Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Lingual squamous cell carcinoma (LSCC) is an aggressive malignancy that carries significant mortality risk and the potential for cardiac metastasis. The authors performed a systematic review designed to characterize disease progression of LSCC cardiac metastasis by evaluating patient demographics, characteristics, management, and clinical outcomes.

METHODS

Two authors independently screened articles in Embase, PubMed, and Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews up until December 2019 for study eligibility. Demographic data, patient symptomatology, imaging findings, management strategies, and patient outcomes were obtained and analyzed. The Oxford Centre for Evidence Based Medicine (OCEBM) Levels of Evidence categorization was implemented to determine the quality of studies selected in this review.

RESULTS

From this review, a total of 28 studies met inclusion criteria and received an OCEBM Level 4 evidence designation. Thirty-one patients were identified with cardiac metastasis from LSCC. Shortness of breath (29.0%) and chest pain (29.0%) were the most common presenting symptoms, and pericardial effusion (29.2%) and right ventricular outflow tract obstruction (25.0%) were the predominant echocardiogram findings. Cardiac metastases most often presented in the right ventricle (56.7%), followed by the left ventricle (43.3%). Palliative intervention (68.2%) or chemotherapy (40.9%) were typically implemented as treatments. All sample patients expired within one year of metastatic cancer diagnosis in cases that reported mortality outcomes.

CONCLUSIONS

Patients presenting with shortness of breath, tachycardia, and a history of squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue may indicate evaluation for LSCC cardiac metastasis. Although LSCC cardiac metastases typically favor the right and left ventricles, they are not exclusive to these sites. Palliative care may be indicated as treatment due to high mortality and overall poor outcomes from current interventions.

Keywords: cancer, cardiac metastasis, squamous cell carcinoma, tongue

INTRODUCTION

Cancer of the oropharynx (i.e., part of the throat at the back of the mouth behind the oral cavity) is one of the most frequently diagnosed cancers worldwide, representing the seventh largest incidence burden of new cancer in men and fourteenth amongst women.1–4 Lingual squamous cell carcinoma (LSCC) accounts for approximately 3.0% of oropharyngeal carcinomas,4 typically affecting male smokers older than 45 years of age.5,6 Although LSCC is rare, global rates have been shown to increase from 0.4% to 3.3% during recent years, and there is an increasing incidence in the young female population.7

LSCC primarily confers metastatic risk to the lungs, heart, and bones, although it has demonstrated the ability to metastasize to nearly all organ systems.3 As a result, presentations of metastatic LSCC are exceptionally variable and contingent on the site of metastasis. It has also been estimated that metastatic LSCC will show cardiac involvement between 1.5% to 24.0% of all cases.8

Most cases of LSCC cardiac metastasis are detected post-mortem, although ante-mortem cases can be detected when symptomatic.9 Symptoms of cardiac metastasis are relatively non-specific, but can include fatigue, chest pain, orthopnea, and leg edema.8 To date, characterization of metastatic LSCC of the heart has been limited to case reports and case series.

Purpose of Review

The purpose of this systematic review was to examine the patient demographics, characteristics, management, treatments, complications, and outcomes associated with LSCC cardiac metastases.

METHODS

This systematic review was completed in 2020 using the Preferred Reporting Systems for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines.10 Preliminary searches were performed using data from PubMed, Embase, and Cochrane Library comprising studies dated through December 2019. The primary search included the keywords “tongue cancer”, “lingual cancer”, “buccal cancer”, and “metastasis”. A secondary search was done using the keywords “cardiac metastasis” and “tongue”.

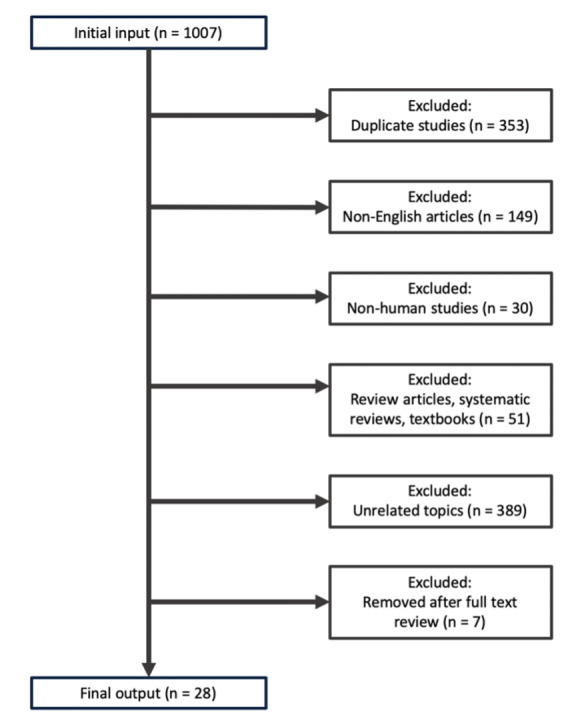

The selected articles were combined to create a composite list of 1,007 studies to review. Studies that included review articles, textbooks, non-human subjects, non-English language, or unrelated topics were excluded. The inclusion criteria utilized in this systematic review are outlined in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Literature selection criteria. Literature selection methodology was constructed using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA).

Study selection and data extraction

Each article within the composite list of studies was reviewed for inclusion by two independent authors (CK, TN). The titles and abstracts were screened for information regarding metastatic LSCC presentation, diagnosis, and management. Relevant articles were further examined via full text review and a finalized list was generated for in-depth analysis (Supplemental Table 1). A total of 31 cases of LSCC cardiac metastasis within 28 studies met inclusion criteria and were comprehensively reviewed (Supplemental Table 2).

All 28 selected studies had obtained an Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine (OCEBM) evidence categorization of Level 4 given their status as either a case report or case series. Relevant patient demographics, symptoms, LSCC history, clinical findings, treatment strategies, complications, and outcomes were collected. It was assumed death had occurred within six months if patients underwent palliative care.

