Abstract

Objective

We sought to better understand how social factors shape HIV disclosure to children from the perspective of caregivers and HIV-infected children in Kenya.

Design

We conducted a qualitative study using focus group discussions (FGDs) to gain perspectives of caregivers and children on the social environment for HIV disclosure to children in western Kenya. FGDs were held with caregivers who had disclosed the HIV status to their child and those who had not, and with HIV-infected children who knew their HIV status.

Methods

FGD transcripts were translated into English, transcribed, and analyzed using constant comparison, progressive coding, and triangulation to arrive at a contextualized understanding of social factors influencing HIV disclosure.

Results

Sixty-one caregivers of HIV-infected children participated in eight FGDs, and 23 HIV-infected children participated in three FGDs. Decisions around disclosure were shaped by a complex social environment that included the care-giver–child dyad, family members, neighbors, friends, schools, churches, and media. Whether social actors demonstrated support or espoused negative beliefs influenced caregiver decisions to disclose. Caregivers reported that HIV-related stigma was prominent across these domains, including stereotypes associating HIV with sexual promiscuity, immorality, and death, which were tied to caregiver fears about disclosure. Children also recognized stigma as a barrier to disclosure, but were less specific about the social and cultural stereotypes cited by the caregivers.

Conclusion

In this setting, caregivers and children described multiple actors who influenced disclosure, mostly due to stigmatizing beliefs about HIV. Better understanding the social factors impacting disclosure may improve the design of support services for children and caregivers.

Keywords: adherence, adolescents, disclosure of HIV status, mental health, resource-limited setting

Introduction

There are over 3.4 million children under 15 years of age living with HIV, 90% of who live in sub-Saharan Africa [1,2]. For these children, learning their HIV diagnosis –typically referred to as HIV disclosure – is a critical step in their long-term disease management and in the transition to adolescent and adult care settings [3,4]. In many resource-limited settings, however, disclosure of HIV status to children is not well characterized and best practices for disclosure are unknown [5]. Children in low and middle-income countries are less likely to know their HIV status compared to children in high-income countries, and they typically learn about their HIV status at older ages [6].

Caregivers in both resource-rich and resource-poor settings report weighing potential risks and benefits of disclosure to children [5,6]. Caregivers often cite the child’s increasing age, independence, and adherence to medications as reasons to disclose, whereas fears about negative emotional effects often discourage disclosure [7–9]. To a lesser degree, social factors at the interpersonal and community level have also been identified as shaping decisions around disclosure. For example, fear of the child telling others about his/her HIV status, and subsequent stigma and discrimination towards the child, caregiver, or family, have been stressed by caregivers in previous studies as a major barrier to disclosure [10–12].

In an effort to better understand the social context and process of disclosure to children, we conducted focus groups with caregivers of HIV-infected children and HIV-infected children who knew their own status in care at HIV clinics in Kenya. This article adds to the limited literature base on disclosure of HIV status to children in sub-Saharan Africa and describes the major themes identified in these focus groups, specifically about the social actors and beliefs that impact disclosure of HIV status to children.

Methods

Setting and population

The Academic Model Providing Access to Healthcare (AMPATH) program in western Kenya is a long-standing collaboration between Moi University School of Medicine, Moi Teaching and Referral Hospital (MTRH) and a consortium of North American academic medical centers led by Indiana University School of Medicine [13,14]. Caregivers and HIV-infected children for this study were recruited from three AMPATH clinics – a large urban clinic at MTRH in Eldoret (a major city in Kenya) and two semi-urban clinics in Burnt Forest and Kitale. These clinics were selected because of their large pediatric HIV-infected populations, and their good ethnic and geographic diversity, which strengthen their representativeness for the larger AMPATH population in western Kenya. AMPATH’s current protocol on disclosure recommends beginning disclosure by age 10, and includes disclosure training for AMPATH clinicians.

Study design

We conducted a qualitative study using focus group discussions (FGDs) with caregivers of HIV-infected children and HIV-infected children 10–16 years old who knew their HIV status. FGDs were used to elicit perspectives of caregivers and children on disclosure of HIV status to infected children and the social factors that shape decisions around whether or not to disclose. Caregivers and children were recruited separately, and the child participants did not necessarily represent the children of caregiver participants. Separate FGDs were held for caregivers who had disclosed to one or more of their children and caregivers who had not disclosed. Convenience sampling was used to recruit study participants, who were referred to the study team by clinicians, nurses, and other clinic staff, or self-referred for participation from fliers placed at the study clinics. All participants had to give written informed consent (caregivers) and assent (children) prior to participation in FGDs. In addition, the parental guardian of child participants had to provide written consent for the child’s participation.

