Abstract

It was the purpose of the study to investigate the readiness of faculty members at two private universities in the United States to teach online when a pandemic caused a shift to emergency remote or online teaching. Results show that instructors were somewhat ready to accomplish tasks related to online teaching. Participating instructors reported they felt most competent with course communication and least competent with time management. Significant differences in responses were found based on online teaching experience prior to the pandemic and years of online teaching experience. Results show that instructors who had confidence in online teaching were more prepared for the task than those who were not confident. This study has implications for online instructors, support staff who provide professional development opportunities and training for instructors, and administrators who provide resources for faculty and staff to support quality online course and program offerings at their institutions.

Keywords: Online instructors, Online teaching readiness, Preparation, Higher education

Introduction

In 2019, 46% of faculty who participated in a study supported by Inside Higher Ed (Jaschik & Lederman, 2019) had taught an online course. The number of instructors who have taught online courses has continued to increase since its inception; however, online teaching is still a new experience for some. According to Lederman (2019), “While faculty participation in online learning continues to edge up over all, it is extremely uneven – by institution type, discipline and mind-set” (para. 10). For example, faculty members employed at private universities are less likely to teach in the online learning environment than instructors at public institutions.

Seaman et al. (2018) reported that 6,359,121 (or 31.6% of) students participated in at least one distance education course in Fall 2016 in the United States (U.S.). Of those students, 68.9% were enrolled at public institutions, whereas 31.1% were enrolled in private colleges and universities; 18.0% attended private non-profit and 13.1% attended private for-profit institutions.

Regardless of whether instructors are teaching at private or public institutions, faculty competence in online pedagogy and technical skills are critical when faculty members are tasked with creating effective online learning environments for students. Competency is defined by the International Board of Standards for Training, Performance, and Instruction as “. .. a knowledge, skill or attitude that enables one to effectively perform the activities of a given occupation or function to the standards expected in employment” (Richey et al., 2001, p. 31). Bigatel et al. (2012) identified seven elements of online teaching competencies: active learning, administration/leadership, instructor responsiveness, multimedia, conflict resolution and etiquette, technical competence, and policy enforcement; however, the author did not include tasks that pertained to course design. In contrast, both Guasch et al. (2010) and Martin, Budhrani, et al. (2019a) included course design in their online teaching readiness framework. The authors define online teaching readiness as the level of ability or preparedness to complete necessary tasks in the delivery of online courses.

In March 2020, due to the breakout of an infectious disease that caused a pandemic, most higher education institutions quickly transitioned to emergency remote or online teaching while semesters or quarters had already started. However, Brooks and Grajel (2020) mention many instructors in higher education were not ready to teach online. For example, a large percentage of faculty had not used basic technologies or specialized support services essential for online teaching. Additionally, researchers found that only a small percentage of faculty members preferred to teach fully online courses (Brooks & Grajel, 2020; Galanek & Gierdowski, 2019). In this paper, we will share and discuss the findings of a study aimed at investigating the online teaching readiness of faculty members at two private universities in the U.S. shortly after this shift occurred.

Literature Review

The literature points out that teaching in the online environment requires different competencies than in the face-to-face environment, particularly in the areas of technology, facilitation, and engagement (Ko & Rossen, 2017; Martin, Budhrani, et al., 2019a; Wray et al., 2008). However, only 67% of faculty members reported they had participated in professional development for the design of an online or blended course, and only 39% received assistance from an instructional designer to develop or revise an online course (Jaschik & Lederman, 2019). Hung and Jeng (2013) studied the intention of educational technology doctoral students to participate in online teaching. Results showed that doctoral students were not deterred from teaching online simply because they did not have the skills. They assumed that they would be able to learn how to teach online in training sessions before delivering an online course.

When conducting a systematic review of 44 publications, Cutri and Mena (2020) developed a concept matrix for online teaching readiness: affective dispositions, pedagogical approaches, and organizational orientations. Affective concepts include behaviors such as risk taking, accepting change or dealing with stress. Sharing and conversing online with students are examples of pedagogical approaches. Organizational orientations pertain to structure or time management. In their review, the authors classified five areas of research found in the literature: online teaching evaluations; instructors’ identity and beliefs; transition to online learning; effective online teaching; and competencies for online teaching.

There is a plethora of literature on online readiness or e-readiness available. For example, researchers have studied online teaching readiness in K-12 settings (Howard et al., 2020; Hung, 2016; Keramati et al., 2011) and learners’ online learning readiness (Hung et al., 2010; Pillay et al., 2007; Yu & Richardson, 2015). Others measured the readiness of industry sectors or institutions in different countries (see Aydin & Tasci, 2005; Darab & Montazer, 2011; Dimitri & Ayanda, 2013; Purnomo & Lee, 2010). Gay (2016) researched instructors’ online teaching readiness in the Caribbean. Few studies have focused on online teaching readiness of instructors in higher education in the U.S. prior to COVID-19 (see Downing & Dyment, 2013; Martin, Budhrani, et al., 2019a; Scherer et al., 2021).

