Abstract

Spike glycoprotein of the SARS-CoV-2 virus and its structure play a crucial role in the infections of cells containing angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) as well as in the interactions of this virus with surfaces. Protection against viruses and often even their deactivation is one of the great varieties of graphene applications. The structural changes of the non-glycosylated monomer of the spike glycoprotein trimer (denoted as S-protein in this work) triggered by its adsorption onto graphene at the initial stage are investigated by means of atomistic molecular dynamics simulations. The adsorption of the S-protein happens readily during the first 10 ns. The shape of the S-protein becomes more prolate during the adsorption, but this trend, albeit less pronounced, is observed also for the freely relaxing S-protein in water. The receptor-binding domain (RBD) of the free and adsorbed S-protein manifests itself as the most rigid fragment of the whole S-protein. The adsorption even enhances the rigidity of the whole S-protein as well as its subunits. Only one residue of the RBD involved in the specific interactions with ACE2 during the cell infection is involved in the direct contact of the adsorbed S-protein with the graphene. The new intramolecular hydrogen bonds formed during the S-protein adsorption replace the S-protein-water hydrogen bonds; this trend, although less apparent, is observed also during the relaxation of the free S-protein in water. In the initial phase, the secondary structure of the RBD fragment specifically interacting with ACE2 receptor is not affected during the S-protein adsorption onto the graphene.

Keywords: Molecular dynamics simulations, COVID, Spike glycoprotein, Receptor-binding domain, Secondary structure, Protection against infection

Graphical abstract

Initial (a) and final (b) conformation of the S-protein interacting with the graphene surface.

1. Introduction

The third coronavirus that crossed the species barrier causing severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS-CoV-2) was recognized in Wuhan, Hubei province of China, in December 2019 [1,2]. In comparison with SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV coronaviruses, the novel SARS-CoV-2 virus appears to be more contagious [3]. Primarily, the transmission occurs through respiratory droplets from sneezes and cough, but the transmission through the air in the form of aerosol cannot be excluded as well [4]. Another yet small source of infection is the indirect contact with contaminated surfaces [5].

In January 2020, the full-length genome sequence of SARS-CoV-2 was resolved [2]. The SARS-CoV-2 virus is composed of four structural proteins known as the spike (S), envelope (E), membrane (M), and nucleocapsid (N) protein [6]. The protruding spike glycoprotein is a homotrimer [7] which plays a key role in the infection of susceptible cells by SARS-CoV-2 as well as in the interactions with other materials. Spike glycoprotein mediates the entrance of SARS-CoV-2 virus into a human cell containing the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), which serves as an entry host receptor [[8], [9], [10]]. It comprises one S1 subunit with the receptor-binding domain (RBD) responsible for binding to the ACE2 and another S2 subunit allowing fusion of the viral and cellular membranes after S1/S2 cleavage. Many computational studies investigated so far the effect of small molecular compounds with high binding affinity for spike glycoprotein on the interactions between the RBD of spike glycoprotein and ACE2 to inhibit their mutual binding [11]. The RBD of spike glycoprotein is rather large, but only a few residues specifically bind with ACE2 receptor [12], and thus, it is difficult to find some relatively small molecule which would selectively block the whole RBD. It is thus expected that the complex nature of SARS-CoV-2 would require therapy involving a cluster of different molecules rather than a single one. Nevertheless, no such therapeutics or vaccine selectively hindering the RBD of SARS-CoV-2 virus from interactions with ACE2 have been approved to date [13,14].

Knowledge of the interactions of the spike glycoprotein with other compounds or materials is useful to get an idea on how the SARS-CoV-2 virus is spreading and which material can work as an efficient protecting barrier and possibly even SARS-CoV-2 deactivator. The impermeability of protective masks to viruses is one of the most important parameters. In the ideal case, the adsorbent not only captures but also deactivates the virus after its adsorption when the viral membrane is impaired. In the last decade, the two-dimensional graphene, composed of hexagonally packed sp2 hybridized carbon atoms [15], and its derivatives have been widely used as adsorption materials thanks to their high surface-to-mass ratios and exceptional, physical, chemical, mechanical, biological, and electronic properties. An especially relevant property of the graphene regarding its utilization as a protective material is its strong interaction with incident visible light [16]. This is a pertinent feature for sterilization of material by heat generation. However, the adsorption of a virus onto graphene itself might cause significant disruption (denaturation) of the membrane structure, which in turn would lead to the loss of viral infectivity because the spike glycoprotein binds to ACE2 in its native and open conformation [7]. Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of peptides and proteins interacting with graphene have revealed their strong adsorption on graphene and remarkable changes in their secondary structures induced by the adsorption [[17], [18], [19], [20]]. The fragment of viral protein R involved in the regulation of HIV genes through channel formation, Vpr13-33, underwent secondary structure transition from α-helix to β-sheet when the conformation of α-helix virtually disappeared already after 10 ns of the MD simulation [20]. The strength of adsorption of protein G-related albumin on graphene was compared with graphene oxide, and it turned out that the disruption of the native conformation of this protein was more substantial when it interacted with graphene [19].

Economic and reusable graphene masks have been already developed and are accessible [21], and a graphene-based air purification scheme is under elaboration [22]. The monolayered or multilayered graphene in the form of a mist spray or contained in surface cleaner wipes might be considered as an agent for disinfection of the surfaces infected with SARS-CoV-2 [23]. The capability of this equipment to exterminate the adsorbed SARS-CoV-2 viruses depends on the extent of the denaturation of the spike glycoprotein upon its adsorption.

In this work, the specific interactions between the non-glycosylated monomer of the spike glycoprotein trimer (further referred to as S-protein throughout this article) and graphene during the initial phase of adsorption is studied using atomistic MD simulations. These simulations should shed light on the kinetic of adsorption of the S-protein and the initial structural changes stemming from its adsorption onto the graphene. Special attention is devoted to the structural behavior of the RBD as this fragment is decisive for the cell infection. The extent of the secondary structure modification of the S-protein monomer renders a notion of the expected deformation of the secondary structure of the spike glycoprotein which in turn affects SARS-CoV-2 infectivity. The aim of this study is also to compare the structural changes of the S-protein interacting with the graphene in water with the structural changes induced by the relaxation of the free S-protein in water. This comparison allows separation of the effects brought about by the adsorption onto the graphene from the effects caused by the aqueous environment.

2. Methodology

All-atom MD simulations were used to investigate the interaction between S-protein and graphene sheet in water. The input structure of the non-glycosylated S-protein monomer, composed of 1273 amino acid residues, was taken from the model of spike glycoprotein homotrimer obtained from Zhang's group (QHD43416.pdb) [24]. This model is based on the incomplete crystal structure of the spike glycoprotein trimer determined using cryo-electron microscopy (PDB ID 6VXX, average resolution of 0.28 nm) [7]. This conformation corresponds to the RBD-down state, i.e., closed state. The missing residues, namely residues 1–26, 70–79, 144–164, 173–185, 246–262, 445, 446, 455–488, 502, 621–640, 677–688, 828–853, 1148–1273, were modeled by the I-TASSER protocol. The omission of glycan units, which are important for the immunogenicity of the protein, may also influence the structure of the S-protein to a certain extent. However, it was shown that the presence of glycan moieties did not influence the conformation of the spike glycoprotein at different temperatures [25]. If the trimer was considered, the size of the simulation system would increase at least 4 times. Thus, the model used in this simulation study is capable of describing the secondary and tertiary structural changes induced during the initial adsorption stage of the S-protein but not the changes in the quaternary structure of the RBD of the spike protein trimer. To get an idea of the modification of the structure of the RBD in the presence of glycans, the glycosylated RBD of the spike glycoprotein trimer with up-conformation of one RBD monomer and down-conformation of two RBD monomers was also simulated during its initial adsorption onto the graphene. This initial conformation corresponded to the open state (prefusion conformation). More details on the input conformation are provided in the Supplementary Information.

