Abbreviations

- APRI

aspartate aminotransferase‐to‐platelet ratio index

- BMI

body mass index

- EASL

European Association for the Study of the Liver

- ESPGHAN

European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition

- FIB‐4

Fibrosis‐4

- IBD

inflammatory bowel disease

- INR

international normalized ratio

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- NAFLD

nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

- SES

socioeconomic status

- TNF‐alpha

tumor necrosis factor alpha

- TRAQ

Transition Readiness Assessment Questionnaire

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is the most common chronic liver disease seen in adults and children worldwide with a prevalence rate of 24% in adults and 10% in children in the United States. Many factors influence the development of NAFLD, including ethnicity, genetics, body weight, environment, coexisting diseases, and access to health care.1, 2 Childhood obesity is concerning because of its association with end‐stage liver disease in adulthood. For each 1‐unit gain in body mass index (BMI) z score among children aged 7 to 13 years, the risk for cirrhosis increases by 16% in adulthood.3 Moreover, the rate of fibrosis progression in adults with NAFLD is on average one stage of progression over 14 years; however, some adults exhibit the rapid fibrosis phenotype with accelerated fibrosis development in less than 10 years.4, 5 Consequently, early identification and longitudinal management of NAFLD from childhood to adulthood are crucial for preventing progression and complications.

Pediatric patients with NAFLD are best managed with a multidisciplinary team, including a gastroenterologist or hepatologist, dietician, exercise specialist, and psychological and other supportive services; however, there are currently no NAFLD‐specific models that seamlessly transition patients from the pediatric to adult provider. During this period, patients are at high risk for recidivism and loss of integrated care. Here, we propose a NAFLD‐specific model based on other models for chronic diseases to successfully transition pediatric patients with NAFLD to adult care.

History of Transition of Care

Transition of care is defined as the “purposeful, planned movement” of pediatric patients from child‐centered to adult‐oriented care,6 whereas transfer of care involves the direct handoff of a patient from the pediatric to adult provider. The concept of pediatric to adult transition of care programs is relatively new because many children with previously life‐threatening conditions, such as sickle cell disease and cystic fibrosis, did not survive into adulthood. Transition of care initiatives developed in large part to prevent the growing disparities in health care outcomes before and after transition. For instance, among patients with sickle cell disease in England, newly transitioned patients accounted for the highest number of emergency department visits between 2001 and 2010.7 Moreover, according to the type 1 diabetes US Exchange Clinic Registry, mean hemoglobin A1c and diabetic ketoacidosis incidence were highest in adolescence and young adults aged 18 to 25 years, respectively.8

In 2011, the American Academy of Pediatrics, American Association of Family Physicians, and American College of Physicians proposed the basis for the Six Core Elements of Health Care Transition9: (1) incorporation of a transition policy, (2) transition tracking and monitoring, (3) assessment of transition readiness, (4) the actual transfer to adult‐centered care, (5) transition completion, and (6) ongoing adult‐centered care. The Got Transition Program incorporated these elements into guidelines with detailed instructions for implementing a transition program.10

Addressing Barriers to Transition of Care

Transition of care requires recognition and intervention on numerous barriers to care to ensure successful outcomes in adulthood. Low socioeconomic status (SES), switching providers, and poor health literacy present major challenges for transition of care. In one study of patients with type 1 diabetes, patients with low SES had a 2‐fold increased risk for hospitalizations after transition compared with patients with high SES.11 This study also found that demographically matched control subjects who did not switch physicians were 77% less likely to be hospitalized compared with those who transferred to a new physician (RR: 0.23 [confidence interval: 0.05‐0.79]). Although the specific reasons for increased rates of hospitalization are incompletely understood, poor health literacy contributes to this disparity. Indeed, only 60% of adolescents and young adults are estimated to have adequate health literacy, and many struggle with communicative and critical health literacy, the higher level of health literacy required to analyze and integrate complex information to impact one’s own health care.12 Addressing this modifiable barrier to care will help ensure a successful transfer of care.