RESULTS

Sample Demographics and Exposure

An analysis of demographic characteristics of patients in selected articles included 19 (61.3%) males and 12 (38.7%) females with a mean age of 53.6 (SD = 12.9) years ranging from 23.0 - 77.0 years. LSCC cardiac metastasis presented primarily between the ages of 40 - 69 (Figure 2). Average time from primary cancer diagnosis to cardiac metastasis identification was 2.2 (SD = 2.6) years, ranging from 0.2 - 11.0 years. Ten (32.3%) patients reported significant tobacco exposure and five (16.1%) patients admitted to alcohol use.

Figure 2. LSCC age distribution by decade of life.

Presenting Symptoms and Physical Examination

Chest pain and shortness of breath were the most common causes of initial presentation with nine (29.0%) cases, followed by five (16.1%) cases with syncope, four (12.9%) cases with weight loss, four (12.9%) cases with fever, four (12.9%) cases with oral mass, three (9.7%) cases with lymphadenopathy (i.e., enlargement of lymph nodes > or = 1), and three (9.7%) cases with oral pain. Other symptoms included two (6.5%) patients with edema, two (6.5%) patients with hemoptysis (i.e., blood mixed in sputum), and two (6.5%) patients with palpitations. A complete outline of patient symptomatology is depicted in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Symptomatology of LCCC Patients diagnosed with cardiac metastasis.

Abbreviations: CP = chest pain, E = edema, F = fever, H = hemoptysis, L = lymphadenopathy, OM = oral mass, OP = oral pain, P = palpitations, S = syncope, SOB = shortness of breath, WL = weight loss.

The most common physical examination findings included four (12.9%) patients with hypotension, four (12.9%) patients with fever, three (9.7%) patients with tachycardia, and three (9.7%) patients with cardiac murmur.

Cardiac Evaluation

Electrocardiogram (ECG) testing was reported in 19 (61.3%) patients, which found the most common abnormality to be ST-segment elevation in 12 (63.2%) patients (Supplemental Table 3). Other commonly reported ECG findings included arrhythmia in six (31.6%) patients, bundle branch block in four (21.1%) patients, t-wave inversion in four (21.1%) patients, and tachycardia in three (15.8%) patients. Troponin testing was reported in 31 patients with positive troponin elevations occurring in five (16.1%) cases.

Imaging Modalities and Findings

The most utilized imaging modalities were echocardiogram and computed tomography (CT) both occurring in 24 (77.4%) cases, followed by positron emission tomography (PET) in 12 (38.7%) cases, and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMRI) in nine (29.0%) cases (Figure 4). On echocardiogram, the most common finding was pericardial effusion occurring in seven (29.2%) cases, followed by six (25.0%) cases with right ventricular outflow tract obstruction, three (12.5%) cases with valvular dysfunction, and two (8.3%) cases with wall motion abnormality (i.e., kinetic alterations in the cardiac wall motion taking place during the cardiac cycle) (Supplemental Table 3).

Figure 4: Utilization of diagnostic modalities. Four major imaging modalities were used to assist with the diagnosis of cardiac metastasis from LSCC.

Abbreviations: CMRI = cardiac magnetic resonance imaging; CT = computed tomography; Echo = echocardiogram; PET = positron emission tomography.

Of the patients with reported valvular dysfunction, two (66.6%) cases had impaired function of the pulmonic valve and one (33.3%) case had impaired tricuspid valve function. In the 12 patients who underwent PET scan, extra-cardiac uptake was most reported in the lung with five (41.7%) reported cases, followed by two (16.7%) cases in the bone, two (16.7%) cases in the liver, and one (8.3%) case in the muscle. The number of extra-cardiac foci ranged from 0.0 - 7.0 sites with an average of 1.8 (SD = 1.7) sites.

Location of Cardiac Metastasis

Out of 31 selected cases, 27 disclosed the number of cardiac metastases. Number of distinct cardiac metastases ranged from 1.0 - 4.0, with an average of 1.5 (SD = 0.8) metastases. Most cases presented with one individual mass in 17 (63.0%) cases, followed by two masses in 8 (29.6%) cases, and three or more masses in 2 (7.4%) cases.

The locations of metastases were distinctly specified in 30 of 31 cases. Right-sided metastases were most common with 23 (76.7%) instances, followed by 15 (50.0%) instances of left-sided metastases, and 11 (36.7%) instances of septal metastases. The most common location of metastasis was the right ventricle with 17 (56.7%) instances, followed by the left ventricle in 13 (43.3%) instances, interventricular septum in nine (30.0%) instances, and right atrium in six (20.0%) instances. This analysis also revealed eight (26.7%) patients with pericardial metastasis. Locational distinctions are further defined in Supplemental Table 2 and Supplemental Table 4.

Patient Management

Primary LSCC treatment strategies were discussed in 29 (93.5%) of 31 total cases. The most frequently reported primary treatment was surgery in 25 (86.2%) cases, followed closely by radiotherapy in 23 (79.3%) cases, and chemotherapy in 13 (44.8%) cases. The most common surgical intervention was neck dissection in eight (32.0%) cases, followed by partial glossectomy (i.e., removal of tongue tissue) in six (24.0%) cases, and hemi-mandibulectomy (i.e., removal of part of or all of the hemimandible, or one side or half of the mandible) in two (8.0%) cases.

Treatment strategies for metastatic lesions were described in 22 (71.0%) of 31 cases which included chemotherapy, surgical intervention, radiotherapy, immunotherapy, and palliative treatment. Given the poor prognosis, the most elected therapy was palliative treatment in 15 (68.2%) instances. Chemotherapy was the next most common intervention in nine (40.9%) instances, followed by surgery in four (18.2%) instances, radiotherapy in three (13.6%) instances, and immunotherapy in one (4.5%) instance.

Of those treated with chemotherapy, the most used agents were cisplatin in three (33.3%) cases and 5-fluorouracil in three (33.3%) cases. Other chemotherapeutics included bleomycin, etoposide, and methotrexate. Of note, immunotherapy with pembrolizumab was utilized in only one (4.5%) case. Individual treatments are further outlined in Supplemental Table 2.

Patient Outcomes

Twenty-two total cases (70.9%) reported outcome results, of which none showed remission of LSCC cardiac metastasis. Death was reported in 20 (90.9%) cases with two (9.1%) cases reporting palliative care and assumed death in less than six months. Of the 14 cases to report death within a known period, 9 (64.3%) reported death within one month of LSCC cardiac metastasis diagnosis.