A total of 11 FGDs were held between 13 September 2013 and 23 October 2013. FGDs were audiotaped and led by a trained facilitator in Kiswahili – one of the national languages of Kenya and the most widely spoken language in western Kenya. The facilitator used semi-structured interview guides containing open-ended questions (listed below) to solicit responses during the 2-h sessions (interview guides are available from the authors upon request).

Examples of questions asked to caregivers who had not disclosed (questions in FGDs with caregivers who had disclosed and children differed slightly, but all questions covered the same general themes, as illustrated below):

-

Perspectives on HIV disclosure

Please tell us a story about someone you know who has told a child that they are infected with HIV.

-

It is difficult to be present every time your child is supposed to take his/her medications. Sometimes, it can be helpful if someone else knows about your child’s medical condition. Does anyone know that your child takes medicines for HIV?

Does anyone else help you care for your child? Does anyone else help your child take his or her medicines?

To what extent is your child responsible for taking his/her own medicines?

What do you think about telling other people that your child has HIV?

How do you feel about giving your child medicine for HIV in front of others?

-

We understand that telling your child they have HIV is a very difficult task. Again, there are many good reasons why parents have chosen not to tell their child they have HIV. We would like to learn about your thoughts about disclosure to a child so that we can better understand the difficulties that parents and caregivers have.

Could you share with us some of the reasons why you have not told your child that they have HIV?

Do you feel like you have a group of people who help support you? Do you think that this group will help you after you have disclosed your child’s HIV status to the child?

-

Do you know anyone who has told their own child that they have HIV?

What was that experience like for them?

Have any of these experiences influenced your own decision to disclose or not disclose to your child? Why or why not?

-

Social environment for disclosure

-

Caring for a child who is infected with HIV can be very difficult. Many parents tell us that it is more difficult when family members or others in their community or in their village do not support them. How is it for you in your community?

How do the elders of your tribe react to HIV?

How do the mothers of your tribe react to HIV?

How do the religious people – the pastors –treat those with HIV?

How do other children react if they know that a child has HIV?

What is the reaction of a child who learns that he or she has HIV themselves?

-

The authors created the interview guides, which were informed by grounded theory, previous qualitative and quantitative work on disclosure, the input of local healthcare providers, and a review of relevant literature, and covered community beliefs about HIV, stigma and discrimination, and benefits and risks of disclosure [5]. All of the recordings were transcribed and translated into English by a trained translator. Translations were checked for face validity by a bilingual study investigator. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Indiana University School of Medicine in Indianapolis, Indiana, USA and by the Institutional Research and Ethics Committee of Moi University School of Medicine and MTRH in Eldoret, Kenya.

Data analysis

The transcripts of FGDs were analyzed using a system of manual, progressive coding to identify central concepts [15,16]. The initial stage of constant comparative analyses was done through open coding by two investigators. Line-by-line analysis of each transcribed page from FGDs was completed to elucidate meanings and processes. Lines were coded using the qualitative analysis software Dedoose – a web application for managing, analyzing, and presenting qualitative and mixed method research data (Dedoose Version 4.12.0, SocioCultural Research Consultants, LLC: Los Angeles, California, USA). The same investigators independently extracted and compared themes. Both the open codes and the themes extracted by the two investigators revealed high degrees of agreement (>90%). Before condensing the codes, two different investigators read through all data, reviewed preliminary coding, and recoded based on consensus. We then performed axial coding – the process of relating categories to their subcategories and linking them together at the level of properties and dimensions [15,16] – to organize the themes into relevant relationships. Key themes and concepts were developed inductively from the data. Established socio-ecological models, namely Bronfenbrenner’s socio-ecological model for human development [17], were used to guide our understanding of how micro and macro factors in the social environment individually and collectively impact HIV disclosure in western Kenya. Selected quotations were identified to illustrate dominant themes.

Results

Study participants

Data were collected from 61 caregivers of HIV-infected children who participated in eight FGDs, and 23 HIV-infected children who participated in three FGDs. Although some participants did not give their age (missing data for 7 caregivers), caregiver-reported mean age was 43.2 years and there was no significant difference in age between caregivers who had disclosed and those who had not disclosed. The majority of caregivers had not disclosed the HIV status to their child (62%). Caregiver participants were most commonly the biological mother of an HIV-infected child (43%), a grandparent (23%), or an uncle or aunt (17%). The average age of child participants was 13.5 years. The average self-reported age of disclosure within the child groups was 11 years of age, although three children did not give an age at which they were disclosed to.

