Abstract

Immune checkpoint inhibitors can induce a durable response against a wide range of malignancies but may cause immune related adverse events. Immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) related hepatitis commonly shows lobular inflammation with histiocytes, vague to well-formed granulomas, fibrin ring granulomas, and endothelialitis. ICI cholangitis has also been reported and these patients may have bile duct dilatation or obstructive changes on imaging, and portal-based inflammation with duct injury. ICI related cholangitis is reportedly less responsive to steroids. The purpose of this study was to evaluate whether the pattern of inflammation on liver biopsy correlates with the pattern of LFT abnormalities, imaging findings, and responsiveness to steroids. Patient who developed elevated LFTs and underwent liver biopsy were identified. Clinical data was obtained from the electronic records. Liver biopsies were reviewed, and the pattern of inflammation was recorded as hepatitis, cholangitis, steatotic, or mild non-specific changes. Thirty-six liver biopsies had a hepatitis pattern of inflammation, including 16 patients with granulomas and 14 patients with endothelialitis. Sixteen patients had a cholangitic pattern, with portal-based inflammation. Four patients each had a pattern resembling fatty liver or mild nonspecific changes. The two commonest histologic patterns correlated with the pattern of LFT abnormalities. The cholangitic pattern was more likely to have bile duct dilatation or narrowing on liver imaging, and two patients were eventually diagnosed with bile duct obstruction from tumor. The pattern of inflammation, presence of granulomas, or presence of endothelialitis on liver biopsy did not predict response to steroids or the need for secondary immunosuppression. In conclusion, we found that a liver biopsy in patients on immune checkpoint inhibitors might not predict the need for steroids, the length of time that steroids is required, or the need for secondary immunosuppression. A cholangitic pattern may be seen when the pattern of LFTs is cholestatic, but this pattern can also be seen in competing drug reactions or bile duct obstruction from tumor.

Keywords: Immune checkpoint inhibitors, Immune related adverse events, hepatitis, cholangitis

Background:

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) targeting cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4), the programmed death receptor 1 (PD-1), and its ligand (PD-L1) can induce durable responses against a wide range of advanced malignancies, and have changed the therapeutic landscape in oncology.1 Immune dysregulation resulting in immune related adverse effects, however, remains a serious limitation with these therapies. Inflammation of the liver or immune related hepatitis occurs in 1–17% of patients on single agent immune checkpoint blockade, and in as many as a quarter of patients receiving combination therapy1–4 Some cases resolve without steroid therapy, but the majority requires corticosteroid therapy.5, 6 However, a subset of patients with immune related hepatitis are refractory to corticosteroids and require secondary immunosuppression. Although the impact of corticosteroids on antitumor responses has not been rigorously examined, it is likely that both corticosteroids and T-cell targeted immunosuppressive drugs have deleterious effects on antitumor responses based on retrospective analyses and on animal models.7–9 Therefore, the ability to guide treatment of checkpoint inhibitor hepatitis by characterizing histological patterns of liver injury and identifying patients who are most likely to respond to corticosteroids could have substantial clinical impact.

Most descriptions of ICI related liver injury have focused on ICI related hepatitis. Reports of the histopathologic features in these cases describe varying degrees of lobular hepatitis with numerous histiocytes, endothelialitis, loose or well-formed granulomas, fibrin ring granulomas, and varying degrees of portal inflammation.10–13 Rare cases have a pattern of fatty liver disease. Cases of ICI related cholangitis have also been described.12–19 These cases may show features that overlap with sclerosing cholangitis or bile duct obstruction clinically, but the pathologic features are less well described, other than portal-based mononuclear inflammation with duct injury and perhaps cholangiolitis. Patients with ICI related cholangitis seem to respond more poorly to steroid therapy.

In this study, we sought to address whether histologic pattern on liver biopsy plays a useful role in characterizing ICI related liver injury and predicting steroid responsiveness. We hypothesized that liver biopsies showing more portal based inflammation with duct injury were more likely to prove steroid resistant than cases of inflammatory lobular hepatitis.

Methods:

We conducted a retrospective review of 60 patients on immune checkpoint inhibitors who underwent liver biopsy for elevated liver function tests for a clinical concern for immune related hepatic toxicity from 2014–2018 at the Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, MA. The cohort was identified from a registry of patients treated with checkpoint inhibitors at the Massachusetts General Hospital and by a search of the surgical pathology files for cases of immune checkpoint inhibitor induced liver injury.

Histologic slides were reviewed by a single pathologist (JM) blinded to the clinical circumstances. H&E and trichrome stains were reviewed in all cases. The dimensions of the biopsy were recorded (length, number of portal tracts). The biopsies were classified as being predominantly hepatitic, cholangitic, steatotic, or as nonspecific mild changes. In addition, specific histologic parameters were assessed including portal inflammation density and cell type; duct changes; lobular injury degree and zone; presence, type, and location of granulomas; presence and location of endothelialitis; and the presence of steatosis, its zone, and association with lobular damage. Lobular injury was assessed as mild if it consisted of occasional or few foci of spotty lobular injury or singe cell necrosis, as moderate if there were either increased number or size of necroinflammatory foci, and as marked if there was confluent necrosis or zonal necrosis. We collected data from the electronic health records including age, gender, malignancy, pattern of liver enzyme abnormality, concurrent immune related adverse effects, administration and type of immunosuppression, and response to immunosuppression. Because many of these patients had numerous comorbidities and their LFTs often stayed mildly elevated, we defined resolution of the acute event as a sustained reduction to grade 1 or better of the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) for both transaminases and alkaline phosphate (< 3x ULN). If a patient did not achieve this endpoint before death, then the days to death was recorded for the purposes of calculating the median number of days to resolution. Steroid responsiveness was assessed by considering the need for steroids, the length of time of steroid use, and the need for secondary immunosuppression. Steroid use was categorized as no steroids, less than 1 month of steroids, 1–3 month of steroids, or greater than 3 months of steroids. If a patient was on steroids for a previously diagnosed condition, then whether steroid dose was increased was considered. We also collected date of death or date of last visit with a healthcare provider within the system. Follow up was censored at September 2019.

The study was approval by the Partners Healthcare Institutional Review Board.

