Abstract

Background: Indigenous women in New South Wales Australia are nearly four times more likely to die from cervical cancer than non-Indigenous women due to lower screening rates. We aimed to understand Indigenous women's cervical screening awareness, behaviours, knowledge, perceptions, motivators and barriers since the December 2017 National Cervical Screening Program changed to HPV testing, new screening age and screening interval, and introduced the new self-collection test.

Methods: A qualitative study was conducted with 94 Indigenous women 25 to 74 years of age across metropolitan, regional and remote New South Wales. A team of six specialist researchers conducted the fieldwork, analysis and reporting. All data were coded thematically.

Findings: Participants showed limited awareness of the renewed cervical screening program and the role of cervical screening in cervical cancer prevention, with most having a strong negative attitude towards cervical screening. Several motivators and behavioural barriers to screening were identified into four audience segments based on key characteristics. Most participants eligible to self-collect were unwilling to, due to concerns they would administer it incorrectly, injure themselves or have to return for a more invasive test.

Interpretation: This study demonstrates the complex and heterogenous nature of attitudes and behaviours, among Indigenous women and highlights the intrinsic negative attitudes and social norms that are currently shaping community discourse and ultimately limiting screening. Our findings support the need for enhancing positive sentiment and community advocacy.

Funding: Cancer Institute NSW Cervical Screening Program

Keywords: cancer, cervical screening, Cervical Screening Test, HPV self-collection, Australian Aboriginal women, participation rates

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

In Australia, Indigenous women are twice as likely to develop and four times more likely to die from cervical cancer than non-Indigenous women. These poorer cancer outcomes are likely due to the lower rates of cervical screening among Indigenous women and later presentation of symptomatic Indigenous women to health care services. The National Cervical Screening Program in Australia underwent major changes on 1 December 2017. The program changed from the Pap Test to the Cervical Screening Test for HPV, the screening interval increased from every two years to every five years, the screening age range changed from 18-69 years to 25-74 years, plus the introduction of self-collection and the new National Cancer Screening Register to send women invitations and reminders for cervical screening tests. Due to the significant changes that have occurred to the National Cervical Screening Program known as the ‘Renewal’ there was a need to conduct formative research with Indigenous women about cervical screening to understand how the program changes have affected screening knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, intentions and behaviours. Before this study, we searched Pubmed, Medline, Proquest and Google Scholar to identify studies that explored reasons for lower participation in cervical screening amongst Australian Indigenous women. We found limited literature from pre ‘Renewal’ and only one study post ‘Renewal’. The study post ‘Renewal’ explored and reported upon the views from Australian Indigenous women who regularly participated in the National Cervical Screening Program. To the best of our knowledge this study is the only one post ‘Renewal’ that explores the views of Australian Indigenous women who are under-screened or who have never had a cervical screen.

Added value of this study

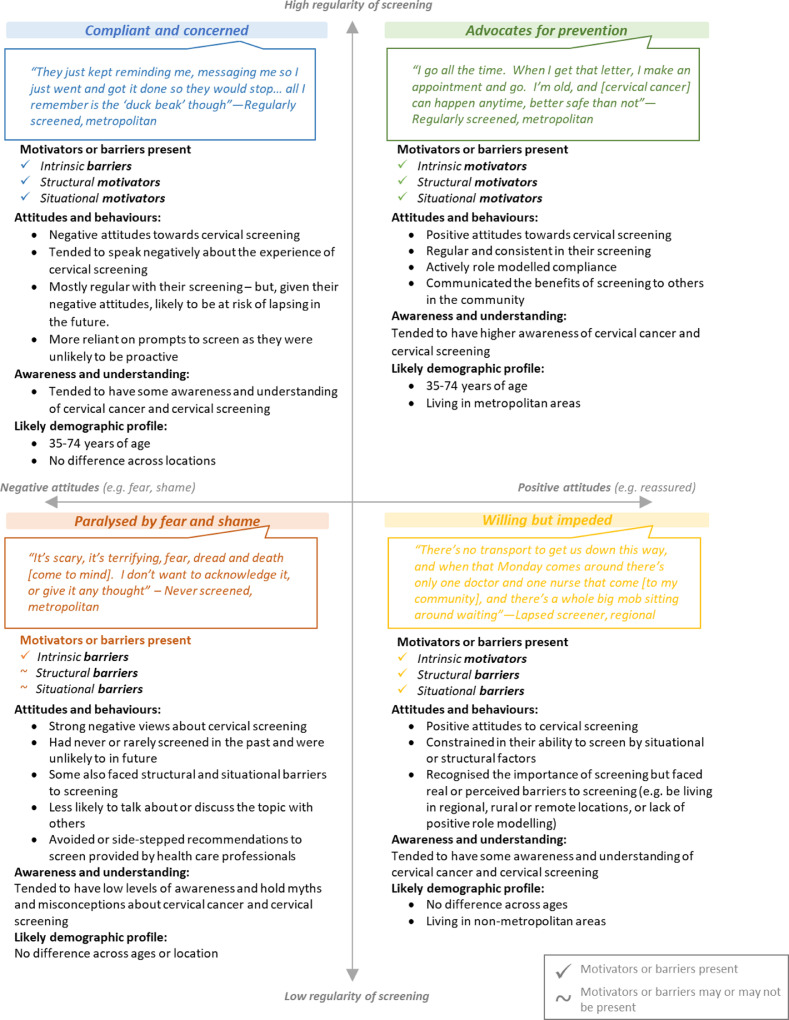

We found that there is superficial awareness and understanding among Australian Indigenous women about cervical screening and the renewed program which propagates myths and misconceptions. In addition, negative emotions, attitudes and community norms contributed to the taboo and stigmatised nature and perceptions of the topic, which in turn limited positive screening practices, advocacy and role modelling of desired attitudes and behaviours. The study found there are additional structural and situational barriers which also hinder access to services. As a result of these barriers, screening behaviours are ad-hoc and/or avoidant and the onus on healthcare professionals to engage, educate and encourage compliance can be burdensome. We showed that, in terms of screening behaviour and behavioural intentions, the target audience could be grouped into four segments: compliant and concerned; advocates for prevention; willing but impeded; and paralysed by fear and shame. This segmentation could inform targeted approaches to engage Australian Indigenous women in cervical screening. We further identified that there were barriers that decreased the willingness of study participants to choose the self-collection option.