Perspectives on the social environment of child HIV disclosure

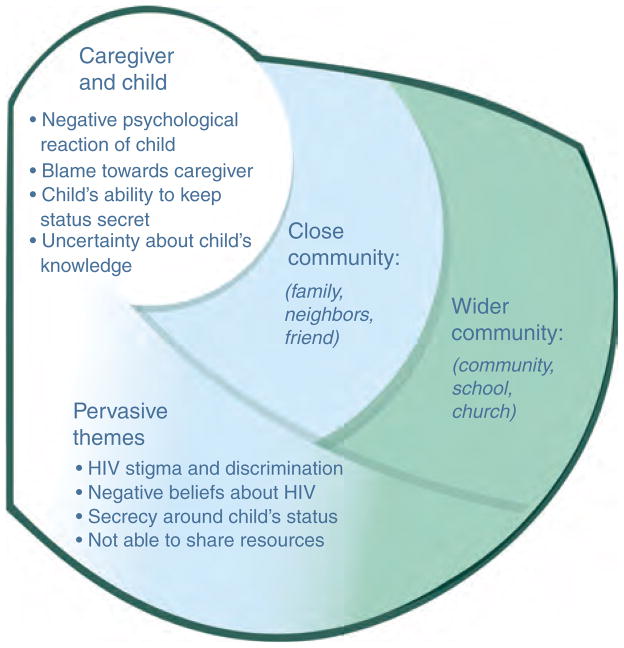

In this setting, caregivers described a complex social environment that influenced all aspects of HIV disclosure to children. We identified three major domains within which disclosure takes place: caregiver/child; family, neighbors, friends (‘close community’); and school, church, and media (‘wider community’) (Fig. 1). Within each domain, caregivers described distinct and overlapping factors that influenced decisions about disclosure. Several themes reached across all domains (‘pervasive themes’), including negative beliefs about HIV and HIV-related stigma and discrimination.

Fig. 1.

Domains of HIV Disclosure to Infected Children in Kenya.

Pervasive themes

Negative beliefs about HIV were defining characteristics of the social context for if, when, and how disclosure took place. One of the most common themes from caregiver and child FGDs was that many people believe HIV is associated with immorality and is transmitted through sexual ‘promiscuity’. Caregivers, particularly those who had not disclosed, felt these negative beliefs about HIV contributed to their fears that their child would blame the caregiver for HIV infection or be confused about how they – as a child – could be infected, since they had not been sexually active themselves. Although children were less likely to identify specific stigmatizing stereotypes, such as sexual promiscuity, they were still aware of the stigma surrounding HIV. Caregivers and children also shared that many in the community think of HIV as a terminal disease, associated with extreme illness and inevitable death, although a number of participants suggested that this is slowly changing as more people access treatment and remain healthy and active with HIV.

Caregiver–child domain

A number of themes at the level of the caregiver–child domain were prominent in decisions around disclosure (Table 1). The potential negative reaction a child may have upon learning his or her HIV status was a major concern expressed by caregivers who had not disclosed to their child. These potential reactions included the child experiencing emotional or psychological harm, reacting with ‘shock’ or becoming ‘stressed’, and even committing suicide. This concern was echoed in the child FGDs, both in an understanding that caregivers were concerned about the child’s emotional well being and in reporting their own shock upon learning their HIV status, although no child discussed having suicidal thoughts. Another feared consequence of disclosure recognized by both caregivers and children was that the child might blame the caregiver for their infection. In caregiver FGDs, this fear of blame was often tied to beliefs about HIV being associated with immorality and promiscuity. Children, on the contrary, more often focused on blaming caregivers for lying to the child about their status and not disclosing sooner.

Table 1.

