subsequent prognosis, and the optimal cutoff value was UCEIS of 5. Several reports have compared MES and UCEIS before the beginning of treatment to examine the endoscopic scores that predict the clinical outcomes in UC [25–27]. Ruscio et al. [28] analyzed the endoscopic outcomes and need for colectomy prognosis using baseline MES and UCEIS in patients with UC treated with biologicals (IFX, ADA, GOL, and VDZ). They observed results similar to ours, UCEIS was better predictor of prognosis than MES although their study endpoint was not treatment continuation. Additionally, Ikeya et al. [29] reported that baseline UCEIS predicts clinical outcomes more accurately than MES in moderate-to-severe UC after the induction of tacrolimus. Xie et al. [30] performed predictive analysis of colectomy using UCEIS and MES to mainly target acute severe UC treated with steroid or cyclosporine therapy. UCEIS is better at predicting the need for colectomy than MES, and Xie et al. reported that its cutoff value was 7. This cutoff value is higher than the score of 5 in our study because we evaluated treatment continuity as the endpoint, while Xie et al. evaluated colectomy. In the OCTAVE trial, the endoscopic score was evaluated only using MES, and to our knowledge, there has been no report on predicting the clinical outcomes using endoscopic score in tofacitinib treatment in UC. It was demonstrated that UCEIS may predict the prognosis more accurately than MES in tofacitinib treatment, similar to other biologics.

This study had some limitations. First, this was a single-center study. Although it is easy to extract detailed laboratory results, the number of enrolled patients was small. Second, this was a retrospective study. Unlike in large clinical trials, there were no controls for the tofacitinib group in our study. In addition, tofacitinib was used as maintenance therapy for steroid dependence and refractory UC; hence, cases with not necessarily high clinical activity were included in this study. Third, biomarkers and histological evaluations before and after treatment were not examined. Fourth, colonoscopy and measurements of biomarkers, including fecal calprotectin, were not performed for the decision of failure. This is because most of the failures in this study were primary non-response, and it was estimated that there would be no significant change in these endoscopic scores or biomarker values in a short period of time. However, despite the small number of enrolled patients in this study, the fact that the Kaplan–Meier analysis demonstrated significant differences in non-failure rates between the groups based on UCEIS cutoff supports its effective prediction of the prognosis. Fifth, we selected the CAI score according to Rachmilewitz to assess clinical activity instead of other clinical scores, which are usually used in clinical practice and in IBD trials.

In conclusion, tofacitinib is a useful biological agent in the treatment of refractory UC. It was also demonstrated that UCEIS may be useful in predicting therapeutic response.

Author’s contribution

NI and KS designed the study. NI, KS, TM, ST1, and ST2 collected the data. MY, MI, and YH analyzed the data. NI and KS wrote the manuscript. SO and TF provided critical insights into paper preparation.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Hamamatsu University School of Medicine (approval number: 18-231), and the study was performed in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

The participants in this study were not required to provide informed consent because of the retrospective nature of the study and utilization of anonymous data.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Natsuki Ishida, Email: ma03006@hama-med.ac.jp.

Takahiro Miyazu, Email: tmiyazu@hama-med.ac.jp.

Satoshi Tamura, Email: tamura@hama-med.ac.jp.

Shinya Tani, Email: s-tani@hama-med.ac.jp.

Mihoko Yamade, Email: miyamade@hama-med.ac.jp.

Moriya Iwaizumi, Email: iwaizumi@hama-med.ac.jp.

Yasushi Hamaya, Email: yhamaya@hama-med.ac.jp.

Satoshi Osawa, Email: sososawa@hama-med.ac.jp.

Takahisa Furuta, Email: furuta@hama-med.ac.jp.

Ken Sugimoto, Email: sugimken@hama-med.ac.jp.

