Abstract

Objective:

To compare risks of maternal and perinatal outcomes by completed week of gestation from 39 weeks in low-risk nulliparous patients undergoing expectant management.

Methods:

We conducted a secondary analysis of a multicenter randomized trial of elective induction of labor (IOL) at 39 weeks vs. expectant management in low-risk nulliparous patients. Participants with non-anomalous neonates, who were randomized to and underwent expectant management and attained 39 0/7 weeks, were included. Delivery gestation was categorized by completed week: 39 0/7 to 39 6/7 (39 weeks), 40 0/7 to 40 6/7 (40 weeks) and 41 0/7 to 42 2/7 (41–42 weeks)(none delivered after 42 2/7). The co-primary outcomes were cesarean delivery and a perinatal composite (death, respiratory support, 5-minute Apgar score ≤3, hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy, seizure, sepsis, meconium aspiration syndrome, birth trauma, intracranial or subgaleal hemorrhage, or hypotension requiring vasopressor support). Other outcomes included a maternal composite (blood transfusion, surgical intervention for postpartum hemorrhage, or ICU admission), hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, peripartum infection, and neonatal intermediate or intensive care unit admission. For multivariable analysis, P<0.0125 was considered to indicate statistical significance for the co-primary outcomes.

Results:

Of 2502 participants who underwent expectant management, 964 (38.5%) delivered at 39 weeks, 1111 (44.4%) at 40 weeks and 427 (17.1%) at 41–42 weeks. The prevalence of medically indicated delivery was 37.9% overall and increased from 23.8% at 39 weeks to 80.3% at 41–42 weeks. The frequency of cesarean delivery (17.3%, 22.0%, 37.5%; p<0.001) and the perinatal composite (5.1%, 5.9%, 8.2%; p=0.03) increased with 39, 40, and 41–42 weeks of gestation respectively and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy decreased (16.4%, 12.1%, 10.8%, p=0.001). The adjusted relative risk, 95% confidence interval (39 weeks as referent) was significant for cesarean delivery at 41–42 (1.93, 1.61–2.32) weeks and for hypertensive disorders of pregnancy at 40 (0.71, 0.58–0.88) and 41–42 (0.61, 0.45–0.82) weeks. None of the other outcomes was significant.

Conclusion:

In expectantly managed low-risk nulliparous participants, the frequency of medically indicated IOL, and the risks of cesarean delivery but not the perinatal composite outcome, increased significantly from 39 to 42 weeks gestation.

Precis:

The frequency of medically indicated induction and risks of cesarean delivery and perinatal morbidity increase with gestational age in expectantly managed low-risk nulliparous patients.

Introduction

The results of the recent U.S. multicenter randomized trial of elective induction at 39 weeks versus expectant management (A Randomized Trial of Induction Versus Expectant Management [ARRIVE]) revealed that elective induction of labor (IOL) at 39 weeks in low-risk nulliparous participants did not significantly lower the frequency of a composite perinatal morbidity or death, but lowered the frequencies of cesarean delivery, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, and neonatal respiratory morbidity. [1–2] As a result, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine released recommendations suggesting that it is reasonable to offer IOL to low-risk nulliparous patients at 39 weeks. (3–4) Therefore, the rates of induction of labor in the US are expected to rise significantly above current rates of 1 in 4 births. (5) As these guidelines are implemented, it is useful to health care professionals and low-risk pregnant patients to have information regarding the natural course and outcomes of expectant management in order to optimize shared decision-making. (6) However, there is a paucity of contemporary, reliable and prospectively collected information regarding the ongoing risks of expectant management at 39 weeks among low-risk patients. Such data are essential to provide further insight into the study findings and to assist in the appropriate implementation of the new recommendations. Therefore, we used data from the A Randomized Trial of Induction Versus Expectant Management (ARRIVE) trial to estimate the risks of cesarean delivery, the perinatal composite outcome, and other outcomes of interest by completed week of gestation (GA) after 39 weeks in low-risk nulliparous patients who participated in the trial and underwent expectant management. We also describe the frequency of medically indicated IOL.