Disclosure themes from the child/caregiver domain.

| Theme | Illustrative quote |

|---|---|

| Fears that child will be harmed psychologically | Even though we are longing to tell them, we are wondering what will happen if we tell them. Like I am thinking, ‘If I tell her, she will be shocked and become unconscious.’ Caregiver, not discloseda . . .the child might suffer and get depressed so the parent might fear telling her/him. Hence, decide to wait for the right time to disclose. Childb |

| Fears that the child will blame the caregiver | A child might also ask you how she was infected with the disease, yet she is still very young. She will form a very bad opinion of you and say, ‘My mom was very immoral. She was moving around with men, got the disease, and infected me.’ So one feels the child will look at you and say you are immoral. Caregiver, disclosed In my condition, I think the parents may feel that we are going to blame them for the condition. Child |

| Fears of disclosure beyond the child/caregiver domain | I said I will [disclose] when she can be able to keep secrets and not spread the news to other children. Caregiver, not disclosed It really affected me even though I had not told anybody. I was scared. What if I told somebody? Child |

| Not knowing what the child already knows about HIV/AIDS or their own HIV status | I have never talked to my child [about HIV] . . . I don’t know what they are taught in school. Caregiver, not disclosed |

Denotes caregiver disclosure status: not disclosed – the caregiver had not disclosed to any of their children; disclosed – the caregiver had disclosed to one or more of their children.

All child participants in this study were disclosed – that is, knew their HIV status.

Another prominent concern among caregivers who had not disclosed was how the child would interact with others once disclosure took place. A major fear shared by caregivers was that the child would talk about their HIV status with others and that this would lead to stigma towards the child and perhaps towards the caregiver and family. Children understood that caregivers were concerned about their ability to keep their HIV status a secret, and also expressed concern about their own ability to keep the diagnosis private. This seemed to be related closely with the child’s cognitive and social development, and whether the child had the ability to understand that their HIV status could lead to social disadvantage, and the subsequent need to keep it a secret.

Many caregivers – both those who had disclosed and those who had not – expressed that they thought their children started ‘putting the pieces together’ about their HIV status before disclosure took place. Caregivers implied that this made disclosure more difficult because they did not know how much the child knew and when to start the disclosure process. With little to no direct communication with their children about HIV, many caregivers described lying to the child about the reasons for taking medicines or going to the clinic, and were hesitant to trust them with knowledge of their diagnosis. Common reasons caregivers gave their children for taking medicines and attending clinic were rashes, tuberculosis or other chest problems, malaria, and stomach problems. In contrast to caregivers’ feelings about their children already suspecting or knowing their HIV status, children largely denied knowing their status before they were directly told by a caregiver or healthcare provider.

Close community domain

Outside of the proximal domain of the caregiver–child, caregivers and children in FGDs identified that the closest individuals around them – family, neighbors, and friends – shaped many aspects of disclosure (Table 2). The most prominent theme within this domain was the stigma and discrimination these individuals demonstrated towards the caregiver or child because of the child’s HIV status. Caregivers and children both described experiences of discrimination at the hands of family and friends, ranging from individuals no longer sharing common household items like a water basin to not even being allowed to sleep in the family’s home. A few caregivers specifically highlighted the challenging family dynamics of having multiple children in a household, some of whom were HIV-infected and others who were not. Stigma was not only at the level of adults either; children shared experiences of HIV stigma at the hands of peers as well. Child-to-child discrimination took the forms of not wanting to play with an infected child, not wanting to share toys, and otherwise teasing and ridiculing them.

Table 2.

Disclosure themes from the close community domain.

| Theme | Illustrative quote |

|---|---|

| Stigma and discrimination from family members | There was a time when my husband tried to chase me and the child away . . . I was really disturbed . . . We were given a prescription to buy medicine so I took it to [my husband.] When I tried to insist [on getting the medicine] because the condition of the child was not good, I was told to pack and leave with my ‘luggage,’ meaning the child. He was very hard, and we had to spend the night in the neighbor’s house. The issue is bothering me, but I don’t have a place where I can take the child. If I die today, it is only God who can help her. “Caregiver, disclosed”a |

| . . . my uncles from my mother’s side never wanted to see me . . . but I thank God that my uncles have come to realize that being positive is not a big thing – it is just the same. “Child”b | |

| Stigma and discrimination from neighbors and friends | [My] neighbor will not say directly that you have HIV but if you try to borrow something, she will give you an excuse like she doesn’t share . . . You will realize that people begin to isolate [you] and ask you funny questions like, ‘Where are you coming from? You are smelling medicine from the district hospital.’ That means the other neighbor has spread the news to others. You might have thought it wise to share the secret with the neighbor, but you will have made the situation worse. “Caregiver, not disclosed” |

| They don’t want one to share items with others [with HIV] – for example, a nail cutter. At times, during meals times, your plate is isolated; you are not allowed to share many items with them. “Child” | |

| Keeping the child’s HIV status secret to others | I don’t like the idea of telling other people about the status of the child, that is, outsiders. Not everybody will have positive thoughts once he/she learns the status of the child. Caregiver, disclosed |

