Abstract

The Drosophila RNA binding protein RBP9 and its Drosophila and human homologs, ELAV and the Hu family of proteins, respectively, are highly expressed in the nuclei of neuronal cells. However, biochemical studies suggest that the Hu proteins function in the regulation of mRNA stability, which occurs in the cytoplasm. In this paper, we show that RBP9 is expressed not only in the nuclei of neuronal cells but also in the cytoplasm of cystocytes during oogenesis. Despite the predominant expression of RBP9 in nerve cells, mutational analysis revealed a female sterility phenotype rather than neuronal defects for Rbp9 mutants. The female sterility phenotype of the Rbp9 mutants resulted from defects in oogenesis; the lack of Rbp9 activity caused the germarium region of the mutants to be filled with undifferentiated cystocytes. RBP9 appears to stimulate cystocyte differentiation by regulating the expression of bag-of-marbles (bam) mRNA, which encodes a developmental regulator of germ cells. RBP9 protein bound specifically to bam mRNA in vitro, which is required for cystocyte proliferation, and the number of cells that expressed BAM protein was increased 5- to 10-fold in the germarium regions of Rbp9 mutants. These results suggest that RBP9 protein binds to bam mRNA to down regulate BAM protein expression, which is essential for the initiation of cystocyte differentiation into functional egg chambers. In hypomorphic Rbp9 mutants, cystocytes differentiated into egg chambers; however, oocyte determination and positioning were perturbed. Therefore, the concentrated localization of RBP9 protein in the oocyte of the early egg chambers may be required for proper oocyte determination or positioning.

RBP9 is a Drosophila RNA binding protein that shares a high level of sequence similarity with Drosophila ELAV (41) and human Hu proteins (HuC, HuD, Hel-N1, and HuR) (26, 29, 48). Proteins in this family are known to be expressed in the nuclei of neuronal cells right after the completion of mitotic division. RBP9 is expressed predominantly in the nuclei of cells of the central nervous system (CNS), after the CNS metamorphosis that occurs during the pupal period (19). The related human Hu proteins are also expressed primarily in neurons and are localized preferentially in the nuclei (8). Hu proteins are absent in neuroblasts but appear in subsequent early-lineage neurons and maturing neuronal cells. Thus, it has been suggested that proteins in this family are required for neuronal maturation.

A role for Rbp9 in neurogenesis is further suggested by the fact that ELAV is expressed specifically in the nuclei of all neurons (41), and loss-of-function alleles of elav are embryonic lethal, causing abnormal CNS development (40). Recently, elav was suggested to regulate neuron-specific splicing of neuroglian pre-mRNA (24), which is consistent with the presence of RNA binding motifs in the ELAV protein and its nuclear localization pattern.

However, in vitro studies suggest mRNA stability rather than pre-mRNA splicing as a functional target of the Hu proteins. For example, Hu proteins were shown to bind to stretches of U residues (the AU-rich element), and this interaction increases the stability of the bound reporter mRNAs in a cell culture system (5, 9, 21, 26, 28, 32, 37). Given that Hu protein is localized mainly in the nucleus, the cytoplasmic function of mRNA stabilization appears to be accomplished by the shuttling of nuclear Hu proteins to the cytoplasm (9). Because Hu protein binding sequences are often found in mRNAs that encode cell growth regulators, it has been suggested that the Hu proteins control cell proliferation by regulating the stability of mRNAs that encode cell proliferation and/or differentiation signal proteins (3, 4, 5, 15, 21, 26, 32). For example, the in vitro binding of Hel-N1 protein to the 3′ untranslated region (UTR) of Id mRNA, which encodes a transcriptional repressor abundant in undifferentiated neuronal precursor cells, suggests the involvement of Hel-N1 in the regulation of nerve cell development (21). Recently, we found that RBP9 down regulates the expression of extramacrochaetae (emc), a Drosophila homolog of Id, possibly through the interaction of RBP9 protein with emc mRNA (36). These results indicate that the RBP9 family of proteins binds to mRNAs and functions in the regulation of cell growth and differentiation.

In addition to the two putative functions of the Hu protein gene family discussed above, the expression of certain Hu proteins in nonneuronal tissues indicates the existence of additional physiological functions. In vertebrates, four closely related Hu homologs are expressed in a distinct developmental pattern. For example, in adult frogs, elrC and elrD are expressed exclusively in nerve cells during specific developmental stages, whereas elrA is expressed in all tissues throughout development. In particular, elrB is expressed in testis and ovaries, in addition to its stage-specific expression in the brain (13). Therefore, each of the related Hu homologs appears to participate in the regulation of distinct developmental processes.

In this paper, we present the results of experiments designed to decipher the function(s) of RBP9. We show that RBP9 protein is expressed in the cytoplasm of ovaries, as well as in the nuclei of neuronal cells. Analysis of Rbp9 mutants revealed that although mutant cystocytes divide continuously, their differentiation is arrested. In addition, we show that RBP9 protein binds specifically to the U-rich region of bag-of-marbles (bam) RNA in vitro and that BAM protein expression is expanded in Rbp9 mutant ovaries. The specific interaction between RBP9 protein and bam mRNA in vitro suggests that RBP9 regulates either the stability or the translational competence of bam mRNA, which in turn affects cystocyte differentiation of ovaries.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Determination of the P-element insertion site at the 23C region.

The DNA sequences flanking the P elements at the 23C region of mutant Drosophila P944, P1046, l(2)K00632, l(2)K05431, l(2)K05432, l(2)K07920, l(2)K12901, l(2)K16124, and l(2)K08224 strains (49) were amplified by inverse PCR (7). Each amplified fragment from P-element insertion lines was cloned, labeled with 32P, and hybridized to dot-blotted DNA from the following cosmid contigs: 166H10, 16A8, 82F12, 78F3, 193E7, 122A10, 25A6, and 132H9 (44). To determine the exact location of a P element within the cosmid clones that gave a positive signal in the dot blot hybridization analysis, the cosmid DNA was digested, blotted on a nitrocellulose membrane, and probed with a P-element flanking sequence. The exact location of the P-element insertion site was confirmed by directly sequencing the amplified P-element flanking sequences as described by Rao (38).

P-element-mediated mutagenesis.

The l(2)K12901 strain has one P element that contains a mini-white gene (P[w+]) at the 23C region. To mobilize the P element of l(2)K12901, we crossed l(2)K12901/CyO flies with w/w; TMS, Sb P[ry+ Δ2-3]/Dr flies (39), which harbor a helper P element (Δ2-3) on the third chromosome, and isolated male progeny that had both P elements. After the helper P element provided the necessary transposase to mobilize P[w+] to new insertion sites, we crossed four of these males with four w1118 homozygous females in each vial (total number of vials = 2,500) to eliminate the P[ry+ Δ2-3] element. Progeny with eye colors different from those of the parents were screened for mobilized P elements. No more than one fly with changed eye color was selected from each vial and crossed with w1118 virgin females to establish lines that carried P elements that had moved to new insertion sites. We established 900 lines from this screening, and the location of each P-element insertion site was determined by PCR. A PIR primer (7) complementary to the inverted repeats of the P element was used with eight 20-nucleotide Rbp9-specific primers for the PCR. These eight Rbp9-specific primers are referred to as 199, 2109, 3219, 5125, 6710, 8370, 9909, and 11325. The numbers indicate the nucleotide position of the 5′ end of each primer in the Rbp9 genomic sequence (GenBank accession no. S55886), and these eight primers corresponded to nearly every 1- to 2-kb region throughout the entire gene.