Cause of death was listed in 16 cases which included eight (50.0%) deaths from cardiac metastasis, two (12.5%) deaths from sepsis, two (12.5%) deaths from arrhythmia/sudden cardiac death, one (6.3%) death from heart failure, one (6.3%) death from hemoptysis, one (6.3%) death from death in sleep, and one (6.3%) death from tumor embolism. Four (25.0%) cases had cardiac-related deaths, while 12 (75.0%) cases had tumor-specific or non-cardiac deaths.

DISCUSSION

Primary squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) accounts for more than 90% of cancer diagnoses within the head and neck region and is the sixth most common cancer overall by incidence.11 Classically, LSCC displays a predilection for the elderly male population,12 although it can present more aggressively in younger individuals with higher rates of metastasis and mortality.13 Recent research also suggests that young Caucasian females are demonstrating an overall increase in disease incidence.7 In this study, the majority of patients (51.6%) were males aged 40-69 years old, consistent with the typical presentation of LSCC.

In addition to age and sex, modifiable factors such as tobacco and alcohol exposure carry significant independent and synergistic risks for LSCC.14,15 Exposure to viral infections such as Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) and human papilloma virus (HPV) have also been associated with LSCC.16,17 In this systematic review, most cases failed to describe previous history of alcohol or tobacco use and no cases reported previous EBV or HPV exposure.

Cardiac metastasis of LSCC is typically diagnosed post-mortem on autopsy due to limited specific clinical manifestations.18 When diagnosed ante-mortem, patients may present with nonspecific cardiac symptoms such as chest pain, shortness of breath, and palpitations.19 In this systematic review, patients commonly demonstrated nonspecific cardiac symptoms such as chest pain, shortness of breath, syncope, and weight loss. Of these symptoms, chest pain and shortness of breath were the most prevalent (29.0% of cases), followed by syncope, then weight loss. Common physical exam findings were generally nonspecific (e.g., hypotension, fever, tachycardia, and cardiac murmur) in the selected articles.

Primary SCC originating from the head and neck with cardiac metastasis is extremely rare, as most cardiac neoplasms occur secondarily from areas such as the breast, lung, and esophagus.20 When present, cardiac metastasis most frequently occurs in the pericardium, followed by the myocardium, epicardium, endocardium, and intracavitary region.21

In this systematic review, right-sided cardiac metastasis was more common than left-sided metastasis, and ventricular involvement was more common than atrial involvement. The examined cases demonstrated a higher incidence of intracardiac tumors compared to pericardial tumors. Possible explanations for these findings relate to the hematogenous spread of squamous cell neoplasms through the coronary arteries, direct contiguous extension, and retrograde lymphatic flow.22

Since symptomatic presentations of LSCC cardiac metastasis can be highly variable, imaging studies are needed to assess the extent of cardiac involvement. First-line imaging for cardiac metastasis of LSCC begins with an echocardiogram due to its wide availability and lack of radiation.23 When there are no contraindications, contrast-enhanced CT scans are the diagnostic imaging modality of choice, as non-contrast CT scans may fail to identify small myocardial masses.24 If further imaging is indicated due to inconclusive CT results, CMRI is considered the most definitive imaging modality for evaluation of myocardial metastasis and delineation of intracardiac tumor thrombi.23

Cervical lymph node involvement is a strong prognostic factor when delineating patient outcomes for LSCC.25 Five-year survival rates for patients with oral SCC lymph node metastasis are low at 25-40%, which contrasts with a 90% survival rate for individuals without lymph node metastasis.12 Metastases to the heart further worsen this prognosis with a median survival of approximately 3.5 months without treatment.26–28 Palliative care is typically indicated for LSCC cardiac metastasis patients, as most cases present with poorly prognostic advanced cardiac SCC metastasis.26

During this review, no example of remission or significant survival was demonstrated in patients with cardiac metastasis of LSCC. Many cases resulted in cardiac-related death within 30 days of cardiac metastasis presentation and five deaths occurred upon initial admission for metastatic evaluation. These findings suggest that palliation may be the most appropriate treatment strategy for patients with LSCC cardiac metastasis given the poor prognosis with current treatment strategies.

Review Limitations

This systematic review had several limitations. First, only 31 cases of cardiac metastasis from LSCC met inclusion criteria which limits the power of this study. Second, LSCC cardiac metastasis may have been underreported in the medical literature due to missed diagnoses from lack of symptomatology or post-mortem follow-up. Third, the results of this study may not be completely representative of all documented cases of LSCC cardiac metastasis due to the omission of many non-English case reports and case series.

CONCLUSIONS

Cardiac metastasis from primary LSCC demonstrates a dangerous, uncommon presentation of malignancy. Clinical suspicion for LSCC cardiac metastasis should arise in patients with new onset chest pain and shortness of breath in the setting of prior diagnosis of LSCC. Prior tobacco and alcohol use should generate additional diagnostic speculation in these patients.

In the setting of previously known disease, advanced imaging such as echocardiogram, CT, and CMRI may prove useful for identification of disease progression. LSCC cardiac metastases typically favor the right and left ventricles, but are not exclusive to these sites. Due to the poor prognostic implications of LSCC cardiac metastasis, myocardial biopsy is unlikely to alter patient management and palliative discussions should be considered.