To adequately capture the hydrophobic interactions between the S-protein and water, which usually represent the most important contribution to the interactions, instead of creating only a thin hydration layer surrounding the S-protein, whole space between the graphene sheets was hydrated. The total number of atoms and water molecules along with the dimensions of the simulation box and the separation between the graphene sheets in all simulated systems are summarized in Table 1 .

Table 1.

Dimensions of the simulation box, separation between the graphene sheets, and total number of atoms and water molecules of all simulated systems.

| System | Box dimensions/nm | Separation between graphene sheets/nm | Total number of atoms | Number of water molecules |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S-protein + graphene | 17.09 × 17.18 × 63.00 | 21.00 | 618,318 | 192,178 |

| S-protein | 17.00 × 17.00 × 17.00 | 483,924 | 154,740 | |

| Graphene | 17.09 × 17.18 × 15.00 | 5.00 | 155,127 | 44,349 |

| Glycosylated RBD + graphene | 14.51 × 14.48 × 48.00 | 16.00 | 339,526 | 103,873 |

RBD, receptor-binding domain.

Arginine and lysine were considered in their protonated forms, glutamate and aspartate were considered as deprotonated, and histidine was neutral, which yielded a total charge of −7. The C and N termini were deprotonated and protonated, respectively. To compensate for the overall negative charge of the system, seven Na+ ions were added to the system. The atoms of the graphene were kept frozen and treated as neutral, i.e., only van der Waals interactions of the graphene with the S-protein and water molecules were taken into account. In the initial conformation (Fig. 1 ), the minimal distance between the atoms of S-protein and graphene was 0.8 nm. This value was more than twice the distance corresponding to the minimum of the van der Waals potential energy, and it was still smaller than the interaction cutoff distance. The S-protein pointed with its S1 subunit containing the RBD (residues 319 to 541) toward the graphene. The graphene surface was aligned with the xy plane and placed at the bottom of the simulation box. To prevent interactions with periodic images along the z-direction, the second graphene plane was placed at a distance of 21 nm from the bottom graphene plane along the z axis and a vacuum slab of 42 nm was inserted above the upper plane. Periodic boundary conditions were applied in all three dimensions, and graphene was modeled as infinitely large. The particle-mesh Ewald (PME) sum method [26,27] was applied to handle the long-range electrostatic interactions. However, in the Ewald summation, the reciprocal sum was performed in three-dimensional space, but forces and potential were only applied in the z dimension to produce a pseudo-two-dimensional summation. The box height (63 nm) which is 3 times larger than the separation between the graphene sheets should be large enough to avoid electrostatic interactions between periodic images.

Fig. 1.

Initial conformation of the S-protein and graphene surface. The RBD is displayed in red, while the remaining residues of the S-protein are displayed in blue. For better clarity, the water molecules are omitted. RBD, receptor-binding domain. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

To obtain a reference system for the S-protein, MD simulations for a free S-protein in water were also carried out with the same initial conformation of the S-protein as the one used for the MD simulations with the graphene. The MD simulations of pure water interacting with graphene provided a reference system for the water behavior at the interface with graphene.

All MD simulations were performed using the GROMACS software package [28]. The intramolecular and intermolecular interactions of S-protein and graphene were described by the CHARMM force field [29]. Water molecules were represented by the TIP3P model [30,31]. Using the non-polarizable force fields for the representation of graphene carbon atoms is quite common in the graphene-protein-water systems [32,33]. Inclusion of polarization effects may influence the adsorption energies and relative strength of adsorption of the individual amino acids residues, but it adds more interaction sites which makes simulations more time demanding. The structure of an interacting protein might be modified directly through the interaction with the graphene as well as indirectly through the modification of the layer of interfacial water molecules owing to the polarization effects.

Following an energy minimization by the steepest descent algorithm, the systems were allowed to equilibrate for 1 ns with a time step of 1 fs in the canonical ensemble (NVT). In this stage of the MD simulations, the positions of S-protein atoms were kept fixed and only the water molecules were relaxed. Finally, all atoms were relaxed during the next simulation runs in the (NVT) ensemble using a time step of 2 fs, but with all bond lengths constrained at their equilibrium lengths by the LINCS algorithm [34]. The temperature T was always kept fixed at 310 K by the velocity rescaling method with a relaxation time of 0.1 ps, in which a stochastic term was added to ensure sampling a proper canonical ensemble [35]. The overall simulation time was 40 ns, out of which the first 20 ns was assumed as the equilibration period and the last 20 ns as the production phase. The time interval between sampling conformations was 10 ps. The relaxation times, τ, extracted from the simple exponential autocorrelation functions fitting the initial parts of the plots, e −t/τ, of the mean values of the end-to-end distance/radius of gyration were 280 ps/400 ps and 1230 ps/1640 ps for the S-protein interacting with graphene and for the free S-protein, respectively. The relaxation time of the S-protein during its adsorption is considered. The plots and corresponding fits are shown in Fig. S1 of the Supplementary Information. The faster relaxation of the S-protein interacting with the graphene than that of the free protein may be attributed to its reduced degrees of freedom. Similar findings were reported for a geometrically constrained DNA in nanochannels where the relaxation times decreased with the decreasing diameter of the nanochannel, i.e., with the increasing confinement strength [36]. As referred earlier, the long-range electrostatic interactions were dealt with the PME method with a real space cutoff of 1.3 nm. As to the Lennard-Jones (LJ) interactions, these were truncated at interatomic distances larger than 1.3 nm. To eliminate the discontinuity in the potential energy due to such cutoff, the LJ forces were smoothly switched to zero for interatomic distances between 1.0 nm and 1.3 nm. The neighbor list was maintained and updated using the Verlet cutoff scheme based on an energy drift with a buffer tolerance of 0.005 kJ∙mol−1∙ps−1 [37].

