Abstract

The Schizosaccharomyces pombe dim1+ gene is required for entry into mitosis and for chromosome segregation during mitosis. To further understand dim1p function, we undertook a synthetic lethal screen with the temperature-sensitive dim1-35 mutant and isolated lid (for lethal in dim1-35) mutants. Here, we describe the temperature-sensitive lid1-6 mutant. At the restrictive temperature of 36°C, lid1-6 mutant cells arrest with a “cut” phenotype similar to that of cut4 and cut9 mutants. An epitope-tagged version of lid1p is a component of a multiprotein ∼20S complex; the presence of lid1p in this complex depends upon functional cut9+. lid1p-myc coimmunoprecipitates with several other proteins, including cut9p and nuc2p, and the presence of cut9p in a 20S complex depends upon the activity of lid1+. Further, lid1+ function is required for the multiubiquitination of cut2p, an anaphase-promoting complex or cyclosome (APC/C) target. Thus, lid1p is a component of the S. pombe APC/C. In dim1 mutants, the abundances of lid1p and the APC/C complex decline significantly, and the ubiquitination of an APC/C target is abolished. These data suggest that at least one role of dim1p is to maintain or establish the steady-state level of the APC/C.

The cdc2 protein serine/threonine kinase plays a key role in promoting cell cycle progression in all eukaryotes (reviewed in references 30, 34, and 37). At the G2/M transition, cells enter mitosis as a result of cdc2p activation, which in turn is dependent upon the association of cdc2p with its positive regulatory partner, cyclin B. The timed destruction of cyclin B at the end of mitosis is one mechanism ensuring that cdc2p-cyclin B is inactivated in each cell cycle.

Indeed, the abrupt disappearance of cyclin observed at the end of each cell cycle in fertilized sea urchin eggs first suggested the possibility that cyclin destruction may be important for cell cycle progression (10). The fact that nondegradable forms of cyclin B injected into frog egg cycling extracts prevented exit from mitosis further strengthened this hypothesis (35). It has recently been demonstrated that although cyclin B is normally degraded during mitosis in all eukaryotes to promote exit from mitosis (reviewed in references 8, 17, and 26), at least in budding yeast, the destruction of Clb2p, the major mitotic cyclin, is not absolutely required for cell cycle progression (42, 45).

Destruction of cyclins at mitosis occurs via ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis (14), a multistep process in which a ubiquitin-activating enzyme (E1) first activates ubiquitin by formation of a high-energy thioester bond. E1 then transfers ubiquitin to an E2 or ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme. The E2 may transfer ubiquitin directly to the substrate, targeting the substrate for destruction by the 26S proteasome. Alternatively, the specificity of this reaction may be determined by association of the E2 with a ubiquitin protein ligase (E3) to catalyze ubiquitination of a target protein (reviewed in references 7 and 19).

An E3 ubiquitin ligase that recognizes A- and B-type cyclins was identified biochemically in clam and frog extracts and genetically in fission and budding yeasts and is known as the anaphase-promoting complex or cyclosome (APC/C) (reviewed in references 8, 17, 26, and 44). The APC/C is a multisubunit complex of ∼20S that has been conserved throughout evolution (reviewed in references 8, 17, 26, and 44). In Xenopus egg extracts, eight components of the APC have been identified (27, 36), and the sequences of their human homologs have been reported (50). In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, 10 APC components have been identified (22, 23, 29, 51–53). In Schizosaccharomyces pombe, only four APC components have been identified to date: cut4p (49), cut9p (40, 47), nuc2p (18, 28), and hcn1p (47). cut4p, cut9p, and nuc2p are orthologs of S. cerevisiae Apc1p, Cdc16p, and Cdc27p and of human APC1, APC6, and APC3, respectively. hcn1p is related to S. cerevisiae Cdc26p and is apparently important for APC/C activity only at elevated temperatures (47). The cut4, cut9, and nuc2 gene products interact physically, forming part of an ∼20S complex (47, 49). Temperature-sensitive cut4 and cut9 mutants all display a “cut” phenotype at restrictive temperatures; in these mutants, chromosome segregation and spindle elongation fail to occur, such that subsequent cytokinesis bisects the nucleus or results in segregation of DNA to only one daughter cell (40, 49).

The APC/C targets proteins containing a destruction box motif for ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis during mitosis and G1 phases. While M phase cyclins were the first targets known, other APC/C target proteins have subsequently been identified. Anaphase chromosome segregation in the budding yeast S. cerevisiae requires APC/C-mediated destruction of the nuclear protein Pds1 (9, 48), and in the fission yeast S. pombe, chromosome segregation requires destruction of cut2p (12). Additional substrates of the APC/C include the spindle component Ase1p (24), cohesins (32), the Cdc5p “polo” kinase (6, 43), and Cdc20p (43). In the absence of APC/C activity, spindle elongation, chromosome segregation, and exit from mitosis are blocked.

Like components of the APC/C, dim1p also is required during mitosis for chromosome segregation (5). dim1p is a highly conserved 17-kDa protein whose biochemical function is unknown. In S. cerevisiae, the ortholog of dim1+ was originally called CDH1 (5), but the name has been changed to DIB1. In an effort to further elucidate dim1+ function, we undertook a synthetic lethal screen with the temperature-sensitive dim1-35 mutant and isolated lid (for lethal in dim1-35) mutants. Here, we describe the temperature-sensitive lid1-6 mutant. At the restrictive temperature of 36°C, lid1-6 mutant cells arrest with a cut phenotype similar to that of cut4 and cut9 mutants. An epitope-tagged version of lid1p (lid1p-myc) is present in a high-molecular-weight complex of ∼20S, and the presence of lid1p in this complex depends upon functional cut9p. Coimmunoprecipitation analyses demonstrate an in vivo association among lid1p-myc and several other proteins, including cut9p and nuc2p, and the presence of cut9p in a 20S complex depends upon the activity of lid1p. Further, the multiubiquitination of cut2p depends upon lid1+ function. Thus, lid1p is a component of the S. pombe APC/C. To explain the genetic interaction between dim1 and lid1 mutants, we have found that the abundances of lid1p and the 20S APC/C complex are dependent upon dim1+ function. Moreover, dim1 function is required for APC/C-mediated multiubiquitination of cut2p. These data indicate that one role of dim1p in mitosis is to establish or maintain the integrity and function of the APC/C.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast methods, strains, and media.

The S. pombe strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. Strains were grown in yeast extract (YE) medium or minimal medium with appropriate supplements (33). Crosses were performed on malt extract medium (33) or glutamate medium (minimal medium lacking ammonium chloride and containing 0.01 M glutamate, pH 5.6). Random spore analysis and tetrad analysis were performed as described previously (33). Double-mutant strains were constructed and identified by tetrad analysis. Unless otherwise indicated, transformations were performed by electroporation (38). Genomic DNA was isolated as described previously (20, 33).

TABLE 1.

S. pombe strains used in this study

| Strain | Genotype | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| KGY28 | h− 972 | P. Nurse |

| KGY42 | h+ cdc25-22 | P. Nurse |

| KGY69 | h+ 975 | P. Nurse |

| KGY396 | h+ dim1-35 leu1-32 | 5 |

| KGY656 | h− cdc10-V50 leu1-32 | P. Nurse |

| KGY864 | h− nuc2-663 | P. Nurse |

| KGY1150 | h− lid1-6 ura4-D18 leu1-32 ade6-M210 | This study |

| KGY1162 | h− lid1-6 dim1-35 leu1-32 | This study |

| KGY1164 | h− cut9-665 leu1-32 | R. McIntosh |

| KGY1166 | h− lid1-6 | This study |

| KGY1177 | h− lid1-6 cut9-665 leu1-32 ade6-M216 | This study |

| KGY1180 | h+ dim1::his3+ leu1-32::p980 his3-D1 ura4-D18 ade6-M210 | 5 |

| KGY1186 | h− cut4-533 leu1-32 | R. McIntosh |

| KGY1192 | h+ lid1-6 cut4-533 | This study |

| KGY1203 | h− lid1-6 leu1-32::pKG1025 ura4-D18 ade6-M210 | This study |

| KGY1302 | h+ lid1::lid1-myc/Kanr | This study |

| KGY1305 | h− lid1::lid1-myc/Kanrdim1-35 | This study |

| KGY1335 | h+/h− lid1+/lid1::ura4+ ura4-D18/ura4-D18 leu1-32/leu1-32 ade6-M210/ade6-M216 | This study |

| KGY1336 | h− lid1::lid1-myc/Kanrura4-D18 leu1-32 ade6-M210 | This study |

| KGY1365 | h+ cut9::cut9-HA/Kanr | This study |

| KGY1366 | h− lid1::lid1-myc/Kanrcut9::cut9-HA/Kanr | This study |

| KGY1402 | h− cdc10-V50 lid1-6 | This study |

| KGY1404 | h− lid1::lid1-myc/Kanrcut9-665 | This study |

| KGY1462 | h− cut9::cut9-HA/Kanrlid1-6 | This study |

| KGY1561 | h− dim1::his3+ leu1-32::p980 his3-D1 ura4-D18 ade6-M210 lid1::lid1-myc/Kanr | This study |

| KGY1739 | h− dim1-35 cut9::cut9-HA/Kanr | This study |

| KGY1570 | h− cut2::cut2-myc Kanr | This study |

| KGY1571 | h+ cut2::cut2-myc Kanr | This study |

| KGY574 | h− mts3-1 leu1-32 | C. Gordon |

| KGY1923 | h− mts3-1 cut2::cut2-myc Kanrleu1-32 | This study |

| KGY948 | h− mts3-1 lid1-6 cut2::cut2-myc leu1-32 ura4-D18 | This study |

| KGY2035 | h− mts3-1 dim1-35 cut2::cut2-myc leu1-32 ura4-D18 | This study |

Plasmids and molecular biological techniques.

All plasmid manipulations and bacterial transformations were by standard techniques (39). Essential features of plasmid construction are described below. All sequencing of plasmid DNA was performed by using Sequenase 2.0 (U.S. Biochemicals, Cleveland, Ohio) or Thermo Sequenase (Amersham Life Sciences, Cleveland, Ohio) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Unless otherwise specified, all PCRs were performed by using Taq DNA polymerase and the GeneAmp PCR reagent kit (Perkin-Elmer) in a PTC-100 Programmable Thermal Controller (MJ Research, Watertown, Mass.) programmed as follows: 94°C for 1 min, 50°C for 2 min, and 72°C for 2 min (40 cycles) and 72°C for 10 min. All [32P]dCTP-labeled probes for radioactive hybridization were labeled by using redivue [32P]dCTP (Amersham Life Sciences, Amersham, England) and the rediprime random primer labeling kit (Amersham Life Sciences) according to manufacturer’s instructions.

dim1-35 synthetic lethal screen (lid screen).