NAFLD‐Specific Barriers to Transition of Care

Many adolescents with NAFLD struggle with obesity, self‐esteem, or body image issues that also impact transition of care. According to the Endocrine Society, transition programs for obesity are an uncharted area that requires further research.13 Transition of care plays a role in obesity because adolescents and young adults are more likely to sustain a healthy diet and physical activity if they are encouraged to do so from an early age. A meta‐analysis commissioned by the Endocrine Society found that lifestyle interventions directed toward children and adolescents significantly decreased sedentary behavior (P = 0.05), but with a more significant impact in children (P = 0.02).14 Obesity development can be tied to environmental factors that develop from a young age, including consumption of sugary beverages, unhealthy sleeping patterns, long technology‐related screen time, and family stressors.13 These unhealthy habits often worsen when adolescents move away from home to attend college or start employment, particularly unhealthy eating and sedentary activity.15 Thus, addressing these behavioral and environmental causes of obesity early during the transition period will ensure better preparation for adult NAFLD care. Intense parental involvement has been shown to be beneficial for steering adolescents toward implementing healthy lifestyle changes.16 Yet, a restrictive and critical family environment can worsen outcomes by causing compensatory binge‐eating behavior and anxiety.13

Obesity is associated with other psychosocial stressors, including lower quality of life, poor self‐esteem, increased risk for depression and anxiety, higher‐than‐average risk for eating disorders, and increased risk for substance abuse.13 Heavier weight and body image dissatisfaction were found to predict lower self‐esteem in adolescent girls.17 A meta‐analysis of self‐esteem in overweight and obese adolescents determined that weight loss alone was insufficient to improve self‐esteem.18 Therefore, a team‐based approach involving health care providers, counselors, and family members is needed to address psychological and behavioral barriers to transition of care in patients with NAFLD, the majority of whom suffer from obesity.

Finally, substance abuse, and particularly alcohol consumption, presents another challenge for transitioning adolescents with NAFLD because, increasingly, the likely synergistic relationship between alcohol and obesity is being recognized.19 Many transitioning adolescents will attend college with increased access to alcohol and social pressure to drink. In one university survey, 77% of students reported drinking alcohol with the explicit purpose of getting drunk.20 Other risk factors for alcohol abuse in adolescence include family history of substance abuse and/or mood disorders, poor parental supervision, poor academic achievement and/or aspiration, and attention deficit disorder/attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.21

Adolescent Preparation

Early transitioning of care ensures ample preparation for transfer to adult care. Conversations surrounding transition of care should ideally begin at age 12 years22 with a discussion of personal and professional goals. Providers should gradually begin to empower adolescents to assume control of their own health. Providers should also engage adolescents early in NAFLD education and discuss behaviors that can impact both liver and general health, such as smoking, vaping, drug use, and sex. Due to limited office visits, parents should play an active role in discouraging substance abuse. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Association developed strategies for parents on how to counsel adolescents about alcohol (Fig. 1).21 These conversations can also be applied to other health‐related behaviors. As the transfer to adult care approaches, pediatric gastroenterologists and hepatologists should address their patients directly and, if possible, privately to simulate a typical adult NAFLD clinic experience. This would give them the opportunity to answer and pose their own questions without parental influence. According to the social‐ecological model of adolescent and young adult readiness for transition (SMART), patients should hone skills of self‐advocacy throughout the transition process with help from parents and providers.23

FIG 1.

Counseling adolescents about alcohol. *Can be applied to sex, tobacco, vaping, and drugs. Reproduced with permission from Underage Drinking Prevention National Media Campaign.35 Copyright 2012, SAMHSA.

Invariably, adolescents will feel ready to transition at different time points. Families are an important part of the care team and transition process and should be involved at each step. Providers can objectively assess transition readiness by using the disease‐neutral Transition Readiness Assessment Questionnaire (TRAQ).24 According to a review of disease‐neutral and disease‐specific transition readiness questionnaires, TRAQ was the best validated transition readiness tool.25

In addition to TRAQ, measures of self‐efficacy and self‐esteem may be important indicators of transition readiness.26 Self‐efficacy is the belief that one’s own abilities can overcome challenges. For chronic illness, self‐efficacy is positively linked to self‐management, adherence, and coping. Moreover, self‐esteem is correlated with an internal sense of achievement, motivation, and optimism. A low self‐esteem is associated with depression in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).27 Self‐efficacy and self‐esteem are dynamic and predict transition readiness better than patient demographics, SES, or disease knowledge itself.26 The General Self‐Efficacy Scale28 and the Rosenberg Self‐Esteem Scale29 can be used by NAFLD providers to perform these measurements. Low scores on these assessments can improve if addressed at a young age and should prompt referral to counseling.