3. Results

3.1. Kinetics of adsorption

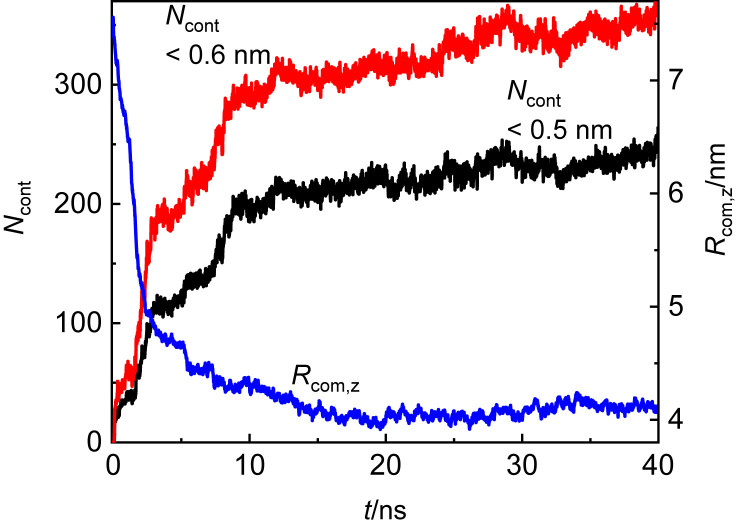

The kinetics of adsorption of the S-protein on graphene was monitored by the time dependence of the S-protein center of mass (COM) distance from the graphene plane, R com,z, as displayed in Fig. 2 . For comparison, the number of atoms in contact with the graphene plane, N cont, is also plotted in the same graph. Two distance criteria, 0.5 nm and 0.6 nm, were adopted to define the contact of the S-protein atoms with the graphene. Both criteria provide a similar trend. It is obvious that the adsorption happens during the first 10 ns of the simulation run, and after 20 ns, a plateau is achieved in R com,z and N cont. There are no indications of a desorption phase during the 40 ns of simulations. During the adsorption, the averaged distance between the COM of the S-protein and graphene drops from 7.6 nm to 4.1 nm. After 40 ns of the simulation run, the number of contacts as a function of time displays still slightly increasing trend. The longer simulations would require extension of the simulation cell in x and y directions to prevent the interactions of the S-protein with its mirror images owing to its expansion in these directions. It should be mentioned at this point that the formation of a monolayer of adsorbed protein presumes disruption of the protein secondary structure. However, it has been found that there may be some sequences of amino acid residues which stabilize the secondary structure such as α-helix [38]. If these stabilizing interactions prevail over the interactions of the amino acid residues with the graphene, the local secondary structure may persist.

Fig. 2.

Time evolution of the S-protein center of mass distance R(com,z) from the graphene and the number of atoms of the S-protein in contact with the graphene, Ncont, based on the distance criteria 0.5 nm or 0.6 nm.

3.2. Radius of gyration and contact area

In contrast with small rigid molecules, the adsorption of sizeable proteins onto the solid surfaces is more complex and linked with their structural rearrangement leading to changes in surface affinity and many other phenomena. The adsorption of the S-protein on graphene is accompanied by changes of its shape as it is evident in Fig. 3, showing the initial and final conformation after 40 ns of the simulation run. The time dependences of the radius of gyration, its perpendicular component , lateral components and , and their root mean square are presented in Fig. 4 a. During the equilibration phase (the first 20 ns), the perpendicular component R gz decreases, while an increase of the component is associated with a less pronounced decrease of the component. However, their root mean square raises and, as can be seen in Fig. 4b, the trend approximating the trace of the adsorbed S-protein well correlates with the contact area (A cont) evaluated from the solvent accessible surface area of the graphene, S-protein, and their complex as follows: A cont = (SASA graphene + SASA S-protein − SASA complex)/2. This confirms that the lateral extension of the S-protein is triggered by the adsorption on the graphene. Fig. 4c compares the radius of gyration and its principal components λ 1, λ 2, and λ 3 of the S-protein adsorbed on the graphene with the free S-protein. These components bear information about the shape of the S-protein, while the R gx, R gy, and R gz components bear information about the spatial distribution of the S-protein with respect to the graphene plane. The constrained structural freedom of the S-protein attracted by the graphene surface is reflected on the reduced fluctuations of these quantities when compared with the free S-protein. The most dramatic changes in these quantities are observed within the first 5 ns and are more striking for the S-protein interacting with graphene. However, the time evolution of these components for both the interacting and free S-protein exhibits the same trend. The largest principal component slightly increases and is only modestly influenced by the adsorption, while the initially declining trend of the two remaining principal components is more supported by the adsorption. As is evident from the trends of the radius of gyration of the adsorbed S-protein and of the free S-protein, the S-protein becomes more compact in the initial stage of adsorption. The averaged values of the radius of gyration and its principal components along with the end-to-end distance of the adsorbed and free S-protein are collected in Table 2 . As can be seen, the adsorption only modestly modifies the radius of gyration and its components while it is capable of shortening of the end-to-end distance R e.

Fig. 3.

Snapshots of the initial conformation (a) and final conformation after 40 ns of MD run (b) of the S-protein interacting with the graphene surface; RBD (red), S1 (blue), S2 (gray). MD, molecular dynamics; RBD, receptor-binding domain. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

Fig. 4.

Time evolution of the radius of gyration Rg and its components Rgx, Rgy, and Rgz of the S-protein interacting with graphene (a) and of its contact area and the approximation of xy projection of the S-protein scaled by π (b). Time dependence of , the radius of gyration, and its principal components λ1, λ2, and λ3 of the S-protein interacting with the graphene (solid lines) and of the free S-protein (dotted lines) (c).

Table 2.

End-to-end distance, radius of gyration, and its principal components of the S-protein after adsorption on the graphene and of the equilibrated free S-protein. The standard deviations are in parentheses.

| System | Re | Rg | λ1 | λ2 | λ3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S-protein + graphene | 5.220 (0.163) | 4.047 (0.012) | 3.448 (0.017) | 1.717 (0.017) | 1.239 (0.021) |

| S-protein | 7.256 (0.286) | 4.103 (0.044) | 3.335 (0.050) | 1.816 (0.028) | 1.552 (0.042) |

3.3. Asphericity and prolateness

The adsorption-induced changes of the S-protein shape can also be quantified using the asphericity Δ and prolateness S parameters defined as follows [39]:

| (1) |

| (2) |

The asphericity Δ varies between 0 and 1 when going from a spherical to a rod-like shape. The prolateness parameter spans the range [−0.25, 2] with the lower and upper limit corresponding to an ideal disc and a rod shape, respectively. Negative values of the prolateness mean an oblate shape, whereas positive values mean a prolate shape. Fig. 5 shows the time evolution of both these parameters for the S-protein interacting with graphene and the free S-protein.

Fig. 5.

Time evolution of the asphericity Δ and prolateness S of the S-protein interacting with the graphene (solid lines) and of the free S-protein (dotted lines).

The shape of the starting conformation of the S-protein appears to be rather isotropic as can be deduced from the low values of respective Δ and S parameters and from the ratio λ 1:λ 2:λ 3 = 2.30:1.55:1. For comparison, note that the asymptotic ratio of a random-walk chain is 3.48:1.65:1 [40]. Both processes, i.e., the relaxation of the free S-protein in water as well as its adsorption on the graphene surface in water, contribute to the enhancement of the asphericity and prolateness parameters, more notably for the latter process. Thus, the asymmetry of the S-protein during its adsorption increases. However, flattening of the S-protein during its adsorption would lead to a decreasing trend of the prolateness parameter up to negative values when virtually a monolayer of atoms adsorbed on a surface might be formed. Instead, during the simulations, the shape of the S-protein becomes more prolate and much more reduced R gz components appear from the reorientation of the S-protein, which in turn enhances its prolate shape. This is also illustrated in Fig. 3. The ratio λ 1:λ 2:λ 3 is changed to 2.78:1.39:1 and 2.15:1.16:1, respectively, for the relaxed free S-protein and the S-protein adsorbed on the graphene. Striking deformation of the spike glycoprotein adsorbed on the graphite was also observed in other MD study [33].