Results:

Clinical features

Baseline characteristics of the 60 patients are shown in Table 1. Mean age at the time of liver biopsy was 61 years with a range of 28 to 85 years. There was a nearly even sex distribution, with 48% males, and 52% females. The most common malignancy was melanoma (68%). Other malignancies included small numbers of non-small cell lung cancer, gastrointestinal adenocarcinoma, pancreaticobiliary adenocarcinoma, gynecological malignancy, acute myeloid leukemia and cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. One third of patients had received combination anti-CTLA4 and anti-PD1, and another 8 patients received them sequentially. Fifteen (25%) received only anti-PD1 and only 4 received monotherapy anti-CTLA4. Thirteen patients received immune checkpoint inhibitors in combination with a non-checkpoint inhibitor agent. The median days on immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy prior to developing elevated LFTs was 78. The grade of LFT abnormality, according to the CTCAE, was most often grade 3 (73% of cases). The pattern of liver enzyme abnormality was hepatic (50%), cholestatic (40%) or mixed (10%).

Table 1:

Clinical features of 60 patients with abnormal liver tests in the setting of immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy

| Age range (mean) | 28–85 years (61 yr) |

|---|---|

| Male: Female | 29:31 |

| Malignancy | |

| Melanoma | 41 |

| Non-small cell lung carcinoma | 5 |

| Gastrointestinal adenocarcinoma | 4 |

| Pancreatobiliary adenocarcinoma | 3 |

| GYN malignancy | 2 |

| Glioblastoma | 3 |

| Acute myeloid leukemia | 1 |

| Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma | 1 |

| Immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy | |

| Anti-PD1 only | 15 |

| Anti-CTLA4 only | 4 |

| Combination Anti-PD1/Anti-CTLA4 | 20 |

| Sequential Anti-PD1 and Anti-CTLA4 | 8 |

| Checkpoint inhibitor with other therapy | 13 |

| Median days on ICI therapy (range) | 78 (12–917) |

| Grade of liver toxicity (CTCAE) | |

| 1 | 2 |

| 2 | 5 |

| 3 | 44 |

| 4 | 9 |

| Pattern of liver enzyme abnormality | |

| Hepatitic | 30 |

| Cholestatic | 24 |

| Mixed | 6 |

| Radiologic modalities (n=59) | |

| CT or PET CT only | 42 |

| Ultrasound and CT | 9 |

| Ultrasound only | 3 |

| MRCP or ERCP (with or without other modalities) | 5 |

| Radiologic findings (n=59) | |

| No relevant liver findings | 30 |

| Hepatic metastases | 15 |

| Bile duct dilatation or narrowing | 5 |

| Gallbladder thickening | 5 |

| Steatosis | 5 |

| Portal edema | 2 |

| Cirrhosis | 1 |

| Duration of steroids | |

| Not given | 8 |

| Less than 1 month | 19 |

| 1 to 3 months | 14 |

| Greater than 3 months* | 18 |

| Uncertain | 1 |

| Secondary immunosuppression* | 12 |

| Median days until resolution of LFTs (range) | 44 (2–302) |

| Outcome | |

| Alive without disease | 18 |

| Alive with disease | 18 |

| Dead of disease | 24 |

ICI: Immune checkpoint inhibitor; CTCAE: Common terminology criteria for adverse events; LFT: Liver Function Test

Two patients required steroids and secondary immunosuppression for concurrent Immune mediated colitis.

Radiologic imaging was performed for 59 of the 60 patients within the 3 months prior or one month after liver biopsy. Most patients had a CT scan only (n=37) and another 5 had PET CT. Nine patients had a CT scan and an ultrasound of the liver whereas 3 had only an ultrasound. Five patients had either an ERCP or an MRCP, of which one had both, one had an ultrasound, one had a CT scan, and one had all 4 modalities (ERCP, MRCP, CT scan, and ultrasound). Half of the patients had no relevant liver findings. Fourteen patients had hepatic metastases, ranging from 1 to numerous nodules. Gallbladder thickening was described in 5 patients (one with metastases). Nonspecific portal or gallbladder edema was reported in 2 patients. The radiologist commented on steatosis in 5 cases and cirrhosis in 1. Dilatation of the bile duct was described in 4 patients. One of these 4 patients with imaging features suggesting cholangitis. Two of the 4 patients with dilatation had liver metastases; one had irregularity of the duct lumen centrally with presumed obstruction due to portal nodes, whereas the other had mild narrowing at the bile duct confluence. One had mildly dilated bile duct without obstructive features. Finally, one patient with liver metastases showed severe short segment narrowing of the mid common bile duct.

Thirty-two patients were already on steroids when the biopsy was procured, either due to concurrent immune mediated adverse events or concern for ICI-related liver injury; of these, 9 were on steroids 5 days or less, 6 of whom were on steroids 1 or 2 days. Twenty-eight (47%) patients required either no steroids or less than 1 month of steroids; one of these patients was on chronic replacement steroids for adrenalectomy, but the dose was not increased as a result of the new diagnosis of ICI related hepatitis. In contrast, 18 patients required more than 3 months of immunosuppression and 12 (20%) patients required a second form of immunosuppression (although 2 had immune related colitis that also required these agents). The median days to resolution of the acute event with either resolution of LFT abnormalities or returning to grade 1 according to CTCAE was 52, with a range of 2 to 302 days.

Ultimately, 7 patients were felt to have competing explanation for the LFT abnormalities. In 5 patients, the timing of LFT abnormalities with cytotoxic chemotherapy administration raised the possibility that the LFT abnormalities were related to that agent rather than ICIs. In two patients with a portal-based cholangitic pattern on liver biopsy, the LFTs abnormalities were attributed to biliary obstruction by tumor.

At the time of censorship, 40% of patients were deceased from cancer. Of the remainder, half were alive without evidence of tumor on imaging and the other half were still undergoing treatment for their cancer.