Implications of all the available evidence

Our results indicate there is a clear need for targeted, integrated and ongoing communications via a social marketing campaign. The exposure of information to participants through the research process had notable and reported gains in knowledge and awareness, positivity of attitudes and discussions surrounding the topics as well as increased intention to undergo cervical screening. Our study makes the case for a holistic engagement strategy that includes additional educational and professional development opportunities in addition to policy and service delivery responses. These will assist in addressing the structural and to a lesser extent the situational barriers faced by Australian Indigenous women in relation to cervical screening.

Alt-text: Unlabelled box

1. Introduction

Preventing cervical cancer is possible with the Human Papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination and regular cervical screening [1]. In Australia, the National Cervical Screening Program (NCSP) was established in 1991 and since that time both incidence of and mortality from cervical cancer has declined by half [2]. In 2014 after comprehensive review of the evidence for cervical screening the Australian Government Medical Services Advisory Committee recommended significant changes to the NCSP which are expected to prevent up to 30% more women from developing cervical cancer [3]. The changes, known as ‘the Renewal’, commenced on 1 December 2017 and included: the Cervical Screening Test for HPV to replace the Pap Test, the screening interval to increase from every two years to every five years, the screening age range to change from 18-69 years to 25-74 years, the new National Cancer Screening Register (NCSR) to send women invitations and reminders for Cervical Screening Tests and the introduction of HPV self-collected vaginal samples [3]. Self-collection is available for women who are between 30-74 years of age and who are either overdue by two or more years or who have never participated in the NCSP. Self-collection is offered under supervision of a health care professional who also provides cervical screening [4].

In Australia, there are two distinct indigenous populations, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders (hereafter respectfully referred to as Indigenous) and identified within these two populations are over 250 language or nation groups with differing laws and customs [5]. In Australia, Indigenous people account for 3•3% of the total population of around 24 million, of whom 37% live in major cities, 44% in regional areas and 19% in remote areas [6]. A third of the total national Indigenous population lives in the Australian state of New South Wales (NSW) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Indigenous population locations. Source: Copied from Figure 2.5 in The health and welfare of Australia's Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples 2015. Cat. No. IHW 147. Canberra: AIHW. https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/584073f7-041e-4818-9419-39f5a060b1aa/18175.pdf.aspx?inline=true [accessed 14 April 2020]. Indigenous population clusters 2011. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare.

Australian national data on cervical screening participation rates among Indigenous women are not available. Regional data sources indicate that around 30% of Indigenous women participate regularly in the NCSP compared with around 53% of the general population across Australia [7], [8], [9]. For all women diagnosed with invasive cervical cancer, around 80% were either never screened or were under-screeners prior to their diagnosis [9], [10]. Lower cervical screening rates may explain why Indigenous women are twice as likely to develop and nearly four times more likely to die from cervical cancer than non-Indigenous women [1], [10],11].

Published literature that explores the reasons for lower participation in the NCSP among Indigenous women is limited and mostly pre ‘Renewal’. Research with Indigenous women over the last 20 years identifies that geographical location and age impact on cervical screening behaviour and most reports are from single communities [9,[12], [13], [14].

The aim of this research was to understand cervical screening awareness and knowledge among Indigenous women of NSW, their perceptions of the changes to the NCSP including the introduction of self-collection, the social norms and their attitudes towards cervical screening, their motivators and barriers to cervical screening, their cervical screening behaviours and behavioural intentions. The purpose of the research is to inform program activities, access and service delivery models about what is important for Indigenous women of NSW, what is likely to increase their intention and capacity to participate in the NCSP so as to reduce the incidence of cervical cancer among Indigenous women.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design and context

Qualitative research was conducted by ORIMA Research, an Australian research consultancy that specialises in conducting social marketing and communications research, with extensive experience conducting research with and for Australia's First Nations communities, on behalf of the Cancer Institute NSW. It was conducted in metropolitan, regional and rural locations across NSW.

A total of 94 women participated in the research (Table 1). All research was conducted face-to-face between 21 October and 19 November 2019.

Table 1.

Breakdown of participation

| Methodology | Number of participants per session | Total Number of participants |

|---|---|---|

| 6 x mini-focus groups | 3 - 6 | 30 |

| 6 x focus groups | 7 - 10 | 49 |

| 6 x kinship paired interviews | 2 | 12 |

| 3 x in-depth interviews | 1 | 3 |

| Total | 94 |

A flexible approach was taken that prioritised participant comfort, with the variety of research methods including smaller and larger focus groups and interviews enabling participants to choose how they wished to participate in the research. Participants who did not feel comfortable participating in a group environment (i.e. through a focus group) were offered the opportunity to instead partake in in-depth interviews or kinship paired interviews (which were conducted with women from the same family, household, or close friendship group). The latter of these also allowed for observation and exploration of how the subject was dealt with and discussed in these kinship groups, and what impacts such conversations and influencers had on personal attitudes, perceptions and behaviours. Research participants received a reimbursement payment of AUD$80 to cover their time and expenses to attend focus groups of up to 1.5 hours in duration, or an interview of up to 1 hour in duration.

The project was approved by the Aboriginal Health & Medical Research Council of NSW Human Research Ethics Committee (Reference number 1511/19).

2.2. Inclusion and exclusion

The research population was women living in NSW who identified as Aboriginal and / or Torres Strait Islander and aged between 24 and 74 years. The sample included women from a range of metropolitan, regional and remote locations, of different ages and with different screening experiences. This included ‘regular screeners’ who had screened in the past three years; ‘lapsed screeners’ who had not screened for more than three years; and women who had never been screened, with a greater focus placed on recruiting participants in the latter of these groups so as to understand barriers to participation in cervical screening (refer to Results for characteristics of research participants). Women were excluded if they were not in the target age range, had participated in market research in the previous six months or had a total hysterectomy.