Implementing Transfer of Care

Although transitioning may be daunting, a few key interventions can usher adolescents into adult care. Pairing patients with adult providers before their last pediatric visit can alleviate the stress of switching providers. The European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) and the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) formulated a comprehensive strategy to transition youth with liver disease to adult care.30 According to this joint society paper, essential documents should be prepared for patients to summarize the transition of care plan. These documents include the pediatric provider’s letter with a synthesis of their patient’s medical history, an emergency care plan, a transition checklist, a transition roadmap, and educational information on NAFLD. The transition checklist developed by the Royal College of Nursing31 and modified by the ESPGHAN/EASL ensures that pediatric providers cover key topics before transfer of care, including self‐advocacy, independent health care behavior, sexual health, psychological support, educational and vocational planning, and their patients’ health and lifestyle. The checklist also allows providers to categorize their patients’ mastery of each topic (early, middle, and late‐stage transition).

Pairing patients with adult providers before their last pediatric visit can alleviate the stress of switching providers. Transition programs should offer their patients the opportunity for combined visits or alternating visits between pediatric and adult provider before the final pediatric visit.15 This phase of transition of care ensures that adolescents and young adults are given a sufficient amount of time to build rapport with their adult provider before graduating from pediatric care. Another intervention includes the implementation of transition coordinators who can facilitate scheduling, augment NAFLD education and management, and troubleshoot barriers to care.22 In IBD, the use of a one‐time transition coordinator significantly improved transition readiness (P < 0.001), as well as the number of patients in disease remission (P < 0.01).32 Comprehensive transition clinics that include coordinators and nutrition, psychological, and social services can provide added support for patients with identified barriers to care. Finally, virtual support groups can be arranged to discuss shared challenges and successes.

Tracking Outcomes in NAFLD Adult Care

Transition programs should collect objective and qualitative data for analysis and quality improvement (Fig. 2). Clinical, laboratory, and imaging data can be used to track NAFLD progression among those who have transferred to the adult NAFLD provider. Anthropometric data, including weight, BMI with z scores, waist circumference, and blood pressure, should be collected. Laboratory markers of liver injury, from steatosis to advanced fibrosis and cirrhosis, should be assessed. Metabolic indicators, including a total lipid panel, glucose, insulin, and hemoglobin A1c, should be followed longitudinally. Other laboratory markers associated with NAFLD progression, such as Fibrosis‐4 (FIB‐4) and aspartate aminotransferase‐to‐platelet ratio index (APRI) scores, can be used. Other markers, such as α2‐macrolobulin, haptoglobin, apolipoprotein A1, leptin, and fibroblast growth factor‐21, are not readily available and can be considered in the context of research studies.33 Regarding noninvasive studies, transient elastography with controlled attenuation parameter can be used as an office‐based tool to estimate steatosis and fibrosis. Providers can also track individual quantifiable outcomes, including quality of life, satisfaction with adult care, adherence to a healthy lifestyle, understanding of disease process and medications, and attendance to clinic visits and social support groups.30 These data taken together can ultimately be used by NAFLD programs to tailor both individual care and the transition and transfer processes themselves. Regular interdisciplinary meetings should be held to assess patient outcomes and areas for improvement.

FIG 2.

Quality improvement in NAFLD. HOMA‐IR, homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance; TIMP‐1, Tissue inhibitor matrix metalloproteinase 1.