Methods:

This was a secondary analysis of ARRIVE, the multicenter open-label randomized trial of elective IOL at 39 0/7 to 39 4/7 weeks versus expectant management until at least 40 5/7 weeks but no later than 42 2/7 weeks in low-risk nulliparous patients. Details of the trial have been previously reported (1). Briefly, nulliparous patients were screened at 34–38 completed weeks of gestation at 41 US hospitals participating in the NICHD Maternal–Fetal Medicine Units Network and randomized at 38 0/7 to 38 6/7 weeks. Inclusion criteria included live cephalic singleton pregnancy, absence of a contraindication to vaginal delivery, no plan for cesarean delivery or labor induction at the time of randomization, and reliably determined gestational age consistent with ACOG guidelines. A reliable gestational age was defined by a sure last menstrual period consistent with a sonogram prior to 21 0/7 weeks or by a sonogram prior to 14 0/7 weeks if last menstrual period was uncertain. Exclusion criteria included the presence of any maternal or fetal indication for delivery prior to 40 5/7 weeks (e.g., hypertension, diabetes mellitus, fetal growth restriction, placental abruption). Trained and certified research staff abstracted information from medical records, including demographic information, medical, obstetrical, and social history, and outcome data. Institutional review board approval was available at each of the participating sites and written informed consent was obtained from participants before randomization.

The current analysis included only participants who were randomized to expectant management and attained 39 0/7 weeks. Participants without delivery outcomes or who delivered newborns with major fetal anomalies were excluded. For this analysis, delivery gestational age was categorized by completed week (39 weeks: 39 0/7 to 39 6/7 weeks, 40 weeks: 40 0/7 to 40 6/7 weeks and 41–42 weeks: 41 0/7 to 42 2/7 weeks; none delivered after 42 2/7 weeks).

The primary maternal outcome for this analysis was cesarean delivery. Other maternal outcomes examined were hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (preeclampsia or gestational hypertension), peripartum infection (chorioamnionitis and endometritis), placental abruption, shoulder dystocia and an adverse composite outcome comprising blood transfusion, B-lynch suture, uterine artery ligation, hypogastric artery ligation, vascular embolization, hysterectomy, or ICU admission.

The primary perinatal outcome for this analysis was the same perinatal composite as was used for the primary outcome of the ARRIVE trial: perinatal death, the need for respiratory support within 72 hours after birth, 5 minute Apgar score ≤3, hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy (HIE), seizure, infection (confirmed sepsis or pneumonia), meconium aspiration syndrome, birth trauma (bone fracture, neurologic injury, or retinal hemorrhage), intracranial or subgaleal hemorrhage, or hypotension requiring vasopressor support. Respiratory support was defined as use of continuous positive airway pressure, high-flow (>1 L/minute) nasal cannula, mechanical ventilation, or cardiovascular resuscitation within the first 72 hours of life. HIE was defined according to Shankaran criteria. (7) Secondary neonatal outcomes included neonatal intermediate or intensive care unit (NICU) admission, as well as a composite of neonatal death or stillbirth. We also estimated the frequency of medically indicated delivery and specific indications.

Categorical variables were compared by completed week of gestation at delivery using Cochran-Armitage trend test, or Monte-Carlo estimate for exact trend test for rare outcomes, and continuous variables using a Jonckheere Terpstra test. For multivariable analysis we applied log-binomial regression and modified Poisson regression and computed the adjusted relative risk (aRR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) for each week of gestation, 40 0/7 to 40 6/7 and 41 0/7 to 42 2/7 weeks compared with 39 0/7 to 39 6/7 weeks. Models for the maternal outcomes were adjusted for maternal age, smoking, and BMI at first clinic visit. Models for the perinatal and neonatal outcomes were adjusted for maternal age, smoking, BMI at first clinic visit, and fetal sex. We further examined whether the association between completed gestational age at delivery and outcomes were modified by cervical status (Modified Bishop score <5 vs. ≥5) at randomization, BMI (<30, 30–39 and ≥40 kg/m2), or participant-reported race-ethnicity (interactions). Alternative analyses evaluated outcomes among those who attained 39 0/7 weeks (those delivered after 39 6/7 weeks were compared with those delivered at 39 0/7 to 39 6/7 weeks) and among those that attained 40 0/7 weeks (those delivered after 40 6/7 weeks were compared with those delivered at 40 0/7 to 40 6/7 weeks). We chose not to adjust for race-ethnicity and insurance status in primary models as these are social determinants of health and did evaluate race-ethnicity in supplementary analyses. Statistical analyses were performed with SAS version 9.4.. A two-sided P<0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance for descriptive and unadjusted analyses. For multivariable analysis, P<0.0125 was considered to indicate statistical significance for the co-primary outcomes and for the secondary outcomes, the level of significance was adjusted post hoc for multiple comparisons with the false discovery rate method.(8) No imputation for missing data was performed.