Downing and Dyment (2013) found the majority of faculty members who taught fully online courses in a teacher education program lacked the confidence and competence to teach online before they started to teach online. Some of the reasons for their insecurities included the perceived lack of technical or pedagogical skills. Other researchers (Scherer et al., 2021) focused on identifying instructor readiness profiles (low, inconsistent, and high readiness) using factors such as T-PACK self-efficacy, online presence, and institutional support; and explaining the membership in the profiles with the use of additional aspects such as instructor characteristics, and contextual and cultural factors. The largest group (52.1%) was the inconsistent readiness group. Only 8.5% of participating instructors were in the high readiness group, whereas 39.4% were in the low readiness group. The authors indicated that instructors in higher education “are not a homogenous group with respect to their reported readiness” (p. 14). In order to adequately support instructors with different profiles, different types or levels of support may be necessary.

Martin, Budhrani, et al. (2019a) identified four areas of online teaching competencies. The first competency is course design which includes pedagogy, development of content and instructional events, facilitation, and assessment. The second competence is communication and interaction. Instructors need to provide learners with timely responses and feedback and facilitate and participate in discussions. The third competence is effective time management during the delivery of the course because monitoring student progress and supporting online learners can be time consuming. The fourth area of competence is technical competence which includes technical knowledge, skills, and abilities related to systems, platforms, and instructional technology that instructors are required to utilize. The authors used these four factors as a framework to develop and validate the Faculty Readiness to Teach Online (FRTO) instrument.

Purpose and Research Questions

Online teaching readiness can impact faculty satisfaction which is a critical factor in the quality and effectiveness of online courses and programs (Bolliger & Wasilik, 2009). Because instructors at small private institutions are less likely to teach online than instructors at large public institutions (Brooks & Grajel, 2020), it was the purpose of the study to investigate the online teaching readiness of faculty members at two small private non-profit higher education institutions in the U.S. after these universities shifted to emergency remote or online teaching due to a pandemic. The study is important because it provides a snapshot of participants’ perceived readiness, preparedness, and confidence at the onset of the pandemic. The following questions guided the investigation:

How ready were instructors to teach online before a national emergency was declared?

Is there a correlation between instructors’ levels of confidence and preparedness?

What factors contributed to instructors’ confidence in teaching online based on whether they had taught online prior to COVID-19?

Are there differences in responses based on individual characteristics?

Methodology

Setting and Sample

The population included instructors who taught at two small private universities in Texas and in Maine. The university in Texas had over 1600 enrolled students in Fall 2018 semester and employs 80 full-time faculty members. It has 60 undergraduate and graduate programs in arts, business, education, humanities, nursing, theology, social sciences, and sciences. Most programs are delivered face-to-face; however, students in four majors can study fully online.

Approximately 3500 students are enrolled at the small liberal arts college in Maine. The institution offers over 40 undergraduate and graduate programs in business, education, health, nursing, sciences, and theology that can be completed both face-to-face and online. Eighty full-time faculty members serve at the second site. We selected the two sites because many of the instructors at both institutions still taught traditional courses on campus.

Data Collection

Following approval from all institutional review boards involved, data were collected after universities in the U.S. made the transition from face-to-face delivery to emergency remote teaching due to the pandemic. The data collection occurred during the last week of May through the second week in June 2020. All instructors were invited to participate in the study via e-mail. The e-mail invitation included information about the study, an embedded link to the online survey housed on a secure server, and instructions to rate all survey items prior to participants transitioning to emergency remote teaching due to COVID-19. In order to increase the response rate, one reminder e-mail was sent after one week.

Instrument

The FRTO instrument (Martin, Budhrani, et al., 2019a) was used to collect the data after obtaining permission from the authors. The instrument has 32 five-point Likert-type items that includes four factors: course design, course communication, time management, and technical competence. The FRTO questionnaire has two sections that include the same Likert-type items. The first section, attitude, measures the perceived importance instructors place on the task. The second section, ability, measures instructors’ perceived ability to complete the task. For the purpose of this study, only the ability construct was used. The original 5-point Likert scale ranges from 1, I cannot do it at all to 5, I can do it well. Because we were interested in participants’ ability prior to COVID-19, we changed the 5-point scale to past tense form: 1 (I could not do it at all) to 5 (I could do it well). We also modified the examples provided in the items to make the statements relevant to our population. Martin, Budhrani, et al. (2019a) reported that the instrument is a valid and reliable (α = 0.92) instrument.

Data Analysis

A total of 59 individuals responded to the invitation to participate in the study. However, two cases had one-third or more data missing and were deleted. After cleaning the data, 57 valid cases remained. Missing data for scale items were replaced with the series mean, and frequencies and descriptive statistics were generated. To ascertain differences in responses based on personal and professional characteristics, independent samples t tests (e.g., gender, prior online teaching experience) and a series of Analysis of Variance (e.g., years of online teaching) was performed.

A correlational analysis was conducted to determine whether instructors’ preparedness to teach online correlated positively with their self-reported level of confidence in teaching online. Open coding was used to analyze responses to two open-ended questions (Creswell, 2014; Creswell & Poth, 2018; Patton, 2015). Researchers recorded frequencies and developed categories based on themes that emerged. These were coded through constant comparison (Miles & Huberman, 1994).