Genomic DNA was prepared from each of the 900 P-element-mobilized lines in groups of 10, and 1/20 of the DNA was used as a substrate for PCR amplification with the PIR primer and a mixture of the eight Rbp9-specific primers. When a specific PCR product from a portion of Rbp9 was identified, genomic DNA was again prepared from each individual line, and another round of PCR was performed. For the lines identified as having P elements inserted at new locations within the Rbp9 gene, the genomic locations of the P elements were determined by a series of PCRs with PIR and individual Rbp9-specific primers. When necessary, the PCR fragments were sequenced to determine the exact location of the P element insertion according to the method described by Rao (38). Because most of the P-element insertions obtained from the first mutagenesis were concentrated in the promoter region of Rbp9, with no P elements inserted within the coding region, we performed a second round of mutagenesis (screening an additional 2,264 lines with mobilized P elements) using Rbp9P[1374], a line from the first mutagenesis that has a P element located near the coding region of Rbp9. We isolated three insertions that were localized to the coding region of the Rbp9 gene: Rbp9P[2690], Rbp9P[2775] and Rbp9P[2398].

As P elements in the Rbp9 coding region could potentially be spliced out during the transcription process to produce some intact Rbp9 messages, we remobilized the P element from the Rbp9P[2775] and Rbp9P[2398] strains to isolate chromosomes with deletions within Rbp9 gene produced by imprecise excision of the P elements. We obtained 56 and 34 P-element-excised lines from the Rbp9P[2775] and Rbp9P[2398] strains, respectively. Among these, complete reversion of the Rbp9 mutant phenotype occurred in only five and seven cases of the excision lines generated from the Rbp9P[2775] and Rbp9P[2398] strains, respectively. For an as yet unknown reason, imprecise excisions occurred more frequently at the Rbp9 locus than at most other loci. We did not analyze all of the excision lines in detail. Rather we carefully characterized one of the P-element excision lines, the Rbp9Δ1 allele, which was generated by imprecise P-element excision from Rbp9P[2775].

Genomic DNAs prepared from the wild-type (w1118), Rbp9P[2775], and Rbp9Δ1 alleles were digested with HindIII and blotted on a nitrocellulose membrane for Southern hybridization. The blotted nitrocellulose membrane was hybridized either with a 32P-labeled probe prepared from the genomic DNA fragment encompassing the entire Rbp9 locus (the region from 3.4 kb upstream of the first transcriptional initiation site to nucleotide position 11347) or with probes prepared from the small HindIII-digested genomic DNA fragments corresponding to nucleotide positions 1854 to 3815, 3815 to 6250, and 6250 to 9823. From this analysis, we found that the Rbp9Δ1 allele has a chromosomal deletion approximately from nucleotides 3400 to 7132, which removed the P3 promoter and a 0.45-kb segment of the coding region that included the translational initiation codon.

For germ line transformation, the 17.1-kb Rbp9 genomic fragment, which harbors the region from 5.4 kb upstream of the first transcriptional initiation site (P1) to 1.1 kb downstream of the poly(A) signal, was inserted into pCaSpeR to make pCaSpeR-Rbp9.

Immunoblot analysis.

Five adult flies or the dissected ovaries and the carcass from an equivalent number of flies were homogenized with a disposable microdouncer in 30 μl of protein sample loading buffer in a microcentrifuge tube. The fly debris was removed by centrifugation (15,000 × g, 5 min). Protein extracts (∼4 μg of protein) were subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane for Western analysis (42).

Immunostaining of ovaries.

Ovaries (10 to 20 pairs) from healthy young flies were dissected in 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and fixed for 20 min in 4% paraformaldehyde in 1× PBS. The fixed ovaries were washed several times over a 2-h period with PBT (0.1% Tween 20 in 1× PBS). Anti-RBP9 antibody (Ab) was raised against the C-terminal half of the protein and affinity-purified as described elsewhere (19). Abs were diluted (RBP9 Ab, 1:50; cytoplasmic BAM Ab [30], 1:200; and HTS [hu-li tai shao protein] Ab [51], 1:5) in TNBTT (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% bovine serum albumin, 0.1% Triton X-100, 0.05% Thimerosal [Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.]), and the ovaries were incubated in an Ab-containing solution at 4°C overnight. After being washed once with TNBTT, ovaries were incubated with TNBTT containing 2% goat serum for 30 min, washed with TNBTT for 2 h, and then incubated with fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated secondary immunoglobulin G (Sigma) in TNBTT at a 1:100 dilution for 2 h. After washing with PBS, ovaries were mounted with Vectashield (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, Calif.) mounting medium. The RBP9 Ab was used after incubation with ELAV-agarose (0.1 ml) for 4 h at 4°C to remove any ELAV-cross-reacting material.

UV cross-linking assay.

Protein-DNA UV cross-linking assays were performed as described elsewhere (20). Recombinant RBP9 (rRBP9; 60 ng) (36) was preincubated for 10 min with 10 μg of yeast tRNA in a 10-μl reaction mixture that contained 1 μl of 10× reaction buffer A (32 mM MgCl2, 20 mM ATP, 1 mg of bovine serum albumin per ml, 60 mM HEPES-KOH [pH 7.9]). The 3′ UTR of bam mRNA (450 bp between the termination codon and the polyadenylation signal) was prepared by PCR amplification of wild-type Drosophila cDNA with primers bam5 (5′-TTT CTA GAA CTA ATG CTG TGC ACA TCG AT-3′) and bam3 (5′-TTT CTA GAT GAC TTT CAA AAT ACA AAT G-3′). The amplified fragment, which was digested with XbaI, was cloned into the XbaI site of pBluescript KS+II (Stratagene) to make pKSBam3UTR, and the insert was sequenced to confirm the absence of a mutation. An RNA probe encoding the bam 3′ UTR (containing three putative RBP9 binding sites [RBP9BS] at 274, 371, and 388 bp from the termination codon) was transcribed by T7 RNA polymerase in the presence of [32P]UTP from the pKSBam3UTR template that has been linearized with BamHI. The 32P-labeled RNA probe (100 fmol) was added to the reaction mixture, and the sample was incubated for an additional 10 min at room temperature. The sample was placed on ice and irradiated with UV light (105 ergs/mm2) with use of a Stratagene (La Jolla, Calif.) UV cross-linker. The RNA was digested with RNase A (30 μg) for 15 min at 37°C and mixed with protein gel loading buffer. Samples were boiled for 90 s and subjected to SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. For UV cross-linking competition assays, a 20- to 400-fold excess of competitor RNA oligonucleotides was added to the reaction mixtures together with the 32P-labeled RNA probes. The competitor RNA oligonucleotide RBP9BS (sense strand) was designed on the basis of the consensus binding sequences of rRBP9 (UUUXUUUU) (36) and Hel-N1 (RWUUUAUUUWR) (10), which were identified with the use of SELEX (25). The RNA oligonucleotides used for these assay were RBP9BS sense (5′ UUG AUU UAU UUU GAU UUU AUU UAG UU 3′) and RBP9BS antisense (5′ GAA AAA AAA AGA AAA AAA AAA GAA 3′).

RESULTS

Expression of RBP9 in the cytoplasm of early developing cystocytes during oogenesis.

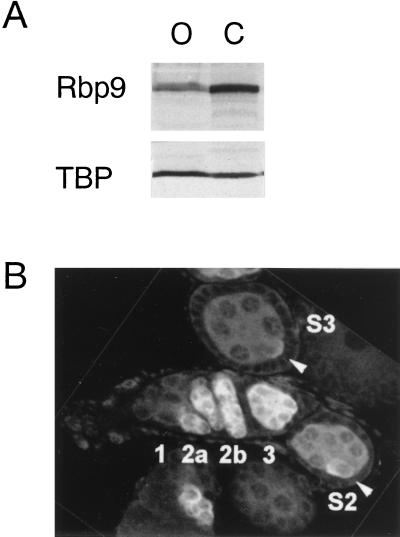

To examine whether the Drosophila Hu homolog RBP9 is expressed in germ line cells, we dissected ovaries from wild-type flies and examined the expression of RBP9 in both the ovaries and the carcass. Western analysis showed that RBP9 was expressed in ovaries as well as in the carcass where the CNS is retained (Fig. 1A).