A dim1-35 strain carrying plasmid-borne mouse dim1 (mdim1) under control of the nmt1 promoter, pKG930 (5), was mutagenized with nitrosoguanidine as described previously (33). Approximately 85,000 mutagenized cells were plated at a density of 300 to 500 cells per plate on medium lacking thiamine in order to induce expression of mdim1. Plates were incubated at 25°C until colonies formed. Colonies were replica plated to medium containing thiamine in order to eliminate mdim1 activity. We used mdim1 for this screen because S. pombe dim1 activity under control of the nmt1 promoter was not effectively eliminated by the inclusion of thiamine in the medium, whereas mdim1 activity clearly was. Plates were incubated overnight at 25°C and then re-replica plated to medium containing thiamine. Plates were screened 2 days later for colonies that were inviable in the presence of thiamine.

Physiological experiments.

For analysis of synchronous cell populations, 4 liters of cells was grown to mid-log phase (8 × 106 cells/ml) at the permissive temperature (25°C) in YE medium. Cells were separated on the basis of size by centrifugal elutriation in a Beckman JE 5.0 elutriator rotor. Cells synchronized in early G2 (the smallest cells in the population) were collected and inoculated into YE medium at 25 or 36°C. Synchrony was monitored at 20- to 25-min intervals by scoring 100 cells for the presence of a septum.

Flow cytometry and microscopy.

For flow cytometric analysis, cells were fixed in ice-cold 70% ethanol, washed in 50 mM sodium citrate, incubated with 0.1 mg of RNase A per ml in 50 mM sodium citrate for 2 h at 37°C, and then stained with 1 μM Sytox green in 50 mM sodium citrate for 1 h. Cells were sonicated and analyzed by flow cytometry as described previously (41). All fluorescence microscopy was performed on a Zeiss Axioskop with appropriate filters. In order to visualize DNA, ethanol-fixed cells were washed in phosphate-buffered saline and then stained with the fluorescent DNA-binding dye DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) at 1 μg/ml. For immunofluorescence, cells were fixed in 70% ethanol at 4°C, or in 100% methanol at −20°C, for 8 min and then washed with phosphate-buffered saline and processed as described previously (2). For staining of microtubules, fixed cells were incubated in a 1:10 dilution of the monoclonal TAT-1 primary antibody (46) (a generous gift of K. Gull) followed by a 1:100 dilution of Texas red-conjugated goat antimouse secondary antibody (Molecular Probes, Eugene, Oreg.).

Cloning and sequence analysis of lid1.

lid1-6 mutant cells (KGY1150) transformed with a pUR19-based S. pombe genomic library (3) were selected at 25°C on medium lacking uracil and then replica plated to 36°C. Plasmids subsequently shown to be identical by restriction digestion and Southern blot analysis were recovered from two independent Lid1+ Ura+ colonies. Deletion constructs generated from the rescuing plasmid (pKG1030) were retransformed into lid1-6 cells in order to identify a minimal rescuing fragment. Sequencing of pKG1030 revealed that a portion of the insert was contained within c19g12 (21), a cosmid sequenced as part of the S. pombe genome sequencing project. The remainder of the insert was sequenced and, in combination with sequence obtained from c19g12, analyzed for coding potential.

For integration mapping, the complete 5.5-kb pKG1030 insert was subcloned into the S. pombe ura4-based integrating vector pJK210 (25) to generate pKG1025. pKG1025 was linearized at the unique SacI site within the insert, and the linearized plasmid was transformed into the lid1-6 ura4-D18 mutant strain KGY1150. Transformants were selected on medium lacking uracil. Lid1+ Ura+ transformants were picked and outcrossed to either lid1+ or lid1-6 strains in order to verify cosegregation of the lid1+ phenotype with the ura4+ marker.

Isolation of lid1 cDNAs.

An S. pombe cDNA library constructed in the vector pDB20 (11) was transformed into Escherichia coli and plated on Luria-Bertani agar containing 50 μg of ampicillin per ml. Approximately 106 transformants were plated. Colonies were allowed to form overnight at 36°C and then lifted onto Hybond-N nylon membranes (Amersham Life Sciences) and processed for radioactive hybridization according to manufacturer’s instructions. Membranes were prehybridized in 5× Denhardt’s solution–0.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)–5× SSPE (1× SSPE is 0.18 M NaCl, 10 mM NaH2PO4, and 1 mM EDTA [pH 7.7])–100 μg of hydrolyzed yeast RNA per ml at 65°C and then hybridized overnight in the same buffer. Two different templates were utilized in order to generate [32P]dCTP-labeled probes: a 1.5-kb lid1+ EcoRI fragment (used to isolate clone pKG1074) and a 0.5-kb 5′ lid1+ SacI/XhoI fragment (used to isolate pKG1142). The isolated plasmids were sequenced by using gene-specific oligonucleotide primers.

Deletion of lid1 from the genome.

In order to generate a lid1 deletion construct containing lid1+ 5′ and 3′ flanks, an ∼4-kb lid1+ genomic fragment (BglII/BstXI) was subcloned from pKG1030 into pBS-SK+ (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.) to generate pKG1186. A portion of the lid1 coding region (XhoI/EcoRV) was excised from pKG1186 and replaced with a 1.8-kb fragment containing the ura4+ gene, to generate pKG1191. A SacI/Acc651 fragment consisting of lid1 5′ flank::ura4+::lid1 3′ flank was isolated from pKG1191 and transformed into a diploid strain (h+/h− ura4-D18/ura4-D18 leu1-32/leu1-32 ade6-M210/ade6-M216). Ura+ transformants were selected on medium lacking uracil. Uracil prototrophs were isolated, and genomic DNA was prepared and digested with BglII and HindIII. Digests were separated by agarose gel electrophoresis, blotted to membranes, and hybridized with an [α-32P]dCTP-labeled 1-kb BglII/XhoI fragment of lid11 5′ flank, in order to verify replacement of one allele of lid1 with the ura4+ cassette in the Ura+ diploids. Diploids were allowed to sporulate, and tetrads were dissected in order to analyze the lid1::ura4+ phenotype.

Epitope tagging of lid1p.

A genomic version of lid1 encoding nine copies of the myc epitope fused to the C terminus of lid1 was generated by the method described previously (1). In brief, the oligonucleotide primers lid1tag1 (5′ CCT GTA TCT AGA TGC CAC TTT GGC-3′) and lid1tag3 (5′-GGG GAT CCG TCG ACC TGC AGC GTA CGA AAA AGA GAA TAA ACG ATA TCT CG-3′) were synthesized in order to PCR amplify a 400-bp lid1 genomic fragment upstream of the putative lid1 stop codon, and the primers lid1tag2 (5′-TTA TAT ATA AGG TAC CTT GAT TC-3′) and lid1tag4 (GTT TAA ACG AGC TCG AAT TCA TCG ATA TGA GCT TAT GTT TAA TGG TCG-3′) were synthesized in order to PCR amplify lid1 genomic sequence downstream of the putative lid1 stop codon, using the thermostable DNA polymerase Pfu (Stratagene) according to the manufacturer’s instructions in a PTC-100 Programmable Thermal Controller (MJ Research) programmed as follows: 95°C for 1 min, 56°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 3 min (40 cycles); 94°C for 1 min; 56°C for 2 min; and 72°C for 10 min. PCR fragments were agarose gel purified by using the QIAquick Gel Extraction System (QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Approximately 100 ng of each fragment was used in a second PCR, with a mixture containing 1 μM each lid1tag1 and lid1tag2 and 200 ng of pKG1198 (encoding the 9xMyc-Kan tag; the 9xMyc cassette was a generous gift of K. Nasmyth, and pKG1198 was constructed by W. H. McDonald) and utilizing the Taq Plus Precision System (Stratagene) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, in a PTC-100 Programmable Thermal Controller (MJ Research) programmed as follows: 95°C for 1 min; 95°C for 1 min, 62°C for 1 min (with an increase of 1°C/cycle), and 72°C for 5 min (15 cycles); 95°C for 1 min, 50°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 5 min (30 cycles); and 72°C for 10 min. The amplification product was agarose gel purified and transformed into diploid cells (h+/h− ura4-D18/ura4-D18 leu1-32/leu1-32 ade6-M210/ade6-M216) by the lithium acetate method, as described previously (25). Transformants were plated on YE agar, allowed to recover overnight at 32°C, and then replica plated to YE agar containing 25 μg of G418 per ml. G418-resistant (G418r) diploids were picked and allowed to sporulate. Tetrads were dissected and analyzed for segregation of the G418r marker. G418r colonies derived from tetrads which segregated 2 G418r:2 G418s progeny were picked and further analyzed. Genomic DNA was prepared and digested with SalI and NdeI. Digests were separated by agarose gel electrophoresis, blotted to membranes, and hybridized with an [α-32P]dCTP-labeled 600-bp HindIII lid1 fragment, in order to verify integration of the lid1 tag at the lid1 genomic locus in G418r colonies. Protein lysates were prepared as described previously (16) and subjected to immunoprecipitation by consecutive incubation with (i) the monoclonal anti-Myc antibody 9E10 (2 μg/ml), (ii) rabbit anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibody (Organon Teknika Corp., West Chester, Pa.), and (iii) protein A-Sepharose (Pharmacia Biotech). Immunoprecipitates were washed extensively with Nonidet P-40 (NP-40) buffer. Lysates and immunoprecipitates were resolved on SDS–6 to 20% polyacrylamide gradient gels and then transferred to Immobilon-P (Millipore, Bedford, Mass.). For detection of lid1p-myc, the blot was incubated consecutively with 9E10 (2 μg/ml), peroxidase-conjugated sheep anti-mouse IgG (1:3,000; Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.), and enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) detection reagents (Amersham Life Sciences), followed by chemiluminescence detection with Reflection NEF-596 autoradiography film (NEN Life Science Products).

Epitope tagging of cut9p.