2.3. Data collection and analysis

Participants were contacted and invited to participate by ORIMA Research's Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community-based interviewers, through local community organisations and a local specialist qualitative recruitment organisation. The research sessions were conducted by ORIMA's specialist qualitative researchers, who are not Indigenous but who have undergone appropriate training and have extensive experience in conducting research with Indigenous audiences (PMo, LD and assisting researchers). These qualitative researchers were also accompanied by local Indigenous community interviewers at many of the research sessions.

Where possible, research was conducted at local community centres or organisations to assist in creating a culturally safe and comfortable environment to facilitate open and honest discussion about feelings, perceptions and experiences. A flexible, time-rich approach, in which researchers spent extended time on location (up to two days), was taken to provide participants the opportunity to be involved in the research when and how it suited them (e.g. participants could inform the researchers if they were more comfortable attending a one-on-one interview rather than a focus group, and participate accordingly). A participant information sheet was provided to participants prior to research being conducted, and this was verbally discussed by the moderator at the start of each session to ensure it was understood by the participants. Prior to participating in the research, participants provided verbal consent to the information provided being used in a de-identified form, in line with ethics processes. In addition, a summary of the key research findings and results were provided back to communities who attended the research to provide reciprocity and information sharing.

All focus groups and interviews were semi-structured to allow flexibility to explore the issues raised by participants. Key areas explored in the research included:

-

•

Awareness, understanding, perceptions of and attitudes to cervical cancer, the Cervical Screening Test and the ‘Renewal’ changes

-

•

Sources of information and influencers in relation to Cervical Screening Tests

-

•

Current screening behaviours

-

•

Motivators and barriers to screening and attending specialist appointments

-

•

Awareness, understanding and perceptions of self-collection and self-efficacy and behaviours in relation to self-collection.

A systematic manual approach was taken to the analysis. The same team of six specialist qualitative researchers conducted all the fieldwork, analysis and reporting (with each session conducted with at least one senior researcher present, and each researcher visiting at least two different research locations) to ensure the analysis was done with the full appreciation and understanding of the context in which responses were provided (e.g. non-verbal cues, cultural sensitivities, language and tone) (PMo, LD and assisting researchers). Furthermore, this approach maximised consistency and opportunities for cross-validation in relation to the collection and interpretation of data. Extensive verbatim notes were taken by a note-taker during the focus groups and interviews. At the conclusion of research at each location, researchers produced a summary of findings and key themes in relation to the main areas of investigation. These outputs were cross checked and validated by other researchers who had attended the same sessions. Weekly analysis sessions were attended by all researchers (led by PMo, LD and another assisting senior researcher involved in the project) to maximise the quality of the analysis. These involved thematic coding of research results, which formed the basis for building on and validating emerging findings and insights. As the research progressed, key themes were iteratively developed and refined.

Table 2 lists the terms used in the report to provide a qualitative indication and approximation of size of the sample who held particular views.

Table 2.

Approximation of size of the research sample who held particular views

| Term | Approximation of sample size |

|---|---|

| Most | Refers to findings that relate to more than three quarters of the research participants |

| Many | Refers to findings that relate to more than half but less than three quarters of the research participants |

| Some | Refers to findings that relate to less than half but more than a quarter of the research participants |

| Few | Refers to findings that relate to less than a quarter of research participants |

2.4. Role of the funding source

The funder of the study, Cancer Institute New South Wales had a role in study design, data interpretation and providing feedback on the report. The corresponding author and all other authors had full access to all the de-identified data in the study and take responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

3. Results

3.1. Demographics of the research sample

Table 3 shows key characteristics of the 94 Aboriginal women who participated in the research. This demographic data was collected to ensure the sample was appropriately representative of the target population.

Table 3.

Participant characteristics

| Characteristics | Percentage of participants | Number of participants | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||

| Youngera | 24 – 35 years | 42% | 39 | |

| Older | 36 – 74 years | 58% | 55 | |

| Screening Status | ||||

| Never been screened | 30% | 28 | ||

| Lapsed in screening | 40% | 38 | ||

| Up to date with screening | 30% | 28 | ||

| Locationb | ||||

| Metropolitan | 34% | 32 | ||

| Regional | 50% | 47 | ||

| Remote | 16% | 15 | ||

| Highest level of educationc | ||||

| Under year 10 | 40% | 35 | ||

| Year 10 or equivalent | 25% | 22 | ||

| Year 11 or equivalent | 7% | 6 | ||

| Year 12 or equivalent | 10% | 9 | ||

| TAFE, Diploma or Certificate | 11% | 10 | ||

| University – undergraduate | 6% | 5 | ||

| Identified as Eldersd or Traditional Ownerse | 11% | 10 | ||

Younger participants included those aged from 24 years because they will be eligible to screen in 9 months or less and therefore deemed a critical audience for programs and communications relating to the topic.

Location definitions are based on the Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2016 Australian Statistical Geography Standard remoteness area classifications.

Participants only answered the questions they felt comfortable answering, so not all participants chose to answer the question on highest education level.

An Elder is someone who has gained recognition as a custodian of knowledge and lore, and who has permission to disclose knowledge and beliefs.

Traditional Owners have ongoing traditional and cultural connections to country.

3.2. Awareness and knowledge of cervical screening

Most participants had heard of a ‘pap test / smear’ (no participants referred to the test by the newer ‘cervical screening’ terminology), and many were aware that women who were sexually active should screen. However, there was limited awareness overall as to what age women should start screening, the new recommended screening frequency and details of the screening procedure. The procedure was particularly unclear amongst those who had not been previously screened, with a few believing a part of the cervix would be “cut out”.

“In my mind it's [cervical screening test] some hook that scrapes your flesh out”—Never screened, regional

The research also found limited awareness of cervical cancer more generally, including causes, risk factors, its often-asymptomatic nature and the role of the HPV vaccination in prevention.

“Oh, there's no symptoms? That's good to know!”—Never screened, metropolitan

Most participants had received limited information about cervical cancer and cervical screening and were unlikely to search for this information themselves, with most instead preferring targeted information and education (e.g. through social marketing campaigns). The changes as a result of the ‘Renewal’ were found to add to participants’ confusion, increasing the number of myths and misconceptions and reducing clarity as to what the recommendations were for women.