Conflict of Interest

None

Supplementary Tables

Supplemental Table 1. Level of evidence and conclusion of studies.

| Authors | Study Year | LOE (1a-5) | Study Design | Subjects | Authors’ Conclusions |

| Tandon20 | 2019 | 4 | CR | 1 | Patients with current malignancies in addition to cardiac symptoms and/or ECG changes should warrant investigation for possible cardiac metastasis. Different imaging modalities such as CMRI, PET-CT, and echocardiography play an important role in diagnosis and management. |

| Nagata29 | 2012 | 4 | CR | 1 | Cardiac metastasis from LSCC is typically a difficult diagnosis due to the lack of clinical findings in the early stages. However, as the metastases become more advanced, clinical signs may occur, resulting in a variety of cardiac pathologies. Many of the cardiac sequelae result in ECG changes, emphasizing the importance of ECG testing in these patients. |

| Onwuchekwa30 | 2012 | 4 | CS | 2 | These cases show the importance of evaluating the heart with echocardiography to assess for cardiac metastasis in patients with head and neck cancer and confirmed metastatic disease. |

| Browning31 | 2015 | 4 | CR | 1 | It may be necessary to evaluate patients with lingual malignancies with imaging to rule out metastases. Lingual squamous cell carcinoma metastases are commonly asymptomatic, and thus, imaging is important in establishing the diagnosis. |

| McKeag32 | 2013 | 4 | CR | 1 | This case shows that cardiac metastasis from LSCC can present without symptoms or characteristic metastasis examination findings such as lymphadenopathy. |

| Hans33 | 2009 | 4 | CR | 1 | Clinicians may consider the potential for cardiac metastases in patients with a history of head and neck malignancies who display new-onset cardiovascular symptoms. These patients typically have a very poor prognosis. |

| Kumar34 | 2018 | 4 | CR | 1 | Clinicians should consider cardiac metastasis and hypercalcemia-induced rhythm disturbances in patients with a history of LSCC malignancy or current LSCC malignancy and concurrent ECG changes. It may be necessary to check calcium levels and treat the patient if levels are abnormal. |

| Nanda35 | 2019 | 4 | CR | 1 | This case shows the importance of an initial echocardiogram in addition to the integration of PET and CT scans to detect LSCC cardiac metastasis. |

| Werbel36 | 1985 | 4 | CR | 1 | This case demonstrates the importance of using echocardiography in patients with LSCC and atypical angina and/or a new heart murmur. Echocardiography is a good initial step to look for cardiac metastases. |

| Puranik37 | 2014 | 4 | CS | 2 | In asymptomatic patients with a history of cancer, whole body dual imaging with PET-CT can show undiagnosed metastatic sites. |

| Makhija38 | 2009 | 4 | CR | 1 | This case report stresses the lack of appropriate screening protocols for patients with LSCC and possible cardiac metastases. The report recommends a transesophageal echocardiogram as the best initial screen, as it is a sensitive test. |

| Wadler39 | 1985 | 4 | CR | 1 | This case report emphasizes that there are many other factors besides morphology and anatomic extent that can be used to determine LSCC prognosis. |

| Shafiq40 | 2019 | 4 | CR | 1 | This case report shows that the lack of symptoms in cardiac metastasis from LSCC can result in delayed cardiac imaging and subsequently delayed diagnosis. |

| Dredla41 | 2014 | 4 | CR | 1 | Patients with a history of cancer who have a cerebrovascular accident should have cardiac imaging to rule out a cardiac cause, such as cardiac metastases. |

| Yadav42 | 2014 | 4 | CR | 1 | This case highlights the importance of an ECG evaluation in patients with a cancer diagnosis. This can provide diagnostic clues for potential cardiac metastases. Diagnostic confirmation can be done using multiple imaging modalities, such as echocardiography, CT scan, and CMRI. |

| Zatuchni43 | 1981 | 4 | CS | 2 | LSCC cardiac metastasis can result in myocardial or pericardial injury, shown by ST-elevations on ECG. ST-elevation may be a potential sign of cardiac metastasis. |

| Shafiq44 | 2019 | 4 | CR | 1 | This case emphasizes the importance of the clinician maintaining a high index of suspicion to identify patients with metastatic LSCC. A high risk patient may need surveillance imaging with echocardiography, CMRI, and/or PET-CT. |

| Kim45 | 2019 | 4 | CR | 1 | LSCC patients with cardiac symptoms may benefit from a multimodal approach consisting of PET-CT, CMRI, echocardiography, and ECG. These imaging modalities are used to confirm the diagnosis and establish the location and extent of disease, which can guide management. |

| Demir46 | 2018 | 4 | CR | 1 | This case shows the importance of keeping myocardial metastases on the differential diagnosis when patients with known malignancies present with ECG changes. Cardiac metastases can sometimes present like an acute myocardial infarction on ECG testing. |

| Chua47 | 2017 | 4 | CR | 1 | LSCC is more common in Asian countries. It is always important to consider metastasis of LSCC to the heart and other organs, especially if patients with known LSCC present with cardiac symptoms. |

| Duband48 | 2011 | 4 | CR | 1 | Clinicians may consider an initial cardiac evaluation and serial follow-up ECGs in patients with SCC of the base of the tongue. |

| Ito49 | 2007 | 4 | CR | 1 | Sudden death in patients with LSCC should prompt clinicians to consider the potential of cardiac metastases. |

| Rivkin50 | 1999 | 4 | CR | 1 | Patients with cancer who develop new cardiac symptoms should prompt the clinician to evaluate for potential cardiac metastases. Evaluation should consist of echocardiography and/or CMRI. Treatments are typically only palliative, as cardiac metastases possess a poor prognosis. |

| Matsuyama51 | 1963 | 4 | CR | 1 | This case reports a rare finding of widespread LSCC metastasis with cardiac metastases isolated to the myocardium. This is a rare finding since most metastases affect the pericardium. |

| Malekzadeh19 | 2017 | 4 | CR | 1 | Patients with a history of head and neck malignancy who present with cardiac symptoms may prompt the clinician to evaluate for cardiac metastases. |

| Cabot52 | 1971 | 4 | CR | 1 | There are often no clinical signs of primary LSCC or metastatic LSCC to the heart, making the ante-mortem diagnosis very difficult. |

| Reddy53 | 2014 | 4 | CR | 1 | Management of tumor-induced acute coronary occlusion is similar to acute coronary syndrome occlusion, utilizing coronary angiography and percutaneous coronary intervention. |

| Ewald54 | 1997 | 4 | CR | 1 | Patients with a history of malignancy and unexplained arrhythmias or ECG changes may prompt the clinician to consider cardiac metastases on the differential diagnosis. Cardiac metastasis may present similarly to many types of cardiac pathology. |

Abbreviations: CMRI = cardiac magnetic resonance imaging; CR = case report; CS = case series; CT = computed tomography; ECG = electrocardiogram; LSCC = lingual squamous cell carcinoma; PET = positron emission tomography; PET-CT = positron emission tomography-computed tomography; SCC = squamous cell carcinoma.