Histologic features

The 60 liver biopsies ranged from 1.1 to 3.3 cm in length (mean 2.2 cm) and contained a median of 10.5 portal tracts (range 2 to 27). The histologic features of the biopsies are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Histologic features of liver biopsies in patients on immune checkpoint inhibitors (n = 60).

| Feature | n |

|---|---|

| Hepatitic pattern | 36 |

| Zonation of lobular injury | |

| Centrilobular predominance | 20 |

| Azonal | 10 |

| Panlobular | 4 |

| Periportal | 2 |

| Portal inflammation | |

| None to mild | 22 |

| Moderate | 14 |

| Prominent portal inflammatory cell composition | |

| Mononuclear cells with or without eosinophils | 21 |

| Mononuclear, +/− eosinophils, and pericholangitis | 13 |

| No significant inflammation | 2 |

| Granulomas | 16 |

| Loose histiocytic aggregates | 12 |

| Fibrin ring type | 6 |

| Well-formed | 2 |

| Endothelialitis | 14 |

| Central vein endothelialitis | 14 |

| Portal vein endothelialitis | 4 |

| Steatosis (mild to moderate) | 16 |

| Localized to lobular injury | 7 |

| Cholangiopathic pattern | 16 |

| Duct injury | 16 |

| Mild | 4 |

| Moderate | 11 |

| Marked | 1 |

| Portal inflammation | |

| Mild | 6 |

| Moderate | 10 |

| Prominent portal inflammatory cell composition | |

| Mononuclear cells with or without eosinophils | 2 |

| Mononuclear, +/− eosinophils, and pericholangitis | 3 |

| Predominantly neutrophil pericholangitis | 11 |

| Granulomas | 1 |

| Endothelialitis | 0 |

| Steatosis (mild to moderate) | 3 |

| Localized to lobular injury | 0 |

| Steatotic pattern | 4 |

| Mild steatosis | 1 |

| Moderate steatosis | 3 |

| Fibrosis or cirrhosis | 2 |

| Mild non-specific changes | 4 |

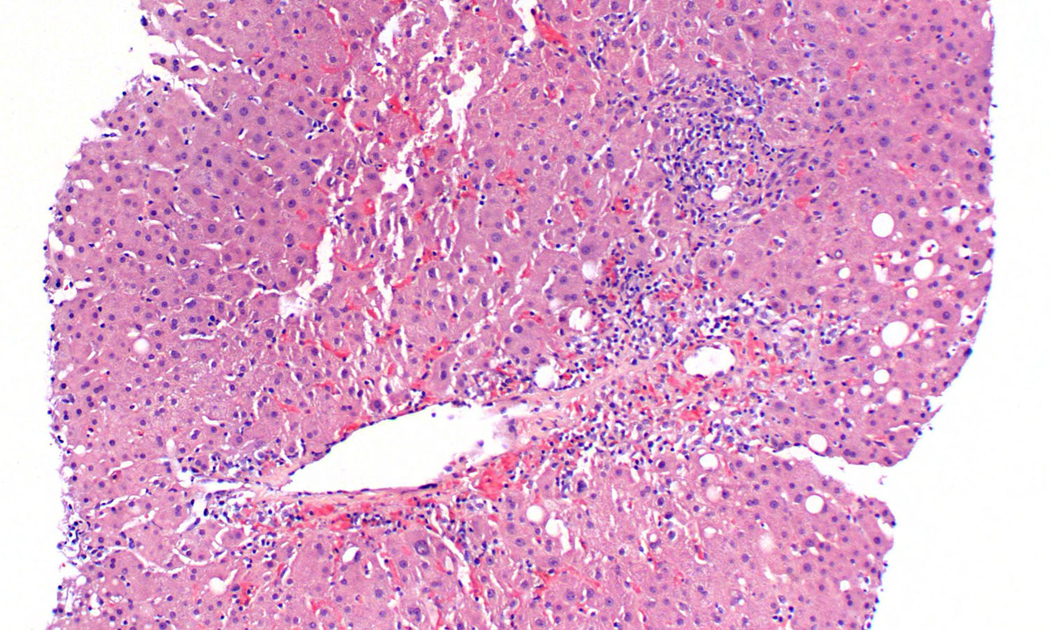

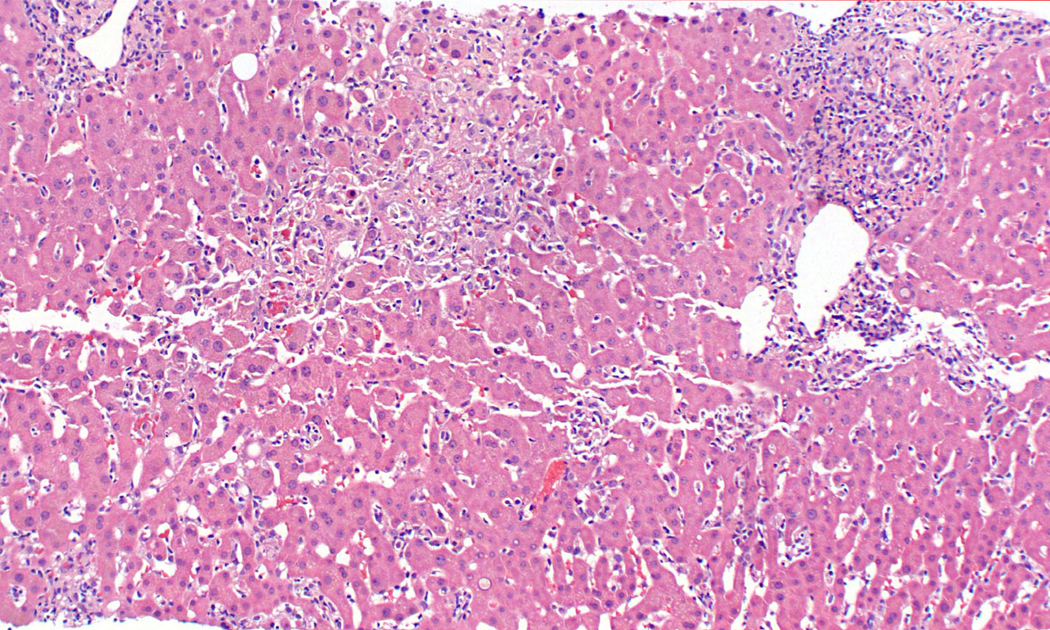

Thirty-six (60%) of the 60 biopsies showed a hepatitic pattern of injury. These biopsies showed lobular injury that was mild to moderate in most cases but marked in 6 cases. The zone of injury was typically centrilobular (20 cases; 56%) (Figure 1) and less often azonal (10 cases) or panlobular with or without zone 3 accentuation (4 cases) (Figure 2). Only 2 cases showed a predominantly zone 1 pattern of lobular injury. Ten cases showed mild lobular injury, 20 showed moderate lobular injury, and 6 had marked lobular injury. In all cases, the lobular inflammation comprised mostly histiocytes with admixed lymphocytes. Five cases each had scattered eosinophils or plasma cells in the lobular inflammatory infiltrate. Mild to moderate steatosis was present in 16 cases, but in 7 cases it was confined to areas of lobular inflammation and injury (Figure 3).