| She can tell a friend that her mother told her she is HIV positive, the friend goes and tells another person then the news spreads to the whole school. Later on other pupils isolate her saying she is HIV positive “Child” | |

| Taking medicines in private, lying about reasons for taking medicines or going to clinic | You should give [medicines] in the morning and in the evening when others are not around. When we are just the two of us or when the elder brother is present, [I give the medicines, but] I have never given them in the presence of others. “Caregiver, not disclosed” |

| Support from friends and families in caring for the child | [I told] my family members that [the child] must go with his medication. If they know [his status], they will ensure he takes [his medication] as required. You can’t stay with the child all the time. He has to visit others. “Caregiver, disclosed” |

| I take [medication] on my own, but at times my grandmother reminds me. “Child” | |

| Stigma and discrimination from peers | But when I was in class 8 it was really terrible. It hit me like, ‘Now it has happened. They have all run away from me.’ My mum would not come to stay with me in school. Who am I going to share this with? Who will I call a friend? I was all alone, but one of the teachers called me and told me, ‘You are HIV+ but don’t be afraid, all will be good.’ “Child” |

Denotes caregiver disclosure status: not disclosed – the caregiver had not disclosed to any of their children; disclosed – the caregiver had disclosed to one or more of their children.

All child participants in this study were disclosed – i.e., knew their HIV status.

In response to both fears and experiences of discrimination, many caregivers described trying to keep the child’s HIV status secret from individuals close to the caregiver and child, as well as delaying disclosure. These attempts at secrecy impacted social behaviors around HIV management, resulting in practices like going to treatment facilities in a clandestine fashion and making sure the child took medicines in private. Children also preferred secrecy and almost unanimously described feeling uncomfortable or ashamed when taking medicines in front of others. Caregivers described individuals in the close community inquiring suspiciously as to why the caregiver is taking the child (or themselves) to clinic and taking medicines, which led to caregivers lying to others about the child’s health status and reasons for seeking treatment.

Some caregivers, particularly those who had disclosed, and children described a more supportive environment within their close circles of family and friends, with these individuals offering emotional and psychological support related to the child’s HIV status, and physical support such as helping to care for the child. For example, a number of caregivers and children described family and friends, making sure the child took his or her medicines, particularly when the caregiver was not present. In these situations, the close community seemed to provide needed support for the caregiver and child, and eased the challenge of disclosure.

Wider community domain

As described above, most caregivers (those who had and had not disclosed) and children treated HIV status as a closely guarded secret, especially outside of close circles of family and friends (Table 3). One caregiver said simply, ‘This is your own secret.’ The more distant a social actor’s relationship to the caregiver and child, the less likely the caregiver would share information about the child’s HIV status. Caregivers cited particular fears of discrimination towards the child if the child’s status was revealed to individuals at church and at school.

Table 3.

Disclosure themes from the wider community domain.

| Theme | Illustrative quote |

|---|---|

| HIV being associated with immorality or sexual promiscuity | . . . many of them think [HIV] infects immoral people; if you are one of the victims, you are seen as immoral. There is a way in which you misbehaved and became infected. “Caregiver, not disclosed”a |

| HIV as a fatal disease | The first impression people got about HIV is that it kills, and it has never been reversed. Many people know that, for HIV victims, their days are numbered. “Caregiver, not disclosed” |

| Many children don’t like telling other people their HIV status because people say HIV kills, so one is isolated. Playing with other children is a problem; you stay alone and become stressed. I was told having HIV is the end of your life. “Child”b | |

| Stigma and discrimination from community | In our place, they say the one with HIV should not interact with other children or sleep with others. He or she should sleep alone. “Child” |

| Negative experiences with religious institutions | When the pastor came to preach, instead of encouraging her or even giving her hope, he condemned her, saying she misbehaved and that [HIV] was her punishment. “Caregiver, not disclosed” |

| There are some [pastors] who rebuke and talk about you. They don’t care about you, but only about their status. “Child” | |

| Positive experiences with religious institutions | If [the pastor] knows one is HIV positive, they encourage people to love them and not isolate them. Initially, pastors could isolate a person, and say ‘so and so should not sit in front but [should] sit in the back.’ . . . [Now] they are so loving and the victims feel accepted. “Caregiver, not disclosed” |

| Sometimes you are called and prayed for in front of the congregation. The pastor doesn’t disclose but says the spirit of God has directed him to pray for your healing. They also love and assist you if you come from a poor family. “Child” | |