Participants

Of the 57 participating instructors, 51.8% were female, 46.4% were male, and 1.6% did not wish to disclose their gender. Participants’ ages ranged from 32 to 75 (M = 53.6, SD = 10.55), and they had taught in the university setting from 2 to 37 years (M = 15.0, SD = 9.21). The majority had taught online prior to COVID-19 (69.6%). Additional professional demographics are displayed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Professional characteristics of respondents (N = 56)

| n | % | n | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Academic Rank | Academic Discipline | ||||

| Adjunct Faculty | 16 | 28.6 | Arts/Music/Theater | 2 | 3.6 |

| Instructor | 1 | 1.8 | Business | 7 | 12.5 |

| Assistant Professor | 16 | 28.6 | Education | 9 | 16.1 |

| Associate Professor | 8 | 14.3 | Health Sciences | 9 | 16.1 |

| Full Professor | 15 | 26.8 | Humanities | 7 | 12.5 |

| Religion | 7 | 12.5 | |||

| Level Taught | Sciences | 9 | 16.1 | ||

| Undergraduate | 36 | 64.3 | Social Sciences | 5 | 8.9 |

| Graduate | 7 | 12.5 | |||

| Both | 13 | 23.2 | |||

| Teaching Environments | |||||

| Online only | 10 | 17.9 | |||

| Face-to-face only | 25 | 44.6 | |||

| Both | 21 | 37.5 | |||

Results and Discussion

Online Teaching Readiness

Overall, participating instructors were able to complete most tasks included in the instrument. The total scores ranged from 96 to 160 (M = 134.4, SD = 17.57) on a scale that had a minimum score of 32 and a maximum score of 160. Respondents’ total mean scores ranged from 3.00 to 5.00 (M = 4.20, SD = 0.55). In other words, they were somewhat ready to teach online. In the next section, we present and discuss the results for each of the instrument’s four subscales.

Course design

Three items on the Course Design subscale received mean scores above 4.50 (Table 2). Instructors felt most confident about managing grades (M = 4.75), creating assignments (M = 4.56), and writing course objectives (M = 4.51). Almost 90% of respondents agreed they could complete these tasks. The items that had a mean below 4.00 included the use of different instructional strategies (M = 3.79) and creation of instructional videos (M = 3.84). Fewer than 70% of instructors were able to complete these tasks.

Table 2.

Frequencies and descriptives for items on the Course Design subscale (N = 57)

| Percentage | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | 1/2 | 3 | 4/5 | M | SD |

| CD1. Create an online course orientation (e.g., introduction, getting started) | 3.5 | 8.8 | 87.7 | 4.33 | 0.79 |

| CD2. Write measurable learning objectives | 1.8 | 5.3 | 92.9 | 4.51 | 0.69 |

| CD3. Design learning activities that provide students opportunities for interaction (e.g., discussion forums, wikis) | 3.5 | 15.8 | 80.8 | 4.18 | 0.83 |

| CD4. Organize instructional materials in modules or units | 3.6 | 5.3 | 91.3 | 4.49 | 0.83 |

| CD5. Create instructional videos (e.g., lecture videos, demonstrations, video tutorials) | 7.0 | 24.6 | 68.4 | 3.84 | 0.98 |

| CD6. Use different teaching methods in the online environment (e.g., brainstorming, collaborative activities, discussions, presentations) | 10.6 | 24.6 | 64.9 | 3.79 | 1.10 |

| CD7. Create online quizzes and tests | 10.5 | 8.8 | 80.7 | 4.21 | 1.10 |

| CD8. Create online assignments | 0.0 | 10.5 | 89.5 | 4.56 | 0.68 |

| CD9. Manage grades online | 1.8 | 1.8 | 96.5 | 4.75 | 0.66 |

Note. Scale ranging from 1 (I could not do it at all) to 5 (I could do it well)

Course communication

Over 95% of instructors felt confident about four tasks on the Course Communication subscale (Table 3). These items also received the highest mean scores on this subscale. Participants felt most confident about the use of e-mail (M = 4.98), and course announcements or e-mail reminders (M = 4.91). They were able to respond to student inquiries (M = 4.89) and provide feedback (M = 4.75) within an appropriate time frame. Instructors felt the least confident with using synchronous web-conferencing technologies (M = 3.77), and applying copyright laws (M = 3.86) and accessibility policies (M = 3.95).

Table 3.

Frequencies and descriptives for items on the Course Communication subscale (N = 57)

| Percentage | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | 1/2 | 3 | 4/5 | M | SD |

| CC1. Send announcements/e-mail reminders to course participants | 0.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 4.91 | 0.29 |

| CC2. Create and moderate discussion forums | 3.6 | 14.0 | 82.4 | 4.26 | 0.90 |

| CC3. Use e-mail to communicate with learners | 0.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 4.98 | 0.13 |

| CC4. Respond to student questions promptly (e.g., 24 to 48 h) | 0.0 | 1.8 | 98.2 | 4.89 | 0.36 |

| CC5. Provide feedback on assignments (e.g., 7 days from submission) | 0.0 | 3.5 | 96.4 | 4.75 | 0.51 |

| CC6. Use synchronous web-conferencing tools (e.g., Canvas Conferencing, REEL, Skype) | 10.5 | 31.6 | 57.9 | 3.77 | 1.10 |

| CC7. Communicate expectations about student behavior (e.g., netiquette, penalty for late assignments) | 0.0 | 8.8 | 91.2 | 4.40 | 0.65 |

| CC8. Communicate compliance regarding academic integrity policies | 0.0 | 8.8 | 91.2 | 4.46 | 0.66 |

| CC9. Apply copyright law and fair use guidelines when using copyrighted materials | 8.8 | 19.3 | 72.0 | 3.86 | 1.04 |

| CC10. Apply accessibility policies to accommodate student needs | 8.8 | 14.0 | 77.2 | 3.95 | 0.93 |