3.3. Perceptions of ‘Renewal’ changes

Cervical screening was perceived to be the most difficult and intrusive preventative health screen due to privacy of the cervical region and the invasive nature of the test. As such, when participants were provided with information about the ‘Renewal’ changes, most reported that the reduction in screening frequency was appealing.

However, in the absence of information as to why these changes had been enacted, a few participants expressed concerns about the impact of the older start age and the reduced frequency of testing. In particular, a few participants reported they knew of younger community members who had died of cervical cancer (i.e. in their early 20s) and were concerned for the safety of young women who commenced sexual activity in their early teens and were not tested until 25 years of age under the ‘Renewal’ changes.

3.4. Attitudes towards screening

Most participants had strong negative attitudes towards cervical screening. These attitudes were themed around shame and fear (Table 4).

Table 4.

Attitudes towards cervical screening and contributing factors

| Attitude | Contributing Factors | Quotes from Participants |

|---|---|---|

| Shame | The invasion of privacy | “Black fellas are scared of the privacy issue first…I'd look at the curtains |

| and say ‘I can see a gap there; I know people can see me through that’” | ||

| – Lapsed screener, regional | ||

| Embarrassment and low body | “I feel uncomfortable taking my clothes off and opening my legs for the | |

| confidence | white doctors, including the women. I feel like we are different down | |

| there and they're judging me” – Lapsed screener, metropolitan | ||

| Dealing with trauma | “If they've been a victim of sexual assault they're not going to go in - they | |

| feel violated. We do have a lot of PTSD and transference of trauma” | ||

| -Lapsed screener, metropolitan | ||

| Feeling defiled | “We were always told not to show our private parts…close your legs, sit | |

| properly…then you go to the doctor and they say ‘alright, open your legs’” | ||

| -Lapsed screener, metropolitan | ||

| The suggestion of promiscuity / | “Some women think they get cancer from having sex, so they get | |

| sexual deviance | embarrassed and don't get it treated right away” – Regularly screened, | |

| regional | ||

| Fear | Death or incapacitation | “I'm too terrified, I don't want to try anymore…I'm terrified of what the |

| outcomes are going to be” – Lapsed screener, metropolitan | ||

| Pain | “The doctors at [the clinic] are rough and painful, they're not experienced” | |

| -Lapsed screener, metropolitan | ||

| The unknown / not knowing | “All these contraptions you hear about…I'll just die instead” - never | |

| how the test is conducted | screened, remote |

A few participants however, particularly those with better understanding of cervical cancer and its prevention, held positive attitudes towards cervical screening. These participants described the responsibility they felt to stay healthy (particularly in their role as a caregiver to others) and thought of the test as something that provided peace-of-mind and reassurance:

“Now I get it regularly… I just thought if I'm having sex, I want to make sure everything is safe”—Regularly screened, remote

3.5. Social norms

Based on participants’ responses and interactions observed by the researchers during focus groups and kinship paired interviews, it was evident the attitudes of most participants were strongly influenced by social norms and the behaviours of their direct reference group:

“It's a shame thing. As kids we weren't able to talk about that”—Never screened, metropolitan

“Their mum has never had one [cervical screening test], so they've never had one”—Never screened, metropolitan

Participants reported that, unlike many other topics considered to be ‘women's business’, cervical cancer was not commonly discussed amongst females in the community. This lack of discourse was found to be due to the intersection of cervical cancer and screening with three ‘taboos’ or stigmatised topics. These were:

-

1

Cancer, sickness and death. Most participants feared this and reported that cancer itself was rarely discussed, even when someone was undergoing treatment.

-

2

Private parts of the body. Many participants felt uncomfortable discussing the topic given the privacy of the cervical region, even with close family members. It was felt to be a very personal choice and therefore many felt it would be inappropriate to suggest to others that they be screened.

-

3

Issues to do with sex. Some participants did not feel comfortable discussing issues related to sex with others, particularly those outside their close reference group, and noted the stigma associated with sexual activity in their community. In addition, a few participants reported direct or indirect experience with sexual assault and noted that it would be a particularly sensitive topic to discuss with those who had experienced assault.

Participants reported that important influencers about this topic included family and friends, community leaders or Elders, healthcare professionals, the wider community, the media and schools. However, currently many of these channels were found to be underutilised. For example, during the research sessions, while Elders in some locations expressed a strong desire to be involved in educating the community about the topic, it was not currently felt to be promoted or advocated for by many Elders due to the associated stigma. In addition, many participants reported that the wider community (including male partners, family members or friends) engaged largely in negative discourse about the topic (e.g. by “laughing at” women, asking intrusive questions or using crass language to describe screening), which amplified negative attitudes and enhanced the stigma.

3.6. Motivators and barriers to cervical screening

Key motivators and barriers to screening behaviours identified by participants are shown in Table 5. They are grouped into three broad categories: intrinsic factors (i.e. individual awareness, perceptions and attitudes), situational factors (i.e. an individual's environment or direct experience) and structural factors (i.e. the accessibility of appropriate screening).

Table 5.

Motivators and barriers to cervical screening

| Factor | Motivator | Participant Quote |

|---|---|---|

| Intrinsic | Having good awareness and knowledgef, including through communications and information | “If we're four times more likely to die, why don't we have a specific ad for us?”—Lapsed screener, metropolitan |

| Perceiving screening to be | “You could be silently dying and not know it…I think it's good to have that | |

| important | peace of mind” – Never screened, metropolitan | |

| Situational | A past positive screening | “The nurse gave a lot of detail that was great, it makes you at ease knowing |

| experience | what's going on” – Regularly screened, regional | |

| Key influencers / support | “We go get it done together, we are each other's support person…I'm the older | |

| provided | cousin and she's very shy so I go be there with her because she doesn't like | |

| doing things on her own” – Regularly screened, regional | ||

| Structural | Having ease of access to | “I go to [the Aboriginal Medical Service] because of the transport” – Regularly |

| healthcare services (and | screened, regional | |

| childcare to facilitate this | ||

| access) | ||

| Attending a proactive and | “Once you've had your first pap test you get a reminder…they chase you up, | |

| culturally appropriate | that's a good thing” – Regularly screened, regional | |

| healthcare service (eg: where | ||

| opportunistic screening and | ||

| trauma informed care are | ||

| offered) | ||

| Having the option of where | “[The Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Service] is more comfortable, | |