| Child learning about HIV in school | This disease is even taught at school so [the children] know a lot of things in regard to this disease. The way [the child] asks questions about his disease, you realize that they have known this disease . . . Even those 10 years-old, they know about HIV. “Caregiver, disclosed” |

| HIV in school as a barrier to disclosure | I always think about it and conclude they are taught about HIV in school. They might be told and he/she thinks he/she is not one of them . . . So the day you will disclose that he/she is one of the people infected with HIV . . . yet they have been told the dangers of having HIV, you will have stressed him “Caregiver, Not disclosed” |

| HIV in school as a facilitator of disclosure | But me, I was the first one to tell the child. The doctor told me that I should just start by asking those questions they learn from school like, ‘What is HIV?’, ‘How is it transmitted?’ Just start with those. Then from there you can gradually disclose to the child. “Caregiver, disclosed” |

| HIV in the media (e.g. radio, TV, newspapers) | For me, there was a time [a TV program] featured ARVs and my son was watching. He became curious and asked me, ‘Are those not the drugs I am taking? Does it mean that I am sick?’ Even though I tried to change the channel, I realized he was stressed and wanted to find out more. It was aired for four consecutive days in the evenings and he was always watching. It really affected him. “Caregiver, disclosed” |

Denotes caregiver disclosure status: not disclosed – the caregiver had not disclosed to any of their children; disclosed – the caregiver had disclosed to one or more of their children.

All child participants in this study were disclosed to – i.e., knew their HIV status.

Caregivers and children described the church – an important community institution in this setting [18] – as both a potential source of financial and emotional support, and one of stigma and discrimination. Caregivers and children gave examples of pastors preaching stigmatizing or discriminatory beliefs about HIV and HIV-infected people, often related to religious views condemning sexual immorality. A number of caregivers and children also shared stories of pastors who disclosed the HIV status of church members in front of others to shame or make an example of them. Caregivers also pointed to the child’s school as an institution that shaped decisions around disclosure. Like the church, individuals at schools, including teachers and other children, could be both important supporters and sources of stigma towards children with HIV. Many caregivers felt comfortable and decided to disclose the child’s HIV status to teachers and others at school, often to explain a child’s frequent absences for medical appointments. In contrast, the school environment was considered risky because a child might disclose his or her status to other children and face ridicule and discrimination by peers. The children’s perspectives and experiences validated caregivers’ concerns; although there were reports of significant instances of support, both by teachers and peers, there were also many descriptions of discrimination and stigma leading to teasing, ridicule, and isolation at school. One child described when peers found out about his HIV status, ‘Now it has happened. They have all run away from me . . . who am I going to share this with? Who will I call a friend?’

Finally, caregivers who had not disclosed discussed mass media campaigns about HIV as both a facilitator and barrier to disclosure. In one way, caregivers felt that media could be a valuable source of information about HIVand preempt discussions about the child’s status. Alternatively, HIV in the media also led to caregivers to feel unsure of what their children knew about HIVand their own status, and many suspected that their child had started ‘putting the pieces together’ with references to HIV on television programs, radio commercials, and billboards. In contrast to the caregivers’ concern about these messages, knowledge about HIV through media outlets was not a prominent theme in the child FGDs.

Discussion

In this setting in western Kenya, caregivers of HIV-infected children described the process of disclosure of HIV status to children as critically shaped by their social environment. Social actors at varying domains of proximity or intimacy to the caregiver and child impacted all aspects of disclosure, including reasons for and against disclosure, fears about disclosure and the potential consequences of disclosure, and when and how to disclose to the children. The prevailing beliefs of these social actors critically determined whether child HIV disclosure was supported or feared. To understand disclosure of HIV status to children in this setting, it is thus essential to understand the specific cultural and environmental contexts of disclosure. Disclosure is not an insular process that takes place between a caregiver and a child, but few studies have examined how individuals outside the caregiver–child domain shape disclosure. Our study provides highly contextual and rich preliminary data for better understanding the social forces that impact disclosure in this setting, which we hope will lead to more informed and effective support systems for children learning their HIV status.