Results:

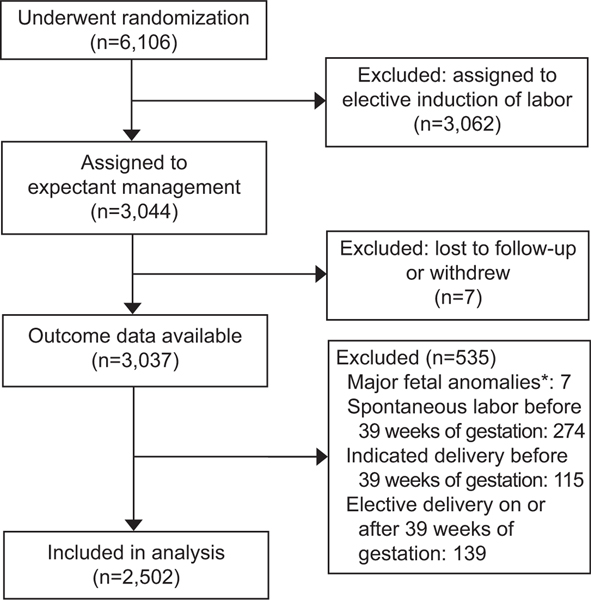

Of 6,106 participants, 3,037 of the 3,044 randomized to expectant management had outcome data. Of these, a total of 2,502 (82.4%) participants met eligibility criteria for this analysis (Figure 1). Excluded were 274 (9.0%) due to spontaneous labor and 115 (3.8%) with indicated delivery prior to 39 0/7 weeks, 139 (4.6%) electively delivered rather than expectantly managed after 39 0/7 weeks, and 7 (0.2%) due to major anomalies detected after delivery.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of eligibility determination for inclusion in this secondary analysis. *Major fetal anomalies: hypospadias (n=4), ambiguous genitalia male genotype (n=2), cleft palate (n=1)

Of the 2502 participants analyzed, 964 (38.5%) delivered at 39 0/7 to 39 6/7 weeks, 1111 (44.4%) at 40 0/7 to 40 6/7 weeks and 427 (17.1%) at 41 0/7 to 42 2/7 weeks; only 8 of the 427 delivered 42 0/7 to 42 2/7 weeks. Selected demographic characteristics at randomization differed by completed week of gestation at delivery (Table 1). The frequencies of modified Bishop score <5 (60.6% to 81.7%) and smoking (6.2% to 11.0%), and the medians of maternal age (23 to 24 years) and BMI (29.9 to 31.6 kg/m2) increased as delivery gestational age increased from 39 to 41–42 completed weeks (Table 1). Fewer participants who delivered at 41 0/7 to 42 2/7 weeks had private insurance compared with those who delivered earlier.

Table 1.

Maternal baseline characteristics by completed week of gestation

| Baseline characteristics | 39 0/7 to 39 6/7 | 40 0/7 to 40 6/7 | 41 0/7 to 42 2/7 | P for trend* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| weeks | weeks | weeks | ||

| N=964 | N=1111 | N=427 | ||

|

| ||||

| Maternal age (years) | 23 (20–28) | 24 (21–28) | 24 (21–29)** | 0.01 |

|

| ||||

| Race-ethnicity§ | ||||

|

| ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 404 (41.9) | 544 (49,0) | 183 (42.9) | |

|

| ||||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 246 (25.5) | 242 (21.8)** | 93 (21.8) | 0.06† |

|

| ||||

| Hispanic | 257 (29.7) | 263 (23.7)** | 120 (28.1) | 0.60† |

|

| ||||

| Other, unknown, or more than one race | 57 (5.9) | 62 (5.6) | 31 (7.3) | 0.72† |

|

| ||||

| Private insurance | 433 (44.9) | 508 (45.7) | 158 (37.0)** | 0.03 |

|

| ||||

| Maternal body mass index (kg/m2) ‡ | 29.9 (27.0–34.7) | 30.2 (27.3–34.7) | 31.6 (28.0–36.6)** | 0.001 |

|

| ||||

| Previous pregnancy loss before 20 weeks | 250 (25.9) | 282 (25.4) | 116 (27.2) | 0.74 |

|

| ||||

| Smoking | 60 (6.2) | 95 (8.6)** | 47 (11.0)** | 0.002 |

|

| ||||

| Gestational age at randomization (weeks) | 38.3 (38.0–38.6) | 38.3 (38.0–38.6) | 38.3 (38.0–38.4) | 0.22 |

|

| ||||

| Modified Bishop score <5 at randomization‡ | 584 (60.6) | 755 (67.9)** | 349 (81.7)** | <0.001 |

Data are N (%) or median (interquartile range), unless otherwise specified.