Supplemental Table 2. Detailed Patient Information.

| Age/Sex | Primary Location | Signs & Symptoms | Metastasis Locations | First Identifying Imaging | Primary Treatment | Metastasis Treatment | Outcomes |

| M 59 | Right tongue mass | Fever | LA & pericardium | CT & Echo | Partial glossectomy, right RND, CTX | Cardiac surgery | Death 3 weeks after surgery |

| F 45 | Tongue | Syncope & dyspnea | RV, LV, IVS | CTA & Echo | Partial right glossectomy, RND, RT. | RT (brain) | NR |

| F 36 | Tongue | Palpitations & SOB | LV | CT & Echo | CTX-RT, partial left glossectomy, and left neck LN dissection | RT | Death 2 months after |

| M 50 | Base of tongue | Odynophagia, otalgia, dysphonia, WL, tongue and neck pain | Apex of RV | PET-CT | 2 months radiation, total glossectomy & bilateral RND | None | NR |

| M 77 | NR | Recurrent syncope | RA & RV infiltration of myocardium | Echo | None | None | Death 28 days after diagnosis |

| M 54 | Tongue base | Dyspnea, LE edema, & hemoptysis | RV | CT & Echo | Glossectomy, left RND, cisplatin, 5-FU | None | Death |

| F 23 | Tongue | CP, Right arm paresthesias, cough, SOB | LV & RV infiltration of myocardium | Echo | Surgical resection with clear margins | None | NR |

| M 28 | Tongue | Recurrent syncope | RA, LV, IVS | Echo | Hemimandibulectomy & post-operative RT | Pacemaker implantation | Death 5 days after pacemaker placement |

| M 47 | Tongue | Dizziness, SOB, chest tightness, night sweats | RA, RV, pulmonary artery | CT chest | Surgical excision with CTX-RT | None | Patient lost to follow-up |

| F 61 | Base of tongue | CP, palpitations | RA & pericardium | Echo | Hemiglossectomy with excisional biopsy of digastric LN. Neck RT | None | Death 7 weeks after cardiac diagnosis |

| F 32 | Right. lateral tongue | Nasal swelling | LV & IVS | PET-CT scan | Wide excision & right lateral neck dissection | CTX | Follow-up CT stable |

| M 46 | Right vallecula | N/A (Follow-up) | RV | Endoscopy | CTX-RT | CTX | Patient lost to follow-up |

| F 66 | Tongue | Anginal symptoms | RV | Coronary angiogram | Radical resection | None | NR |

| M 57 | Anterior tongue | Fever, dyspnea | Epicardium, myocardium, endocardium | Echo | Partial glossectomy | CTX | Death 14 days after admission from sepsis |

| M 43 | Tongue | N/A (Follow-up) | Apex of LV & RV | CT & Echo | CTX-RT | CTX | Death due to cardiac metastasis |

| M 61 | Left tongue base | Cerebral infarction symptoms | LAA and pulmonary vein | CT & Echo | CTX-RT | None | NR |

| M 76 | Tongue | Pneumonia | RV, LV | CT chest | Partial glossectomy, multiple neck dissection, CTX | Palliative care | Died in one month |

| M 61 | Tongue | CP, dyspnea | IVS and pericardium | 99mTC scan | RAD | None | Death |

| M 62 | Tongue | Malaise | Diffuse myocardium | 99mTC scan | NS | None | Death |

| M 43 | Right tongue | N/A (Follow-up) | RV, LV | CT chest | Right neck dissection & tongue resection, free flap reconstruction, CTX-RT | CTX-RT | Death |

| F 46 | Left lateral tongue | Left arm, ear, and throat pain | LV, pericardium | CT | Hemiglossectomy, bilateral neck dissection, CTX-RT | CTX-RT | NR |

| M 59 | Tongue | Chest discomfort | RV | Echo | Resection, RT | None | Death |

| M 63 | Tongue | Dyspnea | RV | Echo | Resection and reconstruction | None | NR |

| F 57 | Tongue | Death | RA, AV sulcus | Autopsy | Hemiglossectomy, bilateral cervical lymphadenectomy, CTX-RT | None | Death |

| M 66 | Right tongue into oropharynx | Death | LV, IVS | Autopsy | Total glossolaryngectomy and dissection LN bilaterally | None | Death |

| M 57 | Right tongue base | Lower extremity edema | RV | Echo, ECG, CMRI, CT | Local excision with post-operative RT to lesion and neck | CTX | Death |

| F 48 | Anterior tongue | CP, dyspnea, hemoptysis, anorexia. | Diffuse myocardium, RA, LV, aortic valve | NR | Anterior tongue glossectomy, excision of submandibular LN | None | Death |

| F 58 | Tongue | CP | NR | CT | Hemiglossectomy and RT | Palliative CTX and immunotherapy | Death |

| F 70 | Tongue | Fever & chills | Diffuse pericardium | CT | Left hemiglossectomy, RND | Thoracotomy | Death |

| F 52 | Tongue | Dull CP | RV, LV, IVS | PET | Hemiglossectomy and RND | Pericardial window and palliative care | Life expectancy < 3 months |

| M 60 | Base of tongue | Malnutrition, pneumonia | Anterior wall of RV & pulmonic valve | Echo | RT and a composite tongue-jaw-neck resection | Palliative care | Death |

Abbreviations: 5-FU = 5-fluorouracil; 99mTC = Technetium 99; CMRI = cardiac magnetic resonance imaging; CP = chest pain; CT = computed tomography; CTA = computed tomography angiography; CTX = chemotherapy; CTX-RT = chemotherapy/radiation; Echo = echocardiogram; IVS = interventricular septum; LA = left atrium; LAA = left atrial appendage; LE = lower extremity; LN = lymph node; LV = left ventricle; MRI = magnetic resonance imaging; NR = not recorded; NS = non-surgical; PET = positron emission tomography; PET-CT = positron emission tomography-computed tomography; RA = right atrium; RND = radical neck dissection; RT = radiation therapy; RV = right ventricle; SOB = shortness of breath; WL = weight loss.