3.4. Root-mean-square deviation and cluster analysis

Influence of the presence of graphene on the conformational dynamics of the S-protein can be inferred from the time dependence of the root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of atom positions with respect to the initial conformation, which can be evaluated as follows:

| (3) |

where N is the number of atoms and r i(t) is the position of atom i at time t of the structure superimposed with the reference structure at time t = 0. In addition to RMSD for the whole S-protein, RMSD of its subunits S1 (residues 14–685) and S2 (residues 686–1273) as well as of RBD (residues 319–541) [41] were calculated for both systems (Fig. 6 ).

Fig. 6.

Time evolution of the root-mean-square deviation of the S-protein, S1 subunit, S2 subunit, and RBD in the system with the graphene (solid lines) and without the graphene (dotted lines). RBD, receptor-binding domain; root-mean-square deviation.

As for the structural quantities discussed earlier, RMSD values of the free and adsorbed S-protein are well equilibrated after 20 ns. During adsorption of the S-protein, the most abrupt changes in the conformation happen within the first 5 ns when RMSD attains the value of 1.14 nm. The time evolution of RMSD of S1 subunit, which is found to be the most flexible moiety, copies the same trend, and its averaged value of 1.28 nm exceeds the corresponding value of the whole S-protein. In opposite to S1 subunit, RBD experiences rather negligible conformational modification upon adsorption during the whole simulation run with the average RMSD value of 0.41 nm. The average value of the RMSD of S2 subunit is 0.62 nm. It is apparent that the adsorption of the S-protein on the graphene brings about faster initial conformational changes of the S-protein and its S1 subunit when compared with the free S-protein. However, the higher equilibrated values of RMSD for the free S-protein and its S1 subunit (1.49 nm and 1.55 nm, respectively) than those of the adsorbed S-protein indicate reduced conformational freedom of the adsorbed S-protein and its S1 subunit. When comparing the RBD of the free and adsorbed S-protein, one can see that the adsorption does not affect the conformation of the RBD significantly during the first 20 ns of the simulation run. In the second half of the simulation run, RMSD of the RBD of the free S-protein increases to 0.57 nm while RMSD of the RBD of the adsorbed S-protein remains more or less leveled off. It points to the increased rigidity of the RBD, which is in direct contact with the graphene. As can be seen in Fig. 6, the peripheral S2 subunit virtually withstands substantial deformation during the adsorption and is only a little more flexible than the RBD. These findings are in line with the structural flexibility of the spike protein subunits studied at different temperatures [25].

Additional information about the dynamics of the structural changes might be achieved from a cluster analysis. In contrast to the RMSD analysis, the time evolution of the number of distinct clusters provides insights into the structural transitions occurring on the time trajectory (Fig. 7 ). The presented analysis is based on the single linkage method for which the cluster is defined as an entity containing conformations with RMSD ≤0.1 nm from the central structure. As it can be seen, the dynamics of conformational changes is significantly slowed down by the adsorption of the S-protein. During the S-protein adsorption, the total number of clusters (117) is saturated already after 10 ns, whereas the number of clusters increases linearly for the free S-protein during the whole simulation period.

Fig. 7.

Increase in the number of clusters formed by the S-protein with and without the graphene during the MD simulations. The initial structures of the S-protein (red) are compared with the most representative structure (blue) arising from its adsorption on the graphene and with the conformation of the free S-protein after 40 ns of the MD simulation. MD, molecular dynamics. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

3.5. Specific interactions of the S-protein with graphene

Another aspect deserving special attention is the identification of residues from the S1 subunit that are in direct contact with graphene and their contact frequencies, i.e., the number of stored frames for which that occurs. Here, the contact event is considered when the distance between any non-hydrogen atom and the graphene falls below or equals to 0.3 nm. The residues satisfying this criterion and having contact frequency larger than 100 events during the whole MD run are collected in Table 3 along with their respective contact frequencies.

Table 3.

Residues of the S1 subunit being in contact with the graphene during the whole MD simulation and their contact frequencies (CFs).

| Residue | CFa | Residue | CFa | Residue | CFa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pro330 | 1658 | Thr22 | 534 | Gln580 | 316 |

| Ser12 | 1068 | Thr333 | 444 | Thr581 | 278 |

| Cys15 | 1249 | Asn481 | 442 | Asn450 | 252 |

| Arg21 | 982 | Asn74 | 440 | Gln14 | 211 |

| Ser469 | 745 | Tyr248 | 414 | Thr20 | 194 |

| Asn17 | 653 | Thr19 | 376 | Asn331 | 172 |

| Asn360 | 579 | Ser13 | 359 | Val16 | 124 |

| Thr470 | 541 | Asn334 | 319 | Thr73 | 101 |

MD, molecular dynamics; RBD, receptor-binding domain.

The bold-marked residues belong to the RBD subunit.

A cutoff of 0.3 nm is considered as the criterion for a contact, and it applies to the non-hydrogen atoms of the S1 subunit.

In several previous simulation studies, the strongest adsorption on graphene has been found for Trp and Tyr with aromatic substituents and for polar basic Arg with guanidine substituent, when the π-π stacking (Trp and Tyr) and guanidine-π stacking (Arg) interactions are prominent [[42], [43], [44], [45], [46]]. The amide-π stacking interactions are possible for polar neutral Gln and Asn, which are adsorbed fairly well. On the other side, residues with aliphatic side chains do not display significant binding affinities for graphene in water. As can be seen in Table 3, there is an abundance of Asn (7 residues) in direct contact with graphene, while only 2 Gln residues and 1 Tyr residue are found in close vicinity to graphene. The orientations of these residues really correspond to the amide-π stacking (Asn and Gln) and π-π stacking (Tyr). The absence of contacting Trp follows from the rare occurrence of this residue within the S1 subunit. The surrounding residues prevent these Trp residues from creating contacts with the graphene. There are more residues interacting with graphene through their aromatic side chains or through the amidic or guanidine groups introduced in their side chains with the distance of the contact atoms from the graphene in the interval of 0.3 nm–0.6 nm. These residues include Arg357 and Arg466 with guanidine-π stacking interactions; Gln23, Asn331, and Asn448 with amide-π stacking interactions; and Trp258, Tyr144, Tyr449, Phe4, Phe79, Phe329, Phe464, and Phe562 with π-π stacking interactions. Worth noticing is also the highest contact frequency found for Pro330 during the last 20 ns of simulation, even though Pro is classified as a weak adsorbent when interacting with the graphene [[42], [43], [44], [45], [46]]. Its close proximity to the graphene, however, results from the neighboring residues, Phe329 and Asn331, which directly interact with graphene. Similarly, seven Thr residues occur in close vicinity to graphene, although polar neutral Thr is regarded as a weak adsorbent [[42], [43], [44], [45], [46]]. In this case, the interactions of Arg21 with graphene bring Thr19, Thr20, and Thr22 to the contact with the graphene, while Thr73, Thr333, and Thr581, respectively, are in contact with the graphene through interactions of Asn74, Asn334, and Gln580 with graphene. Residues Ser12, Cys15, and Val16 are in contact with the graphene through the specific interactions of Gln14 and Asn17 with graphene. It should be mentioned that out of the all significant contacts with the graphene, only Tyr449 residue of the RBD participates in the specific interactions between the RBD and ACE2 receptor during the initial phase of cell infection [12,47,48]. It should be emphasized at this point that Asn331 is the only amino acid residue in contact with graphene which is glycosylated in the spike glycoprotein trimer. In the glycosylated RBD, this amino acid residue is slightly removed from the graphene. However, it has been shown that the glycan moieties are only marginally involved into the contact with interacting surface and they occupy the lateral regions of the adsorbed spike glycoprotein [33]. The interactions of individual residues with the graphene do not seem to be mediated by water molecules; the water molecules in the first hydration layer, however, affect the orientation of those residues which do not possess some stacking interactions with graphene. For instance, the hydroxyl groups of Ser and Thr residues form hydrogen bonds with the water molecules contained in the first hydration layer, while the amide groups of these residues occupy the space between the first and the second hydration layer. As shown in Fig. S2 of the Supplementary Information, all residues of the S1 subunit of the S-protein found as being in contact with graphene are located at the periphery of the spike glycoprotein trimer (6VXX structure [49]), and thus, these residues are expected to be available to interact with graphene also in the spike protein trimer.