Note. Scale ranging from 1 (I could not do it at all) to 5 (I could do it well)

Time management

None of the items on the Time Management subscale received a mean score above 4.50. Three items had a mean score below 4.00: items 1, 4, and 6 (Table 4). Participating instructors felt the least confident with using strategies to reduce their time spent with course facilitation (M = 3.49), setting time aside to learn about new strategies and tools (M = 3.58), and allocating time to design a course prior to delivering it (M = 3.81).

Table 4.

Frequencies and descriptives for items on the Time Management subscale (N = 57)

| Percentage | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | 1/2 | 3 | 4/5 | M | SD |

| TM1. Schedule time to design the course prior to delivery (e.g., a semester before delivery) | 17.6 | 12.3 | 70.2 | 3.81 | 1.36 |

| TM2. Schedule weekly hours to facilitate the online course | 8.8 | 14.0 | 77.2 | 4.18 | 1.09 |

| TM3. Use features in the learning management system in order to manage time (e.g., online grading, rubrics, SpeedGrader, calendar) | 8.8 | 15.8 | 75.4 | 4.16 | 1.00 |

| TM4. Use facilitation strategies to manage time spent on the course (e.g., assign student discussion leaders) | 15.8 | 38.6 | 45.6 | 3.49 | 1.09 |

| TM5. Spend weekly hours to grade assignments | 1.8 | 10.5 | 87.7 | 4.40 | 0.75 |

| TM6. Allocate time to learn about new strategies or tools | 15.8 | 28.1 | 56.1 | 3.58 | 1.21 |

Note. Scale ranging from 1 (I could not do it at all) to 5 (I could do it well)

Technical competence

Respondents were most confident with basic computer operations (M = 4.89) and the navigation in the course management system (M = 4.63) (see Table 5). They were less confident with creating and editing videos (M = 3.04), setting up groups in the course management system (M = 3.57), using external collaboration tools, and sharing open educational resources (M = 3.86).

Table 5.

Frequencies and descriptives for items on the Technical Competence subscale. (N = 57)

| Percentage | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | 1/2 | 3 | 4/5 | M | SD |

| TC1. Complete basic computer operations (e.g., creating and editing documents, managing files and folders) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 4.89 | 0.31 |

| TC2. Navigating within the course in the learning management system (e.g., Canvas, Bright Space/D2L, etc.) | 0.0 | 3.6 | 96.4 | 4.63 | 0.55 |

| TC3. Use the learning management system to set up teams/groups | 10.7 | 42.9 | 46.4 | 3.57 | 1.00 |

| TC4. Use collaborative tools (e.g., Google Drive, One Drive) | 7.2 | 26.8 | 66.1 | 3.86 | 0.95 |

| TC5. Create and edit videos (e.g., Screencastomatic, Panopto) | 30.3 | 37.5 | 32.1 | 3.04 | 1.15 |

| TC6. Share open educational resources (e.g., learning websites, Web resources, game and simulations) | 8.9 | 19.6 | 71.4 | 3.86 | 0.93 |

| TC7. Access online help desk/resources for assistance | 7.1 | 12.5 | 80.4 | 4.04 | 0.84 |

Note. Scale ranging from 1 (I could not do it at all) to 5 (I could do it well)

Subscales

Of the four subscales, the Communication subscale had the highest mean, whereas the Time Management subscale received the lowest mean score (see Table 6). On one hand, it was surprising that instructors were most comfortable with communication in online classrooms; however, 10 individuals had taught online courses and 21 participants had taught in both environments—campus-based and online—prior to COVID-19. Those who had taught in both environments were likely able to use some of the same communication tools and strategies in courses that needed to be transitioned to remote or online teaching.

Table 6.

Descriptives and reliability coefficients for subscales

| Subscale | M | SD | No. of Items | α |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Course design | 4.30 | 0.629 | 9 | .89 |

| Course communication | 4.43 | 0.442 | 10 | .81 |

| Time management | 3.94 | 0.895 | 6 | .90 |

| Technical competence | 3.98 | 0.593 | 7 | .81 |

Note. Scale ranging from 1 (I could not do it at all) to 5 (I could do it well)

The literature points out that online teaching can be time consuming and stressful (Boettcher & Conrad, 2016; Ko & Rossen, 2017), particularly for novices. Some online instructors may experience stress due to the feeling of constantly being “on” the job because of expectations from students and administrators and the ineffectiveness and inefficiencies of technology tools and systems (Halupa & Bolliger, 2020).

After the data were collected, internal reliability coefficients were calculated to evaluate the overall consistency of the scale and its subscales. The Cronbach alpha for the instrument was high (α = 0.95) and the internal reliability coefficients were acceptable for all four subscales (Table 6). This confirms the instrument is reliable and measures the intended constructs consistently.