Supplemental Table 3. Clinical patient characteristics.

| Characteristics | Data |

| No. of subjects | 31 |

| Male, n (%) | 19 (61.3) |

| Female, n (%) | 12 (38.7) |

| Mean age of diagnosis, n years (range) | 53.6 (23.0-77.0) |

| Mean primary to metastasis diagnosis, n years (range) | 2.2 (0.2-11.0) |

| Presenting symptoms, n (%) | |

| Chest pain | 9 (29.0) |

| Shortness of breath | 9 (29.0) |

| Syncope | 5 (16.1) |

| Weight loss | 4 (12.9) |

| Fever | 4 (12.9) |

| Oral mass | 4 (12.9) |

| Lymphadenopathy | 3 (9.7) |

| Oral pain | 3 (9.7) |

| Edema | 2 (6.5) |

| Hemoptysis | 2 (6.5) |

| Palpitations | 2 (6.5) |

| Physical exam findings, n (%) | |

| Hypotension | 4 (12.9) |

| Fever | 4 (12.9) |

| Cardiac murmur | 3 (9.7) |

| Tachycardia | 3 (9.7) |

| Diagnostic findings, n (%) | |

| Electrocardiography | 19 (61.3) |

| ST elevation | 12 (63.2) |

| Arrhythmia | 6 (31.6) |

| Bundle branch block | 4 (21.1) |

| T-wave inversion | 4 (21.1) |

| Echocardiography | 24 (77.4) |

| Pericardial effusion | 7 (29.2) |

| Right ventricular outflow tract obstruction | 6 (25.0) |

| Valvular dysfunction | 3 (12.5) |

| Wall motion abnormality | 2 (8.3) |

Supplemental Table 4. Tumor location.

| Characteristics | Data |

| Primary tumor site, n (%) | |

| Tongue | 31 (100.0) |

| Cardiac metastases, n (%) (1 case omitted) | 30 (96.8) |

| Right-sided metastasis | 23 (76.7) |

| Left-sided metastasis | 15 (50.0) |

| Septal metastasis | 11 (36.7) |

| Pericardial metastasis | 8 (26.7) |

| Specific location | |

| Right ventricle | 17 (56.7) |

| Left ventricle | 13 (43.3) |

| Interventricular septum | 9 (30.0) |

| Right atrium | 6 (20.0) |

| Left atrium | 2 (6.7) |

Funding Statement

None

References

- Oral cancer in the UK: To screen or not to screen. Rodrigues V.C., Moss S.M., Tuomainen H. Nov;1998 Oral Oncology. 34(6):454–465. doi: 10.1016/s1368-8375(98)00052-9. doi: 10.1016/s1368-8375(98)00052-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metastasis of squamous cell carcinoma of the oral tongue. Sano Daisuke, Myers Jeffrey N. Sep 3;2007 Cancer and Metastasis Reviews. 26(3-4):645–662. doi: 10.1007/s10555-007-9082-y. doi: 10.1007/s10555-007-9082-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Distant metastasis from oral cancer: A review and molecular biologic aspects. Irani Soussan. 2016Journal of International Society of Preventive and Community Dentistry. 6(4):265–271. doi: 10.4103/2231-0762.186805. doi: 10.4103/2231-0762.186805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975-2001, with a special feature regarding survival. Jemal Ahmedin, Clegg Limin X., Ward Elizabeth, Ries Lynn A. G., Wu Xiaocheng, Jamison Patricia M., Wingo Phyllis A., Howe Holly L., Anderson Robert N., Edwards Brenda K. 2004Cancer. 101(1):3–27. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20288. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinical findings and risk factors to oral squamous cell carcinoma in young patients: A 12-year retrospective analysis. Santos H.B., dos Santos TKG, Paz AR, Cavalcanti YW, Nonaka CF, Godoy GP, Alves PM. 2016Medicina Oral Patología Oral y Cirugia Bucal. 21(2):e151–156. doi: 10.4317/medoral.20770. doi: 10.4317/medoral.20770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risk factors for squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity in young people — a comprehensive literature review. Llewellyn C.D, Johnson N.W, Warnakulasuriya K.A. Jul;2001 Oral Oncology. 37(5):401–418. doi: 10.1016/s1368-8375(00)00135-4. doi: 10.1016/s1368-8375(00)00135-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Changing epidemiology of oral squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue: A global study. Ng Jia Hui, Iyer N. Gopalakrishna, Tan Min-Han, Edgren Gustaf. 2017Head & Neck. 39(2):297–304. doi: 10.1002/hed.24589. doi: 10.1002/hed.24589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardiac metastasis of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Pattni Neeraj, Rennie Andrew, Hall Timothy, Norman Aidan. Sep 9;2015 BMJ Case Reports. 2015:bcr2015211275 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2015-211275. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2015-211275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardiac metastasis in a patient with head and neck cancer: A case report and review of the literature. Kim Joseph K., Sindhu Kunal, Bakst Richard L. Apr 18;2019 Case Reports in Otolaryngology. 2019:1–8. doi: 10.1155/2019/9581259. doi: 10.1155/2019/9581259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D. G, for the PRISMA Group Jul 21;2009 BMJ. 339:b2535. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2535. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendelsohn A.C., Gray J.E., Howley A.., et al. The Molecular Basis of Cancer. Saunders; Philadelphia, PA: [Google Scholar]