Transition of Care Impact

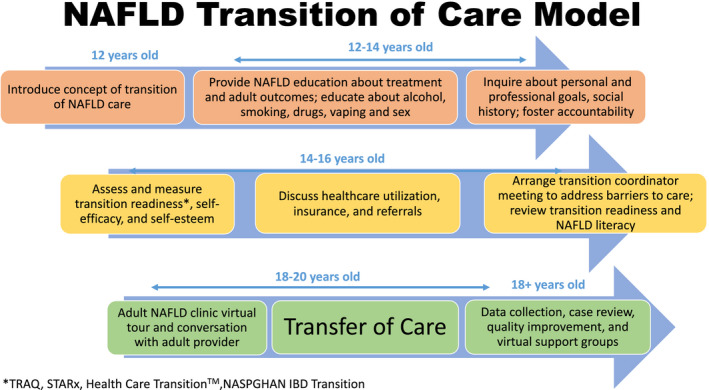

The end goal of transition of care is to build a strong foundation by which patients are encouraged to take control of their own health maintenance and to stave off disease progression. In our experience, we link patients directly from the pediatric NAFLD clinic to the adult NAFLD clinic located within the same medical campus. Pediatric patients are provided with educational resources on NAFLD, as well as a guideline for the transition process. We have created video resources to concisely describe the transition process and introduce transitioning patients to the adult NAFLD clinic. After transfer, newly transitioned patients are followed closely within the first 2 years of transfer of care with frequent clinic visits and phone check‐ins to ensure successful integration into adult care. Finally, pediatric and adult NAFLD providers continue to collaborate and review and discuss patients. A Cochrane Review of four small studies (n = 238) concluded that transition of care interventions improved patients’ knowledge of their condition, as well as their confidence and self‐efficacy at 4‐ to 12‐month follow‐up time.34 With the development of a comprehensive transition of care model (Fig. 3), we hope to create a durable program with long‐lasting impacts on patients, as well as a reduction in NAFLD‐associated morbidity and mortality.

FIG 3.

NAFLD transition of care model. *TRAQ. †General Self‐Efficacy Scale. ✶Rosenberg Self‐Esteem Scale.

R.M.C. was supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01 AA026302 and P30 DK0503060.

Potential conflict of interest: R.M.C. has received grants from Intercept.