FIG. 1.

Expression and localization of RBP9 in the ovaries. (A) Expression of RBP9 protein in ovaries. Ovaries were dissected from wild-type flies, and whole-cell extracts were prepared from the dissected ovaries (O) and carcass (C). The whole-cell extracts were resolved in an SDS-polyacrylamide (10%) gel and immunoblotted with affinity-purified anti-RBP9 antibody. As a protein loading control, the same blot was probed with an antibody to yeast TATA binding protein (TBP); the cross-reacting protein bands are shown. (B) Cytoplasmic localization of RBP9 protein in wild-type ovaries. Ovaries were stained with anti-RBP9 antibodies and analyzed by confocal microscopy. The ovariole in the middle shows, from left to right, the germarium regions (1, 2a, 2b, and 3) and stage 2 egg chamber (S2). The oocytes at the posterior of each egg chamber are marked with arrows. In the stage 3 egg chamber (S3), RBP9 staining is detected only in the oocyte.

We next sought to determine the developmental time and location of RBP9 expression in wild-type fly ovaries by staining them with anti-RBP9 Ab. RBP9 was first detected in the cytoplasm of the 16 cystocytes of germarium region 2a, which had just completed four mitotic divisions (30) (Fig. 1B). As the 16-cell cluster of cystocytes moved to germarium region 3, where follicle cells completely surround the cystocytes to form an egg chamber, RBP9 was still present in all 16 cells (Fig. 1B). The concentration of RBP9 began to diminish as egg chambers left the germarium and developed into stage 2 egg chambers (stages are as described in reference 22). However, the highest concentration of RBP9 still remained in the cytoplasm of the most posterior cell, which will become an oocyte. In stage 3 egg chambers, RBP9 was nearly gone from the cystocyte and present in only small amounts in the oocyte. The cytoplasmic localization of RBP9 is intriguing, because no other Hu family protein has been shown to be expressed predominantly in the cytoplasm in normal tissue.

Isolation of Rbp9 mutant alleles by P-element-induced mutagenesis.

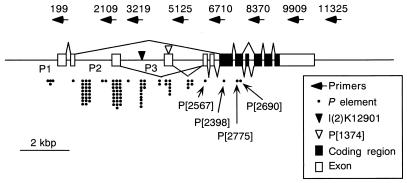

The distinct localization pattern of RBP9 in the cytoplasm of ovaries, in addition to the nuclei of cells of the CNS, provided a unique opportunity to examine both the cytoplasmic and nuclear functions of Rbp9 during development. These observations prompted us to isolate a collection of Rbp9 mutants. Because our initial attempt to isolate Rbp9 mutants by using ethyl methanesulfonate treatment was not successful (18), we used a local P-element mutagenesis protocol (see Materials and Methods). As a first step, we screened existing fly strains that had P elements inserted at the 23C region for one that contained a P element close to the Rbp9 locus. Southern blot analyses performed on Rbp9 genomic clones with the P-element flanking sequences as probes revealed that the l(2)K12901 strain contains a P element inserted within the Rbp9 gene. Sequence analysis of the P-element flanking regions confirmed its location at the Rbp9 intron upstream of the third promoter (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Locations of P-element insertions in Rbp9 mutant alleles isolated by P-element-induced mutagenesis. P1, P2, and P3 indicate the three alternative Rbp9 promoters; the splicing patterns of alternatively used exons are shown with lines. The P-element insertion sites of I(2)K12901 and Rbp9P[1374] flies used to initiate P-element local mutagenesis, the ultimate locations of the P elements in the 87 lines isolated, the four Rbp9 mutant alleles (P[2567], P[2398], P[2690], and P[2775]) described in this paper are indicated, and the locations of primers used to map the insertion sites of P elements are indicated. The number above each arrow at the top indicates the 5′ end of the primer corresponding to the nucleotide number of Rbp9 as described by Kim and Baker (19).

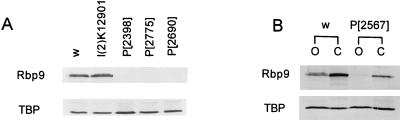

Although the l(2)K12901 strain was originally isolated as a P-element-induced lethal line, homozygotes were later shown to be weak but viable, with wings that remained folded after eclosion. However, the mutation that caused the folded wing phenotype segregated away from the P-element insertion when l(2)K12901 strain was back-crossed to wild-type flies. Immunoblot analysis with anti-RBP9 antibody showed that l(2)K12901 strain expressed wild-type levels of RBP9 protein (Fig. 3A). Therefore, the P-element insertion at the Rbp9 intron had no effect on Rbp9 expression.

FIG. 3.

Immunoblot analysis of Rbp9 alleles. (A) Crude fly extracts (4 μg) were analyzed by Western blotting with anti-RBP9 Ab. The fly strains analyzed are indicated above the lanes (w1118 [w] was used as wild type). (B) The expression of RBP9 protein in ovaries (O) and carcass (C) is shown for wild-type and Rbp9P[2567] female flies. As a loading control, the same blot was probed with an Ab to yeast TATA binding protein (TBP); the cross-reacting protein band in each lane is shown.

To generate an RBP9 protein null mutant, we mobilized the P element of l(2)K12901 strain to locations within the Rbp9 coding region. We screened a total of 4.5 × 105 flies and isolated 3,164 lines with mobilized P elements. From these, we isolated 87 lines with P elements within the Rbp9 gene. Most of the P-element insertions occurred at several insertion hot spots near the promoters and 5′ UTR. In only three cases did P elements translocate to the Rbp9 coding sequences; we refer to these strains as Rbp9P[2690], Rbp9P[2775], and Rbp9P[2398] (Fig. 2).

Despite the extensive mutagenesis of the Rbp9 gene, all homozygotes of the P-element insertion lines described above were viable, and the level of RBP9 expression was not affected by the P-element insertions in most cases. However, no detectable amount of RBP9 protein was observed from the three Rbp9 alleles harboring P elements in the Rbp9 coding region (Rbp9P[2690], Rbp9P[2775], and Rbp9P[2398]) (Fig. 3A).

Because RBP9 protein is expressed in ovaries as well as in the CNS, we examined the remaining P-element lines for mutants that were defective in RBP9 expression in only one of these tissues. Although immunoblot analysis of whole-fly extract from Rbp9P[2567] detected RBP9 levels comparable to those of wild-type flies (data not shown), when we tested ovary and carcass separately, we detected RBP9 only in the CNS, which was represented by the carcass extract, not in the ovaries (Fig. 3B).

To determine the exact locations of the P elements in these Rbp9 alleles, we sequenced each P-element flanking region. Strain Rbp9P[1374], which was used to start the second round of P-element mutagenesis (see Materials and Methods), had a P element inserted at nucleotide position 4668 of exon 4. In addition to this P element, strains Rbp9P[2690] and Rbp9P[2398] each contained a P element at nucleotide positions 7197 and 6937, respectively. In contrast, Rbp9P[2775] contained a single P element inserted at nucleotide position 7132, without the original P element at position 4668 (Fig. 2). All of these P elements disrupted the Rbp9 coding region within the first RNA binding domain.

Female-specific sterility of Rbp9 mutants.

Although the predominant expression of RBP9 in the adult CNS suggested a putative function of RBP9 in CNS development, we could detect no obvious defect in mutant viability, CNS development, or behavior. However, each Rbp9 mutant showed some degree of defects in fertility. Rbp9P[2690] homozygotes were completely sterile, while Rbp9P[2775] and Rbp9P[2398] homozygotes showed a reduction in fertility. The numbers of progeny eclosed from Rbp9P[2690], Rbp9P[2775], and Rbp9P[2398] homozygous parents were 0, 3, and 23%, respectively, of those eclosed from wild-type parents (Table 1). When homozygous females of each of the Rbp9 mutant alleles were crossed to wild-type males, the degree of sterility observed was similar to that of each homozygote. On the contrary, none of the mutant males showed a defect in fertility when crossed to wild-type females (Table 1). Therefore, Rbp9 is required for fertility only in females.