- Metastasis from oral cancer: An overview. Noguti J., De Moura C.F., De Jesus G.P.., et al. 2012Cancer Genomics and Proteomics. 9(5):329–336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Analysis of the outcome of young age tongue squamous cell carcinoma. Jeon Jae Ho, Kim Min Gyun, Park Joo Yong, Lee Jong Ho, Kim Myung Jin, Myoung Hoon, Choi Sung Weon. Dec;2017 Maxillofacial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 39(1):41. doi: 10.1186/s40902-017-0139-8. doi: 10.1186/s40902-017-0139-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Outcome of oral tongue squamous cell carcinoma in patients with and without known risk factors. Bachar G., Hod R., Goldstein D.P., Irish J.C., Gullane P.J., Brown D., Gilbert R.W., Hadar T., Feinmesser R., Shpitzer T. Jan;2011 Oral Oncology. 47(1):45–50. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2010.11.003. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2010.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assessment of risk factors for oral squamous cell carcinoma in Chidambaram, southern India: A case-control study. Subapriya Rajamanickam, Thangavelu Annamalai, Mathavan Bommayasamy, Ramachandran Chinnamanoor R., Nagini Siddavaram. Jun;2007 Eur J Cancer Prev. 16(3):251–256. doi: 10.1097/01.cej.0000228402.53106.9e. doi: 10.1097/01.cej.0000228402.53106.9e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein-Barr virus in the pathogenesis of oral cancers. Guidry J.T., Birdwell C.E., Scott R.S. 2018Oral Diseases. 24(4):497–508. doi: 10.1111/odi.12656. doi: 10.1111/odi.12656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The epidemiology and risk factors of head and neck cancer: A focus on human papillomavirus. Ragin C.C., Modugno F., Gollin S.M. Feb;2007 Journal of Dental Research. 86(2):104–114. doi: 10.1177/154405910708600202. doi: 10.1177/154405910708600202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue with cardiac metastasis on 18F-FDG PET/CT: A case report and literature review. Delabie Pierre, Evrard Diane, Zouhry Ilyass, Ou Phalla, Rouzet François, Benali Khadija, Piekarski Eve. Apr 16;2021 Medicine (Baltimore) 100(15):e25529. doi: 10.1097/md.0000000000025529. doi: 10.1097/md.0000000000025529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardiac metastasis of tongue squamous cell carcinoma complicated by pulmonary embolism. Malekzadeh Sonaz, Platon Alexandra, Poletti Pierre Alexandre. Jul;2017 Medicine (Baltimore) 96(28):e7462. doi: 10.1097/md.0000000000007462. doi: 10.1097/md.0000000000007462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metastatic squamous cell carcinoma to the heart: An unusual cause of ST elevation—a case report. Tandon Varun, Kethireddy Nikhila, Balakumaran Kathir, Kim Agnes S. Mar 20;2019 Eur Heart J Case Rep. 3(2):ytz029. doi: 10.1093/ehjcr/ytz029. doi: 10.1093/ehjcr/ytz029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tumors of the heart and pericardium. Scott Roy W., Garvin Curtis F. Apr;1939 American Heart Journal. 17(4):431–436. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(39)90593-4. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(39)90593-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Metastatic squamous cell carcinoma to the heart. Unusual cause of angina decubitus and cardiac murmur. Werbel Gordon B., Skom Joseph H., Mehlman David, Michaelis Lawrence L. Sep;1985 Chest. 88(3):468–469. doi: 10.1378/chest.88.3.468. doi: 10.1378/chest.88.3.468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metastasis to the heart: A radiologic approach to diagnosis with pathologic correlation. Lichtenberger John P., Reynolds David A., Keung Jonathan, Keung Elaine, Carter Brett W. Oct;2016 American Journal of Roentgenology. 207(4):764–772. doi: 10.2214/ajr.16.16148. doi: 10.2214/ajr.16.16148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imaging characteristics of cardiac metastases in patients with malignant melanoma. Zitzelsberger Tanja, Eigentler Thomas K., Krumm Patrick, Nikolaou Konstantin, Garbe Claus, Gawaz Meinrad, Klumpp Bernhard. Jul 1;2017 Cancer Imaging. 17(1):19. doi: 10.1186/s40644-017-0122-8. doi: 10.1186/s40644-017-0122-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regional lymph node involvement and its significance in the development of distant metastases in head and neck carcinoma. Leemans Charles R., Tiwari Rammohan, Nauta J., Van der Waal Isaac, Snow Gordon B. Jan 15;1993 Cancer. 71(2):452–456. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19930115)71:2. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19930115)71:2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metastases to the heart. Reynen K., Köckeritz U., Strasser R.H. Mar;2004 Annals of Oncology. 15(3):375–381. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdh086. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdh086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eleven cases of cardiac metastases from soft-tissue sarcomas. Takenaka S., Hashimoto N., Araki N., Hamada K., Naka N., Joyama S., Kakunaga S., Ueda T., Myoui A., Yoshikawa H. Jan 19;2011 Japanese Journal of Clinical Oncology. 41(4):514–518. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyq246. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyq246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Role of palliative radiotherapy in the management of mural cardiac metastases: Who, when and how to treat? A case series of 10 patients. Fotouhi Ghiam Alireza, Dawson Laura A., Abuzeid Wael, Rauth Sarah, Jang Raymond W., Horlick Eric, Bezjak Andrea. Feb 16;2016 Cancer Medicine. 5(6):989–996. doi: 10.1002/cam4.619. doi: 10.1002/cam4.619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardiac metastasis of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Nagata S., Ota K., Nagata M., Shinohara M. Dec;2012 International Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 41(12):1458–1462. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2012.07.017. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2012.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Early cardiac metastasis from squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue in 2 patients. Onwuchekwa J., Banchs J. 2012Tex Heart Inst J. 39(4):565–567. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue with metastasis to the right ventricle. Browning Cody M., Craft Joseph F., Renker Matthias, Joseph Schoepf U., Baumann Stefan. May;2015 The American Journal of the Medical Sciences. 349(5):461–462. doi: 10.1097/maj.0000000000000411. doi: 10.1097/maj.0000000000000411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardiac metastasis from a squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue in the absence of local recurrence. McKeag N., Hall V., Johnston N.., et al. 2013Ulster Med J. 82(3):193–194. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardiac metastasis after squamous cell carcinoma of the base of tongue. Hans Stéphane, Chauvet Dorian, Sadoughi Babak, Brasnu Daniel F. May;2009 American Journal of Otolaryngology. 30(3):206–208. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2008.03.008. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2008.