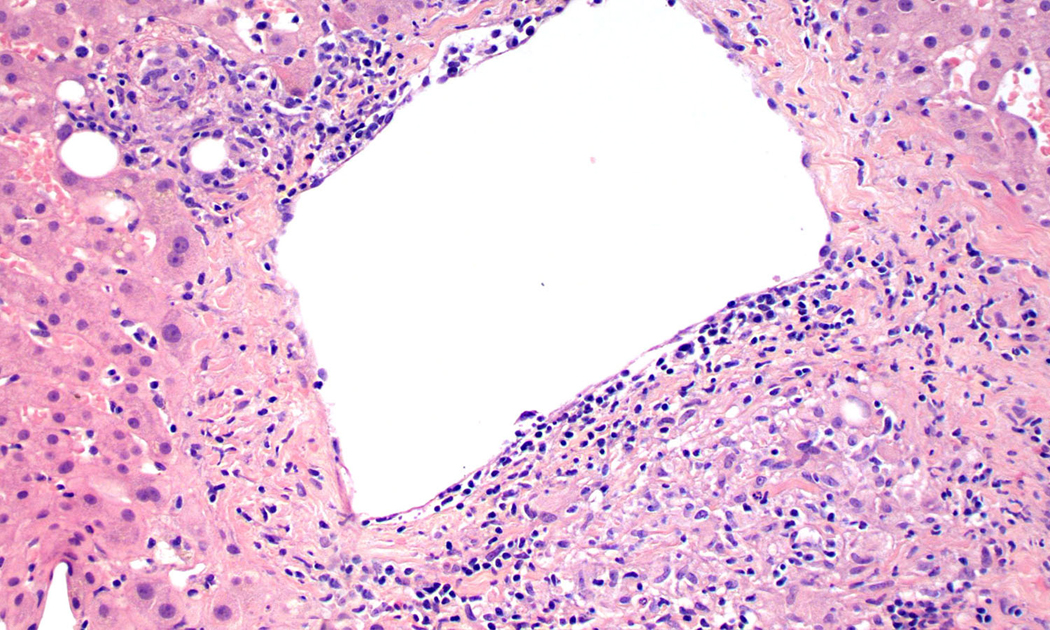

Figure 1.

Zone 3 hepatitis and necrosis with numerous histiocytes adjacent to an injured central vein. Note the mild steatosis co-localizing to the area of injury.

Figure 2.

Medium power view of a liver biopsy with panlobular inflammation, but with focal area of necrosis in the lobule. Portal tracts are mildly inflamed but the hepatitic component dominates the histologic picture.

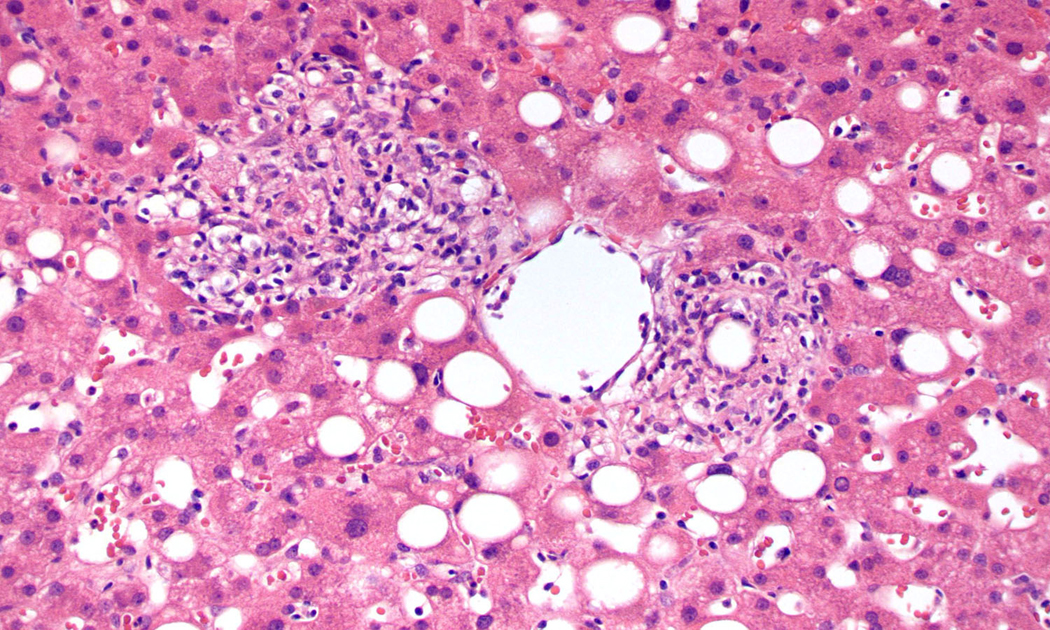

Figure 3.

Steatosis in an area of injury around a central vein with aggregates of histiocytes surrounding an injured vein. Note the lipid vacuole in the histiocyte aggregate, reminiscent of an early fibrin ring type granuloma.