References

- 1.Younossi Z, Anstee QM, Marietti M, et al. Global burden of NAFLD and NASH: trends, predictions, risk factors and prevention. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018;15:11‐20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carr RM, Oranu A, Khungar V. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: pathophysiology and management. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 2016;45:639‐652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zimmermann E, Gamborg M, Holst C, et al. Body mass index in school‐aged children and the risk of routinely diagnosed non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease in adulthood: a prospective study based on the Copenhagen School Health Records Register. BMJ Open 2015;5:e006998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singh S, Allen AM, Wang Z, et al. Fibrosis progression in nonalcoholic fatty liver vs nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of paired‐biopsy studies. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;13:643‐654.e1‐9; quiz e39‐40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saiman Y, Hooks R, Carr RM. High‐risk groups for non‐alcoholic fatty liver and non‐alcoholic steatohepatitis development and progression. Curr Hepatol Rep 2020;19(Suppl. 4):1‐8. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blum RW, Garell D, Hodgman CH, et al. Transition from child‐centered to adult health‐care systems for adolescents with chronic conditions. A position paper of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. J Adolesc Health 1993;14:570‐576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Renedo A, Miles S, Chavravorty S, et al. Not being heard: barriers to high quality unplanned hospital care during young people's transition to adult services—evidence from 'this sickle cell life' research. BMC Health Serv Res 2019;19:876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krall J, Libman I, Siminerio L. The emerging adult with diabetes: Transitioning from pediatric to adult care. Pediatr Endocrinol Rev 2017;14(Suppl. 2):422‐428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.White PH, Cooley WC, Transitions Clinical Authoring Group , et al. Supporting the health care transition from adolescence to adulthood in the medical home. Pediatrics 2018;142(5):e20182587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.White P, Schmidt A, McManus M, et al. Incorporating Health Care Transition Services Into Preventive Care for Adolescents and Young Adults: A Toolkit for Clinicians. Washington, DC: Got Transition; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nakhla M, Daneman D, To T, et al. Transition to adult care for youths with diabetes mellitus: findings from a Universal Health Care System. Pediatrics 2009;124:e1134‐e1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sansom‐Daly UM, Lin M, Robertson EG, et al. Health literacy in adolescents and young adults: an updated review. J Adolescent Young Adult Oncol 2016;5:106‐118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Styne DM, Arslanian SA, Connor EL, et al. Pediatric obesity—assessment, treatment, and prevention: an Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2017;102:709‐757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kamath CC, Vickers KS, Ehrlich A, et al. Behavioral interventions to prevent childhood obesity: a systematic review and metaanalyses of randomized trials. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2008;93:4606‐4615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mencin AA, Loomba R, Lavine JE. Caring for children with NAFLD and navigating their care into adulthood. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;12:617‐628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Van Der Kruk J, Kortekaas F, Lucas C, et al. Obesity: a systematic review on parental involvement in long‐term European childhood weight control interventions with a nutritional focus. Obes Rev 2013;14:745‐760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tiggemann M. Body dissatisfaction and adolescent self‐esteem: prospective findings. Body Image 2005;2:129‐135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murray M, Dordevic AL, Bonham MP. Systematic review and meta‐analysis: the impact of multicomponent weight management interventions on self‐esteem in overweight and obese adolescents. J Pediatr Psychol 2017;42:379‐394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mahli A, Hellerbrand C. Alcohol and obesity: a dangerous association for fatty liver disease. Dig Dis 2016;34(Suppl. 1):32‐39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boekeloo BO, Novik MG, Bush E. Drinking to get drunk among incoming freshman college students. Am J Health Educ 2011;42:88‐95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boekeloo BO, Novik MG. Clinical approaches to improving alcohol education and counseling in adolescents and young adults. Adolesc Med State Art Rev 2011;22:631‐648, xiv. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Menon T, Afzali A. Inflammatory bowel disease: a practical path to transitioning from pediatric to adult care. Am J Gastroenterol 2019;114:1432‐1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schwartz LA, Tuchman LK, Hobbie WL, et al. A social‐ecological model of readiness for transition to adult‐oriented care for adolescents and young adults with chronic health conditions. Child Care Health Dev 2011;37:883‐895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wood DL, Sawicki GS, Miller MD, et al. The Transition Readiness Assessment Questionnaire (TRAQ): its factor structure, reliability, and validity. Acad Pediatr 2014;14:415‐422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang LF, Ho JS, Kennedy SE. A systematic review of the psychometric properties of transition readiness assessment tools in adolescents with chronic disease. BMC Pediatr 2014;14:4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Keefer L, Kiebles JL, Taft TH. The role of self‐efficacy in inflammatory bowel disease management: preliminary validation of a disease‐specific measure. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2011;17:614‐620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Opheim R, Moum B, Grimstad BT, et al. Self‐esteem in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Qual Life Res 2020;29:1939‐1846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Romppel M, Herrmann‐Lingen C, Wachter R, et al. A short form of the General Self‐Efficacy Scale (GSE‐6): Development, psychometric properties and validity in an intercultural non‐clinical sample and a sample of patients at risk for heart failure. Psychosoc Med 2013;10:Doc01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rosenberg, M.Society and the Adolescent Self‐Image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vajro P, Fischler B, Burra P, et al. The Health Care Transition of Youth With Liver Disease Into the Adult Health System: Position Paper From ESPGHAN and EASL. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2018;66:976‐990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Royal College of Nursing . Adolescent transition care: RCN guidance for nursing staff. London: : Royal College of Nursing; 2013. Available at: https://www.swswchd.co.uk/image/Clinical%20information/Transition/Adolescent%20Transition%20Care‐%20a%20guide%20for%20nurses%202013.pdf. Accessed December 17, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gray WN, Holbrook E, Dykes D, et al. Improving IBD transition, self‐management, and disease outcomes with an in‐clinic transition coordinator. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2019;69:194‐199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Draijer L, Benninga M, Koot B. Pediatric NAFLD: an overview and recent developments in diagnostics and treatment. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019;13:447‐461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Campbell F, Biggs K, Aldiss SK, et al. Transition of care for adolescents from paediatric services to adult health services. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016;4:CD009794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration . Summit Prevention Alliance (SAMHSA). Underage Drinking Prevention National Media Campaign. Available at: https://www.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/programs_campaigns/underage_drinking/we‐talked‐campaign.pdf. Published 2012. [Google Scholar]