TABLE 1.

Sterility of Rbp9 mutants

| Genotype | Fertilitya

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Homo-zygote | Rbp9 femaleb | Rbp9 maleb | /Dfc | /Df; +/P[Rbp9+]d | |

| w1118 | 100 | 100 | 100 | ND | ND |

| P[2398] | 23 | 30 | 103 | — | +++ |

| P[2567] | 28 | 43 | 104 | — | +++ |

| P[2775] | 3 | 0 | 96 | — | +++ |

| P[2690] | 0 | 0 | 100 | — | +++ |

Ten 3-day-old homozygote females and males were crossed in vials. After 2 days, flies were transferred to new vials every day for 5 days and then discarded. After 2 weeks from the last transfer, the adult flies eclosed were counted. The numbers shown indicate the percentage of mutant flies eclosed with respect to the number of flies eclosed from vials containing wild-type flies (100%). ND, not determined; —, no viable progeny observed; +++, the number of progeny was indistinguishable from that obtained with wild-type flies.

Ten Rbp9 mutant homozygote females or males were crossed with w1118 males or females, respectively.

Rbp9/Df(2L) 16x42 (11) hemizygote.

Rbp9/Df(2L) 16x42 hemizygote transformed with Rbp9 genomic DNA.

In addition, it appears that RBP9 expression in the ovaries but not in the CNS is required for fertility. The Rbp9P[2567] homozygote showed normal RBP9 expression in the CNS but not in the ovaries. The number of progeny eclosed from Rbp9P[2567] homozygote parents was only 28% of those eclosed from wild-type parents (Table 1). This result suggests that (i) the oogenesis defect observed in strains bearing the Rbp9P[2567] allele was caused solely by the loss of Rbp9 expression in ovaries and (ii) expression of Rbp9 is regulated in a tissue-specific manner.

Although all four of the Rbp9 mutants studied apparently expressed no RBP9 protein in the ovaries, they exhibited various degrees of sterility. To test whether the incomplete penetrance of the sterility phenotype in strains carrying certain Rbp9 mutant alleles resulted from residual Rbp9 activity, we placed the Rbp9 mutant alleles over the deficiency chromosome, which removes most of the 23C region including Rbp9. These hemizygote flies showed sterility with 100% penetrance. Therefore, certain of the above-cited Rbp9 mutants appear to possess a partially active Rbp9 gene.

Because residual Rbp9 activity may result from the synthesis of a low amount of intact mRNA by the splicing out of the inserted P element, we remobilized the P element to induce its imprecise excision. This generated a strain with a chromosomal deletion that included the translational initiation site and the first N-terminal 150 amino acids (Rbp9Δ1; see Materials and Methods). Homozygotes of the Rbp9Δ1 allele showed a complete female sterility phenotype (data not shown). Therefore, a small amount of Rbp9 activity must be retained in the Rbp9P[2775], Rbp9P[2567], and Rbp9P[2398] strains, whereas the Rbp9P[2690] allele is very close to null. The sterility phenotype of all the Rbp9 alleles was rescued completely by germ line transformation of a DNA fragment that encompassed the Rbp9 gene (Table 1). Therefore, the female sterility phenotype is a genuine Rbp9 null phenotype.

Defective ovary development in Rbp9 mutants.

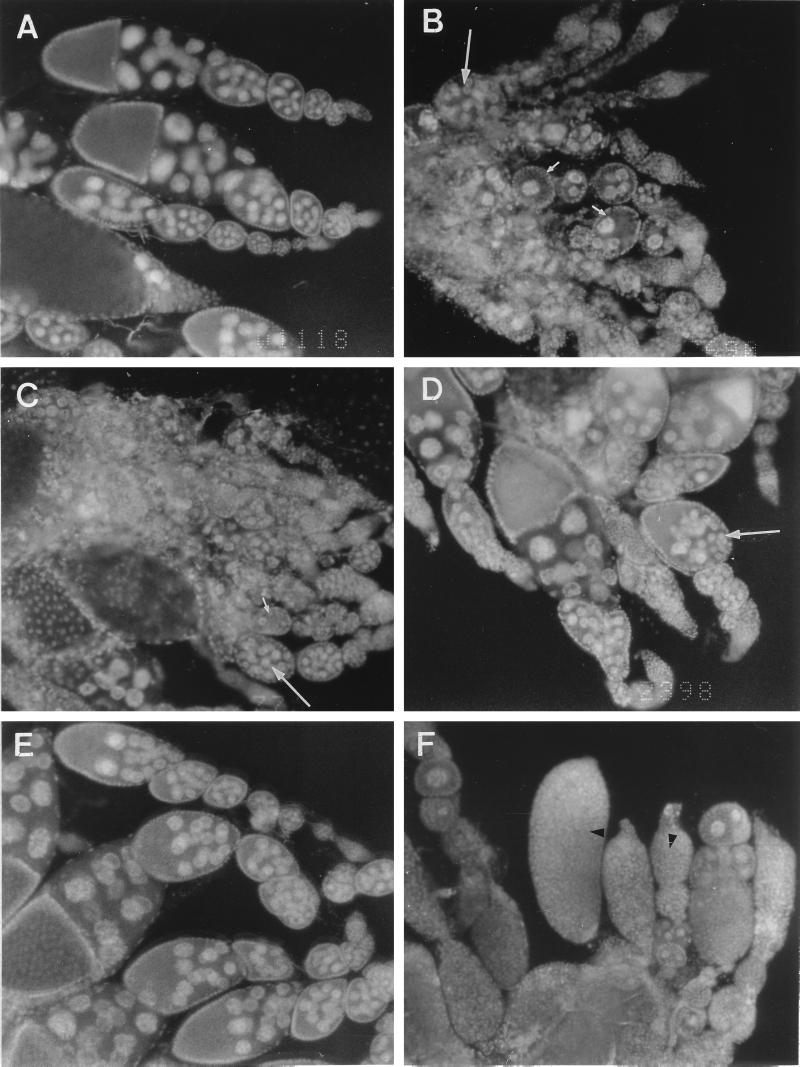

To understand how the loss of Rbp9 activity caused female sterility, we examined the phenotypes of ovaries isolated from Rbp9 mutant strains. In whole ovaries examined by nuclear (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole [DAPI]) staining (Fig. 4), ovarioles from strains bearing the Rbp9 alleles that showed the most severe sterility phenotype (Rbp9P[2690] and Rbp9Δ1) were filled with egg chambers containing abnormal number of cystocytes that never developed beyond a stage 6 egg chamber (Fig. 4A and B and data not shown). In addition, the germarium regions were enlarged as often detected in ovarian tumors (11, 23, 31, 35, 43). In a few cases the ovarioles were completely devoid of egg chambers. As the Rbp9 mutant flies aged, we observed that the underdeveloped egg chambers became filled with numerous small cells (the “tumorous bag” phenotype).

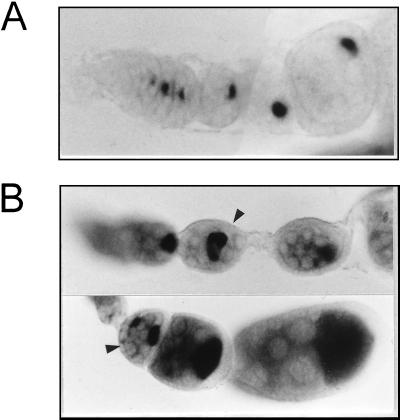

FIG. 4.