Based on Cochran-Armitage trend test for categorical variables and Jonckheere Terpstra test for continuous variables.

P-value for each race-ethnicity vs. White.

Maternal BMI missing in 16, modified Bishop score at randomization missing in 1.

P-value for pairwise comparisons 40 vs. 39 weeks and 41 vs. 39 weeks are <0.05

Race-ethnicity as reported by the participant. For analysis purposes, all patients identified as Hispanic ethnicity, regardless of race, were categorized as Hispanic. Among those that were not Hispanic, the “other” race-ethnicity category includes Asian, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, and American Indian/Alaskan Native.

The type of labor and reasons for delivery differed by completed week of gestation (Table 2). Spontaneous labor occurred in 1552 (62.0%) overall, decreasing from 76.2% among those who delivered at 39 0/7 to 39 6/7 weeks to 19.7% among those who delivered at 41 0/7 to 42 2/7 weeks. The proportion of women who had a cesarean delivery among those with spontaneous labor increased as gestational age advanced. The corresponding frequency of all medically indicated deliveries (including for the indication of post-dates) was 38.0% (n=950); 96.6% (n=918) were by induction and 3.4% (n=32) were by cesarean delivery without labor. The proportion of medically indicated deliveries increased from 23.8% for delivery at 39 0/7 to 39 6/7 weeks to 80.3% at 41 0/7 to 42 2/7 weeks. Among all reasons for medically indicated deliveries, postdates was the most common: this indication comprised 36.2% of medical indications at 40 0/7 to 40 6/7 weeks (specifically at 40 5/7 weeks and 40 6/7 weeks allowed by the study protocol), and 88.3% of medical indications at 41 0/7 to 42 2/7 weeks (Table 2). Other than postdates induction (at 40 completed weeks), hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and premature membrane rupture were the most common reasons for delivery at 39 or 40 completed weeks.

Table 2.

Type of labor by completed week of gestation

| Reason for delivery | 39 0/7 to 39 6/7 | 40 0/7 to 40 6/7 | 41 0/7 to 42 2/7 | P for trend* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| weeks | weeks | weeks | ||

| N=964 | N=1111 | N=427 | ||

|

| ||||

| Spontaneous labor | 735 (76.2) | 733 (66.0)** | 84 (19.7)** | <0.001 |

|

| ||||

| Cesarean delivery | 89 (12.1) | 123 (16.8) | 25 (29.8) | <0.001 |

|

| ||||

| Medically indicated delivery | 229 (23.8) | 378 (34.0) | 343 (80.3) | |

|

| ||||

| Induction | 214 (93.4) | 366 (96.8) | 338 (98.5)** | 0.001 |

|

| ||||

| Cesarean without labor | 15 (6.6) | 12 (3.2) | 5 (1.5) | |

|

| ||||

| Reasons for medically indicated delivery | ||||

|

| ||||

| Postdates | 0 (0.0) | 137 (36.2) | 303 (88.3) | |

|

| ||||

| Hypertension/preeclampsia | 80 (34.9) | 63 (16.7) | 6 (1.7) | |

|

| ||||

| Premature membrane rupture | 58 (25.3) | 51 (13.5) | 8 (2.3) | |

|

| ||||

| Oligohydramnios | 21 (9.2) | 40 (10.6) | 14 (4.1) | |

|

| ||||

| Non-reassuring fetal status | 34 (14.8) | 47 (12.4) | 7 (2.0) | |

|

| ||||

| Other medical reason | 36 (15.7) | 40 (10.6) | 5 (1.5) | |

Data are N (%) unless otherwise specified.

Based on Cochran-Armitage trend test.

P-value for pairwise comparisons 40 vs. 39 weeks and 41 vs. 39 weeks are <0.05

Among maternal and perinatal outcomes, the frequency of cesarean delivery (17.3%, 22.0%, 37.5%; p<0.001) and the adverse perinatal composite outcome (5.1%, 5.9%, 8.2%; p=0.03) increased significantly with 39, 40, and 41–42 completed weeks of gestation respectively, while the frequency of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy decreased significantly (16.4%, 12.1%, 10.8%, p=0.001) (Table 3). No significant changes as a function of gestational age were seen in the frequency of the maternal adverse composite outcome, placental abruption, peripartum infection, or NICU admission.

Table 3.