Preparation for and Confidence with Online Teaching

Participants were moderately prepared to teach online (M = 3.91, SD = 1.19). Most of them reported they were moderately or very prepared (69.1%). Over 10% were either not at all prepared or slightly prepared, whereas one fifth of respondents were somewhat prepared. When asked how confident participating instructors were with teaching online, 50% responded they were very confident. Close to one fifth of participants were either moderately or somewhat confident, and 10.7% were slightly or not at all confident. Overall results indicate they were moderately confident (M = 4.05, SD = 1.15).

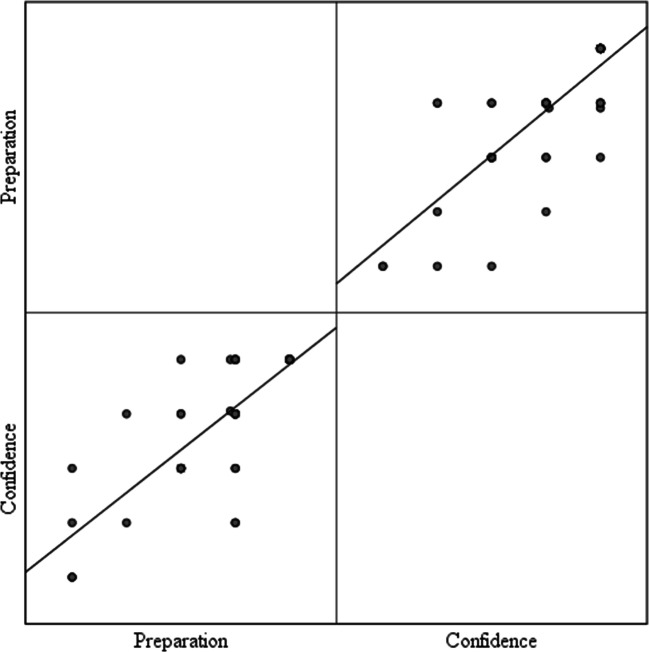

Correlation coefficients were compared among self-reported levels of preparation and confidence. The results of the correlational analysis show that the correlation was statistically significant, r(55) = .81, p < .001. Results suggest individuals who had confidence in online teaching tended to state that they were more prepared for the task than those who were not confident (Fig. 1). This substantiates concerns of faculty members mentioned in the literature at the turn of the twenty-first century pertaining to faculty resistance to online teaching. It points to the importance of preparation and, subsequently, the necessary supports online instructors must have from the institution’s administration such as technical support, professional development opportunities and training, adequate compensation and workload, and other necessary resources (see Betts, 1998; Bower, 2001; Hartman et al., 2000; Howell et al., 2004).

Fig. 1.

Scatterplot matrix

Contributing Factors that Impact Confidence

Positive factors

Fifty-four individuals responded to the open-ended question regarding factors that contributed to their confidence in teaching online. Thirty-one instructors reported their prior online teaching experience was a factor, although their experience in years of online teaching and their delivery methods (asynchronous vs. synchronous) varied. Of those who had taught online prior to the pandemic, three instructors had received training (e.g., Quality Matters, online teaching certificates). Others had taught hybrid courses or experienced online courses as a student. Two individuals credited the technology support provided by their college.

Of those who had not taught online prior to the pandemic, 11 participants reported prior professional experience gave them confidence to teach online. Nine of them were familiar with the online platform or applications at the time of the transition because they used the course management system in traditional courses. Two instructors reported that years in the physical classroom gave them confidence to teach online. Seven individuals felt confident because they were adept with technology or sought out resources to learn more about online teaching. Five respondents felt they were supported by either the college (e.g., good training or resources) or textbook publishers.

Negative factors

The analysis of 53 responses to the question about factors that negatively impacted their ability to teach online revealed eight themes: ability, assessment, delivery format, institutional support, students, technology, time, and workload issues. Sixteen individuals mentioned their unfamiliarity with systems and tools, strategies for student interaction and engagement, and limited design skills hindered their ability to teach online. The shift in delivery method was perceived as occurring too quickly by 10 respondents. They felt they did not have enough time to plan and develop quality course materials or learn about new instructional technologies. Poor software and technology systems, and issues with the delivery format (e.g., inability to see all students on the computer screen, classroom management) were mentioned by 10 instructors.

Seven individuals commented on the lack of institutional support such as poor instructional design support and limited training. Workload concerns such as time requirements for online teaching, larger class sizes, system changes, and the integration of additional requirements (e.g., integration of videos) were voiced by six instructors. Five participants were concerned about student resources (e.g., adequate internet access, course materials) and other student-related issues such as student expectations, attitudes, and readiness. Two persons were concerned about the integrity of student assessments.

Our results align with prior findings of researchers who found instructors with prior online teaching experience, participation in training, and familiarity with course tools had more confidence in their abilities compared to instructors who had not (Clay, 1999; Martin, Budhrani, et al., 2019a; Muñoz Carril et al., 2013). Similar instructor responses to both open-ended questions—regarding positive and negative factors—have been found by other researchers (Betts, 1998; Bower, 2001). However, the transition due to the pandemic left many instructors, even those with prior online teaching experience, scrambling to prepare their courses for emergency remote or online delivery due to the fact that their semester had already started. Johnson et al. (2020), for example, reported that most of the institutions surveyed in their study had switched to emergency remote or online teaching in Spring 2020 due to the pandemic. Those without prior online teaching experience had to learn how to do so quickly.