3.6. Behavior of water and hydrogen bonds

The structuring of interfacial water is not disturbed by the presence of the S-protein as can be seen in Fig. 8 , where the density profile of interfacial water is compared with the density profile of interfacial water above the graphene in the absence of the S-protein.

Fig. 8.

Density profile of the interfacial water as a function of the distance from the graphene in the presence and in the absence of the S-protein.

The number of water molecules expelled from the hydration layer of the graphene is a measure of the hydrophobic interactions between the S-protein and graphene, which are dominated by the entropy. The number of water molecules in slices with the thickness of 3 nm is displayed in Fig. 9 , which also presents the number of water molecules contained in the first slice above the free graphene. The average number of water molecules expelled from the first slice as a consequence of the S-protein adsorption is 1794. From the second and the third slice, 1396 and 1321 water molecules are expelled, respectively. The bulk water density is restored at a distance larger than 9 nm from the graphene.

Fig. 9.

The average number of water molecules in 3-nm-thick slices above the graphene interacting with the S-protein. The average number of water molecules in the first slice above the free graphene is also included for comparison.

Formation of intramolecular hydrogen bonds is crucial for the secondary structure of proteins. The pure geometric distance-angle criterion was adopted for definition of hydrogen bonds, according to which a hydrogen bond exists if the acceptor-donor distance is not more than 0.35 nm and the maximal plausible deviation of the acceptor-donor-hydrogen angle from linearity is 30°. The time dependence of the total number of hydrogen bonds formed within the S-protein in both investigated systems is shown in Fig. 10 a. The number of internal hydrogen bonds in the free S-protein first increases than decreases, and after 20 ns of MD simulation, it increases back again. It thus appears that the adsorption of the S-protein onto the graphene promotes the formation of intramolecular hydrogen bonds. This is also consistent with the more compact shape of the S-protein adsorbed on the graphene when compared with the shape of the freely relaxed S-protein. The number of internal hydrogen bonds formed in the adsorbed S-protein more or less follows an increasing trend. The decomposition of the hydrogen bonds into contributions, which also participate in formations of helical structures, is presented in Fig. 10b. It reveals that the contribution due to the hydrogen bond interactions between residue pairs n and n + 4, which participate in the formation of α-helices, is enhanced upon adsorption. In contrary, the number of n − n + 3 hydrogen bonds, occurring in 310 helices, drops during the S-protein adsorption. The formation of n − n + 5 hydrogen bonds which might stabilize π-helices in the adsorbed S-protein is only slightly raised in the last 10 ns of MD simulations. The increasing time evolution of the total number of hydrogen bonds within the S-protein adsorbed on the graphene is dictated by the increasing trend of the number of hydrogen bonds created between pairs of residues separated by 5 and more residues.

Fig. 10.

Time evolution of the number of hydrogen bonds formed within the S-protein in the presence and in the absence of the graphene (a), and their decomposition into the contributions arising from the interactions between residues separated by 2, 3, and 4 residues; system with the graphene (solid lines) and system without the graphene (dotted lines) (b).

The number of hydrogen bonds formed between the S-protein and water molecules is also affected by adsorption of the S-protein as can be seen in Fig. 11 . This number decreases with time in both systems consistently with the increased number of intramolecular hydrogen bonds. The replacement of the S-protein-water hydrogen bonds with the intramolecular hydrogen bonds is more striking for the adsorbed S-protein.

Fig. 11.

Time evolution of the number of hydrogen bonds formed between the S-protein and water molecules in the presence and in the absence of the graphene.

3.7. Secondary structure

The secondary structure of the free and adsorbed S-protein has been analyzed using the STRIDE algorithm [50], which combines hydrogen bond energy data with statistically derived backbone torsion angle data. A weighted product of hydrogen bond energy and torsion angle probabilities for α-helix and β-sheet determines the initiation and termination of secondary structure units based on empirically optimized recognition thresholds. The variation of the secondary structure with time for the free and adsorbed S-protein during the first and the last 10 ns of MD simulations is displayed in Fig. 12 . As can be seen, the secondary structure of the S-protein is subject to substantial changes not only during its relaxation in water but also during its adsorption on graphene. Similar behavior was reported in the study of the spike glycoprotein adsorption on the graphite and cellulose [33]. The S1 subunit is dominated by β-sheets, while the S2 subunit is rich in α-helices. The content of helices and main β-sheet substructures and their composition in RBD of the S-protein in its initial conformation is compared with the corresponding final content within the RBD of both systems in Table 4 and shown in Fig. 13 . The initial secondary structure of RBD is composed of 4 α-helices, one 5-stranded β-sheet, and one 2-stranded β-sheet. During the adsorption, a new α-helix (Phe338-Gly339-Glu340-Val341-Phe342-Asn343) is created and one α-helix (Glu406-Val407-Arg408-Gln409) transforms into a turn. The situation is different with the RBD of the free S-protein. In agreement with the adsorbed S-protein, a new α-helix (Phe338-Gly339-Glu340-Val341-Phe342-Asn343) arises; however, two α-helices (Pro384-Thr385-Lys386 and Ile418-Ala419-Asp420-Tyr421-Asn422) present in the initial RBD structure disappear. Thus, from comparison of the adsorbed S-protein with its free analog, one can conclude that the adsorption of the S-protein is responsible for the stabilization of two α-helices (Pro384-Thr385-Lys386-Leu387-Asn388-Asp389 and Ile418-Ala419-Asp420-Tyr421-Asn422) and for diminishing of one α-helix (Glu406-Val407-Arg408-Gln409) in the RBD. The new α-helix (Phe338-Gly339-Glu340-Val341-Phe342-Asn343) originates from the relaxation in water rather than from the adsorption onto graphene. The main 5-stranded β-sheet is stabilized upon adsorption because it is preserved during the adsorption of the S-protein. The strands of this β-sheet are aligned parallel to the graphene with the strand Asn354-Arg355-Lys356-Arg357-Ile358 being closest to the graphene through the guanidine-π stacking interactions between Arg357 and graphene. This strand is shortened during the relaxation of the free S-protein, and some new short β-sheets arise. The two strands of the short 2-stranded β-sheet slightly elongate during the adsorption of the S-protein as well as during its free relaxation in water. Some MD studies have pointed out the preference of β-sheets to α-helices near the graphene surface [20,51], and also the opposite trend has been observed [52]. In the present MD simulation study, the diminished α-helix was not in direct contact with graphene during the adsorption. It should be mentioned that 310-helices appeared as transient substructures during the MD simulations, being converted from turns, coils, or terminal fragments of α-helices. The secondary structure of the fragments containing residues, which are directly involved in the interactions with the ACE2 receptor [12], however, remained unaltered during the adsorption.