Maternal and perinatal outcomes by completed week of gestation

| Outcomes | 39 0/7 to 39 6/7 | 40 0/7 to 40 6/7 | 41 0/7 to 42 2/7 | P for trend* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| weeks | weeks | weeks | ||

| N=964 | N=1111 | N=427 | ||

|

| ||||

| Maternal | ||||

|

| ||||

| Cesarean delivery | 167 (17.3) | 244 (22.0)** | 160 (37.5)** | <0.001 |

|

| ||||

| Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy† | 158 (16.4) | 134 (12.1)** | 46 (10.8)** | 0.001 |

|

| ||||

| Peripartum infection‡ | 146 (15.2) | 187 (16.8) | 70 (16.4) | 0.42 |

|

| ||||

| Placental abruption | 6 (0.3) | 2 (0.2) | 2 (0.5) | 0.51§ |

|

| ||||

| Maternal Composite¶ | 26 (2.7) | 18 (1.6) | 14 (3.3) | 0.93 |

|

| ||||

| Blood transfusion | 20 (2.1) | 14 (1.3) | 13 (3.0) | 0.52 |

|

| ||||

| B-lynch stitch | 6 (0.6) | 4 (0.4) | 4 (0.9) | 0.71§ |

|

| ||||

| Uterine artery ligation | 2 (0.2) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.2) | 1.00§ |

|

| ||||

| Hysterectomy | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) | 0.17§ |

|

| ||||

| ICU admission | 3 (0.3) | 2 (0.2) | 2 (0.5) | 0.80§ |

|

| ||||

| Shoulder dystocia | 19 (2.0) | 26 (2.3) | 14 (3.3) | 0.16 |

|

| ||||

| Perinatal-neonatal | ||||

|

| ||||

| Perinatal composite║ | 49 (5.1) | 65 (5.9) | 35 (8.2)** | 0.03 |

|

| ||||

| Respiratory support | 39 (4.0) | 48 (4.3) | 27 (6.3) | 0.09 |

|

| ||||

| 5 minute Apgar ≤ 3 | 6 (0.6) | 5 (0.5) | 6 (1.4) | 0.24§ |

|

| ||||

| Hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy | 9 (0.9) | 5 (0.5) | 5 (1.2) | 0.98 |

|

| ||||

| Seizure | 2 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) | 1.00§ |

|

| ||||

| Infection | 4 (0.4) | 6 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0.51§ |

|

| ||||

| Meconium aspiration syndrome | 4 (0.4) | 12 (1.1) | 9 (2.1)** | 0.005§ |

|

| ||||

| Birth trauma | 6 (0.6) | 9 (0.8) | 2 (0.5) | 1.00§ |

|

| ||||

| Intracranial/subgaleal hemorrhage | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) | 5 (1.2)** | 0.004§ |

|

| ||||

| Hypotension requiring pressor support | 1 (0.1) | 2 (0.2) | 2 (0.5) | 0.22§ |

|

| ||||

| Stillbirth or neonatal death | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.5) | 0.03§ |

|

| ||||

| NICU admission | 121 (12.6) | 155 (14.0) | 71 (16.6)** | 0.05 |

NICU, neonatal intermediate or intensive care unit.

Data are N (%) unless otherwise specified.

Based on Cochran-Armitage trend test.

Preeclampsia or gestational hypertension.

Chorioamnionitis or endometritis.

Monte-Carlo estimate for exact trend test.

Defined as any of the following: blood transfusion, B-lynch, uterine artery ligation, hypogastric artery ligation, vascular embolization, hysterectomy, ICU admission.

Defined as any of the following: perinatal death, the need for respiratory support within 72 hours after birth, 5 minute Apgar score ≤3, hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy, seizure, infection (confirmed sepsis or pneumonia), meconium aspiration syndrome, birth trauma (bone fracture, neurologic injury, or retinal hemorrhage), intracranial or subgaleal hemorrhage, or hypotension requiring vasopressor support.

P-value for pairwise comparisons 40 vs. 39 weeks and 41 vs. 39 weeks are <0.05

The adjusted results when comparing outcomes of deliveries at 40 0/7 to 40 6/7 weeks and 41 0/7 to 42 2/7 weeks with 39 0/7 to 39 6/7 weeks as the referent were mostly consistent with the unadjusted results (Table 4). There were significant increases in the risk of cesarean delivery at 41 0/7 to 42 2/7 weeks (aRR 1.93, 95% CI 1.61–2.32) but not the perinatal composite (after adjustments) and decreases in the risk of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy at 40 0/7 to 40 6/7 weeks (aRR 0.71, 95% CI 0.58–0.88) and 41 0/7 to 42 2/7 weeks (aRR 0.61, 95% CI 0.45–0.82). Other maternal and perinatal outcomes were not significantly associated with gestational age at delivery. The numbers of participants experiencing placental abruption were too few for multivariable analysis.