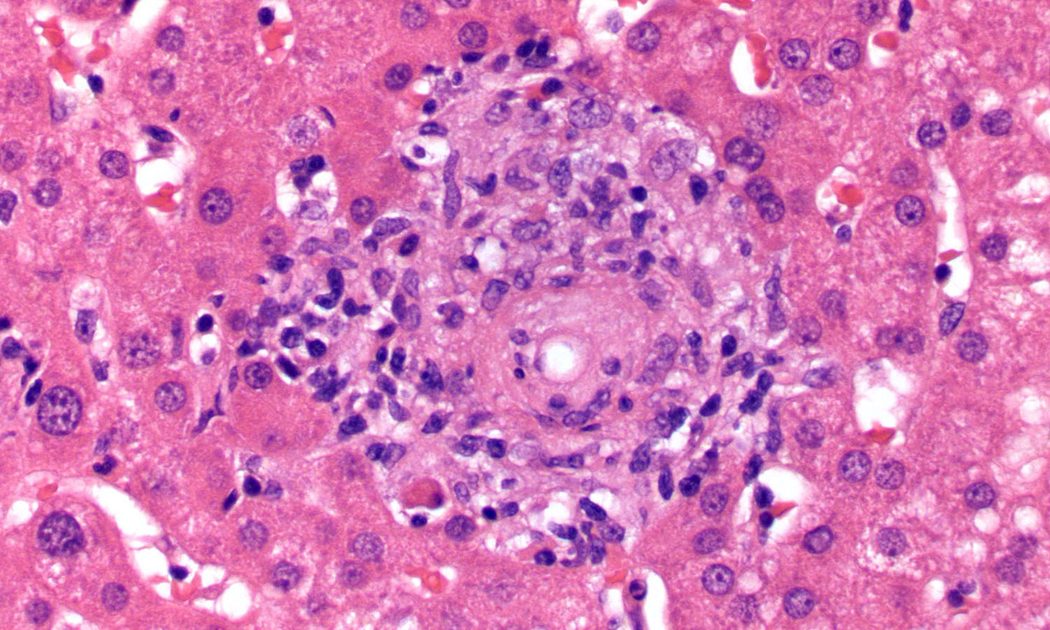

In the 36 hepatitic biopsies, portal inflammation was generally graded as mild (20 cases) but occasionally moderate (14 cases). The portal inflammatory cells mirrored the lobular inflammation, with a mixture of mononuclear cells with or without eosinophils being the most common inflammatory milieu (21 cases; 58%). However, in 13 cases, there was also mild duct injury with ductular reaction with neutrophils associated with the ductules (“pericholangitis”). In total, 16 cases (44%) had granulomas, which were generally loose aggregates of histiocytes, although 2 cases had well-formed granulomas and 6 cases had fibrin ring type granulomas (Figure 4). Granulomas were usually located in areas of lobular injury, but in 3 cases, portal granulomas were also present, and in another 3 cases, granulomas were present only in portal areas. Endothelialitis was noted in 14 cases (39%) (Figure 5), always involving central veins but occasionally portal veins as well (4 cases).

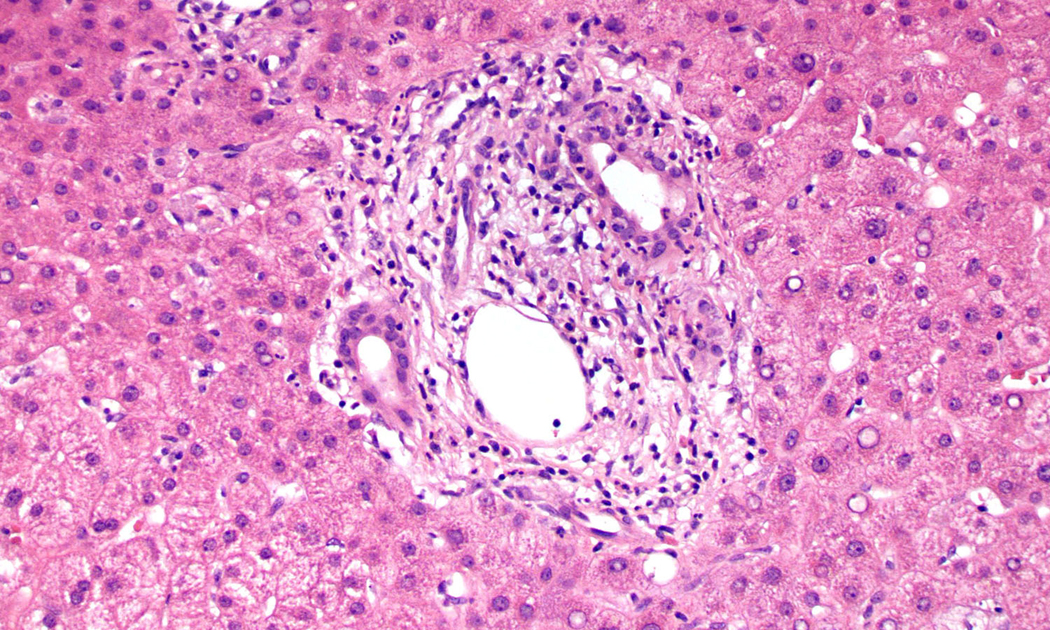

Figure 4.

A small fibrin ring granuloma, with a central lipid droplet surrounded by histiocytes, a thin ring of fibrin, and an outer layer of histiocytes.

Figure 5.

An hepatic vein surrounded by mononuclear inflammatory cells and granulomatous inflammation (lower right). Note the endothelialitis, with mononuclear cells undermining the endothelium at upper left and lower right.

A cholangitic pattern of injury was found in 16 cases (26%). These cases were characterized by only focal or mild lobular injury, and instead mild to marked duct injury often accompanied by mild portal edema (Figure 6). Portal inflammation was graded as mild to moderate, and usually (11 cases; 69%) contained conspicuous neutrophils around injured ducts (pericholangitis) (Figure 7). Only 2 cases showed portal inflammation that was composed of mononuclear cells with or without eosinophils. Three cases showed a mixed portal infiltrate that included mononuclear cells together with neutrophilic pericholangitis. Only one case in this group showed a granuloma adjacent to a portal tract and none showed endothelialitis. Mild to moderate steatosis was seen in 3 cases, but none showed a pattern of steatosis confined to areas of lobular injury.

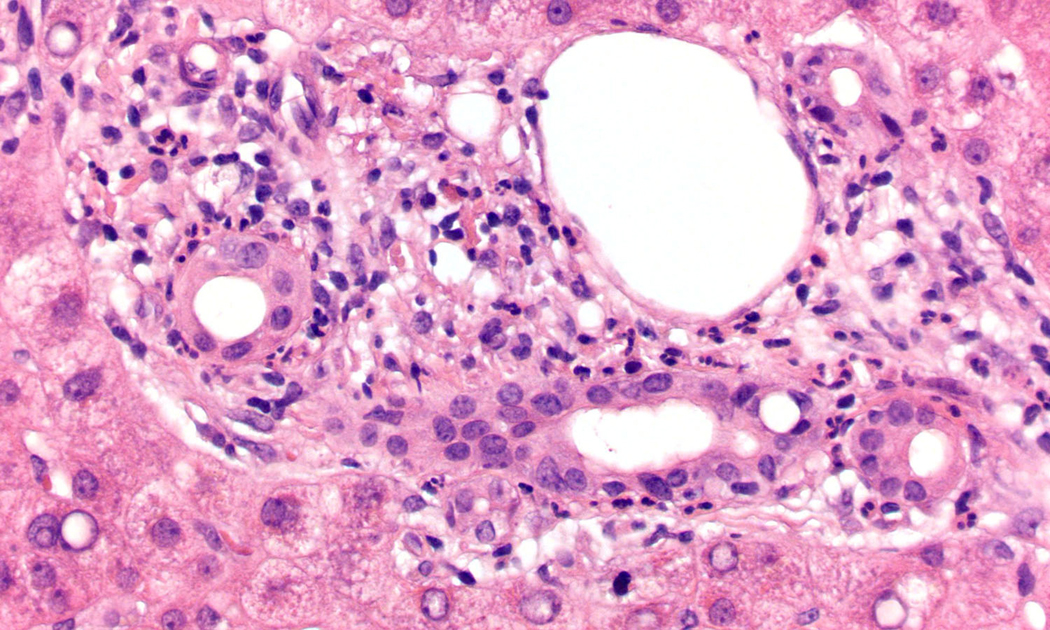

Figure 6.