| to be screened and by whom | you can just walk in. You don't need to make an appointment” - Lapsed | |

| (particularly in a private and | screener, metropolitan | |

| female focussed | ||

| environment) | ||

| Factor | Barrier | Participant Quote |

| Intrinsic | The prevalence of negative | “I was abused as a child so that's why I don't like the pap smear” – Never |

| emotions and attitudes | screened, metropolitan | |

| associated with the topic | ||

| Not prioritising preventative | “The last time I saw a doctor was 12 months ago…there's no time to get sick | |

| health measures | when you have kids, we're just so busy” – Lapsed screener, regional | |

| Situational | Past negative experiences | “They just don't care…I refuse to go…I'd rather lay down and die” - Lapsed |

| (including medical | screener, remote | |

| conditions enhancing the | ||

| pain and lack of culturally | ||

| safe approaches) | ||

| Lack of positive role | “I asked my sister about it and she said they put the claws into your vagina…I | |

| modelling | don't know if I want to get it done now” – Never screened, metropolitan | |

| Unsupportive and / or | “Partners may not let them go because of jealousy” – Lapsed screener, regional | |

| abusive partners | ||

| Structural | Not having access to medical | “Transport is a big thing for a lot of people especially in this town, if you don't |

| services (eg: childcare and | have a car you can't get anywhere” – Never screened, regional | |

| transport) | ||

| Not receiving reminders or | “I don't own a phone” – Lapsed screener, regional | |

| being prompted |

ORIMA's Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community interviewers, as well as community organisations who assisted with recruitment, reported back to ORIMA consultants following the research in most locations to indicate the positive impact that exposure to information and discussion on the topic had on participants, including improvements in their awareness and understanding, as well as more positive attitudes, the continuation of discussions in community, increased intention to undergo cervical screening and / or follow up on their own or their children's HPV vaccination.

The following barriers were also identified to seeking follow-up care after an HPV positive result, amongst the few participants who had experienced this:

-

•

Lack of support, guidance and / or reassurance from healthcare professionals, which had amplified negative emotions and attitudes for a few, and

-

•Not having access to appropriate specialist services, particularly in regional and remote locations where services were significant distances away, or the only available specialist was a male, which increased feelings of discomfort.“In this town you have to go to Sydney [for the specialist]. You have to pay, so then it's the cost”—Lapsed screener, regional

3.7. Cervical screening behaviours and behavioural intentions

Differences in intended screening behaviours were found to be driven more by participants’ attitudes and the presence or absence of various motivators and barriers at the time of screening than by their past screening behaviours (e.g. even if someone was currently up to date with their screening, this did not necessarily indicate that they would screen again in the future).

A segmentation approach was applied to better understand the audience and target effective interventions accordingly. In the qualitative segmentation presented in Figure 2, which was developed from the research findings, each quadrant represents a segment of the participant sample. The key characteristics of each segment are summarised and a supporting quote is presented from participants within each segment.

Figure 2.

Attitudinal and behavioural segmentation of sample. Source: ORIMA Research Pty Ltd.

3.8. Self-collection of a vaginal sample for HPV testing

Most participants who were eligible had not heard of or been offered self-collection by healthcare professionals. Upon exposure to information about self-collection during the research, only a few participants reported that they personally would wish to self-collect and / or had done so already.

Many participants were unwilling to self-collect due to concerns that they would incorrectly administer it and either injure themselves or need to return for a more invasive test.

“I'd be worrying in the back of my mind whether I did the swab right. There's no point doing it yourself if you're doing it wrong”—Lapsed screener, regional

However, the few women who reported that they were interested in self-collection were more likely to have never screened or be longer-term lapsed in their screening (e.g. in the ‘Paralysed by fear and shame’ Segment), and hence harder to reach through other methods.

“Yeah, I like that! That's what I've been waiting for… even for someone who's never done it, I would do that”—Never screened, remote

Despite the limited number of participants who would opt to self-collect, most were supportive of its implementation. They felt that the additional option could increase their autonomy and control in the process and also provide a more private and personal approach, which could be particularly useful for those who may have experienced past trauma or assault.

It was also felt that self-collection may be an effective way to introduce some younger women, who currently avoided screening, to the process. Participants felt that this may increase their comfort with the process and lead them to screen via a healthcare professional collected sample later in life.

4. Discussion

This is the first study since the implementation of the ‘Renewal’ to report on cervical screening awareness, attitudes, perceptions and current screening behaviours among Indigenous women from metropolitan, regional and remote NSW.

The study provides findings about the awareness, perceptions, motivators and barriers, and resulting behaviours, in relation to cervical screening among Indigenous women in NSW. Understanding these enables insights into interventions required to support Indigenous women to continue to regularly participate, or to increase or commence their participation, in the NCSP. The findings were consistent with the principles of the ecological model of behaviour change, which suggests that developing interventions at the individual, interpersonal, organisational, community and policy level can create a conducive environment to support behaviour change [15,16]. Adopting such a systems-based strategy which takes a holistic, multi-pronged and long-term approach is likely to maximise sustained behaviour change among Indigenous women through addressing the intrinsic, situational and structural barriers identified in this study.

An audience segmentation was developed for the study, with four different target audience segments identified based on attitudes and behaviours to cervical screening. These different segments show that Indigenous women are not homogeneous in their attitudes and behaviours to the topic. Therefore, to maximise effectiveness, any interventions aimed at increasing the uptake of Cervical Screening Tests among this audience should reflect these differences, with consideration given to the specific enablers and barriers faced by each audience segment. As per reports from other studies such an approach can have a positive impact on screening expectation and experiences by addressing gaps and needs in services, knowledge, attitudes, social norms and behaviours of the individual as well as their key influencers of family, friends, community and health care professionals [4,8,10,11].