Allele-specific phenotypes of Rbp9 mutant ovaries. The anterior end of the ovaries is oriented at the right side of each panel except panel F, where the anterior end is oriented toward the top. Ovaries consist of ovarioles in which progressively more advanced stages of oogenesis are arranged linearly from anterior (right or top in panel F) to posterior (left or bottom in panel F). (A to F) DAPI staining patterns of ovaries from wild-type and mutant flies. (A) Wild-type ovaries. Each egg chamber consists of one oocyte and 15 nurse cells surrounded by follicle cells. (B to E) Ovaries from Rbp9P[2690], Rbp9P[2775], Rbp9P[2398], and Rbp9P[2567] homozygous flies, respectively. (F) Ovaries from an Rbp9P[2398]/Df hemizygous fly. Egg chambers with fewer or more than 15 nurse cells are indicated with short or long arrows, respectively. Black arrowheads represent egg chambers with tumorous cells.

The defects in oogenesis in the Rbp9P[2775] mutant were slightly less severe than those in the Rbp9P[2690] ovaries. Most of the defects observed in Rbp9P[2690] flies were present in Rbp9P[2775] flies; however, a few egg chambers in Rbp9P[2775] flies did progress to later developmental stages, producing mature egg chambers (Fig. 4C). The other two Rbp9 mutants (Rbp9P[2398] and Rbp9P[2567]) with less severe sterility had only minor defects in oogenesis (Fig. 4D and E). The overall structure of the ovaries was similar to that of wild-type flies, but egg chambers with abnormal numbers of nurse cells were often detected.

Although the various Rbp9 mutant homozygotes showed distinct oogenesis defects, all of the hemizygous flies that carried one of the Rbp9 mutations over a deficiency chromosome showed the most severe oogenesis defects. Most ovarioles from these flies were filled with several tumorous bags that contained hundreds of cells instead of 15 polyploid nurse cells and one oocyte (Fig. 4F). The severity of the defects in oogenesis in different alleles correlated with the degree of the sterility observed in those alleles.

Requirement of Rbp9 for oocyte determination and positioning.

In addition to the function of Rbp9 in the regulation of germ cell proliferation and differentiation, the specific localization of RBP9 protein in the oocyte of the early egg chambers suggests that RBP9 is also required for proper oocyte determination. Because the strong Rbp9 mutant alleles (Rbp9P[2690] and Rbp9Δ1 alleles) did not produce egg chambers developed sufficiently to allow study of the later stage-specific function of Rbp9, we examined the oocyte determination process of hypomorphic Rbp9 (Rbp9P[2398] and Rbp9P[2567]) mutants, which contain normally shaped egg chambers. In wild-type ovaries, oskar (osk) mRNA is concentrated in the oocytes located at the posterior end of each egg chambers (Fig. 5A). However, in the Rbp9P[2398] mutant ovaries, osk mRNA often accumulated in more than one cell (Fig. 5B). Even when osk mRNA did accumulate in only one cell, it often was not positioned at the most posterior end of the egg chambers. This alteration in the distribution pattern of osk mRNA demonstrated that Rbp9 function is also required for proper oocyte determination and positioning.

FIG. 5.

Pattern of osk mRNA distribution in wild-type (A) and Rbp9P[2398] (B) ovaries. The hybridization signal appears as darkly staining material. Arrowheads indicate egg chambers that either contain an osk mRNA-accumulating cell that is not located at the posterior of egg chamber or have more than one cell that accumulates osk mRNA. Progressively older egg chambers are shown from left to right.

Requirement of Rbp9 function for regulation of cystocyte differentiation.

Immunostaining of wild-type ovaries with antibodies to HTS (51), a fusome component, initially shows two stem cells with dot-shaped spectrosomes; as the cystocytes divide, fusomes with branched structures are observed. The branched fusome structure is observed most clearly when cystocytes lose the rosette conformation after the fourth round of mitotic division and take on a lens-shaped appearance in the most anterior section of germarium region 2 (Fig. 6A). This cyst development requires a number of genes, including ovarian tumors (otu), benign gonial cell neoplasm (bgcn), and bam (11, 12, 46). Analysis of the germarium regions of bgcn or bam mutants with antibodies to fusome components reveals that most of the cystocytes have dot-shaped or single-branched fusomes, whereas the cystocytes of otu mutant ovaries have branched fusomes despite the similar tumorous phenotype (27, 31, 47).

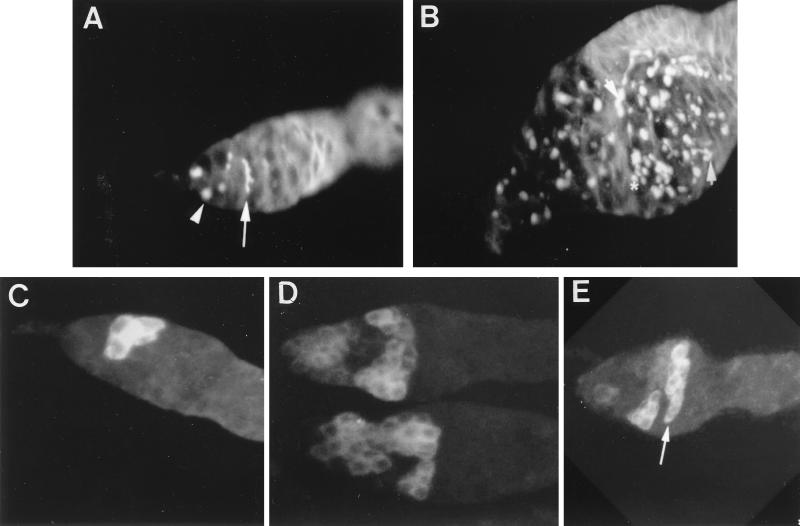

FIG. 6.

Immunostaining of the germarium with Abs to HTS (A and B) or BAM (C to E). Wild-type (A and C) and Rbp9Δ1 mutant (B, D, and E) ovaries were stained with Abs to the cytoplasmic BAM and HTS proteins. The anterior ends of the germarium are at the left of each panel. (A) At the tip of the germarium, a fusome in the stem cell appears as a spherical dot (arrowhead). As cystocytes divided, the fusome becomes elongated and finally appears as a branched structure (long arrow). (B) Most of fusomes in the Rbp9 mutant appear to be branched (short arrow) but do not have the shape of a fully branched structure. Some cystocytes contain fusomes in the shape of spherical dots without an obvious visible connection between each other (∗). (C) Cytoplasmic staining of BAM protein is clearly visible in a cluster of four cystocytes located near the anterior end of the wild-type germarium. (D) Rbp9 mutant germarium contains an increased number of cells that express BAM proteins. Several clusters of cystocytes are stained with BAM Ab. (E) BAM protein is still detectable even when the cystocytes show a lens-shaped morphology, which is usually detected in germarium region 2b (arrow).

We stained Rbp9 mutant ovaries against anti-HTS to see whether these mutants exhibit a dot-shaped or branched fusome structure. Most of the fusomes in the Rbp9 mutant germarium were branched; however, fully branched fusome structures were faintly detectable (Fig. 6B). The rest of the fusomes in the mutant appeared as spheres, but the shape of the fusome differed from that of the spectrosome of wild-type flies. Instead of well-separated, single dot-shaped fusomes, several sphere-shaped fusomes were located very close to each other without detectable connections (Fig. 6B). Some of the sphere-shaped fusomes were connected with thin linear fusomes. These results show that cystocytes in the Rbp9 mutant germarium were not able to differentiate into 16-cell clusters that can be enveloped by somatic follicle cells. Therefore, Rbp9 is required for the initiation of cystocyte differentiation.