Epitope tagging of Cut9 was performed as described above for epitope tagging of lid1, using the 5′ flank oligonucleotide primers cut9tag1 (5′-GAT GCC CTT AAC CAA GGG-3′) and cut9tag2 (5′-GGG GAT CCG TCG ACC TGC AGC GTA CGA TCG TTG CTC TGA GAC ATT ACC TTC-3′) and the 3′ flank oligonucleotide primers cut9tag3 (5′-GTT TAA ACG AGC TCG AAT TCA TCG ATA TTG CGA AAT TCT ATT AAT TCT TG-3′) and cut9tag4 (5′-GAA TTC TGC CGC TTC TAT G-3′). The second PCR was performed with pKG1155 (encoding the 3xHA-Kan tag; a generous gift of J. Bahler and J. Pringle) as the template. The purified amplification product was transformed directly into haploid wild-type cells (KGY28). G418r colonies were picked and analyzed. Genomic DNA was prepared and digested with BamHI. Digests were separated by agarose gel electrophoresis, blotted to membranes, and then probed with the cut9 5′ flank PCR fragment to verify integration of the 3xHA-Kan construct at the cut9 locus. Protein lysates were prepared as described above and subjected to immunoprecipitation by consecutive incubation with (i) the monoclonal antihemagglutinin (anti-HA) antibody HA.11 (5 μg/ml; Berkeley Antibody Company, Richmond, Calif.) or the monoclonal anti-HA antibody 12CA5 (5 μg/ml), (ii) rabbit anti-mouse IgG antibody (Organon Teknika Corp.), and (iii) protein A-Sepharose (Pharmacia Biotech). Immunoprecipitates were washed extensively with NP-40 buffer. Lysates and immunoprecipitates were resolved on SDS–6 to 20% polyacrylamide gradient gels and then transferred to Immobilon-P (Millipore). For detection of cut9p-HA, the blot was incubated consecutively with HA.11 or 12CA5 (5 μg/ml), peroxidase-conjugated sheep anti-mouse IgG (1:3,000; Sigma Chemical Co.), and ECL detection reagents (Sigma Chemical Co.), followed by chemiluminescence detection with Reflection NEF-596 autoradiography film (NEN Life Science Products). For quantitation of immunoblotting data, ECL Plus reagents (Amersham Life Science) were used. Data were collected on a Molecular Dynamics Storm instrument and quantified by ImageQuant version 1.1.

Epitope tagging of cut2p.

Epitope tagging of cut2p was performed as described above for epitope tagging of lid1p, using the 5′ flank oligonucleotide primers cut2tag1 (5′-CAC CTG CAT CAG ATT TCC-3′) and cut2tag3 (5′ GTT TAA ACG AGC TCG AAT TCA TCG ATA AAA GAT TAC GAA TTT TCA GGT TTT GTG-3′) and the 3′ flank oligonucleotide primers cut2tag2 (5′-GGG GAT CCG TCG ACC TGC AGC GTA CGA TAA CAA TCC TGT ATC CAA AGA TG-3′) and cut2tag4 (5′-GAA TGT GTG CAT CTG CTG-3′). The second PCR was performed with pKG1262 (encoding 13 copies of the myc epitope; from J. Bahler and J. Pringle) as the template. The purified amplification product was transformed directly into haploid cells (KGY28). G418r colonies were picked and analyzed for the correct integration event by PCR.

In vivo 35S labeling.

Wild-type cells (KGY28) or lid1::lid1-myc cells (KGY1302) were grown to mid-log phase in minimal medium at 32°C. A total of 2 × 108 cells were collected by centrifugation, resuspended in 10 ml of minimal medium containing 1 mCi of Tran35S-label (ICN Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Irvine, Calif.), and then incubated with vigorous shaking at 32°C for 4 h. Cell lysates were prepared, and immunoprecipitation of lid1p-myc was performed as described above. Immunoprecipitates were resolved by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) on 6 to 20% gradient gels. Gels were treated with Amplify (Amersham Life Sciences), dried on a vacuum gel dryer, and exposed to X-ray film at −80°C.

Sucrose gradient analysis.

For sucrose gradient analysis, cells were grown to mid-log phase in YE medium at 32°C. Approximately 2 × 108 cells were collected by centrifugation, and native lysates in NP-40 buffer were prepared as described above. Lysates were layered on 10 to 30% sucrose gradients prepared in NP-40 buffer. Gradients were ultracentrifuged at 30,000 rpm for 21 h in a Beckman SW50.1 rotor. Sedimentation markers were fractionated on gradients prepared and spun in parallel. Fractions were collected, run on SDS–6 to 20% polyacrylamide gradient gels, and then immunoblotted as described above.

Coimmunoprecipitation analysis of lid1p-myc and cut9p-HA.

Native lysates were prepared from KGY1302 (lid1::lid1-myc), KGY1365 (cut9::cut9-HA), or KGY1366 (lid1::lid1-myc cut9::cut9-HA) cells as described above. Denatured lysates were prepared as for native lysates, except that lysed cells were heated to 100°C for 2 min in 300 μl of SDS lysis buffer (10 mM NaPO4 [pH 7.0], 1% SDS, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 1 mM EDTA, 50 mM NaF, 100 μM Na3VO4, 4 μg of leupeptin per ml) prior to extraction with NP-40 buffer. Immunoprecipitations were performed with 9E10 or HA.11 as described above. Immunoprecipitates were resolved by SDS-PAGE, blotted to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes, and probed for lid1p-myc or cut9p-HA as described above.

Ubiquitination assay.

To assay APC/C activity towards cut2p-myc, we followed procedures outlined by Benito et al. (4). The relevant strains were transformed with pREP1-His6-ubiquitin plasmid (a gift from Sergio Moreno). Following growth in the absence of thiamine for 22 h, cells were shifted to the nonpermissive temperature for 4 h and protein lysates were prepared as described previously (4). Briefly, cells were lysed in 8 M urea–100 mM sodium phosphate (pH 8.0)–5 mM imidazole. Cell extracts were clarified by centrifugation for 5 min, and the protein concentration in the supernatants was determined. Six milligrams of extract was mixed with Ni2+-nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni2+-NTA) agarose (Qiagen) and incubated for 4 h at room temperature. The resin was washed exactly as described previously (4). The eluate was diluted in 5× sample buffer and boiled for 5 min, and ubiquitinated forms of cut2p-myc were detected by immunoblotting with 9E10 antibody as described above.

Analysis of protein levels through the cell cycle.

A synchronized population of KGY1366 cells was isolated by centrifugal elutriation and then inoculated into fresh medium at 32°C. Approximately equivalent numbers of cells were collected at 20-min intervals for preparation of whole-cell lysates as described above. Lysates were resolved by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted for cut9p-HA, lid1p-myc, and cdc13p, as described above, and for arp3p as a loading control. Antibodies to arp3p (31) were utilized at a dilution of 1:5,000, and affinity-purified rabbit anti-Cdc13 antibodies (GJG56) were used at a dilution of 1:500. Detection was as described above for lid1p-myc, except that peroxidase-conjugated sheep anti-rabbit IgG (1:10,000; Sigma Chemical Co.) was used as the secondary antibody. cdc2p was detected on immunoblots by incubation with anti-PSTAIRE monoclonal antibody (1:1,000; Sigma Chemical Co.), further incubation with peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (1:50,000; Jackson ImmunoResearch laboratories, Inc.), and then ECL.

RESULTS

Isolation of dim1-interacting genes: the lid screen.

As described previously, the dim1 gene was isolated and shown to encode an evolutionarily conserved protein essential for mitosis (5). In order to investigate further the nature of dim1 function, we wished to identify other proteins with which dim1p interacts in S. pombe cells. We took a genetic approach to this problem, choosing to isolate and characterize second-site mutations synthetically lethal with dim1-35. To accomplish this, a dim1-35 strain carrying pREP1-mdim1 was mutagenized and plated on medium lacking thiamine in order to induce expression of mdim1. Colonies were then replica plated to medium containing thiamine in order to eliminate mdim1 activity. Under these conditions, we expected dim1-35 lid (for lethal in dim1-35) double mutants to be inviable. A total of 85,000 mutagenized colonies were screened; 88 were picked based on inviability in the presence of thiamine. Of these, 26 were outcrossed. Upon outcrossing, four of the mutant strains could not be analyzed due to poor spore viability. Based upon linkage between dim1-35 and the lid mutation in each case, 10 of the remaining 22 strains appeared to contain unconditional loss-of-function alleles of dim1, while 12 contained second-site lid mutations unlinked to the dim1 locus. Of the lid mutants, only the lid1-6 mutant demonstrated a temperature-sensitive phenotype when outcrossed from the dim1-35 mutant. Therefore, we chose to focus our efforts on the analysis of lid1.

dim1-interacting gene lid1.

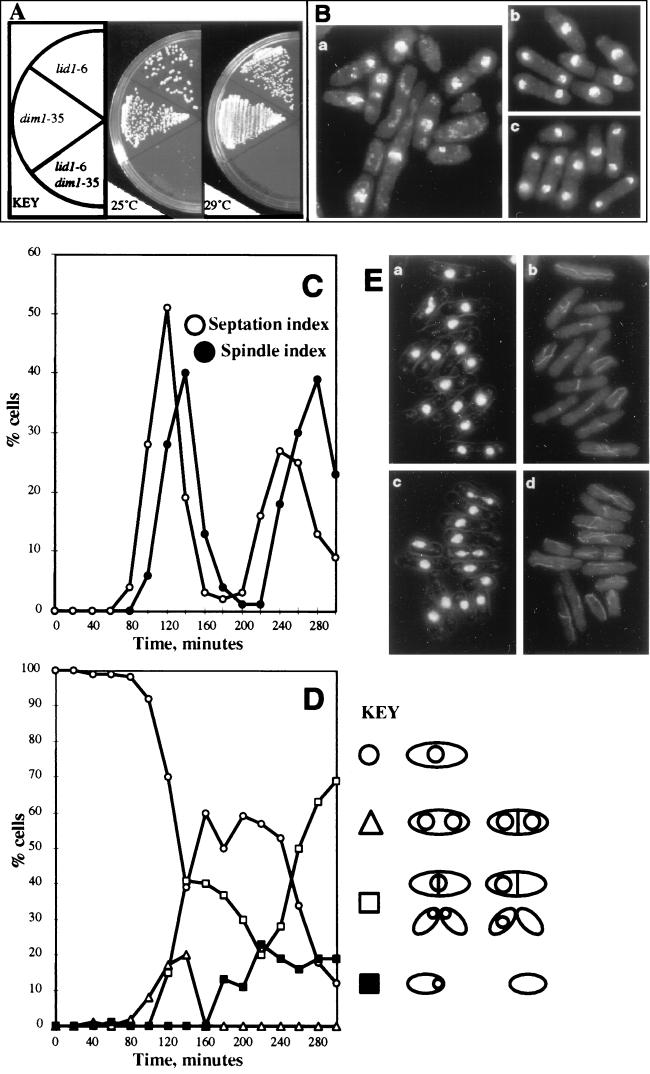

lid1-6 did not display strict synthetic lethality in a dim1-35 background. When the outcrossed lid1-6 mutant was crossed against the dim1-35 mutant, viable lid1-6 dim1-35 double mutants were recovered. The double-mutant cells, however, did display a near-lethal phenotype at either 25 or 29°C, temperatures fully permissive for either lid1-6 or dim1-35 single mutants (Fig. 1A). The double mutant grew extremely slowly and exhibited numerous cytological defects, including cutting and segregation of DNA to only one daughter cell (Fig. 1B, panel a), whereas either lid1-6 or dim1-35 single mutants were phenotypically wild type at these temperatures (Fig. 1B, panels b and c).