The findings suggest that interventions aimed at the ‘Advocates for Prevention’ segment could encourage the women to continue their positive behaviours, and to role-model and advocate for screening in their community to build positive community sentiment and shift social norms. Interventions aimed at the ‘Compliant and concerned’ segment could aim to positively influence this segment through targeted communications, to increase their awareness and understanding of cervical cancer and prevention, address myths and misconceptions and enhance positive sentiment towards cervical screening. Interventions aimed at the ‘Willing and impeded’ segment could focus on reducing the structural and situational barriers that impede the women's access to screening, such as the provision of (or increased capacity of existing) outreach services. Finally, for the ‘Paralysed by fear and shame’ segment, while these women are likely to be the hardest to reach, interventions that promote positive emotions and attitudes may influence them as a result of a shift in community norms, whilst further interventions would most likely be required to address the structural or situational barriers that hinder the women's access to and participation in cervical screening.

The research identified significant knowledge gaps among most participants about the topic, including limited awareness and understanding about cervical cancer and its prevention and the ‘Renewal’ changes. A lack of proactive information seeking on the topic was also evidenced. In addition, negative emotions, attitudes and community norms were found to be contributing to the taboo and stigmatised nature and perceptions of the topic, which in turn limited positive screening practices, advocacy and role modelling of desired attitudes and behaviours.

The shifting of social norms, community sentiment and discourse among Indigenous audiences has been effectively achieved through social marketing campaigns focused on other health outcomes, such as reducing tobacco smoking [17], [18], [19]. Given these successes, and the findings from this study, it is suggested that a social marketing campaign could be beneficial in increasing awareness, encouraging a change of attitudes and shifting social norms, with the aim of increasing uptake of cervical screening among Indigenous women.

There is emerging evidence that social marketing campaigns that use a tone that promotes positive attitudes and emotions towards screening or other health sustaining behaviour and avoids enhancing negative attitudes or emotions are important in achieving desired outcomes [20], [21], [22], [23]. The findings from this study support the need for a positive approach to any communications so as to minimise the strong negative emotions already experienced, particularly by the ‘Paralysed by fear and shame’ audience segment.

This study highlights the importance of drawing upon the cultural strengths of Indigenous women and their communities to maximise relevance, meaning and authenticity of any interventions targeted at this audience. Given the collective nature and culture of Indigenous communities, engaging with Indigenous women at an emotional level and appealing to their strong sense of family and connections could be an effective approach for motivating action [24], [25], [26]. This strength could also be leveraged by appealing to partners of women in the target group to encourage and support their significant others to screen. The strong role, sense of respect and existing influence held by Elders, respected community role models and community leaders is also a strength that can be utilised in targeted interventions. Such influence could be used to champion and advocate for cervical screening among Indigenous women in their communities [18].

The study findings agree with structural barriers identified in previous studies for women attending screening consultations which include a lack of transport, lack of childcare facilities and time constraints [14,27,28]. In other instances, it has been found that the introduction of policies or programs which assisted women to access and attend screening appointments have had a positive impact on screening rates among Indigenous women [29,30]. Cervical screening programs could consider introducing or enhancing outreach services such as ‘pop-up clinics’/mobile screening in rural and remote locations, where choice and availability of suitable screening services is currently limited [31,32].

This study also supports the need for opportunistic screening at health care appointments, provision of understandable and clear explanations of the screening process, ensuring privacy in the set-up of the room and providing female only spaces and services where practical. In addition, sending multiple appointment reminders through a range of channels that could include text messages and telephone calls was found to be important to encourage women to screen.

The study found healthcare professionals have an important role in supporting cervical screening behaviours for all audience segments and could support and increase the credibility and relevance of a social marketing campaign by having access to fact sheets and brochures suitable for Indigenous women. In addition, due to their role in conducting screening, health care professionals could directly influence some of the situational barriers associated with negative perceptions and experiences of cervical screening. In particular, trauma informed practice was also found to be an area where enhanced understanding could lead to more positive screening experiences for Indigenous women [33]. Evidence shows that having an educational component on cultural competency for health care professionals has worked and could further support cervical screening behaviour change [34,35].

In relation to self-collection, the study found that most of the under-screened or never screened participants were reluctant to consider this option. This was due to their concerns of not administering the procedure correctly, having to conduct the self-collection at a health care clinic and having to re-screen if HPV was detected. These findings differ from several other studies conducted in developed and developing countries in which self-collection was found to be effective in increasing participation in the cervical screening programs among under screened or never screened women either in the clinical setting or at home[36], [37], [38], [39], [40], [41], [42]. To explore the differences between our findings and other studies further research is required.

It is important to note that the research methodology adopted for the study had some limitations. Firstly, given the qualitative nature of the research, a pre-defined selective sampling approach was adopted, to include a specific sample composition by screening for regularity, age and location. As a result, while the research findings are indicative of the attitudes and behaviours of a range of Indigenous women in NSW, the findings cannot be statistically extrapolated to the wider community in the absence of a quantitative research design approach. Secondly, sample bias is applicable to this study. Recruiting Indigenous women to participate in face-to-face sessions or interviews who had never screened or were lapsed screeners proved particularly challenging across all research locations. For example, a few women elected not to participate as they were not comfortable discussing cervical screening or were concerned that they would be required to undertake cervical screening as a result of the research. In addition, a few were unwilling to attend the research and identify themselves within their community as being lapsed or having never screened. These challenges would suggest that the research sample is likely to be somewhat biased, as certain cohorts within the never screened or lapsed in their screening audiences were less willing to participate.

There are several methodological strengths of this study with the first being the use of Indigenous community-based staff and Indigenous community organisations for participant recruitment. Secondly, the selection of culturally safe research settings and thirdly the provision of focus group, kinship pairing or one-on-one interview participation options for the women. Fourth, the use of a time rich approach applied to the fieldwork helped the researchers gain trust and acceptance among participants and increased community participation. These flexible approaches, which created a comfortable research environment and open discussion, enabled a better understanding of community norms and discourse [43].

The outcome was the collection of rich data to inform the study. In addition, as a result of participating in the research process and learning about cervical cancer prevention in a comfortable environment, some under or never screened participants reported that they would now regularly participate in the NCSP or more vocally advocate for others to do so.