A portal tract in a liver biopsy with a cholangitic pattern of injury, showing portal edema, bile duct injury, and scattered neutrophils around the injured ducts. Note the absence of a significant lobular inflammatory component.

Figure 7.

High power view of a portal tract in a liver biopsy with a cholangitic pattern of injury, showing portal edema, sparse inflammation with a predominantly neutrophilic infiltrate associated with injured bile ducts demonstrating nuclear disarray and focal nuclear dropout.

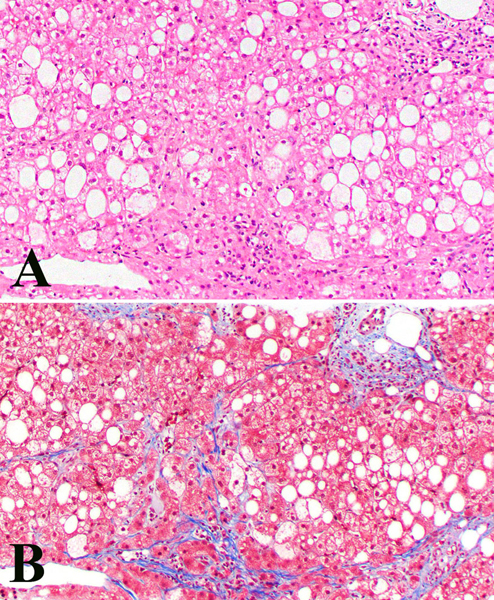

Four cases (7%) had a pattern that was dominated by steatosis or steatohepatitis. Mild lobular inflammation was noted in an azonal pattern in 2 of these cases that might represent superimposed ICI injury but was indistinguishable from the mild inflammation typically present in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (Figure 8); none of them had conspicuous zone 3 necrosis, granulomas, or endothelialitis. Portal inflammation was generally absent or mild and non-specific. One biopsy showed stage 2 of 4 fibrosis (modified Brunt stage) on Trichrome stain (Figure 8). The fourth biopsy was cirrhotic and resembled cirrhosis secondary to fatty liver disease.

Figure 8.

Medium power view of a liver biopsy demonstrating a steatohepatitic pattern of injury. There is moderate macrovesicular steatosis and hepatocyte ballooning. In this view, there is a focus of lytic necrosis with histiocytes, which may be due to immune checkpoint inhibitor injury, but in this context can look similar to usual non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Note that the portal tract (upper left) is not inflamed.

Four cases (7%) had mild and non-specific changes. These cases had absent or only focal lobular injury and absent or only focal mild portal inflammation. Two cases had focal or mild steatosis. None of these cases had granulomas or endothelialitis.

Clinicopathologic correlation

The clinicopathologic correlation among these cases is summarized in Table 3. There was no difference between the groups in terms of the number of patients on steroids at the time of biopsy. The pattern of liver enzyme abnormality correlated with the pathological pattern of injury for those with hepatitis and cholangitic patterns. In patients with a hepatitic pattern of liver injury, 80% had a hepatitic pattern of transaminitis with elevated AST and ALT. In patients with a cholangitic pattern, 75% had a cholestatic pattern of liver function tests with elevated alkaline phosphatase disproportionate to AST and ALT. Other histological patterns did not have predictive liver enzyme abnormalities.

Table 3:

Clinical features in 60 patients with suspected immune checkpoint inhibitor liver injury by histologic pattern

| Hepatitic Pattern (n=36) | Cholangitic pattern (n=16) | Steatotic pattern (n=4) | Mild and nonspecific changes (n=4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Checkpoint therapy | ||||

| Anti-PD1 only | 7 | 5 | 2 | 1 |

| Anti-CTLA4 only | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Combination ICI | 13 | 7 | 0 | 0 |

| Sequential ICI | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| ICI and other | 7 | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| Pattern of LFTs | ||||

| Hepatitic | 24 | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Cholestatic | 9 | 12 | 3 | 0 |

| Mixed | 3 | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| Grade of liver toxicity (CTCAE) | ||||

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 2 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 25 | 12 | 3 | 4 |

| 4 | 7 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Radiologic findings | ||||

| Normal | 22 | 5 | 3 | 1 |

| Hepatic metastases | 7 | 7 | 0 | 1 |

| Bile duct dilatation/narrowing | 1 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Gallbladder thickening | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Duration of steroids | ||||

| Not given | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| < 1 month | 10 | 6 | 1 | 2 |

| 1 to 3 months | 10 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| > 3 months | 12 | 4 | 1 | 1 |

| Uncertain | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Secondary immunosuppression | 8a | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Median days to resolution of LFTs (range) | 52 (2–160) | 47 (14–210) | 119 (59–302) | 26 (20–267) |

| Outcome | ||||

| Alive without disease | 11 | 4 | 2 | 1 |

| Alive with disease | 12 | 4 | 1 | 1 |

| Dead of disease | 13 | 8 | 1 | 2 |

| Alternative explanation for LFTs | 2b | 5c | 0 | 1b |

ICI: Immune checkpoint inhibitor; CTCAE: Common terminology criteria for adverse events; LFT: Liver Function Test

2 patients received infliximab for concurrent colitis

Received cytotoxic chemotherapy

3 patients received cytotoxic chemotherapy; 2 patients had biliary obstruction from tumor.

Among the 36 patients with a hepatitic pattern of liver inflammation, only one had an MRCP and none had ERCP. Twenty-two (61%) of the 36 had no radiologic hepatic findings including the patient who underwent MRCP. Seven patients had hepatic metastases. Only one patient had bile duct dilatation which was reportedly stable. Two patients in this group had gallbladder thickening reported on ultrasound only. Steatosis was noted in 4 patients.

In contrast, among the 16 patients with cholangitic pattern of inflammation on liver biopsy (15 of whom had radiologic studies performed), only 5 patients had normal imaging findings in the liver. Seven patients had hepatic metastases (p=0.47 compared to hepatitic group). Four patients had dilatation or narrowing of the bile duct (p = 0.009 compared to hepatitic group), 3 of whom also had metastases to the liver. Two patients had gallbladder wall thickening and 1 had portal edema.