FIG. 1.

lid1-6 mutant phenotype. (A) lid1-6 and dim1-35 display a near-lethal synthetic interaction. lid1-6, dim1-35, or lid1-6 dim1-35 cells were streaked to YE agar and then incubated at 25 or 29°C for 3 days. (B) lid1-6 dim1-35 (panel a), lid1-6 (panel b), or dim1-35 (panel c) cells were grown at 25°C, fixed, and stained with DAPI. (C to E) A synchronous population of lid1-6 cells shifted to a restrictive temperature fails to undergo spindle elongation or chromosome segregation at the first mitosis. Subsequent septation results in missegregation of DNA or development of a cut phenotype. Cells were synchronized in early G2 by centrifugal elutriation and then inoculated into rich medium at 36°C. Samples were collected at 20-min intervals and subjected to various analyses. (C) Spindle index and septation index of lid1-6 synchronous cells after the shift. (D) Phenotypes of lid1-6 cells after the shift. Note that at the first mitosis, a small percentage of cells undergo a normal anaphase (▵), as evidenced by normal DNA segregation observed by DAPI staining. In the majority of cells, however, normal anaphase is not observed. Rather, cells cut or missegregate their DNA (■ and □). (E) DAPI (panel a) and tubulin (panel b) staining at 120 min after the shift (corresponding to the first spindle index peak) (note the abundance of short mitotic spindles and the absence of elongated spindles or normally segregated DNA) and DAPI (panel c) and tubulin (panel d) staining at 140 min after the shift (corresponding to the first peak of septation) (note that the majority of septated cells have cut or missegregated their DNA).

As mentioned above, the lid1-6 mutant was unique among the lid mutants in displaying a lethal temperature-sensitive phenotype in a dim1+ background. At the restrictive temperature of 36°C, lid1-6 single-mutant cells arrested with a cut phenotype, similar to that of cut4 and cut9 mutants (40, 49). In order to examine the arrest phenotype caused by lid1-6 more carefully, lid1-6 cells were synchronized in G2 by centrifugal elutriation and then released into rich medium at a restrictive temperature. At the first mitosis, a minority of cells (∼20%) completed mitosis successfully, as judged by antitubulin immunofluorescence and DAPI staining. The majority of cells (∼80%), however, formed short mitotic spindles but failed to elongate the spindle and segregate their DNA. Subsequent septation resulted in development of a cut phenotype or missegregation of DNA to only one daughter cell (Fig. 1C to E). At the second mitosis, all cells exhibited the mutant phenotype. No elongated spindles were observed, and no cells completed mitosis successfully (Fig. 1C and D).

The similarity of the temperature-sensitive arrest phenotype of the lid1-6 mutant to that of cut4 and cut9 mutants suggested the possibility that lid1p, like cut4p and cut9p, might comprise one component of the APC/C. Because genetic interactions often reflect protein-protein interactions, double mutants with lid1 and either cut4, cut9, or nuc2 (encoding a third component of the APC/C) mutations were constructed and analyzed. No genetic interactions between lid1 and cut9 or between lid1 and cut4 were detected. In contrast, the lid1-6 nuc2-663 double mutant exhibited a lowering of restrictive temperature compared to either single mutant alone (data not shown).

Cloning and sequencing of lid1.

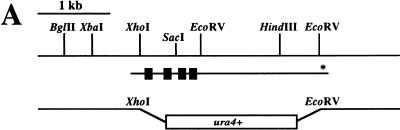

In order to analyze lid1 at a molecular genetic level, the lid1 gene was cloned by complementation of the lid1-6 temperature-sensitive phenotype. After transformation of the lid1-6 mutant with an S. pombe genomic library, two rescuing plasmids, each containing a 5.5-kb insert, were isolated (pKG1030). The isolated plasmids were shown to be identical by restriction mapping and Southern blot analyses. Integration mapping confirmed that the isolated gene contained the lid1 gene and not a high-copy suppressor. Sequencing revealed that a portion of the insert was contained within c19g12, a cosmid located on the short arm of chromosome I (21), which was sequenced as part of the S. pombe genome sequencing project. Sequencing of the remainder of the insert, in combination with the c19g12 sequence, revealed a single large open reading frame (ORF). The minimal rescuing fragment, however, extended beyond this ORF, suggesting that the gene included several smaller upstream ORFs, separated by introns (Fig. 2A). Therefore, a cDNA library was screened in order to isolate a lid1 cDNA. Two independent clones, one a partial cDNA at the 3′ end of the gene, containing the putative stop codon, and one a partial cDNA at the 5′ end of the gene, were isolated. The 5′ clone revealed the existence of four introns. Analysis of the genomic clone revealed an in-frame start codon 124 bp upstream of the first intron. Together, then, the isolated clones comprised an ORF (Fig. 2A) encoding a predicted protein product of 719 amino acids and 82.5 kDa (Fig. 2B). Comparison of the predicted amino acid sequence of lid1p with protein sequences available in the databases revealed no significant homologies or motifs (but see Discussion).

FIG. 2.

Cloning of lid1+. (A) Restriction map of the lid1+ genomic locus. Shown below the restriction map is the lid1+ coding region. ■, intron; *, stop codon. Shown at bottom is the deletion construct. (B) DNA sequence and predicted amino acid sequence of lid1+. Intron sequences are in lowercase letters. *, stop codon.

Deletion of lid1 from the S. pombe genome.

In order to determine whether lid1 is an essential gene in S. pombe, the method of one-step gene disruption was used in order to replace a 3-kb fragment of DNA within the lid1 minimal rescuing fragment with the ura4+ selectable marker in diploid S. pombe cells (see Materials and Methods) (Fig. 2A). Replacement of one allele of lid1 with the ura4+ cassette in Ura+ diploids was confirmed by Southern blot analysis (data not shown). Ura+ diploids were allowed to sporulate, and tetrads were dissected. Thirty-five tetrads segregated 2 inviable:2 viable Ura− progeny. The inviable progeny underwent spore germination, and then two or three residual cell divisions, before arresting as microcolonies of six to eight cells (data not shown). Therefore, lid1 encodes an essential gene in S. pombe.

lid1p-myc associates with several other proteins in vivo.

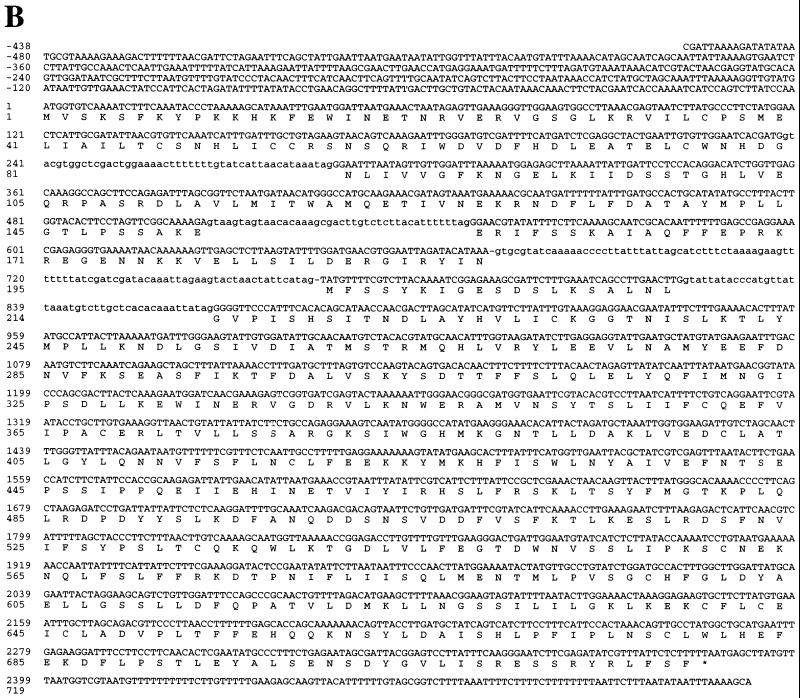

In order to investigate lid1 function at a biochemical level, a DNA fragment encoding nine copies of the myc epitope tag was integrated at the lid1 genomic locus, just upstream of the putative lid1 stop codon (Fig. 2) (see Materials and Methods). The anti-myc monoclonal antibody 9E10 detected a protein which migrated with an apparent molecular mass of ∼100 kDa in lysates and 9E10 immunoprecipitates prepared from the epitope-tagged strain (lid1::lid1-myc; KGY1302) (Fig. 3A). This molecular mass corresponded to that predicted from the addition of the multiple myc epitope tags to the endogenous 82.5-kDa protein. This protein was not detected when lysates or 9E10 immunoprecipitates from wild-type cells were probed with the 9E10 antibody (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

lid1p-myc associates with several other proteins in vivo. (A) lid1p-myc is an ∼100-kDa protein. KGY1302 whole-cell lysates (lane 1) or 9E10 immunoprecipitates from KGY1302 lysates (lane 2) were resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred to a PVDF membrane, and the membrane was probed with the 9E10 antibody. Molecular mass standards (in kilodaltons) are indicated. (B) Wild-type (lanes 1 and 3) or KGY1302 (lid1::lid1-myc) (lanes 2 and 4) native 35S-labeled cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with the 9E10 antibody, and immunoprecipitates were resolved by SDS-PAGE. Labeled proteins from two separate experiments for 1 day (lanes 1 and 2) or 7 days (lanes 3 and 4) were visualized by fluorography. Migrations of molecular mass markers (in kilodaltons) are indicated. Bands specific to the KGY1302 immunoprecipitate are indicated (●). An arrowhead indicates the band corresponding to lid1p-myc. (C) Cut9p-HA is an ∼90-kDa protein. A KGY1365 whole-cell lysate (lane 1) or an HA.11 immunoprecipitate (lane 2) was resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred to a PVDF membrane, and the membrane was probed with the HA.11 antibody.