5. Conclusion

This study demonstrates the complex and heterogenous nature of attitudes, perceptions and behaviours held and undertaken by Indigenous women in relation to cervical screening, and thus the importance of a holistic, multi-pronged strategy to bring about sustained behaviour change among specific audience segments. It also highlights the intrinsic negative attitudes, perceptions and social norms that are currently shaping community discourse relating to the topic and ultimately limiting screening among Indigenous women. The need for enhancing positive sentiment and community advocacy via a social marketing campaign, supported by professional learning opportunities for healthcare professionals and a range of other policy, program and service responses are demonstrated by the study.

Author contributions

RM: Study Design, Data Interpretation, Publication of Findings, Manuscript Review. PMo: Data Collection, Data Analysis, Report Writing, Manuscript Review. LD: Data Collection, Data Analysis, Report Writing, Manuscript Review. TF: Study Design, Data Interpretation, Publication of Findings, Manuscript Review. EF: Study Design, Data Interpretation, Publication of Findings, Manuscript Review. PMa: Study Design, Data Interpretation, Publication of Findings, Manuscript Review. NS: Study Design, Data Interpretation, Publication of Findings, Manuscript Review. DK: Data Interpretation, Manuscript Review. SF: Study Design, Data Interpretation, Manuscript Review.

The funder of the study had a role in the study design, data interpretation and publication of findings but not in the data collection and data analysis. RM, PMo, LD, TF, EF, PMa, and SF had full access to all the data in the study. DK and SF are Australian Indigenous women who provided a cultural lens to study design and data interpretation. PMa had the final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication

Declaration of interests

PMo and LD are employees of ORIMA Research, and as such they and SF received fees for services paid by the Cancer Institute NSW during this study.

RM, TF, PMa, EF, NS, and DK have nothing to disclose.

Data sharing statement

The qualitative research data collected by ORIMA Research during the current study is available from the Cancer Institute NSW on reasonable request.

Editor note: The Lancet Group takes a neutral position with respect to territorial claims in published maps and institutional affiliations

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the assisting researchers from ORIMA Research, Laura Paton, Alison McLaverty, Isabella Frances and Anna Harrison as well as the team of community interviewers, who assisted with participant recruitment, data collection and analysis, and Corinne Avery, Cancer Institute NSW, for technical editing of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Copyright © 2020 The Author(s). Published by Elsevier Ltd. This is an Open Access article under the CC BY 4.0 license.

References

- 1.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare . AIHW; Canberra: 2019. Cervical screening in Australia 2019. Cancer series no. 123. Cat. no. CAN 124. https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/6a9ffb2c-0c3b-45a1-b7b5-0c259bde634c/aihw-can-124.pdf.aspx?inline=true, [accessed 28 April 2020] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Department of Health . Australian Government; 2020. National Cervical Screening Program. http://www.cancerscreening.gov.au/internet/screening/publishing.nsf/Content/national-cervical-screening-program-policies, [accessed 10 April 2020] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Medical Services Advisory Committee . Australian Government; 2014. Application No.1276-Renewal of the National Cervical Screening Program. https://www.google.com/search?q=3.%09Medical±Services±Advisory±Committee.±Application±No.1276-Renewal±of±the±National±Cervical±Screening±Program.±Australian±Government±2014.&rls=com.microsoft:en-AU&ie=UTF-8&oe=UTF-8&startIndex=&startPage=1&gws_rd=ssl#spf=1600757131342 [accessed 22 September 2020] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Whop L, Garvey G, Baade P. The first comprehensive report on Indigenous Australian women's inequalities in cervical screening: A retrospective registry cohort study in Queensland, Australia. Cancer. 2016;122:1560–1569. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies. Indigenous Australians: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples 2018. https://aiatsis.gov.au/explore/articles/indigenous-australians-aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-people [accessed 14 April 2020]

- 6.Australian Bureau of Statistics. 3238.0.55.001 - Estimates of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians, June 2016. https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/3238.0.55.001 [accessed 14 April 2020]

- 7.Victorian Cervical Cytology Registry . VCCR; Melbourne: 2012. VCCR Statistical Report. https://www.vccr.org/site/VCCR/filesystem/documents/dataandresearch/StatisticalReports/Statistical_Report_2012.pdf [accessed 6 March 2020] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brotherton J, Winch K, Chappell G. HPV vaccination coverage and course completion rates for Indigenous Australian Adolescents. Medical Journal of Australia. 2019;211(1):31–36. doi: 10.5694/mja2.50221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare . AIHW; Canberra: 2019. National Cervical Screening Program monitoring report 2019. Cancer series no. 125. Cat. no.132. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/cancer-screening/national-cervical-screening-monitoring-2019/contents/summary [accessed 10 April 2020] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Whop L, Cunningham J, Gavey G, Condon R. Towards global elimination of cervical cancer in all groups of women. The Lancet. 2019:238. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30237-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Whop L, Cunningham J, Condon J. How well is the National Cervical Screening Program performing for Indigenous Australian women? Why we don't really know, and what we can and should do about it. European Journal of Cancer Care. 2014;23(6):716–720. doi: 10.1111/ecc.12244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coory M, Fagan P, Muller J, Dunn N. Participation in cervical cancer screening by women in rural and remote Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities in Queensland. Medical Journal of Australia. 2002;177:544–547. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2002.tb04949.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Binns P, Condon J. Participation in cervical screening by Indigenous women in the Northern Territory: a longitudinal study. Medical Journal of Australia. 2006;185:490–494. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2006.tb00663.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reath J, Carey M. Breast and cervical cancer in Indigenous women; overcoming barriers to early detection. Australian Family Physician. 2008;37(3) 178-18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sallis J, Owen N, Fisher E. Ecological Models of Health Behavior. Health Behaviour and Health Education, Theory, Research, Practice. Fourth Edition USA 2008 https://www.med.upenn.edu/hbhe4/part5-ch20.shtml [accessed 19 August 2020]