Among the 4 patients with mild nonspecific inflammatory changes in the liver, one had gallbladder wall thickening and the others had normal hepatic imaging. Among the 4 patients with a steatotic pattern on liver biopsy, steatosis was mentioned in the CT scan report in only 1 case, which resembled steatohepatitis on biopsy. In the case with cirrhosis and steatosis on biopsy, only cirrhosis and gallstones were mentioned in the CT scan report, without mention of steatosis. The two other patients in the steatosis group included one with metastatic tumor and one with normal imaging.

There was no clear association between pattern of liver injury and requirement for immunosuppression, time to resolution, or need for secondary immunosuppression. In the hepatitic group, there was no statistically significant association between the degree of lobular damage and the CTCAE grade of LFT elevation, the need for or length of time on steroids, or the need to add secondary immunosuppression (data now shown). This lack of a significant association between lobular damage and other parameters remained true when only patients who were not on steroids at the time of biopsy were evaluated, although the small number of patients in some groups may limit our ability to detect weak associations. Also, the presence or absence of granulomas or of endothelialitis did not predict longer time requirements for steroids or the need for secondary immunosuppression. Patients with a mild or non-specific pattern of injury had the shortest median time to resolution, despite one patient failing to achieve this endpoint before demise; however, even after excluding this one patient, the mean days to resolution between this group and the combined hepatitis and cholangitis groups was not statistically significantly different (p = 0.09).

Discussion:

In this study, we found that a hepatitic pattern of injury was the most common pattern of checkpoint related liver injury, followed by a portal-based cholangitic pattern and steatotic pattern. The pattern of liver function test abnormality correlates with the findings on liver biopsy, with a predominantly hepatitic or cholestatic pattern of LFT abnormalities corresponding to a hepatitic or cholangitic pattern of inflammation, respectively. We found that the pattern of liver injury (whether hepatitic or cholangitic) did not predict response to steroid therapy or the need for secondary immunosuppression, but biopsies with only mild and nonspecific changes might be informative to suggest rapid time to resolution. Among cases with a hepatitic pattern on liver biopsy, the degree of lobular injury did not correlate with the degree of steroid responsiveness. Neither endothelialitis nor granulomas predicted the length of time needed on steroids or the need for secondary immunosuppression.

The histologic features of ICI-induced hepatitis have been described as a lobular, panlobular, or zone 3 hepatitis with numerous histiocytes, sometimes forming loose, well-formed or fibrin ring granulomas, endothelialitis, and varying portal inflammation.10–13 In our series, we found that a hepatitic pattern of injury with predominant lobular involvement accounted for 60% of the liver biopsies in patients on ICIs with elevated LFTs. Twenty eight of these patients had a treatment regimen that included a PD-1 inhibitor. Slightly over half of these biopsies (56%) showed a centrilobular pattern of injury and nearly a third (28%) had an azonal pattern of lobular injury. Only 4 of 36 (11%) had a panlobular pattern of injury, and 2 of 36 (6%) had a largely periportal pattern of lobular injury.

In the hepatitic biopsies, although lobular injury was a prominent finding, portal inflammation was also usually present, and while it was mild in most cases, it was moderate in 39%. Most cases showed portal mononuclear inflammation with scattered eosinophils but 13 (36%) of the 36 biopsies showed neutrophils with ductular reaction together with mononuclear cells and eosinophils. None showed predominantly neutrophils in portal tracts. In total, 16 hepatitic cases had granulomas, including fibrin ring granulomas in 6/36 and well-formed granulomas in 2 cases. Endothelialitis was present in 14 cases, with 4 showing both central vein and portal vein involvement. Steatosis was a common finding in this group, present in 44% of cases. In 7 cases, steatosis was localized to the areas of injury, a finding that was noted in prior cases in the literature,11 and suggesting that in some cases, steatosis is a component of the lobular damage rather than background steatosis. In our practice, we find that biopsies that fell within this pattern are the most specific appearing, and many are specifically diagnosed as ICI-related hepatitis. Only 2 of these patients had a competing explanation for their elevated LFTs (both cytotoxic chemotherapy administration).

The second most common pattern of inflammation in patients on ICI with elevated LFTs was portal-based inflammation without a lobular component (cholangitis pattern). Ten of these patients were given nivolumab alone or in combination with ipilimumab, and the others were given either pembrolizumab (5 cases) or atezolizumab (1 case). In our cases, this group was more likely to have imaging findings including bile duct dilatation or narrowing, although it should be noted that 3 of the 4 patients with bile duct changes also had hepatic metastases, and hepatic metastases were more common in this group relative to the hepatitis group; therefore, compression of the duct by metastatic tumor may be a cause of some of these changes. In fact, in 2 of these patients, the LFT abnormalities were ultimately attributed to bile duct obstruction from tumor rather than checkpoint inhibitors. Gallbladder wall thickening was not significantly different from the hepatitis group.

In the cholangitis biopsies, bile duct injury and neutrophilic pericholangitis were the dominant findings. In fact, 11 (69%) out of 16 biopsies in this group showed portal inflammation that was dominated by neutrophils around ducts or ductules. Granulomas were rare in this group and endothelialitis was not seen. Other reports describe cholangitis in ICI related liver injury, particularly with anti-PD-1 therapy. The cholangitis in ICI related liver injury may affect the large ducts or the small ducts. When large ducts are affected, there may be imaging findings, including sclerosing cholangitis-like changes (irregular caliber, stenoses, or thickening of the intrahepatic or proximal bile ducts),13–16 dilatation or prominence of the extrahepatic bile ducts without a clear obstruction,17, 18 obstruction of the distal common bile duct,20 and thickening of the gallbladder.15, 17, 20 Cases of large duct cholangitis secondary to nivolumab in which the bile duct was biopsied showed infiltration of the duct epithelium by either mixed inflammation or by neutrophils.13, 18, 20 Histologic findings in liver biopsies in ICI related cholangitis have included a predominantly portal based mononuclear or mixed infiltrate with duct injury, intraepithelial lymphocytes in duct epithelium, mild periportal necrosis, ductular reaction, biliary type interface activity, and cholangiolitis.12–14, 19 In addition, there have been cases of vanishing bile duct syndrome in ICI related duct injury.21

In the cases reported in the literature, ICI related cholangitis has been more resistant to steroid therapy. We did not find this in our series; in our set of patients, this pattern on liver biopsy did not predict a longer time requirement for steroids or need for secondary immunosuppression. This discrepancy may be due to the fact that our cases are best classified as small duct disease. Perhaps large duct disease, with radiographic evidence of sclerosing cholangitis or duct obstruction, would portend less response to steroids.