The most pervasive theme across domains that was highlighted by caregivers in this setting was HIV stigma and discrimination. While caregivers described different types of stigma at the various domains, the risk of stigma was consistently cited as one of the biggest barriers to disclosure, which is consistent with the literature on disclosure of HIV status to children [5,6]. Both caregivers who had and had not disclosed shared similar fears about HIV stigma, but caregivers who had not disclosed seemed to consistently express greater fears about the potential negative impacts of disclosure due to HIV stigma. To us, this suggests that at least some of the fears that caregivers have about disclosure do not materialize once the child knows his or her status and that caregivers who have not disclosed may benefit from learning about the experiences of caregivers who have disclosed. The effects of stigma and discrimination were also prevalent within the child FDGs, although children were less likely to connect the stigma to explicit community-level beliefs like immorality and promiscuity. For example, children expressed the feeling of shame when taking medication in front of other people, but did not articulate the source or reason for this feeling. While studies have reviewed the efficacy of community-level stigma reduction interventions and reported moderate successes [19,20], we are not aware of any studies that have evaluated the impact of these interventions on disclosure of HIV status to children. Changing negative community-level beliefs about HIV is critical to mitigating caregivers’ fears about the potential for discrimination with disclosure of HIV to the child, and creating a supportive and conducive environment for disclosure.

Whereas there have been a multitude of studies describing low rates of disclosure among HIV-infected children, particularly in resource-limited settings, there have been few studies evaluating disclosure protocols and interventions [5,6]. This study provides novel evidence for the design of potential interventions to improve disclosure to children. Intervention components should consider whether to involve those beyond the immediate actors of disclosure (i.e. caregiver, child, and perhaps healthcare practitioner), and should incorporate community-level components to address major barriers to disclosure. For example, more communication between caregivers and teachers about what their child has learned about HIV in the classroom might better prepare caregivers for disclosure and help them feel more confident in discussing pertinent information related to HIV. In addition, given the positive and negative roles played by the church in this setting – as expressed by caregivers, children, and noted elsewhere [18] – healthcare institutions may partner with church leaders to provide additional emotional and physical support systems for HIV-infected children and their caregivers. Clinics should also work independently to provide additional services. Support groups for caregivers who have and have not disclosed could facilitate discussions around disclosure of HIV status to children, shared experiences of disclosure, and strategies for addressing common barriers or fears of disclosure. Likewise, given the value HIV-infected children place on their peer’s opinions, peer groups for children would likely be a valuable intervention addressing the postdisclosure psychological and social well being of the child.

The present study has a number of limitations for consideration. First, this study on the social environment for disclosure relies on contextual data and the lived experiences of caregivers in a relatively small area of Kenya. Thus, these results may not be generalizable to other regions of sub-Saharan Africa or other resource-limited settings. Second, we relied on a convenience sample of caregivers and HIV-infected children, which may also limit generalizability, though it is not atypical for qualitative inquiry. Certain aspects of the study population, however, were more heterogeneous; we included both biological and nonbiological caregivers, caregivers who had and had not disclosed HIV status to their child, a wide range of age of caregivers, and caregivers from urban and more rural settings. In addition, we had good thematic saturation. The study included mostly women in the FGDs, as this reflects the population providing the majority of child care for HIV-infected children in Kenya [21].

Caregivers and children described a complex and difficult social environment for disclosure of HIV status. This study has implications for clinical systems in terms of the design and implementation of counseling and other support services for HIV disclosure to children and for larger community HIV education and antistigma campaigns to reduce caregiver fears about the potential negative consequences of disclosure. Creating a safer and more supportive environment for child HIV disclosure is critical in this setting as children transition into adolescence and young adulthood when knowing about their HIV status and disease management is essential.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to recognize the efforts of Eunice Walumbe for organizing and facilitating the focus group discussions. We would like to most of thank the participants of focus group discussions for their time and expertise. The principal contributions of each of the authors of this manuscript are as follows: R.V. as primary author led the study design, analysis, and interpretation of data, and contributed significantly to the drafting and revision of the manuscript; M.S. contributed significantly to the analysis and interpretation of data and led the drafting and revision of the manuscript; T.I. contributed to the study design, interpretation of data, and revision of the manuscript; C.Mc.A., L.F., and M.Mc.H. contributed significantly to the analysis and interpretation of data, and contributed to the drafting and revision of the manuscript; I.M. and W.N. co-led the study design and contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data, and to the revisions of the manuscript.