Fig. 12.

Time evolution of the secondary structure of the S-protein adsorbed on the graphene during the first 10 ns (a) and the last 10 ns (b) and of the free S-protein during the first 10 ns (c) and the last 10 ns (d). The horizontal axes represent the time scale, and the vertical axes represent the residue sequence.

Table 4.

Secondary structure of the RBD of the S-protein in its initial conformation, of the adsorbed S-protein, and of the freely relaxed S-protein.

| RBD | S-protein initial structure | Adsorbed S-protein | Free S-protein |

|---|---|---|---|

| α-Helixa | Phe338-Gly339-Glu340-Val341-Phe342-Asn343 | Phe338-Gly339-Glu340-Val341-Phe342-Asn343 | |

| Tyr365-Ser366-Val367-Leu368-Tyr369-Asn370 | Tyr365-Ser366-Val367-Leu368-Tyr369 | Ser366-Val367-Leu368-Tyr369-Asn370 | |

| Pro384-Thr385-Lys386 | Pro384-Thr385-Lys386-Leu387-Asn388-Asp389 | ||

| Glu406-Val407-Arg408-Gln409 | Gly404-Asp405-Glu406-Val407-Arg408 | ||

| Ile418-Ala419-Asp420-Tyr421-Asn422 | Ile418-Ala419-Asp420-Tyr421-Asn422 | ||

| 5-Stranded β-sheet | Asn354-Arg355-Lys356-Arg357-Ile358, Thr376-Phe377-Lys378-Cys379-Tyr380, Asn394-Val395-Tyr396-Ala397-Asp398-Ser399-Phe400-Val401-Ile402, Gly431-Cys432-Val433-Ile434-Ala435-Trp436, Tyr508-Arg509-Val510-Val511-Val512-Leu513-Ser514-Phe515-Glu516 |

Asn354-Arg355-Lys356-Arg357-Ile358, Thr376-Phe377-Lys378-Cys379-Tyr380, Asn394-Val395-Tyr396-Ala397-Asp398-Ser399-Phe400-Val401-Ile402, Gly431-Cys432-Val433-Ile434-Ala435-Trp436-Asn437, Tyr508-Arg509-Val510-Val511-Val512-Leu513-Ser514-Phe515-Glu516 |

Lys356-Arg357-Ile358, Thr376-Phe377-Lys378-Cys379-Tyr380, Asn394-Val395-Tyr396-Ala397-Asp398-Ser399-Phe400-Val401-Ile402, Gly431-Cys432-Val433-Ile434-Ala435-Trp436-Asn437, Tyr508-Arg509-Val510-Val511-Val512-Leu513-Ser514-Phe515-Glu516 |

| 2-Stranded β-sheet | Thr323-Glu324-Ser325-Ile326, Val539-Asn540-Phe541-Asn542 |

Glu324-Ser325-Ile326, Cys538-Val539-Asn540-Phe541- Asn542-Phe543 |

Glu324-Ser325-Ile326, Val539-Asn540-Phe541-Asn542-Phe543 |

MD, molecular dynamics; RBD, receptor-binding domain.

During the MD simulations, some short α-helices transiently transformed into 310-helices.

Fig. 13.

Secondary structure of the RBD of the initial conformation of the S-protein (a), in the adsorbed S-protein (b), and in the freely relaxed S-protein (c). The α-helices are represented by blue cylinders, and the β-sheets are represented by red ribbons. RBD, receptor-binding domain. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

The glycosylated RBD subunit adsorbs onto the graphene through two monomers as can be seen in Fig. S3 of the Supplementary Information. One of these two monomers is closer to and in direct contact with the graphene. It can be seen that the glycan units are not situated between the graphene and amino acid residues of this closest monomer and the secondary structure is similar to the secondary structure of the RBD of the S-protein (Fig. 13b). Similarly to the case of S-protein, the 5-stranded β-sheet is also stabilized in this monomer of the glycosylated RBD during the adsorption, whereas the helical elements are not stable and periodically appear and disappear during the adsorption. Only the 310-helix Ser366-Val367-Leu368 remains stable. This helix preserves also in the adsorbed and freely relaxed S-protein. The contacts between the closest monomer and graphene are also similar to the contacts between the RBD of the S-protein and graphene; this applies also to Tyr449 amino acid residue.

One should keep in mind that the separated monomer of the spike protein trimer is more flexible as it has been found in previous MD simulations [53]. The enhanced flexibility has been observed in the hinge region Gly700- … -Asn710 and in the region Gln784- -Ser810 of the S2 subunit. In the trimeric spike protein, these two regions form β-sheets owing to their mutual stabilization, i.e., the β-sheet of the S2 subunit of one monomer is stabilized by the β-sheet of the hinge region of another monomer. In a separated monomer, these β-sheets are lost and transform into turns or coils [53]. In the present MD simulations, the same tendency has been observed.

4. Conclusions

The present atomistic MD simulations have studied the initial phase of the adsorption of the S-protein (non-glycosylated monomer of the spike glycoprotein trimer) onto the graphene surface to describe the kinetics and dynamics of this adsorption and to find out how this adsorption affects the structure of the S-protein.

The adsorption of the S-protein onto the graphene is fast during the first 10 ns, and after 20 ns of the simulation run, the number of contacts as well as the distance of the S-protein COM from the graphene are leveled off.

The structural properties of the S-protein adsorbed on the surface or relaxed in water are subject to the most dramatic changes during the first 20 ns of the MD simulations, after which these are equilibrated. The decrease of the perpendicular component of the radius of gyration is accompanied by the increase of the root mean square of the lateral components. The lateral deformation of the S-protein is caused by its adsorption onto the graphene, but the reduction of the perpendicular component is related to the reorientation of the S-protein rather than to its deformation in this direction. This can be seen in the time evolution of the asphericity and prolateness parameters, which indicate that the adsorption of the S-protein in water supports a prolate shape of the S-protein rather than an oblate shape. The asymmetry of both the adsorbed as well as the freely relaxed S-protein increased with time following similar trends, albeit more pronounced in the adsorbed case. The time evolutions of the principal components of the radius of gyration of the adsorbed S-protein and the freely relaxed S-protein are similar with the accentuated dependence and reduced fluctuations for the adsorbed S-protein. Reduced radius of gyration triggered by the adsorption indicates increased compactness of the adsorbed S-protein.

The time dependences of the RMSD of the S-protein and of its S1 and S2 subunits and RBD again follow the same trend for the adsorbed and freely relaxed S-protein. The S1 subunit is found to be much more flexible than the S2 subunit, which in turn exhibits slightly larger flexibility than the RBD. The adsorption of the S-protein stabilizes the structure of S1 subunit maintaining the rigidity of the RBD as well in the equilibrated phase. The structural stabilization of the adsorbed S-protein is also reflected on the number of clusters formed during the adsorption.

The specific interactions between the S-protein and graphene, with the orientation of the S1 subunit pointing to the graphene, are dominated by amide-π stacking of Asn and Gln residues. Orientations of the side chains of two Arg residues and one Trp, two Tyr, and five Phe residues, respectively, correspond to guanidine-π stacking and π-π stacking. Only the Tyr449 residue, which is directly involved in the specific interactions between RBD and ACE2 during the cell infection, gets into direct contact with graphene during the adsorption of S-protein.