BAM proteins are known to be expressed in mitotically active cystocytes in germarium region 1 and are not normally expressed in the germ cells of germarium region 2 (30). Therefore, we stained Rbp9Δ1 mutant ovaries with anti-BAM Ab to determine the developmental location of BAM protein expression. In wild-type ovaries, only one or two cystocytes expressing BAM protein were detected in each germarium (Fig. 6C). On the other hand, in Rbp9Δ1 mutant ovaries, the tumorous germarium region was composed of several clusters of cystocytes that were expressing BAM protein (Fig. 6D). Occasionally, cystocytes developed to a lens-shaped morphology, which is characteristic of germarium region 2b cystocytes, and BAM protein was still expressed in those cystocytes (Fig. 6E). This prolonged expression of BAM protein is never detected in wild-type cystocytes. The expression of BAM protein in multiple cystocytes of the Rbp9 mutant germarium suggests that the mutant cystocytes are arrested early in development, at a stage prior to their differentiation into an egg chamber.

Binding of RBP9 to the 3′ UTR of bam mRNA in vitro.

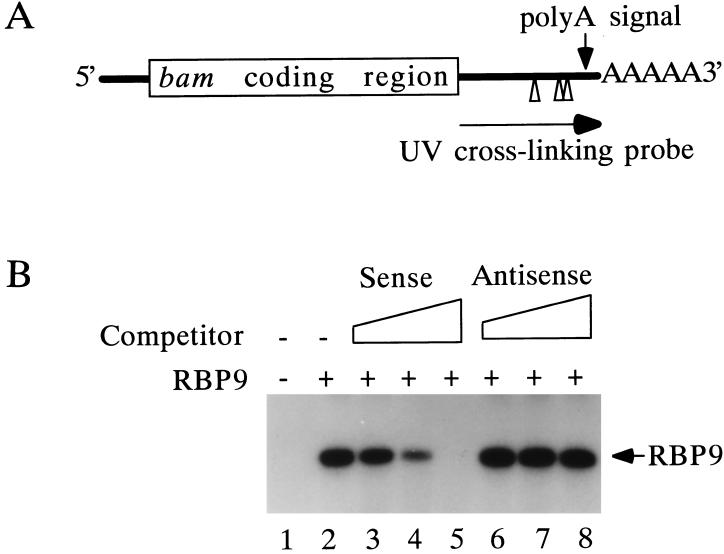

Our observation that an increased number of Rbp9 mutant cystocytes express BAM protein suggests that Rbp9 may be required for the down regulation of BAM expression. For example, RBP9 may bind to bam mRNA and regulate its stability or translatability. In vitro binding assays identified the sequence UUUAUUU as an RBP9 consensus binding site. Examination of the nucleotide sequence of bam mRNA by using the WINDOW program (Wisconsin Package; GCG Inc.) identified three UUUAUUU sequences within the 3′ UTR, located 177, 80, and 63 bp upstream of the poly(A) signal. To test whether these repeats represent authentic RBP9BS, we used a UV cross-linking assay to detect RBP9 binding to the bam mRNA 3′ UTR. As shown in Fig. 7B, the 3′ UTR of bam mRNA cross-linked efficiently to RBP9 protein (lane 2). To confirm the specificity of binding, we tested the ability of sense and antisense RNAs to compete for RBP9 binding. When added to the binding reaction, sense competitor RNA oligonucleotide that contained two repeats of the RBP9BS efficiently competed with the bam 3′ UTR probe for RBP9 binding (lanes 3 to 5). Conversely, antisense RNA that contained the complementary RBP9BS sequences did not compete efficiently for RBP9 binding, even when a 400-fold excess was added to the binding reaction (lanes 6 to 8). These results indicate that RBP9 binds specifically to the bam mRNA 3′ UTR and suggest that RBP9 may down regulate BAM expression by interacting with the AU-rich elements of bam mRNA.

FIG. 7.

Binding of RBP9 protein to the U-rich elements within the 3′ UTR of bam mRNA. (A) locations of the UUUAUUU motifs (Δ) in the 3′ UTR of bam mRNA. The second and third Rbp9 binding motifs (ΔΔ) are located 9 bp apart near the poly(A) signal. The probe used for the UV cross-linking assay is shown. The locations of the bam coding region and poly(A) tail (AAAAA) are marked. (B) UV cross-linking of RBP9 protein to bam mRNA. Recombinant RBP9 protein (60 ng) was UV cross-linked to the 3′ UTR of bam mRNA. RBP9BS sense (lanes 3 to 5) and antisense (lanes 6 to 8) RNA oligonucleotides were added as competitor RNAs to the binding reaction in 40-, 120-, and 400-fold excesses, respectively.

DISCUSSION

Because the RNA binding proteins RBP9, ELAV, and Hu were identified originally in nerve cell nuclei, researchers suggested that they function in neurospecific pre-mRNA processing (19, 29, 48). However, the results of subsequent studies on Hu proteins suggested that they play a role in the regulation of mRNA stability in the cytoplasm of developing neuronal cells (5, 9, 21, 26, 28, 32, 37). Although Hu proteins were shown recently in a tissue culture system to increase the stability of reporter mRNAs that contain Hu protein binding sequences (9), direct evidence of such a cytoplasmic function obtained under physiological conditions was lacking. In this study, we show that RBP9 is localized in the cytoplasm and regulates BAM expression in differentiating germ cells. These findings strongly support the idea that the RBP9 family proteins regulate mRNA stability and/or translational competence of mRNAs that encode cellular differentiation signal proteins.

In addition to the proposed cytoplasmic function of Rbp9, the detection of Rbp9 in a tissue outside the CNS is intriguing. Although elrA, elrB, and HuR were found in cells other than neurons, their physiological roles in these nonneuronal cells have not been established (13, 29). In this study, genetic, molecular, and morphological examination of Rbp9 mutants revealed a requirement for Rbp9 in the regulation of female germ cell differentiation. The absence of RBP9 protein in the germarium caused cystocytes to be arrested at various undifferentiated stages, and tumorous ovarioles filled with the accumulating cystocytes were formed. This defect seems to be mediated through bam, as RBP9 interacts with bam mRNA in vitro and BAM expression is expanded in the Rbp9 mutants. Moreover, the unusual expression of BAM in germarium region 2b cystocytes suggests that the expansion of BAM expression is not just a simple reflection of the increase of early stage cystocytes in the tumorous ovarioles. Rather, we suggest that down regulation of BAM expression is required for proper cystocyte differentiation and that this process is not properly regulated in the Rbp9 mutants.

It has been suggested that bam serves multiple functions in a number of the developmental stages of oogenesis. A loss of function mutation in bam causes female cysts to proliferate like stem cells (30, 31), whereas ectopic expression of bam in ovaries, including the stem cells, eliminates oogenic germ line stem cells (33). Therefore, bam appears to function in suppressing stem cell fate in stem cell daughters and to promote cystoblast differentiation (33). Analysis of encore mutants suggested additional functions for bam during the later stages of cystocyte development. BAM is expressed only in the dividing cystoblast and cystocytes and is removed from the cystocytes after four rounds of mitotic division (30). As the expansion of bam transcripts is correlated with one extra round of mitosis in the encore mutant germarium, bam may act as part of a titratable counting mechanism whose levels determine the number of mitotic divisions (14). Although both Rbp9 and encore are involved in the regulation of cystocyte proliferation and differentiation through their interactions with bam, they have quite different mutant phenotypes (reference 14 and this study) and, thus, appear to act by distinct mechanisms. Because RBP9 binds to the 3′ UTR of bam transcripts in vitro, RBP9 may be involved in the destabilization of residual bam transcripts or in the process of making bam transcripts unsuitable for translation. This is consistent with our recent finding that the level of emc mRNA, which also interacts with RBP9 in vitro, is down regulated by Rbp9 in vivo (36).