In our practice, a cholangitic portal-based pattern of liver injury generates a differential diagnosis that includes ICI related cholangitis, but also other drug reactions, bile duct obstruction, and, depending on clinical circumstances, other causes of portal neutrophilic inflammation associated with ducts such as sepsis. Ultimately, in 2 of our cases, the LFTs were attributed to duct obstruction from tumor rather than ICIs, but the histologic features in those cases were indistinguishable from the cases of ICI related cholangitis, emphasizing that portal based inflammation with a predominance of neutrophils and injured bile ducts is not specific for ICI related liver injury.

In 4 patients, the pattern of injury in the liver was steatotic, which was described in a prior series.10 In 2 of those cases, there was either fibrosis or cirrhosis, indicating that the fatty liver was a chronic underlying issue in these patients. In these cases, it is difficult to explain the abrupt rise in LFTs based on the histology, but exacerbation of fatty liver disease may be a factor. A similar number of patients had very mild and nonspecific changes in their liver biopsies; not surprisingly, this pattern was associated with the shortest time to resolution of LFTs.

A limitation of this study is its retrospective nature. In our practice, we advocate for patients to ideally undergo biopsy before treatment with steroids is implemented, but this is not always done due to concerns for severe liver injury, difficulty in arranging a liver biopsy in a timely manner, or concomitant immune mediate adverse events. Obviously, steroid use may affect the inflammatory pattern in a liver biopsy. In our cases, we were unable to detect significant differences between the patients who were and were not on steroids at the time of their biopsy. However, small numbers of patients in some groups create limitations for detecting statistical differences, and prospective analyses with early biopsy prior to initiation of any immune suppression will likely be necessary before we can make definitive conclusions.

In conclusion, in this retrospective study, we found that a liver biopsy in patients on immune checkpoint inhibitors can provide information on the pattern of injury, but that does not predict the need for steroids, the length of time that steroids is required, or the need for secondary immunosuppression. The degree of lobular injury did not correlate with the level of LFT abnormality or the need for steroids or secondary immunosuppression among patients with a hepatitic pattern of injury. Specific features such as granulomas and endothelialitis did not predict steroid responsiveness. A portal-based inflammatory process with duct injury and neutrophilic pericholangitis may be seen, particularly when the pattern of LFTs is cholestatic, but this pattern should alert pathologists to offer a broader differential, including bile duct obstruction from tumor, especially in patients with known hepatic metastases on imaging. Biopsies with only minimal changes might predict a short course of immunosuppression. Steatotic patterns of injury may represent exacerbation of pre-existing fatty liver disease, especially in the presence of fibrosis or cirrhosis.

References

- 1.Hodi FS, O’Day SJ, McDermott DF, et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med 2010;363:711–723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kurashima Y, Kiyono H. Mucosal Ecological Network of Epithelium and Immune Cells for Gut Homeostasis and Tissue Healing. Annu Rev Immunol 2017;35:119–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eggermont AM, Chiarion-Sileni V, Grob JJ, et al. Prolonged Survival in Stage III Melanoma with Ipilimumab Adjuvant Therapy. N Engl J Med 2016;375:1845–1855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robert C, Thomas L, Bondarenko I, et al. Ipilimumab plus dacarbazine for previously untreated metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med 2011;364:2517–2526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reddy HG, Schneider BJ, Tai AW. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor-Associated Colitis and Hepatitis. Clin Transl Gastroenterol 2018;9:180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haanen J, Carbonnel F, Robert C, et al. Management of toxicities from immunotherapy: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 2018;29:iv264–iv266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Faje AT, Lawrence D, Flaherty K, et al. High-dose glucocorticoids for the treatment of ipilimumab-induced hypophysitis is associated with reduced survival in patients with melanoma. Cancer 2018;124:3706–3714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pauken KE, Dougan M, Rose NR, et al. Adverse Events Following Cancer Immunotherapy: Obstacles and Opportunities. Trends Immunol 2019;40:511–523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arbour KC, Mezquita L, Long N, et al. Impact of Baseline Steroids on Efficacy of Programmed Cell Death-1 and Programmed Death-Ligand 1 Blockade in Patients With Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. J Clin Oncol 2018;36:2872–2878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johncilla M, Misdraji J, Pratt DS, et al. Ipilimumab-associated hepatitis: Clinicopathologic characterization in a series of 11 cases. The American Journal of Surgical Pathology 2015;39:1075–1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Everett J, Srivastava A, Misdraji J. Fibrin Ring Granulomas in Checkpoint Inhibitor-induced Hepatitis. The American journal of surgical pathology 2017;41:134–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zen Y, Yeh MM. Hepatotoxicity of immune checkpoint inhibitors: a histology study of seven cases in comparison with autoimmune hepatitis and idiosyncratic drug-induced liver injury. Mod Pathol 2018;31:965–973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zen Y, Chen YY, Jeng YM, et al. Immune-related adverse reactions in the hepatobiliary system: second-generation check-point inhibitors highlight diverse histological changes. Histopathology 2020;76:470–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hamoir C, de Vos M, Clinckart F, et al. Hepatobiliary and Pancreatic: Nivolumab-related cholangiopathy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018;33:1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kono M, Sakurai T, Okamoto K, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Chemotherapy Following Anti-PD-1 Antibody Therapy for Gastric Cancer: A Case of Sclerosing Cholangitis. Intern Med 2019;58:1263–1266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gelsomino F, Vitale G, Ardizzoni A. A case of nivolumab-related cholangitis and literature review: how to look for the right tools for a correct diagnosis of this rare immune-related adverse event. Invest New Drugs 2018;36:144–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kawakami H, Tanizaki J, Tanaka K, et al. Imaging and clinicopathological features of nivolumab-related cholangitis in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Invest New Drugs 2017;35:529–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuraoka N, Hara K, Terai S, et al. Peroral cholangioscopy of nivolumab-related (induced) ulcerative cholangitis in a patient with non-small cell lung cancer. Endoscopy 2018;50:E259–E261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gelsomino F, Vitale G, D’Errico A, et al. Nivolumab-induced cholangitic liver disease: a novel form of serious liver injury. Ann Oncol 2017;28:671–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kashima J, Okuma Y, Shimizuguchi R, et al. Bile duct obstruction in a patient treated with nivolumab as second-line chemotherapy for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a case report. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2018;67:61–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Doherty GJ, Duckworth AM, Davies SE, et al. Severe steroid-resistant anti-PD1 T-cell checkpoint inhibitor-induced hepatotoxicity driven by biliary injury. ESMO Open 2017;2:e000268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]