References

- 1.Podolsky DK. Inflammatory bowel disease. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:417–429. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra020831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Faubion WA, Jr, Loftus EV, Jr, Harmsen WS, et al. The natural history of corticosteroid therapy for inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based study. Gastroenterology. 2001;121:255–260. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.26279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khan NH, Almukhtar RM, Cole EB, et al. Early corticosteroids requirement after the diagnosis of ulcerative colitis diagnosis can predict a more severe long-term course of the disease—a nationwide study of 1035 patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;40:374–381. doi: 10.1111/apt.12834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garcia-Planella E, Mañosa M, Van Domselaar M, et al. Long-term outcome of ulcerative colitis in patients who achieve clinical remission with a first course of corticosteroids. Dig Liver Dis. 2012;44:206–210. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2011.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Turner D, Walsh CM, Steinhart AH, et al. Response to corticosteroids in severe ulcerative colitis: a systematic review of the literature and a meta-regression. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:103–110. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gustavsson A, Halfvarson J, Magnuson A, et al. Long-term colectomy rate after intensive intravenous corticosteroid therapy for ulcerative colitis prior to the immunosuppressive treatment era. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:2513–2519. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01435.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Truelove SC, Witts LJ. Cortisone in ulcerative colitis; final report on a therapeutic trial. Br Med J. 1955;2:1041–1048. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.4947.1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baron JH, Connell AM, Kanaghinis TG, et al. Out-patient treatment of ulcerative colitis. Comparison between three doses of oral prednisone. Br Med J. 1962;2:441–443. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.5302.441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rutgeerts P, Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, et al. Infliximab for induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2462–2476. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sandborn WJ, van Assche G, Reinisch W, et al. Adalimumab induces and maintains clinical remission in patients with moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2012;142(257–265):e1–e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Marano C, PURSUIT-SC Study Group et al. Subcutaneous golimumab induces clinical response and remission in patients with moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:85–95. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.05.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sands BE, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Loftus EV, Jr, VARSITY Study Group et al. Vedolizumab versus adalimumab for moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1215–1226. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1905725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sandborn WJ, Su C, Sands BE, et al. OCTAVE induction 1, OCTAVE induction 2, and OCTAVE sustain investigators. Tofacitinib as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1723–1736. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1606910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sands BE, Sandborn WJ, Panaccione R, UNIFI Study Group et al. Ustekinumab as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1201–1214. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1900750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Magro F, Gionchetti P, Eliakim R, European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation [ECCO] et al. Third European evidence-based consensus on diagnosis and management of ulcerative colitis. Part 1: definitions, diagnosis, extra-intestinal manifestations, pregnancy, cancer surveillance, surgery, and ileo-anal pouch disorders. J Crohns Colitis. 2017;11:649–670. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjx008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rachmilewitz D. Coated mesalazine (5-aminosalicylic acid) versus sulphasalazine in the treatment of active ulcerative colitis: a randomised trial. BMJ. 1989;298:82–86. doi: 10.1136/bmj.298.6666.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schroeder KW, Tremaine WJ, Ilstrup DM. Coated oral 5-aminosalicylic acid therapy for mildly to moderately active ulcerative colitis. A randomized study. N Engl J Med. 1987;317:1625–1629. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198712243172603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.D’Haens G, Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, et al. A review of activity indices and efficacy end points for clinical trials of medical therapy in adults with ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:763–786. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.12.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ferrante M, Vermeire S, Fidder H, et al. Long-term outcome after infliximab for refractory ulcerative colitis. J Crohns Colitis. 2008;2:219–225. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2008.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iwasa R, Yamada A, Sono K, et al. C-reactive protein level at 2 weeks following initiation of infliximab induction therapy predicts outcomes in patients with ulcerative colitis: a 3 year follow-up study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2015;15:103. doi: 10.1186/s12876-015-0333-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morita Y, Bamba S, Takahashi K, et al. Prediction of clinical and endoscopic responses to anti-tumor necrosis factor-α antibodies in ulcerative colitis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2016;51:934–941. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2016.1144781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hanauer S, Sandborn WJ, Colombel JF, et al. Rapid changes in laboratory parameters and early response to adalimumab: a pooled analysis from patients with ulcerative colitis in two clinical trials. J Crohns Colitis. 2019;13:1227–1233. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjz031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee SH, Walshe M, Oh EH, et al. Early changes in serum albumin predict clinical and endoscopic outcomes in patients with ulcerative colitis starting anti-TNF treatment. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2020;27:1452–1461. doi: 10.1093/ibd/izaa309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weisshof R, Aharoni Golan M, Sossenheimer PH, et al. Real-world experience with tofacitinib in IBD at a tertiary center. Dig Dis Sci. 2019;64:1945–1951. doi: 10.1007/s10620-019-05492-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Biemans VBC, Sleutjes JAM, de Vries AC, et al. Tofacitinib for ulcerative colitis: results of the prospective Dutch Initiative on Crohn and Colitis (ICC) registry. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2020;51:880–888. doi: 10.1111/apt.15689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Honap S, Chee D, Chapman TP, et al. Real-world effectiveness of tofacitinib for moderate to severe ulcerative colitis: a multicentre UK experience. J Crohns Colitis. 2020;14:1385–1393. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjaa075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chaparro M, Garre A, Mesonero F, et al. Tofacitinib in ulcerative colitis: real-world evidence from the ENEIDA registry. J Crohns Colitis. 2021;15:35–42. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjaa145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Di Ruscio M, Variola A, Vernia F, et al. Role of ulcerative colitis endoscopic index of severity (UCEIS) versus Mayo endoscopic subscore (MES) in predicting patients’ response to biological therapy and the need for colectomy. Digestion. 2021;102:534–545. doi: 10.1159/000509512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ikeya K, Hanai H, Sugimoto K, et al. The ulcerative colitis endoscopic index of severity more accurately reflects clinical outcomes and long-term prognosis than the Mayo endoscopic score. J Crohns Colitis. 2016;10:286–295. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjv210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xie T, Zhang T, Ding C, et al. Ulcerative colitis endoscopic index of severity (UCEIS) versus Mayo endoscopic score (MES) in guiding the need for colectomy in patients with acute severe colitis. Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf). 2018;6:38–44. doi: 10.1093/gastro/gox016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]