In order to determine whether lid1p-myc associates with other proteins in vivo, lid1-myc or wild-type cells were labeled in vivo with Tran35S-label. Whole-cell lysates were prepared under native conditions from labeled cells and then subjected to immunoprecipitation with the 9E10 antibody. Several proteins, including lid1p-myc, were immunoprecipitated from KGY1302 cell lysates but not from wild-type cell lysates, suggesting that lid1p is part of a multiprotein complex (Fig. 3B). That the indicated band corresponded to lid1p-myc was determined by 9E10 immunoprecipitation from 35S-labeled denatured cell lysates (data not shown).

lid1-myc cosediments with cut9-HA.

The specific, in vivo association of lid1p-myc with proteins of ∼160, ∼75, and ∼65 kDa (Fig. 3B) was consistent with the hypothesis that lid1p may comprise a component of the APC/C in S. pombe. (APC/C components cut4p, cut9p, and nuc2p are proteins of 166, 78, and 67 kDa, respectively [18, 40, 49]). In order to examine further the possibility that lid1 may encode an APC/C component, an epitope-tagged version of the APC/C component cut9p was generated by integrating a DNA fragment encoding three copies of the HA epitope into the S. pombe genome just upstream of the cut9 stop codon (see Materials and Methods). Lysates from the epitope-tagged strain (cut9::cut9-HA; KGY1365) were subjected to immunoprecipitation and immunoblot analysis with the monoclonal anti-HA antibody HA.11. A protein which migrated with an apparent molecular mass of ∼90 kDa was detected in KGY1365 lysates and HA.11 immunoprecipitates (Fig. 3C) but not in wild-type lysates or immunoprecipitates (data not shown).

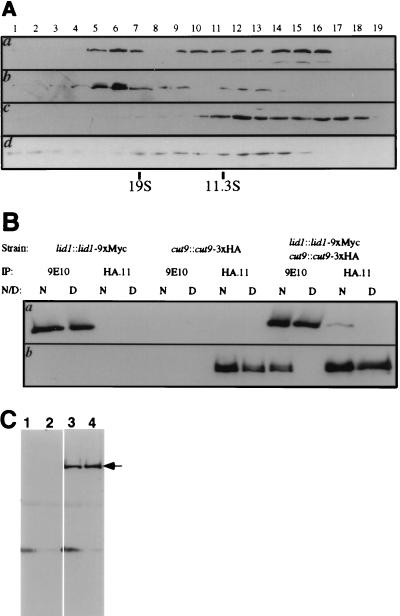

In order to determine whether lid1p cosediments with the APC/C, the sedimentation profiles of lid1p-myc and cut9p-HA were compared. A lysate from a double-tagged strain (lid1::lid1-myc cut9::cut9-HA) was prepared and subjected to sucrose gradient sedimentation analysis. Gradient fractions were collected, resolved by SDS-PAGE, blotted to membranes, and probed with either the anti-HA monoclonal antibody 12CA5 to detect cut9p-HA or the anti-myc monoclonal antibody 9E10 to detect lid1p-myc. lid1p-myc peaked three times: once in fraction 6, again in fraction 10, and lastly in fraction 15, which would correspond to monomeric lid1p-myc (Fig. 4A, panel a). cut9p-HA showed a bimodal distribution (Fig. 4A, panel b), as shown previously for the endogenous cut9 protein (47, 49). Significantly, the high-molecular-weight subpopulation of cut9p-HA peaked in fraction 6, along with lid1p-myc, at just greater than 19S. This high-molecular-weight fraction of cut9p-HA contained more slowly migrating forms of cut9p-HA which have been shown previously to be the result of phosphorylation (47).

FIG. 4.

lid1p-myc is a component of the 20S APC/C. (A) lid1p-myc and cut9p-HA cosediment at ∼20S. Fractions were collected from the bottom (fraction 1) of 10 to 30% sucrose gradients and then resolved by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with the 9E10 antibody to detect lid1p-myc (a and c) or with 12CA5 to detect cut9-HA (b and d). Panels a and b show identical fractions from lysates prepared from the lid1::lid1-myc cut9::cut9::3xHA strain. Panel c shows fractions from the lid1::lid1-myc cut9-665 strain that had been shifted to 36°C for 4 h prior to lysis. Panel d shows fractions from the cut9::cut9-HA lid1-6 strain that had been shifted to 36°C for 4 h prior to lysis. Fraction numbers are indicated above the panels. Peak fractions of the 19S sedimentation marker thyroglobulin and the 11.3S sedimentation marker catalase are indicated below the panels. (B) lid1-myc and cut9p-HA coimmunoprecipitate from KGY1366 (lid1::lid1-myc cut9::cut9-HA) whole-cell lysates but not from KGY1302 (lid1::lid1-myc) or KGY1365 (cut9::cut9-HA) cell lysates. KGY1302 (lanes 1, 2, 3, and 4), KGY1365 (lanes 5, 6, 7, and 8), or KGY1366 (lanes 9, 10, 11, and 12) native (N) (lanes 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, and 11) or denatured (D) (lanes 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12) cell lysates were immunoprecipitated (IP) with 9E10 (lanes 1, 2, 5, 6, 9, and 10) or HA.11 (lanes 3, 4, 7, 8, 11, and 12) antibodies. Immunoprecipitates were resolved by SDS-PAGE and then subjected to immunoblotting with 9E10 (a) or HA.11 (b) antibodies. (C) lid1p-myc coimmunoprecipitates with cut9p and nuc2p. Polyclonal antibodies to cut9p (lanes 1 and 3) or nuc2p (lanes 2 or 4) were used for immunoprecipitation from wild-type (lanes 1 and 2) or KGY1302 (lanes 3 and 4) cell lysates. The immunoprecipitates were resolved by SDS-PAGE and blotted with 9E10 antibodies. lid1p-myc is indicated with an arrow.

Although the APC/C components cut9p and nuc2p have been shown to cosediment in wild-type cells, cut9p and nuc2p fail to cosediment at ∼20S in lysates prepared from cut9 or nuc2 temperature-sensitive mutants (47). In order to determine whether temperature-sensitive mutations in cut9 likewise might affect sedimentation of lid1p-myc, a lid1::lid1-myc cut9-665 strain was constructed. Cells were grown to exponential phase at a permissive temperature, then shifted to a restrictive temperature (36°C) for 4 h. None of lid1p-myc sedimented at ∼20S in the absence of cut9+ function; most sedimented in a smaller complex (Fig. 4A, panel c). The reciprocal experiment was also performed; cut9p-HA sedimentation in a lid1-6 temperature-sensitive background was examined. Similar to lid1p-myc in the cut9-665 mutant, most of the cut9-HA in the lid1-6 mutant migrated with a lower sedimentation value (Fig. 4A, panel d). These data suggest that lid1+ function is required for the structural integrity of the APC/C.

lid1p-myc associates with cut9p-HA and nuc2p in vivo.

The cosedimentation of lid1p-myc and cut9p-HA in sucrose gradients, as well as the failure of lid1p-myc to migrate in a high-molecular-weight complex in a cut9-665 background, further suggested a physical interaction among lid1p and cut9p and/or other APC/C components. In order to determine directly whether lid1p-myc and cut9p-HA associate in vivo, native or denatured lysates were prepared from KGY1302 (lid1::lid1-myc), KGY1365 (cut9::cut9-HA), or KGY1366 (lid1::lid1-myc cut9::cut9-HA) cells. Lysates then were subjected to immunoprecipitation and immunoblot analysis with 9E10 or HA.11 antibodies. Probing with 9E10 revealed a band of ∼100 kDa (lid1p-myc) in KGY1302 and KGY1366 native lysates, as well as in KGY1302 denatured lysates, but not in KGY1366 denatured lysates or KGY1365 native or denatured lysates. Conversely, probing with HA.11 revealed a band of ∼90 kDa (cut9p-HA) in KGY1365 and KGY1366 native cell lysates, as well as in KGY1365 denatured cell lysates, but not in KGY1366 denatured lysates or KGY1302 native or denatured lysates (Fig. 4B). Less lid1p-myc was immunoprecipitated with HA antibodies than with 9E10 antibodies, presumably because not all lid1p is within the 20S complex (compare Fig. 4A, panels a and b). Coimmunoprecipitation of lid1p-myc with known components of the S. pombe APC/C was confirmed by using polyclonal antibodies against nuc2p and cut9p (a generous gift of M. Yanagida) (Fig. 4C).

lid1p is required for the multiubiquitination of cut2p.