Table 4.

Relative risks for maternal and perinatal outcomes by completed week of gestation vs. 39 weeks

| Outcomes | 40 0/7 to 40 6/7 weeks | 41 0/7 to 42 2/7 weeks | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| vs. 39 0/7 to 39 6/7 weeks | vs. 39 0/7 to 39 6/7 weeks | |||

| RR (95%CI) | aRR (95%CI) | RR (95%CI) | aRR (95%CI) | |

|

| ||||

| Maternal outcomes * | ||||

|

| ||||

| Cesarean delivery | 1.27 (1.06, 1.51) | 1.25 (1.05–1.49) | 2.16 (1.80, 2.60) | 1.93 (1.61–2.32) |

|

| ||||

| Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy | 0.74 (0.60, 0.91) | 0.71 (0.58–0.88) | 0.66 (0.48, 0.89) | 0.61 (0.45–0.82) |

|

| ||||

| Peripartum infection | 1.11 (0.91, 1.36) | 1.14 (0.93–1.39) | 1.08 (0.83, 1.41) | 1.12 (0.86–1.45) |

|

| ||||

| Maternal Composite | 0.60 (0.33, 1.09) | 0.66 (0.36–1.21) | 1.22 (0.64, 2.30) | 1.36 (0.71–2.61) |

|

| ||||

| Perinatal-neonatal outcomes † | ||||

|

| ||||

| Perinatal composite | 1.15 (0.80, 1.65) | 1.13 (0.79–1.62) | 1.61 (1.06, 2.45) | 1.56 (1.02–2.37) |

|

| ||||

| NICU admission | 1.11 (0.89, 1.14) | 1.09 (0.87–1.36) | 1.32 (1.01, 1.74) | 1.26 (0.96–1.66) |

aRR, adjusted relative risk; CI, confidence interval; NICU, neonatal intensive care unit.

Bold indicates p<0.05 for unadjusted comparisons, p<0.0125 for adjusted co-primary outcome comparisons (cesarean and perinatal composite), and significance for adjusted comparisons of secondary outcomes after controlling for multiple comparisons with the false discovery rate method.

Models adjusted for maternal age, smoking, and BMI at first clinic visit.

Models adjusted for maternal age, smoking, BMI at first clinic visit, and fetal sex.

Inclusion of race-ethnicity in the multivariable analysis did not change the results. No interactions between gestational age and modified Bishop score, BMI, or race-ethnicity were found to be significant for any of the study outcomes (all p-values >0.05).

In the alternative analyses, among participants who reached 39 0/7 weeks undelivered, the risk of cesarean delivery was higher among those delivered after 39 6/7 weeks compared with those delivered at 39 0/7 to 39 6/7 weeks (aRR 1.45; 95% CI 1.24–1.71), whereas the risk of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy was lower (aRR 0.68; 95% CI 0.56–0.83) (Table 5). Among participants who reached 40 0/7 weeks undelivered, the risk of cesarean delivery was higher among those delivered after 40 6/7 weeks compared with those delivered at 40 0/7 to 40 6/7 weeks (aRR 1.56; 95% CI 1.33–1.84).

Table 5.

Relative risks for maternal and perinatal outcomes by completed week of gestation vs. deliveries in the previous week

| Outcomes | Among those that reached 39 0/7 weeks undelivered | Among those that reached 40 0/7 weeks undelivered | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=2,501 | N=1,537 | |||

|

| ||||

| 40 0/7 to 42 2/7 weeks | 41 0/7 to 42 2/7 weeks | |||

| vs. 39 0/7 to 39 6/7 weeks | vs. 40 0/7 to 40 6/7 weeks | |||

| RR (95%CI) | aRR (95%CI) | RR (95%CI) | aRR (95%CI) | |

|

| ||||

| Maternal outcomes * | ||||

|

| ||||

| Cesarean delivery | 1.52 (1.29, 1.78) | 1.45 (1.24–1.71) | 1.71 (1.45, 2.01) | 1.56 (1.33–1.84) |

|

| ||||

| Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy | 0.71 (0.59, 0.87) | 0.68 (0.56–0.83) | 0.89 (0.65, 1.22) | 0.87 (0.63–1.19) |

|

| ||||

| Peripartum infection | 1.10 (0.92, 1.33) | 1.13 (0.94–1.37) | 0.97 (0.76, 1.25) | 0.99 (0.77–1.27) |