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A case report: metastatic complete heart block. Kumar Dhiraj, Mankame Pooja, Sabnis Girish, Nabar Ashish. Nov 29;2018 Eur Heart J Case Rep. 2(4):yty131. doi: 10.1093/ehjcr/yty131. doi: 10.1093/ehjcr/yty131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Right heart mass in transit with a hemorrhagic pericardial effusion: A diagnostic dilemma. Nanda Amit, Khouzam Rami N, Jefferies John, Moon Marc, Makan Majesh. Feb 4;2019 Cureus. 11(2):e4009. doi: 10.7759/cureus.4009. doi: 10.7759/cureus.4009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metastatic squamous cell carcinoma to the heart. Werbel Gordon B., Skom Joseph H., Mehlman David, Michaelis Lawrence L. Sep;1985 Chest. 88(3):468–469. doi: 10.1378/chest.88.3.468. doi: 10.1378/chest.88.3.468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asymptomatic myocardial metastasis from cancers of upper aero-digestive tract detected on FDG PET/CT: A series of 4 cases. Puranik Ameya D, Purandare Nilendu C, Sawant Sheela, Agrawal Archi, Shah Sneha, Jatale Prafful, Rangarajan Venkatesh. Apr 28;2014 Cancer Imaging. 14(1):16. doi: 10.1186/1470-7330-14-16. doi: 10.1186/1470-7330-14-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unusual tumours of the heart: Diagnostic and prognostic implications. Makhija Zeena, Deshpande Ranjit, Desai Jatin. Jan 12;2009 Journal of Cardiothoracic Surgery. 4(1) doi: 10.1186/1749-8090-4-4. doi: 10.1186/1749-8090-4-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulminant disseminated carcinomatosis arising from squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue. Wadler Scott, Muller Richard, Spigelman Melvin K., Biller Hugh. Jan;1985 The American Journal of Medicine. 78(1):149–152. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(85)90476-0. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(85)90476-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue with metastasis to the myocardium: A rare occurrence. Shafiq Ali, Samad Fatima, Roberts Eric, Tajik A. Jamil. Mar;2019 Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 73(9):2258. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(19)32864-5. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(19)32864-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- BM-12: Cerebral infarction secondary to pulmonary vein compression and left atrial appendage tumor infiltration as the presenting sign of metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the base of the tongue. Dredla B., Siegel J., Jaeckle K. Nov 1;2014 Neuro-Oncology. 16(suppl 5):v34. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nou240.12. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nou240.12. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cardiac metastases from head and neck cancer mimicking a myocardial infarction. Yadav Nandini U., Gupta Dipti, Baum Michael S., Roistacher Nancy, Steingart Richard M. Aug;2014 Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 72(8):1627–1635. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2014.02.015. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2014.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metastatic epidermoid cardiac tumor manifested by persistent ST segment elevation. Zatuchni Jacob, Burris Alfred, Vejviboonsom Pittaya, Voci Gerardo. May;1981 American Heart Journal. 101(5):674–675. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(81)90238-6. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(81)90238-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue with metastasis to myocardium: Report of a case and literature review. Shafiq Ali, Samad Fatima, Roberts Eric, Levin Jonathan, Nawaz Ubaid, Tajik A. Jamil. Oct 17;2019 Case Reports in Cardiology. 2019:1–6. doi: 10.1155/2019/1649580. doi: 10.1155/2019/1649580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardiac metastasis in a patient with head and neck cancer: A case report and review of the literature. Kim Joseph K., Sindhu Kunal, Bakst Richard L. Apr 18;2019 Case Reports in Otolaryngology. 2019:1–8. doi: 10.1155/2019/9581259. doi: 10.1155/2019/9581259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Right ventricular metastasis producing electrocardiographic changes mimicking acute ST elevation myocardial infarction: a case of misdiagnosis. Demir Vahit, Ede Huseyin, Hidayet Sıho, Turan Yasar. Apr;2018 The American Journal of Cardiology. 121(8):e131. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2018.03.299. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2018.03.299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isolated huge right ventricular tumor: Cardiac metastasis of tongue cancer. Chua Sarah, Liu Wen Hao, Lee Wei Chieh. Nov 1;2017 The Korean Journal of Internal Medicine. 32(6):1119–1120. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2016.143. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2016.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudden death due to myocardial metastasis of lingual squamous cell carcinoma. Duband Sébastien, Paysant François, Scolan Virginie, Forest Fabien, Péoc'h Michel. Jul;2011 Cardiovascular Pathology. 20(4):242–243. doi: 10.1016/j.carpath.2010.07.002. doi: 10.1016/j.carpath.2010.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardiac metastasis of tongue cancer may cause sudden death. Ito Taku, Ishikawa Norihiko, Negishi Tatsuro, Ohno Kazuchika. Sep;2008 Auris Nasus Larynx. 35(3):423–425. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2007.04.017. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2007.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Squamous cell metastasis from the tongue to the myocardium presenting as pericardial effusion. Rivkin Alexander, Meara John G., Li Kasey K., Potter Christian, Wenokur Randall. Apr;1999 Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery. 120(4):593–595. doi: 10.1053/hn.1999.v120.a84489. doi: 10.1053/hn.1999.v120.a84489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lingual cancer with myocardial metastasis. Matsuyama Mutsushi, Ito Masao, Baba Shunkichi. Mar;1963 Annals of Otology, Rhinology & Laryngology. 72(1):56–61. doi: 10.1177/000348946307200105. doi: 10.1177/000348946307200105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Weekly clinicopathological exercises. Case 8-1971. Cabot Richard C., Castleman Benjamin, McNeely Betty U., Kranes Alfred, Scully Robert E. Feb 25;1971 New England Journal of Medicine. 284(8):435–442. doi: 10.1056/nejm197102252840809. doi: 10.1056/nejm197102252840809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Left anterior descending coronary artery occlusion secondary to metastatic squamous cell carcinoma presenting as ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction. Reddy Gautam, Ahmed Mustafa I., Lloyd Steven G., Brott Brigitta C., Bittner Vera. Jun 17;2014 Circulation. 129(24):e652–653. doi: 10.1161/circulationaha.114.009157. doi: 10.1161/circulationaha.114.009157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A 60-year-old man with a malignant tumor of the upper airway and unexplained respiratory failure. Ewald Frank W., Scherff Albert H. Jan;1997 Chest. 111(1):239–241. doi: 10.1378/chest.111.1.239. doi: 10.1378/chest.111.1.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]