There is a negligible destruction of the interfacial water structure in the close vicinity of graphene owing to the presence of the S-protein. The relaxation of the free S-protein in water and even more its adsorption on the graphene promotes formation of intramolecular hydrogen bonds. The number of hydrogen bonds between the S-protein and water drops more strikingly in the case of the adsorbed S-protein.

The secondary structures of the adsorbed and the freely relaxed S-protein experience only minor changes during the simulations. As a direct consequence of the adsorption, one α-helix of the RBD transforms into a turn. The adsorption stabilizes two α-helices in the RBD, which diminish during the free relaxation of the S-protein in water. One new α-helix created during the adsorption is not related directly to the adsorption process because this α-helix is created also during the free relaxation of the S-protein in water. The strands of the 5-stranded β-sheet adopt parallel alignment with the graphene and with the closest strand being stabilized by the presence of graphene. The secondary structure of the fragments containing the residues directly involved in the RBD-ACE2 interactions [12] is not affected by the adsorption.

This study shows that in water, the RBD of the S-protein possesses a rather rigid structure. This implies that its secondary structure might remain unchanged during the adsorption on some other surfaces as well as the RBD might remain quite resistant to the external conditions. In this study, the motifs containing residues, which are directly involved in the interactions with the ACE2 receptor, are neither subject to the changes of their secondary structure nor, with the exception of Tyr449, in the direct contact with the graphene.

These MD simulations suggest the affinity between the spike monomer of SARS-CoV-2 virus and the graphene. The deformation of the monomer shape and its enhanced compactness are observed with only subtle modification of its RBD. Although there are no significant changes in the secondary and tertiary structure found in the RBD of the S-protein, the feasibility of the changes in the quaternary structure of RBDs in the spike protein trimer triggered by its adsorption on the graphene should not be ruled out. Alteration of the quaternary structure of the spike protein trimer during its adsorption may involve transformation of the infective open state to the inactive closed state or to some other inactive conformations. After adsorption of the glycosylated RBD subunit, only one 310–helix preserves while the 5-stranded β-sheet is stabilized in the monomer closest to the graphene similarly to the S-protein. The remaining helices periodically appear and disappear during the adsorption.

The cigarette smoke is composed of aggregated aromatic particles, which interact with a protein in water through van der Waals interactions, π-π stacking and analogous interactions, and the hydrophobic interactions. The protein-graphene interactions in aqueous medium might reliably represent the latter two types of interactions, while the van der Waals attractions are supposed to be underestimated. Because the hydrophobic interactions usually dominate in these systems, the conclusions drawn for the interactions of the spike protein with the graphene in water might be valid for the interactions of the spike protein in water droplets with the aggregates present in the cigarette smoke. It would be of interest to scrutinize the behavior of SARS-CoV-2 virus in water droplets exposed to the cigarette smoke and to answer the question whether this virus can be spread through the cigarette smoke. As this study is based on some approximations and also does not incorporate whole virus where long-range interactions come into play, it should only shed light on the affinity of the spike protein monomer for the graphene and the associated conformational changes.

Author contributions

Z. Benková carried out the simulations and wrote the manuscript. The analysis and interpretation of data were performed by Z. Benková and M. N. D. S. Cordeiro.

Data availability

Data are available at https://www.openicpsr.org/openicpsr/project/134381/version/V1/view. The description of files is provided as the Supplementary Information.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grant VEGA 2/0122/20 and by Project UID/QUI/50006/2020 (LAQV@REQUIMTE) with funding from the FCT/MCTES through national funds.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtchem.2021.100572.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Zhu N., Zhang D., Wang W., Li X., Yang B., Song J., Zhao X., Huang B., Shi W., Lu R., Niu P., Zhan F., Ma X., Wang D., Xu W., Wu G., Gao G.F., Tan W. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:727–733. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wrapp D., Wang N., Corbett K.S., Goldsmith J.A., Hsieh C.L., Abiona O., Graham B.S., McLellan J.S. Cryo-EM structure of the 2019-nCoV spike in the prefusion conformation. Science. 2020;367:1260–1263. doi: 10.1126/science.aax0902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhu Z., Lian X., Su X., Wu W., Marraro G.A., Zeng Y. From SARS and MERS to COVID-19: a brief summary and comparison of severe acute respiratory infections caused by three highly pathogenic human coronaviruses. Respir. Res. 2020;21:224. doi: 10.1186/s12931-020-01479-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klompas M., Baker M.A., Rhee C. Airborne transmission of SARS-CoV-2 theoretical considerations and available evidence opinion. JAMA. 2020;324:441–442. doi: 10.7326/L20-0175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldman E. Exaggerated risk of transmission of COVID-19 by fomites. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020;20:892–893. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30561-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yoshimoto F.K. The proteins of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS CoV-2 or n-COV19), the cause of COVID-19. Protein J. 2020;39:198–216. doi: 10.1007/s10930-020-09901-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walls A.C., Park Y., Tortorici M.A., Wall A., McGuire A.T., Veesler D. Structure, function , and antigenicity of the SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein. Cell. 2020;181:281–292. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li F. Structure, function, and evolution of coronavirus spike proteins. Annu. Rev. Virol. 2016;3:237–264. doi: 10.1146/annurev-virology-110615-042301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wan Y., Shang J., Rachel G., Baric R.S., Li F. Receptor recognition by the novel coronavirus from Wuhan : an analysis based on decade-long structural studies of SARS coronavirus. J. Virol. 2020;94 doi: 10.1128/JVI.00127-20. e00127–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shang J., Ye G., Shi K., Wan Y., Luo C., Aihara H., Geng Q., Auerbach A., Li F. Structural basis of receptor recognition by SARS-CoV-2. Nature. 2020;581:221–224. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2179-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Oliveira O.V., Rocha G.B., Paluch A.S., Costa L.T. Repurposing approved drugs as inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 S-protein from molecular modeling and virtual screening. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2020;39:3924–3933. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2020.1772885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lan J., Ge J., Yu J., Shan S., Zhou H., Fan S., Zhang Q., Xuanling S., Wang Q., Zhang L., Wang X. Structure of the SARS-CoV-2 spike receptor-binding domain bound to the ACE2 receptor. Nature. 2020;581:215–220. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2180-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/news/fighting-coronavirus-european-supercomputers-join-pharmaceutical-companies-hunt-new-drugs

- 14.Kaseb A.O., Mohamed Y.I., Malek A.E., Raad I.I., Altameemi L., Li D., Kaseb O.A., Kaseb S.A., Selim A., Ma Q. The impact of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (Ace2) expression on the incidence and severity of covid-19 infection. Pathogens. 2021;10:379. doi: 10.3390/pathogens10030379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rao C.N.R., Sood A.K., Subrahmanyam K.S., Govindaraj A. Graphene: the new two-dimensional nanomaterial. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009;48:7752–7777. doi: 10.1002/anie.200901678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li Q., Lu J., Gupta P., Qiu M. Engineering optical absorption in graphene and other 2D materials: advances and applications. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2019;7:1900595. doi: 10.1002/adom.201900595. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zuo G., Zhou X., Huang Q., Fang H., Zhou R. Adsorption of villin headpiece onto graphene , carbon nanotube, and C60: effect of contacting surface curvatures on binding affinity. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2011;115:23323–23328. doi: 10.1021/JP208967T. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ou L., Luo Y., Wei G. Atomic-level study of adsorption, conformational change, and dimerization of an r-helical peptide at graphene surface. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2011;115:9813–9822. doi: 10.1021/jp201474m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen J., Wang X., Dai C., Chen S., Tu Y. Adsorption of GA module onto graphene and graphene oxide: a molecular dynamics simulation study. Phys. E Low-dimens. Syst. Nanostruct. 2014;62:59–63. doi: 10.1016/j.physe.2014.04.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhao D., Li L., He D., Zhou J. Molecular dynamics simulations of conformation changes of HIV-1 regulatory protein on graphene. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2016;377:324–334. doi: 10.1016/j.apsusc.2016.03.177. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.https://www.bonbouton.com/graphene-mask