Responses Based on Personal Characteristics

In order to ascertain differences in responses based on individual characteristics of instructors (e.g., online teaching experience prior to the pandemic and years of experience teaching online) on the four subscales, independent samples t tests and a series of Analysis of Variance tests was conducted. Using the Bonferroni approach to control for Type I error, a p value of less than .0125 (.05/4 = .0125) was required for significance.

Prior Online Teaching Experience

Independent samples t tests were conducted to evaluate whether instructors who taught online prior to the pandemic were more prepared as opposed to those who had not taught online. The test was significant, t(54) = 3.80, p = 0.001. Instructors who had taught online before COVID-19 felt readier (M = 4.36, SD = 0.49) compared to those who had not (M = 3.81, SD = 0.51). The effect size was relatively large (Cohen’s d = 1.10). The tests were also significant for three subscales (Table 7). Instructors who taught online prior to the pandemic had higher mean scores on the course design, course communication, and time management subscales. No significant differences were found on the technical competence subscale.

Table 7.

Differences on subscales based on prior teaching experience

| Prior Online Teaching | No Prior Online Teaching | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 39 | n = 17 | |||||

| Subscale | M | M | t(54) | p | 95% CI | Cohen’s d |

| CD | 4.48 | 3.83 | 4.04 | <.001 | [0.33, 0.97] | 1.10 |

| CC | 4.53 | 4.16 | 3.04 | .004 | [0.12, 0.61] | 0.83 |

| TM | 4.17 | 3.33 | 3.56 | <.001 | [0.37,1.31] | 0.97 |

Note. Scale ranging from 1 (I could not do it at all) to 5 (I could do it well)

Years of Online Teaching Experience

The results of a one-way ANOVA show that the test was significant for the course design subscale, F(3, 52) = 4.57, p = .006. Follow-up tests were conducted to evaluate pairwise differences among the means. The Dunnett’s C test was chosen because the researchers did not assume equal variances among the groups. There was a significant difference in the means between the groups that had taught 0 to 2 years, 7 to 10 years, and 11 or more years (Table 8). Those who were new or newer to online teaching (0 to 2 years) had lower mean scores than those who had taught for 7 years or longer. No significant differences were found on the other three subscales.

Table 8.

95% confidence intervals of pairwise differences in mean scores on the Course Design subscale in number of years teaching online (N = 56)

| Years Taught Online | M | SD | 0–2 | 7–10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–2 | 4.00 | 0.602 | ||

| 7–10 | 4.64 | 0.294 | [−1.12, −.15*] | |

| 11 or more | 4.69 | 0.366 | [−1.18, −.19*] | [−.55, .45] |

Note. *The 95% confidence interval does not contain zero, and therefore the difference in mean is significant using the Dunnett’s C procedure

Our results align with Martin, Budhrani, et al. (2019a) research who found that faculty with fewer years of online teaching experience had significant lower mean scores on the course design scale than their more experienced colleagues. It takes time to become a competent—or expert— online instructor who is not only a content expert but also serves as a good designer and facilitator. Expert instructors had time and experience to learn what works in the online environment, whereas novices often focus on getting the course content online (Kumar et al., 2019).

Limitations and Future Research

Some limitations need to be pointed out. First, the study is geographically limited because only two private institutions were included in the study. Other researchers may replicate the study with several institutions located in more diverse geographical regions. Second, the sample was small due to a low response rate. During the pandemic, it was difficult to obtain responses from faculty members who were in the process of transitioning from teaching face-to-face to online courses mid-semester. Because we were cognizant of their situation, only one e-mail reminder to participate in the study was sent out. Other researchers may include a larger population or a population at public universities. Because the pandemic caused such a rapid shift from on-campus or traditional teaching to emergency remote or online teaching, future research may examine which professional development activities and supports assisted instructors who did not already teach their courses online in making this transition successfully.

Our methodology initially included the population of students at both institutions; however, we were unable to obtain permissions from administrators to invite students to participate in the study during a pandemic. Hence, future studies may focus on the investigation of student perceptions of emergency remote or online learning due to COVID-19 and on lived experiences to ascertain their levels of readiness, and which factors may have influenced their self-reported abilities. Third, the data were self-reported due to the nature of the study. Respondents may have over- or under-estimated their actual abilities or may have been influenced by social desirability.

Conclusion and Recommendations

It was the purpose of the study to investigate the readiness of faculty members to teach online at two private higher education institutions in the U.S. after the pandemic caused universities to shift to emergency remote or online teaching. Participants in this study reported they were able to complete tasks listed in the instrument; however, they were not necessarily able to do them well. They were most confident with communicating with course participants and least confident managing their time while teaching an online course.

Of those who had taught online prior to the pandemic, prior online teaching experience or training contributed to their confidence. Faculty members who had not taught prior to the pandemic were confident because they had used some of the instructional systems in traditional courses or were adept with technology. Others relied on many years of teaching residential courses. Factors that impacted the confidence of instructors negatively pertained to lack of ability or institutional support, issues with the delivery format and technology, concerns for students, integrity of assessments, time constraints, and workload issues.