Funding source: This research was supported in part by a grant entitled ‘Patient-Centered Disclosure Intervention for HIV-Infected Children’ (1R01MH099747-01) to Drs Rachel Vreeman and Winstone Nyandiko from the National Institute for Mental Health, Bethesda, MD, USA.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

Disclosure: The authors have no financial relationships or other conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the view of the Indiana University School of Medicine or the Moi University School of Medicine. The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose. The primary author had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Global HIV/AIDS response: epidemic update and health sector progress towards universal access: Progress Report 2011. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.UNAIDS. The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) 2010. 2010 Report on the global AIDS epidemic. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wiener L, Mellins CA, Marhefka S, Battles HB. Disclosure of an HIV diagnosis to children: history, current research, and future directions. J Develop Behav Pediatr. 2007;28:155–166. doi: 10.1097/01.DBP.0000267570.87564.cd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Disclosure of illness status to children and adolescents with HIV infection. American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Pediatrics AIDS. Pediatrics. 1999;103:164–166. doi: 10.1542/peds.103.1.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vreeman RC, Gramelspacher AM, Gisore PO, Scanlon ML, Nyandiko WM. Disclosure of HIV status to children in resource-limited settings: a systematic review. J Int AIDS Soc. 2013;16:18466. doi: 10.7448/IAS.16.1.18466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pinzon-Iregui MC, Beck-Sague CM, Malow RM. Disclosure of their HIV status to infected children: a review of the literature. J Trop Pediatr. 2013;59:84–89. doi: 10.1093/tropej/fms052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bhattacharya M, Dubey AP, Sharma M. Patterns of diagnosis disclosure and its correlates in HIV-infected North Indian children. J Trop Pediatr. 2010;57:405–411. doi: 10.1093/tropej/fmq115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Biadgilign S, Deribew A, Amberbir A, Escudero HR, Deribe K. Factors associated with HIV/AIDS diagnostic disclosure to HIV infected children receiving HAART: a multicenter study in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2011;6:e17572. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oberdorfer P, Puthanakit T, Louthrenoo O, Charnsil C, Siri-santhana V, Sirisanthana T. Disclosure of HIV/AIDS diagnosis to HIV-infected children in Thailand. J Paediatr Child Health. 2006;42:283–288. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2006.00855.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown BJ, Oladokun RE, Osinusi K, Ochigbo S, Adewole IF, Kanki P. Disclosure of HIV status to infected children in a Nigerian HIV Care Programme. AIDS Care. 2011;23:1053–1058. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2011.554523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vreeman RC, Nyandiko WM, Ayaya SO, Walumbe EG, Marrero DG, Inui TS. The perceived impact of disclosure of pediatric HIV status on pediatric antiretroviral therapy adherence, child well being, and social relationships in a resource-limited setting. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2010;24:639–649. doi: 10.1089/apc.2010.0079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boon-Yasidhi V, Kottapat U, Durier Y, Plipat N, Phongsamart W, Chokephaibulkit K, et al. Diagnosis disclosure in HIV-infected Thai children. J Med Assoc Thai. 2005;88(Suppl 8):S100–S105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Einterz RM, Kimaiyo S, Mengech HN, Khwa-Otsyula BO, Esamai F, Quigley F, et al. Responding to the HIV pandemic: the power of an academic medical partnership. Acad Med. 2007;82:812–818. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3180cc29f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Inui TS, Nyandiko WM, Kimaiyo SN, Frankel RM, Muriuki T, Mamlin JJ, et al. AMPATH: living proof that no one has to die from HIV. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:1745–1750. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0437-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Glaser B, Strauss A. The discovery of grounded theory: strategies for qualitative research. New York: Aldine Publishing Company; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research: grounded theory procedures and techniques. Newbury Park, CA: SAGE Publications; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bronfenbrenner U. International encyclopedia of education. 2. Oxford: Elsevier; 1994. Ecological models of human development. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Campbell C, Skovdal M, Gibbs A. Creating social spaces to tackle AIDS-related stigma: reviewing the role of church groups in Sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS Behav. 2011;15:1204–1219. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9766-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brown L, Macintyre K, Trujillo L. Interventions to reduce HIV/AIDS stigma: what have we learned? AIDS Educ Prev. 2003;15:49–69. doi: 10.1521/aeap.15.1.49.23844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mahajan AP, Sayles JN, Patel VA, Remien RH, Sawires SR, Ortiz DJ, et al. Stigma in the HIV/AIDS epidemic: a review of the literature and recommendations for the way forward. AIDS. 2008;22(Suppl 2):S67–S79. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000327438.13291.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Monasch R, Boerma JT. Orphanhood and childcare patterns in sub-Saharan Africa: an analysis of national surveys from 40 countries. AIDS. 2004;18(Suppl 2):S55–65. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200406002-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]