The observations that RBP9 protein is concentrated in the oocyte of wild-type early-stage egg chambers and that mispositioned or abnormal numbers of oocytes were detected in hypomorphic Rbp9 mutants suggest that Rbp9 is required not only for cystocyte differentiation but also for oocyte development. This process could be mediated through a target RNA(s) other than the bam transcript. Because RBP9 binds to a rather simple RBP9 consensus binding sequence in vitro and this sequence is found in many transcripts, a number of RNAs expressed in the ovary have the potential to interact with RBP9 (36). However, the observation that all transcripts that contain the RBP9 consensus binding sequences are not regulated by RBP9 (36) suggests that additional cis- or trans-acting components must be required for the functional interaction of RBP9 with its specific target RNAs in vivo. Therefore, the identification of these additional factors is necessary to elucidate the mechanism by which RBP9 regulate its target RNAs.

Rbp9 appears to function in at least one more process during oogenesis. Although we did not observe gross egg chamber defects by DAPI staining in weak Rbp9 alleles (Rbp9P[2398] and Rbp9P[2567]), the fertility of these alleles measured by the number of eclosed adult flies remained low. This reduction in fertility can be explained in two ways. First, the overall number of eggs laid by the mutants was smaller than that laid by wild-type flies (data not shown). Second, eggs laid by the weak Rbp9 mutant flies were somewhat defective in axis formation. About 20% of the mutant embryos showed body patterning defects when determined by cuticle preparation. Posterior body patterning defects (45) were most often detected, while some embryos showed a dorsalized phenotype (data not shown). Therefore, Rbp9 appears to be required for multiple distinct developmental steps during oogenesis.

Although we detected several oogenesis defects in Rbp9 mutant flies, we observed no defect in CNS function. Serial sections of adult flies carrying either an Rbp9 null allele or wild-type Rbp9 were stained with DAPI, anti-RBP9 Ab, and monoclonal Ab (MAb) 22C10 (52) in order to visualize nuclei, RBP9, and neural cytoplasmic antigen, respectively. The nuclear staining patterns showed no morphological differences between wild-type and mutant flies, despite the lack of RBP9 protein in the mutant CNS (data not shown). Neurons from Rbp9 mutant strains expressed neuron-specific antigen, and axons stained normally with MAb 22C10. The absence of an effect on the nervous systems of Rbp9 mutant flies was extended further in that no obvious abnormalities were detected in flight, feeding, or mating behaviors (data not shown). The coexpression of ELAV and RBP9 in the adult CNS may provide functional redundancy.

Because perturbation of germ line sex determination has been reported with mutations that give rise to the tumorous ovarian phenotype (34), we examined the sex-specific pattern of Sex lethal (Sxl) pre-mRNA splicing in Rbp9 mutants with respect to the presence of the male-specific Sxl exon. The male-specific Sxl transcript was not observed in wild-type or Rbp9P[2567] females (data not shown). However, Rbp9P[2775] females had a small amount and Rbp9P[2690] homozygous females had a higher concentration of the male-specific Sxl transcript (data not shown). The observation that greater amounts of the male-specific Sxl transcript are produced in mutants with a more severe ovarian tumor phenotype implies that germ line sex determination is correlated with the cystocyte differentiation process of the germarium. Because the initial steps of the cystocyte differentiation process are very similar for oogenesis and spermatogenesis, the arrest of cystocyte development prior to the differentiation of egg chambers may send an erroneous signal to the cystocyte in the germarium causing the cells to follow a male-like developmental pathway.

Although Rbp9 is expressed mainly in postmitotic cells both in the CNS and in the ovaries, the distinct cellular localization patterns of RBP9 protein in each tissue type suggests a unique function for RBP9 in each location. SXL is another example of an RNA binding protein with distinct tissue-specific functions. SXL was originally identified as an alternative-splicing regulator in the somatic sex determination pathway (1, 6). Despite the presence of a considerable amount of cytoplasmic SXL protein in certain tissues, only the nuclear protein was considered to be functional. However, it was later shown that cytoplasmic SXL protein binds to the UTR of msl-2 mRNA and inhibits its translation (2, 17). Although SXL executes two different functions in two distinct cellular locations, both processes are mediated by the recognition of similar polypyrimidine elements that are found in the UTRs of msl-2 and the introns of genes involved in sex determination. The localization of RBP9 and SXL proteins in two distinct cellular compartments could be guided by their association with tissue-specific localization factors or by modification of their phosphorylation status. An understanding of the cellular processes that regulate protein localization should aid us in deciphering the mechanisms used by RBP9 and SXL in their various modes of developmental regulation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank J. Hall for the analysis of Rbp9 mutant behavior, I. Siden-Kiamos for cosmids, and the Berkeley Drosophila Genome Project for P-element lines. We also thank C. Kim for MAb 22C10. We offer special thanks to D. McKearin for BAM and HTS antibodies.