Nearly 70% of instructors felt they were moderately or very prepared to teach online. One of our major findings was that instructors who felt confident to teach online reported they were more prepared than those individuals who were not as confident. Because instructors tend to be confident when they feel prepared, we can help them in their transition from campus-based to online teaching by adequately preparing them for online teaching.

There is a vast amount of literature available that tells us how to assist in the preparation and support of instructors for online teaching. For example, Martin, Wang, et al. (2019b) found there are four critical areas of support for faculty: administrative, personnel, pedagogical, and technology support. Institutions may offer professional development workshops, one-on-one support, brown bags, and book talk sessions that focus on not only technology tools but also pedagogical frameworks; provide online resources such as help and how-to documentation; host on-campus conferences; and develop peer mentoring programs. Instructors should be encouraged to meet and/or collaborate with instructional designers, consult with disability specialists, and utilize support services provided by computer technology support personnel on campus. Additionally, faculty members can attend an online course as a student, online teaching conferences, and webinars offered by professional organizations. Other venues include online trainings that lead to badges, certificates or graduate-level credit. Administrators can support faculty by providing release time and reduced class sizes for instructors to provide them with the time needed to participate in professional development opportunities. Other support can include incentives and recognition for quality teaching and/or course design (Herman, 2012; Martin, Wang, et al., 2019b; Palloff & Pratt, 2011). Some significant differences in responses were found based on personal characteristics such as prior online teaching experience and years of online teaching.

Results of this study are important because they provide a baseline for a subset of instructors’ perceived readiness, preparedness, and confidence. The results reinforce the need for professional development and institutional support for instructors who transition from a traditional to an online teaching environment, regardless of whether is a voluntary or forced shift. Additionally, the study sheds light on which factors contributed to instructors’ confidence to teach online. Results also establish a clear link between instructor preparedness and confidence. When institutions desire qualified, confident online instructors, then they will need to assist their faculty in the preparation of online teaching. These results have implications for online instructors, support staff who provide professional development opportunities and training for instructors, and administrators who provide resources for faculty and staff in order to support quality online course and program offerings at their institutions.

Declarations

Ethics Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the university where the study took place (IRB protocol number: 1573451–1) and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants involved in the study.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Doris U. Bolliger, Email: dorisbolliger@gmail.com

Colleen Halupa, Email: chalupa@etbu.edu.

References

- Aydin CH, Tasci D. Measuring readiness for e-learning: Reflections from an emerging country. Educational Technology & Society. 2005;8(4):244–257. [Google Scholar]

- Betts, K. S. (1998). An institutional overview: Factors influencing faculty participation in distance education in the United States: An institutional study. Online Journal of Distance Learning Administration, 1(3). http://www.westga.edu/∼distance/Betts13.html

- Bigatel PM, Ragan LC, Kennan S, May J, Redmond BF. The identification of competencies for online teaching success. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks. 2012;16(1):59–78. doi: 10.24059/olj.v16i1.215. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boettcher JV, Conrad R-M. The online teaching survival guide: Simple and practical pedagogical tips. 2. Jossey-Bass; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bolliger DU, Wasilik O. Factors influencing faculty satisfaction with online teaching and learning in higher education. Distance Education. 2009;30(1):103–116. doi: 10.1080/01587910902845949. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bower, B. L. (2001). Distance education: Facing the faculty challenge. Online Journal of Distance Learning Administration, 4(2) https://www.westga.edu/~distance/ojdla/summer42/bower42.html

- Brooks, D. C., & Grajel, S. (2020). Faculty readiness to begin fully remote teaching. EDUCAUSE Research Notes. https://er.educause.edu/blogs/2020/3/faculty-readiness-to-begin-fully-remote-teaching

- Clay M. Faculty attitudes toward distance education at the State University of West Georgia. University of West Georgia Distance Learning Report; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell JW. Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. 4. Sage Publications; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell JW, Poth CN. Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. 4. Sage Publications; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cutri RM, Mena J. A critical reconceptualization of faculty readiness for online teaching. Distance Education. 2020;41(3):361–380. doi: 10.1080/01587919.2020.1763167. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Darab B, Montazer GA. An eclectic model for assessing e-learning readiness in the Iranian universities. Computers & Education. 2011;56(3):900–910. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2010.11.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dimitri A, Ayanda D. A comparative analysis of e-readiness assessment in Nigerian private universities and its impact on educational development. Information and Knowledge Management. 2013;3(11):30–37. [Google Scholar]

- Downing JJ, Dyment JE. Teacher educators’ readiness, preparation, and perceptions of preparing preservice teachers in a fully online environment: An exploratory study. The Teacher Educator. 2013;48(2):96–109. doi: 10.1080/08878730.2012.760023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Galanek, J. D., & Gierdowski, D. C. (2019). ECAR study of faculty and information technology, 2019. EDUCAUSE Center for Analysis and Research. https://www.educause.edu/ecar/research-publications/ecar-study-of-faculty-and-information-technology/2019/executive-summary-and-introduction