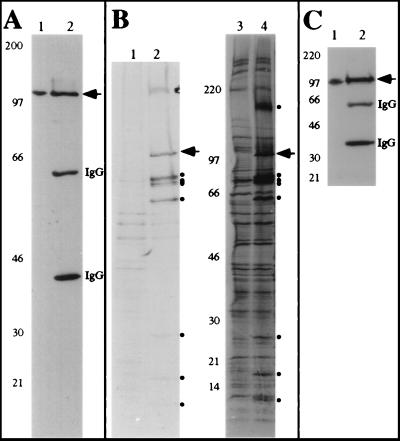

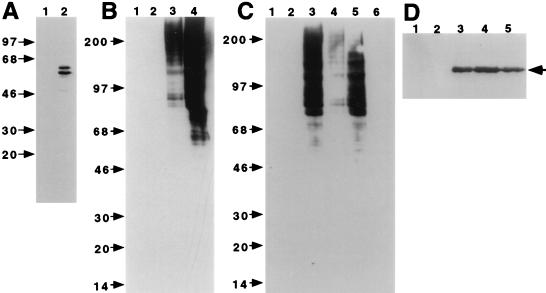

To test directly whether lid1p was required for the E3 ligase activity of the APC/C, we examined the ubiquitination of cut2p, a known destruction box-containing APC/C target (12, 17), in the presence and absence of lid1p function. cut2p is required for sister chromatid separation and is targeted for APC/C-mediated destruction at the onset of anaphase (12). In order to detect cut2p readily, we placed sequences encoding 13 copies of the myc epitope tag at the 3′ end of the cut2 coding region; the tagged version was fully functional in that the cut2::cut2-myc strain was indistinguishable from the wild type in morphology and growth rate. A doublet at ∼62 kDa corresponding to cut2p-myc was readily detected by immunoblotting with 9E10 (Fig. 5A); endogenous cut2p is 42 kDa and also migrates as a doublet in SDS-PAGE (12). The cut2::cut2-myc allele was crossed into an mts3-1 strain with or without the lid1-6 mutation. mts3+ encodes subunit 14 of the 26S proteasome (15), and in the mts3-1 mutant strain, multiubiquitinated conjugates accumulate at the nonpermissive temperature because of their failure to become degraded (4, 15). Thus, cut2p-myc would be expected to accumulate ubiquitin conjugates in the mts3-1 mutant but only if the APC/C was active. To allow us to purify ubiquitin-conjugated proteins, a His6-tagged version of ubiquitin was expressed in wild-type, mts3-1, mts3-1 cut2::cut2-myc, and mts3-1 cut2::cut2-myc lid1-6 strains. Extracts from these strains were purified by using Ni2+-NTA resin and separated by SDS-PAGE, and ubiquitinated cut2p-myc was detected by immunoblotting. High-molecular-weight bands were detected in the mts3-1 cut2::cut2-myc strain expressing His6-ubiquitin at the restrictive temperature (Fig. 5, lanes 4). These bands were much reduced in the mts3-1 cut2::cut2-myc lid1-6 strain (Fig. 5, lanes 3). They were absent from the wild-type and mts3-1, strains which do not express myc epitope-tagged proteins (Fig. 5, lanes 1 and 2). This result clearly establishes that lid1p is required for APC/C-mediated ubiquitination of cut2p.

FIG. 5.

lid1+ and dim1+ functions are required for ubiquitination of cut2p. (A) Total cell lysates from wild-type (lane 1) or cut2::cut2-myc (lane 2) cells were resolved by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with 9E10. In the cut2p-myc doublet in lane 2, the lower-molecular mass protein is likely to be a degradation product of cut2p-myc. (B) His6-ubiquitin was expressed from the nmt1 promoter for 22 h at 25°C in wild-type cells (lane 1), mts3-1 mutant cells (lane 2), mts3-1 cut::cut2-myc lid1-6 cells (lane 3), or mts3-1 cut::cut2-myc cells (lane 4), and the strains were then shifted to 36°C for a further 4 h. His6-ubiquitin conjugates were purified on Ni2+-NTA columns as described in Materials and Methods, and ubiquitinated cut2p-myc was detected by immunoblotting with 9E10. (C) As in panel B except that the strains examined were the wild-type (lane 1), mts3-1 (lane 2), mts3-1 cut::cut2-myc (lanes 3 and 5), mts3-1 cut::cut2-myc lid1-6 (lane 4), and mts3-1 cut::cut2-myc dim1-35 (lane 6) strains. (D) Prior to purification on Ni2+-NTA columns, an aliquot of each lysate used for panel C was examined for the presence of cut2p-myc by immunoblotting with 9E10. Lysates were from wild-type cells (lane 1), mts3-1 mutant cells (lane 2), mts3-1 cut::cut2-myc cells (lane 3), mts3-1 cut::cut2-myc dim1-35 cells (lane 4), and mts3-1 cut::cut2-myc lid1-6 cells (lane 5). The arrow indicates the position of cut2p-myc. Numbers on the left in panels A to C are molecular masses in kilodaltons.

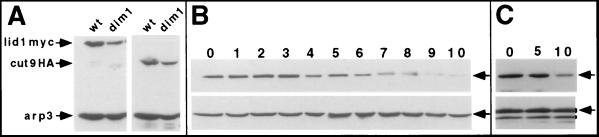

dim1+ function is required to maintain lid1p levels.

To investigate the basis for the negative genetic interaction between lid1-6 and dim1-35, we examined whether an epitope-tagged version of dim1p, dim1p-HA, could be coimmunoprecipitated with lid1p-myc. We found no evidence for such a stable association (data not shown). We also examined the level of lid1p-myc in the dim1-35 mutant. Interestingly, we found that it was reduced significantly (three- to fourfold in separate experiments as quantified with the use of a Molecular Dynamics Storm instrument) compared with that in wild-type cells grown at 36°C (Fig. 6A). In contrast, the level of cut9p-HA was not affected significantly in dim1-35 cells (Fig. 6A and data not shown). To examine the effect of dim1+ loss on lid1p-myc levels in a different manner and at a different arrest point within the cell cycle, we crossed the lid1::lid1-myc cassette into strain KGY1180, which contains a dim1 null allele and a conditional expression cassette of the dim1+ cDNA. More specifically, KGY1180 contains a single integrated version of dim1+ cDNA under control of the thiamine-repressible nmt1-T81 promoter. When grown in medium lacking thiamine, this strain is phenotypically wild type, but when placed in medium containing thiamine, the cell number stops increasing by 13 h and cells arrest in G2 phase due to the loss of the essential dim1p (5). Protein lysates were prepared from samples of this strain collected periodically after a shift to thiamine-containing medium, and the level of lid1p-myc was determined by immunoblotting equal amounts of protein. As shown in Fig. 6B, lid1p-myc levels began to drop at 6 h and fell to very low levels by 10 h (before complete cell cycle arrest), whereas the level of the loading control, arp3p, did not change. In a second experiment examining the consequence of the loss of dim1+ function for the abundance of lid1p-myc, we compared the level of lid1p-myc with that of cdc2p (Fig. 6C). Again, lid1p-myc levels were significantly reduced by 10 h after shutoff of nmt1-T81 dim1+, whereas the level of cdc2p did not change. Thus, the abundance of lid1p-myc depends upon the function of dim1+.

FIG. 6.

lid1p-myc levels drop in the absence of dim1+ function. (A) Wild-type (wt) or dim1-35 (dim1) cells producing lid1p-myc or cut9p-HA were grown to mid-log phase at 25°C and then shifted to 36°C for 4 h. Total protein lysates were prepared and immunoblotted with 9E10 (left panel) or 12CA5 (right panel) antibodies. Immunoblotting with anti-arp3p antibodies provided a loading control. (B and C) The dim1::his3+ strain carrying a single integrated copy of nmt1-T81::dim1+ (KGY1180) and the lid1::lid1-myc cassette was grown in minimal medium lacking thiamine and then shifted to rich medium containing thiamine to repress expression of the nmt1-T81::dim1+ cassette. Samples were collected for analysis at the indicated times (given in hours). Protein lysates were prepared and immunoblotted for lid1p-myc (top panels), arp3p (bottom panel in panel B), or cdc2p with anti-PSTAIRE monoclonal antibody (bottom panel in panel C).

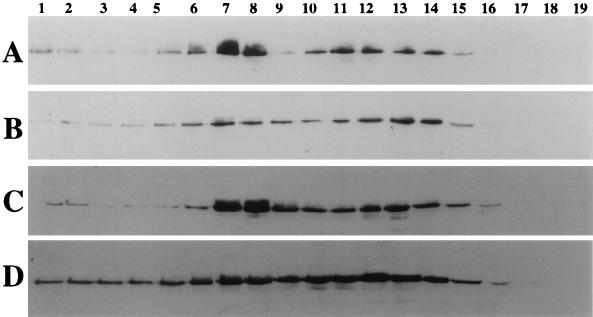

To determine whether the loss of lid1p in dim1-35 cells affected the abundance of the 20S APC/C, we compared the sedimentation behaviors of cut9p-HA from wild-type and dim1-35 mutant cells grown at 36°C for 4 or 6 h. When isolated from dim1-35 cells, cut9p-HA sedimented more broadly in the gradient, with the largest concentrations detected in fractions 12 and 13 rather than 7 and 8 (compare Fig. 7A with B and C with D). Fractions 7 and 8 correspond to the position of the 20S complex. Indeed, the majority of cut9p-HA sedimented more slowly than that isolated from wild-type cells, indicating that it was coming out of, or not being as efficiently incorporated into, the 20S APC/C complex. Further, the cut9p-HA that was present at 20S was not phosphorylated to the same extent as in wild-type cells. The blot in Fig. 7D was overexposed relative to that in Fig. 7C to illustrate this point. We conclude from these data that dim1+ function affects the abundance and posttranslational modification of the APC/C in S. pombe.

FIG. 7.

dim1+ function affects the abundance of the 20S APC/C. cut9::cut9-HA (A and C) and cut9::cut9-HA dim1-35 (B and D) cells were grown to mid-log phase at 25°C and shifted to 36°C for 4 h (A and B) or 6 h (C and D). Cell lysates were prepared and layered over sucrose gradients. Fractions were collected from the bottom (fraction 1), resolved by SDS-PAGE, and immunoblotted with 12CA5 monoclonal antibodies. Reactive proteins were visualized by ECL. Fraction numbers are indicated above the panels. Peak fractions of the 19S sedimentation marker thyroglobulin and the 11.3S sedimentation marker catalase are indicated below the panels.

dim1+ function is required for the multiubiquitination of cut2p.

Given that the abundance of the 20S APC/C complex declined in the absence of dim1+ function, we reasoned that the activity of the APC/C might also be compromised. To test this possibility, we constructed a dim1-35 mts3-1 cut2::cut2-myc strain and introduced the His6-tagged version of ubiquitin into it. When this strain was tested for the ubiquitination of cut2p-myc following a shift to the nonpermissive temperature, in parallel with the strains described above, we found that cut2p-myc ubiquitination was abolished in the absence of dim1+ function (Fig. 5C, lane 6). The immunoblot in Fig. 5D shows that cut2p-myc was present in the dim1-35 and lid1-6 protein lysates from which the ubiquitin-conjugated proteins were purified. Taken together, these data indicate that dim1+ function is required for APC/C function.

lid1p-myc protein levels are constant through the cell cycle.