|

| ||||

| Maternal Composite | 0.77 (0.46, 1.29) | 0.85 (0.50–1.44) | 2.02 (1.01, 4.07) | 2.05 (1.00–4.20) |

|

| ||||

| Perinatal-neonatal outcomes † | ||||

|

| ||||

| Perinatal composite | 1.28 (0.92, 1.78) | 1.25 (0.90–1.74) | 1.40 (0.94, 2.08) | 1.42 (0.96–2.12) |

|

| ||||

| NICU admission | 1.17 (0.95, 1.44) | 1.13 (0.92–1.39) | 1.19 (0.92, 1.54) | 1.17 (0.90–1.52) |

aRR, adjusted relative risk; CI, confidence intervals; NICU, neonatal intensive care unit.

Bold indicates p<0.05 for unadjusted comparisons, p<0.0125 for adjusted co-primary outcome comparisons (cesarean and perinatal composite), and significance for adjusted comparisons of secondary outcomes after controlling for multiple comparisons with the false discovery rate method.

Models adjusted for maternal age, smoking, and BMI at first clinic visit.

Models adjusted for maternal age, smoking, BMI at first clinic visit, and fetal sex.

Discussion

Among nulliparous participants who were expectantly managed beyond 39 0/7 weeks gestation, we found an increasing risk of both an adverse composite perinatal outcome and cesarean delivery with increasing gestational age. However, after adjustments in multivariable analysis, the risk of cesarean delivery was 25% higher at 40 0/7 to 40 6/7 weeks and 93% higher 41 0/7 to 42 2/7 weeks compared with 39 0/7 to 39 6/7 weeks. The perinatal composite outcome was 56% higher at 41 0/7 to 42 2/7 weeks but did not meet criteria for statistical significance. In contrast, the prevalence of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy decreased with advancing gestational age. Although two-thirds of participants who undergo expectant management will labor spontaneously, the frequency of medically indicated delivery increased with advancing gestational age. Post-dates induction, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, and premature membrane rupture were the most common reasons for medically indicated delivery.

Since the publication of the ARRIVE trial, a meta-analysis of cohort studies of elective IOL at 39 0/7 to 39 6/7 weeks as compared with expectant management has been reported. (9) The results of this meta-analysis revealed that elective IOL was associated with a reduction in cesarean delivery, peripartum infection, and adverse perinatal outcomes. These findings lend additional support to the recommendations by professional organizations to offer elective IOL to low-risk nulliparous patients. (3–4) Our study focusing on participants who underwent expectant management addresses some questions that remained unanswered regarding perinatal outcomes on patients expectantly managed beyond 39 0/7 weeks. (6, 10)

Limited data were reported following a UK randomized trial of IOL vs. expectant management involving 619 primigravid participants who were 35 years of age or older, which preceded the ARRIVE trial. Findings from the trial suggested that 46% of participants in the expectant management group had spontaneous labor, 49% had induction of labor, and 2% had cesarean delivery without labor. (11) Furthermore the main reasons for IOL were similar.

Our findings are also supported by data from cohort studies that have simulated expectant management (6,12–14) - most deliveries occur at 39–40 completed weeks, the most common reasons for inductions are similar, and cesarean delivery increases with advancing gestational age. Although the cesarean delivery rates in nulliparous patients were higher at corresponding gestational ages in other studies compared with the rates in the ARRIVE trial, this likely reflects the inclusion only of low-risk participants in our cohort. (11–12) The decrease in hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (in contrast to increase in cesarean delivery) with advancing gestational age after 39 0/7 to 39 6/7 weeks is surprising and deserves further investigation. For reference, the overall rate of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy in the primary ARRIVE paper was 9.1% in the labor induction group and 14.1% in the expectant management group, compared with an overall 13.5% in the expectant management group in this paper and the 16.4% at 39 0/7 to 39 6/7 weeks, 12.1% at 40 0/7 to 40 6/7 weeks and 10.8% at 41 0/7 to 42 2/7 weeks in the expectant management group. The difference is due to the slight variation in inclusion/exclusion criteria for this analysis. A query of the PubMed database using key words preeclampsia, hypertensive disorders and timing of delivery or gestational age of delivery, did not yield any publication reporting such a trend. We do not believe that the incidence of preeclampsia decreases with advancing gestational age. It may reflect an increase in the prevalence of competing indications for delivery such as postdate inductions as gestational age advances (Table 2). Other indications for delivery were more likely to be prevalent than preeclampsia among deliveries with advancing gestational age.