- 16.Glanz K. Fifth Edition. Office of Behavioural and Social Science Research; USA: 2015. Social and Behavioural Theories. http://www.esourceresearch.org/Default.aspx?TabId=736 [accessed 19 August 2020] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Campbell M, Finlay S, Lucas K, Neal N, Williams R. Kick the habit: a social marketing campaign by Aboriginal communities in NSW. Australian Journal of Primary Health. 2014;20:327–333. doi: 10.1071/PY14037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mitchelle E, Bandara P, Smith V. Tackling Indigenous Smoking Program. Final evaluation report. CIRCA. 2018 https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/tackling-indigenous-smoking-program-final-evaluation-report.pdf [accessed 19 August 2020] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kubacki K, Szablewska N. Social marketing targeting Indigenous peoples: a systematic review. Health Promotion International. 2019;34:133–143. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dax060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lotfi-Jam K, O'Reilly C, Feng C, Wakefield M, Durkin S, Broun K. Increasing bowel cancer screening participation: integrating population-wide, primary care and more targeted approached. Public Health Research and Practice. 2019;29(2) doi: 10.17061/phrp2921916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nicholson A, Borland R, Sarin J, Wallace S, van der Sterven A, Stevens M, Thomas D. Recall of anti-tobacco advertising and information, warning labels and news stories in a national sample of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander smokers. Medical Journal of Australia. 2015;202(10) doi: 10.5694/mja14.01628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Madill J, Wallace L, Goneau-Lessard K, Stuart MacDonald R, Dion C. Best practices in social marketing among Aboriginal people. Journal of Social Marketing. 2014;4(2):155–175. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Korf J. Creative Spirits; 2020. Aboriginal Use of Social Media. https://www.creativespirits.info/aboriginalculture/media/aboriginal-use-of-social-media%20/ [accessed 19 August 2020] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brough M, Bond C, Hunt J. Strong in the City: Towards a strength-based approach in Indigenous health promotion. Health Promotion Journal of Australia. 2004;15(3):2015–2220. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bond C, Brough M., Bond C, Brough M. In: The Meaning of Culture within Public Health Practice - Implications for theStudy of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health. Baum F, Bentley M, Anderson I, editors. Cooperative Research Centre for Aboriginal Health; Australia: 2007. Beyond Bandaids: Exploring the Underlying Social Determinants of Aboriginal Health; pp. 229–238. https://eprints.qut.edu.au/13118/1/13118.pdf [accessed 17 September 2020] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bond C. A Culture of ill health: public health or Aboriginality? Medical Journal of Australia. 2005;83(1):39–41. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2005.tb06891.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maar M, Burchell A, Little J, Ogilvie G, Severini A, Yan J, Zehbe I. A qualitative study of provider perspectives of structural barriers to cervical cancer screening among first nations women. Women's Health Issues. 2013;23-5:e319–e325. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2013.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cunningham J, Rumbold A, Zhang X, Condon R. Incidence, aetiology and outcomes of cancer in Indigenous peoples in Australia. The Lancet Oncology. 2008;9:585–595. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70150-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Diaz A, Vo B, Baade P. Service level factors associated with cervical screening in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Primary Health Care Centres in Australia. International Journal Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019;16(19):3630. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16193630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fredericks B, Longbottom M, McPhail-Bell K, Worner F., in collaboration with the Board of Waminda . Rockhampton; CQUniversity, Australia: 2016. Dead or Deadly Report. Waminda Aboriginal Women's Health Service. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/310161244_Dead_or_Deadly_report_Waminda_Aboriginal_Women%27s_Health_Service [accessed 25 August 2020] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pilkington L, Haigh M, Durey A, Katzenellenbogen J, Thompson S. Perspectives of Aboriginal women on participation in mammographic screening: a step towards improving services. BMC Public Health. 2017;17:697. doi: 10.1186/s12889-017-4701-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhu C. Public Health Innovation and Decision Support Alberta Health Services; 2012. Cancer screening in Aboriginal communities: A promising practices review. https://www.albertahealthservices.ca/poph/hi-poph-aboriginal-health-review-2012.pdf [accessed 25 August 2020] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brooks M, Barclay L. Trauma-informed care in general practice. Findings from a women's health centre evaluation. The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. 2018;47(8):370–375. doi: 10.31128/AJGP-11-17-4406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Durey A. Reducing racism in Aboriginal health care in Australia: where does cultural education fit? Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health. 2010;34(s1):s87–s92. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-6405.2010.00560.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Herring S, Spangaro J, Lauw M, McNamara L. The intersection of trauma, racism and cultural competence in effective work with Aboriginal people: waiting for trust. Australian Social Work. 2012;(1):104–117. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Arrossi S, Thouyaret L, Herrero R. Effect of self-collection of HPV DNA offered by community health workers at home visits on uptake of screening for cervical cancer (the EMA study): a population based cluster randomised trial. The Lancet Global Health. 2015;3:85–94. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70354-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smith M, Lew J, Simms K, Canfell K. Impact of HPV sample self-collection for underscreened women in the renewed cervical screening program. Medical Journal of Australia. 2016;204(5):e194. doi: 10.5694/mja15.00912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Spees L, Des Marais A, Wheeler S, Hudgens M, Doughty S, Brewer N, Smith J. Impact of human papillomavirus (HPV) self-collection on subsequent cervical cancer screening completion among underscreened US women: MybodyMyTest-3 protocol for a randomised controlled trial. BMC. 2019;20:788. doi: 10.1186/s13063-019-3959-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lorenzi N, Termini L, Filho A. Age-related acceptability of vaginal self-sampling in cervical cancer screening at two university hospitals: a pilot cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2019:963. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-7292-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sultana F, English D, Simpson J. Home-based HPV self-sampling improves participation by never screened and under screened women: Results from a large randomized trial (iPap) in Australia. International Journal of Cancer. 2016;139:281–290. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dutton T, Marjoram J, Burgess S. Uptake and acceptability of human papillomavirus self-sampling in rural and remote aboriginal communities: evaluation of a nurse-led community engagement model. BMC Health Services Research. 2020;20:398. doi: 10.1186/s12913-020-05214-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pedersen H, Smith L, Sarai Racey C, Cook D, Krajden M, van Niekerk D, Ogilvie G. Implementation considerations using HPV self-collection to reach women under-screened for cervical cancer in high-income settings. Current Oncology. 2018;25(1) doi: 10.3747/co.25.3827. https://www.current-oncology.com/index.php/oncology/article/view/3827/2647 [accessed 19 April 2020] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Martagh L. Implementing a critically Quasi-Ethnographic approach. The Qualitative Report. 2007;12(2):193–215. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ800178.pdf [accessed 19 April 2020] [Google Scholar]