- 22.https://www.graphene-info.com/israeli-researchers-develop-graphene-based-self-sterilizing-air-filter

- 23.Raghav P.K., Mohanty S. Are graphene and graphene-derived products capable of preventing COVID-19 infection? Med. Hypotheses. 2020;144:110031. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2020.110031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.https://zhanglab.ccmb.med.umich.edu/COVID-19

- 25.Rath S.L., Kumar K. Investigation of the effect of temperature on the structure of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein by molecular dynamics simulations. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2020;7:583523. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2020.583523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Darden T., York D., Pedersen L. Particle mesh Ewald: an N.log(N) method for Ewald sums in large systems. J. Chem. Phys. 1993;98:10089–10092. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Essmann U., Perera L., Berkowitz M.L., Darden T., Lee H., Pedersen L.G. A smooth particle mesh Ewald method. J. Chem. Phys. 1995;103:8577–8593. doi: 10.1063/1.464397. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pronk S., Páli S., Schulz R., Larsson P., Bjelkmar P., Apostolov R., Shirts M.R., Smith J.C., Kasson P.M., Van Der Spoel D., Hess B., Lindahl E. GROMACS 4.5: a high-throughput and highly parallel open source molecular simulation toolkit. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:845–854. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.MacKerell A.D., Feig M., Brooks C.L.I.I.I. Extending the treatment of backbone energetics in protein force fields: limitations of gas-phase quantum mechanics in reproducing protein conformational distributions in molecular dynamics simulations. J. Comput. Chem. 2004;25:1400–1415. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jorgensen W.L., Chandrasekhar J., Madura J.D., Impey Roger W., Klein M. Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water. J. Chem. Phys. 1983;79:926–936. doi: 10.1063/1.445869. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mark P., Nilsson L. Structure and dynamics of liquid water with different long-range interaction truncation and temperature control methods in molecular dynamics simulations. J. Comput. Chem. 2002;23:1211–1219. doi: 10.1002/jcc.10117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moore T.C., Yang A.H., Ogungbesan O., Hartkamp R., Iacovella C.R., Zhang Q., McCabe C. Influence of single-stranded DNA coatings on the interaction between graphene nanoflakes and lipid bilayers. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2019;123:7711–7721. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.9b04042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Malaspina D.C., Faraudo J. Computer simulations of the interaction between SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein and different surfaces. Biointerphases. 2020;15:51008. doi: 10.1116/6.0000502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hess B., P-LINCS A parallel linear constraint solver for molecular simulation. J. Chem. Theor. Comput. 2008;4:116–122. doi: 10.1021/ct700200b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bussi G., Donadio D., Parrinello M. Canonical sampling through velocity rescaling. J. Chem. Phys. 2007;126:14101. doi: 10.1063/1.2408420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tree D.R., Wang Y., Dorfman K.D. Modeling the relaxation time of DNA confined in a nanochannel. Biomicrofluidics. 2013;7:54118. doi: 10.1063/1.4826156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Páll S., Hess B. A flexible algorithm for calculating pair interactions on SIMD architectures. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2013;184:2641–2650. doi: 10.1016/j.cpc.2013.06.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hughes Z.E., Walsh T.R. What makes a good graphene-binding peptide? Adsorption of amino acids and peptides at aqueous graphene interfaces. J. Mater. Chem. B. 2015;3:3211–3221. doi: 10.1039/c5tb00004a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zifferer G. Shape distribution and correlation between size and shape of tetrahedral lattice chains in athermal and theta systems. J. Chem. Phys. 1998;109:3691. doi: 10.1063/1.476966. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zifferer G. Shape asymmetry of star-branched random walks and nonreversal random walks. Macromol. Theor. Simul. 1997;6:381–392. doi: 10.1002/mats.1997.040060206. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huang Y., Yang C., Xu X., Xu W., Liu S. Structural and functional properties of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein: potential antivirus drug development for COVID-19. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2020;41:1141–1149. doi: 10.1038/s41401-020-0485-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pandey R.B., Kuang Z., Farmer B.L., Kim S.S., Naik R.R. Stability of peptide (P1 and P2) binding to a graphene sheet via an all-atom to all-residue coarse-grained approach. Soft Matter. 2012;8:9101–9109. doi: 10.1039/c2sm25870f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Camden A.N., Barr S.A., Berry R.J. Simulations of peptide-graphene interactions in explicit water. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2013;117:10691–10697. doi: 10.1021/jp403505y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dragneva N., Floriano W.B., Stauffer D., Mawhinney R.C., Fanchini G., Rubel O. Favorable adsorption of capped amino acids on graphene substrate driven by desolvation effect. J. Chem. Phys. 2013;139:174711. doi: 10.1063/1.4828437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Welch C.M., Camden A.N., Barr S.A., Leuty G.M., Kedziora G.S., Berry R.J. Computation of the binding free energy of peptides to graphene in explicit water. J. Chem. Phys. 2015;143:45104. doi: 10.1063/1.4927344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dasetty S., Barrows J.K., Sarupria S. Adsorption of amino acids on graphene: assessment of current force fields. Soft Matter. 2019;15:2359. doi: 10.1039/c8sm02621a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Armijos-Jaramillo V., Yeager J., Muslin C., Perez-Castillo Y. SARS-CoV-2, an evolutionary perspective of interaction with human ACE2 reveals undiscovered amino acids necessary for complex stability. Evol. Appl. 2020;13:2168–2178. doi: 10.1111/eva.12980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Andersen K.G., Rambaut A., Lipkin W.I., Holmes E.C., Garry R.F. The proximal origin of SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Med. 2020;26:450–452. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0820-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.http://www.charmm-gui.org/docs/archive/covid19, 10.1088/1367-2630/5/1/395 [DOI]

- 50.Frishman D., Argos P. Knowledge-based protein secondary structure assignment. Proteins Struct. Funct. Genet. 1995;23:566–579. doi: 10.1002/prot.340230412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Guo J., Yao X., Ning L., Wang Q., Liu H. The adsorption mechanism and induced conformational changes of three typical proteins with different secondary structural features on graphene. RSC Adv. 2014;4:9953–9962. doi: 10.1039/c3ra45876h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cheng Y., Koh L.-D., Li D., Ji B., Zhang Y., Yeo J., Guan G., Han M.-Y., Zhang Y.-W. Peptide − graphene interactions enhance the mechanical properties of silk fibroin. Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2015;7:21787–21796. doi: 10.1021/acsami.5b05615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chen S.H., Young M.T., Gounley J., Stanley C., Bhowmik D. Distinct structural flexibility within SARS-CoV-2 spike protein reveals potential therapeutic targets. BioRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.04.17.047548. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are available at https://www.openicpsr.org/openicpsr/project/134381/version/V1/view. The description of files is provided as the Supplementary Information.