Because of the decrease in lid1p levels in the absence of dim1 function in both dim1-35 cells, which arrest in mitosis, and dim1 null cells, which arrest at the G2/M transition, we became interested to determine whether lid1p-myc levels varied through the cell cycle. To this end, a synchronized G2 population of lid1::lid1-myc cut9::cut9-HA (KGY1366) cells was isolated by centrifugal elutriation. Samples were collected as cells progressed through two synchronous cell cycles. The levels of cut9p-HA and cdc13p (as positive controls for cell cycle periodicity), arp3p (as a loading control), and lid1p-myc were determined by immunoblotting. The hyperphosphorylated form of cut9p-HA was observed just prior to each peak of septation (Fig. 8a, t = 40 min and t = 180 min), as was reported previously (47). cdc13p levels are known to fall during mitosis (7, 13), and indeed we observed that cdc13p levels dropped coincident with each septation peak (Fig. 8b, t = 60 min and t = 200 min). In contrast, lid1p-myc levels did not undergo any significant changes through the cell cycle, nor did lid1p-myc undergo any detectable shifts in electrophoretic mobility suggestive of posttranslational modifications (Fig. 8c). We also examined lid1p-myc levels in a cdc25-22 block-and-release experiment, which provides a higher degree of cell cycle synchrony. Again, we did not observe any fluctuation in lid1p-myc levels (data not shown).

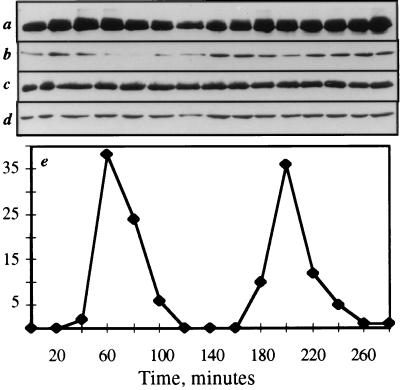

FIG. 8.

lid1p-myc levels remain constant through the cell cycle. KGY1366 cells were synchronized in early G2 by centrifugal elutriation and then released into fresh medium. As cells progressed through the cell cycle, synchrony was monitored by determination of septation index at 20-min intervals (e). At the same intervals, samples were collected for analysis of cut9p-HA (a), cdc13p (b), lid1p-myc (c), and arp3p (d) protein levels.

DISCUSSION

Identification of lid1p, a component of the S. pombe APC/C.

dim1p is a 17-kDa, evolutionarily conserved, essential protein. A temperature-sensitive allele of dim1, dim1-35, causes arrest in mitosis and inability to initiate chromosome segregation, although spindle elongation occurs. In contrast, cells containing a null mutation in dim1 are unable to enter mitosis and block at the G2/M transition (5). To gain further insight into dim1p function, we performed a synthetic lethal screen aimed at identifying proteins that interact with dim1p. Here, we report our characterization of one lid (for lethal in dim1-35) mutant, the lid1-6 mutant. In a dim1+ background, lid1-6 causes a temperature-sensitive phenotype. Specifically, lid1-6 mutant cells are unable to undergo anaphase at the restrictive temperature; short metaphase spindles form but do not elongate, and the chromosomes do not separate. Based on this phenotype, which is similar to that of cut4 and cut9 mutants (40, 49), we hypothesized that lid1+ might encode a component of the S. pombe APC/C, since cut4p and cut9p are established APC/C components (47, 49). The APC/C is a 20S complex that acts as an E3 ubiquitin ligase essential for anaphase onset in all eukaryotes examined (reviewed in references 8, 17, 26, and 44).

In order to test the hypothesis that lid1 may encode an APC/C component, we cloned the lid1 gene by complementation of the lid1-6 temperature-sensitive phenotype. DNA sequencing and hypothetical translation of the lid1 gene provided no clues as to the function of lid1. However, consistent with the notion that lid1+ encodes a component of the APC/C, an epitope-tagged variant of lid1p, lid1p-myc, coimmunoprecipitated with several other proteins, including cut9p and nuc2p, which are known members of the S. pombe APC/C. The results of sucrose gradient analysis also are consistent with the interpretation that lid1p is a component of the S. pombe APC/C; lid1p-myc cosediments with cut9p-HA at ∼20S, the sedimentation profile of lid1p-myc depends upon functional cut9+, and the ability of cut9p-HA to sediment at 20S depends upon functional lid1+. Furthermore, lid1p function is required for the multiubiquitination of cut2p, a known target of the APC/C (12, 13). These data establish that lid1p is a component of the S. pombe APC/C and also that its function is necessary for maintaining the integrity of the 20S APC/C.

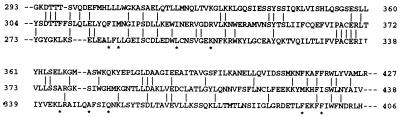

Our comparison of the predicted lid1 protein sequence with sequences available in the databases revealed no significant homologies or motifs. Our failure to detect a budding yeast homolog was especially surprising given our assumption that the APC/C components would be conserved between budding and fission yeasts. However, while this work was in progress, the sequences of most, if not all, components of the human and yeast APC/Cs were reported (50, 52). When the sequence of the human APC4 protein was used as a query to probe databases, limited similarity between it and S. pombe ORF Z97209 was observed, but no homolog was detected in budding yeast (50). S. pombe ORF Z97209 encodes lid1p. Budding yeast Apc4p also was reported to have weak similarity with S. pombe ORF Z97209 (52). We have aligned lid1p with APC4 and Apc4p and have found a central region of 133 or 134 amino acids which contains significant sequence conservation (Fig. 9). There is 24% identity and 34% similarity between S. pombe lid1p and human APC4 in this region and 22% identity and 31% similarity between S. pombe lid1p and S. cerevisiae Apc4p. Outside this region, there is little sequence similarity among the three proteins, although there are two other stretches of sequence similarity between S. pombe lid1p and human APC4 (data not shown). Taken together, these protein sequence comparisons indicate that lid1p, APC4, and Apc4p are distantly related, and it will be interesting to determine whether they are conserved functionally (50). The isolation of a conditional lethal mutation in the S. pombe component most similar to both human APC4 and budding yeast Apc4p provides an excellent opportunity to test this directly; the lack of sequence conservation makes it unlikely that cross complementation of the yeast null alleles would be successful.

FIG. 9.

Sequence comparison of lid1p with human APC4 and S. cerevisiae Apc4p. The indicated amino acid sequences of human APC4 (top line), S. pombe lid1p (middle line), and S. cerevisiae Apc4p (bottom line) were aligned. Amino acids identical in lid1p and APC4 or Apc4p are indicated by vertical dashes. Amino acids identical in APC4 and Apc4p are indicated by asterisks.

dim1p is required for APC/C integrity and activity.

The APC/C is active towards destruction box-containing substrates only during mitosis and G1 phase (reviewed in references 8, 17, 26, and 44). Its activation towards mitotic cyclins in vitro has been attributed to phosphorylation of its components rather than to alterations in its composition or abundance (reviewed in references 8, 17, 26, and 44). For these reasons, we were surprised to learn that the abundance of lid1p fell in the absence of dim1+ function. However, this observation provides a reasonable explanation for the synthetic lethal interaction between lid1-6 and dim1-35. In a dim1-35 mutant background, there is probably an insufficient amount of functional lid1-6p to support cell cycle progression. The loss of lid1p in the absence of dim1 activity is not due to a specific cell cycle block, because lid1p was lost both in dim1-35 and in dim1 null cells. dim1-35 cells arrest in mitosis with a cut-like phenotype, but dim1 null cells arrest at the G2/M transition (5). In terms of understanding the biochemical mechanism of dim1p action, we can now direct our efforts to understanding the role of dim1p in maintaining the level of lid1p. dim1p is not stably associated with lid1p (our unpublished observations), and it will be very instructive to learn whether dim1p affects the stability or synthesis of lid1p or lid1 mRNA. The interaction with lid1p is probably insufficient to explain the essential role of dim1p, however, since overexpression of lid1+ does not rescue the dim1-35 mutant (data not shown).

By determining the sedimentation behavior of cut9p-HA in dim1-35 cells, we have found that the reduction of lid1p in dim1 mutants is translated into a lower level of the 20S APC/C complex. This is not surprising given the interdependence of various components for the integrity of the complex. As two examples, in a cut9 mutant, neither nuc2p nor lid1p remains in a 20S complex; in a nuc2 or lid1 mutant, cut9p does not sediment at 20S (reference 47 and this study). Thus, the failure of dim1-35 cells to execute chromosome segregation can be most easily explained by a reduction of APC/C activity caused by reduced levels of lid1p and the consequent reduction in the amount of the APC/C complex. Consistent with this interpretation, we have shown that loss of dim1+ function abrogates the multiubiquitination of cut2p-myc. Whether the failure of cells carrying the dim1 null allele to enter mitosis can be attributed to the lack of APC/C activity remains to be determined. In addition to the reduced levels of the 20S complex in the dim1-35 mutant, we noted a reduction in the phosphorylation of cut9p-HA. Whether this is a consequence or a cause of the reduction in 20S complex abundance or an unrelated phenomenon also remains to be determined.

In summary, we have uncovered a dependency between dim1+ function and the function of the APC/C. Future efforts will be directed at understanding how dim1p affects lid1p abundance and whether it acts through intermediate components to do so.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank J. Bahler, J. Pringle, and K. Nasmyth for providing the epitope tagging cassettes, K. Gull for the TAT-1 monoclonal antibody, S. Moreno for tagged ubiquitin construct and advice on its use, and M. Yanagida for polyclonal antibodies to cut9p and nuc2p. We are grateful to Hayes McDonald for advice on epitope tagging, Ryoma Ohi and Jennifer Morrell for constructive comments on the manuscript, and all members of the Gould lab for their support and advice during the course of this work.