This work was supported by grants from SBRI (B-96-004) and Korea Science and Engineering Foundation, Republic of Korea (98-0403-04-01-5), to Y.-J.K. and J.K.-H.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baker B S. Sex in flies: the splice of life. Nature. 1989;340:521–524. doi: 10.1038/340521a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bashaw G J, Baker B S. The regulation of the Drosophila msl-2 gene reveals a function for Sex-lethal in translational control. Cell. 1997;89:789–798. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80262-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chagnovich D, Cohn S L. Binding of a 40-kDa protein to the N-myc 3′-untranslated region correlates with enhanced N-myc expression in human neuroblastoma. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:33580–33586. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.52.33580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen C Y, Xu N, Shyu A B. mRNA decay mediated by two distinct AU-rich elements from c-fos and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor transcripts: different deadenylation kinetics and uncoupling from translation. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:5777–5788. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.10.5777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chung S, Eckrich M, Perrone-Bizzozero N, Kohn D T, Furneaux H. The Elav-like proteins bind to a conserved regulatory element in the 3′-untranslated region of GAP-43 mRNA. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:6593–6598. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.10.6593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cline T W. A female-specific lethal lesion in an X-linked positive regulator of the Drosophila sex determination gene, Sex-lethal. Genetics. 1986;113:641–663. doi: 10.1093/genetics/113.3.641. . (Erratum, 114:345.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dalby B, Pereira A J, Goldstein L S. An inverse PCR screen for the detection of P element insertions in cloned genomic intervals in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 1995;139:757–766. doi: 10.1093/genetics/139.2.757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dalmau J, Graus F, Cheung N K, Rosenblum M K, Ho A, Canete A, Delattre J Y, Thompson S J, Posner J B. Major histocompatibility proteins, anti-Hu antibodies, and paraneoplastic encephalomyelitis in neuroblastoma and small cell lung cancer. Cancer. 1995;75:99–109. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19950101)75:1<99::aid-cncr2820750117>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fan X C, Steitz J A. Overexpression of HuR, a nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling protein, increases the in vivo stability of ARE-containing mRNAs. EMBO J. 1998;17:3448–3460. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.12.3448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gao F B, Carson C C, Levine T, Keene J D. Selection of a subset of mRNAs from combinatorial 3′ untranslated region libraries using neuronal RNA-binding protein Hel-N1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:11207–11211. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.23.11207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gateff E. Gonial cell neoplasm of genetic origin affecting both sexes of Drosophila melanogaster. Prog Clin Biol Res. 1982;85:621–632. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gonczy P, Matunis E, DiNardo S. bag-of-marbles and benign gonial cell neoplasm act in the germline to restrict proliferation during Drosophila spermatogenesis. Development. 1997;124:4361–4371. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.21.4361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Good P J. A conserved family of elav-like genes in vertebrates. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:4557–4561. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.10.4557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hawkins N C, Thorpe J, Schupbach T. Encore, a gene required for the regulation of germ line mitosis and oocyte differentiation during Drosophila oogenesis. Development. 1996;122:281–290. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.1.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jain R G, Andrews L G, McGowan K M, Gao F, Keene J D, Pekala P P. Hel-N1, an RNA-binding protein, is a ligand for an A + U rich region of the GLUT1 3′ UTR. Nucleic Acids Symp Ser. 1995;33:209–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kelley R L, Solovyeva I, Lyman L M, Richman R, Solovyev V, Kuroda M I. Expression of msl-2 causes assembly of dosage compensation regulators on the X chromosomes and female lethality in Drosophila. Cell. 1995;81:867–877. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90007-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kelley R L, Wang J, Bell L, Kuroda M I. Sex lethal controls dosage compensation in Drosophila by a non-splicing mechanism. Nature. 1997;387:195–199. doi: 10.1038/387195a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim Y-J. Studies on the RRM-type RNA binding protein gene family in Drosophila melanogaster. Doctoral thesis. Stanford, Calif: Stanford University; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim Y-J, Baker B S. The Drosophila gene rbp9 encodes a protein that is a member of a conserved group of putative RNA binding proteins that are nervous system-specific in both flies and humans. J Neurosci. 1993;13:1045–1056. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-03-01045.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim-Ha J, Kerr K, Macdonald P M. Translational regulation of oskar mRNA by bruno, an ovarian RNA-binding protein, is essential. Cell. 1995;81:403–412. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90393-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.King P H, Levine T D, Fremeau R T, Jr, Keene J D. Mammalian homologs of Drosophila ELAV localized to a neuronal subset can bind in vitro to the 3′ UTR of mRNA encoding the Id transcriptional repressor. J Neurosci. 1994;14:1943–1952. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-04-01943.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.King R C. Ovarian development in Drosophila melanogaster. New York, N.Y: Academic Press; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 23.King R C, Riley S F. Ovarian pathologies generated by various alleles of the otu locus in Drosophila melanogaster. Dev Genet. 1982;3:69–89. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koushika S P, Lisbin M J, White K. ELAV, a Drosophila neuron-specific protein, mediates the generation of an alternatively spliced neural protein isoform. Curr Biol. 1996;6:1634–1641. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)70787-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klug S J, Famulok M. All you wanted to know about SELEX. Mol Biol Rep. 1994;20:97–107. doi: 10.1007/BF00996358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levine T D, Gao F, King P H, Andrews L G, Keene J D. Hel-N1: an autoimmune RNA-binding protein with specificity for 3′ uridylate-rich untranslated regions of growth factor mRNAs. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:3494–3504. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.6.3494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lin H, Yue L, Spradling A C. The Drosophila fusome, a germline-specific organelle, contains membrane skeletal proteins and functions in cyst formation. Development. 1994;120:947–956. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.4.947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu J, Dalmau J, Szabo A, Rosenfeld M, Huber J, Furneaux H. Paraneoplastic encephalomyelitis antigens bind to the AU-rich elements of mRNA. Neurology. 1995;45:544–550. doi: 10.1212/wnl.45.3.544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ma W J, Cheng S, Campbell C, Wright A, Furneaux H. Cloning and characterization of HuR, a ubiquitously expressed Elav-like protein. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:8144–8151. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.14.8144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McKearin D, Ohlstein B. A role for the Drosophila bag-of-marbles protein in the differentiation of cystoblasts from germline stem cells. Development. 1995;121:2937–2947. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.9.2937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McKearin D M, Spradling A C. bag-of-marbles: a Drosophila gene required to initiate both male and female gametogenesis. Genes Dev. 1990;12:2242–2251. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.12b.2242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Myer V E, Fan X C, Steitz J A. Identification of HuR as a protein implicated in AUUUA-mediated mRNA decay. EMBO J. 1997;16:2130–2139. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.8.2130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ohlstein B, McKearin D. Ectopic expression of the Drosophila Bam protein eliminates oogenic germline stem cells. Development. 1997;124:3651–3662. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.18.3651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oliver B, Kim Y-J, Baker B S. Sex-lethal, master and slave: a hierarchy of germ-line sex determination in Drosophila. Development. 1993;119:897–908. doi: 10.1242/dev.119.3.897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oliver B, Perrimon N, Mahowald A P. The ovo locus is required for sex-specific germ line maintenance in Drosophila. Genes Dev. 1987;1:913–923. doi: 10.1101/gad.1.9.913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Park S-J, Yang E S, Kim-Ha J, Kim Y-J. Down regulation of extramacrochaetae mRNA by a Drosophila neural RNA binding protein RBP9 which is homologous to human Hu proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:2989–2994. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.12.2989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Peng S S, Chen C Y, Xu N, Shyu A B, Fan X C, Steitz J A. RNA stabilization by the AU-rich element binding protein, HuR, an ELAV protein. EMBO J. 1998;17:3461–3470. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.12.3461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rao V B. Direct sequencing of polymerase chain reaction-amplified DNA. Anal Biochem. 1994;216:1–14. doi: 10.1006/abio.1994.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Robertson H M, Preston C R, Phillis R W, Johnson-Schlitz D M, Benz W K, Engels W R. A stable source of P-element transposase in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 1988;118:461–470. doi: 10.1093/genetics/118.3.461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Robinow S, Campos A R, Yao K M, White K. The elav gene product of Drosophila, required in neurons, has three RNP consensus motifs. Science. 1988;242:1570–1572. doi: 10.1126/science.3144044. . (Erratum, 243:12, 1989.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Robinow S, White K. Characterization and spatial distribution of the ELAV protein during Drosophila melanogaster development. J Neurobiol. 1991;22:443–461. doi: 10.1002/neu.480220503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schupbach T. Normal female germ cell differentiation requires the female X chromosome to autosome ratio and expression of sex-lethal in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 1985;109:529–548. doi: 10.1093/genetics/109.3.529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Siden-Kiamos I, Saunders R D, Spanos L, Majerus T, Treanear J, Savakis C, Louis C, Glover D M, Ashburner M, Kafatos F C. Towards a physical map of the Drosophila melanogaster genome: mapping of cosmid clones within defined genomic divisions. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:6261–6270. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.21.6261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.St. Johnston D, Nusslein-Volhard C. The origin of pattern and polarity in the Drosophila embryo. Cell. 1992;68:201–219. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90466-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Storto P D, King R C. Multiplicity of functions for the otu gene products during Drosophila oogenesis. Dev Genet. 1988;9:91–120. doi: 10.1002/dvg.1020090203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Storto P D, King R C. The role of polyfusomes in generating branched chains of cystocytes during Drosophila oogenesis. Dev Genet. 1989;10:70–86. doi: 10.1002/dvg.1020100203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Szabo A, Dalmau J, Manley G, Rosenfeld M, Wong E, Henson J, Posner J B, Furneaux H M. HuD, a paraneoplastic encephalomyelitis antigen, contains RNA-binding domains and is homologous to Elav and Sex-lethal. Cell. 1991;67:325–333. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90184-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Torok T, Tick G, Alvarado M, Kiss I. P-lacW insertional mutagenesis on the second chromosome of Drosophila melanogaster: isolation of lethals with different overgrowth phenotypes. Genetics. 1993;135:71–80. doi: 10.1093/genetics/135.1.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang J, Dong Z, Bell L R. Sex-lethal interactions with protein and RNA. Roles of glycine-rich and RNA binding domains. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:22227–22235. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.35.22227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zaccai M, Lipshitz H P. Role of Adducin-like (hu-li tai shao) mRNA and protein localization in regulating cytoskeletal structure and function during Drosophila oogenesis and early embryogenesis. Dev Genet. 1996;19:249–257. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6408(1996)19:3<249::AID-DVG8>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zipursky S L, Venkatesh T R, Teplow D B, Benzer S. Neuronal development in the Drosophila retina: monoclonal antibodies as molecular probes. Cell. 1984;36:15–26. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90069-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]