- Gay GHE. An assessment of online instructor e-learning readiness before, during, and after course delivery. Journal of Computing in Higher Education. 2016;28(2):199–220. doi: 10.1007/s12528-016-9115-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guasch T, Alvarez I, Espasa A. University teacher competencies in a virtual teaching/learning environment: Analysis of a teacher training experience. Teaching and Teacher Education. 2010;26(2):199–206. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2009.02.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Halupa C, Bolliger DU. Technology fatigue of faculty in higher education. Journal of Education and Practice. 2020;11(18):16–26. doi: 10.7176/JEP/11-18-02. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hartman J, Dziuban C, Moskal P. Faculty satisfaction in ALNs: A dependent or independent variable? Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks. 2000;4(3):155–177. doi: 10.24059/olj.v4i3.1892. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Herman JH. Faculty development programs: The frequency and variety of professional development programs available to online instructors. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks. 2012;16(5):87–106. doi: 10.24059/olj.v16i5.282. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Howard, S. K., Tondeur, J., Siddiq, F., & Scherer, R. (2020). Ready, set, go! Profiling teachers’ readiness for online teaching in secondary education. Technology, Pedagogy and Education. Advance online publication. 10.1080/1475939X.2020.1839543.

- Howell SL, Saba F, Lindsay NK, Williams PB. Seven strategies for enabling faculty success in distance education. The Internet and Higher Education. 2004;7(1):33–49. doi: 10.1016/j.iheduc.2003.11.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hung M-L. Teacher readiness for online learning: Scale development and teacher perceptions. Computers & Education. 2016;94:120–133. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2015.11.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hung M-L, Chou C, Chen C-H, Own Z-Y. Learner readiness for online learning: Scale development and student perceptions. Computers & Education. 2010;55(3):1080–1090. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2010.05.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hung W-C, Jeng I. Factors influencing future educational technologists’ intensions to participate in online teaching. British Journal of Educational Technology. 2013;44(2):255–272. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8535.2012.01294.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jaschik, S., & Lederman, D. (Eds.). (2019). 2019 survey of faculty attitudes on technology: A study by inside higher Ed and Gallup. Gallup, Inc. https://www.insidehighered.com/system/files/media/IHE_2019_Faculty_Tech_Survey_20191030.pdf

- Johnson N, Veletsianos G, Seaman J. U.S. faculty and administrator’s experiences and approaches in the early weeks of the COVID-19 pandemic. Online Learning Journal. 2020;24(2):6–21. doi: 10.24059/olj.v24i2.2285. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Keramati A, Afshari-Mofrad M, Kamrani A. The role of readiness factors in e-learning outcomes: An empirical study. Computers & Education. 2011;57(3):1919–1929. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2011.04.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ko S, Rossen S. Teaching online: A practical guide. 4. Routledge; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Martin F, Budhrani K, Ritzhaupt A. Award-winning faculty online teaching practices: Elements of award-winning courses. Online Learning. 2019;23(4):160–180. doi: 10.24059/olj.v23i4.2077. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lederman, D. (2019). Professors’ slow, steady acceptance of online learning: A survey. Inside Higher Ed. https://www.insidehighered.com/news/survey/professors-slow-steady-acceptance-online-learning-survey

- Martin F, Budhrani K, Wang C. Examining faculty perception of their readiness to teach online. Online Learning. 2019;23(3):97–119. doi: 10.24059/olj.v23i3.1555. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martin, F., Wang, C., Budhrani, K., Moore, R. L., & Jokiaho, A. (2019b). Professional development support for the online instructor: Perspectives of U.S. and German instructors. Online journal of distance learning administration, 22(3). Retrieved from https://www.westga.edu/~distance/ojdla/fall223/martin_wang_budhrani_moore_jokiaho223.html

- Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook. Sage Publications; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz Carril PC, González Sanmamed M, Hernández Sellés N. Pedagogical roles and competencies of university teachers practicing in the e-learning environment. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning. 2013;14(3):462–487. doi: 10.19173/irrodl.v14i3.1477. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Palloff RM, Pratt K. The excellent online instructor: Strategies for professional development. Jossey-Bass; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Patton MQ. Qualitative research & evaluation methods: Integrating theory and practice. 4. Sage Publications; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Pillay H, Irving K, Tones M. Validation of the diagnostic tool for assessing tertiary students’ readiness for online learning. Higher Education Research & Development. 2007;26(2):217–234. doi: 10.1080/07294360701310821. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Purnomo SH, Lee Y-H. An assessment of readiness and barriers towards ICY programme implementation: Perceptions of agricultural extension officers in Indonesia. International Journal of Education and Development using Information and Communication Technology. 2010;6(3):19–36. [Google Scholar]

- Richey RC, Fields DC, Foxon M. Instructional design competencies: The standards. 3. ERIC Clearinghouse on Information and Technology; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Scherer, R., Howard, S. K., Tondeur, J., & Siddiq, F. (2021). Profiling teachers’ readiness for online teaching and learning in higher education: Who’s ready? Computers in human behavior, 118. 10.1016/j.chb.2020.106675.

- Seaman, J. E., Allen, I. E., & Seaman, J. (2018). Grade increase: Tracking distance education in the United States. Babson Survey Research Group. http://onlinelearningsurvey.com/reports/gradeincrease.pdf

- Wray M, Lowenthal PR, Bates B, Stevens E. Investigating perceptions of teaching online & f2f. Academic Exchange Quarterly. 2008;12(4):243–248. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, T., & Richardson, J. C. (2015). An exploratory factor analysis and reliability analysis of the student online learning readiness (SOLR) instrument. Online Learning, 19(5). 10.24059/olj.v19i5.593