This work was supported by NIH grant 47728 to K.L.G. L.D.B. was supported by a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship. K.L.G. is an associate investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bahler J, Wu J Q, Longtine M S, Shah N G, McKenzie III A, Steever A B, Wach A, Philippsen P, Pringle J R. Heterologous modules for efficient and versatile PCR-based gene targeting in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Yeast. 1998;14:943–951. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199807)14:10<943::AID-YEA292>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balasubramanian M K, McCollum D, Gould K L. Cytokinesis in fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Methods Enzymol. 1997;283:494–506. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(97)83039-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barbet N, Muriel W J, Carr A M. Versatile shuttle vectors and genomic libraries for use with Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Gene. 1992;114:59–66. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(92)90707-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benito J, Martin-Castellanos C, Moreno S. Regulation of the G1 phase of the cell cycle by periodic stabilization and degradation of the p25rum1 CDK inhibitor. EMBO J. 1998;17:482–497. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.2.482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berry L D, Gould K L. Fission yeast dim1(+) encodes a functionally conserved polypeptide essential for mitosis. J Cell Biol. 1997;137:1337–1354. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.6.1337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Charles J F, Jaspersen S L, Tinker-Kulberg R L, Hwang L, Szidon A, Morgan D O. The Polo-related kinase Cdc5 activates and is destroyed by the mitotic cyclin destruction machinery in S. cerevisiae. Curr Biol. 1998;8:497–507. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70201-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ciechanover A. The ubiquitin-proteasome proteolytic pathway. Cell. 1994;79:13–21. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90396-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen-Fix O, Koshland D. The metaphase-to-anaphase transition: avoiding a mid-life crisis. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1997;9:800–806. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(97)80080-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Creanor J, Mitchison J M. The kinetics of the B cyclin p56cdc13 and the phosphatase p80cdc25 during the cell cycle of the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. J Cell Sci. 1996;109:1647–1653. doi: 10.1242/jcs.109.6.1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Evans T, Rosenthal E T, Youngbloom J, Distel D, Hunt T. Cyclin: a protein specified by maternal mRNA in sea urchin eggs that is destroyed at each cleavage division. Cell. 1983;33:389–396. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90420-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fikes J D, Becker D M, Winston F, Guarente L. Striking conservation of TFIID in Schizosaccharomyces pombe and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nature. 1990;346:291–294. doi: 10.1038/346291a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Funabiki H, Kumada K, Yanagida M. Fission yeast Cut1 and Cut2 are essential for sister chromatid separation, concentrate along the metaphase spindle and form large complexes. EMBO J. 1996;15:6617–6628. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Funabiki H, Yamano H, Nagao K, Tanaka H, Yasuda H, Hunt T, Yanagida M. Fission yeast Cut2 required for anaphase has two destruction boxes. EMBO J. 1997;16:5977–5987. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.19.5977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Glotzer M, Murray A W, Kirschner M W. Cyclin is degraded by the ubiquitin pathway. Nature. 1991;349:132–138. doi: 10.1038/349132a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gordon C, McGurk G, Wallace M, Hastie N D. A conditional lethal mutant in the fission yeast 26 S protease subunit mts3+ is defective in metaphase to anaphase transition. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:5704–5711. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.10.5704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gould K L, Moreno S, Owen D J, Sazer S, Nurse P. Phosphorylation at Thr167 is required for Schizosaccharomyces pombe p34cdc2 function. EMBO J. 1991;10:3297–3309. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb04894.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hershko A. Roles of ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis in cell cycle control. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1997;9:788–799. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(97)80079-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hirano T, Hiraoka Y, Yanagida M. A temperature-sensitive mutation of the Schizosaccharomyces pombe gene nuc2+ that encodes a nuclear scaffold-like protein blocks spindle elongation in mitotic anaphase. J Cell Biol. 1988;106:1171–1183. doi: 10.1083/jcb.106.4.1171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hochstrasser M. Ubiquitin, proteasomes, and the regulation of intracellular protein degradation. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1995;7:215–223. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(95)80031-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hoffman C S. Preparation of yeast DNA. In: Ausubel F A, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seidman J G, Smith J A, Struhl K, editors. Current protocols in molecular biology. New York, N.Y: John Wiley and Sons; 1993. pp. 13.11.1–13.11.4. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoheisel J D, Maier E, Mott R, McCarthy L, Grigoriev A V, Schalkwyk L C, Nizetic D, Frances F, Lehrach H. High-resolution cosmid and P1 maps spanning the 14 Mbp genome of the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Cell. 1993;73:109–120. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90164-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Irniger S, Nasmyth K. The anaphase-promoting complex is required in G1 arrested yeast cells to inhibit B-type cyclin accumulation and to prevent uncontrolled entry into S-phase. J Cell Sci. 1997;110:1523–1531. doi: 10.1242/jcs.110.13.1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Irniger S, Piatti S, Michaelis C, Nasmyth K. Genes involved in sister chromatid separation are needed for B-type cyclin proteolysis in budding yeast. Cell. 1995;81:269–278. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90337-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Juang Y L, Huang J, Peters J M, McLaughlin M E, Tai C Y, Pellman D. APC-mediated proteolysis of Ase1 and the morphogenesis of the mitotic spindle. Science. 1997;275:1311–1314. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5304.1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Keeney J B, Boeke J D. Efficient targeted integration at leu1-32 and ura4-294 in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Genetics. 1994;136:849–856. doi: 10.1093/genetics/136.3.849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.King R W, Deshaies R J, Peters J M, Kirschner M W. How proteolysis drives the cell cycle. Science. 1996;274:1652–1659. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5293.1652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.King R W, Peters J M, Tugendreich S, Rolfe M, Hieter P, Kirschner M W. A 20S complex containing CDC27 and CDC16 catalyzes the mitosis-specific conjugation of ubiquitin to cyclin B. Cell. 1995;81:279–288. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90338-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kumada K, Su S, Yanagida M, Toda T. Fission yeast TPR-family protein nuc2 is required for G1-arrest upon nitrogen starvation and is an inhibitor of septum formation. J Cell Sci. 1995;108:895–905. doi: 10.1242/jcs.108.3.895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lamb J R, Michaud W A, Sikorski R S, Hieter P A. Cdc16p, Cdc23p and Cdc27p form a complex essential for mitosis. EMBO J. 1994;13:4321–4328. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06752.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lees E. Cyclin dependent kinase regulation. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1995;7:773–780. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(95)80060-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McCollum D, Feoktistova A, Morphew M, Balasubramanian M, Gould K L. The Schizosaccharomyces pombe actin-related protein, Arp3, is a component of the cortical actin cytoskeleton and interacts with profilin. EMBO J. 1996;15:6438–6446. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Michaelis C, Ciosk R, Nasmyth K. Cohesins: chromosomal proteins that prevent premature separation of sister chromatids. Cell. 1997;91:35–45. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)80007-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moreno S, Klar A, Nurse P. Molecular genetic analysis of fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Methods Enzymol. 1991;194:795–823. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)94059-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morgan D O. Principles of CDK regulation. Nature. 1995;374:131–134. doi: 10.1038/374131a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Murray A W, Solomon M J, Kirschner M W. The role of cyclin synthesis and degradation in the control of maturation promoting factor activity. Nature. 1989;339:280–286. doi: 10.1038/339280a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Peters J M, King R W, Hoog C, Kirschner M W. Identification of BIME as a subunit of the anaphase-promoting complex. Science. 1996;274:1199–1201. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5290.1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pines J. Cyclins and cyclin-dependent kinases: a biochemical view. Biochem J. 1995;308:697–711. doi: 10.1042/bj3080697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Prentice H L. High efficiency transformation of Schizosaccharomyces pombe by electroporation. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:621. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.3.621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Samejima I, Yanagida M. Bypassing anaphase by fission yeast cut9 mutation: requirement of cut9+ to initiate anaphase. J Cell Biol. 1994;127:1655–1670. doi: 10.1083/jcb.127.6.1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sazer S, Sherwood S W. Mitochondrial growth and DNA synthesis occur in the absence of nuclear DNA replication in fission yeast. J Cell Sci. 1990;97:509–516. doi: 10.1242/jcs.97.3.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schwab M, Lutum A S, Seufert W. Yeast Hct1 is a regulator of Clb2 cyclin proteolysis. Cell. 1997;90:683–693. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80529-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shirayama M, Zachariae W, Ciosk R, Nasmyth K. The Polo-like kinase Cdc5p and the WD-repeat protein Cdc20p/fizzy are regulators and substrates of the anaphase promoting complex in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 1998;17:1336–1349. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.5.1336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Townsley F M, Ruderman J V. Proteolytic ratchets that control progression through mitosis. Trends Cell Biol. 1998;8:238–244. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(98)01268-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Visintin R, Prinz S, Amon A. CDC20 and CDH1: a family of substrate-specific activators of APC-dependent proteolysis. Science. 1997;278:460–463. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5337.460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Woods A, Sherwin T, Sasse R, MacRae T H, Baines A J, Gull K. Definition of individual components within the cytoskeleton of Trypanosoma brucei by a library of monoclonal antibodies. J Cell Sci. 1989;93:491–500. doi: 10.1242/jcs.93.3.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yamada H, Kumada K, Yanagida M. Distinct subunit functions and cell cycle regulated phosphorylation of 20S APC/cyclosome required for anaphase in fission yeast. J Cell Sci. 1997;110:1793–1804. doi: 10.1242/jcs.110.15.1793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yamamoto A, Guacci V, Koshland D. Pds1p, an inhibitor of anaphase in budding yeast, plays a critical role in the APC and checkpoint pathway(s) J Cell Biol. 1996;133:99–110. doi: 10.1083/jcb.133.1.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yamashita Y M, Nakaseko Y, Samejima I, Kumada K, Yamada H, Michaelson D, Yanagida M. 20S cyclosome complex formation and proteolytic activity inhibited by the cAMP/PKA pathway. Nature. 1996;384:276–279. doi: 10.1038/384276a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yu H, Peters J M, King R W, Page A M, Hieter P, Kirschner M W. Identification of a cullin homology region in a subunit of the anaphase-promoting complex. Science. 1998;279:1219–1222. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5354.1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zachariae W, Nasmyth K. TPR proteins required for anaphase progression mediate ubiquitination of mitotic B-type cyclins in yeast. Mol Biol Cell. 1996;7:791–801. doi: 10.1091/mbc.7.5.791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zachariae W, Shevchenko A, Andrews P D, Ciosk R, Galova M, Stark M J, Mann M, Nasmyth K. Mass spectrometric analysis of the anaphase-promoting complex from yeast: identification of a subunit related to cullins. Science. 1998;279:1216–1219. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5354.1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zachariae W, Shin T H, Galova M, Obermaier B, Nasmyth K. Identification of subunits of the anaphase-promoting complex of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Science. 1996;274:1201–1204. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5290.1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]