We acknowledge a number of study limitations. Some of the specified outcomes such as stillbirth or neonatal death were too infrequent to conduct any meaningful analyses. In the ARRIVE trial, only nulliparous participants are included, limiting generalizability. We did not account for multiple comparisons or center differences; some of the findings could be due to chance or center practices, such as the association of insurance status with gestational age at delivery. However, no center effect in relation to outcomes was noted in the primary trial. (1) There are several strengths of the study. These data are relatively novel as there are limited, if any, such data from large randomized trials. The analysis uses prospectively collected data by certified research staff, enhancing validity. The sample size is large enough to evaluate the key outcomes.

Overall, these data provide important insights into the anticipated course of expectant management of low-risk nulliparous patients who would typically be candidates for elective IOL. The information will be useful for counseling patients regarding ongoing risks of expectant management, and optimizing shared decision making. About two-thirds of expectantly managed participants on average labored spontaneously after 39 weeks but the frequency decreased with advancing gestational age. Conversely, the frequencies of medically indicated IOL and cesarean delivery increased with gestational age.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment:

The authors thank Elizabeth A. Thom, PhD for protocol development and oversight.

Supported by grants (HD40512, HD36801, HD27869, HD34208, HD68268, HD40485, HD40500, HD53097, HD40560, HD40545, HD27915, HD40544, HD34116, HD68282, HD87192, HD68258, HD87230) from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (UL1TR001873). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Presented in part at the Annual Scientific Meeting of the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, February 14-16, 2019, Las Vegas, NV.

Footnotes

Dr. Rouse, Editor-in-Chief of Obstetrics & Gynecology, was not involved in the review or decision to publish this article.

Financial Disclosure

Robert M. Silver disclosed that he is a consultant for Gestvision. Alan T. Tita, Edward K. Chien and Hyagriv N. Simhan disclosed that money was paid to his institution for industry research studies for clinical trials. Hyagriv N. Simhan disclosed that he is a cofounder of Naima Health, LLC. Geeta K. Swamy disclosed receiving funding from GlaxoSmithKline and Pfizer. George Saade disclosed that he is a consultant for Medicem. The other authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

Each author has confirmed compliance with the journal’s requirements for authorship.

PEER REVIEW HISTORY

Received August 10, 2020. Received in revised form October 27, 2020. Accepted October 29, 2020. Peer reviews are available at http://links.lww.com/xxx.

References

- 1.Grobman WA, Rice MM, Reddy UM, Tita ATN, Silver RM, Mallett G, et al. Labor Induction versus Expectant Management in Low-Risk Nulliparous Women. The New England journal of medicine. 2018;379(6):513–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Greene MF. Choices in Managing Full-Term Pregnancy. The New England journal of medicine. 2018;379(6):580–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.ACOG Practice Advisory: Clinical guidance for integration of the findings of The ARRIVE Trial: Labor Induction versus Expectant Management in Low-Risk Nulliparous Women [Google Scholar]

- 4.SMFM Statement on Elective Induction of Labor in Low-Risk Nulliparous Women at Term: the ARRIVE Trial. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2018. Epub 2018/08/14. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2018.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Little SE. Elective Induction of Labor: What is the Impact? Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2017;44(4):601–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carmichael SL, Snowden JM. The ARRIVE Trial: Interpretation from an Epidemiologic Perspective. J Midwifery Women’s Health 2019July2:doi 10.1111/jmwh, 12996 [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shankaran S, Laptook AR, Ehrenkranz RA, et al. Whole-body hypothermia for neonates with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. N Engl J Med 2005;353:1574–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc [B] 1995; 57: 289–300 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grobman WA, Caughey AB. Elective induction of labor at 39 weeks compared with expectant management: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2019October.;221(4):304–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marrs C, LaRose M, Caughey A, Saade G. Elective Induction at 39 Weeks of Gestation and the Implications of a Large, Multicenter, Randomized Controlled Trial. Obstet Gynecol 2019March;133(3):445–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Walker KF, Bugg GJ, Macpherson M, et al. Randomized trial of labor induction in women 35 years of age or older. N Engl J Med 2016;374:813–822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Darney BG, Snowden JM, Cheng YW, Jacob L, Nicholson JM, Kaimal A, Dublin S, Getahun D, Caughey AB. Elective induction of labor at term compared with expectant management: maternal and neonatal outcomes. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(4):761–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stock SJ, Ferguson E, Duffy A, Ford I, Chalmers J, Norman JE. Outcomes of elective induction of labour compared with expectant management: population based study. BMJ. 2012;344:e2838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Glantz JC. Term labor induction compared with expectant management. Obstet Gynecol. 2010January;115(1):70–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.